Abstract

The Put3p and Gal4p transcriptional activators are members of a distinct class of fungal regulators called the Cys6 Zn(II)2 binuclear cluster family. This family includes over 50 different Saccharomyces cerevisiae proteins that share a similar domain organization. Gal4p activates the genes of the galactose utilization pathway permitting the use of galactose as the sole source of carbon and energy. Put3p controls the expression of the proline utilization pathway that allows yeast cells to grow on proline as the sole nitrogen source. We report that Gal4p can activate the PUT structural genes in a strain lacking Put3p. We also show that the activation of PUT2 by Gal4p depends on the presence of the inducer galactose and the Put3p binding site and that activation increases with increased dosage of Gal4p. Put3p cannot activate the GAL genes in the absence of Gal4p. Our in vivo results confirm previously published in vitro data showing that Gal4p is more promiscuous than Put3p in its DNA binding ability. The results also suggest that under appropriate circumstances, Gal4p may be able to function in place of a related family member to activate expression.

In the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae, many pathways are controlled by the action of a large family of Cys6 Zn(II)2 binuclear proteins that share a similar domain organization. Each family member has a well-characterized DNA binding domain containing six cysteine residues that combine with two Zn2+ ions, forming the Cys6 zinc cluster. Adjacent to the DNA binding domain is a dimerization domain, followed by a central domain of unknown function and an acidic activation domain, frequently located in the carboxy terminus (33). Among the best-characterized members of this class are Gal4p, Put3p, Leu3p, Ppr1p, Hap1p, and Cha4p. These proteins regulate galactose metabolism, proline utilization, leucine biosynthesis, pyrimidine biosynthesis, oxygen-responsive genes, and the catabolism of hydroxylated amino acids, respectively (12, 16, 19, 23, 25, 45).

Of the 58 members of this family, Gal4p has been the most thoroughly studied. Regulated production of the galactose-utilizing enzymes results from an interplay between Gal4p, the repressor Gal80p, and a third protein, Gal3p, in the presence of the inducer galactose (5, 18, 24, 30). Gal4p binds as a dimer to a 17-bp upstream activation sequence (UASGAL) that is characterized by the sequence 5′-CGG-N11-CCG-3′ (15), and the specificity of that binding is found in the linker region between the DNA binding domain and the dimerization domain (11, 31).

The Put3p transcriptional regulator is required to activate genes that allow the growth of S. cerevisiae on proline as the sole nitrogen source (reviewed in reference 28). Put3p binds as a dimer to a 16-bp promoter sequence called UASPUT with the structure 5′-CGG-N10-CCG-3′ (13, 35). Although Put3p binds constitutively to its target sequences in vivo (2), the PUT genes are maximally expressed only in the presence of proline and in the absence of preferred sources of nitrogen (8, 9, 21, 42, 43). Unlike Gal4p, Put3p does not associate with a system-specific repressor and appears to regulate transcription by posttranslational modifications and conformational changes (17; S. G. des Etages et al., unpublished data).

Reece and Ptashne (31) showed that bacterially synthesized amino-terminal fragments of Gal4p could bind in vitro to sequences containing CGG triplets separated by 10 and 12 bp with an affinity about 1/10 that of the natural Gal4p binding site with the 11-bp spacer. These authors also reported that an amino-terminal fragment of Ppr1p showed some flexibility in its recognition site (5′-CGG-N6-CCG-3′) binding to CGG triplets with 7- and 8-bp spacers. However, amino-terminal Put3p fragments could only bind in vitro to sequences containing CGG separated by 10 bp, which is the spacing found in nature. Vashee et al. (40) compared the affinity of a purified Gal4p fragment to bind a variety of UASs in vitro to the ability of full-length Gal4p to activate reporter genes with those same UASs in vivo. They observed that many sites to which a fragment of Gal4p was able to bind with substantial affinity in vitro did not work in vivo to permit transcription by full-length Gal4p.

Given these findings, the aim of this study was to test whether Gal4p and Put3p can functionally substitute for one another in vivo. In the in vivo studies cited above, the activator proteins being compared were present in the cells and were competent to bind the test sequences in competition with one another. In this report, we provide evidence that under the appropriate conditions, Gal4p can activate the PUT genes, but only in a strain lacking Put3p. Put3p, however, could not under any of our test conditions activate the GAL genes. Our results confirm the in vitro data showing that Gal4p is more promiscuous than Put3p in its DNA binding ability. This suggests that under appropriate circumstances, Gal4p may be able to function in place of a related family member to activate expression.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmids.

The plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. Plasmid pABC4 (35) contains a PUT2-lacZ reporter gene with the wild-type PUT2 promoter extending to bp −890 upstream of the first codon of the open reading frame. Plasmid pABC18 (35) is identical to plasmid pABC4, except that it carries a 35-bp deletion of the Put3p binding site, UASPUT, from bp −164 to −128. Plasmid pMDB2 contains the GAL4 DNA binding domain (GBD, codons 1 to 147) fused to the activation domain of PUT3 (codons 890 to 979) and was constructed in two steps, as follows. Plasmid pSDB4 (13), carrying GBD-PUT3(890–979) under the control of the ADH1 promoter, was digested with ClaI and religated to remove the 450-bp CEN-ARS region, yielding plasmid pMDB1. Plasmid pMDB1 was digested with BglII and ligated to the 2.8-kb BglII LEU2 fragment from plasmid YEp13 (6) to form pMDB2, a yeast integrating plasmid carrying ADH1p-GBD-PUT3(890–979) and LEU2.

TABLE 1.

Plasmids used in this study

| Plasmid | Description | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| YEp24 | URA3, 2μm | 6 |

| YEp13 | LEU2, 2μm | 6 |

| YRp7 | TRP1 ARS1 | 37 |

| pSC3207 | pBluescript-URA3 | A. Barton |

| pHZ1 | URA3 CEN-ARS SUC2 | F. Winston |

| pMH76 | TRP1 ADH1p-GAL4 CEN-ARS | 32 |

| pBM746 | URA3 GAL1-lacZ CEN-ARS | M. Johnston |

| pBM2387 | 5′-GAL4-hisG-URA3-hisG-3′GAL4 in pBluescript | M. Johnston |

| pABC4 | URA3 PUT2-lacZ CEN-ARS | 35 |

| pABC18 | URA3 PUT2ΔUASPUT(−164/−129)-lacZ CEN-ARS | 35 |

| pMDB1 | TRP1 ADH1p-GBDa-PUT3(890–979) (integrating) | This work |

| pMDB2 | LEU2 ADH1p-GBD-PUT3(890–979) (integrating) | This work |

| pMDB6 | LEU2 ADH1p-GAL4 CEN-ARS | This work |

| pMDB8 | ura3::TRP1::ura3 GAL1-lacZ CEN-ARS | This work |

| pDB37 | URA3 PUT3 2μm | 26 |

| pDB107 | URA3 PUT3 CEN-ARS | 25 |

| pSDB4 | TRP1 ADH1p-GBD-PUT(890–979) CEN-ARS | 13 |

GBD, GAL4(1–147) under the control of the ADH1 promoter.

Plasmid pMDB6 is identical to plasmid pMH76 but has a URA3-selectable marker substituted for the TRP1 marker. A 1.5-kb BamHI-BglII fragment containing the URA3 gene from plasmid pSC3207 (A. Barton, University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey) was ligated to the 8.2-kb BglII fragment of pMH76.

Plasmid pMDB8 is identical to pBM746 except that the URA3 gene was disrupted by insertion of the TRP1 gene. Plasmid pBM746 was linearized by cutting with NcoI, and the 5′ overhanging end was filled in using DNA polymerase Klenow fragment (New England Biolabs). An 0.8-kb BglII TRP1 fragment was removed from plasmid pMH76, and the 5′ overhanging ends were filled in. The blunt-ended TRP1 fragment was ligated to pBM746 to create plasmid pMDB8. This plasmid contains GAL1-lacZ, TRP1, and CEN-ARS.

Yeast strains and growth media.

The S. cerevisiae strains used in this study are listed in Table 2. The gal4Δ strain MB1478 was constructed as follows. Strain DB27-7C was transformed with a SacI-KpnI fragment carrying GAL4 flanking sequences ligated to hisG-URA3-hisG from plasmid pBM2387. Ura+ transformants were selected; those that had secondarily acquired a Gal− phenotype were plated on minimal plates containing 5-fluoroorotic acid to select for those that had popped out the URA3 gene. Strain MB1478 was shown to carry a deletion of GAL4 by DNA hybridization analysis. It was crossed to strain DB27-5B to form diploid strain MB838, which was dissected to yield gal4Δ, put3Δ, and gal4Δ put3Δ mutant strains.

TABLE 2.

Strains used in this study

| Strain | Genotype | Source |

|---|---|---|

| DB27-3A | MATa put3::ADE2 GAL4 leu2::hisG ura3-52 TRP1::PUT2-lacZ | D. Barber |

| DB27-5B | MATa ade2 ura3-52 TRP1::PUT2-lacZ | D. Barber |

| DB27-7C | MATα put3::ADE2 ade2 trp1 ura3-52 | D. Barber |

| MB1478 | MATα put3::ADE2 gal4::hisG ade2 trp1 ura3-52 | This work |

| DA1000 | MATa put3::ADE2 GAL4 leu2::ADH1p-GBD-PUT3(890–979)-LEU2::hisG ura3-52 TRP1::PUT2-lacZ | This work |

| MB838-1B | MATα PUT3 gal4::hisG ade2 ura3-52 TRP1::PUT2-lacZ | This work |

| MB838-2B | MATα put3::ADE2 gal4::hisG ade2 ura3-52 TRP1::PUT2-lacZ | This work |

| MB838-2A | MATa put3::ADE2 GAL4 ade2 ura3-52 TRP1::PUT2-lacZ Suc− | This work |

| MB838-3C | MATa PUT3 GAL4 ade2 ura3-52 TRP1::PUT2-lacZ Suc− | This work |

| MB838-2C | MATα PUT3 gal4::hisG trp1 ade2 ura3-52 | This work |

| MB838-3A | MATα put3::ADE2 gal4::hisG trp1 ade2 ura3-52 | This work |

| MB838-1A | MATa put3::ADE2 GAL4 trp1 ade2 ura3-52 | This work |

Strain DA1000 was constructed by integrating plasmid pMDB2 carrying ADH1p-GBD-PUT3(890–979), linearized at its unique KpnI site, at the leu2::hisG locus of strain DB27-3A. The integration event was verified by Southern blotting, and production of the hybrid protein was detected by immunoblotting using anti-Put3p antibody.

Minimal media contained yeast nitrogen base without ammonium sulfate or amino acids (Difco) to which glucose (2% or 0.05%), galactose (2%), ethanol (3%) plus glycerol (3%), or raffinose (2%) was added as a carbon source and ammonium sulfate (0.2%), γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) (0.1%), or proline (0.1%) was added as a nitrogen source. Where necessary, adenine sulfate (20 mg/liter), uracil (20 mg/liter), tryptophan (20 mg/liter), or leucine (30 mg/liter) was added. Solid media contained agar (2%; Difco), except when proline was the sole nitrogen source, in which case agarose (SeaKem, 2%) was substituted.

Genetic analysis.

Mating, sporulation, and tetrad analysis were carried out using standard procedures (34). Yeast transformation was performed using the method of Gietz and Schiestl (14). Plasmid DNA was prepared from Escherichia coli by the method of Birnboim and Doly (4). E. coli transformation was performed by the CaCl2 method (10).

Growth of yeast strains, extract preparation, and β-galactosidase assays.

The cultivation of yeast strains, the preparation of extracts, and β-galactosidase assays have been described previously (25). The units of specific activity are nanomoles of o-nitrophenol formed per minute per milligram of protein. The numbers are the averages of two or three determinations; variation was usually ≤20% or as listed in the table footnotes. Protein concentrations of crude extracts were determined by the method of Bradford (7), using crystalline bovine serum albumin as the standard.

DNA hybridization.

Yeast genomic DNA was isolated (29), separated on 0.7% agarose gels, transferred to nylon membranes (Schleicher and Schuell), and blotted according to the method of Southern (36). For strains containing the GBD-PUT3(890–979) DNA, the membrane was probed with a 0.4-kb fragment containing codons 890 to 979 of PUT3. For strains with disruptions at the GAL4 locus, the probe was a 0.8-kb fragment corresponding to the 5′ untranslated region of GAL4. Both probes were radioactively labeled using the Multiprime labeling kit (Amersham) and [α-32P]dATP.

Immunoblotting.

Proteins from extracts of yeast were separated on sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis gels according to the method of Laemmli (22) and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes according to methods described by Clontech. Anti-Put3p antiserum (44) was diluted 1:2,000. The ECL chemiluminescence protocol (Amersham) was used to detect the proteins, following the instructions of the manufacturer.

RESULTS

Behavior of a Gal4p-Put3p hybrid protein.

S. cerevisiae strains lacking Put3p, the proline utilization pathway-specific activator, fail to grow on proline as the sole source of nitrogen because the PUT1 and PUT2 genes, which encode the enzymes of the pathway, are not expressed. In the absence of Put3p, strains growing on alternative nitrogen sources (e.g., ammonium sulfate or GABA) produce a level of expression of PUT1 and PUT2 that is approximately half the level observed in the wild-type strain, depending on growth conditions and strain background. This low-level expression may be the result of activation by other regulators.

Studies on a hybrid Gal4-Put3 protein containing the GBD (residues 1 to 147) fused to the carboxy-terminal activation domain of Put3p (residues 890 to 979) suggested that Gal4p might be able to activate the PUT genes. The miniactivator GBD-Put3(890–979) was shown to activate GAL gene expression to high levels and was neither proline responsive nor regulated by the Gal80p repressor (13). When the gene encoding this miniactivator (under the control of the ADH1 promoter) was integrated at the leu2::hisG locus of put3Δ strain DB27-3A, the new strain, DA1000, was able to grow on a solid medium containing proline as the sole nitrogen source (data not shown). Further, β-galactosidase levels from a PUT2-lacZ reporter gene increased more than 25-fold, from a specific activity of 67 in the parent strain DB27-3A to 1,760 in strain DA1000 when the strains were grown on a medium containing glucose (2%) and ammonium sulfate (0.2%).

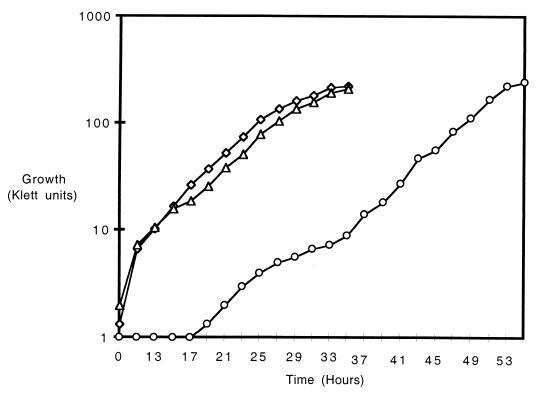

The growth of strain DA1000 carrying the miniactivator on a solid medium containing glucose and proline appeared slower than that of the wild-type strain after 4 days' incubation. However, its doubling time in liquid medium containing glucose and proline was 240 min, comparable to that of the parent strain carrying either high- or low-copy-number PUT3 plasmids (220 and 240 min, respectively). The apparent difference in growth rate on solid medium is due to the longer lag period of this strain than that of either of the two control strains (Fig. 1), which is likely to be a consequence of greater glucose repression of the ADH1 promoter in late exponential and stationary phase (1) than that affecting the PUT3 promoter.

FIG. 1.

Growth rates of strains carrying Put3p or GBD-Put3p(890–979). Three independent transformants were grown at 30°C in minimal medium containing glucose and proline. Growth was monitored with a Klett-Summerson colorimeter (blue filter). Similar results were obtained with three independent transformants; one curve for each is shown. Each strain also carried plasmid YEp13 to complement the leucine auxotrophy. ◊, strain DB27-3A (put3Δ) transformed with high-copy-number PUT3 plasmid pDB37; ▵, strain DB27-3A transformed with low-copy-number PUT3 plasmid pDB107; ○, strain DA1000 [GBD-PUT3(890–979)] transformed with plasmid YEp24.

Effect of carbon sources on the expression of PUT2.

If Gal4p were involved in regulating expression of the PUT genes, we would expect to see an effect of different carbon sources on the expression of the PUT2 gene. Strains were grown on minimal media containing glucose, glycerol plus ethanol, raffinose, or galactose as the sole carbon source, with ammonia as the sole nitrogen source. Expression was measured using a genomic PUT2-lacZ reporter gene. In a wild-type strain, the expression of PUT2 did not vary significantly as a function of carbon source (Table 3). When a put3Δ strain was grown with glucose, glycerol plus ethanol, or raffinose, PUT2-lacZ expression dropped by about 50%, in agreement with previous studies of strains in which the system-specific regulator was missing (13, 25). In the put3Δ strain grown on galactose, PUT2-lacZ expression increased fourfold over that observed on glucose and to a level somewhat higher than that of the wild-type strain grown under the same conditions (Table 3). This result suggested that when Put3p is not present, Gal4p can bind upstream of PUT2-lacZ and turn on gene expression.

TABLE 3.

Effect of changes in carbon source on PUT2 expression

| Relevant genotype | Sp act of β-galactosidase with growth ona:

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glu | Gly-Eth | Raff | Gal | |

| PUT3 GAL4 PUT2-lacZ | 73 | 75 | 55 | 78 |

| put3Δ GAL4 PUT2-lacZ | 27 | 45 | 32 | 100 |

Strains MB838-3C and MB838-2A were grown in minimal media containing glucose (Glu, 2%), glycerol plus ethanol (Gly-Eth, 3% each), raffinose (Raff, 2%), or galactose (Gal, 2%) as the sole carbon source and ammonium sulfate (0.2%), adenine sulfate (20 mg/liter), and uracil (20 mg/liter). For growth on raffinose, these strains were transformed with plasmid pHZ1 carrying the SUC2 gene, and uracil was omitted from the medium. Values are the averages of three determinations; variation was ≤19%.

Analysis of PUT2 expression in galactose induction.

To determine if Gal4p was responsible for the increase in expression described above, strains carrying the four combinations of deletion alleles of PUT3 and GAL4 were examined. Cultures were grown in media containing a low glucose concentration (0.05%) with or without galactose (2%). Under these conditions, glucose repression is minimized, and an increase in expression is due to galactose induction. In the absence of both Put3p and Gal4p, there is a background level of expression of β-galactosidase that may be due to the contribution of other yet-unrecognized factors. The background level (22 U in the absence of galactose and 35 U in the presence of galactose) was subtracted in order to compare the specific contribution of each activator. In the absence of galactose, Put3p is responsible for all of the expression observed, in the presence or absence of Gal4p (Table 4, −Gal). In the presence of galactose, both Gal4p and Put3p contribute to the expression of PUT2 (Table 4, +Gal).

TABLE 4.

Gal4p can activate PUT2 gene expression in the absence of Put3p

| Strainb | Relevant genotype | Plasmid | β-galactosidase net sp acta

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| −Gal | +Gal | |||

| MB838-3C | PUT3 GAL4 PUT2-lacZ | None | 41 | 40 |

| MB838-1B | PUT3 gal4Δ PUT2-lacZ | None | 40 | 19 |

| MB838-2A | put3Δ GAL4 PUT2-lacZ | None | 0 | 19 |

| MB838-2A | put3Δ GAL4 PUT2-lacZ | pMDB6c | 0 | 100 |

| MB838-2B | put3Δ gal4Δ PUT2-lacZ | None | 0 | 0 |

The put3Δ galΔ strain produced a background β-galactosidase specific activity of 22 U in the absence of galactose and 35 U in the presence of galactose. This activity was subtracted from the total activity of each strain under each condition. Values are the averages of three determinations; variation was ≤17%.

Strains MB838-3C, MB838-1B, MB838-2A, and MB838-2B were grown on minimal media containing glucose (0.05%), with or without galactose (2%), and ammonium sulfate (0.2%), adenine sulfate (20 mg/liter), and uracil (20 mg/liter). Uracil was omitted when the strain carried the plasmid.

Plasmid pMDB6 carried a copy of the GAL4 gene under the control of the constitutive ADH1 promoter.

The conclusion that Gal4p is responsible for activation of PUT2 in the absence of Put3p was further supported by measurements made in a strain in which Gal4p was overexpressed. When a plasmid carrying the GAL4 gene under the control of the ADH1 promoter was introduced into strains lacking Put3p, expression increased even further (Table 4). The specificity of this interaction was tested by examining expression of a reporter gene in which the Put3p binding site (UASPUT) was deleted. Specific activities of β-galactosidase in a put3Δ strain (MB838-1A) carrying the wild-type PUT2-lacZ plasmid pABC4 with either genomic or overexpressed levels of Gal4p (from plasmid pMH76) were 26 and 43, respectively, when the cells were grown on a medium containing galactose and ammonium sulfate. Removal of the Put3p binding site from the reporter plasmid (pABC18) caused the expression of PUT2-lacZ to drop 10- to 20-fold, decreasing specific activities to 2 in both cases (variation was <10%). The effect of Gal4p (expressed at genomic levels or overexpressed from the ADH1 promoter) was visible in the growth of a put3Δ gal4Δ strain on plates where proline was the sole source of nitrogen (data not shown).

Put3p cannot replace Gal4p in activation of the GAL genes.

To determine if Put3p was able to bind UASGAL elements in vivo to activate the GAL genes, GAL1-lacZ expression was measured in strains carrying a deletion of GAL4. Strains MB838-2C (PUT3 gal4Δ) and MB838-3A (put3Δ gal4Δ) were transformed with the low-copy-number GAL1-lacZ plasmid pBM746 or pMDB8 and grown on media containing GABA or GABA plus Pro as nitrogen sources with glucose as the carbon source. The β-galactosidase specific activity was ≤1 under either condition measured and was the same whether PUT3 was present in the genome (single copy) or on a high-copy-number plasmid. The control, the congenic strain MB838-1A (put3Δ GAL4) carrying the same GAL1-lacZ plasmid, had a β-galactosidase specific activity of 407 on a medium containing galactose and GABA.

DISCUSSION

The Cys6 Zn(II)2 binuclear cluster family of transcription factors controls a variety of pathways in S. cerevisiae. Pathway-specific regulation by these factors is maintained using a combination of differential affinity for DNA binding to particular UASs, interaction with small-molecule inducers, binding to repressor proteins, and posttranslational modifications. However, some of these fungal activators may be sufficiently similar to substitute for one another in vivo to a limited extent and under the appropriate conditions. In this report, we have demonstrated the ability of Gal4p to regulate the proline utilization pathway but only when Put3p, the system-specific regulator, has been removed.

Activation of PUT genes by Gal4p requires induction by galactose and the Put3p binding site, can be accomplished with the low levels of Gal4p made from a single GAL4 gene in the genome, and is not observed in the presence of Put3p. However, there is no reciprocity: Put3p did not activate the GAL genes under any of our test conditions, including overproduction of Put3p in the presence of the inducer proline. These proteins are closely related and share an amino-terminal DNA binding motif, a homologous central domain, and a carboxy-terminal acidic activation domain. Both recognize a binding site with two CGG triplets, separated by 11 bp (Gal4p) or 10 bp (Put3p).

Bacterially synthesized fragments of the DNA binding domains of Gal4p and Put3p fragments have been purified and analyzed by X-ray crystallography (27, 38) and nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy (3, 20, 41). Both proteins rely on conserved regions in the Zn2 Cys6 domain to contact the two inverted CGG triplets and a region downstream of the zinc-binding domain containing a linker and part of the dimerization domain to specify the number of base pairs in the spacer region. In vitro DNA binding experiments that measured the affinities of Gal4p, Put3p, and another family member, Ppr1p, for a variety of sites demonstrated that the Gal4p linker-dimerization element region permitted binding with a 10-fold-reduced affinity to sites with spacers that were 10 or 12 bp, rather than the naturally occurring 11 bp, but that Put3p was unable to bind any site having a spacing different from 10 bp (31).

Vashee et al. (40) compared the DNA binding affinity of Gal4p for a variety of GAL4 sites, both naturally occurring and mutated, in vivo and in vitro. They found that many sites to which Gal4p could bind with moderate or high affinity in vitro did not support Gal4p-activated transcription in vivo. In agreement with the results reported by Reece and Ptashne (31), Vashee et al. (40) found a 25-fold decrease in in vitro binding by a Gal4p fragment to a site with a 10-bp spacer, as compared to the 11-bp natural spacer. However, there was no detectable activation of transcription of a reporter gene carrying this 10-bp site by full-length Gal4p in vivo. These authors concluded that in many cases there was not a quantitative correlation between in vitro DNA binding and in vivo activation of transcription. The discrepancy might reflect differences in behavior between a recombinant fragment of Gal4p and the entire full-length protein, the use of unnatural sites, or the existence of another protein that can bind UASGAL in vivo.

Vashee et al. (40) also reported that Gal4p did not activate transcription in vivo when the 11-bp GAL UAS was replaced with a 10-bp site resembling the PUT UAS, although they did observe in vitro binding of DNA containing this 10-bp site by a Gal4p fragment. We were able to see Gal4p activation of the PUT genes in vivo, but only when there was no Put3p present. In the presence of Put3p, we saw no effect of activation by Gal4p (Table 4). In the experiments described by Vashee et al., it is likely that Put3p was present and binding its own site, protecting it from binding by Gal4p.

An unusually high level of background activity in the expression of certain reporter constructs led Vashee et al. (40) to suggest the existence of one or more other activators that could recognize some of their consensus GAL4 binding sites under noninducing conditions. We also have observed a higher level of background PUT2 expression in our put3Δ strains than in some other put3 mutants known to carry point mutations (13). This observation led to the suggestion that other regulators could activate the PUT genes only in the absence of Put3p; the mutant Put3 proteins that could still bind DNA were perhaps blocking the UAS from activation by other regulators, leading to a lower background level of expression.

In addition to its ability to activate the PUT genes, Gal4p can also cooperate with Put3p in activating gene expression. In a more recent study, Vashee et al. (39) used synthetic reporter constructs that contained binding sites for both Gal4p and Put3p spaced about 26 bp apart to show that these activators interacted synergistically at this artificial promoter. The authors argue that Gal4p and Put3p can bind to nearby sites in a nontraditional cooperative fashion that does not rely on their interacting with one another but perhaps by contacting different proteins of the transcriptional apparatus.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank F. Winston, M. Johnston, I. Sadowski, and A. Barton for gifts of plasmids and D. Barber for construction of several put3Δ strains. We are grateful to S. Garrett, M. Hampsey, and S. G. des Etages for stimulating discussions and useful suggestions.

This work was supported by the University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey Graduate School of Biomedical Sciences and by Public Health Service grant 5 R01 GM 40751 from the National Institutes of Health.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ammerer G. Expression of genes in yeast using the ADC1 promoter. Methods Enzymol. 1983;101:192–201. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(83)01014-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Axelrod J D, Majors J, Brandriss M C. Proline-independent binding of PUT3 transcriptional activator protein detected by footprinting in vivo. Mol Cell Biol. 1991;11:564–567. doi: 10.1128/mcb.11.1.564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baleja J D, Marmorstein R, Harrison S C, Wagner G. Solution structure of the DNA-binding domain of Cd2-GAL4 from S. cerevisiae. Nature. 1992;356:450–453. doi: 10.1038/356450a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Birnboim H C, Doly J. A rapid alkaline extraction procedure for screening recombinant plasmid DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 1979;7:1513–1523. doi: 10.1093/nar/7.6.1513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blank T E, Woods M P, Lebo C M, Xin P, Hopper J E. Novel Gal3 proteins showing altered Gal80p binding cause constitutive transcription of Gal4p-activated genes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:2566–2575. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.5.2566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Botstein D, Falco S C, Stewart S E, Brennan M, Scherer S, Stinchcomb D T, Struhl K, Davis R W. Sterile host yeast (SHY): a eukaryotic system of biological containment for recombinant DNA experiments. Gene. 1979;8:17–24. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(79)90004-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bradford M M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brandriss M C. Proline utilization in Saccharomyces cerevisiae: analysis of the cloned PUT2 gene. Mol Cell Biol. 1983;3:1846–1856. doi: 10.1128/mcb.3.10.1846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brandriss M C, Magasanik B. Genetics and physiology of proline utilization in Saccharomyces cerevisiae: enzyme induction by proline. J Bacteriol. 1979;140:498–503. doi: 10.1128/jb.140.2.498-503.1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cohen S N, Chang A C Y, Hsu L. Nonchromosomal antibiotic resistance in bacteria: genetic transformation of Escherichia coli by R-factor DNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1972;69:2110–2114. doi: 10.1073/pnas.69.8.2110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Corton J C, Johnston S A. Altering DNA-binding specificity of GAL4 requires sequences adjacent to the zinc finger. Nature. 1989;340:724–727. doi: 10.1038/340724a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Creusot F, Verdiere J, Gaisne M, Slonimski P P. CYP1 (HAP1) regulator of oxygen dependent gene expression in yeast. I. Overall organization of the protein sequence displays several novel structural domains. J Mol Biol. 1988;204:263–276. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(88)90574-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.des Etages S G, Falvey D A, Reece R J, Brandriss M C. Functional analysis of the PUT3 transcriptional activator of the proline utilization pathway in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 1996;142:1069–1082. doi: 10.1093/genetics/142.4.1069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gietz R, Schiestl R. Transforming yeast with DNA. Methods Mol Cell Biol. 1995;5:255–269. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Giniger E, Varnum S M, Ptashne M. Specific DNA binding of GAL4, a positive regulatory protein of yeast. Cell. 1985;40:767–774. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(85)90336-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Holmberg S, Schjerling P. Cha4p of Saccharomyces cerevisiae activates transcription via serine/threonine response elements. Genetics. 1996;133:467–478. doi: 10.1093/genetics/144.2.467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huang H L, Brandriss M C. The regulator of the yeast proline utilization pathway is differentially phosphorylated in response to the quality of the nitrogen source. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:892–899. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.3.892-899.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Johnston M, Carlson M. Regulation of carbon and phosphate utilization. In: Jones E W, Pringle J R, Broach J R, editors. The molecular and cellular biology of the yeast Saccharomyces. Vol. 2. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1992. pp. 192–281. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kammerer B, Guyonvarch A, Hubert J C. Yeast regulatory gene PPR1. I. Nucleotide sequence, restriction map and codon usage. J Mol Biol. 1984;180:239–250. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(84)80002-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kraulis P J, Raine A R C, Gadhavi P L, Laue E D. Structure of the DNA binding domain of zinc GAL4. Nature. 1992;356:448–450. doi: 10.1038/356448a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Krzywicki K A, Brandriss M C. Primary structure of the nuclear PUT2 gene involved in the mitochondrial pathway for proline utilization in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol. 1984;4:2837–2842. doi: 10.1128/mcb.4.12.2837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Laemmli U K. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Laughon A, Gesteland R F. Primary structure of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae GAL4 gene. Mol Cell Biol. 1984;4:260–267. doi: 10.1128/mcb.4.2.260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lohr D, Venko P, Zlatanova J. Transcriptional regulation in the yeast GAL gene family: a complex genetic network. FASEB J. 1995;9:777–787. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.9.9.7601342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marczak J E, Brandriss M C. Analysis of constitutive and noninducible mutations of the PUT3 transcriptional activator. Mol Cell Biol. 1991;11:2609–2619. doi: 10.1128/mcb.11.5.2609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Marczak J E, Brandriss M C. Isolation of constitutive mutations affecting the proline utilization pathway in Saccharomyces cerevisiae and molecular analysis of the PUT3 transcriptional activator. Mol Cell Biol. 1989;9:4696–4705. doi: 10.1128/mcb.9.11.4696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Marmorstein R, Carey M, Ptashne M, Harrison S C. DNA recognition by GAL4: structure of a protein-DNA complex. Nature. 1992;356:408–414. doi: 10.1038/356408a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Marzluf G A. Genetic regulation of nitrogen metabolism in the fungi. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1997;61:17–32. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.61.1.17-32.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Philippsen P, Stotz A, Scherf C. DNA of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Methods Enzymol. 1991;194:169–182. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(91)94014-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Platt A, Reece R J. The yeast galactose genetic switch is mediated by the formation of a Gal4p-Gal80p-Gal3p complex. EMBO J. 1998;17:4086–4091. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.14.4086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Reece R J, Ptashne M. Determinants of binding site-specificity among yeast C6 zinc cluster proteins. Science. 1993;261:909–911. doi: 10.1126/science.8346441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sadowski I, Bell B, Broad P, Hollis M. GAL4 fusion vectors for expression in yeast or mammalian cells. Gene. 1992;118:137–141. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(92)90261-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schjerling P, Holmberg S. Comparative amino acid sequence analysis of the C6 zinc cluster family of transcriptional regulators. Nucleic Acids Res. 1996;24:4599–4607. doi: 10.1093/nar/24.23.4599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sherman F, Fink G R, Lawrence C W. Methods in yeast genetics. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Siddiqui A H, Brandriss M C. A regulatory region responsible for proline-specific induction of the yeast PUT2 gene is adjacent to its TATA box. Mol Cell Biol. 1988;8:4634–4641. doi: 10.1128/mcb.8.11.4634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Southern E M. Detection of specific sequences among DNA fragments separated by gel electrophoresis. J Mol Biol. 1975;98:503–517. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(75)80083-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Struhl K, Stinchcomb D T, Scherer S, Davis R W. High-frequency transformation of yeast: autonomous replication of hybrid DNA molecules. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1979;76:1035–1039. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.3.1035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Swaminathan K, Flynn P, Reece R J, Marmorstein R. Crystal structure of a PUT3-DNA complex reveals a novel mechanism for DNA recognition by a protein containing a Zn2Cys6 binuclear cluster. Nat Struct Biol. 1997;4:751–759. doi: 10.1038/nsb0997-751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vashee S, Willie J, Kodadek T. Synergistic activation of transcription by physiologically unrelated transcription factors through cooperative DNA-binding. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1998;247:530–535. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.8820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vashee S, Xu H, Johnston S A, Kodadek T. How do “Zn2Cys6” proteins distinguish between similar upstream activation sites? J Biol Chem. 1993;268:24699–24706. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Walters K J, Dayie K T, Reece R J, Ptashne M, Wagner G. Structure and mobility of the PUT3 dimer. Nat Struct Biol. 1997;4:744–750. doi: 10.1038/nsb0997-744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang S-S, Brandriss M C. Proline utilization in Saccharomyces cerevisiae: analysis of the cloned PUT1 gene. Mol Cell Biol. 1986;6:2638–2645. doi: 10.1128/mcb.6.7.2638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang S-S, Brandriss M C. Proline utilization in Saccharomyces cerevisiae: sequence, regulation, and mitochondrial localization of the PUT1 gene product. Mol Cell Biol. 1987;7:4431–4440. doi: 10.1128/mcb.7.12.4431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Xu S, Falvey D A, Brandriss M C. Roles of URE2 and GLN3 in the proline utilization pathway in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:2321–2330. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.4.2321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhou K, Brisco P R G, Hinkkanen A E, Kohlhaw G B. Structure of yeast regulatory gene LEU3 and evidence that LEU3 itself is under general amino acid control. Gene. 1987;15:5261–5273. doi: 10.1093/nar/15.13.5261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]