Abstract

The levels of reduced and oxidized nicotinamide adenine dinucleotides were determined in Xanthobacter flavus during a transition from heterotrophic to autotrophic growth. Excess reducing equivalents are rapidly dissipated following induction of the Calvin cycle, indicating that the Calvin cycle serves as a sink for excess reducing equivalents. The physiological data support the conclusion previously derived from molecular studies in that expression of the Calvin cycle genes is controlled by the intracellular concentration of NADPH.

Xanthobacter flavus assimilates CO2 via the Calvin cycle during autotrophic growth. The energy required to operate the Calvin cycle is provided by the oxidation of methanol, formate, thiosulfate, or hydrogen. In addition, heterotrophic growth is supported by a wide range of organic substrates, e.g., gluconate or succinate (15). In this case, CO2 fixation is not necessary and the Calvin cycle is not induced. To date, three unlinked transcriptional units encoding Calvin cycle enzymes have been identified in X. flavus: the cbb (14, 21) and gap-pgk (13, 17) operons and the tpi gene (16). The key enzymes of the Calvin cycle, ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase (RuBisCO) and phosphoribulokinase, are encoded by the cbb operon.

The LysR-type transcriptional regulator CbbR has been identified in several chemo- and photoautotrophic bacteria (10). This protein controls expression of the cbb operon and, in X. flavus, also the gap-pgk operon (17, 22). We previously showed that purified CbbR protects nucleotides −75 to −29 relative to the transcriptional start of the cbb operon in a DNase I footprinting assay. In addition, it was shown that purified CbbR responds to NADPH but not NADH in vitro: DNA binding of CbbR increases threefold and CbbR-induced DNA bending is relaxed by 9° in the presence of NADPH. The apparent Kd[NADPH] was determined to be 75 μM; saturation occurs at approximately 200 μM (23).

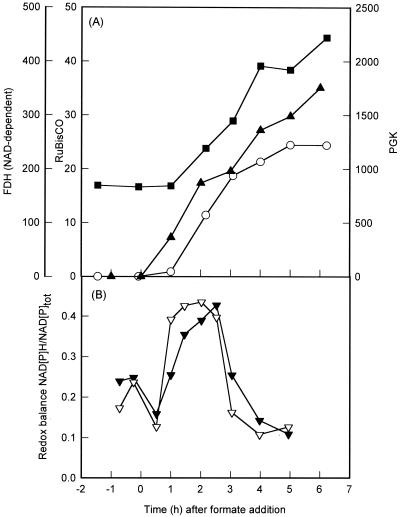

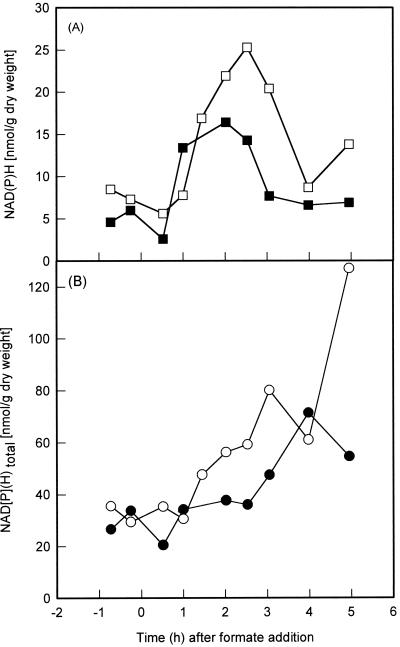

The results from these in vitro experiments strongly suggest that the in vivo expression of the cbb and gap-pgk operons is mediated by CbbR in response to the intracellular concentration of NADPH. To examine this in greater detail, the levels of reduced and oxidized nicotinamide adenine dinucleotides were determined during a transition from heterotrophic to autotrophic growth. X. flavus was grown on a mixture of gluconate (5 mM) and formate (20 mM) with pH control by automatic titration with formic acid (25% [vol/vol]) as described previously (15). RuBisCO (5), phosphoglycerate kinase (13), and NAD-dependent formate dehydrogenase (4) enzyme activities were subsequently determined in cell extracts as described previously. Protein was determined by the Bradford method, using bovine serum albumin as a standard (3). Significant formate dehydrogenase activity was already present 1 h following addition of formate to heterotrophically growing X. flavus. In contrast, induction of the cbb and gap-pgk operons, as indicated by the appearance of RuBisCO and increase of phosphoglycerate kinase activity, became apparent 2 h after formate addition (Fig. 1A). During the transition from autotrophic to heterotrophic growth, samples withdrawn from the fermenter were immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen and subsequently freeze-dried. Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotides were extracted from freeze-dried samples (12) and then quantified using a sensitive spectrophotometric cycling assay (2). Following addition of formate to the medium, the concentrations of NAD(H) and NADP(H) increased four- and twofold, respectively, over a period of 5 h (Fig. 2). Prior to addition of formate to the medium, 15 to 25% of the nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide pools were in the reduced form. This percentage increased rapidly following addition of formate to culture and paralled the increasing activity of formate dehydrogenase (Fig. 1). The rapid increase in redox balance, defined as the ratio of reduced to total nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide, is therefore most likely due to oxidation of formate and the concomitant production of NADH. Similar observations were made when the chemoautotrophic bacterium Pseudomonas oxalaticus was transferred from oxalate to formate medium (9). The redox balance reached a maximum 2 h after addition of formate to the medium and subsequently decreased rapidly, even though the activity of formate dehydrogenase and the total concentration of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide continued to increase (Fig. 1 and 2). The sharp decrease in redox balance coincided with the appearance of RuBisCO activity and the increase in phosphoglycerate kinase activity, which is indicative of operation of the Calvin cycle. This pathway consumes 6 mol of NADH and 9 of ATP for every mole of triosephosphate produced. It is therefore likely that the high demand of autotrophic CO2 fixation for NADH accounts for the observed decrease in redox balance. The most obvious function of the Calvin cycle is to supply the cell with a source of carbon during autotrophic growth. A second, equally important function is to act as an electron sink in order to dissipate excess reducing power (11, 20). For example, purple nonsulfur bacteria fail to grow photoheterotrophically in the absence of a functional Calvin cycle unless an alternative electron acceptor such as dimethyl sulfoxide is present (6, 19, 24). Interestingly, secondary mutants of RuBisCO-deficient Rhodobacter sphaeroides strains which had regained the ability to grow photoheterotrophically were isolated (24). These mutants induced nitrogenase to reduce protons to H2, resulting in dissipation of excess reducing equivalents (8). Induction of the Calvin cycle in X. flavus resulted in a rapid decrease of the redox balance to below levels seen before the addition of formate. This suggests that CO2 fixation via the Calvin cycle is very effective in removing excess reducing power.

FIG. 1.

(A) Activities of RuBisCO (○), phosphoglycerate kinase (PGK; ■), and formate dehydrogenase [FDH (NAD-dependent); ▴] of X. flavus growing on 5 mM gluconate. The results following addition of 20 mM formate and automatic titration with formic acid (25% [vol/vol]) at time zero) are shown. Enzyme activities are expressed in nanomoles per minute per milligram of protein. (B) NAD(H) (▾) and NADP(H) (▿) redox balance ([NAD(P)H]/[NAD(P)] + [NAD(P)H]) of X. flavus growing on 5 mM gluconate. The results before and after the addition of 20 mM formate and automatic titration with formic acid (25% [vol/vol]) at time zero are shown.

FIG. 2.

Concentrations of NADH (A, □) and NADPH (A, ■) and total concentrations of NADH plus NAD+ (B, ○) and NADPH plus NADP+ (B, ●) following the addition of 20 mM formate to a culture growing on 5 mM gluconate at time zero.

The Calvin cycle was induced as the concentration of NADPH approached its maximum (16.4 nmol/g [dry weight]), 1 h following addition of formate to the culture (Fig. 1A and 2A). This corresponds to an intracellular NADPH concentration of 189 to 216 μM, assuming a cellular volume of 3.5 to 4 μl/mg of protein (1, 7, 18). NADPH at this concentration saturates CbbR in vitro, resulting in maximum DNA binding affinity and relaxed DNA bending. The NADPH concentration remained at this level for another 2 h, during which the activity of RuBisCO increased 21-fold. Both the redox balance and the concentration of NADPH subsequently decreased rapidly (Fig. 1B and 2A). However, although the redox balance was reduced to below levels observed before the addition of formate, the NADPH concentration remained twofold higher, at a concentration of 81 to 93 μM. This concentration is slightly above the previously reported Kd[NADPH] of 75 μM. The RuBisCO activity increased only 1.3-fold during this period. The expression levels of the cbb operon therefore correspond to the degree of NADPH saturation of CbbR in vitro. This observation supports, but does not prove, our previous conclusion based on molecular studies that the intracellular NADPH concentration determines the activity of CbbR and hence expression of the cbb operon (23). Future research will aim to analyze the interaction between NADPH and CbbR in greater detail.

Acknowledgments

We thank Gert-Jan Euverink and Jan C. Gottschal for valuable suggestions and discussions.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abee T, Palmen R, Hellingwerf K J, Konings W N. Osmoregulation in Rhodobacter sphaeroides. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:149–154. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.1.149-154.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bernofsky C, Swan M. An improved cycling assay for nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide. Anal Biochem. 1973;53:452–458. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(73)90094-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bradford M M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976;73:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dijkhuizen L, Knight M, Harder W. Metabolic regulation in Pseudomonas oxalaticus OX1. Autotrophic and heterotrophic growth on mixed substrates. Arch Microbiol. 1978;116:77–83. doi: 10.1007/BF00408736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gibson J L, Tabita F R. Different molecular forms of d-ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase from Rhodopseudomonas sphaeroides. J Biol Chem. 1977;252:943–949. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hallenbeck P L, Lerchen R, Hessler P, Kaplan S. Roles of CfxA, CfxB, and external electron acceptors in regulation of ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase expression in Rhodobacter sphaeroides. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:1736–1748. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.4.1736-1748.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hoischen C, Krämer R. Evidence for an efflux carrier system involved in the secretion of glutamate by Corynebacterium glutamicum. Arch Microbiol. 1989;151:342–347. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Joshi H, Tabita F R. A global two component signal transduction system that integrates the control of photosynthesis, carbon dioxide assimilation, and nitrogen fixation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:14515–14520. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.25.14515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Knight M, Dijkhuizen L, Harder W. Metabolic regulation in Pseudomonas oxalaticus OX1. Enzyme and coenzyme concentration changes during substrate transition experiments. Arch Microbiol. 1978;116:85–90. doi: 10.1007/BF00408737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kusian B, Bowien B. Organization and regulation of cbb CO2 assimilation genes in autotrophic bacteria. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 1997;21:135–155. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.1997.tb00348.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lascelles J. The formation of ribulose 1:5-diphosphate carboxylase by growing cultures of Athiorhodaceae. J Gen Microbiol. 1960;23:499–510. doi: 10.1099/00221287-23-3-499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Matin A, Gottschal J C. Influence of dilution rate on NAD(P) and NAD(P)H concentrations and ratios in a Pseudomonas sp. grown in a continuous culture. J Gen Microbiol. 1976;94:333–341. doi: 10.1099/00221287-94-2-333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Meijer W G. The Calvin cycle enzyme phosphoglycerate kinase of Xanthobacter flavus required for autotrophic CO2 fixation is not encoded by the cbb operon. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:6120–6126. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.19.6120-6126.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Meijer W G, Arnberg A C, Enequist H G, Terpstra P, Lidstrom M E, Dijkhuizen L. Identification and organization of carbon dioxide fixation genes in Xanthobacter flavus H4-14. Mol Gen Genet. 1991;225:320–330. doi: 10.1007/BF00269865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Meijer W G, Croes L M, Jenni B, Lehmicke L G, Lidstrom M E, Dijkhuizen L. Characterization of Xanthobacter strains H4-14 and 25a and enzyme profiles after growth under autotrophic and heterotrophic growth conditions. Arch Microbiol. 1990;153:360–367. doi: 10.1007/BF00249006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Meijer W G, de Boer P, van Keulen G. Xanthobacter flavus employs a single triosephosphate isomerase for heterotrophic and autotrophic metabolism. Microbiology. 1997;143:1925–1931. doi: 10.1099/00221287-143-6-1925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Meijer W G, van den Bergh E R E, Smith L M. Induction of the gap-pgk operon encoding glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase and 3-phosphoglycerate kinase of Xanthobacter flavus requires the LysR-type transcriptional activator CbbR. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:881–887. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.3.881-887.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Poolman B, Smid E J, Veldkamp H, Konings W N. Bioenergetic consequences of lactose starvation for continuously cultured Streptococcus cremoris. J Bacteriol. 1987;169:1460–1468. doi: 10.1128/jb.169.4.1460-1468.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Richardson D J, King G F, Kelly D J, McEwan A G, Ferguson S J, Jackson J B. The role of auxiliary oxidants in maintaining the redox balance during phototrophic growth of Rhodobacter capsulatus on propionate or butyrate. Arch Microbiol. 1988;150:131–137. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shively J M, van Keulen G, Meijer W G. Something from almost nothing: carbon dioxide fixation in chemoautotrophs. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1998;52:191–230. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.52.1.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.van den Bergh E R E, Baker S C, Raggers R J, Terpstra P, Woudstra E C, Dijkhuizen L, Meijer W G. Primary structure and phylogeny of the Calvin cycle enzymes transketolase and fructosebisphosphate aldolase of Xanthobacter flavus. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:888–893. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.3.888-893.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.van den Bergh E R E, Dijkhuizen L, Meijer W G. CbbR, a LysR-type transcriptional activator, is required for expression of the autotrophic CO2 fixation enzymes of Xanthobacter flavus. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:6097–6104. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.19.6097-6104.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.van Keulen G, Girbal L, van den Bergh E R E, Dijkhuizen L, Meijer W G. The LysR-type transcriptional regulator CbbR controlling autotrophic CO2 fixation by Xanthobacter flavus is an NADPH sensor. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:1411–1417. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.6.1411-1417.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang X, Falcone D L, Tabita F R. Reductive pentose phosphate-independent CO2 fixation in Rhodobacter sphaeroides and evidence that ribulose bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase activity serves to maintain the redox balance of the cell. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:3372–3379. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.11.3372-3379.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]