Introduction

Positive psychological health is crucial to optimal clinical outcomes across the cancer care continuum, from prevention and risk reduction to palliative care and survivorship.1,2 Yet, the positive psychological factors that affect morbidity and mortality3,4 have not been extensively studied in diverse oncologic populations compared with other medical populations4-8—although they could be extremely influential in a cancer population facing a life-threatening diagnosis.9,10 Positive psychological well-being (PPWB), a broad construct defined as “the positive cognitions, feelings, and strategies individuals use to evaluate their life favorably and function well,”4 includes indicators such as positive affect, gratitude, optimism, happiness, and life purpose.11 Although PPWB coexists with symptoms of distress, it is not simply the opposite of distress. For example, optimism and depression are only modestly inversely correlated.12 Many studies in medical populations have found that the beneficial effects of positive psychological health on clinical outcomes are independent of the adverse effects of negative psychological conditions like depression on clinical outcomes.4-8 Hence, the primary focus of alleviating symptoms of distress and psychiatric disorders to achieve optimal psychological health in oncology populations ignores an essential aspect of well-being: overcoming adversity and accentuating life-affirming perspectives that may enhance the positive aspects of well-being. Importantly, supporting PPWB should not be confused with the tyranny of positive thinking (ie, where patients feel pressured to think positively and may believe that failure to think positively is a character flaw that can lead to poor clinical outcomes and disease setbacks).13

The Positive Psychological Aspects of Well-Being in the Oncology Population

The positive aspects of psychological health are especially relevant for patients with cancer and their caregivers because PPWB factors can buffer against distress.14 Although significant distress accompanies a cancer diagnosis and treatment, the entire cancer care experience can also result in significant positive experiences such as strengthening connections with loved ones.15,16 Numerous studies have reported resilience and post-traumatic growth among patients with cancer and their caregivers.17-21 The experience of cancer can also allow individuals to reflect on their lives and re-evaluate their choices, resulting in more meaning and satisfaction in life.22 Furthermore, robust evidence supports that patients undergoing cancer treatment lean into their spirituality and re-engage in activities that enhance meaning and overall quality of life during and after cancer treatment.23 The existential threat of a cancer diagnosis and treatment can provide one of the first opportunities for most individuals to consider their own mortality seriously, perhaps resulting in a memento mori philosophy in which acknowledging the inevitability of death makes each day more gratifying.24 Thus, including positive psychological health in the routine psychological evaluation (currently mostly focused on distress screening) for all patients with cancer may be especially relevant and invaluable for patients to achieve holistic well-being during and after treatment25 and empower patients not just to survive but also to thrive regardless of early-stage or advanced cancer.26 As Gilda Radner famously said, “cancer changes your life, often for the better. You learn what's important, you learn to prioritize, and you learn not to waste your time. You tell people you love them. If it wasn't for the downside, having cancer would be the best thing, and everyone would want it. That's true. If it wasn't for the downside.”27

Just like distress, positive psychological factors could contribute to clinical outcomes in the cancer population via biologic and behavioral pathways.28,29 Empirical data, however, on biologic links between positive psychological health and clinical outcomes in serious illness populations are less robust and consistent, especially in the cancer population.30,31 A few studies in cardiac populations linked positive psychological factors with beneficial effects on inflammation32—an important component of tumorigenesis and the focus of cancer therapeutics.33,34 In a cross-sectional study of 950 individuals, Oreskovic and Goodman34 showed that dispositional optimism was associated with less inflammatory markers (interleukin-6: B = –0.03, P = .02) after adjusting for sociodemographic factors. Also, Ikeda et al35 reported that higher overall optimism scores were associated with lower levels of interleukin-6 and soluble intercellular adhesion molecules in 746 participants in the Normative Aging Study. Since inflammation plays an important role in the evolution of several cancers, the potential benefit of positive psychological factors in decreasing inflammation could be pertinent for patients with cancer. Hence, studies that specifically examine the association between positive psychological factors and inflammation in the oncology population could further advance the science of PPWB in medical populations.

The evidence is more extensive for healthy lifestyle behaviors (eg, physical activity, smoking cessation, and medication adherence) as a probable link between positive psychological factors and clinical outcomes in medical populations.36,37 Indeed, individuals who report more positive psychological factors are likely more cognitively flexible, more adept at problem solving to manage stressors, and more likely to use diverse positive coping strategies in overcoming barriers to important healthy lifestyle behaviors.38 For example, several studies have shown that positive psychological factors are associated with an increased likelihood of engaging in physical activity after controlling for sociodemographic, disease, and psychological factors.37

Since healthy behaviors such as avoiding smoking or smoking cessation are protective against several cancers,39 positive psychological factors could directly reduce the risk of cancer incidence via better health behaviors.40 Furthermore, known risk factors for malignancy such as tobacco use and physical inactivity are also established risk factors for chronic diseases (eg, cardiovascular disease and diabetes) among cancer survivors.41 Thus, if PPWB can reduce the barriers preventing cancer survivors from engaging in healthier behaviors that protect against chronic health conditions, its long-term impact on the oncology population could be substantial.

From Distress Screening to Psychological Well-Being Assessment

Increasing evidence that screening programs may help detect distress in patients with cancer has fueled the drive for distress screening for all oncology patients.42 We agree that it is essential that oncology clinicians assess the psychological and mental health of their patients at multiple points in their care cycle to ensure that psychological factors are not causing undue burden and suffering.43 Current guidelines for distress screening at cancer centers recommend the use of valid distress screening instruments such as a distress thermometer.44-47 However, this campaign is rather narrow and negatively focused and divides the population into distressed and not distressed. We advocate changing from distress screening to psychological well-being assessment with future aspirations of incorporating assessments for both negative and positive aspects of well-being. Hence, a discussion of PPWB could help patients and clinicians uncover potential gaps in resilience factors that undermine their overall well-being in the cancer care experience. Although some PPWB factors are considered trait constructs, many are closely associated with state constructs whose reassessment at key clinical junctures (eg, time of diagnosis and treatment change) could engage patients' innate strengths and resilience factors that influence their illness, treatment, and recovery experiences. Unlike distress and negative psychological factors that should be addressed expeditiously, the ultimate goal of having PPWB discussions should not only be to identify those who need intervention but also to uncover patients' inherent traits that inform how they engage with treatment and decision making. Conversely, state constructs (eg, positive affect) can fluctuate and change over time and might be more amenable to improvement with increased awareness of their influence in patients' lives. Indeed, assessing the full spectrum of psychological functioning multiple times during the care cycle acknowledges the breadth of responses to cancer and sets the aspirational goal of not only preventing or reducing distress but also cultivating resilience and other PPWB constructs in the lived experience of patients managing a cancer diagnosis, treatment, and recovery. A potential barrier to incorporating PPWB discussions in psychological health assessments is time constraints faced by oncology clinicians. However, PPWB discussions could easily be integrated into routine patient-reported outcome monitoring or current routine psychological health assessments completed by social workers with minimal extra training—prior positive psychological interventions in other medical populations were successfully delivered by social workers.48-51 Also, with effective use of digital health technologies for patient-reported outcome monitoring and the fact that most validated PPWB assessments (eg, the gratitude questionnaire52) are relatively short in length (ie, ≤ 10 questions), PPWB assessments could effectively be completed by patients remotely and reviewed systematically during routine social work visits without adding undue time burden to standard psychological health assessments. It is also possible that physicians would welcome an opportunity to discuss positive ways that patients are handling their diagnoses and treatment instead of solely focusing on distress and monitoring for complications.

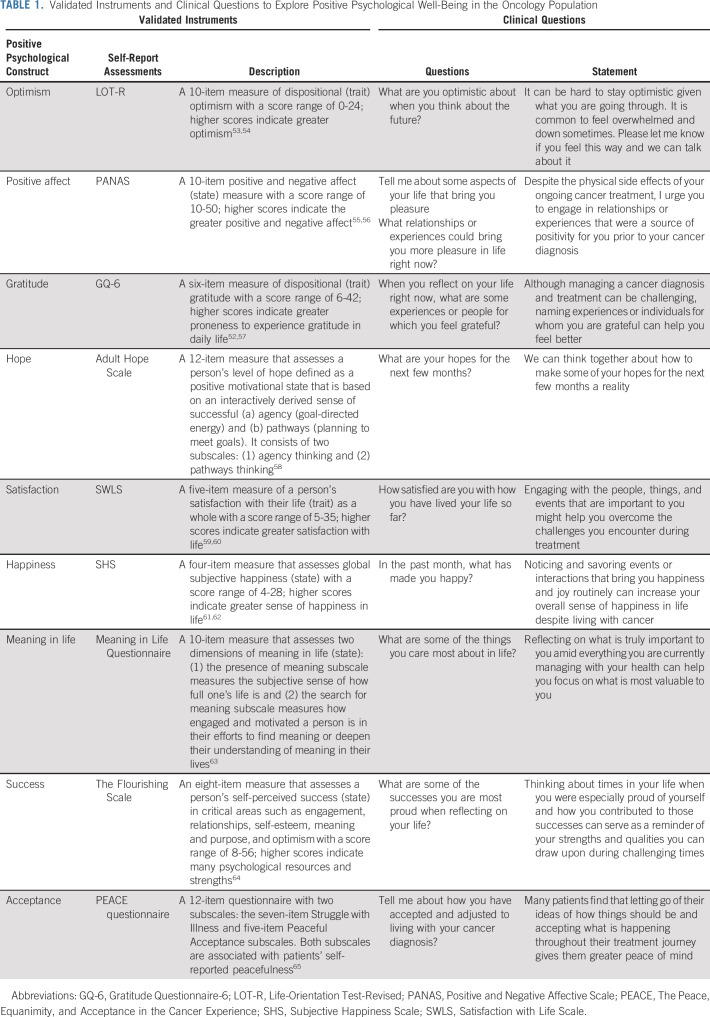

We acknowledge that just as distress screening creates a conundrum where patients who screen positive may not readily have access to much-needed psychosocial services, PPWB discussions may pose similar concerns in that clinicians may not know what to do with their findings. However, unlike assessing for distress, anecdotally, several specific questions (Table 1) about PPWB may be informative and can stimulate conversation about overall psychological well-being throughout the cancer care experience, inform treatment planning and prognostic awareness conversations, and be therapeutic without the need for involvement of mental health clinicians. Several studies in medical populations other than cancer4,51,66 show that PPWB can be increased by interventions and is not merely a reflection of a person's health status.8,38 Indeed, positive psychology interventions, which use deliberate and systematic activities (eg, gratitude letter) to foster PPWB and mitigate distress,8 can be delivered by clinicians with different training backgrounds. This includes those outside of specialty mental health care, allowing easier accessibility compared with other psychological treatments in cancer care settings.38,67 With growing evidence for the efficacy of positive psychology interventions for cancer populations, Rosenberg et al67 have shown that a positive psychology intervention focused on cultivating resilience in young adults with cancer delivered by trained bachelor-level nonclinical coaches is feasible and is associated with sustained improvements in psychological outcomes up to two years postintervention. A similar intervention for patients with more advanced disease was also feasible.26 Hence, positive psychological interventions could be customized for patients depending on their values, life circumstances, disease stage, and prognosis. For example, future-oriented PPWB constructs such as life purpose could be emphasized in patients with early-stage disease. By contrast, more reflective constructs like meaning in daily life could be emphasized in patients with advanced disease. Hence, interventions that focus on increasing a patient's life satisfaction, social support, life purpose, coping, and positive affect, in relation to their overall life circumstances and health, could be especially important for the cancer population during active cancer treatment and in their future lives.4,67

TABLE 1.

Validated Instruments and Clinical Questions to Explore Positive Psychological Well-Being in the Oncology Population

Recommendations

Overall, we advocate that enhancing PPWB during the entire cancer care cycle should go hand-in-hand with minimizing the negative psychological outcomes associated with the cancer care experience regardless of disease stage and prognosis. Despite the challenges of managing cancer and its treatment, the average patient with cancer wants to maintain an optimistic spirit, satisfaction with their life, and gratitude, as we have observed in patients with other medical conditions.4 Robust interventions to harness PPWB in both the short- and long-term are overdue in the cancer population. Suggestions for an investigation into PPWB in heterogeneous cancer populations are as follows: first, research that describes the trajectory of positive psychological health factors among patients with different cancers is essential to developing effective supportive oncology interventions and helps us identify relevant time points for intervention. Second, theory development, conceptual clarity, and research that describes the interaction between PPWB and distress in patients with cancer are needed—many questions remain about whether PPWB and distress are orthogonal versus parallel constructs. Third, although optimism is the most studied positive psychological factor among patients with medical illnesses, including cancer, studies examining other PPWB factors (eg, gratitude, perseverance, acceptance, and satisfaction) are needed. Fourth, further studies should evaluate PPWB intervention strategies (alone or integrated with other supportive care interventions) for improving health and quality of life. Fifth, more research is needed to describe which PPWB constructs yield the most benefit, are associated with better health and quality of life, and when they could or should be enhanced. Sixth, studies designed to dissect the biologic and behavioral mechanisms by which positive psychological factors affect clinical outcomes in cancer are also needed to further aid in intervention development. Ultimately, fostering PPWB in patients, regardless of their circumstances, could enhance patients' overall psychological health throughout their treatment and lived experience with cancer.

Areej El-Jawahri

Consulting or Advisory Role: AIM Specialty Health, Novartis, GlaxoSmithKline, Blue Note Therapeutics

Corey S. Cutler

Stock and Other Ownership Interests: Bluebird Bio, Verastem, Northwest Biotherapeutics, Actinium Pharmaceuticals, AlloVir, 2Seventy Bio

Honoraria: Omeros, Pfizer, Janssen

Consulting or Advisory Role: Incyte, Jazz Pharmaceuticals, CareDX, Mallinckrodt/Therakos, Sanofi, CTI BioPharma Corp, Equillium, Bristol Myers Squibb, Cimeio, Editas Medicine

Uncompensated Relationships: Kadmon

Joseph A. Antin

Consulting or Advisory Role: CSL Behring, Janssen, Pharmacosmos

Stephanie J. Lee

Honoraria: Wolters Kluwer, PER

Consulting or Advisory Role: EMD Serono, Pfizer, 4SC, Mallinckrodt/Therakos, Almirall Hermal GmbH, Rain Therapeutics

Research Funding: Kadmon, Amgen, Bristol Myers Squibb, EMD Serono, Incyte, Syndax, Pfizer, AstraZeneca

Patents, Royalties, Other Intellectual Property: Patent pending for high-affinity T-cell receptors that target the Merkel polyomavirus

Other Relationship: National Marrow Donor Program, Society for Investigative Dermatology (SID)

No other potential conflicts of interest were reported.

SUPPORT

Supported by the National Cancer Institute through Grant No. K08CA251654 (to H.L.A.) and the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society (A.E.-J. is a Scholar in Clinical Research of the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Administrative support: Hermioni L. Amonoo

Provision of study materials or patients: Hermioni L. Amonoo

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

Accountable for all aspects of the work: All authors

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Yin and Yang of Psychological Health in the Cancer Experience: Does Positive Psychology Have a Role?

The following represents disclosure information provided by authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated unless otherwise noted. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or ascopubs.org/jco/authors/author-center.

Open Payments is a public database containing information reported by companies about payments made to US-licensed physicians (Open Payments).

Areej El-Jawahri

Consulting or Advisory Role: AIM Specialty Health, Novartis, GlaxoSmithKline, Blue Note Therapeutics

Corey S. Cutler

Stock and Other Ownership Interests: Bluebird Bio, Verastem, Northwest Biotherapeutics, Actinium Pharmaceuticals, AlloVir, 2Seventy Bio

Honoraria: Omeros, Pfizer, Janssen

Consulting or Advisory Role: Incyte, Jazz Pharmaceuticals, CareDX, Mallinckrodt/Therakos, Sanofi, CTI BioPharma Corp, Equillium, Bristol Myers Squibb, Cimeio, Editas Medicine

Uncompensated Relationships: Kadmon

Joseph A. Antin

Consulting or Advisory Role: CSL Behring, Janssen, Pharmacosmos

Stephanie J. Lee

Honoraria: Wolters Kluwer, PER

Consulting or Advisory Role: EMD Serono, Pfizer, 4SC, Mallinckrodt/Therakos, Almirall Hermal GmbH, Rain Therapeutics

Research Funding: Kadmon, Amgen, Bristol Myers Squibb, EMD Serono, Incyte, Syndax, Pfizer, AstraZeneca

Patents, Royalties, Other Intellectual Property: Patent pending for high-affinity T-cell receptors that target the Merkel polyomavirus

Other Relationship: National Marrow Donor Program, Society for Investigative Dermatology (SID)

No other potential conflicts of interest were reported.

REFERENCES

- 1.Parry C, Kent EE, Mariotto AB, et al. : Cancer survivors: A booming population. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 20:1996-2005, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Miller KD, Nogueira L, Mariotto AB, et al. : Cancer treatment and survivorship statistics, 2019. CA Cancer J Clin 69:363-385, 2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kim ES, Hagan KA, Grodstein F, et al. : Optimism and cause-specific mortality: A prospective cohort study. Am J Epidemiol 185:21-29, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kubzansky LD, Huffman JC, Boehm JK, et al. : Positive psychological well-being and cardiovascular disease: JACC health promotion series. J Am Coll Cardiol 72:1382-1396, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Huffman JC, DuBois CM, Millstein RA, et al. : Positive psychological interventions for patients with type 2 diabetes: Rationale, theoretical model, and intervention development. J Diabetes Res 2015:428349, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Huffman JC, Millstein RA, Mastromauro CA, et al. : A positive psychology intervention for patients with an acute coronary syndrome: Treatment development and proof-of-concept trial. J Happiness Stud 17:1985-2006, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Levine GN, Cohen BE, Commodore-Mensah Y, et al. : Psychological health, well-being, and the mind-heart-body connection: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 143:e763-e783, 2021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Seligman ME, Steen TA, Park N, et al. : Positive psychology progress: Empirical validation of interventions. Am Psychol 60:410-421, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Amonoo HL, Barclay ME, El-Jawahri A, et al. : Positive psychological constructs and health outcomes in hematopoietic stem cell transplantation patients: A systematic review. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 25:e5-e16, 2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee SJ, Loberiza FR, Rizzo JD, et al. : Optimistic expectations and survival after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 9:389-396, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boehm JK, Peterson C, Kivimaki M, et al. : A prospective study of positive psychological well-being and coronary heart disease. Health Psychol 30:259-267, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huffman JC, Legler SR, Boehm JK: Positive psychological well-being and health in patients with heart disease: A brief review. Future Cardiol 13:443-450, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Levin TT, Applebaum AJ: Acute cancer cognitive therapy. Cogn Behav Pract 21:404-415, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chakhssi F, Kraiss JT, Sommers-Spijkerman M, et al. : The effect of positive psychology interventions on well-being and distress in clinical samples with psychiatric or somatic disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Psychiatry 18:211, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Adorno G, Lopez E, Burg MA, et al. : Positive aspects of having had cancer: A mixed-methods analysis of responses from the American Cancer Society study of cancer survivors-II (SCS-II). Psychooncology 27:1412-1425, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sharp L, Redfearn D, Timmons A, et al. : Posttraumatic growth in head and neck cancer survivors: Is it possible and what are the correlates? Psychooncology 27:1517-1523, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Seiler A, Jenewein J: Resilience in cancer patients. Front Psychiatry 10:208, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gori A, Topino E, Sette A, et al. : Pathways to post-traumatic growth in cancer patients: Moderated mediation and single mediation analyses with resilience, personality, and coping strategies. J Affect Disord 279:692-700, 2021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Greup SR, Kaal SEJ, Jansen R, et al. : Post-traumatic growth and resilience in adolescent and young adult cancer patients: An overview. J Adolesc Young Adult Oncol 7:1-14, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Menger F, Mohammed Halim NA, Rimmer B, et al. : Post-traumatic growth after cancer: A scoping review of qualitative research. Support Care Cancer 29:7013-7027, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shand LK, Cowlishaw S, Brooker JE, et al. : Correlates of post-traumatic stress symptoms and growth in cancer patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychooncology 24:624-634, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vos J: Meaning and existential givens in the lives of cancer patients: A philosophical perspective on psycho-oncology. Palliat Support Care 13:885-900, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Puchalski CM: Spirituality in the cancer trajectory. Ann Oncol 23:49-55, 2012. (suppl 3) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Noonan E, Little M, Kerridge I: Return of the memento mori: Imaging death in public health. J R Soc Med 106:475-477, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Amonoo HL, Kurukulasuriya C, Chilson K, et al. : Improving quality of life in hematopoietic stem cell transplantation survivors through a positive psychology intervention. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 26:1144-1153, 2020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fladeboe KM, O'Donnell MB, Barton KS, et al. : A novel combined resilience and advance care planning intervention for adolescents and young adults with advanced cancer: A feasibility and acceptability cohort study. Cancer 127:4504-4511, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Maxwell T: Being Single, with Cancer. A Solo Survivor's Guide to Life, Love, Health, and Happiness. New York, NY, Demos Medical Publishing LLC, 2014 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Puig-Perez S, Hackett RA, Salvador A, et al. : Optimism moderates psychophysiological responses to stress in older people with type 2 diabetes. Psychophysiology 54:536-543, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tindle HA, Duncan MS, Liu S, et al. : Optimism, pessimism, cynical hostility, and biomarkers of metabolic function in the Women's Health Initiative. J Diabetes 10:512-523, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cavanagh CE, Larkin KT: A critical review of the “undoing hypothesis”: Do positive emotions undo the effects of stress? Appl Psychophysiol Biofeedback 43:259-273, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Knight JM, Moynihan JA, Lyness JM, et al. : Peri-transplant psychosocial factors and neutrophil recovery following hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. PLoS One 9:e99778, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Coussens LM, Werb Z: Inflammation and cancer. Nature 420:860-867, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Roy B, Diez-Roux AV, Seeman T, et al. : Association of optimism and pessimism with inflammation and hemostasis in the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA). Psychosom Med 72:134-140, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Oreskovic NM, Goodman E: Association of optimism with cardiometabolic risk in adolescents. J Adolesc Health 52:407-412, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ikeda A, Schwartz J, Peters JL, et al. : Optimism in relation to inflammation and endothelial dysfunction in older men: The VA normative aging study. Psychosom Med 73:664-671, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kim ES, Kubzansky LD, Smith J: Life satisfaction and use of preventive health care services. Health Psychol 34:779-782, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Boehm JK, Chen Y, Koga H, et al. : Is optimism associated with healthier cardiovascular-related behavior? Meta-analyses of 3 health behaviors. Circ Res 122:1119-1134, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Amonoo HL, El-Jawahri A, Celano CM, et al. : A positive psychology intervention to promote health outcomes in hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: The PATH proof-of-concept trial. Bone Marrow Transplant 56:2276-2279, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Godtfredsen NS, Prescott E, Osler M: Effect of smoking reduction on lung cancer risk. JAMA 294:1505-1510, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hoeppner BB, Hoeppner SS, Carlon HA, et al. : Leveraging positive psychology to support smoking cessation in nondaily smokers using a smartphone app: Feasibility and acceptability study. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 7:e13436, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ko A, Kim K, Sik Son J, et al. : Association of pre-existing depression with all-cause, cancer-related, and noncancer-related mortality among 5-year cancer survivors: A population-based cohort study. Sci Rep 9:18334, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pirl WF, Fann JR, Greer JA, et al. : Recommendations for the implementation of distress screening programs in cancer centers: Report from the American Psychosocial Oncology Society (APOS), Association of Oncology Social Work (AOSW), and Oncology Nursing Society (ONS) joint task force. Cancer 120:2946-2954, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Muriel AC, Hwang VS, Kornblith A, et al. : Management of psychosocial distress by oncologists. Psychiatr Serv 60:1132-1134, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Linden W, Andrea Vodermaier A, McKenzie R, et al. : The psychosocial screen for cancer (PSSCAN): Further validation and normative data. Health Qual Life Outcomes 7:16, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB, et al. : An ultra-brief screening scale for anxiety and depression: The PHQ-4. Psychosomatics 50:613-621, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bruera E, Kuehn N, Miller MJ, et al. : The edmonton symptom assessment system (ESAS): A simple method for the assessment of palliative care patients. J Palliat Care 7:6-9, 1991 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Roth AJ, Kornblith AB, Batel-Copel L, et al. : Rapid screening for psychologic distress in men with prostate carcinoma: A pilot study. Cancer 82:1904-1908, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Celano CM, Beale EE, Mastromauro CA, et al. : Psychological interventions to reduce suicidality in high-risk patients with major depression: A randomized controlled trial. Psychol Med 47:810-821, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Celano CM, Gomez-Bernal F, Mastromauro CA, et al. : A positive psychology intervention for patients with bipolar depression: A randomized pilot trial. J Ment Health 29:60-68, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Huffman JC, Albanese AM, Campbell KA, et al. : The positive emotions after acute coronary events behavioral health intervention: Design, rationale, and preliminary feasibility of a factorial design study. Clin Trials 14:128-139, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Huffman JC, Mastromauro CA, Boehm JK, et al. : Development of a positive psychology intervention for patients with acute cardiovascular disease. Heart Int 6:e14, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.McCullough ME, Emmons RA, Tsang JA: The grateful disposition: A conceptual and empirical topography. J Pers Soc Psychol 82:112-127, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Scheier MF, Carver CS, Bridges MW: Distinguishing optimism from neuroticism (and trait anxiety, self-mastery, and self-esteem): A reevaluation of the Life Orientation Test. J Pers Soc Psychol 67:1063-1078, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Millstein RA, Chung WJ, Hoeppner BB, et al. : Development of the state optimism measure. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 58:83-93, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Watson D, Clark LA, Tellegen A: Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. J Pers Soc Psychol 54:1063-1070, 1988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Määttänen I, Henttonen P, Väliaho J, et al. : Positive affect state is a good predictor of movement and stress: Combining data from ESM/EMA, mobile HRV measurements and trait questionnaires. Heliyon 7:e06243, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Emmons RA, Froh J, Rose R: Gratitude, in Gallagher MW, Lopez SJ (eds): Positive Psychological Assessment: A Handbook of Models and Measures. Washington, DC, American Psychological Association, 2019, pp 317-332 [Google Scholar]

- 58.Snyder CR: Target article: Hope theory: Rainbows in the mind. Psychol Inq 13:249-275, 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 59.Diener E, Emmons RA, Larsen RJ, et al. : The satisfaction with life scale. J Pers Assess 49:71-75, 1985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kaczmarek LD, Bujacz A, Eid M: Comparative latent state–trait analysis of satisfaction with life measures: The Steen Happiness Index and the Satisfaction with Life Scale. J Happiness Stud 16:443-453, 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lyubomirsky S, Lepper HS: A measure of subjective happiness: Preliminary reliability and construct validation. Soc Indicators Res 46:137-155, 1999 [Google Scholar]

- 62.Veenhoven R: Is happiness a trait? in Citation Classics From Social Indicators Research. Dordrecht, the Netherlands, Springer, 2015, pp 477-536 [Google Scholar]

- 63.Steger MF, Frazier P, Oishi S, et al. : The meaning in life questionnaire: Assessing the presence of and search for meaning in life. J Couns Psychol 53:80-93, 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 64.Diener E, Wirtz D, Tov W, et al. : New well-being measures: Short scales to assess flourishing and positive and negative feelings. Soc Indicators Res 97:143-156, 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 65.Mack JW, Nilsson M, Balboni T, et al. : Peace, equanimity, and acceptance in the cancer experience (PEACE): Validation of a scale to assess acceptance and struggle with terminal illness. Cancer 112:2509-2517, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Huffman JC, Golden J, Massey CN, et al. : A positive psychology-motivational interviewing intervention to promote positive affect and physical activity in type 2 diabetes: The BEHOLD-8 controlled clinical trial. Psychosom Med 82:641-649, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Rosenberg AR, Zhou C, Bradford MC, et al. : Assessment of the promoting resilience in stress management intervention for adolescent and young adult survivors of cancer at 2 years: Secondary analysis of a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw Open 4:e2136039, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]