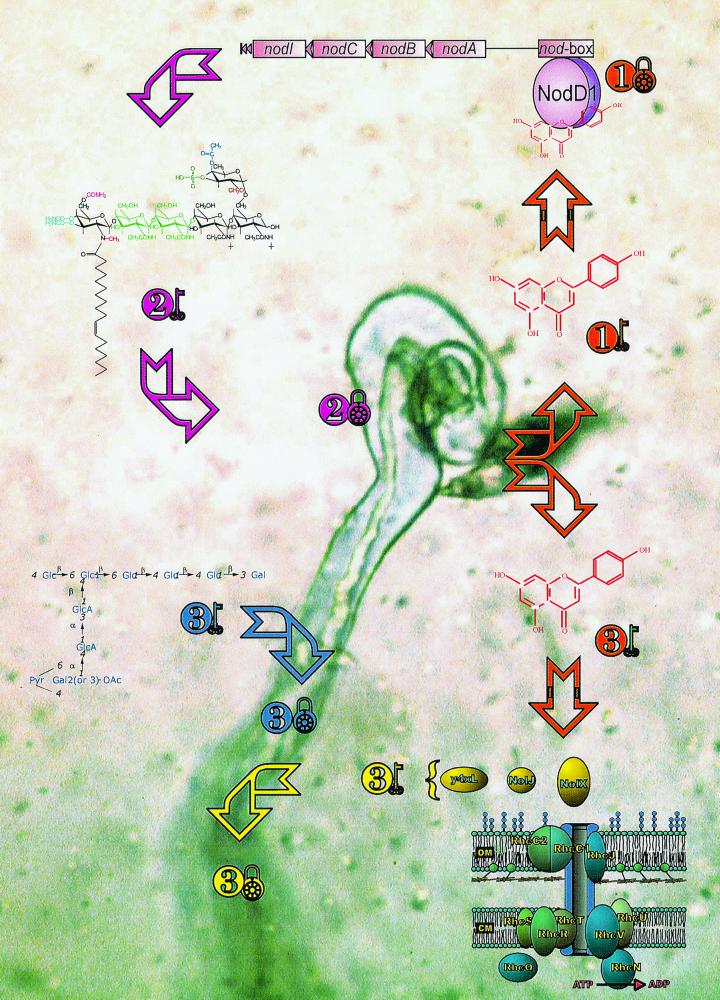

At least three different sets of symbiotic signals (here, they are compared to locks and keys) are exchanged between legumes and rhizobia during nodule development. Flavonoids, the first of these, emanate from the plant and interact with rhizobial NodD proteins that serve as both environmental sensors and activators of transcription. A second set of signals is synthesized when NodD-flavonoid complexes activate transcription from nod boxes. Most of the genes immediately downstream of these promoters are involved in the synthesis of lipo-oligosaccharidic Nod factors that provoke deformation of root hairs and allow rhizobia to enter the root through infection threads. Fine-tuning of transcription of nodulation (nod) genes is probably related to sequence variations in individual nod boxes (there are 19 on the symbiotic plasmid of the broad-host-range Rhizobium sp. strain NGR234). Other rhizobial products seem to be necessary for continued infection thread development, and these represent a third set of signals. Among them are extracellular polysaccharides (EPS) and related compounds, as well as proteins exported by the type three secretion system (TTSS). In the latter case, flavonoids also activate protein secretion, suggesting that the same keys can unlock different doors.

Symbioses are nearly ubiquitous, and many are also persistent (56). Mutualistic, nitrogen-fixing associations between members of the plant family Leguminosae, and the soil bacteria Azorhizobium, Bradyrhizobium, Mesorhizobium, and Rhizobium (collectively called rhizobia) contribute substantially to plant productivity (111). Legume-Rhizobium symbioses are marriages between two vastly different genomes. In rhizobia, these include a chromosome plus zero to many plasmids, totalling 6 to 9 Mbp (71). In contrast, genomes of legumes are much larger, some comprising more than 20 chromosomes with total DNA contents that range from about 450 to 4,500 Mbp per haploid genome (1C) (1). As examples, the model legumes Lotus japonicus and Medicago truncatula have six or eight chromosomes totalling 450 and 500 Mbp/1C (14), respectively. Common beans (Phaseolus vulgaris) and related species (e.g., Vigna unguiculata) (both genera belong to the tribe Phaseoleae) have 11 chromosomes each (24) with DNA contents of 637 (1) and 540 Mbp/1C (50). Furthermore, several widely cultivated legumes such as Arachis hypogaea, Glycine max, and Medicago sativa are effectively polyploid, although in G. max most loci segregate as if they were diploid. Legume genomes are thus at least 50 times larger than those of their microsymbionts. Given this disparity, it is difficult to imagine that theirs is a marriage of equals. Nevertheless, their respective contributions are probably not vastly different (see reference 48).

LEGUME BOWERS ARE DECORATED WITH FLAVONOIDS

Which partner initiates contact? Since plants are nonmotile, it is tempting to think that courtship begins when bacteria advance into the legume rhizosphere. Yet chemotaxis and motility among rhizobia are clearly not essential for nodulation (see reference 30). Rather than “love at first sight” other, more subtle factors help the partners match each other. Foremost among these are phenolic substances, especially flavonoids. Although small quantities are excreted continuously, flavonoid concentrations in the rhizosphere increase in response to compatible rhizobia (82, 94, 117). In turn, rhizobia use these plant products for their own ends. Some flavonoids induce the expression of nodulation (nod, noe, and nol) and related genes (see reference 12), while others are catabolized (15, 79, 80). Degradation leads first to the appearance of chalcones, which can be more efficient inducers of nod genes than the flavonoids themselves (41).

Plant “attractiveness” probably correlates with the spectrum of phenolic compounds (especially flavonoids) that it secretes. Rhizobia respond to these advances through NodD and related proteins which act as both sensors of the environment and activators of transcription (93). Once derepressed, nodulation and other genes direct the synthesis and release of substances that profoundly affect legume roots (see below). It is as if plants construct elaborate “bowers,” replete with flavonoids and other attractants, to entice rhizobia towards them. If this bower analogy reflects reality, then the various types of bower should mirror legume host range. This poses two questions. Do bowers exist? And if yes, are their decorations unique? Although it is impossible, given the limited information available to definitively answer these questions, a tentative yes seems to be the most likely answer to the first for the following reasons. (i) Legumes support considerably larger rhizosphere populations than nonlegumes do (see reference 3). (ii) These larger populations are enriched in rhizobia (see reference 10). (iii) The roots of M. sativa are surrounded by a coarse, granular, mucilaginous material contained within a membranous layer of greater electron density (17). Rhizobia penetrate this outer “membrane” and form an almost continuous layer five to ten cells deep. (iv) Rhizobia rapidly proliferate around the roots of developing legumes (see reference 10). (v) Although the evidence is not completely consistent, there are indications that production of nod gene-inducing flavonoids is restricted to the elongating root hair zone from which most nodules later develop (117).

It is as if niches in the legume rhizosphere are tailored to rhizobia, but the question remains—are these niches especially enticing? Almost all constituents of a plant can make their way into the rhizosphere at some time or other (112). Exudates from living roots include amino acids, CO2, hormones (including ethylene), organic acids, phenolic substances, sugars, vitamins, etc., as well as polysaccharides and proteins (particularly enzymes) (73, 74). Among other roles, this carbon efflux attracts organisms (both mutualistic and pathogenic) towards the roots. Stachel et al. (98, 99) were probably the first to use fusions between reporter genes and inducible loci of soil bacteria to monitor the effect of plant secretions on the activity of microbial genes. Similar techniques were rapidly applied to rhizobia (31, 72, 83), with the result that flavonoids produced via the phenylpropanoid biosynthetic pathway were identified as the strongest inducers of nod gene expression (see references 100 and 110). Significant differences in the flavonoid compositions of seeds, roots, and root exudates of G. max, P. vulgaris, M. sativa, Trifolium repens, and Vicia sativa exist (see reference 70). Many flavonoids are stored and released as glycosides or related conjugates (58). These conjugates, which are more soluble in water than aglycones, are usually less active in inducing nod genes, but they diffuse readily and can be hydrolyzed to more-active substances (40).

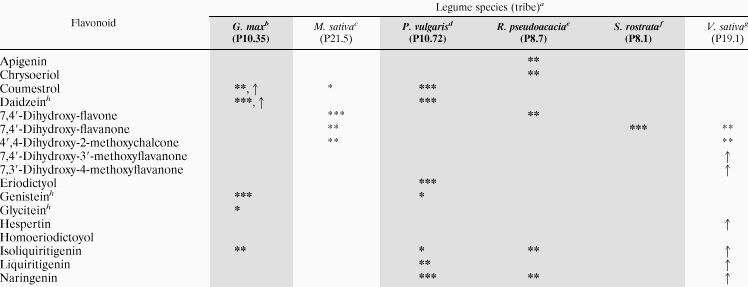

What is important, however, is the composition and concentration of the flavonoid mixture that is liberated into the rhizosphere by the future hosts. Perhaps not surprisingly, there is much less available data on this (Table 1). Of the six legumes analyzed, two have restricted host ranges (Medicago and Vicia), but four of the six (G. max, P. vulgaris, Robinia pseudoacacia, and Sesbania rastrata) can be nodulated by the broad-host-range Rhizobium sp. strain NGR234. In other words, these four legumes form nodules with NGR234 in addition to their homologous Rhizobium, implying that these hosts are relatively nonselective for rhizobia. Indeed, P. vulgaris is known to be promiscuous (61). To various degrees, this also applies to various soybean cultivars (53), and probably also to R. pseudoacacia (59, 89; W. J. Broughton, unpublished data). It is therefore reasonable to ask if a broad-host-range key is hidden among the quantities and patterns of flavonoids secreted by the roots of P. vulgaris. Although it seems as if P. vulgaris secretes higher concentrations of a larger spectrum of flavonoids than the other legumes, little of this data is truly quantitative. Furthermore, developmental, environmental, and nutritional factors influence secretion into the rhizosphere, rendering the interpretation of interspecies data even more difficult (91). Thus, although it remains likely that flavonoids in the rhizosphere are a key to host range, a definitive answer to this question must await detailed, quantitative analyses of secretions from a range of legumes.

TABLE 1.

nod gene-inducing flavonoids in secretions from the roots of legumes

|

The species shown shaded are nodulated by Rhizobium sp. strain NGR234. Symbols: ***, abundant; **, easily detectable; *, present in traces; ↑, exudation induced by compatible rhizobia.

Data from reference 91.

Data from reference 60.

Data from V. sativa subsp. nigra from reference 81.

Acetyl, glucosyl, and malonyl derivatives of these compounds are also found in exudates from G. max roots (97).

MIXED COUPLES—FLAVONOIDS AND TRANSCRIPTIONAL ACTIVATORS

In addition to being catabolized, flavonoids interact with a class of transcriptional activators of the LysR family that bind to highly conserved 49-bp DNA motifs (nod boxes) found in the promoter regions of many nodulation loci. These NodD proteins act both as sensors of the plant signal and as activators of transcription of nod loci. Although NodD proteins bind to nod boxes even in the absence of an inducer, flavonoids and related substances are generally required for the expression of nod genes. NodD proteins are localized in the cytoplasmic membrane of Rhizobium leguminosarum biovar viciae, where an inducing flavonoid, naringenin, also accumulates. Direct binding of inducers to NodD has not been demonstrated, but point mutations in nodD affect recognition of inducing molecules and cause extension of host range. NodD proteins also share conserved ligand-interacting domains with various nuclear receptors (see references 12 and 70).

Despite the fact that nodD genes are present in all rhizobia, their symbiotic characteristics vary from one species to anotherSome strains, such as R. leguminosarum bv. trifolii, have only one nodD gene, and in these cases, its mutation renders the strain incapable of nodulation (Nod−). In contrast, Bradyrhizobium japonicum, strain NGR234, Rhizobium meliloti, and Rhizobium tropici possess two to five copies of nodD. In R. meliloti, mutation of all three nodD copies is required to abolish nodulation, whereas inactivation of nodD1 is sufficient to render NGR234 Nod− (Fig. 1). nodD products of various Rhizobium species respond in different ways to flavonoids, and NodD homologues from the same strain may have various flavonoid preferences. Synergistic interactions between different secreted flavonoids have also been reported (97). In R. meliloti, NodD1 is activated when cells are supplied with a complex plant seed extract or the flavonoid luteolin. NodD2 only derepresses transcription when supplied with the complex extract, not with purified luteolin, while NodD3 apparently modulates the expression of nod genes even in the absence of any plant factor. Together with syrM, nodD3 of R. meliloti constitutes a self-amplifying positive regulatory circuit that is involved in regulation of nod genes within the developing nodule. In contrast, NodD1 of NGR234 responds to a wide range of inducing molecules which include phenolics that are inhibitors in other rhizobia (e.g., vanillin and iso-vanillin), as well as several estrogenic compounds (2). Transfer of the nodD1 gene of NGR234 to restricted-host-range rhizobia extends the nodulation capacity of the recipients to new hosts that include the nonlegume Parasponia andersonii (4, 70).

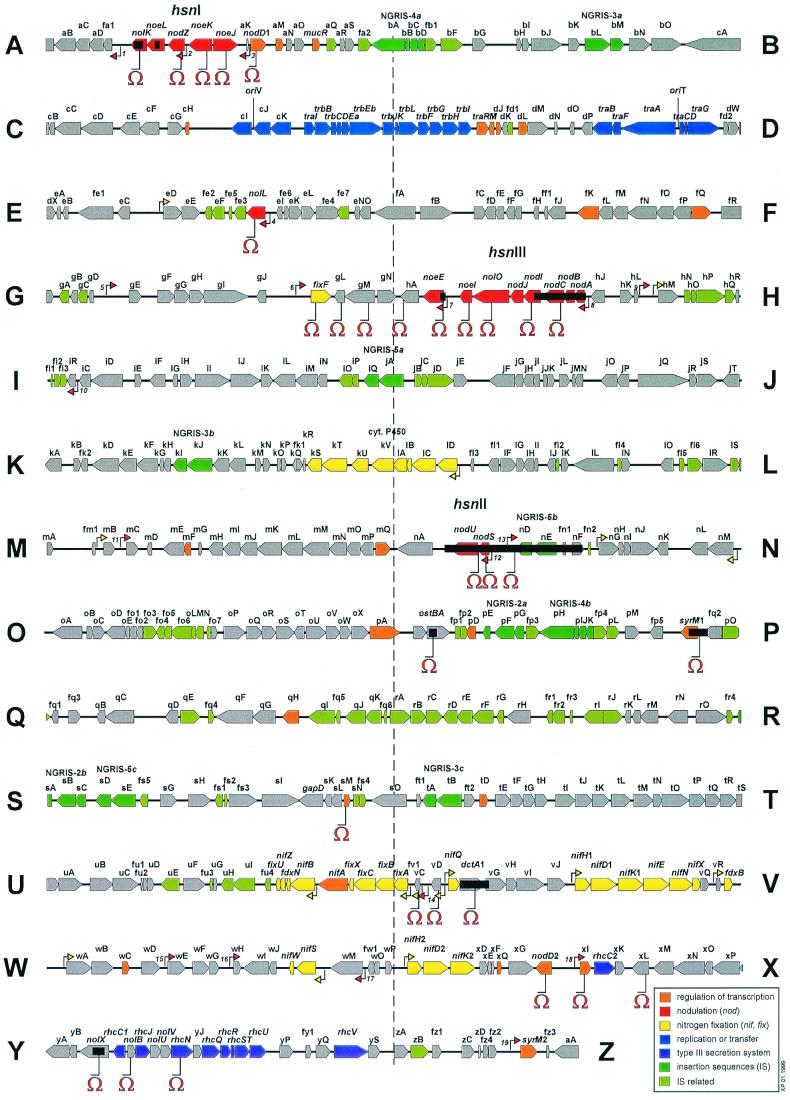

FIG. 1.

Genetic and physical map of the symbiotic plasmid (pNGR234a) of the broad-host-range Rhizobium sp. strain NGR234 (data from Freiberg et al. [33]). Arrows show the direction of transcription. Colors are used to group the genes and open reading frames into functional classes (color key). Small, numbered red arrows mark the position and orientation of the 19 nod boxes. Similarly, small, yellow arrows mark the position and orientation of NifA-ς54 promoters. Ω (omega cassette) marks the position of insertion or deletion (accompanying black boxes) mutations in various loci or genes. Only mutants containing the Ω insertion in nodD1 (sector A) (84) or the deletion of nodABC (sector H) are Nod− on all plants tested (84).

Given the above, do flavonoid keys and NodD protein locks control bacterial access to legumes? (Fig. 2). Some correlations between the spectrum of flavonoids able to interact with NodD proteins and the broadness of host range exist. Nevertheless, variations in the ability of these proteins to differentially sense inducing molecules and regulate the expression of nod genes are insufficient to explain host specificity. Furthermore, other species-specific sensor-activator systems contribute to the control of bacterial host range. For instance, nodV and nodW of B. japonicum are essential for the nodulation of Macroptilium atropurpureum, Vigna radiata, and V. unguiculata but contribute only marginally to the symbiosis with G. max. Thus, alternatives to NodD- and flavonoid-sensing regulatory systems coexist (35, 54, 70).

FIG. 2.

Keys to symbiotic harmony. This model is based on Rhizobium sp. strain NGR234 and its association with legumes. The flavonoid shown is apigenin, an activator of NodD1 of NGR234 (2). The NodNGR factors are redrawn from Price et al. (75), the EPS is redrawn from Djordjevic and Rolfe (22), and the TTSS is redrawn from Viprey et al. (109). The background shows a light micrograph of a root hair of Macroptilium atropurpureum infected with NGR234 (courtesy of P. Rochepeau).

Special mechanisms that down-regulate expression of nod genes are apparently required for optimal nodulation of M. sativa by R. meliloti and of Pisum sativum by R. leguminosarum bv. viciae strain Tom (70). In R. meliloti, NolR represses the transcription of the nodD genes as well as those genes necessary for the synthesis of the core Nod factor structures (nodABC). In B. japonicum, repression of nod gene expression by NolA is probably an indirect effect mediated perhaps by nodD2. B. japonicum nolA, and R. meliloti nolR mutants retain the ability to nodulate their respective hosts, albeit at lower efficiency, suggesting that fine-tuning of nod gene expression is required for optimal nodulation (55). Similarly, a nodD2 mutant of NGR234 (Fig. 1) fails to repress expression of the nodABCIJnolOnoeI operon after the initial flavonoid induction and, in contrast with the wild-type strain, is unable to form nitrogen-fixing nodules on V. unguiculata and Cajanus cajan.

As an added complexity, the symbiotic plasmid of NGR234 (pNGR234a) carries 19 nod boxes (Fig. 1), five of which control the expression of the known nod operons nodABCIJnolOnoeI, nodSU, nodZ, noeE, and nolL (33). Apparently, nod boxes with up to 11 base mismatches (compared to the consensus sequence) are still functional and regulate gene expression in a NodD1-dependent manner (68). It is possible, however, that some of these nod boxes have higher affinities for certain NodD1-inducer complexes over others. Thus, a microsymbiont such as NGR234 has many possibilities for optimizing expression of nod genes. First, NodD1 may interact with a spectrum of inducing molecules to produce complexes that could trigger transcription from selected nod boxes. Second, supplementary activators of transcription (e.g., SyrM1 [38] and y4xI [109]) could, together with NodD1, form a regulatory network that exerts interlaced control over dispersed nodulation loci. Third, repressors such as NodD2 and NolR (29) further modulate nod gene expression. Together, these systems control the expression of nodulation genes in a host-specific way, possibly resulting in the secretion of different sets of molecular signals.

NOD FACTORS AND BETROTHAL

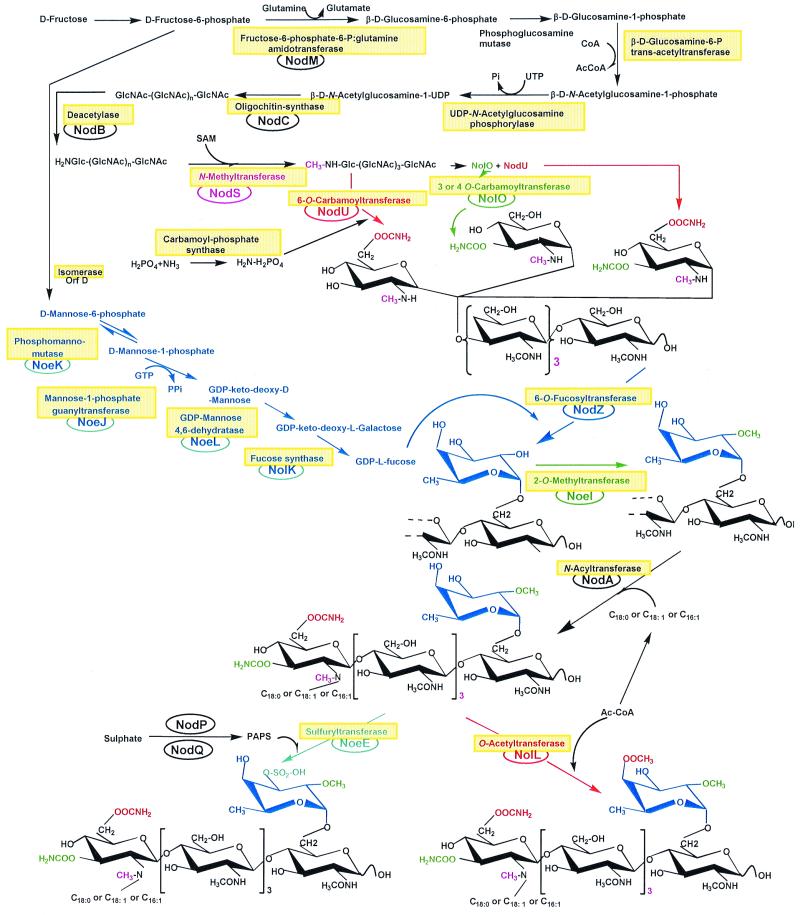

Flavonoid activation of nod genes results in the synthesis and secretion of a family of lipo-chito-oligosaccharidic Nod factors. Assembly of the chitin backbone is performed by an N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase encoded by nodC (Fig. 3). Chain elongation by NodC takes place at the nonreducing terminus. Then, the deacetylase NodB removes the N-acetyl moiety from the nonreducing terminus of the N-acetylglucosamine oligosaccharides. Finally, an acyltransferase coded by nodA, links the acyl chain to the acetyl-free carbon C-2 of the nonreducing end of the oligosaccharide (Fig. 3). Simple Nod factors comprising three to six N-acetyl-d-glucosamine residues and an acyl chain from the general fatty acid metabolism have biological activity (62). Basic Nod factors as well as their more sophisticated cousins are mitogenic, a trait that they share with plant hormones (see reference 86). Yet they are unique in provoking curling of the root hairs (Hac), and it is within the folds of highly curled root hairs that rhizobia gain entry into the plant. Is it possible that Nod factors are also keys to legume doors (Fig. 2)? Proof that Nod factors are able to unlock legume doors was obtained by using various rhizobial mutants that are unable to synthesize Nod factors (and thus nodulate) and “complementing” them for nodulation by the external addition of Nod factors. Simultaneous addition of NodNGR factors and nodABC mutants of NGR234 or B. japonicum USDA110 to the roots of G. max, Macroptilium atropurpureum, and V. unguiculata permits these strains to nodulate and fix nitrogen on their respective hosts (85, 86). NodNGR factors also allow Rhizobium fredii strain USDA257 to nodulate the nonhost Calopogonium caeruleum (85). Similarly, coapplication of purified A. caulinodans Nod factors and a nodA mutant of the same strain restores formation of outer cortical infection pockets in S. rostrata (19).

FIG. 3.

Synthesis of Rhizobium sp. strain NGR234 Nod factors. This scheme is adapted from that proposed by Hanin et al. (39) with permission of the publisher and has been updated by incorporating data from Broughton and Perret (12) and Perret et al. (70). Abbreviations: Ac, acetate; Ac-CoA, acetyl coenzyme A; CoA, coenzyme A; GlcNAc, N-acetyl-d-glucosamine; PAPS, 3′-phosphoadenosine 5′-phosphosulfate; SAM, S-adenosylmethionine.

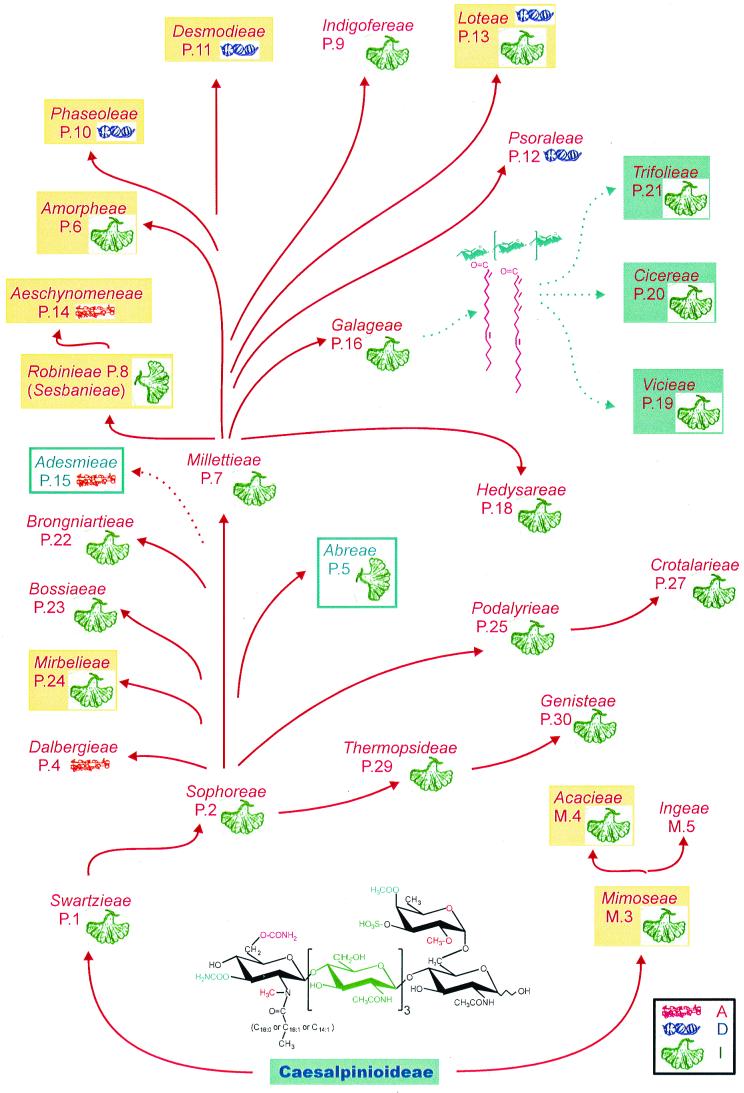

Although it seems clear from the above that Nod factors are keys, another question must be asked—“do different Nod factor keys exist?” In fact, most Nod factors are modified in species-specific ways, suggesting that each Rhizobium produces a different set of keys (examples of some of the modifications found are shown in Fig. 4). Yet in itself, this is not proof that these various keys fit different locks. A recent report stated that “The results demonstrate that none of the studied substitutions (to Nod factors of A. caulinodans) is strictly required for triggering normal nodule formation” (20). Perhaps instead, legume locks recognize common motifs, which would imply that Nod factors are more like master keys that are able to open many legume doors.

FIG. 4.

Overview of the nodulation capacities of the Leguminosae and selected rhizobia (adapted from Pueppke and Broughton [77] with permission of the publisher). Tribes of the Leguminosae nodulated by the broad-host-range Rhizobium sp. strain NGR234 are marked in red, while tribes not nodulated by NGR234 are boxed in blue. Red arrows reflect possibly evolutionary relationships. Types of nodules produced on legumes of the different tribes are denoted by pictograms (red for the aeschynomenoid [A] type, blue for the determinate [D] type, and green for indeterminate [I] nodules). Note that both types of nodules are found within the Loteae (see reference 77). Those tribes shown in yellow boxes are known to include promiscuous species (defined here as Nod+ with three or more Rhizobium species or isolates from three or more different legume genera). Little is known about the rhizobial (or Nod factor) requirements of the Abreae and Adesmieae. In contrast, how R. leguminosarum bv. vicieae, R. leguminosarum bv. trifolieae, and R. meliloti interact with the Cicereae, Vicieae, and Trifolieae has been well studied. Each of these tribes has strong preferences for Nod factors containing polyunsaturated acyl chains (shown in fuchsia). All the other tribes have a requirement for one or more members of the family of NodNGR factors shown at the bottom of the diagram. The data for the different tribes and species were taken from the following references and sources: Acacieae (Acacia farnesiana), Trinick (101); Aeschynomeneae (Arachis hypogaea), Wong et al. (115); Amporheae (Amorpha fruticosa) Wilson (114); Desmodieae (Desmodium infortum and Desmodium uncinatum), Lewin et al. (53) and H. Meyer z.A. and W. J. Broughton, unpublished data; Loteae (Lotus pedunculatus), Lewin et al. (53) and Meyer z.A. and Broughton, unpublished; Mimoseae (Leucaeana leucocephala, Mimosa invisa, and Mimosa pudica, Lewin et al. (53), Trinick (101); Mirbelieae (Chorizema ilicifolium), Wilson (114); Phaseoleae (Centrosema pubescens, Centrosema virginininianum, G. max, Lablab purpureus, M. atropurpureum, Phaseolus coccineus, P. vulgaris, Psophocarpus tetragonolobus, and Vigna unguiculata), Broughton et al. (11), Ikram et al. (47), Ikram and Broughton (45), Faizah et al. (27), Ikram and Broughton (46), Wilson (114), Lewin et al. (53), Trinick (101), Michiels et al. (61), and Meyer z.A. and Broughton, unpublished; and Robinieae (Robinia pseudoacacia, Sesbania drummondii, and Sesbania grandiflora), Wilson (114), Trinick (101), McCray-Batzli et al. (59), Schäfers and Werner (89).

Initially, classification of rhizobia was based predominantly on the legume from which it was isolated (43). Only in the early 1960s were extensive microbiological criteria used to separate rhizobia into different groups (36, 63). With the dawning of modern rhizobiology, it became obvious that rhizobia are not restricted to one host or at best a few hosts. Indeed, diverse soil bacteria possess variable capacities to nodulate legumes. Some are more or less dedicated to the legume from which they were isolated, but others are promiscuous and can form effective, nitrogen-fixing associations with many genera of legumes (70). An overview of the legumes' rhizobial requirements (in particular their Nod factors), as well as an indication of legume host range, is presented in Fig. 4. Several trends are obvious. First, at least nine legume tribes have extended preferences for rhizobia (those shaded in yellow). Second, promiscuous hosts are found among tribes possessing both determinate and indeterminate nodules. Third, as promiscuous hosts exist in both relatively primitive and advanced tribes, broad host range is probably the ancestral trait. Fourth, restricted host range, as evinced by the tribes Cicereae, Vicieae, and Trifolieae, is probably a specialization that is peculiar to a specific geographic niche (Middle East and Europe). It is manifested mostly by a requirement for Nod factors containing polyunsaturated fatty acids (12).

It thus seems as if the first Nod factors were indeed the equivalent of master keys and that in many instances, they have retained this function. “Baroque” modifications, which presumably evolved later, have served two purposes. One is a form of specialization which probably restricts host range as in the examples described above, while the other effect has been to render the molecules more stable, particularly in the rhizosphere (see reference 70).

NODULES, THE CONJUGAL ABODE

Nod factors allow rhizobia to enter the plant but do not guarantee successful symbiosis. Other inputs, from both partners, are necessary for this. Rhizobia enter roots along corridors in root hairs that are largely constructed by the plant and called infection threads (Fig. 2). Although Nod factors probably initiate infection thread development (105), it is not unreasonable to assume that in entering a “house” of the plant's making, the rhizobia need to make certain changes for their own comfort. Failure to do so results in abortion of infection threads, a process in which phenolic substances accumulate, triggering a hypersensitive reaction (108). One essential modification to the corridor is insulation to protect the rhizobia from the plant cytoplasm (103). Part of this insulation is seen as the peribacteroid or symbiosome membrane in infected cortical cells (113). What is it made of? In 1977, Dart (16) summarized the premolecular era knowledge of infection threads as follows. “Histochemically the thread wall contains the same components of pectic substances, hemicelluloses, and some cellulose, as the root hair tip, and electron micrographs of infection threads in root hairs and nodules show similar structure to the primary wall of plant cells”. And further “Rhizobium is presumed to produce the ‘zoogloeal matrix surrounding the bacteria …’ which probably contain ‘mucopolysaccharides.’”

The infection thread wall is unlikely to be a simple introgression of the root hair wall, however, as it is more resistant to treatment with cell wall-degrading enzymes (42). Furthermore, overexpression of an Erwinia carotovora extracellular cellulase produced by R. fredii (51) had no effect on nodulation of V. unguiculata, confirming Higashi et al.'s findings (42). Obviously, the infection thread is difficult to purify, so most indications have come from indirect analyses, by using methods that involve microscopy or by studying the effects of mutations. Mutations in both bacterial (7, 21, 64, 65, 104) and plant (32, 102, 116) genes and their effect on infection thread development have been reported. Some of the rhizobial genes that play a role in infection thread development are involved in synthesis of various polysaccharides that range from alternating β-linked residues of mannose and 3-deoxy-d-manno-2-octulosonic acid, through branched exopolysaccharides of R. meliloti and NGR234, to the cyclic glucans of B. japonicum (Table 2). Perhaps the products of these genes are required for infection thread formation on certain plants, but not on others (69, 70). How they function or where they are located within the infection thread has not been elucidated. It is also possible that extracellular carbohydrates help suppress defense reactions in the plant (52).

TABLE 2.

Components of infection threads of legume root hairs invaded by rhizobiaa

| Infection thread component | Location | Reference(s) or source |

|---|---|---|

| Legumes | ||

| Arabinogalactan (PsENOD5) | Lumen? | Scheres et al. (92) |

| ATPase | PBMb | Fedorova et al. (28) |

| Cellulose | Wall | Rae et al. (78) |

| Extensin (MtN12, VfNDS-E) | Matrix | VandenBosch et al. (106); Brewin et al. (9); N. J. Brewin, personal communication |

| Lipoxygenase | Lumen | Gardner et al. (34) |

| Pectin | ||

| Esterified | Wall | Rae et al. (78) |

| Nonesterified | Wall | Rae et al. (78) |

| Proline-rich proteins including ENOD12 | Matrix | Sherrier and VandenBosch (95) |

| Xyloglucan | Wall | Rae et al. (78) |

| Rhizobium | ||

| Cyclic β-(1,6)-β-(1,3)-glucans | ? | Dunlap et al. (25) |

| EPS | ? | van Workum et al. (107), Rolfe et al. (88), Skorupsa et al. (96), Niehaus et al. (67) |

| Lipopolysaccharides | Lumen | Dazzo et al. (18); Brewin, personal communication |

| Succinoglycan | ? | Cheng and Walker (13) |

| Secreted proteins (NolJ, NolX, y4xL, etc.)c | ? | W. J. Deakin, H. B. Krishnan, and C. Marie, personal communication |

| NodO | ? | Downie (23) |

More recently, other rhizobial secretion products have also been implicated in nodulation of particular plants. Many rhizobia possess a TTSS. Included among the proteins secreted via this machinery are NolJ, NolX, and y4xL (109; W. J. Deakin, H. B. Krishnan, and C. Marie, personal communication). Transcription of the genes encoding these proteins is dependent on NodD and flavonoids but occurs later than nod genes, implying that the secreted proteins play a role within the plant (109). As the same genes are not expressed in nodules, they are most probably expressed in infection threads. Null mutations in genes controlling TTSS secretion result in phenotypes that vary with the plant host. One explanation of why rhizobia that are unable to secrete carbohydrates and/or proteins have contrasting effects on their hosts concerns the possibility that certain plants produce homologues of these molecules (70). A sort of functional complementation could therefore exist, and only when a plant lacking the homologue was challenged with rhizobia mutated in the same gene, would an effect on infection thread development be seen. Similarly, although this has been less well-documented, plant mutants that require secreted polysaccharides and/or proteins for full nodule development should exist.

It is obvious from the above that rather than being a simple inwardly growing plant cell wall, the infection thread is a composite, symbiotic structure. Some of its' constituents are listed in Table 2. Undoubtedly, many remain to be discovered, but those listed show a tantalizing diversity. It is possible for example, that arabinogalactans and xyloglucans are functional homologues of some rhizobial carbohydrates? What roles do enzymes play? And secreted proteins like NodO? Is it possible that NolJ, NolX, and y4xL have enzymatic activity? (Unfortunately, their amino acid sequences do not suggest a function.) Could any of the molecules listed in Table 2 be part of a signal transduction pathway? Although much research will be needed to answer these questions, it is clear that continued infection thread development (and thus effective, nitrogen-fixing nodules) is dependent on the presence and composition of some of these components. Or, to continue our analogy, rhizobia have a third set of keys that are used to open doors in the infection thread corridor (Fig. 2).

LEGUME LOCKS?

Legume locks could take a number of forms, one of which might resemble receptors such as those involved in transduction of hormonal signals. Whether such symbiotic receptors exist in legumes has not been fully clarified, and the data that exists only concerns lock two (Fig. 2). Two putative Nod-factor binding sites (NFSB) have been characterized in Medicago species (6, 66). Most probably NFSB1 of M. truncatula can be assigned to minor roles because it seems to be involved in processes other than nodulation (70). NFSB2, on the other hand, was isolated from the microsomal fraction of Medicago varia cell suspension cultures and has high affinity for O-acetylated Nod factors (37, 66). Yet NFSB2 discriminates neither for the presence of sulfate on the reducing sugar nor for the number and/or positions of double bonds in the acyl chain. Finally, a lectin has been found on the surface of roots of Dolichos biflorus and other legumes that binds Nod factors and has apyrase activity (26, 87). Unfortunately, it is not clear what roles NFSB1 and NFSB2 as well as the lectin-apyrases play in symbiotic signal exchange.

Mutant screening programs have the advantage of first identifying a phenotype and later the corresponding gene. By inserting the transposon Ac into wild-type Lotus japonicus, Schauser et al. (90) found a mutation in the nin gene which is required for the formation of infection threads and the initiation of nodule primordia. It seems likely that nin encodes a membrane-spanning transcription factor which is related to the mid genes of Chlamydomonas reinhardtii where they regulate sexual reproduction in response to nitrogen starvation. It thus seems as if a combination of classic biochemical analyses combined with molecular-genetic approaches is beginning to identify putative locks to the legume door.

MANY KEYS, MUCH HARMONY?

Symbiotic control is thus exercised at three or more checkpoints—flavonoids↔NodD proteins, Nod factors↔Hac or bacterial entry, as well as EPS and/or proteins↔infection threads (Fig. 2). Courtship begins as rhizobia enter elaborately decorated legume bowers. Liaisons between flavonoids and NodD proteins signal the beginning of the “courtship.” Anything that perturbs this intimacy (e.g., unsuitable flavonoids, mutant NodD proteins) terminates nodule development. Next, NodD-flavonoid complexes activate transcription from various nod box promoters (Fig. 1). Courtship continues as the enzymes encoded by nod genes synthesize a family of Nod factors that serve as keys to legume doors. Then, the couple jointly modifies their house especially to insulate the microsymbiont from the plant cytoplasm and to lower oxygen tensions for nitrogen fixation. Once these challenges have been overcome, both partners live happily exchanging carbohydrates and fixed nitrogen with each other.

Although the above summarizes legume-Rhizobium associations, it does not explain why a particular legume prefers a certain type of Rhizobium, or why some rhizobia like NGR234 can nodulate so many plants (Fig. 4). Most probably the solutions to these puzzles lie in the nature of the locks and keys themselves. Plants excrete a variety of more- or less-enticing flavonoids (key 1 in Fig. 2). Rhizobia possess one to many copies of NodD that may associate with several (or a number of) flavonoids. In turn, flavonoid-NodD complexes (lock 1 in Fig. 2) activate expression of genes downstream of nod boxes (Fig. 1). Enzymes encoded by the nod genes synthesize small to large families of Nod factors (key 2 in Fig. 2), some of which cause Hac or rhizobial entry on (a) specific plant(s) (lock 2). Once they are within the plant, symbiotic components of both partners are necessary for infection thread development (keys and locks 3). Some rhizobia possess the flavonoid-inducible TTSS, suggesting that TTSS (and other) proteins represent additional keys. Other rhizobia excrete various polysaccharides which may function in a similar manner. In summary, simple answers as to why a bacterium like NGR234 can live in harmony with so many plants may include the following. (i) It has a NodD lock that can be opened by many keys (a large variety of flavonoids). (ii) It produces many different keys (the family of >80 Nod factors). (iii) It has alternate keys for the same lock (both EPS and TTSS proteins) (Fig. 2). Rhizobia with narrower host ranges may lack one or more of these locks or keys.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are deeply indebted to Nick Brewin, Ton van Brussel, Jim Cooper, Peter Graham, Peter Müller, Don Phillips, Alf Pühler, Gary Stacey, Christian Staehelin, Wolfgang Streit, and Dietrich Werner for helpful comments on the manuscript. Dora Gerber is thanked for unfailing support of our work.

Financial assistance was provided by the Fonds National de la Recherche Scientifique and the Université de Genève.

REFERENCES

- 1.Arumuganathan K, Earle E D. Nuclear DNA content of some important plant species. Plant Mol Biol Rep. 1991;9:208–218. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bassam B J, Djordjevic M A, Redmond J W, Batley M, Rolfe B G. Identification of a nodD-dependent locus in the Rhizobium strain NGR234 activated by phenolic factors secreted by soybeans and other legumes. Mol Plant-Microbe Interact. 1988;1:161–168. doi: 10.1094/mpmi-1-161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bazin M J, Markham P, Scott E M, Lynch J M. Population dynamics and rhizosphere interactions. In: Lynch J M, editor. The rhizosphere. Chichester, United Kingdom: John Wiley & Sons; 1990. pp. 99–127. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bender G L, Nayudu M, Strange K K L, Rolfe B G. The nodD1 gene from Rhizobium strain NGR234 is a key determinant in the extension of host range to the nonlegume Parasponia. Mol Plant-Microbe Interact. 1988;1:259–266. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bolanos-Vásquez M C, Werner D. Effects of Rhizobium tropici, R. etli, and R. leguminosarum bv phaseoli on nod gene-inducing flavonoids in root extracts of Phaseolus vulgaris. Mol Plant-Microbe Interact. 1997;10:339–346. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bono J J, Riond J, Nicolaou K C, Bockovich N J, Estevez V A, Cullimore J V, Ranjeva R. Characterization of a binding site for chemically synthesized lipo-oligosaccharidic NodRm factors in particulate fractions prepared from roots. Plant J. 1995;7:253–260. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1995.7020253.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Breedveld M W, Cremers H C, Batley M, Posthumus M A, Zevenhuizen L P, Wijffelman C A, Zehnder A J. Polysaccharide synthesis in relation to nodulation behavior of Rhizobium leguminosarum. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:750–757. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.3.750-757.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brewin N J. Tissue and cell invasion by Rhizobium: the structure and development of infection threads and symbiosomes. In: Spaink H P, Kondorosi A, Hooykaas P J J, editors. The Rhizobiaceae. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 1998. pp. 417–429. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brewin N J, Rae A L, Perotto S, Kannenberg E L, Rathbun E A, Lucas M M, Gunder A, Bolanos L, Kardailsky I V, Wilson K E, Firmin J L, Downie J A. Bacterial and plant glycoconjugates at the Rhizobium-legume interface. Biochem Soc Symp. 1994;60:61–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Broughton W J. Control of specificity in legume-Rhizobium associations. J Appl Bacteriol. 1978;45:165–194. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Broughton W J, Chan P Y, Padmanabhan S, Tan I K P. Rhizobia in tropical legumes. I. Preliminary studies of antibiotic sensitivity, pH and temperature optima. Malaysian Agric Res. 1975;4:141–153. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Broughton W J, Perret X. Genealogy of legume-Rhizobium symbioses. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 1999;2:305–311. doi: 10.1016/S1369-5266(99)80054-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cheng H P, Walker G C. Succinoglycan is required for initiation and elongation of infection threads during nodulation of alfalfa by Rhizobium meliloti. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:5183–5191. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.19.5183-5191.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cook D R, VandenBosch K, de Bruijn F J, Huguet T. Model legumes get the nod. Plant Cell. 1997;9:275–281. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cooper J E, Rao J R, De Cooman L, McCorry T M, Bjourson A J, Steele H L, Broughton W J, Werner D. Biochemical and molecular analyses of rhizobial responses to legume flavonoids. In: Legocki A B, Bothe H, Pühler A, editors. Biological fixation of nitrogen for ecology and sustainable agriculture. Berlin, Germany: Springer; 1997. pp. 115–118. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dart P. Infection and development of leguminous nodules. In: Hardy R W F, Silver W S, editors. A treatise on dinitrogen fixation. London, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press; 1977. pp. 367–472. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dart P J. Scanning electron microscopy of plant roots. J Exp Bot. 1971;22:163–168. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dazzo F B, Truchet G L, Hollingsworth R I, Hrabak E M, Pankratz H S, Philip-Hollingsworth S, Salzwedel J L, Chapman K, Appenzeller L, Squartini A. Rhizobium lipopolysaccharide modulates infection thread development in white clover root hairs. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:5371–5384. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.17.5371-5384.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.D'Haeze W, Gao M, De Rycke R, van Montagu M, Engler G, Holsters M. Roles for azorhizobial Nod factors and surface polysaccharides in intercellular invasion and nodule penetration, respectively. Mol Plant-Microbe Interact. 1998;11:999–1008. [Google Scholar]

- 20.D'Haeze W, Mergaert P, Promé J-C, Holsters M. Nod factor requirements for efficient stem and root nodulation of the tropical legume Sesbania rostrata. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:15676–15684. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.21.15676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dickstein R, Scheirer D C, Fowle W H, Ausubel F M. Nodules elicited by Rhizobium meliloti heme mutants are arrested at an early stage of development. Mol Gen Genet. 1991;230:423–432. doi: 10.1007/BF00280299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Djordjevic S P, Rolfe B G. The structure of the exopolysaccharide from Rhizobium sp. strain ANU280 (NGR234) Carbohydr Res. 1986;148:87–99. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Downie J A. Functions of rhizobial nodulation genes. In: Spaink H P, Kondorosi A, Hooykaas P J J, editors. The Rhizobiaceae. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 1998. pp. 387–402. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Duke J A. Handbook of legumes of world economic importance. 1st ed. New York, N.Y: Plenum Press; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dunlap J, Minami E, Bhagwat A A, Keister D L, Stacey G. Nodule development induced by mutants of Bradyrhizobium japonicum defective in cyclic β-glucan synthesis. Mol Plant-Microbe Interact. 1996;9:546–555. doi: 10.1094/mpmi-9-0546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Etzler M E, Kalsi G, Ewing N N, Roberts N J, Day R B, Murphy J B. A nod factor binding protein with apyrase activity from legume roots. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:5856–5861. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.10.5856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Faizah A W, Padmanabhan S, Broughton W J, John C K. Rhizobia in tropical legumes. V. Problems involved in selecting inoculants for soyabeans. In: Broughton W J, John C K, Rajarao J C, Lim B, editors. Soil microbiology and plant nutrition. Kuala Lumpur, Malayasia: University of Malaya Press; 1979. pp. 392–409. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fedorova E, Thomson R, Whitehead L F, Maudoux O, Udvardi M K, Day D A. Localization of H+-ATPase in soybean root nodules. Planta. 1999;209:25–32. doi: 10.1007/s004250050603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fellay R, Hanin M, Montorzi G, Frey J, Freiberg C, Golinowski W, Staehelin C, Broughton W J, Jabbouri S. nodD2 of Rhizobium sp. NGR234 is involved in the repression of the nodABC operon. Mol Microbiol. 1998;27:1039–1050. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00761.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fellay R, Rochepeau P, Relić B, Broughton W J. Signals to and emanating from Rhizobium largely control symbiotic specificity. In: Singh U S, Singh R P, Kohmoto K, editors. Pathogenesis & host specificity in plant diseases: histopathological, biochemical, genetic and molecular bases. 1. Prokaryotes. Oxford, United Kingdom: Pergamon/Elsevier Science Ltd.; 1995. pp. 199–220. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Firmin J L, Wilson K E, Rossen L, Johnston A W B. Flavonoid activation of nodulation genes in Rhizobium reversed by other compounds present in plants. Nature. 1986;324:90–92. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Francisco P B, Akao S. Autoregulation and nitrate inhibition of nodule formation in soybean cv. enrei and its nodulation mutants. J Exp Bot. 1993;44:547–553. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Freiberg C, Fellay R, Bairoch A, Broughton W J, Rosenthal A, Perret X. Molecular basis of symbiosis between Rhizobium and legumes. Nature. 1997;387:394–401. doi: 10.1038/387394a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gardner C D, Sherrier D J, Kardailsky I V, Brewin N J. Localization of lipoxygenase proteins and mRNA in pea nodules: identification of lipoxygenase in the lumen of infection threads. Mol Plant-Microbe Interact. 1996;9:282–289. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Göttfert M, Grob P, Hennecke H. Proposed regulatory pathway encoded by the nodV and nodW genes, determinants of host specificity in Bradyrhizobium japonicum. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:2680–2684. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.7.2680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Graham P H. The application of computer techniques to the taxonomy of the root-nodule bacteria of legumes. J Gen Microbiol. 1964;35:511–517. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gressent F, Drouillard S, Mantegazza N, Samain E, Geremia R A, Canut H, Niebel A, Driguez H, Ranjeva R, Cullimore J, Bono J J. Ligand specificity of a high-affinity binding site for lipo-chitooligosaccharidic nod factors in Medicago cell suspension cultures. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:4704–4709. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.8.4704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hanin M, Jabbouri S, Broughton W J, Fellay R. SyrM1 of Rhizobium sp. NGR234 activates transcription of symbiotic loci and controls the level of sulfated Nod factors. Mol Plant-Microbe Interact. 1998;11:343–350. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hanin M, Jabbouri S, Broughton W J, Fellay R, Quesada-Vincens D. Molecular aspects of host-specific nodulation. In: Stacey G, Keen N, editors. Plant-microbe interactions. Vol. 4. St. Paul, Minn: American Phytopathological Society; 1999. pp. 1–37. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hartwig H A, Phillips D A. Release and modification of nod-gene-inducing flavonoids from alfalfa seeds. Plant Physiol. 1991;95:804–807. doi: 10.1104/pp.95.3.804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hartwig U A, Maxwell C A, Joseph C M, Phillips D A. Effects of alfalfa nod gene-inducing flavonoids on nodABC transcription in Rhizobium meliloti strains containing different nodD genes. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:2769–2773. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.5.2769-2773.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Higashi S, Kushiyama K, Abe M, Reyes G D, Manguiat I J. Electron-microscopic studies of the root nodule of Pterocarpus indicus. J Gen Appl Microbiol. 1987;33:241–245. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hiltner L, Störmer K. Neue Untersuchungen über die Wurzelknöllchen der Leguminosen und deren Erreger. Arb Biol Abteil Land- Forstwirth Kaiser Gesund. 1903;3:151–307. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hungria M, Joseph C M, Phillips D A. Rhizobium nod gene inducers exuded naturally from roots of common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L) Plant Physiol. 1991;97:759–764. doi: 10.1104/pp.97.2.759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ikram A, Broughton W J. The winged bean. Los Banos, Laguna, The Philippines: Philippine Council for Agricultural Research; 1978. Rhizobia in tropical legumes. XII. Inoculation of Psophocarpus tetragonolobus (L.) DC; pp. 205–210. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ikram A, Broughton W J. Rhizobia in tropical legumes. VII. Effectiveness of different isolates on Psophocarpus tetragonolobus (L.) DC. Soil Biol Biochem. 1980;12:77–82. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ikram A, Padmanabhan S, John C K, Broughton W J. Rhizobia in tropical legumes. VI. Glasshouse and field trials with rhizobia for Centrosema pubescens Benth. J Sains. 1978;2:33–42. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Irving H R, Boukli N M, Kelly M N, Broughton W J. Nod-factors in symbiotic development of root hairs. In: Ridge R W, Emons A M C, editors. Root hairs: cell and molecular biology. Tokyo, Japan: Springer; 2000. pp. 241–265. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kape R, Parniske M, Brandt S, Werner D. Isoliquiritigenin, a strong nod gene- and glyceollin resistance-inducing flavonoid from soybean root exudate. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1992;58:1705–1710. doi: 10.1128/aem.58.5.1705-1710.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Krause A, Sigrist C J, Dehning I, Sommer H, Broughton W J. Accumulation of transcripts encoding a lipid transfer-like protein during deformation of nodulation-competent Vigna unguiculata root hairs. Mol Plant-Microbe Interact. 1994;7:411–418. doi: 10.1094/mpmi-7-0411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Krishnan H B, Pueppke S. Cloned cellulase gene from Erwinia carotovora subsp. carotovora is expressed in Rhizobium fredii but does not influence nodulation of cowpea. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1994;119:289–294. [Google Scholar]

- 52.LeVier K, Phillips R W, Grippe V K, Roop R M, Walker G C. Similar requirements of a plant symbiont and a mammalian pathogen for prolonged intracellular survival. Science. 2000;287:2492–2493. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5462.2492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lewin A, Rosenberg C, Meyer z.A. H, Wong C-H, Nelson L, Manen J-F, Stanley J, Dowling D N, Dénarié J, Broughton W J. Multiple host-specificity loci of the broad host range Rhizobium sp. NGR 234 selected using the widely compatible legume Vigna unguiculata. Plant Mol Biol. 1987;8:447–459. doi: 10.1007/BF00017990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Loh J, Garcia M, Stacey G. NodV and NodW, a second flavonoid regulation system regulating nod gene expression in Bradyrhizobium japonicum. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:3013–3020. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.9.3013-3020.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Loh J, Stacey M G, Sadowsky M J, Stacey G. The Bradyrhizobium japonicum nolA gene encodes three functionally distinct proteins. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:1544–1554. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.5.1544-1554.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Margulis L. Symbiosis in cell evolution. Microbial communities in the archean and proterozoic eons. 2nd ed. New York, N.Y: W. H. Freeman and Co.; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Maxwell C A, Hartwig U A, Joseph C M, Phillips D A. A chalcone and two related flavonoids released from alfalfa roots induce nod genes of Rhizobium meliloti. Plant Physiol. 1989;91:842–847. doi: 10.1104/pp.91.3.842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Maxwell C A, Phillips D A. Concurrent synthesis and release of nod-gene-inducing flavonoids from alfalfa roots. Plant Physiol. 1990;93:1552–1558. doi: 10.1104/pp.93.4.1552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.McCray-Batzli J, Graves W R, van Berkum P. Diversity among rhizobia effective with Robinia pseudoacacia. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1992;58:2137–2143. doi: 10.1128/aem.58.7.2137-2143.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Messens E, Geelen D, van Montagu M, Holsters M. 7,4-Dihydroxyflavanone is the major Azorhizobium nod gene-inducing factor present in Sesbania rostrata seedling exudate. Mol Plant-Microbe Interact. 1991;4:262–267. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Michiels J, Dombrecht B, Vermeiren N, Xi C-W, Luyten E, Vanderleyden J. Phaseolus vulgaris is a non-selective host for nodulation. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 1998;26:193–205. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Minami E, Kouchi H, Cohn J R, Ogawa T, Stacey G. Expression of the early nodulin, ENOD40, in response to various lipo-chitin signal molecules. Plant J. 1996;10:23–32. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1996.10010023.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Moffett M L, Colwell R R. Adansonian analysis of the Rhizobiaceae. J Gen Microbiol. 1968;51:245–266. doi: 10.1099/00221287-51-2-245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Müller P, Ahrens K, Keller T, Klaucke A. A Tn-phoA insertion within the Bradyrhizobium japonicum sipS gene, homologous to prokaryotic signal peptidases, results in extensive changes in the expression of PBM-specific nodulins of infected soybean (Glycine max) cells. Mol Microbiol. 1995;18:831–840. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.18050831.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Newman J D, Diebold R J, Schultz B W, Noel K D. Infection of soybean and pea nodules by Rhizobium spp. purine auxotrophs in the presence of 5-aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide riboside. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:3286–3294. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.11.3286-3294.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Niebel A, Bono J J, Ranjeva R, Cullimore J V. Identification of a high affinity binding site for lipo-oligosaccharidic NodRm factors in the microsomal fraction of Medicago cell suspension cultures. Mol Plant-Microbe Interact. 1997;10:132–134. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Niehaus K, Kapp D, Pühler A. Plant defense and delayed infection of alfalfa pseudonodules induced by an exopolysaccharide (EPS-I)-deficient Rhizobium meliloti mutant. Planta. 1993;190:415–425. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Perret X, Freiberg C, Rosenthal A, Broughton W J, Fellay R. High-resolution transcriptional analysis of the symbiotic plasmid of Rhizobium sp. NGR234. Mol Microbiol. 1999;32:415–425. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01361.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Pellock B J, Cheng H-P, Walker G C. Alfalfa root nodule invasion efficiency is dependent on Sinorhizobium meliloti polysaccharides. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:4310–4318. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.15.4310-4318.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Perret X, Staehelin C, Broughton W J. Molecular basis of symbiotic promiscuity. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2000;64:180–201. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.64.1.180-201.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Perret X, Viprey V, Broughton W J. Physical and genetic analysis of the broad host-range Rhizobium sp. NGR234. In: Triplett E W, editor. Prokaryotic nitrogen fixation. Wymondham, United Kingdom: Horizon Scientific Press; 2000. pp. 679–692. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Peters N K, Frost J W, Long S R. A plant flavone, luteolin, induces expression of Rhizobium meliloti nodulation genes. Science. 1986;233:977–980. doi: 10.1126/science.3738520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Phillips D A, Streit W. Legume signals to rhizobial symbionts: a new approach for defining rhizosphere colonization. In: Stacey G, Keen N, editors. Plant-microbe interactions. I. Plant-microbe relationships. New York, N.Y: Chapman and Hall; 1996. pp. 236–271. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Phillips D A, Streit W R. Applying plant-microbe signalling concepts to alfalfa: roles for secondary metabolites. In: McKersie B D, Brown D C W, editors. Biotechnology and the improvements of forage legumes. Wallingford, United Kingdom: CAB International; 1997. pp. 319–342. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Price N P, Relić B, Talmont F, Lewin A, Promé D, Pueppke S G, Maillet F, Dénarié J, Promé J-C, Broughton W J. Broad-host-range Rhizobium species strain NGR234 secretes a family of carbamoylated, and fucosylated, nodulation signals that are O-acetylated or sulphated. Mol Microbiol. 1992;6:3575–3584. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1992.tb01793.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Pueppke S G, Bolanos-Vásquez M C, Werner D, Bec-Ferté M-P, Promé J-C, Krishnan H B. Release of flavonoids by the soybean cultivars McCall and Peking and their perception as signals by the nitrogen-fixing symbiont Sinorhizobium fredii. Plant Physiol. 1998;117:599–608. doi: 10.1104/pp.117.2.599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Pueppke S G, Broughton W J. Rhizobium sp. strain NGR234 and R. fredii USDA257 share exceptionally broad, nested host ranges. Mol Plant-Microbe Interact. 1999;12:293–318. doi: 10.1094/MPMI.1999.12.4.293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Rae A L, Bonfantefasolo P, Brewin N J. Structure and growth of infection threads in the legume symbiosis with Rhizobium leguminosarum. Plant J. 1992;2:385–395. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Rao J R, Cooper J E. Rhizobia catabolize nod gene-inducing flavonoids via C-ring fission mechanisms. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:5409–5413. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.17.5409-5413.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Rao J R, Cooper J E. Soybean nodulating rhizobia modify nod gene inducers daidzein and genistein to yield aromatic products that can influence gene inducing activity. Mol Plant-Microbe Interact. 1995;8:855–862. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Recourt K, Schripsema J, Kijne J W, van Brussel A A N, Lugtenberg B J J. Inoculation of Vicia sativa subsp. nigra roots with Rhizobium leguminosarum biovar viciae results in release of nod gene activating flavonones and chalcones. Plant Mol Biol. 1991;16:841–852. doi: 10.1007/BF00015076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Recourt K, Verkerke M, Schripsema J, van Brussel A A N, Lugtenberg B J J, Kijne J W. Major flavonoids in uninoculated and inoculated roots of Viciae sativa subsp. nigra are four conjugates of the nodulation gene inhibitor kaempferol. Plant Mol Biol. 1992;18:505–513. doi: 10.1007/BF00040666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Redmond J W, Batley M, Djordjevic M A, Innes R W, Kuempel P L, Rolfe B G. Flavones induce expression of nodulation genes in Rhizobium. Nature. 1986;323:632–635. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Relić B, Fellay R, Lewin A, Perret X, Price N P J, Rochepeau P, Broughton W J. nod genes and Nod factors of Rhizobium species NGR234. In: Palacios R, Mora J, Newton W E, editors. New horizons in nitrogen fixation. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 1993. pp. 183–189. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Relić B, Perret X, Estrada-Garcia M T, Kopcinska J, Golinowski W, Krishnan H B, Pueppke S G, Broughton W J. Nod factors of Rhizobium are a key to the legume door. Mol Microbiol. 1994;13:171–178. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb00412.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Relić B, Talmont F, Kopcinska J, Golinowski W, Promé J-C, Broughton W J. Biological activity of Rhizobium sp. NGR234 Nod-factors on Macroptilium atropurpureum. Mol Plant-Microbe Interact. 1993;6:764–774. doi: 10.1094/mpmi-6-764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Roberts N J, Brigham J, Wu B, Murphy J B, Volpin H, Phillips D A, Etzler M E. A Nod factor-binding lectin is a member of a distinct class of apyrases that may be unique to the legumes. Mol Gen Genet. 1999;262:261–267. doi: 10.1007/s004380051082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Rolfe B G, Carlson R W, Ridge R W, Dazzo F B, Mateos P F, Pankhurst C E. Defective infection and nodulation of clovers by exopolysaccharide mutants of Rhizobium leguminosarum bv. trifolii. Aust J Plant Physiol. 1996;23:285–303. [Google Scholar]

- 89.Schäfers B, Werner D. Nodulation of Robinia pseudoacacia by two Rhizobium strains. Nitr Fix Tree Res Rep. 1993;11:121–126. [Google Scholar]

- 90.Schauser L, Roussis A, Stiller J, Stougaard J. A plant regulator controlling development of symbiotic root nodules. Nature. 1999;402:191–195. doi: 10.1038/46058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Scheidemann P, Wetzel A. Identification and characterization of flavonoids in the root exudate of Robinia pseudoacacia. Trees. 1997;11:316–321. [Google Scholar]

- 92.Scheres B, van Engelen F, van der Knaap E, van de Wiel C, van Kammen A, Bisseling T. Sequential induction of nodulin gene expression in the developing pea nodule. Plant Cell. 1990;2:687–700. doi: 10.1105/tpc.2.8.687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Schlaman H R M, Okker R J H, Lugtenberg B J J. Regulation of nodulation gene expression by NodD in rhizobia. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:5177–5182. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.16.5177-5182.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Schmidt P E, Broughton W J, Werner D. Nod factors of Bradyrhizobium japonicum and Rhizobium sp. NGR234 induce flavonoid accumulation in soybean root exudate. Mol Plant-Microbe Interact. 1994;7:384–390. [Google Scholar]

- 95.Sherrier D J, VandenBosch K A. Localization of repetitive proline-rich proteins in the extracellular matrix of pea nodules. Protoplasma. 1994;183:148–161. [Google Scholar]

- 96.Skorupska A, Bialek U, Urbaniksypniewska T, van Lammeren A. Two types of nodules induced on Trifolium pratense by mutants of Rhizobium leguminosarum bv. trifolii deficient in exopolysaccharide production. J Plant Physiol. 1995;147:93–100. [Google Scholar]

- 97.Smit G, Puvanesarajah V, Carlson R W, Barbour W M, Stacey G. Bradyrhizobium japonicum nodD1 can be specifically induced by soybean flavonoids that do not induce the nodYABCSUIJ operon. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:310–318. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Stachel S E, An G, Flores C, Nester E W. A Tn3 lacZ transposon for the random generation of β-galactosidase gene fusions: application to the analysis of gene expression in Agrobacterium. EMBO J. 1985;4:891–898. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1985.tb03715.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Stachel S E, Messens E, van Montagu M, Zambryski P. Identification of the signal molecules produced by wounded plant cells that activate T-DNA transfer in Agrobacterium tumefaciens. Nature. 1985;318:624–629. [Google Scholar]

- 100.Stafford H A. Roles of flavonoids in symbiotic and defense reactions in legume roots. Bot Rev. 1997;63:27–39. [Google Scholar]

- 101.Trinick M J. Relationships amongst the fast-growing rhizobia of Lablab purpureus, Leucaena leucocephala, Mimosa spp., Acacia farnesiana and Sesbania grandiflora and their affinities with other rhizobial groups. J Appl Bacteriol. 1980;49:39–53. [Google Scholar]

- 102.Tsyganov V E, Morzhina E V, Stefanov S Y, Borisov A Y, Lebsky V K, Tikhonovich I A. The pea (Pisum sativum L.) genes sym33 and sym40 control infection thread formation and root nodule function. Mol Gen Genet. 1998;259:491–503. doi: 10.1007/s004380050840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Udvardit M K, Day D A. Metabolite transport across symbiotic membranes of legume nodules. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol. 1997;48:493–523. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.48.1.493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Utrup L J, Cary A J, Norris J H. Five nodulation mutants of white sweetclover (Melilotus-alba Desr) exhibit distinct phenotypes blocked at root hair curling, infection thread development, and nodule organogenesis. Plant Physiol. 1993;103:925–932. doi: 10.1104/pp.103.3.925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.van Brussel A A N, Bakhuizen R, van Spronsen P C, Spaink H P, Tak T, Lugtenberg B J J, Kijne J W. Induction of preinfection thread structures in the leguminous host plant by mitogenic lipo-oligosaccharides of Rhizobium. Science. 1992;257:70–72. doi: 10.1126/science.257.5066.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.VandenBosch K A, Desmond J B, Knox J P, Perotto S, Butcher G W, Brewin N J. Common components of the infection thread matrix and the intercellular space identified by immunocytochemical analysis of pea nodules and uninfected roots. EMBO J. 1989;8:335–342. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1989.tb03382.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.van Workum W A T, van Slageren S, van Brussel A A N, Kijne J W. Role of exopolysaccharides of Rhizobium leguminosarum bv. viciae as host plant-specific molecules required for infection thread formation during nodulation of Vicia sativa. Mol Plant-Microbe Interact. 1998;11:1233–1241. [Google Scholar]

- 108.Vasse J, de Billy F, Truchet G. Abortion of infection during the Rhizobium meliloti symbiotic interaction is accompanied by a hypersensitive reaction. Plant J. 1993;4:555–566. [Google Scholar]

- 109.Viprey V, Del Greco A, Golinowski W, Broughton W J, Perret X. Symbiotic implications of type III protein secretion machinery in Rhizobium. Mol Microbiol. 1998;28:1381–1389. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00920.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Werner D. Organic signals between plants and microorganisms. In: Pinton R, Varanini Z, Nannipieri P, editors. The rhizosphere: biochemistry and organic substances at the soil-plant interface. New York, N.Y: Marcel Dekker Inc.; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 111.Werner D. Symbiosis of plants and microbes. 1st ed. London, United Kingdom: Chapman & Hall; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 112.Whipps J M. Carbon economy. In: Lynch J M, editor. The rhizosphere. Chichester, United Kingdom: John Wiley & Sons; 1990. pp. 59–97. [Google Scholar]

- 113.Whitehead L F, Day D A. The peribacteroid membrane. Physiol Plant. 1997;100:30–44. [Google Scholar]

- 114.Wilson J K. Leguminous plants and their associated organisms. Cornell University Agricultural Experimental Station memoir 221. Ithaca, N.Y: Cornell University Press; 1939. [Google Scholar]

- 115.Wong C H, Patchamathu R, Meyer z. A. H, Pankhurst C E, Broughton W J. Rhizobia in tropical legumes: ineffective nodulation of Arachis hypogaea L. by fast-growing strains. Soil Biol Biochem. 1988;20:677–681. [Google Scholar]

- 116.Wu C F, Dickstein R, Cary A J, Norris J H. The auxin transport inhibitor N-(1-naphthyl)phtalamic acid elicits pseudonodules on nonnodulating mutants of white sweetclover. Plant Physiol. 1996;110:502–510. doi: 10.1104/pp.110.2.501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Zuanazzi J A S, Clergeot P H, Quirion J-C, Husson H-P, Kondorosi A, Ratet P. Production of Sinorhizobium meliloti nod gene activator and repressor flavonoids from Medicago sativa roots. Mol Plant-Microbe Interact. 1998;11:784–794. [Google Scholar]