Abstract

Objectives:

Topical fluoride helps prevent dental caries. However, many caregivers are hesitant about topical fluoride for their children and may refuse it during clinic visits. In this qualitative study, we assessed the relevance of the extended parallel process model (EPPM) and health belief model (HBM) in caregivers’ decision-making about topical fluoride.

Methods:

We interviewed 56 fluoride-hesitant or fluoride-refusing caregivers using a semi-structured interview script that included questions based on select constructs from the EPPM (perceived severity, susceptibility, response efficacy) and HBM (perceived benefits and consequences). Two team members conducted a thematic analysis of the interview data.

Results:

Most caregivers acknowledged the severity of cavities but did not believe their child was susceptible. Caregivers also understood the general benefits of fluoride in preventing tooth decay, but reported low response efficacy of fluoride for their children especially compared to the other ways of reducing caries risk like reducing sugar intake and toothbrushing. Many caregivers had concerns about topical fluoride, especially regarding safety, with the potential consequences of fluoride outweighing its benefits.

Conclusion:

Our findings were generally consistent with the EPPM and HBM, which appear to be relevant in understanding fluoride hesitancy behaviors. Additional research is needed on ways to improve provider communications about topical fluoride with caregivers.

Keywords: decision making, dental caries, pediatric dentistry, preventive dentistry, qualitative research, topical fluorides, treatment refusal

INTRODUCTION

Topical fluoride is one of the few evidence-based therapies known to prevent dental caries. The American Dental Association (ADA) recommends that all children at risk for caries receive topical fluoride every 3–6 months [1]. A 2012 systematic review reported that children who received topical fluoride at least once a year had a 43% reduction in decayed permanent teeth compared to children in the placebo and control groups [2]. For children with primary teeth, there was a 37% reduction in decayed, missing, and filled teeth [2].

Caregivers present with a range of fluoride-related decision making during dental visits from absolute acceptance to absolute refusal of topical fluoride with varying degrees of hesitancy in between [3]. One study reported that 12.7% of caregivers refused topical fluoride for their children during a dental visit [4]. Another study documented dentists’ perceptions about the growing number of caregivers who are hesitant about topical fluoride [5]. Concerns about necessity and safety are two reasons why some caregivers are hesitant [3].

There is a dearth of studies on the behavioral determinants of topical fluoride refusal behaviors, which is a barrier to understanding how caregivers make fluoride-related decisions for their children. Health behavior models can be used to understand behaviors and to eventually develop behavioral interventions to improve patient-provider communications about preventive care. Two potentially relevant models in understanding fluoride refusal behaviors are the extended parallel process model (EPPM) and the health belief model (HBM) [6,7].

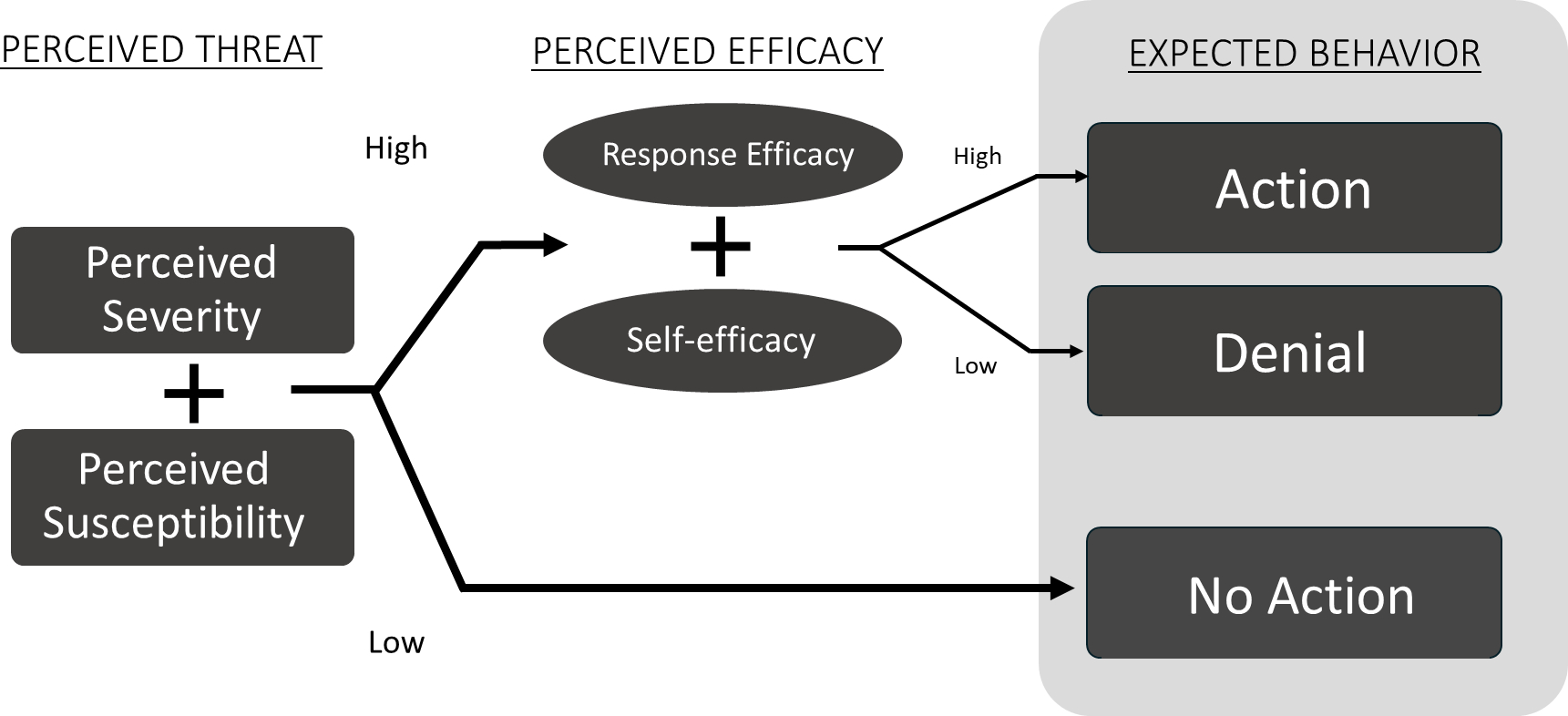

The EPPM posits that threat (e.g., perceived severity of caries and perceived susceptibility to caries) and efficacy (e.g., response efficacy of topical fluoride treatment and self-efficacy) are upstream determinants of health behaviors [6]. There are three possible scenarios (Figure 1). When an individual faces a health threat (e.g., dental caries), the threat can be assessed as low or high based on perceptions of severity and susceptibility. If the threat is perceived as low, there is no effort to evaluate efficacy, and therefore no action. A high threat prompts an individual to evaluate efficacy, which is a combination of the potential effectiveness of a response (response efficacy) and the ability to respond (self-efficacy). If the perceived threat is high but efficacy is low, the individual will respond to the threat, but with counterproductive behaviors, such as denial. If perceived threat and efficacy are both high, the individual is likely to take positive actions to address the threat [8]. Thus, in the EPPM, a combination of high threat and high efficacy is hypothesized to prompt a productive behavioral response. The EPPM has been used to study preventive dental care use for children in Medicaid and provides a way to evaluate caregivers’ responses to topical fluoride for their children based on threat and efficacy [8].

FIGURE 1.

Constructs from the extended parallel process model with role of threat and efficacy in predicting behavior change

The HBM is a framework that adds to the EPPM by incorporating an individual’s evaluation of the perceived benefits and barriers associated with completing a behavior [7]. The construct of perceived benefits includes not only an assessment of whether the behavior is effective, but also if there are other benefits to doing the behavior. Perceived barriers include the challenges an individual may face when trying to complete the behavior. The HBM has been used in research on preventive dental visits, dietary changes, and behaviors relevant in mental health [7,9–10].

In this qualitative study, we investigated constructs from the EPPM and HBM to better understand topical fluoride decision-making behaviors of caregivers. The study is expected to clarify how fluoride-hesitant caregivers make decisions about topical fluoride and is relevant in developing future theory-driven behavioral strategies aimed at improving patient-provider communications with fluoride-hesitant caregivers.

METHODS

Study design and participants

Recruitment for this qualitative study included two sites: a university-based pediatric dental clinic and a community-based children’s dental clinic. We focused on caregivers who were hesitant about topical fluoride for their children and identified potential participants through a three-step process. First, we examined billing records to identify children who did not receive topical fluoride during a routine dental visit. Next, we reviewed health records to confirm any dental visits in which topical fluoride refusal was noted. Lastly, we called caregivers of children to confirm caregiver refusal or hesitancy of topical fluoride. Additional caregivers were identified via social media, private clinics, and personal networks of the study team. We used snowball sampling techniques in which participating caregivers were asked to recommend individuals who might be recruited for the study. Exclusion criteria included caregivers who did not speak English, were under 18 years of age, or declined topical fluoride for solely financial reasons. The University of Washington IRB approved the study.

Study procedures

After obtaining verbal informed consent, one of three trained interviewers conducted a single interview by telephone with each study participant using a semi-structured interview script, which included 16 open- and nine close-ended questions (Appendix A). The script was developed based on previous literature, piloted with three parents, revised to improve clarity and flow, and finalized [3,4,11,12]. To assess a participant’s degree of topical fluoride hesitancy, caregivers were asked how much they were opposed to topical fluoride (range: 1–10). To assess caregivers’ confidence that topical fluoride could prevent caries, caregivers were asked “On a scale of 1 to 10, with “1” being not at all confident and “10” being totally confident, how confident are you that topical fluoride can prevent your child from getting a cavity?” Interviewers asked participants about their attitudes, beliefs, and knowledge about topical fluoride, as well as beliefs about their child’s oral health, and demographic information. Interviews lasted between 20 and 90 min. Caregivers received a $30 gift card for participating.

Data management and analyses

Interviews were audio-recorded, then transcribed and verified for accuracy by five trained research assistants. A thematic analysis of the transcripts was conducted using a deductive coding approach [13]. Deductive coding is based on a set of pre-identified codes [12]. An initial codebook was generated based on constructs from the EPPM (perceived severity, susceptibility, and response efficacy) and the HBM (perceived benefits and consequences) [6,7]. The self-efficacy construct from the EPPM was omitted because all participants had children who were offered topical fluoride when indicated. Because of overlap between response efficacy and perceived benefits, we collapsed these two constructs into one code. The final codes were: perceived severity of caries (how bad it would be for their child to get a cavity), perceived caries susceptibility (how likely their child is to develop a cavity), response efficacy and perceived benefits of topical fluoride (how effective topical fluoride is at preventing cavities in their child), and perceived consequences of topical fluoride (potential negative outcomes of using topical fluoride). Two trained individuals (DK and EL) coded 10 of the 56 transcripts to establish intercoder agreement [12]. The primary coder (EL) coded the remaining transcripts individually, while the peer debriefer (DK) reviewed all coding to ensure the fit of the coded data within each code.

RESULTS

Participant demographics

Of the 119 caregivers screened by phone, 72 were eligible and 56 were interviewed. Participant ages ranged from 29 to 79 years with a mean of 41.9 years (SD = 9.7). Most were women (91.1%,), white (56.7%), non-Hispanic (87.5%), and had at least a 4-year college degree (62.5%). Participants reported between one and four children 18 years old or younger with a mean of 1.8 children (SD = 0.9). The mean age of children was 8.0 years (SD = 0.9). Of the participants with school-aged children (n = 47), 29.3% reported having at least one child who received or was eligible for free or reduced cost school meals.

Topical fluoride beliefs

On a scale of 1 (not at all opposed) to 10 (totally opposed), the mean score was 7.1 (SD = 2.3, range: 3–10). About 37.5% reported saying absolutely no to topical fluoride for their child, 35.7% reported saying no most of the time, 17.9% reported saying no sometimes, and 8.9% reported saying yes to topical fluoride but thought about saying no.

Perceived severity of caries

Only one caregiver described cavities during childhood as “normal,” and therefore not a significant health issue. The perceived ubiquity of cavities led this caregiver to believe that topical fluoride was unnecessary. Over half of the remaining caregivers interviewed believed cavities to be a serious disease. This acknowledgment prompted some fluoride-hesitant caregivers to allow topical fluoride. For one caregiver, getting cavities was described as “the tipping point. That’s the line for me…If there’s anything I can do to prevent cavities for him [my son], I would do it.” Another caregiver explained “It wasn’t until he [my son] was four and…all of the sudden he had all these cavities, and one was really bad…I was like, ‘oh, snap!’ And I started making him [the dentist] put it [topical fluoride] on.”

Several caregivers, especially caregivers of children with special health care needs, were concerned about cavities because of the anticipated difficulties their child might have with restorative treatment, if a cavity required treatment, or because they were afraid their child would require sedation for treatment. This led some hesitant caregivers to opt for topical fluoride. As one caregiver explained, “I would do it [topical fluoride] because if he [my son] gets a cavity that’s severe enough, he would need to be sedated in order to fill that [cavity].”

Perceived susceptibility to caries

Most caregivers believed their child was unlikely or extremely unlikely to get a cavity. These caregivers believed their child had good oral health and dietary habits that prevented them from getting cavities. Some caregivers reported their child had never had a cavity and others talked about getting fluoride from other sources like water and toothpaste. Conversely, less than half of caregivers believed their child was likely or extremely likely to get cavities. Caregivers believed susceptibility to cavities was based on non-modifiable or modifiable factors.

Non-modifiable factors

Some caregivers attributed their child’s susceptibility to cavities to factors beyond their control, such as a family history of oral health problems, their child having a special health care need, or physical characteristics of their child’s teeth. One caregiver stated that “he’s [my son] just born into horrible teeth. His father and I both have really bad teeth.” Some caregivers believed underlying health conditions made their child more susceptible. One caregiver said, “She [my daughter] also has a chronic illness and I feel like it’s weakened her teeth.” Aside from having special needs, others believed their child was at higher risk of cavities because of tooth characteristics like “increased porosity” or a “lack of enamel strength.”

Modifiable factors

Caregivers believed factors such as poor dietary habits and oral hygiene also made their child more susceptible to cavities. One caregiver said, “he [my son] doesn’t have as great of a diet as she [my daughter] does…he eats a lot more junk and he doesn’t eat the things that have nutrients in them like she does.” A caregiver of a 13-year-old said “he [my son] doesn’t brush as much as he should…he has 2 spots [cavities] right now.” Some caregivers said that having control over their child’s diet and other oral health behaviors prevented their child from getting cavities. One caregiver explained “I’ve been able to brush his [my son’s] teeth daily since a very early age…and I know other parents, their kid won’t cooperate with brushing of the teeth, so they end up getting cavities.” Caregivers worried that susceptibility to cavities would increase as the children got older and exercised more control over their own diet and oral hygiene routines. One caregiver explained that their children were more at risk “now that they’re older [and] they’re eating more things with sugar in it and more processed stuff.”

Response efficacy and perceived benefits of topical fluoride

On average, caregivers expressed low confidence in the ability of topical fluoride to prevent caries for their child (mean = 4.2, SD = 2.7, range: 1 [not at all confident] to 10 [totally confident]). Most caregivers were knowledgeable about the general uses and benefits of topical fluoride. Some believed it was “effective at protecting and strengthening the outer layer of the tooth enamel.” Despite this, many caregivers did not believe it was an effective treatment to prevent cavities for their own child but acknowledged topical fluoride could be effective for other children.

Many caregivers believed topical fluoride was less effective at preventing cavities than other measures, such as practicing good oral hygiene habits and having a healthy diet. As one caregiver explained, “It [preventing caries] has to do with the good oral hygiene not so much just swiping on the [topical] fluoride.” Even if their child became more at risk to develop caries, some caregivers would rather “try other adjustments, like maybe adjust his [my son’s] diet more or being more diligent with his oral hygiene.”

Perceived consequences of topical fluoride

All caregivers had concerns about the potential consequences of using topical fluoride. These included health-related side effects and emotional and behavioral reactions their child had to fluoride.

While many caregivers described topical fluoride as being generally “not good,” others mentioned more specific health concerns, such as topical fluoride being “potentially carcinogenic,” a “neurotoxin, or a toxic chemical.” Several caregivers believed “most cures or most things that we use in modern Western medicine… have some sort of side effect.” Many caregivers worried about the potential long-term consequences of topical fluoride, including absorption and accumulation of topical fluoride through the child’s mouth causing health issues later in life. Some caregivers were also concerned that their child could “overdose” on fluoride, especially if they also brushed with fluoride toothpaste and drank fluoridated water. Many believed that “too much of everything is never good” and, therefore, did not want their child to receive topical fluoride.

Caregivers were also concerned about their child’s negative emotional or behavioral reactions to receiving topical fluoride treatment. One caregiver described topical fluoride as “an inconvenience for her [my child] to be tasting at the end of her treatment.” Another explained that “she [my child] threw up after it [topical fluoride] and wet her pants at the same time…I don’t want her to go through the emotional duress.” Caregivers of children with special health care needs were especially concerned about potential behavioral repercussions. One caregiver said,

They’re [my children] both severely affected by autism, they’re both non-verbal…One is more aggressive and self-injurious and violent than the other one. And so, for him, I’m especially careful about any medical procedures that I’m putting him through.

DISCUSSION

The results of our qualitative study indicate that constructs from both the EPPM and the HBM are relevant in understanding fluoride hesitancy behaviors. Most caregivers acknowledged the seriousness of cavities but did not believe their child was susceptible. Caregivers understood the general benefits of fluoride in preventing tooth decay but reported low response efficacy associated with topical fluoride for their child, especially compared to the other ways of reducing caries risk like good hygiene and diet. Almost all caregivers had concerns about topical fluoride and for most the perceived consequences outweighed any potential benefits. However, those who thought topical fluoride was effective were more willing to allow topical fluoride for their child, while those who did not generally refused.

In the EPPM, perceived threat is an essential precursor of health behavior change. In the current context, optimal behavior change would be fluoride acceptance by a hesitant or refusing parent whose high-risk child would benefit from fluoride. Threat is a function of severity and susceptibility [6]. Our findings indicate that although caregivers believe caries is a serious disease (high severity), most do not feel their child is particularly susceptible (low susceptibility). This is consistent with previous work on preventive dental visits for young children [8]. Collectively, our findings suggest that a significant barrier to oral health-related behavior change is low perceived susceptibility to caries.

Health literacy-based interventions could potentially address knowledge gaps that contribute to inaccurate perceptions about caries susceptibility [14]. Such approaches go beyond providing objective information or health education and involve communicating the child’s specific caries risk profile in the context of the constellation of potential risk factors. This may be a challenge given the limitations of current caries risk assessment tools as well as limited empirical research on effective ways to communicate caries risk in a dental setting [15]. In addition, many dentists recommend topical fluoride for all patients, which ignores caries risk and need. Requiring dentists to justify patient-level topical fluoride recommendations based on caries risk would create financial disincentive and elicit pushback from many dentists [16]. Future behavioral research should explore how dentists can effectively convey information to allow caregivers to accurately assess their child’s caries susceptibility and risk.

An assessment of perceived efficacy is the next step in behavior change in the EPPM (Figure 1). Efficacy is a function of self-efficacy and response efficacy [6]. We did not assess self-efficacy in our study, which focused on caregivers whose children had utilized dental care and had experiences refusing fluoride. As such, there were no caregivers who described low self-efficacy in their ability to get topical fluoride for their child. While self-efficacy to obtain topical fluoride may continue to be a problem, especially for low-income children who are uninsured or have public dental insurance, previous work indicates no relationship between income and refusal [4]. Thus, topical fluoride refusal may be equally likely among the very low-income families that have difficulties accessing dental care as it is among higher-income families that have easier access to care. In terms of fluoride refusal behaviors, self-efficacy may not be a relevant construct, though additional research is needed to confirm these findings.

Our findings regarding response efficacy were nuanced. Caregivers were able to elaborate on the benefits of fluoride but expressed low confidence in the effectiveness of topical fluoride preventing caries in their own child. The given explanation was that other compensatory behaviors, like good diet and hygiene, reduced the preventive value of topical fluoride. It may be easy for caregivers to maintain a low-sugar diet for children who are already consuming small amounts of sugar, but clinical observations indicate the difficulties most caregivers have in reducing added sugars for children who consume large amounts of sugar. Sustaining dietary changes may be even more difficult, especially as children get older and have more control over their diets, as we found in our study. Furthermore, toothbrushing has minimal caries prevention benefits when non-fluoridated toothpaste is used, which may be common among caregivers concerned about fluoride [17]. In fact, many caregivers in our study discussed concerns related to topical fluoride safety, which might further offset any perceived benefits of fluoride in general. Thus, caregivers need to understand the extent to which preferred compensatory behaviors adopted in lieu of topical fluoride are feasible and beneficial.

Interestingly, caregivers in our study also acknowledged that fluoride might be effective for other children, with the insinuation being that other children may not engage in optimal oral health behaviors. There are few published studies on differential perceptions caregivers have on the value of preventive care for one’s own kin versus others and the broader public health relevance of these differential perspectives [18]. Future research should continue to identify ways in which caregivers evaluate risks and benefits of preventive care.

For caregivers who are absolutely opposed to topical fluoride or may not yet be ready to accept topical fluoride, alternative strategies can be recommended. This includes discussing with caregivers the possibility of using fluoride toothpastes and drinking optimally fluoridated water. In addition, dietary changes should be discussed with an emphasis on the feasibility of reducing intake of added sugar, particularly sugar sweetened beverages. Dentists should document and monitor efforts of caregivers to reduce their child’s caries risk through such at-home behaviors.

There are at least four study limitations. First, because of our small and purposive sample, our findings have limited generalizability. Additional confirmatory research is needed with larger populations. Second, we only conducted a single interview with each participant. However, health behaviors are fluid, and may change based on evolving knowledge, beliefs, and experiences. Additional research is needed to understand the dynamic nature of decision-making. For example, constructs from the transtheoretical model, which accounts for behavioral fluidity, may be a useful model for further exploration [19]. A single interview may not be adequate for building trust and rapport with participants, and future work should adopt longitudinal interviews [20]. Third, we did not assess caries risk of the children of participating caregivers, which makes it difficult to interpret findings on perceived susceptibility. Future studies could elucidate the extent to which perceived susceptibility is linked to caries risk. Fourth, the study does not account for the interaction of community and individual influences in making decisions regarding topical fluoride. Research has shown that individuals make decisions based on both community acceptance and individual evaluation, factors neither the EPPM nor HBM account for [21].

In conclusion, our findings suggest that constructs from the EPPM and HBM are relevant in understanding caregivers’ decision-making processes around topical fluoride. Additional research is needed to further understand the ways in which caregivers assess caries susceptibility of their child as well as the behavioral and social factors that influence how caregivers think about the response efficacy of topical fluoride. This knowledge is critical in developing chairside behavioral interventions that dental and other health professionals can use to help caregivers make optimal preventive care decisions for their children.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the participants who kindly shared their beliefs, stories, and experiences with us. We also thank Dr. Stephanie Cruz, Ms. Daisy Patiño Nguyen, Dr. Fran Lewis, and Ms. Mary Ellen Shand for their assistance with the qualitative interviews and analysis. This study was supported by grant funding from the U.S. National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research [grant number: R01DE026741]. The authors acknowledge the people—past, present, and future—of the Dkhw’Duw’Absh, the Duwamish Tribe, the Muckleshoot Tribe, and other tribes on whose traditional lands they study and work.

REFERENCES

- 1.Weyant RJ, Tracy SL, Anselmo TT, Beltrán-Aguilar ED, Donly KJ, Frese WA, et al. Topical fluoride for caries prevention: executive summary of the updated clinical recommendations and supporting systematic review. J Am Dent Assoc. 2013;144(11): 1279–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marinho VCC, Worthington HV, Walsh T, Clarkson JE. Fluoride varnishes for preventing dental caries in children and adolescents. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;(7):CD002279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chi DL. Parent refusal of topical fluoride for their children. Dent Clin N Am. 2017;61(3):607–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chi DL. Caregivers who refuse preventive care for their children: the relationship between immunization and topical fluoride refusal. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(7):1327–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chi DL, Basson AA. Surveying dentists’ perceptions of caregiver refusal of topical fluoride. JDR Clin Trans Res. 2018;3(3):314–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Witte K Putting the fear back into fear appeals: the extended parallel process model. Commun Monogr. 1992;59(4):329–49. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Becker MH. The health belief model and personal health behavior. Health Educ Monogr. 1974;2:324–508. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Askelson NM, Chi DL, Momany E, Kuthy R, Ortiz C, Hanson JD, et al. Encouraging early preventive dental visits for preschool-aged children enrolled in Medicaid: using the extended parallel process model to conduct formative research: early preventive dental visits. J Public Health Dent. 2014. Winter;74(1):64–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Deshpande S, Basil MD, Basil DZ. Factors influencing healthy eating habits among college students: an application of the health belief model. Health Mark Q. 2009;26(2):145–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.O’Connor PJ, Martin B, Weeks CS, Ong L. Factors that influence young people’s mental health help-seeking behaviour: a study based on the health belief model. J Adv Nurs. 2014;70(11): 2577–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Opel DJ, Taylor JA, Zhou C, Catz S, Myaing M, Mangione-Smith R. The relationship between parent attitudes about childhood vaccines survey scores and future child immunization status: a validation study. JAMA Pediatr. 2013;167(11):1065–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Crabtree B, Miller W. A template approach to text analysis: developing and using codebooks. In: Crabtree B, Miller W, editors. Doing Qualitative Research. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1999. p. 163–77. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–101. 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brega AG, Johnson RL, Schmiege SJ, Wilson AR, Jiang L, Albino J. Pathways through which health literacy is linked to parental Oral health behavior in an American Indian tribe. Ann Behav Med. 2021;55(11):1144–55. 10.1093/abm/kaab006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Divaris K Predicting dental caries outcomes in children: a “risky” concept. J Dent Res. 2016;95(3):248–54. 10.1177/0022034515620779 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yokoyama Y, Kakudate N, Sumida F, Matsumoto Y, Gilbert GH, Gordan VV. Evidence-practice gap for in-office fluoride application in a dental practice-based research network. J Public Health Dent. 2016;76(2):91–7. 10.1111/jphd.12114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Walsh T, Worthington HV, Glenny AM, Marinho VC, Jeroncic A. Fluoride toothpastes of different concentrations for preventing dental caries. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;3(3):CD007868. 10.1002/14651858.CD007868.pub3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Reich JA. Neoliberal mothering and vaccine refusal: imagined gated communities and the privilege of choice. Gend Soc. 2014; 28(5):679–704. 10.1177/0891243214532711 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wade KJ, Coates DE, Gauld RD, Livingstone V, Cullinan MP. Oral hygiene behaviours and readiness to change using the Trans-Theoretical model (TTM). N Z Dent J. 2013;109(2):64–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Coiro J, Knobel M, Lankshear C, Leu DJ, editors. Handbook of Research on New Literacies. London, UK: Routledge; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Campbell BK. Fidelity in public health clinical trials: considering provider-participant relationship factors in community treatment settings. J Public Health Dent. 2011;71(1):S64–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.