Abstract

Objective

Dog bite injuries remain a public health concern for two key reasons: the physical threat to health following attack and the infective sequelae a canine bite can incur. Facial bite injuries can result in significant emotional, psychological and physical trauma to victims involved. This narrative review elucidates the current presentation and management of dog bite injuries to the face.

Data Sources and Methods

A literature search was conducted electronically using the search terms “dog bite” and “face” and “management” using the National Library of Medicine (Pubmed) and the Cochrane Library. There were no time nor language restrictions. A total of 79 studies were initially retrieved using the search algorithm. After screening of the titles and abstracts, 9 full texts were retrieved, and a total of 7 studies included.

Results

The number of patients included in each study following a dog bite ranged from 40 to 223. The percentage of children included in each study (aged <18 years old) ranged from 27.5% to 100%. The majority of dog bite injuries to the face were managed by primary repair, ranging from 56.3% to 100%. Prophylactic antibiotics were used in most studies for dog bite injuries, ranging from 81% to 100%. The secondary infection rate following a dog bite ranged from 0 to 35%.

Conclusion

This review highlights that children are disproportionately affected by canine bite injuries to the face relative to adults. The dog involved in the attack is typically known to the victim, with the lips, the cheek and the nose representing the most common sites of facial injury. More units are managing such injuries with primary repair and prophylactic antibiotics. Reconstructive procedures most commonly involve a local or advancement flap, a full thickness skin graft or a split skin graft. These are typically performed by Plastic Surgery and Maxillofacial Surgery specialists.

Keywords: Trauma, Craniofacial

INTRODUCTION

Animal bites remain a significant public health issue, with the number of these injuries increasing annually. Dog bites represent the most common mammalian bites treated in emergency departments, followed by cat bites and human bites. 1

In the United Kingdom, around 250 000 people who have been bitten by dogs seek medical treatment from minor injuries and emergency units per year. 2 Children are disproportionately affected by dog bites when compared to adults. 3 Younger children, in particular, have an increased likelihood of being bitten on the face, given their shorter stature and the disproportionate size of their head relative to their body. 4 , 5 , 6

There is a paucity of data on global estimates of dog bite incidence, however studies suggest that they account for tens of millions of injuries annually. 7 Dog bite fatality rates are higher in low‐ and middle‐income countries than in high‐income countries. This is believed to be attributed to the prevalence of rabies in many of these countries and a lack of post‐exposure treatment and suitable access to health care. 7

Facial bite injuries result in significant emotional, psychological and physical trauma to victims involved. 8 The face is the third most commonly affected area from dog bites, following the upper and lower limbs. 9 Within the face, the nose and lips represent the most affected sites. 9

This narrative review aims to elucidate the current presentation and management of dog bite injuries to the face. Peer‐reviewed articles were identified using the National Library of Medicine (Pubmed) and the Cochrane Library using the search term “dog bite”, “face” and “management.” All information was sorted and analysed for suitability for inclusion and relevant articles were retained.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

A literature search was conducted electronically using the search terms “dog bite” and “face” and “management” using the Pubmed and the Cochrane Library. There were no time nor language restrictions.

Inclusion criteria

All studies reporting the management of dog bite injuries to the face with >1 patient reported.

All age groups.

Exclusion criteria

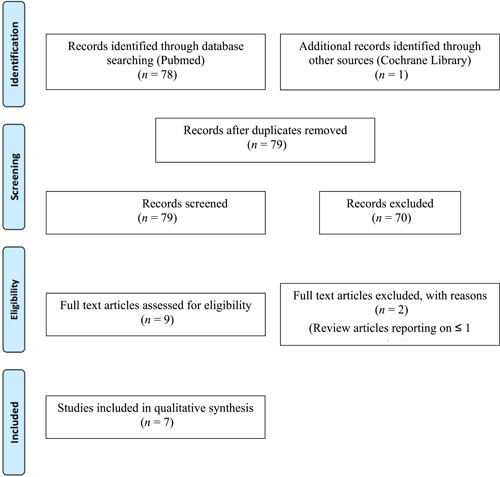

All review articles were excluded from this study (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The flow diagram of selecting articles

RESULTS

A total of seven studies were included for this narrative review. The number of patients included in each study following a dog bite ranged from 40 to 223 (Table 1, Table 2, Table 3).

Table 1.

List of studies included

| Study | Study type | Year | Country | Number of patients |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Javaid et al. 10 | Retrospective case series | 1998 | UK | 40 |

| Wolff 11 | Case series | 1998 | Germany | 94 |

| Mitchell et al. 12 | Retrospective case series | 2003 | USA | 44 |

| Hersant et al. 13 | Retrospective case series | 2012 | France | 77 |

| Macedo et al. 14 | Prospective Case Series | 2016 | Brazil | 146 |

| Chávez‐Serna et al. 15 | Retrospective Case Series | 2019 | Mexico | 416 |

| Piccart et al. 16 | Retrospective Case Series | 2019 | Belgium | 223 |

Table 2.

Included study outcomes (%)

| Study | <18 years old | Mx with primary repair | Secondary infection rate | Prophylactic antibiotic use |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Javaid et al. 10 | 27.5–57.5 | 77.5 | 5 | 97.5 |

| Wolff 11 | 54.3 (<15 years old) | 56.3 | 7.6–13.3 | 84 |

| Mitchell et al. 12 | 100 | 95.5 | 31–35 | 81 |

| Hersant et al. 13 | 100 | 100 | 24.7 | 100 |

| Macedo et al. 14 | 100 | 69.8 | 0 | 100 |

| Chávez‐Serna et al. 15 | 63 | 74.3 | 2 | 100 |

| Piccart et al. 16 | 49.3 | 63.2 | 2.2 | 100 |

Table 3.

Included studies: details of injury and surgical repair

| Study | Site of injury (%) | Time from injury to medical presentation | Methods of repair | Requiring secondary surgical procedures (%) | Specialty performing repair | Dog known to patient (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Javaid et al. 10 |

Lip – 37.5 Nose – 17.5 Multiple – 30.0 Other – 15.0 |

<24 hours – 72.5% | Primary repair‐ 77.5% Reconstructive procedures (advancement flap/SSG/FTSG/Rhomboid Flap) – 22.5% | 2.5 (Necrosis of free composite lip graft requiring debridement and FTSG) | Plastic Surgery | Not reported |

| Wolff 11 |

Lip – 35.1 Cheek – 24.5 Nose – 14.9 Ears – 14.9 Other – 10.6 |

<24 hours – 81.9% |

Primary repair – 56.3% Reconstructive procedures: Local flap – 6.4% Reconstruction of helix of nose – 2.1% Supramalleolar flap – 2.1% |

8.5 (Secondary cosmetic correction of lips and cheeks; correction of cicatricial hypertrophy) | Maxillofacial Surgery | 75 |

| Mitchell et al. 12 | Multiple – 98.0 | Not reported |

Primary repair – 95.5% Reconstructive procedures:nasal reconstruction – 2.3% |

81 (average number of procedures per child was 3.8, including scar revision and revision cranioplasties) | ENT Surgery | 79 |

| Hersant et al. 13 |

Multiple – 71.4 In order of descending frequency: Cheek>Lips>Eyelid>Nose |

Not reported | Primary repair – 100% | 28.6 (Reconstructive procedures including: Cheiloplasty, FTSG, SSG) | Maxillofacial and plastic surgery | 96 |

| Macedo et al. 14 |

Zygmoa – 30.1 Scalp – 26.7 Front – 14.4 Nose – 10.3 Lip – 8.9 Ears – 6.2 Eyelids 3.4 |

<24 hours – 89.7% |

Primary repair – 69.8% Reconstructive procedures:grafting – 26.1% Local flap – 4.1% |

0 | Plastic surgery | Not reported |

| Chávez‐Serna et al. 15 |

Face – 63.1 (Lip and nose areas at 24.8%) Head and neck – 1.5 Multiple – 12.1 |

Not reported |

Primary repair – 74.3% Reconstructive procedures – 21.4% (Local flaps 16.8%). |

0 | Plastic surgery | Not reported |

| Piccart et al. 16 |

Lip – 47.5 Cheek – 27.4 Nose – 20.6 Periorbital – 12.1 |

Not reported |

Primary repair – 63.2% Reconstructive procedures – local flaps 6.8%, Skin graft – 26.7% |

4.5 (Secondary direct closure) | Maxillofacial surgery | Not reported |

The percentage of children included in each study (aged <18 years old) ranged from 27.5% (Javaid et al. 10 ) to 100% (Mitchell et al. 12 Hersant et al. 13 Macedo et al. 14 ). The majority of dog bite injuries to the face were managed by primary repair, ranging from 56.3% (Wolff et al. 11 ) to 100% (Hersant et al. 13 ). Prophylactic antibiotics were used in most studies for dog bite injuries, ranging from 81% (Mitchell et al. 12 ) to 100% (Macedo et al. 14 Chávez‐Serna et al. 15 Hersant et al. 13 Piccart et al. 16 ). The secondary infection rate following a dog bite ranged from 0 (Macedo et al. 14 ) to 35% (Mitchell et al. 12 ).

The most common sites of facial injury following a dog bite included the lips (8.9%-45.7%), the cheek (24.5%-27.4%) and the nose (10.3%-24.8%). A significant proportion of patients presented with multiple injuries, accounting for 30% (Javaid et al. 10 ) to 98% (Mitchell et al. 12 ).

In the studies reporting time from injury to presentation to a medical doctor, the majority of patients presented within 24 hours, ranging from 72.5% (Javaid et al. 10 ) to 89.7% (Macedo et al. 14 ).

In cases where primary repair was not performed, reconstructive procedures constituted 2.3% (Mitchell et al. 12 ) to 33.5% (Piccart et al. 16 ) of cases. These procedures most commonly involved a local or advancement flap, a full thickness skin graft or a split skin graft. A range of surgical specialties performed surgical repairs of dog bite injuries ‐ most commonly both plastic surgery and maxillofacial surgery, followed by ENT surgery.

The percentage of cases requiring secondary surgical procedures demonstrated significant range, from 0 (Chávez‐Serna et al., 15 Macedo et al. 14 ) to 81% (Mitchell et al. 12 ). This included secondary direct closure, scar or cosmetic revision and correction of graft failure. The majority of dogs were known to their victims where reported, ranging from 75% (Mitchell et al.12) to 96% (Hersant et al. 13 ).

DISCUSSION

Dog bite injuries remain a public health concern for two key reasons: the physical threat to health following attack and the infective sequelae a canine bite can incur. This is particularly pertinent due to the scale of the issue. Animal bite injuries account for 1%-2% of all Accident and Emergency presentations in the UK. 17 Around half of people will be bitten by an animal during their lifetime. And 90% of this is attributable to domestic animals. 18 One of the main injury sites is the head, particularly in children, which increases morbidity. 19

The most common complication of dog bites is infection, secondary to wound contamination by both Gram‐positive and Gram‐negative microorganisms in the saliva. 20 The key organisms from infected dog and cat bite wounds includes Pasteurella multocida, Staphylcococcus aureus, viridians streptococci, Capnocytophaga canimorsus and oral anaerobes. 21 These pathogens may cause severe secondary infections, resulting in sepsis and even death. In addition to local wound infection, dog bite injuries can result in significant morbidity: this is primarily from infective complications, structural complications and psychological complications. Infective complications include: abscesses, tenosynovitis, septic arthritis, osteomyelitis, tetanus and sepsis as described. Structural complications include soft tissue injury, neuro‐vascular injury and fractures. Distress, anxiety and depression are demonstrable psychological consequences following dog bite injuries. 22

All studies included in this review highlight the significant proportion of children (<18 years old) affected by dog bite injuries to the face. It is reported that children are the main victims of canine attacks, with regards to both morbidity and mortality. 14 Our study demonstrates that the dog involved in the attack is typically known to the victim, accounting for between 75% and 96% of cases. 12 , 13 The lips, the cheek and the nose represented the most common sites of facial injury following a dog bite in this review. Children playing with dogs may be a causative factor in such facial injuries.

Immediate treatment consisted of thorough wound irrigation, tetanus immunisation and debridement. Most studies highlighted the widespread use of prophylactic antibiotics in dog bite injuries to the face. This is in keeping with recommendations by the National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE), who advise early irrigation and or wound debridement and prescribing of prophylactic oral antibiotics for all animal bites to the face. 23 If there are no signs of infection, and the wound is >24-48 hours old, prophylactic antibiotics are not recommended. 23 The widespread use of prophylactic antibiotics in these studies may account for the relatively low secondary infection rates at 30 days following injury.

The treatment of choice for dog bite injuries to the face was largely primary closure in the included studies. Reconstructive procedures accounted for the remainder of cases, most commonly involving a local or advancement flap, a full thickness skin graft or a split skin graft. We note the common involvement of both plastic and maxillofacial surgeons for such procedures, followed by ENT surgeons. Our study also demonstrates the need for secondary surgical procedures accounting for a minority of cases. However, one study highlighted 81% of patients requiring multiple procedures. 12 This may be accounted for by the severity of presenting injuries in this case, with 98% of patients with a dog bite having multiple initial injuries in this study. 12

CONCLUSIONS

Dog bite injuries to the face can result in distressing physical and psychological consequences. This review highlights that children are disproportionately affected by canine bite injuries to the face relative to adults. The dog involved in the attack is typically known to the victim, with the lips, the cheek and the nose representing the most common sites of facial injury. More units are managing such injuries with primary repair and prophylactic antibiotics. Reconstructive procedures most commonly involve a local or advancement flap, a full thickness skin graft or a split skin graft. These are typically performed by Plastic Surgery and Maxillofacial Surgery specialists.

LIMITATIONS

It is difficult to ascertain whether prophylactic antibiotics directly result in low secondary infection rates following dog bites, particularly as no control arm is used in the included studies. A comparison of early versus late surgical treatment and prophylactic antibiotic versus no antibiotic would be useful trial arms for future studies.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

There are no conflicts of interest to declare.

CREDIT AUTHOR STATEMENT

Mr Shirwa Sheik Ali ‐ Conceptualization, Data Curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing ‐ original draft.

Dr Sharaf Sheik Ali ‐ Conceptualization, Data Curation, Formal analysis, Writing ‐ review and editing.

Ali SS, Ali SS. Dog bite injuries to the face: a narrative review of the literature. World J Otorhinolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2022;8:239‐244. 10.1016/j.wjorl.2020.11.001

REFERENCES

- 1. Edens MA, Michel JA, Jones N. Mammalian Bites In The Emergency Department: Recommendations For Wound Closure, Antibiotics, And Postexposure Prophylaxis. Emerg Med Pract. 2016;18:1‐20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Morgan M, Palmer J. Dog bites. BMJ. 2007;334(7590):413‐417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Sacks JJ, Kresnow M, Houston B. Dog bites: how big a problem. Inj Prev. 1996;2:52‐54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hon KL, Fu CC, Chor CM, et al. Issues associated with dog bite injuries in children and adolescents assessed at the emergency department. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2007;23:445‐449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Brogan TV, Bratton SL, Dowd MD, Hegenbarth MA. Severe dog bites in children. Pediatrics. 1995;96:947‐950. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Akhtar N, Smith MJ, McKirdy S, Page RE. Surgical delay in the management of dog bite injuries in children, does it increase the risk of infection. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2006;59:80‐85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. World Health Organization . Animal Bites. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/animal-bites. Accessed on 10/04/2020.

- 8. Peters V, Sottiaux M, Appelboom J, Kahn A. Posttraumatic stress disorder after dog bites in children. J Pediatr. 2004;144:121‐122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Chhabra S, Chhabra N, Gaba S. Maxillofacial injuries due to animal bites. J Maxillofac Oral Surg. 2015;14:142‐153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Javaid M, Feldberg L, Gipson M. Primary repair of dog bites to the face: 40 cases. J R Soc Med. 1998;91:414‐416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Wolff KD. Management of animal bite injuries of the face: experience with 94 patients. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1998;56:838‐843 discussion 843‐844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Mitchell RB, Nañez G, Wagner JD, Kelly J. Dog bites of the scalp, face, and neck in children. Laryngoscope. 2003;113:492‐495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hersant B, Cassier S, Constantinescu G, et al. Facial dog bite injuries in children: retrospective study of 77 cases. Ann Chir Plast Esthet. 2012;57:230‐239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Macedo JL, Rosa SC, Queiroz MN, Gomes TG. Reconstruction of face and scalp after dog bites in children. Rev Col Bras Cir. 2016;43:452‐457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Chávez‐Serna E, Andrade‐Delgado L, Martínez‐Wagner R, Altamirano‐Arcos C, Espino‐Gaucín I, Nahas‐Combina L. Experience in the management of acute wounds by dog bite in a hospital of third level of plastic and reconstructive surgery in Mexico. Cir Cir. 2019;87:528‐539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Piccart F, Dormaar JT, Coropciuc R, Schoenaers J, Bila M, Politis C. Dog Bite Injuries in the Head and Neck Region: A 20‐Year Review. Craniomaxillofac Trauma Reconstr. 2019;12:199‐204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Chaudhry MA, Macnamara AF, Clark S. Is the management of dog bite wounds evidence based? A postal survey and review of the literature. Eur J Emerg Med. 2004;11:313‐317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kennedy SA, Stoll LE, Lauder AS. Human and other mammalian bite injuries of the hand: evaluation and management. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2015;23:47‐57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Weiss HB, Friedman DI, Coben JH. Incidence of dog bite injuries treated in emergency departments. JAMA. 1998;279:51‐53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Griego RD, Rosen T, Orengo IF, Wolf JE. Dog, cat, and human bites: a review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;33:1019‐1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Stefanopoulos PK, Tarantzopoulou AD. Facial bite wounds: management update. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2005;34:464‐472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. De Keuster T, Lamoureux J, Kahn A. Epidemiology of dog bites: a Belgian experience of canine behaviour and public health concerns. Vet J. 2006;172:482‐487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence . Bites ‐ human and animal. https://cks.nice.org.uk/bites-human-and-animal#!scenarioRecommendation:5. Accessed on 10/04/2020.