Abstract

Transcription by ς54-RNA polymerase holoenzyme requires an activator that catalyzes isomerization of the closed promoter complex to an open complex. We examined mutant forms of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium ς54 that were defective in transcription initiation but retained core RNA polymerase- and promoter-binding activities. Four of the mutant proteins allowed activator-independent transcription from a heteroduplex DNA template. One of these mutant proteins, L124P V148A, had substitutions in a sequence that had not been shown previously to participate in the prevention of activator-independent transcription. The remaining mutants did not allow efficient activator-independent transcription from the heteroduplex DNA template and had substitutions within a conserved 20-amino-acid segment (Leu-179 to Leu-199), suggesting a role for this sequence in transcription initiation.

Bacterial RNA polymerase holoenzyme consists of a core enzyme (α2ββ′) and a dissociable ς subunit. Bacteria often contain multiple ς factors with individual sequence specificities that direct holoenzyme to different classes of promoters (22). ς54 is a distinctive bacterial sigma factor that does not share significant sequence homology with other sigma factors. Transcription initiation by ς54-RNA polymerase holoenzyme (ς54-holoenzyme) occurs through a distinct mechanism that involves an activator or enhancer-binding protein (3). ς54-Holoenzyme binds to promoters to form stable closed complexes. Isomerization of these closed complexes to transcriptionally active open complexes requires an enhancer-binding protein, which generally binds to sites upstream of the promoter and contacts ς54-holoenzyme through DNA looping. This isomerization requires nucleoside triphosphate hydrolysis by the enhancer-binding protein.

Deletion analysis of ς54 has revealed that the protein consists of at least three functional regions (7, 16, 26, 32, 33). The 50 amino-terminal residues of ς54 constitute region I, which is rich in glutamine and leucine residues and plays a direct role in transcriptional activation (16, 17). Region II of ς54 from enteric bacteria, which extends from residue 50 to residue 120 and is highly acidic, appears to influence the rate of open complex formation, as well as suppress nonspecific DNA binding by holoenzyme (4, 32). Region III consists of 360 carboxy-terminal residues and contains determinants for binding of both core RNA polymerase and promoter DNA (7, 27, 28, 33). Additional functions for region III are likely, as some substitutions in this region disrupt one or more steps in transcription initiation following initial promoter recognition (11, 18).

When region I of ς54 is deleted, the resulting holoenzyme assumes a conformation believed to reflect polymerase isomerization (6). This isomerization is inhibited by a peptide containing the region I sequence, indicating that region I can elicit its effects on holoenzyme in trans (6, 14). Holoenzyme containing ς54 with region I deleted fails to initiate transcription under normal conditions but can initiate transcription independently of enhancer-binding protein from a transiently melted or premelted DNA template (6, 29). These studies suggest that region I inhibits isomerization of the holoenzyme to a form that can stably associate with single-stranded DNA (4). Productive interaction with the enhancer-binding protein apparently relieves this inhibition and permits transcription initiation in a reaction that requires nucleotide hydrolysis by the enhancer-binding protein (14).

We previously isolated several mutant forms of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium ς54 that were defective in transcription initiation but retained core- and DNA-binding activities (18). Further analysis of these mutant ς54 proteins, the results of which are presented here, revealed that certain amino acid substitutions in regions I and III allowed the holoenzyme to initiate transcription from a heteroduplex DNA template in the absence of enhancer-binding protein, suggesting that sequences within these regions influence isomerization of the holoenzyme. The remaining ς54 mutant proteins had amino acid substitutions within region III and represented a second class of mutants that did not allow efficient transcription from the heteroduplex template in the absence of enhancer-binding protein. The strains and plasmids used in this study are described in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant characteristic(s) | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| S. enterica serovar Typhimurium | ||

| TRH107 | Δ(prt proAB)-ataP::[(P22 int3 c2-ts29) sieA44 mnt::Kn9 PnifH arc(Am) H1605 ant′-′lacZYA Δ9-al] ntrA209::Tn10 | 1 |

| TRH134 | leu-414(Am) hsdL(r−m+) Fels− ΔntrA8455 | 18 |

| E. coli YMC11 | endA1 thi-1 hsdK17 supR44 Δlac-169 hutCK ΔglnALG2000 ntrA::Tn10 | 2 |

| Plasmids | ||

| pALTER-1 | Aps Tcr | Promega |

| pJES534 | pTZ19U S. enterica serovar Typhimurium glnA promoter regulatory region | 24 |

| pL143 | pUC13 Plac-S. meliloti dctD(Δ1–142) | 19 |

| pRKRMAZ:+UAS | pRK290 S. meliloti dctA′-′lacZYA | 19 |

| pTRH17 | pACYC184 Plac-dctD(Δ1–142) | This study |

| pMK8 | pACYC184 dctA′-′lacZYA Plac-dctD(Δ1–142) | This study |

| pSA4 | pCyt-3 Plac-ntrA lacIq | 1 |

| pMK11 | pALTER-1 Apr Tcr Plac-ntrA | 18 |

| pNTRA1 | pSA4 ntrA allele (L37P) | 18 |

| pNTRA2 | pSA4 ntrA allele (L46P) | 18 |

| pNTRA4 | pSA4 ntrA allele (L333P) | 18 |

| pNTRA5 | pSA4 ntrA allele (E32K G189V) | 18 |

| pNTRA6 | pSA4 ntrA allele (L124P V148A) | 18 |

| pNTRA18 | pSA4 ntrA allele (L199P D231G) | 18 |

| pNTRA30 | pSA4 ntrA allele (L179P) | This study |

| pWA328 | pMK11 ntrA allele (W328A) | This study |

| pKA331 | pMK11 ntrA allele (K331A) | This study |

| pRA336 | pMK11 ntrA allele (R336A) | This study |

| pRA342 | pMK11 ntrA allele (R342A) | This study |

| pQA351 | pMK11 ntrA allele (Q351A) | This study |

L179P retains core- and promoter-binding activities.

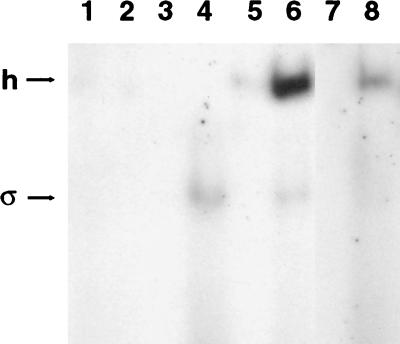

Several mutant forms of ς54 were isolated previously that failed to function normally at the ς54-dependent glnA promoter (glnAp2) but retained promoter-binding activities (20). We included here a new ς54 mutant protein, L179P, that was identified using the same screening procedure following random mutagenesis of a plasmid-borne copy of ntrA (encodes ς54) with the Epicurian Coli XL1-Red strain (Stratagene, La Jolla, Calif.). We previously used a gel mobility shift assay with labeled oligonucleotides that corresponded to the −9 to −29 region of the Sinorhizobium meliloti nifH promoter to examine interactions between the mutant forms of ς54 and core RNA polymerase, as well as the binding of the mutant proteins to promoter sequences (20). One oligonucleotide was double stranded over its entire length (double-stranded probe), while in the second oligonucleotide residues −11 to −9 of the template strand were single stranded (fork junction probe). Guo and Gralla first demonstrated fork junction DNA-binding activity of ς54 using these probes (15), and we subsequently found that the ς54-holoenzyme bound the fork junction probe significantly better than it did the double-stranded probe (18).

We examined the binding of the L179P-holoenzyme to the fork junction and double-stranded probes. As observed with the wild-type holoenzyme, the L179P-holoenzyme shifted the fork junction probe more efficiently than the double-stranded probe (Fig. 1). L179P produced less of the holoenzyme-shifted species than wild-type ς54, suggesting that this mutant protein had reduced affinity for either core RNA polymerase or fork junction DNA. These gel mobility shift data, however, demonstrate that like the other mutant forms of ς54 described previously (20), L179P still binds the core and directs the holoenzyme to promoter sequences.

FIG. 1.

Gel mobility shift assay with double-stranded and fork junction probes. Binding of mutant forms of ς54-holoenzyme to the S. meliloti nifH promoter was analyzed by a gel mobility shift assay as previously described (18). Two different DNA probes were used for the gel mobility shift assays. One probe contained 21 bp of double-stranded DNA that included residues −9 through −29 of the nifH promoter. The second probe had 18 bp of double-stranded DNA, which included residues −12 through −29 of the nifH promoter plus a three-base 5′ overhang of the template strand that corresponded to residues −9 through −11. Binding reaction mixtures contained 5 nM DNA probe and 6 μg of sonicated calf thymus DNA/ml along with 300 nM core RNA polymerase (lanes 1 and 2), 600 nM hexahistidine-tagged ς54 (lanes 3 and 4), 300 nM core plus 600 nM hexahistidine-tagged ς54 (lanes 5 and 6), and 300 nM core plus 600 nM hexahistidine-tagged L179P (lanes 7 and 8). Core RNA polymerase and histidine-tagged ς54 proteins were purified as previously described (20, 23). The double-stranded probe was used in odd-numbered lanes, while the fork junction probe was used in even-numbered lanes. The holoenzyme-shifted (h) and ς54-shifted (ς) species are indicated. Unbound probes are not shown.

Mutant forms of ς54 can be cross-linked to DctD.

S. enterica serovar Typhimurium ς54 can be chemically cross-linked to the enhancer-binding protein S. meliloti C4-dicarboxylic acid transport protein D (DctD), suggesting that ς54 is a primary target for the enhancer-binding protein (20). Consistent with this hypothesis, mutant forms of DctD that failed to activate transcription and cross-linked poorly to ς54 have been isolated (31). Further support of this hypothesis comes from the observation that ς54 bound to heteroduplex DNA in the absence of core RNA polymerase undergoes a conformational change in a reaction that requires enhancer-binding protein and nucleotide hydrolysis (8).

We wished to determine if any of the ς54 mutant proteins were deficient in cross-linking to DctD and therefore altered in the ability to make productive contact with the enhancer-binding protein. Since the ς54 mutant proteins were isolated originally based on their failure to function with nitrogen regulatory protein C (NtrC) at glnAp2 in vivo (18), we first verified that these mutant proteins were also defective in functioning with DctD in vivo. For these assays, we used DctD(Δ1–142), which is a truncated, constitutively active form of the protein that lacks the first 142 amino-terminal residues (21). We examined the ability of the mutant forms of ς54 to function with DctD(Δ1–142) in activating transcription from a plasmid-borne dctA′-′lacZ reporter gene in Escherichia coli strain YMC11, which otherwise lacks ς54. DctD-mediated transcriptional activation with the mutant forms of ς54 ranged from 1 to 19% of the activity achieved with wild-type ς54 (Table 2). These values were consistent with the activities observed for the mutant ς54 proteins with NtrC at glnAp2 in vivo (18).

TABLE 2.

Abilities of mutant forms of ς54 to function with DctD(Δ1–142) at a dctA′-′lacZ reporter gene in vivo

| ς54 protein | Transcriptional activation from dctA′-′lacZ reporter gene

|

|

|---|---|---|

| β-Galactosidase activity (Miller units)a | % Wild-type activity | |

| L37P | 1,670 ± 23 | 10 |

| L46P | 3,130 ± 210 | 19 |

| L179P | 301 ± 33 | 1.8 |

| L333P | 310 ± 26 | 1.9 |

| E32K G189V | 555 ± 16 | 3.4 |

| L124P V148A | 136 ± 2.4 | 0.8 |

| L199P D231G | 294 ± 10 | 1.8 |

| Wild type | 16,450 ± 370 | 100 |

β-Galactosidase activities were determined in E. coli strain YMC11 containing the dctA′-′lacZ reporter plasmid pMK8 along with plasmids carrying the mutant ntrA alleles.

Each of the mutant forms of ς54 was purified and examined for the ability to cross-link to DctD(Δ1–142) using succinimidyl 4-(N-maleimidomethyl)cyclohexane-1-carboxylate as the cross-linking reagent as described previously (20). All of the mutant ς54 proteins cross-linked efficiently to DctD(Δ1–142) (data not shown), indicating that none of them were defective in gross interactions with this enhancer-binding protein. Since the cross-linking assay provides only a qualitative assessment of interactions between ς54 and DctD, we cannot rule out the possibility that some of the mutant proteins had reduced affinities for DctD or that some of the substitutions in these mutant proteins interfered with specific contacts between ς54 and DctD required for transcriptional activation.

Certain mutant forms of ς54 allow activator-independent transcription.

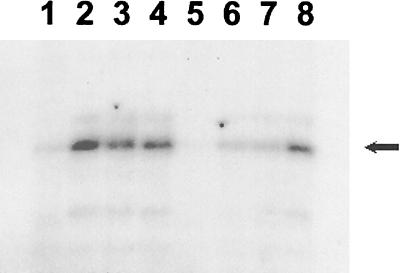

We initially used an in vitro transcription assay to examine the abilities of the ς54 mutant proteins to support transcription from a supercoiled template that carried the S. enterica serovar Typhimurium glnA promoter region. In this transcription assay, heparin was added immediately before the nucleotides to prevent reinitiation but allow transcription from stable open complexes. None of the ς54 mutant proteins supported transcription under these conditions, except the L46P mutant protein, which had given the highest activity in vivo (Table 2). The level of transcript generated with the L46P mutant protein was ∼5% of that generated with wild-type ς54 (Fig. 2). Addition of heparin to the transcription assay reaction after addition of the nucleotides did not alter the results of the assays with the mutant proteins (data not shown). These data confirmed our earlier in vivo findings that these mutant ς54 proteins were defective in their function at glnAp2 (18).

FIG. 2.

In vitro transcription with mutant forms of ς54 from the glnA promoter regulatory region on a supercoiled DNA template. Transcription assays were carried out as described previously (24, 31). Assay reaction mixtures contained 400 nM maltose-binding protein–NtrC, 20 mM carbamoyl phosphate, 100 nM core RNA polymerase, and a 300 nM concentration of either hexahistidine-tagged ς54 (lane 1), L37P (lane 2), L46P (lane 3), E32K G189V (lane 4), L124P V148A (lane 5), L179P (lane 6), L199P D231G (lane 7), or L333P (lane 8). The arrow indicates the transcript from the glnA promoter.

Previous studies demonstrated that when region I of ς54 is deleted, the resulting holoenzyme can initiate transcription in the absence of enhancer-binding protein from a premelted, heteroduplex DNA template (6). We used this linear, heteroduplex template to determine if any of the mutant ς54 proteins would allow activator-independent transcription. The template spanned nucleotides −60 to +28 of the S. meliloti nifH promoter, and the DNA strands from −10 to −1 were noncomplementary (6).

The wild-type ς54-holoenzyme was only able to initiate transcription from the heteroduplex template weakly (Fig. 3, lane 1). Likewise, holoenzymes formed with the L179P mutant protein, the L199P D231G double-mutant protein, or the E32K G189V double-mutant protein initiated transcription from the heteroduplex template poorly. In contrast, holoenzymes containing L37P, L46P, L333P, or the double mutation L124P V148A initiated transcription efficiently from the heteroduplex template (Fig. 3, lanes 2 to 4 and 8). Amino acid substitutions in ς54 that result in activator-independent transcription have been described previously (10, 11, 26, 29), with the substitutions in these mutant proteins occurring primarily within a leucine-rich patch of region I and a very limited number of sites in region III. In general, these previous activator-independent mutant proteins retained significant activity in vivo. In contrast, holoenzymes with L37P, L333P, and the double mutation L124P V148A were severely impaired in the ability to function in vivo and in that regard are more like region I deletion mutant enzymes which do not support transcription initiation from homoduplex DNA templates (8). This result is not surprising, however, given that the mutant proteins in this study were chosen based on their failure to function at glnAp2 in vivo (18).

FIG. 3.

In vitro transcription assays using a heteroduplex DNA template. Transcription assays were carried out using a heteroduplex DNA template that spanned residues −60 to +28 of the S. meliloti nifH promoter and was noncomplementary between residues −10 and −1. The heteroduplex template was generated using two oligonucleotides as previously described (6). Transcription assays were conducted as previously described (6), except that 7.5 μCi of [α-32P]CTP (3,000 Ci/mmol) was used to label the transcripts. Reaction mixtures contained 100 nM core RNA polymerase, 300 nM hexahistidine-tagged ς54 proteins, and 30 nM heteroduplex DNA template. The ς54 proteins assayed were the wild type (lane 1) and the L37P (lane 2), L46P (lane 3), L333P (lane 4), E32K G189A (lane 5), L179P (lane 6), L199P D231G (lane 7), and L124P V148A (lane 8) mutant proteins. The arrow indicates the 28-base transcript.

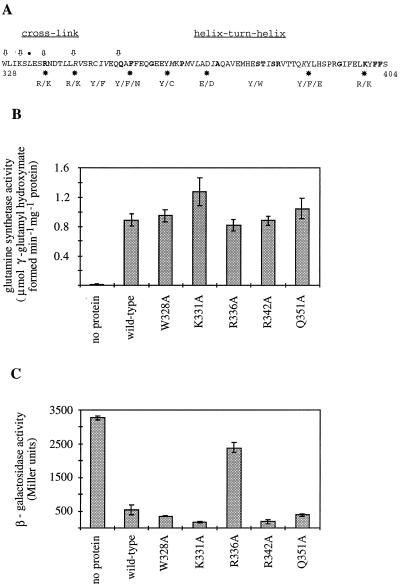

Alanine scanning mutagenesis of the region around Leu-333.

The similarities between the L37P and L333P mutant proteins in the ability to support activator-independent transcription (Fig. 3) and the reduced affinity for fork junction DNA (18) prompted us to examine conserved residues in the vicinity of Leu-333. Leu-333 lies within a well-conserved region of ς54 that was shown previously to be cross-linked to DNA upon UV irradiation of ς54-promoter complexes (5). It is also close to a putative helix-turn-helix motif that has been implicated in recognition of the −12 region of the promoter (12, 23). When we compared the sequences of this portion of ς54 proteins from 25 different bacteria, we noted that it was similar to a motif from single-stranded DNA-binding proteins (Fig. 4A). This motif from single-stranded DNA-binding proteins, (R/K)-N4-5-(K/R)-N4-6-(Y/F)-N5-8-(Y/F/N)-N6-9-(Y/C)-N9-(E/D)-N7-9-(Y/W)-N4-8-(Y/F/E)-N11-12-(R/K), is thought to stabilize the binding of single-stranded DNA by stacking interactions between aromatic residues and bases and electrostatic interactions between basic residues and phosphate groups of single-stranded DNA (25).

FIG. 4.

Alanine scanning mutagenesis of conserved residues near Leu-333. (A) Amino acid sequence of the ς54 protein from S. enterica serovar Typhimurium near Leu-333. The PILEUP program was used to compare sequences around Leu-333 from ς54 proteins from 25 bacteria. The sequence shown spans residues 328 to 404. Leu-333 is marked with a dot over the sequence. Boldface letters indicate residues that are identical in at least 22 of the 25 ς54 protein sequences, and italic letters indicate residues that are similar in at least 22 of the ς54 protein sequences. Arrows indicate the residues where alanine substitutions were introduced. The stars indicate residues that align with the single-stranded DNA-binding motif, which is indicated on the bottom line. The sequence that is cross-linked to promoter DNA upon UV irradiation (5) is indicated, as is a putative helix-turn-helix motif that appears to be involved in DNA binding (23). (B) Glutamine synthetase activities observed with ς54 mutant proteins. Cells were grown in a modified E medium that lacked sodium ammonium phosphate and was supplemented with acid-hydrolyzed Casamino Acids at 1 mg/liter as described previously (18). Glutamine synthetase activities of strains that express the alanine substitution ς54 mutant proteins were carried out using the γ-glutamyl transferase assay as described previously (18). Glutamine synthetase activities were expressed as micromoles of γ-glutamyl hydroxymate per minute per milligram of protein, and all assays were done at least twice. Error bars show one standard deviation for each data set. The wild-type and mutant ntrA alleles, which were carried on plasmids, were under the control of the E. coli lac promoter-operator and were overexpressed by including 100 μM isopropyl-β-thiogalactopyranoside in the growth medium. The no-protein designation indicates the glutamine synthetase activity from S. enterica serovar Typhimurium strain TRH134 without a plasmid-borne ntrA allele. (C) Repression of ant′-′lacZ reporter gene in S. enterica serovar Typhimurium strain TRH107 by ς54 proteins. β-Galactosidase assays were done in triplicate with strain TRH107, carrying plasmids that encode the ς54 proteins indicated, as described previously (1, 18). Error bars show one standard deviation for each data set. The no-protein control shows the activity for strain TRH107 with no plasmid-borne ntrA allele.

We introduced alanine substitutions at five conserved positions near Leu-333 by site-directed mutagenesis as described previously (18). Substitutions were introduced at Trp-328, Lys-331, Arg-336, Arg-342, and Gln-351. Two of these residues, Arg-336 and Arg-342, are located within the region of the protein that can be cross-linked to promoter DNA and are also part of the sequence that resembles the single-stranded DNA-binding motif. Gln-351 occurred in all 25 of the ς54 protein sequences that we compared, while Trp-328 occurred in 20 of these sequences and lysine or arginine occurred at position 331 in 20 of these sequences. During the course of our experiments, Chaney and Buck (11) introduced alanine substitutions at Trp-328, Arg-336, and Arg-342 in Klebsiella pneumoniae ς54 and reported that the R336A mutation allowed activator-independent transcription.

The alanine substitution mutant proteins that we generated were overexpressed at comparable levels, and each conferred glutamine prototrophy on an S. enterica serovar Typhimurium strain that lacked ς54 (strain TRH134), indicating that these mutant forms of ς54 could function with NtrC at glnAp2 (data not shown). Glutamine prototrophy is not a quantitative indicator of the functionality of ς54 mutant proteins, so we examined the abilities of these mutant proteins to initiate transcription from glnAp2 by measuring glutamine synthetase activities. Strains expressing the alanine substitution mutant proteins had glutamine synthetase activities that were comparable to that of a strain that expresses wild-type ς54 (Fig. 4B).

We also assessed the DNA-binding activities of the alanine substitution mutant proteins by examining their abilities to repress the transcription of an ant′-′lacZ reporter gene in vivo. For these assays, we used an S. enterica serovar Typhimurium strain (TRH107) that contained a partially deleted P22 prophage bearing an ant′-′lacZ reporter gene in which the S. meliloti nifH promoter overlapped the ant promoter (1). Binding of the ς54-holoenzyme to the nifH promoter in the prophage represses transcription from the ant′-′lacZ reporter gene (1, 18). Overexpression of wild-type ς54 repressed transcription from the ant′-′lacZ reporter gene about sevenfold (Fig. 4C). With the exception of R336A, the mutant ς54 proteins repressed transcription from the ant′-′lacZ reporter gene as well as or better than wild-type ς54. Interestingly, the R336A mutant protein, which functioned as well as wild-type ς54 from glnAp2, only repressed transcription from the ant′-′lacZ reporter by ∼25%, suggesting that the R336A-holoenzyme had reduced affinity for promoter sequences. Chaney and Buck (11) similarly observed that the K. pneumoniae ς54 R336A mutant protein had reduced affinity for the nifH promoter but supported ∼70% of the level of expression from a glnAp2-lacZ reporter gene that was achieved with wild-type ς54. Arg-336 is in a region of the protein that can be cross-linked to DNA following UV irradiation of ς54-promoter complexes (5), and it has been proposed that Arg-336 participates in a ς54-DNA interaction that helps keep the closed complex from undergoing isomerization in the absence of enhancer-binding protein (11).

Conclusions.

Region I of ς54 functions as an intramolecular inhibitor that prevents isomerization of the closed complex to the open complex, but it also has a role in DNA melting in response to the enhancer-binding protein (6, 13, 29). Two of the mutants that were analyzed here, L37P and L46P, had single amino acid substitutions in region I and allowed activator-independent transcription from the heteroduplex template, indicating that these amino acid substitutions disrupt the inhibitory effect of region I on the holoenzyme. Leu-37 is within a small leucine-rich patch, residues Leu-25 through Leu-37, that was shown previously to be important for mediation of the inhibitory effect of region I on the holoenzyme (10, 26, 30). Substitution of arginine for Leu-37 in E. coli ς54 was shown previously to allow activator-independent transcription. The L37R mutant protein, however, remained responsive to enhancer-binding protein in vitro, allowing NtrC-mediated activation to about 50% of the level observed with wild-type ς54 (26). The L37P mutant protein described in this study appeared to be more severely impaired in the ability to respond to enhancer-binding protein, which likely reflects disruption of secondary structure in the protein by the proline substitution. Casaz and coworkers identified two other areas within region I, residues 15 to 17 and 42 to 47, that are important for inhibition of the conformational change in the holoenzyme and responsiveness to the activator (10). Consistent with these previous results, the L46P mutant enzyme was capable of activator-independent transcription from the heteroduplex template and also appeared to be impaired in the ability to respond to enhancer-binding protein, but not as severely as the L37P mutant protein.

Not all of the mutant ς54 proteins with amino acid substitutions in region I that we used in our study were capable of activator-independent transcription, as the E32K G189V double-mutant protein failed to activate transcription from the heteroduplex template. Since both substitutions in this double-mutant protein are needed for loss of function (18), we cannot rule out the possibility that the substitution of valine for Gly-189 interfered with the ability of the protein to initiate transcription from the heteroduplex template.

Holoenzymes formed with L37P or L333P were capable of efficient activator-independent transcription from the heteroduplex template (Fig. 3) and also had diminished fork junction DNA-binding activities (18). These observations suggest that these two ς54 mutant proteins stabilize the same conformation of holoenzyme, indicating that region I may function together with a sequence around Leu-333 in region III to prevent isomerization of the closed complex in the absence of enhancer-binding protein. We identified here a second sequence within region III that also appears to be important in keeping holoenzyme locked in the closed complex conformation prior to activation. Like the L333P mutant protein, the L124P V148A mutant protein allowed activator-independent transcription from the heteroduplex DNA template (Fig. 3). Unlike the L333P mutant protein, the L124P V148A mutant protein retained fork junction DNA-binding activity (18), suggesting that the L124P V148 mutant protein stabilizes a conformation of the holoenzyme that differs from that of the L333P-holoenzyme. Leu-124 and Val-148 lie within the minimal core-binding domain of ς54, which spans residues 120 to 215, and Leu-124 is also located in a portion of the protein that is protected from hydroxyl radical cleavage by core RNA polymerase (9). It is possible that the sequence around Leu-124 interacts directly with core RNA polymerase to prevent isomerization of the closed complex prior to activation.

The remaining mutant forms of ς54 examined here, L179P, E32K G189V, and L199P D231G, did not allow efficient activator-independent transcription from the heteroduplex DNA template. Gel mobility shift assays showed that these mutant forms of ς54 retained core RNA polymerase and fork junction DNA-binding activities (18; Fig. 1). Taken together, these findings indicate that these mutant forms of ς54 represent a different class of mutant proteins. While both amino acid substitutions were required for loss of function in the two double-mutant proteins (18), all of these mutant proteins had an amino acid substitution within a well-conserved 20-amino-acid segment (Leu-179 to Leu-199) in the core-binding domain of ς54. It is possible that this segment of ς54 participates in some function in transcription initiation following formation of the closed complex, such as mediation of signal transduction from the enhancer-binding protein.

Acknowledgments

We thank Frank Gherardini and John Olson for helpful comments on the manuscript and Sydney Kustu for providing the NtrC and NtrB proteins. We also thank Paula Buice for her assistance in isolating the L179P mutant protein.

This work was supported by award MCB-9974558 to T.R.H. from the National Science Foundation.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ashraf S I, Kelly M T, Wang Y-K, Hoover T R. Genetic analysis of the Rhizobium meliloti nifH promoter, using the P22 challenge phage system. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:2356–2362. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.7.2356-2362.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Backman K C, Chen Y-M, Magasanik B. Physical and genetic characterization of the glnA-glnG region of the Escherichia coli chromosome. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1981;78:3743–3747. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.6.3743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Buck M, Gallegos M-T, Studholme D J, Guo Y, Gralla J D. The bacterial enhancer-dependent ς54 (ςN) transcription factor. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:4129–4136. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.15.4129-4136.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cannon W, Chaney M, Buck M. Characterization of holoenzyme lacking ςN regions I and II. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27:2478–2486. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.12.2478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cannon W, Claverie-Martin F, Austin S, Buck M. Identification of a DNA-contacting surface in the transcription factor sigma-54. Mol Microbiol. 1994;11:227–236. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb00303.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cannon W, Gallegos M-T, Casaz P, Buck M. Amino-terminal sequences of ςN (ς54) inhibit RNA polymerase isomerization. Genes Dev. 1999;13:357–370. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.3.357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cannon W, Missailidis S, Smith C, Cottier A, Austin S, Moore M, Buck M. Core RNA polymerase and promoter DNA interactions of purified domains of ςN: bipartite functions. J Mol Biol. 1995;248:781–803. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1995.0260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cannon W V, Gallegos M-T, Buck M. Isomerization of a binary sigma-promoter DNA complex by transcription activators. Nat Struct Biol. 2000;7:594–601. doi: 10.1038/76830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Casaz P, Buck M. Region I modifies DNA-binding domain conformation of sigma 54 within the holoenzyme. J Mol Biol. 1999;285:507–514. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.2328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Casaz P, Gallegos M-T, Buck M. Systematic analysis of ς54 N-terminal sequences identifies regions involved in positive and negative regulation of transcription. J Mol Biol. 1999;292:229–239. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.3076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chaney M, Buck M. The sigma54 DNA-binding domain includes a determinant of enhancer responsiveness. Mol Microbiol. 1999;33:1200–1209. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01566.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Coppard J R, Merrick M J. Cassette mutagenesis implicates a helix-turn-helix motif in promoter recognition by the novel RNA polymerase sigma factor ς54. Mol Microbiol. 1991;5:1309–1317. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1991.tb00777.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gallegos M-T, Buck M. Sequences in ςN determining holoenzyme formation and properties. J Mol Biol. 1999;288:539–553. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.2704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gallegos M-T, Cannon W V, Buck M. Functions of the ς54 region I in trans and implication for transcription activation. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:25285–25290. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.36.25285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guo Y, Gralla J D. Promoter opening via a DNA fork junction binding activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:11655–11660. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.20.11655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hsieh M, Gralla J D. Analysis of the N-terminal leucine heptad and hexad repeats of sigma 54. J Mol Biol. 1994;239:15–24. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1994.1347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hsieh M, Tintut Y, Gralla J D. Functional roles for the glutamines within the glutamine-rich region of the transcription factor ς54. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:373–378. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kelly M T, Hoover T R. Mutant forms of Salmonella typhimurium ς54 defective in initiation but not promoter binding activity. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:3351–3357. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.11.3351-3357.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ledebur H, Nixon B T. Tandem DctD-binding sites of the Rhizobium meliloti dctA upstream activating sequence are essential for optimal function despite a 50- to 100-fold difference in affinity for DctD. Mol Microbiol. 1992;6:3479–3492. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1992.tb01783.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee J H, Hoover T R. Protein crosslinking studies suggest that Rhizobium meliloti C4-dicarboxylic acid transport protein D, a ς54-dependent transcriptional activator, interacts with ς54 and the β subunit of RNA polymerase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:9702–9706. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.21.9702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee J H, Scholl D, Nixon B T, Hoover T R. Constitutive ATP hydrolysis and transcriptional activation by a stable, truncated form of Rhizobium meliloti DCTD, a ς54-dependent transcriptional activator. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:20401–20409. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lonetto M, Gribskov M, Gross C A. The ς70 family: sequence conservation and evolutionary relationships. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:3843–3849. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.12.3843-3849.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Merrick M, Chambers S. The helix-turn-helix motif of ς54 is involved in recognition of the −13 promoter region. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:7221–7226. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.22.7221-7226.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Porter S C, North A K, Wedel A B, Kustu S. Oligomerization of NTRC at the glnA enhancer is required for transcriptional activation. Genes Dev. 1993;7:2258–2272. doi: 10.1101/gad.7.11.2258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Prasad B V V, Chiu P W. Sequence comparison of single-stranded DNA binding proteins and its structural implications. J Mol Biol. 1987;193:579–584. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(87)90268-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Syed A, Gralla J. Identification of an N-terminal region of sigma 54 required for enhancer responsiveness. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:5619–5625. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.21.5619-5625.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Taylor M, Butler R, Chambers S, Casimiro M, Badii F, Merrick M. The RpoN-box motif of the RNA polymerase sigma factor ςN plays a role in promoter recognition. Mol Microbiol. 1996;22:1045–1054. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.01547.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tintut Y, Gralla J D. PCR mutagenesis identifies a polymerase binding sequence of sigma 54 that includes a sigma 70 homology region. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:5818–5825. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.20.5818-5825.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang J T, Syed A, Gralla J D. Multiple pathways to bypass the enhancer requirement of sigma 54 RNA polymerase: roles for DNA and protein determinants. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:9538–9543. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.18.9538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang J T, Syed A, Hsieh M, Gralla J D. Converting Escherichia coli RNA polymerase into an enhancer-responsive enzyme: role of an NH2-terminal leucine patch in ς54. Science. 1995;270:992–994. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5238.992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang Y-K, Lee J H, Brewer J M, Hoover T R. A conserved region in the ς54-dependent activator DctD is involved in both binding to RNA polymerase and coupling ATP hydrolysis to activation. Mol Microbiol. 1997;26:373–386. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.5851955.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wong C, Gralla J D. A role for the acidic trimer repeat region of transcription factor ς54 in setting the rate and temperature dependence of promoter melting in vivo. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:24762–24768. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wong C, Tintut Y, Gralla J D. The domain structure of sigma 54 as determined by analysis of a set of deletion mutants. J Mol Biol. 1994;236:81–90. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1994.1120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]