Abstract

Biofilm producers pose a major challenge in treating implant-related orthopedic infections (IROIs). The incidence of IROIs for the closed fracture amounts to 1% to 2% whereas for open fracture it is up to 30%. Due to inappropriate and irrational use of antibiotics in the management of infections, there is an emergence of a global “antimicrobial resistance crisis”. To combat these antimicrobial resistance crises, a few innovative and targeted therapies like nanomedicine, phage therapy, antimicrobial peptides, and sonic therapies have been introduced. In this review, we have detailed the basic mechanisms involved in the employment of bacteriophage therapy for IROIs, along with the preclinical and clinical data on its utility. We also present the guidelines on its regulation, processing, and limitations of bacteriophage therpay to combat the upcoming era of antibiotic resistance.

Keywords: Antimicrobial resistance, Bacteriophage, Biofilm

Introduction

Implant-related orthopedic infections (IROIs) pose a major challenge for treating orthopedic surgeons and clinical microbiologists. The success rate of management of infection after fracture fixation is only between 70 and 90%. The literature records the incidence of such infection after fracture fixation for the closed fracture to 1% to 2%, whereas for open fracture it is up to 30% [1]. IROIs are due to the formation of biofilms that are composed of bacterial populations encapsulated in a heterogeneous extracellular matrix which provide a resistant environment for the antimicrobial agent to reach the target organisms [2, 3]. Biofilm leads to an increase in minimum inhibitory concentration up to 1000-fold to control the infection due to the decreased metabolism of bacteria and their quorum sensing properties that led to the enhancement of antibiotic resistance gene exchange between bacterial cells [4, 5]. Due to inappropriate and irrational use of antibiotics in the management of infections, there is an emergence of a global “antimicrobial resistance crisis” [6–8]. In 2016, Review on Antimicrobial Resistance by UK government, it was estimated 7 lakhs population die every year worldwide from multi-drug resistant infections and a death toll of 10 million population by 2050 [9].

The major IROIs are due to S. aureus (33% to 43%), S. epidermidis (18% to 40%), Enterococcus faecalis (2.5% to 15%), and gram negative bacilli like E. coli and P. aeruginosa (4% to 7%) [10, 11]. IORIs play major morbidity for the patients’ quality of life and the health care systems and pose a global threat of ‘antimicrobial resistance’ [12, 13]. The increased rate of antimicrobial resistance has been observed with S. aureus and S. epidermidis [14, 15]. In recent years, the incidence of MRSA has drastically reduced which has now led to increased antimicrobial resistance among gram-negative bacilli species such as Enterobacter, Acinetobacter, Klebsiella, and Pseudomonas [14, 16–18]. To combat these antimicrobial resistance crises, a few innovative and targeted therapies like nanomedicine, phage therapy, antimicrobial peptides, and sonic therapies have been introduced. This review on bacteriophage therapy for implant-related orthopedic infections was conducted from relevant literature search from databases such as PubMed and Web of Sciece using generic keywords such as “Bateriophage” and “Infection”. The results were scrutinised for relevance to the subject by two authors and shortlisted for compilation as shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram of selction of studies for the review

Bacteriophage Therapy

Bacteriophages are bacteria-specific viruses that are used against treating specific bacteria. Phages possess the properties of host-specificity, self-amplification, narrow spectrum of activity, degradation of biofilm, high safety and tolerability, and pose a least or no toxic effect to humans. They are versatile and found in soil, marine water, and terrestrial surfaces. An estimated phage count of 1031–1032 phages in the world at any given time, represents the abundant biological entity that plays a significant role in the regulation of the bacterial population in the world [19]. Phages replicate by lytic (virulent phages) and lysogenic (temperate phages) cycle by integrating its genome with host’s genome and releases the newly formed phage particles [20, 21] and hence they become a potent antimicrobial agent against multi-drug resistant infections.

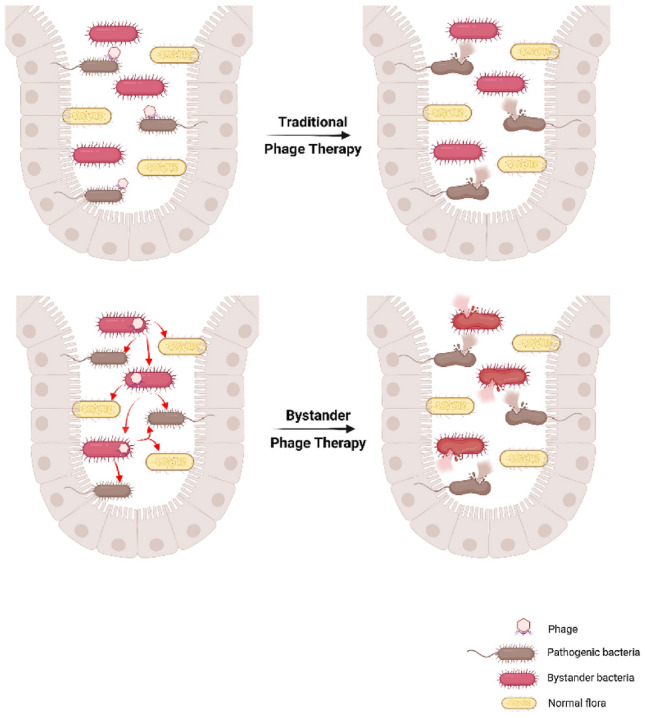

Due to the narrow zone of activity, bacteriophages recognize only the specific agents and degrade the specific microbiome and control the emergence of bacterial resistance [22–24]. These bacteriophages do not disturb the hosts’ gut microbiota. Apart from the traditional phage therapy, other modalities of phage therapy such as bystander phage therapy [25], where the phages use the bystander bacteria mediated killing of the pathogenic bacteria through the release of bacterial toxins, are being tried to eliminate the pathogenic bacterial flora without much impact on the native bacteria flora as shown in Fig. 2. Along with phages, the combination of phage bacterial lysine enzymes and appropriate antibiotics may help in treating implant-related orthopaedic infections.

Fig. 2.

Mechanism of action of the traditional and bystander phage therapy against pathogenic bacteria

Pharmacokinetics

Bacteriophages are thermostable which can be stored in extremes of temperatures. They are preserved by freeze-drying, spray drying, or encapsulation [26]. The stability of phages is achieved once when the phage titers are not significantly decreased. The administration of phages for infection is of prime importance. Oral phage therapy results in failed clinical outcomes due to neutralization and disintegration of phages by the acidic environment in the stomach. The pharmacokinetics of phages differ greatly from antibiotics in terms of tissue uptake and diffusion. Phages are composed of agglomerated proteins whereas antibiotics are small molecules. Due to this low mobility of phages, the local delivery (intramuscular, intravenous, or intraperitoneal) is plausible at the site of infection [26]. The ideal phage delivery systems must possess biomaterials (natural or synthetic biopolymers, ceramics), biomaterial constructs (hydrogel, particles, macro-sized constructs, and lipid carriers), and mode of phage incorporation (embedding, encapsulation, and surface adsorption) [27]. The therapeutic phages should be lytic and hence those phages must be screened for lysogeny and antibiotic resistance genes [22, 28].

Methods and Mechanisms of Phage Therapy

Multiple phage cocktails provide synergy in the form of wide-spectrum activity against microbes. Such multiple phage cocktails eradicate the infections more readily than single phage regimens [29]. This synergistic activity of multiple phage cocktails improves the clinical efficacy in eradicating infections. The concept of “multiplicity of infection” has to be investigated in terms of the ratio of phages per bacterium, when therapeutic phages are selected [30]. Another factor in phage therapy is the killing titer which is defined as the number of bactericidal phages administered [31]. Phage therapy is advocated in the scenario where continuous treatments are required to eliminate the microbe as phage continuously replicates at the site of infection. The various modalities employed in the administration of the phage therapy against IROIs include using phage cocktails, phage enzymes, phage antibiotic synergy, phage CRISPR therapy, and phage engineering as shown in Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Various modalities of administration of the phage therapy against IROIs

The understanding of phage–antibiotic synergy (PAS) is crucial in the usage of bacteriophage therapy in eradicating osteoarticular infections [32]. Various studies have shown PAS reduces the development of multi-drug resistant organisms by bactericidal mechanisms. The proteolytic enzymes of bacteriophages destroy the polysaccharides present in the biofilms [2, 3]. Phages possess anti-biofilm properties and hence it is used in IROIs.

Pre-clinical and In-Vitro Evidence

The prophylactic administration of phages of virulent bacterial strains reduces the bacterial load and acts as definitive therapy in immunocompromised patients undergoing bone marrow transplant procedures [33, 34]. Scaffold based delivery of phages helps in eradicating the multidrug-resistant (MDR) osteoarticular infections [35, 36]. The evidence of results of using phage therapy in the preclinical and in-vitro models were listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Evidence of preclinical and in-vitro studies of phage therapy in osteoarticular infections

| Author (year) | Model | Infection | Phage used | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preclinical studies | ||||

| Zimecki et al. [33] (2009) | Immunosuppressed mice infected with S. aureus | S. aureus infected mice | Virulent S. aureus A5/L | Prophylactic administration of phages reduces the bacterial load |

| Zimecki et al. [34] (2010) | Immunosuppressed mice treated with syngeneic bone marrow transplant and infected with S. aureus | S. aureus infected mice | Virulent S. aureus A5/L | Bacteriophage therapy helps in immunocompromised patients subjected to bone marrow transplant procedures |

| Yilmaz et al. [37] (2013) | IV catheter with a pre-established biofilm into rat tibial medullary canal | MRSA and P. aeruginosa infected rats | MRSA—Sb-1 P. aeruginosa—PAT14 | The addition of bacteriophage along with an appropriate antibiotic regimen leads to better eradication of MRSA than P. aeruginosa |

| Kaur et al. [38] (2016) | Naked wire, hydroxypropyl methylcellulose coated wire, and phage + linezolid coated K-wire into mouse femoral medullary canal | MRSA infected mouse | S. aureus specific bacteriophage, MR-5 | Dual-coated implants with phage and linezolid offer a better approach to curb MRSA in a murine model |

| Kishore et al. [39] (2016) | Distal femoral osteomyelitis in a rabbit model | MRSA infected rabbits | SA-BHU1, SA-BHU2, SA-BHU8, SA-BHU15 and SA-BHU21, SA-BHU37, SA-BHU47 | Phage therapy has the potential to manage infections caused by MDR organisms |

| Wroe et al. [36] (2020) | Radial segmental defect loaded with P. aeruginosa phage admixed with hydrogel in mouse | P. aeruginosa infected mouse | ΦPaer4, ΦPaer14, ΦPaer22, ΦW2005A | Results support scaffold-based phage delivery to treat local osteoarticular infections |

| In-vitro studies | ||||

| Meurice et al. [40] (2012) | Phage loaded HA and β-TCP | E. coli | λ vir phage | Phage loaded ceramics can be used as a prophylactic measure |

| Kaur et al. [41] (2014) | Preformed S. aureus biofilm on K wires coated with HPMC + phage, linezolid alone, and phage + linezolid | MRSA | S. aureus specific bacteriophage, MR-5 | Delivery of lytic bacteriophage with broad-spectrum bactericidal antibiotic curbs IROIs |

| Morris et al. [35] (2019) | S. aureus on porous titanium | S. aureus | StaPhage cocktail | Combination of StaPhage on porous titanium eradicates periprosthetic joint infections |

| Kolenda et al. [42] (2020) | Model of S. aureus biofilm and a model of osteoblasts infection, alone or in association with vancomycin or rifampin | S. aureus | PP1493, PP1815, and PP1957 | Phage combinations were active against the S.aureus biofilm model whereas no activity against intracellular bacteria in the infected osteoblast model |

Clinical Evidence

Barros et al. reported lytic phages against MDR S. aureus, E. faecalis, and E. coli from implant-associated osteoarticular infections [43]. These phages demonstrate higher efficacy towards MRSA and VRE [43]. In the osteoarticular system, phages are used to treat diabetic toe ulcers with exposure of bone [44], osteomyelitis [45, 46], periprosthetic joint infections [47, 48], postoperative infection [49], and the infection of complex fractures [50, 51]. The evidence of results of using phage therapy in osteoarticular infections are listed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Evidence of clinical studies of phage therapy in osteoarticular infections

| Author (year) | Model | Bacteria | Phage used | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fish et al. [44] (2016) | Diabetic toe ulcers (n = 6) | S. aureus | Staphylococcal phage Sb-1 | Despite the antibiotic failure, topical Sb-1 phage curbs off diabetic toe ulcers |

| Fish et al. [52] (2018) | Staphylococcal osteomyelitis (n = 1) | S. aureus | Staphylococcal phage Sb-1 | Phage therapy treatment offers the potential for improved outcomes in this era of escalating antibiotic resistance |

| Ferry et al. [45] (2018) | Right sacro-iliac joint osteomyelitis (n = 1) | Extremely drug resistant (XDR) P. aeruginosa | Phage cocktail (1450, 1777, 1792 and 1797) | Eradication of XDR-P. aeruginosa within 14 days |

| Ferry et al. [47] (2018) | Periprosthetic joint infection of right hip (n = 1) | Methicillin-sensitive S. aureus | Phage cocktail (1493, 1815, and 1957) | Phage act as antibiofilm producer in relapsing S. aureus periprosthetic joint infection |

| Onsea et al. [46] (2019) | Osteomyelitis of pelvis and femur (n = 4) |

S. aureus S. epidermidis S. agalactiae E. faecalis P. aeruginosa |

Staph species and P. aeruginosa—BFC1; E.faecalis—Pyo | A single course of phage therapy prevents recurrence of infection ranging from 8 to 16 months |

| LaVergne et al. [49] (2019) | Postoperative infection followed by traumatic brain injury and craniotomy (n = 1) | MDR A. baumannii | 104 A. baumanii bacteriophages from the NMRC’s phage-Biolog system | Absence of infection in the craniotomy site |

| Patey et al. [50] (2019) | Pelvic bone infection (n = 1) | S. aureus; P. aeruginosa | Anti S. aureus and anti-P. aeruginosa suspension | Complete resolution of infection in 24 months |

| Complex fracture of right foot (n = 1) | S. aureus | Anti S. aureus suspension | Clearance of infection within 6 months | |

| Mandibular fracture, osteosynthesis, and fistulised infection (n = 1) | MRSA | Tbilisi phage therapy and anti S.aureus suspension | Clearance of infection within 6 months | |

| Femoral fracture under hip prosthesis (n = 1) | MRSA | Anti S. aureus suspension | Clearance of MRSA infection within 12 months | |

| Left knee prosthesis infection (n = 1) | P. aeruginosa | Phage cocktail | Clearance of P.aeruginosa infection within 2 years | |

| Osteomyelitis of the left tibia (n = 1) | MRSA | Anti S.aureus suspension | Clearance of infection within 6 months | |

| Left tibia fracture, followed by reopened bone infection (n = 1) | S. aureus | Anti S. aureus suspension | Clearance of S.aureus infection within 12 months | |

| Nir-Paz et al. [51] (2019) | Left bicondylar tibial plateau fracture (n = 1) | A.baumannii; K. pneumoniae | Combination of ɸAbKT21phi3 and ɸKpKT21phi1 | Tissue healing along with negative bacterial culture observed at the end of the 8th-month follow-up |

| Tkhilaishvili et al. [48] (2019) | Right knee periprosthetic infection and chronic osteomyelitis of the femur (n = 1) | MDR P. aeruginosa | P. aeruginosa specific phage cocktail | Phage act as an adjuvant to antimicrobial in curbing MDR P. aeruginosa infection |

Processing in Bacteriophage Therapy

The processing methods involved in bacteriophage therapy denote the essential steps in the production of a phage therapeutic medicinal product (PTMP) with sufficient quality. The first and foremost step in the processing of bacteriophage therapy involves the ‘upstream processes’ that involve regulation of various culturing parameters such as bacterial density, the multiplicity of infection, culture medium, duration, temperature, and supplements needed for appropriate culture conditions. Following the optimization of the propagation conditions, the next objective is to streamline the purification process with ‘downstream processes’ that involve filtration and purification of the harvest as shown in Fig. 4. Following a successful manufacturing process, the product is stored with assured identity, purity, and quality by quality control measures to serve as PTMP. Various critical quality attributes in various stages of the process are ensured with appropriate quality control assays.

Fig. 4.

Stages of processing of phage therapeutic medicinal product from the raw materials to the final product. QC, quality control

Regulations in Bacteriophage Therapy

The regulation of phages in clinical practice is a complication as they are neither categorized as chemical nor living organisms. The therapeutic phage formulation is defined as industrially or pharmaceutically prepared medicinal products. Phage preparations are regulated according to European Directive requirements for medicinal products for human use. Bacteriophage cocktails have to be regulated for personalized therapy based on the Quality by Design concept in a risk-based manner. United States – Food & Drug Administration (US-FDA) authority approved phage therapy via the “Emergency Investigational New Drug Scheme” through the Centre for Innovative Phage Applications and Therapeutics (IPATH). Despite the approval of phage therapy through IPATH, utilization of such therapeutics in common clinical practise has not yet been established and its current use is only for research purposes to better understand and address the lacunae in the application of this therapy for routine clinical practise. Currently no approval has been obtained in India for its common clinical practise.

Having designated as a therapeutic medicinal product, health agencies require the product to follow sequential evaluation through clinical trials before market authorization and manufacturing processes in compliance with good manufacturing practice (GMP). In the case of genetically modified phages (GMPs), some additional requirements such as environmental risk assessment need to be analyzed before clinical use. These products are considered advanced therapeutic medicinal product (ATMP) by the European Medical Agency and needs a centralized authorization procedure. In the US market, the product is under the supervision of the Office of Vaccines Research and Review. GMPs are under the supervision of the Office of the Tissue and Advanced Therapies. These offices come under the Centre of Biologics Evaluation and Research of FDA. Despite the constraints with the development of GMPs, its ardent manufacturing is mostly due to the properties such as increased potency compared to the wild-type phages and industrial intellectual patenting potential concerning its design with innovative properties.

Limitations of Bacteriophage Therapy

The potential limitation of bacteriophage therapies are (a) absence of specific activity for a particular bacterial strain, (b) plausible emergence of bacterial resistance against bacteriophages, (c) decreased activity due to immunological response against bacteriophages, and (d) technical difficulties in pharmaceutical preparation of bacteriophages. In a clinical scenario, the prior identification of bacterial strain is important to expedite the initiation of phage therapy (ex. in case of sepsis). Another limitation of phage therapy is the duration of phage activity in vivo. To prolong the activity of phages for a sustained bactericidal effect, phages are mixed with biomaterials or biodegradable scaffolds and implanted at the site of infection. This opens a vision for phage engineering in the future. Further studies are needed on the immunological response to the phage therapy and the fate of the vriuses following successful elimination of infection. There is a need to understand their effect on special circumstances specially in immunocompromised hosts for the theoretical possibility of phage-induced deliterious effects in the host.

To validate these ATMPs, technologies such as next-generation sequencing have emerged as a powerful tool to analyze the phage and bacteria utilized, however, it could not be implemented as a GMP-compliant assay due to the lack of a strong validation framework that needs to be developed. In practice, it is key to have personnel adequately trained in upstream/downstream processing and guidelines of GMP manufacturing and quality control measures of the medicinal product to ensure quality at every level of processing of the product.

Future of Bacteriophage Therapy

The future relies on bacteriophage therapy for eradicating MDR organisms, especially in IROIs. The development of various phage cocktails to eradicate MDR organisms is the prime area for further research in orthopedics. Due to the lack of preclinical and clinical evidence, further research on bacteriophage therapy is warranted. To overcome the emergence of phage resistance, phage engineering is being developed to make genetically engineered bacteriophages that are less immunogenic, target-specific with CRISPR repeats to eradicate the infection. The ideal phage release kinetics with phage-specific and patient-specific phages must be developed for the future. To prolong the shelf life of phages, lyophilization with cryoprotectant technology has been introduced which prevents the phage disintegration by freezing process. With the lyophilized freeze-dried phage-loaded biomaterial construct, long-term storage capacity and phage stability can be produced. In future, following its successful application in IROI, the same methodology could be extrapolated to the eradication of other challenging infections such as MDR Tuberculosis.

Conclusion

We note the re-emergence of phage therapy as a promising strategy to combat IROIs with antibiotic resistance. Being a high-precision targeted therapy without the side effects of the traditional wide spectrum antibiotics such as collateral damage on non-pathogenic bacterial flora, phage therapy has attracted a lot of attention with encouraging preclinical and clinical evidence. This supporting evidence is of great value in re-opening the therapeutic field to combat antibiotic resistance that poses an imminent threat to humanity. Given the relevance to large-scale production, consideration to the implementation of GMP guidelines is a necessity with a need for evolution of the regulatory framework to better handle the potential of the phages leading to the availability of the phage therapeutic medicinal product for clinical use in the near future with assured potency and quality.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors do not have any conflicts of interest to disclose.

Ethical standard

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by the any of the authors.

Informed consent

For this type of study informed consent is not required.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Steinmetz S, Wernly D, Moerenhout K, Trampuz A, Borens O. Infection after fracture fixation. EFORT Open Reviews. 2019;4(7):468–475. doi: 10.1302/2058-5241.4.180093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Limoli, D. H., Jones, C. J., & Wozniak, D. J. (2015). Bacterial extracellular polysaccharides in biofilm formation and function. Microbiology Spectrum,3(3), 3. 10.1128/microbiolspec.MB-0011-2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Singh S, Singh SK, Chowdhury I, Singh R. Understanding the mechanism of bacterial biofilms resistance to antimicrobial agents. The Open Microbiology Journal. 2017;11:53–62. doi: 10.2174/1874285801711010053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sharma D, Misba L, Khan AU. Antibiotics versus biofilm: An emerging battleground in microbial communities. Antimicrobial Resistance & Infection Control. 2019;8(1):76. doi: 10.1186/s13756-019-0533-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lebeaux D, Ghigo JM, Beloin C. Biofilm-related infections: Bridging the gap between clinical management and fundamental aspects of recalcitrance toward antibiotics. Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews. 2014;78(3):510–543. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00013-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ventola CL. The antibiotic resistance crisis. Pharmacy and Therapeutics. 2015;40(4):277–283. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aslam B, Wang W, Arshad MI, et al. Antibiotic resistance: A rundown of a global crisis. Infection and Drug Resistance. 2018;11:1645–1658. doi: 10.2147/IDR.S173867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dominey-Howes D, Bajorek B, Michael C, Betteridge B, Iredell J, Labbate M. Applying the emergency risk management process to tackle the crisis of antibiotic resistance. Frontiers in Microbiology. 2015;6:927. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2015.00927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Laxminarayan R, Duse A, Wattal C, et al. Antibiotic resistance-the need for global solutions. The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 2013;13(12):1057–1098. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(13)70318-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gibb, B. P., & Hadjiargyrou, M. (2021). Bacteriophage therapy for bone and joint infections. The Bone & Joint Journal, 103-B(2), 234–244. 10.1302/0301-620X.103B2.BJJ-2020-0452.R2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Tande AJ, Patel R. Prosthetic joint infection. Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 2014;27(2):302–345. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00111-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li B, Webster TJ. Bacteria antibiotic resistance: New challenges and opportunities for implant-associated orthopedic infections. Journal of Orthopaedic Research. 2018;36(1):22–32. doi: 10.1002/jor.23656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ribeiro M, Monteiro FJ, Ferraz MP. Infection of orthopedic implants with emphasis on bacterial adhesion process and techniques used in studying bacterial-material interactions. Biomatter. 2012;2(4):176–194. doi: 10.4161/biom.22905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fair RJ, Tor Y. Antibiotics and bacterial resistance in the 21st century. Perspectives in Medicinal Chemistry. 2014;6:25–64. doi: 10.4137/PMC.S14459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Otto M. Staphylococcus epidermidis—The “accidental” pathogen. Nature Reviews Microbiology. 2009;7(8):555–567. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mulani MS, Kamble EE, Kumkar SN, Tawre MS, Pardesi KR. Emerging strategies to combat ESKAPE pathogens in the era of antimicrobial resistance: A review. Frontiers in Microbiology. 2019;10:539. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.00539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gandra S, Tseng KK, Arora A, et al. The mortality burden of multidrug-resistant pathogens in India: A retrospective, observational study. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2019;69(4):563–570. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciy955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Karaiskos I, Lagou S, Pontikis K, Rapti V, Poulakou G. The, “Old” and the “New” antibiotics for MDR gram-negative pathogens: For whom, when, and how. Frontiers in Public Health. 2019;7:151. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2019.00151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wittebole X, De Roock S, Opal SM. A historical overview of bacteriophage therapy as an alternative to antibiotics for the treatment of bacterial pathogens. Virulence. 2014;5(1):226–235. doi: 10.4161/viru.25991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Clokie MR, Millard AD, Letarov AV, Heaphy S. Phages in nature. Bacteriophage. 2011;1(1):31–45. doi: 10.4161/bact.1.1.14942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Doss J, Culbertson K, Hahn D, Camacho J, Barekzi N. A review of phage therapy against bacterial pathogens of aquatic and terrestrial organisms. Viruses. 2017;9(3):50. doi: 10.3390/v9030050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lin DM, Koskella B, Lin HC. Phage therapy: An alternative to antibiotics in the age of multi-drug resistance. World Journal of Gastrointestinal Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 2017;8(3):162–173. doi: 10.4292/wjgpt.v8.i3.162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Principi N, Silvestri E, Esposito S. Advantages and limitations of bacteriophages for the treatment of bacterial infections. Frontiers in Pharmacology. 2019;10:513. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2019.00513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Loc-Carrillo C, Abedon ST. Pros and cons of phage therapy. Bacteriophage. 2011;1(2):111–114. doi: 10.4161/bact.1.2.14590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brady TS, Fajardo CP, Merrill BD, et al. Bystander phage therapy: Inducing host-associated bacteria to produce antimicrobial toxins against the pathogen using phages. Antibiotics. 2018;7(4):105. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics7040105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rosner D, Clark J. Formulations for bacteriophage therapy and the potential uses of immobilization. Pharmaceuticals (Basel) 2021;14(4):359. doi: 10.3390/ph14040359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rotman SG, Sumrall E, Ziadlou R, et al. Local bacteriophage delivery for treatment and prevention of bacterial infections. Frontiers in Microbiology. 2020;11:538060. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2020.538060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sulakvelidze A, Alavidze Z, Morris JG. Bacteriophage therapy. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 2001;45(3):649–659. doi: 10.1128/AAC.45.3.649-659.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chan BK, Abedon ST, Loc-Carrillo C. Phage cocktails and the future of phage therapy. Future Microbiology. 2013;8(6):769–783. doi: 10.2217/fmb.13.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hyman P. Phages for phage therapy: Isolation, characterization, and host range breadth. Pharmaceuticals (Basel) 2019;12(1):35. doi: 10.3390/ph12010035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Abedon ST. Phage therapy: Various perspectives on how to improve the art. Methods in Molecular Biology. 2018;1734:113–127. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-7604-1_11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gu Liu, C., Green, S. I., Min, L., et al. Phage-antibiotic synergy is driven by a unique combination of antibacterial mechanism of action and stoichiometry. mBio,11(4), e01462-20. 10.1128/mBio.01462-20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 33.Zimecki M, Artym J, Kocięba M, Weber-Dąbrowska B, Borysowski J, Górski A. Effects of prophylactic administration of bacteriophages to immunosuppressed mice infected with Staphylococcus aureus. BMC Microbiology. 2009;9(1):169. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-9-169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zimecki M, Artym J, Kocieba M, Weber-Dabrowska B, Borysowski J, Górski A. Prophylactic effect of bacteriophages on mice subjected to chemotherapy-induced immunosuppression and bone marrow transplant upon infection with Staphylococcus aureus. Medical Microbiology and Immunology. 2010;199(2):71–79. doi: 10.1007/s00430-009-0135-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Morris J, Kelly N, Elliott L, et al. Evaluation of bacteriophage anti-biofilm activity for potential control of orthopedic implant-related infections caused by Staphylococcus aureus. Surgical Infections (Larchmt) 2019;20(1):16–24. doi: 10.1089/sur.2018.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wroe JA, Johnson CT, García AJ. Bacteriophage delivering hydrogels reduce biofilm formation in vitro and infection in vivo. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research Part A. 2020;108(1):39–49. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.36790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yilmaz C, Colak M, Yilmaz BC, Ersoz G, Kutateladze M, Gozlugol M. Bacteriophage therapy in implant-related infections: An experimental study. Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery American Volume. 2013;95(2):117–125. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.K.01135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kaur, S., Harjai, K., & Chhibber, S. (2016). In vivo assessment of phage and linezolid based implant coatings for treatment of methicillin resistant S. aureus (MRSA) mediated orthopaedic device related infections. PLoS One,11(6), e0157626. 10.1371/journal.pone.0157626 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 39.Kishor C, Mishra RR, Saraf SK, Kumar M, Srivastav AK, Nath G. Phage therapy of staphylococcal chronic osteomyelitis in experimental animal model. Indian Journal of Medical Research. 2016;143(1):87–94. doi: 10.4103/0971-5916.178615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Meurice E, Rguiti E, Brutel A, et al. New antibacterial microporous CaP materials loaded with phages for prophylactic treatment in bone surgery. Journal of Materials Science: Materials in Medicine. 2012;23(10):2445–2452. doi: 10.1007/s10856-012-4711-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kaur S, Harjai K, Chhibber S. Bacteriophage mediated killing of Staphylococcus aureus in vitro on orthopaedic K wires in presence of linezolid prevents implant colonization. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(3):e90411. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0090411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kolenda C, Josse J, Medina M, et al. Evaluation of the activity of a combination of three bacteriophages alone or in association with antibiotics on Staphylococcus aureus embedded in biofilm or internalized in osteoblasts. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 2020;64(3):e02231–e2319. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02231-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Barros J, Melo LDR, Poeta P, et al. Lytic bacteriophages against multidrug-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, Enterococcus faecalis and Escherichia coli isolates from orthopaedic implant-associated infections. International Journal of Antimicrobial Agents. 2019;54(3):329–337. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2019.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fish R, Kutter E, Wheat G, Blasdel B, Kutateladze M, Kuhl S. Bacteriophage treatment of intransigent diabetic toe ulcers: A case series. Journal of Wound Care. 2016;25(Sup7):S27–S33. doi: 10.12968/jowc.2016.25.Sup7.S27. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ferry T, Boucher F, Fevre C, et al. Innovations for the treatment of a complex bone and joint infection due to XDR Pseudomonas aeruginosa including local application of a selected cocktail of bacteriophages. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. 2018;73(10):2901–2903. doi: 10.1093/jac/dky263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Onsea J, Soentjens P, Djebara S, et al. Bacteriophage application for difficult-to-treat musculoskeletal infections: Development of a standardized multidisciplinary treatment protocol. Viruses. 2019;11(10):891. doi: 10.3390/v11100891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ferry, T., Leboucher, G., Fevre, C., et al. (2018). Salvage debridement, antibiotics and implant retention (“DAIR”) with local injection of a selected cocktail of bacteriophages: Is it an option for an elderly patient with relapsing Staphylococcus aureus prosthetic-joint infection? Open Forum Infectious Diseases,5(11), ofy269. 10.1093/ofid/ofy269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 48.Tkhilaishvili T, Winkler T, Müller M, Perka C, Trampuz A. Bacteriophages as adjuvant to antibiotics for the treatment of periprosthetic joint infection caused by multidrug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 2019;64(1):e00924–e1019. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00924-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.LaVergne S, Hamilton T, Biswas B, Kumaraswamy M, Schooley RT, Wooten D. Phage therapy for a multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii craniectomy site infection. Open Forum Infectious Diseases. 2018;5(4):ofy064. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofy064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Patey O, McCallin S, Mazure H, Liddle M, Smithyman A, Dublanchet A. Clinical indications and compassionate use of phage therapy: Personal experience and literature review with a focus on osteoarticular infections. Viruses. 2018;11(1):18. doi: 10.3390/v11010018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nir-Paz R, Gelman D, Khouri A, et al. Successful treatment of antibiotic-resistant, poly-microbial bone infection with bacteriophages and antibiotics combination. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2019;69(11):2015–2018. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciz222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fish R, Kutter E, Bryan D, Wheat G, Kuhl S. Resolving digital Staphylococcal osteomyelitis using bacteriophage—A case report. Antibiotics (Basel). 2018;7(4):87. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics7040087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]