Abstract

A strategy for both cross-electrophile coupling and 1,2-dicarbofunctionalization of olefins has been developed. Carbon-centered radicals are generated from alkyl bromides by merging benzophenone hydrogen atom transfer (HAT) photocatalysis and silyl radical-induced halogen atom transfer (XAT) and are subsequently intercepted by a nickel catalyst to forge the targeted C(sp3)–C(sp2) and C(sp3)–C(sp3) bonds. The mild protocol is fast and scalable using flow technology, displays broad functional group tolerance, and is amenable to a wide variety of medicinally relevant moieties. Mechanistic investigations reveal that the ketone catalyst, upon photoexcitation, is responsible for the direct activation of the silicon-based XAT reagent (HAT-mediated XAT) that furnishes the targeted alkyl radical and is ultimately involved in the turnover of the nickel catalytic cycle.

Keywords: hydrogen atom transfer, halogen atom transfer, photocatalysis, flow chemistry, cross-electrophile coupling

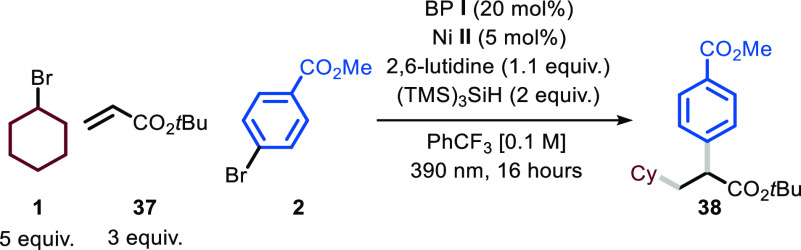

Introduction

Over the past years, organic chemistry has been strongly influenced by the development of metallaphotocatalysis,1 which exploits the synthetic synergy between photocatalysis and transition-metal catalysis. Notably, by taking advantage of the radical-generating properties as well as the ability to modulate the oxidation state of the metal catalyst,2 photocatalysis has greatly expanded our ability to engage various electrophiles and nucleophiles in cross-coupling reactions.

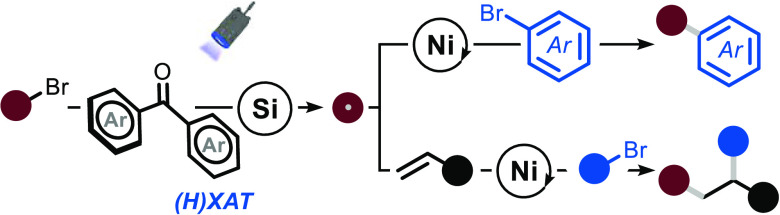

At the inception of this field,3 the photocatalyst was used to activate substrates bearing redox auxiliaries. The presence of such groups would lower the redox potential of the radical precursor, enabling the single electron transfer (SET) from the photocatalyst, and ensure the crucial mesolytic fragmentation to afford the targeted open-shell intermediate (Figure 1a).4 This radical can then be intercepted by a transition-metal catalyst and coupled with suitable aryl electrophiles in an overall C(sp3)–C(sp2) bond formation.5 Pioneering works by MacMillan6a and Martin,6b among others,6 expanded the range of radical precursors to simple alkanes by exploiting the hydrogen atom transfer (HAT)7 abilities of decatungstate8 or benzophenone (BP) photocatalysts.9 The selectivity of such HAT processes depends on the careful balance between electronic and steric properties of the substrates and the reaction conditions.10 In parallel to HAT, halogen atom transfer (XAT)11 has been used in metallaphotoredox manifolds as well,12,13 enabling the use of alkyl halides as radical precursors. This method relies on the photocatalytic generation of silicon-centered12 or α-amino13 radicals, which induce homolytic cleavage of the C–X (X: halogen) bond. The use of this radical tool allows the generation of the open-shell species in a programmable fashion, as the selectivity is now dictated by the position occupied by the halogen atom in the radical precursor.

Figure 1.

(a) Strategies for generating radicals through metallaphotocatalysis. (b) 1,2-Functionalization reactions enabled by SET and HAT methods. (c) Synergistic use of benzophenone photocatalysis, silane-mediated XAT, and nickel catalysis enables various useful coupling reactions. (H)XAT: HAT-induced XAT, HAT: hydrogen atom transfer, XAT: halogen atom transfer, SET: single electron transfer, RA: redox auxiliaries, PC: photocatalyst.

More recently, several groups have focused on expanding metallaphotoredox into a platform that enables the 1,2-functionalization of olefins (Figure 1b).14 Indeed, the addition of the photochemically generated radicals and the aryl electrophiles onto an olefin represents a rapid and direct method to construct complex scaffolds from simple and readily available starting materials.

The groups of Molander,14a Nevado,14b Aggarwal,14c Martin,14d and Yuan14e have disclosed elegant approaches based on the SET of a variety of radical precursors such as trifluoroborates, silicon-based reagents, carboxylates, and tertiary alkyl bromides. Kong14f and Molander14g have employed HAT methods to extend this type of protocol to include alkanes as radical precursors. Nonetheless, strategies relying on XAT mechanisms have not yet been applied to promote a difunctionalization of olefin derivatives.

Herein, we describe the development of a simple and straightforward protocol that exploits the synergistic use of triplet excited diaryl ketone9 and tris(trimethylsilyl)silane radicals to activate alkyl bromides (Figure 1c). This strategy has been shown to be uniquely effective in both nickel-catalyzed reductive cross-coupling15 and nickel-catalyzed 1,2-functionalization reactions16 of olefins. Our mechanistic work reveals that the ketone catalyst, upon photoexcitation, is responsible for the direct activation of the silicon-based XAT reagent (overall an (H)XAT) that furnishes the targeted alkyl radical and is ultimately involved in the turnover of the nickel catalytic cycle.

Results and Discussion

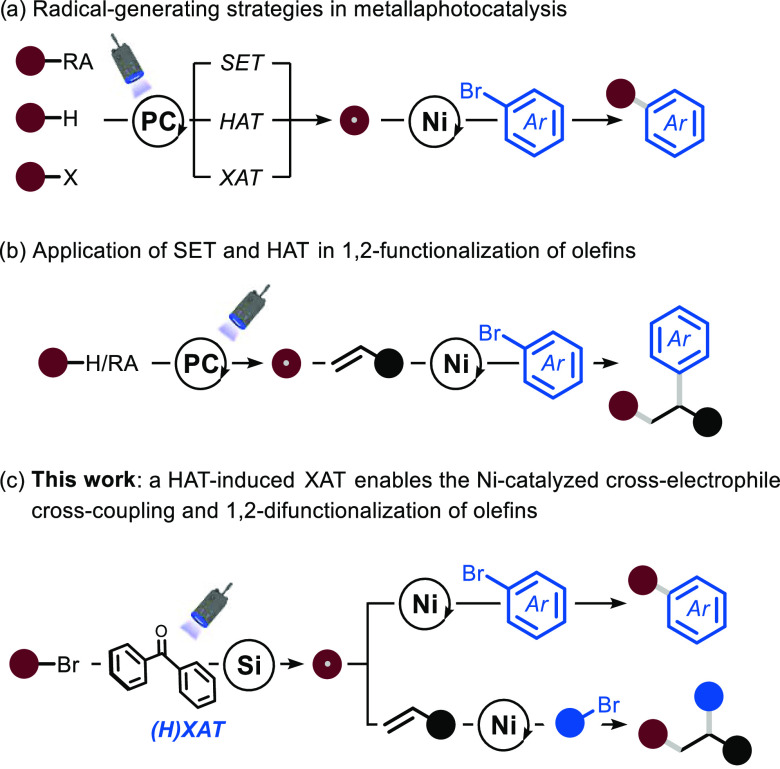

Direct Cross-Electrophile Coupling

At the outset of our investigations, and in view of the importance of the transformation,17 we selected a reductive cross-coupling procedure as a benchmark reaction to test the feasibility of the approach described in Figure 1c.18 We started our optimization endeavors by selecting alkyl bromide 1 and aryl bromide 2 as model substrates. Representative entries are shown in Table 1, but a comprehensive survey of reaction conditions is reported in the Supporting Information. We selected benzophenone derivative I as a HAT photocatalyst, tris(trimethylsilyl)silane as the XAT promoter, nickel-based catalyst II as the transition-metal catalyst, and 2,6-lutidine as a homogeneous base to ensure the removal of the hydrobromic acid developed during the reaction. The reaction mixture was irradiated with a near-UV light source (λ = 390 nm) for 16 h. Under these conditions, product 3 was obtained in 75% yield (72% after isolation, entry 1).

Table 1. Optimization of the Reaction Conditions.

| entry | deviation | 3 yield (%)a,b |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | none | 75 (72) |

| 2 | 1.5 equiv of 1 | 51 |

| 3 | 1.1 equiv of (TMS)3SiH | 60 |

| 4 | Ph3SiH instead of (TMS)3SiH | 20 |

| 5 | acetone in place of CH3CN | 67 |

| 6 | Vapourtec 365 nm 45 min | 74 |

| 7 | no I, II, 2,6-lutidine or (TMS)3SiH | |

| 8 | no light or no light at 60 °C |

1 (1.25 mmol), 2 (0.5 mmol), BP I (20 mol %), Ni II (5 mol %), 2,6-lutidine (0.55 mmol), (TMS)3SiH (0.75 mmol) at room temperature, 390 nm for 16 h.

NMR yields using trichloroethylene as an external standard. Yield of the isolated compound is given in parentheses.

Reducing the amounts of alkyl bromide or silane resulted in lower yields (entries 2 and 3). Different silanes (e.g., Ph3SiH) were also evaluated but did not lead to efficient formation of the product (entry 4). Various HAT catalysts were tested and proved less effective than BP I (see the Supporting Information). The replacement of acetonitrile with acetone gave almost identical results (entry 5). Separate control experiments, each carried out omitting an individual component, revealed that light, I, II, base, and silane were all essential for the observed reactivity (entries 7 and 8). While these reactions can be smoothly carried out in batch, the homogeneity of the reaction mixture prompted us to investigate the possible development of a procedure in flow to reduce the reaction times and to increase the productivity of the overall process.19 For this purpose, we used a commercially available Vapourtec UV-150 reactor (PFA, V = 10 mL, ID = 0.80 mm), equipped with a UV lamp (λ = 365 nm, 16 W) and, after a short optimization of the residence times, found that the reaction could be readily performed with similar efficiency in only 45 min (entry 6, flow rate 0.22 mL min–1).

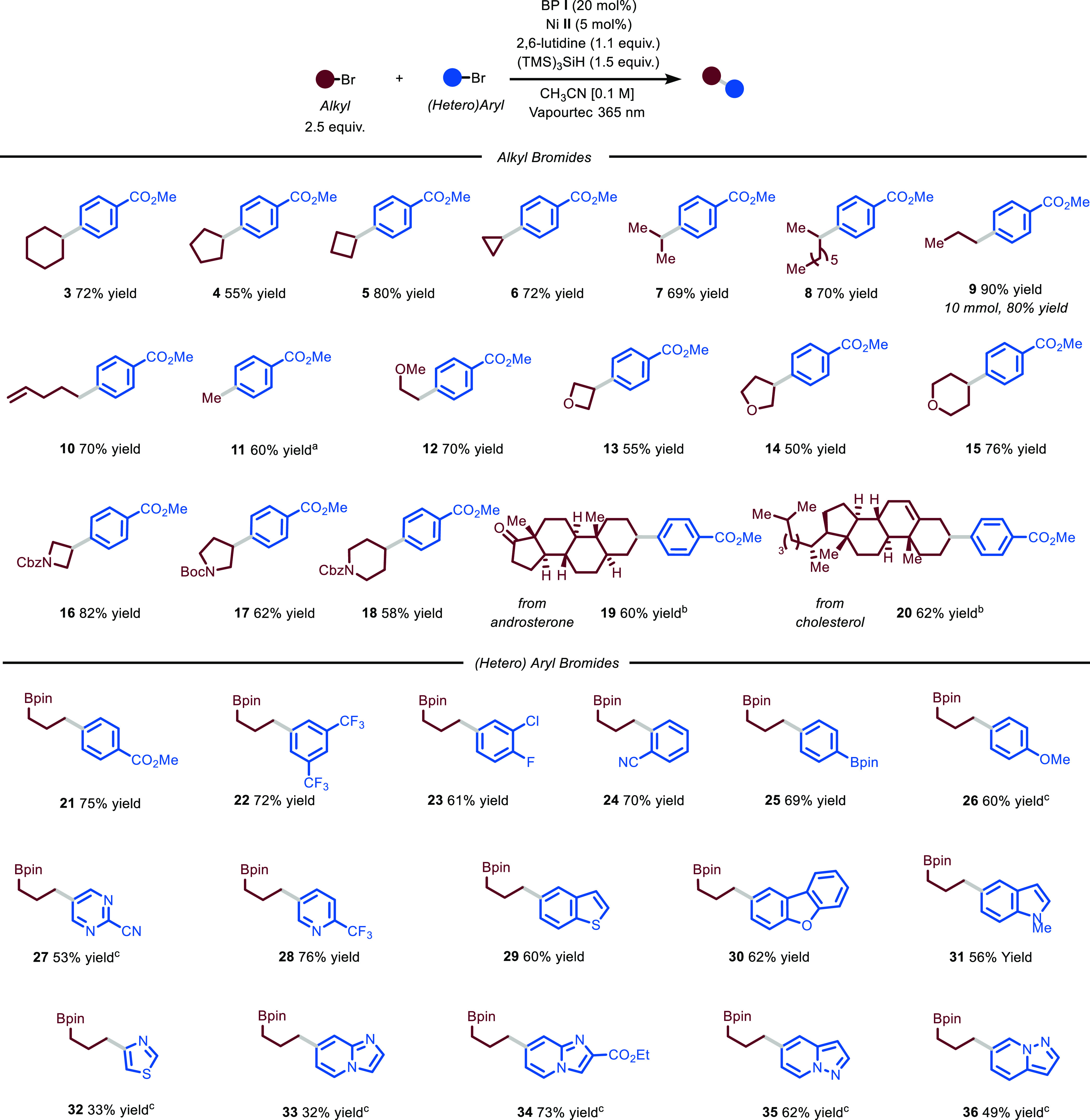

With suitable flow conditions in hand, we set off to interrogate the scope of the transformation (Figure 2). First, we combined methyl 4-bromobenzoate 2 with a diverse set of secondary cyclic alkyl bromides and found that the system is performing well regardless of the ring size (3–6, 55–80% yield).

Figure 2.

Survey of the aryl bromide and alkyl bromide reaction partners for the photocatalytic C(sp2)–C(sp3) cross-coupling protocol. Reaction conditions: aryl bromide (0.5 mmol), BP I (20 mol %), Ni II (5 mol %), 2,6-lutidine (1.1 equiv), (TMS)3SiH (1.5 equiv) at room temperature (rt) in Vapourtec UV-150 reactor (λ = 365 nm, 16 W, reactor volume: 10 mL, flow rate: 0.22 mL min–1, τ: 45 min). Yields refer to isolated products. aMeOTs as coupling partner (2.5 equiv) and TBABr as bromide source (2.5 equiv). bReactions performed in batch (16 h) using PhCF3 as solvent (see the Supporting Information). cReactions performed in batch (16 h) using Na2CO3 (1.5 equiv) instead of 2,6-lutidine. Bpin: Pinacol boronic ester, TBABr: tetrabutylammonium bromide.

Also, acyclic secondary alkyl substrates were effective coupling partners (7–8, 69–70% yield). Primary alkyl derivatives proved to be excellent reaction partners as well (9–11, 60–90% yield), including the methylation of aryl bromides with methyl tosylate in the presence of tetrabutylammonium bromide as bromide source (11, 60% yield). Notably, both primary and secondary oxygen-containing bromides were coupled with methyl 4-bromobenzoate 2 in good yields (12–15, 55–76% yield), showing no byproducts derived from competing HAT. Medicinally relevant moieties, such as azetidine, pyrrolidine, and piperidine, can be readily engaged in this protocol (16–18, 58–82% yield). To further highlight the synthetic utility of this process, we pursued the arylation of both androsterone and cholesterol bromides. Due to their low solubility in CH3CN, the reaction was conducted in batch using PhCF3 as solvent (19 and 20, 60–62%).

We then turned to assess the scope in terms of (hetero)aryl bromides and, to this end, we decided to use bromopropyl boronic pinacol ester to incorporate a functional handle for subsequent functionalization. Using identical microfluidic conditions, the reaction with model aryl bromide 2 gave 75% yield for compound 21. Double substitution at the meta positions is well tolerated (22, 72% yield). Interestingly, polyhalogenated arenes were solely functionalized at the C–Br bond (23, 61% yield), providing opportunities for sequential decoration of the arene core using, for example, classical cross-coupling conditions. Bromoarenes bearing substituents at the ortho position were smoothly cross-coupled (24, 70% yield), indicating that the protocol is not particularly sensitive to steric hindrance. Aryl bromides bearing electron-donating groups were also amenable to the reaction protocol: while pinacol boronic ester was well tolerated (25, 69% yield), 4-bromo anisole reacted more slowly requiring 16 h to yield the target compound 26 in 60% yield. Notably, also heteroarenes with different electronic properties could be readily functionalized using this photocatalytic protocol. For instance, electron-poor six-membered heteroaromatics, such as pyrimidines and pyridines, were efficiently converted into the desired products 27 and 28 (53–76% yield). Moreover, electron-rich heteroaromatics, such as benzofuran, benzothiophene, and methylated indole, proved to be suitable substrates for the process, leading to compounds 29, 30, and 31 in good chemical yields (60, 62, and 56% yields, respectively). Also, thiazoles (32, 33% yield), imidazo[1,2-a]pyridines (33–34, 32–73% yield), and pyrazo[1,2-a]pyridines (35–36, 49–62% yield) could be readily cross-coupled in synthetically useful yields. Finally, we performed a 20-fold scale-up using our continuous-flow protocol; this allowed us to isolate larger quantities of compound 9 simply by extending the total collection time in flow (see the Supporting Information for further details).20

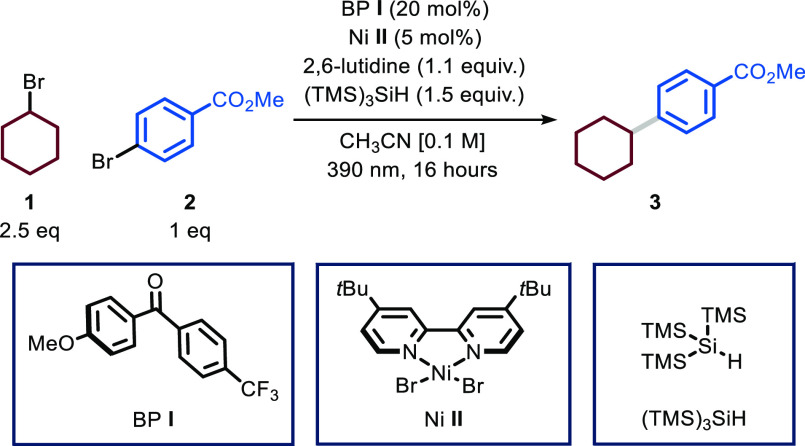

1,2-Dicarbofunctionalization of Olefins

After having established catalytic conditions for the reductive cross-coupling between alkyl and aryl bromides, we sought to further demonstrate the applicability of our approach to other reaction classes. Specifically, we wondered whether, using a similar reaction cocktail, we could promote the reductive 1,2-difunctionalization of olefins. The implementation of such a process could enable the construction of two new chemical bonds in a single operation, enabling the rapid buildup of molecular complexity starting from simple and widely available substrates. As a testament to the synthetic relevance of these reactions, several groups have focused on expanding photocatalytic cross-coupling procedures to olefin difunctionalization reactions.14 However, the majority of the reported methods are either relying on substrates suitable for single electron oxidation, such as trifluoroalkyl borates,14a carboxylates,14c or on substrates prone to HAT.14f,14g In fact, less attention has been devoted to the use of substrates prone to reduction, such as alkyl bromides. One report by the group of Martin highlighted the possibility to engage these derivatives in a metallaphotoredox process.14d However, as the method relies on SET to activate the substrate, only tertiary bromides, which possess an accessible redox potential, can be activated. As our method is based on a XAT activation step, we would not rely on the redox properties of the target substrate, but solely on the bond dissociation energy of the C–X bond.

With this idea in mind, we started our investigation by exploring the reaction between cyclohexyl bromide 1, tert-butyl acrylate 37, and aryl bromide 2 in PhCF3. Similar to the previous protocol, we selected BP I as a HAT photocatalyst, tris(trimethylsilyl)silane as the XAT promoter, nickel-based catalyst II as the transition-metal catalyst, and 2,6-lutidine as a homogeneous base (Table 2).

Table 2. Optimization of the Reaction Conditions.

| entry | deviation | yield (%)a,b |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | none | 58 |

| 2 | acetone as solvent | 36 |

| 3 | CH3CN as solvent | 25 |

| 4 | [0.2 M] | 60 |

| 5 | [0.4 M] | 64 (63) |

| 6 | [0.4 M] and K3PO4 or Na2CO3 | |

| 7 | no I, II, 2,6-lutidine, or (TMS)3SiH | |

| 8 | no light or no light at 60 °C |

1 (2.50 mmol), 37 (1.50 mmol), 2 (0.5 mmol), BP I (20 mol %), Ni II (5 mol %), 2,6-lutidine (0.55 mmol), and (TMS)3SiH (1 mmol) at room temperature, 390 nm for 16 h.

NMR yields using trichloroethylene as an external standard. Yield of the isolated compound is given in parentheses. BP: Benzophenone.

The reaction was run in a homemade three-dimensional (3D)-printed reactor equipped with a near-UV lamp (λ = 390 nm, see the Supporting Information for further details). Under these reaction conditions (entry 1), we observed the formation of the desired product 38 in 58% yield.

Notably, we did not find any traces of byproducts that result from the reduction of the olefin moiety by the intermediacy of a nickel hydride.21 Changing the solvent to acetone or acetonitrile was detrimental toward the formation of 38 (entries 2 and 3). However, by increasing the reaction concentration (entries 4 and 5), we obtained the desired product in increased yield. Notably, when using an inorganic base, the reaction did not proceed at all (entry 6). When removing the photocatalyst, Ni catalyst, 2,6-lutidine, or silane, no product was formed, highlighting their crucial role in the difunctionalization process (entry 7). Finally, the reaction is purely photocatalytic in nature as no product was detected when the protocol was run in the dark at 60 °C.

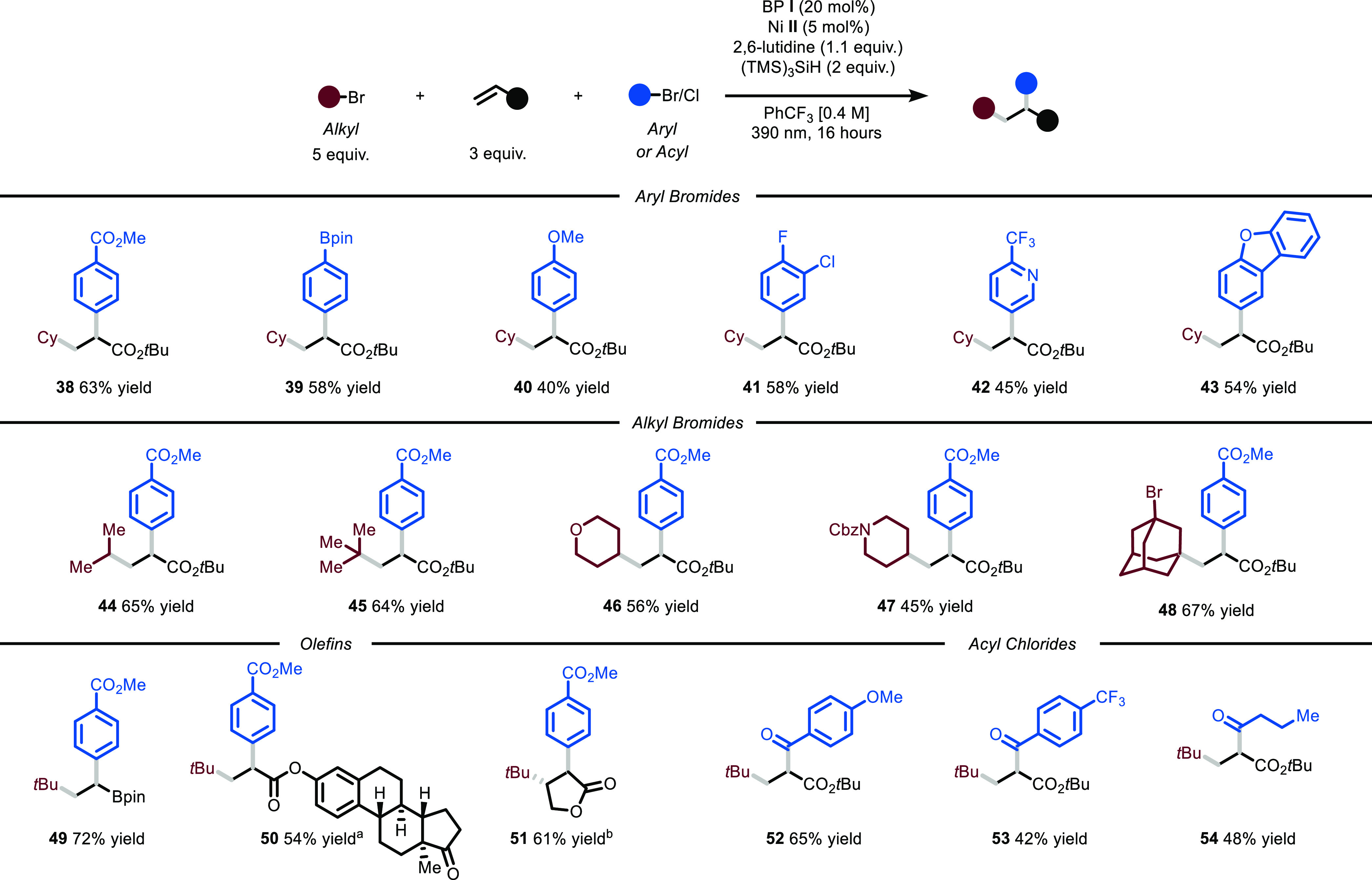

With optimal conditions in hand, we decided to evaluate the generality of this photocatalytic difunctionalization process (Figure 3). First, we assessed the scope by varying the aryl bromide coupling partner (38–43). Not only electron-poor (38, 63% yield) but also electron-rich derivatives could be converted into the desired products 39 and 40 (58 and 40% yields, respectively). As shown for our cross-coupling protocol, other halides on the aromatic ring, such as fluoride and chloride, remained untouched by the nickel catalyst, leading to the selective formation of 41 (58% yield). Finally, both electron-poor and electron-rich heteroarenes could be easily installed (42 and 43, 45 and 54% yields).

Figure 3.

Survey of the aryl bromides, alkyl bromides, olefins, and acyl chlorides that can participate in the photochemical protocol. Reaction conditions: aryl bromide or acyl chloride (0.5 mmol), BP I (20 mol %), Ni II (5 mol %), 2,6-lutidine (1.1 equiv), (TMS)3SiH (2 equiv) at rt, irradiated at 390 nm for 16 h. Yields refer to isolated product. a,1:1 d.r, b.20:1 d.r.. BP: benzophenone, Cbz: benzyloxycarbonyl, Bpin: pinacol boronic ester.

Next, we turned our attention toward the variation of the alkyl bromides that can undergo this transformation. Acyclic derivatives such as the one leading to 44 and 45 could be directly used (65 and 64% yield). Moreover, heterocyclic substrates containing oxygen (46, 56% yield) and nitrogen (47, 45% yield) atoms could be selectively functionalized on a position distal from the heteroatom, which is challenging via HAT.10 Additionally, because of the mild conditions of the process, we were able to selectively functionalize 1,3-dibromoadamantane on only a single position (48, 67% yield). We also found that vinylboronic acid pinacol ester could be smoothly engaged in the reaction protocol (49, 72% yield). Importantly, the presence of the boronic group serves as the entry point for further decoration of the organic scaffold using, for example, Suzuki–Miyaura cross-coupling conditions. Moreover, an estrone-containing olefin swiftly reacted to yield the targeted difunctionalized product (50, 54% yield). A five-membered ring lactone was also efficiently converted to the desired product (51, 61% yield) with full control on diastereoselectivity. Finally, we observed that also acyl chlorides could be used as electrophiles in the nickel catalytic cycle to afford 2-substituted 1,3-dicarbonyl compounds. Importantly, not only electron-rich (52, 65% yield) and electron-poor (53, 42% yield) aroyl derivatives could be employed but also alkyl ones (54, 48% yield).

The results detailed in this section demonstrate the applicability of this (H)XAT platform to the difunctionalization of olefin derivatives, leading to rather complex structures starting from simple precursors.

Mechanistic Studies

As for the mechanistic scenario, we envisaged that photocatalyzed HAT would afford a nucleophilic tris(trimethylsilyl)silyl radical accountable for the subsequent XAT event from the alkyl bromide, delivering a C-centered radical. Parallelly, an in situ generated Ni0 species undergoes oxidative addition onto the aryl bromide to generate a relatively stable Ar–NiII–Br species. In the case of the direct cross-coupling, upon interception of the C-centered radical generated via XAT, a NiIII intermediate is generated, which readily undergoes reductive elimination to forge a C(sp3)–C(sp2) bond. Conversely, in the case of the three-component reaction, the alkyl radical is first intercepted by an electron-poor olefin and then the resulting radical adduct enters the Ni-catalytic cycle for the formation of the desired C(sp3)–C(sp2) bond. For both transformations, we identified three crucial steps to be investigated: (i) the HAT event (Figure 4a), (ii) the XAT step, and (iii) the radical trapping by the nickel catalytic cycle.

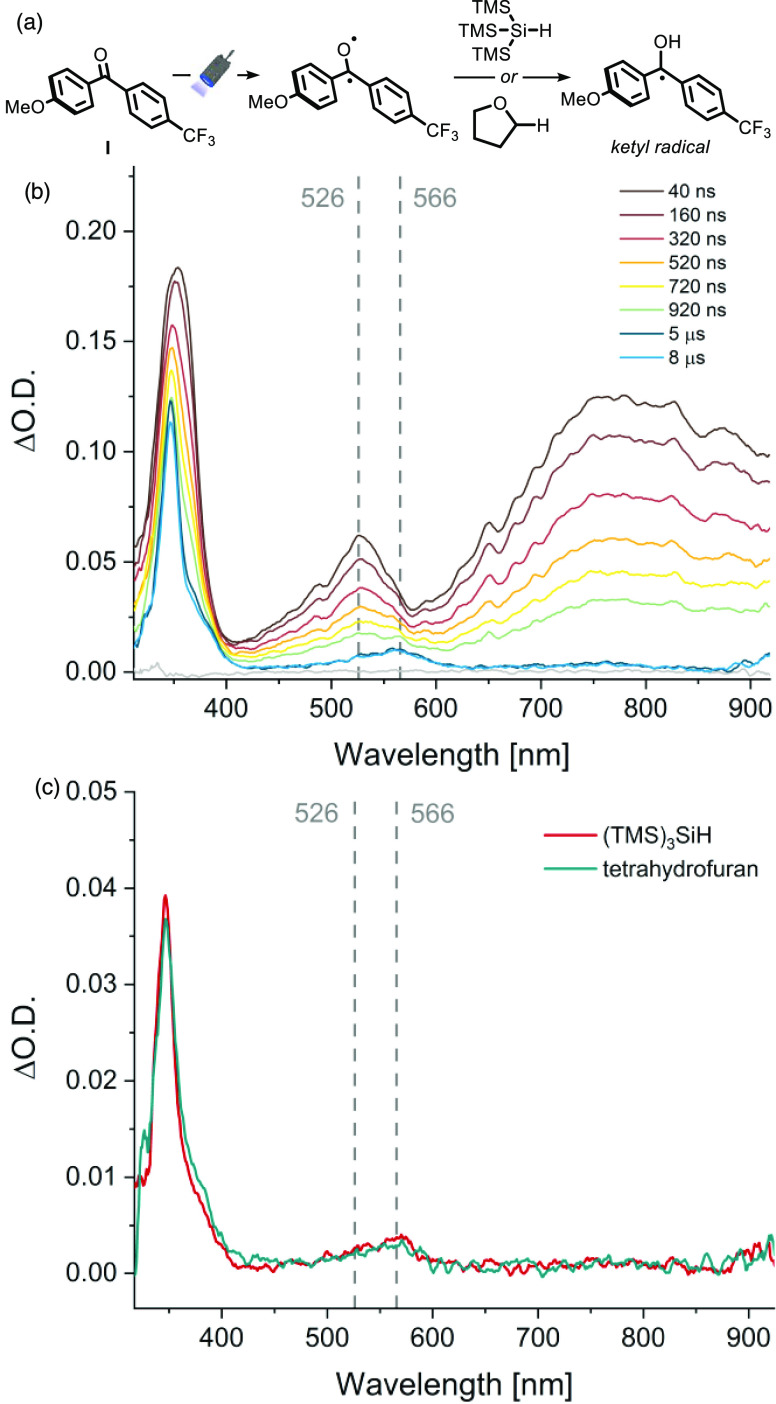

Figure 4.

(a) Photoexcitation of benzophenone entails the hydrogen atom abstraction from the silane. (b) Microsecond triplet–triplet differential absorption spectra recorded at different times after laser excitation of the employed BP I in deoxygenated acetonitrile with a 5 ns laser pulse at 319 nm in the presence of an excess of (TMS)3SiH (8.6 equiv). (c) Comparison of microsecond triplet–triplet differential absorption spectra recorded at 50 μs after 319 nm excitation in the presence of (red dash) (TMS)3SiH (8.6 equiv) and (green dash) tetrahydrofuran (8.6 equiv).

First, we started by observing the decay of the triplet excited state of the employed BP I (5 × 10–4 M in CH3CN, degassed solution) via transient absorption spectroscopy (TAS). In particular, upon excitation with a tunable Nd:YAG-laser (λex = 319 nm, 1 mJ), a characteristic band is formed at 526 nm due to a triplet–triplet transition (see the Supporting Information), which very much resembles the one observed for the parent benzophenone.22 This band was monitored over a period of 50 μs and decayed completely with comparable rates in CH3CN and benzene, which suggests that the excited state of the diaryl ketone is not quenched by acetonitrile (see the Supporting Information).23,24 Next, we performed the same experiment in the presence of an excess of silane (8.6 equiv): the overall intensity of the spectrum decreased, together with the appearance of a new long-living feature with a shoulder at 375 nm and a weak, broad band at 566 nm (Figure 4b). The quenching constant for the triplet excited state of parent benzophenone by tris(trimethylsilyl)silane has been reported to be 108 M–1 s–1 (Φ = 0.95).25 Based on comparison with the literature,26 we hypothesized that the species responsible for this new spectrum could be the ketyl radical generated upon HAT from the silane. It is important to stress that the latter compound does not absorb light significantly at the excitation wavelength.25

To ascertain the presence of the ketyl radical, we reasoned that a similar spectral feature would be observed if a different H-donor was used. Indeed, when tetrahydrofuran (8.6 equiv), a well-known quencher for diaryl ketones triplet excited states via HAT, was added as a quencher instead of tris(trimethylsilyl)silane, the very same persistent signal was observed (Figure 4c). These experiments prove that BP I can activate the silane via HAT to afford a highly nucleophilic tris(trimethylsilyl)silyl radical.

We also recognized the possibility that a photogenerated bromine radical might be responsible for the HAT event from the silane.6g,27,28 In this scenario, the employed photocatalyst would oxidize the bromide generated upon oxidative addition to afford the halogen atom.29 In fact, we found that the luminescence of the photocatalyst was quenched by TBABr and silane with comparable rates (kSV = 325 and 121 M–1, respectively). However, since the concentration of the latter is much higher, a direct photocatalyzed HAT is more likely. To confirm our hypothesis, we compared the initial rates of the direct coupling under standard conditions and in the presence of TBABr (0.5 equiv, see the Supporting Information for further details). The reaction is slightly slower in the presence of the bromide, which led us to exclude that the latter is significantly contributing to the observed reactivity.

Additionally, we wondered whether the aforementioned HAT step was rate-determining for the transformation and set off to evaluate the kinetic isotope effect (KIE) via the parallel reactions method, accordingly (see the Supporting Information).30 In detail, we selected the direct coupling to study this aspect: the use of (TMS)3Si-D did not affect the rate of product formation, which resulted in a KIE ∼ 1. Hence, HAT is not the rate-determining step of the reaction.

We also investigated the feasibility of the XAT event triggered by the silyl radical by computational means ((U)M06-2X/6-311++G(d,p)):31 a ΔG = −16 kcal·mol–1 was found, suggesting an exergonic process (see the Supporting Information).

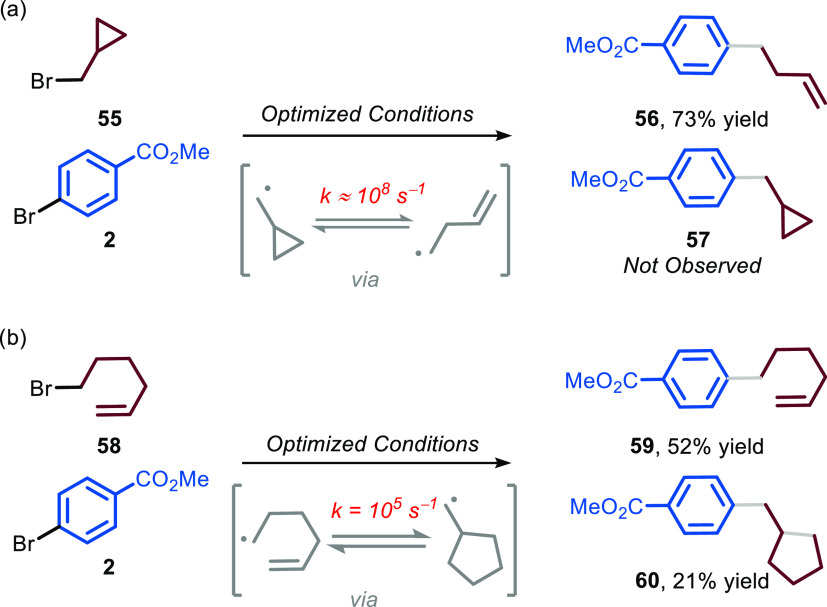

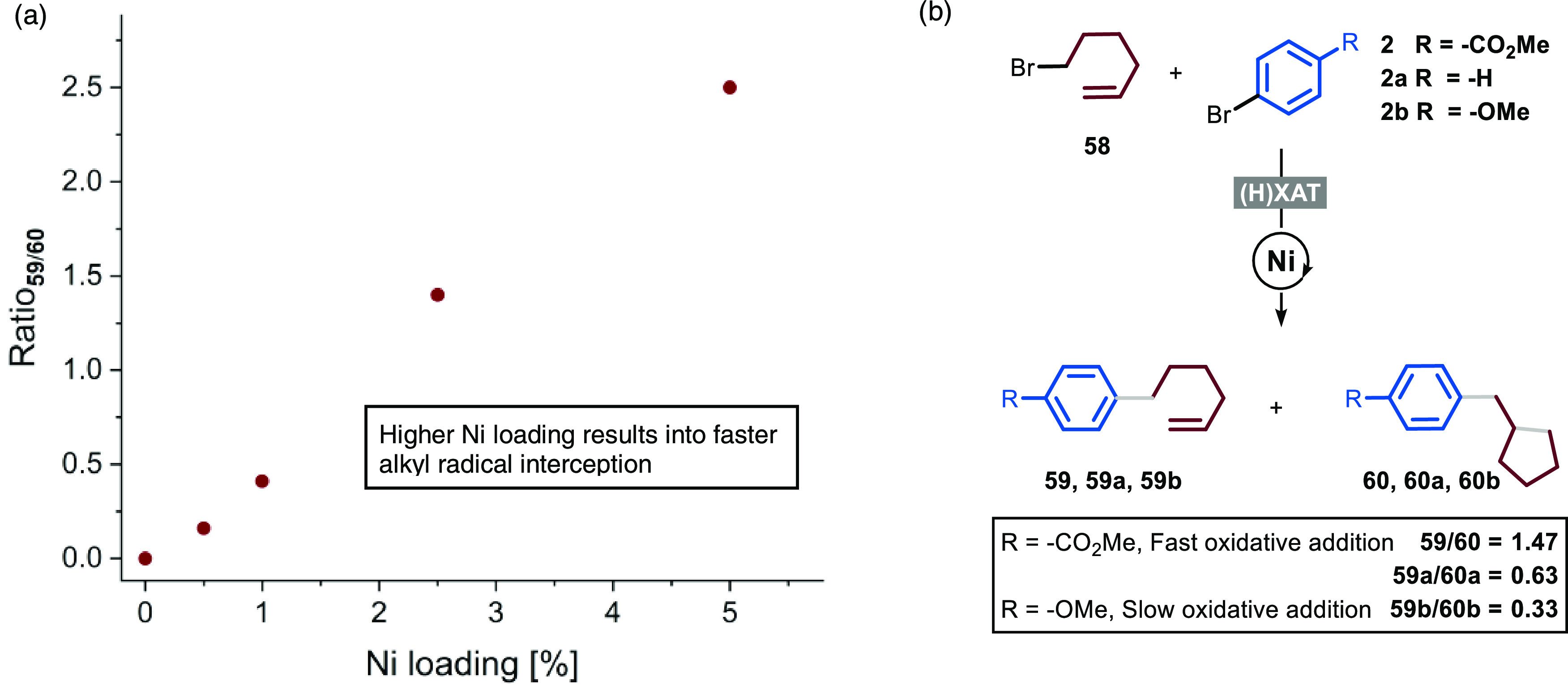

Subsequently, we decided to unequivocally assess the radical nature of the mechanism and get insights into the rate of radical addition on the nickel species by performing radical clock experiments (Figure 5). We selected (bromomethyl)cyclopropane 55 and 6-bromo-1-hexene 58 as probes and found out that, in the former case, only product 56 was formed, while in the latter case, a mixture of uncyclized (59) and cyclized (60) products was observed. Besides proving the radical nature of the mechanism, these experiments allow us to calculate a kinetic constant for the alkyl radical interception in the order of 107 M–1 s–1 (see the Supporting Information).32

Figure 5.

Radical clock experiments. (a) Reaction with (bromomethyl)cyclopropane 55 affords product 56, yield refers to isolated product; (b) reaction with 6-bromo-1-hexene 58 affords a mixture of uncyclized product 59 and cyclized product 60, yields were calculated by gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC–MS).

The observation of a mixture of cyclized and uncyclized products when employing 58 led us to explore the influence of the conversion, as well as the nickel loading and the nature of the aryl bromide, on the ratio of the uncyclized versus cyclized products (Figure 6). In agreement with a previously reported protocol, we have observed no significant changes in the ratio with conversions higher than 50% (see the Supporting Information for further details).33 On the other hand, when performing the reaction with different nickel catalyst loadings (Figure 6a), we clearly observed a trend in the ratio: the higher the nickel loading, the higher the amount of uncyclized product. This observation is in good agreement with a situation where, in the presence of high amounts of nickel catalyst, the radical is trapped more rapidly by the latter, outpacing the cyclization step, which is instead predominant when the catalyst is present in low amounts.

Figure 6.

(a) Evaluation of the influence of the nickel loading on the ratio of uncyclized and cyclized products. Reactions performed in the optimized conditions (as in Table 1, entry 1), varying the loading of nickel. (b) Evaluation of the influence of the nature of the aryl bromide on the ratio of uncyclized and cyclized products. Reactions performed in the optimized conditions (as in Table 1, entry 1) with 2.5 mol % of Ni II.

Finally, we evaluated the influence of the nature of the aryl bromide (Figure 6b). We selected aryl bromides bearing different groups (−OMe, −H, −CO2Me), and we subjected them in parallel to the reaction conditions. We observed that the more electron-rich the aromatic ring is, the lower the ratio of the uncyclized versus cyclized product becomes. These intriguing findings suggest that, as the nature of the aryl bromide influences the product distribution, the radical is likely adding on a nickel species arising after oxidative addition, possibly a nickel(II) intermediate, as postulated by the group of Martin.6b

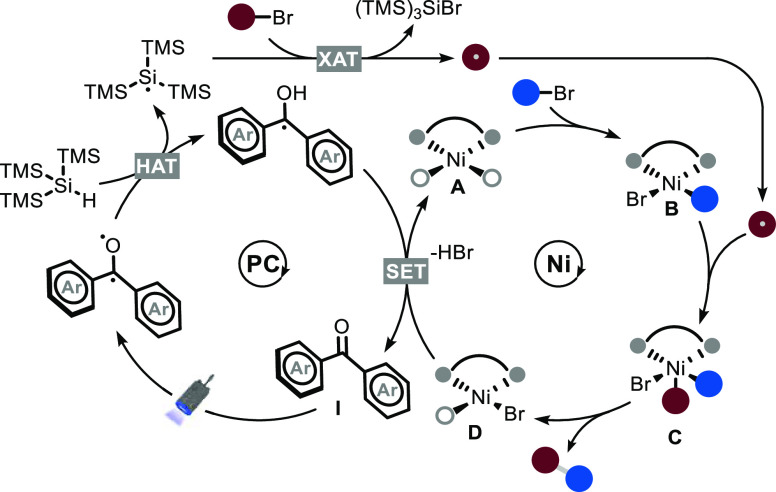

Combining all of these experimental insights, we propose the following reaction mechanism for reductive cross-coupling (Figure 7). Photoexcitation of BP I leads to a diradical species that is responsible for the abstraction of a hydrogen atom from tris(trimethylsilyl)silane, generating a silicon-centered radical.

Figure 7.

Proposed reaction mechanism for the (H)XAT cross-electrophile coupling.

The latter species is capable of abstracting a bromine atom from an alkyl bromide, affording a carbon-centered radical. Simultaneously, nickel catalyst A is able to activate an aryl bromide through oxidative addition, affording intermediate B that is responsible to trap the alkyl radical, affording C. Reductive elimination generates the target product and Ni(I) species D, which engages with the reduced form of the BP I in a SET step to close both catalytic cycles. In agreement with such a mechanistic picture,34 we calculated the quantum yield for the direct coupling to be 3%, thus excluding a radical chain process. We envision that a similar mechanistic scenario is operational in the 1,2-difunctionalization. In particular, the first-formed C-centered radical is intercepted by the electron-poor olefin and the ensuing radical enters the nickel catalytic cycle.

Conclusions

In conclusion, we have detailed the development of an operationally convenient HAT-induced XAT methodology that exploits the synergistic combination of benzophenone catalysis and a silane reagent with nickel catalysis to promote both the direct cross-electrophile coupling and the 1,2-dicarbofunctionalization of olefins. Our mechanistic studies demonstrate that the process involves a photoinduced HAT-XAT sequence leading to a carbon-centered radical that can be trapped by a nickel(II) species. Given the mild reaction conditions and the ability to engage medicinally relevant alkyl and aryl bromides, we anticipate that this methodology will be of great value to synthetic chemists in both academia and industry.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Tom Masson for designing the photoreactors used in this work, and Michiel Hilbers for support with the spectroscopic experiments. Additionally, they are grateful to Prof. Davide Ravelli for fruitful discussions.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acscatal.2c03805.

Experimental details, used materials, sample preparation and analytical data (NMR) (PDF)

Author Contributions

# A.L. and D.M. contributed equally.

The authors are grateful to have received generous funding from the Lilly Research Award Program (A.L. and T.N.). They also thank the European Union H2020 research and innovation program under the Marie S. Curie Grant Agreement (ELECTRORGANO, No. 101022144, D.M.; HAT-TRICK, No. 101023615, L.C.).

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Notes

The primary NMR FID files for compounds 3–36 and 38–54 are available in the FigShare repository at DOI: 10.21942/uva.20237352.

Supplementary Material

References

- a Chan A. Y.; Perry I. B.; Bissonnette N. B.; Buksh B. F.; Edwards G. A.; Frye L. I.; Garry O. L.; Lavagnino M. N.; Li B. X.; Liang Y.; Mao E.; Millet A.; Oakley J. V.; Reed N. L.; Sakai H. A.; Seath C. P.; MacMillan D. W. C. Metallaphotoredox: The Merger of Photoredox and Transition Metal Catalysis. Chem. Rev. 2022, 122, 1485–1542. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.1c00383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Twilton J.; Le C.; Zhang P.; Shaw M. H.; Evans R. W.; MacMillan D. W. C. The Merger of Transition Metal and Photocatalysis. Nat. Rev. Chem. 2017, 1, 0052 10.1038/s41570-017-0052. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c De Abreu M.; Belmont P.; Brachet E. Synergistic Photoredox/Transition-Metal Catalysis for Carbon-Carbon Bond Formation Reactions. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2020, 2020, 1327–1378. 10.1002/ejoc.201901146. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Levin M. D.; Kim S.; Toste F. D. Photoredox Catalysis Unlocks Single-Electron Elementary Steps in Transition Metal Catalyzed Cross-Coupling. ACS Cent. Sci. 2016, 2, 293–301. 10.1021/acscentsci.6b00090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Zuo Z.; Ahneman D. T.; Chu L.; Terrett J. A.; Doyle A. G.; MacMillan D. W. C. Merging Photoredox with Nickel Catalysis: Coupling of α-Carboxyl sp3-Carbons with Aryl Halides. Science 2014, 345, 437–440. 10.1126/science.1255525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Tellis J. C.; Primer D. N.; Molander G. A. Single-Electron Transmetalation in Organoboron Cross-Coupling by Photoredox/Nickel Dual Catalysis. Science 2014, 345, 433–436. 10.1126/science.1253647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Shu X.-z.; Zhang M.; He Y.; Frei H.; Toste F. D. Dual Visible Light Photoredox and Gold-Catalyzed Arylative Ring Expansion. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 5844–5847. 10.1021/ja500716j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Romero N. A.; Nicewicz D. A. Organic Photoredox Catalysis. Chem. Rev. 2016, 116, 10075–10166. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.6b00057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Prier C. K.; Rankic D. A.; MacMillan D. W. C. Visible Light Photoredox Catalysis with Transition Metal Complexes: Applications in Organic Synthesis. Chem. Rev. 2013, 113, 5322–5363. 10.1021/cr300503r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Goddard J.-P.; Ollivier C.; Fensterbank L. Photoredox Catalysis for the Generation of Carbon Centered Radicals. Acc. Chem. Res. 2016, 49, 1924–1936. 10.1021/acs.accounts.6b00288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Thullen S. M.; Rovis T. A Mild Hydroaminoalkylation of Conjugated Dienes Using a Unified Cobalt and Photoredox Catalytic System. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 15504–15508. 10.1021/jacs.7b09252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Kautzky J. A.; Wang T.; Evans R. W.; MacMillan D. W. C. Decarboxylative Trifluoromethylation of Aliphatic Carboxylic Acids. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 6522–6526. 10.1021/jacs.8b02650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Jouffroy M.; Primer D. N.; Molander G. A. Base-Free Photoredox/Nickel Dual-Catalytic Cross-Coupling of Ammonium Alkylsilicates. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 475–478. 10.1021/jacs.5b10963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Alandini N.; Buzzetti L.; Favi G.; Schulte T.; Candish L.; Collins K. D.; Melchiorre P. Amide Synthesis by Nickel/Photoredox-Catalyzed Direct Carbamoylation of (Hetero)Aryl Bromides. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 5248–5253. 10.1002/anie.202000224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Dauncey E. M.; Dighe S. U.; Douglas J. J.; Leonori D. A Dual Photoredox-Nickel Strategy for Remote Functionalization via Iminyl Radicals: Radical Ring-Opening-Arylation, -Vinylation and -Alkylation Cascades. Chem. Sci. 2019, 10, 7728–7733. 10.1039/C9SC02616A. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f Guo L.; Song F.; Zhu S.; Li H.; Chu L. Syn-Selective Alkylarylation of Terminal Alkynes via the Combination of Photoredox and Nickel Catalysis. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 4543 10.1038/s41467-018-06904-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Perry I. B.; Brewer T. F.; Sarver P. J.; Schultz D. M.; DiRocco D. A.; MacMillan D. W. C. Direct Arylation of Strong Aliphatic C–H Bonds. Nature 2018, 560, 70–75. 10.1038/s41586-018-0366-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Shen Y.; Gu Y.; Martin R. sp3 C–H Arylation and Alkylation Enabled by the Synergy of Triplet Excited Ketones and Nickel Catalysts. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 12200–12209. 10.1021/jacs.8b07405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Mazzarella D.; Pulcinella A.; Bovy L.; Broersma R.; Noël T. Rapid and Direct Photocatalytic C(sp3)–H Acylation and Arylation in Flow. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2021, 60, 21277–21282. 10.1002/anie.202108987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Cao H.; Kuang Y.; Shi X.; Wong K. L.; Tan B. B.; Kwan J. M. C.; Liu X.; Wu J. Photoinduced Site-Selective Alkenylation of Alkanes and Aldehydes with Aryl Alkenes. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 1956 10.1038/s41467-020-15878-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Wang L.; Wang T.; Cheng G.-J.; Li X.; Wei J.-J.; Guo B.; Zheng C.; Chen G.; Ran C.; Zheng C. Direct C–H Arylation of Aldehydes by Merging Photocatalyzed Hydrogen Atom Transfer with Palladium Catalysis. ACS Catal. 2020, 10, 7543–7551. 10.1021/acscatal.0c02105. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; f Huang H.-M.; Bellotti P.; Chen P.-P.; Houk K. N.; Glorius F. Allylic C(sp3)–H Arylation of Olefins via Ternary Catalysis. Nat. Synth. 2022, 1, 59–68. 10.1038/s44160-021-00006-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; g Huang L.; Rueping M. Direct Cross-Coupling of Allylic C(sp3)–H Bonds with Aryl- and Vinylbromides by Combined Nickel and Visible-Light Catalysis. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2018, 57, 10333–10337. 10.1002/anie.201805118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; h Shields B. J.; Doyle A. G. Direct C(sp3)–H Cross Coupling Enabled by Catalytic Generation of Chlorine Radicals. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 12719–12722. 10.1021/jacs.6b08397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; i Ackerman L. K. G.; Martinez Alvarado J. I.; Doyle A. G. Direct C–C Bond Formation from Alkanes Using Ni-Photoredox Catalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 14059–14063. 10.1021/jacs.8b09191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Govaerts S.; Nyuchev A.; Noël T. Pushing the Boundaries of C–H Bond Functionalization Chemistry Using Flow Technology. J. Flow Chem. 2020, 10, 13–71. 10.1007/s41981-020-00077-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Capaldo L.; Quadri L. L.; Ravelli D. Photocatalytic Hydrogen Atom Transfer: The Philosopher’s Stone for Late-Stage Functionalization. Green Chem. 2020, 22, 3376–3396. 10.1039/D0GC01035A. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Capaldo L.; Ravelli D. Hydrogen Atom Transfer (HAT): A Versatile Strategy for Substrate Activation in Photocatalyzed Organic Synthesis. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2017, 2017, 2056–2071. 10.1002/ejoc.201601485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravelli D.; Protti S.; Fagnoni M. Decatungstate Anion for Photocatalyzed “Window Ledge” Reactions. Acc. Chem. Res. 2016, 49, 2232–2242. 10.1021/acs.accounts.6b00339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fagnoni M.; Protti S.; Ravelli D.. Photoorganocatalysis in Organic Synthesis, Catalytic Science Series; WORLD SCIENTIFIC (EUROPE), 2019; Vol. 18. DOI: 10.1142/q0180. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Galeotti M.; Salamone M.; Bietti M. Electronic Control over Site-Selectivity in Hydrogen Atom Transfer (HAT) Based C(sp3)–H Functionalization Promoted by Electrophilic Reagents. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2022, 51, 2171–2223. 10.1039/D1CS00556A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juliá F.; Constantin T.; Leonori D. Applications of Halogen-Atom Transfer (XAT) for the Generation of Carbon Radicals in Synthetic Photochemistry and Photocatalysis. Chem. Rev. 2022, 122, 2292–2352. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.1c00558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Zhang P.; Le C.; MacMillan D. W. C. Silyl Radical Activation of Alkyl Halides in Metallaphotoredox Catalysis: A Unique Pathway for Cross-Electrophile Coupling. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 8084–8087. 10.1021/jacs.6b04818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Bacauanu V.; Cardinal S.; Yamauchi M.; Kondo M.; Fernández D. F.; Remy R.; MacMillan D. W. C. Metallaphotoredox Difluoromethylation of Aryl Bromides. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2018, 57, 12543–12548. 10.1002/anie.201807629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Kornfilt D. J. P.; MacMillan D. W. C. Copper-Catalyzed Trifluoromethylation of Alkyl Bromides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 6853–6858. 10.1021/jacs.9b03024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Chen T. Q.; MacMillan D. W. C. A Metallaphotoredox Strategy for the Cross-Electrophile Coupling of α-Chloro Carbonyls with Aryl Halides. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 14584–14588. 10.1002/anie.201909072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Sakai H. A.; Liu W.; Le C.; MacMillan D. W. C. Cross-Electrophile Coupling of Unactivated Alkyl Chlorides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 11691–11697. 10.1021/jacs.0c04812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f Dow N. W.; Cabré A.; MacMillan D. W. C. A General N-Alkylation Platform via Copper Metallaphotoredox and Silyl Radical Activation of Alkyl Halides. Chem 2021, 7, 1827–1842. 10.1016/j.chempr.2021.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g Kerackian T.; Reina A.; Bouyssi D.; Monteiro N.; Amgoune A. Silyl Radical Mediated Cross-Electrophile Coupling of N-Acyl-Imides with Alkyl Bromides under Photoredox/Nickel Dual Catalysis. Org. Lett. 2020, 22, 2240–2245. 10.1021/acs.orglett.0c00442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; h Kölmel D. K.; Ratnayake A. S.; Flanagan M. E. Photoredox Cross-Electrophile Coupling in DNA-Encoded Chemistry. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2020, 533, 201–208. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2020.04.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; i Zhou Q.-Q.; Düsel S. J. S.; Lu L.-Q.; König B.; Xiao W.-J. Alkenylation of Unactivated Alkyl Bromides through Visible Light Photocatalysis. Chem. Commun. 2019, 55, 107–110. 10.1039/C8CC08362B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Zhao H.; McMillan A. J.; Constantin T.; Mykura R. C.; Juliá F.; Leonori D. Merging Halogen-Atom Transfer (XAT) and Cobalt Catalysis to Override E2-Selectivity in the Elimination of Alkyl Halides: A Mild Route toward Contra-Thermodynamic Olefins. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143, 14806–14813. 10.1021/jacs.1c06768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Zhang Z.; Górski B.; Leonori D. Merging Halogen-Atom Transfer (XAT) and Copper Catalysis for the Modular Suzuki–Miyaura-Type Cross-Coupling of Alkyl Iodides and Organoborons. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022, 144, 1986–1992. 10.1021/jacs.1c12649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Yedase G. S.; Jha A. K.; Yatham V. R. Visible-Light Enabled C(sp3)–C(sp2) Cross-Electrophile Coupling via Synergistic Halogen-Atom Transfer (XAT) and Nickel Catalysis. J. Org. Chem. 2022, 87, 5442–5450. 10.1021/acs.joc.2c00251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Górski B.; Barthelemy A.-L.; Douglas J. J.; Juliá F.; Leonori D. Copper-Catalysed Amination of Alkyl Iodides Enabled by Halogen-Atom Transfer. Nat. Catal. 2021, 4, 623–630. 10.1038/s41929-021-00652-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Campbell M. W.; Compton J. S.; Kelly C. B.; Molander G. A. Three-Component Olefin Dicarbofunctionalization Enabled by Nickel/Photoredox Dual Catalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 20069–20078. 10.1021/jacs.9b08282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b García-Domínguez A.; Mondal R.; Nevado C. Dual Photoredox/Nickel-Catalyzed Three-Component Carbofunctionalization of Alkenes. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 12286–12290. 10.1002/anie.201906692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Mega R. S.; Duong V. K.; Noble A.; Aggarwal V. K. Decarboxylative Conjunctive Cross-coupling of Vinyl Boronic Esters Using Metallaphotoredox Catalysis. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 4375–4379. 10.1002/anie.201916340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Sun S.; Duan Y.; Mega R. S.; Somerville R. J.; Martin R. Site-Selective 1,2-Dicarbofunctionalization of Vinyl Boronates through Dual Catalysis. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 4370–4374. 10.1002/anie.201916279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Zheng S.; Chen Z.; Hu Y.; Xi X.; Liao Z.; Li W.; Yuan W. Selective 1,2-Aryl-Aminoalkylation of Alkenes Enabled by Metallaphotoredox Catalysis. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 17910–17916. 10.1002/anie.202006439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f Xu S.; Chen H.; Zhou Z.; Kong W. Three-Component Alkene Difunctionalization by Direct and Selective Activation of Aliphatic C–H Bonds. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2021, 60, 7405–7411. 10.1002/anie.202014632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g Campbell M. W.; Yuan M.; Polites V. C.; Gutierrez O.; Molander G. A. Photochemical C–H Activation Enables Nickel-Catalyzed Olefin Dicarbofunctionalization. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143, 3901–3910. 10.1021/jacs.0c13077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- For reviews on the topic, please see:; a Wang X.; Dai Y.; Gong H. Nickel-Catalyzed Reductive Couplings. Top. Curr. Chem. 2016, 374, 43 10.1007/s41061-016-0042-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Weix D. J. Methods and Mechanisms for Cross-Electrophile Coupling of Csp2 Halides with Alkyl Electrophiles. Acc. Chem. Res. 2015, 48, 1767–1775. 10.1021/acs.accounts.5b00057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; For selected examples please see:; c Everson D. A.; Jones B. A.; Weix D. J. Replacing Conventional Carbon Nucleophiles with Electrophiles: Nickel-Catalyzed Reductive Alkylation of Aryl Bromides and Chlorides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 6146–6159. 10.1021/ja301769r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Wang S.; Qian Q.; Gong H. Nickel-Catalyzed Reductive Coupling of Aryl Halides with Secondary Alkyl Bromides and Allylic Acetate. Org. Lett. 2012, 14, 3352–3355. 10.1021/ol3013342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Beutner G. L.; Simmons E. M.; Ayers S.; Bemis C. Y.; Goldfogel M. J.; Joe C. L.; Marshall J.; Wisniewski S. R. A Process Chemistry Benchmark for sp2–sp3 Cross Couplings. J. Org. Chem. 2021, 86, 10380–10396. 10.1021/acs.joc.1c01073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- For reviews on the topic, please see:; a Gao P.; Niu Y.-J.; Yang F.; Guo L.-N.; Duan X.-H. Three-Component 1,2-Dicarbofunctionalization of Alkenes Involving Alkyl Radicals. Chem. Commun. 2022, 58, 730–746. 10.1039/D1CC05730H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Yi L.; Ji T.; Chen K.-Q.; Chen X.-Y.; Rueping M. Nickel-Catalyzed Reductive Cross-Couplings: New Opportunities for Carbon–Carbon Bond Formations through Photochemistry and Electrochemistry. CCS Chem. 2022, 4, 9–30. 10.31635/ccschem.021.202101196. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Luo Y.; Xu C.; Zhang X. Nickel-Catalyzed Dicarbofunctionalization of Alkenes. Chin. J. Chem. 2020, 38, 1371–1394. 10.1002/cjoc.202000224. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; For selected examples of thermal 1,2 difunctionalization reactions please see:; d García-Domínguez A.; Li Z.; Nevado C. Nickel-Catalyzed Reductive Dicarbofunctionalization of Alkenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 6835–6838. 10.1021/jacs.7b03195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Shu W.; García-Domínguez A.; Quirós M. T.; Mondal R.; Cárdenas D. J.; Nevado C. Ni-Catalyzed Reductive Dicarbofunctionalization of Nonactivated Alkenes: Scope and Mechanistic Insights. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 13812–13821. 10.1021/jacs.9b02973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f Yang T.; Chen X.; Rao W.; Koh M. J. Broadly Applicable Directed Catalytic Reductive Difunctionalization of Alkenyl Carbonyl Compounds. Chem 2020, 6, 738–751. 10.1016/j.chempr.2019.12.026. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dombrowski A. W.; Gesmundo N. J.; Aguirre A. L.; Sarris K. A.; Young J. M.; Bogdan A. R.; Martin M. C.; Gedeon S.; Wang Y. Expanding the Medicinal Chemist Toolbox: Comparing Seven C(sp2)–C(sp3) Cross-Coupling Methods by Library Synthesis. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2020, 11, 597–604. 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.0c00093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knappke C. E. I.; Grupe S.; Gärtner D.; Corpet M.; Gosmini C.; Jacobi von Wangelin A. Reductive Cross-Coupling Reactions between Two Electrophiles. Chem. – Eur. J. 2014, 20, 6828–6842. 10.1002/chem.201402302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Cambié D.; Bottecchia C.; Straathof N. J. W.; Hessel V.; Noël T. Applications of Continuous-Flow Photochemistry in Organic Synthesis, Material Science, and Water Treatment. Chem. Rev. 2016, 116, 10276–10341. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Buglioni L.; Raymenants F.; Slattery A.; Zondag S. D. A.; Noël T. Technological Innovations in Photochemistry for Organic Synthesis: Flow Chemistry, High-Throughput Experimentation, Scale-up, and Photoelectrochemistry. Chem. Rev. 2022, 122, 2752–2906. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.1c00332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Faraggi T. M.; Rouget-Virbel C.; Rincón J. A.; Barberis M.; Mateos C.; García-Cerrada S.; Agejas J.; de Frutos O.; MacMillan D. W. C. Org. Process Res. Dev. 2021, 25, 1966–1973. 10.1021/acs.oprd.1c00208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d González-Esguevillas M.; Fernández D. F.; Rincón J. A.; Barberis M.; de Frutos O.; Mateos C.; García-Cerrada S.; Agejas J.; MacMillan D. W. C. Rapid Optimization of Photoredox Reactions for Continuous-Flow Systems Using Microscale Batch Technology. ACS Cent. Sci. 2021, 7, 1126–1134. 10.1021/acscentsci.1c00303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Debrouwer W.; Kimpe W.; Dangreau R.; Huvaere K.; Gemoets H. P. L.; Mottaghi M.; Kuhn S.; Van Aken K. Ir/Ni Photoredox Dual Catalysis with Heterogeneous Base Enabled by an Oscillatory Plug Flow Photoreactor. Org. Process Res. Dev. 2020, 24, 2319–2325. 10.1021/acs.oprd.0c00150. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dong Z.; Wen Z.; Zhao F.; Kuhn S.; Noël T. Scale-up of Micro- and Milli-Reactors: An Overview of Strategies, Design Principles and Applications. Chem. Eng. Sci.: X 2021, 10, 100097 10.1016/j.cesx.2021.100097. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z.; Bera S.; Fan C.; Hu X. Streamlined Alkylation via Nickel-Hydride-Catalyzed Hydrocarbonation of Alkenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022, 144, 7015–7029. 10.1021/jacs.1c13482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Land E. J. Extinction Coefficients of Triplet-Triplet Transitions. Proc. R. Soc. London, Ser. A 1968, 305, 457–471. 10.1098/rspa.1968.0127. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Naguib Y. M. A.; Steel C.; Cohen S. G.; Young M. A. Photoreduction of Benzophenone by Acetonitrile: Correlation of Rates of Hydrogen Abstraction from RH with the Ionization Potentials of the Radicals R•. J. Phys. Chem. A 1987, 91, 3033–3036. 10.1021/j100295a078. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chilton J.; Giering L.; Steel C. The Effect of Transient Photoproducts in Benzophenone-Hydrogen Donor Systems. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1976, 98, 1865–1870. 10.1021/ja00423a036. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lalevée J.; Allonas X.; Fouassier J. P. Tris(Trimethylsilyl)Silane (TTMSS)-Derived Radical Reactivity toward Alkenes: A Combined Quantum Mechanical and Laser Flash Photolysis Study. J. Org. Chem. 2007, 72, 6434–6439. 10.1021/jo0706473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakamoto M.; Cai X.; Hara M.; Tojo S.; Fujitsuka M.; Majima T. Transient Absorption Spectra and Lifetimes of Benzophenone Ketyl Radicals in the Excited State. J. Phys. Chem. A 2004, 108, 8147–8150. 10.1021/jp047058a. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kancherla R.; Muralirajan K.; Maity B.; Karuthedath S.; Kumar G. S.; Laquai F.; Cavallo L.; Rueping M. Mechanistic Insights into Photochemical Nickel-Catalyzed Cross-Couplings Enabled by Energy Transfer. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 2737 10.1038/s41467-022-30278-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kariofillis S. K.; Jiang S.; Żurański A. M.; Gandhi S. S.; Martinez Alvarado J. I.; Doyle A. G. Using Data Science To Guide Aryl Bromide Substrate Scope Analysis in a Ni/Photoredox-Catalyzed Cross-Coupling with Acetals as Alcohol-Derived Radical Sources. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022, 144, 1045–1055. 10.1021/jacs.1c12203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonciolini S.; Noël T.; Capaldo L. Synthetic Applications of Photocatalyzed Halogen-Radical Mediated Hydrogen Atom Transfer for C–H Bond Functionalization. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2022, e202200417 10.1002/ejoc.202200417. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Simmons E. M.; Hartwig J. F. On the Interpretation of Deuterium Kinetic Isotope Effects in C–H Bond Functionalizations by Transition-Metal Complexes. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2012, 51, 3066–3072. 10.1002/anie.201107334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovett G. H.; Chen S.; Xue X.-S.; Houk K. N.; MacMillan D. W. C. Open-Shell Fluorination of Alkyl Bromides: Unexpected Selectivity in a Silyl Radical-Mediated Chain Process. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 20031–20036. 10.1021/jacs.9b11434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griller D.; Ingold K. U. Free-Radical Clocks. Acc. Chem. Res. 1980, 13, 317–323. 10.1021/ar50153a004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Lin Q.; Diao T. Mechanism of Ni-Catalyzed Reductive 1,2-Dicarbofunctionalization of Alkenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 17937–17948. 10.1021/jacs.9b10026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Biswas S.; Weix D. J. Mechanism and Selectivity in Nickel-Catalyzed Cross-Electrophile Coupling of Aryl Halides with Alkyl Halides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 16192–16197. 10.1021/ja407589e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Buzzetti L.; Crisenza G. E. M.; Melchiorre P. Mechanistic Studies in Photocatalysis. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 3730–3747. 10.1002/anie.201809984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Cismesia M. A.; Yoon T. P. Characterizing Chain Processes in Visible Light Photoredox Catalysis. Chem. Sci. 2015, 6, 5426–5434. 10.1039/C5SC02185E. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.