ABSTRACT

FliA (also known as σ28), a member of the bacterial σ70 family of transcription factors, directs RNA polymerase to flagellar late (class 3) promoters and initiates transcription. FliA has been studied in several bacteria, yet its role in spirochetes has not been established. In this report, we identify and functionally characterize a FliA homolog (TDE2683) in the oral spirochete Treponema denticola. Computational, genetic, and biochemical analyses demonstrated that TDE2683 has a structure similar to that of the σ28 of Escherichia coli, binds to σ28-dependent promoters, and can functionally replace the σ28 of E. coli. However, unlike its counterparts from other bacteria, TDE2683 cannot be deleted, suggesting its essential role in the survival of T. denticola. In vitro site-directed mutagenesis revealed that E221 and V231, two conserved residues in the σ4 region of σ28, are indispensable for the binding activity of TDE2683 to the σ28-dependent promoter. We then mutated these two residues in T. denticola and found that the mutations impair the expression of flagellin and chemotaxis genes and bacterial motility as well. Cryo-electron tomography analysis further revealed that the mutations disrupt the flagellar symmetry (i.e., number and placement) of T. denticola. Collectively, these results indicate that TDE2683 is a σ28 transcription factor that regulates the class 3 gene expression and controls the flagellar symmetry of T. denticola. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report establishing the functionality of FliA in spirochetes.

IMPORTANCE Spirochetes are a group of medically important but understudied bacteria. One of the unique aspects of spirochetes is that they have periplasmic flagella (PF, also known as endoflagella) which give rise to their unique spiral shape and distinct swimming behaviors and play a critical role in the pathophysiology of spirochetes. PF are structurally similar to external flagella, but the underpinning mechanism that regulates PF biosynthesis and assembly remains largely unknown. By using the oral spirochete Treponema denticola as a model, this report provides several lines of evidence that FliA, a σ28 transcriptional factor, regulates the late flagellin gene (class 3) expression, PF assembly, and flagellar symmetry as well, which provides insights into flagellar regulation and opens an avenue to investigate the role of σ28 in spirochetes.

KEYWORDS: spirochetes, Treponema, flagella, motility, sigma factors

INTRODUCTION

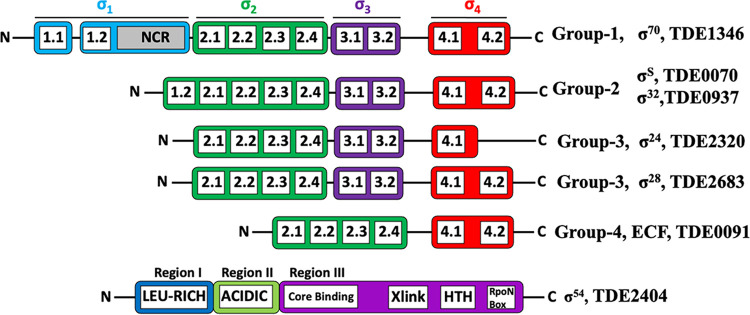

Multisubunit (α2ββ′ω) DNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RNAP) is the core enzyme for transcription initiation, the first step of gene expression in cells (1, 2). The core enzyme is evolutionarily conserved; however, bacterial RNAP is unable to specifically initiate transcription alone and thus depends on several sigma factors (σs) for transcription initiation. Mechanistically, σs recruit the RNAP complex to a promoter by recognizing specific consensus sequences and then form a holoenzyme to initiate transcription by isomerizing the RNAP-σ-promoter complex from a closed to an open state (1, 3–5). Based on their distinct structures and mechanisms, bacterial σs are classified into two main families: σ54- and σ70-type factors. The latter is further divided into four phylogenetically and structurally distinct groups (1, 6). Group 1 σs contain domains σ1, σ2, σ3, and σ4; group 2 σs are similar to group 1 but they lack the σ1.1 subdomain; group 3 σs harbor domains σ2, σ3, and σ4; and group 4, or extracytoplasmic function (ECF), σs have only domains σ2 and σ4. The domains σ2, σ3, and σ4, but not σ1, all possess a helix-turn-helix (HTH) DNA-binding module that recognizes different consensus sequences in a promoter: σ4, −35 motif; σ3, extended −10 motif; and σ2, −10 and discriminator motifs. Group 1 σs (e.g., σ70) are also known as primary or housekeeping σs because they are essential for bacterial growth. In contrast, the other three groups are not essential and thus are often referred to as alternative σs (1, 6).

FliA (also known as σ28 or σF in Escherichia coli and Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium and σD in Bacillus subtilis) is the most widely distributed alternative σ factor that targets RNAP to flagellar late (class 3) promoters in a wide range of motile bacteria (1, 2, 6). It has been functionally and structurally characterized in the paradigm models of E. coli and S. Typhimurium (7, 8). FliA lacks the σ1 domain but aligns well with the σ2, σ3, and σ4 domains of group 1 σs (8, 9). FliA targets the RNAP complex to specific promoters and forms a holoenzyme to initiate the transcription of class 3 genes, such as fliC and tar (8, 10). Therefore, FliA is often known as a flagellum-specific σ factor. The activity of FliA is regulated in response to flagellar assembly by FlgM, an anti-σ28 factor, which sequesters FliA by forming a 1:1 complex in the cytoplasm. Upon completion of the flagellar hook, the hook-basal body complex (HBB) provides an export route for FlgM. As FlgM exits the cell, FliA is free to act (11–13). A similar regulatory scheme is also found in other motile bacteria, such as Campylobacter jejuni (14), Helicobacter pylori (15, 16), Pseudomonas aeruginosa (17), Vibrio cholerae (18), and B. subtilis (2, 19). In these bacteria, deletions of fliA often lead to mutants that are nonflagellated and nonmotile, highlighting its essential role in bacterial flagellar synthesis and motility (16, 18, 20–22).

Spirochetes are a group of bacteria that can be readily recognized by their flat-wave or coiled-cell morphology and distinct form of corkscrew-like motility (23–25). They are responsible for several human diseases, including Lyme disease (Borrelia burgdorferi), syphilis (Treponema pallidum), leptospirosis (Leptospira interrogans), and periodontal disease (Treponema denticola) (26–29). Unlike external flagellates, spirochetes swim by means of rotating two bundles of periplasmic flagella (PF) that reside between the outer membrane and cell cylinder (23, 30). The number and length of PF vary from species to species. In general, spirochetal PF are structurally similar to the flagella of other bacteria, as they consist of a basal body-motor complex, a hook, and a filament (31). However, accumulating evidence suggests that spirochetes have evolved unique and complex mechanisms to regulate their flagellar gene expression and assembly. For example, B. burgdorferi has no homologs of FliA or FlgM and primarily depends on the housekeeping σ70 to control its flagellar and chemotaxis gene expression (23). Most spirochetes have multiple flagellin genes (23, 30). For instance, the flagellar filaments of T. denticola, T. pallidum, and Brachyspira hyodysenteriae are composed of at least one sheath protein (FlaA) and three core FlaB proteins (32–36). Of note, FlaBs are homologs of FliC. FlaA proteins are unique to spirochetes and do not share sequence similarity to bacterial flagellin proteins. In addition, FlaA proteins are not exported through the flagellar type III secretion system (fT3SS) as other flagellar proteins are. Instead, they are likely exported to the periplasmic space by the type II secretion pathway (30, 34). Interestingly, our previous studies indicate that the genes encoding these proteins are regulated by different promoters (32, 35). For instance, a conserved σ28-dependent promoter is mapped upstream of flaB2, and a σ70-dependent promoter is mapped upstream of flaA and flaB1 of T. denticola (32). A similar scenario is also found in B. hyodysenteriae and T. pallidum (37–39). However, while σ28-dependent promoters have been reported in several spirochetes (35, 40, 41), σ28 transcription factors have not yet been functionally characterized. In this study, TDE2683, a homolog of FliA, was first identified in T. denticola, a keystone pathogen of human periodontitis (29), and then its function as a σ28 was established using an approach combining bioinformatics, genetics, biochemistry, and cryo-electron tomography (cryo-ET). This report sets a benchmark for investigating the role of σ28 in spirochetes.

RESULTS

Classification of σs in T. denticola.

The genome of T. denticola ATCC 35405 encodes at least seven σs, including TDE0070 (275 amino acids [aa]; σ70/RpoD), TDE0091 (180 aa; σ24/RpoE), TDE0937 (286 aa; σ70/RpoD), TDE1346 (619 aa; σ70/RpoD), TDE2320 (213 aa; σ24), TDE2404 (463 aa; σ54/RpoN), and TDE2683 (262 aa; σ27/WhiG) (42). BLAST search and sequence comparisons revealed that, among the three putative σ70 factors, TDE1346 is a bona fide σ70 because it contains all four functional domains (σ1, σ2, σ3, and σ4) in the group 1 σs (Fig. 1; also, see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material). TDE0070 and TDE0937 harbor σ2, σ3, σ4, and one part of σ1 (σ1.2). A BLAST search showed that TDE0937 has 30% sequence identity and 53% similarity to the E. coli σ32 (RpoH), which regulates the expression of heat shock protein (43). TDE0070 is a homolog of RpoS; e.g., it has 35% shared sequence identity and 59% similarity to the RpoS of B. burgdorferi. RpoS is an alternative σ factor that regulates general stress responses such as oxidation, starvation, and change of host (44, 45). For instance, B. burgdorferi RpoS is a gatekeeper that regulates the expression of genes for stress responses and tick-to-mammal transmission (46). Therefore, TDE0070 likely functions as an alternative σ to control the stress response of T. denticola. TDE0091 contains only the σ2 and σ4 domains and thus likely belongs to the group 4 ECF σs (Fig. 1). Both TDE2320 and TDE2683 belong to the group 3 σs, which have σ2, σ3, and σ4 domains; however, one part of σ4 (σ4.2) is absent in TDE2320 (Fig. 1 and Fig. S3). In contrast, TDE2683 contains all the domains that are possessed by the group 3 σs, such as σ28. Therefore, between these two σs, TDE2683 more likely functions as σ28.

FIG 1.

Schematic illustration of σs in T. denticola. These factors are annotated in the genome of T. denticola (42). Individual domains in these σ factors were identified by BLAST (Fig. S3) and SMART searches and then aligned to their counterparts (i.e., σ70, σ28, and σ54) from E. coli and other bacteria (1, 4–6, 8, 10, 90, 91).

Identification of a FliA homolog in T. denticola.

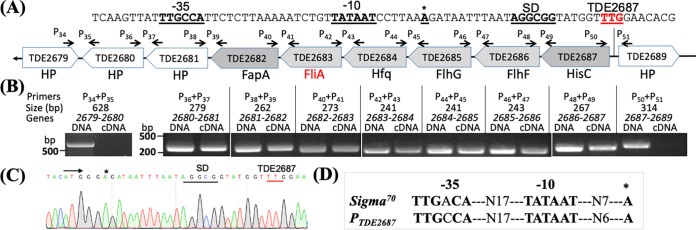

TDE2683 consists of 262 aa with a predicted molecular weight (MW) of 29.95 kDa. It resides in a gene cluster composed of eight open reading frames (ORFs): TDE2687 (HisC), TDE2686 (FlhF), TDE2685 (FlhG), TDE2684 (hypothetical protein [HP]), TDE2683 (WhiG/σ27), TDE2682 (FapA), TDE2681 (HP), and TDE2680 (HP) (Fig. 2). HisC belongs to the family of histidinol phosphate aminotransferases (47); FlhF and FlhG are two small GTPases that regulate flagellar number and placement in polar flagellates such as C. jejuni and B. burgdorferi (48, 49). A PSI-BLAST search revealed that the N terminus of TDE2684 (222 aa) shares 35% (21 of 60 aa) sequence identity with B. burgdorferi Hfq (50), a global regulatory RNA-binding protein, and TDE2682 is a homolog of FapA (flagellar assembly protein A), which controls the flagellar localization of Vibrio vulnificus (51, 52). Co-reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) analysis showed that TDE2683, four genes upstream, and three genes downstream are cotranscribed, but not TDE2679 and TDE2689, two genes in the opposite direction (Fig. 2A and B). We then mapped the transcription start site (TSS) using 5′ rapid amplification of cDNA ends (RACE) and found that the −10 and −35 regions contain a well-conserved σ70-dependent promoter (TTGCCA-N17-TATAAT-N6-A) which is 23 bp from the start codon of TDE2687 (Fig. 2), suggesting that this gene cluster is controlled by σ70.

FIG 2.

TDE2683 is located at a large gene cluster regulated by a σ70 promoter. (A) Diagram showing the genes adjacent to TDE2683. Arrows represent the relative positions and orientations of RT-PCR primers that span the intergenic regions between individual ORFs. (B) RT-PCR analysis. For each pair of primers, chromosomal DNA was used as a positive control. The numbers below the primers are predicted sizes of RT-PCR and PCR products. (C) 5′ RACE analysis. The arrow shows the sequencing direction, and an asterisk indicates the transcriptional start site. (D) Sequence comparison between the E. coli σ70 promoter and the promoter sequence identified upstream of TDE2687 (designated PTDE2687).

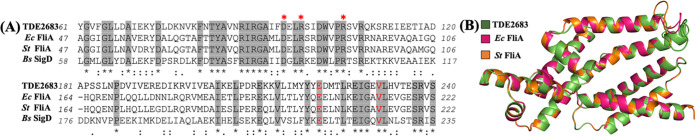

TDE2683 is annotated as σ27/WhiG in the genome of T. denticola (42). Recent studies showed that WhiG, an ortholog of bacterial FliA or σ28, regulates multicellular differentiation (e.g., sporulation) of Streptomyces (53, 54). In addition, domain composition analysis showed that TDE2683 belongs to the group 3 σs (Fig. 1 and Fig. S3). Therefore, we reasoned that TDE2683 is a FliA homolog. To test this hypothesis, we first searched the NCBI protein database using TDE2683 as a query and found that it belongs to the family of WhiG/FliA (TIG02479). We then carried out multisequence alignment (Fig. 3A), including FliA proteins of E. coli and S. Typhimurium and SigD (an ortholog of FliA) of Bacillus subtilis (19), and found that TDE2683 shares 39 to 44% sequence identity with these three proteins. Previous phylogenetic and structural studies showed that the family of σ28 factors contains three invariable residues, i.e., D81, R84, and R91 in the FliA of E. coli (FliAEc), which form a binding site for −10 regions (GCCGATAA) in σ28-dependent promoters, such as fliC and tar promoters in E. coli (8, 10, 55, 56). Like FliAEc, TDE2683 also has these three invariable residues (D95, R98, and R105). The structure of FliAEc and S. Typhimurium FliA (FliASt) was solved (8). Using these two proteins as a structural template, we conducted homolog modeling and found that TDE2683 has a structure similar to that of FliAEc and FliASt (Fig. 3B); i.e., they all possess 10 α-helixes (H1 to H10) that form three functional domains, σ2 (H1 to H3), σ3 (H4 to H6), and σ4 (H7 to H10) (Fig. 3B), linked by variable disordered loops (8). Together, sequence and structural comparison analyses indicate that TDE2683 is a FliA homolog, and it is referred to here as FliATd.

FIG 3.

TDE2683 is a homolog of FliA. (A) Sequence alignment of FliA homologs. TDE2683 (WP_002667112) is aligned with E. coli FliA (NP_416432), S. Typhimurium FliA (NP_460909), and B. subtilis SigD (WP_187704716). Only partial alignment is shown. Asterisks represent three invariable residues in the family of FliA. The residues in red are to be mutated. The alignment was analyzed using Clustal Omega. (B) Homology modeling shows that TDE2683 (FliATd) has structural topology similar to that of the FliA proteins (σ28) of E. coli and S. Typhimurium. The figure was generated by the Swiss-Model server using FliAEc (PDB ID 1SC5) (8) as a template.

FliATd can substitute for the function of FliAEc.

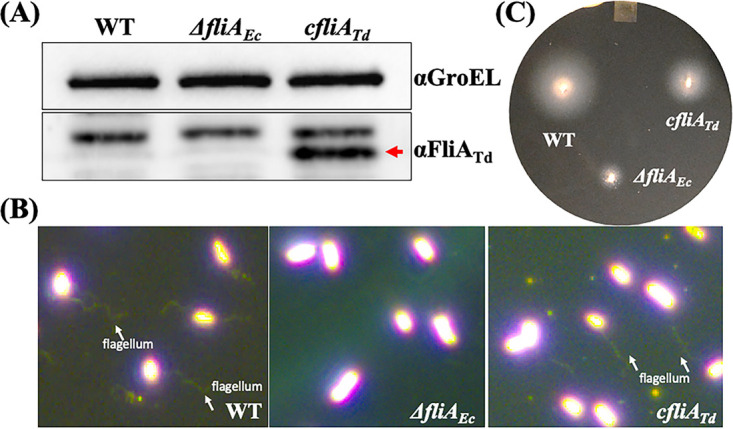

σ28 factors are evolutionarily conserved and functionally interchangeable across different bacterial species (2, 18, 57). For example, SigD, a σ28 ortholog in B. subtilis, can substitute for the function of FliAEc (19). To determine if the same scenario occurs with FliATd, a heterologous gene replacement was conducted. To this end, we replaced the entire fliAEc in frame with fliATd, and the resultant strain was designated the cfliATd strain. As a control, we constructed a fliAEc deletion (ΔfliAEc) mutant. Both ΔfliAEc and cfliATd were confirmed by PCR and immunoblotting using a specific antibody against FliATd. Immunoblotting analyses showed that fliATd was successfully expressed in the cfliATd strain (Fig. 4A). Flagellar staining and swimming plate assays showed that the ΔfliAEc mutant was unable to assemble flagellar filaments and failed to swim out in 0.4% soft-agar plates. In contrast, the cfliATd strain was still motile and able to assemble flagella (Fig. 4B and C), suggesting that FliATd can substitute, at least in part, for the function of FliAEc in E. coli. This study aligns with the above-described sequence and structural analyses and provides the first line of experimental evidence that FliATd has a function similar to that of FliAEC.

FIG 4.

FliATd substitutes for the function of FliAEc in E. coli. (A) Detection of FliATd in E. coli by immunoblotting analysis. For this experiment, equivalent amounts (~10 μg) of whole-cell lysates of three E. coli strains were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and then probed with specific antibodies against E. coli GroEL (αGroEL) and T. denticola FliA (αFliATd). GroEL was used as a loading control. WT, E. coli DH5α; ΔfliAEc, fliA deletion mutant of E. coli; cfliATd, engineered E. coli strain in which the entire fliAEc gene was replaced in frame with fliATd. (B) Visualization of E. coli flagella. E. coli cells were first stained with Ryu as previously described (82) and then visualized under dark-field illumination at ×100 magnification using a Zeiss Axiostar Plus microscope. (C) Swimming plate assay. This assay was carried out on swimming plates containing 1% tryptone, 1% NaCl, and 0.4% Bacto agar, as previously documented (87). The plates were incubated at 37°C overnight.

FliATd binds to σ28-dependent promoters.

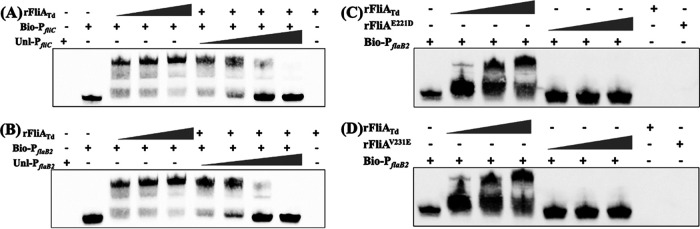

σ28 recognizes a promoter through interactions with specific consensus sequences at −10 and −35 regions (1, 58, 59). PfliC, a promoter that initiates the expression of fliC in E. coli and S. Typhimurium, is a well-characterized σ28-dependent promoter (60, 61). We recently found that the flaB2 gene of T. denticola is controlled by the σ28-dependent promoter PflaB2 (32). Both promoters contain a conserved σ28 binding site at their −10 (CGGATAA) and −35 (TA/TAA) regions. Using these two promoters as surrogates, we carried out electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSA) to determine if FliATd binds to σ28-dependent promoters. EMSA showed that the recombinant FliATd protein (rFliATd) bound to biotin-labeled PfliC and PflaB2 in a dose-dependent manner, which was competed out upon addition of unlabeled DNA probes (Fig. 5A and B). To further confirm that the observed binding is specific, we mutated E221 and V231, two conserved residues in the σ4 domain of σ28 factors (55, 56), by using site-directed mutagenesis and found that two mutated recombinant proteins (E221D and V231E) were unable to bind to PfliC and PflaB2 (Fig. 5C and D). This study provides the second line of experimental evidence that FliATd binds to the σ28-dependent promoters.

FIG 5.

EMSA shows that FliATd binds to two σ28-dependent promoters. (A) EMSA using E. coli fliC promoter (PfliC) as a DNA probe. For this assay, biotin-labeled PfliC (Bio-PfliC) was incubated with increasing amounts of wild-type FliATd recombinant protein (rFliATd) and titrated with increasing concentrations of unlabeled PfliC (Unl-PfliC). (B to D) EMSA using T. denticola flaB2 promoter (PflaB2) as a DNA probe. Biotin-labeled PflaB2 (Bio-PflaB2) was incubated with increasing amounts of rFliATd (B) or two mutated recombinant proteins, rFliAE221D (C) and rFliAV231E (D), and competed out with increasing concentrations of unlabeled PflaB2 (Unl-PflaB2).

FliATd controls the expression of flagellar filament and chemotaxis genes in T. denticola.

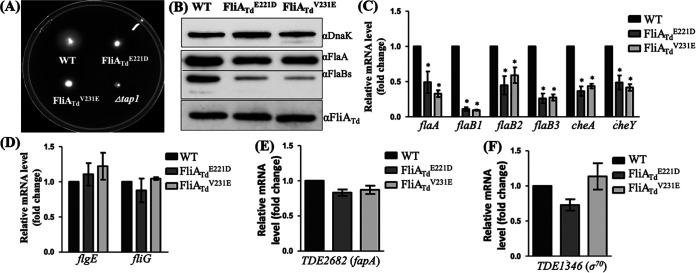

To investigate the role of FliATd, we sought to delete this gene in T. denticola via allelic exchange. Despite different constructs (deletions versus insertions), antibiotic resistant markers (erythromycin versus gentamicin), and transformations (electroporation versus heat shock) attempted, we were unable to delete fliATd, suggesting that it is essential for T. denticola. To circumvent this issue, we mutated E221 and V231 of FliATd in T. denticola, because the above-described EMSA study shows that these two residues are essential for its binding activity to the σ28-dependnet promoter. To this end, we replaced wild-type fliATd in frame with two mutated genes (E221D and V231E) along with an erythromycin cassette (ermB) (62). Erythromycin-resistant colonies that appeared on the plates were first screened by PCR for the presence of ermB. Positive colonies were then subjected to PCR and DNA sequencing to confirm two site-directed mutations in fliATd. The results showed that E221 and V231 were mutated as designed, and the two obtained mutants were designated FliATdE221D and FliATdV231E mutants. To investigate the role of FliATd, we first carried out swimming plate assays and found that the swimming rings (n = 12 plates) formed by the FliATdE221D (11.67 ± 0.61 mm) and FliATdV231E (14.37 ± 0.68 mm) mutants are significantly (P < 0.05) smaller than those of the wild type (19.42 ± 0.25 mm) but larger than those of the Δtap1 strain (4.38 ± 0.13 mm), a previously constructed nonmotile mutant (63) (Fig. 6A), indicating that the motility of these two mutants is impaired.

FIG 6.

Characterizations of two fliATd site-directed mutants of T. denticola. (A) Swimming plate assay of WT, FliATdE221D, and FliATdV231E strains. This assay was carried out on 0.35% agarose plates containing TYGVS medium diluted 1:5 with PBS. The plates were incubated anaerobically at 37°C for 5 days. A nonmotile Δtap1 mutant was used as a control to determine initial inoculum sizes. (B) Immunoblotting analysis of WT, FliATdE221D, and FliATdV231E strains. Equivalent amounts of whole-cell lysates were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and then probed with specific antibodies to DnaK, FlaA, and FlaBs. DnaK was used as a loading control. (C to F) qRT-PCR analysis of WT, FliATdE221D, and FliATdV231E strains. For this experiment, the levels of four flagellar filament genes (flaA, flaB1, flaB2, and flaB3), two chemotaxis genes (cheA and cheY), two flagellar genes (flgE and fliG), TDE2682 (fapA), and TDE1346 (σ70) were measured by qRT-PCR, as previously described (33). The dnaK gene transcript was used as an internal control to normalize the readouts of qRT-PCR. The results are expressed as the level of individual gene transcripts in two mutants relative to that in WT. *, P < 0.05.

We next assessed the role of FliATd in the expression of flagellin genes in T. denticola using immunoblotting and quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) analyses. Notably, unlike E. coli and S. Typhimurium, which have a single flagellin protein, T. denticola has multiple flagellin proteins, including FlaB1, FlaB2, and FlaB3, and a sheath protein, FlaA (33, 42, 64). Immunoblotting analysis revealed that the levels of FlaA and three FlaBs in both the FliATdE221D and FliATdV231E mutants were significantly decreased (Fig. 6B). Densitometry analysis showed that compared to the wild type, FlaA and three FlaB proteins in these two mutants decreased ~40% and ~90%, respectively. qRT-PCR analysis further demonstrated that the reduction of FlaA and three FlaBs in these two mutants mainly occurred at the transcriptional level (Fig. 6C). In addition to the four flagellar filament genes, qRT-PCR analysis showed that the transcription of cheA and cheY, two chemotaxis genes, in FliATdE221D and FliATdV231E was also decreased (Fig. 6B). We also measured the transcription of flgE (hook) and fliG (C ring), two genes that belong to class 2 in the flagellar transcriptional regulatory cascade (13), and found that their transcripts had no significant changes in the two mutants (Fig. 6D). These results indicate that FliATd controls the expression of class 3 flagellin and chemotaxis genes in T. denticola. In addition, qRT-PCR analysis demonstrated that the transcription of TDE2682 (fapA), a gene immediately downstream of fliATd, was not affected (Fig. 6E), indicating that the insertion of ermB has no polar effect on its downstream gene expression in these two mutants.

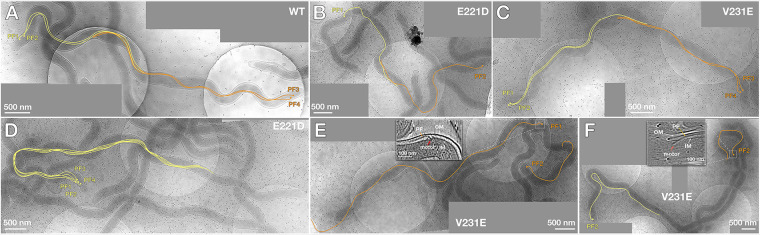

FliATd controls the flagellar symmetry of T. denticola.

The above-described immunoblotting analysis showed that the levels of four flagellar filament proteins are significantly impaired in both FliATdE221D and FliATdV231E. To determine if this impairment affects flagellar filament assembly, we conducted in situ whole-cell cryo-ET analysis. Cryo-ET revealed that two mutants are still able to assemble PF, even though the levels of the four flagellar filament proteins were substantially attenuated (Fig. 6B). Interestingly, the number and placement of PF in these two mutants became abnormal (Fig. 7 and Table 1). The wild-type cells uniformly have bipolar flagella (two PF at both cell poles), which form a ribbon-like structure wrapping around the cell cylinder (Fig. 7A). In contrast, two mutants were diverse in terms of flagellar number and placement (Fig. 7B to F); e.g., some mutant cells had multiple PF at one end (lophotrichous) (Fig. 7D) or a single flagellum at both ends (amphitrichous) (Fig. 7B). Some mutant cells even had lateral rather than polar flagella (Fig. 7B). In addition, the PF in these two mutants became disarrayed and were unable to form a ribbon-like structure (Fig. 7). Moreover, cells of the FliATdE221D (9.7 ± 1.2 μm, n = 3 cells) and FliATdV231E (10.1 ± 4.1 μm, n = 4 cells) strains appeared to be longer than wild-type cells (7.1 ± 0.30 μm, n = 3 cells). These results indicate that mutations of FliATd somehow disrupt the symmetric arrangement of PF and alter the cell length of T. denticola.

FIG 7.

Whole-cell cryo-ET analysis of T. denticola wild type and two mutants. (A) Projection image of a WT cell; (B to F) projection images of FliATdE221D and FliATdV231E mutant cells. PF originating from one end are colored in yellow, and those from the opposite end are in orange. The boxed images in panel E and F show the detailed structure of PF and flagellar protrusions. PF, periplasmic flagella; OM, outer membrane; IM, inner membrane. Each panel was generated by combining multiple high-resolution cryo-ET images; the image contrast is different among these data.

TABLE 1.

Whole-cell cryo-ET analysis of T. denticola wild type and two site-directed mutants

| Strain and cell | Cell length (μm) | Flagellar length (μm) | Flagellar no.a |

|---|---|---|---|

| WT | |||

| 1 | 6.9 | 3.4 | 2 |

| 3.5 | |||

| 4.6 | 2 | ||

| 4.6 | |||

| 2 | 7.3 | 6.1 | 2 |

| 4.8 | |||

| 2.1 | 2 | ||

| 2.1 | |||

| 3 | 7.0 | 5.0 | 2 |

| 5.5 | |||

| 2.5 | 2 | ||

| 3.5 | |||

| Avg | 7.1 | 4.0 | |

| FliAE221D mutant | |||

| 1 | 11.1 | 4.0 | 2 |

| 4.9 | |||

| —b | — | ||

| 2 | 9.2 | 6.3 | 4 |

| 6.7 | |||

| 6.3 | |||

| 5.6 | |||

| 3 | 8.8 | 3.5 | 1 |

| 4.7 | 1 | ||

| Avg | 9.7 | 3.5 | |

| FliAV231E mutant | |||

| 1 | 13.0 | 5.0 | 1 |

| 2.9 | 1 | ||

| 2 | 7.2 | 2.9 | 2 |

| 3.3 | |||

| 3.3 | 2 | ||

| 3.2 | |||

| 3 | 10.2 | 2.2 | 2 |

| 7.2 | |||

| — | — | ||

| 4 | 10.7 | 3.1 | 1 |

| — | — | ||

| Avg | 10.3 | 2.1 |

Number of flagellar filaments visualized at the cell poles.

—, indicates that there is no PF detected by cryo-EM.

DISCUSSION

Due to high sequence similarity, σ28 factors such as FliA are often misannotated as other members in the family of σ70 factors (1, 6). This probably explains why TDE2683 is annotated as σ27/WhiG (42). By combining bioinformatics, heterologous complementation, biochemistry, site-directed mutagenesis, and cryo-ET, this report provides several lines of coherent evidence that TDE2683 functions as a flagellum-specific σ28 that regulates the expression of flagellar class 3 genes in T. denticola. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report to establish the role of FliA as a flagellum-specific σ28 in spirochetes. In the flagellar transcription hierarchy of E. coli and S. Typhimurium, FliA and FlgM act collaboratively to regulate flagellar late-gene transcription (65, 66). Identification of FliATd indicates that a similar regulatory mechanism exists in T. denticola, yet there has been no FlgM annotated in its genome. We searched the genome of T. denticola for FlgM homologs. A BLASTP search did not find any, but a DELTA-BLAST search revealed that TDE0201, a small hypothetical protein of 93 aa, has 17% shared sequence identity to E. coli FlgM. We are currently conducting biochemical and loss-of-function studies to determine if TDE0201 functions as FlgM. We then extended our search for the presence of FliA and FlgM to other spirochetes and found their homologs in most spirochetes, including T. pallidum, L. interrogans, and B. hyodysenteriae, suggesting that these spirochetes may also employ FliA and FlgM to regulate their flagellar biosynthesis. In line with our previous reports, there are neither FliA nor FlgM homologs identified in the genus Borrelia, supporting the idea that this group of spirochetes is an outlier that has evolved unique mechanisms to regulate their flagellar synthesis and assembly (23, 67, 68).

In some bacterial pathogens, FliA is required for virulence and in vivo fitness (69–73). However, to the best of our knowledge, there has been no prior report that FliA, an alternative σ factor, is essential for bacterial growth in vitro. It was therefore totally unexpected that we were unable to delete fliATd via allelic exchange despite the fact that different methods were attempted. In contrast, we were able to delete TDE2682, a gene immediately downstream of fliATd. In addition, we were able to replace fliATd in frame with two site-directed mutants, fliATdE221D and fliATdV231E, via allelic exchange. The success of these two experiments ruled out the possibility that the inability to delete fliATd is due to a polar effect on downstream gene expression caused by insertions of antibiotic cassettes. Moreover, the family of σ28 factors contains three invariable residues, i.e., D81, R84, and R91 in FliAEc and D95, R98, and R105 in FliATd (8, 9). Previous mutagenesis and structural analyses demonstrate that these three residues form a binding site for −10 regions (GCCGATAA) in σ28-dependent promoters, such as fliC and tar promoters in E. coli (55). Thus, they are absolutely required for the function of σ28 factors. We also attempted to mutate these three residues in T. denticola; however, this attempt failed. By using the same method, we successfully mutated E221 and V231, two residues in the σ4 domain that binds to −35 regions in σ28-dependent promoters. Previous studies showed that substitutions of these two residues partly impair the function of FliAEc and FliASt (55, 56). A similar scenario might occur in FliATd, which allows us to mutate these two residues in T. denticola. Taking these results together, we posit that fliATd is essential for T. denticola growth. If so, how does this occur? T. denticola has two long PF that arise from the cell poles and extend along the cell cylinder. Due to this unique structure, T. denticola must couple its flagellar biosynthesis and elongation to cell division. It is possible that FliATd also functions as a regulator to synchronize these two processes. If this is the case, deletion of fliATd may perturb this synchronization, in turn arresting cell division and/or leading to cell lysis. In line with this speculation, we found that two site-directed mutants of fliATd grew slightly more slowly than the wild type (Fig. S4) and had disarrayed and misplaced PF, some of which even protruded from the cell membrane (Fig. 7F). Flagellar protrusions may disrupt the cell membrane and lead to cell lysis. We are currently attempting to construct a conditional knockout of fliATd using a thiamine-inducible promoter we previously identified (74). If this undertaking is successful, this mutant will allow us to decipher the role of FliATd in regulation of flagellar biosynthesis and cell division of T. denticola.

As mentioned in the introduction, the flagellar filaments of T. denticola are composed of at least four proteins: FlaA, FlaB1, FlaB2, and FlaB3. Among these four proteins, the gene encoding FlaB2 is regulated by a σ28-dependent promoter (32). Consistent with this result, we found that the expression level of flaB2 is impaired in the FliATdE221D and FliATdV231E mutants. Surprisingly, immunoblotting and qRT-PCR analyses also showed that the levels of flaA, flaB1, and flaB3, three genes controlled by a σ70-dependent promoter, are also attenuated in these two mutants (Fig. 6B and C). We repeated these two experiments using three sets of samples that were harvested at different growth phases of T. denticola and obtained similar results. FliATdE221D and FliATdV231E were constructed by replacing fliATd in frame with two mutated genes along with ermB, which is used as a selection marker. It is therefore possible that insertion of ermB has a polar effect on downstream gene expression that, in turn, affects the expression of three flagellin genes. To rule out this possibility, we measured the expression of TDE2682, a gene immediately downstream of fliATd, by qRT-PCR and found that it remained unchanged in two mutants (Fig. 6E). We also measured the expression of TDE1346, a putative σ70 factor, by qRT-PCR and found that it was not affected either (Fig. 6F). WhiG is a sporulation-specific σ28 of Streptomyces (53). Two recent reports showed that the signaling molecule cyclic di-GMP (c-di-GMP) controls the differentiation of hyphae into spores by arming RsiG, an anti-σ of WhiG (53, 54). FliATd and WhiG share 49% sequence identity. In addition, T. denticola has a complex c-di-GMP signaling pathway, and previous studies by us and others showed that c-di-GMP plays a critical role in the motility and virulence of T. denticola (42, 75–77). Thus, it is possible that there is a cross talk between the c-di-GMP signaling pathway and FliATd. If this is true, mutations in FliATd may perturb the signaling pathway of c-di-GMP that in turn affects the expression of flaA, flaB1, and flaB3 either directly or indirectly. Alternatively, FliATd may control the expression of these three genes by modulating other signaling pathways, such as bacterial two-component systems (TCS). For instance, C. jejuni and H. pylori have no FlhC and FlhD, two master regulators in the flagellar regulatory transcription cascade, and have evolved to control their flagellar gene expression using TCS (22). Like C. jejuni and H. pylori, FlhC and FlhD are absent in T. denticola (42). The genome of T. denticola encodes at least six pairs of TCS, including six histidine kinases and six response regulators, and their roles remain largely unknown. It is possible that there is an interplay between FliATd and some of these TCS signaling pathways. We are currently investigating these possibilities.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, culture conditions, and oligonucleotide primers.

T. denticola ATCC 35405 (wild type [WT]) was used in this study (42). Cells were grown in tryptone-yeast extract-gelatin-volatile fatty acids-serum (TYGVS) medium at 37°C in an anaerobic chamber in the presence of 85% nitrogen, 5% carbon dioxide, and 5% hydrogen (78). T. denticola isogenic mutants were grown with erythromycin (50 μg/mL) or/and gentamicin (20 μg/mL). Escherichia coli DH5α strain (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA) was used for DNA cloning; BL21-CodonPlus (DE3)-RIL (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA) was used for preparing recombinant proteins. E. coli strains were grown in lysogeny broth (LB) supplemented with appropriate concentrations of antibiotics for selective pressure as needed: erythromycin (400 μg/mL), kanamycin (50 μg/mL), chloramphenicol (50 μg/mL), and ampicillin (100 μg/mL). The oligonucleotide primers for PCR and RT-PCR used in this study are listed in Table S1. These primers were synthesized at IDT (Integrated DNA Technologies, Coralville, IA).

Gel electrophoresis and immunoblots.

Sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and immunoblotting analyses were carried out as previously described (33, 79). For immunoblotting, T. denticola cells were harvested at the mid-logarithmic phase (~5 × 108 cells/mL). Equal amounts of whole-cell lysates (~5 μg) were separated on SDS-PAGE and then transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes. Immunoblots were probed with specific antibodies against T. pallidum FlaBs and T. denticola FlaA and DnaK, as described in previous studies (64, 80). The antibody against T. denticola TDE2683 was generated in this study (see below for details). E. coli GroEL antibody was purchased from Abcam (Cambridge, United Kingdom). Immunoblots were developed using a horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody with an enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) luminol assay, and signals were quantified using the Molecular Imager ChemiDoc system with the Image Lab software (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA) (79).

Preparation of TDE2683 recombinant protein and antiserum.

The gene encoding the full-length TDE2683 protein was PCR amplified with primers P1/P2 using Pfx DNA polymerase (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY) and then cloned into the pET200/D-TOPO expression vector (Life Technologies), which encodes a six-histidine-tag (6×His) at the N terminus. The resulting plasmid was then transformed into BL21-CodonPlus (DE3)-RIL (Agilent). The expression of TDE2683 were induced using 1 mM isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactosidase (IPTG). For antiserum production, recombinant TDE2683 protein was purified using nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid (Ni-NTA) agarose (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) under denaturing conditions. For EMSA, recombinant TDE2683 protein was purified using Ni-NTA agarose under native conditions. The purified proteins were then dialyzed in a buffer containing 20 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 8) at 4°C overnight using 3.0-kDa-molecular-weight-cutoff Spectra/Por dialysis bags (Spectrum Laboratories, Rancho Dominguez, CA). The concentrations of purified proteins were determined using a Bio-Rad protein assay kit (Bio-Rad). For antibody production, 5 mg of purified recombinant TDE2683 was used to immunize two rats following a standard immunization procedure. The primers for preparation of recombinant proteins are listed in Table S1.

Heterologous replacement of fliAEc with TDE2683.

We first in frame replaced fliAEc with TDE2683 via allelic exchange using the vector illustrated in Fig. S1A. This vector was constructed by two-step PCR and DNA cloning. Herein, the fliAEc upstream region (UR) and the full-length TDE2683 gene were first PCR amplified with primers P3/P4 and P5/P6, respectively, and then fused with primers P3/P6, generating UR-TDE2683, which was then cloned into the pGEM-T Easy vector (Promega). Then, an erythromycin cassette (erm) (62, 81) and the fliAEc downstream region (DR) were PCR amplified with primers P7/P8 and P9/P10, respectively. The resultant DR fragment was then cloned into the pGEM-T Easy vector (Promega, Madison, WI), which was then released and ligated to the 3′ end of UR-TDE2683 at an engineered XbaI cut site. Then, the erm cassette was inserted into the obtained vector at an engineered XbaI cut site, generating the vector TDE2683-erm. The obtained construct was linearized and transformed into E. coli DH5α to replace fliAEc. The resultant erythromycin-resistant colonies were first screened for the presence of TDE2683 by PCR and then confirmed by immunoblotting with TDE2683 antibody. In parallel, a mutant with a deletion of fliAEc (ΔfliAEc) was constructed by replacing fliAEc in frame with a kanamycin cassette (kan), as depicted in Fig. S1B. The primers used here are listed in Table S1.

Flagella staining.

A previously described Ryu staining method was used to visualize E. coli flagella (82). In brief, E. coli cultures were grown at 37°C for 2 days without shaking. The cell culture was transferred onto a microscope slide using a loop and then covered with a coverslip. A drop of Ryu stain (Remel, San Diego, CA) was applied to the edge of the coverslip, and the slide was incubated at room temperature for 15 min. The cells were visualized under dark-field or phase-contrast microscopy using a Zeiss Axio Imager.A2 microscope.

EMSA.

EMSA were carried out as previously described with some modifications (83). In brief, the T. denticola flaB2 promoter (PflaB2) and E. coli fliC promoter (PfliC) (55, 60) were PCR amplified using P18/P19 and P20/P21, respectively. The obtained amplicons were labeled with biotin using a biotin DecaLabel DNA labeling kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) to generate two DNA probes. EMSA were performed by coincubating individual biotin-labeled DNA probes (2 nM) with increasing amounts of recombinant TDE2683 (6.4 μM, 12.9 μM, and 25.8 μM), or two mutated recombinant proteins (E221D and V231E), in a reaction buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5) at room temperature for 1 h. For each reaction, only one labeled DNA probe and one type of recombinant protein were included. For competition assays, increasing amounts of unlabeled DNA probes (20 nM, 40 nM, 200 nM, and 2 μM) were added to the reaction mixtures. Following the reactions, DNA loading dye was added. The resulting samples were then run on 4 to 20% Mini-Protean TGX gels (Bio-Rad Laboratories), which were then transferred to nylon membranes and cross-linked using UV light. Detections were performed using a chemiluminescent nucleic acid detection module kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The primers for the two DNA probes are listed in Table S1.

Site-directed mutagenesis.

Site-directed mutagenesis was performed using a Q5 site-directed mutagenesis kit (New England Biolabs) according to the manufacturer’s instruction. The plasmid that expresses TDE2683 recombinant protein was used as a template to replace Glu221 and Val231 with Asp and Glu, respectively, using primers P22/P23 and P24/P25. The resultant mutations were confirmed by DNA sequencing analysis.

Construction of two TDE2683 site-directed mutants in T. denticola.

The vector shown in Fig. S2 was constructed to replace the wild-type TDE2683 with two genes with site-directed mutations at amino acid E221 or V231 by using two-step PCR and DNA cloning, as previously documented (84). In brief, to make this construct, the downstream region of TDE2683 and the mutated gene, either E221D or V231E, were PCR amplified with primers P29/P30 and P5/P26, respectively, and then fused with primers P5/P30, generating fliATd-3′, which was then cloned into the pMD19 T-vector (TaKaRa Bio USA, Inc., Mountain View, CA). An erythromycin cassette (ermB) (62) was PCR amplified with primers P27/P28 and cloned into the pGEM-T Easy vector (Promega), which was then released and inserted into fliATd-3′ at a NotI cut site, generating TDE2683*-ermB, which was transformed into T. denticola wild-type competent cells via heat shock; cells were then plated on soft agars with erythromycin, as previously described (85). Site-directed mutations were confirmed by PCR, followed by DNA sequencing.

RNA preparation, RT-PCR, qRT-PCR, and 5′ RACE.

RNA isolation was performed as previously described (33, 79, 86). Briefly, T. denticola cells were harvested at the mid-logarithmic phase (~5 × 108 cells/mL). Total RNA was extracted using TRI reagent (Sigma-Aldrich), following the manufacturer's instructions. The resultant samples were treated with Turbo DNase I (Thermo Fisher Scientific) at 37°C for 2 h to eliminate genomic DNA contamination. The resultant RNA samples were re-extracted using acid phenol-chloroform (Ambion, Austin, TX), then precipitated in isopropanol, and finally washed once with 70% ethanol. The RNA pellets were resuspended in RNase-free water. cDNA was generated from the purified RNA (1 μg) using a SuperScript IV VILO cDNA synthesis kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific). qRT-PCR was performed using iQ SYBR green supermix and a QuantStudio 3 system (Applied Biosystems, Waltham, MA). The housekeeping gene dnaK (TDE0628) of T. denticola was used as an internal control to normalize the qRT-PCR data, as previously described (33). The results were expressed as the normalized difference in threshold cycle (ΔΔCT) between the wild-type and the mutant strains. 5′ RACE analysis was performed using the SMARTer RACE 5′/3′ kit (TaKaRa Bio USA), according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The primers for RT-PCR, qRT-PCR, and 5′ RACE are listed in Table S1.

Bacterial swimming plate assays.

Swimming plate assays of E. coli were performed on soft-agar plates containing 1% tryptone, 1% NaCl, and 0.4% Bacto agar, as previously described (87). In brief, overnight cultures were diluted to 1:100 and incubated at 37°C for 8 h with shaking. One microliter of the culture was inoculated onto the soft-agar plates and incubated at 37°C for 14 h. Swimming plate assays of T. denticola were performed as previously described (79). Briefly, 3 μL of cultures (109 cells/mL) were inoculated onto 0.35% agarose plates containing TYGVS medium diluted 1:5 with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). The plates were incubated anaerobically at 37°C for 5 days to allow the cells to swim. The diameters of the swim rings were measured in millimeters. As a negative control, a Δtap1 strain, a previously constructed T. denticola nonmotile mutant, was included to determine the initial inoculum size (63). The average diameters of each strain were calculated from four independent plates; the results are presented as means and standard errors of the means (SEM). The data were statistically analyzed by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison at a P value of <0.01.

Cryo-ET sample preparation, data collection, and image processing.

The frozen-hydrated specimens of T. denticola were prepared as previously described (33). Briefly, T. denticola cultures were mixed with 10-nm-colloidal-gold solutions and then deposited on a freshly glow-discharged, holey carbon grid for about 1 min. The grids were blotted with a piece of filter paper for ~4 s and then rapidly plunged into liquid ethane using a gravity-driven plunger apparatus. Frozen-hydrated specimens of T. denticola were transferred to a 300-kV Krios electron microscope (Thermo Fisher Scientific) equipped with a field emission gun and a K2 direct detection detector (Gatan). To generate three-dimensional (3D) reconstructions of whole bacterial cells, SerialEM (88) was used to acquire multiple tilt series along the cell at ×4,500 magnification. The pixel size at the specimen level is 8.2 Å. All tilt series were collected in the low-dose mode with ~10-μm defocus. A total dose of 50 e−/Å2 is distributed among 35 tilt images covering angles from −51° to +51° at tilt steps of 3°. The tilt series were aligned and reconstructed by IMOD (89). Multiple reconstructions from different segments of the same cell were integrated into one whole-cell map. In total, we generated 10 whole-cell reconstructions from the wild-type strain (3 cells) and two TDE2683 mutants (7 cells). IMOD (89) was used to take 2D snapshots of the reconstructions.

Bioinformatics and statistical analyses.

Sequence alignment analyses were performed using Clustal Omega, and homology modeling was conducted on the Swiss-Model server. Statistical significance was analyzed by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison at a P value of <0.05.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Jennifer Aronson and Ching Wooen Sze for critical reading of the manuscript. We thank Shenping Wu for assisting with cryo-ET data collection.

This research was supported by funding from the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research (DE023080 to C. Li) and National Institutes of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (AI078958 to C. Li, AI087946 to J. Liu, and AI148844 to B. Crane and C. Li), National Institutes of Health (NIH). Cryo-ET data were collected at the Yale CryoEM resource, which is funded in part by NIH grant 1S10OD023603-01A1.

Footnotes

Supplemental material is available online only.

Contributor Information

Chunhao Li, Email: cli5@vcu.edu.

Michael Y. Galperin, NCBI, NLM, National Institutes of Health

REFERENCES

- 1.Feklistov A, Sharon BD, Darst SA, Gross CA. 2014. Bacterial sigma factors: a historical, structural, and genomic perspective. Annu Rev Microbiol 68:357–376. 10.1146/annurev-micro-092412-155737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Helmann JD. 2019. Where to begin? Sigma factors and the selectivity of transcription initiation in bacteria. Mol Microbiol 112:335–347. 10.1111/mmi.14309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Saecker RM, Record MT, Jr, Dehaseth PL. 2011. Mechanism of bacterial transcription initiation: RNA polymerase-promoter binding, isomerization to initiation-competent open complexes, and initiation of RNA synthesis. J Mol Biol 412:754–771. 10.1016/j.jmb.2011.01.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liu B, Hong C, Huang RK, Yu Z, Steitz TA. 2017. Structural basis of bacterial transcription activation. Science 358:947–951. 10.1126/science.aao1923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Malhotra A, Severinova E, Darst SA. 1996. Crystal structure of a sigma 70 subunit fragment from E. coli RNA polymerase. Cell 87:127–136. 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81329-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Paget MS. 2015. Bacterial sigma factors and anti-sigma factors: structure, function and distribution. Biomolecules 5:1245–1265. 10.3390/biom5031245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chilcott GS, Hughes KT. 2000. Coupling of flagellar gene expression to flagellar assembly in Salmonella enterica serovar typhimurium and Escherichia coli. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 64:694–708. 10.1128/MMBR.64.4.694-708.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sorenson MK, Ray SS, Darst SA. 2004. Crystal structure of the flagellar sigma/anti-sigma complex sigma(28)/FlgM reveals an intact sigma factor in an inactive conformation. Mol Cell 14:127–138. 10.1016/S1097-2765(04)00150-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lonetto M, Gribskov M, Gross CA. 1992. The sigma 70 family: sequence conservation and evolutionary relationships. J Bacteriol 174:3843–3849. 10.1128/jb.174.12.3843-3849.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shi W, Zhou W, Zhang B, Huang S, Jiang Y, Schammel A, Hu Y, Liu B. 2020. Structural basis of bacterial sigma(28) -mediated transcription reveals roles of the RNA polymerase zinc-binding domain. EMBO J 39:e104389. 10.15252/embj.2020104389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hughes KT, Gillen KL, Semon MJ, Karlinsey JE. 1993. Sensing structural intermediates in bacterial flagellar assembly by export of a negative regulator. Science 262:1277–1280. 10.1126/science.8235660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aldridge PD, Karlinsey JE, Aldridge C, Birchall C, Thompson D, Yagasaki J, Hughes KT. 2006. The flagellar-specific transcription factor, sigma28, is the type III secretion chaperone for the flagellar-specific anti-sigma28 factor FlgM. Genes Dev 20:2315–2326. 10.1101/gad.380406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chevance FF, Hughes KT. 2008. Coordinating assembly of a bacterial macromolecular machine. Nat Rev Microbiol 6:455–465. 10.1038/nrmicro1887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wosten MM, van Dijk L, Veenendaal AK, de Zoete MR, Bleumink-Pluijm NM, van Putten JP. 2010. Temperature-dependent FlgM/FliA complex formation regulates Campylobacter jejuni flagella length. Mol Microbiol 75:1577–1591. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2010.07079.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Colland F, Rain JC, Gounon P, Labigne A, Legrain P, De Reuse H. 2001. Identification of the Helicobacter pylori anti-sigma28 factor. Mol Microbiol 41:477–487. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02537.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Josenhans C, Niehus E, Amersbach S, Horster A, Betz C, Drescher B, Hughes KT, Suerbaum S. 2002. Functional characterization of the antagonistic flagellar late regulators FliA and FlgM of Helicobacter pylori and their effects on the H. pylori transcriptome. Mol Microbiol 43:307–322. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.02765.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Potvin E, Sanschagrin F, Levesque RC. 2008. Sigma factors in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. FEMS Microbiol Rev 32:38–55. 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2007.00092.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Prouty MG, Correa NE, Klose KE. 2001. The novel sigma54- and sigma28-dependent flagellar gene transcription hierarchy of Vibrio cholerae. Mol Microbiol 39:1595–1609. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02348.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen YF, Helmann JD. 1992. Restoration of motility to an Escherichia coli fliA flagellar mutant by a Bacillus subtilis sigma factor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 89:5123–5127. 10.1073/pnas.89.11.5123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Eichelberg K, Galan JE. 2000. The flagellar sigma factor FliA (sigma(28)) regulates the expression of Salmonella genes associated with the centisome 63 type III secretion system. Infect Immun 68:2735–2743. 10.1128/IAI.68.5.2735-2743.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Heuner K, Dietrich C, Skriwan C, Steinert M, Hacker J. 2002. Influence of the alternative sigma(28) factor on virulence and flagellum expression of Legionella pneumophila. Infect Immun 70:1604–1608. 10.1128/IAI.70.3.1604-1608.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lertsethtakarn P, Ottemann KM, Hendrixson DR. 2011. Motility and chemotaxis in Campylobacter and Helicobacter. Annu Rev Microbiol 65:389–410. 10.1146/annurev-micro-090110-102908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Charon NW, Cockburn A, Li C, Liu J, Miller KA, Miller MR, Motaleb MA, Wolgemuth CW. 2012. The unique paradigm of spirochete motility and chemotaxis. Annu Rev Microbiol 66:349–370. 10.1146/annurev-micro-092611-150145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Goldstein SF, Charon NW, Kreiling JA. 1994. Borrelia burgdorferi swims with a planar waveform similar to that of eukaryotic flagella. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 91:3433–3437. 10.1073/pnas.91.8.3433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Charon NW, Lawrence CW, O'Brien S. 1981. Movement of antibody-coated latex beads attached to the spirochete Leptospira interrogans. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 78:7166–7170. 10.1073/pnas.78.11.7166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Radolf JD, Deka RK, Anand A, Smajs D, Norgard MV, Yang XF. 2016. Treponema pallidum, the syphilis spirochete: making a living as a stealth pathogen. Nat Rev Microbiol 14:744–759. 10.1038/nrmicro.2016.141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rosa PA, Tilly K, Stewart PE. 2005. The burgeoning molecular genetics of the Lyme disease spirochaete. Nat Rev Microbiol 3:129–143. 10.1038/nrmicro1086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Picardeau M. 2017. Virulence of the zoonotic agent of leptospirosis: still terra incognita? Nat Rev Microbiol 15:297–307. 10.1038/nrmicro.2017.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Holt SC, Ebersole JL. 2005. Porphyromonas gingivalis, Treponema denticola, and Tannerella forsythia: the “red complex”, a prototype polybacterial pathogenic consortium in periodontitis. Periodontol 2000 38:72–122. 10.1111/j.1600-0757.2005.00113.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li C, Motaleb A, Sal M, Goldstein SF, Charon NW. 2000. Spirochete periplasmic flagella and motility. J Mol Microbiol Biotechnol 2:345–354. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhao X, Zhang K, Boquoi T, Hu B, Motaleb MA, Miller KA, James ME, Charon NW, Manson MD, Norris SJ, Li C, Liu J. 2013. Cryoelectron tomography reveals the sequential assembly of bacterial flagella in Borrelia burgdorferi. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 110:14390–14395. 10.1073/pnas.1308306110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kurniyati K, Chang Y, Liu J, Li C. 2022. Transcriptional and functional characterizations of multiple flagellin genes in spirochetes. Mol Microbiol 10.1111/mmi.14959. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kurniyati K, Kelly JF, Vinogradov E, Robotham A, Tu Y, Wang J, Liu J, Logan SM, Li C. 2017. A novel glycan modifies the flagellar filament proteins of the oral bacterium Treponema denticola. Mol Microbiol 103:67–85. 10.1111/mmi.13544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Norris SJ, Charon NW, Cook RG, Fuentes MD, Limberger RJ. 1988. Antigenic relatedness and N-terminal sequence homology define two classes of periplasmic flagellar proteins of Treponema pallidum subsp. pallidum and Treponema phagedenis. J Bacteriol 170:4072–4082. 10.1128/jb.170.9.4072-4082.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li C, Sal M, Marko M, Charon NW. 2010. Differential regulation of the multiple flagellins in spirochetes. J Bacteriol 192:2596–2603. 10.1128/JB.01502-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li C, Wolgemuth CW, Marko M, Morgan DG, Charon NW. 2008. Genetic analysis of spirochete flagellin proteins and their involvement in motility, filament assembly, and flagellar morphology. J Bacteriol 190:5607–5615. 10.1128/JB.00319-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Champion CI, Miller JN, Lovett MA, Blanco DR. 1990. Cloning, sequencing, and expression of two class B endoflagellar genes of Treponema pallidum subsp. pallidum encoding the 34.5- and 31.0-kilodalton proteins. Infect Immun 58:1697–1704. 10.1128/iai.58.6.1697-1704.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Koopman MB, de Leeuw OS, van der Zeijst BM, Kusters JG. 1992. Cloning and DNA sequence analysis of a Serpulina (Treponema) hyodysenteriae gene encoding a periplasmic flagellar sheath protein. Infect Immun 60:2920–2925. 10.1128/iai.60.7.2920-2925.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Koopman MB, Baats E, van Vorstenbosch CJ, van der Zeijst BA, Kusters JG. 1992. The periplasmic flagella of Serpulina (Treponema) hyodysenteriae are composed of two sheath proteins and three core proteins. J Gen Microbiol 138:2697–2706. 10.1099/00221287-138-12-2697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Heinzerling HF, Olivares M, Burne RA. 1997. Genetic and transcriptional analysis of flgB flagellar operon constituents in the oral spirochete Treponema denticola and their heterologous expression in enteric bacteria. Infect Immun 65:2041–2051. 10.1128/iai.65.6.2041-2051.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stamm LV, Bergen HL. 1999. Molecular characterization of a flagellar (fla) operon in the oral spirochete Treponema denticola ATCC 35405. FEMS Microbiol Lett 179:31–36. 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1999.tb08703.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Seshadri R, Myers GS, Tettelin H, Eisen JA, Heidelberg JF, Dodson RJ, Davidsen TM, DeBoy RT, Fouts DE, Haft DH, Selengut J, Ren Q, Brinkac LM, Madupu R, Kolonay J, Durkin SA, Daugherty SC, Shetty J, Shvartsbeyn A, Gebregeorgis E, Geer K, Tsegaye G, Malek J, Ayodeji B, Shatsman S, McLeod MP, Smajs D, Howell JK, Pal S, Amin A, Vashisth P, McNeill TZ, Xiang Q, Sodergren E, Baca E, Weinstock GM, Norris SJ, Fraser CM, Paulsen IT. 2004. Comparison of the genome of the oral pathogen Treponema denticola with other spirochete genomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101:5646–5651. 10.1073/pnas.0307639101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Koo BM, Rhodius VA, Campbell EA, Gross CA. 2009. Dissection of recognition determinants of Escherichia coli sigma32 suggests a composite -10 region with an 'extended -10' motif and a core -10 element. Mol Microbiol 72:815–829. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2009.06690.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Battesti A, Majdalani N, Gottesman S. 2011. The RpoS-mediated general stress response in Escherichia coli. Annu Rev Microbiol 65:189–213. 10.1146/annurev-micro-090110-102946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Samuels DS. 2011. Gene regulation in Borrelia burgdorferi. Annu Rev Microbiol 65:479–499. 10.1146/annurev.micro.112408.134040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Radolf JD, Caimano MJ, Stevenson B, Hu LT. 2012. Of ticks, mice and men: understanding the dual-host lifestyle of Lyme disease spirochaetes. Nat Rev Microbiol 10:87–99. 10.1038/nrmicro2714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sivaraman J, Li Y, Larocque R, Schrag JD, Cygler M, Matte A. 2001. Crystal structure of histidinol phosphate aminotransferase (HisC) from Escherichia coli, and its covalent complex with pyridoxal-5'-phosphate and l-histidinol phosphate. J Mol Biol 311:761–776. 10.1006/jmbi.2001.4882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhang K, He J, Cantalano C, Guo Y, Liu J, Li C. 2020. FlhF regulates the number and configuration of periplasmic flagella in Borrelia burgdorferi. Mol Microbiol 113:1122–1139. 10.1111/mmi.14482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Balaban M, Joslin SN, Hendrixson DR. 2009. FlhF and its GTPase activity are required for distinct processes in flagellar gene regulation and biosynthesis in Campylobacter jejuni. J Bacteriol 191:6602–6611. 10.1128/JB.00884-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lybecker MC, Abel CA, Feig AL, Samuels DS. 2010. Identification and function of the RNA chaperone Hfq in the Lyme disease spirochete Borrelia burgdorferi. Mol Microbiol 78:622–635. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2010.07374.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Park S, Yoon J, Lee CR, Lee JY, Kim YR, Jang KS, Lee KH, Seok YJ. 2019. Polar landmark protein HubP recruits flagella assembly protein FapA under glucose limitation in Vibrio vulnificus. Mol Microbiol 112:266–279. 10.1111/mmi.14268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Park S, Park YH, Lee CR, Kim YR, Seok YJ. 2016. Glucose induces delocalization of a flagellar biosynthesis protein from the flagellated pole. Mol Microbiol 101:795–808. 10.1111/mmi.13424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schumacher MA, Gallagher KA, Holmes NA, Chandra G, Henderson M, Kysela DT, Brennan RG, Buttner MJ. 2021. Evolution of a sigma-(c-di-GMP)-anti-sigma switch. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 118:e2105447118. 10.1073/pnas.2105447118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gallagher KA, Schumacher MA, Bush MJ, Bibb MJ, Chandra G, Holmes NA, Zeng W, Henderson M, Zhang H, Findlay KC, Brennan RG, Buttner MJ. 2020. c-di-GMP arms an anti-sigma to control progression of multicellular differentiation in Streptomyces. Mol Cell 77:586–599.E6. 10.1016/j.molcel.2019.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Koo BM, Rhodius VA, Campbell EA, Gross CA. 2009. Mutational analysis of Escherichia coli sigma28 and its target promoters reveals recognition of a composite -10 region, comprised of an 'extended -10' motif and a core -10 element. Mol Microbiol 72:830–843. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2009.06691.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chadsey MS, Hughes KT. 2001. A multipartite interaction between Salmonella transcription factor sigma28 and its anti-sigma factor FlgM: implications for sigma28 holoenzyme destabilization through stepwise binding. J Mol Biol 306:915–929. 10.1006/jmbi.2001.4438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Heuner K, Hacker J, Brand BC. 1997. The alternative sigma factor sigma28 of Legionella pneumophila restores flagellation and motility to an Escherichia coli fliA mutant. J Bacteriol 179:17–23. 10.1128/jb.179.1.17-23.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zhao K, Liu M, Burgess RR. 2007. Adaptation in bacterial flagellar and motility systems: from regulon members to 'foraging'-like behavior in E. coli. Nucleic Acids Res 35:4441–4452. 10.1093/nar/gkm456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yu HH, Kibler D, Tan M. 2006. In silico prediction and functional validation of sigma28-regulated genes in Chlamydia and Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol 188:8206–8212. 10.1128/JB.01082-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Aldridge P, Gnerer J, Karlinsey JE, Hughes KT. 2006. Transcriptional and translational control of the Salmonella fliC gene. J Bacteriol 188:4487–4496. 10.1128/JB.00094-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Schaubach OL, Dombroski AJ. 1999. Transcription initiation at the flagellin promoter by RNA polymerase carrying sigma28 from Salmonella typhimurium. J Biol Chem 274:8757–8763. 10.1074/jbc.274.13.8757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Goetting-Minesky MP, Fenno JC. 2010. A simplified erythromycin resistance cassette for Treponema denticola mutagenesis. J Microbiol Methods 83:66–68. 10.1016/j.mimet.2010.07.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Limberger RJ, Slivienski LL, Izard J, Samsonoff WA. 1999. Insertional inactivation of Treponema denticola tap1 results in a nonmotile mutant with elongated flagellar hooks. J Bacteriol 181:3743–3750. 10.1128/JB.181.12.3743-3750.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ruby JD, Li H, Kuramitsu H, Norris SJ, Goldstein SF, Buttle KF, Charon NW. 1997. Relationship of Treponema denticola periplasmic flagella to irregular cell morphology. J Bacteriol 179:1628–1635. 10.1128/jb.179.5.1628-1635.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Chevance FF, Hughes KT. 2017. Coupling of flagellar gene expression with assembly in Salmonella enterica. Methods Mol Biol 1593:47–71. 10.1007/978-1-4939-6927-2_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Chadsey MS, Karlinsey JE, Hughes KT. 1998. The flagellar anti-sigma factor FlgM actively dissociates Salmonella typhimurium sigma28 RNA polymerase holoenzyme. Genes Dev 12:3123–3136. 10.1101/gad.12.19.3123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sze CW, Morado DR, Liu J, Charon NW, Xu H, Li C. 2011. Carbon storage regulator A (CsrA(Bb)) is a repressor of Borrelia burgdorferi flagellin protein FlaB. Mol Microbiol 82:851–864. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2011.07853.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Sal MS, Li C, Motalab MA, Shibata S, Aizawa S, Charon NW. 2008. Borrelia burgdorferi uniquely regulates its motility genes and has an intricate flagellar hook-basal body structure. J Bacteriol 190:1912–1921. 10.1128/JB.01421-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Claret L, Miquel S, Vieille N, Ryjenkov DA, Gomelsky M, Darfeuille-Michaud A. 2007. The flagellar sigma factor FliA regulates adhesion and invasion of Crohn disease-associated Escherichia coli via a cyclic dimeric GMP-dependent pathway. J Biol Chem 282:33275–33283. 10.1074/jbc.M702800200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Sterzenbach T, Bartonickova L, Behrens W, Brenneke B, Schulze J, Kops F, Chin EY, Katzowitsch E, Schauer DB, Fox JG, Suerbaum S, Josenhans C. 2008. Role of the Helicobacter hepaticus flagellar sigma factor FliA in gene regulation and murine colonization. J Bacteriol 190:6398–6408. 10.1128/JB.00626-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Schulz T, Rydzewski K, Schunder E, Holland G, Bannert N, Heuner K. 2012. FliA expression analysis and influence of the regulatory proteins RpoN, FleQ and FliA on virulence and in vivo fitness in Legionella pneumophila. Arch Microbiol 194:977–989. 10.1007/s00203-012-0833-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Goon S, Ewing CP, Lorenzo M, Pattarini D, Majam G, Guerry P. 2006. A sigma28-regulated nonflagella gene contributes to virulence of Campylobacter jejuni 81–176. Infect Immun 74:769–772. 10.1128/IAI.74.1.769-772.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Syed KA, Beyhan S, Correa N, Queen J, Liu J, Peng F, Satchell KJ, Yildiz F, Klose KE. 2009. The Vibrio cholerae flagellar regulatory hierarchy controls expression of virulence factors. J Bacteriol 191:6555–6570. 10.1128/JB.00949-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Bian J, Shen H, Tu Y, Yu A, Li C. 2011. The riboswitch regulates a thiamine pyrophosphate ABC transporter of the oral spirochete Treponema denticola. J Bacteriol 193:3912–3922. 10.1128/JB.00386-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Patel DT, O'Bier NS, Schuler EJA, Marconi RT. 2021. The Treponema denticola DgcA protein (TDE0125) is a functional diguanylate cyclase. Pathog Dis 79:ftab004. 10.1093/femspd/ftab004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Marconi RT. 2018. Gene regulation, two component regulatory systems, and adaptive responses in Treponema denticola. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol 415:39–62. 10.1007/82_2017_66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Bian J, Liu X, Cheng YQ, Li C. 2013. Inactivation of cyclic Di-GMP binding protein TDE0214 affects the motility, biofilm formation, and virulence of Treponema denticola. J Bacteriol 195:3897–3905. 10.1128/JB.00610-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Ohta K, Makinen KK, Loesche WJ. 1986. Purification and characterization of an enzyme produced by Treponema denticola capable of hydrolyzing synthetic trypsin substrates. Infect Immun 53:213–220. 10.1128/iai.53.1.213-220.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kurniyati K, Liu J, Zhang JR, Min Y, Li C. 2019. A pleiotropic role of FlaG in regulating the cell morphogenesis and flagellar homeostasis at the cell poles of Treponema denticola. Cell Microbiol 21:e12886. 10.1111/cmi.12886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Kurniyati K, Li C. 2016. pyrF as a counterselectable marker for unmarked genetic manipulations in Treponema denticola. Appl Environ Microbiol 82:1346–1352. 10.1128/AEM.03704-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Fletcher HM, Schenkein HA, Morgan RM, Bailey KA, Berry CR, Macrina FL. 1995. Virulence of a Porphyromonas gingivalis W83 mutant defective in the prtH gene. Infect Immun 63:1521–1528. 10.1128/iai.63.4.1521-1528.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Heimbrook ME, Wang WL, Campbell G. 1989. Staining bacterial flagella easily. J Clin Microbiol 27:2612–2615. 10.1128/jcm.27.11.2612-2615.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Ouyang Z, Deka RK, Norgard MV. 2011. BosR (BB0647) controls the RpoN-RpoS regulatory pathway and virulence expression in Borrelia burgdorferi by a novel DNA-binding mechanism. PLoS Pathog 7:e1001272. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Bian J, Fenno JC, Li C. 2012. Development of a modified gentamicin resistance cassette for genetic manipulation of the oral spirochete Treponema denticola. Appl Environ Microbiol 78:2059–2062. 10.1128/AEM.07461-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Kurniyati K, Li C. 2021. Genetic manipulations of oral spirochete Treponema denticola. Methods Mol Biol 2210:15–23. 10.1007/978-1-0716-0939-2_2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Bian J, Tu Y, Wang SM, Wang XY, Li C. 2015. Evidence that TP_0144 of Treponema pallidum is a thiamine-binding protein. J Bacteriol 197:1164–1172. 10.1128/JB.02472-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Wolfe AJ, Berg HC. 1989. Migration of bacteria in semisolid agar. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 86:6973–6977. 10.1073/pnas.86.18.6973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Mastronarde DN. 2005. Automated electron microscope tomography using robust prediction of specimen movements. J Struct Biol 152:36–51. 10.1016/j.jsb.2005.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Kremer JR, Mastronarde DN, McIntosh JR. 1996. Computer visualization of three-dimensional image data using IMOD. J Struct Biol 116:71–76. 10.1006/jsbi.1996.0013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Danson AE, Jovanovic M, Buck M, Zhang X. 2019. Mechanisms of sigma(54)-dependent transcription initiation and regulation. J Mol Biol 431:3960–3974. 10.1016/j.jmb.2019.04.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Zhang N, Buck M. 2015. A perspective on the enhancer dependent bacterial RNA polymerase. Biomolecules 5:1012–1019. 10.3390/biom5021012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1 and Fig. S1 to S4. Download jb.00248-22-s0001.pdf, PDF file, 1.0 MB (1,023.6KB, pdf)