Abstract

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a neurodegenerative disorder that causes progressive loss of cognitive functions like thinking, memory, reasoning, behavioral abilities, and social skills thus affecting the ability of a person to perform normal daily functions independently. There is no definitive cure for this disease, and treatment options available for the management of the disease are not very effective as well. Based on histopathology, AD is characterized by the accumulation of insoluble deposits of amyloid beta (Aβ) plaques and neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs). Although several molecular events contribute to the formation of these insoluble deposits, the aberrant post-translational modifications (PTMs) of AD-related proteins (like APP, Aβ, tau, and BACE1) are also known to be involved in the onset and progression of this disease. However, early diagnosis of the disease as well as the development of effective therapeutic approaches is impeded by lack of proper clinical biomarkers. In this review, we summarized the current status and clinical relevance of biomarkers from cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), blood and extracellular vesicles involved in onset and progression of AD. Moreover, we highlight the effects of several PTMs on the AD-related proteins, and provide an insight how these modifications impact the structure and function of proteins leading to AD pathology. Finally, for disease-modifying therapeutics, novel approaches, and targets are discussed for the successful treatment and management of AD.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, AD-related proteins, biomarkers, post translational modifications, AD therapeutics

Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a neurodegenerative disorder associated with diminished regenerative capacity of neurons and impaired cognitive functions including learning and memory (Galimberti and Scarpini, 2012; Haque and Levey, 2019; Chatterjee et al., 2020). Nearly 35 million people are suffering from AD worldwide and is estimated to be doubled by 2030 (Alzheimer’s Association, 2019; Haque and Levey, 2019). The nature of this disease demands proper and long-term medical care which has accounted for an estimated cost of $195 billion in 2019 and is expected to rise to $1 trillion by 2050 (Alzheimer’s Association, 2019). Various factors contribute to AD-related dementia and impairment of cognitive functions, however, extracellular amyloid beta (Aβ) plaques and intracellular aggregates of hyperphosphorylated tau proteins also called neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs) are the two major histopathological hallmarks of AD (Mayeux and Stern, 2012; Xu et al., 2012; Kametani and Hasegawa, 2018; Janeiro et al., 2021). Accumulation of amyloid beta (Aβ) plaques and NFTs initiate a cascade of events, resulting firstly in synaptic dysfunction, axonal degeneration and impaired cellular communication, and followed subsequently as the disease progresses by gliosis, neurodegeneration and widespread neuronal death (Wang et al., 2013; Hampel et al., 2015; Li et al., 2015; Pini et al., 2016; Knezevic et al., 2018). Although accumulation of Aβ deposits and NFTs are the pathological hallmarks of AD and have drawn the special attention of researchers in the search for biological markers, it is clear now that the disease begins decades before the onset of any clinical symptoms. To predict, diagnose, or monitor the progression of AD disease biomarkers are considered useful in every step of patient care. As disease symptoms are subjective, biomarkers provide an objective, measurable way to characterize the disease. Biomarkers for Alzheimer’s disease aim to facilitate early disease prognosis and makes it possible to determine the progression of disease during initial stage and evaluate response to existing and future treatments. Also, biomarkers are likely to predict clinical benefit and support accelerated or traditional drug approval, respectively. There is an unmet need for identification of such clinical biomarker for Alzheimer’s disease.

Major proteins and enzymes involved in Alzheimer’s progression: Role of amyloid-beta precursor protein, secretase, Tau, beta-site amyloid-beta precursor protein-cleaving enzyme, Apo E, PS1/2, and microglia

Amyloid-beta precursor protein and secretase enzymes

Amyloid-beta precursor protein (APP) encoded by a gene APP (located on chromosome 21) is a ubiquitous type-1 transmembrane protein with three splice variants: APP695, APP751, and APP770 expressed mostly in neurons, astrocytes, and vascular endothelial cells respectively (Miura et al., 2020; Zhao et al., 2020). Although the exact functions of APP are not known, however, its expression increases during differentiation of neurons and synapse formation, and declines once mature connections are established, suggesting the role of APP in aging and development (Chen et al., 2017). Under normal conditions, APP undergoes non-pathogenic processing by involving two important enzymes α-and γ-secretase. These enzymes cleave the APP within the Aβ domain resulting into non-amyloidogenic fragments along with soluble amyloid precursor protein fragments α (sAPPα) and C-terminal fragments (CTFs). In diseased conditions, a different set of enzymes including β-and γ-secretase to cleave the APP in such a way that it generates the neurotoxic Aβ peptides (40–42 amino acid long peptides), along with soluble amyloid precursor protein fragments β (sAPPβ) and CTFs (Nesterova et al., 2019). Various studies have shown a link between the mutations of APP and AD; for example 10–15% cases of early-onset-familial Alzheimer’s disease (EOFAD) are reported to be caused by APP gene mutations (Hooli and Tanzi, 2016). Such mutations appear to influence the biology of Aβ by promoting local oligomer/fibril formation or changing the propensity of Aβ to bind to other proteins and affecting Aβ clearance. This ability of APP to undergo cleavage using different set of enzymes to form either soluble or pathogenic amyloid-beta (Aβ) peptides makes APP as a main target protein in AD progression. Any mutation in APP and in the proteins that regulate APP endocytosis and processing in neurons leading to disturbed APP-related intracellular signaling pathways can be used as a biomarker during early stages of AD.

Tau protein

Tau is a microtubule-associated protein involved in the stabilization of microtubules by promoting their polymerization. The association of tau protein with the microtubules is involved in regulating the axonal transport as well as neuronal cytoskeleton (Zhou et al., 2018). Six different isoforms of tau are usually expressed in normal mature human brains however they are found to be abnormally hyperphosphorylated in AD brains. Any unusual alterations in the structural conformation or phosphorylation events of tau impact its binding affinity with microtubule which leads to its toxic aggregation in the form of neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs) and paired helical filaments (PHFs). These NFTs which on aggregation attain the shape of PHFs are one among the major hallmarks seen in pathology of AD (Augustinack et al., 2002). Tau phosphorylation and its detailed role in the pathogenesis is included elsewhere under post-translational modifications (PTMs) in AD. Importantly, Hyper-phosphorylated tau is considered to be promising biomarker for monitoring the disease progression in AD.

Beta-site amyloid-beta precursor protein-cleaving enzyme

Beta-Site APP-cleaving enzyme (BACE) is a ubiquitously expressed membrane-bound aspartyl protease. It uses its proteolytic activity for the production of neuro-pathogenic Aβ peptides. There are four splice variants of BACE with 501, 476, 457, and 432 amino acids. Among these variants 501 variant is having the highest degree of proteolytic activity on Aβ amyloid substrate (Mowrer and Wolfe, 2008). The production of Aβ peptides from its precursor APP occurs in two sequential proteolytic cleavages. First cleavage is catalyzed by BACE in which BACE cleaves the ectodomain of APP generating a C99 membrane-bound C-terminal fragment and the second proteolytic reaction is carried out by γ-secretase which further processes a C99 fragment leading to the formation of Aβ peptides (Bolduc et al., 2016). In AD patients BACE is highly expressed in various parts of the brain especially in brain cortex and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) (Hampel et al., 2020). The increased expression of BACE can serve as an early biomarker in detection of AD (Blennow et al., 2010; Evin et al., 2010), and its increased expression has been directly co-related with the age of the patient and stress level (O’brien and Wong, 2011). BACE1 protein concentrations and rates of enzyme activity are promising candidates among biological markers in clinical trials investigating the role of BACE1 inhibitors in regulating APP processing.

Apolipoprotein E

In the central nervous system (CNS), apolipoprotein E (ApoE) is mostly synthesized and produced by astrocytes to transport cholesterol to neurons via ApoE receptors (Bu, 2009). ApoE is composed of 299 amino acids and exists in three isoforms in humans; ApoE2, ApoE3, and ApoE4. The single amino acid differences alter the structure of these isoforms and influences their functional abilities (Frieden and Garai, 2012). The ApoE4 isoform represents the most significant risk factor for late-onset Alzheimer disease (LOAD) (Corder et al., 1993; Mahoney-Sanchez et al., 2016). The individuals carrying the rare E2 variant are less likely to develop AD and E3 represents the most common but non-pathogenic isoform of ApoE (Serrano-Pozo et al., 2015). Although number of studies have been conducted to understand the mechanism of action of different variants of ApoE, but further investigation and research is needed to fully understand the differential effects of ApoE isoforms on Aβ aggregation and clearance in AD pathogenesis (Kim et al., 2009; Husain et al., 2021). In an interesting study, the total ApoE and ApoE4 plasma proteins were assessed using Australian Imaging, Biomarkers and Lifestyle (AIBL) study of aging and the result were assessed by Positron Emission Tomography (PET) using Pittsburgh compound B (PiB). The levels of these plasma proteins were compared with cerebral Aβ load, and it was found that both the total ApoE as well as ApoE4 levels are significantly lowered in AD patients. From ApoE genotyping, the protein (ApoE) levels were significantly lower among E4 homozygous individuals and in APOE E3/E4 heterozygote carriers, ApoE4 levels decreased, indicating that ApoE3 levels increase with disease. This study suggests that ApoE, ApoE3, and ApoE4 can be used as AD biomarkers and possible therapeutic drug targets (Gupta et al., 2011; Soares et al., 2012).

Presenilin 1

Presenilin 1 protein encoded by PSEN1 gene is located on chromosome 14 and forms an important component of the γ-secretase complex, which cleaves APP into Aβ fragments (Steiner et al., 2008). It is mostly expressed in endoplasmic reticulum and helps in protein processing (Bezprozvanny and Mattson, 2008). The importance of PSEN1 gene in AD is evident from the fact that it accounts for about 50% cases of early-onset Alzheimer’s disease (EOAD), with complete penetrance (Giri et al., 2016). Mutation in PSEN1 leads to mutations in γ-secretase and increase in the Aβ42/40 ratio resulting in cotton wool plague formation (Zhang et al., 2015; Miki et al., 2019). Only few mutations are insertions and deletions, majority of PSEN1 mutations are missense. PSEN1 mutations not only affect the activity of γ-secretase enzyme but also directly affect the neuronal functioning by controlling the activity of GSK-3β and kinesin I (Giri et al., 2016). More than 295 pathogenic mutations have been identified in PSEN1, of which 70% mutations occur in exons 5, 6, 7, and 8. Studies using genetically modified mice have shown that mutations in PSEN1 lead to impaired Aβ production and increased ratio of Aβ42/Aβ40 (Xia et al., 2015). Recent studies that investigated potential relationships between the molecular composition of FAD-linked Aβ profiles and disease severity by analyzing Aβ profiles generated by 25 mutant PSEN1/GSECs that span a wide range of AAOs, revealed that full spectrum of Aβ profiles (including Aβ37, Aβ38, Aβ40, Aβ42, and Aβ43) better reflects mutation pathogenicity. Furthermore, this study suggested Aβ(37 + 38 + 40)/Aβ(42 + 43) ratio better at predicting the age at disease onset (Petit et al., 2022). Presently, PSEN1 gene is considered as the most common cause of familial Alzheimer’s disease (FAD). However, a recent studies (Sun et al., 2017) contradicts the role of PSEN1 in AD progression by increasing the Aβ42 production (Hardy and Selkoe, 2002) and therefore is a matter of a debate in the scientific world.

Presenilin 2

Presenilin 2 protein encoded by PSEN2 gene is located on chromosome 1 is similar in structure and function to PSEN1 (Ridge et al., 2013). Similar to PSEN1, it also forms the important component of the γ secretase complex and any mutation in PSEN2 alters the activity of γ secretase leading to elevated ratio of Aβ42/40 (Wakabayashi and De Strooper, 2008). Despite close homology between the two, mutations in PSEN2 are less toxic and less common than PSEN1, but neuritic plaque accumulation and neurofibrillary tangle (NFT) formation have been found in some people with PSEN2 mutations (Giri et al., 2016). Efforts to develop disease-modifying therapies for AD have been heavily focused on the amyloid hypothesis but repeated failures in late-stage clinical trials based on these hypotheses heighten the urgency to explore alternative approaches. Thus, therapeutic strategies aimed at restoring secretase activities by involving modifications or mutations at the levels of PSN1 and PSN2 offer a valid and complementary approach to develop disease modifying treatments for FAD.

Microglial role in Alzheimer’s disease

Microglia, a type of neuroglia (glial cells), forms the innate immune system of our central nervous system (CNS). Proliferation, activation, and concentration of these glial cells in the brain around amyloid plaques, is a prominent feature of AD. Data from human genetic studies also suggest the role of these cells in AD progression. Under normal conditions, microglia protect against AD, however, impaired microglial activities lead to increased risk of AD progression. Activated microglial cells can be harmful and mediate loss of synaptic junctions via complement-dependent mechanisms, increase tau phosphorylation and enhance inflammatory responses against neurons leading to activation of neurotoxic astrocytes (Hansen et al., 2018). The role of microglia in forming neuritic plaques was described long back by Alois Alzheimer himself (Alzheimer et al., 1995; Graeber et al., 1997) and further studies have shown the involvement of both reactive astrocytes and microglia in deposition of Aβ plagues (Verkhratsky et al., 2016). In AD patients, the microglia interact with the amyloid peptides, APP, and neurofibrillary tangles during early phase of AD, and their activation promote Aβ clearance through microglia’s scavenger receptors, and thus acts as a hurdle in the progression of AD. The Aβ activation induced continuous activation of microglia involving CD36, Fc receptors, toll-like receptors (TLRs), and complement receptors advanced glycation end products (RAGE), promote Aβ production while hampering Aβ clearance, which ultimately causes neuronal damage (Wang et al., 2015). In a study done on post-mortem brain sections taken from AD patient, it was found that increased microglia activation begins with amyloid NP deposition and the increase was found to be directly related to the part of brain involved in AD (Xiang et al., 2006). Thus, activation of microglia in brain tissues, such as hippocampi, can serve as an inflammatory biomarker for AD.

Major sources and methods for isolation of potential biomarkers for Alzheimer’s disease

One of the major challenges in the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease is the lack of sensitive and specific biomarkers. Multiple studies have argued that AD begins decades before the onset of clinical symptoms and accumulation of Aβ deposits and NFTs-pathological hallmarks of AD. Clinically relevant biomarkers are expected to be useful in detecting the preclinical as well as symptomatic stages of AD. Such clinically relevant biomarkers used in the validation of AD are structured through a road map called the Strategic Biomarker Roadmap (SBR), initiated in 2017 and according to recent reports is still valid for the assessment of biomarkers of tauopathy, as well as that of the other diagnostic biomarkers of AD and related disorders (Boccardi et al., 2021). Moreover, biomarkers would be significantly helpful to predict, diagnose, or monitor the progression of AD disease during initial stage, and in evaluating response to existing and future treatments. Till date different methods have been followed to access and isolate the different biomarkers for AD.

Potential biomarkers for Alzheimer’s disease from cerebrospinal fluid

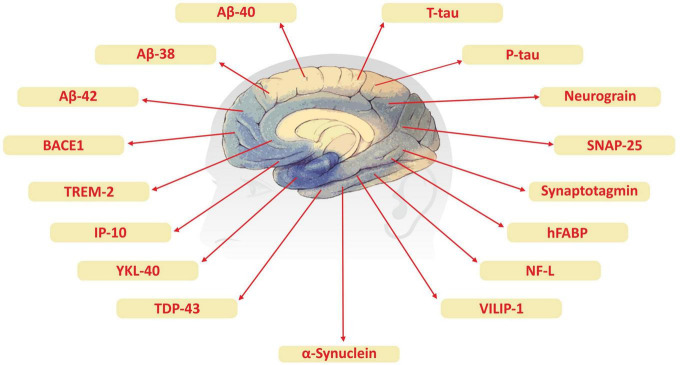

Although advanced neuroimaging techniques have been very useful in assessing structural and physiological changes in the brains of AD patients, clinical biomarkers still represent the most convenient and direct means to monitor the disease state. Despite the fact that PET and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) biomarkers are useful information for the diagnosis of AD, these methods have limited use due to their sophistication, invasiveness, and high cost. In the search for biological markers of AD, Aβ42, t-Tau, and p-Tau have drawn the special attention of researchers. Various types of brain specific biomarkers associated with AD are shown in Figure 1, CSF specific biomarkers for AD are listed in Table 1 and diagnostic platforms based on four chief biomarkers for AD along with various parameter are listed in Table 2. Aβ42, T-tau and P-tau biomarkers can predict progression from preclinical to clinical AD (Mattsson et al., 2018). The levels and variations of Aβ in CSF have been an essential hallmark feature of AD-type dementia (d’Abramo et al., 2020). It has been suggested that the ratio of CSF Aβ42/Aβ40 can be a superior biomarker because this ratio is quite useful in the differentiation of AD from other non-Alzheimer’s related cognitive changes like the subcortical deficits related to vascular diseases. Aβ42 levels in the CSF are generally lower in comparison to the controls and Aβ42 levels decrease substantially with an increase in disease progression (d’Abramo et al., 2020). The other biomarkers like YKL-40 (Chitinase-3-protein like), VILIP-1 (VLP-1) and, NFL are associated with glial inflammation, neuronal damage and non-specific marker for neurodegeneration respectively can also be used for the diagnosis but the limit of detection (LOD) and accuracy should be validated first in order to gain the specificity (Gaiottino et al., 2013; Olsson et al., 2016).

FIGURE 1.

Brain specific biomarker associated with Alzheimer’s disease.

TABLE 1.

Biomarkers for Alzheimer’s disease (AD) in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF).

| Biomarker | Concerned diagnosis | References |

| Aβ42 | CSF | Olsson et al., 2016; Wellington et al., 2016 |

| Aβ40 | Coupled with CSF | Olsson et al., 2016; Wellington et al., 2016; Janelidze et al., 2016b |

| Aβ38 | AD and dementia. | Olsson et al., 2016; Janelidze et al., 2016b |

| sAPPα | Associated with dementia | Olsson et al., 2016 |

| sAPPβ | Combination with CSF | Olsson et al., 2016 |

| t-Tau and p-Tau | CSF | Olsson et al., 2016 |

| NFL | CSF | Olsson et al., 2016 |

| NSE | CSF | Olsson et al., 2016 |

| VLP-1 | CSF | Olsson et al., 2016 |

| HFABP | CSF | Olsson et al., 2016 |

| Albumin-ratio | CSF and dementia | Wellington et al., 2016 |

| YKL-40 | CSF | Olsson et al., 2016; Wellington et al., 2016 |

| MCP-1 | AD and dementia | Olsson et al., 2016; Wellington et al., 2016 |

| GFAP | CSF and dementia | Olsson et al., 2016; Wellington et al., 2016 |

| Neurogranin | AD | Janelidze et al., 2016b |

| sTREM2 | CSF | Suárez-Calvet et al., 2016 |

| A lpha-synuclein | AD | Majbour et al., 2017 |

TABLE 2.

Sensing platforms based on four chief biomarkers associated with Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and their limit of detection (LOD).

| Sensing platform | Biomarker | Protein form | Limit of detection | Dynamic range | Sensitivity | Specificity | References |

| IP-MS | High performance plasma amyloid-β biomarkers for Alzheimer’s disease | APP 669-711/Aβ142 | 2.5Da | ∼180 ng/ml | 96.7% (AUC) | 81.0% (AUC) | Nakamura et al., 2018 |

| IMR | Assay of plasma phosphorylated tau protein (threonine 181) and total tau protein in early-stage Alzheimer’s disease | Tau | 0.0028 pg/ml | 0.001–10,000 pg/ml | 0.793 (ROC) | 0.836 (ROC) | Yang et al., 2018 |

| Digital-ELISA | Plasma neurofilament light as a potential biomarker of neurodegeneration in Alzheimer’s disease | NFL | 0.62 pg/ml | unknown | 0.84 (ROC) | 0.78 (ROC) | Lewczuk et al., 2018 |

| ELISA | C-terminal neurogranin is increased in cerebrospinal fluid but unchanged in plasma in Alzheimer’s disease | Neurogranin | 3 pg/ml | 3–2,000 pg/ml | x | x | De Vos et al., 2015 |

Potential biomarkers for Alzheimer’s disease from blood

Blood-based biomarkers are more cost-effective than PET imaging, less invasive than CSF testing, and can be used as viable first-line tools in the multi-stage diagnostic processes (d’Abramo et al., 2020). Since blood testing is a part of clinical routines all over the world which require no special or further training, therefore, blood-based biomarkers for AD are more promising. Although, a lot of progress has been made in understanding the role of biomarkers in the pathophysiology of AD (Tables 1, 2), there is still a need for the development of blood-based biomarkers that can help in the early diagnosis of AD and to understand disease progression. Tau and β-Site APP Cleavage Enzyme 1 (BACE 1) to some levels are useful in this context (Snyder et al., 2014). Tau levels in the blood can be used to predict the onset of future cognitive decline and the levels of BACE1 activity in the blood can also be used to predict the progression of mild cognitive impairment to AD dementia (Hampel et al., 2018). Aβ peptides like Aβ1-42, Aβ1-40, and Aβ1-17 as well as tau are important blood biomarkers to detect AD and its progression. These peptides in plasma can be detected by immunoprecipitation and mass spectroscopy (Pannee et al., 2014; Ovod et al., 2017). It has been found that the plasma levels of Aβ-42, Aβ1-40, and Aβ1-42/Aβ1-40 are low in AD patients but show a significant correlation with CSF levels (Janelidze et al., 2016a). Blood levels of Aβ1-17 also play an important role in the diagnosis of AD. The ratio of free to cell-bound Aβ1-17 levels in the blood helped to understand the difference between healthy individuals and individuals with mild AD with high specificity and sensitivity (Snyder et al., 2014). Tau proteins in plasma have been quantified by sensitive immunoassay techniques and found to be increased in AD patients compared to controls (Zetterberg et al., 2013; Neergaard et al., 2018). Phosphorylated tau (p-tau) proteins are leading blood biomarkers that identify AD, and its underlying pathology. It also highlights future risks of AD. Plasma p-tau (p-tau217 and p-tau181) highlights AD in dementia cases with high accuracy and can also be validated by neuropathological studies. AD progression can be strongly predicted by even baseline increases of p-tau biomarkers However, assay platform comparisons and effects of covariates and accurate biomarker cut-offs for p-tau and Aβ are still lacking necessitating more studies in this direction in the context of Strategic Biomarker Roadmap (Ashton et al., 2021). Moreover, Aβ1–42, Aβ1–40 and phosphorylated tau represent post-translationally modified protein species this explains the involvement of PTMs as biomarkers in AD (Henriksen et al., 2014). Furthermore, recent studies suggested Aβ37/42 ratio could become an improved Aβ biomarker for Alzheimer’s disease of pathogenicity and clinical diagnosis (Liu et al., 2022). Other proteins like axonal protein and neurofilament light (NF-L) are found to be increased in the serum of AD patients and have been found to be comparable with plasma Aβ1–42/Aβ1–40 (Mattsson et al., 2017). However, high NFL-1 concentration in plasma is not associated only with AD but also with other neurodegenerative disorders (Progressive supranuclear palsy and corticobasal syndrome). Recently, investigators questioned if a panel of blood-based biomarkers instead of an individual biomarker could be more useful in the detection of AD. In this direction, O’Bryant used a different set of 30 serum proteins to develop an algorithm that could detect AD with 80% sensitivity and 91% specificity (O’Bryant et al., 2010). It was reported that a panel of three blood markers von Willebrand factor, cortisol, and oxidized LDL antibodies identified using multivariate data analysis, could distinguish between AD patients and normal ones with more than 80% accuracy (Laske et al., 2011). To some level, microRNAs and PTMs can also serve as biomarkers for AD. Alterations in microRNAs levels are reported to be associated with AD pathology and efforts are being made to monitor the changes in the individual miRNAs in blood as biomarkers (Henriksen et al., 2014). A decrease in miR-132-3p levels has been reported to be associated with AD due to the hyper-phosphorylation of tau (Lau et al., 2013). Interestingly, miR-125b and miR-26b have been reported to be increased in AD patients and both are associated with tau phosphorylation (Absalon et al., 2013; Ma et al., 2017). Blood biomarkers are reliable and promising in AD detection Anything that may interfere with the detection of AD biomarkers when their concentration is low in blood is taken care of by modern diagnostic platforms that work with high dilution and high amplification of the specific signal which allows the detection of picomolar/ml or even lesser concentrations of the target biomarker. It was shown that detection by immunoprecipitation followed by liquid chromatography-mass spectroscopy (IP-MS) is a high precision assay for plasma Aβ42-40 ratio, which predicts brain amyloidosis with 90% accuracy (d’Abramo et al., 2020). Recent clinic trials based on biomarker identification for Alzheimer’s disease are listed in Table 3.

TABLE 3.

List of natural products and synthetic drugs tested for identification of a reliable clinical biomarker in various clinical trials of Alzheimer’s disease.

| Therapy | Drug | Stage of AD | Used as (mechanism of action) | References |

| Anti-amyloid therapy | Solanezumab | Mild | Monoclonal antibody (mAb) | Honig et al., 2018 |

| Verubecestat | Mild to Moderate stages | BACE inhibitor | Villarreal et al., 2017; Egan et al., 2018 | |

| Verubecestat | Prodromal stage | BACE inhibitor | ||

| Atabecestat | Preclinical stage | Novak et al., 2020 | ||

| Lanabecestat | Early stage | Wessels et al., 2020 | ||

| Lanabecestat | Mild stage | |||

| Aducanumab | Early AD | mAb | Beshir et al., 2022 | |

| CNP520 | Preclinical stage | BACE inhibitor | Neumann et al., 2018 | |

| Plasma exchange with albumin 1 Ig | Mild to Moderate stages | Plasma exchange | Boada et al., 2019 | |

| ALZT-OP1a + ALZT-OP1 | Preclinical stage | Mast cell stabilizer, anti-inflammatory | Lozupone et al., 2022 | |

| ANAVEX2–73 | Anti-tau, Anti-amyloid | |||

| Crenezumab | mAb | Salloway et al., 2018; Avgerinos et al., 2021 | ||

| E2609 (elenbecestat) | BACE inhibitor | Huang et al., 2020; Patel et al., 2022 | ||

| Gantenerumab | Prodromal to moderate stage | mAb | Klein et al., 2019 | |

| Gantenerumab and Solanezumab | Early stages | Salloway et al., 2021 | ||

| GV-971 (sodium oligomannurarate) | Mild to moderate stage | Aβ aggregation inhibitor | Wang T. et al., 2020 | |

| Solanezumab | Dominantly inherited AD | mAb | Salloway et al., 2021 | |

| Non-Anti-amyloid therapy | AC-1204 | Mild to Late (severe) stage | Induction of ketosis | Dewsbury et al., 2021 |

| AGB101 (levetiracetam) | Mild stage | SV2A modulator | Cummings et al., 2020; Tampi et al., 2021 | |

| Aripiprazole | Early stage | Partial agonist at dopamine D2 and 5-HT 1A receptors | Zheng et al., 2020 | |

| AVP-786 | Early stage | Sigma-1 receptor agonist, Anti-NMDA receptor | Khoury et al., 2021 | |

| AXS-05 | Early stage | Sigma-1 receptor agonist; Anti-NMDA receptor and dopamine-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor | Huang et al., 2020; Nagata et al., 2022 | |

| Azeliragon | Mild stage | Microglial activation inhibitor, antagonist of the receptor for glycation end products | Burstein et al., 2018; Yang et al., 2021 | |

| OPC-34712 (brexpiprazole) | Mild stage | Agonist of serotonin, 5-hydroxytryptamine1A and dopamine D2 receptors and an antagonist of serotonin 5-hydroxytryptamine2A | Liu et al., 2018; Zarini-Gakiye et al., 2020 | |

| Coconut oil | Early stage | Reduction in ADP-ribosylation factor 1 protein expression | Chatterjee et al., 2020 | |

| COR388 | Mild to moderate | Bacterial protease inhibitor | Detke et al., 2020; Seymour and Zhang, 2021 | |

| Escitalopram | Mild stage | Serotonin reuptake inhibitor | Sheline et al., 2020 | |

| Gabapentin Enacarbil | moderate to late stage | Glutamate receptor-independent mechanisms | Liu et al., 2021 | |

| Ginkgo biloba | Early stage | Antioxidant and anti-amyloid aggregation | Vellas et al., 2012; Liu et al., 2021; Xie et al., 2022 | |

| Guanfacine | Healthy but old aged | Alpha-2A-adrenoceptor agonist, a potent 5-HT2B receptor agonist | Barcelos et al., 2018 | |

| Icosapent ethyl (IPE) | Late stage | Omega-3 fatty acids protect neurons from disease | Cummings et al., 2018 | |

| Idalopirdine | Late stage | 5-HT6 receptor antagonist | Hung and Fu, 2017 | |

| RVT-101 (intepirdine) | mild to moderate | 5-HT6 receptor antagonist | Huang et al., 2020; Akhondzadeh, 2017 | |

| Insulin | Mild stage | Affects metabolism | Craft et al., 2017 | |

| ITI-007 (lumateperone) | mild to moderate | 5-HT2A antagonist | Porsteinsson and Antonsdottir, 2017; Cooper and Gupta, 2020 | |

| Losartan, amlodipine, aerobic exercise training, and etc. | mild to moderate | Anti-Angiotensin II receptor, Anti-calcium channel, cholesterol agent | Cummings et al., 2019; Ihara and Saito, 2020 | |

| Szabo-Reed et al., 2019 | ||||

| Masitinib | mild to moderate | Tyrosine kinase inhibitor | Folch et al., 2015; Ettcheto et al., 2021 | |

| Methylphenidate | —— | Dopamine reuptake inhibitor | Khaksarian et al., 2021 | |

| Mirtazapine | —— | Alpha-1 antagonist | Correia and Vale, 2021 | |

| MK-4305 (suvorexant) | Mild stage | Orexin antagonist | Zhou F. et al., 2020 | |

| EVP-6124 | —— | Selective α7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor partial agonist | Potasiewicz et al., 2020 | |

| Nabilone | Early to mild stage | Anti-cannabinoid receptors 1 and 2 | Ruthirakuhan et al., 2020 | |

| Nilvadipine | mild to moderate | Dihydropyridine calcium channel blocker | Lawlor et al., 2018 | |

| AVP-923 (nuedexta) | Moderate to late stage | Uncompetitive NMDA glutamate receptor antagonist, a sigma-1 receptor agonist, and a serotonin and nor epinephrine reuptake inhibitor | Khoury et al., 2021; Liu et al., 2021; Khoury, 2022 | |

| Pioglitazone | Early to Mild stage | Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARγ) agonists | Galimberti and Scarpini, 2017 | |

| Troriluzole | Mild to moderate | Glutamate modulator | Yiannopoulou and Papageorgiou, 2020 | |

| TRx0237 (LMTX) | Preclinical or early stage | Tau stabilizers and aggregation inhibitors | Panza et al., 2016 | |

| Vitamin D3 | Early stage | Vitamin-D receptor Agonist | Yamini et al., 2018 | |

| Zolpidem zoplicone | Old aged persons | Allosteric modulator of GABA-A receptors | Wu, 2017 |

Extracellular vesicles associated with Alzheimer’s disease

Extracellular vesicles (EV) or exosomes (EXOs) were initially considered as cellular trash bags. These lipid-based membrane-bound biological nanoparticles have now emerged as a new paradigm of cell-to-cell communication which has implications for both normal and pathological physiology (Raposo and Stahl, 2019). Recently, extracellular vesicles have been widely used as biomarkers and are found to play an important role in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease. The presence of disease-related proteins in these extracellular vesicles from AD patients have been actively studied to use them as biomarkers to predict the development of AD before the appearance of clinical symptoms (Lin et al., 2019). They are excreted in the urine and saliva of both healthy and diseased individuals which makes them an excellent choice for diagnostics in diseases like AD as compared to other invasive methods which require lumbar puncture or brain autopsy for diagnosis (Watson et al., 2019). EVs are released from various cell types including the cells associated with neuron-glia communication, neuronal progression, and regeneration from CNS (Surgucheva et al., 2012; Bronisz et al., 2014; Janas et al., 2016). It is widely accepted that EVs are good biomarkers but their nature, regulation, sorting and molecular composition need to be further investigated. Interestingly, the role of exosomes in stimulating aggregation of amyloid-beta (Aβ) peptides in vitro and in vivo was demonstrated and as was their role in the uptake of Aβ by cultured astrocytes and microglia under in vitro conditions (Dinkins et al., 2014). By preventing the secretion of EVs via inhibition of neutral sphingomyelinase 2 (nSMase2), a key regulatory enzyme generating ceramide from sphingomyelin, with GW4869, they observed a significant reduction of Aβ plaques in the mice brain. Moreover, exosomal markers such as Alix and flotillins have been found to be associated with the amyloid plaques of the brain of post-mortem tissues of human AD patients when compared to post-mortem samples of healthy individuals, thereby reflecting specific association of EVs with amyloid plaques (Hu et al., 2016). Further, an increase in levels of tau in exosomes have been reported in CSF at an early phase of AD (Saman et al., 2012; Asai et al., 2015). Levels of several exosomal miRNAs that are altered in AD points to their roles in regulating certain events related to AD neurodegeneration as the ability of miRNAs to target genes related to tau phosphorylation, APP processing, and apoptosis is already known (Liu et al., 2014; Ma et al., 2017). The miRNA-193b and miRNA-125b-5p are the two most common exosomal miRNAs identified and are reported to be expressed differentially in exosomes isolated from serum, plasma and CSF of AD patients (Soares Martins et al., 2021). Therefore, miRNA-193b and miRNA-125b-5p are thought to be potential putative peripheral biomarkers of AD pathogenesis. EVs as potential biomarkers for AD can open up a wide arena of discoveries associated with it; however, a proper evaluation and correlation is needed for it as well.

Circadian genes associated with Alzheimer’s disease

It has been reported that that the levels of the main risk factor for AD progression i.e., Aβ in the brain are regulated by circadian rhythms and the sleep-wake cycle (Kang et al., 2009). Circadian rhythms (CR) are biological clocks that coordinate internal time with the external environment to regulate various physiological processes like the sleep-wake cycle, mental, behavioral and physical changes. Circadian rhythms are managed by a molecular clock in the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) that resides in the anterior part of the hypothalamus. Molecular clockwork consists of different core clock genes such as period circadian regulators 1 and 2 (PER1 and PER2), circadian locomotor output cycles kaput protein (CLOCK), brain and muscle ARNT-like 1 (BMAL1), cryptochrome circadian regulators 1 and 2 (CRY1 and CRY2), These genes are organized in a transcription-translation feedback loop that oscillates every 24 h. Any mutation or alteration in these genes or their subsequent proteins has functional impacts on the CR (Shkodina et al., 2021). Disruptions in CR cause cognitive impairment, psychiatric illness, metabolic syndromes, and are thus considered as a significant risk factor in the onset of cerebrovascular and neurodegenerative disorders such as Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, and Huntington’s diseases. Moreover, disrupted sleep wake-cycle and alterations in circadian rhythms are seen to lead to AD progression by dysfunctional tau metabolism. This is achieved by changing the conformation and solubility of tau in the brain involving the post-translational modifications by decreasing the activity of major regulators of tau phosphorylation, especially cyclin-dependent kinase 5 (cdk-5) (Di Meco et al., 2014). During the early development of AD, there is a disruption in the normal expression of clock genes (especially Cry1, Cry2, and Per1) not only in the central pacemaker but also in other brain areas like the cortex, hippocampus, and cerebellum supporting circadian regulation (Bellanti et al., 2017). Since sleep and circadian rhythm dysfunction (SCRD) are very common in the early stage of AD, it is considered as a potential early biomarker for detecting AD. A proper understanding of the circadian clock and investigations of core clock components including Bmal1, Clock, Per1, Per2, Cry1, Cry2, Rev-erbα, and Rorα by genomic, proteomic, and metabolomic studies and its influence on several key processes involved in neurodegeneration might be helpful to be manipulated at early stages to promote healthy brain aging and decrease the chances of AD progression on one hand and uncover their potential use as biomarkers and hallmarks of circadian disruption during early stages of Alzheimer’s disease progression.

Post-translational modifications in Alzheimer’s disease

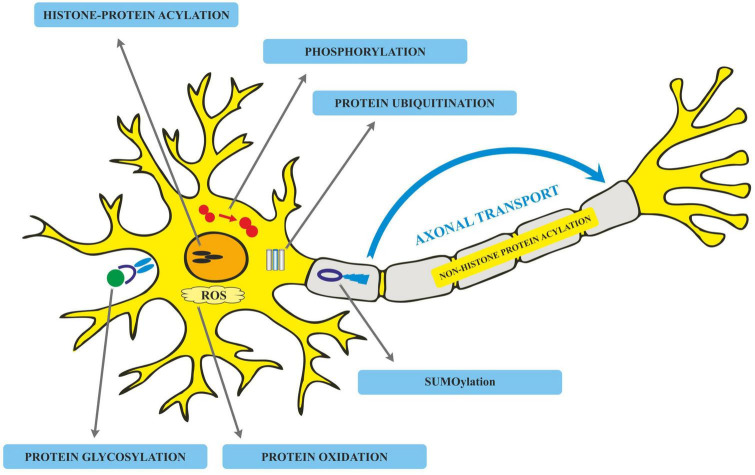

Translated messages in the form of protein undergo important modifications usually after their synthesis. These post translational modifications (PTMs) usually occur in the various cellular compartments like the Endoplasmic reticulum, Golgi complex, Nucleus, as well as Cytoplasm (Blom et al., 2004). PTM’s play an important role in regulating the structure, localization and, activity of proteins (Deribe et al., 2010). PTMs impact the hydrophobicity of proteins and induce changes in their structural conformations and thus define protein function as well as their interactions with other proteins (Ravid and Hochstrasser, 2008; Ardito et al., 2017). PTMs involve the addition of varied chemical moieties to a target protein that include phosphate, acyl, methyl, and glycosyl groups catalyzed by specific enzymes. PTMs not only define the structural integrity of proteins, these modifications usually cause the proteins to lose or enhance their normal function as well (Santos and Lindner, 2017). Unusual PTMs of various proteins like APP, secretases, tau, various kinases, and phosphatases are linked to the development of neurodegenerative diseases. The appearance of NFTs, senile plaques and aggregation of toxic amyloid β peptides are some of the hallmarks of abnormal PTMs in Alzheimer’s disease. These posttranslational protein modifications are associated with memory weakening, cognitive impairments, reduced synaptic plasticity and thus rapid progression to AD (Chong et al., 2018). Exploring post-translational modifications and understanding their molecular mechanism will open a window to develop effective and rational therapeutic interventions to counter these neurodegenerative disorders. Various PTMs associated with AD are shown in Figure 2. PTM specific modifications associated with AD vs. normal brain are also shown in Figure 3 and discussed in detail here.

FIGURE 2.

Various post-translational modifications (PTMs) associated with Alzheimer’s disease.

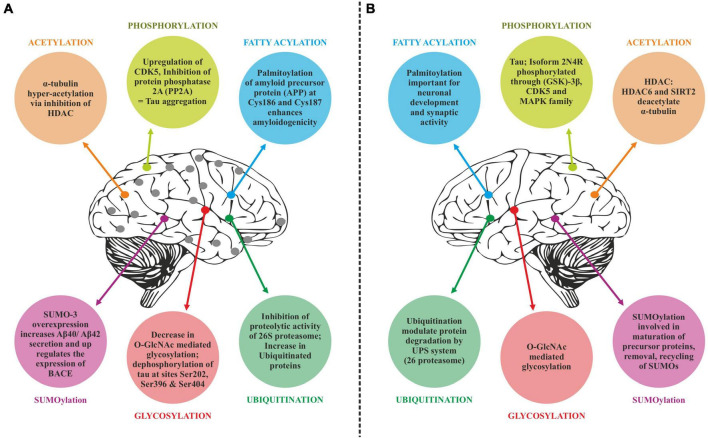

FIGURE 3.

Post-translational modifications (PTM) specific modifications associated with Alzheimer’s disease vs. normal brain. (A) PTMs associated with Alzheimer’s disease. (B) Normal PTMs.

Phosphorylation

Phosphorylation is one of the most frequently occurring PTMs in proteome biology, and about 30% of proteins undergo such modifications (Sacco et al., 2012). It involves the addition of a phosphate group to amino acids particularly to serine, threonine and tyrosine residues (Humphrey et al., 2015). This modification impacts the structure and function of proteins and determines their fate in terms of signaling, trafficking as well as metabolism; thus playing an important part in regulating the normal physiological processes (Ravid and Hochstrasser, 2008). Protein phosphorylation is one of the most predominant PTMs that drives enormous cellular cascades in living cells. The phosphorylation of proteins is reversible and very specific. These events of phosphorylation and dephosphorylation are catalyzed by diverse kinases. A variety of kinases like Akt, Erk, and PKA. GSK3β and Cdks have been found to be overexpressed with enhanced activity accompanied by a significant drop in phosphatases activity in AD patients (Alquezar et al., 2021). Accumulating evidence report that various proteins on altered phosphorylation in these neuro disorders drive the cell death signaling cascades (Suprun, 2019).

Tau phosphorylation

Tau is involved in the stabilization of microtubules, as mentioned earlier. Six different isoforms of tau are usually expressed in normal mature human brain which are found to be hyperphosphorylation in AD brains. These six isoforms of tau protein with varied amino acid chain length (331 to 441) emanate from alternative splicing of a single gene. Tau protein has different domains like N terminal projection domain ranging from 1 to 165 amino acids, proline rich domain from 166 to 242, microtubule binding region (MTBR) starting from 243 to 367 as well as carboxy terminal domain 368–441. Tau proteins bear 85 phosphorylation sites; with nearly half of them found to undergo phosphorylation and the majority of these phosphorylated stretches are found in proline rich domain of tau protein, flanking microtubule binding region (Goedert et al., 1989; Hanger et al., 2009). These phosphorylation events and isoform expression are developmentally regulated and it determines the complexity of embryonic cytoskeleton plasticity (Hanger et al., 2007). However, any unusual alterations in its structural conformation or in phosphorylation events impact its binding affinity with microtubule. Tau phosphorylation is residue specific and is mediated by different types of kinases. These kinases are proline rich domain specific kinases like GSK-3, Cdk5, and AMPK, non-proline directed phosphorylating kinases as well as Fyn kinases (Iqbal et al., 2016). Phosphorylation of tau protein by GSK3β at residues other than that of microtubule binding region like, thr231 pro232, and s214 has been found to impede its association with the microtubule thus affecting its anterograde transport (Figure 4). This residue specific phosphorylation leads to the induction of some conformational alterations which in turn lead to hyperphosphorylation of tau protein. It has been found that phosphorylation of Ser 404 accommodated by C-terminal domain alters the tau conformation (Luna-Munoz et al., 2007). Although GSK3B has been found to phosphorylate 36 residues of tau protein, however, preferable sites spotted by 2D phosphor-peptide mapping include Ser199, Thr231 as well as Ser413, respectively. Besides aforementioned mapping, monoclonal antibody technology has been applied to spot the phosphorylation sites that play a role in AD pathology, and it has been found that phosphorylation at specific motifs like Thr212/Ser214 and Thr231/Ser235 are exclusively seen in PHF (Ebneth et al., 1998; Despres et al., 2017). Interestingly phosphorylation of tau proteins at ser293 and ser305 neutralizes its ability to form aggregates without affecting tubulin polymerization. GSK3β like other kinases recognizes primed target proteins as it has been noted that Thr231 residue of tau proteins needs to be primed by other kinases like Cdk5 which is followed by GSK3b mediated phosphorylation. This phosphorylation of tau protein, in turn, impacts its binding ability with the microtubules thus hampering their polymerization and other neuronal functions (Stoothoff and Johnson, 2005). Cdk5 another proline region-specific kinase involved in hyperphosphorylation of tau hampers the ability of tau protein to bind and stabilize microtubules leading to the disruption of axonal transport and neuronal death-an important contributor to the pathology of neurodegenerative diseases like AD (Piedrahita et al., 2010). Growing evidences report that dephosphorylated tau protects nuclear DNA from heat damage and other kinds of oxidative stress insults however tau in hyperphosphorylated form is believed to halt protective functionalities associated with non-phosphorylated forms in neuronal entities (Sultan et al., 2011). Cdk5 isoform is expressed in the brain, unlike cell cycle-related Cdks serine/threonine kinase, shows affinity toward the proline rich domain and phosphorylates some preferable residues like Ser202, Thr205, Ser235, and Ser404; which are found to be essential in regulating Tau-Mt binding. Cdk5 is activated by neuron specific p35 and p39 proteins-which are not considered to be cyclins. Thus, Cdk5 mostly acts in neural cells and is activated by binding to neuronally enriched activators, p35 and p39, to display its functions predominantly in post-mitotic neurons. While the defect of Cdk5 is disparaging to the CNS, its hyperactivation is also lethal to neurons. Some studies have also unraveled the various roles of cdk5 in neuronal remodeling as well as modulation of synaptic transmission (Fleming and Johnson, 1995; Cruz et al., 2003). Fyn, a tyrosine kinase, phosphorylates tyr18 residue and has been reported to precede the deposition of NFT as well as PHF associated with AD pathology (Lee et al., 2004). Exhaustive research has been carried out and it has been observed that hyperphosphorylation of tau protein makes it susceptible to aggregation and leads to the formation of tau assembly in vitro conditions whereas dephosphorylation events reverse its assembly to normal levels as well as stabilizes microtubules back. Coordinated interactions of kinase as well as phosphatases have been seen to maintain the phosphorylation status of tau protein and imbalance in such interplay usually drives its aggregations associated with several tauopathies. Various in vitro studies have been carried out which unraveled the involvement of specific phosphatases involved in the regulation of phosphorylation in AD. It has been found that PP1, PP2A as well as PP5 are residue specific and dephosphorylates the tau protein at particular residues like ser199, ser20, thr212, and ser409 respectively, thus maintaining the balance between kinase and phosphatase action (Liu et al., 2005). These phosphates also drive the positive feedback cycles by regulating the ERK/MAPK signaling cascade that otherwise activates the GSK3β which progresses the aggregation of tau proteins. Among these phosphates PP2A is most extensively studied as it regulates about 70% of tau dephosphorylation in the human brain. Besides phosphorylation, tau proteins undergo other post translational modifications like acylation and glycosylation playing a role in standard microtubule dynamics (Qian et al., 2010). Emerging evidences suggest that overexpression of GSK3β as well as other kinases like Cdk5 plays a part in the progression of these neurodegenerative disorders like AD thus gaining a special interest in treating these disorders by employing therapeutic intervention in the form of specific inhibitors which can inactivate these kinases. Lithium-One of the most commonly used GSK3β inhibitor that inactivates the gsk3b by enhancing its ser-9 inhibitory phosphorylation which acts as a pseudo substrate and prevents its activity (Zhang et al., 2003). It has been reported that the application of lithium treatment in some experimental murine models that are overexpressing human APP, showed some encouraging results in retarding the neuropathology and cognitive impairments (Hu et al., 2009; Undurraga et al., 2019). Lithium is the only GSK-3β inhibitor that has been in clinical use for a significant time. However, we know that lithium lacks target specificity, and shows adverse side effects and high toxicity. Although two molecules AZD-1080 (AstraZeneca) and NP-12/Tideglusib (Noscria) reached the clinic in 2006, AZD-1080 was later on abandoned due to its nephrotoxicity as observed in phase I clinical trial while as NP-12 is currently in phase IIb trials for Alzheimer’s disease and paralysis supranuclear palsy. Meanwhile presently, an increasing number of GSK-3β inhibitors are being tested in preclinical models, and it is anticipated that some of the potent inhibitors will enter clinical trials (Eldar-Finkelman and Martinez, 2011). Recent developments in the field of small-molecule inhibitors of CDKs have led to several compounds with anticancer potencies both in vitro and in vivo and models of cancer. However, the specificity of the inhibitors, which inhibit close isoforms, is not fully achieved yet, especially for CDK5, which is involved in neurodegenerative diseases (Łukasik et al., 2021). Other specific inhibitors have been developed with improved therapeutic effects, some of which are non-ATP competitive inhibitors that are selective and significantly less toxic than others like L803-mts as well as TDZD-8, VP0.7 (Kaidanovich-Beilin et al., 2004; Kaidanovich-Beilin and Eldar-Finkelman, 2006). Other conventional ATP competitive inhibitors include paullones, indirubin, SB415286 and SB216763 as well as AR-A014418 respectively (Leost et al., 2000; Bhat et al., 2007). Tau phosphorylation as well as amyloid beta deposition is impeded by treating the transgenic mouse models that are overexpressing APP, as well as reducing the memory weakening in the Morris water maze (Serenó et al., 2009; Ly et al., 2012). A recent finding suggests that selective GSK3 inhibitor SAR502250 is effective in contributing toward neuroprotection as well as diminish behavioral impairments in rodent models with neuropsychiatric abnormalities. Treatment of P301L human transgenic mice with this inhibitor was seen to reduce the tau phosphorylation thus impairs the formation of tau aggregates. Besides implications of specific inhibitors, genetic knockdowns of GSK isoforms have been also shown to recover cognitive abnormalities associated with various murine models. So these findings suggest that intervention of these kinase inhibitors can possibly act as disease modifying tactics to encounter AD related conditions (Griebel et al., 2019).

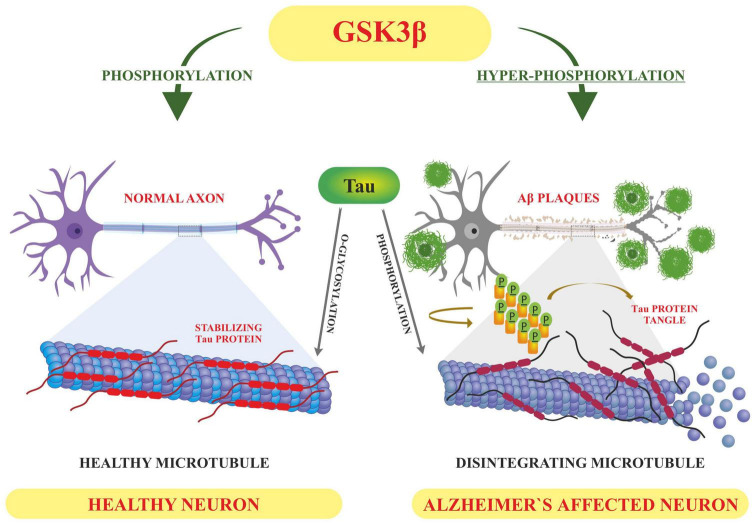

FIGURE 4.

Displaying how the altered post-translational modifications (PTM) leads to Alzheimer’s pathology-based on the literature surveyed GSK3β dependent hyperphosphorylation of tau proteins results in accumulation of NFT’S and deposition of Aβ plaques–hallmarks of Alzheimer’s disease whereas O-linked glycosylation of tau proteins hampers its aggregation thus promoting normal polymerization processes.

Acetylation

Alzheimer’s disease (AD), also known as a protein misfolding disease, is a degenerative and incurable terminal disease of the central Nervous system (CNS) characterized by the presence of two main types of protein aggregates that include amyloid plaques and NFTs. Both genetic and non-genetic (environmental) factors are involved in the development of AD (Singh and Li, 2012; Tönnies and Trushina, 2017). However, the exact gene-environment interactions involved in the development of AD have not been delineated yet. Epigenetic changes are involved in integrating genetic and environmental interactions. These epigenetic processes are thus considered heritable changes in gene expression without causing any change in the coding sequence of genes. Most common epigenetic alterations reported that impact phenotypic outcomes include histone modifications like acetylation, phosphorylation, methylation, ubiquitination, ADP ribosylation, and SUMOylation; DNA methylation and non-coding RNA (Miller and Grant, 2013). These epigenetic changes regulate gene expression by altering the chromatin structure thereby increasing access to transcription factors (Venkatesh and Workman, 2015). The histone modifications involve acetylation and deacetylation of histone proteins which are the chief protein components of chromatin in the form of histone octamers. Each histone octamer consists of four core histones which include H2A, H2B, H3, and H4 (Shahbazian and Grunstein, 2007). These positively charged histone octamers wrap around negatively charged DNA to form nucleosomes-the basic components of chromatin structure. Acetylation and deacetylation of these histones define the chromatin configuration. Acetylation at the N-terminal tails of H3 and H4 histones neutralizes their positive charge thereby reducing the binding of histone to DNA. Acetylation of core histones, considered as the markers of an open configuration of chromatin, opens up the chromatin to facilitate gene transcription (Struhl, 1998). On the other hand, deacetylation does the opposite. Thus, we can say that histone acetylation promotes transcriptional activation, while as histone deacetylation leads to transcriptional repression of genes. These histone modifications regulate critical cellular processes that include cell proliferation, differentiation, apoptosis, inflammation, neuronal plasticity, and metabolic reprogramming (Thiel et al., 2004). During the process of histone acetylation, Histone Acetyltransferases (HATs) transfer an acetyl group from acetyl coenzyme A to the lysine residues present at the N-terminal domains of core histones. This acetylation neutralizes the positive charge in histones and thus reduces affinity between histones and negatively charged phosphates in DNA. Therefore, it opens up chromatin to promote the transcriptional activity of genes (Bannister and Kouzarides, 2011). In contrast to this, histone deacetylase (HDAC) removes the acetyl groups from histones which results in silencing of gene expression. Thus, both histone acetyl transferases (HATs) and histone deacetylases (HDACs) play an important role in chromatin remodeling (Kuo and Allis, 1998). HATs are broadly divided into two classes based on their subcellular localization: A-type HATs, and the B-type HATs which are seen in the nucleus and cytoplasm respectively (Mersfelder, 2008). A-type HATs are further divided into three subclasses based on their structural homology: (1) GNAT family represented by Gnc5, PCAF, and ELP3; (2) MYST family containing Tip60, MOZ/MYST3, MORF/MYST4, HBO1/MYST2, and HMOF/MYST1; and (3) p300/CBP family containing p300 and CBP. Multiple studies have been conducted to investigate the role of these HATS in the etiology of AD (Lu et al., 2015; Li et al., 2021). HAT activity of Tip60 was shown to regulate the expression of genes that are related to behavior, learning, memory, and neuronal apoptosis in Drosophila (Xu et al., 2014). Similarly, HAT activity of CBP and p300 is related to long-term memory and neuronal survival. An interesting study was conducted in behavior-trained rats where hyperacetylated H2B/H4 in the promoters of the synaptic-plasticity-related genes was observed upon expression of CBP/p300 and PCAF (Chatterjee et al., 2013). Furthermore, AD pathological contexts also show a critical CBP/p300 loss with histone H3 deacetylation (Rouaux et al., 2003). A genome-wide study was conducted to examine the histone H3 acetylation pattern in the entorhinal cortex of AD patient samples and compared with the control subjects using chromatin immunoprecipitation and highly parallel sequencing (Marzi et al., 2018; MacBean et al., 2020). Genes involved in the progression of AD like amyloid-β and tau showed highly enriched acetylated peaks. Ramamurthy E. et al. carried out cell type-specific histone acetylation pattern analysis of AD patients and controls and observed differential acetylation peaks in the early onset risk genes (APP, PSEN1, PSEN2, and BACE1), and late onset genes (BIN1, PICALM, CLU, ADAM10, ADAMTS4, SORL1, and FERMT2) associated with the pathogenesis of AD (Marzi et al., 2018; Ramamurthy et al., 2020).

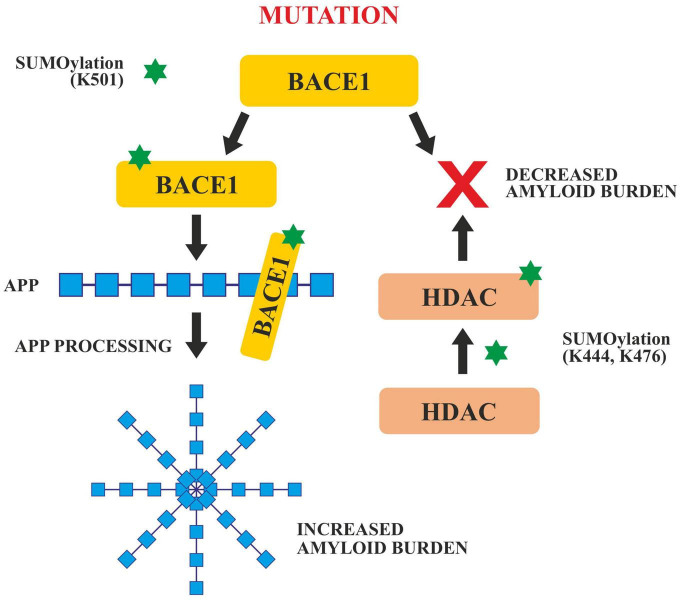

The histone deacetylases are also classified into four groups based on their homology to yeast enzymes: Class I HDACs consist of HDACs 1, 2, 3, and 8; Class II HDACs which are further divided into two subclasses, class IIa including HDACs 4, 5, 7, 9, and class IIb HDACs 6, 10; Class III HDACs which include SirT1-7; and class IV HDAC that has a single member-HDAC11 (Seto and Yoshida, 2014). Although class I HDACs are ubiquitously expressed, in comparison to HDAC1, HDAC2 and –3 show the highest expression levels in brain regions associated with memory and learning, such as the amygdala, hippocampus, and cortical areas (Volmar and Wahlestedt, 2015). The subcellular localization and expression levels of individual HDAC isoforms differ in different cell types during various stages of AD progression. HDAC2 is reported to negatively regulate memory and synaptic plasticity (Guan et al., 2009). The mice overexpressing HDAC2 showed hypoacetylation of histone H4 on their K12 and K5 residues. These mice also showed memory impairment and decreased number of synapses (Kumar et al., 2005). Since HDAC2 shows high levels of expression in the post-mortem brain samples of AD patients. HDAC2 downregulation by using short-hairpin-RNA restored the memory impairment and synaptic plasticity in CK-p25 mice indicating the critical nature of HDAC in memory formation and synaptic plasticity (Gräff et al., 2012). In another study, HDAC3 was shown to be critical for regulating synaptic plasticity in a single neuron or neuronal populations. Some established human neural cell culture models with familial AD (FAD) mutations showed a significant increase in HDAC4 levels in response to Aβ deposition in this cell model (Citron, 2010). Targeting HDAC4 by the selective inhibitor TasQ rescued the expression of genes involved in regulating neuronal memory/synaptic plasticity (Mielcarek et al., 2015). While high levels of HDAC6 protein were seen in the cortices and hippocampi of AD post mortem brain samples, reducing endogenous levels of HDAC6 were reported to restore learning and memory ability in the mouse model of AD. This happens partly because HDAC6 is shown to significantly decrease tau aggregation and promote tau clearance via acetylation (Fan et al., 2018). Thus, several studies have demonstrated that abnormal acetylation of core histones is involved in the etiology of AD. In addition to histones, altered acetylation of non-histone proteins which include NF-κb, p53, alpha tubulin and tau have also been reported in the pathogenesis of AD. Tau acetylation is mediated by p300 and CBP histone acetyl transferases at different residues. Acetylation of tau reduces its solubility and thus affects its intrinsic propensity to aggregate. Intracellular tau acetylated at Lys280, preferably by CBP, is seen during all stages of AD disease. Tau acetylation is known to suppress the degradation of phosphorylated tau (Chen et al., 2001; Park et al., 2013). Moreover, both acetylated and hyperphosphorylated-tau were reported to show similar spatial distribution pattern. Conversely, HDAC6 activity promotes deacetylation tau, which then contributes to enhanced tau-microtubule interactions and microtubule stability (Carlomagno et al., 2017).

Histone deacetylases (HDAC) inhibitors for the treatment of AD: A growing body of evidence considers HDAC proteins as therapeutic targets for the treatment of AD. HDAC inhibitors may be alternative drugs to potentially protect against the impairment of cognition in AD patients. It is suggested that HDAC inhibitors may be a good alternative to conventional drugs to potentially improve the cognition features in AD patients (Xu et al., 2011). It has been shown that inhibitors targeting HDACs are involved in improving memory and cognition in the mouse model of AD. In AD animal models, HDAC inhibitors show neuroprotective activities, and thus provide a promising strategy for the treatment of AD (Sun et al., 2017). However, care should be taken when using pan-HDAC inhibitors (non-selective HDAC inhibitors) to treat AD because these HDAC inhibitors are poorly selective and often cause some undesired side effects (Cheng et al., 2015; Sun et al., 2017). Thus, evaluating the role of individual HDAC isoforms fin memory, learning and in the pathogenesis of AD becomes all the more important for the discovery and development of more selective HDAC inhibitors. Isoform selective HDAC inhibitors may, however, greatly eliminate side effects and toxicities associated with pan inhibitors and offer improved efficacy (Balasubramanian et al., 2009).

Glycosylation

Glycosylation involves the attachment of specialized forms of sugars called glycans to the target proteins through glycosidic bonding like N and O linkages (Spiro, 2002). Glycans are the sugar moieties linked to protein, lipids or other molecular entities and their structural complexity varies depending on the type of monocarbide core it bears. These glycans regulate the various functionalities associated with the normal functioning of cells like cellular signaling (Varki, 2017). These tissue specific glycosylation patterns have also been reported. Unusual alterations in such modification have implications for different diseases including several neurodegenerative disorders (Abou-Abbass et al., 2016). Nearly 50% of proteins have been observed to undergo such modifications. Glycosylation of proteins usually occurs in the ER and Golgi complex to facilitate the trafficking of proteins to different locations like mitochondria, cytoplasm, plasma membrane, nucleus etc., (Kizuka et al., 2017). This modification is usually catalyzed by enzymes to add glycans to target proteins through glycosidic bonding. Based on the type of glycosidic bonding between sugar moiety and target protein, it is categorized into N-linked and O-linked modifications (Shental-Bechor and Levy, 2008; Haukedal and Freude, 2021). N-linked glycosylation involves the attachment of N-acetyl glucosamine to the asparagine residues of target proteins through β-1N linkages. This modification starts with the synthesis of glycan (14 carbon moiety) from N acetyl glucosamine and mannose sugar, which undergoes further sugar modification, followed by the transfer of modified sugar chain to a particular protein thus acquiring complex form. This whole process is carried out by a specific set of enzymes like mannosidases and glucosidases of ER as well as glycosyltransferases of the Golgi complex (Moremen et al., 2012; Reily et al., 2019). On the other hand, O-linked glycosylation occurs in the several cellular compartments like cytoplasm, nucleus and mitochondria and involves the linking of O-glycans usually in the form of N-acetyl galactosamine or N-acetyl glucosamine to target proteins through Ser/Thr residues without undergoing any kind of alteration in the form of trimming of precursor sugar as is seen in N linked type. Many other sugar modifications are also reported which are carried out by enzymes like glycosyl transferases. These modifications involve the addition of galactose, N acetyl glucosamine, sialic acid etc., to target proteins (Clausen and Bennett, 1996; Akasaka-Manya and Manya, 2020). These sugar modifications usually determine the stereochemistry of target proteins which in turn define the structural organization as well as protein stability (Shental-Bechor and Levy, 2008). In the progression of Alzheimer’s disease (AD), glycosylation is associated with tauopathies. Several proteins like APP and BACE1 are seen to be glycosylated in tauopathy patients (Kizuka et al., 2015). It has been seen that O-glycosylation of tau hampers its aggregation without causing any kind of obstruction in its normal polymerization activity (Mietelska-Porowska et al., 2014). Thus, it has been proposed that glycosylation of tau plays a protective role by blocking tau aggregation. Few O-linked glycosylation sites have been spotted in tau protein at residues which are targets of tau phosphorylation as well. These residues include S400, S238, and S409 (Yuzwa et al., 2011). Unlike O-glycosylation, N-type modifications of tau protein have been observed to affect the subcellular localization of tau protein in AD patients (Alquezar et al., 2021). Transgenic mice models of AD have shown a significant disparity in O-GlcNAcylation and phosphorylation with tau protein being hyperphosphorylated at specific serine residues followed by a drop in O-GlcNAcylation levels (Bourré et al., 2018). Both O-linked glycosylation and phosphorylation of tau protein are well-adjusted in normal conditions and it has been observed that hyperphosphorylated protein shows a decreased glycosylation thus impacting its nuclear localization (Lefebvre et al., 2003). Thus we can say that O-glycosylation competes with phosphorylation and shields tau protein from hyperphosphorylation at particular stretches of serine residues by Protein Kinase A (PKA), therefore playing a protective role in normal brain functions. However, it has been found that N-glycosylation helps tau phosphorylation by hampering dephosphorylation or by activating PKA mediated tau phosphorylation, and thus promotes the progression of pathology associated with Alzheimer’s disease (Liu et al., 2004). Altered glycosylation patterns of many other proteins involved in the progression of neuro disorders like APP have been reported as well. Glycosylated APP has been reported in CSF of patients showing AD pathology (Schedin-Weiss et al., 2014). It has been reported that N-bonded glycan display modulation of amyloid beta production and structural variations in such glycans alters APP transport as well as trafficking. O-linked glycosylation of APP directs it to plasma membranes to promote the processing of APP through non-toxic, non-amyloidogenic pathways, thus lowering the production of toxic amyloid beta peptides (Chun et al., 2015a). N-glycans are also involved in the trafficking and secretion of APP. It has been shown that blocking the activity of mannosidase hampers the production of hybrid and complex forms of N glycan which affects APP transport and other proteins to the synaptic membrane (Bieberich, 2014). Recently site-directed mutagenesis approach has shown that specific O-glycosylation at Thr576, directs its transport toward the plasma membrane and the subsequent endocytosis of APP elevates Aβ levels (Chun et al., 2015b). Treatment of experimental 5XFAD mice with a small molecule inhibitor blocking the glycosylation of gamma secretase lead to reduced production of AB peptides, thus slowing the progression of neuroinflammation followed by recovery in memory impairments (Kim et al., 2013). Patients displaying AD pathology have been found to contain BACE1 post translationally altered with bisecting GlcNAc however blocking this modification using knockout approach slows down APP processing followed by reduced amyloid deposition. Experimental knockout Mgat3-gene mice have been shown to alleviate cognitive abnormalities as well as deposition of amyloid beta aggregates (Elder et al., 2010; Haukedal and Freude, 2021). Besides these enzyme dependent modifications, there are enzyme independent post translational modifications called glypiations which involve the covalent attachment of sugars to lysine residue of target proteins. This alteration usually produces advanced glycation end products (AGES) which are speculated as glycotoxins playing a role in age related diseases (Cho et al., 2007). It has been observed that glycation modifications cause aggregation of the tau proteins by hampering the ubiquitination process required for tau degradation. Moreover. this modification usually reduces the binding affinity of tau protein toward microtubule thus affecting polymerization followed by defective axonal transport and other synaptic functions (Ko et al., 1999).

Fatty acylation

The attachment of long chain fatty acids like palmitate (16 carbon saturated fatty acid) and myristate (14 carbon saturated fatty acid) by amide and thioester linkages respectively is called fatty acylation (Lanyon-Hogg et al., 2017). The mechanism of fatty acylation tunes various cellular processes such as protein-protein interactions, membrane targeting, and intercellular as well as intracellular signaling. Dysregulation in the process of fatty acylation leads to the development of disease conditions including neuronal defects (Wright et al., 2010; Tate et al., 2015). Of all the three lipid modifications viz myristylation, prenylation and palmitoylation; myristoylation and palmitoylation are the most common acylation processes and only palmitoylation is reversible (Resh, 2016).

Palmitoylation

S-Palmitoylation is a vital post-translational modification that is important for the function and trafficking of various synaptic proteins. Palmitoylation reactions are carried out by palmitoyl acyltransferases (PATs) that catalyze the attachment of palmitate (16 carbon) covalently to cysteine residues through thioester bonds (Cho and Park, 2016). Palmitoylation (addition of sulfhydryl group to palmitoyl group) is important for synaptic activity and an increase in palmitoylation contributes to pathogenesis of AD to a large extent (Bhattacharyya et al., 2013). BACE 1 or β-secretase, a 501 amino acid type 1 transmembrane aspartic acid protease, associated with the retroviral aspartic β-secretase protease and pepsin family, leads to APP cleavage in the amyloidogenic pathway generating Aβ including pathogenic Aβ42 (Vassar et al., 2009). S-Palmitoylation of BACE 1 takes place at specific Cys residues viz Cys-474, 478, and 485, out of which Cys 474 is a part of the transmembrane domain. Mutations that change these cysteine residues to alanine cause displacement of BACE1 from the lipid rafts without affecting the processing of APP and produce peptides of amyloid (Vetrivel et al., 2009). S-Palmitoylation of BACE1 and its role in Alzheimer’s disease was studied by developing a gene knock-in transgenic AD mice, where the cysteine residues of S-palmitoylation were changed to alanine residues. The lack of S-Palmitoylation of BACE 1 was observed to reduce the cerebral amyloid burden in AD mice significantly, it also reduced cognitive defects. This suggests that the intrinsic S-palmitoylation of BACE 1 has an impact on the pathogenesis of amyloid and further cognitive decline (Andrew et al., 2017). Palmitoylation targets APP to the lipid rafts and enhances its BACE-1 mediated cleavage which ultimately increases the amyloidogenic processing. Palmitoylation inhibitors impair the processing of APP and α and β (a family of proteolytic enzymes that cleave APP to produce amyloid beta peptides). Acyl Coenzyme A Cholesterol acyltransferase (ACAT) inhibitor, known to redistribute cellular cholesterol, inhibits APP palmitoylation and significantly reduces Aβ generation (Bhattacharyya et al., 2013).

Myristoylation

Myristoylation, is a eukaryotic post and co-translational modification, is the covalent attachment of myristic acid, a 14-carbon saturated fatty acid, to the N-terminal glycine of proteins. Proteins that are destined to be myristoylated begin with the sequence Met-Gly. N-M-T acts on myristoyl coenzyme A and transfers myristate from it to N-terminal glycine to a varied range of substrate proteins. These myristoylated proteins play critical roles in many signaling pathways to mediate protein-protein and protein-membrane interactions, subcellular targeting of proteins etc. Myristoylation is mediated by the enzymes commonly known as N-myristoyltransferases (N-M-T). In vertebrates myristoylation is carried out by NMT1 and NMT2-members of the GCN5 acetyltransferase superfamily, expressed in nearly all tissues and are reported to be involved in the progression and development of various pathological conditions which include Alzheimer’s disease, cancer, epilepsy etc., (Thinon et al., 2014). A key event in AD is the cleavage of APP by β-secretase to generate APP C99, which then undergoes additional cleavages by γ-secretase to produce Aβ40 and Aβ42 peptides (Su et al., 2010). The presenilin-1 (PSEN1) and presenilin-2 (PSEN2) genes encodes the major component of γ secretase responsible for APP cleavage resulting in the subsequent formation of Aβ peptides (Delabio et al., 2014) and altered APP processing is usually seen in AD patients carrying PSEN mutation. It has been shown that calmyrin, a calcium binding myristoylated protein, plays a versatile role in intracellular signaling and is also important in the functioning of presenilin (Stabler et al., 1999). Calmyrin preferentially interacts and colocalizes with PSEN2. The co-expression of calmyrin and PSEN2 in Hela cells were reported to modify the subcellular distribution of these proteins and cause cell death, thus suggesting that these two proteins act in concert in pathways that regulate cell death (Stabler et al., 1999). PSEN2 and calmyrin mutually regulate each other; calmyrin regulates the PSEN2 function when it detects changes in calcium homeostasis, on the other hand, PSEN2 proteins may disrupt calcium homeostasis altering the calcium binding capacity of calmyrin. Also, the overexpression of presenilins causes perturbations in calcium balance (Guo et al., 1996; Keller et al., 1998). Any imbalance in the regulation of calcium could be fatal to the cell because calcium plays a central role in various cellular processes and in apoptosis (McConkey and Orrenius, 1997).

Normally, APP, β-and γ-secretases and phosphatidylinositol 4, 5-bisphosphate (PIP2), which is an signaling lipid moiety for endocytosis, are located on the lipid rafts. Also, It has been shown that endocytotic invagination of the membrane causes smaller lipid rafts to fuse to form larger rafts where APP, β, and γ secretases come together, this combination brings APP, β, and γ secretases in close proximity to one another causing APP cleavage thus, inducing the amyloidogenic pathway in AD (Su et al., 2010). The myristoylated alanine-rich C kinase substrate (MARCKS) usually binds to the membranes to shield PIP2 from taking a part in endocytosis. This process halts endocytosis, thus reducing the Aβ production (van Rheenen et al., 2005). Phosphorylation of MARCKS by protein kinase C (PKC) or its interaction with Ca2 + leads to its release from the membrane into the cytoplasm, thus releasing PIP2 and promoting endocytosis again, and subsequent generation of Aβ40 and Aβ42 peptides in AD (Arbuzova et al., 2002). Thus, MARCKS provides a novel therapeutic option for reducing the generation of Aβ40 and Aβ42 peptides by regulating the pathway of endocytosis.

Ubiquitination

Ubiquitin is a greatly conserved 8.6 kDa regulatory protein composed of 76 amino acids found in almost all tissues of eukaryotes encoded by UBB, UBC, UBA52, and RPS27A genes (Kimura and Tanaka, 2010). Ubiquitination interchangeable with ubiquitylation is the addition of ubiquitin to a substrate protein. Ubiquitination is known to mark proteins for degradation; it can affect their function and alter protein sub-cellular localization as well (Mukhopadhyay and Riezman, 2007). Ubiquitination is regulated by three main enzymes viz (E1) Ubiquitin activating enzymes, (E2) Ubiquitin conjugating enzymes and (E3) Ubiquitin ligase. Ubiquitination can take place by either the addition of a single ubiquitin protein (mono-ubiquitination) or a chain of ubiquitin proteins (Polyubiquitination) (Mukhopadhyay and Riezman, 2007). These modifications generally occur at the side chain of lysine residues or the N-terminal methionine, although lately cysteine, serine and threonine residues have also been recognized as places for ubiquitination (McClellan et al., 2019). The site, length, and attachment of these ubiquitin proteins help to determine the fate and stability of a substrate (Ramesh et al., 2020). As EI, E2, and E3 enzymes help in the attachment of ubiquitin proteins, the deubiquitinases (DUBs) detach ubiquitin proteins from the substrates (Schmidt et al., 2021). Interestingly, Ubiquitin, protein can itself be post-translationally modified with acetylation and phosphorylation for enhanced diversity and regulation. The ubiquitin proteasomal degradation pathway is one of the major routes responsible for the clearance of misfolded proteins to maintain protein homeostasis. Any perturbation of the ubiquitination degradation pathway leads to toxic aggregation of species promoting the onset of various neurodegenerative diseases including Alzheimer’s (Zhang et al., 2017). AD is mainly caused by the unusual accumulation of misfolded proteins and peptides which result in the formation of amyloid plaques and NFTs, respectively. APP, BACE1 and tau proteins are the major targets of abnormal modification by ubiquitination (Perluigi et al., 2016). β-secretase/BACE1 leads to APP cleavage in the amyloidogenic pathway generating Aβ. The therapeutic inhibition/regulation of β-secretase would therefore reduce the production of all forms of beta-amyloid including the pathogenic Aβ42 (Vassar et al., 2009). The regulation of BACE1 level is done by the ubiquitination and proteasome degradation system. Tau is a protein is also rich in lys residues thus has high susceptibility toward ubiquitination. The central role of tau ubiquitination is to regulate tau clearance by proteasomal or lysosomal autophagy system (Gonzalez-Santamarta et al., 2020).

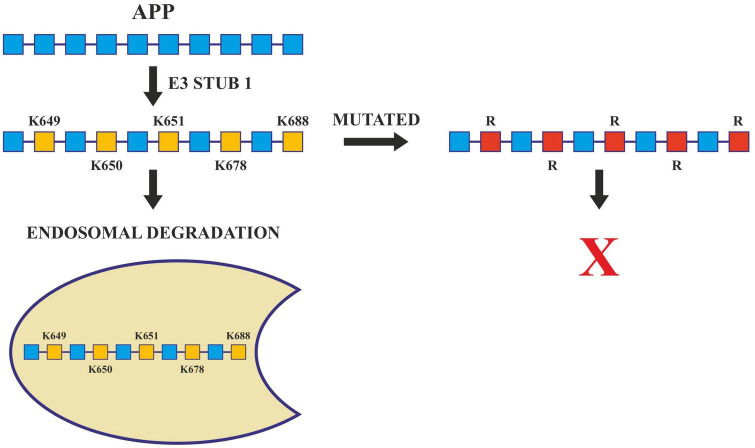

Further, the presenilin (PSEN) proteins are known to play an essential role in AD pathogenesis by mediating the intramembranous cleavage of APP generating (Aβ) (Oikawa and Walter, 2019). In order to sort APP into the endosome and allow their processing by PSEN, ubiquitination of its lysine residues present in its cytosolic domain is carried out by E3 ligases. These ligases are active in Alzheimer’s and they ubiquitinate at Lys 649/650/651/678 of ACR. Any mutation that changes these lysine residues to arginine hinders the ubiquitination of APP and increases Aβ40 levels (Williamson et al., 2017; Figure 5). Apart from this, Lys 203 and Lys 382 of BACE1 are also important ubiquitination sites for degradation. Mutations at these sites also disrupt the degradation of BACE1, thus increasing the production of Aβ (Wang et al., 2012). BACE1 is ubiquitinated by an E3 ligase known as FbX2 via trp280 which causes it to degrade through the proteasome pathway. In turn, the expression level of FbX2 gets affected by PGC-1α [Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARγ) coactivator-1α] which is known to promote the degradation of BACE 1 through the ubiquitin degradation system (Ramesh et al., 2020). The AD brain has altered expression levels of both FbX2 and PGC-1α and any supplementation of FbX2 externally reduces the levels of BACE1 and also improves synaptic function (Gong et al., 2010). This suggests that FbX2 has a role in the reduction of Aβ levels.

FIGURE 5.