Abstract

Objectives

To evaluate mental health-related outcomes of police officers 5.5 years after implementing a new alternating shift schedule which was supposed to improve their health and work–life balance.

Design

Pre–post study design with a baseline survey at the beginning of the piloting of the new shift schedule in 2015 and another survey 5.5 years later in 2020.

Setting

Police departments of a German metropolitan police force piloting the new shift schedule.

Participants

116 shift-working police officers out of a population of 1673 police officers at the follow-up date.

Interventions

New shift schedule based on occupational health recommendations.

Outcomes measures

Work–life balance, job satisfaction and quality of life.

Methods

Mixed analyses of variances were used to test the hypotheses of within-subject and between-subject differences regarding time and gender.

Results

We found partly significant differences between the baseline and follow-up survey for work–life balance (F(1, 114) = 6.168, p=0.014, ηp² = 0.051), job satisfaction (F(1, 114) = 9.921, p=0.002, ηp² = 0.080) and quality of life (F(1, 114) = 0.593, p=0.443, ηp² = 0.005). Neither significant differences between male and female police officers nor interaction effects of time and gender were found.

Conclusion

An increase was found for each of the three outcomes 5.5 years after implementing the new shift schedule. The results contribute to the current state of research on mental health-related outcomes of working conditions in shift work. On this basis, recommendations for designing shift schedules can be deduced to promote mental health and job satisfaction for employees in shift work.

Keywords: OCCUPATIONAL & INDUSTRIAL MEDICINE, MENTAL HEALTH, EPIDEMIOLOGY

STRENGTHS AND LIMITATIONS OF THIS STUDY.

Changes in mental health-related outcomes among shift-working police officers were analysed using mixed analyses of variances to determine within-subject and between-subject differences before and after implementing a new shift schedule.

The study was designed and conducted by an interdisciplinary team of psychologists, occupational physicians, health scientists and epidemiologists.

The measurements were based on self-reports and thus may be subject to response bias.

Only a small proportion of the surveyed police officers could be matched over the measurement points, resulting in a reduced sample size and limited representativity of results.

Introduction

Police officers are exposed to various work-related demands in their jobs, with shift work being an inevitable one of them. Working in shifts, especially at night, is associated with several health risks, such as higher incidences of cardiovascular diseases resulting from a disturbed circadian rhythm1–3 and a potentially increased risk of cancer due to impaired melatonin secretion.4–7 Furthermore, alternating shift work is associated with increased risk of sleep disturbances,8 impaired mood and performance, and disrupted family and social relationships, which in turn can have a negative impact on physical and mental health.9–13 Balancing work and leisure activities, such as partnership, family, caring for relatives, hobbies or voluntary work, thus poses a particular challenge for employees working in alternating shifts.14 Similarly, job satisfaction is closely related to both physical and mental health.15

Particularly among shift-working police officers, prior research in the international context has focused on their sleep quality,16 17 work-related stress(ors),18–20 trauma and associated suicidal ideation.21–23 The risk of suicide is substantially higher compared with other occupational groups.24 However, police officers’ perceived work-related stress does not only result from their work content, but also results from their working conditions. For instance, irregular schedules, mandatory overtime and longer than 11-hour shifts have been associated with higher risk of burnout among police officers.25 Police officers’ indispensable shift work is associated with sickness absence26 and predicts work–family conflict.27 The latter also mediates between police officers’ workload and job stress as well as job dissatisfaction.28 Apart from its association with higher levels of job dissatisfaction,29–32 police officers’ work–life conflict is also related to burnout and stress,33–35 more subjective health complaints and suicidal ideation.27 Although significant gender differences, in general, but especially among police officers who were married and/or had children, were found regarding psychosocial stress,36 further research findings highlight the significant relationship between stress and work–life balance37 or work–family conflict38 39 affecting police officers regardless of their gender. Similarly, several studies indicate that gender does neither predict police officers’ job satisfaction nor differ significantly between males and females,40–42 although contradictory results have been found.43 44 Literature also provides inconsistent findings on police officers’ gender and perceived quality of life. A Greek study suggests that female and male police officers‘ scores do not differ significantly overall, but females reported lower levels of subscales of health-related quality of life which is—like job satisfaction—negatively associated with perceived stress. However, significant interactions were not revealed.44 Other studies have found no significant gender differences concerning police officers’ quality of life.45 However, research on police officers’ quality of life is only recently emerging.46 47

In this context, an evaluation at a German metropolitan police force revealed an improved work–life balance among police officers after adapting the shift schedule according to occupational health recommendations.48 49 Especially flexibility due to improved planning of free time and shorter shifts were regarded as more compatible with family and leisure time activities.49 In a similar vein, another German metropolitan police force aspired to adapt their alternating shift schedule and evaluate their newly developed shift schedule to improve their employees’ health, work–life balance, job satisfaction and general health. The shift schedule was thus changed from a 4-week rotation with 35–49 hours of work per week to an 8-week rhythm with 36–48 hours of work per week. The early duty week with six consecutive early mornings and one Sunday off was abolished. Previously alternating day, late and night shifts, with 12.25 hours day and night shifts in three subsequent weeks and days off (so-called ‘sleep-in days’) after night shifts following this early duty week were replaced by two night shifts followed by two or three days off each week, resulting in at least one day off after the ‘sleep-in day’. In contrast to the previous shift schedule, the new system also stipulated guaranteed days off without availability for special operations. A 12-hour day and night shifts now usually occurred twice a week, in some weeks only once. A comparison of both shift schedule models regarding occupational health recommendations is provided in online supplemental table S1.

bmjopen-2022-063302supp001.pdf (92.9KB, pdf)

Objectives and hypotheses

As described above, the current state of research provides evidence that shift work can lead to work–family conflicts and affect mental health and job satisfaction among police officers. However, there is considerably less longitudinal research data demonstrating the effects of shift work systems on work-related and health-related outcomes. As part of a broader evaluation of the potential effects of the new shift schedule on the working conditions at the metropolitan police, the aim of this study was to investigate within-subject and between-subject psychological effects of the new shift schedule. Further results of occupational health analyses50 as well as analyses of sickness absence rates51 are presented in separate articles. Within the evaluation process of the new shift schedule, we thus explored in this study: How does the newly introduced shift schedule impact police officers’ work–life balance, job satisfaction and quality of life? Is there a significant difference in work–life balance, job satisfaction and quality of life at the two time points before and after implementing the new shift schedule or regarding their gender?

Considering the state of research outlined above, we accordingly formulated the following hypotheses:

H1a: Police officers’ perceived work–life balance will be significantly higher 5.5 years after implementing the new shift schedule.

H1b: There will be no significant main effect of gender on police officers’ perceived work–life balance.

H1c: There will be no significant interaction effect of police officers’ gender and time on their perceived work–life balance.

H2a: Police officers’ job satisfaction will be significantly higher 5.5 years after implementing the new shift schedule.

H2b: There will be no significant main effect of gender on police officers’ job satisfaction.

H2c: There will be no significant interaction effect of police officers’ gender and time on their job satisfaction.

H3a: Police officers’ perceived quality of life will be significantly higher 5.5 years after implementing the new shift schedule.

H3b: There will be no significant main effect of gender on police officers’ perceived quality of life.

H3c: There will be no significant interaction effect of police officers’ gender and time on their perceived quality of life.

Methods

Study design, population and recruitment

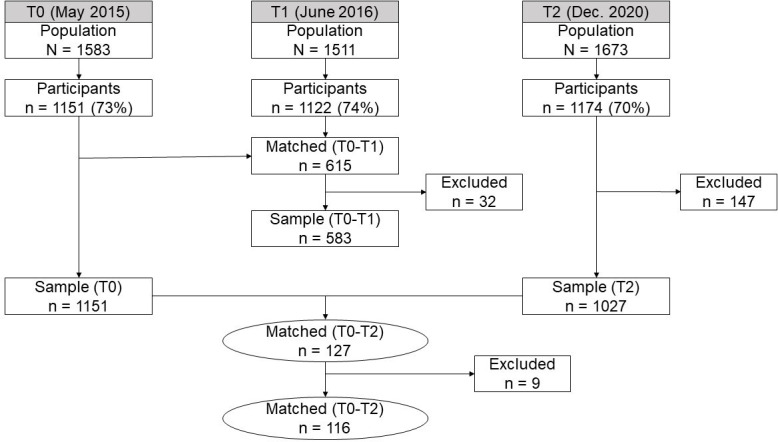

The newly proposed shift schedule was piloted in a German metropolitan police force in a successive roll-out across all police stations (PS). In May 2015, the first metropolitan PS introduced the new shift schedule, followed by six other PS until the end of 2015. Sixteen further PS and the operations centre introduced the new shift schedule until September 2017, one last PS changed their shift schedule in the beginning of 2021. Data were collected at three time points using questionnaires. Only police officers of four relevant duty groups who worked in the alternating shift schedule were included in the study. Participating police officers worked at PS across the metropolitan area or the operations centre where emergency calls are received and handled. The first survey took place shortly before the piloting of the new rotating shift schedule started in May 2015 (T0), the second survey was conducted 1 year later, in June 2016 (T1), followed by the third survey which was scheduled exactly 5 years later in May 2020 but had to be postponed to December 2020 and early January 2021 due to the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic (T2). Each time, standardised questionnaires with a covering letter were distributed via the official post boxes to all police officers of the metropolitan police force working rotating shifts and belonging to the predefined duty groups. Participants were asked to provide an individual matching code based on digits and letters. The completed questionnaires could be placed anonymously in sealed ballot boxes within 4 weeks. The paper questionnaires were then digitised with the data collection software TeleForm (Electric Paper Informationssysteme, Lüneburg, Germany). Despite the consistently high response rates, owing to lack of consent, many retirements, and new recruitments of police officers in the meantime, only 127 participants could be matched between T0 and T2. A further matching with T1-participants would have resulted in a sample size too small to analyse. Therefore, only police officers participating in the baseline (T0) and follow-up (T2) surveys were matched. A flow chart of this process is provided in figure 1.

Figure 1.

Participant flow chart across measurement points. Percentages in parentheses indicate response rates.

Measures

Sociodemographic and job characteristics

We gathered information on participants’ gender, age, rank within the police force, shift work experience, type of employment and duty service, relationship status and number of children as well as being a single parent or caring for relatives or others.

Work–life balance

Work–life balance was measured with five items which were already deployed and considered reliable (Cronbach’s α=0.92) in a similar survey of another German metropolitan police force.49 A sample item was ‘The coordination of my daily work routine with my private matters works well.’ All items were rated on a five-point Likert scale (1 = ‘I fully agree’ to 5 = ‘I do not agree’) and calculated as a score ranging from 0 (worst work–life balance) to 100 (best possible work–life balance).

Job satisfaction

We measured job satisfaction with seven items of the German version of the Copenhagen Psychosocial Questionnaire (COPSOQ) job satisfaction scale.52 The items were presented on a four-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 = ‘very satisfied’ to 4 = ‘very unhappy’. A sample item was ‘Regarding your work in general: How pleased are you with your job as a whole, everything taken into consideration?’ A score was computed based on the items, ranging from 0 (lowest job satisfaction) to 100 (highest job satisfaction). Both, the original and the latest COPSOQ study confirmed the German scale’s validity and reliability (Cronbach’s α ranging from 0.79 to 0.82).52 53

Quality of life

Quality of life was assessed using two items of the WHO’s questionnaire WHOQOL-Bref to calculate its global score ranging from 0 (worst quality of life) to 100 (best quality of life).54 Participants responded to the questions ‘Over the last 2 weeks, how would you rate your quality of life?’ and ‘Over the last 2 weeks, how satisfied were you with your health?’ on a scale from 1 = ‘very bad/unsatisfied’ to 5 = ‘very good/satisfied’. The instrument in its short version can be considered reliable (Cronbach’s α ranging from 0.57 to 0.88) and valid.54

Statistical analyses

After calculating the scores for work–life balance, job satisfaction and quality of life, the data were tested regarding the assumptions of a mixed analysis of variance (mixed ANOVA). After a check for missing values and multivariate outliers, 11 cases were excluded, resulting in a final sample size of N=116. Although most of the normality tests (Kolmogorov-Smirnov and Shapiro-Wilk) indicated no normality of the data, based on the sample size (N=116, n>30 for each group), normal Q-Q plots, skewness and kurtosis values (< 1.0), bivariate normal distribution of data could be assumed. The Pearson correlation matrix further indicated no multicollinearity (r<0.63). Box’s test indicated homogeneity of covariance matrices (p>0.05) and Levene’s tests indicated homoscedasticity (p>0.05) in all mixed ANOVA. Mauchly’s test for sphericity was non-significant due to the analysis of two time points. Cohen’s d was calculated from ηp2 and used to evaluate the effect sizes, considering d=0.20 as a small effect, d=0.50 as a medium effect, and d=0.80 as a large effect.55 In addition, mean scores and SD were calculated for each time point individually and a sensitivity analysis was conducted for the follow-up survey (T2) to account for the different lengths of time police officers had worked with the new shift schedule (in months) as a covariate. All statistical analyses were performed with IBM SPSS Statistics (V.25; IBM), p<0.05 was considered as significant.

Patient and public involvement

Patients or the public were not involved in the design, conduct, reporting or dissemination plans of our research.

Results

Participant characteristics

Most participants were male (70.7%). Most of the participating police officers were aged between 35 and 39 years (21.6%; also median and modal age category) and worked in upper police service (65.5%). Two-thirds of them had already worked in shift work for more than ten years (66.4%). Almost 90% worked full time and 68% had been predominantly on patrol duty in the past weeks before completing the survey. Participants also mostly lived in a permanent relationship (83.6%) and had at least one child (60.3%). Only less than 2% were single parents and slightly more (2.6%) cared for relatives or others alongside their job. Police officers’ sociodemographic characteristics at baseline (T0) are provided in more detail in table 1.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics of participants at baseline T0 (N=116)

| Characteristics | n | % |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 82 | 70.7 |

| Female | 34 | 29.3 |

| Age | ||

| 20–24 years | 4 | 3.4 |

| 25–29 years | 16 | 13.8 |

| 30–34 years | 19 | 16.4 |

| 35–39 years | 25 | 21.6 |

| 40–44 years | 15 | 12.9 |

| 45–49 years | 17 | 14.7 |

| 50–54 years | 19 | 16.4 |

| ≥55 years | 1 | 0.9 |

| Rank | ||

| Intermediate police service | 40 | 34.5 |

| Upper police service | 76 | 65.5 |

| Shift work experience | ||

| ≤5 years | 21 | 18.1 |

| 5–10 years | 18 | 15.5 |

| ≥10 years | 77 | 66.4 |

| Type of employment | ||

| Part-time | 12 | 10.3 |

| Fulltime | 104 | 89.7 |

| Type of duty service* | ||

| Exclusively office duty | 22 | 19.0 |

| Predominantly office duty | 8 | 6.9 |

| Office and patrol duty (50:50) | 7 | 6.0 |

| Predominantly patrol duty | 79 | 68.1 |

| Permanent relationship | ||

| Yes | 97 | 83.6 |

| No | 18 | 15.5 |

| No information given | 1 | 0.9 |

| Children | ||

| None | 46 | 39.7 |

| One child | 20 | 17.2 |

| Two children | 35 | 30.2 |

| Three children | 12 | 10.3 |

| Four children | 3 | 2.6 |

| Single parent | ||

| Yes | 2 | 1.7 |

| No | 100 | 86.2 |

| No information given | 14 | 12.1 |

| Caring for relatives/others | ||

| Yes | 3 | 2.6 |

| No | 113 | 97.4 |

| Time working with the new shift schedule | ||

| ≤24 months | 4 | 4.1 |

| 25–48 months | 31 | 26.7 |

| ≥49 months | 63 | 54.3 |

| No information | 18 | 15.5 |

*Refers to type of service exercised in the last 4 weeks prior to taking the survey.

Descriptive statistics at all three time points indicated increasing mean scores with each survey. Work–life balance, job satisfaction and quality of life have been rated higher consecutively at each time point. For work–life balance and job satisfaction, the difference of means was greater over the longer period between T1 and T2 compared with T0 and T1. For quality of life, by contrast, the difference was greater between T0 and T1, whereas between T1 and T2 only a smaller difference of the mean could be observed, as displayed in online supplemental table S2.

Within-subjects effects of time

The descriptive cross-sectional findings of each measurement point were also found in the matched sample of baseline and follow-up mean scores we used for the principal analyses. Means of all three dependent variables were higher at T2 than at T0 (see table 2). The mixed ANOVA revealed significant small and medium-sized main effects for the within-subjects effects on police officers’ work–life balance (F(1, 114) = 6.168, p=0.014, ηp² = 0.051, d=0.464) and job satisfaction (F(1, 114) = 9.921, p=0.002, ηp² = 0.080, d=0.590), thereby confirming hypotheses H1a and H2a. The main effect for quality of life was not significant (F(1, 114) = 0.593, p=0.443, ηp² = 0.005). Hypothesis H3a thus had to be rejected.

Table 2.

Means and SD for work–life balance, job satisfaction and quality of life (N=116)

| Work–life balance | Job satisfaction | Quality of life | ||||

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | |

| T0 | ||||||

| Males* | 50.305 | 21.305 | 66.148 | 11.538 | 62.805 | 17.675 |

| Females† | 57.794 | 22.670 | 65.314 | 10.308 | 65.809 | 19.294 |

| Total | 52.500 | 21.884 | 65.904 | 11.153 | 63.685 | 18.131 |

| T2 | ||||||

| Males* | 59.817 | 24.145 | 70.635 | 12.637 | 64.787 | 18.750 |

| Females† | 63.971 | 21.098 | 70.777 | 12.370 | 67.647 | 22.638 |

| Total | 61.034 | 23.280 | 70.677 | 12.506 | 65.625 | 19.910 |

*n=82

†n=34.

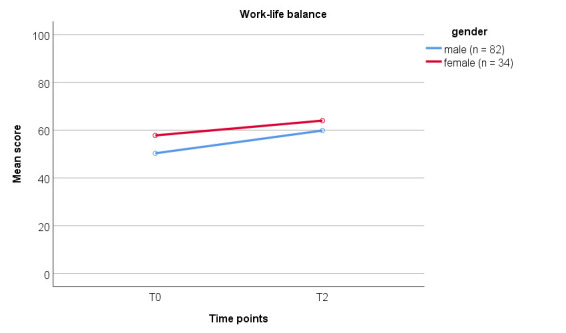

Between-subjects effects of gender and interactions

Regarding the between-subjects effects, the mixed ANOVA revealed no significant main effect of gender (F(1,114) = 3.046, p=0.084, ηp2 = 0.026) on perceived work–life balance. While female police officers’ mean rating increased by six points, their male colleagues’ mean rating increased by almost ten points from T0 to T2 (see table 2). The difference was not significant and both groups showed the same pattern. Therefore, no significant interaction between time and gender (F(1,114) = 0.279, p=0.598, ηp2 = 0.002) was found. Figure 2 illustrates that both, males and females showed a similarly sized increase for work–life balance across time. These findings support our hypotheses H1b-c.

Figure 2.

Profile plot of time and gender interaction for work–life balance (N=116).

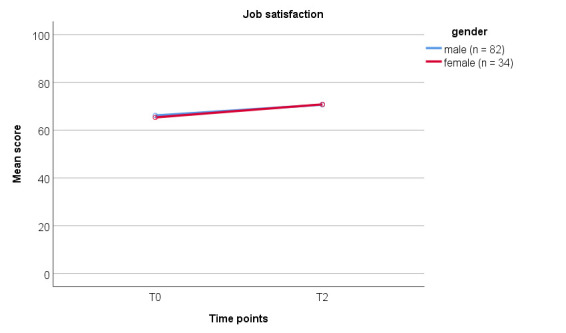

Likewise, no significant difference was found between male and female police officers with regard to their job satisfaction (F(1,114) = 0.035, p=0.851, ηp2 = 0.000), supporting hypothesis H2b. Female and male participants’ mean job satisfaction increased comparably from T0 to T2 (see table 2). However, women reported marginally higher values at T2 (+0.142 points compared with their male colleagues). Therefore, the profile plot in figure 3 depicts slightly crossing lines. Nevertheless, in support of hypothesis H2c, no significant interaction between time and gender (F(1,114) = 0.095, p=0.758, ηp2 = 0.001) was found for job satisfaction either.

Figure 3.

Profile plot of time and gender interaction for job satisfaction (N=116).

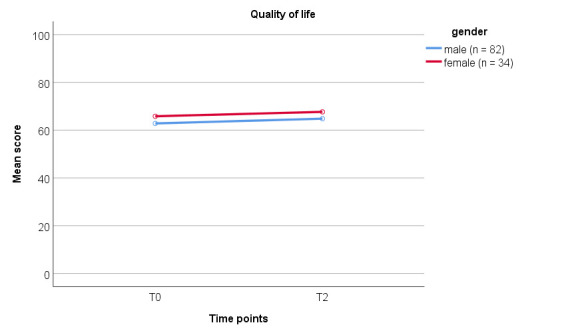

In line with hypothesis H3b, we found no significant differences in quality of life means between males and females (F(1,114) = 0.956, p=0.330, ηp2 = 0.008). Female police officers rated their quality of life higher than their male colleagues at both time points but both means increased at the same rate (see table 2). Therefore, no interaction between time and gender was found (F(1,114) =0.001, p=0.977, ηp2 = 0.000), as assumed in hypothesis H3c and depicted in figure 4.

Figure 4.

Profile plot of time and gender interaction for quality of life (N=116).

Sensitivity analyses with data from the follow up-survey (T2, n=893 for work–life balance, n=881 for job satisfaction and n=907 for quality of life) indicated that when controlling for the length of time police officers had worked according to the new shift schedule, between-subject differences did not change and remained insignificant regardless of whether the exposure duration was added to the model or not.

Discussion

In this study, we analysed within-subject and between-subject differences of three work-related mental health outcomes among police officers of a German metropolitan police department at two time points. The baseline data were compared with the survey results 5.5 years later, after implementing a new shift schedule which was supposed to improve mental and physical health of the police officers. Our findings provide support for most of our hypotheses: work–life balance and job satisfaction scores significantly increased between the baseline survey and the follow-up. Quality of life increased as well, but not to a statistically significant extent. At both time points, female police officers reported higher levels of work–life balance and quality of life, whereas male participants rated their job satisfaction higher at the baseline. However, no significant differences were found between male and female police officers regarding their work–life balance, job satisfaction and quality of life. Notably, the greatest increase over the 5.5 years could be observed in the work–life balance of police officers, followed by job satisfaction and quality of life.

Consistent with previous findings, restricted work–life balance due to the shift schedule affected male and female police officers equally.37–39 Sociodemographic characteristics revealed that most of the participants had children and lived in a permanent relationship, whereas only very few participants were single parents. This may indicate that parents shared their care for children or other relatives and that traditional gender roles are being undone.37 However, work–life balance does not only include balancing work and family matters but also social life and leisure activities. Our results are further supported by findings of a another German metropolitan police force that evaluated similar shift schedules which served as a blueprint for the one we evaluated.48 49 Accordingly, shift schedules with more flexible working time arrangements reduced the impact of work–life balance as a potential stressor and that work–life balance was negatively related to police officers’ perceived strain.48

At both time points, job satisfaction means exceeded those reported by the international and German general working population,53 56 indicating a high job satisfaction among our participants overall. In line with our results, recent findings suggest that changing the shift schedule could have a positive influence on police officers’ job satisfaction.57 In partial contradiction with our findings, male police officers reported lower job satisfaction compared with female colleagues in a Greek sample, while female police officers reported lower values of health-related quality of life compared with their male colleagues.44 However, the slightly greater increase of job satisfaction ratings among female participants in our sample could indicate a gradually closing gender gap with the new shift schedule in this regard. Yet the results need to be interpreted very cautiously and need to be further evaluated in the long-term, as the differences were small and not significant.

Compared with norm values, quality of life was rated lower in our sample at both time points.54 A cross-sectional study among criminal police officers also revealed lower health-related quality of life scores compared with results from general populations.46 Nevertheless, it becomes apparent that the quality of life marginally increased after implementing the new shift schedule, although to a non-significant and lesser extent than work–life balance and job satisfaction. Further analyses indicated that the working conditions of the new shift schedule, especially the increased number of 12-hour shifts, did not have a detrimental impact on the police officers’ quality of life.50 Why the scores for work–life balance and job satisfaction but not for quality of life between males and females seem to align over time thus remains unclear. As research on police officers’ quality of life has been unfolding recently, future research will hopefully provide more insights on such differences and further associations.

Limitations

Based on longitudinal data, we were able to examine changes in health-related outcomes among shift-working police officers before and after implementing a new shift schedule and thus contributed to a deeper understanding of these outcomes associated with working conditions in shift schedules. However, some limitations need to be discussed. Although we were able to gather and analyse data over three different time points, we could only evaluate the baseline and follow-up data in a longitudinal design. Despite high response rates, lack of given consent to evaluate the data, retirements and new recruits led to an insufficient sample size after matching participants across all three time points. Since the piloting was carried out as a successive rollout, not all of the PS surveyed had introduced the new shift schedule or had sufficient experience with the new shift schedule after 1 year (T1). We, therefore, dropped the data of the second evaluation for longitudinal analyses to present longer-term rather than short-term effects. Information on short-term changes 1 year after the baseline (ie, piloting of the new shift schedule) are therefore not included in the present analyses. Due to the small sample size, we did not include the exposure duration of the new shift schedule as a covariate into the primary analysis. However, sensitivity analyses conducted on the larger data set of the cross-sectional data from the follow-up survey (T2) showed that the effects did not change when the covariate was added to the model. Neither did age have a significant effect, according to further analyses. Although we were able to analyse a larger sample size by considering the baseline and follow-up only, the matched sample differs from the population of shift-working police officers at T2 in age and gender and is therefore not representative of the current metropolitan police force which is now younger and includes more female police officers,50 again due to retirements and new recruitments. The results from this sample might also not necessarily valid for other police forces. Moreover, the analysed data stem from self-reports of the participants and are thus susceptible to bias such as socially desirable answers. Motivational efforts may also have had an effect on the participants’ responses, as the results of the evaluation served as a decision-making basis on the continuation of the piloted shift schedule. Furthermore, selection effects such as the healthy worker effect may influence the results. Answers from colleagues who were under a lot of strain, ill or not able to work, who retired early or changed their profession may have not been reflected in the results which may therefore appear more positive than they would be based on the whole relevant police work force. Lastly, merely effects up to 5.5 years after implementing the new shift schedule became evident in this study. Longer-term effects will have to be further evaluated in the future to be able to assess the new shift schedule in this respect.

Implications for research and practice

Our results provide evidence that changing a shift schedule according to occupational health recommendations improved police officers work–life balance and job satisfaction. Nevertheless, it must be taken into account that according to German labour legislation the implementation of 12-hour duties, which is implemented based on European law, requires special permissions and should be strictly limited to the minimum necessary to cover the service. Working in shifts or at nonstandard hours interferes with leisure time and can thus restrict social life or even parenting functioning resources.14 58 The costs and benefits of longer duties and consecutive off-duty periods therefore must be weighed carefully. For a better work–life balance and prevention of detrimental health effects, shifts should be variable and predictable.14 48 59 This was implemented with the new shift schedule and acknowledged in additional free text answers participants gave in the follow-up survey. To better balance police work with care work that occurs in specific stages of life, such as raising children or caring for relatives, more flexible working time models could be supportive. In relation to the entire working life, working time could be reduced in such phases, therefore enabling a better balance of private and professional life.48 After successfully implementing the new shift schedule, further health-promoting measures should be offered to police officers. Research findings suggest that educational-based family-friendly programmes should be established in PS.60 Moreover, several health promotion programmes for police forces have been evaluated recently.61–63 At least in online trainings, it seems to be harder to change mental health and attitudes toward suicide compared with knowledge and competence, as an intervention study among German-speaking police officers implies.64 In this vein, mindfulness-based health promotion was recently shown to be feasible and efficacious to improve quality of life among Brazilian officers.61 It is also recommended to identify police officers’ risk factors for mental health early to be able to prevent and promote their quality of life.65 Job control and a flexibility-oriented culture can positively influence job satisfaction.66 Continuous participation of police officers should be maintained to shape and continuously adapt the change process of implementing the new shift schedule.48 Regularly conducted risk assessments can provide a basis for this and identify such stressors to counteract them preventively.

Conclusion

The results of this longitudinal study demonstrated small positive changes 5.5 years after adapting a German metropolitan police force’s alternating shift schedule. The new shift schedule providing more 12-hour shifts as well as more off-duty days enabled police officers to better balance private and work-related demands regardless of their gender. The altered working conditions were also reflected in higher job satisfaction, whereas the increase in quality of life was not significant. Despite the benefits of more predictable scheduling and free time in the new shift schedule, more frequent 12-hour shifts during the day and night may entail adverse health effects in the long run. Therefore, larger cohort studies and evaluations over a longer period with several measurement points are recommended to verify the effects and continuously monitor its consequences for police officers.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all police officers who supported the evaluation process and those who participated in the surveys. Furthermore, we would like to acknowledge Niklas Kiepe, Lea Rischke and Joelle-Cathrin Flöther for their support in digitising the data.

Footnotes

Contributors: ER drafted the manuscript and conducted data analyses. ER, MVG and RH prepared the data for analyses. ER, MVG, RH, AMP, CT, VH and SM participated in designing the study. MVG, RH, AMP, CT, VH and SM supervised the study and data analyses. MVG administered the project. MVG, RH, AMP, CT, VH and SM contributed in the drafting of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. ER acts as guarantor for the paper.

Funding: This work was supported by Polizei Hamburg (grant number: N/A).

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Author note: We respectfully dedicate this paper to the memory of our colleague Cordula Bittner (1968-2019), who leaded the first part of the evaluation (2015-2016) ensuring a fruitful dialogue between researchers and police, which laid the foundation for the further evaluation 2021.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

No data are available. The data cannot be made available due to the contractual provision with the cooperation partner.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

This study involves human participants and was approved by Ethics Review Committee of the Hamburg Medical Association, Germany (PV4999 / WF-009/20). Participants gave informed consent to participate in the study before taking part.

References

- 1.Gu F, Han J, Laden F, et al. Total and cause-specific mortality of U.S. nurses working rotating night shifts. Am J Prev Med 2015;48:241–52. 10.1016/j.amepre.2014.10.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vetter C, Devore EE, Wegrzyn LR, et al. Association between rotating night shift work and risk of coronary heart disease among women. JAMA 2016;315:1726–34. 10.1001/jama.2016.4454 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vyas MV, Garg AX, Iansavichus AV, et al. Shift work and vascular events: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 2012;345:e4800. 10.1136/bmj.e4800 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ijaz S, Verbeek J, Seidler A, et al. Night-shift work and breast cancer--a systematic review and meta-analysis. Scand J Work Environ Health 2013;39:431–47. 10.5271/sjweh.3371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jia Y, Lu Y, Wu K, et al. Does night work increase the risk of breast cancer? A systematic review and meta-analysis of epidemiological studies. Cancer Epidemiol 2013;37:197–206. 10.1016/j.canep.2013.01.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rao D, Yu H, Bai Y, et al. Does night-shift work increase the risk of prostate cancer? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Onco Targets Ther 2015;8:2817–26. 10.2147/OTT.S89769 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang X, Ji A, Zhu Y, et al. A meta-analysis including dose-response relationship between night shift work and the risk of colorectal cancer. Oncotarget 2015;6:25046–60. 10.18632/oncotarget.4502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sallinen M, Kecklund G. Shift work, sleep, and sleepiness - differences between shift schedules and systems. Scand J Work Environ Health 2010;36:121–33. 10.5271/sjweh.2900 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brown JP, Martin D, Nagaria Z, et al. Mental health consequences of shift work: an updated review. Curr Psychiatry Rep 2020;22:7. 10.1007/s11920-020-1131-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Folkard S. Effects on performance efficiency. In: Colquhoun WP, Costa G, Folkard S, eds. Shiftwork problems and solutions. Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang, 1996: 65–87. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Monk TH, Folkard S, Wedderburn AI. Maintaining safety and high performance on shiftwork. Appl Ergon 1996;27:17–23. 10.1016/0003-6870(95)00048-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wüthrich P. Studie über die gesundheitlichen, sozialen und psychischen Auswirkungen der Nacht- und Schichtarbeit [Study on the health, social and psychological effects of night and shift work]. Bern: Schweizerischer Gewerkschaftsbund; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Deutsche Gesellschaft für Arbeitsmedizin und Umweltmedizin . Nacht- und Schichtarbeit. S1-Leitlinie der Deutschen Gesellschaft für Arbeitsmedizin und Umweltmedizin [Night work and shift work. S1 Guideline of the German Society for Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wöhrmann AM, Müller G, Ewert K. Shift work and work-family conflict: a systematic review. Sozialpolitik.ch 2020;2020:1–26. 10.18753/2297-8224-165 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Faragher EB, Cass M, Cooper CL. The Relationship between Job Satisfaction and Health: A Meta-Analysis. In: Cooper CL, ed. From stress to wellbeing volume 1: the theory and research on occupational stress and wellbeing. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK, 2013: 254–71. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Garbarino S, Guglielmi O, Puntoni M, et al. Sleep quality among police officers: implications and insights from a systematic review and meta-analysis of the literature. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2019;16:885. 10.3390/ijerph16050885 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Garbarino S, De Carli F, Nobili L, et al. Sleepiness and sleep disorders in shift workers: a study on a group of Italian police officers. Sleep 2002;25:648–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Garbarino S, Cuomo G, Chiorri C, et al. Association of work-related stress with mental health problems in a special police force unit. BMJ Open 2013;3:e002791. 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-002791 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Violanti JM, Fekedulegn D, Hartley TA, et al. Highly rated and most frequent stressors among police officers: gender differences. Am J Crim Justice 2016;41:645–62. 10.1007/s12103-016-9342-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Violanti JM, Charles LE, McCanlies E, et al. Police stressors and health: a state-of-the-art review. Policing 2017;40:642–56. 10.1108/PIJPSM-06-2016-0097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Violanti JM, Charles LE, Hartley TA, et al. Shift-work and suicide ideation among police officers. Am J Ind Med 2008;51:758–68. 10.1002/ajim.20629 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Violanti JM. Predictors of police suicide ideation. Suicide Life Threat Behav 2004;34:277–83. 10.1521/suli.34.3.277.42775 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hem E, Berg AM, Ekeberg AO. Suicide in police--a critical review. Suicide Life Threat Behav 2001;31:224–33. 10.1521/suli.31.2.224.21513 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Violanti JM, Vena JE, Marshall JR. Suicides, homicides, and accidental death: a comparative risk assessment of police officers and municipal workers. Am J Ind Med 1996;30:99–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Peterson SA, Wolkow AP, Lockley SW, et al. Associations between shift work characteristics, shift work schedules, sleep and burnout in North American police officers: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 2019;9:e030302. 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-030302 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fekedulegn D, Burchfiel CM, Hartley TA, et al. Shiftwork and sickness absence among police officers: the BCOPS study. Chronobiol Int 2013;30:930–41. 10.3109/07420528.2013.790043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mikkelsen A, Burke RJ. Work-family concerns of Norwegian police officers: antecedents and consequences. Int J Stress Manag 2004;11:429–44. 10.1037/1072-5245.11.4.429 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sadiq M. Policing in pandemic: is perception of workload causing work-family conflict, job dissatisfaction and job stress? J Public Aff 2022;22:e2486. 10.1002/pa.2486 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Islam T, Khan MM, Ahmed I, et al. Work-family conflict and job dissatisfaction among police officers: mediation of threat to family role and moderation of role segmentation enhancement. Policing 2020;43:403–15. 10.1108/PIJPSM-06-2019-0087 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rathi N, Barath M. Work‐family conflict and job and family satisfaction. Equal Divers Incl 2013;32:438–54. 10.1108/EDI-10-2012-0092 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Frank J, Lambert EG, Qureshi H. Problems spilling over: work–family conflict’s and other stressor variables’ relationships with job involvement and satisfaction among police officers. J Polic Intell Count Terror 2021:1–24. 10.1080/18335330.2021.1946711 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gary Howard W, Howard Donofrio H, Boles JS. Inter‐domain work‐family, family‐work conflict and police work satisfaction. Policing 2004;27:380–95. 10.1108/13639510410553121 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Griffin JD, Sun IY. Do work-family conflict and resiliency mediate police stress and burnout: a study of state police officers. Am J Crim Just 2018;43:354–70. 10.1007/s12103-017-9401-y [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lambert EG, Qureshi H, Keena LD, et al. Exploring the link between work-family conflict and job burnout among Indian police officers. The Police Journal 2019;92:35–55. 10.1177/0032258X18761285 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bazana S, Dodd N. Conscientiousness, work family conflict and stress amongst police officers in Alice, South Africa. J Psychol 2013;4:1–8. 10.1080/09764224.2013.11885487 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kurtz DL. Roll call and the second shift: the influences of gender and family on police stress. Police Pract Res 2012;13:71–86. 10.1080/15614263.2011.596714 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Duxbury L, Bardoel A, Halinski M. ‘Bringing the Badge home’: exploring the relationship between role overload, work-family conflict, and stress in police officers. Policing and Society 2021;31:997–1016. 10.1080/10439463.2020.1822837 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.He N, Zhao J, Archbold CA. Gender and police stress. Policing 2002;25:687–708. 10.1108/13639510210450631 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Janzen BL, Muhajarine N, Kelly IW. Work-family conflict, and psychological distress in men and women among Canadian police officers. Psychol Rep 2007;100:556–62. 10.2466/pr0.100.2.556-562 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dantzker ML, Kubin B. Job satisfaction: the gender perspective among police officers. AJCJ 1998;23:19–31. 10.1007/BF02887282 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Miller HA, Mire S, Kim B. Predictors of job satisfaction among police officers: does personality matter? J Crim Justice 2009;37:419–26. 10.1016/j.jcrimjus.2009.07.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Johnson RR. Police officer job satisfaction: a multidimensional analysis. Police Q 2012;15:157–76. 10.1177/1098611112442809 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lu L, Liu L, Sui G, et al. The associations of job stress and organizational identification with job satisfaction among Chinese police officers: the mediating role of psychological capital. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2015;12:15088–99. 10.3390/ijerph121214973 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Alexopoulos EC, Palatsidi V, Tigani X, et al. Exploring stress levels, job satisfaction, and quality of life in a sample of police officers in Greece. Saf Health Work 2014;5:210–5. 10.1016/j.shaw.2014.07.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Arroyo TR, Borges MA, Lourenção LG. Health and quality of life of military police officers. Brazilian J Health Promot 2019;32:1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wu X, Liu Q, Li Q, et al. Health-related quality of life and its determinants among criminal police officers. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2019;16:1398. 10.3390/ijerph16081398 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Morales-Manrique CC, Valderrama-Zurián JC. Quality of life in police officers: what is known and proposals. Pap Psicol 2012;33:60–7. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Härtwig C, Sporbert A. Evaluation der Einführung verschiedener Arbeitszeitmodelle. Befunde einer quasi-experimentellen Längsschnittstudie bei der Polizei [Evaluation of the introduction of different working time models: Findings of a quasiexperimental longitudinal study at the police]. Z Arbeitswiss 2013;67:243–51. 10.1007/BF03374413 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hoff E-H, Härtwig C, Sporbert A. Wissenschaftliche Begleitung und Evaluation zur Einfuhrung neuer Arbeitszeitmodelle bei der Polizei Berlin. Abschlussbericht 31. Juli 2012 [Scientific monitoring and evaluation of the introduction of new working time models at the Berlin Police. Final report 31 July 2012]. Berlin: Freie Universität Berlin; 2012. https://www.parlament-berlin.de/ados/17/InnSichO/protokoll/iso17-035-ip-Anlage.pdf [Accessed 08 Feb 2022]. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Velasco-Garrido M, Herold R, Rohwer E, et al. Evolution of work ability, quality of life and self-rated health in a police department after remodelling shift schedule. BMC Public Health 2022;22:1670. 10.1186/s12889-022-14098-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Herold R, Velasco Garrido M, Rohwer E. In preparation 2022.

- 52.Nübling M, Stößel U, Hasselhorn HM. Methoden zur Erfassung psychischer Belastung – Erprobung eines Messinstrumentes (COPSOQ) [Methods for assessing mental stress - testing a measurement instrument (COPSOQ)]. Dortmund/Berlin/Dresden: Bundesanstalt für Arbeitsschutz und Arbeitsmedizin; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lincke H-J, Vomstein M, Lindner A, et al. COPSOQ III in Germany: validation of a standard instrument to measure psychosocial factors at work. J Occup Med Toxicol 2021;16:50. 10.1186/s12995-021-00331-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Angermeyer M, Kilian R, Matschinger H. WHOQOL-100 und WHOQOL-BREF. Handbuch für die deutschsprachigen Versionen der WHO Instrumente zur Erfassung von Lebensqualität [WHOQOL-100 and WHOQOL-BREF Manual for the German-language versions of the WHO quality of life instruments. Göttingen: Hogrefe, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2nd ed. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Burr H, Berthelsen H, Moncada S, et al. The third version of the Copenhagen psychosocial questionnaire. Saf Health Work 2019;10:482–503. 10.1016/j.shaw.2019.10.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Paoline EA, Gau JM. An empirical assessment of the sources of police job satisfaction. Police Q 2020;23:55–81. 10.1177/1098611119875117 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zhao Y, Cooklin A, Butterworth P, et al. How does working nonstandard hours impact psychological resources important for parental functioning? Evidence from an Australian longitudinal cohort study. SSM Popul Health 2021;16:100931. 10.1016/j.ssmph.2021.100931 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Scholarios D, Hesselgreaves H, Pratt R. Unpredictable working time, well-being and health in the police service. Int J Hum Resour Manag 2017;28:2275–98. 10.1080/09585192.2017.1314314 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Youngcourt SS, Huffman AH. Family-friendly policies in the police: implications for work-family conflict. Appl Psychol Crim Justice 2005;1:138–62. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Trombka M, Demarzo M, Campos D, et al. Mindfulness training improves quality of life and reduces depression and anxiety symptoms among police officers: results from the police study—a multicenter randomized controlled trial. Front Psychiatry 2021;12. 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.624876 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Liakopoulou D, Tigani X, Varvogli L, et al. Stress management and health promotion intervention program for police forces. Int J Police Sci Manag 2020;22:148–58. 10.1177/1461355719898202 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Márquez MA, Galiana L, Oliver A, et al. The impact of a mindfulness-based intervention on the quality of life of Spanish national police officers. Health Soc Care Community 2021;29:1491–501. 10.1111/hsc.13209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hofmann L, Glaesmer H, Przyrembel M, et al. An evaluation of a suicide prevention e-learning program for police officers (COPS): improvement in knowledge and competence. Front Psychiatry 2021;12:770277. 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.770277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Galanis P, Fragkou D, Katsoulas TA. Risk factors for stress among police officers: a systematic literature review. Work 2021;68:1255–72. 10.3233/WOR-213455 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Marcos A, García-Ael C, Topa G. The influence of work resources, demands, and organizational culture on job satisfaction, organizational commitment, and citizenship behaviors of Spanish police officers. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020;17:7607. 10.3390/ijerph17207607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2022-063302supp001.pdf (92.9KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

No data are available. The data cannot be made available due to the contractual provision with the cooperation partner.