Abstract

The essential oils (EOs) of Duguetia echinophora, D. riparia, Xylopia emarginata and X. frutescens (Annonaceae) were obtained by hydrodistillation and the chemical composition was analyzed by GC-MS. An antioxidant assay using the ABTS and DPPH radicals scavenging method and cytotoxic assays against Artemia salina were also performed. We evaluated the interaction of the major compounds of the most toxic EO (X. emarginata) with the binding pocket of the enzyme Acetylcholinesterase, a molecular target related to toxicity in models of Artemia salina. The chemical composition of the EO of D. echinophora was characterized by β-phellandrene (39.12%), sabinene (17.08%) and terpinolene (11.17%). Spathulenol (22.22%), caryophyllene oxide (12.21%), humulene epoxide II (11.86%) and allo-aromadendrene epoxide (10.20%) were the major constituents of the EO from D. riparia. Spathulenol (5.65%) and caryophyllene oxide (5.63%) were the major compounds of the EO from X. emarginata. The EO of X. frutescens was characterized by α-pinene (20.84%) and byciclogermacrene (7.85%). The results of the radical scavenger DPPH assays ranged from 15.87 to 69.38% and the highest percentage of inhibition was observed for the EO of X. emarginata, while for ABTS radical scavenging, the antioxidant capacity of EOs varied from 14.61 to 63.67%, and the highest percentage of inhibition was observed for the EO of X. frutescens. The EOs obtained from D. echinophora, X. emarginata and X. frutescens showed high toxicity, while the EO of D. riparia was non-toxic. Because the EO of X. emarginata is the most toxic, we evaluated how its major constituents were able to interact with the Acetylcholinesterase enzyme. The docking results show that the compounds are able to bind to the binding pocket through non-covalent interactions with the residues of the binding pocket. The species X. emarginata and X. frutescens are the most promising sources of antioxidant compounds; in addition, the results obtained for preliminary cytotoxicity of the EOs of these species may also indicate a potential biological activity.

Keywords: natural products, Amazon, medicinal plant, volatile compounds, bioactive compounds

1. Introduction

Essential oils (EOs) are complex mixtures of substances formed in the secondary metabolism of plants [1,2], and the substances present in EOs are intended to protect plants against pests, herbivores, fungi and bacteria [3]. Among these substances, sesquiterpenes, monoterpenes, aldehydes, alcohols, esters, and ketones stand out [4,5,6,7,8]. In aromatic species belonging to the Annonaceae family, compounds belonging to the class of mono and sesquiterpenoids have been identified as predominant [9,10]. Due to the strong demand for pure natural ingredients in various fields, EOs have been widely used all over the world for various applications in industrials sectors, such as food, pharmaceuticals and cosmetics production [11].

The antioxidant activity of EOs is a property of great interest because the EOs may preserve foods, cosmetics, perfumes and other products from the toxic effects of oxidants. Moreover, the ability of EOs to scavenge free radicals may play an important role in prevention of some diseases such as brain dysfunction, cancer, heart disease and immune system decline. Increasing evidence has suggested that these diseases may result from cellular damage caused by free radicals [12,13,14]. Furthermore, the Artemia salina Leach assay is a preliminary toxicity test that screens a large number of biosynthesized compounds from plant secondary metabolism and can quickly indicate the potential biological activity of EOs [15]. In general, authors report that the molecular target in toxicity tests with A. salina is acetylcholinesterase, so it is important to investigate the interaction mechanisms using in silico studies [16,17].

Annonaceae has numerous species that produce EOs. This family consists of 2106 species and more than 130 genera concentrated in the tropics. Around 900 species are neotropical, 450 are Afrotropical and the other species are Indomalayan [18]. In the Amazon region it is estimated that there are approximately 268 species [19]. The biological activities described for the EOs of these species include antioxidant [20,21,22] and cytotoxic activities [23]. Considering the large number of species of Annonaceae occurring in the Amazon region, there are still few studies investigating the chemical composition and the biological activities of the EOs of these species. In this paper, the chemical composition and the antioxidant and cytotoxic properties of the EOs obtained from the Annonaceae species collected in the State of Pará-Brazil (Duguetia echinophora R.E.Fr., D. riparia Huber, Xylopia emarginata Mart. and X. frutescens Aubl) were evaluated. We also studied the interaction of the major compounds of the most toxic EO with the binding pocket of the enzyme Acetylcholinesterase.

It is worth mentioning that there is still no literature available on the biological properties of the EOs from D. echinophora, D. riparia or X. emarginata nor on the chemical composition of the EO of the species D. echinophora. The chemical composition of EOs from D. riparia, X. emarginata and X. frutescens has been evaluated and is characterized by mono and sesquiterpenes [24,25,26]. The EO from X. frutescens showed interesting anticancer [26] and repellent activities [27]. In folk medicine, this species is known in Brazil as “embira”, “semente-de-embira”, ‘‘embira-vermelha’’ and ‘‘pau carne”, and is widely used to treat flu, digestive problems, rheumatism, halitosis, tooth decay and as a bladder stimulant [26,28,29].

The present work provides new information related to the antioxidant potential of EOs from the species D. echinophora, D. riparia, X. emarginata and X. frutescens for use in areas such as food conservation. In addition, we investigate preliminary toxicity that provides important information related to the application of these EOs in potential biological activities.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Botanical Material

The leaves of Annonaceae species were collected in the municipality of Magalhães Barata (State of Pará, Amazon region, Brazil) in March 2018 (00°47′51.6″ S; 047°33′38.4″ samples were identified by Jorge Oliveira, a parataxonomist from the Museu Paraense Emílio Goeldi (MPEG), Belém, Pará, Brazil. The voucher specimens were deposited at the Herbarium of MPEG under the registration codes MG-237446 for D. riparia, MG-237477 for D. echinophora, MG-237444 for X. frutescens and MG-237449 for X. emarginata.

2.2. Preparation of Botanical Material and Extraction of Essential Oils

The leaves of Annonaceae species were dried in an air-circulation oven for five days at 35 °C and then crushed in a knife mill (Tecnal, model TE-631/3, Piracicaba, São Paulo, Brazil). The moisture content was analyzed using a moisture analyzer (Marte, model ID50, São Paulo, Brazil). The EOs were extracted from the leaves of Annonaceae species by hydrodistillation in a glass modified Clevenger-type apparatus [30,31], using 150 g of plant material for each experiment. Hydrodistillations were carried out for 3 h at 100 °C. The obtained EOs were dried over anhydrous sodium sulfate and stored in a freezer at −10 °C. The yields of EOs (%) were calculated based on plant dry weight and expressed in mL/100 g of dried material.

2.3. Analysis of Chemical Profile of Essential Oil

The phytochemical profiles of the EOs were analyzed using chromatography/mass spectrometry (GC/MS) using a Shimadzu QP Plus 2010 GC-MS (Kyoto, Japan) following protocols reported earlier by our research group [32,33]. The retention index was calculated for all volatile constituents using a homologous series of n-alkanes (C8-C40, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) according Van den Dool and Kratz [34], and the compounds were identified by comparing their mass spectrum and retention index with the data from the libraries [35].

2.4. ABTS•+ Radical Scavenging Assay

The ABTS•+ assay was performed according to the methodology adapted from Miller et al. [36], and modified by Re et al. [37]. ABTS•+ was prepared using 7 mM ABTS•+ and 140 mM of potassium persulfate incubated at room temperature without light for 16 h. The solution was then diluted with phosphate-buffered saline until it reached an absorbance of 0.700 ± 0.02 at 734 nm. To measure the antioxidant capacity, 2.97 mL of the ABTS•+ solution was transferred to the cuvette, and the absorbance at 734 nm was determined using a Biospectro SP 22 spectrophotometer. Then, 0.03 mL of the sample was added to the cuvette containing the ABTS•+ radical, and after 5 min, the second reading was performed. The data were expressed as percent inhibition.

2.5. DPPH• Radical Scavenging Assay

The test was carried out according to the method proposed by Blois et al. [38]. To measure the antioxidant capacity, initially, the absorbance of DPPH• 0.1 mM diluted in ethanol was determined. Subsequently, 0.6 mL of DPPH• solution, 0.35 mL of distilled water, and 0.05 mL of the sample were mixed and placed in a water bath at 37 °C for 30 min. Thereafter, the absorbances were determined in a spectrophotometer at 517 nm. The data were expressed as percent inhibition.

2.6. Preliminary Toxicity

The toxicity of the essential oils was tested against larvae of the microcrustacean Artemia salina leach (brine shrimp). The eggs of A. salina (25 mg) were incubated at room temperature (27–30 °C) in an aquarium with artificial salt water composed of a mixture of 46 g of NaCl, 22 g of MgCl2.6H2O, 8 g of Na2SO4, 2.6 g of CaCl2.6H2O, and 1.4 g of KCl in 2.0 L of distilled water. The pH was adjusted to the 8.0–9.0 range using Na2CO3 to avoid the risk of larvae death by lowering the pH during incubation. After 24 h of egg hatching, oil solutions were prepared at concentrations of 100, 50, 25, 10, 5 and 1 µg·mL−1 using brine as vehicle and 5% dimethyl sulfoxide as diluent. Ten larvae of A. salina were placed in each tube containing the solution, and the mortality rate of the larvae after 24 h was calculated. The mean lethal concentration (LC50) was estimated using the Probitos statistical method. All the experiments were performed in triplicate using same protocols as described by Rebelo et al. [39].

2.7. In silico analysis

To carry out the in silico study, the molecules spathulenol and caryophyllene oxide (the major constituents present in the EO of Xylopia emarginata) were constructed using GaussView 5.5 software [40,41]. Their molecular structures were optimized with B3LYP/6-31G* [42,43] with Gaussian 09 [44]. We used the molecular method to evaluate the compounds interaction mode with Acetylcholinesterase (AChE). For this we used the Molegro Virtual Docker (MVD) 5.5 [45,46,47], and the crystal structure used as a molecular target can be found in the Protein Data Bank using the ID: 4M0E [48]. The MolDock Score (GRID) scoring function was used with a Grid resolution of 0.30 Å and 5 Å radius encompassing the entire connection cavity. The MolDock SE algorithm was used with the following parameter settings: number of runs equal to 10, maximum of 1500 interactions, and maximum population size equal to 50. The maximum evaluation of 300 steps with a neighbor distance factor equal to 1 and energy threshold equal to 100 was used during the molecular docking simulation.

2.8. Multivariate Analysis

The multivariate analysis was performed using the Minitab 17® software (free version number 17, Minitab Inc., State College, PA, USA). The chemical constituents of the EOs from the leaves of D. echinophora, D. riparia, X. emarginata and X. frutescens, (≥3%), were set as the experimental variables, thus forming a matrix of 4 (samples) × 23 (variables) according to the literature [15,32,33].

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Chemical Composition

The EOs yields from the leaves of the Annonaceae species were 1.76, 0.08, 0.27 and 1.50% for D. echinophora, D. riparia, X. emarginata and X. frutescens, respectively. The yield found in this study for the EO of D. riparia was close to those found in studies with other species of the Duguetia genus (0.1–0.6%) [24]. The EOs yields found for the Xylopia species were also very close to those found in others studies [25,26]. The yields and EOs compositions of the species are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Yield and chemical compositions of the Annonaceae species essential oils.

| DE | DR | XE | XF | ||||

| Essential Oil Yield (%) | 1.76 | 0.08 | 0.27 | 1.50 | |||

| RT | RI L | RIC | Constituents (%) | ||||

| 5.19 | 801 | 798 | Hexanal | 0.95 | |||

| 6.95 | 844 | 845 | Hex-(3E)-enol | 1.35 | |||

| 7.25 | 863 | 857 | Hexanol | 0.85 | |||

| 8.30 | 924 | 925 | α-Thujene | 4.89 | |||

| 11.17 | 932 | 932 | α-Pinene | 4.14 | 1.31 | 3.14 | 20.84 |

| 11.23 | 946 | 948 | Camphene | 2.72 | |||

| 11.98 | 969 | 974 | Sabinene | 17.08 | |||

| 12.32 | 974 | 974 | β-Pinene | 2.01 | 25.95 | ||

| 12.57 | 988 | 991 | Myrcene | 3.61 | |||

| 13.09 | 1002 | 1002 | α-Phellandrene | 1.27 | 1.73 | ||

| 13.56 | 1008 | 1011 | δ-3-Carene | 0.95 | |||

| 13.89 | 1014 | 1016 | α-Terpinene | 0.85 | |||

| 14.02 | 1020 | 1022 | p-Cymene | 0.65 | 0.54 | 0.44 | |

| 14.32 | 1024 | 1027 | Limonene | 3.00 | |||

| 14.79 | 1025 | 1029 | β-Phellandrene | 39.12 | 2.60 | ||

| 14.90 | 1026 | 1031 | 1,8-Cineole | 3.36 | 1.00 | ||

| 14.99 | 1032 | 1043 | (Z)-β-Ocimene | 0.44 | |||

| 15.02 | 1054 | 1055 | γ-Terpinene | 1.00 | 1.40 | ||

| 15.13 | 1065 | 1068 | cis-Hydrate sabinene | 0.17 | |||

| 15.74 | 1086 | 1084 | Terpinolene | 11.17 | 0.39 | ||

| 15.87 | 1095 | 1099 | Linalool | 0.30 | 1.74 | ||

| 16.07 | 1112 | 1118 | trans-Thujone | 0.09 | |||

| 16.15 | 1114 | 1119 | endo-Fenchol | 0.33 | |||

| 16.48 | 1118 | 1123 | cis-p-Ment-2-en-1-ol | 0.08 | |||

| 16.89 | 1122 | 1126 | α-Campholenal | 0.38 | 0.14 | ||

| 17.32 | 1135 | 1140 | trans-Pinocarveol | 4.46 | 0.36 | ||

| 17.54 | 1137 | 1149 | cis-Verbenol | 0.49 | 0.15 | ||

| 17.76 | 1154 | 1156 | Sabina ketone | 0.27 | |||

| 17.94 | 1160 | 1162 | Pinocarvone | 2.35 | 0.16 | ||

| 17.98 | 1166 | 1168 | p-Mentha-1,5-dien-8-ol | 1.26 | 0.11 | ||

| 18.03 | 1167 | 1169 | Umbellulone | 0.04 | |||

| 18.09 | 1174 | 1180 | Terpinen-4-ol | 1.16 | 1.06 | ||

| 18.51 | 1179 | 1186 | p-Cymen-8-ol | 3.36 | 0.71 | ||

| 18.74 | 1186 | 1194 | α -Terpineol | 0.97 | |||

| 18.82 | 1195 | 1196 | Myrtenal | 3.24 | |||

| 18.91 | 1204 | 1207 | Verbenone | 1.62 | 0.1 | ||

| 19.13 | 1215 | 1218 | trans-Carveol | 0.33 | |||

| 19.22 | 1239 | 1243 | Carvone | 0.23 | |||

| 19.38 | 1249 | 1248 | Geraniol | 0.39 | |||

| 19.53 | 1335 | 1335 | δ-Elemene | 2.32 | 4.41 | ||

| 19.68 | 1345 | 1345 | α-Cubebene | 0.74 | 0.08 | ||

| 19.95 | 1373 | 1367 | α-Ylangene | 1.35 | |||

| 20.37 | 1374 | 1368 | Isoledene | 0.02 | |||

| 20.90 | 1374 | 1374 | α-Copaene | 0.25 | 1.07 | 0.25 | |

| 21.56 | 1379 | 1378 | Geranyl acetate | 1.38 | |||

| 22.02 | 1387 | 1381 | β-Bourbonene | 0.93 | |||

| 22.95 | 1389 | 1389 | β-Elemene | 0.74 | 0.49 | 3.10 | 0.54 |

| 23.68 | 1409 | 1405 | α-Gurjunene | 0.11 | 0.06 | ||

| 23.82 | 1417 | 1422 | (E)-Caryophyllene | 2.98 | 1.56 | 0.93 | 0.03 |

| 24.17 | 1419 | 1416 | β-Ylangene | 0.72 | |||

| 25.04 | 1434 | 1429 | γ-Elemene | 0.19 | 0.39 | ||

| 25.26 | 1439 | 1439 | Aromadendrene | 0.75 | 0.39 | ||

| 26.13 | 1442 | 1442 | 6,9-Guaiadiene | 0.06 | |||

| 26.58 | 1451 | 1450 | trans-Muurola-3,5-diene | 0.38 | |||

| 26.81 | 1452 | 1452 | α-Humulene | 0.73 | 1.40 | 0.35 | 0.10 |

| 27.05 | 1458 | 1456 | allo-Aromadendrene | 0.11 | |||

| 27.19 | 1464 | 1465 | (E)-9-epi-caryophyllene | 0.26 | |||

| 27.81 | 1471 | 1470 | Dauca-5,8-diene | 0.29 | |||

| 27.98 | 1478 | 1484 | γ -Muurolene | 3.06 | |||

| 28.10 | 1484 | 1492 | Germacrene D | 1.24 | 1.34 | 1.08 | 3.26 |

| 28.18 | 1489 | 1487 | β-Selinene | 1.61 | |||

| 28.29 | 1493 | 1494 | epi-Cubebol | 0.91 | |||

| 28.33 | 1495 | 1490 | γ-Amorphene | 0.67 | |||

| 28.52 | 1496 | 1489 | Viridiflorene | 0.56 | |||

| 28.61 | 1500 | 1497 | Bicyclogermacrene | 0.21 | 7.85 | ||

| 28.91 | 1500 | 1498 | α-Muurolene | 0.95 | |||

| 29.03 | 1513 | 1513 | γ-Cadinene | 2.67 | 0.13 | ||

| 29.17 | 1514 | 1513 | Cubebol | 0.68 | 0.05 | ||

| 29.57 | 1522 | 1520 | δ-Cadinene | 1.61 | 0.38 | ||

| 29.98 | 1528 | 1520 | cis-Calamenene | 2.06 | 4.01 | 0.48 | |

| 30.06 | 1533 | 1531 | trans-Cadina-1,4-diene | 0.16 | 0.01 | ||

| 30.24 | 1533 | 1534 | 10-epi-Cubebol | 0.09 | |||

| 30.39 | 1537 | 1536 | α-Cadinene | 0.24 | |||

| 30.58 | 1539 | 1540 | α-Copaen-11-ol | 0.04 | |||

| 30.67 | 1544 | 1540 | α-Calacorene | 1.47 | |||

| 30.83 | 1548 | 1548 | Elemol | 0.06 | |||

| 31.57 | 1564 | 1561 | β-Calacorene | 0.65 | |||

| 31.97 | 1577 | 1579 | Spathulenol | 1.87 | 22.22 | 5.65 | 2.18 |

| 32.28 | 1582 | 1583 | Caryophyllene oxide | 2.49 | 12.21 | 5.63 | 0.18 |

| 32.51 | 1590 | 1589 | Globulol | 1.10 | |||

| 32.62 | 1592 | 1593 | Viridiflorol | 0.61 | 0.54 | ||

| 32.76 | 1595 | 1594 | Cubeban-11-ol | 0.23 | |||

| 32.85 | 1596 | 1596 | Fokienol | 2.48 | |||

| 32.92 | 1600 | 1604 | Rosifoliol | 0.23 | |||

| 33.09 | 1602 | 1601 | Ledol | 0.10 | |||

| 33.25 | 1608 | 1609 | Humulene Epoxide II | 0.21 | 11.86 | 1.41 | |

| 33.81 | 1630 | 1630 | Muurola-4,10(14)-dien-1-β-ol | 4.70 | |||

| 34.18 | 1638 | 1643 | epi-α-Cadinol | 0.09 | |||

| 34.36 | 1639 | 1657 | Allo-Aromadendrene Epoxide | 10.20 | 0.02 | ||

| 34.45 | 1639 | 1661 | Caryophylla-4(12),8(13)-dien-5-α-ol | 1.36 | |||

| 34.51 | 1640 | 1664 | epi-α-Muurolol | 0.12 | |||

| 34.71 | 1644 | 1669 | α-Muurolol | 0.83 | |||

| 34.84 | 1645 | 1672 | Cubenol | 2.57 | 0.68 | ||

| 34.89 | 1648 | 1678 | cis-Guaia-3,9-dien-11-ol | 0.54 | |||

| 34.93 | 1652 | 1681 | α-Cadinol | 3.45 | 0.30 | ||

| 35.49 | 1668 | 1684 | trans-Calamenen-10-ol | 0.30 | |||

| 35.62 | 1668 | 1692 | 14-Hydroxy-9-epi-(E)-caryophyllene | 1.00 | |||

| 35.94 | 1676 | 1694 | Mustakone | 3.36 | |||

| 36.28 | 1685 | 1695 | Germacra-4(15),5,10(14)-trien-1-α-ol | 0.76 | 1.40 | 0.04 | |

| 39.41 | 1767 | 1768 | 14-oxi-α-Muurolene | 0.48 | |||

| 59.61 | 2400 | 2408 | Tetracosane | 0.02 | |||

| 62.38 | 2500 | 2512 | Pentacosane | 0.02 | |||

| Monoterpenes hydrocarbon Oxygenated monoterpenes Sesquiterpenes hydrocarbon Oxygenated sesquiterpenes Others class |

78.99 | 1.80 | 8.41 | 62.53 | |||

| 4.52 | 0 | 19.45 | 6.17 | ||||

| 8.32 | 8.50 | 27.42 | 19.05 | ||||

| 4.57 | 71.76 | 22.99 | 5.03 | ||||

| - | - | 3.42 | 2.30 | ||||

| Total | 96.4 | 82.06 | 81.69 | 95.08 | |||

RT: Retention Time; RIC = Calculated retention index; RIL = Literature retention index; DE: Duguetia echinophora; DR: Duguetia riparia; XE: Xylopia emarginata; XF: Xylopia frutescens.

The chemical compositions of the EOs of D. echinophora, D. riparia, X. emarginata and X. frutescens were characterized by GC-MS, and a total of 22, 19, 59 and 62 components were identified, representing 96.40, 82.06, 81.69 and 95.08% of the total EOs for each species, respectively. The hydrocarbon monoterpenes compounds represented the most abundant class in the EOs of D. echinophora (78.99%) and X. frutescens (62.53%), and the oxygenated sesquiterpenes class characterized the EO of D. riparia (71.76%). The compounds β-Phellandrene (39.12%), sabinene (17.08%) and terpinolene (11.17%) were dominant in the D. echinophora EO, while spathulenol (22.22%), caryophyllene oxide (12.21%), humulene epoxide II (11.86%) and allo-aromadendrene epoxide (10.20%) were the major constituents of the D. riparia EO. The EO of X. emarginata was characterized by spathulenol (5.65%) and caryophyllene oxide (5.63%), and X. frutescens EO was characterized by α-pinene (20.84%) and byciclogermacrene (7.85%). Ion chromatograms are available in the Supplementary Material.

According to data previous published, the chemical compositions of the EOs of Annonaceae species occurring in Brazil are predominantly characterized by substances belonging to the class of mono and sesquiterpenes, and among these compounds, the most abundant are β-elemene, α-pinene, β-pinene limonene, bicyclogermacrene, (E)-caryophyllene, caryophyllene oxide, spathulenol, and germacrene D, [9].

Previous reports have investigated the chemical composition of the EOs from the Annonaceae species described in this work (D. riparia, X. emarginata and X. frutescens). The leaves and fine stems EO of D. riparia, also collected in State of Pará-Brazil, showed spathulenol (46.5%), caryophyllene oxide (28.9%) and α-pinene (6.1%) as their main compounds [24], and quantitative differences were observed for the constituents spathulenol and caryophyllene oxide in relation to the D. riparia EO described in the present work. The EO from the leaves of X. emarginata, collected in Caxiuanã National Forest, Melgaço, State of Pará-Brazil, showed a high percentage of sesquiterpene spathulenol (73.0%) [11], whereas in the present work, this constituent was obtained at a low percentage (5.65%) [25]. The EO from the leaves of X. frutescens, collected in Municipality of Capela, Sergipe State, Brazil, had as its major compounds (E)-caryophyllene (31.48%), bicyclogermacrene (15.13%), germacrene D (9.66%), δ-cadinene (5.44%), viridiflorene (5.09%) and α-copaene (4.35%) [26], while the EO from the leaves of the specimen collected in the city of Itabaiana, Sergipe-Brazil, had as its major constituents bicyclogermacrene (23.23%), (E)-caryophyllene (17.24%), β-elemene (6.35%) and (E)-β-ocimene (5.23%) [27].

The chemical composition of EOs can be strongly influenced by several factors, including season, climate, geography, age, genotype, organ, development periods, collection place and even extraction method, etc. [49,50,51]. Figueiredo and collaborators evaluated the influence of seasonal variation on the EO of Eugenia patrisii Vahl (Myrtaceae) and verified a potential correlation between the content of the main constituents of the essential oil and climatic parameters (temperature, insolation and humidity rate) [52]. The EOs of Flos Chrysanthemi indici, an important medicinal and aromatic plant in China, were obtained by different extraction techniques, hydrodistillation (HD), steam distillation (SD), solvent-free microwave extraction (SFME) and supercritical fluid extraction (SFE), and the authors found that the EO yield, chemical composition and bioactivities varied according to the extraction method used [53]. Some Annonaceae species have shown qualitative and quantitative variability in their EO compositions according to different collection sites. The EOs from the leaves of Annona vepretorum Mart. collected in the State of Sergipe, Brazil, showed bicyclogermacrene, spathulenol and α-phellandrene as the major constituents [54], while another specimen collected in the State of Pernambuco, Brazil, showed α-pinene, limonene, spathulenol and caryophyllene oxide as the compounds with higher percentage [55]. The compounds α-selinene, aristolochene, (E)-caryophyllene and (E)-calamenene were identified as the major constituents of EO from leaves of a specimen of Duguetia lanceolata collected in the state of Minas Gerais, Brazil [23], while another specimen collected in the State of São Paulo, Brazil, had as its main constituents of the EO the compounds trans-muurola-4(14),5-diene, β-bisabolene, 3,4,5-trimethoxy-styrene and 2,4,5-trimethoxy-styrene [56].

3.2. Multivariate Analyses

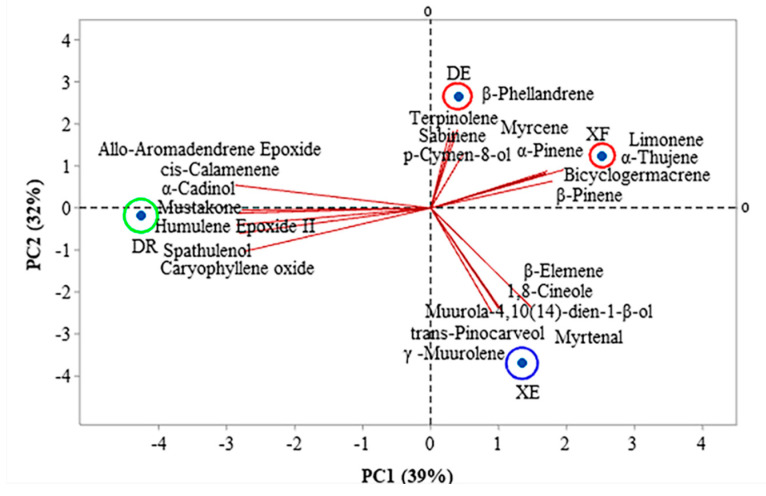

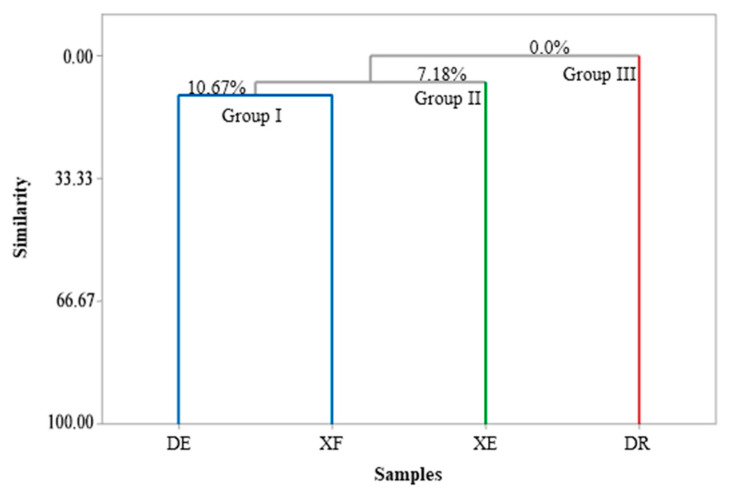

Figure 1 and Figure 2 show the correlations between the classes of compounds identified in the different samples according to the multivariate analyses, principal component analysis (PCA) and hierarchical cluster analysis (HCA), respectively. PC1 and PC2 represent the principal components (PC), which contained 39.0% and 32.0% of the variables, respectively, and accounted for 71.0% of the variance in the analyzed data. In the HCA analysis, tree groups were observed that show the similarity between the identified classes. Group I, including the samples of EOs from D. echinophora and X. frutescens showed a similarity of 10.67% (Figure 2) and comprised the compounds β-phellandrene, p-cymen-8-ol, bicyclogermacrene, terpinolene, α-pinene, sabinene, myrcene, limonene, β-pinene and α-thujene (Figure 1). Groups II and III contained only one sample each and comprised β-elemene, 1,8-cineol, muurola-4,10(14)-dien-1-β-ol, trans-pinocarveol, myrtenal and γ-muurolene (X. emarginata EO) and cis-calamenene, α-cadinol, mustakone, allo-aromadendrene epoxide, humulene epoxide II, spathulenol and caryophyllene oxide (D. riparia EO), with similarities of 7.18% and 0%, respectively (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Biplot (principal component analysis) for the chemical analysis of the essential oils from Annonaceae species. DE: Duguetia echinophora; DR: Duguetia riparia; XE: Xylopia emarginata; XF: Xylopia frutescens.

Figure 2.

Dendrogram presenting the relational similarity of the chemical composition of the essential oils from Annonaceae species. DE: Duguetia echinophora; DR: Duguetia riparia; XE: Xylopia emarginata; XF: Xylopia frutescens.

3.3. Antioxidant Capacity

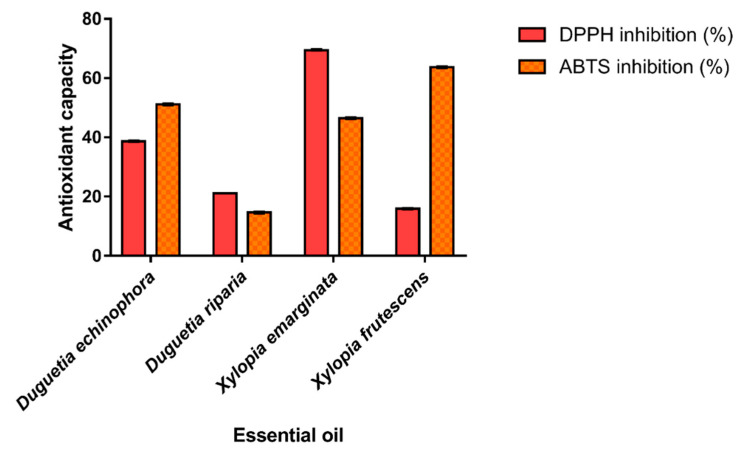

The antioxidant potential of the EOs from Annonaceae species was evaluated based on their ability to scavenge stable free DPPH• (2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl) and ABTS•+ (2,2′-Azino-bis (3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) radicals; the results are shown in Figure 3. The results of the DPPH assays ranged from 15.87 to 69.38% and the highest percentage of inhibition was observed for the EO of X. emarginata, characterized by spathulenol (5.65%) and caryophyllene oxide (5.63%). For ABTS radical scavenging, the antioxidant capacity of EOs ranged from 14.61 to 63.67%. The species X. frutescens showed the higher antioxidant capacity by the ABTS•+ assay. This may be due to the presence of α-Pinene (20.84%) and β-Pinene (25.95%), the major components present in this EO. Possibly, the antioxidant activity of the X. emarginata EO can also be attributed to its main components which are described as antioxidants [57,58]. The high free radical scavenging effect of this sample may be related to the fact that the combination of the numerous organic chemical constituents present in EOs have a synergistic effect, increasing the biological activity or, conversely, an antagonistic effect [59]. In addition, bioactive compounds belonging to the monoterpenoid class have antioxidant activity, as reported in the literature [60].

Figure 3.

ABTS•+ and DPPH• radical scavenging assay and Trolox equivalent antioxidant capacity of essential oils. Values are expressed as mean and standard deviation (n = 3) of Trolox equivalent antioxidant capacity.

Other studies investigating EOs of the Duguetia and Xylopia genera identified antioxidant effects. The EO of Xylopia sericea A. St.-Hil. showed significant antioxidant activity using DPPH (IC50 49.1 μg·mL−1), β-carotene/linoleic acid bleaching (IC50 6.9 μg·mL−1), TAC (IC50 78.2 μg·mL−1) and TBARS (IC50 80.0 μg·mL−1) methods [20]. The EO of Duguetia lanceolata St. Hil. branches showed antioxidant effects using a DPPH assay (EC50 159.4 μg·mL−1), Fe+3 reduction (EC50 187.8 μg·mL−1) and inhibition of lipid peroxidation (41.5%); the authors suggest that caryophyllene oxide is one of the active compounds found in this EO [21].

3.4. Cytotoxic Activity of Essential Oils

The toxicity of the EOs from Annonaceae species was measured in terms of LC50 (lethal concentration) with two negative control groups (control 1:10 nauplii and artificial sea-water with DMSO 0.1%; control 2: 10 nauplii and artificial seawater) and one positive control (K2Cr2O7, 50 µg·mL−1). The values are shown in Table 2. Values of LC50 < 80 µg·mL−1 are considered highly toxic [15,61,62]; values of LC50 within the range 80 to 250 µg·mL−1 are moderately toxic; and LC50> 250 µg·mL−1 are considered as low toxicity or non-toxic [63]. The EOs of D. echinophora, X. emarginata and X. frutescens showed high toxicity, whereas the EO of D. riparia showed low toxicity or was non-toxic. The major compounds from the EOs of X. emarginata (spathulenol and caryophyllene oxide) [64,65], D. echinophora (β-phellandrene and terpinolene) [66,67] and X. frutescens (α-pinene and byciclogermacrene) [68,69] showed cytotoxic effects and these results indicate that the cytotoxic potential observed for the EOs tested may be related to the presence of these secondary metabolites.

Table 2.

LC50 concentrations of the essential oils using Artemia salina assay.

| Essential Oil | LC50 (µg·mL−1) |

|---|---|

| Duguetia echinophora | 28.00 ± 0.30 |

| Duguetia riparia | 310.80 ± 0.70 |

| Xylopia emarginata | 26.72 ± 0.17 |

| Xylopia frutescens | 54.36 ± 0.20 |

| Positive control (K2Cr2O7) | 50.00 ± 0.00 |

Values are expressed as mean and standard deviation (n = 3).

Toxicity tests in A. Salina performed with Coriandrum sativum L. (Apiaceae) showed an LC50 value of 23 µg/mL−1 [70], which is similar to those obtained in the present work for D. echinophora and X. emarginata EOs. Oliva and coworkers evaluated toxicity of the EOs from some medicinal plants, and the results showed a decreasing activity in the brine assay of Aloysia polystachia (Verbenaceae) (LC50 6459 µg·mL−1), Aloysia triphylla (Verbenaceae) (LC50 1279 µg·mL−1), Minthostachys verticillata (Myrtaceae) (LC50 1848 µg·mL−1), and Schinus poligamus (Anacardiaceae) (LC50 1179 µg·mL−1), that were considered nontoxic [71], Other authors have also reported the toxicity of essential oils from a variety of plants [17,72,73].

The essential oils of Duguetia species have been studied by using the A. salina bioassay. The EOs from the leaves, underground heartwood and underground stem bark of Duguetia furfuracea (A. St. -Hil.) Saff. showed potent activity against A. salina larvae (LC50 6.01, 7.79 and 9.98 μg·mL−1, respectively) and the leaf EO from D. lanceolata also showed potent activity against the same larvae (LC50 0.89 μg·mL−1) [23]. In another study, the EOs of D. lanceolata showed toxicity against A. salina with LC50 values of 49.0 μg·mL−1 (2 h of hydrodistillation extraction) and 60.7 μg·mL−1 (4h of hydrodistillation extraction) [74].

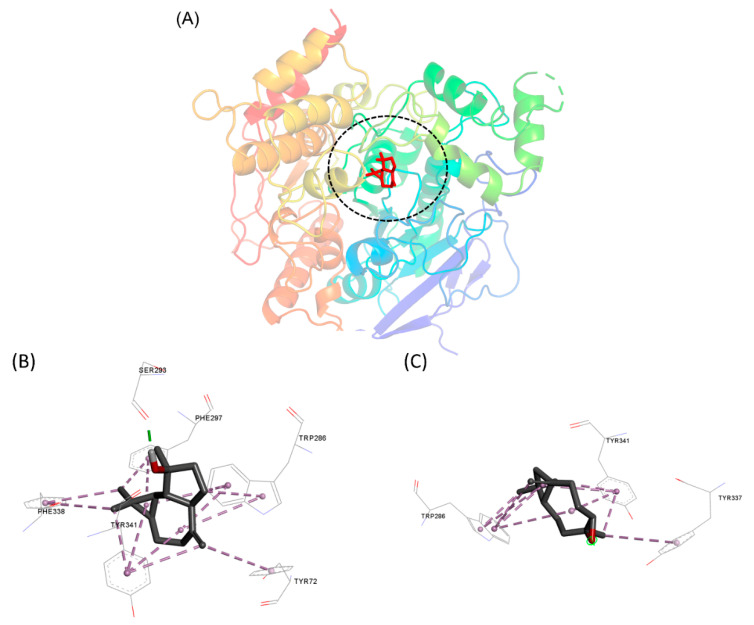

3.5. Molecular Docking

Molecular modeling approaches have been used to investigate how natural compounds interact with molecular targets of pharmacological interest [75,76,77,78]. One of the tools used has been molecular docking, which can provide insights into how these compounds interact with the binding pocket of proteins. Here, we use this approach to assess how the major compounds of the EO from X. emarginata interact with the AChE active site, as this target is closely related to the toxicity mechanism observed in the A. salina assays [79,80]. Spathulenol formed hydrophobic interactions with various residues such as Ser293, Phe297, Trp286, Tyr72, Tyr341, and Phe338. A hydrogen bond was established with Ser293. Caryophyllene oxide established pi-alkyl hydrophobic interactions with Trp286, Tyr341 and Tyr337 (Figure 4). The interaction between spathulenol and caryophyllene with the active site of AChE has already been described [58] and this could be the likely mechanism responsible for the cytotoxicity of the EO from X. emarginata.

Figure 4.

(A) Binding pocket of interaction of compounds with AChE. Molecular interactions established by (B) spathulenol and (C) caryophyllene oxide with the AChE active site.

4. Conclusions

The present study presents new insights concerning the chemical composition, antioxidant activity and preliminary toxicity of some Annonaceae EOs. Essential oils obtained from D. echinophora, X. emarginata and X. frutescens showed high toxicity, compared with EO obtained from D. riparia, which showed low toxicity or was non-toxic. The cytotoxicity test against A. salina can be considered as a good preliminary assessment of bioactive compounds, and may indicate a potential biological activity. The docking results elucidated the interaction mode of the major compounds of X. emarginata EO, spathulenol and caryophyllene, with the active site of the enzyme Acetylcholinesterase. The greatest capacities to scavenge DPPH and ABTS radicals were found in the essential oils of X. emarginata and X. frutescens, respectively, and the main constituents of the EO of this species may play the main role in the observed antioxidant capacity; however, the impact of less abundant constituents also should be considered.

Acknowledgments

The author M.M.C. thanks CAPES for the Ph.D. scholarship process number: [88887.497476/2020-00]. Â.A.B.D.M. thanks CNPq for the scientific initiation scholarship. The author M.S.d.O., thanks PCI-MCTIC/MPEG, as well as CNPq for the process number: [302050/2021-3]. The authors would like to thank the Universidade Federal do Pará.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/antiox11091709/s1, Figure S1: Ions-chromatogram relating to the chemical profile of essential oils from different species of Annonaceae Xylopia.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.M.C., M.S.d.O. and L.D.d.N.; methodology, M.M.C., O.O.F., L.D.d.N., Â.A.B.D.M.; R.C.E.S.; J.N.C., T.O.d.A. and C.d.J.P.F.; writing—original draft preparation, M.M.C.; writing—review and editing, L.D.d.N., G.M.S.P.G. and M.S.d.O.; visualization, G.M.S.P.G. and E.H.d.A.A.; supervision, G.M.S.P.G. and E.H.d.A.A.; project administration, E.H.d.A.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data are contained within the article and supplementary materials.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding Statement

This study was financed in part by the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior-Brazil (CAPES)-Finance Code 001. Universidade Federal do Pará. Pró-Reitoria de Pesquisa e Pós-Graduação (PROPESP), Programa de Apoio à Publicação Qualificada-PAPQ, EDITAL 02/2022–PROPESP. The APC was funded by Universidade Federal do Pará.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Rehman R., Hanif M.A., Mushtaq Z., Al-Sadi A.M. Biosynthesis of essential oils in aromatic plants: A review. Food Rev. Int. 2016;32:117–160. doi: 10.1080/87559129.2015.1057841. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ferreira O.O., Cruz J.N., de Moraes Â.A., de Jesus Pereira Franco C., Lima R.R., Anjos T.O., Siqueira G.M., Nascimento L.D., Cascaes M.M., de Oliveira M.S., et al. Essential Oil of the Plants Growing in the Brazilian Amazon: Chemical Composition, Antioxidants, and Biological Applications. Molecules. 2022;27:4373. doi: 10.3390/molecules27144373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Perricone M., Arace E., Corbo M.R., Sinigaglia M., Bevilacqua A. Bioactivity of essential oils: A review on their interaction with food components. Front. Microbiol. 2015;6:76. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2015.00076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tohidi B., Rahimmalek M., Trindade H. Industrial Crops & Products Review on essential oil, extracts composition, molecular and phytochemical properties of Thymus species in Iran. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2019;134:89–99. doi: 10.1016/j.indcrop.2019.02.038. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Santana de Oliveira M., da Cruz J.N., Almeida da Costa W., Silva S.G., Brito M.d.P., de Menezes S.A.F., de Jesus Chaves Neto A.M., de Aguiar Andrade E.H., de Carvalho Junior R.N. Chemical Composition, Antimicrobial Properties of Siparuna guianensis Essential Oil and a Molecular Docking and Dynamics Molecular Study of its Major Chemical Constituent. Molecules. 2020;25:3852. doi: 10.3390/molecules25173852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ferreira O.O., Neves da Cruz J., de Jesus Pereira Franco C., Silva S.G., da Costa W.A., de Oliveira M.S., de Aguiar Andrade E.H. First report on yield and chemical composition of essential oil extracted from myrcia eximia DC (Myrtaceae) from the Brazilian Amazon. Molecules. 2020;25:783. doi: 10.3390/molecules25040783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Silva S.G., de Oliveira M.S., Cruz J.N., da Costa W.A., da Silva S.H.M., Barreto Maia A.A., de Sousa R.L., Carvalho Junior R.N., de Aguiar Andrade E.H. Supercritical CO2 extraction to obtain Lippia thymoides Mart. & Schauer (Verbenaceae) essential oil rich in thymol and evaluation of its antimicrobial activity. J. Supercrit. Fluids. 2021;168:105064. doi: 10.1016/j.supflu.2020.105064. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carvalho R.N.d., Oliveira M.S.d.M.S.d., Silva S.G., Cruz J.N.d., Ortiz E., Costa W.A.d., Bezerra F.W.F., Cunha V.M.B., Cordeiro R.M., Neto A.M.d.J.C., et al. Supercritical CO2 Application in Essential Oil Extraction. In: Inamuddin R.M., Asiri A.M., editors. Materials Research Foundations. Volume 54. Materials Research Foundations; Millersville PA, USA: 2019. pp. 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cascaes M.M., Dos O., Carneiro S., Diniz Do Nascimento L., Antônio Barbosa De Moraes Â., Santana De Oliveira M., Neves Cruz J., Skelding G.M., Guilhon P., Helena De Aguiar Andrade E., et al. Essential Oils from Annonaceae Species from Brazil: A Systematic Review of Their Phytochemistry, and Biological Activities. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021;22:12140. doi: 10.3390/ijms222212140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bezerra F.W.F.W.F., De Oliveira M.S.S., Bezerra P.N.N., Cunha V.M.B.M.B., Silva M.P.P., da Costa W.A.A., Pinto R.H.H.H.H., Cordeiro R.M.M., Da Cruz J.N.N., Chaves Neto A.M.J.M.J., et al. Green Sustainable Process for Chemical and Environmental Engineering and Science. Elsevier; Amsterdam, The Netherlands: 2020. Extraction of bioactive compounds; pp. 149–167. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sharmeen J.B., Mahomoodally F.M., Zengin G., Maggi F. Essential Oils as Natural Sources of Fragrance Compounds for Cosmetics and Cosmeceuticals. Molecules. 2021;26:666. doi: 10.3390/molecules26030666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Miguel M.G. Antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities of essential oils: A short review. Molecules. 2010;15:9252–9287. doi: 10.3390/molecules15129252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Do Nascimento L.D., de Moraes A.A.B., da Costa K.S., Galúcio J.M.P., Taube P.S., Costa C.M.L., Cruz J.N., Andrade E.H.d.A., de Faria L.J.G. Bioactive natural compounds and antioxidant activity of essential oils from spice plants: New findings and potential applications. Biomolecules. 2020;10:988. doi: 10.3390/biom10070988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ramos Da Silva L.R., Ferreira O.O., Cruz J.N., De Jesus Pereira Franco C., Oliveira Dos Anjos T., Cascaes M.M., Almeida Da Costa W., Helena De Aguiar Andrade E., Santana De Oliveira M. Lamiaceae Essential Oils, Phytochemical Profile, Antioxidant, and Biological Activities. Evid.-Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2021;2021:6748052. doi: 10.1155/2021/6748052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mesquita K.d.S.M., Feitosa B.d.S., Cruz J.N., Ferreira O.O., Franco C.d.J.P., Cascaes M.M., Oliveira M.S.d., Andrade E.H.d.A. Chemical Composition and Preliminary Toxicity Evaluation of the Essential Oil from Peperomia circinnata Link var. circinnata. (Piperaceae) in Artemia salina Leach. Molecules. 2021;26:7359. doi: 10.3390/molecules26237359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Radulović N.S., Mladenović M.Z., Randjelovic P.J., Stojanović N.M., Dekić M.S., Blagojević P.D. Toxic essential oils. Part IV: The essential oil of Achillea falcata L. as a source of biologically/pharmacologically active trans-sabinyl esters. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2015;80:114–129. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2015.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Santana de Oliveira M., Pereira da Silva V.M., Cantão Freitas L., Gomes Silva S., Nevez Cruz J., Aguiar Andrade E.H. Extraction Yield, Chemical Composition, Preliminary Toxicity of Bignonia nocturna (Bignoniaceae) Essential Oil and in Silico Evaluation of the Interaction. Chem. Biodivers. 2021;18:cbdv.202000982. doi: 10.1002/cbdv.202000982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tamokou J.d.D., Mbaveng A.T., Kuete V. Medicinal Spices and Vegetables from Africa: Therapeutic Potential Against Metabolic, Inflammatory, Infectious and Systemic Diseases. Elsevier Inc.; Amsterdam, The Netherlands: 2017. Antimicrobial Activities of African Medicinal Spices and Vegetables; pp. 207–237. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maas P., Lobão A., Rainer H. Annonaceae Juss. [(accessed on 28 July 2022)]; Available online: http://floradobrasil.jbrj.gov.br.

- 20.Mendes R.d.F., Pinto N.d.C.C., da Silva J.M., da Silva J.B., Hermisdorf R.C.d.S., Fabri R.L., Chedier L.M., Scio E. The essential oil from the fruits of the Brazilian spice Xylopia sericea A. St.-Hil. presents expressive in-vitro antibacterial and antioxidant activity. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2017;69:341–348. doi: 10.1111/jphp.12698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.de Sousa O.V., Del-Vechio-Vieira G., Santos B.C.S., Yamamoto C.H., Araújo A.L.S.d., de Araújo A.d.A., Pinto M.A.d., Rodarte M.P., Alves M.S. In-vivo and vitro bioactivities of the essential oil of Duguetia lanceolata branches. Afr. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2016;10:298–310. doi: 10.5897/ajpp2015.4497. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Costa E.V., Dutra L.M., Ramos De Jesus H.C., De Lima Nogueira P.C., De Souza Moraes V.R., Salvador M.J., De Holanda Cavalcanti S.C., La Corte Dos Santos R., Do Nacimento Prata A.P. Chemical composition and antioxidant, antimicrobial, and larvicidal activities of the essential oils of Annona salzmannii and A. pickelii (Annonaceae) Nat. Prod. Commun. 2011;6:907–912. doi: 10.1177/1934578X1100600636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Maia D.S., Lopes C.F., Saldanha A.A., Silva N.L., Sartori Â.L.B., Carollo C.A., Sobral M.G., Alves S.N., Silva D.B., de Siqueira J.M. Larvicidal effect from different Annonaceae species on Culex quinquefasciatus. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020;27:36983–36993. doi: 10.1007/s11356-020-08997-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maia J.G.S., Andrade E.H.A., Carreira L.M.M., Oliveira J. Essential oil composition from duguetia species (annonaceae) J. Essent. Oil Res. 2006;18:60–63. doi: 10.1080/10412905.2006.9699386. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Maia J.G.S., Andrade E.H.A., Carla A., Silva M., Oliveira J., Carreira L.M.M., Araújo J.S. Leaf volatile oils from four Brazilian Xylopia species. Flavour Fragr. J. 2005;20:474–477. doi: 10.1002/ffj.1499. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ferraz R.P.C., Cardoso G.M.B., Da Silva T.B., Fontes J.E.D.N., Prata A.P.D.N., Carvalho A.A., Moraes M.O., Pessoa C., Costa E.V., Bezerra D.P. Antitumour properties of the leaf essential oil of Xylopia frutescens Aubl. (Annonaceae) Food Chem. 2013;141:542–547. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2013.02.114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nascimento A.M.D., Maia T.D.S., Soares T.E.S., Menezes L.R.A., Scher R., Costa E.V., Cavalcanti S.C.H., La Corte R. Repellency and Larvicidal Activity of Essential oils from Xylopia laevigata, Xylopia frutescens, Lippia pedunculosa, and Their Individual Compounds against Aedes aegypti Linnaeus. Neotrop. Entomol. 2017;46:223–230. doi: 10.1007/s13744-016-0457-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Alcântara J.M., De Lucena J.M.V.M., Facanali R., Marques M.O.M., Da Paz Lima M. Chemical composition and bactericidal activity of the essential oils of four species of annonaceae growing in brazilian amazon. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2017;12:619–622. doi: 10.1177/1934578X1701200437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Agra M.D.F., Freitas P.F.D., Barbosa-filho J.M. Divulgação Synopsis of the plants known as medicinal and poisonous in Northeast of Brazil. Brazilian J. Pharmacogn. 2007;17:114–140. doi: 10.1590/S0102-695X2007000100021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cascaes M.M., Silva S.G., Cruz J.N., Santana de Oliveira M., Oliveira J., Moraes A.A.B.d., Costa F.A.M.d., da Costa K.S., Diniz do Nascimento L., Helena de Aguiar Andrade E. First report on the Annona exsucca DC. Essential oil and in silico identification of potential biological targets of its major compounds. Nat. Prod. Res. 2021;35:4009–4012. doi: 10.1080/14786419.2021.1893724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Do Nascimento L.D., Silva S.G., Cascaes M.M., da Costa K.S., Figueiredo P.L.B., Costa C.M.L., Andrade E.H.d.A., de Faria L.J.G. Drying effects on chemical composition and antioxidant activity of lippia thymoides essential oil, a natural source of thymol. Molecules. 2021;26:2621. doi: 10.3390/molecules26092621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Franco C.d.J.P., Ferreira O.O., Antônio Barbosa de Moraes Â., Varela E.L.P., Do Nascimento L.D., Percário S., de Oliveira M.S., Andrade E.H.D.A. Chemical composition and antioxidant activity of essential oils from eugenia patrisii vahl, e. Punicifolia (kunth) dc., and myrcia tomentosa (aubl.) dc., leaf of family myrtaceae. Molecules. 2021;26:3292. doi: 10.3390/molecules26113292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ferreira O.O., da Silva S.H.M., de Oliveira M.S., Andrade E.H.d.A. Chemical Composition and Antifungal Activity of Myrcia multiflora and Eugenia florida Essential Oils. Molecules. 2021;26:7259. doi: 10.3390/molecules26237259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.van Den Dool H., Kratz P.D. A generalization of the retention index system including linear temperature programmed gas—liquid partition chromatography. J. Chromatogr. A. 1963;11:463–471. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9673(01)80947-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Adams R.P. Identification of Essential Oil Components by Gas Chromatography/Mass Spectrometry. 4th ed. Volume 8. Allured Publ.; Carol Stream, IL, USA: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Miller N.J., Rice-Evans C., Davies M.J., Gopinathan V., Milner A. A novel method for measuring antioxidant capacity and its application to monitoring the antioxidant status in premature neonates. Clin. Sci. 1993;84:407–412. doi: 10.1042/cs0840407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Re R., Pellegrini N., Proteggente A., Pannala A., Yang M., Rice-Evans C. Antioxidant activity applying an improved ABTS radical cation decolorization assay. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 1999;26:1231–1237. doi: 10.1016/S0891-5849(98)00315-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Blois M.S. Antioxidant determinations by the use of a stable free radical. Nature. 1958;181:1199–1200. doi: 10.1038/1811199a0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rebelo M.M., Da Silva J.K.R., Andrade E.H.A., Maia J.G.S. Antioxidant capacity and biological activity of essential oil and methanol extract of Hyptis crenata Pohl ex Benth. Rev. Bras. Farmacogn. 2009;19:230–235. doi: 10.1590/S0102-695X2009000200009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dennington R., Keith T., Millam J. GaussView, version 5. Semichem Inc.; Shawnee Mission, KS, USA: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Almeida V.M., Dias Ê.R., Souza B.C., Cruz J.N., Santos C.B.R., Leite F.H.A., Queiroz R.F., Branco A. Methoxylated flavonols from Vellozia dasypus Seub ethyl acetate active myeloperoxidase extract: In vitro and in silico assays. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2021:1–10. doi: 10.1080/07391102.2021.1900916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Becke A.D. Density-functional thermochemistry. III. The role of exact exchange. J. Chem. Phys. 1993;98:5648–5652. doi: 10.1063/1.464913. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.dos Santos K.L.B., Cruz J.N., Silva L.B., Ramos R.S., Neto M.F.A., Lobato C.C., Ota S.S.B., Leite F.H.A., Borges R.S., da Silva C.H.T.P., et al. Identification of novel chemical entities for adenosine receptor type 2a using molecular modeling approaches. Molecules. 2020;25:1245. doi: 10.3390/molecules25051245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Frisch M.J., Trucks G.W., Schlegel H.B., Scuseria G.E., Robb M.A., Cheeseman J.R., Barone V., Mennucci B., Petersson G.A., Nakatsuji H., et al. Gaussian 09. 2009. [(accessed on 28 July 2022)]. Available online: https://gaussian.com/g09citation/

- 45.Thomsen R., Christensen M.H. MolDock: A new technique for high-accuracy molecular docking. J. Med. Chem. 2006;49:3315–3321. doi: 10.1021/jm051197e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pinto V.d.S., Araújo J.S.C., Silva R.C., da Costa G.V., Cruz J.N., Neto M.F.D.A., Campos J.M., Santos C.B.R., Leite F.H.A., Junior M.C.S. In silico study to identify new antituberculosis molecules from natural sources by hierarchical virtual screening and molecular dynamics simulations. Pharmaceuticals. 2019;12:36. doi: 10.3390/ph12010036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Castro A.L.G., Cruz J.N., Sodré D.F., Correa-Barbosa J., Azonsivo R., de Oliveira M.S., de Sousa Siqueira J.E., da Rocha Galucio N.C., de Oliveira Bahia M., Burbano R.M.R., et al. Evaluation of the genotoxicity and mutagenicity of isoeleutherin and eleutherin isolated from Eleutherine plicata herb. using bioassays and in silico approaches. Arab. J. Chem. 2021;14:103084. doi: 10.1016/j.arabjc.2021.103084. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cheung J., Gary E.N., Shiomi K., Rosenberry T.L. Structures of human acetylcholinesterase bound to dihydrotanshinone i and territrem B show peripheral site flexibility. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2013;4:1091–1096. doi: 10.1021/ml400304w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Liao Z., Huang Q., Cheng Q., Khan S., Yu X. Seasonal variation in chemical compositions of essential oils extracted from lavandin flowers in the yun-gui plateau of china. Molecules. 2021;26:5639. doi: 10.3390/molecules26185639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cantor M., Vlas N., Szekely Z., Jucan D., Zaharia A. The influence of distillation time and the flowering phenophase on quantity and quality of the essential oil of Lavandula angustifolia cv. ‘Codreanca.’ Rom. Biotechnol. Lett. 2018;23:14146–14152. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Méndez-Tovar I., Novak J., Sponza S., Herrero B., Asensio-S-Manzanera M.C. Variability in essential oil composition of wild populations of Labiatae species collected in Spain. Ind. Crops Prod. 2016;79:18–28. doi: 10.1016/j.indcrop.2015.10.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nazar E.D., Peixoto L.D.S., Costa J.S., Helena R., Mour V., Maria W., Nascimento O., Maia G.S., Setzer W.N., Kelly J., et al. Seasonal Variability of a Caryophyllane Chemotype Essential Oil of Eugenia patrisii Vahl Occurring in the Brazilian Amazon. Molecules. 2022;27:2417. doi: 10.3390/molecules27082417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jing C.L., Huang R.H., Su Y., Li Y.Q., Zhang C.S. Variation in chemical composition and biological activities of flos chrysanthemi indici essential oil under different extraction methods. Biomolecules. 2019;9:518. doi: 10.3390/biom9100518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.De Souza Araújo C., De Oliveira A.P., Lima R.N., Alves P.B., Diniz T.C., Da Silva Almeida J.R.G. Chemical constituents and antioxidant activity of the essential oil from leaves of Annona vepretorum Mart. (Annonaceae) Pharmacogn. Mag. 2015;11:615–618. doi: 10.4103/0973-1296.160462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Meira C.S., Guimarães E.T., MacEdo T.S., Da Silva T.B., Menezes L.R.A., Costa E.V., Soares M.B.P. Chemical composition of essential oils from Annona vepretorum Mart. and Annona squamosa L. (Annonaceae) leaves and their antimalarial and trypanocidal activities. J. Essent. Oil Res. 2015;27:160–168. doi: 10.1080/10412905.2014.982876. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ribeiro L.P., Domingues V.C., Gonçalves G.L.P., Fernandes J.B., Glória E.M., Vendramim J.D. Essential oil from Duguetia lanceolata St.-Hil. (Annonaceae): Suppression of spoilers of stored-grain. Food Biosci. 2020;36:100653. doi: 10.1016/j.fbio.2020.100653. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.do Nascimento K.F., Moreira F.M.F., Alencar Santos J., Kassuya C.A.L., Croda J.H.R., Cardoso C.A.L., Vieira M.d.C., Góis Ruiz A.L.T., Ann Foglio M., de Carvalho J.E., et al. Antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, antiproliferative and antimycobacterial activities of the essential oil of Psidium guineense Sw. and spathulenol. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2018;210:351–358. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2017.08.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Karakaya S., Yilmaz S.V., Özdemir Ö., Koca M., Pınar N.M., Demirci B., Yıldırım K., Sytar O., Turkez H., Baser K.H.C. A caryophyllene oxide and other potential anticholinesterase and anticancer agent in Salvia verticillata subsp. amasiaca (Freyn & Bornm.) Bornm. (Lamiaceae) J. Essent. Oil Res. 2020;32:512–525. doi: 10.1080/10412905.2020.1813212. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Caesar L.K., Cech N.B. Synergy and antagonism in natural product extracts: When 1 + 1 does not equal 2. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2019;36:869–888. doi: 10.1039/C9NP00011A. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rao M.J., Wu S., Duan M., Wang L. Antioxidant metabolites in primitive, wild, and cultivated citrus and their role in stress tolerance. Molecules. 2021;26:5801. doi: 10.3390/molecules26195801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bezerra J.W.A., Costa A.R., da Silva M.A.P., Rocha M.I., Boligon A.A., da Rocha J.B.T., Barros L.M., Kamdem J.P. Chemical composition and toxicological evaluation of Hyptis suaveolens (L.) Poiteau (LAMIACEAE) in Drosophila melanogaster and Artemia salina. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2017;113:437–442. doi: 10.1016/j.sajb.2017.10.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Braguini W.L., Alves B.B., Pires N.V. Toxicity assessment of Lavandula officinalis extracts in Brine Shrimp (Artemia salina) Toxicol. Mech. Methods. 2019;29:411–420. doi: 10.1080/15376516.2019.1567892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ramos S.C.S., De Oliveira J.C.S., Da Câmara C.A.G., Castelar I., Carvalho A.F.F.U., Lima-Filho J.V. Antibacterial and cytotoxic properties of some plant crude extracts used in Northeastern folk medicine. Rev. Bras. Farmacogn. 2009;19:376–381. doi: 10.1590/S0102-695X2009000300007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Mirzaei H.H., Firuzi O., Baldwin I.T., Jassbi A.R. Cytotoxic activities of different iranian solanaceae and lamiaceae plants and bioassay-guided study of an active extract from salvia lachnocalyx. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2017;12:1563–1566. doi: 10.1177/1934578X1701201009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Fidyt K., Fiedorowicz A., Strządała L., Szumny A. Β-Caryophyllene and Β-Caryophyllene Oxide—Natural Compounds of Anticancer and Analgesic Properties. Cancer Med. 2016;5:3007–3017. doi: 10.1002/cam4.816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Fraternale D., Ricci D., Calcabrini C., Guescini M., Martinelli C., Sestili P. Cytotoxic activity of essential oils of aerial parts and ripe fruits of echinophora spinosa (apiaceae) Nat. Prod. Commun. 2013;8:1645–1649. doi: 10.1177/1934578X1300801137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Aydin E., Türkez H., Taşdemir Ş. Anticancer and antioxidant properties of terpinolene in rat brain cells. Arh. Hig. Rada Toksikol. 2013;64:415–424. doi: 10.2478/10004-1254-64-2013-2365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Salehi B., Upadhyay S., Orhan I.E., Jugran A.K., Baghalpour N., Cho W.C., Sharifi-rad J. Therapeutic Potential of α- and β-Pinene_A Miracle Gift of Nature. Biomolecules. 2019;9:738. doi: 10.3390/biom9110738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Grecco S.D.S., Martins E.G.A., Girola N., De Figueiredo C.R., Matsuo A.L., Soares M.G., Bertoldo B.D.C., Sartorelli P., Lago J.H.G. Chemical composition and in vitro cytotoxic effects of the essential oil from Nectandra leucantha leaves. Pharm. Biol. 2015;53:133–137. doi: 10.3109/13880209.2014.912238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Soares B.V., Morais S.M., Dos Santos Fontenelle R.O., Queiroz V.A., Vila-Nova N.S., Pereira C.M.C., Brito E.S., Neto M.A.S., Brito E.H.S., Cavalcante C.S.P., et al. Antifungal activity, toxicity and chemical composition of the essential oil of coriandrum sativum L. Fruits. Molecules. 2012;17:8439–8448. doi: 10.3390/molecules17078439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Oliva M.D.L.M., Gallucci N., Zygadlo J.A., Demo M.S. Cytotoxic activity of Argentinean essential oils on Artemia salina. Pharm. Biol. 2007;45:259–262. doi: 10.1080/13880200701214557. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Sharififar F., Assadipour A., Moshafi M. Bioassay Screening of the Essential Oil and Various Extracts of Nigella sativa L. Seeds Using Brine Shrimp Toxicity Assay. Herb. Med. 2017;2:1–6. doi: 10.22087/HMJ.V1I2.578. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Do Nascimento J.C., David J.M., Barbosa L.C., De Paula V.F., Demuner A.J., David J.P., Conserva L.M., Ferreira J.C., Guimarães E.F. Larvicidal activities and chemical composition of essential oils from Piper klotzschianum (Kunth) C. DC. (Piperaceae) Pest Manag. Sci. 2013;69:1267–1271. doi: 10.1002/ps.3495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Sousa O.V., Del-Vechio-Vieira G., Alves M.S., Araújo A.A.L., Pinto M.A.O., Amaral M.P.H., Rodarte M.P., Kaplan M.A.C. Chemical composition and biological activities of the essential oils from Duguetia lanceolata St. Hil. barks. Molecules. 2012;17:11056–11066. doi: 10.3390/molecules170911056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Galucio N.C.d.R., Moysés D.d.A., Pina J.R.S., Marinho P.S.B., Gomes Júnior P.C., Cruz J.N., Vale V.V., Khayat A.S., Marinho A.M.d.R. Antiproliferative, genotoxic activities and quantification of extracts and cucurbitacin B obtained from Luffa operculata (L.) Cogn. Arab. J. Chem. 2022;15:103589. doi: 10.1016/j.arabjc.2021.103589. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Rego C.M.A., Francisco A.F., Boeno C.N., Paloschi M.V., Lopes J.A., Silva M.D.S., Santana H.M., Serrath S.N., Rodrigues J.E., Lemos C.T.L., et al. Inflammasome NLRP3 activation induced by Convulxin, a C-type lectin-like isolated from Crotalus durissus terrificus snake venom. Sci. Rep. 2022;12:4706. doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-08735-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Costa E.B.B., Silva R.C.C., Espejo-Román J.M.M., Neto M.F.d.A.F.d.A., Cruz J.N.N., Leite F.H.A.H.A., Silva C.H.T.P.H.T.P., Pinheiro J.C.C., Macêdo W.J.C.J.C., Santos C.B.R.B.R. Chemometric methods in antimalarial drug design from 1,2,4,5-tetraoxanes analogues. SAR QSAR Environ. Res. 2020;31:677–695. doi: 10.1080/1062936X.2020.1803961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Neto R.d.A.M.M., Santos C.B.R.R., Henriques S.V.C.C., Machado L.d.O., Cruz J.N., da Silva C.H.T.d.P.T.d.P., Federico L.B., Oliveira E.H.C.d.C.d., de Souza M.P.C.C., da Silva P.N.B.B., et al. Novel chalcones derivatives with potential antineoplastic activity investigated by docking and molecular dynamics simulations. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2020;40:2204–2216. doi: 10.1080/07391102.2020.1839562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.da Silva Júnior O.S., Franco C.d.J.P., de Moraes A.A.B., Cruz J.N., da Costa K.S., do Nascimento L.D., Andrade E.H.d.A. In silico analyses of toxicity of the major constituents of essential oils from two Ipomoea L. species. Toxicon. 2021;195:111–118. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2021.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Baek I., Choi H.J., Rhee J.S. Inhibitory effects of biocides on hatching and acetylcholinesterase activity in the brine shrimp Artemia salina. Toxicol. Environ. Health Sci. 2015;7:303–308. doi: 10.1007/s13530-015-0253-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data are contained within the article and supplementary materials.