Abstract

A gene, mokA, encoding a protein with similarities to histidine kinase-response regulator hybrid sensor, was cloned from a Myxococcus xanthus genomic library. The predicted mokA gene product was found to contain three domains: an amino-terminal input domain, a central transmitter domain, and a carboxy-terminal receiver domain. mokA mutants placed under starvation conditions exhibited reduced sporulation. Mutation of mokA also caused marked growth retardation at high osmolarity. These results indicated that M. xanthus MokA is likely a transmembrane sensor that is required for development and osmotic tolerance. The putative function of MokA is similar to that of the hybrid histidine kinase, DokA, of the eukaryotic slime mold Dictyostelium discoideum.

Myxococcus xanthus is a gram-negative soil bacterium that demonstrates complex social behavior (5, 31). Upon nutritional starvation, cells undergo a developmental cycle involving cell-cell interactions. More than 105 cells migrate to an aggregation center and form a fruiting body, within which cells differentiate into myxospores.

M. xanthus cells coordinate their multicellular behavior through cell-cell communication by transmission of intercellular signals. The transmission of intercellular signals in M. xanthus has been studied by isolating development-defective mutants, dividing them into five groups (A to E), and conducting pairwise mixing tests of the different groups (4, 19, 20, 21). These intercellular signals control the expression of developmentally regulated genes. M. xanthus possesses a complex signal transduction system: two-component system (sensor histidine kinases and response regulators), serine/threonine and tyrosine kinases, and small GTPase (8, 11, 38). In bacteria, the most common protein kinases involved in signal transduction are histidine kinases. Thus far, AsgA, EspA, FrzE, and SasS in M. xanthus have been identified as histidine kinases (3, 23, 29, 34). Inouye and colleagues have identified a large family of serine/threonine kinase genes in M. xanthus and performed several studies of the functions of the encoded protein serine/threonine kinases (15, 24, 37, 38).

On the other hand, hybrid sensors containing both a histidine kinase domain and a receiver domain within the same molecule have also been detected recently in eukaryotic cells (18). These hybrid sensors play regulatory roles in eukaryotic cell function. For example, the predicted product of ETR1 in Arabidopsis thaliana and SLN1 in Saccharomyces cerevisiae are involved in regulating the ethylene and osmotic responses, respectively (12, 27). Here, we report the molecular cloning of a gene in M. xanthus encoding a protein homologous to members of the hybrid sensor family. Furthermore, its possible physiological functions were clarified.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains, plasmids, and growth conditions.

The type strain of M. xanthus, IFO13542 (ATCC 25232), was used as the wild type. M. xanthus strains were grown at 28°C in Casitone-yeast extract (CYE) medium (2), and kanamycin (70 μg/ml) was added when necessary. The plasmids pBluescript II SK(−) (Stratagene, La Jolla, Calif.) and pT7-blue T (Novagen, Madison, Wis.) were used for cloning. Plasmids were propagated in Escherichia coli NovaBlue (Novagen).

DNA manipulations.

The genomic DNA of M. xanthus was partially digested with Sau3AI and then ligated into BamHI-cleaved λ EMBL3 arms. A portion (1 μg) of the recombinant DNA was packaged into bacteriophage λ particles in vitro, using a commercial kit (Stratagene).

For detection of histidine kinases of M. xanthus, two oligonucleotides (Oli-1 and Oli-2) were synthesized. Oli-1 (5′-GACACXGGXATCGGXATC-3′) and Oli-2 (5′-GGXACXGGXCTXGGXCTXTC-3′) (X can be either C or G) were deduced from the conserved regions of the glycine-rich sequences of histidine kinase domains. The oligonucleotides were labeled with digoxigenin-11-dUTP using an oligonucleotide tailing kit (Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Mannheim, Germany). The M. xanthus genomic DNA library was screened by plaque hybridization with a mixture of probes Oli-1 and Oli-2. Three clones that hybridized to the probes were selected. Recombinant phage DNAs were isolated from these three clones, designated as pHK1, pHK2 and pHK3, and digested with PstI, SalI, and SmaI. The fragments were electrophoretically separated on agarose gels, transferred onto nylon membranes, and then hybridized with the probes. Hybridization to PstI-, SalI- and SmaI-digested pHK1 revealed strong bands (12, 7.0, and 2.5 kb, respectively). The hybridizing PstI, SalI, and SmaI fragments were ligated into pBluescript II SK, to generate pHK1-P, pHK1-Sa, and pHK1-Sm, respectively. The recombinant plasmids were sequenced using synthetic oligonucleotides. pHK1-Sm was also used for construction of the mokA mutant.

Construction of the mokA disruption mutant.

Plasmid pHK1-Sm, which contains the mokA gene on a 2.5-kb SmaI fragment, was digested with NcoI, and the ends were blunted with T4 DNA polymerase (Fig. 1). A 1.2-kb DNA fragment containing a kanamycin resistance (Kmr) gene was amplified by PCR using TnV as a template and a pair of primers, 5′-GTGCTGACCCCGGGTGAATGTCAG-3′ and 5′-ATCGAGCCCGGGGTGGGCGAAGAA-3′, containing SmaI sites (9). The resulting DNA fragment was digested with SmaI and inserted into the blunted ends of pHK1-Sm. The disrupted gene constructed as described above was amplified by PCR using the oligonucleotide 5′-CTGGAGATTCGCTTCACG-3′ for the 5′ end of the 2.5-kb SmaI fragment of pHK1-Sm and 5′-GACGTGAAGGGACTGCTG-3′ for the 3′ end of the 2.5-kb SmaI fragment of pHK1-Sm. The PCR products thus obtained were introduced into M. xanthus by electroporation.

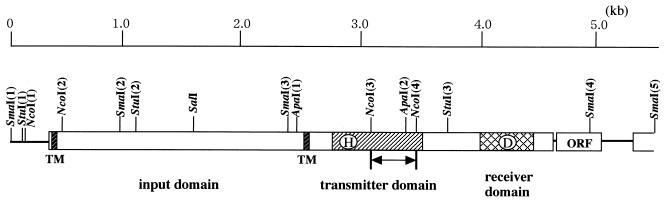

FIG. 1.

Restriction map and gene structure of mokA. The NcoI fragment replaced by a Kmr gene is indicated by an arrow. TM, transmembrane domain.

Developmental assays.

To obtain fruiting bodies, M. xanthus wild-type and mutant strains were grown in CYE medium. The cells were harvested at late log phase, washed with 10 mM Tris-HCl–8 mM MgSO4, pH 7.6 (TM buffer), and resuspended in TM buffer to a density of 2 × 109 cells/ml. The cells were spotted onto CF agar plates (10) at 150 μl of cells per plate, and the plates were incubated at 30°C. Fruiting bodies were harvested at various times by gentle scraping of the surface of agar plates and suspended in cold TM buffer.

For glycerol induction of spore formation, cells were grown vegetatively in CYE medium. The cells were harvested and washed with 1% Casitone–8 mM MgSO4. Glycerol was added to a final concentration of 0.5 M, and cells were shaken at 30°C for 10 h (6).

For each of the above assays, undifferentiated cells were killed by incubation at 60°C for 15 min and by five 30-s treatments with a Branson sonifier. Spores were counted using a Petroff-Hausser counter. The viability of spores was also confirmed on CYE agar plates.

Osmotic stress experiments.

M. xanthus wild-type and mutant strains were grown in CYE medium, and cells were harvested at a density of 8 × 108 cells/ml. Then aliquots of 9 × 106 cells were inoculated into 3 ml of CYE medium containing up to 0.25 M NaCl or 0.2 M sucrose. The cultures were incubated in suspension until the culture without NaCl or sucrose attained a density of about 109 cells/ml. Growth of each strain was determined by counting with a hemacytometer.

Transcript analysis.

Total RNA was isolated from M. xanthus at exponential growth phase, stationary phase, and during development. For reverse transcriptase PCR (RT-PCR), 1 μg of RNA was used for cDNA synthesis with BcaBEST polymerase as specified by the manufacturer (Takara Shuzo, Kyoto, Japan). PCR was performed with Bca-optimized Taq polymerase, 5′ gene-specific primer (5′-GCACGTCGCTCTGGGTGG-3′), and 3′ gene-specific primer (5′-CGCATCAGGCCCGAATAG-3′). Amplification products were visualized in agarose gels after ethidium bromide staining and were recorded by a LAS-1000 system (Fuji Film, Tokyo, Japan).

RESULTS

Cloning and sequencing of mokA.

Transient protein phosphorylation is a critical component of many signal transduction systems. To search for histidine kinase genes in M. xanthus, we designed oligonucleotides on the basis of the conserved sequences of histidine kinase domain and attempted to clone the histidine kinase genes from an M. xanthus genomic library by using the oligonucleotide probes. One clone that hybridized strongly to the probes was selected and used for subcloning. A 2.5-kb SmaI fragment of the clone was hybridized with the probes and used for sequence analysis. The predicted amino acid sequence of this fragment revealed the presence of a putative histidine kinase domain. The nucleotide sequence of the 5.5-kb SmaI(1)-SmaI(5) fragment of the clone that contained the complete transcription unit was determined (Fig. 1). The complete transcription unit, predicted by the Codon-Preference program based on the G-C codon bias of the third position in this high-G+C-content organism, was predicted to start at nucleotide 418 and to stop at nucleotide 4572 (14). The entire sequence of the fragment is shown in Fig. 2; the gene was designated mokA (M. xanthus osmosensing kinase A) because of its phenotype, which is described below. Analysis of this sequence predicted a coding region that encompasses 1,414 amino acids resulting in a putative protein with an Mr of 153,000.

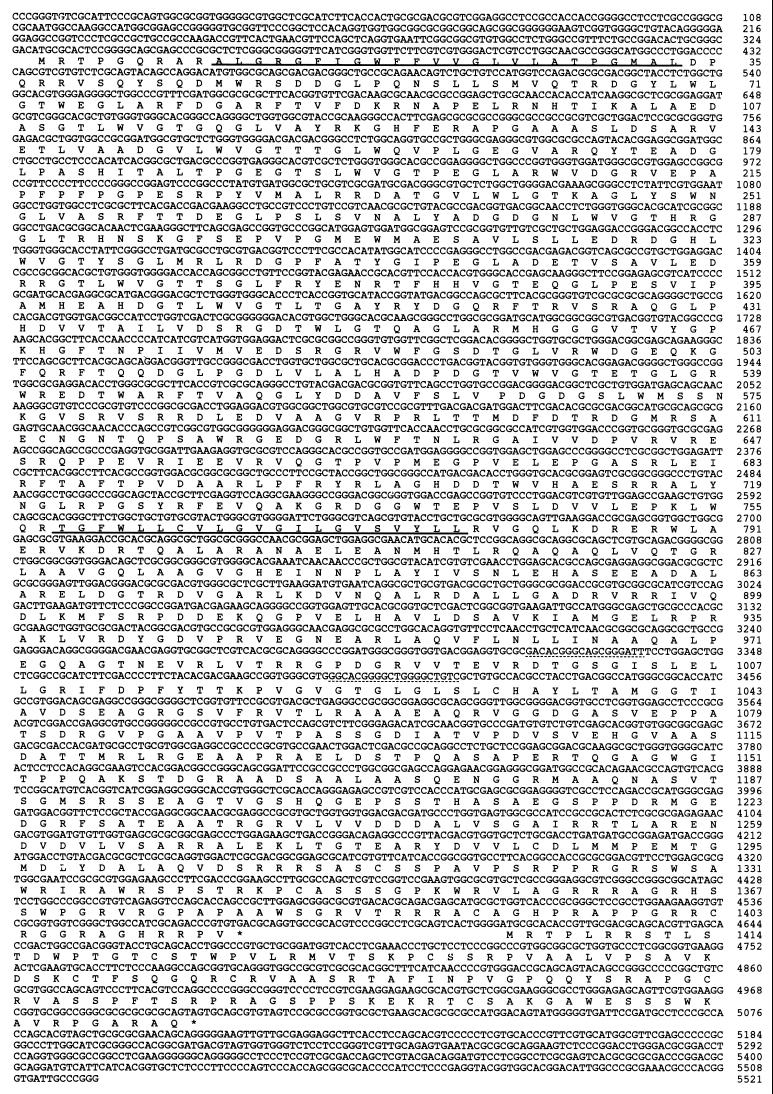

FIG. 2.

Nucleotide and deduced amino acid sequences of the region of the M. xanthus chromosome containing the mokA gene. The sequences corresponding to probes are indicated by dotted lines. Probable transmembrane domains of MokA are indicated by solid lines.

An open reading frame (ORF) consisting of 384 bp was located 39 nucleotides downstream of the mokA stop codon. However, the predicted ORF gene product showed no extensive homology with response regulators or other proteins in the GenBank database.

Predicted protein structure and functional domains.

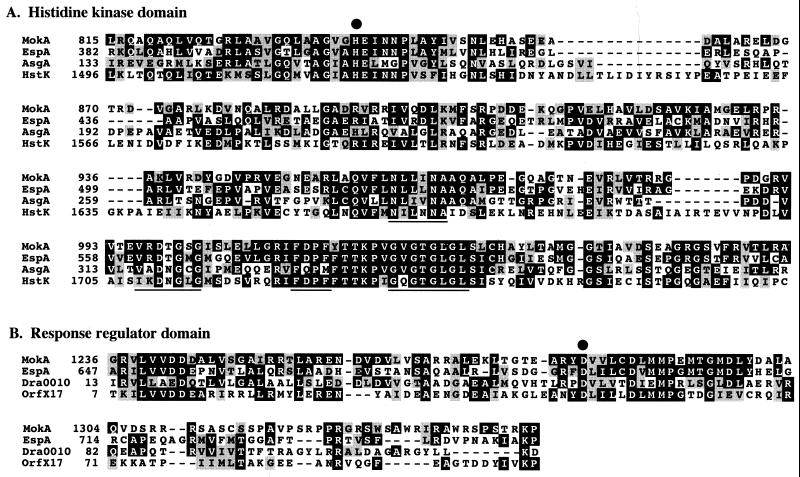

To gain insight into possible functions of the mokA gene product, a homology search of the MokA amino acid sequence in the protein database was performed. The MokA product showed sequence similarity throughout the entire molecule except the amino-terminal region with histidine protein kinase EspA of M. xanthus (44% identity) (3), putative sensory transduction histidine kinase Slr2098 of Synechocystis sp. strain PCC6803 (29% identity) (17), and osmosensing histidine kinase DokA of Dictyostelium discoideum (27% identity) (30). Based on sequence homology, the carboxy-terminal part of the MokA protein consisted of two domains: the histidine kinase and response regulator domains of bacterial two-component systems. The histidine kinase domain of MokA (positions 815 to 1061) was most similar to those of histidine kinases EspA and AsgA of M. xanthus (50 and 37% identities, respectively) (3, 29) and histidine kinase HstK of Anabaena sp. strain PCC 7120 (33% identity) (V. Phalip, G. Brandner, and C.-C. Zhang. unpublished data) (Fig. 3A). The MokA histidine kinase domain contained all of the residues conserved among bacterial histidine kinases, including the putative phosphoryl group acceptor His-840. The MokA histidine kinase domain also contained the conserved ATP-binding regions, NXXXNX25–38DXGXGX9FXPFX6–14GXGLGL, that are highly conserved in all histidine protein kinases (28) (Fig. 3A).

FIG. 3.

(A) Alignment of the deduced histidine protein kinase domain of MokA with the histidine protein kinase domains of EspA and AsgA from M. xanthus and HstK from Anabaena sp. strain PCC 7120. Nucleotide-binding domains are underlined; the dot represents the position of the putative autophosphorylated histidine residue. (B) Response regulator domains of EspA and MokA from M. xanthus, Dra0010 from D. radiodurans, and OrfX17 from B. subtilis, aligned on a conserved sequence of 110 amino acids. The dot indicates the putative phosphorylated aspartic acid residue.

The regulator domain of MokA (positions 1236 to 1345) was most similar to those of the histidine protein kinase EspA of M. xanthus (32% identity) (3), putative regulator protein OrfX17 of Bacillus subtilis (29% identity) (32), and putative DNA-binding regulator protein Dra0010 of Deinococcus radiodurans (27% identity) (36) (Fig. 3B). The three residues (Asp-1243, Asp-1287, and Lys-1344) that are conserved in all of the response regulators were also present in MokA. Sequence comparisons with MokA and other regulators suggested that Asp-1287 is a site of phosphorylation.

The amino-terminal half of the MokA protein (positions 1 to 800) showed no significant similarities to domains found in other histidine protein kinases. Analysis of the mokA gene product using the Kyte-Doolittle algorithm (22) suggested that MokA possesses two potential transmembrane regions (amino acids 10 to 33 and 758 to 778) in its amino-terminal half, which would place the protein in the cytoplasmic membrane (Fig. 2).

Distribution of mokA on development.

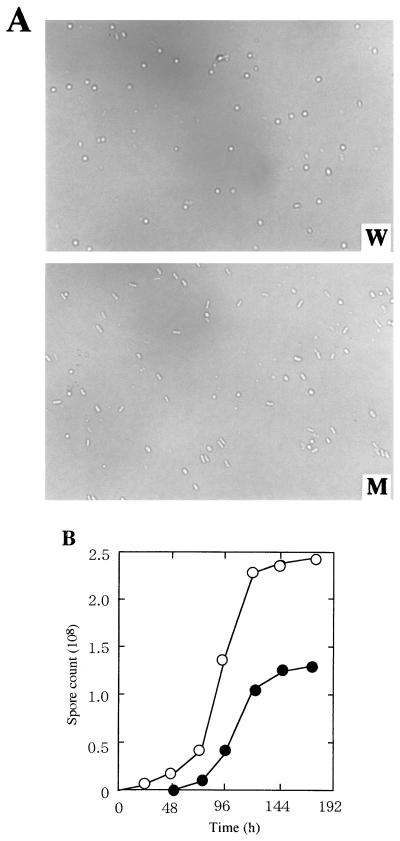

To study the function of MokA, we constructed a mokA insertion-deletion mutant. The 0.3-kb NcoI(3)-NcoI(4) fragment containing the conserved ATP-binding regions of histidine kinase domains was replaced by a 1.2-kb fragment containing the Kmr gene. Replacement of the wild-type mokA gene by the defective gene was confirmed by Southern hybridization and PCR analyses. When cultured in growth medium, CYE, the mutant grew as well as the wild type. Under these conditions, the two strains were morphologically identical. However, on the developmental medium, CF agar, clear differences were observed between the two strains. The wild-type cells moved to aggregation centers within 32 h and then formed spherical fruiting bodies by 48 to 72 h on CF agar. Within the fruiting bodies of the wild type, rod-shaped vegetative cells were converted to spherical myxospores (Fig. 4A). The mutant cells formed fruiting bodies about 1 day later than the wild-type strain, and unmature spores were observed within fruiting bodies (Fig. 4A). As a result, the spore yield of the mutant strain was approximately 50% of that of the wild-type strain (Fig. 4B). The spores formed in the disruption mutant were able to germinate like the wild-type myxospores. When induced by 0.5 M glycerol, the mutant cells sporulated at the same rate as wild-type cells (data not shown).

FIG. 4.

Spore formation of M. xanthus wild-type and mokA mutant strains. The cells were developed on CF agar, and undifferentiated cells were killed by sonication and heating as described in Materials and Methods. (A) Photographs of wild-type (W) and mutant (M) spores taken 7 days after the start of development. (B) Numbers of spores from wild-type (open circles) and mutant (closed circles) strains plotted relative to the time of the development after spotting.

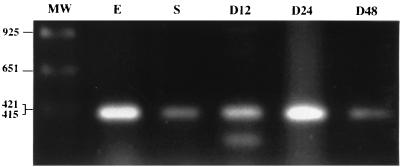

The timing and level of expression of the mokA gene were determined by RT-PCR analysis (Fig. 5). The expected 421-bp RT-PCR product was amplified from mRNA of vegetative cells. The RT-PCR products declined during the early stage of development and then reached their maximum after 24 h, when some mounds were formed in the culture. As a control, the expected product was not amplified without a reverse transcriptase, indicating that there was no DNA contamination in the mRNA (data not shown).

FIG. 5.

RT-PCR analysis of expression of the mokA gene in M. xanthus. Total RNAs prepared from cultures at exponential growth (E) and stationary (S) phases and during development at 12 h (D12), 24 h (D24), and 48 h (D48) were used for RT-PCR analysis. Molecular sizes of DNA fragments are given in bases. MW, molecular weight marker.

mokA mutants are osmosensitive.

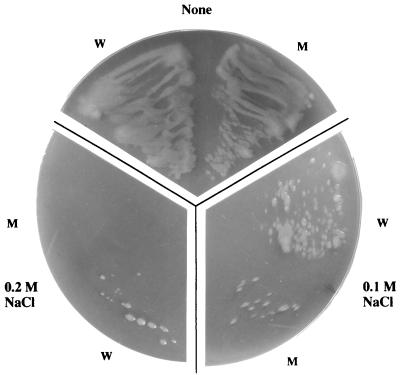

Since MokA is structurally similar to osmotic response proteins of Neurospora crassa Nik1 (1), S. cerevisiae Sln1 (27), and D. discoideum DokA (30), the wild-type and mokA mutant strains of M. xanthus were cultivated under osmotic stress and examined for osmotic tolerance (Fig. 6). The wild-type strain grew on CYE agar containing up to 0.2 M NaCl, while the mutant showed sparse growth and no growth on CYE medium containing 0.1 and 0.2 M NaCl, respectively.

FIG. 6.

Comparison of wild-type (W) and mokA mutant (M) cells grown on CYE agar containing no addition, 0.1 M NaCl, and 0.2 M NaCl. The cells were streaked onto the plates and incubated at 30°C for 3 days.

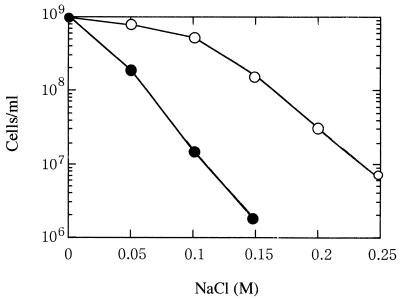

We also monitored the growth response of the mutant in shaking liquid culture. In the presence of 0.1 M NaCl in CYE medium, mutant cells showed nearly a 30-fold decrease in growth compared with wild-type cells (Fig. 7). The mutant also showed a similar decrease in ability to grow in the presence of 0.03 to 0.1 M sucrose (data not shown). The mutant was found to be reasonably normal with respect to stresses such as temperature shifts, pH changes, various antibiotics, and ethanol (data not shown).

FIG. 7.

Growth of M. xanthus wild-type (open circles) and mokA mutant (closed circles) strains in CYE medium containing various concentrations of NaCl. Cultures were inoculated to 3 × 106 cells/ml. Growth of each strain was determined by counting in a hemacytometer.

DISCUSSION

Bacteria have the ability to sense a variety of environmental changes and respond appropriately. The environmental changes are transmitted into the cell by signal-transducing proteins. Two-component signal transduction systems are among the strategies that bacteria employ to sensor and respond to the environmental changes. The prototypical two-component system consists of two proteins, a sensor histidine kinase and a response regulator. A variety of forms of hybrid sensors containing both transmitter and receiver modules in their primary amino acid sequences have been found in prokaryotic and eukaryotic organisms. In addition, serine/threonine and tyrosine kinases have been found in several differential bacteria (18). In M. xanthus, serine/threonine kinases (Pkn1, Pkn2, Pkn5, and Pkn6) were found to regulate fruiting-body formation and to affect sporulation (35, 37).

In this study, we isolated and sequenced an M. xanthus mokA gene which encodes a member of the hybrid histidine kinase family. The amino-terminal domain of the mokA product did not display any significant homology to other proteins, while the protein is predicted to contain two transmembrane regions in the amino-terminal domain. In general, the hydrophobic domains are each predicted to cross the cytoplasmic membrane, and the hydrophilic region is predicted to be a periplasmic input domain. The carboxy-terminal domain of MokA contained both transmitter and receiver modules. The structural characteristics of MokA are similar to those of E. coli RcsC (33), N. crassa Nik1 (1), yeast CaSln1 (25) and Sln1 (27), and D. discoideum DokA (30). The hybrid sensors Nik1, CaSln1, Sln1, and DokA of eukaryotes act as osmosensor proteins. The mutation of M. xanthus mokA caused a remarkable reduction in the growth of cells at high osmolarity (0.1 to 0.2 M NaCl or 0.1 M sucrose). The mutant responded normally against other stresses. These data indicate that MokA acts as an osmosensor protein in M. xanthus. With repetitive subculture in CYE medium, some mokA mutants gained osmotic tolerance (data not shown). These observations imply that M. xanthus harbors other genes (possibly encoding sensor kinases) that compensate for mokA gene dysfunction to adapt to high osmolarity. In E. coli, hybrid sensors ArcB and BarA can complement a defect in the osmotic signal transduction caused by an osmotic sensory kinase (envZ) mutation (13, 26).

The histidine kinases AsgA, EspA, FrzE, and SasS of M. xanthus were found to regulate fruiting-body formation (3, 23, 29, 34). AsgA is an unusual member of the hybrid histidine kinase family in that it has a receiver domain in the amino terminus and a kinase domain in the carboxy terminus and does not contain an input domain. AsgA is essential for fruiting-body formation and is thought to interact with other signaling proteins that have input functions (29). SasS is predicted to be the sensor protein in a two-component system that integrates information required for early developmental gene expression (34). In contrast, the hybrid histidine kinase, EspA, is thought to function as an inhibitor of sporulation during early development (3). The results of this study, indicated that MokA also participates in M. xanthus development. The mokA mutant cells developed more slowly than the wild-type strain and formed many unusual spores under starvation conditions. After 7 days of development, the mutant formed half as many spores as the wild-type strain. These observations suggest that MokA is required for M. xanthus development but that development can be achieved by cross talk among sensor and regulator proteins, compensating for the absence of MokA. On the other hand, mutant cells deficient in osmotic tolerance may be unable to form normal spores completely.

We constructed another insertion mutant in which the Kmr gene was inserted into the StuI(3) site of mokA (Fig. 1) between the transmitter and receiver domains of MokA. The insertion mutant behaved in the same way as the mokA insertion-deletion mutant, indicating that the receiver domain may be required for the normal function of MokA. One ORF that could be part of an operon with mokA was present downstream of mokA. The ORF is the last gene of the operon and encoded 128 amino acids. Its amino acid sequence showed no homology with response regulators or other proteins. These data indicate that the phenotype of insertion mutants would not be due to polar effects on the transcription of downstream genes.

The eukaryotic slime mold D. discoideum has a developmental cycle that resembles that of M. xanthus (16). The development of D. discoideum is regulated by a signal transduction system consisting of protein serine/threonine kinases, G proteins, and cyclic AMP signaling (7). DokA of D. discoideum is part of the osmotic response system and also play key roles in fruiting-body formation. In N. crassa, the hybrid sensor Nik1 is required for the ability of cells to grow under conditions of high osmotic stress and for hyphal development. The observation that mokA mutants are deficient in normal development and osmotic tolerance demonstrated that MokA may have functions similar to those of hybrid sensors (DokA and Nik1) of eukaryotic microorganisms. We are currently attempting to detect other components of the signal transduction pathway involving MokA.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alex L A, Borkovich K A, Simon M I. Hyphal development in Neurospora crassa: involvement of a two-component histidine kinase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:3416–3421. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.8.3416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Campos M J, Geisselesoder J, Zusman R D. Isolation of bacteriophage MX4, a generalized transducing phage for Myxococcus xanthus. J Mol Biol. 1978;119:167–178. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(78)90431-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cho K, Zusman D R. Sporulation timing in Myxococcus xanthus is controlled by the espAB locus. Mol Microbiol. 1999;34:714–725. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01633.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Downard J, Toal D. Branched-chain fatty acids—the case for a novel form of cell-cell signaling during Myxococcus xanthus development. Mol Microbiol. 1995;16:171–175. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.tb02290.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dworkin M, Kaiser D. Cell interactions in myxobacterial growth and development. Science. 1985;230:18–24. doi: 10.1126/science.3929384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dworkin M, Gibson S M. A system for studying microbial morphogenesis: rapid formation of microcysts in Myxococcus xanthus. Science. 1964;146:243–244. doi: 10.1126/science.146.3641.243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Firtel R A. Integration of signaling information in controlling cell-fate decisions in Dictyostelium. Genes Dev. 1995;9:1427–1444. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.12.1427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Frasch S C, Dworkin M. Tyrosine phosphorylation in Myxococcus xanthus, a multicellular prokaryote. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:4084–4088. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.14.4084-4088.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Furuichi T, Inouye M, Inouye S. Novel one-step cloning vector with a transposable element: application to the Myxococcus xanthus genome. J Bacteriol. 1985;164:270–275. doi: 10.1128/jb.164.1.270-275.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hagen C D, Bretscher P A, Kaiser D. Synergism between morphogenic mutants of Myxococcus xanthus. Dev Biol. 1979;64:284–296. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(78)90079-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hartzell P L. Complementation of sporulation and motility defects in a prokaryote by a eukaryotic GTPase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:9881–9886. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.18.9881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hua J, Chang C, Sun Q, Meyerowitz E M. Ethylene insensitivity conferred by Arabidopsis ERS gene. Science. 1995;269:1712–1714. doi: 10.1126/science.7569898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ishige K, Nagasawa S, Tokishita S, Mizuno T. A novel device of bacterial signal transducers. EMBO J. 1994;13:5195–5202. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06850.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ishikawa J, Hotta K. Frame plot: a new implementation of the frame analysis for predicting protein-coding regions in bacterial DNA with a high G+C content. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1999;174:251–253. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1999.tb13576.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jain R, Inouye S. Inhibition of development of Myxococcus xanthus by eukaryotic protein kinase inhibitors. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:6544–6550. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.24.6544-6550.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kaiser D. Control of multicellular development: Dictyostelium and Myxococcus. Annu Rev Genet. 1986;20:539–566. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ge.20.120186.002543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kaneko T, Sato S, Kotani H, Tanaka A, Asamizu E, Nakamura Y, Miyajima N, Hirosawa M, Sugiura M, Sasamoto S, Kimura T, Hosouchi T, Matsuno A, Muraki A, Nakazaki N, Naruo K, Okumura S, Shimpo S, Takuechi C, Wada T, Watanabe A, Yamada M, Yasuda M, Tabata S. Sequence analysis of the genome of the unicellular cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. PCC6803. II. Sequence determination of the entire genome and assignment of potential protein-coding regions. DNA Res. 1996;3:109–136. doi: 10.1093/dnares/3.3.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kennelly P J, Potts M. Fancy meeting you here! A fresh look at “prokaryotic” protein phosphorylation. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:4759–4764. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.16.4759-4764.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim S K, Kaiser D. C-factor: a cell-cell signaling protein required for fruiting body morphogenesis of M. xanthus. Cell. 1990;61:19–26. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90211-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim S K, Kaiser D. Cell motility is required for the transmission of C-factor, an intercellular signal that coordinates fruiting body morphogenesis of Myxococcus xanthus. Genes Dev. 1990;4:896–905. doi: 10.1101/gad.4.6.896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kuspa A, Kaiser D. Genes required for developmental signaling in Myxococcus xanthus: three asg loci. J Bacteriol. 1989;171:2762–2772. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.5.2762-2772.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kyte J, Doolittle R F. A simple method for displaying the hydropathic character of a protein. J Mol Biol. 1982;157:105–132. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(82)90515-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McCleary W R, Zusman D R. FrzE of Myxococcus xanthus is homologous to both CheA and CheY of Salmonella typhimurium. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:5898–58902. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.15.5898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Munoz-Dorado J, Inouye S, Inouye M. A gene encoding a protein serine/threonine kinase is required for normal development of M. xanthus, a gram-negative bacterium. Cell. 1991;67:995–1006. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90372-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nagahashi S, Mio T, Ono N, Yamada-Okabe T, Arisawa M, Bussey H, Yamada-Okabe H. Isolation of CaSLN1 and CaNIK1, the genes for osmosensing histidine kinase homologous, from the pathogenic fungus Candida albicans. Microbiology. 1998;144:425–432. doi: 10.1099/00221287-144-2-425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nagasawa S, Tokishita S, Aiba H, Mizuno T. A novel sensor-regulator protein that belongs to the homologous family of signal transduction proteins involved in adaptive responses in Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol. 1992;6:799–807. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1992.tb01530.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ota I M, Varshavsky A. A yeast protein similar to bacterial two-component regulators. Science. 1993;262:566–569. doi: 10.1126/science.8211183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Parkinson J S, Kofoid E C. Communication modules in bacterial signaling proteins. Annu Rev Genet. 1992;26:71–112. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ge.26.120192.000443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Plamann L, Li Y, Cantwell B, Mayor J. The Myxococcus xanthus asgA gene encodes a novel signal transduction protein required for multicellular development. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:2014–2020. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.8.2014-2020.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schuster S C, Noegel A A, Oehme F, Gerisch G, Simon M I. The hybrid histidine kinase DokA is part of the osmotic response system of Dictyostelium. EMBO J. 1996;15:3880–3889. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shimkets L J. Social and developmental biology of the myxobacteria. Microbiol Rev. 1990;54:473–501. doi: 10.1128/mr.54.4.473-501.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sorokin A, Zumstein E, Azevedo V, Ehrlich S D, Serror P. The organization of the Bacillus subtilis 168 chromosome region between the spoVA and serA genetic loci, based on sequence data. Mol Microbiol. 1993;10:385–395. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb02670.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stout V, Gottesman S. RcsB and RcsC: a two-component regulator of capsule synthesis in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:659–669. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.2.659-669.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yang C, Kaplan H B. Myxococcus xanthus sasS encodes a sensor histidine kinase required for early development gene expression. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:7759–7767. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.24.7759-7767.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Udo H, Inouye M, Inouye S. Effects of overexpression of Pkn2, a transmembrane protein serine/threonine kinase, on development of Myxococcus xanthus. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:6647–6649. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.22.6647-6649.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.White O, Eisen J A, Heidelberg J F, Hickey E K, Peterson J D, Dodson R J, Haft D H, Gwinn M L, Nelson W C, Richardson D L, Moffat K S, Qin H, Jiang L, Pamphile W, Crosby M, Shen M, Vamathevan J J, Lam P, McDonald L, Utterback T, Zalewski C, Makarova K S, Aravind L, Daly M J, Minton K W, Fleischmann R D, Ketchum K A, Nelson K E, Salzberg S, Smith H O, Venter J C, Frase C M. Genome sequence of the radioresistant bacterium Deinococcus radiodurans R1. Science. 1999;286:1571–1577. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5444.1571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang W, Inouye M, Inouye S. Reciprocal regulation of the differentiation of Myxococcus xanthus by Pkn5 and Pkn6, eukaryotic-like Ser/Thr protein kinases. Mol Microbiol. 1996;20:435–447. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1996.tb02630.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang W, Munoz-Dorado J, Inouye M, Inouye S. Identification of a putative eukaryotic-like protein kinase family in the developmental bacterium Myxococcus xanthus. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:5450–5453. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.16.5450-5453.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]