Abstract

Following CART-19 immunotherapy for B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukaemia (B-ALL), many patients relapse due to loss of the cognate CD19 epitope. Since epitope loss can be caused by aberrant CD19 exon 2 processing, we herein investigate the regulatory code that controls CD19 splicing. We combine high-throughput mutagenesis with mathematical modelling to quantitatively disentangle the effects of all mutations in the region comprising CD19 exons 1-3. Thereupon, we identify ~200 single point mutations that alter CD19 splicing and thus could predispose B-ALL patients to developing CART-19 resistance. Furthermore, we report almost 100 previously unknown splice isoforms that emerge from cryptic splice sites and likely encode non-functional CD19 proteins. We further identify cis-regulatory elements and trans-acting RNA-binding proteins that control CD19 splicing (e.g., PTBP1 and SF3B4) and validate that loss of these factors leads to pervasive CD19 mis-splicing. Our dataset represents a comprehensive resource for identifying predictive biomarkers for CART-19 therapy.

Subject terms: Cancer genetics, High-throughput screening, Alternative splicing

Multiple alternative splicing events in CD19 mRNA have been associated with resistance/relapse to CD19 CAR-T therapy in patients with B cell malignancies. Here, by combining patient data and a high-throughput mutagenesis screen, the authors identify single point mutations and RNA-binding proteins that can control CD19 splicing and be associated with CD19 CAR-T therapy resistance.

Introduction

B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (B-ALL) is a haematologic malignancy that causes a significant number of childhood and adult cancer deaths. During CART-19 immunotherapy, chimeric antigen receptor-armed autologous T-cells (CARTs) are engineered to target the surface antigen CD19 on B cells by linking the single-chain variable fragment (scFv) of an anti-CD19 antibody to the intracellular signalling domain of the T-cell receptor1. Upon CD19 recognition, the chimeric antigen receptors activate the cytotoxic T-cells to attack the tumour cells. CART-19 therapy was recently approved for the treatment of paediatric B-ALL in the US and Europe, achieving initial remission rates up to 90%2. This indicates that B-ALL cells at initial screening are typically CD19-positive. Unfortunately, up to 50% of children relapse under CART-19 therapy, and response rates are even worse in adults3,4. Several studies reported that in 40–60% of relapse cases, the cancerous B cells become invisible to the CARTs because they lose expression of the CD19 epitope (CD19-negative)5–8. This recurrently involves alternative splicing of the CD19 pre-mRNA9–11.

Splicing involves the excision of introns and the joining of exons by the spliceosome to generate mature mRNAs. In alternative splicing, certain exons can be either included or excluded (“skipped”), resulting in different transcript isoforms. The splicing outcome at each exon is controlled by a large set of cis-regulatory elements in the RNA sequence which are recognised by trans-acting RNA-binding proteins (RBPs) that guide the spliceosome activity. It is increasingly recognised that widespread alterations in splicing are a molecular hallmark of cancer and often contribute to therapeutic resistance (reviewed in ref. 12). For instance, intron retention, i.e., the failure to remove certain introns, often disrupts the open reading frame (ORF) with premature termination codons (PTCs) and thereby compromises the expression of the encoded proteins. Consistent with the widespread splicing changes, cancer-causing driver mutations frequently occur in splice-regulatory cis-elements, and many splicing factors have oncogenic properties, being commonly mutated or dysregulated in cancer12–14.

Multiple alternative splicing events in CD19 mRNA have been described to interfere with CART-19 therapy9,11,15–18. Most prominently, skipping of exon 2 results in a truncated CD19 protein which is no longer presented on the cell surface and hence fails to trigger CART-19-mediated killing9,15. In addition, it was reported that relapsed patients showed retention of intron 2 which introduces a PTC, thereby disrupting CD19 expression11. Similarly, simultaneous skipping of exons 5 and 6 introduces a PTC9. The splicing alterations can be caused by mutations within the CD19 gene or by changes in the expression of trans-acting RBPs. For instance, it has been shown that the known splicing regulator SRSF3 binds to cis-regulatory elements within CD19 exon 2 to promote its inclusion9. Of note, alternative CD19 isoforms showing exon 2 skipping were observed to pre-exist in patients prior to CART-19 therapy16, suggesting that CD19 splicing patterns may harbour predictive information and could be modulated to re-establish sensitivity to CART-19-mediated killing. However, Orlando and co-workers suggested that alternative splicing changes in B-ALL patients are present in diagnostic samples already (albeit at low frequencies) and may not contribute meaningfully to CD19 epitope loss5. We, therefore, set out to investigate CD19 alternative splicing and its molecular determinants in B-ALL in more detail.

High-throughput mutagenesis screens combined with next-generation sequencing provide comprehensive insights into the regulatory code of splicing19–22. The interpretation of such data is challenging, as the mutation effects often depend on other mutations and are typically most pronounced at intermediate exon inclusion levels19,20,23. We and others have shown by mathematical modelling that kinetic models account for the context-dependence of mutation effects on splice isoforms19,20. By utilising these models, systems-level insights can be gained into complex cis-regulatory landscapes, effects of trans-acting RBPs, and principles of splicing regulation19,20,24.

In this work, we combine B-ALL patient data with high-throughput mutagenesis, mathematical modelling and RBP knockdowns to comprehensively characterise cis-regulatory mutations and trans-acting RBPs controlling CD19 exon 2 splicing. Unlike previous mutagenesis screens, we determine all intronic and exonic mutation effects in a 1.2 kb region and quantify the abundance of 100 alternative isoforms, including intron 2 retention and alternative 3′/5′ splice site usage. Many of these isoforms encode for a non-functional CD19 protein and are therefore likely to impair CART-19 therapy. By in silico analyses and RBP knockdowns, we identify trans-regulators of CD19 splicing that promote the production of the therapy-impacting isoforms. Taken together, our dataset allows for a systems-level understanding of the splicing code and provides a comprehensive resource of predictive markers for CART-19 therapy resistance.

Results

CART-19 patients show increased CD19 intron 2 retention after relapse

To resolve the contribution of CD19 splicing in CART-19 therapy, we re-analysed RNA-seq data from Orlando and co-workers5, in which B-ALL cells of 17 patients were sequenced at initial screening and after relapse. In contrast to the original study, we expanded the analyses to intron retention events surrounding CD19 exon 2. We found that the average frequency of intron 2 retention across patients is unexpectedly high (63%) before therapy and significantly increases to 82% after relapse (P value = 0.009, Wilcoxon signed-rank test; Fig. 1a, b). The trend towards higher intron 2 retention in the therapy-resistant tumours is preserved in seven out of nine individual patients that were sequenced both before therapy and after relapse (Fig. 1b). Since the resulting isoform does not encode a functional CD19 protein, this suggests that increased intron 2 retention contributes to CART-19 therapy resistance, as reported in a recent study11.

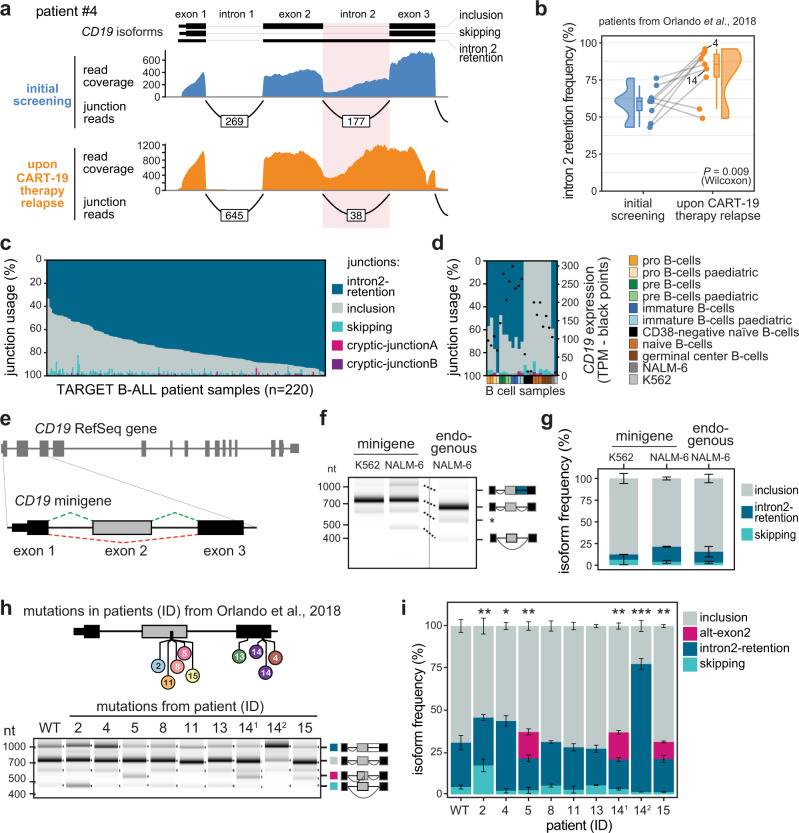

Fig. 1. Mutations from B-ALL patients cause CD19 mis-splicing.

a Patient #4 shows increased CD19 intron 2 retention after CART-19 therapy relapse. Re-analysed RNA-seq data from Orlando et al.5. Selected isoforms (GENCODE) are shown. b Intron 2 retention increases in B-ALL patients after CART-19 therapy relapse. Intron 2 retention frequency (as % of all isoforms) is shown for nine patients with matched RNA-seq data at screening and after relapse. P value = 0.009, one-sided paired Wilcoxon signed-rank test. Grey lines connect matched samples. Boxes represent quartiles, centre lines denote 50th percentile, and whiskers extend to most extreme values within 1.5× interquartile range (IQR). c, d Intron2-retention is the predominant isoform in B-ALL patients and pre B cells. Stacked bar chart shows relative usage (percent selected index, PSI; left y axis) of junctions originating from exon 3 (Supplementary Fig. 1a) in 220 patients from the TARGET B-ALL programme (c) and normal B cells44, 75 (n = 21) (d). Black dots in d indicate total CD19 mRNA expression, in transcripts per million (TPM; right y axis). Cell lines NALM-6 and K562 are shown for comparison. e The CD19 minigene spans exons 1–3 and the intervening introns from the CD19 gene. f, g The minigene generates the same isoforms as the endogenous CD19 gene in NALM-6 cells. Gel-like representation (f) and quantification (g) of semiquantitative RT-PCR showing isoforms intron2-retention (blue), inclusion (grey) and skipping (turquoise) for the WT minigene in NALM-6 cells. Isoforms of CD19 gene in NALM-6 cells are shown for comparison. Asterisk indicates a previously reported RT-PCR artefact66 (see Methods). Error bars indicate standard deviation of mean (s.d.m.), n = 3 replicates. P value > 0.1 for all isoforms, one-way ANOVA. h, i Patient mutations cause splicing changes in the CD19 minigene. Top: Location of the tested mutations. Patient IDs as reported in Orlando et al.5. 14.1 and 14.2 correspond to distinct mutations from patient #14. Gel-like representation (h) and quantification (i) of semiquantitative RT-PCR as in f, g. Additional isoform alt-exon2 (purple) includes a truncated version of exon 2. Error bars indicate s.d.m., n = 3 replicates. *P value < 0.05, **P value < 0.01, ***P value < 0.001, two-sided Student’s t test. Source data including P values are provided as a Source Data file.

Given the high prevalence of intron 2 retention even before CART-19 therapy, we extended our analysis to 220 B-ALL patients from the Therapeutically Applicable Research To Generate Effective Treatments (TARGET) programme. Although these patients had not been treated with CART-19, intron 2 retention appears as the predominant isoform in almost all of them (Fig. 1c, Supplementary Fig. 1a, b). This suggests that the cancer cells generally exhibit CD19 mis-splicing. Interestingly, strong intron 2 retention is also observed in immature B-cell precursors from healthy donors, whereas it is negligible in mature B cells (Fig. 1d). Therefore, incomplete B-cell differentiation in B-ALL may be accompanied by CD19 mis-splicing which is further aggravated during CART-19 therapy.

Somatic mutations in relapsed patients cause splicing alterations

To learn about the genetic causes of the splicing alterations during relapse, we took a closer look at the mutations accumulating in the B-ALL patients of the Orlando study5. The majority of relapsed patients (12 out of 17) harbour somatic mutations within the CD19 gene, including frameshift insertions, deletions and single nucleotide missense variants. We selected nine mutations in exons 2 or 3 from eight patients for further analysis (Supplementary Table 1). To test for effects on splicing, we constructed a minigene reporter that harbours CD19 exon 1–3 including the two intervening introns 1 and 2 (Fig. 1e). We confirmed that the minigene gives rise to the same transcript isoforms with quantitatively similar frequencies as the endogenous gene in the human B-ALL cell line NALM-6 (Fig. 1f, g, Supplementary Fig. 1c).

When introducing the patient mutations into our minigene reporter, we found that six out of nine tested mutations lead to the production of alternative CD19 isoforms linked to CART-19 therapy resistance (Fig. 1h, i, Supplementary Fig. 1d): The mutation from patient #2 induces exon 2 skipping, while mutations from patients #4 and #14 (#14.2) cause intron 2 retention. The latter mirrors the increase of this isoform in the same patients after CART-19 therapy relapse (Fig. 1b). In addition, three mutations enhance the production of an additional isoform that uses an alternative 3′ splice site in exon 2 (termed alt-exon2; mutations from patients #5, #14.1 and #15). We note that as reported by Orlando and co-workers5, most of the patient mutations also introduce frameshifts and therefore perturb CD19 protein expression by disrupting the open reading frame. Interestingly, splicing effects and frameshifts potentially interact in a non-intuitive way: For instance, the deletion in patient #5 causes a frameshift, but at the same time activates an alternative 3′ splice site (alt-exon2) which restores the open reading frame (Supplementary Fig. 1e). Thus, taking splicing information into account is essential to understand whether a targetable CD19 protein is generated in a patient harbouring CD19 mutations.

High-throughput screening of alternative splicing of CD19 exons 1–3

To systematically study the effects of point mutations on CD19 exons 1–3 splicing, we adopted our previously developed massively parallel splicing reporter assay19 (Fig. 2a). To this end, we randomly introduced point mutations as well as short insertions and deletions into the CD19 minigene reporter by error-prone PCR. This yielded a pool of 10,295 minigene variants, each with a different set of mutations and tagged with a unique 15-nt barcode sequence. As an internal control, 194 wild type (WT) minigenes with distinct barcodes were added. Mutations in all minigene variants were mapped using targeted long-read DNA sequencing (DNA-seq, PacBio SMRT-seq, Supplementary Fig. 2a, b) and validated for 30 minigene clones via Sanger sequencing. The DNA-seq data shows that the minigene variants contain on average 9.7 mutations (Supplementary Fig. 2c). This allows for a comprehensive characterisation of the mutation landscape, as each position is on average mutated in 80 different minigene variants and 90% of the mutations are present in at least four distinct minigene variants (Supplementary Fig. 2d, e). To measure splicing outcomes, the minigene pool was transfected into NALM-6 cells and the resulting transcripts were quantified by targeted RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) using 350 nt + 250 nt paired-end reads (Illumina MiSeq, Supplementary Figs. 2a, 3a). We detected around 100 different splice isoforms (see below) which were unambiguously identified by paired-end sequencing. Two replicate experiments showed a high correlation in the measured isoform frequencies (R between 0.91 and 0.98 for the different isoforms, Supplementary Fig. 3b). Based on the common barcode sequence, information from DNA and RNA sequencing could be combined, linking mutations at the DNA level to frequencies of RNA splice isoforms for a total of 10,295 minigenes in two replicate experiments (Supplementary Data 1).

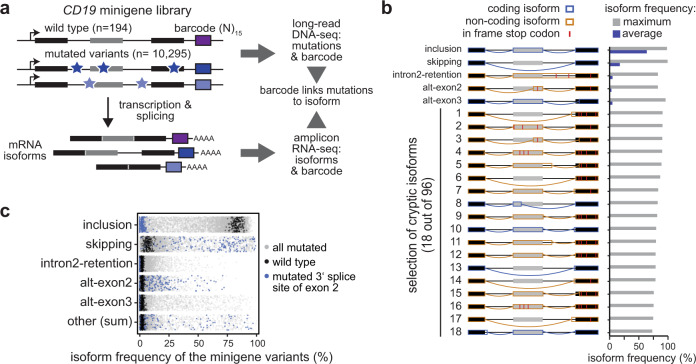

Fig. 2. High-throughput mutagenesis identifies splicing-affecting mutations and cryptic isoforms in the CD19 minigene.

a High-throughput detection of splicing-affecting mutations and cryptic isoforms. Mutagenic PCR creates mutated minigene variants (top) that upon transfection into NALM-6 cells give rise to alternatively spliced transcripts (bottom). Mutations (stars) and corresponding splicing products are characterised by DNA and RNA sequencing, respectively, and linked by a unique 15-nt barcode sequence in each minigene (coloured boxes). Black and grey boxes depict constitutive and alternative exons, respectively. b A large number of CD19 splice isoforms arise in the minigene library. CD19 splice isoforms with the highest maximal isoform frequency across all 9321 minigene variants. Schematic representation (left) of 5 major and 18 cryptic isoforms depicts exons 1–3 (boxes) and introns (horizontal lines) with splice junctions for each isoform (arches). Colour indicates coding potential (blue, coding; orange, non-coding). In-frame stop codons are indicated by red lines. Bar graph (right) shows average and maximal isoform frequency across all minigenes. Cryptic isoforms are sorted by maximal isoform frequency (Supplementary Data 2). c Inclusion isoform dominates in WT minigenes, whereas mutated variants show broad spread in all major isoforms. Frequencies of five major isoforms in replicate 1 for all wild type (black; n = 195) and mutated (grey; n = 9476) minigenes in the library. Minigene variants harbouring a mutation in the 3′ splice site of exon 2 (n = 174) are highlighted in blue. “Other” refers to the sum of 96 cryptic isoforms.

Therapy-impacting isoforms accumulate in response to numerous point mutations

To our surprise, the screen revealed a high complexity of CD19 exon 1–3 splicing, with a total of 101 alternative isoforms occurring with a frequency of ≥5% of all transcripts in at least two minigene variants (Supplementary Data 2). Out of these, the five major isoforms exceed 1% in WT minigenes, whereas the others, termed cryptic isoforms, only accumulate in mutated minigene variants (Fig. 2b). In WT, the most abundant major isoform by far is exon 2 inclusion (termed “inclusion”), followed by exon 2 skipping (termed “skipping”) and intron 2 retention (termed “intron2-retention”). Two additional major isoforms in WT originate from alternative 3′ splice site usage within exon 2 (alt-exon2) and 3 (alt-exon3) (Fig. 2b, c). Notably, alt-exon2 uses the same splice junction that we had observed upon introducing patient mutations into the CD19 minigene (Fig. 1i). As expected, the measured frequencies for the major isoforms show little variance for the 194 unmutated WT minigenes (standard deviation <6%, Fig. 2c). In contrast, many mutated minigene variants show strong changes relative to WT, suggesting a large impact of specific mutations on splicing outcomes (Fig. 2c). For instance, all minigenes with a mutation in the 3′ splice site of exon 2 lose the inclusion isoform, accompanied by strong alterations in the remaining major isoforms. Taken together, these observations support the accuracy of our screening results.

All major isoforms, except exon 2 inclusion, could contribute to therapy resistance either by generating an altered CD19 protein lacking a functional CART-19 epitope or by decreasing its production. Our unbiased screening approach extends the list of potentially therapy-impacting CD19 mutations, since 1721 out of 9127 mutated minigenes show exon 2 skipping, intron 2 retention and/or alt-exon2 isoform frequencies of >25% (Fig. 2c). However, since the minigene variants carry on average 9.7 point mutations, the observed splicing changes represent the combined effects of several mutations. To extract the impact of individual mutations, we adapted our previous mathematical modelling framework19 and implemented a multinomial logistic regression approach. Here, the splicing change in each minigene variant is described as the sum of the underlying point mutation effects (Fig. 3a, see Methods). These single-mutation effects are unknown and are determined by simultaneously fitting the model to all minigene measurements. Thereby, we were able to infer the individual effects of 4255 point mutations on the five major isoforms (Fig. 3a, Supplementary Fig. 4a). We validated the reliability of this model in describing combined mutations using a 10-fold cross-validation approach, in which we left out 10% of all minigene variants from fitting and were able to accurately predict them after model fitting (Pearson correlation coefficients 0.68–0.95; Fig. 3b, Supplementary Fig. 4b). In particular, isoforms abundant in WT or strongly accumulating in response to a large number of mutations (inclusion, skipping and alt-exon3) were predicted with high accuracy, whereas the prediction power was slightly lower for isoforms with a worse signal-to-noise ratio (intron2-retention and alt-exon2; Fig. 2c). Furthermore, we estimated that the model performed well in predicting single-mutation effects, as soon as a mutation occurred in three or more minigenes in the dataset (Supplementary Fig. 4c), which applied to 90% of all mutations (Supplementary Fig. 2e).

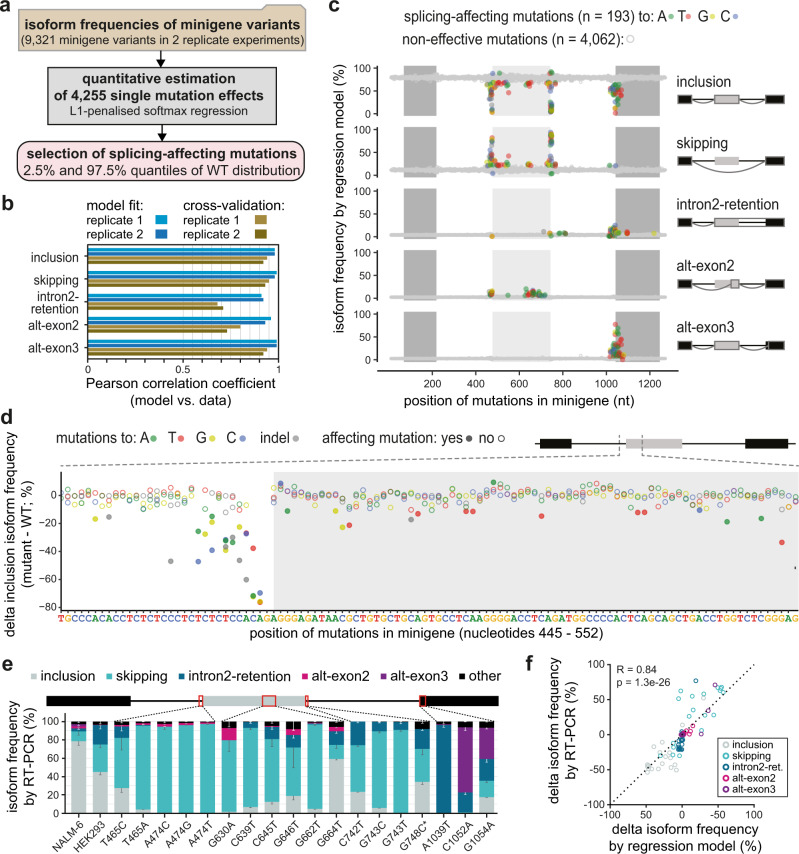

Fig. 3. Quantitative modelling predicts single-mutation effects on splice isoforms.

a Based on the experimentally measured frequencies of five major isoforms in 9321 minigene variants (top box), a softmax regression model was formulated to estimate 4255 single-mutation effects (middle box) using L1 penalisation. Splicing-affecting mutations were selected for each isoform based on their respective empirical WT frequency distribution using the 2.5% and 97.5% quantiles as cutoff. b The model performs well in fitting and 10-fold cross-validation. Bars show Pearson correlation coefficients between model and data for two replicates and each of the five isoforms across all combined mutation minigenes considered in model training and validation, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 4a, b). c Splicing-affecting mutations accumulate in distinct regions around exons 2 and 3. Landscape of model-predicted single-mutation effects on five major isoforms. Predicted isoform frequencies are plotted as a function of the position of a mutation. Colours indicate nucleotide substitution of splicing-affecting point mutations (see legend), and non-effective mutations (grey). d Zoom-in shows model-predicted delta inclusion isoform frequency (frequency for a point mutation - frequency in WT) for nucleotides 445–552 of the minigene. Splicing-affecting mutations are highlighted as filled circles. e Model validation by splicing analysis of 19 minigene variants containing single point mutations. Isoform frequencies (in %) of the five major isoforms (see legend) are shown as mean values of three biological replicates (error bars, s.d.m.). ‘NALM-6’, splicing pattern of WT minigenes (RNA-seq) in the mutagenesis screen, ‘HEK293′, RT-PCR-based quantification of the baseline minigene containing mutation G742C (see Methods) in HEK293 cells. G748C* is a minigene containing G748C but lacking G742C. Schematic representation of CD19 minigene (top) highlighting mutated regions (red rectangles). Error bar represent s.d.m., n = 3 replicates. f Splicing outcomes from e (y axis) are related to single-mutation predictions of the regression model (x axis; mean of two fits, each explaining one mutagenesis replicate). Changes in isoform frequency of the major isoforms (see legend) are expressed as differences (delta) relative to the baseline. Pearson correlation coefficient and P value (two-sided) were calculated over all isoforms (see Supplementary Fig. 5c for correlations of individual isoforms). Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Out of 4255 quantified single-mutation effects, we find 193 splicing-affecting mutations that significantly alter the frequency of at least one isoform in the two replicates beyond the 2.5 and 97.5% quantiles of the WT minigene distribution (Fig. 3c, Supplementary Data 3, Source Data file). 37 of these splicing-affecting mutations overlap with single nucleotide variants (SNVs) that were previously reported in the human population from whole-genome or exome sequencing data, as well as reported cancer-associated mutations, with some of them predicted to have a pathogenic or likely pathogenic effect in the disease context (Supplementary Data 3). The strongest mutation effects accumulate around the four main splice sites and throughout exon 2 and correspond to the core cis-regulatory elements, such as splice site dinucleotides, branchpoint and polypyrimidine tract, as well as auxiliary elements (Fig. 3c, d). In particular, 21% of all positions within exon 2 (55 out of 267 nt) harbour at least one splicing-affecting mutation for any isoform, suggesting that CD19 exon 2 is densely packed with cis-regulatory elements.

Inspecting in more detail the 83 mutations that specifically impact CD19 exon 2 skipping, we find them to cluster within and around exon 2 (odds ratio 2.06 for such mutations to occur inside exon 2, P value = 0.002614, Fisher’s exact test). In addition, we observe smaller clusters of mutations within the introns and flanking constitutive exons which likely represent more distal cis-regulatory elements (Fig. 3c). Similarly, we explored the 54 splicing-affecting mutations impacting on intron2-retention. As expected, strongest effects are observed at the splice sites of intron 2. In addition, we find clusters of splicing-affecting mutations in intron 2 and exon 3 that might reflect important cis-regulatory elements. The predicted effects of all mutations on the five major isoforms can be explored in the associated Source Data file.

To test a subset of the regression predictions, we generated 19 minigenes with individual point mutations that are predicted to affect at least one isoform, including two previously reported SNVs (Supplementary Fig. 5a, Supplementary Data 4). Using semiquantitative RT-PCR, we were able to confirm that mutations near the splice sites of exon 2 predominantly lead to exon 2 skipping, whereas mutations in exon 3 result in intron2-retention and/or alt-exon3 formation (Fig. 3e, Supplementary Fig. 5b). Overall, the splicing measurements for the individual minigenes show high correlation with the regression predictions for the respective mutations across all five major isoforms (Fig. 3f, Supplementary Fig. 5c). In conclusion, our combined screening and modelling approach quantitatively describes alternative splicing of CD19 exons 1–3 by predicting the effects of all individual point mutations and combinations thereof. Our screen thereby represents a comprehensive resource for the identification of mutations with potential clinical relevance in CART-19 therapy resistance.

Cryptic isoforms destroy the CD19 ORF and are associated with recurrent mutations

Besides the five major isoforms, the CD19 exons 1–3 can give rise to 96 cryptic isoforms which are rare (<1%) in WT, but accumulate upon certain mutations (Fig. 2b, Supplementary Data 2). The cryptic isoforms involve a total of 71 cryptic splice sites (Fig. 4a). Of note, 33 of these cryptic isoforms make up >50% of total transcripts and are therefore dominant in certain minigene variants (Fig. 2b, c). To assess whether these cryptic isoforms impact on CD19 epitope presentation, we analysed their coding potential and found that the vast majority of cryptic CD19 isoforms (78 out of 96) show a frameshift and/or carry a PTC (Fig. 4b). This will either lead to the production of truncated CD19 peptides that likely do not allow for presentation on the cell surface15 or will induce nonsense-mediated mRNA decay of the cryptic isoforms and will hence reduce CD19 transcript and protein levels.

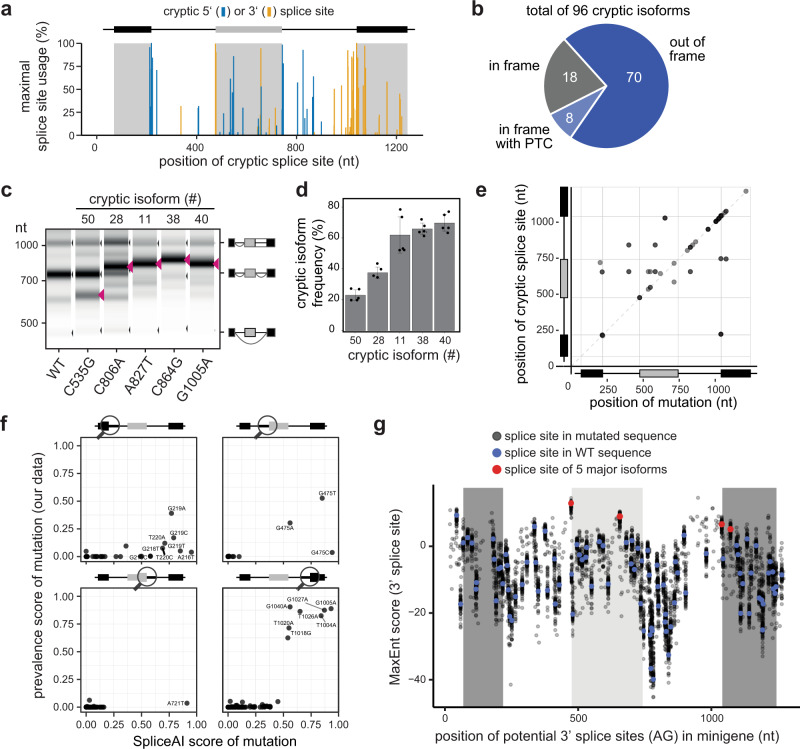

Fig. 4. CD19 mutations frequently activate cryptic splice sites.

a Alternative splicing of CD19 minigene variants involves 71 cryptic splice sites. Splice site usage (sum of junction-spanning reads in a splice site / total number of reads in minigene) was calculated for each minigene variant. Maximum usage across all minigenes is plotted against the corresponding position to the cryptic splice sites. b Cryptic isoforms code for non-functional CD19 proteins. Out of 96 cryptic isoforms, 8 run into a premature termination codon (PTC) and 70 are out-of-frame. The remaining 18 remain in frame, but are shortened or extended relative to the reference inclusion isoform. c, d Experimental validation of five point mutations associated with distinct cryptic isoforms. Predicted cryptic isoforms are indicated by red arrowheads. Gel-like representation (c), with major isoforms indicated on the right, and RT-PCR quantification (d). Error bars indicate s.d.m., n = 3 replicates. e Mutations leading to cryptic isoforms are often located within or near cryptic splice sites. For 31 cryptic isoforms that are highly associated with a mutation (prevalence score > 0.25; y axis), the position of the mutation (x axis) was related to the used cryptic splice site (y axis). f SpliceAI correctly predicts single mutations leading to the generation of cryptic isoforms. SpliceAI scores of 0–1 reflecting the probability to gain a cryptic splice site in response to a mutation (see Methods). Scatterplots compare the SpliceAI score against the prevalence score (association of a mutation with a cryptic isoform) from our data, for 254 mutation-splice site pairs that match in their positions with SpliceAI. Separate panels are shown for each canonical splice site (circle in schematic minigene representation). g Exon 3 harbours a weak 3′ splice site and is preceded by many potentially competing cryptic 3′ splice sites. Dotplot shows splice site strengths (MaxEnt score) for putative 3′ splice sites (AG dinucleotides) in the CD19 minigenes. MaxEnt score was calculated in 23-nt sliding window for WT sequence (red and blue dots) and hypothetical mutant minigenes with all possible single-point mutations (grey dots). 3′ splice sites used in the five major isoforms are highlighted in red. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

To derive a mechanistic understanding of cryptic isoform biogenesis, we analysed the underlying point mutations. To this end, we calculated a prevalence score which quantifies the degree of association between an isoform and a point mutation by multiplying: (i) the frequency of a mutation being present if the isoform level is high (>5%), and (ii) the frequency of the isoform level being high given that the mutation is present. A prevalence score of 1 indicates perfect correspondence between mutation and isoform, whereas a prevalence score of 0 is observed if they are unrelated. This score-based analysis revealed 38 mutation-isoform pairs with prevalence scores > 0.25 which could explain the genesis of 36 cryptic isoforms based on 31 point mutations (Supplementary Fig. 6a, Supplementary Data 2). The remaining 60 cryptic isoforms do not show a specific association, implying that they can either be generated by multiple redundant mutations, or that our screen lacks sufficient coverage to support a reliable association. To directly test the predicted associations, we introduced five mutations with a specific association to a cryptic isoform in our minigene reporter (C535G, chr16:28932405, prevalence score = 0.18; C806A, chr16:28932676, 0.68; A827T, chr16:28932697, 0.93; C864G, chr16:28932875, 1; G1005A, chr16:28932734, 0.89). Semiquantitative RT-PCR confirmed that all five tested mutations lead to the appearance of the associated cryptic isoform (Fig. 4c, d).

Altogether, our analysis provides a list of 31 mutations that are likely to trigger cryptic isoform formation. Importantly, the resulting cryptic isoforms show a maximum usage of up to 91% (Supplementary Data 2), which is expected to drastically interfere with normal CD19 splicing, protein production, and subsequent epitope presentation. Screening for the occurrence of the 96 cryptic isoforms in the TARGET B-ALL patient samples, we readily detected two junctions of cryptic isoforms that had been present already prior to CART-19 therapy (Fig. 1c, Supplementary Fig. 1a). Other cryptic isoforms predicted from our screen were not found in these patients that had not been treated with CART-19 therapy, but could already exist subclonally and/or may only emerge under the selective pressures of CD19-directed immunotherapy. The same applies to the associated mutations identified from our screen which were also not present in the TARGET B-ALL data (Supplementary Data 4).

The cryptic isoforms are caused by mutations that disrupt or create splice sites

Due to their potential clinical relevance, we wanted to learn more about how the mutations activate the cryptic isoforms. We found that the majority of mutations with a prevalence score > 0.25 are either in close proximity or directly overlap with the associated cryptic splice site (77.4% with distance <5 nt; odds ratio 7.55, P value = 1.793e-07, Fisher’s exact test; Fig. 4e). Further inspection showed that the underlying mutations either destroy the original splice site (7.9%) or generate a new cryptic splice site (57.9%). Hence, the cryptic isoforms do originate from the generation or destruction of core cis-regulatory elements rather than affecting auxiliary elements.

Currently, major efforts are ongoing to implement artificial intelligence (AI) tools to predict the effect of clinical variants on the splicing outcome. We therefore tested whether the state-of-the-art neural network SpliceAI25, which predicts changes in the splicing patterns induced by single point mutations, captures the gain and loss of splice sites in CD19. We applied SpliceAI using all possible single-point mutations in the CD19 minigene as an input. Similar to the results from our mutagenesis screen (Fig. 4a), SpliceAI predicts cryptic splice site activation by mutations throughout the minigene, with an increased density around the 3′ splice site of exon 3 (Supplementary Fig. 6b). All SpliceAI-predicted mutations are close to the affected cryptic splice sites (Supplementary Fig. 6c). Hence, SpliceAI successfully reflects the global landscape of mutation-induced cryptic splice site activation in the CD19 minigene.

With respect to the accuracy of the individual predictions, we found that 10 out of 38 mutations with strong SpliceAI predictions (SpliceAI score > 0.5) indeed lead to the accumulation of splice isoforms with the corresponding cryptic splice sites in the experimental data (prevalence score > 0.25, Fig. 4f). In the remaining 28 cases, either weak overall cryptic splice site activation occurred in the data (9 cases) or a different cryptic splice site was activated than predicted by SpliceAI (19 cases; Supplementary Fig. 6b). In quantitative terms, the likelihood of a cryptic splice site activation according to the SpliceAI prediction (“SpliceAI score”) is correlated to the magnitude of the prevalence score linking the mutation to the corresponding cryptic isoform in our screen (Fig. 4f). Overall, the comparison supports that SpliceAI can guide the interpretation of mutation effects in clinical samples, though direct experimental validation is necessary. Due to the robust performance of SpliceAI, we decided to predict splice-changing mutations throughout the entire CD19 gene and overlapped them with publicly reported single nucleotide variants (SNVs; Supplementary Fig. 6c). These predictions and variant overlap are provided as a resource (Supplementary Data 5) and can be used to evaluate the impact of new patient mutations on CD19 splicing in the future.

From our mutagenesis data, we found that the cryptic isoforms arise from numerous 3′ and 5′ cryptic splice sites that distribute over the entire minigene and accumulate at exon 3 (Fig. 4a). In line with their high prevalence, 26 cryptic splice sites reach >50% usage upon certain mutations, particularly around the start of exon 3. We hypothesised that cryptic splice site activation occurs in exon 3 because its canonical splice site can be outcompeted by neighbouring cryptic sites. To test this, we scored the strength of local consensus sequences using MaxEntScan26, and indeed found that the 3′ splice site of exon 3 is weak compared to all other canonical splice sites of CD19 exons 1–3 (Fig. 4g, Supplementary Fig. 6e, f). In line with our hypothesis, mutations around the 3′ splice site of exon 3 frequently create stronger splice sites than elsewhere in the minigene that exceed the strength of the canonical 3′ splice site of exon 3 (Fig. 4g). This suggests that weak splice sites are particularly vulnerable to the activation of competing cryptic splice sites and should be of particular interest when assessing the impact of clinical variants on splicing outcomes.

An extensive network of RBP regulators might drive CD19 mis-splicing

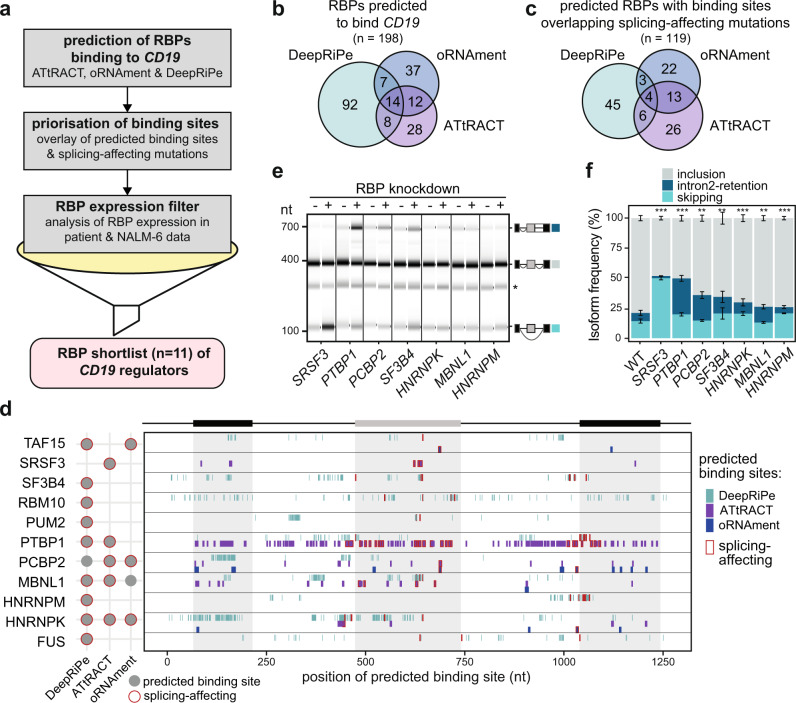

Besides CD19 mutations, CART-19 therapy resistance may also stem from altered expression of trans-acting RBPs which bind to the CD19 pre-mRNA to control alternative splicing. To identify putative RBP regulators, we explored publicly available databases containing experimentally determined RBP binding motifs (ATtRACT27 and oRNAment28). Furthermore, we included RBP binding information from the public resource of ENCODE eCLIP datasets29. Since the CD19 mRNA is hardly expressed in the ENCODE cell lines and binding events in CD19 can therefore not be directly extracted, we employed the prediction algorithm DeepRiPe30. The underlying neural network has been trained on the PAR-CLIP and ENCODE eCLIP datasets and thereby allows to predict changes of RBP binding upon mutation in any RNA sequence. In combination, these tools predict a total of 198 RBPs to bind within CD19 exons 1–3 (ATtRACT: 62 RBPs; oRNAment: 70 RBPs) or to decrease (or increase) binding upon mutation (DeepRiPe: 128 RBPs; Fig. 5a, b, Supplementary Fig. 7a).

Fig. 5. In silico predictions identify RBP regulators of CD19 alternative splicing.

a Pipeline for the identification of potential RBP regulators of CD19 splicing. Starting with in silico predictions, we obtained 198 candidate RBPs with predicted binding motifs (ATtRACT/oRNAment) or predicted differential binding upon mutation (DeepRiPe). These were prioritised by overlapping with the splicing-affecting mutations from our screen. Additionally, based on publicly available RNA-seq data, we required a minimum mean expression in RNA-seq data from B-ALL patients31 and NALM-6 cells75. Together with literature information, we shortlisted 11 candidate RBPs for knockdown (KD) experiments, including SRSF3 as a positive control. b, c In silico analyses predict dozens of RBPs binding to CD19. Venn diagrams show overlap of RBPs in initial predictions (b) and after overlay with splicing-affecting mutations (c). d The 11 candidate RBPs are predicted to bind throughout the CD19 minigene region. For each RBP, the binding sites predicted by ATtRACT and oRNAment and disrupting mutations predicted by DeepRiPe are indicated (see legend). Sites overlapping with splicing-affecting mutations are framed in red. The schematic summary (left) shows that all 11 candidate RBPs have at least one predicted site that overlaps with a splicing-affecting mutation. A full list of predicted binding sites (ATtRACT/oRNAment) and differential binding mutations (DeepRiPe) is provided in Supplementary Data 6. e, f Seven RBP KDs significantly change CD19 splicing. Gel-like representation (e) and quantification (f) of semiquantitative RT-PCR showing detected isoforms exon 2 inclusion (grey), intron 2 retention (blue), and skipping (turquoise) from the endogenous CD19 gene in KD and control NALM-6 cells. Asterisk indicates a previously reported RT-PCR artefact66 (see methods). Error bars indicate s.d.m., n = 3 replicates. **P value < 0.01, ***P value < 0.001, two-sided Student’s t test. Measurements for all 11 KD experiments are shown in Supplementary Fig. 8c, d. Source data including P values are provided as a Source Data file.

To link the putative RBP regulators to the observed splicing changes, we overlaid the predicted binding sites (or predicted mutations for DeepRiPe) with splicing-affecting mutations from our screen. Overall, we find that 79% and 60% of ATtRACT and oRNAment binding sites, respectively, overlap with a splicing-affecting mutation (affecting any of the five major isoforms). Furthermore, 105 (5%) of the mutations predicted to change RBP binding by DeepRiPe overlap with splicing-affecting mutations, suggesting that modulating RBP binding at these sites may have a functional impact on CD19 splicing (Fig. 5c, Supplementary Fig. 7a). By merging these sets, we obtained a list of 119 RBPs that may regulate splicing by binding to CD19 exons 1–3 (Supplementary Data 6). Most of these are expressed in cancerous B cells from B-ALL patients from31 (80 with mean FPKM [fragments per kilobase of transcript per million mapped reads] > 10; Supplementary Fig. 7b) and could thus modulate CD19 splicing. Among these RBPs are SRSF3, a previously reported regulator of CD19 splicing9, but also new candidates such as PTBP1. Overall, the in silico predictions suggest the presence of an extensive RBP network that controls CD19 splicing and may impact the CART-19 therapy success.

Depletion of PTBP1 and several other RBPs results in non-functional CD19 isoforms

Based on our experimental data, in silico predictions, expression, literature information and manual curation, we shortlisted 11 RBP candidates for further analysis, including SRSF3 as a positive control (Fig. 5d). All 11 RBPs are expressed in normal B cells and B-ALL patient samples from the TARGET B-ALL cohort (Supplementary Fig. 8a). To test their impact on endogenous CD19 splicing, we generated NALM-6 cell lines stably expressing shRNAs against the shortlisted RBPs (depletion to <40% transcripts; Supplementary Fig. 8b). As previously described9, knockdown of SRSF3 leads to increased exon 2 skipping in the endogenous CD19 transcripts, confirming that this SR protein is required for exon 2 inclusion (Fig. 5e, f). Importantly, we find that knockdown of six additional RBPs (PTBP1, PCBP2, SF3B4, HNRNPK, MBNL1 and HNRNPM) has significant effects on CD19 alternative splicing (Fig. 5e, f, Supplementary Fig. 8c, d). The knockdown of these factors reduces CD19 exon 2 inclusion, while promoting intron2-retention and/or exon 2 skipping, thus shifting the cells towards expression of the relapse-associated CD19 isoforms. This implies that reduced levels of these factors can impair targetable CD19 epitope expression.

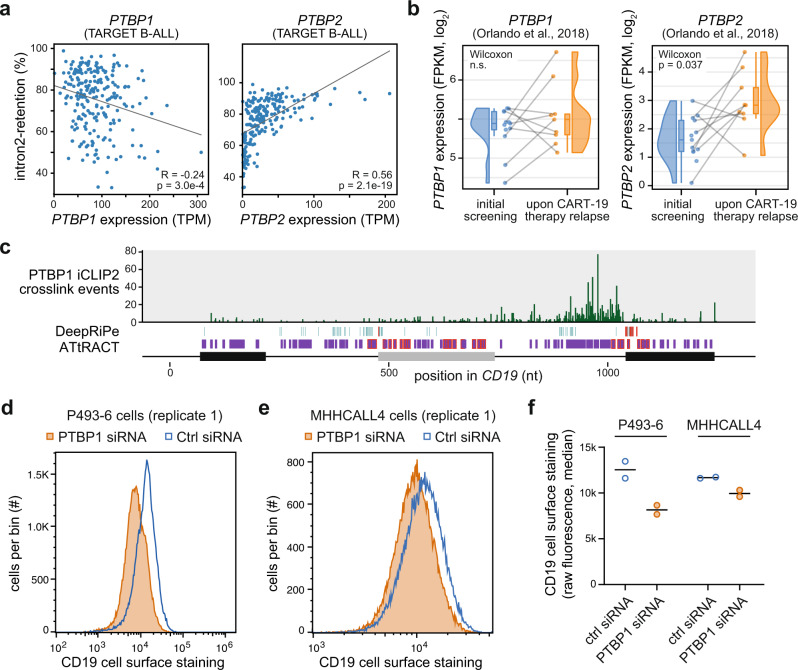

PTBP1 stands out among the putative regulators as it shows the strongest effects on intron2-retention. This splicing event introduces a premature termination codon that likely reduces CD19 transcript and protein expression via nonsense-mediated mRNA decay (Fig. 2b). In line with a role of PTBP1 in CD19 mis-splicing in tumours, we find that patient samples from the TARGET B-ALL cohort on average show lower PTBP1 mRNA expression compared to healthy B cells (Supplementary Fig. 8a). Within the B-ALL samples, PTBP1 expression negatively correlates with CD19 intron2-retention, as expected based on our knockdown experiments (R = -0.24; Fig. 6a, left). In addition, we investigated PTBP2 mRNA expression, which is tightly repressed by the PTBP1 protein via alternative splicing and nonsense-mediated mRNA decay32 and hence serves as a direct sensor for PTBP1 activity in the cells. Indeed, we find a strong correlation between increased PTBP2 mRNA levels, i.e., lowered PTBP1 protein activity, and increased CD19 intron2-retention (R = 0.56; Fig. 6a, right). To test for changes upon CART-19 relapse, we extracted PTBP1 and PTBP2 from expression data provided by the Orlando study5. Although we do not detect systematic changes in the PTBP1 mRNAs levels, the PTBP2 mRNA levels are significantly increased at relapse relative to screening, possibly indicating lowered PTBP1 protein levels (P value = 0.037, Wilcoxon rank-sum test; Fig. 6b). Together, these analyses suggest that PTBP1 is a regulator of CD19 alternative splicing, which we decided to explore further.

Fig. 6. PTBP1 is a regulator of CD19 alternative splicing.

a PTBP1 and PTBP2 mRNA levels correlate with CD19 intron2-retention. Scatterplots comparing mRNA levels (TPM) to intron2-retention frequency for 220 B-ALL patient samples from TARGET B-ALL data. Pearson correlation coefficients and P values (two-sided) are given. b PTBP2 mRNA levels are increased upon CART-19 therapy relapse. Box and violin plots showing PTBP1 and PTBP2 mRNA expression (fragments per kilobase of transcript per million mapped reads, FPKM) for patient samples (n = 9) from initial screening and upon CART-19 therapy relapse5. Grey lines connect matched samples of the same patients before therapy and after relapse. Boxes represent quartiles, centre lines denote 50th percentile, and whiskers extend to most extreme values within 1.5× IQR. One-sided paired Wilcoxon signed-rank test. c PTBP1 shows extensive binding to CD19 intron 2. Bar diagram shows the number of PTBP1 iCLIP2 crosslink events from NALM-6 cells on each nucleotide in endogenous CD19 exons 1–3. Predicted PTBP1 binding motifs (ATtRACT) and mutations predicted to alter PTBP1 binding (DeepRiPe) are shown below (see legend in Fig. 5d). Nucleotide positions are given relative to minigene sequence. d–f CD19 cell surface staining is reduced upon PTBP1 knockdown in P493-6 (d) and MHHCALL4 (e) cells. Distributions of CD19 surface protein, as measured in 45–50 × 103 cells (per replicate) by CD19 antibody staining and flow cytometry, in cells transfected with PTBP1 siRNA (orange) or non-targeting control siRNA (blue). f Dotplot shows mean and data points for measurements of cell surface CD19 in replicate 1 (d, e) and 2 (Supplementary Fig. 9f).

PTBP1 recognises clusters of UC-rich motifs33,34. Remarkably, ATtRACT predicts almost 100 such PTBP1 binding motifs across the studied CD19 region, including 25 that overlap with splicing-affecting mutations (Fig. 5d, Supplementary Data 6). Moreover, DeepRiPe predicts 78 mutations in 63 positions that change PTBP1 binding, out of which 10 are splicing-affecting in our screen (odds ratio 3.21, P value = 0.002481, Fisher’s exact test). The high number of predicted binding sites suggests a partial redundancy, indicating that PTBP1 regulation might be difficult to disrupt with individual point mutations as introduced in our screen. To experimentally test if PTBP1 binds to the predicted sites, we performed PTBP1 iCLIP2 experiments35 in NALM-6 cells. In line with a role in intron2-retention, we find extensive PTBP1 binding, particularly in intron 2, where it spreads over an extended cluster of predicted binding sites (Fig. 6c). This suggests that PTBP1 directly regulates CD19 splicing via intron 2 binding.

Next, we chose to assess whether PTBP1-mediated splicing changes affect CD19 surface exposure on B cells. To test this, we performed siRNA-mediated knockdown of PTBP1 in P493-6 and MHHCALL4 cells (Supplementary Fig. 9a, b) and confirmed that the knockdown increased levels of CD19 intron2-retention in both cell lines (Supplementary Fig. 9c, d). Then, we measured CD19 protein surface expression using CD19 antibody staining and flow cytometry analysis (Supplementary Fig. 9e). Strikingly, we found that both cell lines show reduced CD19 surface exposure upon PTBP1 depletion (Fig. 6d–f, Supplementary Fig. 9f). Thus, by interfering with CD19 protein expression on the cell surface, PTBP1 depletion could indeed contribute to CART-19 therapy resistance.

Taken together, our data suggest that both cis-acting mutations and trans-acting RBPs can lead to unproductive CD19 splicing which in turn disrupts CD19 epitope presentation. Therefore, the splicing-affecting mutations and RBP regulators identified in this work may harbour predictive information for CART-19 therapy success.

Discussion

Massively parallel reporter assays such as our high-throughput mutagenesis screen provide comprehensive insights into the regulatory code of splicing, as they characterise the complete set of cis-acting sequence mutations and reveal the binding sites of trans-acting RNA-binding proteins (e.g.,19–21,36–38). The interpretation of these datasets is challenging due to nonlinear interactions of individual mutation effects. For instance, competition effects in splicing reduce the impact of individual mutations at low and high isoform frequencies, i.e., depending on the mutational background19,20. In addition, other factors such as RBP expression patterns and cell type/tissue identity determine the effects of sequence mutations. Using kinetic modelling, we and others derived regression models taking competition in splicing into account, thereby showing that the effects of complex mutation combinations can be quantitatively described as the sum of individual mutation effects19,20. Thus, mutations seem to control splicing additively rather than synergistically, and this principle also holds for CD19 splicing.

In our CD19 mutagenesis dataset, we comprehensively characterise the full set of splice isoforms generated in response to thousands of sequence mutations. In particular, we find that cryptic splice site activation and thus alternative 3′ and 5′ splice site usage are common modes of alternative splicing. Intriguingly, such events do not require extensive sequence remodelling, but can often be triggered by single point mutations, as indicated by strong associations between putative cryptic isoforms and certain nucleotide substitutions. This suggests, in accordance with previous reports39, that neighbouring splice sites frequently compete for spliceosome assembly, especially if the canonical splice site is comparably weak. While this finding shows the enormous isoform complexity that can arise already from such a simple exon configuration, it raises the question of how protein function can be robustly maintained, since most cryptic CD19 splicing isoforms likely encode non-functional proteins.

Unlike previous mutagenesis screens which mainly focused on exonic sequence mutations, the present CD19 dataset characterises the complete set of intronic and exonic mutations in a 1200 nt sequence stretch. The complete characterisation of CD19 exons 1–3 required the use of long-read sequencing technology. Given that introns in human protein-coding genes on average span ~8.1 kb (GENCODE v31), the long-read sequencing methodology described in this work opens the approach for broad applications. For CD19, we find that strong mutation effects are mainly centred around canonical and cryptic splice sites, whereas in other examples such as MST1R exon 11 or FAS exon 6, mutation effects are more dispersed across intronic and exonic sequences19,40. This suggests that CD19 exon 2 splicing may be controlled by multiple splicing enhancers that act redundantly and render inclusion less sensitive to individual point mutations20. Therefore, CD19 exon 2 may require more specific perturbations and as we show here, does not only respond with exon skipping, but tends to employ alternative splice sites and intron retention, both of which are clinically relevant in the case of CART-19 therapy resistance.

Our retrospective analyses of clinical B-ALL samples implicate unproductive CD19 splice isoforms in the development of CART-19 therapy resistance. Using minigene assays, we directly show that CD19 mutations that are observed in relapsed patients lead to exon 2 skipping, intron 2 retention or an additional isoform that uses an alternative 3′ splice site in exon 2. Furthermore, based on our mutational scan, we report ~200 additional point mutations that significantly affect these and other therapy-impacting isoforms. Thus, our results indicate that far more CD19 mutations can create isoforms that would escape CART-19 recognition. In the future, targeted CRISPR/Cas9 replacement experiments using the endogenous CD19 gene should be performed to validate that the predicted mutations cause physiological changes in splicing, loss of CD19 protein exposure on cell surface and CART-19 therapy resistance. Furthermore, the detection of such mutations in longitudinal samples may provide predictive biomarkers for therapy response in the future.

Likewise, alterations in the expression of trans-acting RBPs can induce aberrant CD19 splicing, explaining the emergence of CD19-negative relapses in samples without mutations or with low-allelic-frequency mutations or without mutations in the CD19 locus. Interestingly, we find that the differentiation status of B cells affects CD19 splicing: in mature B cells, almost complete exon 2 inclusion occurs, implying that all CD19 transcripts give rise to functional CD19 protein. In contrast, intron 2 retention occurs in approximately half of the CD19 transcripts in undifferentiated B-cell precursors (Fig. 1d). Likewise, retention of intron 2 is predominant in B-ALL patient samples from the TARGET B-ALL cohort, with 93% of patients exhibiting retention frequencies above 50% (Supplementary Fig. 1b). Hence, incomplete B-cell differentiation in B-ALL may induce a transcriptional and posttranscriptional programme, likely involving altered RBP expression, that reduces (but does not completely eliminate) the functional CD19 protein pool. This partial intron 2 retention may predispose the cancer cells to therapy resistance before they are actually subjected to CART-19 treatment, as observed in sorted B-cell populations from a B-ALL patients before and after CART-19 therapy relapse17. For the development of complete CART-19 resistance, some B-ALL patients thus likely host subclonal CD19-negative B-ALL cells which are further selected under the treatment17. The causes of complete CD19 loss in these subclonal cell populations are likely to be manifold, involving (epi)genetic changes such as hypermethylation of the CD19 promoter41, mutations in the CD19 gene, splicing factor expression and combinations thereof.

Mutations in splicing factors such as SRSF2, SF3B1 and U2AF1 are common in myelodysplastic syndrome/acute myelogenous leukemia42 and chronic lymphocytic leukemia43, and are associated with aberrant splicing. In B-ALL, mutations in splicing factors are not common, but previous work suggests that splicing factor expression is deregulated44. In the context of CD19, we confirm that SRSF3 deregulation induces exon 2 skipping9 and identify several other RBPs that promote the expression CD19 protein isoforms invisible to the immunotherapeutic agent, including PTBP1, PCBP2, SF3B4, HNRNPK, MBNL1 and HNRNPM. Several of the newly identified regulators have been found as deregulated in other cancer types and are discussed as potential targets for anti-cancer therapy45–47. In addition, upregulation of PTBP1 has been implicated in acquired resistance to the chemotherapeutic agent gemcitabine in pancreatic ductal carcinoma cells48. In the context of lymphocytes, PTBP1 is upregulated in B cells and required for early B-cell selection49. It was reported, however, that treatment of leukemic cells with the targeted therapy drug imatinib, which inactivates the BCR-ABL kinase encoded by the translocated Philadelphia (Ph) chromosome, lowers PTBP1 levels50. In the light of our finding that PTBP1 knockdown increases CD19 intron 2 retention and thereby reduces CD19 epitope presentation, previous treatments with imatinib may have negative impact on the subsequent response to the CART-19 therapy in a subset of Ph+ B-ALL patients. In addition, a recent study showed that the repeat RNA PNCTR sequesters substantial amounts of nuclear PTBP1 in various cancers51. Thus, in addition to regulation of PTBP1 expression, other factors such as availability may also influence PTBP1-mediated regulation in B-ALL cells under CART-19 therapy.

Currently, we cannot predict which patients with a CD19-positive B-ALL have a high risk of developing CD19-negative relapses. The pre-existence of isoforms skipping exon 2 or exons 5–6 has been previously discussed as a possible biomarker16,17. Moreover, in a comparison of B cells from a B-ALL patient, it was found that intron 2 retention had already occurred prior to CART-19 therapy (CD19-positive B cells) and had become predominant in the CD19-negative B cells after relapse17. Our results point to the need to extend the analysis to additional CD19 isoforms and to incorporate the expression of splicing factors in screening approaches to identify patients at risk of relapse on CART-19 therapy. Notably, the same biomarkers might also be relevant for other malignancies arising from B-cell lineage, such as large B-cell lymphoma. Loss of CD19 following CART-19 therapy has been described as a mechanism for relapse52, accounting for 60% of relapses in recent clinical studies53. Our data show that CD19 splicing is highly complex, with already ~100 alternative isoforms concerning just exons 1–3. Of them, ~80% encode for a CD19 protein lacking a functional CART-19 epitope and are thus expected to contribute to therapy resistance. The specific detection of alternative splicing might serve as a reliable biomarker and may provide a novel approach to monitor disease progression as already suggested in other tumour entities54. To assess the role of the predicted cryptic splice isoforms in patients, we screened sequencing data from the TARGET B-ALL cohort and indeed recurrently found two junctions from the cryptic isoforms that we had observed in the mutagenesis data. Even though other cryptic junctions were absent and mutations associated with cryptic isoforms according to screen were also not found in the patient data, these may still emerge during CART-19 selection. Currently, there is a shortage of large-scale sequencing data of patient material before and after CART-19 therapy55. Future analysis of such data with a special focus on cryptic splice site usage will be important to identify mutations or splice isoforms that are predictive for CART-19 therapy success.

The contribution of aberrant splicing to CART-19 resistance may further be relevant for future combination therapies. Small-molecule splicing modulators are currently in clinical trials for myeloid neoplasms and splice-switching antisense oligonucleotides are in development for different targets (reviewed in12). Our mutagenesis dataset provides a strong basis for designing and systematically evaluating splice-switching oligonucleotides for the modulation of CD19 splicing. The combined application of these splicing modulators with immunotherapy may represent a way to limit the generation of resistance to CART therapies.

Methods

Cell lines

NALM-6 cells were obtained from ATCC and cultured in RPMI medium (Life Technologies) with 10% fetal bovine serum (Life Technologies) and 1% L-glutamine (Life Technologies). HEK293T cells were obtained from DSMZ and grown with the same additives as for NALM-6. For validation experiments (Fig. 3e), HEK293 cells were obtained from DSMZ and were cultured in Gibco Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM, Thermo Fisher Scientific) with L-Glutamine + 10% Gibco foetal bovine serum (FBS, Thermo Fisher Scientific). All cells were kept at 37 °C in a humidified incubator containing 5% CO2. They were routinely tested for mycoplasma infection.

Cloning

The CD19 minigene was amplified from human genomic DNA (Promega) with the primers 5′-catAAGCTTgaccaccgccttcctctctg-3′ and 5′-catGAATTCNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNGGATCCttcccggcatctccccagtc-3′. pcDNA3.1 was used as the vector backbone for the CD19 minigene plasmid. Both the backbone as well as the minigene amplicons were digested with the restriction enzymes EcoRI and HindIII (New England Biolabs). The backbone was extracted from a 1% agarose gel using QIAquick Gel Extraction Kit (Qiagen) and the minigene insert was cleaned up using QIAquick PCR Purification Kit (Qiagen). Ligation was conducted overnight at 16 °C with T4 DNA Ligase (New England Biolabs). All minigene mutations were introduced via Q5 Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit (New England Biolabs). Position 748 (nucleotide 6 of intron 2) was exchanged from G to T to raise the baseline level of exon 2 inclusion in the WT CD19 minigene to a similar level as in the endogenous CD19 gene. The nine mutations from eight patients in Orlando et al.5 listed in Supplementary Table 1 were inserted into the WT CD19 minigene. For validation experiments (Fig. 3e), 19 individual point mutations with predicted effects on at least one isoform were inserted into a CD19 minigene variant that additionally contained the mutation G742C to adjust the baseline of splice isoforms in HEK293 cells to the pattern seen in NALM-6 cells. All kits were used according to the manufacturers’ recommendations.

Mutagenesis of minigene and library construction

For the random mutagenesis of the CD19 minigene, GeneMorph II Random Mutagenesis Kit (Agilent) was used according to manufacturer’s recommendations using 500 ng CD19 minigene for 30 cycles at 56 °C with the amplification primers 5′-catAAGCTTgaccaccgccttcctctctg-3′ and 5′-catGAATTCNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNGGATCCttcccggcatctccccagtc-3′. PCR products were purified using QIAquick Gel Extraction Kit (Qiagen), digested with EcoRI and HindIII (New England Biolabs) and then ligated into the backbone.

Transfection with minigenes

Cells were twice washed in Dulbecco’s phosphate-buffered saline (DPBS, Gibco Thermo Fisher Scientific) and then collected in R buffer with a density of 2 × 107 cells/ml. For electroporation, we used 5 µg plasmid DNA (with a concentration of at least 1 µg/µl) to 2 × 106 cells in R buffer for a 100 µl NEON electroporation pipette tip (Thermo Fisher Scientific) at 1600 V for 30 ms and 1 pulse. Cells were harvested 24 h later. For validation experiments (Fig. 3e), 7 × 105 cells per well were seeded in six-well TC plates one day prior to transfection. 24 h later, cells were transfected with a mixture of 2 µg plasmid DNA and 20 µg linear Polyethylenimine MW 2500 (PEI 2500, Polysciences), and Gibco Opti-MEM (Thermo Fisher Scientific) was added to 100 µl total volume. This mixture was added dropwise to 1,9 ml fresh DMEM covering the cells, followed by incubation for 24 h.

Quantification of splicing isoforms using semiquantitative RT-PCR

Semiquantitative RT-PCR was used to quantify ratios of CD19 mRNA isoform variants. To this end, reverse transcription was performed on 500 ng RNA with RevertAid Reverse Transcriptase (Thermo Fisher Scientific) according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. Subsequently, 1 μl of the cDNA was used as template for the RT-PCR reaction with OneTaq DNA Polymerase (New England Biolabs). PCRs were run at the following conditions: 94 °C for 30 s, 28 cycles (minigene) or 34 cycles (endogenous CD19) of [94 °C for 20 s, 55 °C for 30 s, 68 °C for 30 s] and final extension at 68 °C for 5 min. The primers 5′-ACCTCCTCGCCTCCTCTTCTTC-3′ and 5′-GCAACTAGAAGGCACAGTCG-3′ were used for the CD19 minigene, and 5′-ACCTCCTCGCCTCCTCTTCTTC-3′ and 5′-CCGAAACATTCCACCGGAACAGC-3′ for the endogenous CD19 gene. A TapeStation 2200 capillary gel electrophoresis instrument (Agilent) was used for quantification of the PCR products on D1000 tapes.

For the semiquantitative RT-PCR experiments in HEK293 cells, cells were harvested 24 h after transfection and pelleted. RNA was isolated using the QiaGen RNeasy kit following the manufacturer’s protocol with the exception of adding only 100 µl of cell lysate onto the gDNA removal columns to ensure proper removal of genomic and/or plasmid DNA. 1–2 µg RNA per sample were used to generate cDNA with the ThermoScientific RevertAid cDNA kit. We changed the second temperature step of the manufacturer’s synthesis protocol from 4 °C to 25 °C (5 min) to further reduce RNA dimerisation or formation of secondary structures. Subsequently, 1 μl of cDNA was used as template for the RT-PCR reaction with OneTaq DNA Polymerase (New England Biolabs). PCRs were run at the following conditions: 94 °C for 30 s, 28 cycles of [94 °C for 20 s, 52 °C for 30 s, 68 °C for 30 s] (minigene) or 34 cycles of [94 °C for 20 s, 55 °C for 30 s, 68 °C for 30 s] (endogenous CD19) and final extension at 68 °C for 5 min. The primers 5′-ACCTCCTCGCCTCCTCTTCTTC-3′ and 5′-GCAACTAGAAGGCACAGTCG-3′ were used for the CD19 minigene, and 5′-ACCTCCTCGCCTCCTCTTCTTC-3′ and 5′-CCGAAACATTCCACCGGAACAGC-3′ for the endogenous CD19 gene. The PCR products were quantified using the TapeStation 4200 system and the High Sensitivity D1000 reagents and tapes (Agilent) according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

Significance of differences in isoform abundance for comparing WT minigenes vs. mutated variants (Fig. 1i) or RBP knockdown vs. control (Fig. 5f) was calculated by a Student’s t test separately for each isoform, reporting the smallest P value for each comparison. A one-way ANOVA was used to test whether isoform abundances are different in any of the three conditions shown in Fig. 1g.

Generation of stable and inducible shRNA knockdown cell lines

Production and preparation of lentivirus

Oligonucleotides with shRNA inserts against eleven RBPs (Supplementary Table 2) were ordered as Ultramer DNA Oligos from Integrated DNA Technologies (Leuven, Belgium). All sequences were based on56. Oligonucleotides containing shRNA inserts were PCR-amplified with primers 5′-TCTCGAATTCTAGCCCCTTGAAGTCCGAGGCAGTAGGC-3′ and 5′-TGAACTCGAGAAGGTATATTGCTGTTGACAGTGAGCG-3′ and purified with QIAquick PCR Purification Kit (Qiagen). shRNA inserts and miRE18_LT3GEPIR_Ren714 backbone (inducible via Tet-On system) were cut with EcoRI and XhoI (New England Biolabs). Backbone was purified from agarose gel with QIAquick Gel Extraction Kit (Qiagen). The fragments were then ligated with T4 DNA Ligase (New England Biolabs) at 16 °C overnight.

Constructs were transduced into NALM-6 via HEK293T-produced lentiviruses. To this end, 10 cm dishes of HEK293T were transfected using 30 µl Lipofectamine 2000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific) with three plasmids: 4 µg shRNA-producing constructs + 2 µg psPAX2 (lentiviral packaging) + 1 µg pMD2.G (lentiviral envelope) at 72 h prior to transduction. On the first day after transfection, the medium was changed. Work with cells used for lentiviral production was conducted in the S2 laboratory.

Transduction of NALM-6 cells

Lentiviral production was confirmed with Lenti-X GoStix (Takara) and lentiviruses were concentrated with Lenti-X Concentrator (Takara) according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. For transduction, 1 × 106 NALM-6 cells in 500 µl of medium were added to the concentrated virus. 5 µg/ml polybrene (Sigma-Aldrich) was added. The cells were centrifuged at 800 g and 32 °C for 30 min. Cells were then transferred into 6-well plates and cultivated in normal growth medium without antibiotics. Selection was started after 48 h with 0.5 µg/ml puromycin (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Antibiotic medium was exchanged every 2–3 days. As soon as cells were not dying under selection anymore and the population was stable, induction experiments were started. After transduction, cells remained in the S2 laboratory for at least 6 weeks. Then, Lenti-X GoStix was used to check for any remaining lentivirus.

Induction of stable shRNA-expressing NALM-6 cells

Controlled by the Tet-responsive TRE3G promoter, the expression of shRNA was induced by addition of doxycycline (Thermo Fisher Scientific). To this end, 2 × 106 NALM-6 cells were seeded into a six-well plate in 2 ml medium containing 0.5 μg/ml puromycin and induced with 0.5 μg/ml doxycycline, diluted in RPMI 1640 medium (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Induction was conducted at 37 °C and 5% CO2 and cells were harvested after 48 h. During induction, the shRNA expression system is coupled to the production of eGFP, which was examined by fluorescence microscopy before harvesting.

Quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR)

RNA was extracted from the induced harvested cells using the RNeasy Plus Mini Kit (Qiagen). This RNA was used for qPCR to validate the RBP knockdown as well as for semiquantitative RT-PCR experiments to check the splicing pattern of endogenous CD19. The qPCR was conducted using the Luminaris HiGreen qPCR Master Mix, low ROX (Thermo Fisher Scientific) according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. Oligonucleotide sequences of all qPCR primers are given in Supplementary Table 3.

Targeted DNA sequencing

DNA-seq of the minigene library was performed on the PacBio SMRT sequencing platform at MPI-CBG Dresden. For this purpose, the minigene plasmid library was digested with EcoRI and HindIII (New England Biolabs) and run on an agarose gel. The desired band at the size of 1301 nt was cut out and purified using QIAquick Gel Extraction Kit (Qiagen). For the run on the PacBio SMRT cell, standard library preparation was performed.

Targeted RNA sequencing

NALM-6 cells were electroporated with the mutated minigene library (see above). 24 h later cells were harvested and RNA was isolated via the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen). 20 µg isolated RNA was poly-A-selected using Dynabeads Oligo (dT)25 beads (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. Reverse transcription was performed on 500 ng poly-A-selected RNA with RevertAid Reverse Transcriptase (Thermo Fisher Scientific) according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. To prevent chimeric amplicons, the RNA-seq libraries were amplified via emulsion PCR57 using the Phusion DNA Polymerase (New England Biolabs). The following primers containing Illumina adaptors were used in the PCR: 5′- CAAGCAGAAGACGGCATACGAGATCGGTCTCGGCATTCCTGCTGAACCGCTCTTCCGATCTNNNNNNNNNNGGAACCTCTAGTGGTGAAGG-3′ (fwd) 5′-AATGATACGGCGACCACCGAGATCTACACTCTTTCCCTACACGACGCTCTTCCGATCTNNNNNNNNNNCCGCCAGTGTGATGGATATC-3′ (rev) under following conditions: 98 °C for 30 s, 25 cycles of [98 °C for 10 s, 63 °C for 20 s, 72 °C for 1 min] and final extension at 72 °C for 5 min. Amplicons were purified using Agencourt AMPure XP beads (Backman Coulter). Purified products were analysed on the TapeStation 2200 capillary gel electrophoresis instrument (Agilent) and quantified using the Qubit assay (Thermo Fisher Scientific). RNA-seq was carried out on the Illumina MiSeq platform using paired-end reads of 350 nt + 250 nt length and a 10% PhiX spike-in to increase sequence complexity.

PTBP1 iCLIP2 experiments

We used the iCLIP2 approach for transcriptome-wide mapping of PTBP1 binding to RNA in NALM-6 cells. iCLIP2 was performed according to our previously published protocol35. Briefly, the iCLIP2 libraries were made from NALM-6 cells grown in RPMI as described above (2 × 106 cells per replicate). To induce protein-RNA crosslinks, the cells were irradiated with 150 mJ/cm2 UV light at 254 nm. Next, PTBP1 protein-RNA complexes were immunoprecipitated using 2 µg of anti-PTBP1 antibody (Santa Cruz, sc-56701). RNase digestion was performed by adding 10 µl of 1/300 or 1/500 diluted RNase I (Ambion) to the sample. RNA purification, reverse transcription and library preparation were done as described in35.

PTBP1 siRNA electroporation in MHHCALL4 and P493-6 cells

The cell lines MHHCALL4 and P493-6 were electroporated with a specific siRNA targeting PTBP1 (TAGCAAGATGATACAATGGTA[dT][dT]; Sigma, sR90) or a Scramble control (D-001810-10-50, Dharmacon) using the Neon Transfection System (Thermo Fisher Scientific). In short, 5 × 105 cells were resuspended in 10 µl of 5 µM siRNA in buffer R and electroporated using the Neon Transfection System 10 µL Kit (MPK1096, Thermo Fisher Scientific) with the following settings: 1700 V, 20 ms, 1 pulse. After electroporation, the cells were cultured in the recommended media for 48 h and collected for CD19 cell surface staining, quantitative real-time PCR and Western blot.

CD19 cell surface staining

In all, 1 × 105 cells were resuspended in 50 µl of PBS, 20% FBS, 1 mM EDTA and 2.5 µl of Human TruStain FcX blocking (422302, BioLegend) and incubated for 20 min. After blocking, 2.5 µl of APC anti-human CD19 antibody (1:20, 982406, BioLegend) was added to the cells and incubated for 30 min. Cells were washed twice with PBS, 20% FBS, 1 mM EDTA and the CD19 staining was measured using the BD Accuri C6 Plus Flow Cytometer instrument (BD Biosciences). Flow cytometry data was analysed with FlowJo (version 10.7.2) software.

Western blot

Cell pellets were resuspended in RIPA buffer with Protease/Phosphatase Inhibitor (1861282, ThermoScientific) and 30 µg of protein were loaded in a 10% pre-cast gel (456-1035, BioRad). Antibodies against CD19 (1:1000, #3574, Cell Signalling), PTBP1 (1:500, sc-56701, Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and β-Actin (1:5000, 8H10D10, Cell Signalling) were used for total protein expression detection. Images were acquired with GBox instrument (Syngene).

Quantitative real-time PCR

RNA was extracted using the Maxwell RSC Instrument (Promega) and the Maxwell® RSC simplyRNA Cells Kit (AS1390, Promega). 0.5 µg or RNA were reverse-transcribed using the SuperScript™ IV Reverse Transcriptase kit (18090010, Invitrogen) following the manufacturer’s protocol. RNA expression was measured using SYBR Green Master MIX (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Quantitative real-time PCR was performed in a QuantStudio™ 7 Pro Real-Time PCR System (Thermo Fisher Scientific) with specific primers (Supplementary Table 3) spanning the exon-exon junctions between exons 2 and 3 (E2E3 1&2), 3 and 4 (E3E4), and 10 and 12 (E10E12) as well as the exon-intron junctions from exon 2 to intron 2 (e2i2), from intron 2 to exon 3 (i2e3).

Re-analysis of RNA-seq data from Orlando et al

We re-analysed RNA-seq data of B-ALL patients at screening and after CART-19 therapy relapse from Orlando et al.5 to quantify intron 2 retention in CD19. Since raw data were not available, we obtained BAM files for the different patients deposited in the Short Read Archive (SRA) under the accession SRP141691. For 10 patients, matched data were available at screening and relapse. We excluded one patient (patient #17) after visual inspection indicating that the submitted data in fact corresponded to DNA-seq rather than RNA-seq data. The data contained the aligned reads mapped to several genes from the immune system including CD19. Using custom scripts, we extracted the sequence of the reads, reformatted them and generated fastq files. We then mapped the fastq files to our minigene sequence using STAR58 (v2.6.1). We used the re-mapped reads to quantify the levels of intron 2 retention in the different samples using the R/Bioconductor package ASpli59 (version 1.12.1).

For the expression analysis of B-ALL patients at screening and after CART-19 therapy relapse, we used the gene read counts provided in Supplementary Data Table 1 of Orlando et al.5. Gene lengths were taken from BiomaRt (version 2.4.21) for the human genome version GRCh37 accessed through the R/Bioconductor package OrgDb (version 3.10.0). Normalisation and RPKM calculations were performed using the R/Bioconductor package edgeR60 (version 3.28.1).

DNA-seq barcode demultiplexing

We obtained the circular consensus sequences (CCS), stored as fastq files. Two rounds of sequencing yielded a total of 337,215 CCS. We kept only reads with a length of 150–1150 nt. We adapted the demultiplexing procedure described in19. In this case, we searched for the 15-nt barcode in the last 50 nt of the read. If the barcode was not found, we searched in the last 50 nt of the reverse complementary strand. We only allowed the recovery of barcodes ranging from 14 to 16 nt, which would account for barcodes containing one nucleotide inserted or deleted. Before proceeding with the variant calling, we determined a cutoff to decide the minimal number of CCS to call variants on. Here, we kept only barcodes supported by at least 4 CCS. In total, we recovered 68.5% of all the demultiplexed barcodes which corresponded to 10,558 different minigenes, closely resembling the ~10,000 minigene clones that were used to generate the library.

DNA-seq mapping and variant calling

We use BLASR61 with the standard parameters to map the demultiplexed minigene sequences to the minigene reference. We performed variant calling in the aligned BAM files using the GATK62 HaplotypeCaller (version 4.0.10) with the parameters --kmer-size 10 --kmer-size 15 --kmer-size 25 --allow-non-unique-kmers-in-ref. We used different k-mer sizes to improve the detection of problematic regions. Mixed barcodes, i.e., barcodes containing two classes of mutations, were removed based on the “penetrance score”, reported as allele frequency (AF) in the GATK vcf output files, such that barcodes with more than 25% variants of low penetrance (AF < 0.8) were discarded. Using this strategy, we were able to recover 100,135 mutations of high quality coming from 10,295 distinct minigenes plus an additional 194 unmutated WT minigenes with distinct barcodes. 57.4% of the mutations appeared in at least ten different minigenes.

RNA-seq barcode demultiplexing

RNA-seq libraries were sequenced on Illumina MiSeq as 350 nt + 250 nt paired-end reads, yielding approximately 23 million reads. We controlled their quality using FastQC (version 0.11.5, https://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc/) and removed bad quality ends of reads using Trimmomatic63 (version 0.36, parameters: SLIDINGWINDOW:6:10 MINLEN:0). After trimming, we filtered for read pairs with a minimal length of 305 nt (read1) and 157 nt (read2) and, as done in Braun et al.19, we used matchLRPatterns() and trimLRPatterns() from the R/Bioconductor package Biostrings to extract the 15-nt barcode in read1 between the two flanking restriction sites (Lpattern = TGCAGAATTC, Rpattern = GGATCC) allowing one mismatch. All read pairs with barcode length between 14 and 16 nt were kept for further processing. Barcode sequences were added to the read names in the fastq file and 5′ ends of reads were trimming (read1: everything until the second anchor sequence GGATCC, read2: the first 12 nt). After identifying and trimming the barcode and other regions, we used Cutadapt64 (version 1.6, parameters: --adaptor=TAGAGGTTCC --overlap=3 --error-rate=0.1 --no-indels --minimum-length=244 --pair-filter=both) to remove remaining primer sequences from read1. Lastly, the barcode information attached to the read names was used to demultiplex all read pairs into individual fastq files for each minigene.

Isoform quantification from RNA-seq data

Only barcodes/minigenes also detected in the DNA-seq library were kept for further analysis. All minigenes with insertions or deletions of 10 or more base pairs were removed from further analysis. For better mapping results, we shortened read1 to at most 260 nt. Read pairs of each minigene were mapped to the respective minigene (including all mutations with penetrance ≥0.8, but excluding insertions and deletions) using STAR58 (version 2.6.1b). An annotation of three isoforms (exon 2 inclusion and skipping, as well as the artefact PCR product Δex2part which lacks an internal fragment of exon 2 due to a reverse transcription artefact65) was provided to STAR during mapping and an --sjdbOverhang of 259 was set. When running STAR, all SAM attributes were written, up to ten mismatches were allowed, soft-clipping was prohibited on both ends of the reads and only uniquely mapping reads were kept for further analysis. BAM files were sorted and indexed using SAMtools66 (version 1.5).