Key Points

Question

In patients with locally advanced head and neck squamous cell carcinoma who are ineligible to receive treatment with cisplatin, should cetuximab-based or carboplatin-based chemoradiotherapy be used?

Findings

In this cohort study of 8290 US veterans with nonmetastatic head and neck squamous cell carcinoma treated with chemoradiation from January 2006 to December 2020, more than a third received noncisplatin (cetuximab or carboplatin) systemic therapy. After propensity score–based inverse probability weighting, treatment with carboplatin was associated with 15% improved overall survival compared with cetuximab, a difference that was prominent in patients with oropharynx cancer.

Meaning

The study results suggest that for cisplatin-ineligible patients undergoing treatment with chemoradiation, carboplatin-based systemic therapy may provide superior outcomes compared with cetuximab.

Abstract

Importance

Cetuximab-based and carboplatin-based chemoradiotherapy (CRT) are often used for patients with locally advanced head and neck cancer who are ineligible for cisplatin. There are no prospective head-to-head data comparing cetuximab-based and carboplatin-based regimens for radiosensitization.

Objective

To compare survival with cetuximab-based and carboplatin-based CRT in locally advanced head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC).

Design, Setting, and Participants

This cohort study included US veterans who received a diagnosis of HNSCC between January 2006 and December 2020 and were treated with systemic therapy and radiation. Data cutoff was March 1, 2022 and data analysis was conducted from April-May 2022.

Exposures

Cisplatin, cetuximab, or carboplatin-based systemic therapy as captured in VA medication data and cancer registry.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Overall survival by systemic therapy was estimated using Kaplan-Meier methods. We used propensity score and inverse probability weighting to achieve covariate balance between cetuximab-treated and carboplatin-treated patients and used Cox regression to estimate cause-specific hazard ratios of death associated with carboplatin vs cetuximab. We also performed subgroup analyses of patients with oropharynx vs nonoropharynx primary sites.

Results

A total of 8290 patients (median [IQR] age, 63 [58-68] years; 8201 men [98.9%]; 1225 [15.8%] Black or African American and 6424 [82.6%] White individuals) with nonmetastatic HNSCC were treated with CRT with cisplatin (5566 [67%]), carboplatin (1231 [15%]), or cetuximab (1493 [18%]). Compared with cisplatin-treated patients, patients treated with carboplatin and cetuximab were older with worse performance status scores and higher comorbidity burden. Median (IQR) overall survival was 74.4 (22.3-162.2) months in patients treated with cisplatin radiotherapy (RT), 43.4 (15.3-123.8) months in patients treated with carboplatin RT, and 31.1 (12.4-87.8) months in patients treated with cetuximab RT. After propensity score and inverse probability weighting, carboplatin was associated with improved overall survival compared with cetuximab (cause-specific hazard ratio, 0.85; 95% CI, 0.78-0.93; P = .001). This difference was prominent in the oropharynx subgroup.

Conclusions and Relevance

In this cohort study of a US veteran population with HNSCC undergoing treatment with CRT, almost a third of patients were ineligible to receive treatment with cisplatin and received cetuximab-based or carboplatin-based radiosensitization. After propensity score matching, carboplatin-based systemic therapy was associated with 15% improvement in overall survival compared with cetuximab, suggesting that carboplatin may be the preferred radiosensitizer, particularly in oropharynx cancers.

This cohort study compares survival with cetuximab-based and carboplatin-based chemoradiotherapy in locally advanced head and neck squamous cell carcinoma.

Introduction

For patients with locally advanced head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) undergoing definitive chemoradiotherapy (CRT), cisplatin is the preferred systemic agent for radiosensitization. However, many patients with HNSCC have relative or absolute contraindications to treatment with cisplatin, including kidney dysfunction, hearing loss, neuropathy, advanced age, and performance status. For patients ineligible to receive treatment with cisplatin, alternate systemic radiosensitizing agents include cetuximab and carboplatin-based chemotherapy. Cetuximab and carboplatin-fluorouracil with radiotherapy (RT) have been associated with improved survival compared with RT alone in randomized clinical trials.1,2,3

While multiple trials have demonstrated that cetuximab is inferior to cisplatin-based CRT, particularly in human papillomavirus (HPV)–related cancers,4,5,6,7 to our knowledge, cetuximab and carboplatin-based radiosensitization have never been compared head-to-head in a prospective trial. Retrospective studies comparing noncisplatin CRT regimens for HNSCC have largely shown improved progression-free and overall survival with carboplatin compared with cetuximab.8,9,10,11,12 However, these have been relatively small single or double-institution cohorts that were subject to bias from institutional preferences and baseline imbalances between cetuximab-treated and carboplatin-treated groups. Thus, there remains uncertainty and substantial practice variation in the choice of systemic therapy for cisplatin-ineligible patients undergoing CRT.

We sought to address this knowledge gap by comparing survival with cetuximab-based vs carboplatin-based CRT in a large nationwide contemporary cohort of US veterans, who have a high burden of frailty13 and numerous comorbidities, including tobacco use and heart disease,14,15,16 that predispose them to cisplatin ineligibility. We used propensity score and inverse probability weighting methods to account for baseline imbalances in covariates between carboplatin-treated and cetuximab-treated patients.

Methods

Data Source and Cohort

The electronic health record data of veterans with newly diagnosed HNSCC within the Veterans Health Administration (VA) from 2006 to 2020 were obtained and accessed through the Corporate Data Warehouse (CDW). This research protocol was approved by the institutional review boards and research and development committees at the VA Medical Centers of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, and Salt Lake City, Utah. The data were collected within a waiver of informed consent and US Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act authorization.

Veterans who either initially received their diagnosis or sought their first treatment for cancer in the VA are recorded as complete analytic cases in the cancer registry. Complete HNSCC analytic cases diagnosed from 2006 to 2020 were identified, and patients identified in the cancer registry as receiving definitive CRT with cisplatin, carboplatin, or cetuximab were included in the study cohort. Patients with distant metastatic disease at diagnosis, patients who received radiotherapy or systemic therapy alone, and patients who underwent surgery as part of their primary treatment were excluded.

Exposures and Covariates

Systemic therapy was classified as cisplatin-based, carboplatin-based, or cetuximab-based in the cancer registry, pharmacy tables, and billing codes within CDW using a 6-month postdiagnosis window. Patients who could not be uniquely classified because of recorded treatment with more than 1 agent (eg, carboplatin and cetuximab) were excluded. Patient-level information, including age, sex, race and ethnicity, smoking status, marital status, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status, Charlson-Deyo comorbidity index score, and baseline comorbidities (hypertension, hyperlipidemia, diabetes, coronary artery disease, and kidney disease), were obtained from tables within CDW. Primary site (oropharynx vs nonoropharynx) was defined using a combination of diagnosis and procedure codes (eTable 1 in the Supplement).

Outcome

The primary outcome was overall survival, defined as time from treatment initiation to death of any cause, which was ascertained from vital status tables within the CDW. Patients without a date of death were censored at date of last contact within the VA system. The cutoff date for data abstraction was September 17, 2021.

Survival Analysis

Kaplan-Meier methods were first used to estimate overall survival by systemic therapy category (cisplatin, carboplatin, cetuximab) in the overall cohort and in the oropharynx and nonoropharynx subgroups. For all other analyses comparing cetuximab and carboplatin, patients treated with cisplatin were excluded.

To compare survival between patients treated with cetuximab vs carboplatin while accounting for confounders and baseline imbalances between the groups, we estimated a propensity score for the probability of receiving carboplatin vs cetuximab using a logistic regression that incorporated several potential confounders (age, sex, diagnosis year, race and ethnicity, tumor and nodal stage, primary site, performance status, Charlson comorbidity index score, smoking status, marital status, and baseline hypertension, hyperlipidemia, diabetes, coronary disease, and kidney disease) as predictors. Because some variables had missing data, multiple imputation was used for all propensity score analyses. Complete data sets were imputed using multiple imputation via chained equations.17

Using the generated propensity scores, inverse probability weighting was used to construct balanced pseudopopulations. Kernel density and box plots of propensity scores were generated for the preweighted and postweighted carboplatin and cetuximab populations to visually assess overlaps. Standardized mean differences were estimated in the unweighted and inverse probability weighted populations to ensure a postweighting balance between groups for all potential confounders.

Finally, a Cox regression of the inverse probability–weighted population was used to estimate the cause-specific hazard ratio of death associated with carboplatin vs cetuximab. Because we were interested in the etiologic association between systemic agents and survival, rather than prognostic questions, we chose a Cox regression and cause-specific hazard over Fine and Gray methods and a subdistribution hazard. The proportional hazards assumption was assessed using Schoenfeld residuals. Analyses using inverse probability weighting were conducted within each of the multiply imputed data sets, and results were combined across imputations using Rubin rules.

As a secondary analysis, we performed subgroup analyses of patients with the oropharynx vs nonoropharynx as primary sites. We first investigated whether the covariate balance across treatment groups was preserved within each subgroup. Next, after balance was confirmed, we again performed a Cox regression of the inverse probability–weighted population to estimate the cause-specific hazard ratio of death associated with carboplatin vs cetuximab within the oropharynx and nonoropharynx subgroups.

This study followed Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guidelines. Stata, version 17 (StataCorp), was used to conduct all analyses. Statistical significance was defined as a 2-sided P value of less than .05.

Results

Cohort Description and Baseline Characteristics

The cohort comprised 8290 patients with nonmetastatic HNSCC who were treated with CRT with cisplatin (5566 [67%]), carboplatin (1231 [15%]), or cetuximab (1493 [18%]). Of an initial 9711 patients identified, we excluded 1421 (15%) because they received more than 1 type of systemic therapy during the defined follow-up period (843 patients received cisplatin and carboplatin, 366 cisplatin and cetuximab, and 212 carboplatin and cetuximab); characteristics and survival for these excluded patients are presented in eTable 2 and eFigure 2 in the Supplement. Most carboplatin-treated patients also received treatment with paclitaxel (794 [65%]); other carboplatin partners included fluorouracil (n = 99), capecitabine (n = 10), and docetaxel (n = 21). Most patients (4776 [58%]) had oropharynx primary cancer; the most common nonoropharynx primary site was larynx. The proportion of oropharynx vs nonoropharynx primary sites was similar across systemic therapy types (Table 1).

Table 1. Patient Characteristics by Systemic Therapy Agent.

| Characteristic | No. (%)a | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cisplatin | Carboplatin | Cetuximab | Total | |

| No. | 5566 | 1231 | 1493 | 8290 |

| Age, median (IQR), y | 62 (57-66) | 64 (59-69) | 66 (61-72) | 63 (58-68) |

| Sex | ||||

| Female | 66 (1.2) | 15 (1.2) | 8 (0.5) | 89 (1.1) |

| Male | 5500 (98.8) | 1216 (98.8) | 1485 (99.5) | 8201 (98.9) |

| Race and ethnicity | ||||

| Black or African American | 776 (14.8) | 193 (16.7) | 256 (18.5) | 1225 (15.8) |

| White | 4382 (83.6) | 942 (81.6) | 1100 (79.7) | 6424 (82.6) |

| Otherb | 83 (1.6) | 20 (1.7) | 25 (1.8) | 128 (1.6) |

| Missing | 325 | 76 | 112 | 513 |

| Primary site | ||||

| Oropharynx | 3218 (57.8) | 676 (54.9) | 882 (59.1) | 4776 (57.6) |

| Nonoropharynx | 2348 (42.2) | 555 (45.1) | 611 (40.9) | 3514 (42.4) |

| Married | 2073 (37.2) | 478 (38.8) | 579 (38.8) | 3130 (37.8) |

| Year of diagnosisc | ||||

| 2006-2010 | 2103 (37.8) | 529 (43.0) | 575 (38.5) | 3207 (38.7) |

| 2011-2015 | 2222 (39.9) | 462 (37.5) | 587 (39.3) | 3271 (39.5) |

| 2016-2020 | 1241 (22.3) | 240 (19.5) | 331 (22.2) | 1812 (21.9) |

| Smoking status | ||||

| Current smoker | 2369 (70.7) | 447 (67.1) | 600 (61.7) | 3416 (68.5) |

| Former smoker | 410 (12.2) | 102 (15.3) | 138 (14.2) | 650 (13.0) |

| Never smoker | 571 (17.0) | 117 (17.6) | 234 (24.1) | 922 (18.5) |

| Missing | 2216 | 565 | 521 | 3302 |

| Clinical tumor (T) stage | ||||

| 0 | 121 (2.3) | 30 (2.5) | 18 (1.3) | 169 (2.2) |

| 1 | 614 (11.8) | 134 (11.4) | 167 (11.9) | 915 (11.7) |

| 2 | 1733 (33.2) | 417 (35.4) | 437 (31.1) | 2587 (33.2) |

| 3 | 1508 (28.9) | 320 (27.2) | 437 (31.1) | 2265 (29.0) |

| 4 | 1240 (23.8) | 277 (23.5) | 344 (24.5) | 1861 (23.9) |

| Missing | 350 | 53 | 90 | 493 |

| Clinical nodal (N) stage | ||||

| 0 | 1003 (19.2) | 264 (22.4) | 306 (21.8) | 1573 (20.2) |

| 1 | 805 (15.4) | 178 (15.1) | 219 (15.6) | 1202 (15.4) |

| 2 | 3191 (61.2) | 679 (57.7) | 807 (57.5) | 4677 (60.0) |

| 3 | 219 (4.2) | 56 (4.8) | 71 (5.1) | 346 (4.4) |

| Missing | 348 | 54 | 90 | 492 |

| ECOG performance status score | ||||

| 0 | 1462 (47.3) | 239 (37.6) | 358 (40.7) | 2059 (44.7) |

| 1 | 1360 (44.0) | 295 (46.5) | 375 (42.7) | 2030 (44.1) |

| 2 | 229 (7.4) | 79 (12.4) | 114 (13.0) | 422 (9.2) |

| 3 | 36 (1.2) | 17 (2.7) | 25 (2.8) | 78 (1.7) |

| 4 | 4 (0.1) | 5 (0.8) | 7 (0.8) | 16 (0.3) |

| Missing | 2475 | 596 | 614 | 3685 |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index score | ||||

| 0 | 1860 (33.4) | 294 (23.9) | 282 (18.9) | 2436 (29.4) |

| 1 | 1275 (22.9) | 233 (18.9) | 233 (15.6) | 1741 (21.0) |

| ≥2 | 2431 (43.7) | 704 (57.2) | 978 (65.5) | 4113 (49.6) |

| Hypertension | 3618 (65.0) | 903 (73.4) | 1144 (76.6) | 5665 (68.3) |

| Hyperlipidemia | 3079 (55.3) | 746 (60.6) | 935 (62.6) | 4760 (57.4) |

| Diabetes | 997 (17.9) | 307 (24.9) | 430 (28.8) | 1734 (20.9) |

| CAD | 1136 (20.4) | 377 (30.6) | 504 (33.8) | 2017 (24.3) |

| Kidney disease | 127 (2.3) | 121 (9.8) | 204 (13.7) | 452 (5.5) |

Abbreviations: CAD, coronary artery disease; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group.

Median (interquartile range) for continuous variables; No. (percentage of nonmissing data) for categorical variables.

Includes Asian, American Indian or Alaska Native and Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander.

Because of delays in cancer registry abstraction and reporting, VA cancer registry data are only up to date to 2016, accounting for fewer than expected complete analytic cases after 2016.

Consistent with clinical practice patterns, compared with cisplatin-treated patients, patients treated with carboplatin and cetuximab were older with worse performance status and a higher comorbidity burden (Table 1). Compared with carboplatin-treated patients, cetuximab-treated patients were older (median age 66 vs 64) with a slightly higher burden of comorbidities, but were otherwise similar in cancer stage and performance status (Table 1).

Survival Analysis

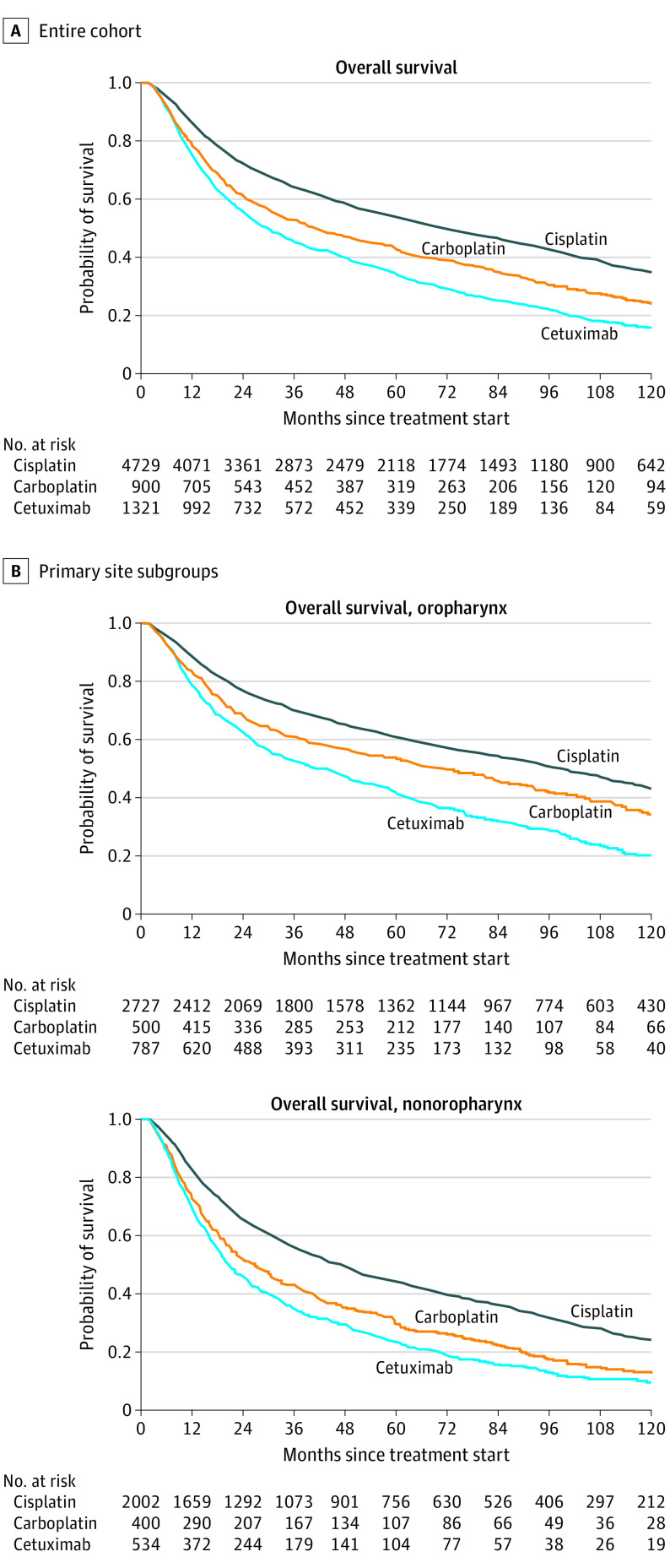

Median (IQR) overall survival was 59.3 (18.5-140.9) months in the total cohort: 74.4 (22.3-162.2) months in patients treated with cisplatin RT, 43.4 (15.3-123.8) months in patients treated with carboplatin RT, and 31.1 (12.4-87.8) months in patients treated with cetuximab RT (Figure 1A; Table 2). Patients with oropharynx cancer had better survival overall than patients with nonoropharynx cancer (median overall survival of 82.5 vs 39.5 months) (Figure 1B; Table 2).

Figure 1. Kaplan-Meier Survival Curves by Systemic Therapy and Primary Site.

Table 2. Median and 5-Year Survival by Primary Site and Systemic Therapy.

| Treatment | All sites (n = 8290) | Oropharynx (n = 4776) | Nonoropharynx (n = 3514) |

|---|---|---|---|

| All systemic therapies (n = 8290) | mOS, 59.3 mo; 5-year survival, 49.6% (95% CI, 48.5%-50.7%) | mOS, 82.5 mo; 5-year survival, 57.0% (95% CI, 55.6%-58.5%) | mOS, 39.5 mo; 5-year survival, 39.7% (95% CI, 38.0%-41.3%) |

| Cisplatin (n = 5566) | mOS, 74.4 mo; 5-year survival, 53.7% (95% CI, 52.3%-55.2%) | mOS, 99.4 mo; 5-year survival, 61.9% (95% CI, 60.1%-63.6%) | mOS, 49.7 mo; 5-year survival, 45.5% (95% CI, 43.4%-47.5%) |

| Carboplatin (n = 1231) | mOS, 43.4 mo; 5-year survival,42.9% (95% CI, 39.6%-46.2%) | mOS, 69.5 mo; 5-year survival, 53.0% (95% CI, 49.1%-56.8%) | mOS, 30.9 mo; 5-year survival, 31.8% (95% CI, 27.9%-35.8%) |

| Cetuximab (n = 1493) | mOS, 31.1 mo; 5-year survival, 34.0% (95% CI, 31.4%-36.7%) | mOS, 44.1 mo; 5-year survival, 42.2% (95% CI, 38.8%-45.6%) | mOS, 20.9 mo; 5-year survival, 24.7% (95% CI, 21.2%-28.2%) |

Abbreviation: mOS, median overall survival.

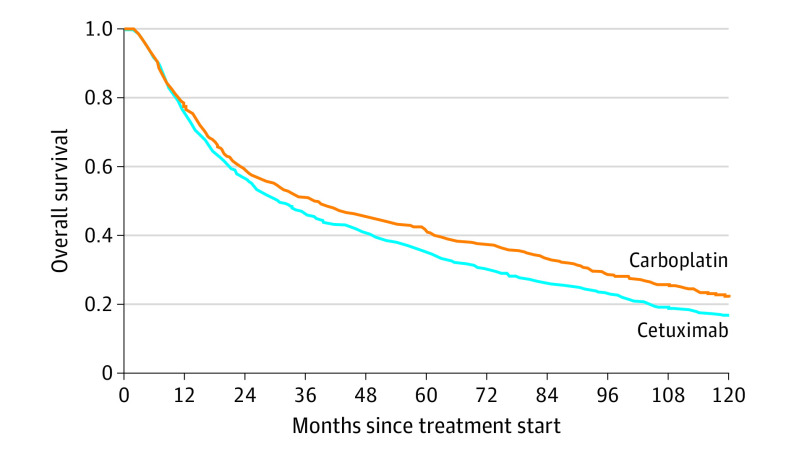

Estimated propensity scores for carboplatin-treated and cetuximab-treated populations displayed good overlap (eFigure 1 in the Supplement). After inverse probability weighting, balance between groups was achieved for all covariates, with standardized mean differences of less than 0.1 (eTable 3 in the Supplement). The inverse probability weighted cause-specific hazard ratio (csHR) of death associated with carboplatin compared with cetuximab was 0.85 (95% CI, 0.78-0.93) (Figure 2; Table 3). The proportional hazards assumption was met by Schoenfeld residual testing.

Figure 2. Weighted Kaplan-Meier Curves of Propensity Score–Based Inverse Probability–Weighted Pseudopopulations.

Table 3. Cause-Specific HRs for Death Associated With Treatment With Carboplatin Compared With Cetuximab in Propensity Score–Matched and Inverse Probability–Weighted Populations.

| Characteristic | HR (95% CI) |

|---|---|

| Entire cohort (n = 2724) | 0.85 (0.78-0.93) |

| Primary site | |

| Oropharynx (n = 1558) | 0.82 (0.72-0.94) |

| Nonoropharynx (n = 1166) | 0.88 (0.78-1.00) |

Abbreviation: HR, hazard ratio.

We next assessed the association between systemic agents and survival in the oropharynx and nonoropharynx subgroups. Covariate balance in inverse probability–weighted pseudopopulations was maintained across subgroups. Carboplatin was associated with improved survival compared with cetuximab in the oropharynx subgroup (csHR, 0.82; 95% CI, 0.72-0.94); in the nonoropharynx subgroup, survival with treatment with carboplatin was numerically but not statistically superior to cetuximab (csHR, 0.88; 95% CI, 0.78-1.00) (Figure 2; Table 3).

Discussion

Although multiple studies have shown treatment with carboplatin18 and cetuximab4,5,6,7,19,20 to be inferior to cisplatin-based CRT for HNSCC, to our knowledge, cetuximab-based and carboplatin-based CRT have never been compared in a large population-based cohort study. In more than 8000 US veterans with locally advanced HNSCC who were undergoing treatment with definitive CRT from 2006 to 2020, almost a third of patients were ineligible to receive treatment with cisplatin and received cetuximab-based or carboplatin-based radiosensitization. Most carboplatin-treated patients in the cohort also received treatment with paclitaxel, a combination with established favorable efficacy and tolerability.21,22,23 Survival estimates in cisplatin-treated patients in the cohort were comparable with outcomes in various pivotal trials of definitive CRT for HNSCC.4,24,25 Unsurprisingly, because of a combination of known inferior efficacy4,5,6,7 and patient selection factors, patients treated with noncisplatin regimens had worse survival than cisplatin-treated patients. Patients excluded because of receipt of more than 1 type of systemic therapy, many of whom first received treatment with cisplatin and then were transitioned to use of carboplatin-based or cetuximab-based therapy, displayed intermediate survival. Although we reported survival estimates for patients receiving cisplatin and noncisplatin CRT for HNSCC, the analytic focus of this study was a comparison of survival with carboplatin-based and cetuximab-based CRT.

We observed some baseline imbalances between the groups, including in age and comorbidities, which underscored the importance of accounting for baseline covariates. After achieving covariate balance with propensity score and inverse probability weighting methods, we found a 15% overall survival benefit with carboplatin-based compared with cetuximab-based CRT. Notably, this difference was primarily associated with patients with oropharynx cancer, whereas patients with nonoropharynx cancer had numerically but not statistically significantly improved survival with treatment with carboplatin compared with cetuximab. Because most oropharynx cancers in this contemporary US cohort were likely HPV-related, given epidemiologic data,26,27 this finding may reflect differential treatment efficacy by HPV status. Emerging data about decreased efficacy of cetuximab in HPV-related cancers,28 which generally express lower levels of epidermal growth factor receptor,29 may account for the observed differences in cetuximab-based vs carboplatin-based CRT outcomes in patients with oropharynx vs nonoropharynx cancer. Overall, these data support the use of carboplatin-based systemic therapy for CRT in patients who are ineligible for treatment with cisplatin.

Limitations

This retrospective analysis had several limitations. As we did not have patient-level HPV status information, we used oropharynx primary site as a proxy for HPV status. Although the US veteran population is not completely generalizable, recent analyses suggest that the proportion of HPV-positive oropharynx cancer in the veteran population is comparable with that of the general US population.30 Thus, most patients with oropharynx cancer in the contemporary cohort (patients treated from 2006-2020) likely had HPV-associated cancer. In addition, the cancer registry and administrative data sources used for this study did not allow ascertainment of neuropathy, hearing loss, treatment toxicity, or disease progression. Misclassification of primary site and treatment are possible owing to limitations of electronic health record and cancer registry documentation. Although propensity score and weighting methods were performed to account for baseline differences between the carboplatin and cetuximab groups, unmeasured confounding remains possible. Finally, there were substantial missing data in covariates, including smoking status and performance status; because these data were not missing completely at random, we used multiple imputation by chained equations, which produces unbiased estimates under missing at random missingness.17

Conclusions

To our knowledge, this cohort study presents the largest study to date comparing cetuximab-based and carboplatin-based chemoradiotherapy for cisplatin-ineligible patients with locally advanced HNSCC. For patients who are ineligible for treatment with cisplatin, carboplatin-based radiosensitization may provide better oncologic outcomes than cetuximab, particularly for oropharynx cancer.

eTable 1. Coding definitions

eTable 2. Characteristics in patients excluded due to overlapping treatment regimens

eTable 3. Pre and post inverse probability weighting covariate standardized mean differences

eFigure 1. Pre and post inverse probability weighting kernel density and box plots of propensity scores

eFigure 2. Survival in patients excluded due to overlapping treatment regimens

References

- 1.Bonner JA, Harari PM, Giralt J, et al. Radiotherapy plus cetuximab for squamous-cell carcinoma of the head and neck. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(6):567-578. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa053422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Denis F, Garaud P, Bardet E, et al. Final results of the 94-01 French Head and Neck Oncology and Radiotherapy Group randomized trial comparing radiotherapy alone with concomitant radiochemotherapy in advanced-stage oropharynx carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(1):69-76. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.08.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bourhis J, Sire C, Graff P, et al. Concomitant chemoradiotherapy versus acceleration of radiotherapy with or without concomitant chemotherapy in locally advanced head and neck carcinoma (GORTEC 99-02): an open-label phase 3 randomised trial. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13(2):145-153. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70346-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gillison ML, Trotti AM, Harris J, et al. Radiotherapy plus cetuximab or cisplatin in human papillomavirus-positive oropharyngeal cancer (NRG Oncology RTOG 1016): a randomised, multicentre, non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2019;393(10166):40-50. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32779-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mehanna H, Robinson M, Hartley A, et al. ; De-esclate HPV Trial Group . Radiotherapy plus cisplatin or cetuximab in low-risk human papillomavirus-positive oropharyngeal cancer (De-ESCALaTE HPV): an open-label randomised controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2019;393(10166):51-60. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32752-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gebre-Medhin M, Brun E, Engström P, et al. ARTSCAN III: a randomized phase III study comparing chemoradiotherapy with cisplatin versus cetuximab in patients with locoregionally advanced head and neck squamous cell cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2021;39(1):38-47. doi: 10.1200/JCO.20.02072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rischin D, King MT, Kenny LM, et al. Randomized trial of radiotherapy with weekly cisplatin or cetuximab in low risk HPV associated oropharyngeal cancer (TROG 12.01): a Trans-Tasman Radiation Oncology Group study. J Clin Oncol. 2021;39(15)(suppl):6012-6012. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2021.39.15_suppl.6012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barney C, Healy E, Zamora P, et al. Carboplatin versus cetuximab chemoradiation in cisplatin ineligible patients with locally advanced p16 negative head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2017;99(2):E322-E323. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2017.06.1372 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thanikachalam K, Krishnan J, Siddiqui F, Ali HY, Sheqwara J. Carboplatin versus cetuximab chemoradiation in cisplatin ineligible locally advanced head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(15)(suppl):e18555-e18555. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2020.38.15_suppl.e18555 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hamauchi S, Yokota T, Mizumachi T, et al. Safety and efficacy of concurrent carboplatin or cetuximab plus radiotherapy for locally advanced head and neck cancer patients ineligible for treatment with cisplatin. Int J Clin Oncol. 2019;24(5):468-475. doi: 10.1007/s10147-018-01392-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Beckham TH, Barney C, Healy E, et al. Platinum-based regimens versus cetuximab in definitive chemoradiation for human papillomavirus-unrelated head and neck cancer. Int J Cancer. 2020;147(1):107-115. doi: 10.1002/ijc.32736 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shapiro LQ, Sherman EJ, Riaz N, et al. Efficacy of concurrent cetuximab vs. 5-fluorouracil/carboplatin or high-dose cisplatin with intensity-modulated radiation therapy (IMRT) for locally-advanced head and neck cancer (LAHNSCC). Oral Oncol. 2014;50(10):947-955. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2014.07.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Orkaby AR, Nussbaum L, Ho Y-L, et al. The burden of frailty among U.S. veterans and its association with mortality, 2002-2012. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2019;74(8):1257-1264. doi: 10.1093/gerona/gly232 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fryar CD, Herrick K, Afful J, Ogden CL. Cardiovascular disease risk factors among male veterans, U.S., 2009-2012. Am J Prev Med. 2016;50(1):101-105. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2015.06.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Assari S. Veterans and risk of heart disease in the United States: a cohort with 20 years of follow up. Int J Prev Med. 2014;5(6):703-709. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mashberg A, Boffetta P, Winkelman R, Garfinkel L. Tobacco smoking, alcohol drinking, and cancer of the oral cavity and oropharynx among U.S. veterans. Cancer. 1993;72(4):1369-1375. doi: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.White IR, Royston P, Wood AM. Multiple imputation using chained equations: Issues and guidance for practice. Stat Med. 2011;30(4):377-399. doi: 10.1002/sim.4067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guan J, Li Q, Zhang Y, et al. A meta-analysis comparing cisplatin-based to carboplatin-based chemotherapy in moderate to advanced squamous cell carcinoma of head and neck (SCCHN). Oncotarget. 2016;7(6):7110-7119. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.6858 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Strom TJ, Trotti AM, Kish J, et al. Comparison of every 3 week cisplatin or weekly cetuximab with concurrent radiotherapy for locally advanced head and neck cancer. Oral Oncol. 2015;51(7):704-708. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2015.04.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Riaz N, Sherman E, Koutcher L, et al. Concurrent chemoradiotherapy with cisplatin versus cetuximab for squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Am J Clin Oncol. 2016;39(1):27-31. doi: 10.1097/COC.0000000000000006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Haddad R, Sonis S, Posner M, et al. Randomized phase 2 study of concomitant chemoradiotherapy using weekly carboplatin/paclitaxel with or without daily subcutaneous amifostine in patients with locally advanced head and neck cancer. Cancer. 2009;115(19):4514-4523. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24525 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vlacich G, Diaz R, Thorpe SW, et al. Intensity-modulated radiation therapy with concurrent carboplatin and paclitaxel for locally advanced head and neck cancer: toxicities and efficacy. Oncologist. 2012;17(5):673-681. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2011-0396 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Semrau R, Temming S, Preuss SF, Klubmann JP, Guntinas-Lichius O, Müller RP. Definitive radiochemotherapy of advanced head and neck cancer with carboplatin and paclitaxel: a phase II study. Strahlenther Onkol. 2011;187(10):645-650. doi: 10.1007/s00066-011-1111-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nguyen-Tan PF, Zhang Q, Ang KK, et al. Randomized phase III trial to test accelerated versus standard fractionation in combination with concurrent cisplatin for head and neck carcinomas in the Radiation Therapy Oncology Group 0129 trial: long-term report of efficacy and toxicity. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(34):3858-3866. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.55.3925 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ang KK, Harris J, Wheeler R, et al. Human papillomavirus and survival of patients with oropharyngeal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(1):24-35. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0912217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chaturvedi AK, Engels EA, Pfeiffer RM, et al. Human papillomavirus and rising oropharyngeal cancer incidence in the United States. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(32):4294-4301. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.36.4596 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lechner M, Liu J, Masterson L, Fenton TR. HPV-associated oropharyngeal cancer: epidemiology, molecular biology and clinical management. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2022;19(5):306-327. doi: 10.1038/s41571-022-00603-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kochanny SE, Worden FP, Adkins DR, et al. A randomized phase 2 network trial of tivantinib plus cetuximab versus cetuximab in patients with recurrent/metastatic head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer. 2020;126(10):2146-2152. doi: 10.1002/cncr.32762 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Keck MK, Zuo Z, Khattri A, et al. Integrative analysis of head and neck cancer identifies two biologically distinct HPV and three non-HPV subtypes. Clin Cancer Res. 2015;21(4):870-881. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-2481 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shay SG, Chang E, Lewis MS, Wang MB. Characteristics of human papillomavirus–associated head and neck cancers in a veteran population. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2015;141(9):790-796. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2015.1447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable 1. Coding definitions

eTable 2. Characteristics in patients excluded due to overlapping treatment regimens

eTable 3. Pre and post inverse probability weighting covariate standardized mean differences

eFigure 1. Pre and post inverse probability weighting kernel density and box plots of propensity scores

eFigure 2. Survival in patients excluded due to overlapping treatment regimens