Abstract

The multicopy subunit c of the H+-transporting F1Fo ATP synthase of Escherichia coli folds across the membrane as a hairpin of two hydrophobic α helices. The subunits interact in a front-to-back fashion, forming an oligomeric ring with helix 1 packing in the interior and helix 2 at the periphery. A conserved carboxyl, Asp61 in E. coli, centered in the second transmembrane helix is essential for H+ transport. A second carboxylic acid in the first transmembrane helix is found at a position equivalent to Ile28 in several bacteria, some the cause of serious infectious disease. This side chain has been predicted to pack proximal to the essential carboxyl in helix 2. It appears that in some of these bacteria the primary function of the enzyme is H+ pumping for cytoplasmic pH regulation. In this study, Ile28 was changed to Asp and Glu. Both mutants were functional. However, unlike the wild type, the mutants showed pH-dependent ATPase-coupled H+ pumping and passive H+ transport through Fo. The results indicate that the presence of a second carboxylate enables regulation of enzyme function in response to cytoplasmic pH and that the ion binding pocket is aqueous accessible. The presence of a single carboxyl at position 28, in mutants I28D/D61G and I28E/D61G, did not support growth on a succinate carbon source. However, I28E/D61G was functional in ATPase-coupled H+ transport. This result indicates that the side chain at position 28 is part of the ion binding pocket.

F1Fo ATP synthases catalyze the formation of ATP by utilizing the energy of a transmembrane electrochemical gradient (reviewed in reference 3). H+ and Na+ translocating complexes exist. Closely related ATP synthases are found in the plasma membrane of eubacteria, the inner membrane of mitochondria, and the thylakoid membrane of chloroplasts. The enzyme is a multisubunit complex with distinct extramembranous and transmembrane domains, termed F1 and Fo, respectively. In Escherichia coli, the F1 sector is composed of five subunits in an α3β3γδɛ stoichiometry. Homologous subunits are found in mitochondria and chloroplasts. A high-resolution structure of the α3β3γ portion of bovine F1 shows the three α and three β subunits to alternate around the central γ subunit (1). Ion movement through Fo is coupled to ATP synthesis and hydrolysis at sites in F1.

The E. coli Fo consists of three types of subunits with a stoichiometry of a1b2c10–12 (12, 18). The c subunits of Fo are arranged in an oligomeric ring (7, 19). Subunit c folds in the membrane as a hairpin of two hydrophobic α helices connected by a polar loop on the F1 binding side of the membrane (14). The arrangement and interaction of subunits in E. coli is supported by a 4-Å resolution X-ray diffraction density map of an F1-c10 subcomplex purified from yeast mitochondria (40). A conserved and essential Asp or Glu (Asp61 in E. coli) is centered in the second transmembrane helix of subunit c. The conserved carboxylate catalyzes ion movement via interaction with subunit a, a key residue being an arginine (Arg210 in E. coli) in a transmembrane segment. Such data have supported mechanistic models where ion movement occurs at the interface between subunits a and c through rotation of the subunit c oligomeric ring and subunits γ and ɛ within F1 (reviewed in references 3, 10, and 41).

In the model of the oligomeric c ring, the Asp61 side chain is positioned within a four-helix bundle formed by the front and back faces of two adjacent monomers (see Fig. 5A) (7, 19). The ion binding pocket in the subunit c ring is predicted to be lined by side chains at positions equivalent to 24, 28, and 62, which surround the essential carboxyl at position 61, in E. coli. Interestingly, numerous sequences of subunit c from a wide variety of sources possess polar residues at all or some of these positions.

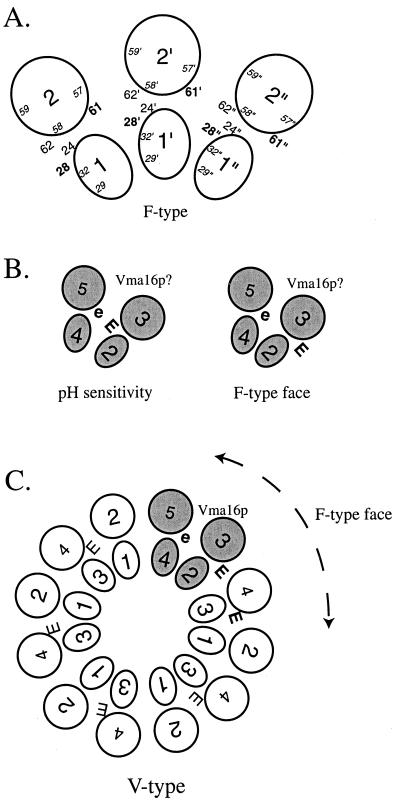

FIG. 5.

Models of positions of the carboxyl groups and neighboring residues in the subunit c oligomer of the F- and V-type ATPases. (A) Schematic representation of a section of the arrangement of the oligomeric ring of subunit c of E. coli, modified from Jones et al. (19). Helices from each subunit are labeled 1 and 2, and neighboring individual subunits and their residues are indicated by a single or double primes. The relative positions of residues surrounding the essential Asp61 are shown. (B) Hypothetical arrangement of the V-type ATPase Vma16p and relative positions of the two carboxyl groups based on the model of the E. coli oligomeric ring as shown in panel A. The packing of helices 2 and 3 with respect to helices 4 and 5 is based on the E. coli data (19) and cross-linking studies by Harrison et al. (15). Two of several possible arrangements and their functional implications are shown. (C) Schematic model of the V-type subunit c oligomeric ring, with the position of Vma16p indicated. Formation of the F-type like face is depicted. E and e represent the essential carboxyl group and the carboxyl group at position 188, respectively.

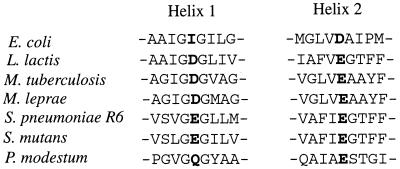

A second carboxyl side chain at a position equivalent to Ile28 is found in several bacteria (Fig. 1). Several of these bacteria, e.g., Mycobacterium tuberculosis, Mycobacterium leprae, and Streptococcus pneumoniae, are the cause of serious infectious disease. In addition, studies of S. pneumoniae indicate that some antimalarials target the ion binding site in subunit c and that this or the related vacuolar protein is a likely target in the etiological agent Plasmodium falciparum (9). In some streptococci and other lactic acid bacteria, the primary function of the enzyme is as an H+-pumping ATPase for cytoplasmic pH regulation, maintaining a transmembrane pH gradient with a cytoplasmic pH near neutrality when the extracellular pH is low (2, 6, 24; reviewed in references 23 and 30). In Streptococcus mutans, the activity of the F1Fo ATPase appears to be regulated by intracellular pH (6).

FIG. 1.

Some of the c subunits that have a carboxylic acid at a position equivalent to Ile28 in E. coli. Sequence comparison around residues equivalent to Ile28 and Asp61 in E. coli is shown. The sequences compared were from E. coli (42), Lactococcus lactis (25), M. tuberculosis (4), M. leprae (39), S. pneumoniae R6 (9), S. mutans (38), and Propionigenium modestum (8). P. modestum is included to show the polar residues at positions equivalent to 28, 61, and 62 that are essential for Na+ binding (21). Positions equivalent to 28 in helix 1 and position 61 in helix 2 of E. coli are in boldface.

In this study, replacement of Ile28 of the E. coli F1Fo ATP synthase subunit c with Asp and Glu was investigated. Both changes produced a pH-dependent function. The result suggests that the second carboxyl in some bacteria could be important for regulation of enzyme function in response to cytoplasmic pH. The presence of a single carboxyl in subunit c at position 28, in constructs I28D/D61G and I28E/D61G, did not allow growth on succinate as a carbon source. However, I28E/D61G was functional in ATPase-coupled H+ transport.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and plasmids.

The plasmids used in this study are derivatives of plasmid pDF163, which contains the wild-type (WT) uncBEFH genes (bases 870 to 3216, encoding subunits a, c, b, and δ) cloned between the HindIII and SphI sites of plasmid pBR322 (13). Plasmids pI28D and pI28E were constructed by a rapid site-directed mutagenesis procedure (26). An antisense oligonucleotide, 5′-ACCCCCGAGGATGCCT/ATCACCGATCGCAGCACC-3′, corresponding to subunit c positions G23 to G33, was synthesized to incorporate base changes (boldface) to create an Asp or Glu codon at position 28 and to overlap the nearby AvaI restriction enzyme site (italics). PCR was then performed with this primer and a sense oligonucleotide primer designed to the coding strand (bases 1540 to 1560), upstream of the PstI restriction enzyme site (1561 to 1566), using plasmid pDF163 DNA as the template. The PCR product was then digested with restriction enzymes PstI and AvaI and ligated to the equivalent sites of plasmid pDF163 to generate plasmid pI28D or pI28E. The I28D/D61G and I28E/D61G double substitutions were generated by subcloning a PstI/AvaI fragment from either plasmid pI28D or plasmid pI28E into the corresponding sites of plasmid pLH247 (32), a plasmid pDF163 derivative containing the subunit c D61G substitution. All constructs were confirmed by restriction mapping and sequencing. The chromosomal uncBEFH deletion strain, JWP109 (pyrE41 entA403 argH1 rspsL109 supE44 ΔuncBEFH) (17), was transformed with the plasmids. Complementation of the unc phenotype (lack of growth on succinate) was tested by transferring transformant, ampicillin-resistant colonies to minimal medium 63 plates containing 22 mM succinate, 2 mg of thiamine/liter, 0.2 mM uracil, 0.2 mM l-arginine, 20 μM dihydroxybenzoic acid, and 100 mg of ampicillin/liter (31).

Membrane preparations and biochemical assays.

Inside-out membrane vesicles, F1 head group on the outer face, were prepared and stored in TMDG buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM dithiothreitol, 10% [vol/vol] glycerol) at 20 mg/ml after passage of cells through a French press (43). F1-lacking stripped membranes were prepared by centrifugation and incubation of whole membranes at 5 mg/ml in TEDG buffer (1 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8], 0.5 mM Na2EDTA, 1 mM dithiothreitol, 10% [vol/vol] glycerol) for 30 min at 30°C, followed by centrifugation and one wash with TEDG buffer. Protein concentration was determined by using a Pierce bicinchoninic acid assay kit with the addition of 0.01% sodium dodecyl sulfate. ATPase activity was assayed in HMK buffer (10 mM HEPES-KOH [pH as indicated], 5 mM MgCl2, 300 mM KCl) using 25 μg (total protein) of membranes and 5 mM ATP by measuring inorganic phosphate release (28). ATP-driven 9-amino-6-chloro-2-methoxyacridine (ACMA) quenching and NADH-driven quinacrine quenching assays were carried out in HMK assay buffer as described previously (43). Membranes were incubated in HMK assay buffer for 15 min in the presence of 45 μM N,N′-dicyclo hexylcarbodiimide (DCCD) prior to addition of NADH to test its effect on NADH-driven quenching. The rate of NADH oxidation was determined by absorbance change at a wavelength of 340 nm, using 100 μM NADH and 50 μg of whole membranes/ml in HMK buffer (pH 7.0). ATP synthesis was carried out as described by Schulenberg and Capaldi (37), with the pH of the Tris buffer and reaction buffer varied accordingly. All reactions were carried out at room temperature. The values reported are averages of triplicate assays, and quenching curves are representative of several independent experiments.

RESULTS

Effect of I28X substitutions on function.

Asp and Glu were introduced at position 28 in subunit c and into a D61G mutant. The modified c subunits were expressed from a plasmid carrying the uncBEFH genes, encoding subunits a, c, b, and δ of F1Fo respectively, and transformed into the ΔuncBEFH strain JWP109. Growth of transformants was tested on succinate minimal medium, where growth depends on a functional oxidative phosphorylation system. The growth properties, ATPase activities, and rates of NADH oxidation of isolated inside-out membranes are shown in Table 1. Both I28x mutants grew on succinate. The I28E mutant grew similarly to the wild type, whereas the I28D mutant grew less well. The I28D/D61G and I28E/D61G mutants did not grow on succinate minimal medium. The levels of expression of subunit c as determined by immunoblot analysis from each mutant were similar (data not shown).

TABLE 1.

Growth properties and activity assays

| Constructa | Growth on succinateb | ATPase activity (μmol min−1 mg−1)c

|

Rate of NADH oxidationc (μmol min−1 mg−1) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| pH 7.0 | pH 8.0 | |||

| WT | 2.0 | 0.412 | 0.134 | 1.03 |

| 128D | 0.5 | 0.122 | 0.101 | 1.21 |

| I28E | 2.0 | 0.161 | 0.100 | 0.98 |

| I28D/D61G | 0 | 0.135 | 0.089 | 0.88 |

| I28E/D61G | 0 | 0.192 | 0.126 | 1.07 |

| D61G | 0 | 0.165 | 0.074 | 0.76 |

See text for descriptions.

Colony size after 72 h of incubation at 37°C on minimal medium plates containing 22 mM succinate.

Average of triplicate assays. The percentage difference between individual assays and the average was less than 5% in all cases.

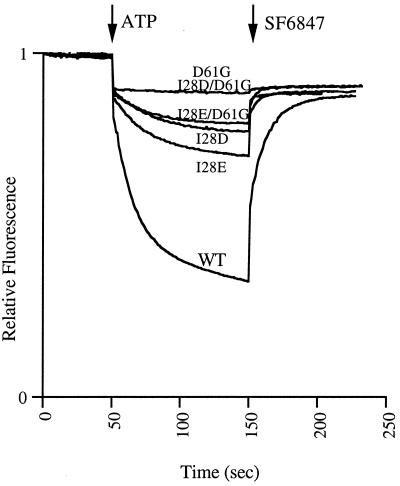

All membranes showed an NADH-driven quenching of quinacrine fluorescence equivalent to that of WT membranes (data not shown). The reduced ATP-driven quenching response therefore cannot be a result of enhanced H+ permeability of these membranes. The ATPase activity of WT membranes at pH 7.0 was only two- to threefold greater than that of the mutant membranes (Table 1). There appears to be little correlation between ATPase activity at these levels and H+ pumping. Greater differences between WT and mutant subunit c membranes have been reported previously and at lower levels of activity are capable of maximal ATP-driven quenching (43). At pH 8.0, the ATPase activities of all membranes were lower but similar, with the WT membranes still reaching a near-maximal ATP-driven H+ pumping response.

All mutants showed a reduced or inhibited ATP-driven ACMA quenching response. The response of the I28E mutant membranes was the least affected but was still reduced to approximately 35% of the WT membrane level (Fig. 2). This is somewhat surprising, as this mutant grew as robustly as the wild type on a succinate carbon source. The rates of ATP synthesis were also equivalent at both pH 7.0 and pH 8.0. The rates for WT and I28E mutant membranes at pH 7.0 were 40.0 and 40.5 nmol min−1 mg−1, respectively, and at pH 8.0 were 39.1 and 39.4 nmol min−1 mg−1, respectively. The ATP-driven ACMA quenching response of the I28D and I28E/D61G mutants was greatly reduced, the I28D mutant having a response approximately 20 to 30% of that of the I28E mutant at an equivalent amount of membranes used. To aid investigation, twice as much of these membranes as of the WT and I28E mutant membranes was analyzed, thus obtaining an approximately twofold increase in the response. The I28E/D61G mutant membranes showed a significant quenching response even though the activity was insufficient to support growth by oxidative phosphorylation. The cell culture from which these membranes were derived was devoid of succinate-positive revertants.

FIG. 2.

Comparison of ATP-driven quenching of ACMA fluorescence by WT and mutant membranes. WT and 128E mutant membranes were diluted to 0.25 mg/ml, and the others were diluted to 0.5 mg/ml, in HMK buffer (pH 7.0) containing 0.3 μg of ACMA/ml. At the times indicated, ATP was added to 0.94 mM and uncoupler SF6847 was added to 0.3 μM. WT denotes I28/D61.

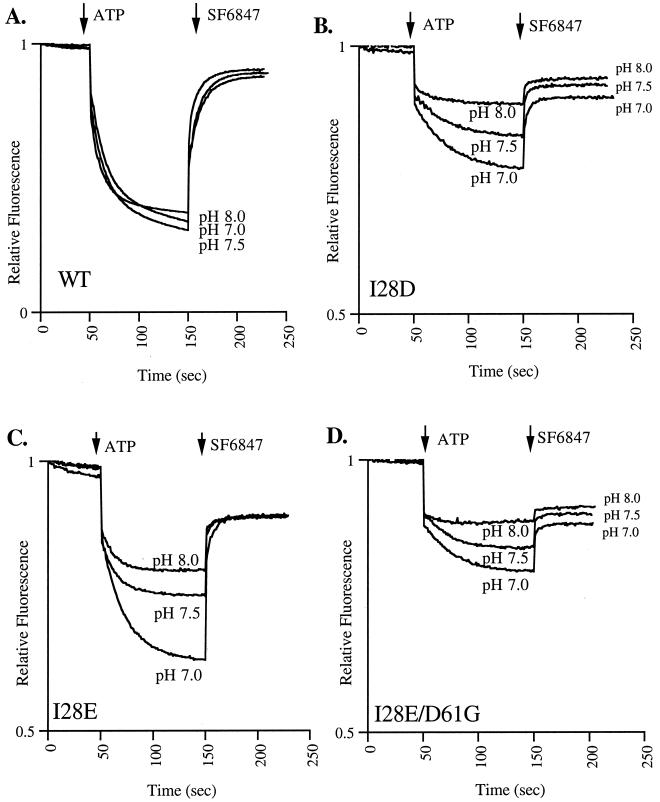

H+ pumping by the wild type was relatively insensitive to the pH of the buffer (Fig. 3A). In fact, the response was slightly higher at pH 7.5 than at pH 7.0; at pH 8.0, there was a slight decrease. In contrast, the I28D, I28E, and I28E/D61G mutants showed a pH dependence of ATP-driven H+ pumping (Fig. 3). The ATP-driven quenching response decreased with increasing pH. A striking difference was observed between pH 7.0 and 7.5 for the I28E mutant (Fig. 3C). The response at pH 6.75 was equivalent to that at pH 7.0 for all membranes. The effect at pH 8.0 was fully reversible (data not shown).

FIG. 3.

Comparison of ATP-driven quenching of ACMA fluorescence by WT and mutant membranes at various pHs. Conditions were as described for Fig. 2, apart from the pH of the buffer. Note that twice as much I28D and I28E/D61G mutant membranes as other membranes were used.

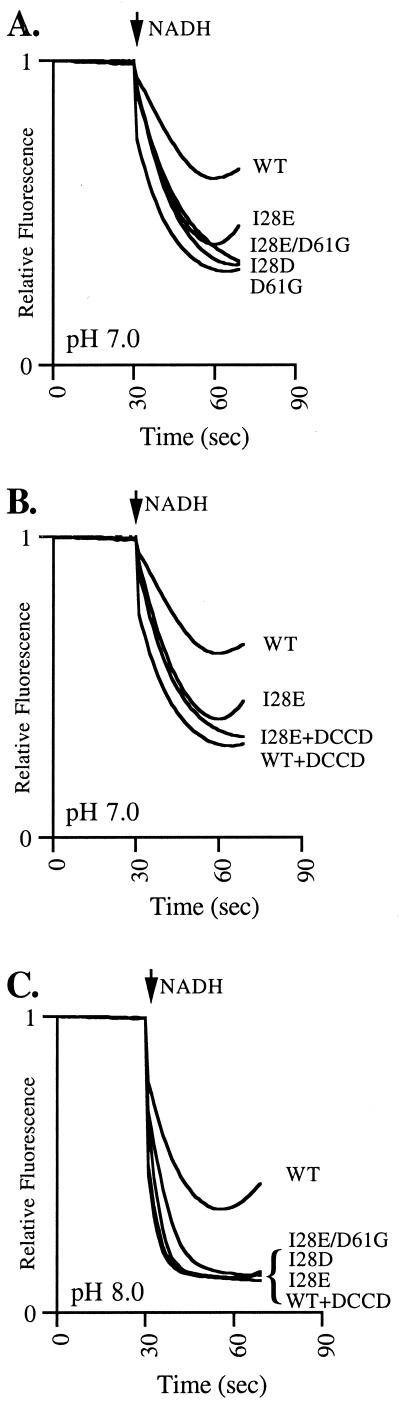

The passive H+ permeability of stripped membranes, where F1 is removed from the complex, was examined at pH 7.0 (Fig. 4A and B) and pH 8 (Fig. 4C). WT stripped membranes showed reduced NADH-driven quenching responses at pH 7.0 and 8.0 in comparison to the controls, indicating that the membranes were H+ permeable and contained an F0 functional in H+ transport. A much larger quenching response was observed for the control stripped DCCD-inhibited WT and D61G mutant membranes due to the inability of Fo to transport H+ (Fig. 4A and B). A large quenching response was observed with I28D, I28E/D61G, and I28D/D61G (not shown) stripped membranes at pH 7.0, indicating little H+ movement through Fo. DCCD treatment of these membranes had no observable effect (data not shown). The stripped I28E mutant membranes produced a reduced quenching response at pH 7.0. DCCD treatment of the stripped I28E mutant membranes enhanced the quenching response, confirming that H+ movement occurred through Fo (Fig. 4B). In contrast, all stripped mutant membranes showed close to a maximal NADH-driven quenching response at pH 8.0 (Fig. 4C). The effect on the I28E mutant clearly shows that H+ transport through Fo is pH dependent. The impaired H+ transport through F0 of the mutant membranes correlates well with the effects on ATP-driven H+ pumping discussed above.

FIG. 4.

Effect of pH on H+ transport through F0 by NADH-driven quenching of quinacrine fluorescence. Stripped membranes were diluted to 0.1 mg/ml in HMK buffer (pH as indicated) containing 0.375 μg of quinacrine/ml. NADH was added to a final concentration of 200 μM at the time indicated. The reversal of quenching is due to consumption of NADH in the cuvette. DCCD-treated membranes are labeled (+DCCD).

DISCUSSION

Effects and implications of a second carboxyl group.

In some bacteria, a second carboxylic acid is found at a position equivalent to Ile28 in E. coli (Fig. 1 and 5A). In this study, alteration of Ile28 to Asp or Glu resulted in functional enzymes that show pH-dependent function (Fig. 3 and 4). The I28E mutant grew similarly to the wild type and had a greater ATP-driven H+ pumping response than the I28D mutant. The pH dependence of function is similar to observations seen on an A24D mutant by Zhang and Fillingame (43). As these authors suggest, the effect of pH on the rate of H+ movement through Fo is likely to limit ATPase-coupled H+ transport. The results here suggest that the presence of the second carboxyl, at a position equivalent to 28 in E. coli, may be important for regulation of enzyme function in response to cytoplasmic pH. The presence of a second carboxyl reduces H+ pumping activity when the intracellular pH is above neutrality. In S. mutans, which has this additional carboxyl group, the F1Fo ATPase appears to regulate intracellular pH but not above pH 7.5 (6). The effect of replacing the carboxylic acid at the equivalent position in S. mutans and other bacteria requires investigation.

The effect of pH on the cytoplasmic facing side on H+ movement has been mimicked. The pH sensitivity suggests that the carboxyl group, or ion binding cavity, is accessible to the cytoplasm. The ion cavity is positioned within the lipid bilayer (20, 40). Hence, the pH sensitivity of the mutants support the idea of aqueous exit/entry channels within subunit a and/or at the interface between it and subunit c. Deprotonation of the second carboxyl group at higher pH may inhibit movement at the subunit a and c interface. The lack of effect of pH on ATP synthesis, and growth equivalent to WT growth on succinate, in the I28E mutant is interesting. This could be because the events at the ion binding site, as a result of pH change, are not rate limiting during synthesis. However, it may correlate with a model where the pKa of the essential carboxyl group in each half channel switches between a high and low value according to the mode of the enzyme.

Analysis of subunit a has given some insights into likely regions of interaction with subunit c (10, 41). In the proposed transmembrane span 2, there is the potential for a net negative charge (−2) from the residues that fall on the half facing the periplasm, and it has been suggested that they may make up part of an aqueous channel (10, 41). However, in S. mutans, where the primary role appears to be cytoplasmic H+ extrusion, the residues at equivalent positions appear to have been replaced so that there is a net positive charge (e.g., D119→G, insertion between 122/123→K, D124→Q, L126→K, and P127→D). This region incorporates a repeat of residues DLLP in E. coli, which is altered in S. mutans by the aforementioned changes, and has been linked with functional importance (27). Intriguingly, the sequence DAIP is found at the H+ binding site in E. coli subunit c, and there also appears to be homology in the flanking sequence. These changes may be rationalized if this region is part of the periplasmic facing channel, where the primary role in S. mutans is H+ release.

Switching the essential carboxyl group to helix 1.

The I28E/D61G mutant, but not the I28D/D61G mutant, showed H+ pumping activity despite the inability of both to support growth by oxidative phosphorylation (Fig. 2). The function of the I28E/D61G mutant may relate to the greater side chain length placing the carboxyl group at a more optimal position toward the center of the pocket or a slight variation in the pKa of side chain carboxyl. The reduced H+ pumping activity appears to be pH sensitive in this mutant, which implies that the effects seen on the double-carboxyl mutants are a direct result of changes in the ionization of this side chain. The mutation causes a lack of growth on succinate and a large reduction in H+ pumping activity, and so the significance is difficult to assess.

The H+ pumping ability of the I28E/D61G mutant leads to the possibility that in the I28E and I28D mutants, both carboxyls undergo protonation and deprotonation during catalytic turnover. The switching of the essential carboxyl group to the inner helix, at position 24, with retention of function has been previously described (32). The ability of a single carboxyl group present on helix 1 to retain function seems to be at odds with mechanisms involving entire rotations of helix 2 (17, 35). Ion binding and release between subunits a and c may occur through only subtle local side chain and backbone movement.

Two carboxyl groups in transmembrane helices of subunit c are found in several pathogenic bacteria and in the related vacuolar ATPase.

A second carboxylic acid, at a position equivalent to Ile28 in E. coli, is found in several pathogenic bacteria (Fig. 1). Studies of S. pneumoniae indicate that the antimalarial agents quinine and optochin target subunit c (9, 34). Quinine- and optochin-resistant mutants were found to have single replacements at positions equivalent to 29, 32, 57, 58, and 59 in E. coli. No mutants with replacement of either of the carboxylic acids have been identified. In the models of the E. coli oligomeric subunit c ring, these positions all fall around Asp61 and Ile28, i.e., the ion binding pocket. Positions 57 and 58 are near positions 28 and 61 (Fig. 5A). As several other pathogenic bacterial species, such as M. tuberculosis, M. leprae, and pathogenic oral bacteria, possess these two carboxylic acids, it is tempting to speculate that the ion binding cavity of subunit c could be a valuable target for future therapeutic drugs.

Studies of S. pneumoniae have led to the suggestion that the primary target for quinine in P. falciparum could be the subunit c of either the mitochondrial F1F0 ATP synthase or the V1V0 ATPase (34). This is germane to the data presented here, as recent studies indicate that P. falciparum has a plasma membrane V1V0 ATPase that is responsible for regulation of cytoplasmic pH (36).

The V-type ATPase has a homologous subunit c composed of four transmembrane helices that seem to have evolved by duplication of a progenitor gene (29). Each V-type subunit c has only a single essential carboxylate in one of the two helical hairpins, lowering the H+/ATP ratio to presumably enable ATP-driven H+ pumping to generate greater electrochemical gradients while preserving structural features of the complex (5). Two homologues, Vma11p and Vma16p, have been found and shown to be essential for activity in yeast (16). The Vma16p subunit c has two carboxylates in helices 3 and 5 that are equivalent to helix 2 in the F-type subunit c. The second carboxylate (E188) appears not to be essential for activity (16). It falls in the last helix at a position similar to that of Ile28 in the E. coli subunit c. The carboxylate may lie in the ion binding cavity proximal to the essential carboxylate; hence, protonation and deprotonation could play a role in pH sensitivity as described above (Fig. 5B). V1 and V0 reassembly has been shown to be pH dependent (22). Deprotonation of E188 at alkaline pH could prevent reassembly, possibly via long-range perturbations through the cytoplasmic loops. As the cytoplasmic pH falls, protonation of this carboxylate could then allow reassembly and activity. The carboxylates in Vma16p could also be positioned so as to generate neighboring ion binding sites that will form an F-type subunit c-like face if the subunits are arranged similarly to the F0 c ring (Fig. 5C) (19). In this arrangement, the potential for H+ movement is evident via a limited forward-and-backward idling motion at this face or inhibition via a variation in the pKa of the carboxylates (see above). The models can provide a mechanistic explanation for the “slip” mechanism (33), variable H+-ATP coupling modulation, by allowing an uncoupling between H+ movement and ATP hydrolysis.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I express a special thanks to John Walker for his support. Plasmids pDF163 and pLH247 and strain JWP109 were a kind gift from Robert Fillingame and group.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abrahams J P, Leslie A G W, Lutter R, Walker J E. Structure at 2.8 Å resolution of F1-ATPase from bovine heart mitochondria. Nature. 1994;370:621–628. doi: 10.1038/370621a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Amachi S, Ishikawa K, Toyoda S, Kagawa Y, Yokota A, Tomita F. Characterization of a mutant of Lactococcus lactis with reduced membrane bound ATPase activity under acidic conditions. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 1998;62:1574–1580. doi: 10.1271/bbb.62.1574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boyer P D. The ATP synthase —a splendid molecular machine. Annu Rev Biochem. 1997;66:717–749. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.66.1.717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Coles S T, Brosch R, Parkhill J, Garnier T, Churcher C, Harris D, Gordon S V, Eiglmeier K, Gas S, Barry C E, Tekaia F, Badcock K, Basham K, Brown K, Chillingworth T, Connor R, Davies R, Devlin K, Feltwell T, Gentles S, Hamlin N, Holroyd S, Hornsby T, Jagels K, Krogh A, Mclean J, Moule S, Murphy L, Oliver K, Osborne J, Quail M A, Rajandream M-A, Rogers J, Rutter S, Seeger K, Skelton J, Squares R, Squares S, Sulston J E, Taylor K, Whitehead S, Barrel B G. Deciphering the biology of Mycobacterium tuberculosis from the complete genome sequence. Nature. 1998;393:537–544. doi: 10.1038/31159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cross R L, Taiz L. Gene duplication as a means for altering H+/ATP ratios during the evolution of FoF1 ATPases and synthases. FEBS Lett. 1990;259:227–229. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(90)80014-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Daspher S G, Reynolds E C. pH regulation by Streptococcus mutans. J Dent Res. 1992;71:1159–1165. doi: 10.1177/00220345920710050601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dmitriev O Y, Jones P C, Fillingame R H. Structure of the subunit c oligomer in the F1Fo ATP synthase: model derived from solution structure of the monomer and cross-linking in the native enzyme. Proc Natl Acac Sci USA. 1999;96:7785–7790. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.14.7785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Esser U, Krumholz L R, Simoni R D. Nucleotide sequence of the Fo subunits of the sodium dependent F1Fo ATPase of Propionigenium modestum. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990;18:5887. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.19.5887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fenoll A, Munoz R, Garcia E, de la Campa A G. Molecular basis of the optochin-sensitive phenotype of pneumococcus: characterization of the genes encoding the Fo complex of the Streptococcus pneumoniae and Streptococcus oralis H+-ATPases. Mol Microbiol. 1994;12:587–598. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb01045.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fillingame R H, Jiang W, Dmitriev O Y, Jones P C. Structural interpretations of Fo rotary function in the Escherichia coli F1Fo ATP synthase. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2000;1458:387–403. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2728(00)00089-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fillingame R H, Jones P C, Jiang W, Valiyaveetil F I, Dmitriev O Y. Subunit organization and structure in the Fo sector of Escherichia coli F1Fo ATP synthase. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1998;1365:135–142. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2728(98)00053-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Foster D L, Fillingame R H. Stoichiometry of subunits in the H+-ATPase complex of Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 1982;257:2009–2015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fraga D, Fillingame R H. Conserved polar loop region of Escherichia coli subunit c of the F1Fo H+-ATPase. Glutamine 42 is not absolutely essential, but substitutions alter binding and coupling of F1 to Fo. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:6797–6803. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Girvin M E, Rastogi V K, Abildgaard F, Markley J L, Fillingame R H. Solution structure of the transmembrane H+-transporting subunit c of the F1Fo ATP synthase. Biochemistry. 1998;37:8817–8824. doi: 10.1021/bi980511m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Harrison M A, Murray J, Powell B, Kim Y-I, Finbow M E, Findlay J B C. Helical interactions and membrane disposition of the 16-kDa proteolipid subunit of the vacuolar H+-ATPase analyzed by cysteine replacement mutagenesis. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:25461–25470. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.36.25461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hirata R, Graham L A, Takatsuki A, Stevens T H, Anraku Y. VMA11 and VMA16 encode second and third proteolipid subunits of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae vacuolar H+-ATPase. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:4795–4803. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.8.4795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jiang W, Fillingame R H. Interacting helical faces of subunits a and c in the F1Fo ATP synthase of Escherichia coli defined by disulfide cross-linking. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:6607–6612. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.12.6607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jones P C, Fillingame R H. Genetic fusions of subunit c in the Fo sector of H+-transporting ATP synthase: functional dimers and trimers and determination of stoichiometry by cross-linking analysis. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:29701–29705. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.45.29701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jones P C, Jiang W, Fillingame R H. Arrangement of the multicopy H+-translocating subunit c in the membrane sector of the Escherichia coli F1Fo ATP synthase. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:17178–17185. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.27.17178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jones P C, Hermolin J, Jiang W, Fillingame R H. Insights into the rotary catalytic mechanism of FoF1 ATP synthase from cross-linking of subunits b and c in the Escherichia coli enzyme. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:31340–31346. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M003687200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kaim G, Wehrle F, Gerike U, Dimroth P. Molecular basis for the coupling ion specificity of F1Fo ATP synthases: probing the liganding groups for Na+ and Li+ in the c subunit of the ATP synthase from Propionigenium modestum. Biochemistry. 1997;36:9185–9194. doi: 10.1021/bi970831q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kane P M, Parra K J. Assembly and regulation of the yeast vacuolar H+-ATPase. J Exp Biol. 2000;203:81–87. doi: 10.1242/jeb.203.1.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kobayashi H. Regulation of cytoplasmic pH in streptococci. In: Reizer J, Peterkofsky A, editors. Sugar transport and metabolism in gram-positive bacteria. Chichester, United Kingdom: Ellis Horwood Ltd.; 1987. pp. 255–269. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kobayashi H, Murakami N, Unemoto T. Regulation of the cytoplasmic pH in Streptococcus faecalis. J Biol Chem. 1982;257:13246–13252. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Koebmann B J, Nilsson D, Kuipers O P, Jensen P R. The membrane-bound H+-ATPase complex is essential for growth of Lactococcus lactis. J Bacteriol. 2000;172:4738–4743. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.17.4738-4743.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Landt O, Gunert H-P, Hahn U. A general method for rapid site-directed mutagenesis using the polymerase chain reaction. Gene. 1990;96:125–128. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(90)90351-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lewis M J, Simoni R D. Deletions in hydrophilic domains of subunit a from the Escherichia coli F1Fo-ATP synthase interfere with membrane insertion or Fo assembly. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:3482–3489. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lindberg O, Ernster L. Determination of organic phosphorous compounds by phosphate analysis. Methods Biochem Anal. 1956;3:1–19. doi: 10.1002/9780470110195.ch1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mandel M, Moriyama Y, Hulmes J D, Pan Y-C E, Nelson H, Nelson N. Cloning of the cDNA encoding the 16-kDa proteolipid of chromaffin granules implies gene duplication in the evolution of H+-ATPases. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:5521–5524. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.15.5521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Marquis R E. Oxygen metabolism, oxidative stress and acid base physiology of dental plaque biofilms. J Ind Micobiol. 1995;15:198–207. doi: 10.1007/BF01569826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Miller J H. A short course in bacterial genetics. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Miller M J, Oldenburg M, Fillingame R H. The essential carboxyl group in subunit c of the F1Fo ATP synthase can be moved and H+-translocation function retained. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:4900–4904. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.13.4900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Moriyama Y, Nelson N. The vacuolar H+-ATPase, a proton pump controlled by a slip. In: Stein W D, editor. The ion pumps, structure, function and regulation. New York, N.Y: Alan R. Liss Inc.; 1988. pp. 387–394. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Munoz R, Garcia E, de la Campa A G. Quinine specifically inhibits the proteolipid subunit of the FoF1 H+-ATPase of Streptococcus pneumoniae. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:2455–2458. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.8.2455-2458.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rastogi V K, Girvin M E. Structural changes linked to proton translocation by subunit c of the ATP synthase. Nature. 1999;402:263–268. doi: 10.1038/46224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Saliba K J, Kirk K. pH regulation in the intracellular malaria parasite, Plasmodium falciparum. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:33213–33219. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.47.33213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schulenberg B, Capaldi R A. The epsilon subunit of the F1Fo complex of Escherichia coli cross-linking studies show the same structure in situ as when isolated. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:28351–28355. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.40.28351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Smith A J, Quivey R G, Faustoferri R C. Cloning and nucleotide sequence analysis of the Streptococcus mutans membrane-bound, proton-translocating ATPase operon. Gene. 1996;183:87–96. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(96)00502-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Smith D R, Richterich P, Rubenfield M, Rice P W, Butler C, Lee H-M, Kirst S, Gundersen K, Abendschan K, Xu Q, Chung M, Deloughery C, Aldredge T, Maher J, Lundstrom R, Tulig C, Falls K, Imrich J, Torrey D, Engelstein M, Breton G, Madan D, Nietupski R, Seitz B, Connelly S, McDougall S, Safer H, Gibson R, Doucette-Stamm L, Eiglmeier K, Bergh S, Cole S T, Robison K, Richterich L, Johnson J, Church G M, Mao J. Multiplex sequencing of 1.5 Mb of the Mycobacterium leprae genome. Genome Res. 1997;7:802–819. doi: 10.1101/gr.7.8.802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stock D, Leslie A G W, Walker J E. Molecular architecture of the rotary motor in ATP synthase. Science. 1999;286:1700–1705. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5445.1700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vik S B, Long J C, Wada T, Zhang D. A model for the structure of subunit a of the Escherichia coli ATP synthase and its role in proton translocation. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2000;1458:457–466. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2728(00)00094-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.42. Walker J E, Saraste M, Gay N J. The unc operon. Nucleotide sequence, regulation and structure of ATP-synthase. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1984;768:164–200. doi: 10.1016/0304-4173(84)90003-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhang Y, Fillingame R H. Essential aspartate in subunit c of F1Fo ATP synthase: effect of position 61 substitutions in helix-2 on function of Asp24 in helix-1. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:5473–5479. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]