Abstract

The complete nucleotide sequence and genetic map of pVT745 are presented. The 25-kb plasmid was isolated from Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans, a periodontal pathogen. Two-thirds of the plasmid encode functions related to conjugation, replication, and replicon stability. Among potential gene products with a high degree of similarity to known proteins are those associated with plasmid conjugation. It was shown that pVT745 derivatives not only mobilized a coresident nontransmissible plasmid, pMMB67, but also mediated their own conjugative transfer to different A. actinomycetemcomitans strains. However, transfer of pVT745 derivatives from A. actinomycetemcomitans to Escherichia coli JM109 by conjugation was successful only when an E. coli origin of replication was present on the pVT745 construct. Surprisingly, 16 open reading frames encode products of unknown function. The plasmid contains a conserved replication region which belongs to the HAP (Haemophilus-Actinobacillus-Pasteurella) theta replicon family. However, its host range appears to be rather narrow compared to other members of this family. Sequences homologous to pVT745 have previously been detected in the chromosomes of numerous A. actinomycetemcomitans strains. The nature and origin of these homologs are discussed based on information derived from the nucleotide sequence.

The gram-negative bacterium Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans is a capnophilic coccobacillus. The organism has been associated with several forms of periodontal disease such as localized juvenile periodontitis and rapidly progressive periodontitis, as well as with soft tissue abscesses and endocarditis (58). In a previous study 39 isolates of this periodontal pathogen had been screened for the presence of indigenous plasmids in an effort to evaluate the role(s) of such genetic elements in oral bacteria (32). Three plasmids, pVT736-1 (2 kb), pVT736-2 (>30 kb), and pVT745 (25 kb), were identified in two strains, suggesting that the occurrence of plasmids in A. actinomycetemcomitans was rare. The ultimate goal was to determine the biological properties of these plasmids, to assess their potential contribution to the pathogenicity of A. actinomycetemcomitans, and to evaluate their usefulness as tools in recombinant DNA technology. Previous work has focused mainly on the characterization of pVT736-1, one of the first rolling circle replicating (RCR) plasmids isolated from gram-negative bacteria (17, 18). It was shown that pVT736-1 was cryptic, that it was not related to RCR plasmids found in gram-positive bacteria, and that it encoded a new type of partitioning system (20).

Preliminary characterization suggested that there was no obvious phenotype associated with pVT745 (41). Its size was a strong indication that the plasmid replicated by a theta mechanism rather than by a rolling circle mode. Although pVT745 had been isolated from one strain of A. actinomycetemcomitans (VT745) only, it was demonstrated by Southern hybridization that this plasmid shared sequence homologies with chromosomal DNA from numerous A. actinomycetemcomitans isolates (39, 40). However, plasmid DNA did not hybridize with the genome of the strain from which it was isolated. It was suggested that the plasmid might have integrated into the chromosome of these strains. This was of particular interest since there is no evidence for the occurrence or frequency of natural genetic exchange among gram-negative bacteria found in the oral cavity. Integration of a plasmid into the A. actinomycetemcomitans chromosome may promote the transfer of chromosomal genes during conjugation or suggest the presence of one or more insertion elements or transposons. The goal of the current study was to obtain and analyze the nucleotide sequence of pVT745 in an effort to characterize plasmid-encoded functions. This would facilitate a determination of which genes pVT745 and the different A. actinomycetemcomitans chromosomes were sharing and whether such genes and/or their products could contribute to the organism's virulence. Sequence analysis of pVT745 revealed the presence of a cluster of genes encoding products homologous to proteins identified in type IV secretion systems (for recent review, see reference 11). Such transport systems are widespread and highly versatile since they can export protein and/or DNA/protein complexes. Their presence on plasmids from gram-negative organisms has been associated with conjugative transfer. Intra- and interspecies conjugative transfer of pVT745 derivatives was demonstrated.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and growth conditions.

The strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. The A. actinomycetemcomitans recipient strain ATCC 29522Rif was isolated as a spontaneous rifampin-resistant mutant of strain ATCC 29522. A. actinomycetemcomitans was grown in TSBYE (3% Trypticase soy broth, 0.6% yeast extract) at 37°C in 10% CO2. Escherichia coli JM109 was grown in YT medium (37). Where appropriate, antimicrobial agents were used at the following concentrations: ampicillin, 50 μg/ml; kanamycin, 50 μg/ml (except for strain ATCC 700685 with 100 μg/ml); rifampin, 100 μg/ml; and spectinomycin, 100 μg/ml.

TABLE 1.

Strains and plasmids used

| Strain or plasmid | Descriptiona | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| A. actinomycetemcomitans | ||

| ATCC 29522 | ATCC | |

| ATCC 29522Rif | Rif | This work |

| ATCC 700685 | JP2-like strain; plasmid-free | ATCC |

| VT745 | JP2 strain; containing pVT745 | 32 |

| E. coli JM109 | recA1 supE44 endA1 hsdR17 gyrA96 relA1 thi Δ (lac-proAB) | 57 |

| Plasmids | ||

| pDMG3 | Sp; pVT736-1 derivative | 19 |

| pDMG20 | Km; derivative of pVT745; single crossover | This work |

| pDMG21 | Km; derivative of pVT745; double crossover | This work |

| pGB2 | Sp; low-copy-number cloning vector based on pSC101; nonmobilizable | 12 |

| pGB2R | Km; pGB2 derivative; used for allelic replacement | This work |

| pJH1 | Em Km Sm Tc; conjugative | 31 |

| pKN1 | Sp; pGB2/6.9-kb PstI-BamHI insert of pVT745 | 39 |

| pKN2 | Sp; pGB2/8.2-kb PstI-PstI insert of pVT745 | 39 |

| pKN3 | Sp; pGB2/10.3-kb BamHI-PstI insert of pVT745 | 39 |

| pMMB67 | Ap; mobilizable; RSF1010 derivative | 16 |

| pUC19 | Ap; high-copy-number cloning vector | 57 |

| pVT745 | Conjugative | 32 |

Rif, rifampin resistant; Sp, spectinomycin resistant; Km, kanamycin resistant; Ap, ampicillin resistant; Em, erythromycin resistant; Sm, streptomycin resistant; Tc, tetracycline resistant.

DNA preparations and recombinant DNA techniques.

Plasmid DNA was isolated from A. actinomycetemcomitans and E. coli as described previously (20). DNA templates used in sequencing were purified by CsCl buoyant density centrifugation (47) or by use of the Wizard Plus Midiprep kit (Promega). Restriction endonucleases and T4 DNA ligase were used in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions. Standard recombinant DNA techniques were performed as described by Sambrook et al. (47). DNA-DNA hybridization conditions and transformation by electroporation were as described previously (20).

DNA sequencing.

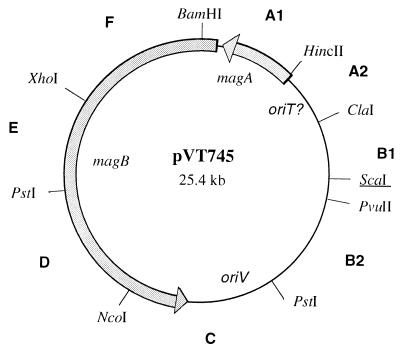

Three previously described clones of pVT745, pKN1, pKN2, and pKN3, were used to determine the nucleotide sequence of the plasmid (Table 1) (39). Smaller fragments of these clones, labeled A1 through F, were obtained by restriction enzyme digestion at the sites shown in Fig. 1. These fragments were then subcloned into either pUC19 (high copy) (57) or pGB2 (low copy) (12). The ends of the inserts were sequenced with M13 standard and reverse primers for pUC clones or custom-made primers flanking the multiple cloning site of pGB2. Automated sequencing was performed with fluorescent terminators by cycle sequencing with an Applied Biosystems model 373 DNA sequencer (DNA facility at the University of Texas Health Science Center, San Antonio). Generated sequences were used to design synthetic primers. Sequences were read on a Beckman Gelmate and entered directly in the computer. Additional sequencing was performed with pVT745 using the Omnibase DNA Cycle Sequencing System (Promega) to resolve ambiguities, to close gaps, and to cross restriction endonuclease sites.

FIG. 1.

Physical map of pVT745. Only restriction sites relevant for subcloning fragments A1 to F are depicted. Several of these sites are present more than once on the plasmid. The unique ScaI site (underlined) was the target site for the insertion of a kanamycin gene (Fig. 2.). The location and transcriptional orientation of the magA and magB gene clusters implicated in conjugation and the putative origins of replication (oriV) and transfer (oriT) are shown.

Annotation.

MacDNASIS from Hitachi Software was used to analyze and assemble sequences and to determine the presence of putative genes. Open reading frames (ORFs) encoding at least 50 amino acids and displaying a translational start codon, as well as a potential E. coli Shine-Dalgarno consensus sequence (49), were identified. Smaller ORFs were listed only if they or their putative products showed significant similarities to known genes and/or proteins or if they appeared to be transcriptionally linked to adjacent ORFs. Generally, in the absence of experimental data the start codon farthest upstream was used to annotate the ORF start site.

Both DNA and deduced protein sequences were searched against the current NCBI, GenBank, and EMBL databases by using programs based on the BLAST algorithm (1). Known genes and putative functions were assigned for individual ORFs by inspection of the search output. Potential significant protein sites were searched against PROSITE database (Swiss Institute of Bioinformatics, Geneva, Switzerland). Signal sequences were predicted by the SignalP World Wide Web server (SignalP v1.1, World Wide Web Prediction Server, Center for Biological Sequence Analysis) according to the method of Nielsen et al. (38). The computer program PSORT was used for the prediction of protein localization sites in cells (http://psort.nibb.ac.jp/).

Construction of recombinant pVT745 derivatives.

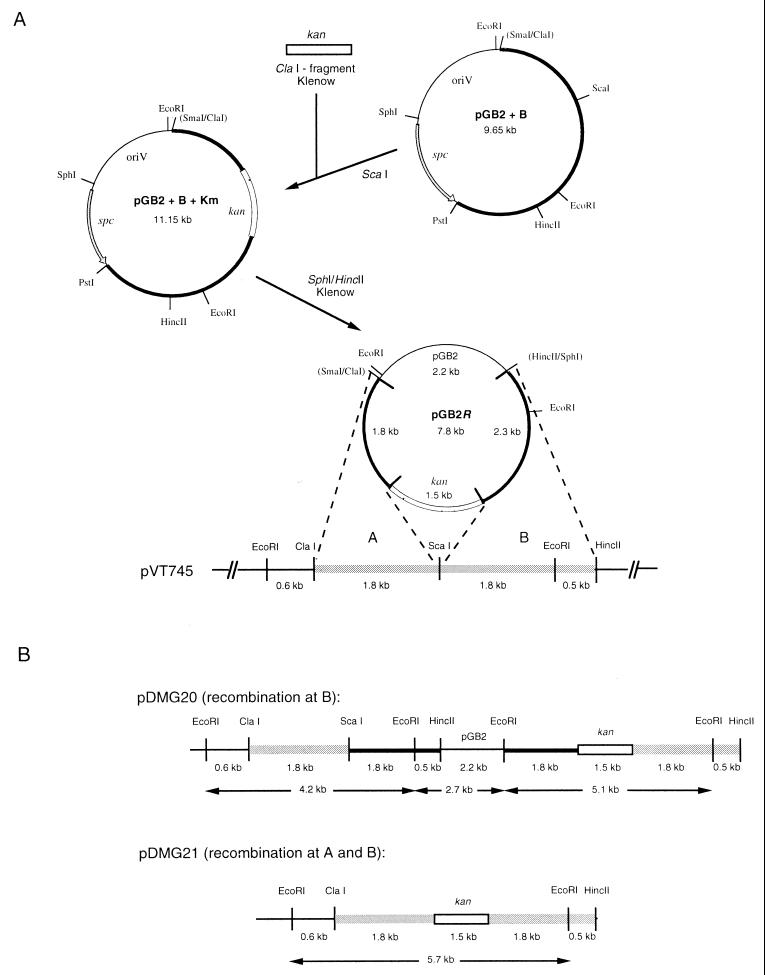

A selective marker, kan, was inserted into pVT745 at a unique ScaI site located at the 3′ end of gene AA05 (23 bp from the translational stop codon) via allelic exchange by homologous recombination. The different steps involved in the construction of the pVT745-derivatives are outlined in Fig. 2A. All recombinant constructs were obtained in E. coli JM109. Vector pGB2 (12) containing fragment B (B1+B2) from pVT745 (Fig. 1) was digested with ScaI. A 1.5-kb ClaI-fragment carrying kan from plasmid pJH1 (31) was blunt ended with Klenow polymerase I (Gibco-BRL) and ligated into the single ScaI site. A segment harboring the pGB2-specific marker, spc, was then deleted from this construct by double digestion with SphI/HincII, treatment with Klenow polymerase I, and religation of the free ends of the replicon. This last construct, pGB2R, was then used to transform A. actinomycetemcomitans VT745 by electroporation. Since pGB2 does not replicate in this host, only transformants that had the kan gene integrated into the resident plasmid, pVT745, by homologous recombination were able to grow in the presence of kanamycin. The pGB2 construct allowed for a single or a double crossover event to occur. Plasmid DNA isolated from the transformants was analyzed by restriction enzyme digestion and Southern blot hybridizations using pGB2 and the kanamycin resistance gene as probes. Results from these experiments confirmed that both a single crossover event and a double crossover event had occurred. The resulting pVT745 derivatives pDMG20 (single crossover) and pDMG21 (double crossover) were subsequently used in conjugation and mobilization assays (Fig. 2B).

FIG. 2.

Construction of recombinant pVT745 derivatives via allelic exchange. (A) A fragment of pVT745 was cloned into pGB2 and a kanamycin resistance gene inserted into the unique ScaI site of this construct for allelic recombination with pVT745. A detailed description of the construction is provided in Material and Methods. (B) Restriction endonuclease maps of the two types of recombinants, pDMG20 and pDMG21. The physical maps of key restriction endonuclease sites are shown along with the size of EcoRI fragments that can be derived from each recombinant type at the site of recombination. DNA segments are not drawn to scale. kan, kanamycin resistance gene; spc, spectinomycin resistance gene.

Mating experiments.

Conjugative matings were performed between A. actinomycetemcomitans strains using JP2::pDMG20 and JP2::pDMG21 as donor strains and ATCC 29522Rif, ATCC 29522::pDMG3, and ATCC 700685::pDMG3 as recipient cells. In addition, E. coli JM109 served as an interspecies recipient strain. Donors and recipients were grown to mid-exponential phase in broth cultures and mixed in a total volume of 1 ml at a ratio of 1:1 (the recipient was A. actinomycetemcomitans) and 10:1 (the recipient was E. coli). The latter ratio was different to compensate for the much faster growth rate of E. coli. The mixture was then centrifuged, and the cells were washed and spotted onto a TSBYE agar plate. After incubation for 4 h (E. coli recipients) or 6 h (A. actinomycetemcomitans recipients) at 37°C in 10% CO2, the cells were scraped off the plate and resuspended in 1 ml of TSBYE. Aliquots of serial dilutions of the suspension were then spread onto TSBYE to determine the number of A. actinomycetemcomitans transconjugants and the number of donor cells and on YT plates to determine the number of E. coli transconjugants. All plates contained the appropriate antibiotics. Incubation of plates was in 10% CO2, except for YT plates. Transfer frequencies were expressed as the number of transconjugants per donor cell. Selected transconjugants were examined for the presence of plasmid DNA.

Broth matings were performed similarly except that donor and recipient cells were washed prior to their mixture. Mating times in TSBYE liquid medium were comparable to those used in surface mating.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The complete sequence of pVT745 from A. actinomycetemcomitans VT745 has been deposited in the GenBank database and assigned accession number AF302424.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

General description.

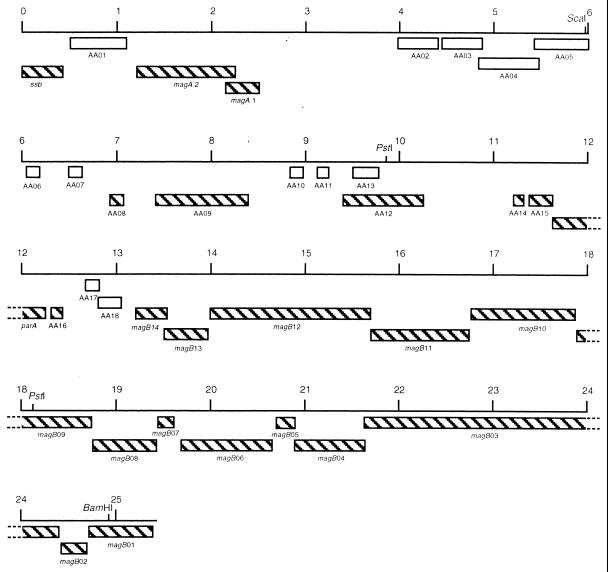

The entire sequence of pVT745 was determined to be 25,420 bp. Annotation of the derived sequences identified 36 ORFs likely to represent functional translated genes. A total of 12 of these ORFs were transcribed in a clockwise orientation, while the remaining 24 ORFs were transcribed counterclockwise. The positions and transcriptional orientations of all ORFs are depicted in Fig. 3. Table 2 lists the putative functions, the characteristics, and the closest relatives for the predicted product of each ORF. Seventeen ORFs and their products had no detectable homologs in the databases. However, some of these genes could be associated with conjugation and partitioning due to the fact that they appeared to be transcriptionally linked to genes with known functions (Table 2). In fact, many of the ORFs identified on pVT745 either overlapped or were separated by only a few nucleotides, indicating that they may be part of operons. Such potential operons are represented by genes magA1 and magA2, ssb to magB14, AA16 to AA14, and AA02 to AA06.

FIG. 3.

Genetic organization of pVT745. Genes are represented by boxes. Open boxes indicate that the corresponding ORFs are transcribed clockwise; hatched boxes indicate that the ORFs are transcribed counterclockwise. Kilobase coordinates are shown, as are the positions of the two PstI and the single BamHI and ScaI sites. Genes of unknown function are labeled AA (for A. actinomycetemcomitans) followed by a number. Other gene designations are associated with potential functions of corresponding gene products as listed in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

ORFs on pVT745 of A. actinomycetemcomitans VT745

| Gene | Coding region (start–end) | No. of amino acids in product | Properties and/or putative function of gene product | Homologous protein (species) (GenBank accession no.) (% identity/% homology)a | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ssb | 452–15 | 145 | Single-stranded DNA binding protein | SSB (H. influenzae) (U04997) (75/83) | 28 |

| AA01 | 630–1208 | 192 | Site-specific recombinase | DNA invertase (E. coli plasmid p15B) (X62121) (45/58) | 26 |

| magA2 | 2369–1212 | 385 | Transfer replication; DNA relaxase (also called nickase) | Nickase (E. coli plasmid R6K) (X95535) (29/46) | 4 |

| magA1 | 2635–2339 | 98 | Transfer replication?; oriT-recognizing protein? | ||

| AA02 | 3996–4385 | 129 | Cytoplasmic | ||

| AA03 | 4426–4800 | 124 | Cytoplasmic | ||

| AA04 | 4790–5467 | 225 | Cytoplasmic | ||

| AA05 | 5445–6062 | 205 | Cytoplasmic | ||

| AA06 | 6052–6249 | 65 | Cytoplasmic | ||

| AA07 | 6528–6701 | 57 | Cytoplasmic | ||

| AA08 | 7101–6889 | 70 | Cytoplasmic | ||

| AA09 | 8415–7408 | 335 | Cytoplasmic | Hypothetical protein (Y. enterocolitica plasmid) (Y13308) (19/27) | 25 |

| AA10 | 8796–8999 | 67 | DNA repair? | Hypothetical protein (Y. pestis plasmid) (AF152923) (40/57) | 15 |

| AA11 | 9160–9321 | 53 | Cytoplasmic | DinJ1 (E. coli) (AE000131) (34/46) | 7 |

| AA12 | 10303–9407 | 298 | Cytoplasmic | Putative transporter protein (N. meningitidis) (AE002523) (37/54) | 51 |

| AA13 | 9525–9803 | 92 | Cytoplasmic | ||

| AA14 | 11355–11236 | 39 | Cytoplasmic | ||

| AA15 | 11647–11408 | 79 | Plasmid stability? | ||

| parA | 12281–11640 | 213 | Plasmid stability | StaA (Pseudomonas plasmid pVS1) (AF118810) (41/64) | 24 |

| AA16 | 12435–12304 | 43 | Cytoplasmic | ||

| AA17 | 12696–12863 | 55 | Cytoplasmic | ||

| AA18 | 12860–13144 | 94 | Cytoplasmic | ||

| magB14 | 13556–13224 | 110 | Export signal | TrbM (E. coli plasmid IncPα) (M93696) (38/69) | 34 |

| magB13 | 13977–13540 | 145 | Lipoprotein | CagT (H. pylori) (U60176) (13/23) | 8 |

| magB12 | 15750–14011 | 579 | Inner membrane; ATP/GTP-binding site motif A: coupling of DNA processing to DNA transport | Cag5 (H. pylori), (AE000566) (30/49) | 8 |

| TaxB (E. coli plasmid R6K), (Y10906) (30/47) | 42 | ||||

| VirD4 (R. prowazekii) (AJ235271) (24/42) | 3 | ||||

| magB11 | 16781–15750 | 343 | Cytoplasmic; ATP/GTP-binding site motif A: sigma-54 interaction domain | VirB11 (B. abortus) (AF226278) (51/65) | 43 |

| VirB11 (B. suis) (AF141604) (45/56) | |||||

| VirB11 (B. henselae) (AF182718) (41/56) | 44 | ||||

| magB10 | 17903–16794 | 369 | Inner membrane; channel formation | VirB10 (B. abortus, B. suis) (AF226278, AF141604) (27/41) | 43 |

| VirB10 (R. etli) (AF176227) (27/39) | |||||

| magB09 | 18782–17913 | 289 | Export signal; channel formation | VirB9 (B. abortus, B. suis) (AF226278, AF141604) (36/54) | 43 |

| PtlF (B. pertussis) (L10720) (30/43) | 13.53 | ||||

| magB08 | 19458–18772 | 228 | Inner membrane; regulatory protein of LysR family; channel formation | VirB8 (B. abortus, B. suis) (AF226278, AF141604) (36/55) | 43 |

| PtlE (B. pertussis) (L10720) (29/52) | 13, 53 | ||||

| magB07 | 19598–19455 | 47 | Lipoprotein; channel formation | ||

| magB06 | 20668–19667 | 333 | Inner membrane; channel formation | ORF5 (Y. pestis plasmid pYC) (AF152923) (22/39) | 15 |

| VirB6 (B. abortus, B. suis) (AF226278, AF141604) (20/38) | 43 | ||||

| magB05 | 20905–20678 | 75 | Lipoprotein; entry exclusion | ORF4 (Y. pestis plasmid pYC) (AF152923) (28/40) | 15 |

| Eex (E. coli plasmid pKM101) (U09868) (27/36) | 46 | ||||

| magB04 | 21695–20919 | 258 | Export signal; channel formation | ORF6 (Y. pestis plasmid pYC) (AF152923) (27/45) | 15 |

| TrbJ (E. coli plasmid IncPα) (M93696) (23/38) | 33, 34 | ||||

| VirB5 (B. abortus, B. suis) (AF226278, AF141604) (17/36) | 43 | ||||

| magB03 | 24429–21658 | 923 | Inner membrane; ATP/GTP-binding site motif A | VirB4 (B. abortus, B. suis) (AF226278, AF141604) (35/54) | 43 |

| PtlC (B. pertussis) (L10720) (33/50) | 13, 53 | ||||

| magB02 | 24729–24442 | 95 | Export signal: pilus? | ||

| magB01 | 25406–24756 | 216 | Inner membrane; DNA transfer? | VirB1 (B. abortus, B. suis) (AF226278, AF141604) (38/58) | 43 |

| TraL (E. coli plasmid pKM101) (U09868) (32/53) | 46 |

The numbers indicated refer to the percent identity or homology over the total length of the protein. In several instances, the degree of identity and/or similarity was higher for just the N- or the C-terminal half of the protein. H. influenzae, Haemophilus influenzae; Y. pestis, Yersinia pestis; Y. enterocolitica, Yersinia enterocolitica; R. etli, Rhizobium etli; R. prowazekii, Rhizobium prowazekii; B. henselae, Bartonella henselae.

The plasmid contained two noncoding regions located between magA1 and AA02 and between AA12 and AA14. As discussed below, these areas are most likely associated with the origins of transfer, oriT, and replication, oriV. The latter segment showed the presence of two gene remnants belonging to merR, a regulatory gene in bacterial mercury resistance operons, and several remnants of the HAP (Haemophilus-Actinobacillus-Pasteurella)-specific ROB β-lactamase (bla) gene. Another incomplete copy of bla was located downstream of AA12, suggesting that bla had been interrupted by the insertion of AA12, a Neisseria gene homolog (Table 2).

The overall G+C content of pVT745 was 38.99%. Smaller defined areas were analyzed for regional variation in G+C content. Surprisingly, a small section covering nucleotides 9800 to 10900 had a G+C content of 53.90%. This segment harbored an ORF (AA12) which was highly homologous to a putative transporter gene of Neisseria meningitidis (Table 2), an organism with a G+C content of 47 to 52%. Kaplan and Fine (29) divided A. actinomycetemcomitans genes into two groups based on codon usage. According to this classification the genes of pVT745 would fall into group 2, which represents genes that most likely have been acquired by horizontal gene transfer. Additional DNA level homology to known nucleotide sequences was limited to three small areas. The first one spanned nucleotides 9366 to 9671, which showed 99% identity with Serratia marcescens plasmid R471a (30); the second was a 165-bp stretch (nucleotides 10222 to 10387) that was 97% homologous to Pseudomonas putida plasmid pTN8 (27), and the last encoded the potential origin of replication, oriV. Plasmid pVT745 did not encode any protein sequences with homology to transposases or ORFs known to be associated with insertion sequences.

Conjugation-like ORFs.

GenBank analysis revealed that the predicted proteins encoded within a DNA segment of 12 kb showed homology to the type IV family of secretion systems (10). Corresponding systems found on plasmids of gram-negative bacteria are associated with DNA transfer such as in conjugation events, whereas their presence in the chromosomes of bacterial pathogens such as Bordetella pertussis and Helicobacter pylori has been implicated in the export of proteinaceous virulence factors (for a review, see reference 11). BLASTX searches revealed that the pVT745-specific proteins showed high levels of similarity with both chromosomally encoded type IV transport proteins and traditional plasmid transfer systems (Table 2). Based on these homologies it was reasonable to assume that pVT745 was self-transmissible, and therefore genes implicated in conjugation were designated mag (mating-associated genes). As shown for other conjugative plasmids transfer functions seem to be clustered in two regions. The first region is responsible for DNA processing functions and, except for Legionella pneumophila (48), is not found in chromosomally encoded type IV secretion systems. The other region is most probably associated with mating pore formation, pilus assembly, and entry exclusion. To separate these two functions within the mag genes, the letter “A” was added to genes whose products showed homologies to proteins required for conjugal DNA processing, and the letter “B” was added to genes encoding products involved in mating aggregate formation and entry exclusion. As with genes found in homologous systems, either the ribosome-binding site or the initiation codon of most ORFs located in magA and magB overlapped with the end of the previous ORF, suggesting that these genes are transcriptionally linked. Most of the genes clustered in magB seem to be associated with the formation of a multicomponent pore or channel which spans both bacterial membranes and is used to transport DNA (11). Although, the location and organization of genes in magA and magB resembles those for other conjugative plasmids and type IV secretion systems, the location of magB12 (encoding the VirD4 homolog), magB13 (encoding a lipoprotein), and magB14 (encoding a TrbM homolog) at the end of magB is rather unusual. Gene trbM is only found in the IncP-specific transfer operon and its role in conjugation, if any, is unknown (45). Also, the presence of the additional lipoprotein encoded by magB13 has been reported for the type IV secretion system of Brucella suis only (43).

The predicted gene product of magB01 showed 30 to 40% identity over a stretch of 163 aa to proteins associated with efficient conjugative DNA transfer (VirB1 and homologs) (6). However, the C-terminal region of MagB01 could not be aligned with any of the known VirB1 homologs. VirB1 homologs contain a Sec-dependent export signal and motifs usually found in lytic transglycosylases (6). It is believed that this group of proteins causes local lysis of the peptidoglycan layer after being exported into the periplasm (5). Further proteolytic processing of VirB1 then leads to the secretion of the C-terminal end to the exterior of the bacterial cell (5). Although the motifs for transglycosylase activity are more or less conserved in MagB01, the pVT745-specific protein lacks the presence of a signal peptide. Therefore, MagB01 most likely remains in the cytoplasm and does not function as a transglycosylase.

If indeed the ORFs found in the magB cluster form an operon, it is not clear yet if the corresponding promoter is located upstream of magB01, as in most conjugation systems, or gene ssb. The translational stop codon of the latter gene is separated from the magB01 ATG by 15 bp only.

In gram-negative bacteria initial contact in conjugation is pilus mediated. None of the genes located in the magB cluster exhibited homology to known pilin proteins. The size of magB02 and its location in the putative operon is in accordance with genes in other conjugation systems encoding such proteins. In addition, successful mating experiments conducted in A. actinomycetemcomitans broth cultures suggest the presence of a conjugative pilus which is believed to facilitate the formation of mating aggregates upon random collision between donor and recipient strains. Nonetheless, electron microscopy of pVT745 harboring cells and mutational analysis of magB02 will be necessary to determine if a pilus structure is involved in pVT745-mediated conjugation.

As described for other conjugative plasmids, such as IncPα (33) and IncW (46), pVT745 seems to contain a single gene associated with entry exclusion (Table 2). The small lipoprotein, MagB05, is homologous to Eex of pKM101, a protein required for entry exclusion (36, 46). MagB07 had no significant homolog. However, the size of this protein and the location of the encoding gene in the magB cluster strongly suggest that MagB07 is an analog of the VirB7 group of proteins. This is supported by the fact that MagB07 contains two cysteine residues. It has been shown for A. tumefaciens that VirB7 forms intermolecular disulfide bonds with itself and VirB9 (2, 50). However, since the sole Cys residue of MagB09, the pVT745-specific VirB9 homolog, is located in the signal sequence, its potential interaction with MagB07 is unlikely to be an S-S linkage. The three potential cytoplasmic membrane ATPases, MagB03, MagB11, and MagB12, were fairly conserved when compared with their counterparts in related systems. Like their homologs they contain the Walker A nucleoside triphosphate-binding domain and may provide energy for the export of DNA. The RGD cell adhesion motif which is conserved among most VirB4 homologs was missing in MagB03. The predicted proteins MagB06, MagB08, MagB09, and MagB10 were also conserved. It has been shown for their homologs that they are located in the inner and outer membrane of the bacterial cell wall, where they associate to form a protein channel necessary for the transport of macromolecules (21). MagB14 contained a limited degree of homology to TrbM of IncP plasmids, although it was below the cutoff for significance.

The conjugation process in gram-negative bacteria is initiated at the origin of transfer where, after cleavage, a single-stranded DNA molecule is released which will ultimately be transferred to a recipient cell. oriT is a cis-acting site on the plasmid which is generally located within an intergenic region. A main feature of oriT sites is the presence of an inverted repeat adjacent to a DNA cleavage site (nic) which is cut by a specific enzyme, the nickase or relaxase, with the help of accessory proteins. The nic site, but not the inverted repeat, is usually rather conserved among conjugative plasmids from gram-negative bacteria (45). However, no homology was detected between known oriT sites and pVT745. Nonetheless, it is suggested that the pVT745-specific oriT is located within a 1-kb region just upstream of magA1. This assumption is based on the fact that (i) oriT sequences of other conjugative plasmids have been found in the vicinity of their DNA processing genes, (ii) the region in question is noncoding, and (iii) the presence of two inverted repeats of 17 and 20 bp, respectively. It has been shown that DNA cleavage-joining reactions require a nickase and at least one accessory DNA-binding protein (reviewed in reference (45). The latter protein recognizes a specific sequence within oriT. Binding to this sequence will allow access of the nickase to the nic site. The nickases of different conjugative plasmids are rather conserved in their amino termini. They all contain three conserved motifs associated with DNA cleavage and joining (35, 45). The presence of these motifs in the predicted gene product of MagA2 indicated that MagA2 belongs to this group of proteins. However, unlike other nickases, MagA2 does not possess any nucleotide-binding motifs. Also, like some other conjugative nickases MagA2 seems to lack a helicase domain. Alignments of MagA1 protein with known accessory DNA-binding proteins essential for DNA processing showed little sequence similarity. However, its gene appears to be transcriptionally linked to magA2. In addition, the protein displays a row of conserved Leu residues similar to other accessory binding proteins (35) and may therefore be a functional analog. It is postulated that MagA1 binds to oriT, thereby enabling MagA2 to access and cleave the yet to be determined pVT745-specific nic site.

Conjugative transfer functions.

The presence of ORFs homologous to genes implicated in conjugation suggested that pVT745 is able to mediate its own conjugative transfer and to support the mobilization of non-self-transmissible, coresident plasmids. Mobilizable plasmids, such as the RSF1010 derivative, pMMB67 (16), only carry genes necessary for DNA processing and an oriT site corresponding to the plasmid-encoded nickase. They lack the genes required for mating pore formation. Since pVT745 did not carry any known selective marker which would allow the study of conjugation transfer functions, a kanamycin resistance gene derived from pJH1 (31) was inserted into the plasmid by homologous recombination as described in Materials and Methods. The integration of the kan gene via single and double crossover events was verified by EcoRI restriction enzyme analysis and Southern blot hybridization (not shown). Two types of recombinants were generated which resulted in construct pDMG20 and construct pDMG21.

Both functions, i.e., self-transfer and mobilization of a non-self-transmissible plasmid, were demonstrated by using various donor and recipient strains (Table 3). A. actinomycetemcomitans recipients chosen had no (ATCC 700685) or only limited (ATCC 29522; unpublished results) homology to pVT745 at the DNA level to avoid potential recombination events after acquisition of the conjugative plasmid. Due to the lack of markers that would allow for the distinction of A. actinomycetemcomitans donor and recipient cells, potential recipient strains were either screened for spontaneous rifampin mutants or equipped with a nonmobilizable plasmid, pDMG3, carrying a spectinomycin resistance gene.

TABLE 3.

Transfer frequencies for pVT745 derivatives and pMMB67 from an A. actinomycetemcomitans donor strain into different recipients

| Donor strain | Donor plasmid(s) | No. of transconjugants per donora in recipient strain(s):

|

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ATCC 29522Rif and ATCC 29522::pDMG3

|

ATCC 700685:pDMG3:

|

JM109

|

||||||||

| KAN | AMP | KAN AMP | KAN | AMP | KAN AMP | KAN | AMP | KAN AMP | ||

| Conjugation | ||||||||||

| JP2 | pDMG20 | 10−5 | NA | NA | 10−5 | NA | NA | 10−6 | NA | NA |

| JP2 | pDMG21 | 10−5 | NA | NA | 10−4 | NA | NA | <10−9 | NA | NA |

| Mobilization | ||||||||||

| JP2 | pDMG20, pMMB67 | 10−6 | 10−5 | 10−6 | NA | NA | NA | 10−5 | 10−6 | 10−7 |

| JP2 | pDMG21, pMMB67 | 10−6 | 10−6 | 10−6 | NA | NA | NA | <10−9 | 10−5 | <10−9 |

The number of transconjugants per donor (average of at least two independent experiments) is shown. The selection of transconjugants was done for the recipient strain as indicated in the text and with kanamycin (KAN), ampicillin (AMP), or both for the incoming plasmid(s) as shown in the table. The ATCC strains are A. actinomycetemcomitans; strain JM109 is E. coli. NA, not applicable.

Both pVT745 derivatives and pMMB67 were transferable between A. actinomycetemcomitans strains. Transfer frequencies were similar for the different recipient strains used (Table 3). These results demonstrated that a recipient strain can be distinguished from a donor strain simply by carrying a segregationally stable, nonmobilizable plasmid with an appropriate selective marker. This will eliminate the need to select for spontaneous antibiotic-resistant mutants in future recipient strains when studying the host range of pVT745. Kanamycin-resistant transconjugants harboring pDMG20 and pDMG21 were subsequently used as donors in mating experiments to show that they had acquired the ability to transfer their plasmids to other A. actinomycetemcomitans recipients (not shown).

All plasmids tested were readily transferred to JM109, with the exception of pDMG21 which, as the result of a double crossover event does, not carry pGB2, the E. coli-specific oriV. Although, construct pDMG20 was transferred into E. coli, the plasmid was structurally unstable in its new host. When transconjugants were examined for the presence of pDMG20, different truncated derivatives of the original construct were isolated. Comparisons of restriction enzyme profiles of these plasmids revealed that 13 to 18 kb of DNA were missing from the original construct. In all cases deletions included the magB cluster (not shown). Some transformants had lost the original pVT745 and contained only pGB2R, the construct made for allelic replacement (Fig. 2), which apparently had been excised from pDMG20 via recombination. Southern blot hybridization experiments revealed that the missing plasmid DNA had not integrated into the chromosome of JM109.

Plasmid transfer in broth matings from A. actinomycetemcomitans to ATCC 29522::pDMG3 and JM109 could be demonstrated for pDMG20, albeit the frequencies of 10−7 and 10−8, respectively, were lower than those observed in solid surface matings.

Replication and partition functions.

The putative origin of replication was located downstream of magB within a ca. 0.63-kb noncoding region (Fig. 1). This region showed 88 to 91% identity to the origin of replication of Haemophilus ducreyi plasmid, pLS88 (4.8 kb) (14). Similar regions have been described for Pasteurella multocida plasmid pIG1 (5.4 kb) (56), and two plasmids, pYFC1 and pAB2, were isolated from Pasteurella haemolytica (9, 55). These data indicate that there is an evolutionary link between multiple plasmids in the HAP group. Replication of pLS88 seems to be independent of any plasmid-encoded protein (14). Nucleotide sequence analysis performed by Wright et al. (56) revealed that the replication regions contained two to three major inverted repeats (IR20, IR16, and IR38). Two of these repeats can be found in the putative oriV of pVT745. However, a region of approximately 0.5 kb present in all of the above-mentioned plasmids is missing on pVT745. This deletion might have an effect on the host range of pVT745. Whereas pAB2 and pIG1 replicated in numerous gram-negative organisms, including E. coli (55, 56), conjugation experiments with the pVT745 derivatives indicated that pVT745 could be transferred to E. coli but was unable to support its replication in the absence of a specific E. coli replicon (see above). This was confirmed by transformation of JM109 with pDMG20 and pDMG21 via electroporation. E. coli transformants could only be obtained with pDMG20 which carried the pGB2 replicon. However, as already observed in the mating experiments, the plasmid was structurally unstable. All transformants carried a 7.8-kb plasmid only, which was identical to pGB2R. Therefore, it can be concluded that the pVT745-specific oriV is not functional in E. coli and that genes in the conjugative transfer region cannot be maintained in JM109. The reason for the latter is unknown. However, it is of interest to note that plasmids pAB2 and pIG1 are mobilizable (55, 56) but not conjugative. The other plasmids, pLS88 and pYFC1, are neither conjugative nor mobilizable.

As described for pLS88 (14) and pIG1 (56), the putative oriV of pVT745 contains stretches of DNA showing strong homologies to portions of the ROB-1–β-lactamase gene from species such as P. haemolytica, Haemophilus influenzae, and Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae. Interestingly, an intact bla gene is located just upstream of oriV on pAB2 (55). Similarities between pVT745 and the other replicons do not extend beyond the extremities of the rep sequence.

A putative partition region is located adjacent to oriV. The predicted product of ORF parA shows homology to a family of partitioning proteins, which actively divide and distribute plasmid copies upon cell division. (54). ORF AA15 overlaps with parA and might therefore be transcriptionally linked to it. This would be in accordance with most active partition systems which consist of an operon encoding two proteins and a cis-acting site. In addition, AA01 encodes a recombinase, which is a member of the DNA invertase-resolvase family (22). The recombinase might contribute to plasmid stability by resolution of plasmid multimers.

DNA sequences shared by pVT745 and A. actinomycetemcomitans genomes.

It was shown previously that the genomes of numerous strains of A. actinomycetemcomitans contain regions with homology to pVT745 (39). Southern hybridization studies with three different pVT745-specific fragments allowed for the identification of five strain-dependent groups, A to E, based on hybridization patterns (39). Additional hybridization studies were performed with smaller fragments ranging in size from 1.3 to 7 kb (40). A comparison of the hybridizing fragments with the pVT745 sequence in hand showed that some of these regions of homology were associated with genes located in the magB cluster for groups A, D, and E. However, none of the strains seemed to contain a complete magB operon. In addition, none of the five groups exhibited similarities to any of the genes found in magA. Strains with hybridization patterns C and D showed a high degree of homology with a probe containing the pVT745-specific oriV. The other three groups also hybridized with this probe. However, the signal for strain 725, representing pattern E, was very weak (40). The last region of homology was associated with ORFs homologous to genes found in Yersinia (AA09 and AA10) and Neisseria (AA12) spp. (Table 2). Strain VT747, the only representative of group D, hybridized to DNA fragments carrying AA09 to AA12. Representatives of groups A and C showed some similarities to the DNA segment harboring AA10 to AA12. The presence of remnants of the pVT745-specific oriV and conjugative system suggests that this plasmid, or a related vector, once inserted into the chromosome of various A. actinomycetemcomitans strains with subsequent strain-specific loss of the majority of plasmid-encoded genes. However, the sequences shared could also have been inherited from different donor organisms at different times, instead of being the result of a single event that occurred in the distant past.

The nucleotide sequence of pVT745 was also compared to the genome of strain ATCC 700685, which is currently being sequenced at the University of Oklahoma (www.genome.ou.edu/act.html) using a BLAST search. Strain ATCC 700685 belongs to a family of clones characterized by a 530-bp deletion in the leukotoxin gene operon. Members of this family are closely related and, according to Haubek et al. (23), have originated from a common ancestor. VT745, also known as JP2, represents the same unique clonal type. Since plasmid pVT745 did not hybridize to the genome of its host, VT745 (39), the lack of any significant homology to ATCC 700685 was not surprising. A search for components of a type IV secretion system on ATCC 700685 revealed the presence of VirB4 and VirB11 homologs only, although the corresponding genes were not similar to those on pVT745. Strain ATCC 700685 did not contain pVT745 or any other plasmid (unpublished). The clonal type with the 530-bp deletion has been described as being particularly virulent and contagious (23). The absence of a complete chromosomal type IV secretion system in ATCC 700685 and most of the A. actinomycetemcomitans strains examined suggests that, contrary to other pathogenic species, such a system does not appear to play a role in the virulence of A. actinomycetemcomitans-associated periodontal disease. However, it cannot be ruled out that a type IV secretion system is present and functional in specific A. actinomycetemcomitans strains.

Conclusions.

Plasmid pVT745 is a true composite with blocks of genes which seem to have been acquired from a variety of bacterial sources, such as Neisseria spp., Serratia spp., and the HAP family. We failed to identify genes with similarities to putative virulence factors, or antibiotic resistance genes. However, phenotypes other than conjugative transfer might be associated with one or more of the ORFs of unknown function. Significant sequence similarities were found at the protein level to bacteria belonging to the α, β, and γ subgroups of proteobacteria. This was particularly apparent with proteins encoded in the magB cluster, which is of a rather chimeric nature. Predicted proteins were homologous to chromosomally encoded components of type IV secretion systems present in Brucella abortus, Brucella suis, Helicobacter pylori, and Bordetella pertussis, all of which are associated with virulence, and to the highly similar plasmid-encoded proteins of gram-negative bacteria which were shown to be involved in conjugative DNA transfer (11). There is no simple single mechanism to explain this diversity in the magB gene cluster. O'Callaghan et al. (43) have suggested that the different protein secretion systems each evolved independently from the DNA transfer system. However, this assumption is not readily supported by the data presented in this report, since magB contains sets of genes with homologies to both DNA and protein secretion systems from a variety of plasmids and organisms. Since the arrangement of genes is very similar to those in other type IV secretion systems, it seems unlikely that these genes originated from different sources and were then arranged in the pattern found on pVT745. Such an explanation would also rely on extensive gene exchange between A. actinomycetemcomitans and other bacteria, yet there is currently no evidence for this. In addition, the pVT745 secretion system did not exhibit any significant similarities to the other systems at DNA level. It is possible that the pVT745-specific transfer system separated from the others early on and evolved independently. If this assumption is correct, the homologs detected in the chromosomes of various A. actinomycetemcomitans strains would indeed have been the result of an insertion of all or part of pVT745. This would raise the question as to the driving force(s) that caused the incorporation of pVT745 into bacterial chromosomes. No known insertion element or phages, or remnants thereof, were detected on pVT745, and one can only speculate if such elements were once present and then lost.

In conclusion, more data will be needed to explain the origin and/or evolution of pVT745 and its conjugation transfer system and the origin of sequences shared by the plasmid and various A. actinomycetemcomitans chromosomes. Among others, the precise location of these remnants on the host chromosomes and their respective nucleotide sequences will have to be compared. Future work will focus on the construction of defined nonpolar mutants for conjugation-associated genes and complementation analysis.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Micah Kerr and Jodie Polan-Curtain for technical assistance.

This study was supported by NIH grant R01 DE12107 to D.J.L., by Advanced Research Program grant 003659-021 from the Texas Higher Education Coordinating Board to D.J.L., and by NIH grant R29 DE12220 to K.F.N.

REFERENCES

- 1.Altschul S F, Madden T L, Schäffer A A, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Miller W, Lipman D J. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:3389–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anderson L B, Hertzel A V, Das A. Agrobacterium tumefaciens VirB7 and VirB9 form a disulfide-linked protein complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:8889–8894. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.17.8889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Andersson S G, Zomorodipour A, Andersson J O, Sicheritz-Ponten T, Alsmark U C, Podowski R M, Naslund A K, Eriksson A S, Winkler H H, Kurland C G. The genome sequence of Rickettsia prowazekii and the origin of mitochondria. Nature. 1998;396:133–140. doi: 10.1038/24094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Avila P, Nunez B, de la Cruz F. Plasmid R6K contains two functional oriTs which can assemble simultaneously in relaxosomes in vivo. J Mol Biol. 1996;261:135–143. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baron C, Llosa M, Zhou S, Zambryski P C. VirB1, a component of the T-complex transfer machinery of Agrobacterium tumefaciens, is processed to a C-terminal secreted product, VirB1. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:1203–1210. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.4.1203-1210.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bayer M, Eferl R, Zellnig G, Teferle K, Dijkstra A, Koraimann G, Högenauer G. Gene 19 of plasmid R1 is required for both efficient conjugative DNA transfer and bacteriophage R17 infection. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:4279–4288. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.15.4279-4288.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blattner F R, Plunkett III G, Bloch C A, Perna N T, Burland V, Riley M, Collado-Vides J, Glasner J D, Rode C K, Mayhew G F, Gregor J, Davis N W, Kirkpatrick H A, Goeden M A, Rose D J, Mau B, Shao Y. The complete genome sequence of Escherichia coli K-12. Science. 1997;277:1453–1474. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5331.1453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Censini S, Lange C, Xiang Z, Crabtree J E, Ghiara P, Brodovsky M, Rappuoli R, Covacci A. Cag, a pathogenicity island of Helicobacter pylori, encodes type I-specific and disease-associated virulence factors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:14648–14653. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.25.14648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chang Y F, Ma D P, Bai H Q, Young R, Struck D K, Shin S J, Lein D H. Characterization of plasmids with antimicrobial resistant genes in Pasteurella haemolytica A1. DNA Sequence. 1992;3:89–97. doi: 10.3109/10425179209034001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Christie P J. Agrobacterium tumefaciens T-complex transport apparatus: a paradigm for a new family of multifunctional transporters in eubacteria. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:3085–3094. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.10.3085-3094.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Christie P J, Vogel J P. Bacterial type IV secretion: conjugation systems adapted to deliver effector molecules to host cells. Trends Microbiol. 2000;8:354–360. doi: 10.1016/s0966-842x(00)01792-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Churchward G, Belin D, Nagamine Y. A pSC101-derived plasmid which shows no sequence homology to other commonly used cloning vectors. Gene. 1984;31:165–171. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(84)90207-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Covacci A, Rappuoli R. Pertussis toxin export requires accessory genes located downstream from the pertussis toxin operon. Mol Microbiol. 1993;8:429–434. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01587.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dixon L G, Albritton W L, Willson P J. An analysis of the complete nucleotide sequence of the Haemophilus ducreyi broad-host-range plasmid pLS88. Plasmid. 1994;32:228–232. doi: 10.1006/plas.1994.1060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dong X Q, Lindler L E, Chu M C. Complete DNA sequence and analysis of an emerging cryptic plasmid isolated from Yersinia pestis. Plasmid. 2000;43:144–148. doi: 10.1006/plas.1999.1432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fürste J P, Pansegrau W, Frank R, Blöker H, Scholz P, Bagdasarian M, Lanka E. Molecular cloning of the plasmid RP4 primase region in a multi-host-range tacP expression vector. Gene. 1986;48:119–131. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(86)90358-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Galli D M, LeBlanc D J. Characterization of pVT736–1, a rolling circle DNA plasmid from the gram-negative bacterium Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans. Plasmid. 1994;31:148–157. doi: 10.1006/plas.1994.1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Galli D M, LeBlanc D J. Transcriptional analysis of rolling circle replicating plasmid pVT736–1: evidence for replication control by antisense RNA. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:4474–4480. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.15.4474-4480.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Galli D M, Polan-Curtain J L, LeBlanc D J. Structural and segregational stability of various replicons in Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans. Plasmid. 1996;36:42–48. doi: 10.1006/plas.1996.0030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Galli D M, LeBlanc D J. Identification of a maintenance system on rolling circle replicating plasmid pVT736–1. Mol Microbiol. 1997;25:649–659. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.4991867.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Grahn A M, Haase J, Bamford D H, Lanka E. Components of the RP4 conjugative transfer apparatus form an envelope structure bridging inner and outer membranes of donor cells: implications for related macromolecule transport systems. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:1564–1574. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.6.1564-1574.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hallet B, Sherrat D J. Transposition and site-specific recombination: adapting DNA cut-and-paste mechanisms to a variety of genetic rearrangements. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 1997;21:157–178. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.1997.tb00349.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Haubek D, Poulsen K, Westergaard J, Dahlen G, Kilian M. Highly toxic clone of Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans in geographically widespread cases of juvenile periodontitis in adolescents of African origin. J Clin Micobiol. 1996;34:1576–1578. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.6.1576-1578.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Heeb S, Itoh Y, Nishijyo T, Schnider U, Keel C, Wade J, Walsh U, O'Gara F, Haas D. Small, stable shuttle vectors based on the minimal pVS1 replicon for use in gram-negative, plant-associated bacteria. Mol Plant-Microbe Interact. 2000;13:232–237. doi: 10.1094/MPMI.2000.13.2.232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hoffmann B, Strauch E, Gewinner C, Nattermann N, Appel B. Characterization of plasmid regions of foodborne Yersinia enterocolitica biogroup 1A strains hybridizing to the Yersinia enterocolitica virulence plasmid. Syst Appl Microbiol. 1998;21:201–211. doi: 10.1016/S0723-2020(98)80024-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Iida S, Sandmeier H, Hubner P, Hiestand-Nauer R, Schneitz K, Arber W. The Min DNA inversion system of plasmid p15B of Escherichia coli 15T: a new member of the Din family of site-specific recombinases. Mol Microbiol. 1990;4:991–997. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1990.tb00671.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Inouye S, Asai Y, Nakazawa A, Nakazawa T. Nucleotide sequence of a DNA segment promoting transcription in Pseudomonas putida. J Bacteriol. 1986;166:739–745. doi: 10.1128/jb.166.3.739-745.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jarosik G P, Hansen E J. Cloning and sequencing of the Haemophilus influenzae ssb gene encoding single-strand DNA-binding protein. Gene. 1994;146:101–103. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(94)90841-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kaplan J B, Fine D H. Codon usage in Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1998;163:31–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1998.tb13022.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kulaeva O I, Koonin E V, Wootton J C, Levine A S, Woodgate R. Unusual insertion element polymorphisms in the promoter and terminator regions of the mucAB-like genes of R471a and R446b. Mutat Res. 1998;397:247–262. doi: 10.1016/s0027-5107(97)00222-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.LeBlanc D J, Inamine J M, Lee L N. Broad geographical distribution of homologous erythromycin, kanamycin, and streptomycin resistance determinants among group D streptococci of human and animal origin. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1986;29:549–555. doi: 10.1128/aac.29.4.549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.LeBlanc D J, Abu-Al-Jaibat A R, Sreenivasan P K, Fives-Taylor P M. Identification of plasmids in Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans and construction of intergeneric shuttle plasmids. Oral Microbiol Immunol. 1993;8:94–99. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-302x.1993.tb00552.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lessl M, Krishnapillai V, Schilf W. Identification and characterization of two entry exclusion genes for the promiscuous IncP plasmid R18. Mol Gen Genet. 1991;227:120–126. doi: 10.1007/BF00260716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lessl M, Balzer D, Pansegrau W, Lanka E. Sequence similarities between the RP4 Tra2 and the Ti VirB region strongly support the conjugation model for T-DNA transfer. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:20471–20480. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Llosa M, Bolland S, de la Cruz F. Genetic organization of the conjugal DNA processing region of the IncW plasmid R388. J Mol Biol. 1994;235:448–464. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1994.1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lyras D, Chan A W S, McFarlane J, Stanisich V A. The surface exclusion system of RP1: investigation of the roles of the trbJ and trbK in the surface exclusion, transfer, and slow-growth phenotypes. Plasmid. 1994;32:254–261. doi: 10.1006/plas.1994.1064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Miller J H. Experiments in molecular genetics. Cold Spring Harbor, N. Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1972. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nielsen H, Engelbrecht J, Brunak S, von Heijne G. Identification of prokaryotic and eukaryotic signal peptides and prediction of their cleavage sites. Protein Eng. 1997;10:1–6. doi: 10.1093/protein/10.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Novak K F, LeBlanc D J. Characterization of plasmid pVT745 isolated from Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans. Plasmid. 1994;31:31–39. doi: 10.1006/plas.1994.1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Novak K F. Ph.D. thesis. San Antonio: University of Texas Health Science Center; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Novak K F, Lee L N, LeBlanc D J. Functional analysis of pVT745, a plasmid from Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans. Oral Microbiol Immunol. 1998;13:124–128. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-302x.1998.tb00723.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nunez B, Avila P, de la Cruz F. Genes involved in conjugative DNA processing of plasmid R6K. Mol Microbiol. 1997;24:1157–1168. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.4111778.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.O'Callaghan D, Cazevieille C, Ailardet-Servent A, Boschiroli M L, Bourg G, Foulongne V, Frutos P, Kulakov Y, Ramuz M. A homologue of the Agrobacterium tumefaciens VirB and Bordetella pertussis Ptl type IV secretion system is essential for intracellular survival of Brucella suis. Mol Microbiol. 1999;33:1210–1220. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01569.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Padmalayam I, Karem K, Baumstark B, Massung R. The gene encoding the 17-kDa antigen of Bartonella henselae is located within a cluster of genes homologous to the virB virulence operon. DNA Cell Biol. 2000;19:377–382. doi: 10.1089/10445490050043344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pansegrau W, Lanka E. Enzymology of DNA transfer by conjugative mechanisms. Prog Nucleic Acid Res Mol Biol. 1996;54:197–251. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6603(08)60364-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pohlman R F, Genetti H D, Winans S C. Entry exclusion of the IncN plasmid pKM101 is mediated by a single hydrophilic protein containing a lipid attachment motif. Plasmid. 1994;31:158–165. doi: 10.1006/plas.1994.1017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Segal G, Purcell M, Shuman H A. Host cell killing and bacterial conjugation require overlapping sets of genes within a 22 kb region of the Legionella pneumophila genome. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:1669–1674. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.4.1669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shine J, Dalgarno L. The 3′-terminal sequence of Escherichia coli 16S ribosomal RNA: complementarity to nonsense triplets and ribosome binding sites. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1974;71:1342–1346. doi: 10.1073/pnas.71.4.1342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Spudich G M, Fernandez D, Zhou X R, Christie P J. Intermolecular disulfide bonds stabilize VirB7 homodimers and VirB7/VirB9 heterodimers during biogenesis of the Agrobacterium tumefaciens T-complex transport apparatus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:7512–7517. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.15.7512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tettelin H, Saunders N J, Heidelberg J, Jeffries A C, Nelson K E, Eisen J A, Ketchum K A, Hood D W, Peden J F, Dodson R J, Nelson W C, Gwinn M L, DeBoy R, Peterson J D, Hickey E K, Haft D H, Salzberg S L, White O, Fleischmann R D, Dougherty B A, Mason T, Ciecko A, Parksey D S, Blair E, Cittone H, Clark E B, Cotton M D, Utterback T R, Khouri H, Qin H, Vamathevan J, Gill J, Scarlato V, Masignani V, Pizza M, Grandi G, Sun L, Smith H O, Fraser C M, Moxon E R, Rappuoli R, Venter J C. Complete genome sequence of Neisseria meningitides serogroup B strain MC58. Science. 2000;287:1809–1815. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5459.1809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Vogel J P, Andrew H L, Wong S K, Isberg R R. Conjugative transfer by the virulence system of Legionella pneumophila. Science. 1998;279:873–876. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5352.873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Weiss A A, Johnson F D, Burns D L. Molecular characterization of an operon required for pertussis toxin secretion. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:2970–2974. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.7.2970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Williams D R, Thomas C M. Active partitioning of bacterial plasmids. J Gen Microbiol. 1992;138:1–16. doi: 10.1099/00221287-138-1-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wood A R, Lainson F A, Wright F, Baird G D, Donachie W. A native plasmid of Pasteurella haemolytica serotype A1: DNA sequence analysis and investigation of its potential as a vector. Res Vet Sci. 1995;58:163–168. doi: 10.1016/0034-5288(95)90071-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wright C L, Strugnell R A, Hodgson A L M. Characterization of a Pasteurella multocida plasmid and its use to express recombinant proteins in P. multocida. Plasmid. 1997;37:65–79. doi: 10.1006/plas.1996.1276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yanish-Perron C, Vieira J, Messing J. Improved M13 phage cloning vectors and host strains: nucleotide sequences of the M13mp18 and pUC19 vectors. Gene. 1985;33:103–119. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(85)90120-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zambon J J. Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans in human periodontal disease. J Clin Periodontol. 1985;12:1–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1985.tb01348.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]