Abstract

Introduction:

Nucleoside analogues are an important class of antiviral agents. Due to the high hydrophilicity and limited membrane permeability of antiviral nucleoside/nucleotide analogs (AVNAs), transporters play critical roles in AVNA pharmacokinetics. Understanding the properties of these transporters is important to accelerate translational research for AVNAs.

Areas covered:

The roles of key transporters in the pharmacokinetics of 25 approved AVNAs were reviewed. Clinically relevant information that can be explained by the modulation of transporter functions is also highlighted.

Expert opinion:

Although the roles of transporters in the intestinal absorption and renal excretion of AVNAs have been well identified, more research is warranted to understand their roles in the distribution of AVNAs, especially to immune privileged compartments where treatment of viral infection is challenging. P-gp, MRP4, BCRP, and nucleoside transporters have shown extensive impacts in the disposition of AVNAs. It is highly recommended that the role of transporters should be investigated during the development of novel AVNAs. Clinically, co-administered inhibitors and genetic polymorphism of transporters are the two most frequently reported factors altering AVNA pharmacokinetics. Physiopathology conditions also regulate transporter activities, while their effects on pharmacokinetics need further exploration. Pharmacokinetic models could be useful for elucidating these complicated factors in clinical settings.

Keywords: antiviral agents, nucleoside/nucleotide analogs, pharmacokinetics, drug transporter, drug-drug interaction, genetic polymorphism

1. Introduction

Nucleoside/nucleotide analogs are synthetic, modified compounds that mimic naturally occurring nucleosides/nucleotides (most commonly adenosine, guanosine, cytidine, thymidine, uridine, and their corresponding nucleotides) [1]. Nucleoside/nucleotide analogs, often work as polymerase inhibitors or reverse transcriptase inhibitors and are an important group of antiviral drugs. Recently, research on antiviral nucleoside/nucleotide analogs (AVNAs) is growing. Many novel AVNA compounds continue to be synthesized and evaluated, underlining the interest in this group of drugs [2]. Several reviews extensively summarize their biochemistry, molecular regulation mechanism, tissue expression, and physiological function of drug transporter [2–7]. However, few reviews have focused on the roles of transporters in the pharmacokinetics of AVNAs. So far, there are 25 AVNAs approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. We aim to provide an overview of the roles of key transporters in the absorption, distribution, and elimination of these AVNAs, based on published preclinical and clinical data. Such information provides insight for future AVNA design and development.

2. Nucleoside/nucleotide analogs in antiviral treatment

2.1. Structure and physiochemical properties

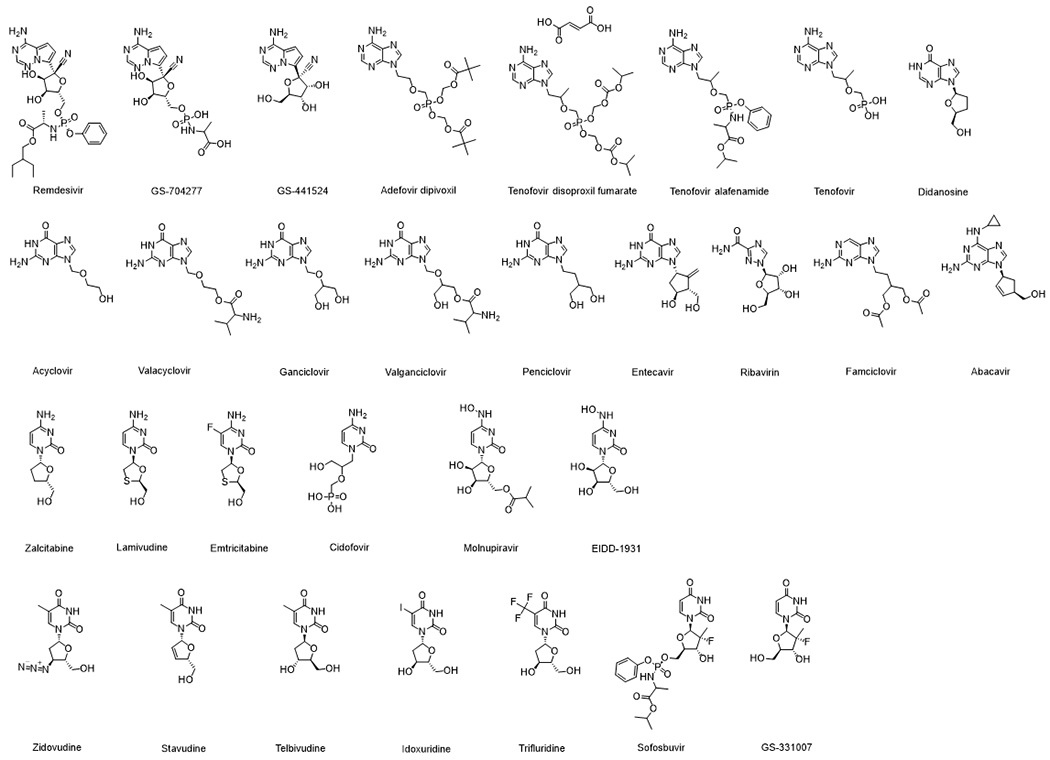

Nucleoside/nucleotide analogs have been approved for use in the treatment of various diseases. Antiviral and anticancer treatments are the two major applications [8]. Within viruses, DNA or RNA chain elongation requires the nucleoside to have triphosphate on its C-5 position and a hydroxyl group on its C-3 position. The structures of AVNAs discussed in the current review are shown in Figure 1. Many of the AVNAs are designed to terminate the viral DNA or RNA chain elongation process. Unlike most anticancer nucleoside/nucleotide analogs, which have an unmodified 3’-hydroxyl group, AVNAs often lack the 3’-hydroxyl group [9]. Nucleoside analogs share similar physicochemical characteristics: most approved AVNAs are neutral at physiological pH, except cidofovir and didanosine (anions). and valganciclovir and valaciclovir (cations). All approved AVNAs are relatively hydrophilic with logP ranging from −3.9 to 2.1 and water solubility no less than 0.023 mg/mL (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Structures of AVNAs discussed in the current review

Table 1.

Summary of clinical usage and physiochemistry characteristics of the approved antiviral nucleoside/nucleotide analogs

| Clinical Usage | Physiochemistry Characteristics c | BCS Class c | BDDCS Class d | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Drug | Target Virus | Route | Molecular Weight | Partition Coefficient | Water Solubility (mg/mL) | Prodrug Structure | ||

| Remdesivir | SARS-Cov-2 | IV | 602.59 | 2.1a | 0.023b | Phosphoramidite prodrug of a 1’-cyano-substituted adenosine nucleotide analog. | NA | 2 |

| Didanosine | HIV | Oral | 236.23 | −1.24 | 15.8 | NA | 3 | 3 |

| Adefovir dipivoxil | HBV | Oral | 501.47 | 1.91 (pH 7) | 19 | Diester prodrug of adefovir, an acyclic nucleotide analog of adenosine monophosphate | 3 | 3 |

| Tenofovir disoproxil fumarate | HIV, HBV | Oral | 519.45 | 1.25 (pH 6.5) | 13.4 | A prodrug of tenofovir (a nucleoside monophosphate analog) | 3 | 1 |

| Tenofovir alafenamide | HIV, HBV | Oral | 476.48 | 1.6 | 4.68 | A prodrug of tenofovir (a nucleoside monophosphate analog). | 3 | 1 |

| Acyclovir | HSV, HZV | Oral | 225.21 | −1.76 (pH 7.4) | 1.41 | NA | 3 | 4 |

| Valacyclovir | HSV, HZV | Oral | 324.34 | −0.3 | 174 | L-valine ester of acyclovir. A prodrug of acyclovir. | 3 | 1 |

| Ganciclovir | HSV, HZV, CMV | Oral/IV | 255.23 | −1.66 | 4.3 | NA | 3 | 3 |

| Valganciclovir | CMV | Oral | 354.37 | −1.0 a | 70 | L-valyl ester of ganciclovir. A prodrug of ganciclovir. | 3 | 1 |

| Penciclovir | HSV | Topical | 253.26 | −1.1 | 1.7 | NA | NA | NA |

| Famciclovir | HSV, HZV | Oral | 321.34 | 0.6 | >2000 | Diacetyl 6-deoxy prodrug of penciclovir | 3 | 1 |

| Entecavir | HBV | Oral | 277.28 | −0.8 | 2.4 | NA | 3 | 3 |

| Ribavirin | HBV, HCV, RSV | Oral | 244.21 | −1.85 | 10000 | NA | 3 | 1 |

| Abacavir | HIV | Oral | 286.34 | 1.2 (pH 7.2) | 77 | NA | 1 | 1 |

| Zalcitabine (discontinued) | HIV | Oral | 211.22 | −1.3 | 76.4 | NA | 3 | 3 |

| Lamivudine | HIV, HBV | Oral | 229.26 | −0.93 | 70 | NA | 3 | 3 |

| Emtricitabine | HIV | Oral | 247.25 | −0.43 | 112 | NA | 3 | 3 |

| Cidofovir | CMV | IV | 279.19 | −3.3 (pH 7.1) | 170 | NA | NA | NA |

| Molnupiravir | SARS-Cov-2 | Oral | 329.3 | 1.5 | 5.77 | 5’-isobutyrate prodrug of N4-Hydroxycytidine (EIDD-1931) | 3 | ND |

| Zidovudine | HIV | Oral | 267.25 | 0.05 | 20 | NA | 1 | 1 |

| Stavudine | HIV | Oral | 224.22 | −0.72 | 50 | NA | 1 | 3 |

| Telbivudine | HBV | Oral | 242.23 | −1.4 | >20 | NA | 3 | 3 |

| Idoxuridine | HSV | Topical | 354.10 | −0.96 | 2 | NA | NA | NA |

| Trifluridine | HSV | Topical | 296.20 | −0.46 | >10000 | NA | NA | NA |

| Sofosbuvir | HCV | Oral | 529.46 | 1.62 | 2 | NA | 3 | 1 |

Notes: NA: not applicable; ND: not determined ;

experimental data not available, predicted by ALOGPS;

experimental data not available, predicted by ADMET Predictor 9.0;

Data from PubChem.com or FDA labels;

Data from [25]

2.2. Pharmacology of AVNAs

Viruses can cause a variety of diseases in humans. The targets of approved AVNAs include cytomegalovirus (CMV) that causes mononucleosis or hepatitis; herpes zoster virus (HZV) and herpes simplex virus (HSV) that cause herpes; hepatitis B virus (HBV) and hepatitis C virus (HCV) that cause hepatitis; human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) that causes acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS); and respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) and severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) that cause pneumonia [1] (Table 1).

During DNA/RNA replication, endogenous nucleosides are phosphorylated by various host cell kinases into their active triphosphate form, then taken up by polymerases and incorporated into the growing DNA/RNA chain. Similarly, nucleoside/nucleotide analogs require intracellular activation by kinases to become their active triphosphate metabolites. Kinases responsible for the activation can be a specific virus-encoded thymidine kinase or cellular kinases not coded by viruses (Table 2) [10–13]. In some cases, nucleoside analogs are not recognized efficiently by kinases in their rate-limiting initial phosphorylation step [2]. Monophosphate analogs were designed to overcome this issue. For monophosphate nucleotide analogs, the phosphate group renders the molecule extremely polar, limiting their membrane permeability and distribution to therapeutic targets. Thus, prodrug strategies were employed to improve the cellular uptake and bioavailability, usually by introducing a hydrophobic ester group [8]. The structural modifications of these prodrugs are summarized in Table 1. For example, remdesivir is a monophosphoramidate prodrug of a 1’-cyano-substituted adenosine analog that can bypass the rate-limiting first phosphorylation step to effectively deliver its active triphosphate form inside infected cells (Table 1) [14,15].

Table 2.

Summary of pharmacokinetic characteristics of the approved antiviral nucleoside/nucleotide analogs in subjects with normal liver and kidney function

| Absorption | Distribution | Bioactivation | Elimination | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Drug | Route | F (%) | Tmax (h) | PPB (%) | B/P | Vd (L/kg) | CSF /plasma (%) | Hydrolysis of prodrug | Phosphorylation | metabolism | Urinary recovery (Composition c) | Fecal recovery | CL (mL/min) | T1/2 (h) |

| Remdesivir | IV | NA | NA | 88-94 | 0.68 | NR | NR | Forming GS-704277, then GS-441524 by esterasea | GS-704277 to the active TP by cellular kinases | Minor CYP3A metabolism (10%) | 63% (78% as GS-441524, 16% as unchanged). | NR | NR | 1 |

| Didanosine | Oral | 42 | NR | <5 | NR | 1.08 [IV] | 21 [IV] | NA | To the active TP by ADA | Catabolized by PNP to purine base | 18% (all as unchanged form) | NR | Total:845h Renal: 358 |

1.5 |

| Adefovir dipivoxil fumarate | Oral | 59 | 0.58 - 4 | ≤4 | NR | 0.35–0.39 | NR | Hydrolysis to adefovir by esterasea | Adefovir to the active TP by cellular kinases | NR | 45% (all as adefovir)b | NR | Total: 469 h | 7.48 |

| Tenofovir disoproxil fumarate b | Oral | 25 | 1 | <0.7 | NR | 1.2 [IV] | NR. | Rapidly hydrolysis to tenofovir by esterasea | Tenofovir to the active TP by cellular kinases | NR | 70–80% (all as tenofovir) | NR | Total: 1044 h Renal: 244 |

17 |

| Tenofovir alafenamide | Oral | NR | 0.48 | 80 | 1 | 1.67 | NR | Hydrolysis to tenofovir by esterasea | Tenofovir to the active TP by cellular kinases | CYP3A minimal metabolism | 36% (75% as tenofovir, a small fraction of uric acid and unchanged) | 47% [125] | Total: 1950 h | 0.51[126] |

| Acyclovir | Oral | 10-20 | 1.1 | 9-33 | NR | 0.6 | NR | NA | to the active acyclovir TP by TKd, GK, and subsequently cellular enzymesf [10] | Oxidized to 9-carboxymethoxymethylguanine (<15%) by ADH and ALDH | 90-92% (all as unchanged drug) | NR | Total:290h Renal: 248 |

2.5-3.3 |

| Valacyclovir d | Oral | 54.5 | NR | 13.5-17.9 | NR | NR | NR | Hydrolysis to acyclovir by hepatic valacyclovir hydrolase | Same as acyclovir | Same as acyclovir | 46% (89% as acyclovir) | 47% | Total:255h Renal: 225 |

2.5-3.3 |

| Ganciclovir | Oral/IV | 5 | 1.7-3 | 1-2 | NR | 0.64 [IV] | NR | NA | Phosphorylation to the active TP. by viral TK, and then by GK | NR | 90% (all as unchanged) b [IV] | 86% [Oral] | Total: 306 [IV] | 2.5-3.6 [IV] |

| Valganciclovir g | Oral | 60 | NR | 1-2 | NR | NR | NR | Hydrolysis to ganciclovir by intestinal and hepatic esterase. | Same as ganciclovir. | NR | Major (all as ganciclovir) | NR | Renal:195 h | 0.4-1.99 |

| Famciclovir | Oral | 77 | 0.9 | <20 | 1 | 1.08 | NR | Hydrolysis to penciclovir | Phosphorylation to the active penciclovir TP by viral TK and then cellular kinases | Forms 6-deoxy penciclovir (5%), monoacetylated penciclovir (0.5%), and 6-deoxy monoacetylated penciclovir (0.5%) by ALDH | Major (all as penciclovir) | NR. | Total: 67 h Renal:30 |

2.3-2.8 |

| Entecavir | Oral | NR | 0.5-1.5 | 13 | NR | NR | NR | NA | Activated to TP form by cellular kinase | Minor amounts of phase II metabolites (glucuronide and sulfate conjugates) | 62-73% (unchanged drug) | NR | Total:588h Renal: 383 |

128-149 |

| Ribavirin | Oral | 64 | 1-1.7 | NR | 44 | NR. | NA | Reversible phosphorylation to the active TP by AK. | Deribosylation and amide hydrolysis to a triazole carboxylic acid metabolite. | 61% (27.8% as unchanged) | 12% | Total: 433 h | 43.7 | |

| Abacavir | Oral | 83 | NR | 50 | 1 | 0.86 [IV] | 36 [51] | NA | Activated to carbovir TP | Forms 5′-carboxylic acid metabolite by ADH and 5′-glucuronide by UGT. | 82% (1.5% as abacavir, 44% as 5′-glucuronide, 36% as 5′-carboxylic acid). | 16% | Total: 867 [IV] | 1.54 |

| Zalcitabine | Oral | >80 | 0.8-1.6 | NR | 0.534 | 9-37 | NA | Activated to TP form by cellular kinase | Very minor hepatic metabolism to dideoxyuridine (ddU) | 60% (as unchanged) <15% (as ddU) |

10% (as unchanged and ddU) | Total:285 h | 2 | |

| Lamivudine | Oral | 86 | 0.9-3.2 | <36 | 1.1 - 1.2 | 1.3 | NR | NA | Activated to TP form by cellular kinase | Forms trans-sulfoxide metabolite (5%) by sulfotransferases | Major (mostly as unchanged) | NR | Total:398; Renal: 280 [IV] | 5-7 |

| Emtricitabine | Oral | 75-93 | 1-2 | <4e | 0.6 | NR | 26 [53] | NA | Activated to TP form by cellular kinase | Forms 3’-sulfoxide diastereomers (9%), 2’-O-glucuronide (4%), and minor 5-fluorocytosine. | 86% (85% as unchanged, 10% as 3’-sulfoxide diastereomers and 5% as 2’-O-glucuronide) | 14% | Total:302h Renal:213 (70.5%) |

10 |

| Cidofovir | IV | NA | NA | 6 | NR | 0.537 | <1 | NA | Activated by cellular kinase | NR | 70-85% (unchanged) | NR | Total: 179 Renal: 150 |

2.4-3.2 |

| Molnupiravir i | Oral | NR | 1.5 | 0 | NR | 2.2 | NR | Hydrolysis during/after absorption to EIDD-1931 | EIDD-1931 is phosphorylated to form the active triphosphate | NR | 3% | NR | Total: 1281 | 3.3 |

| Zidovudine | Oral | 64 | NR | <38 | NR | 1.6 | 60 | NA | Activated to TP form by cellular kinase | Reduced to 3’-amino-3’-deoxythymidine (AMT) by CYPs. Forms major metabolite, 3′-azido-3′-deoxy-5′-O-beta-D-glucopyranuronosylthymidine (GZDV) by UGTs. | 88% (16% as unchanged and about 84% as GZDV) | NR. | Total: 1733 Renal: 368 |

0.5 - 3 |

| Stavudine | Oral | 86 | <1 | <1 | 1 | 0.77 | NR | NA | Activated to TP form by cellular kinase | Minor metabolites: oxidative metabolites, glucuronide conjugates, and N-acetylcysteine conjugate of the ribose after glycosidic cleavage, and thymine. | 42% (as unchanged) | NR. | Total: 594; Renal: 237 |

1.6 |

| Telbivudine | Oral | NR | 2 | 3.3 | 1 | NR | NR | NA | Activated to TP form by cellular kinase | NR | 42% (as unchanged drug) | NR | Total: 127 Renal: 126 |

40-49 |

| Sofosbuvir | Oral | NR | 0.5-2 | 61-65 | 0.7 | NR | NR | Hydrolysis by esterasesa Phosphoramidate cleaved by HTNB1 to an MP form intermediate | CMPK and NDPK to form the active GS-331007 TP, which is easily dephosphorylated to GS-331007 | NR | 80% (78% as GS331007, 3.5% as unchanged form) | 14% | NR | 0.4 |

Abbreviation: NR no reports, NA not applicable, MP monophosphate, DP diphosphate, TP triphosphate, PNP Purine-nucleoside phosphorylase, ADA adenosine deaminase, TK thymidine kinase, GK guanylate kinase, AK adenosine kinase, ADH: alcohol dehydrogenase, ALDH: aldehyde dehydrogenase, HTNB1 histidine triad nucleotide-binding protein 1, CMPK cytidine/uridine monophosphate kinase, NDPK nucleoside diphosphate kinase, UGT: Uridine 5’-diphospho-glucuronosyltransferase, CYPs: cytochromes P450, F: oral bioavailability, Tmax: time for reaching the maximum concentration in plasma, PPB: plasma protein binding ratio, B/P: blood-to-plasma ratio, Vd Apparent volume of distribution, CL: clearance, T1/2 : plasma half-life.

Notes:

Mostly carboxylesterase 1 or cathepsin A;

Parameters (F, Tmax PPB, Vd, T1/2, and CL) are determined for tenofovir;

Composition presented as percentage of the total recovered dose in the urine;

Parameters (F, T1/2, and CL,) are determined for acyclovir;

Binding to albumin;

Includes nucleoside diphosphate kinase, pyruvate kinase, creatine kinase, phosphoglycerate kinase, succinyl-CoA synthetase, phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase, and adenylosuccinate synthetase;

Parameters (F, PPB, T1/2, and CL) are determined for ganciclovir;

Clearance after oral administrate is presented as CL/F;

Parameters (F, Tmax PPB, Vd, T1/2, and CL) are determined for EIDD-1931

After the nucleoside triphosphate is formed in the cell, they can be either hydrolyzed to the corresponding di- and mono-phosphate and its nucleoside or incorporated into cellular/viral DNA and RNA. Under physiological conditions, the cell membrane is not permeable to nucleotide triphosphate due to its high polarity. However, sometimes physiological nucleotide triphosphates are also released from cells as intercellular signaling messengers (such as adenosine-5’-triphosphate ATP, guanosine-5’-triphosphate GTP, and uridine-5′-triphosphate UTP). The release of physiological nucleotide triphosphates is often carried out by exocytotic release or by plasma membrane channels [16,17]. However, whether these physiological extracellular release mechanisms also apply for the AVNA triphosphate remains unclear.

3. Transporters and their substrate selectivity towards AVNAs

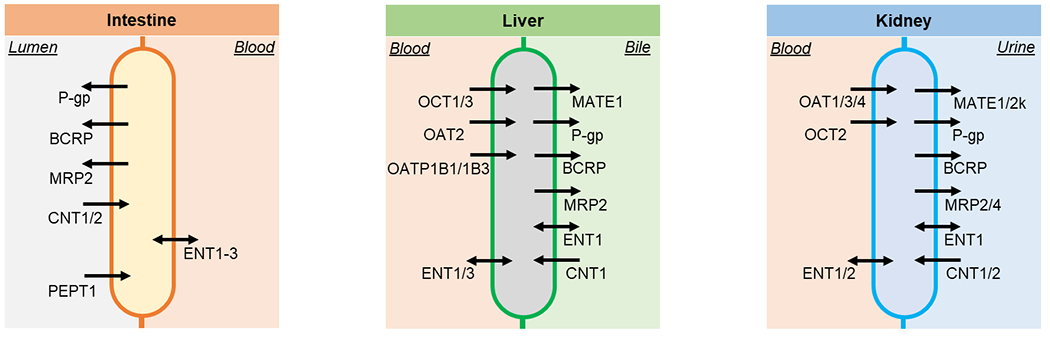

Transporters play critical roles in the absorption, distribution, and elimination of AVNAs (Figure 2). There are currently more than 400 identified membrane transporters and the majority belong to two superfamilies: solute carrier (SLC) transporters and ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporters. SLC transporters utilize the energy stored in the ion gradient, while ABC transporters utilize the energy released by ATP hydrolysis [2–7].

Figure 2.

Transporters related to the absorption, disposition, and elimination of antiviral nucleoside/nucleotide analogs discussed in the current review on intestine, liver, and kidney cell membranes.

3.1. SLC transporters

The SLC family includes several transporters that play important roles in drug disposition, including organic anion-transporting proteins (OATPs), organic anion and cation transporters (OATs and OCTs), peptide transporters (PEPTs), and multi-antimicrobial extrusion (MATEs) [3].

Among the 14 AVNAs and their metabolites that have been tested, five of them are substrates of OCTs, including zalcitabine for both OCT1 and OCT2 and lamivudine for OCT1-3. For all the tested AVNAs, their Km values for OCTs range from 0.15 – 2 mM (Table 3). Endogenous choline, guanidine, and monoamine neurotransmitters are substrates of OCTs [18]. OCTs usually interact with monovalent or bivalent cations with molecular mass less than 500 and the smallest diameter being below 4 Å [3]. Compared with OCTs, OATs transfer more AVNAs. Among the 16 tested, eight have been identified as substrates for OAT1, and tenofovir, acyclovir, and zidovudine have been identified as substrates of both OAT1/3. Km values of OAT substrates range from 0.02 – 0.9 mM (Table 3), generally lower than that of OCT substrates. OATs usually interact with monovalent or divalent anions with molecular masses below 500 [3]. In addition to being identified as substrates, acyclovir, ganciclovir, and zidovudine have also been identified as inhibitors of OAT1/3. PEPTs usually mediate the uptake of oligopeptides. Only the prodrug valacyclovir and valganciclovir, both with the L-valine group added on their structures (Table 1), have been found as substrates of PEPT1 and PEPT2. Among eight tested, four AVNAs have been identified as substrates of MATE1 and/or MATE2K (Table 5), which are the efflux transporters highly expressed in the apical side of the renal epithelial cells (Figure 2).

Table 3.

Summary of antiviral nucleoside analogs as substrates and modulators of human uptake transporters

| Transporter (Km (mM)) | OCT1 | OCT2 | OCT3 | OAT1 | OAT2 | OAT3 | OAT4 | ASBT | OATP 1B1 | OATP 1B3 | PEPT1 | PEPT2 | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||||||

| Gene | SLC 22A1 | SLC 22A2 | SLC 22A3 | SLC 22A6 | SLC 22A7 | SLC 22A8 | SLC 22A11 | SLC 10A2 | SLC O1B1 | SLC O1B3 | SLC 15A1 | SLC 15A2 | |

|

| |||||||||||||

| Remdesivir | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | sub | sub | - | - | [11,76] |

| inh | inh | ||||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||

| GS-441524 | nsub | nsub | - | nsub | - | nsub | - | - | nsub | nsub | - | - | [11] |

|

| |||||||||||||

| GS-704277 | nsub | nsub | - | nsub | - | nsub | - | - | sub | sub | - | - | [11] |

|

| |||||||||||||

| Adefovir | - | - | - | sub (0.03) | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | [127] |

|

| |||||||||||||

| Tenofovir alafenamide fumarate | - | - | - | nsub | - | nsub | - | - | sub | sub | - | - | [67,128] |

|

| |||||||||||||

| Tenofovir | - | - | - | sub (0.02) | - | sub | - | - | - | - | - | - | [129] |

|

| |||||||||||||

| Valacyclovir | nsub | nsub | - | nsub | nsub | sub | - | sub | - | - | sub | sub | [130–132] |

| inh | inh | ||||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||

| Acyclovir | sub (0.15) | nsub | - | sub (0.3) | nsub | sub | nsub | sub[131] | - | - | - | - | [130,131,133] |

| inh | ninh | inh | ninh | inh | ninh | ||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||

| Valganciclovir | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | sub | sub | [134] |

| inh | inh | ||||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||

| Ganciclovir | sub (0.5) | nsub | - | sub (0.9) | nsub | nsub | nsub | - | - | - | nsub | nsub | [130,132,134] |

| inh | ninh | inh | inh | inh | ninh | ninh | ninh | ||||||

|

| |||||||||||||

| Entecavir | - | nsub | sub | sub (0.3) | nsub | - | - | - | - | - | [135,136] | ||

|

| |||||||||||||

| Abacavir | nsub | nsub | - | nsub | - | - | - | - | nsub | nsub | - | - | [137] |

| ninh | ninh | - | - | - | - | ninh | ninh | ||||||

|

| |||||||||||||

| Zalcitabine | sub | sub | - | sub | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | [138,139] |

| (0.2) | (0.2) | ||||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||

| Lamivudine | sub (0.25-1.25) | sub (0.25-2) | sub (2) | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | [129,138,140] |

| inh | inh | ||||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||

| Emtricitabine | nsub | nsub | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | [141] |

|

| |||||||||||||

| Cidofovir | - | - | - | sub | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | [142,143] |

| inh | |||||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||

| Molnupiravir | nsub | nsub | - | nsub | - | nsub | - | - | nsub | nsub | - | - | [144] |

|

| |||||||||||||

| EIDD-1931 | nsub | nsub | - | nsub | - | nsub | - | - | nsub | nsub | - | - | [144] |

|

| |||||||||||||

| Zidovudine | nsub | nsub | - | sub (0.05) | sub (0.03) | sub (0.15) | sub (0.15) | - | - | - | - | - | [130] |

| ninh | ninh | inh | inh | inh | inh | ||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||

| Sofosbuvir | ninh | ninh | ninh | [13] | |||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||

| GS-331007 | nsub | - | nsub | - | - | - | - | - | [13] | ||||

| ninh | ninh | ninh | ninh | ninh | ninh | ||||||||

Abbreviation: MP: monophosphate; nsub: not a substrate; sub: substrate; ninh: not an inhibitor; inh: inhibitor; ind: inducer; -: no information reported; Km (mM) value reported is labeled in bracket.

Table 5.

Summary of antiviral nucleoside analogs as substrates and modulators of human efflux transporters

| Transporter (Km (mM)) | MATE1 | MATE2K | BCRP | P-gp | MRP2 | MRP4 | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| Gene | SLC47A1 | SLC47A2 | ABCG2 | ABCB1 | ABCC2 | ABCC4 | |

|

| |||||||

| Remdesivir | - | - | - | sub | - | - | [11,76] |

| ninh | ninh | inh | |||||

|

| |||||||

| GS-441524 | nsub | nsub | sub | sub | - | - | [11,76] |

| ninh | ninh | ||||||

|

| |||||||

| GS-704277 | nsub | nsub | - | - | - | - | [11,76] |

| inh | ninh | ||||||

|

| |||||||

| Didanosine | - | - | nsub | - | - | sub | [156] |

| ninh | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Adefovir | - | - | nsub | nsub | sub | [152,157] | |

|

| |||||||

| Tenofovir disoproxil fumarate | - | - | sub | sub | - | sub | [12,87,158,159] |

| inh | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Tenofovir alafenamide fumarate | - | - | sub | sub | - | - | [153,160] |

| ninh | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Tenofovir | - | nsub | nsub | nsub | sub | [78,129,161] | |

| - | - | inh | |||||

|

| |||||||

| Acyclovir | sub | sub | - | - | - | - | [162] |

|

| |||||||

| Ganciclovir | sub | sub | - | - | - | sub | [162,163] |

|

| |||||||

| Entecavir | - | - | sub | - | - | sub | [136,164] |

|

| |||||||

| Abacavir | nsub | nsub | sub | sub | nsub | nsub | [137] |

| ninh | ninh | ninh | ninh | ||||

|

| |||||||

| Zalcitabine | - | - | inh | - | - | - | [129] |

|

| |||||||

| Lamivudine | sub | sub | sub (0.2) | sub (weak) | - | sub | [21,40,164–166] |

|

| |||||||

| Emtricitabine | sub | - | nsub | nsub | nsub | - | [141,167,168] |

| ind | inh | ||||||

|

| |||||||

| Molnupiravir | nsub | nsub | [169] | ||||

| ninh | ninh | ninh | ninh | ninh | |||

|

| |||||||

| EIDD-1931 | nsub | nsub | [169] | ||||

|

| |||||||

| Zidovudine | - | - | sub | sub/nsub | - | sub | [21,22,40,129,152–154] |

| inh | ninh | ||||||

|

| |||||||

| Zidovudine MP | - | - | sub | - | - | sub | [40,152] |

|

| |||||||

| Stavudine | - | - | - | ind | - | - | [167] |

|

| |||||||

| Sofosbuvir | - | - | sub | sub | - | - | [13] |

| ninh | ninh | ||||||

|

| |||||||

| GS-331007 | nsub | - | nsub | nsub | - | - | [13] |

| ninh | ninh | ninh | |||||

|

| |||||||

| ninh | ninh | ninh | ninh | ninh | |||

Abbreviation: MP: monophosphate; nsub: not a substrate; sub: substrate; ninh: not an inhibitor; inh: inhibitor; ind: inducer; -: no information reported; Km (mM) value reported is labeled in bracket.

Nucleoside transporters also belong to the SLC family. In cells that lack de novo synthesis pathways and require salvage pathways to produce nucleotides, there are two major nucleoside transporters usually present: the concentrative nucleoside transporters (CNT1-3) and the equilibrative nucleoside transporters (ENT1-4). ENTs have a role in bidirectional equilibrative processes maintaining nucleoside homeostasis, whereas CNTs contribute to unidirectional concentrative processes, such as nucleoside transduction [5,19]. CNTs are exclusively expressed in apical membranes favoring nucleoside transepithelial influx, whereas ENTs are found on both basolateral and apical surfaces [5]. ENT4 is an ancient divergent from ENT1-3 with a much lower affinity only towards adenosine [19]. Substrate/inhibitor screenings on ENT4 are still relatively rare. Both CNT and ENT transporters also mediate the uptake of many nucleoside analogs [20]. CNT subtypes have a preference for their endogenous substrates. CNT1 transports pyrimidines, and CNT2 carries purines, whereas CNT3 mediates uptake of both [20]. For AVNAs, among the five pyrimidine analogs tested, three of them have been found substrates for CNT1, while three out of four tested purine analogs have been found to be substrates of CNT2. CNT3 was found to mediate the uptake of six AVNAs from a total of seven tested. For ENTs, nearly all tested AVNAs were confirmed as their substrates (Table 4). The Km values tested for nucleoside transporters vary a lot among different AVNAs, ranging from 0.01 mM to 15 mM (Table 4). In terms of modulation on transporters, it is generally considered that a 3’-hydroxyl group is essential for inhibition of nucleoside transporters. Remdesivir and molnupiravir both provide a free 3’-hydroxyl group. Remdesivir and the active metabolite of molnupiravir (EIDD-1931) have been identified as inhibitors of ENTs.

Table 4.

Summary of antiviral nucleoside analogs as substrates and modulators of human nucleoside transporters

| Transporter (Km (mM)) | CNT1 | CNT2 | CNT3 | ENT1 | ENT2 | ENT3 | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| Gene | SLC28A1 | SLC28A2 | SLC28A3 | SLC29A1 | SLC29A2 | SLC29A3 | |

|

| |||||||

| Remdesivir | - | - | - | sub | sub | - | [145] |

| inh | inh | ||||||

|

| |||||||

| GS-441524 | nsub | nsub | sub | sub | sub | - | [146] |

|

| |||||||

| Didanosine | - | sub | sub | sub (2.3-3.0) | sub (3.5) | sub | [5,142,147,148] |

|

| |||||||

| Ganciclovir | - | - | nsub | - | - | sub | [142,147] |

|

| |||||||

| Entecavir | - | sub (0.05-1.5) | sub (0.02-0.1) | sub | sub[136] | - | [135,136] |

|

| |||||||

| Ribavirin | - | sub (0.02) | sub (0.01) | sub (0.16 – 3.5) | sub (4) | sub | [6,149] |

|

| |||||||

| Abacavir | - | - | - | sub | - | - | [150] |

|

| |||||||

| Zalcitabine | nsub | - | sub | sub | sub (>7.5) | sub | [142,147,148,151] |

|

| |||||||

| Lamivudine | nsub | - | - | - | - | sub | [6,151] |

|

| |||||||

| Molnupiravir | sub | - | - | nsub | nsub | - | [144,145] |

|

| |||||||

| EIDD-1931 | sub | sub | sub | sub | sub | - | [144,145] |

| inh | inh | ||||||

|

| |||||||

| Zidovudine | sub (1) | - | sub | nsub | sub | sub | [21,22,40,129,152–154] |

| inh | ind | ||||||

|

| |||||||

| Stavudine | sub (15) | - | sub | - | - | sub | [6,151] |

|

| |||||||

| Trifluridine | sub | - | - | sub | sub | - | [155] |

Abbreviation: nsub: not a substrate; sub: substrate; ninh: not an inhibitor; inh: inhibitor; ind: inducer; -: no information reported; Km (mM) value reported is labeled in bracket.

3.2. ABC transporters

ABC transporters mainly act as exporters. Among them, P-glycoprotein (P-gp or MDR1), multidrug resistance-associated proteins (MRPs), and breast cancer resistance protein (BCRP) are mostly recognized for their importance in drug disposition [3]. P-gp has a broad substrate specificity, eight out of 13 tested AVNAs and their metabolites were identified as P-gp substrates, among which lamivudine and zidovudine were considered weak substrates with either low efflux ratio (about 2) [21] or contradictory results from different studies [21,22] (Table 5). Among the 16 AVNAs and their metabolites tested, 9 were found substrates of BCRP (Table 5). Based on a previous quantitative structure-activity relationship model, compounds with an amine bonded to a carbon of a heterocyclic carbon, a fused heterocyclic ring, and two substituents on a carboxylic ring of the fused heterocyclic ring are moieties important for inhibition of BCRP[23]. Two AVNAs, namely zalcitabine and zidovudine, have been found inhibitors of BCRP, while sofosbuvir and molnupiravir and their active metabolite have been found not an inhibitor of BCRP (Table 5). Substrates of MRP2 are often phase II metabolites including sulfate-, glutathione-, and glucuronide-conjugates [3]. Only three AVNAs, tenofovir, emtricitabine, and abacavir, have been tested on MRP2, and all of them were not found to be substrates. MRP4, an important renal transporter, was also found to be frequently involved in the transport of AVNAs. Among the 11 AVNAs tested, 9 of them have been discovered as substrates of MRP4 (Table 5).

4. Transporters in the absorption of antiviral nucleoside/nucleotide analogs

4.1. Oral absorption of antiviral nucleoside/nucleotide analogs

Due to its non-invasiveness, patient compliance, and convenience, oral administration is the preferred route of administration. Among the 25 approved AVNAs, 19 of them have oral formulations. Two (cidofovir and remdesivir) have intravenous injection formulations, and three (idoxuridine, penciclovir, and trifluridine) are formulated for topical/ophthalmic treatment of HSV only. Most oral AVNAs are drugs with high solubility and limited membrane permeability. According to the Biopharmaceutics Classification System (BCS) [24], all approved AVNAs have been considered as BCS class III compounds, except for stavudine, abacavir, and zidovudine, which are considered BCS class I compounds (Table 1). In addition, Biopharmaceutics Drug Disposition Classification System (BDDCS) was used to evaluate the role of transporters in the absorption and metabolism process of a drug [25]. Nine AVNAs, mostly ester prodrugs, are BDDCS class I compound, with minimal transporter effect in their absorption and metabolism process. Another nine AVNAs are BDDCS class III compounds, with absorptive transporter effects predominant in their absorption and metabolism process.

4.2. Transporters related to the oral absorption of antiviral nucleoside/nucleotide analogs

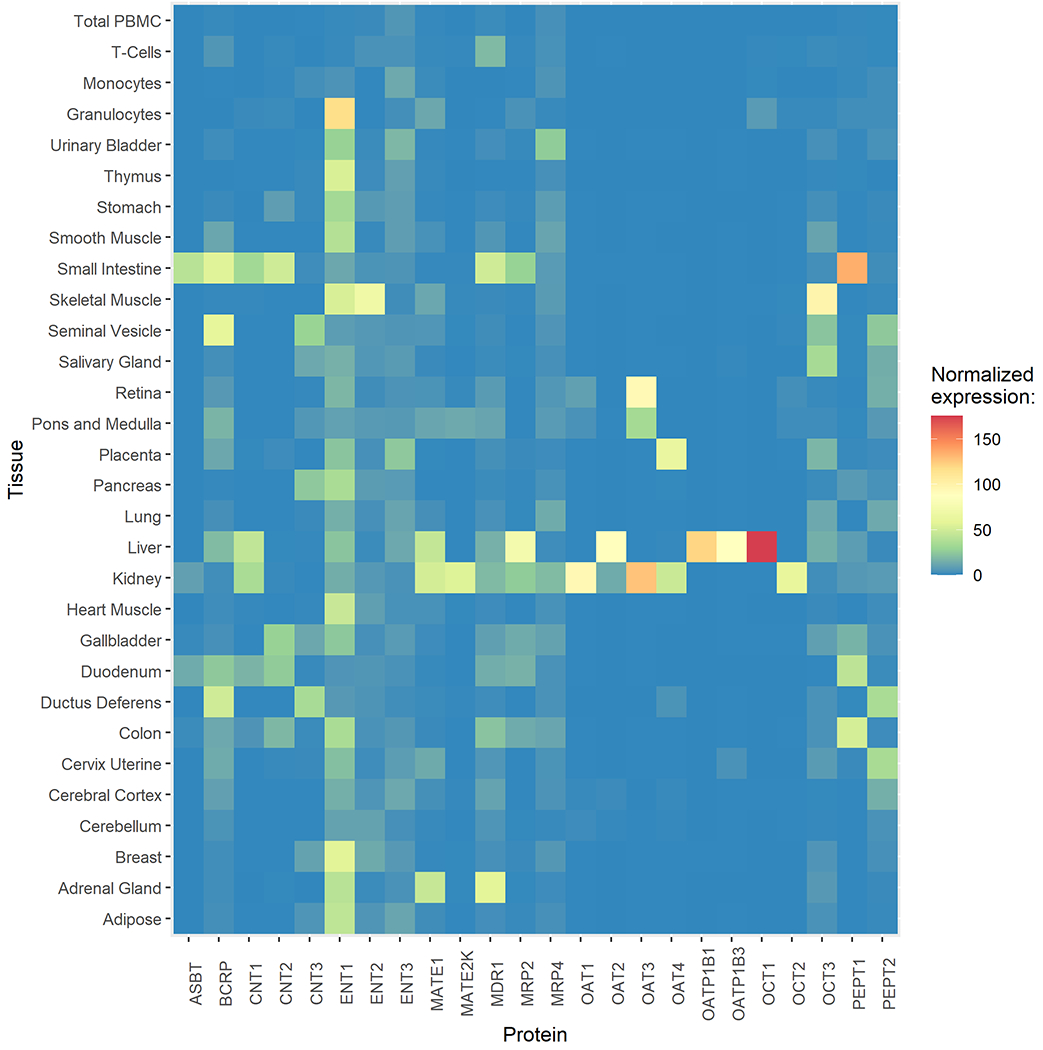

In the human small intestine, where the majority of absorption happens, several transporters are expressed to efflux or uptake drugs (Figure 2). According to the mRNA level determined by microarray, P-gp, CNT1, CNT2, and PEPT1 have the highest expression, followed by BCRP and MRP2. Additionally, ENT1-2 also have minor expression (Figure 3) [26,27].

Figure 3.

Transcript expression levels of drug transporters in various tissues

Efflux transporters at the apical membrane of enterocytes restrict the absorption of oral AVNAs. P-gp and BCRP are two major efflux transporters in the intestine [3]. Many oral AVNAs are substrates of both P-gp and BCRP (Table 5). Clinically, substrates of P-gp and BCRP could be victims of co-administered inhibitors. For example, the clinical pharmacokinetic profile of sofosbuvir, a substrate of both BCRP and P-gp, was affected by other co-administered anti-HIV regimens. A clinical trial on healthy volunteers reported that compared with sofosbuvir alone, sofosbuvir exposures were 61% (Cmax) and 112% (AUClast) higher with the 3D regimen (consists of paritaprevir/ritonavir, ombitasvir, and dasabuvir) and 64% (Cmax) and 93% (AUClast) higher with the 2D regimen (consists of paritaprevir/ritonavir and ombitasvir). The increase in sofosbuvir exposure presumably resulted from the inhibition of BCRP and/or P-gp by paritaprevir/ritonavir (Table 6) [28].

Table 6.

Clinical significance of transporter inhibition on the pharmacokinetics of antiviral nucleoside analogs

| Drug | Co-administered drug | Subjects | Inhibited transporters | Pharmacokinetic impact | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tenofovir disoproxil fumarate | Lopinavir/ritonavir | HIV patients | OAT3 MRP4 | After adjusting for renal function, tenofovir renal clearance was 17.5% slower (p = 0.04) in subjects taking lopinavir/ritonavir versus those not taking a protease inhibitor. | [85] |

| Tenofovir disoproxil fumarate | Lopinavir/ritonavir | HIV patients | OAT3 MRP4 | Concomitant use of lopinavir/ritonavir was associated with tenofovir apparent oral clearance (CL/F) | [170] |

| Tenofovir disoproxil fumarate | Lopinavir/ritonavir | Healthy volunteers | OAT3, MRP4, P-gp | Tenofovir measurements with AUC, Cmax, Ctrough were 32%, 15%, and 51% higher, respectively, when tenofovir disoproxil fumarate was co-administered with lopinavir/ritonavir. No changes were observed in renal function. | [80] |

| Tenofovir disoproxil fumarate | Atazanavir | HIV patients | OAT3, MRP4, P-gp | Cotreatment with atazanavir increase the exposure of tenofovir by 14% in Cmax and 24% in AUC | [12] |

| Tenofovir disoproxil fumarate | Lopinavir/ritonavir | HIV patients | OAT3 MRP4 | In women not receiving lopinavir/ritonavir (n = 28), tenofovir AUClast was 27% lower (p = 0.002) and oral clearance was 27% higher (p = 0.001) during the third trimester compared to paired postpartum data. In women receiving lopinavir/ritonavir (n = 10), tenofovir AUClast and oral clearance were not different antepartum compared to postpartum. Pregnancy confounds the expected decrease in tenofovir exposure with concomitant lopinavir/ritonavir in non-pregnant adults. | [113] |

| Adefovir | Probenecid or p-aminohippurate | Healthy volunteers | OAT1 | The renal clearance of adefovir was reduced by 45% and 46% in the subjects treated with the maximum dose of probenecid and p-aminohippurate, respectively | [171] |

| Sofosbuvir | Paritaprevir/ritonavir | Healthy volunteers | BCRP P-gp | When sofosbuvir was co-administered with two BCRP and P-gp inhibitors, paritaprevir and ritonavir, the AUClast of GS-331007 were 27-32% higher than that when sofosbuvir was administered alone. | [28] |

| Sofosbuvir | Paritaprevir/ritonavir | Healthy volunteers | BCRP P-gp | The Cmax central values increased by 66%, and the AUC central values increased by 125% for sofosbuvir in combination with glecaprevir/pibrentasvir. Exposure of sofosbuvir metabolite GS-331007 was similar with or without glecaprevir/pibrentasvir. | [172] |

| Ribavirin | High purine meal | Healthy volunteers | CNT2 | In comparison with corresponding plasma values of ribavirin following a high-purine meal, Cmax, and AUClast of ribavirin following a low-purine meal were 136%, and 134%, respectively. | [173] |

| Valacyclovir | Probenecid | Healthy volunteers | OATs | Probenecid increased Cmax of Valaciclovir by 23 % and the AUC for Valaciclovir by 22%. Probenecid also increased the mean Acyclovir Cmax by 22% and its AUC by 48%. | [74] |

| Cidofovir | Probenecid | HIV patients | OATs | Concomitant administration of probenecid appeared to completely block the tubular active secretion of cidofovir and reduce its renal clearance to a level approaching glomerular filtration. | [75] |

In addition to the general efflux transporters highly expressed in enterocytes, uptake transporters such as PEPTs and OCTs are also present for the intestinal uptake of AVNAs. The peptide transporter PEPT1 facilitates the absorption of the two prodrugs, valacyclovir and valganciclovir (Table 3). By using a mouse PEPT1 knock-out model, it was demonstrated that intestinal PEPT1 significantly improved the rate and extent of oral absorption for valacyclovir [29]. Furthermore, nucleoside transporters could also be crucial in determining the bioavailability of oral AVNAs [20]. Based on their mRNA levels, CNT1 and CNT2 are highly expressed in the duodenum, jejunum, and ileum, whereas CNT3 is broadly distributed throughout the digestive system, including the stomach, colon, and rectum, with constant lower expression [6]. ENT1 is highly expressed in the stomach, while ENT2 is mainly distributed in the stomach and duodenum [6]. Many AVNAs were found to be reliant on nucleoside transporters in the intestine to cross cell membranes (Table 4). Polymorphism of these uptake transporters in the intestine may alter the bioavailability of AVNAs. One example is ribavirin, a substrate for CNT2, CNT3, and ENT1-3. CNTs have been considered responsible for the saturable absorption of ribavirin [30]. A cohort study on HCV-positive patients revealed that variability in ribavirin serum levels was associated with a single nucleotide polymorphism of CNT2 (SLC28A2 124C>T, rs11854484). Patients carrying this variant in homozygosis had higher dosage- and body weight-adjusted ribavirin steady-state blood levels at week 4 and 8 compared to the wild type and heterozygosis carriers [31].

AVNAs can also regulate the function of specific transporters in the intestine and possibly influence the absorption of other orally co-administered drugs. For example, tenofovir disoproxil fumarate and lamivudine have been identified not only as substrates but also inhibitors of P-gp. Clinically, the combined use of tenofovir disoproxil fumarate with the protease inhibitor saquinavir, a P-gp substrate, led to a significant increase in the AUCtau, Cmax, and Ctau of saquinavir by 29%, 22%, and 47%, respectively. Mechanisms behind the increase in saquinavir exposure were believed to be associated with the inhibition of intestinal P-gp by tenofovir disoproxil fumarate [12,32].

In general, since most AVNAs have low to moderate membrane permeability, efflux and uptake transporters have significant and opposite effects on the intestinal absorption of oral AVNAs. BCRP, P-gp, and CNTs have been found to be clinically related to the modulation of intestinal absorption of AVNAs.

5. Impact of transporters on the tissue distribution of AVNAs

Except for some prodrugs with hydrophobic groups, most nucleoside/nucleotide analogs are hydrophilic and have low or negligible plasma binding. The volume of distribution of the approved AVNAs suggests broad tissue distribution of these compounds (Table 2). The blood-to-plasma ratio (B/P) of AVNAs is generally below or equal to 1 (Table 2), indicating that these AVNAs either minimally partition into erythrocytes, or enter erythrocytes but do not bind to erythrocytes proteins and accumulate [33]. Therefore when dried blood sampling can be used as a routine method for concentration determination of these AVNAs, without much concern for erythrocyte accumulation and binding saturation [33]. The most common viral infections are in the respiratory system, liver, and immune systems. The extent of distribution of AVNAs or their active metabolites to their target tissues is extremely important for their therapeutic effects. Additionally, the treatment of viral infection in the brain and other immune privileged compartments is always challenging. Therefore, transporters that play a role in the distribution of AVNAs to the lung, immune system, and immune privileged compartments, including the brain, testis, and eyes, will be discussed in this section. The distribution of AVNAs to the liver will be discussed together with the metabolism of AVNAs in the subsequent section.

5.1. Lung

Lung was one of the tissues with the highest levels of drug transporter expression next to the liver and kidney [7]. Gene expression data has shown that SLC transporters PEPT2, OCT3, and MATE1 are most highly expressed, while some important transporters in the liver and kidney, such as OATs and OATP1B, display much lower expression in the lung [7,26,27]. Among the ABC transporters, P-gp, BCRP, and MRP4 are expressed on the apical side of epithelial cells in the lung [7,26,27].

Lung transporters play an important role in the distribution of drugs from systemic circulation into the pulmonary tissue and epithelial lining fluid, thus affecting their efficacy or toxicity in the lungs. The uptake of ribavirin to the lung tissue was significantly decreased in ENT1 knock-out mice, suggesting that ENT1 was involved in the transport of ribavirin from the systemic circulation to the lung [34]. Remdesivir was approved as an intravenous injection to treat SARS-CoV-2. The unchanged form of remdesivir was low or undetectable in the lung tissues of rhesus macaques [35] and mice [36], while the concentrations of its downstream metabolite GS-441524 were found to be high in the lung of both species. Transporters may be involved in the distribution of remdesivir and its metabolites in the lung tissue. However, the mechanism by which transporters regulation this distribution has not yet been elucidated.

In the case of inhaled drug delivery, lung transporters expressed on the apical side of the epithelium are vital. For example, the inhalation spray of ribavirin is used for the treatment of RSV infection in the lung. In vitro experiments showed that ribavirin was transported across the respiratory mucosa by ENTs, while P-gp was not involved in this process [37]. When developing inhaled drugs, concerns in drug-drug interactions (DDIs) have been addressed on the co-administered corticosteroids, which could be inducers of P-gp [7]. In the inhaled treatment for respiratory diseases, corticoids are often administered together with other therapeutics to treat inflammation and bronchoconstriction [7], potentially influencing the pulmonary disposition of co-administered P-gp substrates.

5.2. Lymphocytes

One of the major groups of AVNAs is the anti-HIV nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NRTI). NRTIs include abacavir, emtricitabine, lamivudine, tenofovir disoproxil fumarate, tenofovir alafenamide, and zidovudine. HIV attacks the human immune system by destroying lymphocytes. Therefore, the distribution and bioactivation of these anti-HIV drugs in lymphocytes are critical for their therapeutic efficacy when used as treatments for HIV infection. Significant expression of many transporters has been reported on lymphocytes or peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs). The gene expression and activity of P-gp, MRP4, and BCRP were detectable in PBMCs [26,27,38], and P-gp, BCRP, and MRPs have also been detected in T cells of gut-associated lymphoid tissue (GALT) [39].

BCRP has been implicated in inducing resistance of human CD4+ T-cell MT-4 cells to zidovudine by fluxing out the parent drug and its active monophosphate metabolite [40]. In a cell-based study, inhibition of MRP4 by non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs such as ibuprofen and indomethacin led to a significant increase in pharmacological activities of several AVNAs, including zidovudine, abacavir, lamivudine, and tenofovir on isolated human peripheral blood lymphocytes [41]. Clinically, P-gp polymorphism (ABCB1 3435C>T, rs1045642) was found to be associated with lower P-gp expression in PBMCs [42]. Six months after the initiation of antiretroviral treatment (composed with abacavir, nelfinavir, and saquinavir or amprenavir), patients with the ABCB1 3435TT genotype had a greater rise in CD4+ cell count than patients with the CT and CC genotype (p=0.0048) [42]. In antiretroviral-naive HIV-infected adults, lamivudine-triphosphate concentrations in PBMCs were elevated 20% in MRP4 T4131G variant carriers who have a deficiency in their MRP4 function (Table 7) [43].

Table 7.

Clinical significance of transporter genetic polymorphism on the pharmacokinetics of antiviral nucleoside analogs

| Drug | Polymorphism | Subjects | Regulated transporters | Pharmacokinetic impact | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tenofovir disoproxil fumarate | ABCC4 (rs3742106) | HIV patients | MRP4 | After adjusting for weight, eGFR, and the concomitant use of ritonavir-boosted protease inhibitors, a 30% increase in the mean tenofovir plasma concentration was observed in patients having the ABCC4 4131 TG or GG genotype. | [92] |

| Tenofovir disoproxil fumarate | ABCC4 (rs1751034) | HIV patients | MRP4 | ABCC4 3463A>G variants had 35% higher TFV-DP intracellular concentrations than wild type (p = 0.04). | [174] |

| Tenofovir disoproxil fumarate | ABCC4 (rs1751034) | HIV patients | MRP4 | ABCC4 3463A>G polymorphism was associated with tenofovir apparent oral clearance (CL/F). Patients carrying ABCC4 3463 AG or GG had a tenofovir CL/F 11% higher than those with genotype AA. | [170] |

| Tenofovir disoproxil fumarate | ABCC4 (rs1751034) ABCC2 (rs717620) |

HIV patients | MRP4, MRP2 | After controlling for race and GFR, ABCC2 –24C>T carriers excreted 19% more tenofovir than wild type (P = 0.04); ABCC4 3463G variant carriers had tenofovir AUC 32% higher than wild type (p = 0.04). | [85] |

| Tenofovir disoproxil fumarate | ABCC2 (rs717620) | HIV patients | MRP2 | ABCC2 –24C>T is associated with decreased eGFR and higher plasma tenofovir concentration (p = 0.018) | [175] |

| Tenofovir disoproxil fumarate | ABCG2 (rs2231142) | HIV patients | BCRP | ABCG2 rs2231142 was associated with tenofovir AUC with rare allele carriers displaying 1.51-fold increase in tenofovir AUC (p < 0.0001). | [176] |

| Tenofovir disoproxil fumarate | ABCB1 (rs3213619) SLC28A1 (rs2242046) |

HIV patients | CNT1, P-gp | The polymorphisms at ABCB1 129T>C (rs3213619) and SLC28A1 1561 G>A (rs2242046) were significantly associated with decreased tenofovir CL/F. Age and creatine clearance are also predictors for tenofovir CL/F. | [93] |

| Tenofovir disoproxil fumarate | SLC28A2 (rs11854484) | HIV patients | CNT2 | SLC28A2 124C>T genotypes were associated with plasma tenofovir exposure (p = 0.05) | [96] |

| Ribavirin | ABCB1 (rs2032582) | HCV patients | P-gp | ABCB1 2677 G > T was statistically associated with ribavirin Ctrough levels after 4 weeks of therapy, while it has not shown any statistically significant association with ribavirin plasma levels or response. | [94] |

| Ribavirin | SLC29A1 (rs760370) | HIV patients with HCV | ENT1 | The polymorphism at the ENT1 gene influences the chance of rapid virological response to pegIFN-ribavirin therapy, modulating intracellular ribavirin exposure within hepatocytes. | [70] |

| Ribavirin | SLC29A1 (rs760370) SLC28A2 (rs11854484) SLC28A3 (rs10868138) |

HCV patients | ENT1, CNT2, CNT3 | SLC28A2 124 TT was related to lower Ctrough levels (TT vs CT/CC, p = 0.048). Patients with SLC28A3 rs10868138 TC (TC vs TT, p = 0.006) and SLC29A1 rs760370 GG (GG vs AG/AA, p = 0.016) genotype had higher ribavirin levels. | [97] |

| Ribavirin | SLC28A2 (rs11854484) | HCV patients | CNT2 | Patients with SLC28A2 124 TT had higher dosage- and body weight-adjusted ribavirin levels than those with genotypes TC or CC (p = 0.02 and p = 0.06 at weeks 4 and 8, respectively). | [31] |

| Efavirenz | ABCB1 (rs1045642) | HIV-infected adults | P-gp | ABCB1 3435C>T was associated with higher efavirenz plasma levels in the standard but not the lower dose group (TC vs CC, p = 0.009). No relationship was found between pharmacogenomics and antiretroviral efficacy. | [95] |

| Lamivudine Zidovudine | ABCC4 (rs3742106) ABCC4 (rs11568695) |

HIV-infected adults | MRP4 | Lamivudine-triphosphate concentrations in PBMCs were elevated by 20% in ABCC4 4131G>T variant carriers (p = 0.004). A trend for elevated zidovudine-triphosphates was observed in MRP4 3724 G>A variant carriers (p = 0.06). | [43] |

5.3. Vaginal and rectal tissues

In addition to the lymphocytes, NRTIs used as pre-exposure prophylaxis require a high local concentration in vaginal and rectal tissue [44]. Drug transporters are one of the major determinants of these tissue concentrations[45]. In the female genital tract, expression of P-gp, BCRP, MRP2, MRP4, MRP5, OCT3, CNT1, ENT1,2 have been found, while OAT1, 3, OATP1B1 are not detectable. In colorectal tissues, P-gp, BCRP, MRP2, 4, 5 are expressed, and OAT1,3, and OATP1B1 are not detectable[45]. A mathematical model analysis study showed that female genital tract concentrations of antiretroviral drugs were associated with substrate probability of efflux transporters, MRP1 and MRP4 [46].

5.4. Brain

Treatment of viral infection in the brain is challenging. ABC transporters expressed at the blood-brain barrier (BBB) and the blood-cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) barrier (BCSFB), including P-gp, MRPs, and BCRP, can significantly limit drug penetration into the brain. In contrast, uptake transporters facilitate hydrophilic nucleoside analogs to cross the BBB and the BCSFB. Both ENTs and CNTs are present in endothelial cells of the BBB and epithelial cells of the BCSFB. Protein expression of some transporters has been quantified in human brain microvascular endothelial cells with the abundance ranked: BCRP > P-gp > ENT1, while the abundance of MRPs, OAT3, OCT1/2, or ENT2 was below the limit of quantification [47]. In addition, CNT2 has been identified at the luminal side of the BBB endothelium and the apical side of the choroid plexus epithelium [48].

A few AVNAs have been shown to have good brain penetration, with concentrations in CSF exceeding their virologic IC50. Zidovudine has shown a high partition coefficient in the brain, with its mean CSF-to-plasma ratio at around 60%, owing to its adequate lipophilicity. Zidovudine is also a substrate for multiple efflux transporters, including P-gp, MRP4, and MRP5 [49], which are believed to restrict the penetration of zidovudine in the brain [49,50]. Abacavir also demonstrated a good CSF-to-plasma ratio of 36% [51], and its brain concentrations were high enough to inhibit the replication of HIV. However, P-gp was found to dominantly limit abacavir’s brain penetration, as demonstrated by a knock-out mouse model [50]. Clinically, in patients with HIV infection, didanosine has been found to be able to reach effective CSF concentrations with a CSF-to-plasma ratio at around 21% after intravenous injection. In situ brain perfusion models also implicated that ENTs are involved in the influx of didanosine to the brain [49,52]. The CSF-to-plasma ratio of emtricitabine varies between two studies. It was reported at 26% in HIV patients received an emtricitabine/tenofovir regimen [53], whereas when the P-gp inhibitor atazanavir was added to the regimen, the CSF-to-plasma ratio of emtricitabine was reported to be as high as 60% [54]. Further clinical studies with a proper control group are needed to confirm this potential DDI.

5.5. Testes

The human blood-testis barrier (BTB) expresses several efflux drug transporters such as P-gp and MRPs [55], providing a sanctuary for HIV during anti-retroviral therapy [56]. AVNAs utilize endogenous nucleoside transporters as means of circumventing the BTB. Expression of nucleoside transporters including ENT1-3 and CNT1-3 was detected in Sertoli cells [57]. ENT1 was located on the basolateral membrane of human Sertoli cells, whereas ENT2 was located on the apical membrane [58]. Several AVNAs have been found capable of accumulating in the semen of treated men. An in vitro study showed that ENT1 was involved in the transepithelial transport of zidovudine, didanosine, and tenofovir disoproxil fumarate across the BTB [58]. Clinically, zidovudine and lamivudine, substrates of ENTs [59], were able to reach greater concentrations in seminal plasma than in blood plasma [60]. AVNAs targeting other viruses were also able to penetrate the BTB. In cynomolgus monkeys, intravenous administration of 10 mg/kg of remdesivir demonstrated that its radio-labeled metabolites distributed to testes and epididymis with similar concentrations as that in plasma [61].

5.6. Eyes

Several approved AVNAs have ophthalmic formulations targeting viral infection in the eyes, including idoxuridine, ganciclovir, and valganciclovir. The blood-retinal barrier (BRB) restricts penetration of drugs into the posterior segment when administered systemically and periocularly [62]. Various transporters have been found in the eye. P-gp, OATPs, MRPs, OCTs, BCRP, ENTs, and CNTs are expressed in both retinal pigment epithelium and inner limiting membrane, controlling drug distribution to different compartments of the eye [63]. However, data on transporter concentrations and distribution to different eye compartments are still lacking.

5.7. Lactating mammary gland

Transporter-mediated processes in the lactating mammary gland may explain the drug accumulation in breast milk. In isolated lactating mammary epithelium cells, transcripts were detected for OCT1,3, MRP1,2,5, MDR1, CNT1,3, ENT1,3, and PEPT1,2, but not for OCT2, OAT1-4, MRP3,4, CNT2, and ENT2 [64]. Higher RNA levels of OCT1, PEPT2, CNT1, 3, and ENT3, and lower RNA levels of MDR1 were found compared to nonlactating epithelium cells [64]. The expression of nucleoside transporter CNT1,3 and ENT 1,3 together with the low protein binding of AVNAs could be responsible for their presence in breast milk with milk-to-plasma ratios at 0.44 [65] and 3.29 [66]. On the other hand, tenofovir show an extremely low milk-to-plasma ratio at 0.07 [66].

In summary, transporters contribute to the selective distribution of drugs to specific tissues. Even for AVNAs with adequate membrane permeability, their penetration to immune privileged compartments is still limited by some efflux transporters such as P-gp and MRPs. In addition, ENTs are considered one of the determinants for tissue distribution of AVNAs due to their ubiquitous expression in diverse tissues [20]. It is also noted that owing to the difficulties in obtaining tissue and CSF samples, there is a lack of clinical evidence for transporter-associated distribution and DDI of AVNAs. Most conclusions are based on in vitro and animal studies. Therefore, the role of transporters in the distribution of AVNAs to those immune privileged compartments, such as the brain, eyes, and testes, has not yet been fully understood.

6. Transporters in the elimination of AVNAs

6.1. Biotransformation of the prodrugs of antiviral nucleoside/nucleotide analogs to their active metabolites

Many AVNAs are designed as prodrugs, including molnupiravir, remdesivir, adefovir dipivoxil, tenofovir disoproxil, tenofovir alafenamide, valacyclovir, valganciclovir, and sofosbuvir. Hydrolysis of these prodrugs to their active parent compounds is usually mediated by esterases such as cathepsin A or carboxylesterase 1 inside target cells or in the intestine, liver, and plasma as summarized in Table 2 [11–13].

6.2. Metabolism of antiviral nucleoside/nucleotide analogs

Unlike other approved drugs, CYP- and UGT-mediated reactions are not the main contributors to eliminating nucleoside/nucleotide analogs (Table 3). Among the 25 approved AVNAs, only 3 drugs (zidovudine, tenofovir alafenamide, and remdesivir) form minor metabolites via CYP-mediated phase I metabolism. Alcohol dehydrogenases and aldehyde dehydrogenases catalyze the phase I metabolism of some AVNAs, including acyclovir, penciclovir, and abacavir. Five AVNAs, namely entecavir, abacavir, emtricitabine, zidovudine, and stavudine, have glucuronidation involved in their elimination pathways. Sulfation is involved in the elimination of entecavir, emtricitabine, and lamivudine. Some nucleoside/nucleotide analogs undergo the same catabolism as natural nucleosides. For example, didanosine, sharing the same pathways responsible for the elimination of endogenous purines, was mainly eliminated via hydrolysis by purine-nucleoside phosphorylase to a single purine base, which was then catabolized hepatically to yield hypoxanthine, xanthine, and uric acid.

6.3. Hepatic transporters related to the elimination of antiviral nucleoside/nucleotide analogs

Hepatocytes express various drug transporters responsible for mediating drug permeability into hepatocytes and eliminating drugs into bile. OATP1B1 and OATP1B3 are two major uptake transporters in the liver [3]. Most approved AVNAs have not been investigated for their transport activity via OATPs, except for tenofovir alafenamide, a prodrug of tenofovir, has been identified as a substrate of both OATP1B1 and OATP1B3 [67]. Uptake of tenofovir alafenamide by hepatic OATP1B1 and OATP1B3 could be one of the routes for its elimination. Alteration of OATP1B1 and 1B3 activity will therefore change the systemic exposure level of tenofovir and potential side effects. Nucleoside transporters may also be crucial in determining the disposition of AVNAs in the liver. In the hepatic tissue, the rank order of transporter mRNA expression was CNT1, ENT1 > ENT2, CNT2. ENTs and CNTs are predominantly localized at the sinusoidal membrane, and a fraction of ENT1, CNT2, and CNT1 also traffic to the canalicular membrane [68]. The clinically estimated liver-to-plasma ratio of ribavirin in humans was approximately 30, reflecting the trapping of ribavirin in hepatocytes [69]. By using the sandwich cultured human hepatocytes model, the effect of transporters on the distribution and metabolism of ribavirin was elucidated. It was shown that the influx of ribavirin into hepatocytes was predominantly mediated by ENT1 [68]. The effect of nucleoside transporters on the pharmacokinetic profile of ribavirin was further confirmed in a clinical trial. It was found in HIV-infected patients with chronic HCV that a gene polymorphism on ENT1 (rs760370) has a significant impact on the therapeutic concentrations of ribavirin within hepatocytes and might further influence the chance of rapid virological response to pegIFN-ribavirin therapy [70] (Table 7).

Few AVNAs are excreted via the bile due to the low molecular weight of most AVNAs. It is generally considered that there is a higher chance for a compound with its molecular weight over 500 to undergo substantial biliary excretion in humans. Biliary excretion of drugs is mainly determined by transport systems localized at the apical membrane of the hepatocyte, such as MRP2, P-gp, and BCRP [71].

6.4. Transporters related to the renal excretion of antiviral nucleoside/nucleotide analogs

Most AVNAs are primarily excreted via kidneys in the unchanged nucleoside form or, in the case of prodrugs, the active parent form. Renal clearance is the primary elimination path for almost all the approved AVNAs, except for zidovudine, didanosine, and molnupiravir. Renal excretion is determined by glomerular filtration, active secretion, and reabsorption. Most AVNAs are water-soluble, with low plasma protein binding and relatively low molecular weight. Thus, they are easily eliminated by renal filtration. Transporter-mediated active secretion of drugs from blood across the basal membrane is not restricted to free drugs and is irrespective of the extent of protein binding [72]. Some AVNAs (such as adefovir, tenofovir, ganciclovir, penciclovir, and zalcitabine) have been found with renal clearance higher than the physiological glomerular filtration rate (Table 2), indicating the involvement of active tubular secretion. Transporters may play a key role in the renal elimination process of these AVNAs.

Many transporters are located on renal tubular epithelial cells and are responsible for the active renal secretion and reabsorption of drugs (Figure 2). Uptake transporters on the basolateral membrane (mainly OCT2 and OAT1/3) work in concert with efflux transporters on the apical membrane to transfer drugs into urine [3]. In the apical side of the renal proximal tubule epithelial cells, various efflux transporters including P-gp, MRP2/4, CNT1/2, and MATE1/2K also play a role in eliminating the nucleoside/nucleotide analogs. Most approved AVNAs have been tested to see if they are substrates of OCT2, OAT1, and OAT3. These transporters are recommended to be evaluated for drugs with significant active renal secretion (active renal secretion is higher than 25% of the systemic clearance), according to the FDA In vitro Drug Interaction Studies Guidance [73]. For some prodrugs, the transport of their active metabolites is also vital for their therapeutic efficacy and toxicity. Probenecid is often used deliberately in clinical trials as a classic inhibitor of OATs, aiming to investigate the roles of OATs in the elimination of the studied drug [4]. In healthy volunteers, coadministration of probenecid with valaciclovir increased systemic exposure of valaciclovir and its active metabolite acyclovir [74] (Table 6). Such results correlated with the in vitro finding that valaciclovir and its hepatic metabolite acyclovir are substrates of OAT1 and OAT3, suggesting that OATs have a clinically significant role in both the hepatic bioactivation as well as renal elimination of valaciclovir [74]. Similar strategies have been applied to reveal that OATs are the major transporters responsible for the active tubular secretion of cidofovir and its nephrotoxicity [75]. Species differences in transporters may also alter the adverse effect of AVNAs. Rat studies on the renal toxicity of the anti-SARS-CoV-2 agent remdesivir demonstrated that its active monophosphate intermediate GS-704277 is an OAT3 substrate and exhibits rat OAT3-dependent toxicity. It was later confirmed that GS-704277 was not a substrate for human OATs, suggesting a reduced potential for renal adverse effects in humans compared with rats due to lower renal accumulation [76].

In summary, for AVNA prodrugs, hydrolysis is their major elimination route; for other AVNAs, renal excretion is the primary route, while hepatic metabolism and bile excretion play a less significant role. P-gp, OCT2, MATE1/2K, MRP4, and OAT1/3, are extensively involved in the active renal secretion of many AVNAs, while OATPs and ENTs in the liver demonstrate significant impacts on the bioactivation and disposition of some AVNAs. It is noted that AVNAs metabolites are also likely to be substrates of the same transporters that transport their parent drugs. Knowing the transporter substrate profile of AVNA metabolites could help comprehensively evaluate the impact of transporters on AVNAs.

7. Clinical significance of the altered transporter activity on the pharmacokinetics of AVNAs

7.1. Altered pharmacokinetics of AVNAs by transporter-mediated drug-drug interaction

In clinical practice, antiviral treatment often requires combinational therapy to avoid potential drug resistance from the virus, suggesting the importance of DDI assessment in patients. Table 6 summarizes clinical reports on transporter-mediated DDIs with pharmacokinetic impacts on AVNAs. Exposure to some AVNAs, such as tenofovir and sofosbuvir, is subject to induction/inhibition of drug transporters and requires special attention. The antiviral protease inhibitors lopinavir, ritonavir, and paritaprevir, all potent blockers of 11 ABC transporters including P-gp and BCRP [77], are the most frequently reported perpetrators for AVNA-related DDIs. One classic example is tenofovir disoproxil fumarate [78–82]. Tenofovir disoproxil fumarate is a substrate of both P-gp and BCRP. After orally administrated, tenofovir disoproxil fumarate is rapidly and completely hydrolyzed to its active form tenofovir. Tenofovir is a substrate of OAT1, OAT3, and MRP4, but not of P-gp, BCRP, nor MRP2. The active tenofovir has been found nephrotoxic, resulting from its kidney intracellular entrapment and subsequent inhibition of the mitochondrial DNA polymerase [83]. Some drugs have been reported to interact with tenofovir disoproxil fumarate during its absorption and with tenofovir during its distribution and elimination. It has been observed in multiple clinical studies that concomitantly administered protease inhibitors (lopinavir, ritonavir, and zidovudine) could decrease the renal clearance of tenofovir, increase its systemic exposure, and increase the risk of nephrotoxicity accordingly [80,84,85]. Supported by in vitro data, the elevated systemic exposure of the nephrotoxic tenofovir by these protease inhibitors is attributed to the reduced tenofovir renal clearance by inhibition of renal OAT3 and MRP4 [86], as well as the reduced intestinal efflux of tenofovir disoproxil fumarate via inhibition of P-gp and BCRP [87]. Similarly, the aggravated nephrotoxicity of tenofovir by other co-administered MRP4 inhibitors such as diclofenac has also been reported [88]. Tenofovir alafenamide fumarate, which is designed to be selectively hydrolyzed by the HIV-infected T cells, has been developed to reduce the dose of tenofovir required for effective treatment and to improve the safety of tenofovir [79]. In addition to DDI, some substrates of nucleoside transporters are subject to food-drug interaction. Ribavirin, a CNT2 substrate, demonstrated a decreased plasma exposure when co-administered with high purine meals due to the CNT2 inhibition in the intestine by the high concentration of purine. It is worth noting that although all summarized clinical DDIs demonstrate significant changes in pharmacokinetic parameters, many of them result in less than two-fold AUC changes, indicating weak DDIs. For these weak DDIs, dose recommendations in their drug labels are often not required, except for drugs with narrow therapeutic indices [89].

7.2. Altered pharmacokinetics of AVNAs by genetic polymorphism of transporters

Genetic polymorphisms could affect the expression and the activity of transporters. This is another critical factor that has been widely reported to be associated with clinically significant pharmacokinetic changes of AVNAs. Advances in genomic technologies have led to a wealth of information on transporter genetic polymorphisms and how these polymorphisms affect drug disposition. Variants of common drug transporters in SLC and ABC families have been extensively investigated and reviewed previously [90]. In Table 7, we summarized the reported transporter polymorphism-related clinical pharmacokinetic alterations of approved AVNAs. Clinical studies that fulfilled two criteria were selected: 1) identified significant associations between the transporter polymorphisms and the drug disposition, and 2) confirmed substrates of the transporters in vitro.

Polymorphisms of MRP2/4, P-gp, and CNT2 are involved in most clinical pharmacokinetic alterations of AVNAs. Similar to DDIs, tenofovir disoproxil fumarate is the most affected AVNA by transporter polymorphism. Confirmed by multiple studies, polymorphism of MRP4 or MRP2 is associated with altered plasma tenofovir concentrations [85] and nephrotoxicity of tenofovir [91,92]. BCRP rs2231142, a transporter polymorphism with high frequency[90] has been found to be related to the altered pharmacokinetics of tenofovir disoproxil fumarate. Polymorphisms of P-gp, namely ABCB1 129T>C (rs3213619), 2677 G>T (rs2032582), and 3435C>T (rs1045642), are associated with the pharmacokinetic changes of tenofovir [93], ribavirin [94], and efavirenz [95], respectively. The CNT2 variant (SLC28A2 124C>T, rs11854484) has been associated with increased tenofovir and ribavirin plasma exposure [31,96,97]. It is noted that some clinical studies may provide results with discrepancies due to the low allele frequencies of some transporter polymorphisms. To enhance the reproducibility of results and explore the effects of these less common variants, analysis on multiple studies and samples pooling might be needed to obtain larger sample sizes in the data analysis.

7.3. Altered pharmacokinetic of AVNAs by diseases-related dysregulation of transporters

Renal impairment affects the filtration rate as well as transporter activity and is a significant factor impacting the pharmacokinetics of AVNAs. Many AVNAs require dose adjustment in renal impairment patients [98], and some are not recommended to be used in patients with severe renal impairment (GFR <30 mL/min/1.73m2), such as sofosbuvir [99]. On the other hand, since hepatic clearance is not the primary elimination route for AVNAs, dose adjustment for hepatic impairment is not required for most AVNAs.

Changes in transporter expression levels in various acute disease states have been reported and reviewed [100]. Inflammation and increased levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines, which could cause transporter dysregulation, are found in numerous chronic illnesses. Inflammation-induced downregulation of P-gp, MRP2, and BCRP has been reported for the liver and intestine. Clinically, protein expression of P-gp and MRP2 was decreased by 2.5 to 3.3-fold in colon tissues of HIV-infected patients compared to uninfected controls [101]. Similarly, HCV-infected patients have lower expression of P-gp, BCRP, and MRPs in their liver tissues [102,103]. Inflammatory bowel disease leads to a marked decrease of P-gp and BCRP [104] and an increase of OATP2B1, ENT1, ENT2, CNT2, and PEPT1 in the intestine [105]. In addition, due to the inhibitory effect of high concentration of adenosine, inflammation-related fluctuation of plasma adenosine level (10- to 20-fold higher than the normal concentration of 0.4 – 0.8 μM) [106] may also alter the cross-membrane transport for substrates of ENTs and CNTs. Hypoxia and inflammation could lead to a decreased expression of ENT1 and ENT2 [107–109]. Ischemic kidney injury not only leads to a rapid decline in glomerular filtration rate but also results in reduced protein expression of transporters such as OAT1/3 in kidneys. In the brain, stroke upregulates P-gp in the BBB [100], while neurodegenerative diseases (Alzheimer’s disease and Parkinson’s disease) downregulate P-gp [110]. Despite the comprehensive information on disease-related transporter dysregulation, how this dysregulation alters the pharmacokinetics of specific AVNAs has not yet been studied. Clinical studies and modeling works would be valuable to evaluate the impact of disease-associated changes in drug transporters on the efficacy and toxicity of AVNAs.

7.4. Altered pharmacokinetic of antiviral nucleoside/nucleotide analogs by age- and pregnancy-related transporter changes

Both age and pregnancy involve marked physiological changes in gastric emptying time, tissue composition, blood flow rate, plasma volumes, glomerular filtration rate, etc [111,112]. All have significant impacts on the pharmacokinetics of drugs. In clinical studies, age and pregnancy are confounding factors in predicting the pharmacokinetics of AVNAs, such as tenofovir [93,113]. In addition to these physiological changes, altered transporter function in aging and pregnancy might also play a role. Minimal data are available on the effect of age on transporter expression. The hepatic expression of MRP2, OATP1B1, and OATP1B3 in all pediatric age groups was significantly lower than in adults [114]. Decreased BCRP liver expression has been shown upon aging [115]. The gene expression levels of OCT2 in the kidney were found to be significantly lower in females ≥50 years [116]. In BBB, P-gp function decreases in specific brain regions with aging [117]. A large number of drug transporters are expressed on the placenta, and the expression of these transporters could be gestational age dependent. For example, P-gp expression on the human placenta was about 45-fold higher in early pregnancy as compared to in full-term; whereas BCRP expression is not gestational age dependent [111,118]. Pregnancy also alters transporter expression and functions in other organs. There is an apparent increase in renal drug transporter activity (including P-gp, OCT2, and OAT1) during pregnancy [111].

7.5. Pharmacokinetic models for analyzing factors involved in transporter-related pharmacokinetic changes of AVNAs

Most retrospective clinical data analysis of transporter-related pharmacokinetic AVNA changes evaluated the effect of altered transporter function in isolation, lacking information on the potential effect of multiple covariates such as demographic factors (age, ethnicity), coexisting diseases, multiple genetic polymorphisms in the same subject, etc. In some cases, transporter-mediated DDIs could only be observed in specific populations carrying genetic variants [90]. Clinical trials specifically designed with all the factors considered are limited. Thus, pharmacokinetic models have been applied to some of the AVNAs to identify all covariates and confounders. This can be useful in predicting and guiding dose adaptations.

Population pharmacokinetic modeling and physiologically-based pharmacokinetic (PBPK) modeling are both well-established and useful techniques for investigating multiple factors involved in altered AVNA pharmacokinetics. Population pharmacokinetic modeling evaluates population data using a nonlinear mixed-effects model, taking intra- and inter-individual variability and covariates into consideration [119], enabling the efficient analysis of various covariates using pooled pharmacokinetic data from multiple clinical trials [119,120]. For example, a population pharmacokinetic model characterized the plasma and PMBC concentrations of ribavirin and identified the concomitant telaprevir use, inosine triphosphatase genetics, creatinine clearance, body weight, and gender as significant covariates [121]. Population models were also applied to provide pharmacokinetic simulation and dose adjustment recommendations of lamivudine for specific patient populations including children and infants for anti-HIV therapy [122]. Population models are empirical, non-physiological, and less flexible; while PBPK models are mechanistic and more flexible to be scaled to specific populations and linked to any other co-administered drugs for DDI models. PBPK models are most widely used for the prediction of potential DDIs for AVNAs. For example, using estimated relative activity factors for OAT1/2/3, the renal clearance of 31 drugs, including five AVNAs, has been predicted by a PBPK model based on in vitro data. The model was further applied to quantitatively predict renal DDIs of the substrate drugs with probenecid [123]. Recently, a PBPK model was applied to evaluate the potential DDIs of remdesivir based on its in vitro activity on drug-metabolizing enzymes and transporters. The simulation provided strong evidence that remdesivir at therapeutic doses has a low potential for DDIs in patients infected with COVID-19 [124].

In summary, co-administered inhibitors and genetic polymorphisms of transporters are the two most frequently reported factors that impact the clinical pharmacokinetics of AVNAs. In addition, age, pregnancy, and disease status have all been reported to alter transporter activity in humans. However, there is still a lack of clinical evidence demonstrating that physiopathological conditions related to alterations of transporter activity can lead to pharmacokinetic changes of AVNAs. Pharmacokinetic models can be useful tools for determining potential impacts from physiological/pathological changes on transporter-related pharmacokinetic changes of AVNAs.

8. Conclusions

The current review elucidates the roles of key transporters in the absorption, distribution, and elimination of approved AVNAs. Together with P-gp, MRP4, and BCRP, nucleoside transporters have shown extensive impacts in the disposition of the approved AVNAs. Therefore, it is highly recommended to investigate the involvement of these transporters during the drug development of novel AVNAs. Although the roles of transporters in intestinal absorption and renal excretion of AVNAs have been well identified, more research is warranted to understand their roles in the distribution of AVNAs, especially to immune privileged compartments where treatment of viral infection is challenging. Clinically, co-administered inhibitors and genetic polymorphisms of transporters are the two most frequently reported factors that alter pharmacokinetics of AVNAs. Disease, age, and pregnancy conditions may also regulate transporter activities, though their specific effects on the pharmacokinetics of AVNAs remain largely unknown and need to be further explored. The application of pharmacokinetic modeling may help to elucidate these complex factors in clinical settings.

9. Expert opinion