Abstract

The promotion of comfort and quality of life of people with cancer in palliative care requires flawless evaluation and management of pain, understood in its multidimensionality and integrality. The objective of this study was to present an overview of the scientific production referring to evaluation of the pain and total pain of patients with advanced cancer in palliative care. The study involved an integrative literature review, searching the databases PubMed, Embase, Cinahl, Lilacs and Web of Science using the descriptors ‘Total Pain’, ‘Cancer Pain’, ‘Pain’, ‘Symptom Assessment’, ‘Pain Measurement’, ‘Pain Evaluation’, ‘Neoplasms’, ‘Cancer’, ‘Tumor’, ‘Palliative Care’, ‘Hospice Care’, and ‘Terminal Care’. To select the studies, the authors used the reference manager Mendeley and the application Rayyan™, as well as blind and independent peer review. Twenty-two articles were selected, published between 2002 and 2020 in different countries, and classified into two thematic units: ‘Physical, social, emotional, and spiritual factors related to pain in cancer’ (N = 13) and ‘Importance of the overall evaluation and multidisciplinary team in the management of pain’ (N = 9). Advanced cancer is associated with high mortality, a decline in health status, the presence of pain, and complex psychosocial concerns. Pain and symptoms in patients in palliative care should be evaluated as a whole and controlled thorough the work of an interdisciplinary team. The qualitative synthesis of the results demonstrates that most of the evaluated studies have a mixed nature; there are significant methodological differences among them and a low level of evidence in studies relating to the subject of pain evaluation in palliative care.

Keywords: cancer, integrative review, palliative care, total pain

Background

Cancer is often diagnosed at an advanced stage of evolution, causing people to require a highly complex approach with qualified and specialized care as they have a high prevalence of pain and symptoms that are difficult to control, such as fatigue, dyspnea, anxiety, and depression.1,2

According to the International Association for the Study of Pain, pain is ‘an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with actual or potential tissue damage’. 3 It is a personal experience influenced by the biological, psychological, and social factors of the sick person and by their life experiences.

Pain associated with advanced oncologic disease occurs in 70–90% of cases, at several stages of the disease. It is one of the most frequent reasons for a patient’s disability and distress. It leads to a loss of quality of life and a perspective of finitude, requiring an interdisciplinary approach with qualified and specialized care.4–6

When it is not alleviated, pain can generate physical, emotional, social, and spiritual symptoms; harm cognitive functions, activities of daily living and sleep; and cause overall distress, defined by Cicely Saunders as ‘total pain’, which is the central theme of the literature review below.7,8

Methods

This is an integrative literature review that synthesizes results of studies on pain related to cancer, using primary methods of experimental and non-experimental research. 9

The review was based on the steps and processes reported by the PRISMA standards for systematic reviews. 10 The authors followed these steps: selection of the guiding question; definition of eligibility criteria; definition of relevant information from the studies; evaluation of findings; interpretation; and synthesis of the information found. 11

The Patient, Intervention, Context (PICo) research strategy was used to guide the development of the investigation question and definition of criteria of inclusion and exclusion, 12 with the following guiding question: ‘What is the evidence available in the literature that addresses the evaluation of pain/total pain and the symptoms of patients with advanced cancer and/or in palliative treatment?’

The collection of material was performed through consultations on the electronic databases PubMed, Embase, Cinahl, Lilacs, and Web of Science. The electronic search strategy used a combination of search terms involving the descriptors or keywords ‘Total Pain’, ‘Cancer Pain’, ‘Pain’, ‘Symptom Assessment’, ‘Pain Measurement’, ‘Pain Evaluation’, ‘Neoplasms’, ‘Cancer’, ‘Tumor’, ‘Palliative Care’, ‘Hospice Care’, and ‘Terminal Care’, which were combined through Boolean connectors ‘OR’ and ‘AND’.

The previously defined inclusion criteria were primary studies indexed in the databases, conducted with human beings aged 18 or older, whose main proposal was the assessment and management of pain or total pain and the symptoms of cancer patients. The authors excluded studies relating to surgical procedures and/or pharmacological treatments (even with a palliative intent), studies of secondary source, theses, letters, and editorials.

The reference manager Mendeley was used to organize the imported studies and to exclude duplicates, and the application Rayyan™ – software developed by the Qatar Computing Research Institute – was employed for the careful selection and inclusion of studies in the final sample. 13 Two reviewers participated in the selection process of the sample in an independent and blind way, and performed the initial screening of articles using the title and abstract. All potentially relevant studies were read in full and evaluated independently by a third reviewer, and divergences were solved through discussion and consensus among evaluators.

Next, the authors proceeded with the extraction and synthesis of data from the selected articles using an instrument of evaluation, 11 covering the following domains: title; authors’ names; year of publication; the publishing journal and its impact factor; the objective of the study; the methodological procedure; the main outcomes; and the level of evidence.

For the methodological evaluation, a hierarchical classification of levels of evidence was used. 14 According to this classification, Levels I and II indicated strong evidence (Level I was composed of systematic reviews or meta-analysis of relevant controlled randomized clinical trials, and Level II was composed of well-designed controlled randomized clinical trials); Levels III–V indicated moderate evidence (Level III was composed of clinical trials with no randomization, Level IV was composed of cohort or case-control studies, and Level V involved systematic reviews of qualitative descriptive studies); and Levels VI and VII indicated insufficient evidence (Level VI was composed of qualitative or descriptive studies and Level VII was composed of authorities’ opinions and/or reports of specialist committees).

A qualitative synthesis of the data was performed (as shown below), which demonstrated that most of the evaluated studies had a mixed nature and that there were significant methodological differences between them.

Results

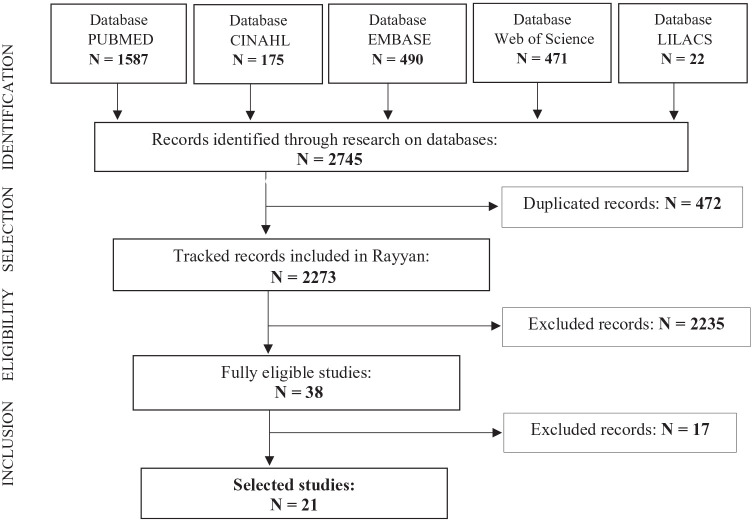

We identified 2745 articles through consultation of the five electronic databases mentioned above, of which 472 were excluded because of duplicates, 2235 were excluded for not meeting pre-established inclusion criteria, and another 16 studies were excluded after full reading. Therefore, 21 articles were included in the final sample of this review, as demonstrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Search mechanism of the integrative review, from PRISMA FlowDiagram 15 (Brazil, 2021).

As a result of the process of content analysis, the 21 selected studies were categorized into two thematic units (Tables 1 and 2):

Table 1.

Synthesis of articles of unit 1: the multidimensionality of pain in cancer (N = 13).

| Author/journal | Place/ year |

Method | Main outcomes | IF | LE | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thematic unit 1 (N = 13) | Mystakidou et al.

16

Archives of Psychiatric Nursing |

Greece 2007 |

Cross-sectional study | The intensity of pain significantly interferes in the general activity, humor, work, and life enjoyment. Significant associations were found between the interference of pain in “humor” and “life enjoyment” and hopelessness, as well as between pain with depression and cognitive state | 0.495 | VI |

| Hackett et al.

17

Palliative Medicine |

United Kingdom 2016 |

Qualitative study | Pain was classified as dynamic. According to patients and caregivers, the relief and treatment of pain are not assured once and for all. The main motivators for looking for help and actions of patients to control pain were the sensory experiences and the meaning associated with pain, not related to the beliefs about analgesia | 1.657 | VI | |

| O’Connor et al.

18

Journal of Pain and Symptom Management |

United Kingdom 2012 |

Secondary analysis of clinical data | Pain is strongly associated with emotional distress and this association is independent of gender, primary diagnosis of cancer, and the presence of active disease. Causal relationships between pain and emotional distress are complex and support the hypothesis that pain can increase anguish and anguish can also increase pain | 1.316 | VI | |

| Pathmawathi et al.

19

Pain Management Nursing |

Malaysia 2015 |

Qualitative study | Participants understood pain as an unbearable experience that caused suffering in their lives. They saw their experience of pain as an indicator of disease progression, and such occurrences of pain may be an indicator of propagation of the disease | 0.447 | VI | |

| Arnold

20

BMC Palliative Care |

Canada 2011 |

Cross-sectional study of mixed methods | Patients’ perceptions of end-of-life needs are multidimensional, often ambiguous and uncertain. Communication is fundamental to provide ideal palliative care. | 1.056 | VI | |

| Black et al.

21

Pain Medicine |

USA 2011 |

Correlational descriptive study | Older cancer patients experience pain and not painful symptoms that can affect and confound the treatment of other symptoms and interfere in patient’s general quality of life. Palliative care may have a positive impact on the severity of pain and related suffering, as well as in patients’ quality of life as they get closer to death | 0.911 | VI | |

| Tishelman et al.

22

Journal of Clinical Oncology |

Sweden 2007 |

Cross-sectional study | High prevalence of symptoms was found in all the subgroups, with higher intensity in the subgroups closer to death, indicating the need for prophylactic and proactive treatment of symptoms | 44.544 | VI | |

| Gryschek et al.

23

Psychology, Health & Medicine |

Brazil 2020 |

Cross-sectional study | A significant relationship between psychological pain and the mechanisms of negative spiritual coping was identified. Depression and anxiety symptoms were significantly associated and religious/spiritual coping was associated with depressive symptoms | 0.663 | VI | |

| Rawdin et al.

24

Journal of Palliative Medicine |

USA 2013 |

Cross-sectional study | Findings suggest that hope is more closely related to the psychosocial elements of the experience of pain than to its intensity. Depressive symptoms and spiritual well-being interfered in the experience of pain of patients, influencing their beliefs, attitudes, and interpretations of pain | 0.929 | VI | |

| Koyama et al.

25

BioPsychoSocial Medicine |

Japan 2016 |

Retrospective study | Female patients were more likely to suffer from psychosocial problems, such as changes in appearance, family problems and sexuality issues, whereas male patients were more likely to have spiritual pain | 0.318 | IV | |

| Malhotra et al.

26

Support Care Cancer |

Singapore 2019 |

Cohort study | Financial difficulties were associated with worse physical, psychological, social and spiritual results and less quality of the coordination and capacity of response to health care, less meaning and less peace, and low levels of hope. Patients with financial difficulties may benefit from interventions to promote their spiritual well-being with a patient-centered holistic approach at end of life | 1.062 | IV | |

| Meeker et al.

27

Journal of Oncology Practice |

USA 2016 |

Cross-sectional study | Significant levels of emotional and financial distress and general suffering were identified. These factors were interrelated with financial and emotional stress, contributing to general suffering | 1.392 | VI | |

| Muñoz et al.

28

Revista El Dolor |

Chile 2010 |

Cross-sectional study | The evaluation and management of total pain, when reached, improve the quality of life and psychological well-being of the cancer patient and their family and other meaningful people | 0.139 | VI |

IF, impact factor; LE, level of evidence.

Table 2.

Synthesis of articles of unit 2: overall evaluation and management of pain by the multidisciplinary team (N = 8).

| Author/journal | Place/year | Method | Main outcomes | IF | LE | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thematic unit 2 (N = 8) | Pidgeon et al.

29

BMJ Supportive & Palliative Care |

Australia 2016 |

Cross-sectional study | Patients have physical and psychosocial worries, often complex and classified as ‘severe’. They frequently experience high levels of pain, as well as other symptoms and psychosocial concerns. Participants in palliative care services reported higher levels of depressive feelings, family anxiety, and worries about practical issues than participants in community contexts | 0.853 | VI |

| Lin et al.

30

Asia-Pacific Journal of Clinical Oncology |

Taiwan 2018 |

Cross-sectional study | The undertreatment of pain is highly prevalent and negatively affects patients’ physical and psychological functioning. The strategies to overcome barriers to the effective control of pain should be optimized to better alleviate pain of cancer patients | 0.611 | VI | |

| Didwaniya et al.

31

Palliative and Supportive Care |

USA 2015 |

Case study | The reported case highlights the importance of timely multidisciplinary intervention and the use of the acute palliative care unit, which resulted in the appropriate control of pain after several medical and invasive procedures that caused toxicities | 1.968 | VI | |

| Erol et al.

32

European Journal of Oncology Nursing |

Turkey 2018 |

Qualitative descriptive study | Patients with advanced cancer who had pain experienced anxiety, helplessness, hopelessness, and many restrictions in their daily life, as well as incapacity to control pain. Most patients are not satisfied with nursing care in terms of pain management | 0.753 | VI | |

| Mori et al.

33

Journal of Palliative Medicine |

USA 2012 |

Study of three clinical cases | The cases demonstrate the complexity of the management of pain in cancer and report that the multidisciplinary approach can effectively alleviate severe pain, providing multimodal treatment, detecting and generating treatment side effects, and addressing underlying psychosocial distress and chemical coping | 0.929 | VI | |

| Reddy et al.

34

Journal of Pain and Symptom Management |

USA 2012 |

Case study | Psychological factors, delirium, and family suffering may contribute to the increase of pain. A full interdisciplinary approach to address total pain in patients with advanced cancer may relieve the need for invasive interventions and facilitate a safe discharge into the community | 1.316 | VI | |

| Satija et al.

35

Indian Journal of Palliative Care |

India 2014 |

Case study | The case reflects that good communication of professionals with the patient and caregivers helps them accept their life situation more easily and reduces the psychological load of pain. The team addressed spiritual concerns as part of routine care. The patient was able to accept his situation better, his anger decreased, and he was ready to resume treatment | 0.327 | VI | |

| Butler et al.

36

Psychosomatic Medicine |

USA 2003 |

Randomized study | Specialized clinical interventions are particularly necessary for cancer patients as they get closer to death. Intervention studies with patients with advanced disease showed psychological distress and pain when death was close in the evaluation of psychological results | 1.731 | VI |

IF, impact factor; LE, level of evidence.

Unit 1: The multidimensionality of pain in cancer (N = 13)

Unit 2: Overall evaluation and management of pain by the multidisciplinary team (N = 8)

Unit 1: the multidimensionality of pain in cancer (N = 13)

Advanced stage cancer is associated with a decline in the person’s health status. It may cause pain of varying nature, degree, and intensity, in addition to complex physical and psychosocial concerns, which should be comprehensively evaluated. Psychological distress, when not properly identified and treated, may lead to severe consequences, such as depression, hopelessness, and a decrease in cognitive function.

The coexistence of physical, psychological, and cognitive problems faced by oncologic patients with pain must be globally assessed and may require therapeutic interventions for mood disorders, cognitive difficulties, and pain. This evaluation engages professionals in the search of an optimized way of looking at the complexity of pain through specific combinations of pharmacological options and other therapeutic options.16,17

Distinct patterns of pain can be observed in the reports of interviewed patients in terms of complexity, severity, transience, and degree of control noticed about pain, emphasizing that the experience of pain is not static but dynamic, and related to the progression of disease, to the impact of treatments to prolong life and to the beliefs and previous experiences of patients and their caregivers. 17

The prevalence of pain may be strongly and independently associated with emotional distress, becoming a complex experience and difficult to control. Pain is seen by patients as unbearable and a cause of suffering in their lives because it makes them sadder and more desperate, causing distress, anguish, and concern.18,19

Although the control of symptoms is a common focus of palliative care in most settings, mental health has only recently gained the same importance. Since every person has their own way of getting back to normal life or coming closer to death, their problems and anxieties, feelings, and desires require a unified and unique intervention aimed at relieving the suffering of both patients with active cancer and cancer survivors.16,18 Being able to identify the occurrence and prevalence of end-of-life needs based on the patient is key to offering ideal palliative care.

Pain and symptoms may confound treatment and interfere with a patient’s general quality of life and their emotional, spiritual, and social issues.20–22 There is a relationship between psychological pain and the mechanisms of spiritual coping. A study has shown that hope is more closely related to the psychosocial elements of the experience of pain than to the intensity of pain. Patients may keep a sensation of hope even when pain and other symptoms of cancer progress according to their affective-cognitive, psychosocial, and spiritual resources and their resilience.23,24

The needs and social relationships are more important for patients than physiological needs, which supports the ‘feeling of belonging’ as a primary human need, the importance of which might increase closer to death. 20 In terms of social distress, a study carried out in Japan showed that there were differences between men and women; while women were more likely to suffer from psychosocial issues, such as changes in appearance, family problems, and sexual matters, men presented greater spiritual pain as a feeling of uselessness, loneliness, and hopelessness. 25

Social pain is often related to practical issues of everyday life. Financial difficulties relating to social issues are mainly identified in studies performed in countries where there are difficulties in accessing free public healthcare. They are associated with worse physical, psychological, social, and spiritual results and less quality of coordination and capacity of response to healthcare (that is to say, greater pain and total suffering), as well as less meaning, less peace, and lower levels of hope. Interventions to relieve financial problems can help reduce the levels of the general problems of patients.26,27

One of the reasons why the pain of cancer patients is not well controlled may be the fact that physicians are not aware of their patients’ pain. Many medical oncologists do not ask their patients routinely about pain, and the evaluation of pain is rarely mentioned in medical records. 18 Patients use their own vocabulary to communicate their needs at end of life; however, there are few scripts for family conversations that allow people with terminal diseases to express clearly what they are experiencing and what their needs or worries are, limiting the delivery of ideal palliative care. 20

Therefore, the findings of this review validate the importance of palliative care in the management of patients’ pain, distress, and quality of life. Human suffering because of pain and advanced oncologic disease are characterized by separation distress, fatigue, sadness, fear of suffering, feelings of uselessness, fear of pain, and insomnia. 28

The studies of this unit restate the importance of a global view of pain and symptoms, totally validating the distress of patients in physical, spiritual, social, and emotional dimensions, with the need for individualized and humanized care provided by a team trained to deal with the total pain of oncologic patients.

Unit 2: overall evaluation and management of pain by the multidisciplinary team (N = 8)

To alleviate the pain, it must be well evaluated. Pain in cancer is subjective; it can be acute or chronic and, when it persists, it may indicate disease progression. Unassessed pain cannot be treated. Given the difficulties in understanding and describing it and its subjectivity, it is often underdiagnosed and undertreated, contributing to the loss of quality of life of the affected person.

Pain and symptoms must be evaluated according to the characteristics of each patient, and such information must be recorded and available to all team members. Healthcare providers must be alert to patients’ symptoms and pain, taking a holistic view that goes beyond drug treatment. 29

Evaluating pain is a difficult task that is often not performed because of lack of knowledge by the team or because of its complexity. Inappropriate evaluation and insufficient knowledge among physicians of the management of pain and the prescription of opiates have been major barriers to the effective treatment of pain in cancer. Recognizing this difficulty and conducting a comprehensive and multidimensional evaluation by the interdisciplinary team may contribute to optimize the management of pain and relieve the pain of cancer patients.30,31

Some studies analyzed in this review used multidimensional instruments aiming at a more complete evaluation, for example, the Brief Pain Inventory, the Palliative Outcome Scale (POS2), and the Edmonton Symptom Assessment System (ESAS), together with semi-structured interviews and unidimensional instruments, such as the Visual Analog Scale (VAS). Despite the low level of evidence of these qualitative studies (such as those involving case reports), they have been included in this review because they revealed important aspects for reflection about patients’ total pain.

The awareness that the expression of pain in cancer may affect other dimensions (including emotional, cognitive and social dimensions) reveals new possibilities of management to professionals, preventing unnecessary procedures and promoting a more careful screening for treatment.30–32

A multiprofessional team is necessary for the management of pain. A multidisciplinary approach can alleviate severe pain effectively, providing multimodal treatment, detecting and managing the side effects of treatment, and addressing underlying psychosocial distress.

Three case studies of patients with cancer presenting pain and distress, and who were treated with multidisciplinary approach, were reported by Mori et al. 33 In all three cases, support counseling was offered by the members of the palliative care team with the aim of allowing patients and their families to express their emotional distress in order to reduce the expression of symptoms and to help them differentiate their experiences from pain and suffering. Another case study reported that a patient with complex oncologic pain, refractory to therapy with oral and intrathecal opioids, got better after the interdisciplinary intervention of palliative care. 34 His daily equivalent dose of morphine decreased by 94% over a period of 10 days, and he had better control of pain and function. These authors highlight the importance of addressing and treating psychosocial distress that contributes to the expression of total pain.

As seen before, psychological and social factors and family suffering may contribute to the increase of pain. A patient’s personal beliefs in relation to analgesics may also influence the management of pain, particularly when it comes to adherence to medication. Lin et al. 30 showed that approximately two-thirds of patients expressed apprehension about treatment with opioids, including the fear of dependence and side effects.

Ineffective communication between physician and patient may be a barrier to effective pain management and may lead to a patient’s low satisfaction, causing feelings of anxiety, frustration, helplessness, and anger. Collaborative communication, however, and information sharing and regular screening of a patient’s psychosocial and spiritual needs provided by the multidisciplinary team can help patients and their family increase satisfaction and efficacy in the control of pain.30,31,35

Advanced cancer patients are polysymptomatic and need a specialized team and a holistic approach to help them with the complex load of symptoms. Specific clinical interventions for patients with cancer at the end-of-life stage are needed as they come closer to death. In addition to complementary and integrative interventions that can be experimented with as effective tools in patients suffering a lot from their symptoms, it is possible to offer benefits without presenting any conceivable damage.31,36

Discussion

The present review had as its central theme the need to present an overview of scientific production referring to the evaluation of total pain in cancer, the data of which have been synthesized in Tables 1 and 2.

In terms of the study characteristics, seven were published in journals in the field of palliative care, five in the field of pain and symptoms, four in the field of oncology, three in the multidisciplinary field, and two in the field of nursing. Regarding where they were published, seven were published in the United States, one in Canada, two in the United Kingdom, one in Australia, one in Brazil, one in Chile, one in Greece, one in India, one in Japan, one in Malaysia, one in Singapore, one in Sweden, one in Taiwan, and one in Turkey. The period of publication of the selected articles comprised the years 2002–2020.

In relation to methodological designs, there were 11 observational studies (eight cross-sectional, two retrospective, and one cohort); nine descriptive studies (four case studies, two qualitative, two descriptive, and one multicentric); and one study of mixed methods.

The levels of evidence of the selected studies varied between Level IV and Level VI, classified as moderate and insufficient according to Melnyk and Fineout-Overholt, 14 and the mean of the impact factors of the journals where the studies were published was 3.019. This information demonstrates the need for studies based on more stringent methods.

In summary, the included research studies showed methodological limitations, such as a small casuistic, lack of blinding and randomization. The studies did not offer research questions that justified or guided the methodology and provided few explanations of the processes and steps they followed to ensure results were reliable.

The main outcomes of this review evidenced the scarcity of research on the theme of total pain and reinforced the importance of evaluating pain in a global way from a perspective of integrality, together with an interdisciplinary team, especially in patients in oncologic palliative care. They indicated the importance of looking at the multidimensionality of pain and signaled the need to expand interventions to other patients with interventions based on the concept of total pain. They also pointed to the need for the development of further research with more methodological rigor on the care of oncologic patients in palliative care.

The contents suggested that the process of illness in general comes with pain, whether physical, emotional, social, or spiritual. The intensity of this pain varies from person to person and depends on several factors: sex, age, ethnicity, culture, and social support, and not only on the type of nociceptive stimulus. The painful experience is individual and unique for the person who feels it and is intrinsically related to conceptions of pain and its management acquired through past experience in society and modified by the previous knowledge of existing or presumed damage.3,37

The pain of people with cancer may have numerous causes relating to primary tumors, metastasis, treatment, or even concomitant disorders. 38 The pain of people with cancer has multiple dimensions. In addition to physical distress, psychological, social, and spiritual factors and family suffering may be related to the increase of pain, such as anguish and the uncertainty of a cure; the fear of treatment, hospitalization, or death; and difficulties bonding with the health team. 30 All these things affect quality of life and social interactions.

In this regard, to be effectively controlled, pain must be understood in all its complexity and multidimensionality, recognizing that the physical, emotional, social, and spiritual components are mutually affected and cause a significant impact on all domains of an individual’s life.

This multidimensionality shapes the concept of ‘total pain’ proposed by Cicely Saunders in 1964, which is connected to the narrative and biography of every person and presupposes the need to listen to their history and understand their experience in a subjective and multifaceted way.39,40

Being able to understand and evaluate the total pain of a patient with a chronic disease is of paramount importance as part of the plan of care of a patient in palliative care. Over the last decades, knowledge, concepts, and therapeutic interventions for the management of the pain in oncologic patients have evolved considerably. However, according to the International Society of Nurses Care (ISNCC), 41 oncologic pain continues to be a prevailing symptom experienced by patients; once, in accordance with the estimation of WHO, of the five million people who die from cancer every year, four million people die with not controlled pain. Although approximately 90% of cases of pain in the oncologic patient can be effectively controlled, doing so still represents a challenge to health professionals, making this suffering unnecessary. 42

Understanding, evaluating, and recognizing the ‘total pain’ of patients with a chronic disease is fundamental. Drug options are hardly effective to relieve pain if they are used in an isolated way; thus, it is necessary to unite pharmacological and non-pharmacological intervention, aiming at associations and full care for the multiple dimensions of pain. ‘The physical pain is never alone: with it, the reminiscences of other pains experienced by the individual become present’. 43

The studies included in this review evidenced the importance of the effective participation of a multiprofessional team for the control of pain of people with cancer. Understanding their health status, a good relationship with professionals and recognition of their suffering significantly improve the symptoms and distress experienced by them.

Various multidimensional instruments for evaluating quality of life include questions for the evaluation of physical, emotional, spiritual, and social dimensions, but are not specific for the evaluation of pain. The implementation of an instrument for multidimensional pain assessment can be one way to sensitize the professionals who provide care, demanding knowledge, sensitivity, willpower, and dedication, since it produces changes in the attitude and behavior of the multiprofessional team. 44 There are pain-specific unidimensional assessments, but they should be considered within a set of other evaluations carried out with the patient, with caution not to overload professionals even more with different evaluation and intervention requirements.

With advances in technology, health services are becoming increasingly computerized. It is necessary for information to be integrated and made available in an accessible format, simplifying and aiming to facilitate the work of professionals and, in consequence, benefiting the care provided to the patient.

Conclusion

This integrative literature review has highlighted the importance of knowledge in approaching of the total pain of oncologic patients, both in terms of scientific research and in terms of the optimization of clinical practice in palliative care. However, we have observed that the concept of total pain is still little studied and applied in clinical practice, despite scientific advances in relation to the assessment of pain.

The findings evidence the importance of evaluating pain in oncologic patients in their various contexts and suggest an approach involving combined management of pain, symptoms, and emotional distress is necessary for the relief of these people’s suffering. The evaluation of pain of people in palliative care must be done in a simple and satisfactory way, aiming to clearly understand the date of onset, the duration, and the level of pain and the factors associated with it.

The multidisciplinary team must establish coordinated therapeutic goals and projects aiming at the best management of symptoms, considering pain and suffering together and seeking measures to relieve the pain of these patients effectively. The use of multidimensional questionnaires can help identify the components of total pain and apply therapeutic resources defined according to the needs of each patient, in an integrated manner and respecting their wishes and life history.

It is fundamental that the team should look attentively at the patient’s subjectivity and that they should have knowledge and training in the use of instruments for assessing pain to identify the factors associated with the pain situation and to promote actions complementary to the drug treatment for the appropriate and effective management and control of total pain.

Limitations of the study

The present review was based on searches performed on five of the main international databases, resulting in the discovery of relevant studies on the central theme of the study. It enabled the development of a synthesis of scientific knowledge about the subject of pain in cancer, allowed the detection of gaps in the knowledge produced and offered relevant recommendations for better management of total pain in oncologic patients, in addition to the validation of the importance of a full and multidimensional evaluation.

Nevertheless, the selected publications did not present robust levels of scientific evidence, and the methodology applied in each article did not offer results that could be generalized. Therefore, the studies should be interpreted with caution, which limits the extension of these results.

Acknowledgments

None.

Footnotes

ORCID iDs: Cristiane Aparecida Gomes-Ferraz  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0425-5284

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0425-5284

Gabriela Rezende  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1355-3945

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1355-3945

Amanda Antunes Fagundes  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4939-646X

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4939-646X

Marysia Mara Rodrigues do Prado De Carlo  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3242-0769

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3242-0769

Contributor Information

Cristiane Aparecida Gomes-Ferraz, Curso de Terapia Ocupacional, Departamento de Ciências da Saúde, Faculdade de Medicina de Ribeirão Preto, Universidade de São Paulo, Av. Bandeirantes, 3900, Monte Alegre, CEP 14058-190 Ribeirão Preto, SP, BrazilNursing School of Ribeirão Preto, University of São Paulo (EERP/USP), Ribeirão Preto, Brazil.

Gabriela Rezende, Nursing School of Ribeirão Preto, University of São Paulo (EERP/USP), Ribeirão Preto, Brazil.

Amanda Antunes Fagundes, Nursing School of Ribeirão Preto, University of São Paulo (EERP/USP), Ribeirão Preto, Brazil.

Marysia Mara Rodrigues do Prado De Carlo, Curso de Terapia Ocupacional, Departamento de Ciências da Saúde, Faculdade de Medicina de Ribeirão Preto, Universidade de São Paulo, Av. Bandeirantes, 3900, Monte Alegre, CEP 14058-190 Ribeirão Preto, SP, BrazilRibeirão Preto Medical School, University of São Paulo, Ribeirão Preto, Brazil Nursing School of Ribeirão Preto, University of São Paulo (EERP/USP), Ribeirão Preto, Brazil.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate: Not applicable.

Consent for publication: Not applicable.

Author contributions: Cristiane Aparecida Gomes-Ferraz: Conceptualization; Data curation; Formal analysis; Investigation; Methodology; Project administration; Supervision; Validation; Visualization; Writing – original draft; Writing – review & editing.

Gabriela Rezende: Conceptualization; Data curation; Methodology; Writing – original draft; Writing – review & editing.

Amanda Antunes Fagundes: Conceptualization; Data curation; Writing – review & editing.

Marysia Mara Rodrigues do Prado De Carlo: Conceptualization; Methodology; Project administration; Supervision; Writing – original draft; Writing – review & editing.

Funding: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: The authors report that this work received financial support from the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES), which is a research-funding agency of the Brazilian government.

Competing interests: The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Availability of data and materials: Supplementary file: full electronic search strategy for the databases used. (((((‘Total Pain’ OR ‘Cancer Pain’[Mesh] OR ‘Cancer Pain’ OR ‘Pain’))) AND (( ‘Symptom Assessment’[Mesh] OR ‘Pain Measurement’[Mesh] OR ‘Symptom Assessment’ OR ‘Pain Measurement’ OR ‘Pain Evaluation’))) AND (( ‘Neoplasms’ [mesh] OR ‘Neoplasms’ OR ‘Cancer’ OR ‘Tumor’))) AND (( ‘Palliative Care’[Mesh] OR ‘Palliative care’ OR ‘Terminal Care’ OR ‘Hospice Care’)) (‘cancer pain’/exp OR ‘cancer pain’ OR ‘pain’/exp OR pain OR ‘total pain’) AND (‘symptom assessment’/exp OR ‘symptom assessment’ OR ‘pain measurement’/exp OR ‘pain measurement’ OR ‘pain evaluation’) AND (‘neoplasm’/exp OR neoplasms OR cancer OR tumor) AND (‘palliative care’/exp OR ‘palliative care’ OR ‘terminal care’/exp OR ‘hospice care’/exp) AND [embase]/lim NOT ([embase]/lim AND [medline]/lim)

References

- 1. American Cancer Society. Understanding advanced and metastatic cancer, https://www.cancer.org/treatment/understanding-your-diagnosis/advanced-cancer/what-is.html (2020, accessed 19 August 2020).

- 2. Brazil Ministry of Health, José Alencar Gomes da Silva National Cancer Institute. ABCs of cancer: basic approaches to cancer control. 6th revised ed. Rio de Janeiro: INCA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Raja SN, Carr D, Cohen M, et al. The revised International Association for the Study of Pain definition of pain: concepts, challenges, and compromises. Pain 2020; 161: 1976–1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Prado E, Sales CA, Girardon-Perlini NMO, et al. Experience of people with advanced cancer faced with the impossibility of cure: a phenomenological analysis. Esc Anna Nery 2022; 24: e20190113. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Tsai JS, Wu CH, Chiu TY, et al. Symptom patterns of advanced cancer in patients in a palliative care unit. Palliat Med 2006; 20: 617–622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Peters L, Sellick K. Quality of life of cancer patients receiving inpatient and home-based palliative care. J Adv Nurs 2006; 53: 524–533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Minson FP, Assis FD, Vanetti TK, et al. Interventional procedures for cancer pain management. Einstein 2012; 10: 292–295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Saunders C. The evolution of the hospices. In: Mann RD. (ed.) The history of the management of pain: from early principles to present practice [S.l.]. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press, 1988, pp. 167–178. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Whittemore R, Knafl K. The integrative review: updated methodology. J Adv Nurs 2005; 52: 546–553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med 2009; 151: 264–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Mendes KDS, Silveira RCCP, Galvão CM. Integrative literature review: a research method to incorporate evidence in health care and nursing. Texto Contexto Enferm 2008; 17: 758–764. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Stern C, Jordan Z, McArthur A. Developing the review question and inclusion criteria: the first steps in conducting a systematic review. Am J Nurs 2011; 114: 53–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Mourad O, Hossam H, Zbys F, et al. A web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst Rev 2016; 5: 210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Melnyk BM, Fineout-Overholt E. Making the case for evidence-based practice and cultivating a spirit of inquiry. In: Melnyk BM, Fineout-Overholt E. (eds) Evidence-based practice in nursing & healthcare. A guide to best practice. Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2011, pp. 3–24. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Galvão TF, Pansani TSA, Harrad D. Key items to report systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA recommendation. Epidemiol Health Serv 2015; 24: 335–342. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Mystakidou K, Tsilika E, Parpa E, et al. Exploring the relationships between depression, hopelessness, cognitive status, pain, and spirituality in patients with advanced cancer. Arch Psychiatr Nurs 2007; 21: 150–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hackett J, Godfrey M, Bennett MI. Patient and caregiver perspectives on managing pain in advanced cancer: a qualitative longitudinal study. Palliat Med 2016; 30: 711–719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. O’Connor M, Weir J, Butcher I, et al. Pain in patients attending a specialist cancer service: prevalence and association with emotional distress. J Pain Symptom Manage 2012; 43: 29–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Pathmawathi S, Beng TS, Li LM, et al. Satisfaction with and perception of pain management among palliative patients with breakthrough pain: a qualitative study. Pain Manag Nurs 2015; 16: 552–560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Arnold BL. Mapping hospice patients’ perception and verbal communication of end-of-life needs: an exploratory mixed methods inquiry. BMC Palliat Care 2011; 10: 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Black B, Herr K, Fine P, et al. The relationships among pain, nonpain symptoms, and quality of life measures in older adults with cancer receiving hospice care. Pain Med 2011; 12: 880–889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Tishelman C, Petersson L-M, Degner LF, et al. Symptom prevalence, intensity, and distress in patients with inoperable lung cancer in relation to time of death. J Clin Oncol 2007; 25: 5381–5389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Gryschek G, Machado DA, Otuyama LJ, et al. Spiritual coping and psychological symptoms as the end approaches: a closer look on ambulatory palliative care patients. Psychol Health Med 2020; 25: 426–433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Rawdin B, Evans C, Rabow MW. The relationships among hope, pain, psychological distress, and spiritual well-being in oncology outpatients. J Palliat Med 2013; 16: 167–172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Koyama A, Matsuoka H, Ohtake Y, et al. Gender differences in cancer-related distress in Japan: a retrospective observation study. BioPsychoSoc Med 2016; 10: 10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Malhotra C, Harding R, Teo I, et al. Financial difficulties are associated with greater total pain and suffering among patients with advanced cancer: results from the COMPASS study. Support Care Cancer 2020; 28: 3781–3789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Meeker CR, Geynisman DM, Egleston BL, et al. Relationships among financial distress, emotional distress, and overall distress in insured patients with cancer. J Oncol Pract 2016; 12: e755–e764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Muñoz E, Monje D, San José H. Total pain assessment at the pain relief and palliative care polyclinic of the San José Hospital Complex. Rev Dolor 2010; 54: 26–34. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Pidgeon T, Johnson CE, Currow D, et al. A survey of patients’ experience of pain and other symptoms while receiving care from palliative care services. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2016; 6: 315–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Lin J, Hsieh R-K, Chen J-S, et al. Satisfaction with pain management and impact of pain on quality of life in cancer patients. Asia Pac J Clin Oncol 2020; 16: e91–e98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Didwaniya N, Tanco K, de la Cruz M, et al. The need for a multidisciplinary approach to pain management in advanced cancer: a clinical case. Palliat Support Care 2015; 13: 389–394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Erol O, Unsar S, Yacan L, et al. Pain experiences of patients with advanced cancer: a qualitative descriptive study. Eur J Oncol Nurs 2018; 33: 28–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Mori M, Elsayem A, Reddy SK, et al. Unrelieved pain and suffering in patients with advanced cancer. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 2012; 29: 236–240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Reddy A, Hui D, Bruera E. A successful palliative care intervention for cancer pain refractory to intrathecal analgesia. J Pain Symptom Manage 2012; 44: 124–130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Satija A, Singh SP, Kashyap K, et al. Management of total cancer pain: a case of young adult. Indian J Palliat Care 2014; 20: 153–156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Butler LD, Koopman C, Cordova MJ, et al. Psychological distress and pain significantly increase before death in metastatic breast cancer patients. Psychosom Med 2003; 65: 416–426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Arantes ACLQ, Maciel MGS. Pain assessment and treatment. In: Oliveira RA. (ed.) Cuidado Paliativo. São Paulo: Conselho Regional de Medicina do Est. de São Paulo, 2008, pp. 370–391. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Brazil Ministry of Health, National Cancer Institute. Palliative cancer care: pain control. Rio de Janeiro: INCA, 2001, http://bvsms.saude.gov.br/bvs/publicacoes/inca/manual_dor.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 39. Hennemann-Krause L. End-of-life pain: assess to treat. Rev Hosp Univ Pedro Ernesto 2012; 11: 38–49. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Saunders C. The evolution of the hospice. In: Mann RD. (ed.) The hystory of the management of pain; from early principles to present practice. Parthenon Publishing, 1990, pp. 167–178. [Google Scholar]

- 41. International Society of Nurses in Cancer Care (ISNCC). Pain, position statement, https://isncc.org/Position-Statement

- 42. Silva LMH, Zago MMF. The care to cancer patients with chronic pain in the view of nurses. Rev Latinoam Enferm 2001; 9: 44–49. [Google Scholar]

- 43. De Almeida VC, Gama ESC, Espejo CAN, et al. The uniqueness of pain in cancer patients in palliative care. Mudanças Psicol Saúde 2018; 26: 75–83. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Fontes KB, Jaques AE. The interface of nursing care with cancer pain control. Arq Ciênc Saúde UNIPAR 2015; 17: 43–48. [Google Scholar]