Abstract

Human non-typhoidal salmonellosis is among the leading cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide, resulting in huge economic losses and threatening the public health systems. To date, epidemiological characteristics of non-typhoidal Salmonella (NTS) implicated in human salmonellosis in China are still obscure. Herein, we investigate the antimicrobial resistance and genomic features of NTS isolated from outpatients in Shaoxing city in 2020. Eighty-seven Salmonella isolates were recovered and tested against 28 different antimicrobial agents, representing 12 categories. The results showed high resistance to cefazolin (86.21%), streptomycin (81.61%), ampicillin (77.01%), ampicillin-sulbactam (74.71%), doxycycline (72.41%), tetracycline (71.26%), and levofloxacin (70.11%). Moreover, 83.91% of isolates were resistant to ≥3 categories, which were considered multi-drug resistant (MDR). Whole-genome sequencing (WGS) combined with bioinformatic analysis was used to predict serovars, MLST types, plasmid replicons, antimicrobial resistance genes, and virulence genes, in addition to the construction of phylogenomic to determine the epidemiological relatedness between isolates. Fifteen serovars and 16 STs were identified, with the dominance of S. I 4, [5], 12:i:– ST34 (25.29%), S. Enteritidis ST11 (22.99%), and S. Typhimurium ST19. Additionally, 50 resistance genes representing ten categories were detected with a high prevalence of aac(6')-Iaa (100%), blaTEM−1B (65.52%), and tet(A) (52.87%), encoding resistance to aminoglycosides, β-lactams, and tetracyclines, respectively; in addition to chromosomic mutations affecting gyrA gene. Moreover, we showed the detection of 18 different plasmids with the dominance of IncFIB(S) and IncFII(S) (39.08%). Interestingly, all isolates harbor the typical virulence genes implicated in the virulence mechanisms of Salmonella, while one isolate of S. Jangwani contains the cdtB gene encoding typhoid toxin production. Furthermore, the phylogenomic analysis showed that all isolates of the same serovar are very close to each other and clustered together in the same clade. Together, we showed a high incidence of MDR among the studied isolates which is alarming for public health services and is a major threat to the currently available treatments to deal with human salmonellosis; hence, efforts should be gathered to further introduce WGS in routinely monitoring of AMR Salmonella in the medical field in order to enhance the effectiveness of surveillance systems and to limit the spread of MDR clones.

Keywords: non-typhoidal Salmonella, whole genome sequencing, antimicrobial resistance, virulence, gastroenteritis, public health, salmonellosis

Introduction

Gastroenteritis is a common disease in both developing and developed countries and is considered a significant economic burden leading to high financial loss for worldwide health care systems. Most gastroenteritis cases are self-limited in immunocompetent patients. At the same time, it can persist for a long time with severe symptoms and diarrhea in immunocompromised patients, including young children and the elderly. According to recent data, over 1.7 billion global cases of diarrheal disease are reported annually, leading to about 2.2 million deaths (1). In China, infectious diarrhea, excluding cholera, dysentery, and enteric fever, caused more than one million cases annually from 2014 to 2019, which the National Notifiable Diseases Reporting System classified as Category C infectious disease (2). Bacteria take second place among the agents causing gastroenteritis after viruses (3).

Non-typhoidal Salmonella (NTS) are among the most common etiological agents causing acute gastroenteritis worldwide. It is estimated that Salmonella species were responsible for about 180 million (9%) of the diarrheal diseases that occur globally each year, leading to 298,000 deaths, representing 41% of all diarrheal disease-associated deaths (4, 5). In China, the incidence of non-typhoidal salmonellosis was estimated at 626.5 cases per 100,000 persons (6). Salmonella is a Gram-negative, rod-shaped, non-spore-forming, and facultatively anaerobic bacterium, belonging to the Enterobacteriaceae family. To date, more than 2,600 Salmonella serovars have been described (7), where only some of them were reported to cause human salmonellosis (8–17). The digestive tract of vertebrates is considered the main reservoir of Salmonella species, and animal farms are the primary source for the development and dissemination (6, 18–22). Salmonella might contaminate animal carcasses during transport, slaughtering, and then transmitted to humans via the farm-to-fork route (23–30), causing severe infections and threatening public health systems.

Antibiotics have been widely used to treat salmonellosis in the veterinary or medical fields. However, since the 1950s, resistance to the usual antimicrobial agents has appeared and increased until rising the threatened limits. Currently, the third-generation cephalosporins and quinolones are used as the last line of defense to treat salmonellosis in both adult and young patients, while polymyxins are used to treat the cases of multidrug resistance Enterobacteriaceae (31, 32). However, recent investigations have reported the resistance of Salmonella isolates recovered from animal farms, food chain processes, foods, and humans to different antibiotics, including the third-generation cephalosporins, quinolones, polymyxins, aminoglycosides, and others (18, 31, 33), with the usual detection of superbug isolates which further complicates the epidemiological situation and is considered a serious threat to public health by limiting choices for therapeutic treatment of patients (34).

In this regard, the earlier detection and accurate diagnosis of multidrug-resistant (MDR) isolate based on high throughput surveillance are the key solutions to limit the spread and dissemination of harmful superbug clones. Today the advance in high throughput sequencing encourages the use of WGS on a large scale for the epidemiological investigation to monitor MDR pathogens (23, 35). Additionally, the ongoing decreases in sequencing costs and the increase of online platforms available for analyzing, sharing, and comparing genomic data, enormously helped the harmonization use of WGS in different areas (36–38). In China, several cases of human salmonellosis were recorded each year, however, the in-depth analysis of the implicated Salmonella isolates is still obscure. To proof of concept, this study aims to use WGS as a cost-effective method to provide genomic features, including MLST patterns, antimicrobial resistance and virulence genes, plasmid replicons, and genetic diversity of Salmonella isolates recovered from outpatients in Shaoxing city, Zhejiang province, China.

Materials and methods

Sample collection and Salmonella identification

A total of 87 Salmonella isolates were collected from outpatients in different counties (Zhuji, Shengzhou, Xinchang, Keqiao, Shangyu, and Yuecheng) of Shaoxing city, Zhejiang province, China (Supplementary Table S1). During the year 2020, diarrheal samples were collected from outpatients having gastroenteritis. Salmonella isolates were isolated, identified, and characterized according to the previously described methods (11, 12, 14, 16). Briefly, a 10 mL buffered peptone water was used for the pre-enrichment of human fecal samples (Oxoid, United Kingdom), then 0.1 mL of the pre-enriched samples were added to 10 mL of Rappaport Vassiliadis broth (Oxoid, United Kingdom) and incubated at 42°C for 24 h. After incubation, the samples were streaked onto Xylose Lysine Desoxycholate (XLD) (Oxoid, United Kingdom) and incubated at 37°C for 18–24 h. The suspected colonies of Salmonella on XLD were round, transparent red or pink with or without typical black centers. The suspected colonies were confirmed using matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS) and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) to amplify the invA gene using specific primers as described previously (5, 16, 39). Furthermore, The PCR-confirmed Salmonella isolates were serotyped by slide agglutination method to define O and H antigens using commercial antisera (SSI Diagnostica, Hillerød, Denmark) according to White–Kauffmann–Le Minor scheme (40).

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing

The antimicrobial susceptibility of the studied Salmonella isolates was evaluated toward a panel of 28 different antimicrobial agents belonging to 12 categories by using the broth dilution method. The tested antimicrobial agents were as follow: Penicillins (Ampicillin, AMP), β-lactam combination agents (Amoxicillin-clavulanic acid, AMC; Ampicillin-sulbactam, SAM), Aminoglycosides (Amikacin, AMK; Gentamicin, GEN; Kanamycin, KAN; Streptomycin, STR), Tetracyclines (Tetracycline, TET; Minocycline, MIN; Doxycycline, DOX); Phenicols (Chloramphenicol, CHL), Folate pathway inhibitors (Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, SXT; Sulfafurazole, SIZ); Cephems (Cefazolin, CFZ; Cefoxitin, FOX; Cefotaxime, CTX; Ceftazidime, CAZ; Cefepime, FEP); Carbapenems (Imipenem, IPM; Meropenem, MEM); Quinolones (Nalidixic acid, NAL; Ciprofloxacin, CIP; levofloxacin, LVX; Gemifloxacin, GEM); Macrolides (Azithromycin, AZM); Lipopeptides (Colistin, CST; Polymyxin B, PMB); Monobactams (Aztreonam, ATM) (Table 1). The interpretation of results was performed according to the recommendation of the Clinical Laboratory Standard Institute guidelines (CLSI), and the European Committee for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST) (41, 42), and the isolates presented intermediate resistance were considered resistant for the ease of analysis. However, isolates that are non-susceptible to at least one antimicrobial agent in three or more than three antimicrobial categories were considered multidrug-resistant (MDR) (43). Escherichia coli ATCC 25922 was used as a control strain.

Table 1.

Antimicrobial susceptibility percentage of Salmonella (n = 87) isolated from outpatients.

| Antimicrobial agent | Code | Concentration range (μg/ mL) | Breakpoint interpretive criteria (μg/mL)* | Results in percentage (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S | I | R | S | R** | |||

| Aminoglycosides | |||||||

| Amikacin | AMK | 0.5–128 | ≤16 | 32 | ≥64 | 87 (100%) | 0 (0%) |

| Gentamicin | GEN | 0.12–128 | ≤4 | 8 | ≥16 | 77 (88.51%) | 10 (11.49%) |

| Kanamycin | KAN | 0.5–128 | ≤16 | 32 | ≥64 | 82 (94.25%) | 5 (5.75%) |

| Streptomycina | STR | 0.5–128 | ≤8 | 16 | ≥32 | 16 (18.39%) | 71 (81.61%) |

| β-lactam combination agents | |||||||

| Amoxicillin-clavulanic acid | AMC | 0.25/0.12–128/64 | ≤8/4 | 16/8 | ≥ 32/16 | 65 (74.71%) | 22 (25.29%) |

| Ampicillin-sulbactam | SAM | 0.25/0.12–128/64 | ≤8/4 | 16/8 | ≥ 32/16 | 22 (25.29%) | 65 (74.71%) |

| Tetracyclines | |||||||

| Tetracycline | TET | 0.12–128 | ≤4 | 8 | ≥16 | 25 (28.74%) | 62 (71.26%) |

| Minocycline | MIN | 0.12–128 | ≤4 | 8 | ≥16 | 40 (45.98%) | 47 (54.02%) |

| Doxycycline | DOX | 0.12–128 | ≤4 | 8 | ≥16 | 24 (27.59%) | 63 (72.41%) |

| Folate pathway inhibitors | |||||||

| Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole | SXT | 0.25/4.75–32/608 | ≤2/38 | – | ≥4/76 | 63 (72.41%) | 24 (27.59%) |

| Sulfafurazoleb | SIZ | 16–512 | ≤256 | – | ≥512 | 32 (36.78%) | 55 (63.22%) |

| Cephems | |||||||

| Cefazolin | CFZ | 0.032–64 | ≤2 | 4 | ≥8 | 12 (13.79%) | 75 (86.21%) |

| Cefoxitin | FOX | 0.5–128 | ≤8 | 16 | ≥32 | 87 (100%) | 0 (0%) |

| Cefotaxime | CTX | 0.032–64 | ≤1 | 2 | ≥4 | 78 (89.66%) | 9 (10.34%) |

| Ceftazidime | CAZ | 0.032–64 | ≤4 | 8 | ≥16 | 81 (93.10%) | 6 (6.90%) |

| Cefepime | FEP | 0.032–64 | ≤2 | – | ≥16 | 85 (97.70%) | 2 (2.30%) |

| Carbapenems | |||||||

| Imipenem | IPM | 0.12–64 | ≤1 | 2 | ≥4 | 86 (98.85%) | 1 (1.15%) |

| Meropenem | MEM | 0.12–64 | ≤1 | 2 | ≥4 | 86 (98.85%) | 1 (1.15%) |

| Quinolones | |||||||

| Nalidixic acid | NAL | 0.5–128 | ≤16 | – | ≥32 | 51 (58.62%) | 36 (41.38%) |

| Ciprofloxacin | CIP | 0.004–16 | ≤0.06 | 0.12~0.5 | ≥1 | 28 (32.18%) | 59 (67.82%) |

| Levofloxacin | LVX | 0.004–16 | ≤0.12 | 0.25~1 | ≥2 | 26 (29.89%) | 61 (70.11%) |

| Gemifloxacin | GEM | 0.004–16 | ≤0.25 | 0.5 | ≥1 | 72 (82.76%) | 15 (17.24%) |

| Macrolides | |||||||

| Azithromycin | AZM | 0.5–128 | ≤16 | – | ≥32 | 81 (93.10%) | 6 (6.90%) |

| Lipopeptides | |||||||

| Colistin | CST | 0.12–32 | ≤2 | – | ≥4 | 67 (77.01%) | 20 (22.99%) |

| Polymyxin B | PMB | 0.12–32 | ≤2 | – | ≥4 | 73 (83.91%) | 14 (16.09%) |

| Monobactams | |||||||

| Aztreonam | ATM | 0.25–64 | ≤4 | 8 | ≥16 | 79 (90.80%) | 8 (9.20%) |

| Penicillins | |||||||

| Ampicillin | AMP | 0.5–64 | ≤8 | 16 | ≥32 | 20 (22.99%) | 67 (77.01%) |

| Phenicols | |||||||

| Chloramphenicol | CHL | 0.5–128 | ≤8 | 16 | ≥32 | 59 (67.82%) | 28 (32.18%) |

S, susceptible; I, intermediate resistance; R, resistant.

Intermediate results were merged with resistant results.

For streptomycin, we used the same MIC breakpoints as for netilmicin.

For Sulfafurazole, we used the same MIC breakpoints as for sulfonamides.

Genomic DNA extraction and sequencing

The genomic DNA of all the studied isolates were extracted using TIANamp bacteria DNA kit (Tiangen Biotech, China) according to the manufacturer's instructions, from overnight cultures in Luria–Bertani (LB) broth incubated at 37 °C. The obtained genomic DNA was quantified using a Qubit 2.0 fluorometer (Invitrogen, USA) and then sequenced by using Illumina NovaSeq 6000 platform as previously described (14, 20, 35).

Bioinformatic analysis

The obtained raw reads were checked for sequencing quality using FastQC and trimmed using Trimmomatic (44), in which the low-quality sequences and joint sequences were removed. The clean data were then assembled using SPAdes 4.0.1 (45) with “careful” correction option to reduce the number of mismatches in the final assembly and annotated by using the Rapid Annotation Subsystem Technology (RAST) server (https://rast.nmpdr.org/) and Prokka v.1.14 (46). The assembled contigs were then used to predict plasmid replicons and antimicrobial-resistance genes using PlasmidFinder 2.1 (https://cge.cbs.dtu.dk/services/PlasmidFinder/) and ResFinder 3.2 tools (https://cge.cbs.dtu.dk/services/ResFinder/), respectively, with a similarity cut-off of 90%. The prediction of serovar and sequence type were performed using SeqSero 1.2 (https://cge.food.dtu.dk/services/SeqSero/) and MLST 2.0 (https://cge.food.dtu.dk/services/MLST/) available on the Center for Genomic Epidemiology (CGE) platform. The genomic mutations affecting the quinolone resistance-determining region (QRDR) were detected by using Staramr software against PointFinder v1.9 (https://github.com/phac-nml/staramr). Additionally, virulence genes were predicted using the virulence factors database (VFDB) (47). All bioinformatic analyses were conducted on our in-house Galaxy platform as previously described (20). On the other hand, the association between antimicrobial resistance genes and the corresponding plasmid replicons has been investigated according to the method described previously (18).

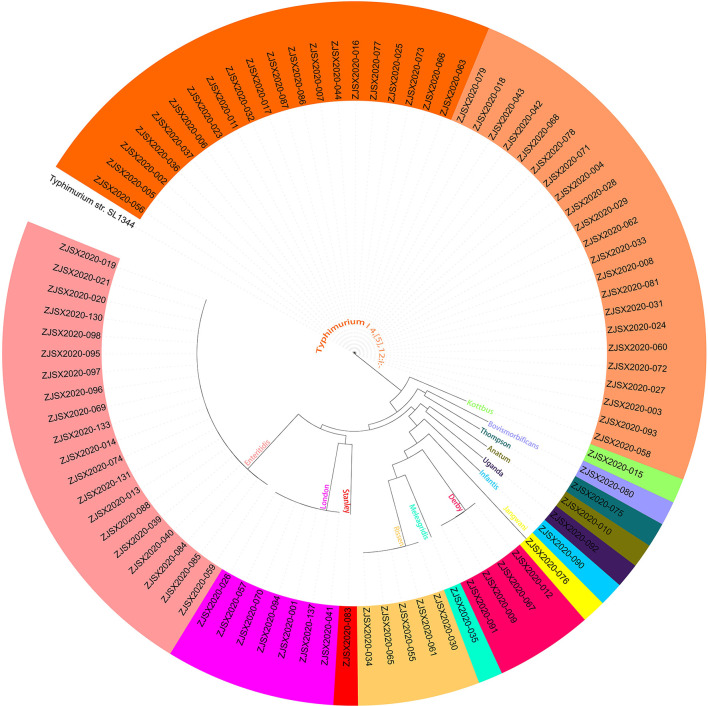

Phylogenomic analysis

The core single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) of all the studied Salmonella strains was analyzed using Snippy v4.4.4 against the reference strain S. Typhimurium SL 1344. The phylogenetic tree was constructed using IQ-TREE v.1.6.12 with TVM + F + ASC model and 1,000 bootstraps, as previously described (13, 22). Moreover, the whole-genome multilocus sequence typing (wgMLST) was used to conduct wgMLST phylogenomic tree by using cano-wgMLST_Bac Compare software as described recently (20, 48), with default parameters and S. Typhimurium strain SL 1344 as reference strain.

Results

Distribution of Salmonella serovars

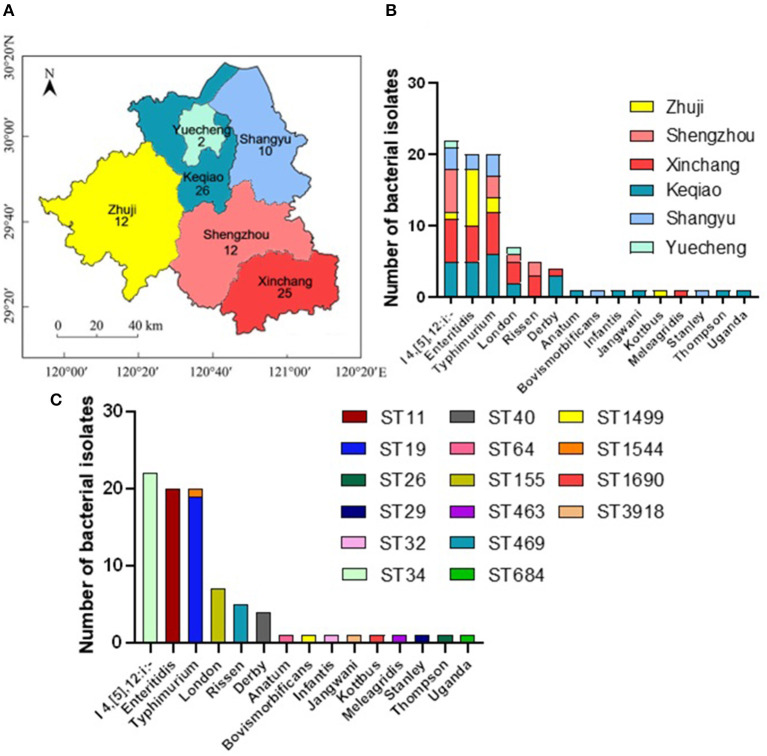

In this study, 87 Salmonella isolates have been isolated and identified, including 26 from Keqiao county (29.88%), 25 from Xinchang (28.74%), 12 from Zhuji (13.79%), 12 from Shengzhou (13.79%), ten from Shangyu (11.49%), and two from Yuecheng (2.30%) (Figure 1A). These isolates have been shared between male (44/87; 50.57%) and female (49.43%) patients (Supplementary Table S1). The serotyping method has identified 15 different serovars with the dominance of the monophasic variant I 4, [5], 12:i:– (22/87; 25.29%), followed by Enteritidis (20/87; 22.99%), and Typhimurium (Figure 1B). Additionally, allelic profiles analysis showed the identification of 16 sequence types (STs) with the dominance of ST34 (22/87; 25.29%), ST11 (20/87; 22.99%), and ST19 (19/87; 21.84%) (Figure 1C). All serovars presented one ST, except S. Typhimurium, which was divided into ST19 (n = 19) and ST1544 (n = 1).

Figure 1.

The distribution of different serovars among six counties in Shaoxing city, Zhejiang province, China. (A) The geographical distribution of the Salmonella isolates in Shaoxing with six counties which were examined in current investigations. N.B., The number indicates the numbers of isolates collected from individual county. (B) The distribution of fifteen serovars of Salmonella isolates. The dominant serovars are S. I 4, [5], 12:i:-, S. Enteritidis, and S. Typhimurium. (C) The prevalence of individual serovar with their sequence type (ST) detected in this study.

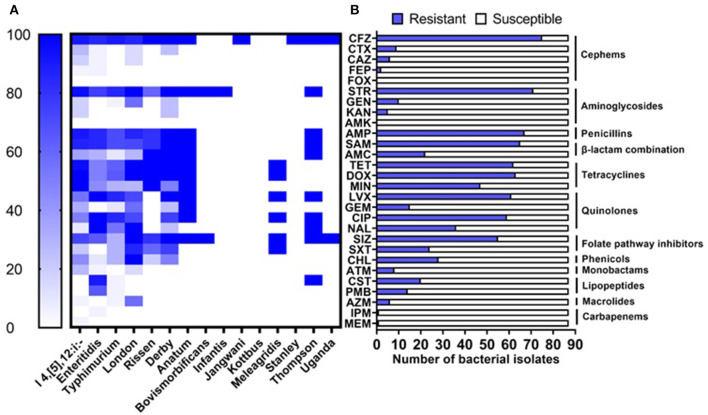

Phenotypic antimicrobial resistance

Phenotypic antimicrobial susceptibility of the 87 isolates has been evaluated toward 28 antimicrobial agents representing 12 different categories by broth dilution method according to CLSI and EUCAST recommendations. The highest resistance was observed against cefazolin (75/87; 86.21%), streptomycin (71/87; 81.61%), ampicillin (67/87; 77.01%), the combination of ampicillin-sulbactam (65/87; 74.71%), doxycycline (63/87; 72.41%), tetracycline (62/87; 71.26%), and levofloxacin (61/87; 70.11%), while all isolates were susceptible to cefoxitin and amikacin (Table 1, Figure 2B). Based on serovars distribution, our results showed that the abundant serovars (>3 isolates), especially the monophasic variant I 4, [5], 12:i:–, Enteritidis, Typhimurium, London, and Derby, present high resistance to multiple antimicrobial agents (Figure 2A). Additionally, we detected 57 different antimicrobial resistance patterns, in which 85/87 (97.70%) of isolates presented resistance to at least one category, 73/87 (83.91%) given resistance to three or more than three categories which were considered MDR. In contrast, 67/87 (77.01) isolates were resistant to five or more antimicrobial categories (Supplementary Table S2).

Figure 2.

Antimicrobial resistance of Salmonella isolates. (A) Resistance of isolates grouped by serovars to the tested antimicrobial agents. (B) Prevalence of resistance against 28 antimicrobial agents belonging to 12 categories.

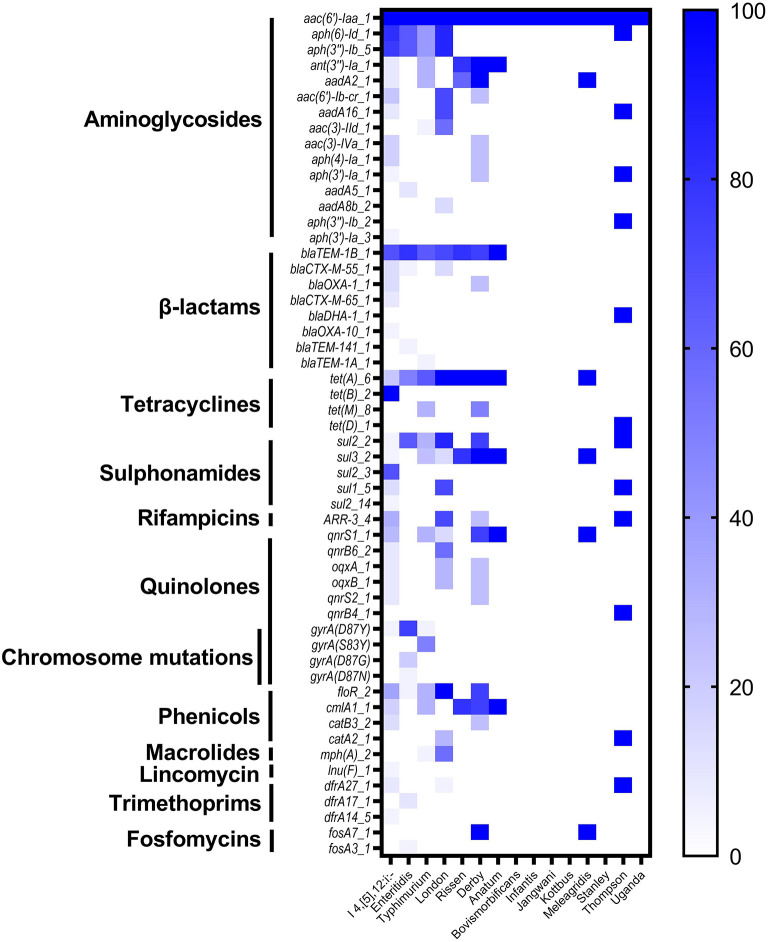

Genotypic antimicrobial resistance

In order to understand the genetic arsenal behind the acquisition of antimicrobial resistance. The whole genome sequences of all isolates (n = 87) were screened for the detection of antimicrobial determinants encoding resistance to different antimicrobial categories, in addition to genomic mutations in the quinolone resistance-determining region (QRDR) affecting the DNA gyrase and DNA topoisomerase IV genes. The results showed the detection of 50 determinants encoding resistance to 11 different antimicrobial categories, in addition to four different mutations on the gene gyrA encoding resistance to quinolone (Supplementary Table S1). The most prevalent antimicrobial determinants were aac (6')-Iaa_1 (100%), aph (6)-Id_1 (52.87%), and aph (3”)-Ib_5 (50.57%) encoding resistance to aminoglycosides, blaTEM−1B_1 (65.52%) encoding resistance to β-lactams, and tet (A)_6 (52.87%) encoding resistance to tetracyclines (Supplementary Table S1). The monophasic variant of S. Typhimurium I 4, [5], 12:i:– harbors more diversified resistance genes (36 genes) followed by serovars London and Derby (22 genes for each one), while serovars Typhimurium and Enteritidis harbor 18 and 15 resistance genes, respectively (Figure 3). Additionally, genomic mutations conferring resistance to quinolones were only detected in serovars I 4, [5], 12:i:–, Enteritidis, and Typhimurium, where single and double mutations in the gene gyrA were observed (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

The heatmap of antimicrobial resistance genes (ARGs) and chromosomic mutations in the studied Salmonella isolates.

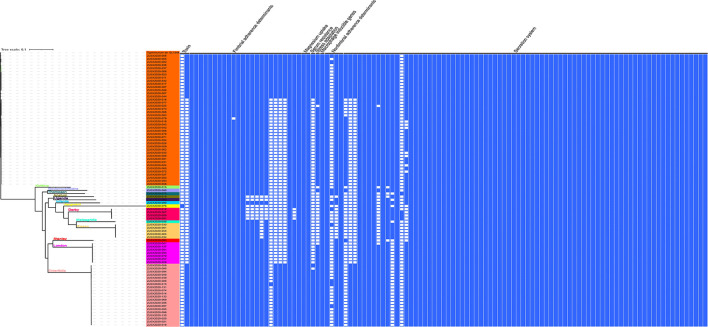

Virulence genes prediction

To provide accurate data about the virulence of studied isolates, we conducted an in-depth analysis to predict virulence genes implicated in the virulence and pathogenicity mechanism of Salmonella based on WGS, and the results were presented in Figure 4 and Supplementary Table S1. We detected 117 different virulence genes and the number of genes per isolate varies between 92 and 112. In addition to the typical virulence genes carried on Salmonella pathogenicity islands (SPIs), we detected cdtB gene encoding typhoid toxin production in one isolate of S. Jangwani. The spv locus that clustered genes implicated in the virulence system of non-typhoid Salmonella, the pef locus clustered genes encoding fimbriae, and rck gene encoding serum resistance, were only detected in Salmonella serovars Typhimurium and Enteritidis. Furthermore, sodCI gene encoding for stress adaptation was detected in the monophasic variant I 4, [5], 12:i:–, S. Typhimurium, S. Enteritidis, S. London, and S. Bovismorbificans. While the gene grvA encoding for anti-virulence was detected in serovars London, Typhimurium, and Bovismorbificans.

Figure 4.

The combinatorial graph of the wgMLST phylogenomic evolutionary tree and virulence genes in the studied Salmonella isolates. The presence of virulence gene was marked with blue color while the absence was marked with white color. The tree was rooted by using S. Typhimurium SL 1344.

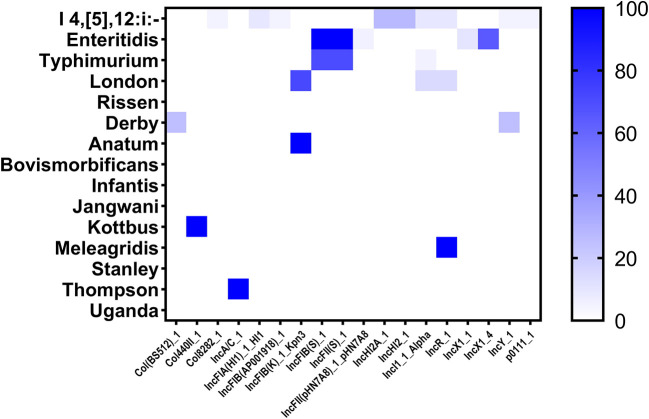

Plasmid replicons

The distribution of plasmid replicons among the studied Salmonella isolates was performed by screening the whole genome sequences in the PlasmidFinder tool. In this study, 18 different plasmids were detected where the plasmids IncFIB (S)_1 and IncFII (S)_1 were the most prevalent (34/87; 39.08% for each one), followed by IncX1_4 (13/87; 14.94%), and IncHI2A_1, IncHI2_1 and IncFIB(K)_1_Kpn3 (6/87; 6.90% for each one) (Supplementary Table S1). Additionally, we reported that the monophasic variant I 4, [5], 12:i:– harbors more diversified plasmids (n = 9) compared with other serovars, followed by Enteritidis (n = 5); However, isolates belonging to serovars Rissen, Bovismorbificans, Infantis, Jangwani, Stanley, and Uganda didn't harbor any plasmid (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

The heatmap of plasmids distribution in different Salmonella isolates. The strength of the colors corresponds to the numerical value of the prevalence of the plasmids. Dark blue color indicates high prevalence and white color for gene absence.

Association of plasmids and antimicrobial resistance genes

The association between plasmid replicons and antimicrobial resistance genes has been investigated and the results are presented in Supplementary Table S3. We demonstrated that the plasmid type IncX1 was the main carrier of antimicrobial resistance, carrying multiple resistance genes like sul2, aph (3”)-Ib, aph (6)-Id, tet (A) encoding resistance to sulphonamides, aminoglycosides, and tetracyclines, respectively. However, the plasmid types IncFII(S) and IncFIB(S) were the leading carriers of the gene blaTEM−1B encoding resistance to β-lactam. Notably, the co-occurrence between plasmid replicons and antimicrobial resistance genes was mainly observed in serovar Enteritidis.

Phylogenomic analysis

The sequenced and assembled genomes have been first checked for quality assessment and results were presented in Supplementary Table S4. The results showed that the number of contigs (≥300 bp) varies between 30 and 117 contigs while the average genomes size of draft assemblies was 4,920,864 bp and the average N50 was 320,121 bp. Moreover, to determine the epidemiological relatedness between the studied Salmonella isolates, we conducted a phylogenomic analysis based on core single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) and whole-genome multilocus sequence typing (wgMLST) (Figure 4, 6). The results showed that isolates belonging to the same serovar are very close to each other and clustered together in the same clade. A substantial similarity has been seen between isolates of the monophasic variant I 4, [5], 12:i: and Typhimurium, which were grouped in the same clade. Moreover, isolates of serovars Enteritidis, London, and Stanley have been grouped in the same clade indicating a high association between them. Furthermore, the association between phylogenomic tree and distribution of virulence factors showed few differences in the patterns of virulence factor cassettes between different serovars (Figure 4).

Figure 6.

The core genome SNP-based phylogenomic tree by maximum likelihood (TVM+F+ASC) of 87 Salmonella isolates. The tree was rooted by using S. Typhimurium SL 1344.

Discussion

Non-typhoidal salmonellosis is a common disease caused by the bacteria Salmonella, leading to a huge economic burden, which threatens healthcare systems worldwide (49–51). Salmonella originated from animal reservoirs are transmitted to humans via the food chain causing gastroenteritis and sometimes invasive infections. Generally, the consumption of food or water contaminated with NTS is the leading cause of human salmonellosis. In this study, we presented the epidemiological characteristics of NTS isolates recovered from outpatients in Shaoxing city based on WGS combined with accurate bioinformatics tools and in-depth phenotypic methods, these results may provide the scientific background about the MDR Salmonella circulated in Chinese hospitals and may help health service authorities to implement effective programs to limit the spread and dissemination of MDR clones in medical field.

In this study, 87 Salmonella isolates were identified, these isolates belonged to 15 different serovars and 16 STs. The dominant serovar was the monophasic variant I 4, [5], 12:i:– ST34, followed by S. Enteritidis ST11, and S. Typhimurium ST19. These serovars are currently considered the most common serovars implicated in human salmonellosis (52, 53). Since the mid-1990s, the implication of the monophasic variant I 4, [5], 12:i:– in human salmonellosis has significantly increased, which is currently classified among the most five predominant serovars in NTS infections (52, 54). However, S. Enteritidis is well known as a worldwide foodborne pathogen and is widely linked to the consumption of egg-derived products (55, 56). In China, S. Typhimurium is considered the most common serovar causing NTS infections. Ke et al. reported that S. Typhimurium was the most predominant serovar (62.6%) among isolates recovered from children between 2012 and 2019 in a tertiary hospital in Ningbo, Zhejiang, China (57). Similarly, Wu et al. showed the dominance of S. Typhimurium (79.2%) among isolates recovered from children with NTS infections between 2009 and 2018 in Chongqing, China (58). Another Chinese study carried out in the Conghua district of Guangzhou, between June and October 2020 isolated S. Typhimurium as the most common serovar in hospitalized patients (59). Moreover, in Vietnam S. Typhimurium dominated NTS isolates (41.8%) from hospitalized children in Ho Chi Minh city, Vietnam (60). In Thailand, Sinwat et al. reported S. Typhimurium as the major serovar for diarrhoeal patients (61). The wide spread of S. Typhimurium among patients in Southeast Asian countries could be due to the common source of contamination, especially with the high trading exchange between these countries.

In order to provide accurate epidemiological information about the current antimicrobial susceptibility situation of clinical NTS, all the isolated strains were tested against a panel of 28 different antimicrobial agents belonging to 12 categories. The common resistance was observed against cefazolin (1st generation of cephalosporin), streptomycin (aminoglycoside), ampicillin (penecillins), the combination of ampicillin-sulbactam, doxycycline and tetracycline (tetracyclines), and levofloxacin (quinolones). The high resistance to these categories has becoming frequently observed in Salmonella isolates recovered from food, human, and animal samples (6, 19, 25, 26, 58, 62). Moreover, we reported a high incidence of MDR among isolates (83.91%) which was higher than that found in Salmonella recovered from hospitalized patients in the Conghua district of Guangzhou, China (47.06%) (59), and from children with NTS infections in Chongqing, China (13.7%) (58). Indeed, the extensive and continued use of antibiotics in medical and veterinary fields has led to the development of MDR strains which threaten public health by limiting the effectiveness of available antimicrobials for therapeutic usage. Hence, infections with these MDR isolates may lead to therapeutic failure, especially with the limit in alternative antibiotics able to treat these cases.

The screening of antimicrobial resistance genes was performed based on WGS and results showed the detection of 50 genes encoding resistance to 11 categories in addition to 4 mutations affecting the gene gyrA. All isolates (100%) were positive for the genes aac (6')-Iaa encoding resistance to aminoglycosides, while 65.52% contain blaTEM−1B encoding resistance to β-lactams and 52.87% contain tet (A) gene encoding resistance to tetracyclines. Generally, resistance to aminoglycosides is associated with enzymatic modification by using certain enzymes, including aminoglycoside phosphotransferases, aminoglycoside acetyltransferases, and aminoglycoside adenyltransferases encoded by the genes aphA, aacC, and aadA, respectively (63, 64). Resistance to β-lactams is mediated by bla genes encoding enzymes (β-lactamases) capable of hydrolyzing the β-lactam ring of β-lactam antibiotics. In this study, we detected bla genes in predominant serovars, including the monophasic variant I 4, [5], 12:i:–, Enteritidis, Typhimurium, in addition to serovars London, Rissen, Derby, Anatum, and Thompson. Thus, it has been reported that different types of blaTEM are mostly linked with ampicillin-resistant Salmonella serovars (65), which may explain the high incidence of ampicillin resistance. We also detected the tet genes encoding resistance to tetracyclines, in addition to different genes encoding resistance to chloramphenicol. Resistance to tetracyclines and chloramphenicol is often associated with efflux pumps mechanisms encoded by tet and floR genes, respectively; yet, resistance to chloramphenicol may also be associated with modification of the antibiotic target by chloramphenicol acetyltransferases encoded by cat genes (66). Moreover, the genes sul1-3, mediating resistance to sulphonamides, have been detected in all predominant serovars, while genes dfrA encoding resistance to trimethoprim were only detected in the monophasic variant I 4, [5], 12:i:–, Enteritidis, London, and Thompson. Furthermore, the genes qnr encoding decreased susceptibility to quinolones were detected in the monophasic variant I 4, [5], 12:i:–, Typhimurium, London, Derby, Anatum, Meleagridis, and Thompson. The resistance to quinolones could be due to the acquisition of resistance genes carried on mobile plasmids as well as the presence of chromosomic mutations affecting gyr and par genes (18, 67).

The virulome analysis of the studied isolates showed the detection of the typical genes implicated in the virulence and pathogenicity mechanisms of Salmonella. In addition, the gene cdtB encoding typhoid toxin production was detected in one isolate of S. Jangwani. In fact, cdtB gene has become commonly detected in NTS isolates from different sources (5, 12, 14, 18, 20, 23). It is noted that typhoid toxin was first found in S. Typhi and then several NTS serovars have been reported to carry genes encoding the production of this toxin, especially cdtB, suggesting the implication of this gene in the development of invasion non-typhoidal salmonellosis. Moreover, we reported the detection of spv, pef, and rck genes in isolates belonging to serovars Typhimurium and Enteritidis. The genes clustered in the spv locus have been demonstrated to possess an essential role in the virulence pathway of NTS (68, 69). The pef fimbrial operon mediates adhesion to the murine small intestine (70), while rck gene enhances bacterial adhesion and invasion and confers resistance to antimicrobial agents (71). On the other hand, sodCI confers resistance to oxidative burst inside macrophages (72, 73). Interestingly, these genes are carried on mobile genetic elements, including plasmids and phages, horizontally transferred between serovars, which may confer a virulence potential to new serovars that have not been reported to cause human gastroenteritis.

Mobile genetic elements are the leading factors for the high spread of antimicrobial resistance by transferring resistance and virulence genes between bacteria. In this study, we detected 18 different plasmids with the dominance of IncFIB(S) and IncFII(S). These plasmids may carry pef genes mediated adhesion to the murine on intestine (74), and spv genes necessary to the virulence pathway of NTS (75), in addition to their ability to confer hypervirulence and bacterial fitness (76). As known, the distribution of some plasmids is serovar dependent. In this study, we reported the detection of plasmids IncFIB(S) and IncFII(S) in S. Enteritidis and S. Typhimurium, while the plasmids IncHI2A and IncHI2 were only detected in S. I 4, [5], 12:i:–. Moreover, the association between plasmids and antimicrobial resistance genes showed that the plasmid type IncX1 is the leading carrier of the resistance genes sul2, aph (3”)-Ib, aph (6)-Id, tet (A) in S. Enteritdis. These results are in accord with those reported by Li et al. showing that the plasmid IncX1 is the key carrier of antimicrobial resistance determinants like blaTEM−1B, sul1, sul2, aph (6)-Id, ant (3”)-Ia, aadA5, dfrA17, dfrA1, and tet(A) in S. Enteritidis (18). Otherwise, Elbediwi et al. reported a strong positive correlation between the plasmids IncHI2 and IncHI2A and the resistance genes sul1, dfrA12, armA, and blaTEM−1B (20). Therefore, the detection of Salmonella isolates harboring plasmids carrying virulence and resistance genes is a significant threat to public health.

Conclusion

To date, few studies have investigated the epidemiological characteristics of NTS isolated from outpatients in China. Herein, we presented accurate information about the epidemiology of NTS implicated in human salmonellosis in Shaoxing city, Zhejiang province, China, by using whole-genome sequencing combined with in-depth bioinformatics analysis and cutting-edge phenotypic methods. Fifteen different serovars and 16 STs have been identified with the dominance of S. I 4, [5], 12:i:– ST34, S. Enteritidis ST11, and S. Typhimurium ST19, which were considered the leading cause of non-typhoidal salmonellosis in China and elsewhere. Interestingly, we showed that most isolates are MDR (83.91%) and harbor different antimicrobial genetic determinants carried on transferable plasmids, in addition to critical virulence genes implicated in the pathogenicity pathways of NTS. Hence the high incidence of MDR isolates in clinical NTS is a real issue for public health, threatening the current therapeutic procedures, which requires continuous monitoring of “superbugs” isolates using whole-genome sequencing.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genbank/, PRJNA844576.

Author contributions

JC and AE-D analyzed the data and finalized the figures. AE-D and MY wrote the manuscript. HZ and BW did the experiment and data collection. MY and YZ conceived the idea and assisted with data analysis and writing. All authors have read, revised, and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Program on Key Research Project of China (2019YFE0103900) as well as the European Union's Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Programme under Grant Agreement No. 861917 – SAFFI, the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31872837 and 32150410374), Zhejiang Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (LR19C180001), and Zhejiang Provincial Key R&D Program of China (2022C02024; 2021C02008; and 2020C02032).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpubh.2022.988317/full#supplementary-material

References

- 1.Humphries RM, Linscott AJ. Practical guidance for clinical microbiology laboratories: diagnosis of bacterial gastroenteritis. Clin Microbiol Rev. (2015) 28:3–31. 10.1128/CMR.00073-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cao RR, Ma XZ, Li WY, Wang BN, Yang Y, Wang HR, et al. Epidemiology of norovirus gastroenteritis in hospitalized children under five years old in western China, 2015–2019. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. (2021) 54:918–25. 10.1016/j.jmii.2021.01.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Oppong TB, Yang H, Amponsem-Boateng C, Kyere EKD, Abdulai T, Duan G, et al. Enteric pathogens associated with gastroenteritis among children under 5 years in sub-saharan Africa: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Epidemiol Infect. (2020) 148:e64. 10.1017/S0950268820000618 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Besser JM. Salmonella epidemiology: a whirlwind of change. Food Microbiol. (2018) 71:55–9. 10.1016/j.fm.2017.08.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liu Y, Jiang J, Ed-Dra A, Li X, Peng X, Xia L, et al. Prevalence and genomic investigation of Salmonella isolates recovered from animal food-chain in Xinjiang, China. Food Res Int. (2021) 142:110198. 10.1016/j.foodres.2021.110198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Xu Y, Zhou X, Jiang Z, Qi Y, Ed-Dra A, Yue M. Epidemiological investigation and antimicrobial resistance profiles of Salmonella isolated from breeder chicken hatcheries in Henan, China. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. (2020) 10:497. 10.3389/fcimb.2020.00497 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guibourdenche M, Roggentin P, Mikoleit M, Fields PI, Bockemühl J, Grimont PAD, et al. Supplement 2003–2007 (No. 47) to the White-Kauffmann-Le Minor scheme. Res Microbiol. (2010) 161:26–9. 10.1016/j.resmic.2009.10.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pan H, Zhou X, Chai W, Paudyal N, Li S, Zhou X, et al. Diversified sources for human infections by Salmonella enterica serovar newport. Transbound Emerg Dis. (2019) 66:1044–8. 10.1111/tbed.13099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Biswas S, Li Y, Elbediwi M, Yue M. Emergence and dissemination of mcr-carrying clinically relevant Salmonella typhimurium monophasic clone st34. Microorganisms. (2019) 7:298. 10.3390/microorganisms7090298 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Elbediwi M, Pan H, Biswas S, Li Y, Yue M. Emerging colistin resistance in Salmonella enterica serovar Newport isolates from human infections. Emerg Microbes Infect. (2020) 9:535–8. 10.1080/22221751.2020.1733439 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Paudyal N, Pan H, Wu B, Zhou X, Zhou X, Chai W, et al. Persistent asymptomatic human infections by Salmonella enterica serovar Newport in China. mSphere. (2020) 5:e00163-20. 10.1128/mSphere.00163-20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xu X, Chen Y, Pan H, Pang Z, Li F, Peng X, et al. Genomic characterization of Salmonella Uzaramo for human invasive infection. Microb genomics. (2020) 6:mgen000401. 10.1099/mgen.0.000401 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Elbediwi M, Pan H, Zhou X, Rankin SC, Schifferli DM, Yue M. Detection of mcr-9-harbouring ESBL-producing Salmonella Newport isolated from an outbreak in a large-animal teaching hospital in the USA. J Antimicrob Chemother. (2021) 76:1107–9. 10.1093/jac/dkaa544 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Qiu Y, Nambiar RB, Xu X, Weng S, Pan H, Zheng K, et al. Global genomic characterization of Salmonella enterica Serovar Telelkebir. Front Microbiol. (2021) 12:704152. 10.3389/fmicb.2021.704152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Elbediwi M, Shi D, Biswas S, Xu X, Yue M. Changing patterns of Salmonella enterica serovar rissen from humans, food animals, and animal-derived foods in China, 1995–2019. Front Microbiol. (2021) 12:2011. 10.3389/fmicb.2021.702909 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hu B, Hou P, Teng L, Miao S, Zhao L, Ji S, et al. Genomic investigation reveals a community typhoid outbreak caused by contaminated drinking water in China, 2016. Front Med. (2022) 9:448. 10.3389/fmed.2022.753085 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Feasey NA, Dougan G, Kingsley RA, Heyderman RS, Gordon MA. Invasive non-typhoidal Salmonella disease: an emerging and neglected tropical disease in Africa. Lancet. (2012) 379:2489–99. 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61752-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li Y, Kang X, Ed-Dra A, Zhou X, Jia C, Müller A, et al. Genome-based assessment of antimicrobial resistance and virulence potential of isolates of non-pullorum/gallinarum Salmonella serovars recovered from dead poultry in China. Microbiol Spectr. (2022) e0096522. 10.1128/spectrum.00965-22. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xu Y, Zhou X, Jiang Z, Qi Y, Ed-Dra A, Yue M. Antimicrobial resistance profiles and genetic typing of Salmonella serovars from chicken embryos in china. Antibiotics. (2021) 10:1156. 10.3390/antibiotics10101156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Elbediwi M, Tang Y, Shi D, Ramadan H, Xu Y, Xu S, et al. Genomic investigation of antimicrobial-resistant Salmonella enterica isolates from dead chick embryos in China. Front Microbiol. (2021) 12:684400. 10.3389/fmicb.2021.684400 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Paudyal N, Pan H, Elbediwi M, Zhou X, Peng X, Li X, et al. Characterization of Salmonella Dublin isolated from bovine and human hosts. BMC Microbiol. (2019) 19:226. 10.1186/s12866-019-1598-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li Y, Ed-Dra A, Tang B, Kang X, Müller A, Kehrenberg C, et al. Higher tolerance of predominant Salmonella serovars circulating in the antibiotic-free feed farms to environmental stresses. J Hazard Mater. (2022) 438:129476. 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2022.129476 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wu B, Ed-Dra A, Pan H, Dong C, Jia C, Yue M. Genomic investigation of Salmonella isolates recovered from pigs slaughtering process in Hangzhou, China. Front Microbiol. (2021) 12:704636. 10.3389/fmicb.2021.704636 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xu X, Biswas S, Gu G, Elbediwi M, Li Y, Yue M. Characterization of multidrug resistance patterns of emerging Salmonella enterica serovar Rissen along the food chain in China. Antibiotics. (2020) 9:1–16. 10.3390/antibiotics9100660 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu Q, Chen W, Elbediwi M, Pan H, Wang L, Zhou C, et al. Characterization of Salmonella Resistome and plasmidome in pork production system in Jiangsu, China. Front Vet Sci. (2020) 7:617. 10.3389/fvets.2020.00617 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jiang Z, Anwar TM, Peng X, Biswas S, Elbediwi M, Li Y, et al. Prevalence and antimicrobial resistance of Salmonella recovered from pig-borne food products in Henan, China. Food Control. (2021) 121:107535. 10.1016/j.foodcont.2020.107535 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Elbediwi M, Pan H, Jiang Z, Biswas S, Li Y, Yue M. Genomic Characterization of mcr-1-carrying Salmonella enterica Serovar 4,[5],12:i:- ST 34 clone isolated from pigs in China. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. (2020) 8:663. 10.3389/fbioe.2020.00663 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jiang Z, Paudyal N, Xu Y, Deng T, Li F, Pan H, et al. Antibiotic resistance profiles of Salmonella recovered from finishing pigs and slaughter facilities in Henan, China. Front Microbiol. (2019) 10:1513. 10.3389/fmicb.2019.01513 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang X, Biswas S, Paudyal N, Pan H, Li X, Fang W, et al. Antibiotic resistance in Salmonella typhimurium isolates recovered from the food chain through national antimicrobial resistance monitoring system between 1996 and 2016. Front Microbiol. (2019) 10:985. 10.3389/fmicb.2019.00985 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pan H, Paudyal N, Li X, Fang W, Yue M. Multiple food-animal-borne route in transmission of antibiotic-resistant Salmonella newport to humans. Front Microbiol. (2018) 9:23. 10.3389/fmicb.2018.00023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Elbediwi M, Li Y, Paudyal N, Pan H, Li X, Xie S, et al. Global burden of colistin-resistant bacteria: Mobilized colistin resistance genes study (1980–2018). Microorganisms. (2019) 7:461. 10.3390/microorganisms7100461 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Klemm EJ, Shakoor S, Page AJ, Qamar FN, Judge K, Saeed DK, et al. Emergence of an extensively drug-resistant Salmonella enterica serovar typhi clone harboring a promiscuous plasmid encoding resistance to fluoroquinolones and third-generation cephalosporins. mBio. (2018) 9:e00105–18. 10.1128/mBio.00105-18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ed-Dra A, Filali FR, Karraouan B, El Allaoui A, Aboulkacem A, Bouchrif B. Prevalence, molecular and antimicrobial resistance of Salmonella isolated from sausages in Meknes, Morocco. Microb Pathog. (2017) 105:340–5. 10.1016/j.micpath.2017.02.042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Collignon P. Superbugs in food: a severe public health concern. Lancet Infect Dis. (2013) 13:641–3. 10.1016/S1473-3099(13)70141-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yu H, Elbediwi M, Zhou X, Shuai H, Lou X, Wang H, et al. Epidemiological and genomic characterization of campylobacter jejuni isolates from a foodborne outbreak at Hangzhou, China. Int J Mol Sci. (2020) 21:3001. 10.3390/ijms21083001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Peng X, Ed-Dra A, Yue M. Whole genome sequencing for the risk assessment of probiotic lactic acid bacteria. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. (2022) 1–19. 10.1080/10408398.2022.2087174. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Köser CU, Ellington MJ, Peacock SJ. Whole-genome sequencing to control antimicrobial resistance. Trends Genet. (2014) 30:401–7. 10.1016/j.tig.2014.07.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McDermott PF, Tyson GH, Kabera C, Chen Y, Li C, Folster JP, et al. Whole-genome sequencing for detecting antimicrobial resistance in nontyphoidal Salmonella. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. (2016) 60:5515–20. 10.1128/AAC.01030-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhu C, Yue M, Rankin S, Weill FX, Frey J, Schifferli DM. One-step identification of five prominent chicken Salmonella serovars and biotypes. J Clin Microbiol. (2015) 53:3881–3. 10.1128/JCM.01976-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Grimont P, Weill F-X. Antigenic Formulae of the Salmonella servovars. 9th Ed. Paris: Institut Pasteur; (2007). [Google Scholar]

- 41.CLSI . Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. 30th Ed. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI). (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 42.EUCAST (European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing) . Recommendations 2017: Eur Comm Antimicrob Susceptibility Test. (2017). Available online at: www.sfm-microbiologie.org (accessed July 18, 2020).

- 43.Magiorakos AP, Srinivasan A, Carey RB, Carmeli Y, Falagas ME, Giske CG, et al. Multidrug-resistant, extensively drug-resistant and pandrug-resistant bacteria: an international expert proposal for interim standard definitions for acquired resistance. Clin Microbiol Infect. (2012) 18:268–81. 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2011.03570.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bolger AM, Lohse M, Usadel B. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics. (2014) 30:2114–20. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu170 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bankevich A, Nurk S, Antipov D, Gurevich AA, Dvorkin M, Kulikov AS, et al. SPAdes: a new genome assembly algorithm and its applications to single-cell sequencing. J Comput Biol. (2012) 19:455–77. 10.1089/cmb.2012.0021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Seemann T. Prokka: rapid prokaryotic genome annotation. Bioinformatics. (2014) 30:2068–9. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Liu B, Zheng D, Jin Q, Chen L, Yang J. VFDB 2019: a comparative pathogenomic platform with an interactive web interface. Nucleic Acids Res. (2019) 47:D687–92. 10.1093/nar/gky1080 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Liu YY, Lin JW, Chen CC. Cano-wgMLST_BacCompare: a bacterial genome analysis platform for epidemiological investigation and comparative genomic analysis. Front Microbiol. (2019) 10:1687. 10.3389/fmicb.2019.01687 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Paudyal N, Pan H, Liao X, Zhang X, Li X, Fang W, et al. Meta-analysis of major foodborne pathogens in Chinese food commodities between 2006 and 2016. Foodborne Pathog Dis. (2018) 15:187–97. 10.1089/fpd.2017.2417 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yue M, Rankin SC, Blanchet RT, Nulton JD, Edwards RA, Schifferli DM. Diversification of the Salmonella Fimbriae: a model of macro- and microevolution. PLoS One. (2012) 7:e38596. 10.1371/journal.pone.0038596 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yue M, Han X, De Masi L, Zhu C, Ma X, Zhang J, et al. Allelic variation contributes to bacterial host specificity. Nat Commun. (2015) 6:1–11. 10.1038/ncomms9754 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.EFSA . The European union one health 2019 zoonoses report. EFSA J. (2021) 19:e06406. 10.2903/j.efsa.2021.6406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Medalla F, Gu W, Friedman CR, Judd M, Folster J, Griffin PM, et al. Increased incidence of antimicrobial-resistant nontyphoidal Salmonella infections, United States, 2004–2016. Emerg Infect Dis. (2021) 27:1662–72. 10.3201/eid2706.204486 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.CDC . National Enteric Disease Surveillance: Salmonella Annual Report, 2016. (2018). Available online at: https://www.census.gov/geo/pdfs/maps-data/maps/ (accessed April 24, 2021).

- 55.Pijnacker R, Dallman TJ, Tijsma ASL, Hawkins G, Larkin L, Kotila SM, et al. An international outbreak of Salmonella enterica serotype enteritidis linked to eggs from Poland: a microbiological and epidemiological study. Lancet Infect Dis. (2019) 19:778–86. 10.1016/S1473-3099(19)30047-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Li S, He Y, Mann DA, Deng X. Global spread of Salmonella Enteritidis via centralized sourcing and international trade of poultry breeding stocks. Nat Commun. (2021) 12:1–12. 10.1038/s41467-021-25319-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ke Y, Lu W, Liu W, Zhu P, Chen Q, Zhu Z. Non-typhoidal Salmonella infections among children in a tertiary hospital in ningbo, Zhejiang, China, 2012–2019. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. (2020) 14:1–18. 10.1371/journal.pntd.0008732 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wu LJ, Luo Y, Shi GL, Li ZY. Prevalence, clinical characteristics and changes of antibiotic resistance in children with nontyphoidal Salmonella infections from 2009–2018 in Chongqing, China. Infect Drug Resist. (2021) 14:1403–13. 10.2147/IDR.S301318 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gong B, Li H, Feng Y, Zeng S, Zhuo Z, Luo J, et al. Prevalence, serotype distribution and antimicrobial resistance of non-typhoidal Salmonella in hospitalized patients in Conghua District of Guangzhou, China. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. (2022) 12:54. 10.3389/fcimb.2022.805384 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Duong VT, The HC, Nhu TDH, Tuyen HT, Campbell JI, Van Minh P. Genomic serotyping, clinical manifestations, and antimicrobial resistance of nontyphoidal Salmonella gastroenteritis in hospitalized children in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam. J Clin Microbiol. (2020) 58:e01465-20 10.1128/JCM.01465-20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sinwat N, Angkittitrakul S, Coulson KF, Pilapil FMIR, Meunsene D, Chuanchuen R. High prevalence and molecular characteristics of multidrug-resistant Salmonella in pigs, pork and humans in Thailand and Laos provinces. J Med Microbiol. (2016) 65:1182–93. 10.1099/jmm.0.000339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Teng L, Liao S, Zhou X, Jia C, Feng M, Pan H, et al. Prevalence and genomic investigation of multidrug-resistant Salmonella isolates from companion animals in Hangzhou, China. Antibiot. (2022) 11:625. 10.3390/antibiotics11050625 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Alekshun MN, Levy SB. Molecular mechanisms of antibacterial multidrug resistance. Cell. (2007) 128:1037–50. 10.1016/j.cell.2007.03.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ramirez MS, Tolmasky ME. Aminoglycoside modifying enzymes. Drug Resist Updat. (2010) 13:151–71. 10.1016/j.drup.2010.08.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Eguale T, Birungi J, Asrat D, Njahira MN, Njuguna J, Gebreyes WA, et al. Genetic markers associated with resistance to beta-lactam and quinolone antimicrobials in non-typhoidal Salmonella isolates from humans and animals in central Ethiopia. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. (2017) 6:1–10. 10.1186/s13756-017-0171-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Roberts MC, Schwarz S. Tetracycline and Chloramphenicol Resistance Mechanisms. In: Antimicrobial Drug Resistance. Cham: Springer; (2017). p. 231–43. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Vidovic S, An R, Rendahl A. Molecular and physiological characterization of fluoroquinolone-highly resistant Salmonella enteritidis strains. Front Microbiol. (2019) 10:729. 10.3389/fmicb.2019.00729 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wu S-y, Wang L-d, Li J-l, Xu G-m, He M-l, Li Y-y, et al. Salmonella spv locus suppresses host innate immune responses to bacterial infection. Fish Shellfish Immunol. (2016) 58:387–96. 10.1016/j.fsi.2016.09.042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Guiney DG, Fierer J. The role of the spv genes in Salmonella pathogenesis. Front Microbiol. (2011) 2:129. 10.3389/fmicb.2011.00129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ledeboer NA, Frye JG, McClelland M, Jones BD. Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium requires the Lpf, Pef, and tafi fimbriae for biofilm formation on HEp-2 tissue culture cells and chicken intestinal epithelium. Infect Immun. (2006) 74:3156–69. 10.1128/IAI.01428-05 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Futoma-Kołoch B, Bugla-Płoskońska G, Dudek B, Dorotkiewicz-Jach A, Drulis-Kawa Z, Gamian A. Outer membrane proteins of Salmonella as potential markers of resistance to serum, antibiotics and biocides. Curr Med Chem. (2018) 26:1960–78. 10.2174/0929867325666181031130851 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kim B, Richards SM, Gunn JS, Slauch JM. Protecting against antimicrobial effectors in the phagosome allows SodCII to contribute to virulence in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. J Bacteriol. (2010) 192:2140–9. 10.1128/JB.00016-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Sly LM, Guiney DG, Reiner NE. Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium periplasmic superoxide dismutases SodCI and SodCII are required for protection against the phagocyte oxidative burst. Infect Immun. (2002) 70:5312–5. 10.1128/IAI.70.9.5312-5315.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Rychlik I, Gregorova D, Hradecka H. Distribution and function of plasmids in Salmonella enterica. Vet Microbiol. (2006) 112:1–10. 10.1016/j.vetmic.2005.10.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kudirkiene E, Andoh LA, Ahmed S, Herrero-Fresno A, Dalsgaard A, Obiri-Danso K, et al. The use of a combined bioinformatics approach to locate antibiotic resistance genes on plasmids from whole genome sequences of Salmonella enterica serovars from humans in Ghana. Front Microbiol. (2018) 9:1010. 10.3389/fmicb.2018.01010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Zhao Q, Feng Y, Zong Z. An integrated IncFIB/IncFII plasmid confers hypervirulence and its fitness cost and stability. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. (2022) 41:681–4. 10.1007/s10096-022-04407-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genbank/, PRJNA844576.