Abstract

Inborn errors of immunity (IEIs) are a group of more than 450 monogenic disorders that impair immune development and function. A subset of IEIs blend increased susceptibility to infection, autoimmunity, and malignancy and are known collectively as primary immune regulatory disorders (PIRDs). While many aspects of immune function are altered in PIRDs, one key impact is on T-cell function. By their nature, PIRDs provide unique insights into human T-cell signaling; alterations in individual signaling molecules tune downstream signaling pathways and effector function. Quantifying T-cell dysfunction in PIRDs and the underlying causative mechanisms is critical to identifying existing therapies and potential novel therapeutic targets to treat our rare patients and gain deeper insight into the basic mechanisms of T-cell function. Though there are many types of T-cell dysfunction, here we will focus on T-cell exhaustion, a key pathophysiological state. Exhaustion has been described in both human and mouse models of disease, where the chronic presence of antigen and inflammation (e.g., chronic infection or malignancy) induces a state of altered immune profile, transcriptional and epigenetic states, as well as impaired T-cell function. Since a subset of PIRDs amplify T-cell receptor (TCR) signaling and/or inflammatory cytokine signaling cascades, it is possible that they could induce T-cell exhaustion by genetically mimicking chronic infection. Here, we review the fundamentals of T-cell exhaustion and its possible role in IEIs in which genetic mutations mimic prolonged or amplified T-cell receptor and/or cytokine signaling. Given the potential insight from the many forms of PIRDs in understanding T-cell function and the challenges in obtaining primary cells from these rare disorders, we also discuss advances in CRISPR-Cas9 genome-editing technologies and potential applications to edit healthy donor T cells that could facilitate further study of mechanisms of immune dysfunctions in PIRDs. Editing T cells to match PIRD patient genetic variants will allow investigations into the mechanisms underpinning states of dysregulated T-cell function, including T-cell exhaustion.

Keywords: inborn error of immunity (IEI), human immunology, CRISPR (clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeat)/Cas9 (CRISPR associated protein 9)-mediated genome editing, t cell exhaustion, precision medicine

Introduction

Inborn errors of immunity (IEIs) are a group of heterogeneous monogenic diseases that disrupt immune function (1–3). The clinical features of IEIs are diverse and include recurrent infections and immune dysregulation, which can present as autoinflammation, autoimmunity, lymphoproliferation, cancer, and/or atopy (1, 4, 5). Flow cytometry and clinical genetic testing (e.g., single gene sequencing, gene panels, whole exome, and genome sequencing) have emerged as powerful tools that aid in the identification and diagnosis of monogenic IEIs (6–9). However, there is significant complexity in the diagnosis of IEIs via clinical genetic testing. While genetic testing may yield known pathogenic variants in genes known to cause IEIs, many more patients may have negative results, or testing may uncover variants of unknown significance (VUS), requiring further evaluation for interpretation. In the latter case, complexity comes from the fact that many variants in any given gene may not have any direct impact on protein function, and those that do impact protein function can amplify or reduce a protein’s presence and/or function (referred to as a gain of function (GOF) or loss of function (LOF), respectively) (2, 3, 10). The clinical phenotypes (in GOF vs. LOF) may be more similar than one would expect, so clinical phenotype may not be sufficient for a determination. To understand whether a novel genetic variant in a patient is causative, pathogenic variant requires a context of deeper study of key, interconnected signaling pathways at baseline in healthy controls and comparison to alterations in IEI patients. This context allows clarity when focusing on the impact of a specific genetic variant in an individual patient, from a clinical perspective. More broadly for the field, by studying samples from IEI patients with pathogenic variants in key signaling molecules, we can learn both about those rare resulting IEIs (and help us diagnose novel IEIs) and about how the fundamental pathways of the immune system can be mistuned, either overly amplified or inappropriately muted. Therefore, from the perspective of human immunology research, the opportunity to study these rare patients allows us to work toward both optimizing diagnosis and targeted therapeutics and gaining a deeper understanding of how the impacted immune pathways interact.

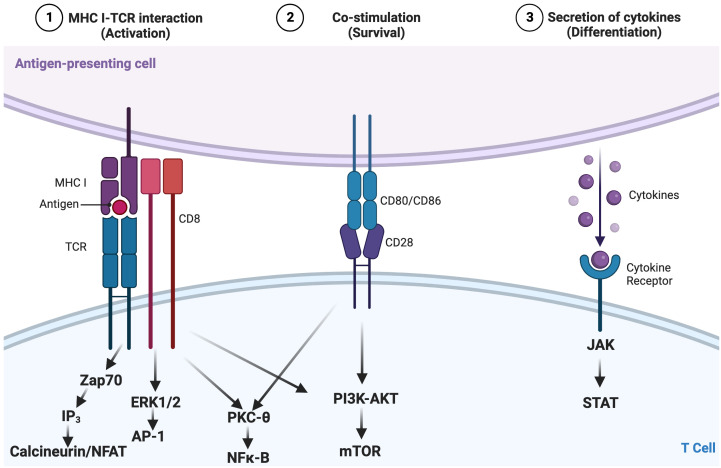

T cells are a key component of the cellular adaptive immune system and contribute to responses against pathogens and tumors (11). How T cells become activated, differentiate, and ultimately exert their effector functions is governed by various signaling pathways. These pathways include activation via the T-cell receptor (TCR; signal 1; Figure 1 ) binding of cell surface costimulatory receptors to their ligands, providing additional signals required to enhance the magnitude of T-cell activation and prevent anergy (signal 2; Figure 1 ), and soluble mediators, including cytokines (signal 3; Figure 1 ), which impact the differentiation, efficacy, and durability of the T-cell response ( Figure 1 ) (12–15). Regulated T-cell responses ensure effective immunity while preserving immune tolerance (16–18). Altered TCR signaling may impact primary responses to infection and malignancy or foster autoimmunity by hyperactivating autoreactive T cells and impairing mechanisms of tolerance [e.g., central tolerance, anergy, activation-induced cell death, and regulatory T cells (Tregs)] (13, 19–23). Therefore, changes in signaling can lead to altered states of activity and cellular fates and even impact the survival of the host.

Figure 1.

Canonical three-signal activation model for T cells. Activation is dependent on integration of three signals: 1) recognition by the T-cell receptor (TCR) of an antigen presented as a peptide by the major histocompatibility complex (pMHC) on antigen-presenting cells (APCs); 2) costimulation, which lowers the stimulation threshold of naïve T cells, prevents anergy, and enhances cytokine production; and 3) cytokine signaling along the JAK-STAT pathway, which amplifies the clonal expansion, survival, and differentiation of T cells. These converging cellular signaling cascades influence the activation and differentiation status of T lymphocytes, in this case, CD8+ T cells. Adapted from “Three Signals Required for T cell Activation”, by BioRender.com (2022). Retrieved from https://app.biorender.com/biorender-templates/t-5f7c7b883b9a9000abcf98e4-three-signals-required-for-t-cell-activation.

Within IEIs, primary immune regulatory disorders (PIRDs) alter immune signaling pathways and result in immune dysregulation (5, 24). Given the role that T cells play in establishing and maintaining immune responses, homeostasis, and memory, it is important to study the factors and changes that impair T-cell function. There are many impacts on both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in PIRDs, but we are fascinated by the shared manifestation in many PIRDs of increased respiratory viral infections and herpes family viral infections. Therefore, here, we will focus on CD8+ T-cell dysfunction, specifically T-cell exhaustion, which could contribute to susceptibility to these types of infections in IEIs (25–28). We will review the fundamentals of T-cell exhaustion, evidence of exhaustion in IEIs, and strategies that will allow a more complete evaluation of the role of T-cell exhaustion in IEIs.

Relationship between inborn errors of immunity and T-cell exhaustion

What is T-cell exhaustion?

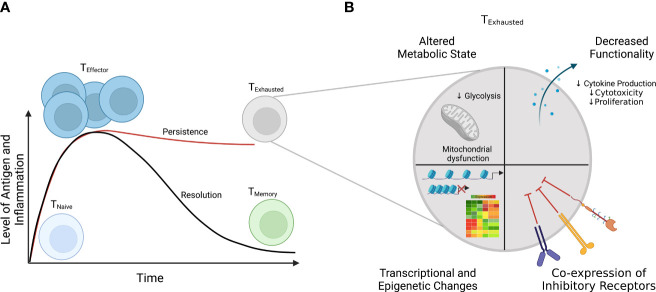

Upon encountering antigen presented by antigen-presenting cells and inflammatory cues (e.g., cytokines), naïve CD8+ T cells are rewired to activate, rapidly proliferate, and become effectors ( Figure 2A ) (29). When the pathogen or antigen is cleared, a minority of these effector cells survive and become memory cells, while the vast majority die via apoptosis (29). However, when antigen and inflammation persist, as in the setting of chronic viral infection or malignancy, T cells can become exhausted ( Figure 2 ) (25–27). The amount or the length of exposure to these signals has been shown to connect to the extent of T-cell exhaustion (30). Indeed, in some settings, cessation of signaling enables cells to reverse/reduce the extent of exhaustion and regain some aspects of functionality (30, 31). Though antigen stimulation is widely recognized as a driver of exhaustion, inflammatory signals (e.g., cytokines) and non-immune signals, such as hypoxia, also can contribute to the development of exhaustion (32, 33). Among its many characteristics, T-cell exhaustion involves an altered immune phenotype, including increased and sustained expression of multiple inhibitory receptors, which can include increased levels of PD-1, CTLA-4, LAG-3, and TIM-3 (27, 34). While alterations in immune phenotype can imply a functional impact, these changes are not sufficient to define T-cell exhaustion, as some of these makers are also expressed during the course of normal T-cell activation; therefore, functional changes must also be evaluated. Functional assays are central to testing suspected T-cell exhaustion, including the loss of effector cytokines such as IL-2, TNF-α, and IFN-γ; impaired cytotoxicity; and decreased proliferation (35, 36). Additionally, T-cell exhaustion is characterized by dysregulated transcriptional and epigenetic circuitry (e.g., increased expression of TOX) and alterations in metabolic state, including decreased mitochondrial function and defects in glycolysis ( Figure 2B ) (32, 37–45).

Figure 2.

Differential T-cell responses to short-term (acute) and long-term (chronic) infections. (A) In acute infections (solid black line), T-cell response spikes are marked by acquisition of effector function (e.g., cytokine production) and upregulation of activation markers and clonal expansion. When an infection or antigen is cleared, a small subset of effector T cells differentiate into memory cells, poised to reactivate upon re-infection, while most cells die. However, if the antigen level or inflammation persists as in the case during chronic infections, T cells develop into a distinct subset, termed “exhausted” T cells (solid red line). (B) Among the characteristics that define exhausted T cells are 1) coordinate expression of multiple immunoregulatory receptors, 2) decreased effector function, 3) altered metabolic function, and 4) altered transcriptional and epigenetic status.

However, T-cell exhaustion is by no means the only state of T-cell dysfunction. T-cell senescence, often mentioned as a comparator to T-cell exhaustion, is an entirely separate process. The definitions of senescence and exhaustion can seem unclear in the literature, because both states share several phenotypic and functional characteristics, though they are fundamentally different (46). Hallmarks of senescent T cells include changes in phenotype (e.g., upregulation of CD45RA, CD57, and KLRG1 and absence of CD28), shortened telomeres, and cell cycle arrest (46–50). While exhausted and senescent CD8+ T cells have defects in proliferative potential, senescent CD8+ T cells still retain some effector functions, including the ability to produce high levels of both pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines compared to hypofunctional exhausted CD8+ T cells (46, 51, 52). In addition, senescence is not currently understood to be recoverable. Senescence has been observed in various IEIs, including activated phosphoinositide 3-kinase δ syndrome (APDS), chronic granulomatous disease (CGD), and tripeptidyl peptidase II deficiency (53–57). While understanding the underlying mechanisms that lead to the development of dysfunctional T-cell states such as exhaustion and senescence are important, here we will focus on T-cell exhaustion, in part due to the potential for recovering some effector functions in this cell state.

Aberrant signaling networks in primary immune regulatory disorders

While each IEI is a unique genetic disease, variants in different genes can converge in multiple IEIs with similar impacts on shared signaling pathways. This could potentially yield shared dysfunctional states and similar clinical phenotypes (58). For example, within IEIs, this could be anticipated to take place in PIRDs that amplify TCR signaling and/or inflammatory cytokine signaling. As previously stated, multiple coordinated signals are required to activate a T cell and control its function ( Figure 1 ) (12). Therefore, certain PIRDs that amplify signaling downstream of the TCR can thus cause T-cell hyperactivation. We, as well as others, have found that this can lead to exhaustion-like phenotypes (49, 53, 59, 60). For example, assessment of a cohort of common variable immunodeficiency (CVID) patients, including some with monogenic PIRDs, through flow and mass cytometry has revealed hallmarks of CD8+ T-cell exhaustion including co-expression of inhibitory receptors, loss of markers such as CD127 and CD28, and expression of transcriptional and epigenetic regulators such as TOX (61).

Now, we will focus on how T-cell hyperactivation in PIRDs could theoretically happen in two broad ways—blocking negative signals or amplifying positive signals.

First, there could be a decrease in inhibitory signaling; here we will review some examples. The first three examples are closely related: autosomal dominant loss of function mutations in CTLA4 (also known as CTLA-4 haploinsufficiency; CTLA-4+/−), LRBA deficiency, and DEF6 deficiency (62–65). CTLA-4 is expressed by T cells (e.g., Tregs and activated cells) and competes with CD28 for ligands, CD80/CD86, which are expressed on antigen-presenting cells (APCs) (66–69). In addition, CTLA-4 can remove and degrade CD80/CD86 from the surface of APCs through a process called trans-endocytosis, blocking costimulation to T cells (70). The balance of positive and negative signals exerted by CD28 and CTLA-4 is crucial for regulating T-cell responses (66, 67, 71). Immunologic features of CTLA-4+/− include, but are not limited to, a reduction in the number of CD4+ T cells, alterations in the expression of inhibitory receptors and activation markers on CD8+ T cells (e.g., upregulated expression of PD-1 and HLA-DR), alterations in the B-cell compartment (e.g., decreased counts of total B cells and switched memory B cells and increased frequency of CD21low B cells), as well as increased apoptosis of both T and B cells in vitro (60, 72, 73). LRBA plays a role in the recycling of CTLA-4 and LRBA deficiency results in a reduction of CTLA-4 levels. DEF6 deficiency affects CTLA-4 cycling dynamics and uptake of CD80, clinically and functionally resembling CTLA-4 haploinsufficiency and LRBA deficiency (62, 64). Similarly related, as PD-1 can act as a negative regulator of T-cell function, loss of PD-1 could result in hyperactive cells. A patient with homozygous LOF in PDCD1 was recently reported with autoimmune manifestations and tuberculosis (TB) (74). Interestingly, while this patient expressed hallmarks consistent with hyperactivation, such as HLA-DR and CD38, the patient’s cells did not produce IFN-γ upon stimulation, including within the CD8+ T-cell population (74). Finally, another example of a monogenic disorder that results in the loss of a negative regulator of T-cell receptor signaling involves the ubiquitination of T-cell receptors and proximal signaling molecules such as TCRζ and MEKK1 (75–77). Mutations in ITCH, which encodes itchy E3 ubiquitin protein ligase, have been described; these patients present with immune dysregulation including multisystem autoimmune disease and immune deficiency (4, 78–81). Thus, each of these IEIs that reduce inhibitory signaling could theoretically cause chronic antigen-like signaling and could thus potentially cause T-cell exhaustion.

Second, there can be increased overall activating signals; here we will review a few examples. Clinically, APDS often presents as a monogenic form of CVID, with a variable phenotype that includes recurrent infections, autoimmunity, lymphadenopathy, and chronic viral infections (e.g., Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) and cytomegalovirus (CMV)) (82–84). APDS is caused by heterozygous mutations in PIK3CD (GOF) or PIK3R1 (LOF); in both cases, there is an amplification of PI3K signaling (49, 53, 85). While PIK3R1 encodes regulatory subunits of PI3K and is more ubiquitously expressed, PIK3CD encodes p110δ and is more restricted to the hematopoietic lineage (86, 87). Signal transduction along the PI3K pathway regulates various aspects of immune cell homeostasis and activity, including the ability of a cell to initiate changes in its metabolism, grow and differentiate, and function. Conversion of the molecule phosphatidylinositol 4,5-biphosphate (PIP2) to phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-triphosphate (PIP3) through phosphorylation by PI3Kδ leads to AKT recruitment and mTOR pathway activation (82, 88). This pathway is negatively regulated by PTEN, which converts PIP3 to PIP2; APDS-like immune dysregulation has been observed in patients with PTEN LOF variants (83, 88–90). Thus, mutations in PIK3CD, PIK3R1, and PTEN result in hyperactivation of the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway, causing amplification of downstream members of the TCR signaling cascade.

Another way of altering activating signals is through amplified inflammatory cytokine signaling through the Janus kinase-signal transducer and activator of transcription (JAK-STAT) pathway. The JAK-STAT pathway and inflammation regulate various aspects of the immune system, including the polarization and function of T cells (91–93). Genetic alterations that lead to persistent or prolonged cytokine signaling such as GOF mutations in STAT1 and STAT3 (STAT1 GOF and STAT3 GOF) have been described in patients with immune dysregulation (94–97). The clinical phenotype of STAT1 GOF is variable and includes autoimmunity, autoinflammation, and increased susceptibility to both chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis (CMC) and viral infections (94, 95). Meanwhile, STAT3 GOF leads to a complex immune dysregulatory picture with multi-organ autoimmunity, lymphoproliferation, and recurrent infections (94, 96–100). Whether genetically amplified or environmentally inflammatory cytokine signaling in human T cells is sufficient to lead to T-cell exhaustion remains unknown.

What is the evidence for T-cell exhaustion in inborn errors of immunity?

While exhaustion has been studied in the context of chronic viral infection and malignancy, evidence consistent with exhaustion has been found in various IEIs ( Table 1 ), ranging from those altering PI3K and NF-κB signaling to other key molecules involved in T-cell activation and inhibition. In APDS, there is an elevated expression of PD-1 on CD8+ T cells (59). Because T-cell exhaustion cannot be defined by one marker alone, expression of additional inhibitory molecules, including CD160 and CD244, has also been interrogated; these markers have been shown to be increased in patients (56, 59). Increased susceptibility to apoptosis, which is associated with T-cell exhaustion, has also been observed in APDS (57, 82, 101, 102, 107, 108). In one study, decreased cytotoxicity of EBV-specific CD8+ T-cell lines against lymphoblastoid cell lines (LCLs) was observed (57). In another study, functional testing of CD8+ T cells from APDS patients demonstrated impaired function (i.e., reduction in IL-2 secretion and proliferation), which improved with rapamycin treatment (53). In vitro, blocking the PD-1/PD-L1 pathway increased the function (proliferation and cytokine production) of EBV-specific CD8+ T cells (59). This suggests the possibility of T-cell exhaustion in APDS, as immune checkpoint blockade improved some aspects of function. Though not the focus of this review, there is also evidence of B-cell immunometabolic dysregulation, with block in progression from transitional to follicular B-cell stage of differentiation secondary to metabolic alterations in APDS (109). These data raise the question of how GOF mutations affecting PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling might affect the various stages of T-cell activation and differentiation and whether this may cause CD8+ T-cell exhaustion.

Table 1.

Summary table of data suggesting T-cell exhaustion in various IEIs.

| Condition | Evaluation of exhaustion | References |

|---|---|---|

| APDS | Immune phenotype: ↑ PD-1, CD160, CD244 Function: ↓ cytotoxicity, IL-2, proliferation Other: ↑ apoptosis Rapamycin treatment: ↑ IL-2, proliferation PD-L1 blockade: ↑ cytokine, proliferation |

Lucas et al. (2014) (53) Cannons et al. (2018) (56) Edwards et al. (2019) (57) Wentink et al. (2018) (59) Angulo et al. (2013) (101) Wentink et al. (2017) (102) |

| Trisomy 21 | Immune phenotype: ↑ PD-1, CD160, CD244 | Peeters et al. (2022) (103) |

| CARD11 GOF | Function: ↓ proliferation | Snow et al. (2012) (104) |

| DOCK8 deficiency | Immune phenotype: ↑ PD-1, CD244 Function: ↓ proliferation, cytokine (IL-2, TNF-α, and IFN-γ), cytotoxic molecules (CD107a, Granzyme A, and Granzyme B) |

Pillay et al. (2019) (105) Randall et al. (2011) (106) |

| PDCD1 deficiency | Immune phenotype: ↑ TIGIT Function: ↓ cytokine (IFN-γ, TNF-α) |

Ogishi et al. (2021) (74) |

| CVID | Immune phenotype: ↑ PD-1, TIGIT, CD244, LAG-3 Transcriptional and epigenetic factors: ↑ TOX, eomes Function: ± cytotoxic and proinflammatory molecules |

Klocperk et al. (2022) (61) |

APDS, activated phosphoinositide 3-kinase δ syndrome; CVID, common variable immunodeficiency; IEIs, inborn errors of immunity.

Upward arrow (↑) means upregulated/increased; Downward arrow (↓) means downregulate/decreased.

In other IEIs, there may be evidence of exhaustion, though this remains to be fully tested, and exact mechanisms have yet to be elucidated. In trisomy 21, while a surface immune phenotype consistent with exhaustion has been identified (e.g., increased PD-1, CD244, and CD160), a functional impact remains to be measured (103). Another pathway in which dysregulation could potentially lead to an exhausted-like picture is the NF-κB family of transcription factors, which regulates various processes, including immune function and inflammatory responses, cell growth, and apoptosis (110). Heterozygous GOF variants in CARD11 result in BENTA (B-cell expansion with NF-kB and T-cell anergy), which increases activity in NF-κB and yields impaired T-cell proliferative responses following CD3/CD28 stimulation, perhaps reflective of an exhausted-like state, though parameters that define exhaustion, such as increased expression of inhibitory receptors, remain to be tested (104, 111). Exhausted-like phenotypes have been observed in DOCK8-deficient patients, including decreased proliferation and cytokine secretion, and increased expression of the molecules PD-1 and 2B4 (105, 106). Decreased IFN-γ production (and trending decrease in TNF-α) has been described in a patient with PDCD1 deficiency; in CD8+ T cells, there was a slight elevation in TIGIT expression within the CD8+ TEM and TEMRA populations (74). Therefore, with possible evidence of an exhausted-like phenotype in various IEIs ( Table 1 ), we must move forward mechanistically to test whether exhaustion-like outcomes are caused by the genetic variant itself in a cell-intrinsic fashion or the result of cell-extrinsic physiological insults including recurrent infections and/or autoimmunity or if both scenarios contribute to this phenotype.

Using CRISPR-Cas9 editing to facilitate further studies of T-cell exhaustion in inborn errors of immunity

With all that remains to be learned, it is necessary to devise strategies to allow the deep study of IEIs caused by these signaling pathways in human cells and test key hypotheses. Given the challenges in obtaining sufficient primary T cells from these rare IEI patients to deeply delve into mechanistic questions, especially from untreated patients, can we develop tools that will result in stable genetic modification of primary cells, or do we need to rely on cell lines and model organisms? We will next consider how gene editing technologies can be leveraged to edit healthy donor T cells to match patient genetic variants to provide the opportunity to study the impact of acute and chronic alterations in these immune pathways, as well as the impacts of modulating those pathways on cell function in vitro.

Gene therapy is a precision approach to treating IEIs. In a subset of IEI disorders including adenosine deaminase deficiency severe combined immune deficiency (ADA-SCID), X-linked SCID (X-SCID), CGD, and Wiskott–Aldrich syndrome, autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) in combination with gene therapy has been evaluated in clinical trials and found to be an effective therapeutic strategy (112–119) Historically, gene therapy involved the introduction of a corrected gene into affected cells, but integration happened randomly and not necessarily at its native site. However, gene editing tools that allow for site-specific editing have recently and rapidly emerged and been developed to overcome the limitations and risks of conventional gene therapy, such as integration at random sites in the genome, which could result in malignancy (120, 121).

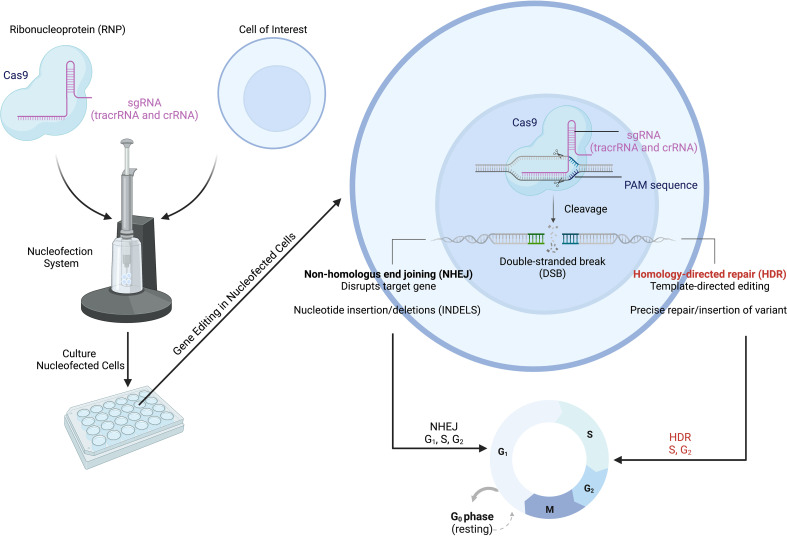

Of the various genome editing tools, CRISPR-Cas9 is one of the most versatile gene editing platforms with the best currently available precision and efficiency (121–123). The CRISPR-Cas9 system involves two main components that make up a ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complex that allows for gene editing: the Cas9 endonuclease and a single-guide RNA (sgRNA) ( Figure 3 ) (124). Within the sgRNA are the CRISPR RNA (crRNA) and trans-activating RNA (tracrRNA) (125–127). The tracrRNA allows Cas9 to bind and form the RNP, while the crRNA targets the endonuclease to a specific location in the genome ( Figure 3 ) (124). Additional specificity is provided by the protospacer adjacent motif (also called the PAM sequence), which needs to be present in order for the Cas nuclease to cut (124). The Cas endonuclease introduces a double-strand break (DSB) at the target site; this DSB then activates DNA repair pathways (126, 128, 129). The DSB can be repaired by one of two mechanisms: non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) or homology-directed repair (HDR). NHEJ is imprecise, leading to the insertion or deletion of nucleotides (i.e., INDELs), which disrupt the gene of interest, while HDR results in nucleotide changes at precise locations in the genome (129–132). For HDR to occur, a donor template containing the new, modified DNA sequence needs to be provided; the sequences around this site on the donor template must be homologous to the target DNA sequence (129–132). While NHEJ can occur during any phase of the cell cycle, HDR only happens during the G2/S cell cycle phases ( Figure 3 ) (128). The HDR pathway allows a wide range of editing: from single nucleotides to the insertion of whole cDNAs of varied lengths (122, 133). Although here we have focused on DNA cleavage-induced editing, alternative techniques using CRISPR-Cas technology exist such as base editing (directly alters the chemical sequence of the DNA without DSBs), prime editing (generates RNA template for gene alteration), and CRISPR interference and activation (for transcriptional control) (134–138). However, many limitations have impeded the full deployment and use of CRISPR-Cas9, especially when aiming to utilize the HDR pathway; we will next discuss some of these limitations.

Figure 3.

CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing to model IEIs/PIRDs. The CRISPR-Cas9 system consists of the Cas9 protein in complex with a targeting gRNA, forming a ribonucleoprotein (RNP). Specificity is conferred through various mechanisms including the sgRNA and presence of the PAM sequence. The Cas9 opens and cuts the targeted sequence on both strands to generate double-strand breaks (DSBs). This activates DNA repair pathways (NHEJ and HDR) in cells and results in modifications at a target locus. The NHEJ pathway can be used for scenarios in which genetic variants result in the loss of expression of an encoded protein, while HDR can be employed for introduction of missense mutations. IEIs, inborn errors of immunity; PIRDs, primary immune regulatory disorders; sgRNA, single-guide RNA; PAM, protospacer adjacent motif; NHEJ, non-homologous end joining; HDR, homology-directed repair. Adapted from “CRISPR/Cas9 Gene Editing”, by BioRender.com (2022). Retrieved from https://app.biorender.com/biorender-templates/t-5f873df466346900a43c6db1-crisprcas9-gene-editing.

To repair an IEI-causing gene variant, various variables need to be considered and optimized. These include a selection of the proper editing system, timing of when editing reagents are introduced, and the quantity of reagents to yield a high degree of editing in cells of interest, while ideally having negligible cytotoxicity and off-target effects. To address this, different strategies have been tested to circumvent some limitations of HDR-based genome-editing strategies, such as its low editing efficiency. For example, as NHEJ is the dominant repair mechanism in cells, small molecules (e.g., those that synchronize cells at the S/G2 stage) or fusion proteins that promote HDR and/or inhibit NHEJ have been developed and used to promote HDR (139–148). Recently, CRISPR-Cas9 editing was used in human hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs) to correct Wiskott–Aldrich syndrome via the HDR pathway (149). These data suggest that targeted gene editing is achievable and can be leveraged in the study and correction of IEIs.

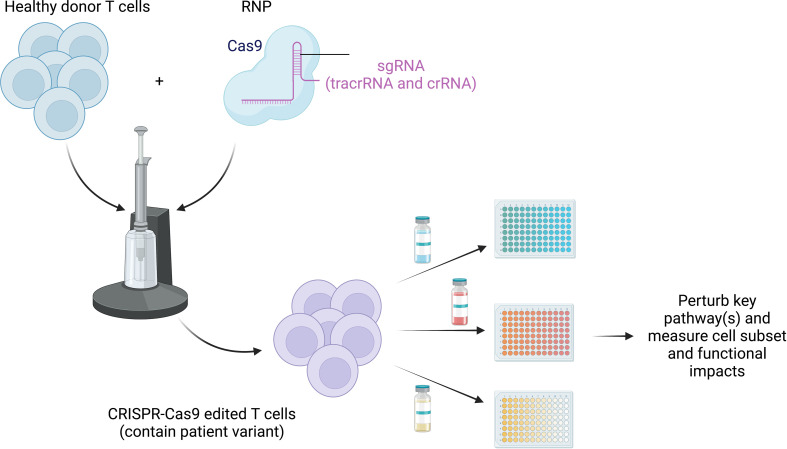

Nevertheless, while gene editing has been used to correct alterations in genes to directly treat IEIs, here we propose introducing relevant patient mutations into healthy donor primary cells of interest to perturb immune signaling pathways to match IEI patient cells (138, 150). This strategy would allow researchers to investigate how these variants dysregulate immune cells and their functions, especially prior to immune-relevant therapy, and increase the number of cells available for mechanistic studies and investigations into the impact of perturbations, especially for rare patients or patients with lymphocytopenia.

As previously discussed, persistent antigen and/or inflammatory signals have been implicated in T-cell exhaustion. However, whether the presence of genetic mimics of chronic activation in T-cell signaling pathways is sufficient to yield T-cell exhaustion has not been proven—IEIs provide novel strategies for assessing the mechanisms of altered cell signaling that can yield this T-cell state. Specifically, missense variants that activate T-cell signaling pathways could be introduced into primary CD8+ T cells using CRISPR-Cas9 mechanisms coupled with repair templates (e.g., double-stranded DNAs (dsDNA) or single-stranded donor oligonucleotides (ssODNs)) (85, 122, 151). However, a balance between increasing the frequency of HDR while only modifying a single allele (as a multitude of IEI are heterozygous) must be achieved. Changing the distance between the cut site and desired mutation location (referred to as “cut-to-mutation distance”) has been shown to affect zygosity (152). In practice, to confirm the successful introduction of a variant (e.g., GOF as an example), sequencing plus an appropriate readout (e.g., phospho-flow cytometry) can be employed. Once the cells are shown to match patient cells genetically, altered immune profile receptors (e.g., upregulated PD-1) and any alterations in T-cell function, including loss of effector function (cytokine production and proliferation), can be assessed (59). For a genetic variant leading to the loss of an encoded protein (and thus absent or decreased expression), the gene of interest can be knocked out to reveal its function in cells of interest such as primary CD8+ T cells and confirmed by flow cytometry or Western blotting and differences in phenotype and function assessed (73). However, it is worth noting that acute changes in signaling may not be sufficient to fully recapitulate the alterations observed in primary patient cells. Therefore, the use of prolonged in vitro cultures, restimulations, and comparison to unedited cells (e.g., cells that received a non-targeting control guide) may be needed to fully dissect the impact of these variants on immune cell phenotype and function.

By harnessing the power of CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing, scientists can directly perturb core signaling pathways in healthy control T cells, matching the disease-causing variants in human genes found in IEIs, to provide additional human cells for mechanistic testing and therapeutic target testing. With the use of this resource, these dysregulated pathways underlying impaired function can theoretically be “retuned” in vitro by blocking and/or amplifying the affected pathways and assessing for improvements in baseline functional deficits ( Figure 4 ). This could be achieved by targeting the altered protein itself, a component of the signaling pathway upstream or downstream, or a related pathway that could be affected by the altered signaling in each IEI. As discussed above in APDS, Wentink et al. demonstrated that blocking the PD-1/PD-L1 signaling pathway improved function in antigen-specific CD8+ T cells, while Lucas et al. used rapamycin to reduce PI3K signaling and improve T-cell function (53, 59). Evidence of “retuning” signaling pathways in IEI has also been described in patients with STAT3 LOF or STAT1 GOF mutations; both conditions share impaired differentiation of Th17 cells, which has been shown to be a result of upregulation of PD-L1 (153–156). Blocking PD-L1 was shown to partially restore both the levels of IL-17A protein and transcript in these patients (156). Together, these data demonstrate that the (dys)functional state of immune cells can be manipulated in PIRDs. However, deepening these types of investigations is very challenging given how rare these diseases are and how challenging it can be to study cells from untreated patients. Therefore, to better understand these key biological and medical questions around T-cell exhaustion in IEI, and to take an expanded approach to test possible novel therapeutics in vitro, the strategy of creating edited healthy control T cells that match patient variants may be transformative.

Figure 4.

Retuning altered pathways to improve function. CRISPR-Cas9 can be used to edit healthy donor primary T cells to match the patient variant to overcome paucity of patient cells, especially those prior to immune-relevant therapy. Testing of treatment options (both preexisting and novel) can be exploited using high-throughput screening strategies to study the impact of blocking and/or stimulating identified dysfunctional pathways. This will allow us to identify and target common states of dysfunction across monogenic diseases.

Conclusion

Primary immune regulatory disorders provide unique insights into the impacts of alterations in individual signaling molecules in T cells on their function. In a subset of PIRDs, there is evidence of T-cell exhaustion, but the contribution of specific altered pathways to the induction or maintenance of cellular fates, such as exhaustion, is not fully understood. Given the challenges in obtaining primary cells from these rare disorders, genome-editing strategies such as CRISPR-Cas9 can be leveraged to edit healthy donor T cells to contain patient genetic variants found in various PIRDs, providing additional opportunities to study these rare disorders and perform mechanistic studies. Identifying the targetable cellular fates induced by causative gene variants in IEI and potentially malleable, relevant pathways (e.g., PD-1 blockade) in IEI will allow us to evaluate the impact and best strategies for retuning pathways in IEI patients in conjunction with high-throughput screening strategies, providing potential novel therapeutic agents. These perturbation studies aimed at restoring function can be optimized in CRISPR-Cas9 edited cells and then confirmed in primary cells from patients. CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing could thus expedite our understanding of signaling pathways and mechanisms of T-cell dysfunction in IEIs. Defining shared dysfunctional states across rare IEIs (or other rare diseases), using gene editing in healthy control human cells to match patient variants, and identifying strategies to retune dysfunctional states may lead to improvements in patient treatment. Additionally, these strategies may increase our understanding of basic immunology and immune dysregulation processes in these rare genetic diseases and other more common diseases, including autoimmunity, chronic infection, and chronic inflammatory disorders.

Author contributions

SEH and JSC planned the manuscript together, JSC drafted it and SEH and JSC both edited it. All figures created with BioRender.com. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

JSC: University of Pennsylvania Presidential Fellow, HHMI Gilliam Fellow; SEH: National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) K08AI135091, Burroughs Wellcome Fund CAMS. Faculty Development Award.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest. All figures created with BioRender.com.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

- 1. Delmonte OM, Castagnoli R, Calzoni E, Notarangelo LD. Inborn errors of immunity with immune dysregulation: From bench to bedside. Front Pediatr (2019) 7:353. doi: 10.3389/fped.2019.00353 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Tangye SG, Al-Herz W, Bousfiha A, Chatila T, Cunningham-Rundles C, Etzioni A, et al. Human inborn errors of immunity: 2019 update on the classification from the international union of immunological societies expert committee. J Clin Immunol (2020) 40:24–64. doi: 10.1007/s10875-019-00737-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bucciol G, Meyts I. Recent advances in primary immunodeficiency: from molecular diagnosis to treatment. F1000Res (2020) 9:1122–40. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.21553.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Sogkas G, Atschekzei F, Adriawan IR, Dubrowinskaja N, Witte T, Schmidt RE, et al. Cellular and molecular mechanisms breaking immune tolerance in inborn errors of immunity. Cell Mol Immunol (2021) 18:1122–40. doi: 10.1038/s41423-020-00626-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Chan AY, Leiding JW, Liu X, Logan BR, Burroughs LM, Allenspach EJ, et al. Hematopoietic cell transplantation in patients with primary immune regulatory disorders (PIRD): A primary immune deficiency treatment consortium (PIDTC) survey. Front Immunol (2020) 11. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.00239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kalina T, Abraham RS, Rizzi M, van der Burg M. Editorial: Application of cytometry in primary immunodeficiencies. Front Immunol (2020) 11. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.00463 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ma CS, Tangye SG. Flow cytometric-based analysis of defects in lymphocyte differentiation and function due to inborn errors of immunity. Front Immunol (2019) 10:2108. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.02108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Notarangelo LD, Bacchetta R, Casanova JL, Su HC. Human inborn errors of immunity: an expanding universe. Sci Immunol (2020) 5:eabb1662. doi: 10.1126/sciimmunol.abb1662 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Meyts I, Bosch B, Bolze A, Boisson B, Itan Y, Belkadi A, et al. Exome and genome sequencing for inborn errors of immunity. J Allergy Clin Immunol (2016) 138:957–69. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2016.08.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Rey-Jurado E, Poli MC. Functional genetics in inborn errors of immunity. Future Rare Dis (2021) 1:FRD11. doi: 10.2217/frd-2020-0003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kumar BV, Connors T, Farber DL. Human T cell development, localization, and function throughout life. Immunity (2018) 48:202–13. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2018.01.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Smith-Garvin JE, Koretzky GA, Jordan MS. T Cell activation. Annu Rev Immunol (2009) 27:591–619. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.021908.132706 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hwang J-R, Byeon Y, Kim D, Park S-G. Recent insights of T cell receptor-mediated signaling pathways for T cell activation and development. Exp Mol Med (2020) 52:750–61. doi: 10.1038/s12276-020-0435-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Saleiro D, Platanias LC. Intersection of mTOR and STAT signaling in immunity. Trends Immunol (2015) 36:21–9. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2014.10.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hervas-Stubbs S, Perez-Gracia JL, Rouzaut A, Sanmamed MF, Le Bon A, Melero I, et al. Direct effects of type I interferons on cells of the immune system. Clin Cancer Res (2011) 17:2619–27. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-1114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Enouz S, Carrié L, Merkler D, Bevan MJ, Zehn D. Autoreactive T cells bypass negative selection and respond to self-antigen stimulation during infection. J Exp Med (2012) 209:1769–79. doi: 10.1084/jem.20120905 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Palmer E. Negative selection — clearing out the bad apples from the T-cell repertoire. Nat Rev Immunol (2003) 3:383–91. doi: 10.1038/nri1085 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Klein L, Kyewski B, Allen PM, Hogquist KA. Positive and negative selection of the T cell repertoire: what thymocytes see and don’t see. Nat Rev Immunol (2014) 14:377–91. doi: 10.1038/nri3667 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Shah K, Al-Haidari A, Sun J, Kazi JU. T Cell receptor (TCR) signaling in health and disease. Sig Transduct Target Ther (2021) 6:1–26. doi: 10.1038/s41392-021-00823-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Smith TRF, Verdeil G, Marquardt K, Sherman LA. Contribution of TCR signaling strength to CD8+ T cell peripheral tolerance mechanisms. J Immunol (2014) 193:3409–16. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1401194 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Xing Y, Hogquist KA. T-Cell tolerance: Central and peripheral. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol (2012) 4:a006957. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a006957 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Redmond WL, Sherman LA. Peripheral tolerance of CD8 T lymphocytes. Immunity (2005) 22:275–84. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.01.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Fife BT, Bluestone JA. Control of peripheral T-cell tolerance and autoimmunity via the CTLA-4 and PD-1 pathways. Immunol Rev (2008) 224:166–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2008.00662.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Chan AY, Torgerson TR. PIRD: Primary immune regulatory disorders, a growing universe of immune dysregulation. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol (2020) 20:582–90. doi: 10.1097/ACI.0000000000000689 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Wherry EJ, Ha SJ, Kaech SM, Haining WN, Sarkar S, Kalia V, et al. Molecular signature of CD8+ T cell exhaustion during chronic viral infection. Immunity (2007) 27:670–84. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.09.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. McLane LM, Abdel-Hakeem MS, Wherry EJ. CD8 T cell exhaustion during chronic viral infection and cancer. Annu Rev Immunol (2019) 37:457–95. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-041015-055318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Wherry EJ, Kurachi M. Molecular and cellular insights into T cell exhaustion. Nat Rev Immunol (2015) 15:486–99. doi: 10.1038/nri3862 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Wherry EJ. T Cell exhaustion. Nat Immunol (2011) 12:492–9. doi: 10.1038/ni.2035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Wherry EJ, Ahmed R. Memory CD8 T-cell differentiation during viral infection. JVI (2004) 78:5535–45. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.11.5535-5545.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Weber EW, Parker KR, Sotillo E, Lynn RC, Anbunathan H, Lattin J, et al. Transient rest restores functionality in exhausted CAR-T cells through epigenetic remodeling. Science (2021) 372:eaba1786. doi: 10.1126/science.aba1786 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Abdel-Hakeem MS, Manne S, Beltra JC, Stelekati E, Chen Z, Nzingha K, et al. Epigenetic scarring of exhausted T cells hinders memory differentiation upon eliminating chronic antigenic stimulation. Nat Immunol (2021) 22:1008–19. doi: 10.1038/s41590-021-00975-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Scharping NE, Rivadeneira DB, Menk AV, Vignali PDA, Ford BR, Rittenhouse NL, et al. Mitochondrial stress induced by continuous stimulation under hypoxia rapidly drives T cell exhaustion. Nat Immunol (2021) 22:205–15. doi: 10.1038/s41590-020-00834-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Maurice NJ, Berner J, Taber AK, Zehn D, Prlic M. Inflammatory signals are sufficient to elicit TOX expression in mouse and human CD8+ T cells. JCI Insight (2021) 6:150744. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.150744 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Winkler F, Bengsch B. Use of mass cytometry to profile human T cell exhaustion. Front Immunol (2020) 10. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.03039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Wherry EJ, Blattman JN, Murali-Krishna K, van der Most R, Ahmed R. Viral persistence alters CD8 T-cell immunodominance and tissue distribution and results in distinct stages of functional impairment. JVI (2003) 77:4911–27. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.8.4911-4927.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Fuller MJ, Zajac AJ. Ablation of CD8 and CD4 T cell responses by high viral loads. J Immunol (2003) 170:477–86. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.1.477 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Pauken KE, Sammons MA, Odorizzi PM, Manne S, Godec J, Khan O, et al. Epigenetic stability of exhausted T cells limits durability of reinvigoration by PD-1 blockade. Science (2016) 354:1160–5. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf2807 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Bengsch B, Johnson AL, Kurachi M, Odorizzi PM, Pauken KE, Attanasio J, et al. Bioenergetic insufficiencies due to metabolic alterations regulated by PD-1 are an early driver of CD8+ T cell exhaustion. Immunity (2016) 45:358–73. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2016.07.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Chen Z, Ji Z, Ngiow SF, Manne S, Cai Z, Huang AC, et al. TCF-1-Centered transcriptional network drives an effector versus exhausted CD8 T cell-fate decision. Immunity (2019) 51:840–855.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2019.09.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Angelosanto JM, Blackburn SD, Crawford A, Wherry EJ. Progressive loss of memory T cell potential and commitment to exhaustion during chronic viral infection. J Virol (2012) 86:8161–70. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00889-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Scharping NE, Menk AV, Moreci RS, Whetstone RD, Dadey RE, Watkins SC, et al. The tumor microenvironment represses T cell mitochondrial biogenesis to drive intratumoral T cell metabolic insufficiency and dysfunction. Immunity (2016) 45:374–88. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2016.07.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Khan O, Giles JR, McDonald S, Manne S, Ngiow SF, Patel KP, et al. TOX transcriptionally and epigenetically programs CD8+ T cell exhaustion. Nature (2019) 571:211–8. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1325-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Alfei F, Kanev K, Hofmann M, Wu M, Ghoneim HE, Roelli P, et al. TOX reinforces the phenotype and longevity of exhausted T cells in chronic viral infection. Nature (2019) 571:265–9. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1326-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Scott AC, Dündar F, Zumbo P, Chandran SS, Klebanoff CA, Shakiba M, et al. TOX is a critical regulator of tumour-specific T cell differentiation. Nature (2019) 571:270–4. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1324-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Yao C, Sun HW, Lacey NE, Ji Y, Moseman EA, Shih HY, et al. Single-cell RNA-seq reveals TOX as a key regulator of CD8+ T cell persistence in chronic infection. Nat Immunol (2019) 20:890–901. doi: 10.1038/s41590-019-0403-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Zhao Y, Shao Q, Peng G. Exhaustion and senescence: two crucial dysfunctional states of T cells in the tumor microenvironment. Cell Mol Immunol (2020) 17:27–35. doi: 10.1038/s41423-019-0344-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Akbar AN, Henson SM. Are senescence and exhaustion intertwined or unrelated processes that compromise immunity? Nat Rev Immunol (2011) 11:289–95. doi: 10.1038/nri2959 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Pawelec G. Is there a positive side to T cell exhaustion? Front Immunol (2019) 10. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.00111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Lucas CL, Zhang Y, Venida A, Wang Y, Hughes J, McElwee J, et al. Heterozygous splice mutation in PIK3R1 causes human immunodeficiency with lymphoproliferation due to dominant activation of PI3K. J Exp Med (2014) 211:2537–47. doi: 10.1084/jem.20141759 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Rodriguez IJ, Lalinde Ruiz N, Llano León M, Martínez Enríquez L, Montilla Velásquez MDP, Ortiz Aguirre JP, et al. Immunosenescence study of T cells: A systematic review. Front Immunol (2021) 11. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.604591 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Callender LA, Carroll EC, Beal RWJ, Chambers ES, Nourshargh S, Akbar AN, et al. Human CD8+ EMRA T cells display a senescence-associated secretory phenotype regulated by p38 MAPK. Aging Cell (2018) 17:e12675. doi: 10.1111/acel.12675 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Akbar AN, Henson SM, Lanna A. Senescence of T lymphocytes: Implications for enhancing human immunity. Trends Immunol (2016) 37:866–76. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2016.09.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Lucas CL, Kuehn HS, Zhao F, Niemela JE, Deenick EK, Palendira U, et al. Dominant-activating, germline mutations in phosphoinositide 3-kinase p110δ cause T cell senescence and human immunodeficiency. Nat Immunol (2014) 15:88–97. doi: 10.1038/ni.2771 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Albuquerque AS, Fernandes SM, Tendeiro R, Cheynier R, Lucas M, Silva SL, et al. Major CD4 T-cell depletion and immune senescence in a patient with chronic granulomatous disease. Front Immunol (2017) 8. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.00543 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Stepensky P, Rensing-Ehl A, Gather R, Revel-Vilk S, Fischer U, Nabhani S, et al. Early-onset Evans syndrome, immunodeficiency, and premature immunosenescence associated with tripeptidyl-peptidase II deficiency. Blood (2015) 125:753–61. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-08-593202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Cannons JL, Preite S, Kapnick SM, Uzel G, Schwartzberg PL. Genetic defects in phosphoinositide 3-kinase δ influence CD8+ T cell survival, differentiation, and function. Front Immunol (2018) 9. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.01758 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Edwards ESJ, Bier J, Cole TS, Wong M, Hsu P, Berglund LJ, et al. Activating PIK3CD mutations impair human cytotoxic lymphocyte differentiation and function and EBV immunity. J Allergy Clin Immunol (2019) 143:276–291.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2018.04.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. López-Nevado M, González-Granado LI, Ruiz-García R, Pleguezuelo D, Cabrera-Marante O, Salmón N, et al. Primary immune regulatory disorders with an autoimmune lymphoproliferative syndrome-like phenotype: Immunologic evaluation, early diagnosis and management. Front Immunol (2021) 12. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.671755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Wentink MWJ, Mueller YM, Dalm VASH, Driessen GJ, van Hagen PM, van Montfrans JM, et al. Exhaustion of the CD8+ T cell compartment in patients with mutations in phosphoinositide 3-kinase delta. Front Immunol (2018) 9. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.00446 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Kuehn HS, Ouyang W, Lo B, Deenick EK, Niemela JE, Avery DT, et al. Immune dysregulation in human subjects with heterozygous germline mutations in CTLA4. Science (2014) 345:1623–7. doi: 10.1126/science.1255904 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Klocperk A, Friedmann D, Schlaak AE, Unger S, Parackova Z, Goldacker S, et al. Distinct CD8 T cell populations with differential exhaustion profiles associate with secondary complications in common variable immunodeficiency. J Clin Immunol (2022). doi: 10.1007/s10875-022-01291-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Lo B, Zhang K, Lu W, Zheng L, Zhang Q, Kanellopoulou C, et al. AUTOIMMUNE DISEASE. patients with LRBA deficiency show CTLA4 loss and immune dysregulation responsive to abatacept therapy. Science (2015) 349:436–40. doi: 10.1126/science.aaa1663 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Hao Y, Cook MC. Inborn errors of immunity and their phenocopies: CTLA4 and PD-1. Front Immunol (2022) 12. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.806043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Serwas NK, Hoeger B, Ardy RC, Stulz SV, Sui Z, Memaran N, et al. Human DEF6 deficiency underlies an immunodeficiency syndrome with systemic autoimmunity and aberrant CTLA-4 homeostasis. Nat Commun (2019) 10:3106. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-10812-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Fournier B, Tusseau M, Villard M, Malcus C, Chopin E, Martin E, et al. DEF6 deficiency, a mendelian susceptibility to EBV infection, lymphoma, and autoimmunity. J Allergy Clin Immunol (2021) 147:740–3.e9. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2020.05.052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Freeman GJ, Gribben JG, Boussiotis VA, Ng JW, Restivo VA, Lombard LA, et al. Cloning of B7-2: a CTLA-4 counter-receptor that costimulates human T cell proliferation. Science (1993) 262:909–11. doi: 10.1126/science.7694363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Hathcock KS, Laszlo G, Dickler HB, Bradshaw J, Linsley P, Hodes RJ, et al. Identification of an alternative CTLA-4 ligand costimulatory for T cell activation. Science (1993) 262:905–7. doi: 10.1126/science.7694361 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Buchbinder EI, Desai A. CTLA-4 and PD-1 pathways. Am J Clin Oncol (2016) 39:98–106. doi: 10.1097/COC.0000000000000239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Wei SC, Levine JH, Cogdill AP, Zhao Y, Anang N-AAS, Andrews MC, et al. Distinct cellular mechanisms underlie anti-CTLA-4 and anti-PD-1 checkpoint blockade. Cell (2017) 170:1120–1133.e17. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.07.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Qureshi OS, Zheng Y, Nakamura K, Attridge K, Manzotti C, Schmidt EM, et al. Trans-endocytosis of CD80 and CD86: a molecular basis for the cell-extrinsic function of CTLA-4. Science (2011) 332:600–3. doi: 10.1126/science.1202947 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Eagar TN, Karandikar NJ, Bluestone JA, Miller SD. The role of CTLA-4 in induction and maintenance of peripheral T cell tolerance. Eur J Immunol (2002) 32:972–81. doi: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Schwab C, Gabrysch A, Olbrich P, Patiño V, Warnatz K, Wolff D, et al. Phenotype, penetrance, and treatment of 133 cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen 4-insufficient subjects. J Allergy Clin Immunol (2018) 142:1932–46. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2018.02.055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Abraham RS. How to evaluate for immunodeficiency in patients with autoimmune cytopenias: laboratory evaluation for the diagnosis of inborn errors of immunity associated with immune dysregulation. Hematology (2020) 2020:661–72. doi: 10.1182/hematology.2020000173 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Ogishi M, Yang R, Aytekin C, Langlais D, Bourgey M, Khan T, et al. Inherited PD-1 deficiency underlies tuberculosis and autoimmunity in a child. Nat Med (2021) 27:1646–54. doi: 10.1038/s41591-021-01388-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Venuprasad K, Elly C, Gao M, Salek-Ardakani S, Harada Y, Luo JL, et al. Convergence of itch-induced ubiquitination with MEKK1-JNK signaling in Th2 tolerance and airway inflammation. J Clin Invest (2006) 116:1117–26. doi: 10.1172/JCI26858 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Enzler T, Chang X, Facchinetti V, Melino G, Karin M, Su B, et al. MEKK1 binds HECT E3 ligase itch by its amino-terminal RING motif to regulate Th2 cytokine gene expression. J Immunol (2009) 183:3831–8. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0803412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Huang H, Jeon MS, Liao L, Yang C, Elly C, Yates JR, 3rd, et al. K33-linked polyubiquitination of T cell receptor-zeta regulates proteolysis-independent T cell signaling. Immunity (2010) 33:60–70. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.07.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Lohr NJ, Molleston JP, Strauss KA, Torres-Martinez W, Sherman EA, Squires RH, et al. Human ITCH E3 ubiquitin ligase deficiency causes syndromic multisystem autoimmune disease. Am J Hum Genet (2010) 86:447–53. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2010.01.028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Kleine-Eggebrecht N, Staufner C, Kathemann S, Elgizouli M, Kopajtich R, Prokisch H, et al. Mutation in ITCH gene can cause syndromic multisystem autoimmune disease with acute liver failure. Pediatrics (2019) 143:e20181554. doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-1554 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Moser EK, Oliver PM. Regulation of autoimmune disease by the E3 ubiquitin ligase itch. Cell Immunol (2019) 340:103916. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2019.04.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Patel T, Henrickson SE, Moser EK, Field NS, Maurer K, Dawany N, et al. Immune dysregulation in human ITCH deficiency successfully treated with hematopoietic cell transplantation. J Allergy Clin Immunol: In Pract (2021) 9:2885–2893.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2021.04.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Lucas CL, Chandra A, Nejentsev S, Condliffe AM, Okkenhaug K. PI3Kδ and primary immunodeficiencies. Nat Rev Immunol (2016) 16:702–14. doi: 10.1038/nri.2016.93 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Singh A, Joshi V, Jindal AK, Mathew B, Rawat A. An updated review on activated PI3 kinase delta syndrome (APDS). Genes Dis (2019) 7:67–74. doi: 10.1016/j.gendis.2019.09.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Thouenon R, Moreno-Corona N, Poggi L, Durandy A, Kracker S. Activated PI3Kinase delta syndrome–a multifaceted disease. Front Pediatr (2021) 9:652405. doi: 10.3389/fped.2021.652405 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Michalovich D, Nejentsev S. Activated PI3 kinase delta syndrome: From genetics to therapy. Front Immunol (2018) 9:369. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.00369 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Tissue expression of PIK3CD - summary - the human protein atlas . Available at: https://www.proteinatlas.org/ENSG00000171608-PIK3CD/tissue.

- 87. Tissue expression of PIK3R1 - summary - the human protein atlas . Available at: https://www.proteinatlas.org/ENSG00000145675-PIK3R1/tissue.

- 88. Jung S, Gámez-Díaz L, Proietti M, Grimbacher B. “Immune TOR-opathies,” a novel disease entity in clinical immunology. Front Immunol (2018) 9. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.00966 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Driessen GJ, IJspeert H, Wentink M, Yntema HG, van Hagen PM, van Strien A, et al. Increased PI3K/Akt activity and deregulated humoral immune response in human PTEN deficiency. J Allergy Clin Immunol (2016) 138:1744–1747.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2016.07.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Tsujita Y, Mitsui-Sekinaka K, Imai K, Yeh TW, Mitsuiki N, Asano T, et al. Phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN) mutation can cause activated phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase δ syndrome–like immunodeficiency. J Allergy Clin Immunol (2016) 138:1672–1680.e10. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2016.03.055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Seif F, Khoshmirsafa M, Aazami H, Mohsenzadegan M, Sedighi G, Bahar M, et al. The role of JAK-STAT signaling pathway and its regulators in the fate of T helper cells. Cell Communication Signaling (2017) 15:23. doi: 10.1186/s12964-017-0177-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Villarino AV, Kanno Y, Ferdinand JR, O’Shea JJ. Mechanisms of Jak/STAT signaling in immunity and disease. J Immunol (2015) 194:21–7. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1401867 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Villarino AV, Kanno Y, O’Shea JJ. Mechanisms and consequences of jak–STAT signaling in the immune system. Nat Immunol (2017) 18:374–84. doi: 10.1038/ni.3691 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Forbes LR, Vogel TP, Cooper MA, Castro-Wagner J, Schussler E, Weinacht KG, et al. Jakinibs for the treatment of immunodysregulation in patients with gain of function STAT1 or STAT3 mutations. J Allergy Clin Immunol (2018) 142:1665–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2018.07.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Toubiana J, Okada S, Hiller J, Oleastro M, Lagos Gomez M, Aldave Becerra JC, et al. Heterozygous STAT1 gain-of-function mutations underlie an unexpectedly broad clinical phenotype. Blood (2016) 127:3154–64. doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-11-679902 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Milner JD, Vogel TP, Forbes L, Ma CA, Stray-Pedersen A, Niemela JE, et al. Early-onset lymphoproliferation and autoimmunity caused by germline STAT3 gain-of-function mutations. Blood (2015) 125:591–9. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-09-602763 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Fabre A, Marchal S, Barlogis V, Mari B, Barbry P, Rohrlich PS, et al. Clinical aspects of STAT3 gain-of-Function germline mutations: A systematic review. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract (2019) 7:1958–1969.e9. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2019.02.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Warshauer JT, Belk JA, Chan AY, Wang J, Gupta AR, Shi Q, et al. A human mutation in STAT3 promotes type 1 diabetes through a defect in CD8+ T cell tolerance. J Exp Med (2021) 218:e20210759. doi: 10.1084/jem.20210759 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Vogel TP, Milner JD, Cooper MA. The ying and yang of STAT3 in human disease. J Clin Immunol (2015) 35:615–23. doi: 10.1007/s10875-015-0187-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Flanagan SE, Haapaniemi E, Russell MA, Caswell R, Allen HL, De Franco E, et al. Activating germline mutations in STAT3 cause early-onset multi-organ autoimmune disease. Nat Genet (2014) 46:812–4. doi: 10.1038/ng.3040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Angulo I, Vadas O, Garçon F, Banham-Hall E, Plagnol V, Leahy TR, et al. Phosphoinositide 3-kinase δ gene mutation predisposes to respiratory infection and airway damage. Science (2013) 342:866–71. doi: 10.1126/science.1243292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Wentink M, Dalm V, Lankester AC, van Schouwenburg PA, Schölvinck L, Kalina T, et al. Genetic defects in PI3Kδ affect b-cell differentiation and maturation leading to hypogammaglobulineamia and recurrent infections. Clin Immunol (2017) 176:77–86. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2017.01.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Peeters D, Pico-Knijnenburg I, Wieringa D, Rad M, Cuperus R, Ruige M, et al. AKT hyperphosphorylation and T cell exhaustion in down syndrome. Front Immunol (2022) 13. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.724436 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Snow AL, Xiao W, Stinson JR, Lu W, Chaigne-Delalande B, Zheng L, et al. Congenital b cell lymphocytosis explained by novel germline CARD11 mutations. J Exp Med (2012) 209:2247–61. doi: 10.1084/jem.20120831 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Pillay BA, Avery DT, Smart JM, Cole T, Choo S, Chan D, et al. Hematopoietic stem cell transplant effectively rescues lymphocyte differentiation and function in DOCK8-deficient patients. JCI Insight (2019) 4(11):e127527. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.127527 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Randall KL, Chan SS, Ma CS, Fung I, Mei Y, Yabas M, et al. DOCK8 deficiency impairs CD8 T cell survival and function in humans and mice. J Exp Med (2011) 208:2305–20. doi: 10.1084/jem.20110345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Murali AK, Mehrotra S. Apoptosis – an ubiquitous T cell immunomodulator. J Clin Cell Immunol Suppl (2011) 3:2. doi: 10.4172/2155-9899.S3-002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. Mueller YM, De Rosa SC, Hutton JA, Witek J, Roederer M, Altman JD, et al. Increased CD95/Fas-induced apoptosis of HIV-specific CD8(+) T cells. Immunity (2001) 15:871–82. doi: 10.1016/S1074-7613(01)00246-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109. Farmer JR, Allard-Chamard H, Sun N, Ahmad M, Bertocchi A, Mahajan VS, et al. Induction of metabolic quiescence defines the transitional to follicular b cell switch. Sci Signal (2019) 12:eaaw5573. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.aaw5573 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110. Zilberman-Rudenko J, Shawver LM, Wessel AW, Luo Y, Pelletier M, Tsai WL, et al. Recruitment of A20 by the c-terminal domain of NEMO suppresses NF-κB activation and autoinflammatory disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci (2016) 113:1612–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1518163113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111. Shields AM, Bauman BM, Hargreaves CE, Pollard AJ, Snow AL, Patel SY, et al. A novel, heterozygous three base-pair deletion in CARD11 results in b cell expansion with NF-κB and T cell anergy disease. J Clin Immunol (2020) 40:406–11. doi: 10.1007/s10875-019-00729-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112. Aiuti A, Roncarolo MG. Ten years of gene therapy for primary immune deficiencies. Hematology (2009) 2009:682–9. doi: 10.1182/asheducation-2009.1.682 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113. Booth C, Gaspar HB, Thrasher AJ. Gene therapy for primary immunodeficiency. Curr Opin Pediatr (2011) 23:659–66. doi: 10.1097/MOP.0b013e32834cd67a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114. Fox TA, Booth C. Gene therapy for primary immunodeficiencies. Br J Haematol (2021) 193:1044–59. doi: 10.1111/bjh.17269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115. Houghton BC, Booth C. Gene therapy for primary immunodeficiency. Hemasphere (2021) 5:e509. doi: 10.1097/HS9.0000000000000509 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116. Freeman AF. Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in primary immunodeficiencies beyond severe combined immunodeficiency. J Pediatr Infect Dis Soc (2018) 7:S79–82. doi: 10.1093/jpids/piy114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117. Aydin SE, Freeman AF, Al-Herz W, Al-Mousa HA, Arnaout RK, Aydin RC, et al. Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation as treatment for patients with DOCK8 deficiency. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract (2019) 7:848–55. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2018.10.035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118. Boztug K, Schmidt M, Schwarzer A, Banerjee PP, Díez IA, Dewey RA, et al. Stem-cell gene therapy for the wiskott–Aldrich syndrome. N Engl J Med (2010) 363:1918–27. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1003548 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119. Kohn DB, Booth C, Kang EM, Pai SY, Shaw KL, Santilli G, et al. Lentiviral gene therapy for X-linked chronic granulomatous disease. Nat Med (2020) 26:200–6. doi: 10.1038/s41591-019-0735-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120. Perez E. Future of therapy for inborn errors of immunity. Clinic Rev Allerg Immunol (2022) 63:75–89. doi: 10.1007/s12016-021-08916-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121. Khan SH. Genome-editing technologies: Concept, pros, and cons of various genome-editing techniques and bioethical concerns for clinical application. Mol Ther - Nucleic Acids (2019) 16:326–34. doi: 10.1016/j.omtn.2019.02.027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122. Roth TL, Puig-Saus C, Yu R, Shifrut E, Carnevale J, Li PJ, et al. Reprogramming human T cell function and specificity with non-viral genome targeting. Nature (2018) 559:405–9. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0326-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123. Doudna JA. The promise and challenge of therapeutic genome editing. Nature (2020) 578:229–36. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-1978-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124. Jiang F, Doudna JA. CRISPR–Cas9 structures and mechanisms. Annu Rev Biophysics (2017) 46:505–29. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biophys-062215-010822 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125. Doudna JA, Charpentier E. The new frontier of genome engineering with CRISPR-Cas9. Science (2014) 346:1258096. doi: 10.1126/science.1258096 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126. Moon SB, Kim DY, Ko J-H, Kim Y-S. Recent advances in the CRISPR genome editing tool set. Exp Mol Med (2019) 51:1–11. doi: 10.1038/s12276-019-0339-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127. Jinek M, Chylinski K, Fonfara I, Hauer M, Doudna JA, Charpentier E, et al. A programmable dual-RNA-guided DNA endonuclease in adaptive bacterial immunity. Science (2012) 337:816–21. doi: 10.1126/science.1225829 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128. Yang H, Ren S, Yu S, Pan H, Li T, Ge S, et al. Methods favoring homology-directed repair choice in response to CRISPR/Cas9 induced-double strand breaks. Int J Mol Sci (2020) 21:6461. doi: 10.3390/ijms21186461 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129. Adli M. The CRISPR tool kit for genome editing and beyond. Nat Commun (2018) 9:1911. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-04252-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130. Porteus MH, Baltimore D. Chimeric nucleases stimulate gene targeting in human cells. Science (2003) 300:763. doi: 10.1126/science.1078395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131. Urnov FD, Miller JC, Lee YL, Beausejour CM, Rock JM, Augustus S, et al. Highly efficient endogenous human gene correction using designed zinc-finger nucleases. Nature (2005) 435:646–51. doi: 10.1038/nature03556 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132. Bibikova M, Golic M, Golic KG, Carroll D. Targeted chromosomal cleavage and mutagenesis in drosophila using zinc-finger nucleases. Genetics (2002) 161:1169–75. doi: 10.1093/genetics/161.3.1169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133. Rai R, Thrasher AJ, Cavazza A. Gene editing for the treatment of primary immunodeficiency diseases. Hum Gene Ther (2021) 32:43–51. doi: 10.1089/hum.2020.185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134. Nishida K, Arazoe T, Yachie N, Banno S, Kakimoto M, Tabata M, et al. Targeted nucleotide editing using hybrid prokaryotic and vertebrate adaptive immune systems. Science (2016) 353:aaf8729. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf8729 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135. Komor AC, Kim YB, Packer MS, Zuris JA, Liu DR. Programmable editing of a target base in genomic DNA without double-stranded DNA cleavage. Nature (2016) 533:420–4. doi: 10.1038/nature17946 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136. Anzalone AV, Randolph PB, Davis JR, Sousa AA, Koblan LW, Levy , et al. Search-and-replace genome editing without double-strand breaks or donor DNA. Nature (2019) 576:149–57. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1711-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137. Gilbert LA, Horlbeck MA, Adamson B, Villalta JE, Chen Y, Whitehead EH, et al. Genome-scale CRISPR-mediated control of gene repression and activation. Cell (2014) 159:647–61. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.09.029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138. Schmidt R, Steinhart Z, Layeghi M, Freimer JW, Bueno R, Nguyen VQ, et al. CRISPR activation and interference screens decode stimulation responses in primary human T cells. Science (2022) 375:eabj4008. doi: 10.1126/science.abj4008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139. Lin S, Staahl BT, Alla RK, Doudna JA. Enhanced homology-directed human genome engineering by controlled timing of CRISPR/Cas9 delivery. Elife (2014) 3:e04766. doi: 10.7554/eLife.04766.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140. Chu VT, Weber T, Wefers B, Wurst W, Sander S, Rajewsky K, et al. Increasing the efficiency of homology-directed repair for CRISPR-Cas9-induced precise gene editing in mammalian cells. Nat Biotechnol (2015) 33:543–8. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141. Robert F, Barbeau M, Éthier S, Dostie J, Pelletier J. Pharmacological inhibition of DNA-PK stimulates Cas9-mediated genome editing. Genome Med (2015) 7:93. doi: 10.1186/s13073-015-0215-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142. Nambiar TS, Billon P, Diedenhofen G, Hayward SB, Taglialatela A, Cai K, et al. Stimulation of CRISPR-mediated homology-directed repair by an engineered RAD18 variant. Nat Commun (2019) 10:3395. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-11105-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143. De Ravin SS, Brault J, Meis RJ, Liu S, Li L, Pavel-Dinu M, et al. Enhanced homology-directed repair for highly efficient gene editing in hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells. Blood (2021) 137:2598–608. doi: 10.1182/blood.2020008503 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144. Fu Y-W, Dai XY, Wang WT, Yang ZX, Zhao JJ, Zhang JP, et al. Dynamics and competition of CRISPR-Cas9 ribonucleoproteins and AAV donor-mediated NHEJ, MMEJ and HDR editing. Nucleic Acids Res (2021) 49:969–85. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkaa1251 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145. Charpentier M, Khedher AHY, Menoret S, Brion A, Lamribet K, Dardillac E, et al. CtIP fusion to Cas9 enhances transgene integration by homology-dependent repair. Nat Commun (2018) 9:1133. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-03475-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146. Shin JJ, Schröder MS, Caiado F, Wyman SK, Bray NL, Bordi M, et al. Controlled cycling and quiescence enables efficient HDR in engraftment-enriched adult hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells. Cell Rep (2020) 32:108093. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2020.108093 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147. Jayavaradhan R, Pillis DM, Goodman M, Zhang F, Zhang Y, Andreassen PR, et al. CRISPR-Cas9 fusion to dominant-negative 53BP1 enhances HDR and inhibits NHEJ specifically at Cas9 target sites. Nat Commun (2019) 10:2866. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-10735-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148. Ferrari S, Jacob A, Beretta S, Unali G, Albano L, Vavassori V, et al. Efficient gene editing of human long-term hematopoietic stem cells validated by clonal tracking. Nat Biotechnol (2020) 38:1298–308. doi: 10.1038/s41587-020-0551-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149. Rai R, Romito M, Rivers E, Turchiano G, Blattner G, Vetharoy W, et al. Targeted gene correction of human hematopoietic stem cells for the treatment of wiskott - Aldrich syndrome. Nat Commun (2020) 11:4034. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-17626-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150. Shifrut E, Carnevale J, Tobin V, Roth TL, Woo JM, Bui CT, et al. Genome-wide CRISPR screens in primary human T cells reveal key regulators of immune function. Cell (2018) 175:1958–1971.e15. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.10.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151. Schumann K, Lin S, Boyer E, Simeonov DR, Subramaniam M, Gate RE, et al. Generation of knock-in primary human T cells using Cas9 ribonucleoproteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci (2015) 112:10437–42. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1512503112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152. Paquet D, Kwart D, Chen A, Sproul A, Jacob S, Teo S, et al. Efficient introduction of specific homozygous and heterozygous mutations using CRISPR/Cas9. Nature (2016) 533:125–9. doi: 10.1038/nature17664 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153. Haddad E. STAT3: too much may be worse than not enough! Blood (2015) 125:583–4. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-11-610592 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154. de Beaucoudrey L, Puel A, Filipe-Santos O, Cobat A, Ghandil P, Chrabieh M, et al. Mutations in STAT3 and IL12RB1 impair the development of human IL-17-producing T cells. J Exp Med (2008) 205:1543–50. doi: 10.1084/jem.20080321 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155. Liu L, Okada S, Kong XF, Kreins AY, Cypowyj S, Abhyankar A, et al. Gain-of-function human STAT1 mutations impair IL-17 immunity and underlie chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis. J Exp Med (2011) 208:1635–48. doi: 10.1084/jem.20110958 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 156. Zhang Y, Ma CA, Lawrence MG, Break TJ, O'Connell MP, Lyons JJ, et al. PD-L1 up-regulation restrains Th17 cell differentiation in STAT3 loss- and STAT1 gain-of-function patients. J Exp Med (2017) 214:2523–33. doi: 10.1084/jem.20161427 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]