Abstract

Objective

The gut microbiome and its metabolites are influenced by age and stress and reflect the metabolism and health of the immune system. We assessed the gut microbiota and faecal metabolome in a static animal model of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH).

Design

This model was subjected to the following treatments: reverse osmosis water, AFO-202, N-163, AFO-202+N-163 and telmisartan treatment. Faecal samples were collected at 6 and 9 weeks of age. The gut microbiome was analysed using 16S ribosomal RNA sequences acquired by next-generation sequencing, and the faecal metabolome was analysed using gas chromatography-mass spectrometry.

Results

Gut microbial diversity increased greatly in the AFO-202+N-163 group. Postintervention, the abundance of Firmicutes decreased, whereas that of Bacteroides increased and was the highest in the AFO-202+N-163 group. The decrease in the abundance of Enterobacteriaceae and other Firmicutes and the abundance of Turicibacter and Bilophila were the highest in the AFO-202 and N-163 groups, respectively. Lactobacillus abundance was highest in the AFO-202+N-163 group. The faecal metabolite spermidine, which is beneficial against inflammation and NASH, was significantly decreased (p=0.012) in the N-163 group. Succinic acid, which is beneficial in neurodevelopmental and neurodegenerative diseases, was increased in the AFO-202 group (p=0.06). The decrease in fructose was the highest in the N-163 group (p=0.0007). Isoleucine and Leucine decreased with statistical significance (p=0.004 and 0.012, respectively), and tryptophan also decreased (p=0.99), whereas ornithine, which is beneficial against chronic immune-metabolic-inflammatory pathologies, increased in the AFO-202+N-163 group.

Conclusion

AFO-202 treatment in mice is beneficial against neurodevelopmental and neurodegenerative diseases, and has prophylactic potential against metabolic conditions. N-163 treatment exerts anti-inflammatory effects against organ fibrosis and neuroinflammation. In combination, these compounds exhibit anticancer activity.

Keywords: COLONIC MICROFLORA, NUTRITION, INTESTINAL BACTERIA

WHAT IS ALREADY KNOWN ON THIS TOPIC

The influence of the gut microbiome on the faecal metabolome and its association with several diseases are already known.

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS

This study demonstrates the efficacy of beta-1,3–1,6-glucans with prebiotic potentials, beneficially influencing the gut microbiome and metabolome.

HOW THIS STUDY MIGHT AFFECT RESEARCH, PRACTICE OR POLICY

These results recommend an in-depth exploration of the relationship among prebiotics, the gut microbiome and gut–multiorgan axes on the fundamentals of disease onset.

Hidden prophylactic and therapeutic solutions to non-contagious diseases with Aureobasidium pullulans that produces beta-1,3–1,6-glucans may be unveiled.

Introduction

The microbiome is now considered to be a virtual organ of the body, with approximately 100 trillion micro-organisms present in the human gastrointestinal tract. The microbiome encodes over three million genes that produce thousands of metabolites compared with the 23 000 genes in the human genome, thus replacing several host functions and influencing the host’s fitness, phenotype and health. Gut microbiota influence several aspects of human health, including immune, metabolic and neurobehavioural traits.1 The gut microbiota ferments non-digestible substrates, such as dietary fibres and endogenous intestinal mucus, which support the growth of specialist microbes producing short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) and gases. The major SCFAs produced are acetate, propionate and butyrate. Butyrate is essential for maintaining colonic cells, apoptosis of colonic cancer cells, activation of intestinal gluconeogenesis, maintenance of oxygen balance in the gut, prevention of gut microbiota dysbiosis, and has beneficial effects on glucose and energy homoeostasis. Propionate is transported to the liver, where it regulates gluconeogenesis, is an essential metabolite for the growth of other bacteria, and regulates central appetite.1 Gut dysbiosis, that is, an altered state of the microbiota community, is associated with several diseases, including diabetes, metabolic disorders, obesity, cancer, rheumatoid arthritis and neurological disorders such as Parkinson’s disease (PD), Alzheimer’s disease, multiple sclerosis (MS) and autism spectrum disorders (ASD).2 3 The faecal metabolome represents the functional readout of the gut microbial activity; it can be considered an intermediate phenotype mediating the host–microbiome interactions. On average, 67.7%±18.8% of the faecal metabolome variance represents the gut microbial composition. Thus, faecal metabolic profiling is a novel tool for exploring the association between microbiome composition, host phenotypes and disease states.4 Other than faecal microbiota transplantation, probiotics and prebiotic nutritional supplements can help restore the dysbiotic gut to a healthy state.

Beta-glucans are among the most promising nutritional supplements with established efficacy against metabolic diseases, diabetes, cancer, cardiovascular diseases and neurological diseases. Beta-glucans derived from two strains of the black yeast Aureobasidium pullulans, AFO-202 and N-163, have shown beneficial effects against various diseases and conditions. In patients with diabetes, there was a decrease in HbA1c levels from 9.1 to 7.8,5 which was able to regulate dyslipidaemia.6 In children with ASD, AFO-202 beta-glucan improved behavioural patterns and sleep, apart from increased melatonin and alpha-synuclein levels.7 8 In Duchenne muscular dystrophy, N-163 beta-glucan decreased inflammatory markers and increased plasma dystrophin levels in human subjects.9 In a study using the Stelic Animal Model (STAM) of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH),10 AFO-202 beta-glucan was able to regulate metabolism, while N-163 beta-glucan was able to reduce inflammation and fibrosis. Their combination decreased the non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) activity score. In COVID-19,11 12 the combination of AFO-202 beta-glucan and N-163 beta-glucan decreased markers such as IL-6 and C reactive protein (CRP), which are associated with cytokine storms. A study in children with ASD showed that AFO-202 beta-1,3–1,6-glucans exerts its effects primarily by balancing the gut microbiome.13 This study was undertaken as an extension of the NASH study10 to assess the faecal microbiome and metabolome profile before and after administration of AFO-202 and N-163 beta-glucans individually and in combination.

Methods

Mice

This study was conducted in accordance with the Animal Research: Reporting of In Vivo Experiments Guidelines. C57BL/6J mice were obtained from Japan SLC (Tokyo, Japan). Animal care followed the following guidelines: Act on Welfare and Management of Animals (Ministry of the Environment, Japan, Act No. 105; 1 October 1973), Standards relating to the care and management of laboratory animals and relief of pain (Notice No. 88 of the Ministry of the Environment, Japan; 28 April 2006), and Guidelines for proper conduct of animal experiments (Science Council of Japan; 1 June 2006). Protocol approval was obtained from SMC Laboratories, the Japanese equivalent of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (study reference no.: SP_SLMN128-2107-6_1). The mice were maintained in a specific pathogen-free facility under controlled conditions: temperature, 23°C±3°C; humidity, 50%±20%; 12 hours artificial light and dark cycles (light from 8:00 to 20:00 hours); and adequate air exchange.

The STAM for NASH was developed as previously described.10 A single subcutaneous streptozotocin injection of 200 µg (STZ; Sigma-Aldrich, USA) was administered 2 days after birth. Mice were fed a high-fat diet (HFD, 57 kcal% fat, Cat# HFD32, CLEA Japan, Japan) from 4 to 9 weeks of age. All mice developed liver steatosis and diabetes, and steatohepatitis was observed histologically at 3 weeks.

Study groups

The mice were randomly allocated to five study groups (n=8 in each group) (table 1).

Table 1.

Study design and treatment schedule

| Group | No of mice | Test substance | Dose (mg/kg) | Volume (mL/kg) | Regimen | Sacrifice |

| 1 | 8 | Vehicle | – | 5 | PO, QD, 6–9 weeks |

9 weeks |

| 2 | 8 | AFO-202 Beta Glucan |

1 | 5 | PO, QD, 6–9 weeks |

9 weeks |

| 3 | 8 | N-163 Beta Glucan | 1 | 5 | PO, QD, 6–9 weeks |

9 weeks |

| 4 | 8 | AFO-202 Beta Glucan N-163 Beta Glucan |

1 1 |

5 | PO, QD, 6–9 weeks |

9 weeks |

| 5 | 8 | Telmisartan | 10 | 5 | PO, QD, 6–9 weeks |

9 weeks |

PO, per os; QD, every day.

Vehicle group/control group: Mice in this group were orally administered 5 mL/kg of reverse osmosis water as the vehicle solution once daily from 6 to 9 weeks of age.

AFO-202 beta-glucan group: The mice in this group were orally administered 1 mg/kg of AFO-202 beta-glucan supplemented in 5 mL/kg of vehicle once daily from 6 to 9 weeks of age.

N-163 beta-glucan group: The mice were orally administered 1 mg/kg of N-163 beta-glucan supplemented in 5 mL/kg of vehicle once daily from 6 to 9 weeks of age.

AFO-202+N-163 beta-glucan group: The mice were orally administered 1 mg/kg of AFO-202 supplemented in 5 mL/kg of vehicle once daily as well as 1 mg/kg of N-163 supplemented in 5 mL/kg of vehicle once daily from 6 to 9 weeks of age.

Telmisartan group: The mice were orally administered 10 mg/kg telmisartan in the vehicle once daily from 6 to 9 weeks of age.

Test substances

AFO-202 and N-163 beta-glucans were provided by GN Corporation, Japan. Telmisartan (micardis) was purchased from Boehringer Ingelheim (Germany).

Randomisation

NASH model mice were randomised into the aforementioned groups (n=8 each) at 6 weeks of age based on their body weight on the day before starting the treatment. Randomisation was performed by body weight-stratified random sampling using Excel software. They were stratified by body weight to obtain the SD, and the difference in mean weights among the groups was negligible.

Animal monitoring and sacrifice

The viability, clinical signs (lethargy, twitching and laboured breathing) and behaviour of the mice were monitored daily. Body weight was recorded daily before treatment commencement. Significant clinical signs of toxicity, morbidity and mortality were observed before and after solution administration. The animals were sacrificed at 9 weeks of age by exsanguination through direct cardiac puncture under isoflurane anaesthesia (Pfizer, USA).

Collection of faecal pellets samples

Frequency: Faecal samples were collected at 6 weeks of age (before treatment administration) and 9 weeks of age (before sacrifice).

Procedure: At 6 weeks of age, faecal samples were collected from each mouse using the clean catch method. Animals were handled using clean gloves sterilised with 70% ethanol. The abdomen was gently massaged and the bottom of the mouse was positioned over a fresh sterilised petri dish to collect 1–2 faecal pellets. At the time of sacrifice, faecal samples were aseptically collected from the caecum. Tubes containing faeces were immediately placed on ice. These tubes were snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C for shipping. Online supplemental figure 1 shows the groups and corresponding faecal sample numbers allotted for microbiome and metabolomic analyses.

bmjgast-2022-000985supp001.pdf (283.7KB, pdf)

Microbiome analysis

In this analysis, 16S ribosomal RNA (rRNA) sequence data acquired by next-generation sequencing (NGS) from faecal RNA were used to perform community analysis using the Quantitative Insights into Microbial Ecology (QIIME2) programme for microbial community analysis. The raw read data in the FASTQ format output from NGS were trimmed to remove adapter sequences and low-QV regions that may have been included in the data. Cutadapt was used to remove adapter sequences from DNA sequencing reads. Trimmomatic was used as a read-trimming tool for the Illumina NGS data. The adapter sequence was trimmed using the adapter trimming programme Cutadapt if the trimming of the region at the end of the read sequence overlapped the corresponding sequence by at least one base (mismatch tolerance: 20%). When reads containing N were present in at least one of Read1 and Read2, both Read1 and Read2 were removed.

Illumina adapter sequence information:

Read1 3' end side

CTGTCTTCTATACACATCTCCGAGCCCACGAGAC

Read2 3' end side

CTGTCTTCTATACACATCTGACGCTGCCGACGA

Trimming of the low-QV regions was performed on the read data after processing using the QV trimming programme Trimmomatic under the following conditions.

A window of 20 bases was slid from the 5' side, and the area with an average QV<20 was trimmed.

After trimming, only reads with >50 bases remaining in both Read1 and Read2 were used as the outputs.

Population analysis

Microbial community analysis based on the 16S rRNA sequence was performed on the sequence data trimmed in the previous section using the QIIME2. The annotation programme ‘sklearn’ of QIIME2 was used to annotate the amplicon sequence variant (operational taxonomic units) (ASV (OTU)) sequences.

Using ‘sklearn,’ the ASV (OTU) sequences obtained were annotated with taxonomy information, that is, Kingdom/Phylum/Class/Order/Family/Genus/Species, based on the 16S rDNA database.

The dataset of the 16S rDNA database ‘greengenes’ provided on the QIIME2 resource site was used for the analysis. The obtained ASVs (OTUs) were aggregated and graphed based on the taxonomy information and read counts of each specimen. Based on the composition of the bacterial flora of each specimen compiled above, various index values for alpha diversity were calculated.

Metabolome analysis

After lyophilisation, approximately 10 mg of the faecal sample was separated and extracted using the Bligh-Dyer method, and the resulting initial aqueous layer was collected and lyophilised. The residue was derivatised using 2-methoxyamine hydrochloride and N-methyl-N-(trimethylsilyl) trifluoroacetamide and subjected to gas chromatography-mass spectrometry as an analytical sample. 2-Isopropylmalic acid was used as an internal standard. In addition, an operational blank test was conducted.

The analytical equipment used included GCMS-TQ8030 (Shimadzu Corporation, Japan) and BPX5 GC columns (film thickness, 0.25 µm; length, 30 m; inner diameter, 0.25 mm; Shimadzu GC).

Peak detection and analysis

MS-DIAL V.4.7 (http://prime.psc.riken.jp/compms/index.html) was used to analyse and prepare the peak list (peak height) under the conditions described in online supplemental table 1. Thus, peaks that were detected in the quality control (QC) samples and whose coefficient of variation was <20% and whose intensity was more than twice that of the operational blank test were treated as the detected peaks.

bmjgast-2022-000985supp002.pdf (361.7KB, pdf)

Differential abundance analysis, principal component analysis, orthogonal projections to latent structure discriminant analysis and clustering analysis

Principal component analysis (PCA) and orthogonal partial least squares-discriminant analysis (OPLS-DA) were performed to visualise metabolic differences among the experimental groups. SIMCA-P+V.17 (Umetrics) was used for PCA. The normalised peak heights of the sample-derived peaks were used for PCA using all the samples and five points (F18S-12, F18S-14, F18S-16, F18S-18 and F18S-20). The transform was set to zero and the scaling was set to Pareto scaling. Differential metabolites were selected according to their statistically significant variable importance in the projection (VIP) values obtained from the OPLS-DA model. R (https://www.r-project.org/) was used for hierarchical cluster analysis and heat map generation.

Statistical analysis

Statistical data were analysed using Microsoft Excel statistics package analysis software. Graphs were prepared using OriginLab Origin 2021b. For OPLS-DA, values from a two-tailed Student’s t-test were applied to the normalised peak areas; metabolites with VIP values >1 and p<0.05 were included. The Euclidean distance and Ward’s method were used to analyse the heat map. The mean and variance were normalised so that the mean was 0 and the variance was 1.

For other normally distributed variables, the t-test or analysis of variance with Tukey’s honestly significant difference was used; values of p<0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

There were no significant differences in mean body weight on any day during the treatment period between the control and other treatment groups. There were no significant differences in mean body weight on the day of sacrifice between the treatment groups.

Effects on NASH

The effects of AFO-202 and N-163 beta-glucans on NASH were reported in our earlier paper10 in a different set of animals subjected to the same interventions. Briefly, AFO-202 beta-glucan significantly decreased inflammation-associated hepatic cell ballooning and steatosis, whereas N-163 beta-glucan significantly decreased fibrosis and inflammation. The combination of AFO-202 and N-163 significantly decreased NAS.10

Gut microbiome analysis

The alpha-diversity indices, Simpson and Shannon indices, showed that the postintervention gut microbial diversity was highest in the AFO-202+N-163 group (figure 1A, B).

Figure 1.

Alpha-diversity indices. (A) Simpson index; (B) Shannon index reflecting the diversity of operational taxonomic units in samples. Both indices showed that the AFO-202+N-163 group had the highest bacterial abundance postintervention.

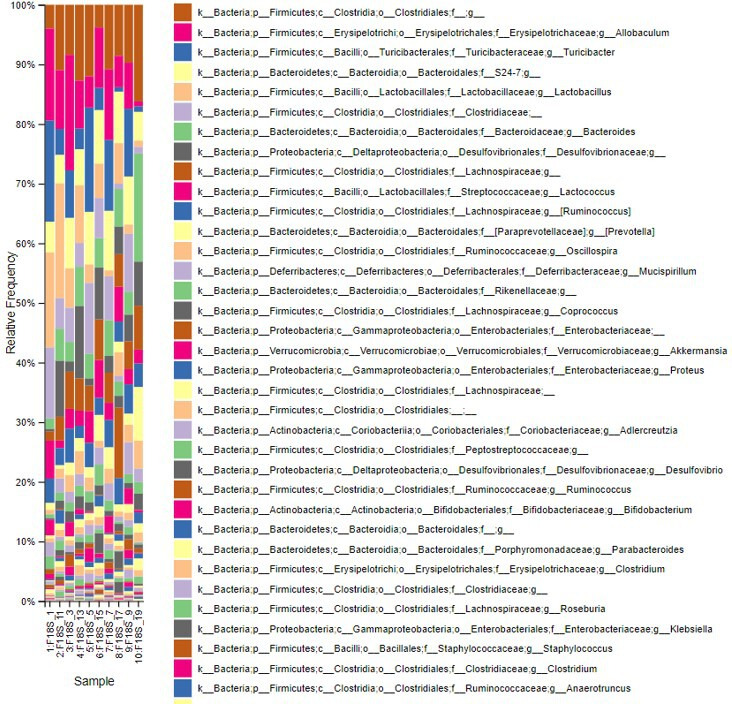

Regarding taxonomic profiling, Firmicutes was the most abundant phylum, followed by Bacteroides (figure 2 and online supplemental figure 2).

Figure 2.

Index of the most abundant taxa across species levels.

bmjgast-2022-000985supp003.pdf (403.8KB, pdf)

However, postintervention, the abundance of Firmicutes decreased, whereas that of Bacteroides increased. This decrease and increase in the abundance of Firmicutes and Bacteroides, respectively, were highest in the AFO-202+N-163 and telmisartan groups when compared with the other groups (figure 2 and online supplemental figure 2).

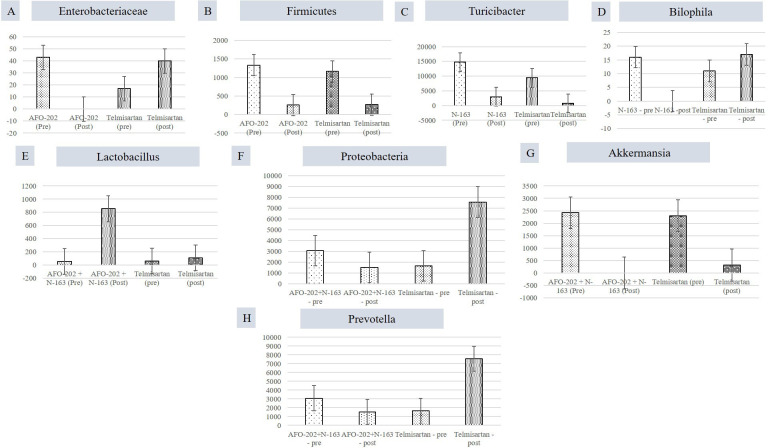

When individual taxa were analysed in each of the beta-glucan groups compared with the telmisartan group, the decrease in the abundance of Enterobacteriaceae and Firmicutes was the highest in the AFO-202 group (figure 3A, B). Turicibacter abundance decrease was the highest in the N-163 group (figure 3C). Bilophila abundance increased in all groups, but decreased to 0 in the N-163 group (figure 3D). The increase in Lactobacillus abundance was the highest in the AFO-202+N-163 group (figure 3E). The abundance of Proteobacteria decreased in the AFO-202+N-163 group but increased in the telmisartan group (figure 3F). The decrease in Akkermansia abundance was the highest in the AFO-202+N-163 group (figure 3G). Prevotella decreased in AFO-202+N-163 group (figure 3H)

Figure 3.

Differences between the read count of selected bacteria before and after intervention. (A) Enterobacteriaceae; (B) Firmicutes; (C) Turicibacter; (D) Bilophila; (E) Lactobacillus; (F) Proteobacteria (G) Akkermansia; (H) Prevotella.

Faecal metabolome analysis

The resulting score plot of PCA using the normalised peak heights of the 10 samples (preintervention and postintervention of the five groups) is shown in online supplemental figure 3. The contributions of the first and second principal components were 55 and 20%, respectively. PCA of the five postintervention samples (F18S-12, F18S-14, F18S-16, F18S-18 and F18S-20) using the peak heights after normalisation; the obtained score plot is shown in online supplemental figure 4A, B and the loading plot in online supplemental figure 4C, D. The contributions of the first and second principal components were 49 and 34%, respectively.

bmjgast-2022-000985supp004.pdf (264.8KB, pdf)

bmjgast-2022-000985supp005.pdf (447.8KB, pdf)

The peak heights of all the detected metabolite compounds after normalisation are shown in online supplemental table 2. The number of peaks detected in the QC samples was 108, of which 53 samples were qualitatively determined and 55 samples remained unknown.

Differential abundance analysis and log2 fold change results are shown in online supplemental figure 5.

bmjgast-2022-000985supp006.pdf (326.7KB, pdf)

Score plots of PCA and compounds with VIP values≥1 in the OPLS-DA are shown in online supplemental figure 4. Online supplemental table 3 shows the compounds with VIP values ≥1 and their coefficients in the OPLS-DA. PCA of the control group showed that the contribution of the first principal component axis (PC1) was 96.7% and that of the second principal component axis (PC2) was 1.5%. PCA revealed that the contributions of PC1 and PC2 in the AFO-202, N-163, AFO-202+N-163, and telmisartan groups were 90.4% and 4.9%, 94.8% and 2.1%, 96.5% and 1.4%, and 95.1% and 1.9%, respectively.

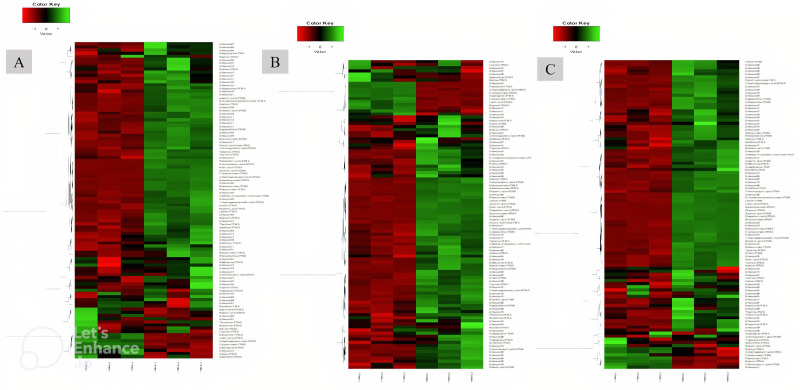

In all groups, except for the telmisartan group, phosphoric acid showed the highest log2 fold increase, whereas putrescine showed the highest decrease. With respect to specific compounds, the increase in succinic acid was highest in the AFO-202 group, with statistical significance (p=0.06) (figure 4A). The increase in phosphoric acid was highest in the N-163 group, followed by the AFO-202+N-163 and AFO-202 groups (figure 4B), but the difference was not statistically significant (p=0.21). The decrease in fructose was highest in the N-163 group (p=0.0007) (figure 4C). Tryptophan decreased in the AFO-202+N-163 group but not significantly (p=0.99); however, it increased in the other groups (figure 4D). The decrease in isoleucine and leucine was highest in the AFO-202 group, with statistical significance (p=0.004 and 0.012, respectively) (figure 4E, F). The changes in phenylalanine can be observed from Figure 4G; however, the difference was not statistically significant (p=0.18) (figure 4G). Methionine levels increased in all groups but were not statistically significant (p=0.14) (figure 4H). The decrease in spermidine was highest in the N-163 group, with statistical significance (p=0.012) (figure 4I). The increase in ornithine was highest in the AFO-202+N-163 group (figure 4J). Euclidean distance hierarchical clustering analysis demonstrated that the different intensity levels of the characteristic metabolites also matched the aforementioned findings (figure 5 and online supplemental figure 6).

Figure 4.

Peak heights of the detected compounds after normalisation. (A) Succinic acid; (B) phosphoric acid; (C) Fructose; (D) Tryptophan; (E) Isoleucine; (F) Leucine; (G) Phenylalanine; (H) Methionine; (I) Spermidine; (J) Ornithine. (** significant;* not significant; p<0.05). TMS, trimethylsilylation.

Figure 5.

Euclidean distance hierarchical clustering analysis demonstrating the different intensity levels of characteristic metabolites in the treatment groups. (A) AFO-202 group; (B) N-163 group; (C) AFO-202+N-163 (Comparison images of the telmisartan and control groups are shown in online supplemental figure 6).

bmjgast-2022-000985supp007.pdf (220.4KB, pdf)

Discussion

This is the first study to investigate the influence of beta-glucans on the profiles of the faecal gut microbiome and metabolome in a NASH murine model. This study assessed two different beta-glucans produced by different strains of the same species of black yeast, A. pullulans. Beta-glucans are obtained from different sources, and their functionality depends on the source and extraction/purification processes.14 The beta-glucans described in this study, AFO-202 and N-163 strains of A. pullulans black yeast, are unique as they are produced as exopolysaccharides without the need for extraction/purification; hence, their biological actions are superior to those of the other strains.15 Furthermore, both beta-glucans have the same chemical formula but different structural formulas, and hence exert diverse biological actions. AFO-202 beta-glucan has beneficial metabolic benefits as it regulates blood glucose levels5 and enhances immunity in immune-related infections, such as COVID-19.11 12 Moreover, it has positive effects on melatonin and alpha-synuclein neurotransmitters and sleep and behaviour in neurodevelopmental disorders, such as ASD.7 8 In a previous NASH animal study, AFO-202 beta-glucan significantly decreased the inflammation-associated hepatic cell ballooning and steatosis.10 The N-163 beta-glucan has immunomodulatory benefits in terms of regulating dyslipidaemia, which is evident from the balance in the levels of non-esterified fatty acids16 and a decrease in fibrosis and inflammation in NASH.10 The combination of AFO-202 and N-163 decreased proinflammatory markers and increased anti-inflammatory markers in healthy human volunteers,17 decreased NAS in the NASH model,10 and significantly controlled immune-mediated dysregulated levels of interleukin-6, CRP, and ferritin in COVID-19 patients.11 12 In a study on gut microbiome analysis in ASD patients, AFO-202 showed efficient control of Enterobacteriaceae as well as beneficial reconstitution of the gut microbiome with positive effects on ASD.13 This study aimed to evaluate the benefits of AFO-202 and N-163, individually and in combination, in an animal model of NASH.

We used STAM to treat NASH.10 18 19 In this model, HFD-fed mice were allowed to develop liver steatosis by administering streptozotocin solution 2 days after birth. This model recapitulates most of the features of the metabolic syndrome of NASH that occurs in humans, and the HFD leads to diabetes, dyslipidaemia and liver steatosis. Therefore, the gut microbiome and faecal metabolite profiles present at baseline recapitulate those of metabolic syndrome.20 21 This leads to pathophysiological problems in different organ systems of the body, including the heart, liver, and kidneys, as well as immune-metabolic interactions, leading to a decline in the immune system with ageing and its associated complications. Therefore, this study could serve as a forerunner to study the effects of beta-glucans on the different aspects of metabolic syndrome-associated pathologies as well as conditions associated with immune-metabolic interactions, including neurological disorders wherein immune-metabolic interactions have profound implications.20

Relevance of metabolome and microbiome

An abundance of bacterial species such as Proteobacteria, Enterobacteriaceae and Escherichia coli has been reported in humans with NAFLD. A greater abundance of Prevotella species has been reported in children with obesity and NAFLD.21 22 In this study, there was a decrease in the Enterobacteriaceae abundance with AFO-202 and a significant decrease in the Prevotella abundance with AFO-202+N-163 (Figure 3). In terms of faecal metabolites, an increase in tryptophan was observed in the N-163 group, but not more than that in the telmisartan group. In NAFLD, tryptophan metabolism is disturbed, and supplementation with tryptophan is reportedly beneficial because it increases intestinal integrity and improves liver steatosis and function in an NAFLD mouse model.22 Decreased butyrate production increases intestinal inflammation, gut permeability, endotoxaemia and systemic inflammation. An increased abundance of 2-hydroxyisobutyric acid was observed in the AFO-202+N-163 group (online supplemental table 2). Isobutyrate is a precursor of n-butyrate23 and further research on whether there is conversion of isobutryate to butyrate in the gut in a positive manner by the action of beneficial microbiota is warranted.

Potential in neurological illnesses

Neurodevelopmental and neurodegenerative disorders

In addition to the influence of beta-glucans on the profiles of the faecal gut microbiome and metabolome in a NASH murine model, we previously reported a decrease in the abundance of Enterobacteriaceae, E. coli, Akkermansia muciniphila CAG:154, Blautia spp, Coprobacillus spp and Clostridium bolteae CAG:59. Furthermore, there was an increase in the abundance of Faecalibacterium prausnitzii and Prevotella copri following AFO-202 administration in children with ASD.13 In this study, the decrease in the abundance of Enterobacteriaceae was the highest in the AFO-202 group (figure 3). Succinic acid, which is reportedly low in individuals,24 was found to be the highest in the AFO-202 group. In several neurodegenerative diseases, such as PD, the levels of amino acids, such as isoleucine, leucine and phenylalanine, have been found to be high in the faecal metabolome.25 In this study, the decrease in the levels of these amino acids was the highest in the AFO-202 group (figure 4).

Neuroinflammatory disorders

Turicibacter has been associated with inflammatory conditions, such as inflammatory bowel disease and other chronic immune-mediated inflammatory diseases, such as MS, owing to its correlation with the expression of tumour necrosis factor.26 In this study, the N-163 and telmisartan groups showed a decrease in Turicibacter abundance (figure 3). Similarly, a significant increase in the relative abundance of Desulfovibrionaceae (Bilophila) was reported in early-onset paediatric MS.27 In this study, the N-163 group showed a reduction in the abundance of Bilophila, whereas the telmisartan group showed an increase after intervention (figure 3). Corroborating this finding, inflammatory conditions presented high amounts of sulfur-containing metabolites, such as methionine,28 whose increase was the lowest in the N-163 group (figure 4H). A. muciniphila, a mucosal-dwelling anaerobe, is a double-edged sword.29 It was previously reported that its abundance is reduced in various metabolic disorders, including obesity, dyslipidaemia and type 2 diabetes, which fuelled the development of Akkermansia-based probiotic therapies to combat metabolic disorders.30 However, recent evidence suggests that an increase in the abundance of Akkermansia has been reported in patients with PD and MS.31 In this study, there was a significant decrease in Akkermansia abundance in the AFO-202+N-163 group (figure 3G).

Other implications

In overweight/obese humans, low faecal bacterial diversity is reportedly associated with a marked increase in fat tissue dyslipidaemia, impaired glucose homoeostasis and an increased incidence of low-grade inflammation.32 In this study, bacterial diversity increased after the intervention, especially in the AFO-202+N-163 group, which showed the highest diversity in the Shannon and Simpson indices (figure 1). Most studies have reported that an increase in Firmicutes and a decrease in Bacteroides abundance is directly proportional to body weight gain.32 33 In this study, there was a clear decrease in Firmicutes and increase in Bacteroides abundance in all the groups post-intervention; however, the highest change was in the AFO-202+N-163 and telmisartan groups (figure 3). Spermidine is a metabolite that is associated with inflammation and cancer.34 The decrease in spermidine level was the highest in the N-163 group (figure 4I). Ornithine levels are usually low in colorectal cancer patients.35 The increase in ornithine levels was the highest in the AFO-202+N-163 group in this study. Lactobacillus is a common probiotic used as prophylaxis and treatment in chronic conditions, such as cancer,36 as well as for promoting better health. The increase in Lactobacillus abundance was the highest in the AFO-202+N-163 group (figure 3). Steroids are common immunosuppressants used to treat chronic autoimmune conditions as well as organ transplant recipients. Steroid use has been reported to cause an increase in E. coli and Enterococcus and a decrease in Bacteroides abundance.37 In this study, the control of Enterobacteriaceae and an increase in Bacteroides abundance with AFO-202, N-163, and their combination make them worthy adjuncts to medications such as steroids.

Conclusion

Two strains of black yeast A. pullulans, AFO-202 and N-163, produce beta-glucans that increase gut microbial diversity, control harmful bacteria, promote healthy bacteria and induce beneficial changes in faecal metabolites, all indicative of a healthy profile, both individually and in combination in the NASH animal model. The results of this study support the use of AFO-202 beta-glucan as an agent for metabolic regulation, N-163 beta-glucan as an immune-modulator, and together they are to be considered as potentially effective and safe adjuncts in the management of NASH and as prophylaxis in other chronic inflammatory and immune-dysregulated conditions.

bmjgast-2022-000985supp008.xlsx (473.7KB, xlsx)

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to dedicate this paper to the memory of Mr. Takashi Onaka, who passed away on the 1 June 2022 at the age of 90 years, who played an instrumental role in successfully culturing and industrial scale up of AFO-202 and N-163 strains of Aureobasidium pullulans after their isolation by Professor Noboru Fujii, producing the novel beta glucans described in this study. They thank, Mr. Yasushi Onaka, Mr Masato Onaka, Mr. Yasunori Ikeue, Dr Mitsuru Nagataki and Mr Ken Sakanishi of Sophy, Ms. Eiko Amemiya of II Dept. of Surgery, University of Yamanashi, Mr Yoshio Morozumi and Ms Yoshiko Amikura of GN Corporation, Japan and Loyola-ICAM College of Engineering and Technology (LICET) for their support to our research work.

Footnotes

Contributors: SJKA and NI contributed to conception and design of the study. RS performed the literature search. SJKA, GAL, NY and SP drafted the manuscript. MI, KR, SS, NR and VDD performed critical revision of the manuscript. All the authors read, and approved the submitted version. SJKA is the guarantor who accepts full responsibility for the finished work and/or the conduct of the study, had access to the data, and controlled the decision to publish.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: SJKA is a shareholder in GN, Japan which holds shares of Sophy, Japan., the manufacturers of novel beta glucans using different strains of Aureobasidium pullulans; a board member in both the companies and also an applicant to several patents of relevance to these beta glucans.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as online supplemental information.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

References

- 1.Valdes AM, Walter J, Segal E, et al. Role of the gut microbiota in nutrition and health. BMJ 2018;361:k2179. 10.1136/bmj.k2179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ghaisas S, Maher J, Kanthasamy A. Gut microbiome in health and disease: linking the microbiome-gut-brain axis and environmental factors in the pathogenesis of systemic and neurodegenerative diseases. Pharmacol Ther 2016;158:52–62. 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2015.11.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shreiner AB, Kao JY, Young VB. The gut microbiome in health and in disease. Curr Opin Gastroenterol 2015;31:69–75. 10.1097/MOG.0000000000000139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zierer J, Jackson MA, Kastenmüller G, et al. The fecal metabolome as a functional readout of the gut microbiome. Nat Genet 2018;50:790–5. 10.1038/s41588-018-0135-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dedeepiya VD, Sivaraman G, Venkatesh AP, et al. Potential effects of nichi glucan as a food supplement for diabetes mellitus and hyperlipidemia: preliminary findings from the study on three patients from India. Case Rep Med 2012;2012:1–5. 10.1155/2012/895370 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ganesh JS, Rao YY, Ravikumar R, et al. Beneficial effects of black yeast derived 1-3, 1-6 Beta Glucan-Nichi Glucan in a dyslipidemic individual of Indian origin--a case report. J Diet Suppl 2014;11:1–6. 10.3109/19390211.2013.859211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Raghavan K, Dedeepiya VD, Ikewaki N, et al. Improvement of behavioural pattern and alpha-synuclein levels in autism spectrum disorder after consumption of a beta-glucan food supplement in a randomised, parallel-group pilot clinical study. BMJ Neurol Open 2022;4:e000203. 10.1136/bmjno-2021-000203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Raghavan K, Dedeepiya VD, Kandaswamy R, et al. Improvement of sleep patterns and serum melatonin levels in children with autism spectrum disorders after consumption of beta-1,3/1,6-glucan in a pilot clinical study. Brain and Behaviour. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Raghavan K, Dedeepiya VD, Srinivasan S. Disease-Modifying immune-modulatory effects of the N-163 strain of Aureobasidium pullulans-produced 1,3-1,6 beta glucans in young boys with Duchenne muscular dystrophy: results of an open-label, prospective, randomized, comparative clinical study. medRxiv 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ikewaki N, Kurosawa G, Iwasaki M. Hepatoprotective effects of Aureobasidium pullulans derived beta 1,3-1,6 biological response modifier glucans in a STAM- animal model of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Hepatology-2022 In Press 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pushkala S, Seshayyan S, Theranirajan E. Efficient control of IL-6, CRP and ferritin in Covid-19 patients with two variants of Beta-1,3-1,6 glucans in combination, within 15 days in an open-label prospective clinical trial. medRxiv 2021;1267778. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Raghavan K, Dedeepiya VD, Suryaprakash V, et al. Beneficial effects of novel Aureobasidium pullulans strains produced beta-1,3-1,6 glucans on interleukin-6 and D-dimer levels in COVID-19 patients; results of a randomized multiple-arm pilot clinical study. Biomed Pharmacother 2022;145:112243. 10.1016/j.biopha.2021.112243 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Raghavan K, Dedeepiya VD, Yamamoto N, et al. Benefits of gut microbiota reconstitution by beta 1,3-1,6 glucans in subjects with autism spectrum disorder and other neurodegenerative diseases. Journal of Alzheimers Disease 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bashir KM, Choi J-S. Clinical and physiological perspectives of β-glucans: the past, present, and future. Int J Mol Sci 2017;18:1906. 10.3390/ijms18091906 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ikewaki N, Fujii N, Onaka T, et al. Immunological Actions of Sophy β-Glucan (β-1,3-1,6 Glucan), Currently Available Commercially as a Health Food Supplement. Microbiol Immunol 2007;51:861–73. 10.1111/j.1348-0421.2007.tb03982.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ikewaki N, Onaka T, Ikeue Y. Beneficial effects of the AFO-202 and N-163 strains of Aureobasidium pullulans produced 1,3-1,6 beta glucans on non-esterified fatty acid levels in obese diabetic KKAy mice: a comparative study. bioRxiv 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ikewaki N, Sonoda T, Kurosawa G. Immune and metabolic beneficial effects of beta 1,3-1,6 glucans produced by two novel strains of Aureobasidium pullulans in healthy middle-aged Japanese men: an exploratory study. medRxiv 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stam model. Available: https://www.smccro-lab.com/service/service_disease_area/stam.html

- 19.Nakashima A, Sugimoto R, Suzuki K, et al. Anti-fibrotic activity of Euglena gracilis and paramylon in a mouse model of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. Food Sci Nutr 2019;7:139–47. 10.1002/fsn3.828 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dantzer R. Neuroimmune interactions: from the brain to the immune system and vice versa. Physiol Rev 2018;98:477–504. 10.1152/physrev.00039.2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kolodziejczyk AA, Zheng D, Shibolet O, et al. The role of the microbiome in NAFLD and NASH. EMBO Mol Med 2019;11:e9302. 10.15252/emmm.201809302 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen J, Vitetta L. Gut microbiota metabolites in NAFLD pathogenesis and therapeutic implications. Int J Mol Sci 2020;21:5214. 10.3390/ijms21155214 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rezanka T, Reichelová J, Kopecký J. Isobutyrate as a precursor of n-butyrate in the biosynthesis of tylosine and fatty acids. FEMS Microbiol Lett 1991;68:33–6. 10.1016/0378-1097(91)90390-v [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kang D-W, Adams JB, Vargason T, et al. Distinct fecal and plasma metabolites in children with autism spectrum disorders and their modulation after microbiota transfer therapy. mSphere 2020;5:e00314–20. 10.1128/mSphere.00314-20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vascellari S, Palmas V, Melis M, et al. Gut Microbiota and Metabolome Alterations Associated with Parkinson’s Disease. mSystems 2020;5:e00561–20. 10.1128/mSystems.00561-20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bernstein CN, Forbes JD. Gut microbiome in inflammatory bowel disease and other chronic immune-mediated inflammatory diseases. Inflamm Intest Dis 2017;2:116–23. 10.1159/000481401 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tremlett H, Fadrosh DW, Faruqi AA. US network of pediatric MS centers. gut microbiota in early pediatric multiple sclerosis: a case-control study. Eur J Neurol 2016;23:1308–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Walker A, Schmitt-Kopplin P. The role of fecal sulfur metabolome in inflammatory bowel diseases. Int J Med Microbiol 2021;311:151513. 10.1016/j.ijmm.2021.151513 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cirstea M, Radisavljevic N, Finlay BB. Good bug, bad bug: breaking through microbial stereotypes. Cell Host Microbe 2018;23:10–13. 10.1016/j.chom.2017.12.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Berer K, Gerdes LA, Cekanaviciute E, et al. Gut microbiota from multiple sclerosis patients enables spontaneous autoimmune encephalomyelitis in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2017;114:10719–24. 10.1073/pnas.1711233114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Heintz-Buschart A, Pandey U, Wicke T, et al. The nasal and gut microbiome in Parkinson's disease and idiopathic rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder. Mov Disord 2018;33:88–98. 10.1002/mds.27105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Davis CD. The gut microbiome and its role in obesity. Nutr Today 2016;;51:167–74. 10.1097/NT.0000000000000167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jumpertz R, Le DS, Turnbaugh PJ, et al. Energy-balance studies reveal associations between gut microbes, caloric load, and nutrient absorption in humans. Am J Clin Nutr 2011;94:58–65. 10.3945/ajcn.110.010132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yoshimoto S, Mitsuyama E, Yoshida K, et al. Enriched metabolites that potentially promote age-associated diseases in subjects with an elderly-type gut microbiota. Gut Microbes 2021;13:1–11. 10.1080/19490976.2020.1865705 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Le Gall G, Guttula K, Kellingray L, et al. Metabolite quantification of faecal extracts from colorectal cancer patients and healthy controls. Oncotarget 2018;9:33278–89. 10.18632/oncotarget.26022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lu K, Dong S, Wu X, et al. Probiotics in cancer. Front Oncol 2021;11:638148. 10.3389/fonc.2021.638148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gibson CM, Childs-Kean LM, Naziruddin Z, et al. The alteration of the gut microbiome by immunosuppressive agents used in solid organ transplantation. Transpl Infect Dis 2021;23:e13397. 10.1111/tid.13397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjgast-2022-000985supp001.pdf (283.7KB, pdf)

bmjgast-2022-000985supp002.pdf (361.7KB, pdf)

bmjgast-2022-000985supp003.pdf (403.8KB, pdf)

bmjgast-2022-000985supp004.pdf (264.8KB, pdf)

bmjgast-2022-000985supp005.pdf (447.8KB, pdf)

bmjgast-2022-000985supp006.pdf (326.7KB, pdf)

bmjgast-2022-000985supp007.pdf (220.4KB, pdf)

bmjgast-2022-000985supp008.xlsx (473.7KB, xlsx)

Data Availability Statement

All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as online supplemental information.