Abstract

Pathogens often encounter stressful conditions inside their hosts. In the attempt to characterize the stress response in Brucella suis, a gene highly homologous to Escherichia coli clpB was isolated from Brucella suis, and the deduced amino acid sequence showed features typical of the ClpB ATPase family of stress response proteins. Under high-temperature stress conditions, ClpB of B. suis was induced, and an isogenic B. suis clpB mutant showed increased sensitivity to high temperature, but also to ethanol stress and acid pH. The effects were reversible by complementation. Simultaneous inactivation of clpA and clpB resulted in a mutant that was sensitive to oxidative stress. In B. suis expressing gfp, ClpA but not ClpB participated in degradation of the green fluorescent protein at 42°C. We concluded that ClpB was responsible for tolerance to several stresses and that the lethality caused by harsh environmental conditions may have similar molecular origins.

Brucella suis is a gram-negative, facultative intracellular bacterium and one of the causative agents of brucellosis in humans and animals (2). Oral infection, which is considered a natural route of infection by brucellae, and localization of the bacteria inside the host cell phagosome most likely expose the pathogen to various stresses. In response to environmental stress conditions such as elevated temperatures, variation in pH, and starvation, a certain number of proteins are induced or repressed in Brucella spp., among which are the GroE and DnaK heat shock proteins (12, 16, 24). In intracellular brucellae, which encounter stressful conditions such as acidic pH (23) and possibly oxidative stress due to the presence of oxygen radicals, the known stress proteins GroEL and DnaK are induced during infection, and DnaK is essential for multiplication of B. suis in macrophage-like cells (12, 17). The HtrA (high-temperature requirement) stress protein is involved in high-level spleen colonization with Brucella abortus in mice (5). Several other stress response proteins including ClpA, ClpB, ClpC, and ClpX, are members of a family of proteins called the Clp ATPases (HSP100 proteins), represented in prokaryotes and eukaryotes with a high degree of conservation (28). Clp stress proteins can be induced by high temperature, oxidative stress, high salt or ethanol concentration, and iron limitation (14, 26, 28). In addition to being sensitive to various stresses, Listeria monocytogenes clpC mutants are attenuated for virulence in mice (26).

Our article describes the isolation and characterization of a B. suis gene encoding a homolog of the ClpB stress response proteins. An isogenic clpB mutant and the complemented strain were constructed and compared with the wild type and a clpA mutant (4) for survival at high temperature, at different ethanol concentrations, at acid pH, and in the presence of hydrogen peroxide. In addition, the effect of hydrogen peroxide on a clpAB double mutant was studied, and the possible participation of ClpA and ClpB in protein degradation was analyzed.

B. suis 1330 (biovar 1) was grown in tryptic soy (TS) broth for 24 h or on TS agar for 72 h at 37°C. When needed, antibiotics were added (25 μg of chloramphenicol per ml and 50 μg of kanamycin per ml). Escherichia coli strains were grown in Luria-Bertani (LB) broth or on LB agar. Antibiotics used were ampicillin (50 μg/ml), kanamycin (50 μg/ml), and chloramphenicol (25 μg/ml).

ClpB is highly conserved in B. suis.

A 380-bp DNA fragment was amplified by PCR from the second ATP-binding domain of the Escherichia coli clpB gene with the oligonucleotides 5′-TGGCGGATCCAAATCGCCCG-3′ and 5′-CGACCGTTCTCCCTTGCCCG-3′ (11, 32), radiolabeled, and hybridized to a genomic Southern blot of B. suis DNA under the previously described conditions (4). A 2.7-kb HindIII fragment containing the 3′ end of B. suis clpB recognized by the probe was cloned into pUC18, and a 4-kb EcoRV fragment with the 5′ end was isolated in a second cloning step and fused in the proper orientation to generate the intact clpB gene, yielding plasmid pUC-CLPB. The fusion site was verified by sequencing.

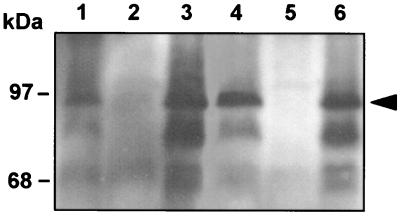

Nucleotide sequence analysis performed with the automated Applied Biosystems 373A DNA sequencer revealed an open reading frame of 2,625 nucleotides coding for 874 amino acids, flanked by a putative ribosome-binding site and a potential rho-independent transcription terminator. The theoretical molecular mass of this protein was 97 kDa, which was in agreement with the mass of the protein recognized by anti-E. coli ClpB antiserum in lysates of B. suis (Fig. 1). Using the FASTA algorithm (22), B. suis ClpB showed 59% amino acid identity over its entire length with ClpB of E. coli (9) and of Haemophilus influenzae (6). A multiple sequence alignment of the three protein sequences performed with ClustalW 1.60 (34) revealed the typical features of the Clp ATPases, with two nucleotide-binding regions, each containing the A and B box nucleotide-binding motifs separated by a long spacer of 123 amino acids, typical of the ClpB subfamily (31). The two characteristic internal signature sequences DASNLLKPALARG and RIDMSEFMEKHSVSRLIGA were found at positions 295 to 307 and 632 to 650, respectively, of the protein sequence, and the sensor and substrate discrimination domain, involved in substrate recognition by Clp ATPases (30), was identified as the motif GARPLKRVI at positions 814 to 822.

FIG. 1.

Expression of b-clpB in B. suis at 37°C (lanes 1 to 3) and 46°C (lanes 4 to 6). Lysates equivalent to 109 bacteria were loaded per lane. Western blot analysis was performed with polyclonal anti-E. coli ClpB antibodies. Lanes 1 and 4, wild-type B. suis with control plasmid pBBR1MCS; lanes 2 and 5, B. suis clpB null mutant with pBBR1MCS; lanes 3 and 6, B. suis clpB mutant complemented with pBBR1-CLPB. The arrow indicates the position of ClpB.

ClpB is involved in survival of B. suis at high temperature, in the presence of ethanol, and at acid pH.

In order to evaluate a possible role of the ClpB homolog of B. suis in stress response, we constructed a clpB deletion mutant. In the construct containing the 3′ half of clpB, a 400-bp EcoRV-Bsu15I fragment located within the open reading frame encoding ClpB was replaced by the kanamycin resistance gene from pUC4K. The whole insert was blunted and recloned into the Brucella suicide vector pCVD442 (3) prior to electroporation of B. suis (4). clpB inactivation by double recombination was confirmed by Southern blot analysis (not shown) and by Western blot using polyclonal anti-E. coli ClpB cross-reacting with the homologous protein of B. suis (Fig. 1). For complementation, cloned clpB of B. suis was inserted as a 5-kb PvuII fragment into the broad-host-range cloning vector pBBR1MCS (13), introduced as plasmid pBBR1-CLPB into the clpB null mutant of B. suis, and expression of clpB was visualized by immunoblot (Fig. 1). Growth rates at 22, 37, and 42°C in TS medium were not significantly different for wild-type bacteria and the mutant. For Western blot analysis with anti-E. coli ClpB antibodies, bacteria were grown to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.5 in TS broth at 37°C, centrifuged, washed once in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and resuspended in 1 ml of TS broth at the appropriate temperature, 37 or 46°C. The bacteria were incubated for 2 h, followed by heat killing at 65°C for 45 min and one wash in PBS. For sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE), total protein equivalent to 109 bacteria was loaded onto SDS–12.5% polyacrylamide gels and separated according to standard protocols. Following transfer of proteins, ClpB from B. suis was detected by chemiluminescence using a 1,000-fold-diluted rabbit anti-E. coli ClpB antiserum (35) and anti-rabbit immunoglobulin horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody. B. suis ClpB was induced approximately threefold under heat stress conditions at 46°C (Fig. 1, lanes 1 and 4), as measured using SigmaGel software (SPSS Science, Chicago, Ill.), confirming this characteristic property previously described for ClpB of E. coli (11). In the strain overexpressing clpB, the induction was not readily visible, possibly due to a multicopy effect of plasmid pBBR1-CLPB and high levels of expression at 37°C (Fig. 1, lanes 3 and 6).

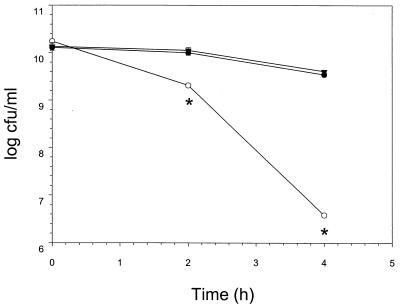

To study sensitivity at high temperature, log-phase cultures at 37°C were resuspended in an equal volume of heated TS medium and incubated for 2 and 4 h at 50°C with shaking. Serial dilutions of samples were plated on TS agar to determine the concentration of viable bacteria. The decrease in viability of the clpB mutant was significantly greater at 2 and 4 h than that of the wild type (Fig. 2; P < 0.001). Complementation of the mutant in trans with the intact clpB gene restored a lower sensitivity to 50°C, comparable to the results obtained with the wild type (Fig. 2). In contrast, a clpA mutant of B. suis (4) behaved like the wild type, and the decrease in viability of the clpAB mutant was comparable to that of the clpB mutant (not shown). The clpAB double mutant was obtained from a clpB null mutant in which clpA was inactivated in addition as described recently (4), but using a chloramphenicol resistance gene as the selection marker (25). This second inactivation was verified using polyclonal anti-ClpA antiserum (4).

FIG. 2.

High-temperature survival at 50°C of wild-type B. suis 1330 with plasmid pBBR1MCS (●), the clpB mutant containing pBBR1MCS (○), and the mutant complemented in trans by clpB on plasmid pBBR1MCS (▾) in TS broth at 0, 2, and 4 h postinoculation. Experiments were performed three times in duplicate, and results represent means ± standard deviations (SD). Asterisks indicate significant differences between the clpB mutant and the other two strains (P < 0.001).

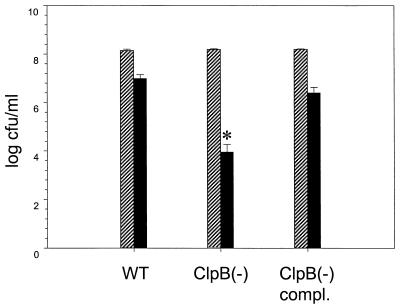

Members of the HSP100 proteins have also been reported to be involved in the ethanol-induced stress response in Bacillus subtilis and Saccharomyces cerevisiae (14, 27). To address this point for ClpB, B. suis from a stationary-phase culture was diluted 100-fold in TS supplemented with ethanol and incubated at 37°C for 6 h prior to plating of serial dilutions onto TS agar. In B. suis, ClpB participated in resistance to ethanol stress, as the clpB mutant showed a 1,000-fold decrease over the incubation period in 10% (vol/vol) ethanol, compared to the wild-type strain (Fig. 3). The minimal effective ethanol concentration was determined to be 8%. In the complemented mutant, in contrast, resistance to ethanol was restored and not significantly different from that measured for the wild-type strain. The clpAB mutant behaved like the clpB mutant, and no role could be assigned to ClpA during ethanol stress (not shown).

FIG. 3.

Effect of ethanol at a final concentration of 10% (vol/vol) on survival of the B. suis wild type (WT), the clpB null mutant (ClpB−) containing pBBR1MCS, and the null mutant complemented with clpB cloned into pBBR1MCS (ClpB- compl.) in TS broth at 0 h (hatched bars) and 6 h (solid bars) postinoculation. Experiments were performed three times in duplicate. Error bars indicate SD. The value marked by an asterisk was significantly different from the others (P < 0.001).

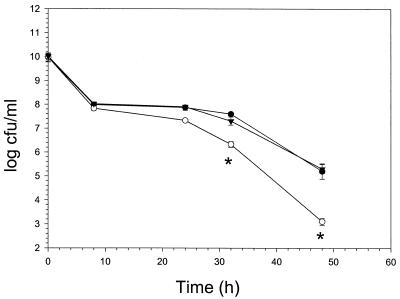

Acid pH as a stress factor may be encountered by brucellae upon their entry into the host organism via the oral route. To study the effect of acid pH stress, a stationary-phase culture of B. suis was diluted 100-fold in TS broth adjusted to pH 4.0 with citric acid (2 M) and incubated at 37°C for up to 48 h. Samples were plated on TS agar to determine the concentration of viable bacteria at the time points indicated. We noticed a 100-fold initial decrease in viability for all strains within 8 h of inoculation. Between 8 and 48 h, the clpB mutant showed an additional 105-fold decrease, compared to a less than 103-fold decrease for the wild type and the complemented strain (Fig. 4).

FIG. 4.

Effect of acid pH on long-term survival of wild-type B. suis 1330 with plasmid pBBR1MCS (●), the clpB mutant containing pBBR1MCS (○), and the mutant complemented in trans by clpB on plasmid pBBR1MCS (▾) in TS broth adjusted to pH 4.0. Experiments were performed four times, and results represent means ± SD. Asterisks indicate significant differences between the clpB mutant and the other two strains at 32 and 48 h (P < 0.00001).

clpAB double mutant of B. suis is sensitive to oxidative stress.

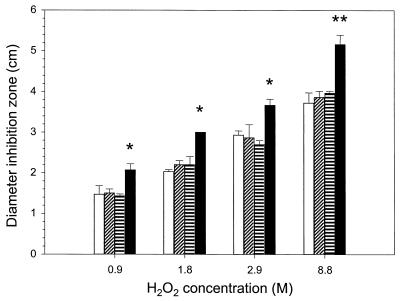

Because of reports that Clp proteins play a role in oxidative stress response (26), we investigated the role of ClpB in resistance to increasing concentrations of H2O2. Disk assays were performed as follows: 75 μl of B. suis cultures adjusted to an optical density of 0.2 were plated on TS agar, and sterile 6-mm paper disks saturated with 10 μl of H2O2 at concentrations ranging between 0.9 and 8.8 M were layered on top prior to incubation at 37°C for 2 days and measurement of inhibition zone diameters. The single-gene null mutants clpB and clpA were not more sensitive to H2O2 than the wild type, but a clpAB double mutant showed increased sensitivity (Fig. 5). Both Clp ATPases probably participated in the oxidative stress response and could substitute for each other.

FIG. 5.

Sensitivity of wild-type B. suis 1330 (open bars), the clpA mutant (hatched bars), the clpB mutant (striped bars), and the clpAB double mutant (solid bars) to various concentrations of H2O2. Disk assays were performed three times in triplicate; error bars indicate SD. At each concentration, the values represented by the solid bars were significantly different from the others (∗, P < 0.05; ∗∗, P < 0.01).

ClpA but not ClpB participates in stress-dependent GFP degradation in vivo.

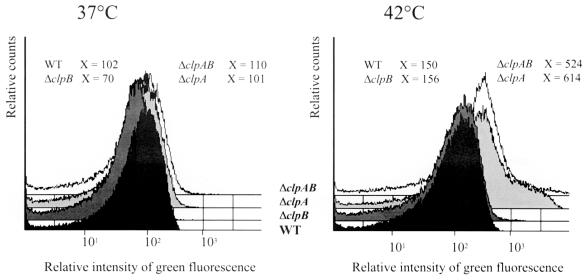

It has been shown recently that the protease ClpP of L. monocytogenes contributes to stress-dependent degradation of the model foreign protein green fluorescent protein (GFP) (7). In E. coli, the proteolytic activity of ClpP is dependent on the formation of a complex with ClpA (18). Following our observation that ClpA of B. suis can functionally replace ClpA of E. coli (4), we investigated whether ClpA or ClpB of B. suis participates in protein degradation in vivo. The B. suis wild type and ΔclpA, ΔclpB, and ΔclpAB mutants were transformed with plasmid pBBR1-GFP-SOG, carrying a strong constitutive B. suis promoter fused to gfp, resulting in fluorescent bacteria (21). The fluorescence intensity of each strain was determined by flow cytometry at 37 and 42°C (the maximum temperature for growth of the ΔclpA and ΔclpAB mutants), and unlabeled strains were used as controls. Bacteria were grown to an OD600 of approximately 1.0 in TS broth at 37 or 42°C. GFP expression was monitored after excitation at 488 nm using a FACSCalibur flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson). Bacteria were electronically gated, and a total of 50,000 bacteria per sample were analyzed using CellQuest software. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov two-sample test included in the software was used for statistical analysis. The experiments were performed three times for all strains. Fluorescence intensity was similar for all strains grown at 37°C, but at 42°C wild-type B. suis was fourfold less fluorescent than the ΔclpA mutant (Fig. 6), and hence significantly different (P < 0.001). A similar difference was observed between the wild type and the ΔclpAB mutant (P < 0.001), whereas the ΔclpB mutant behaved like the wild-type strain. These results suggested that ClpA participated in the degradation of a foreign protein under high-temperature stress conditions in B. suis and that ClpB was not involved in this activity.

FIG. 6.

Flow cytometry analysis of GFP expression in wild-type B. suis 1330 (WT; black histograms) and in the ΔclpB (dark grey), ΔclpA (light grey), and ΔclpAB (white) null mutants transformed with plasmid pBBR1-GFP-SOG. The X values indicate mean relative fluorescence intensities for the strains at 37°C (left) and at 42°C (right). Experiments were performed three times, and one representative experiment is shown.

Conclusions.

The participation of ClpB proteins in response to stress has been investigated (1, 27, 31, 32), and the demonstration that ClpB interacts with DnaK, DnaJ, and GrpE in suppressing and reversing protein aggregation by the formation of a bichaperone system in vitro (8, 19, 20, 36) represents an important contribution to the understanding of the unique role of ClpB in thermotolerance and stress recovery. The ΔclpB B. suis cells were rapidly killed at 50°C, as has been shown previously for E. coli (33) and Helicobacter pylori (1), hence establishing for B. suis the vital role of ClpB in stress recovery. Nevertheless, the genetic elements participating in this stress response have not been identified, and from the recent publication of a ς32 consensus sequence for B. abortus (25), we could not detect a −35 or a −10 region typical of heat shock promoters preceding the clpB coding sequence. Acid pH is a second stress factor, and our results showed the induction of an adaptive acid tolerance response during the first 8 h, as previously reported (15). Survival of the clpB null mutant continued to drop over the next 24 h, and ClpB therefore appeared to be involved in this tolerance response. In brucellae, ethanol and acid pH may be signals sensed and transduced by two-component systems, but very little is known about this subject yet. In contrast to our earlier results with ClpA (4), overexpression of clpB restored the wild-type phenotype for the various stress conditions studied. An excess of ClpB obviously did not affect the postulated interaction of this chaperone with the DnaK-DnaJ-GrpE system.

During oxidative stress, only simultaneous inactivation of both clpA and clpB resulted in increased sensitivity of B. suis to various concentrations of hydrogen peroxide. ClpA and ClpB have in common that their functions contribute to the elimination of damaged or aggregated proteins. Studies performed in vitro with these Clp ATPases from E. coli revealed that the mechanisms involved are nevertheless different. ClpA is part of the two-component protease ClpAP, and it binds protein substrates and presents them to the protease ClpP for degradation. ClpB participates in suppression and reversion of protein aggregation. It is conceivable that the accumulation of damaged proteins is the event leading to increased sensitivity of B. suis clpAB null mutants to H2O2 and that the reduction in the concentration of altered proteins by degradation or refolding increases resistance to this specific stress.

Flow cytometry experiments presented here led to the conclusion that the Clp ATPase ClpB cannot replace ClpA in its role in protein degradation in B. suis. The higher fluorescence intensity measured in the isogenic clpA and clpAB mutants was obviously due to the absence of ClpA. Three recent publications were of great interest for the interpretation of our results. (i) A similar shift in fluorescence was described following inactivation of the protease ClpP in L. monocytogenes (7). (ii) In vitro experiments showed that E. coli ClpA can bind unfolded GFP and that the complex ClpAP can degrade unfolded GFP but not native GFP (10). (iii) ClpX, in contrast, which also presents substrates for degradation to ClpP, cannot trap unfolded substrates unless they have a specific binding motif (29). We concluded that at 42°C, GFP molecules that were sufficiently unfolded in B. suis probably allowed specific binding by ClpA and presentation to ClpP in vivo, resulting in degradation of the substrate in the wild type and in the clpB null mutant.

We have characterized the important role of the ClpB homolog of B. suis in response to several environmental and in vitro stresses. The inactivation of clpB of B. suis demonstrated that, in this organism, a single protein was responsible for tolerance to heat, ethanol, and acid pH, adding proof to the hypothesis that the molecular causes of lethality are similar in very different environmental circumstances. The possible participation of ClpB in resistance of the pathogen B. suis to host defense mechanisms remains to be determined.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The nucleotide sequence of B. suis clpB has been submitted to the GenBank database (accession number AJ251205).

Acknowledgments

We thank C. H. Chung for his generous gift of anti-E. coli ClpB antiserum and M. T. Alvarez-Martinez for help with the computer software.

This work was supported in part by grant QLK2-CT-1999-00014 from the European Union.

REFERENCES

- 1.Allan E, Mullany P, Tabaqchali S. Construction and characterization of a Helicobacter pylori clpB mutant and role of the gene in the stress response. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:426–429. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.2.426-429.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Corbel M J. Brucella. In: Parker M T, Collier L H, editors. Principles of bacteriology, virology, and immunity. 2. E. London, U.K: Arnold; 1990. pp. 339–353. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Donnenberg M S, Kaper J B. Construction of an eae deletion mutant of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli by using a positive-selection suicide vector. Infect Immun. 1991;59:4310–4317. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.12.4310-4317.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ekaza E, Guilloteau L, Teyssier J, Liautard J P, Köhler S. Functional analysis of the ClpATPase ClpA of Brucella suis, and persistence of a knockout mutant in BALB/c mice. Microbiology. 2000;146:1605–1616. doi: 10.1099/00221287-146-7-1605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Elzer P H, Phillips R W, Kovach M E, Peterson K M, Roop R M., II Characterization and genetic complementation of a Brucella abortus high-temperature requirement A (htrA) deletion mutant. Infect Immun. 1994;62:4135–4139. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.10.4135-4139.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fleischmann R D, Adams M D, White O, Clayton R A, Kirkness E F, Kerlavage A R, Bult C J, Tomb J F, Dougherty B A, Merrick J M, et al. Whole-genome random sequencing and assembly of Haemophilus influenzae Rd. Science. 1995;269:496–512. doi: 10.1126/science.7542800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gaillot O, Pellegrini E, Bregenholt S, Nair S, Berche P. The ClpP serine protease is essential for the intracellular parasitism and virulence of Listeria monocytogenes. Mol Microbiol. 2000;35:1286–1294. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.01773.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goloubinoff P, Mogk A, Zvi A P B, Tomoyasu T, Bukau B. Sequential mechanism of solubilization and refolding of stable protein aggregates by a bichaperone network. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:13732–13737. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.24.13732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gottesman S, Squires C, Pichersky E, Carrington M, Hobbs M, Mattick J S, Dalrymple B, Kuramitsu H, Shiroza T, Foster T, Clark W P, Ross B, Squires C L, Maurizi M R. Conservation of the regulatory subunit for the Clp ATP-dependent protease in prokaryotes and eukaryotes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:3513–3517. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.9.3513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hoskins J R, Singh S K, Maurizi M R, Wickner S. Protein binding and unfolding by the chaperone ClpA and degradation by the protease ClpAP. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:8892–8897. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.16.8892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kitagawa M, Wada C, Yoshioka S, Yura T. Expression of ClpB, an analog of the ATP-dependent protease regulatory subunit in Escherichia coli, is controlled by a heat shock ς factor (ς32) J Bacteriol. 1991;173:4247–4253. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.14.4247-4253.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Köhler S, Teyssier J, Cloeckaert A, Rouot B, Liautard J P. Participation of the molecular chaperone DnaK in intracellular growth of Brucella suis within U937-derived phagocytes. Mol Microbiol. 1996;20:701–712. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1996.tb02510.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kovach M E, Phillips R W, Elzer P H, Roop II R M, Peterson K M. pBBR1MCS: a broad-host-range cloning vector. BioTechniques. 1994;16:800–802. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Krüger E, Völker U, Hecker M. Stress induction of clpC in Bacillus subtilis and its involvement in stress tolerance. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:3360–3367. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.11.3360-3367.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kulakov Y K, Guigue-Talet P G, Ramuz M R, O'Callaghan D. Response of Brucella suis 1330 and B. canis RM6/66 to growth at acid pH and induction of an adaptive acid tolerance response. Res Microbiol. 1997;148:145–151. doi: 10.1016/S0923-2508(97)87645-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lin J, Adams L G, Ficht T A. Characterization of the heat shock response in Brucella abortus and isolation of the genes encoding the GroE heat shock proteins. Infect Immun. 1992;60:2425–2431. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.6.2425-2431.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lin J, Ficht T A. Protein synthesis in Brucella abortus induced during macrophage infection. Infect Immun. 1995;63:1409–1414. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.4.1409-1414.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Maurizi M R, Clark W P, Katayama Y, Rudikoff S, Pumphrey J, Bowers B, Gottesman S. Sequence and structure of ClpP, the proteolytic component of the ATP-dependent Clp protease of Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:12536–12545. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mogk A, Tomoyasu T, Goloubinoff P, Rüdiger S, Röder D, Langen H, Bukau B. Identification of thermolabile Escherichia coli proteins: prevention and reversion of aggregation by DnaK and ClpB. EMBO J. 1999;18:6934–6949. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.24.6934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Motohashi K, Watanabe Y, Yohda M, Yoshida M. Heat-inactivated proteins are rescued by the DnaK.J-GrpE set and ClpB chaperones. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:7184–7189. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.13.7184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ouahrani-Bettache S, Porte F, Teyssier J, Liautard J P, Köhler S. pBBR1-GFP: A broad-host-range vector for prokaryotic promoter studies. BioTechniques. 1999;26:620–622. doi: 10.2144/99264bm05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pearson W R, Lipman D J. Improved tools for biological sequence analysis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:2444–2448. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.8.2444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Porte F, Liautard J P, Köhler S. Early acidification of phagosomes containing Brucella suis is essential for intracellular survival in murine macrophages. Infect Immun. 1999;67:4041–4047. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.8.4041-4047.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rafie-Kolpin M, Essenberg R C, Wyckoff J H., III Identification and comparison of macrophage-induced proteins and proteins induced under various stress conditions in Brucella abortus. Infect Immun. 1996;64:5274–5283. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.12.5274-5283.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Robertson G T, Kovach M E, Allen C A, Ficht T A, Roop R M., II The Brucella abortus Lon functions as a generalized stress response protease and is required for wild-type virulence in BALB/c mice. Mol Microbiol. 2000;35:577–588. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.01726.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rouquette C, Ripio M-T, Pellegrini E, Bolla J-M, Tascon R I, Vazquez-Boland J-A, Berche P. Identification of a ClpC ATPase required for stress tolerance and in vivo survival of Listeria monocytogenes. Mol Microbiol. 1996;21:977–987. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.641432.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sanchez Y, Taulien J, Borkovich K A, Lindquist S. Hsp104 is required for tolerance to many forms of stress. EMBO J. 1992;11:2357–2364. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05295.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schirmer E C, Glover J R, Singer M A, Lindquist S. HSP100/Clp proteins: a common mechanism explains diverse functions. Trends Biochem Sci. 1996;21:289–296. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Singh S K, Grimaud R, Hoskins J R, Wickner S, Maurizi M R. Unfolding and internalization of proteins by the ATP-dependent proteases ClpXP and ClpAP. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:8898–8903. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.16.8898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Smith C K, Baker T A, Sauer R T. Lon and Clp family proteases and chaperones share homologous substrate-recognition domains. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:6678–6682. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.12.6678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Squires C, Squires C L. The Clp proteins: proteolysis regulators or molecular chaperones? J Bacteriol. 1992;174:1081–1085. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.4.1081-1085.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Squires C L, Pedersen S, Ross B M, Squires C. ClpB is the Escherichia coli heat shock protein F84.1. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:4254–4262. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.14.4254-4262.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Thomas J G, Baneyx F. Roles of the Escherichia coli small heat shock proteins IbpA and IbpB in thermal stress management: comparison with ClpA, ClpB, and HtpG in vivo. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:5165–5172. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.19.5165-5172.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Thompson J D, Higgins D G, Gibson T J. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, positions-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:4673–4680. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Woo K M, Kim K I, Goldberg A L, Ha D B, Chung C H. The heat-shock protein ClpB in Escherichia coli is a protein-activated ATPase. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:20429–20434. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zolkiewski M. ClpB cooperates with DnaK, DnaJ, and GrpE in suppressing protein aggregation. A novel multi-chaperone system from Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:28083–28086. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.40.28083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]