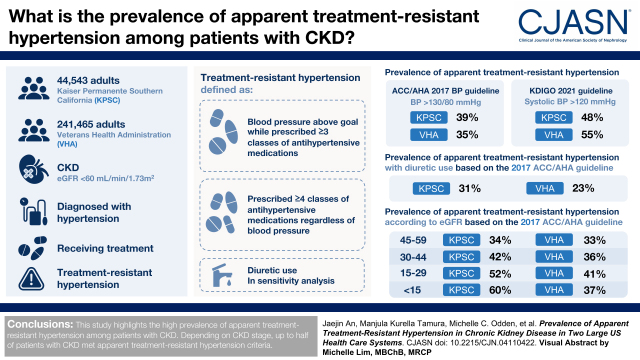

Visual Abstract

Keywords: chronic kidney disease, prevalence, hypertension, delivery of health care

Abstract

Background and objectives

More intensive BP goals have been recommended for patients with CKD. We estimated the prevalence of apparent treatment-resistant hypertension among patients with CKD according to the 2017 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association (ACC/AHA; BP goal <130/80 mm Hg) and 2021 Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO; systolic BP <120 mm Hg) guidelines in two US health care systems.

Design, setting, participants, & measurements

We included adults with CKD (an eGFR <60 ml/min per 1.73 m2) and treated hypertension from Kaiser Permanente Southern California and the Veterans Health Administration. Using electronic health records, we identified apparent treatment-resistant hypertension on the basis of (1) BP above the goal while prescribed three or more classes of antihypertensive medications or (2) prescribed four or more classes of antihypertensive medications regardless of BP. In a sensitivity analysis, we required diuretic use to be classified as apparent treatment-resistant hypertension. We estimated the prevalence of apparent treatment-resistant hypertension per clinical guideline and by CKD stage.

Results

Among 44,543 Kaiser Permanente Southern California and 241,465 Veterans Health Administration patients with CKD and treated hypertension, the prevalence rates of apparent treatment-resistant hypertension were 39% (Kaiser Permanente Southern California) and 35% (Veterans Health Administration) per the 2017 ACC/AHA guideline and 48% (Kaiser Permanente Southern California) and 55% (Veterans Health Administration) per the 2021 KDIGO guideline. By requiring a diuretic as a criterion for apparent treatment-resistant hypertension, the prevalence rates of apparent treatment-resistant hypertension were lowered to 31% (Kaiser Permanente Southern California) and 23% (Veterans Health Administration) per the 2017 ACC/AHA guideline. The prevalence rates of apparent treatment-resistant hypertension were progressively higher at more advanced stages of CKD (34%/33%, 42%/36%, 52%/41%, and 60%/37% for Kaiser Permanente Southern California/Veterans Health Administration eGFR 45–59, 30–44, 15–29, and <15 ml/min per 1.73 m2, respectively) per the 2017 ACC/AHA guideline.

Conclusions

Depending on the CKD stage, up to a half of patients with CKD met apparent treatment-resistant hypertension criteria.

Introduction

Resistant hypertension is common in patients with CKD (1,2), and it is associated with a higher risk of cardiovascular events and kidney disease progression (2,3). Despite its clinical importance, the identification and management of resistant hypertension in CKD have been challenging due to inaccurate BP measurement, poor recognition of secondary causes of resistant hypertension in CKD, and patient-level barriers, including nonadherence to antihypertensive drug regimens (4). The term apparent treatment-resistant hypertension is commonly used in the literature to reflect the difficulty of distinguishing resistant hypertension from pseudoresistance in population-based studies (5).

Recently, more intensive BP goals have been recommended for patients with CKD. The 2017 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) BP guideline recommended a BP goal of <130/80 mm Hg for most patients with hypertension (6). The 2021 Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) guideline recommended a lower systolic BP target of <120 mm Hg for the CKD population (7,8). Most resistant hypertension or apparent treatment-resistant hypertension prevalence studies have been on the basis of a historical general population BP goal of <140/90 mm Hg, even though the BP goal for CKD was <140/90 mm Hg prior to the 2017 ACC/AHA guideline. Few studies have examined apparent treatment-resistant hypertension in the CKD population (1,2). A better understanding of the implications of updated BP goals and the patterns of antihypertensive use in real-world populations with CKD could highlight opportunities to improve BP management in this population.

Using data from two large US health care systems, we estimated the prevalence of apparent treatment-resistant hypertension according to the 2017 ACC/AHA and the 2021 KDIGO guidelines and stratified by CKD stage among patients with CKD and treated hypertension. We also investigated patient characteristics and antihypertensive medication use among patients with CKD and apparent treatment-resistant hypertension.

Materials and Methods

Study Cohort

We used electronic health records from Kaiser Permanente Southern California and the Veterans Health Administration to identify the study populations. Inclusion criteria were adults ≥18 years with CKD and treated hypertension (at least two antihypertensive prescriptions and a hypertension diagnosis) between July 1, 2014 and June 30, 2015 from Kaiser Permanente Southern California and between January 1, 2018 and December 31, 2018 from the Veterans Health Administration. The first date of a hypertension diagnosis code during the observation window constituted the index date. We required individuals to have continuous enrollment for 12 months prior to and 12 months following the index date. We used the 12-month period prior to the index to identify clinical characteristics and the 12-month period following the index date to determine medication use and BP levels for apparent treatment-resistant hypertension identification. We required having at least one BP measure during the 12-month period following the index date. CKD was defined as an eGFR of <60 ml/min per 1.73 m2 on two separate days at least 90 days apart using the 2009 Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration equation (9). To define CKD stage, we used the most proximal eGFR prior to the index date. We excluded patients who were treated with dialysis or kidney transplant or had secondary hypertension, such as renovascular disease, adrenal disorders, Cushing syndrome, or aortic coarctation. The study adhered to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Kaiser Permanente Southern California and Veterans Health Administration institutional review committees. Patient informed consent was waived.

Using pharmacy databases, we defined concomitant antihypertensive medication use as an overlap of 7 days or more in days supplied for different classes of medications. We used the BP measurements from the first outpatient visit encounter after exposure to greater than or equal to three classes of antihypertensive medications over the observation window to determine apparent treatment-resistant hypertension status. Both Kaiser Permanente Southern California and the Veterans Health Administration use a standardized approach to measure office BP. Thus, BP measurement methodologies were consistent within each health care system (10,11). When multiple BP measurements were present in a single outpatient visit, we selected the lowest BP for analysis to minimize the white coat effect.

Apparent Treatment-Resistant Hypertension

We defined apparent treatment-resistant hypertension as (1) BP above the goal while prescribed greater than or equal to three classes of antihypertensive medications or (2) prescribed greater than or equal to four classes of antihypertensive medications regardless of BP. Patients with apparent treatment-resistant hypertension were further subdivided into three categories: controlled resistant hypertension (BP at the goal while on greater than or equal to four medications), uncontrolled resistant hypertension (BP above the goal while on three to four medications), and refractory hypertension (BP above the goal while on greater than or equal to five medications). Patients with BP level at the goal while on three or fewer antihypertensive medications were categorized as nonapparent treatment-resistant hypertension. In a sensitivity analysis, we required diuretic use to be classified as apparent treatment-resistant hypertension.

We used systolic BP <130 mm Hg and diastolic BP <80 mm Hg as the BP goal per the 2017 ACC/AHA guideline as a primary analysis. We also estimated the prevalence of apparent treatment-resistant hypertension after applying the BP goal of systolic BP <120 mm Hg per the 2021 KDIGO guideline and the historical general population BP goal of systolic BP <140 mm Hg and diastolic BP <90 mm Hg.

Statistical Analyses

We estimated the prevalence of apparent treatment-resistant hypertension and subcategories of apparent treatment-resistant hypertension (controlled resistant hypertension, uncontrolled resistant hypertension, and refractory hypertension) per each clinical guideline. The age-, sex-, and race- and ethnicity-adjusted prevalence was estimated as a sensitivity analysis. Missing values in race and ethnicity were combined with other or multirace groups.

We estimated the prevalence of apparent treatment-resistant hypertension by CKD stage (eGFR of 45–59, 30–44, 15–29, or <15 ml/min per 1.73 m2). The age-, sex-, and race- and ethnicity-adjusted prevalence as well as the adjusted prevalence ratios (95% confidence intervals [95% CIs]) using eGFR of 45–59 ml/min per 1.73 m2 as a reference group were investigated.

We also characterized antihypertensive medication use for patients at the time of meeting apparent treatment-resistant hypertension criteria. For patients with nonapparent treatment-resistant hypertension, we evaluated the initial antihypertensive therapy after the index date.

Descriptive statistics (percentages, mean/SD, and median/quartile 1, quartile 3) and multivariable logistic and Poisson regression analyses were used for the analysis. Analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC) and Stata version 15 (StataCorp LLC, College Station, TX).

Results

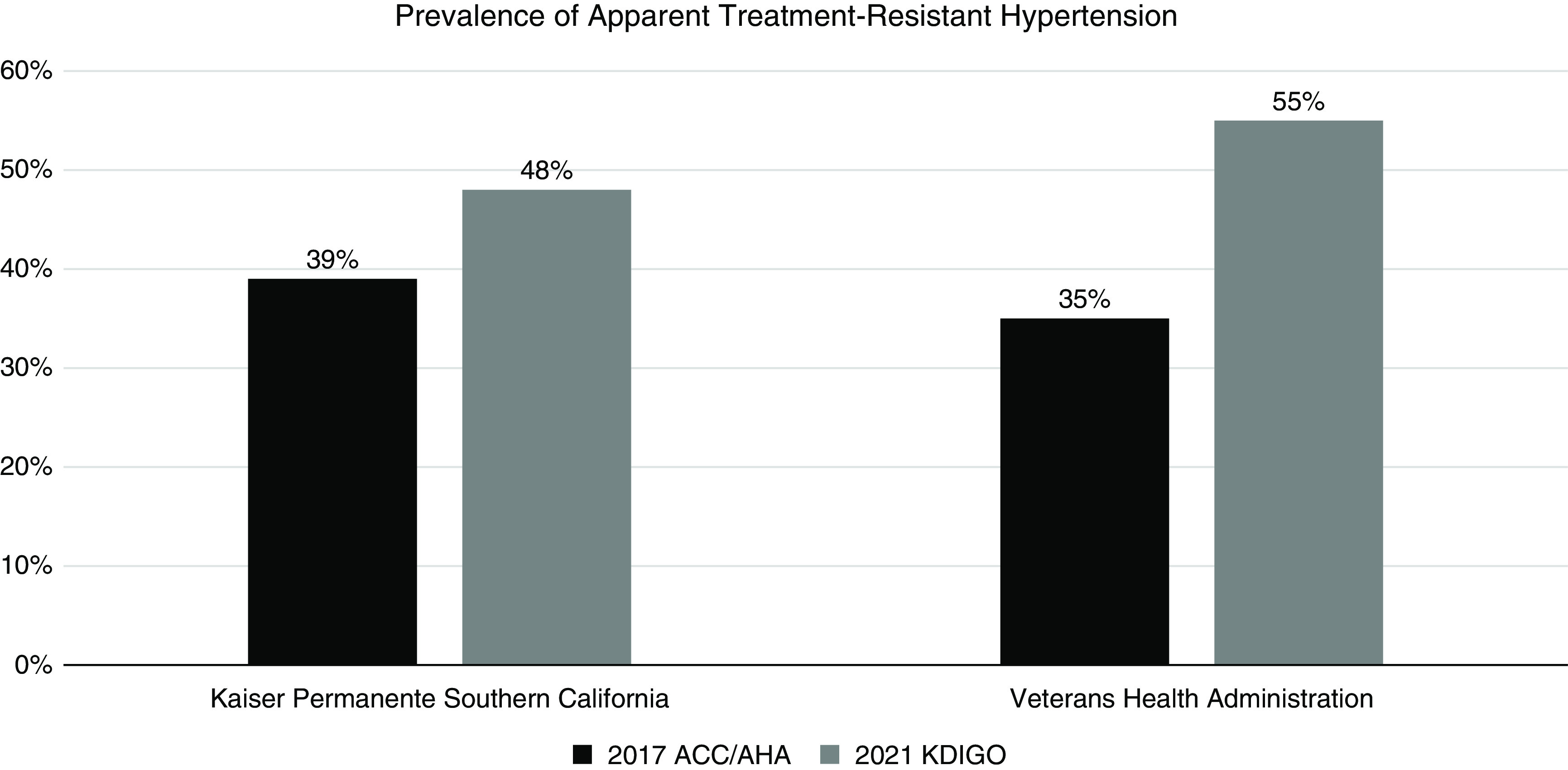

We identified a total of 44,543 patients from Kaiser Permanente Southern California and 241,465 patients from the Veterans Health Administration who had CKD and treated hypertension. The prevalence rates of apparent treatment-resistant hypertension were estimated to be 39% and 35% in the Kaiser Permanente Southern California and Veterans Health Administration populations, respectively, according to the 2017 ACC/AHA guideline (Figure 1). When applying the 2021 KDIGO guideline, the prevalence rates of apparent treatment-resistant hypertension were 48% and 55% in Kaiser Permanente Southern California and the Veterans Health Administration, respectively.

Figure 1.

Prevalence of apparent treatment-resistant hypertension according to the 2017 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) and 2021 Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) guidelines.

Applying the 2017 ACC/AHA guideline, the prevalence rates of refractory hypertension, uncontrolled resistant hypertension, and controlled resistant hypertension were 3%, 28%, and 9% in Kaiser Permanente Southern California, respectively, and 1%, 29%, and 5% in the Veterans Health Administration, respectively (Table 1). The refractory hypertension, uncontrolled resistant hypertension, and controlled resistant hypertension groups all had a higher population of non-Hispanic Black patients as well as patients with severe obesity (body mass index ≥35 kg/m2), heart failure, diabetes, and sleep apnea compared with the nonapparent treatment-resistant hypertension group (Table 1).

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics for patients with CKD with or without apparent treatment-resistant hypertension according to the 2017 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association BP guideline

| Characteristics | Kaiser Permanente Southern California | Veterans Health Administration | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Refractory Hypertension | Uncontrolled Resistant Hypertension | Controlled Resistant Hypertension | Nonapparent Treatment-Resistant Hypertension | Refractory Hypertension | Uncontrolled Resistant Hypertension | Controlled Resistant Hypertension | Nonapparent Treatment-Resistant Hypertension | |

| Patients, N (row %) | 1143 (3) | 12,604 (28) | 3836 (9) | 26,960 (61) | 3471 (1) | 70,345 (29) | 11,140 (5) | 156,509 (65) |

| Demographic characteristics | ||||||||

| Age, yr at index, mean (SD) | 73 (10) | 75 (10) | 75 (9) | 76 (10) | 72 (9) | 73 (9) | 74 (9) | 74 (9) |

| Men, N (column %) | 573 (50) | 5290 (42) | 2021 (53) | 12,294 (46) | 3423 (99) | 68,225 (97) | 10,935 (98) | 151,214 (97) |

| Race and ethnicity, N (column %) | ||||||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 475 (42) | 6131 (49) | 1884 (49) | 15,414 (57) | 1924 (55) | 45,582 (65) | 7671 (69) | 111,431 (71) |

| Hispanic | 267 (23) | 2908 (23) | 830 (22) | 5667 (21) | 212 (6) | 4282 (6) | 601 (5) | 8461 (5) |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 267 (23) | 2164 (17) | 693 (18) | 2786 (10) | 1076 (31) | 15,351 (22) | 2084 (19) | 25,270 (16) |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 115 (10) | 1241 (10) | 378 (10) | 2729 (10) | 15 (0.4) | 504 (0.7) | 73 (0.7) | 1122 (0.7) |

| Native American/Alaskan | 1 (0.1) | 20 (0.2) | 4 (0.1) | 44 (0.2) | 8 (0.2) | 164 (0.2) | 19 (0.2) | 341 (0.2) |

| Other/multirace/unknown | 18 (2) | 140 (1) | 47 (1) | 320 (1) | 236 (7) | 4462 (6) | 692 (6) | 9884 (6) |

| Clinical characteristics | ||||||||

| Systolic BP, mm Hg, mean (SD) | 134 (16) | 132 (14) | 124 (14) | 125 (14) | 143 (19) | 140 (17) | 120 (16) | 129 (18) |

| Diastolic BP, mm Hg, mean (SD) | 65 (11) | 67 (11) | 63 (10) | 66 (10) | 75 (12) | 75 (11) | 67 (10) | 72 (11) |

| Body mass index, mean (SD) | 33 (8) | 31 (7) | 31 (7) | 29 (6) | 33 (7) | 31 (6) | 32 (7) | 31 (6) |

| Body mass index category, kg/m2, N (column %) | ||||||||

| <25 | 152 (13) | 2503 (20) | 667 (17) | 7220 (27) | 366 (11) | 9515 (14) | 1356 (12) | 25,580 (16) |

| 25–29.9 | 312 (27) | 4154 (33) | 1268 (33) | 9762 (36) | 862 (25) | 20,459 (29) | 2943 (26) | 48,191 (31) |

| 30–34.9 | 281 (25) | 3150 (25) | 974 (25) | 5859 (22) | 938 (27) | 18,549 (26) | 2962 (27) | 38,374 (25) |

| ≥35 | 390 (34) | 2760 (22) | 916 (24) | 3986 (15) | 1052 (30) | 16,181 (23) | 3036 (27) | 29,408 (19) |

| Missing | 8 (0.7) | 37 (0.3) | 11 (0.3) | 133 (0.5) | 253 (7) | 5641 (8) | 843 (8) | 14,956 (10) |

| Comorbidities, N (column %) | ||||||||

| Heart failure | 195 (17) | 1507 (12) | 766 (20) | 2393 (9) | 594 (17) | 7892 (11) | 2398 (22) | 14,504 (9) |

| Peripheral arterial disease | 57 (5) | 518 (4) | 193 (5) | 982 (4) | 365 (11) | 6766 (10) | 1227 (11) | 12,977 (8) |

| Ischemic heart disease | 34 (3) | 245 (2) | 74 (2) | 414 (2) | 173 (5) | 2270 (3) | 556 (5) | 3936 (3) |

| Diabetes | 847 (74) | 7151 (57) | 2371 (62) | 11,624 (43) | 2484 (72) | 44,699 (64) | 7516 (68) | 88,033 (56) |

| Sleep apnea | 152 (13) | 998 (8) | 434 (11) | 1672 (6) | 937 (27) | 14,640 (21) | 2879 (26) | 27,801 (18) |

| Dementia | 8 (0.7) | 151 (1) | 53 (1) | 524 (2) | 71 (2) | 1661 (2) | 267 (2) | 3727 (2) |

| Cerebrovascular accident | 15 (1) | 141 (1) | 42 (1) | 218 (0.8) | 34 (1) | 521 (0.7) | 89 (0.8) | 852 (0.5) |

| eGFR, ml/min per 1.73 m2, mean (SD) | 37 (13) | 41 (12) | 40 (12) | 44 (11) | 40 (15) | 42 (14) | 42 (13) | 44 (13) |

| Urine albumin-creatinine ratio, median (Q1, Q3) | 171 (24, 975) | 60 (14, 432) | 41 (11, 240) | 24 (8, 107) | 110 (24, 512) | 65 (17, 316) | 41 (12, 171) | 36 (11, 147) |

| Missing, N (column %) | 149 (13) | 2898 (23) | 756 (20) | 8510 (32) | 2161 (0.9) | 44,302 (18) | 7009 (3) | 102,557 (43) |

Q, quartile.

By requiring a diuretic as one of the criteria for apparent treatment-resistant hypertension, the prevalence rates of apparent treatment-resistant hypertension were 31% and 23% for Kaiser Permanente Southern California and the Veterans Health Administration, respectively, using the 2017 ACC/AHA guideline (Table 2). Crude and age-, sex-, and race- and ethnicity-adjusted prevalence estimates were mostly identical (Supplemental Table 1).

Table 2.

Prevalence of apparent treatment-resistant hypertension before and after requiring a diuretic to define apparent treatment-resistant hypertension applying different clinical guidelines

| Clinical Guidelines | Kaiser Permanente Southern California, n=44,543 | Veterans Health Administration, n=241,465 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before Requiring a Diuretic | After Requiring a Diuretic | Before Requiring a Diuretic | After Requiring a Diuretic | |

| 2017 ACC/AHA BP goal <130/80 mm Hg, N (%) | ||||

| Apparent treatment- resistant hypertension | 17,583 (39) | 13,937 (31) | 84,956 (35) | 56,358 (23) |

| Refractory hypertension | 1143 (3) | 1097 (2) | 3471 (1) | 3193 (1) |

| Uncontrolled resistant hypertension | 12,604 (28) | 9310 (21) | 70,345 (29) | 43,643 (18) |

| Controlled resistant hypertension | 3836 (9) | 3530 (8) | 11,140 (5) | 9522 (4) |

| Nonapparent treatment- resistant hypertension | 26,960 (61) | 30,606 (69) | 156,509 (65) | 185,107 (77) |

| 2021 KDIGO systolic BP goal <120 mm Hg, N (%) | ||||

| Apparent treatment- resistant hypertension | 21,386 (48) | 16,717 (38) | 133,284 (55) | 86,910 (36) |

| Refractory hypertension | 1549 (3) | 1487 (3) | 5214 (2) | 4790 (2) |

| Uncontrolled resistant hypertension | 17,825 (40) | 13,362 (30) | 119,323 (49) | 74,588 (31) |

| Controlled resistant hypertension | 2012 (5) | 1868 (4) | 8747 (4) | 7532 (3) |

| Nonapparent treatment- resistant hypertension | 23,157 (52) | 27,826 (62) | 108,181 (45) | 154,555 (64) |

ACC/AHA, American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association; KDIGO, Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes.

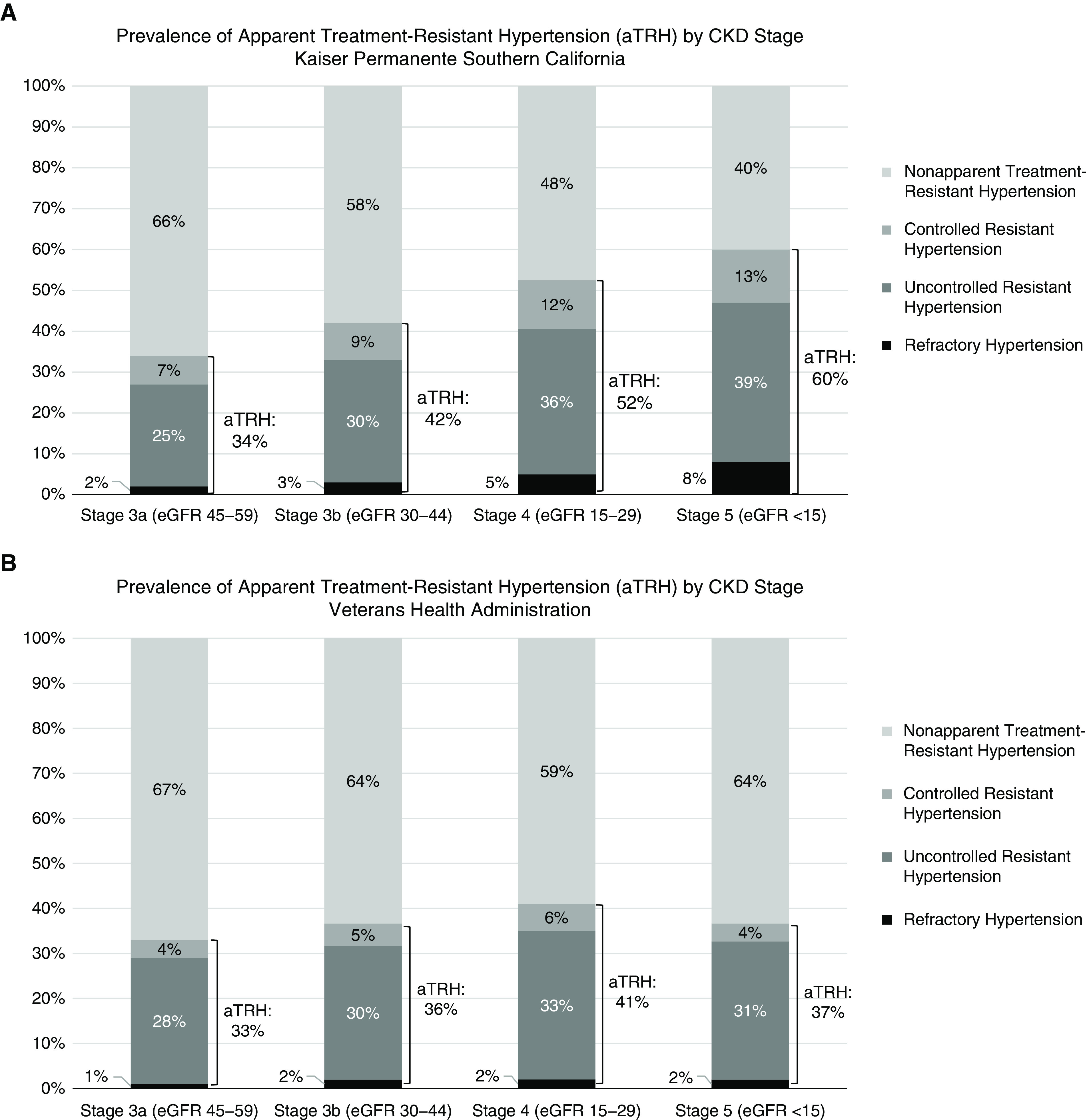

The prevalence of apparent treatment-resistant hypertension was progressively higher at more advanced stages of CKD for both Kaiser Permanente Southern California and the Veterans Health Administration (34%/33%, 42%/36%, 52%/41%, and 60%/37% for Kaiser Permanente Southern California/Veterans Health Administration eGFR of 45–59, 30–44, 15–29, and <15 ml/min per 1.73 m2, respectively) using the 2017 ACC/AHA guideline (Figure 2). The adjusted prevalence ratios (95% CIs) of apparent treatment-resistant hypertension were 1.54 (95% CI, 1.49 to 1.59) and 1.25 (95% CI, 1.23 to 1.27) of eGFR 15–29 ml/min per 1.73 m2 compared with eGFR 45–59 ml/min per 1.73 m2 for Kaiser Permanente Southern California and the Veterans Health Administration, respectively (Table 3).

Figure 2.

Prevalence of apparent treatment-resistant hypertension (aTRH) by CKD stage according to the 2017 AHA/ACC BP guideline. (A) Kaiser Permanente Southern California; (B) Veterans Health Administration.

Table 3.

Crude prevalence; age-, sex-, and race- and ethnicity-adjusted prevalence; and adjusted prevalence ratios (95% confidence intervals) of apparent treatment-resistant hypertension by CKD stage according to the 2017 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association BP guideline

| CKD Stage | Kaiser Permanente Southern California, n=44,543 | Veterans Health Administration, n=241,465 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Crude Prevalence | Adjusteda Prevalence (95% Confidence Interval) | Adjustedb Prevalence Ratio (95% Confidence Interval) | N | Crude Prevalence | Adjusteda Prevalence (95% Confidence Interval) | Adjustedb Prevalence Ratio (95% Confidence Interval) | |

| 3a (eGFR 45–59) | 21,477 | 33.8 (33.1 to 34.4) | 33.7 (33.1 to 34.3) | Reference | 128,435 | 33.2 (32.9 to 33.4) | 33.2 (33.0 to 33.5) | Reference |

| 3b (eGFR 30–44) | 16,640 | 41.7 (40.9 to 42.4) | 41.9 (41.1 to 42.6) | 1.24 (1.21 to 1.27) | 70,257 | 36.3 (35.4 to 36.6) | 36.8 (36.4 to 37.1) | 1.11 (1.09 to 1.12) |

| 4 (eGFR 15–29) | 5698 | 52.0 (50.7 to 53.3) | 51.9 (50.6 to 53.2) | 1.54 (1.49 to 1.59) | 25,374 | 41.1 (40.8 to 42.0) | 41.5 (40.9 to 42.1) | 1.25 (1.23 to 1.27) |

| 5 (eGFR <15) | 728 | 59.8 (56.2 to 63.3) | 57.7 (54.1 to 61.3) | 1.69 (1.58 to 1.79) | 17,399 | 36.5 (35.8 to 37.2) | 34.0 (33.3 to 34.7) | 1.03 (1.00 to 1.05) |

eGFR is in milliliters per minute per 1.73 m2.

Age category (<65, 65–74.9, 75–84.9, or >85 years), sex, and race and ethnicity (non-Hispanic White, Hispanic, non-Hispanic Black, Asian/Pacific Islander, or other races) were adjusted using multivariable logistic regression. Average predicted probabilities from the fitted model were obtained from margins command using Stata.

The same list of covariates was used for the adjusted prevalence ratio using multivariable Poisson regression.

The most frequently used antihypertensive medications were renin-angiotensin system inhibitors, β-blockers, diuretics, and calcium channel blockers across all apparent treatment-resistant hypertension types. Twenty percent or less of patients with refractory hypertension were on mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists in both Kaiser Permanente Southern California and the Veterans Health Administration. The proportions of patients using mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists or thiazide-like diuretics were lower in uncontrolled resistant hypertension (5%–6% for mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists; 30%–43% for thiazide-like diuretics) than in controlled resistant hypertension (15%–20% for mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists; 33%–51% for thiazide-like diuretics) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Antihypertensive medication use for patients with CKD with or without apparent treatment-resistant hypertension according to the 2017 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association BP guideline

| Medication | Kaiser Permanente Southern California | Veterans Health Administration | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Refractory Hypertension | Uncontrolled Resistant Hypertension | Controlled Resistant Hypertension | Nonapparent Treatment-Resistant Hypertension | Refractory Hypertension | Uncontrolled Resistant Hypertension | Controlled Resistant Hypertension | Nonapparent Treatment-Resistant Hypertension | |

| Patients, N | 1143 | 12,604 | 3836 | 26,960 | 3471 | 70,345 | 11,140 | 156,509 |

| No. of antihypertensive medications, mean (SD) | 5 (0.5) | 3 (0.4) | 4 (0.6) | 2 (0.8) | 5 (0.5) | 3 (0.5) | 4 (0.6) | 1 (2) |

| Medication classes, N (column %) | ||||||||

| RAASis | 1049 (92) | 10,070 (80) | 3411 (89) | 17,726 (66) | 2956 (85) | 48,613 (69) | 8896 (80) | 51,488 (33) |

| ACEI | 580 (51) | 5974 (47) | 1981 (52) | 12,154 (45) | 1652 (48) | 29,346 (42) | 5488 (49) | 31,864 (20) |

| ARB | 469 (41) | 4096 (33) | 1430 (37) | 5572 (21) | 1304 (38) | 19,267 (27) | 3408 (31) | 19,624 (13) |

| Diuretics | 1097 (96) | 9310 (74) | 3530 (92) | 12,199 (45) | 3193 (92) | 43,614 (62) | 9525 (86) | 50,709 (32) |

| Loop diuretics | 608 (53) | 3877 (31) | 1750 (46) | 4381 (16) | 2007 (58) | 22,261 (32) | 6210 (56) | 28,885 (19) |

| Thiazide-like diuretics | 600 (53) | 5400 (43) | 1960 (51) | 7551 (28) | 1404 (40) | 20,760 (30) | 3644 (33) | 20,374 (13) |

| Mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist | 197 (17) | 659 (5) | 557 (15) | 755 (3) | 707 (20) | 3953 (6) | 2277 (20) | 6952 (4) |

| Other potassium-sparing diuretics | 178 (16) | 833 (7) | 472 (12) | 734 (3) | 217 (6) | 1616 (2) | 441 (4) | 1668 (1) |

| β-blockers | 1034 (91) | 9039 (72) | 3292 (86) | 11,935 (44) | 3113 (90) | 46,477 (66) | 9454 (85) | 51,985 (33) |

| CCBs | 941 (83) | 6819 (54) | 2577 (67) | 7191 (27) | 2752 (79) | 36,950 (53) | 5645 (51) | 33,380 (21) |

| Direct vasodilators | 600 (53) | 2016 (16) | 885 (23) | 900 (3) | 1962 (57) | 14,332 (20) | 4073 (37) | 17,408 (11) |

| α-blockers | 448 (39) | 1761 (14) | 1122 (29) | 2221 (8) | 2259 (65) | 27,226 (39) | 5959 (54) | 31,736 (20) |

| Centrally acting α-agonists | 327 (29) | 711 (6) | 421 (11) | 291 (1) | 586 (17) | 2341 (3) | 478 (4) | 2520 (2) |

| Most frequent combinations, N (column %) | ||||||||

| RAASi, CCB, β-blockers | 755 (66) | 2911 (23) | 1806 (47) | 1076 (4) | 1963 (57) | 10,426 (15) | 3177 (29) | 7662 (5) |

| RAASi, CCB, any diuretics | 804 (70) | 2916 (23) | 1978 (52) | 1098 (4) | 2016 (58) | 10,129 (14) | 3174 (29) | 7909 (5) |

| RAASi, β-blockers, loop diuretics | 468 (41) | 1805 (14) | 1265 (33) | 1353 (5) | 1410 (41) | 7348 (10) | 3863 (35) | 8408 (5) |

| CCB, β-blockers, loop diuretics | 430 (38) | 962 (8) | 861 (22) | 339 (1) | 1303 (38) | 4155 (6) | 1874 (17) | 3491 (2) |

| RAASi, β-blockers, thiazide diuretics | 478 (42) | 2632 (21) | 1427 (37) | 1421 (5) | 1010 (29) | 6647 (10) | 2159 (19) | 5571 (4) |

| RAASi, CCB, thiazide diuretics | 438 (38) | 1851 (15) | 1144 (30) | 709 (3) | 949 (27) | 6346 (9) | 1647 (15) | 4655 (3) |

| CCB, β-blockers, thiazide diuretics | 419 (37) | 1059 (9) | 971 (25) | 155 (0.6) | 929 (27) | 2976 (4) | 1323 (12) | 2203 (1) |

RAASi, renin-angiotensin system inhibitor; ACEI, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; CCB, calcium channel blocker.

Discussion

Our study applying contemporary BP goal (<130/80 mm Hg) and systolic BP goal (<120 mm Hg) and leveraging the hypertension populations of two large integrated health systems within the United States demonstrated that more than one in three and up to a half of patients with CKD and hypertension met criteria for apparent treatment-resistant hypertension. Among these patients with CKD and apparent treatment-resistant hypertension, most had uncontrolled resistant hypertension or refractory hypertension. These data suggest an opportunity to improve treatment and outcomes in a population vulnerable to the adverse effects of high BP.

The target BP goal for patients with CKD has been a topic of controversy. Our study shows that the prevalence of apparent treatment-resistant hypertension is in the range of 35%–55% in two health systems when applying the contemporary BP goal of <130/80 mm Hg or the systolic BP goal of <120 mm Hg. As expected, the effect of the 2017 ACC/AHA guideline was relatively smaller than the effect of the 2021 KDIGO guideline. The study cohorts were drawn from 2014 to 2015 for Kaiser Permanente Southern California and 2018 for the Veterans Health Administration; one is before and the other is after the release of the 2017 ACC/AHA guideline. Therefore, the smaller prevalence in the Veterans Health Administration (35%) than in Kaiser Permanente Southern California (40%) according to the 2017 ACC/AHA guideline may represent practice change on the basis of the updated guidelines.

The prevalence of apparent treatment-resistant hypertension has been estimated to be 29% among patients with CKD from a recent meta-analysis of 3.2 million patients (1). Another study of 3367 patients in the Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort reported that the prevalence of apparent treatment-resistant hypertension was 40% among those with hypertension and eGFR between 20 and 70 ml/min per 1.73 m2 (2). These studies applied the historical general population BP goal of <140/90 mm Hg and therefore do not reflect contemporary guidelines for CKD. Our study observed a lower apparent treatment-resistant hypertension prevalence of 27%–32% when applying the historical general population BP goal of <140/90 mm Hg. This may be due to the integrated health care system setting with standardized hypertension protocols, which has historically demonstrated higher hypertension control rates compared with the United States overall (10,11). The prevalence of apparent treatment-resistant hypertension was higher at more advanced stages of CKD, consistent with previous findings (12).

When we required a diuretic to define apparent treatment-resistant hypertension, the prevalence of apparent treatment-resistant hypertension was lowered to 23%–31%. Most of the differences before and after requiring a diuretic to define apparent treatment-resistant hypertension were from the prevalence of uncontrolled resistant hypertension because only 62%–74% were on diuretics. These percentages of diuretic use were considerably lower than the percentages among those of controlled resistant hypertension (86%–92%) and refractory hypertension groups (92%–96%). The 2008 Scientific Statement on Resistant Hypertension and the 2018 Scientific Statement on Resistant Hypertension (13,14) recommend using a diuretic at maximum or maximally tolerated doses to manage resistant hypertension. High proportions of resistant hypertension cases are associated with volume excess, especially in CKD; therefore, a diuretic is an effective treatment option to lower BP (14). One may argue that the lower prevalence of apparent treatment-resistant hypertension (23%–31%) with the diuretic requirement is a more accurate reflection of true resistant hypertension. However, our study population reflects patients with CKD from real-world clinical settings; therefore, requiring a diuretic to define apparent treatment-resistant hypertension may fail to capture the prevalence of resistant hypertension from patient- and provider-related factors.

The use of renin-angiotensin system inhibitors was notably high, at 69%–92%, across all types of apparent treatment-resistant hypertension. Some of the most frequent combination agents were renin-angiotensin system inhibitors, calcium channel blockers, and any diuretics for both Kaiser Permanente Southern California and Veterans Health Administration populations, consistent with guideline-recommended therapy (14). However, recommended long-acting thiazide-like diuretics and mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists (4,15) may have been underutilized, which suggests a potential area for improvement.

Our findings demonstrate that an estimated 35%–40% of patients with CKD would require four or more antihypertensive medications in a real-world clinical setting. These percentages are higher than what was reported in the Systolic Blood Pressure Intervention Trial (SPRINT) (16). In this trial, CKD participants randomized to an intensive treatment group used an average of 2.9 antihypertensive medications, and 30% were on four or more medications (16). This may be because participants with CKD in the SPRINT trial were restricted to having a systolic BP between 130 and 180 mm Hg, eGFR of 20–59 ml/min per 1.73 m2, and no presence of proteinuria (e.g., 24-hour urinary protein excretion ≥1 g/d); thereby, the trial included a less severe CKD cohort compared with our study cohorts. Future studies should evaluate side effects related to the higher number of medications used to meet the BP goal in a real-world setting.

This study has several limitations, which may affect the interpretation of our findings. Our study used office BP measures extracted from the electronic health records, and we did not have information on out-of-office BP measurements, which may be a more accurate assessment of individuals’ BP. Because of differences between office BP compared with ambulatory and home BP measurements, the prevalence of apparent treatment-resistant hypertension may be overestimated. However, office BP is measured on the basis of a standardized approach, and office BP is mostly used in routine clinical practice for treatment decisions outside of specialty hypertension or nephrology practices. In addition, we did not have information on medication dose and medication adherence to account for clinical inertia or patient-related factors to identify true resistant hypertension. Despite these potential limitations, our study cohort inclusive of patients with CKD from two large integrated health systems within the United States represents one of the largest and most diverse apparent treatment-resistant hypertension studies among patients with CKD to date.

In summary, we found that a substantial proportion of patients with CKD and hypertension met criteria for apparent treatment-resistant hypertension and would qualify for treatment intensification on the basis of contemporary guidelines. This would result in treatment regimens of four or more antihypertensive medications for many patients. Studies examining the optimal approaches to identifying resistant hypertension, establishing clear BP goals that are associated with outcomes in CKD, and minimizing side effects of these medications in real-world CKD populations would improve our understanding and management of this high-risk population.

Disclosures

J. An reports employment with Kaiser Permanente Southern California and research funding from the American Heart Association (grant 810957), AstraZeneca, Merck, the National Institutes of Health (grants R01 HL158790, R01 HL155081, and R01HL142834), and Novartis. M. Kurella Tamura reports employment with the Veterans Affairs Palo Alto Health Care System, honoraria from the American Federation for Aging Research, research funding from the National Institutes of Health (grant R01 DK128108), serving as an associate editor of CJASN, and serving in an advisory or leadership role for the Beeson External Advisory Committee and the Clin-Star Advisory Board. M.E. Montez-Rath reports research funding from the National Institutes of Health (grant R01 DK128108) and Sanofi (innovations in Data Exploration & Analytics [iDEA] award). M.C. Odden reports consultancy agreements with Cricket Health, Inc. and research funding from the National Institutes of Health (National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute grant R01-HL151564 and National Institute of Aging [NIA] grants R01-AG071019 and RF1-AG062568). J.J. Sim reports research funding from AstraZeneca Pharmaceuticals, Otsuka Pharmaceuticals, and Visterra. I.-C. Thomas reports employment with Veterans Affairs Palo Alto. All remaining authors have nothing to disclose.

Funding

None.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Because Manjula Kurella Tamura is an associate editor of CJASN, she was not involved in the peer review process for this manuscript. Another editor oversaw the peer review and decision-making process for this manuscript.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

See related editorial, “Resistant Hypertension in Chronic Kidney Disease: A Burden unto Itself,” on pages 1436–1438.

Author Contributions

J. An, M. Kurella Tamura, M.C. Odden, and J.J. Sim conceptualized the study; L. Ni and I.-C. Thomas were responsible for data curation; J. An, M. Kurella Tamura, M.E. Montez-Rath, L. Ni, M.C. Odden, J.J. Sim, and I.-C. Thomas were responsible for investigation; L. Ni and I.-C. Thomas were responsible for formal analysis; J. An, M. Kurella Tamura, M.E. Montez-Rath, L. Ni, M.C. Odden, J.J. Sim, and I.-C. Thomas were responsible for methodology; L. Ni and I.-C. Thomas were responsible for software; J. An, M. Kurella Tamura, L. Ni, J.J. Sim, and I.-C. Thomas were responsible for validation; M.E. Montez-Rath was responsible for visualization; J. An, M. Kurella Tamura, and J.J. Sim provided supervision; J. An wrote the original draft; and J. An, M. Kurella Tamura, M.E. Montez-Rath, L. Ni, M.C. Odden, J.J. Sim, and I.-C. Thomas reviewed and edited the manuscript.

Data Sharing Statement

Individual participant data will not be shared.

Supplemental Material

This article contains the following supplemental material online at http://cjasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.2215/CJN.04110422/-/DCSupplemental.

Supplemental Table 1. Crude and age-, sex-, race- and ethnicity-adjusted prevalence (95% confidence intervals) of apparent treatment-resistant hypertension applying different clinical guidelines.

References

- 1.Noubiap JJ, Nansseu JR, Nyaga UF, Sime PS, Francis I, Bigna JJ: Global prevalence of resistant hypertension: A meta-analysis of data from 3.2 million patients. Heart 105: 98–105, 2019. 10.1136/heartjnl-2018-313599 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thomas G, Xie D, Chen HY, Anderson AH, Appel LJ, Bodana S, Brecklin CS, Drawz P, Flack JM, Miller ER 3rd, Steigerwalt SP, Townsend RR, Weir MR, Wright JT Jr, Rahman M; CRIC Study Investigators : Prevalence and prognostic significance of apparent treatment resistant hypertension in chronic kidney disease: Report from the Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort study. Hypertension 67: 387–396, 2016. 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.115.06487 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Akwo EA, Robinson-Cohen C, Chung CP, Shah SC, Brown NJ, Ikizler TA, Wilson OD, Rowan BX, Shuey MM, Siew ED, Luther JM, Giri A, Hellwege JN, Velez Edwards DR, Roumie CL, Tao R, Tsao PS, Gaziano JM, Wilson PWF, O’Donnell CJ, Edwards TL, Kovesdy CP, Hung AM; VA Million Veteran Program : Association of apparent treatment-resistant hypertension with differential risk of end-stage kidney disease across racial groups in the Million Veteran Program. Hypertension 78: 376–386, 2021. 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.120.16181 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fay KS, Cohen DL: Resistant hypertension in people with CKD: A review. Am J Kidney Dis 77: 110–121, 2021. 10.1053/j.ajkd.2020.04.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carey RM, Sakhuja S, Calhoun DA, Whelton PK, Muntner P: Prevalence of apparent treatment-resistant hypertension in the United States. Hypertension 73: 424–431, 2019. 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.118.12191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, Casey DE Jr., Collins KJ, Dennison Himmelfarb C, DePalma SM, Gidding S, Jamerson KA, Jones DW, MacLaughlin EJ, Muntner P, Ovbiagele B, Smith SC Jr., Spencer CC, Stafford RS, Taler SJ, Thomas RJ, Williams KA Sr., Williamson JD, Wright JT Jr.: 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA guideline for the prevention, detection, evaluation, and management of high blood pressure in adults: A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Hypertension 71: e13–e115, 2018. 10.1161/HYP.0000000000000065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tomson CRV, Cheung AK, Mann JFE, Chang TI, Cushman WC, Furth SL, Hou FF, Knoll GA, Muntner P, Pecoits-Filho R, Tobe SW, Lytvyn L, Craig JC, Tunnicliffe DJ, Howell M, Tonelli M, Cheung M, Earley A, Ix JH, Sarnak MJ: Management of blood pressure in patients with chronic kidney disease not receiving dialysis: Synopsis of the 2021 KDIGO clinical practice guideline. Ann Intern Med 174: 1270–1281, 2021. 10.7326/M21-0834 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cheung AK, Chang TI, Cushman WC, Furth SL, Hou FF, Ix JH, Knoll GA, Muntner P, Pecoits-Filho R, Sarnak MJ, Tobe SW, Tomson CRV, Lytvyn L, Craig JC, Tunnicliffe DJ, Howell M, Tonelli M, Cheung M, Earley A, Mann JFE: Executive summary of the KDIGO 2021 clinical practice guideline for the management of blood pressure in chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int 99: 559–569, 2021. 10.1016/j.kint.2020.10.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Levey AS, Stevens LA, Schmid CH, Zhang YL, Castro AF 3rd, Feldman HI, Kusek JW, Eggers P, Van Lente F, Greene T, Coresh J; CKD-EPI (Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration) : A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med 150: 604–612, 2009. 10.7326/0003-4819-150-9-200905050-00006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sim JJ, Handler J, Jacobsen SJ, Kanter MH: Systemic implementation strategies to improve hypertension: The Kaiser Permanente Southern California experience. Can J Cardiol 30: 544–552, 2014. 10.1016/j.cjca.2014.01.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Department of Veterans Affairs; Department of Defense : VA/DoD Clinical Practice Guideline for the Diagnosis and Management of Hypertension in the Primary Care Setting, 2020. Available at: https://www.healthquality.va.gov/guidelines/CD/htn/VADoDHypertensionCPG508Corrected792020.pdf. Accessed February 14, 2022

- 12.Tanner RM, Calhoun DA, Bell EK, Bowling CB, Gutiérrez OM, Irvin MR, Lackland DT, Oparil S, Warnock D, Muntner P: Prevalence of apparent treatment-resistant hypertension among individuals with CKD. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 8: 1583–1590, 2013. 10.2215/CJN.00550113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Calhoun DA, Jones D, Textor S, Goff DC, Murphy TP, Toto RD, White A, Cushman WC, White W, Sica D, Ferdinand K, Giles TD, Falkner B, Carey RM; American Heart Association Professional Education Committee : Resistant hypertension: Diagnosis, evaluation, and treatment: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association Professional Education Committee of the Council for High Blood Pressure Research. Circulation 117: e510–e526, 2008. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.189141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carey RM, Calhoun DA, Bakris GL, Brook RD, Daugherty SL, Dennison-Himmelfarb CR, Egan BM, Flack JM, Gidding SS, Judd E, Lackland DT, Laffer CL, Newton-Cheh C, Smith SM, Taler SJ, Textor SC, Turan TN, White WB; American Heart Association Professional/Public Education and Publications Committee of the Council on Hypertension; Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing; Council on Clinical Cardiology; Council on Genomic and Precision Medicine; Council on Peripheral Vascular Disease; Council on Quality of Care and Outcomes Research; and Stroke Council : Resistant hypertension: Detection, evaluation, and management: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Hypertension 72: e53–e90, 2018. 10.1161/HYP.0000000000000084 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Agarwal R, Sinha AD, Cramer AE, Balmes-Fenwick M, Dickinson JH, Ouyang F, Tu W: Chlorthalidone for hypertension in advanced chronic kidney disease. N Engl J Med 385: 2507–2519, 2021. 10.1056/NEJMoa2110730 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cheung AK, Rahman M, Reboussin DM, Craven TE, Greene T, Kimmel PL, Cushman WC, Hawfield AT, Johnson KC, Lewis CE, Oparil S, Rocco MV, Sink KM, Whelton PK, Wright JT Jr., Basile J, Beddhu S, Bhatt U, Chang TI, Chertow GM, Chonchol M, Freedman BI, Haley W, Ix JH, Katz LA, Killeen AA, Papademetriou V, Ricardo AC, Servilla K, Wall B, Wolfgram D, Yee J; SPRINT Research Group : Effects of intensive BP control in CKD. J Am Soc Nephrol 28: 2812–2823, 2017. 10.1681/ASN.2017020148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.