Abstract

Visual and vestibular deficits, as measured by a visio-vestibular examination (VVE), are markers of concussion in youth. Little is known about VVE evolution post-injury, nor influence of age or sex on trajectory. The objective was to describe the time trend of abnormal VVE elements after concussion. Two cohorts, 11–18 years, were enrolled: healthy adolescents (n = 171) from a high school with VVE assessment before or immediately after their sport seasons and concussed participants (n = 255) from a specialty care concussion program, with initial assessment ≤28 days from injury and VVE repeated throughout recovery during clinical visits. The primary outcome, compared between groups, is the time course of recovery of the VVE examination, defined as the probability of an abnormal VVE (≥2/9 abnormal elements) and modeled as a cubic polynomial of days after injury. We explored whether probability trajectories differed by: age (<14 years vs. 14+ years), sex, concussion history (0 versus 1+), and days from injury to last assessment (≤28 days vs. 29+ days). Overall, abnormal VVE probability peaked at 0.57 at day 8 post-injury, compared with an underlying prevalence of 0.083 for uninjured adolescents. Abnormal VVE probability peaked higher for those 14+ years, female, with a concussion history and whose recovery course was longer than 28 days post-injury, compared with their appropriate strata subgroups. Females and those <14 years demonstrated slower resolution of VVE abnormalities. VVE deficits are common in adolescents after concussion, and the trajectory of resolution varies by age, sex, and concussion history. These data provide insight to clinicians managing concussions on the timing of deficit resolution after injury.

Keywords: brain injury, neurofunction, pediatric, time course

Introduction

Visual and vestibular deficits are common markers of concussion in youth with several studies of adolescents presenting to a specialty concussion program showing nearly 70% of patients had one or more oculomotor diagnoses.1,2 Examining a broader age range of 5–21 years, virtually all patients (95%) seen at a multi-disciplinary concussion practice demonstrated vergence, accommodation, or visual tracking deficits.3

Vestibular dysfunction is similarly common with up to four of five concussed youth presenting with deficits in balance, gait, or the vestibulo-ocular reflex (VOR).4–6 These systems likely interact, because post-injury visual deficits can be associated with abnormal balance performance.7 In addition to their high frequency, visio-vestibular deficits in concussed youth are associated with extended recovery and negatively impact quality of life.8–10 Concussion-related vision symptoms, in particular, are associated with two times elevated risk of academic difficulty.11

As a result, a comprehensive visio-vestibular assessment is recommended as a key concussion assessment.12–14 Building on studies of the Vestibular/Oculomotor Screening (VOMS),13,14 our research group has developed a visio-vesibular examination (VVE), comprising nine elements including smooth pursuit, horizontal and vertical saccades, angular VOR, near point of convergence (NPC), right and left accommodative amplitude, and complex tandem gait. This examination is highly diagnostic and prognostic for concussion. Examination deficits are associated with a 17-fold increased likelihood of a concussion diagnosis after head trauma, and each additional examination deficit doubles the likelihood of diagnosis.15–17

While the VVE has been shown to be reliable and feasible across diverse healthcare settings,16–18 little is known about the time trajectory of VVE deficits post-injury. Cross-sectional studies have documented the presence of these deficits in the acute and subacute phases after concussion1,19,20; however, limited research has examined the characteristics of these deficits longitudinally. Elbin and associates21 explored prospective changes in visio-vestibular presentation in concussed adolescents, with resolution of impairments, with the exception of VOR and visual motion sensitivity, occurring at day 8–14. Further quantification of VVE evolution post-injury will provide important clinical guidance on the utility of this examination across the heterogenous presentation of concussion.

In addition, we hypothesize that sex, age, and concussion history influence the trajectory of VVE deficits. These confounders have repeatedly been shown to influence symptom burden, neurocognitive performance, and overall recovery22–24; however, their influence on post-injury visual and vestibular function has been mixed. Several studies have identified greater deficits in females on NPC, gaze stability, and tandem gait compared with males,25–27 while others have found no sex differences.26,28 The data are also conflicting with regard to concussion history; in a study of more than 1000 adolescent with concussion, those with and without concussion histories presented with similar visio-vestibular function29; however, others have suggested that concussion history contributes to abnormalities on post-injury dual-task gait.30 No studies to date have evaluated how the trajectory of visio-vestibular deficits may differ by age, sex, or concussion history.

Therefore, the objective of this analysis was to determine the time course of visio-vestibular deficits after concussion, from acute presentation to recovery, differentiating patterns by sex, age, and concussion history.

Methods

Study design, setting, and participants

Participants, 11–18 years, were enrolled between 8/18/2017–10/26/2020 as part of a prospective observational cohort study approved by the Children's Hospital of Philadelphia Institutional Review Board. Participants and/or their parents/legal guardians provided written assent/written informed consent. Uninjured athletes were recruited from a suburban middle and high school and were offered an opportunity to participate in clinical assessments at the beginning of and immediately after their sport season. A single uninjured participant could have multiple assessments across multiple sport seasons and across multiple academic years; all assessments for a given participant were included.

Concussed participants were recruited from the CHOP Minds Matter Concussion Program as well as the suburban school. Youth from the participating school originally enrolled in the uninjured cohort who subsequently sustained a concussion were only included in the concussed cohort. If a participant sustained multiple injuries during the enrollment period, only the first was included. The diagnosis of concussion was made by a trained sports medicine pediatrician according to the most recent Consensus Statement on Concussion.31 All concussed individuals had initial clinical assessments within 28 days of injury and assessments were repeated through recovery as part of standard clinical care.

In this study, recovery was defined as the time when the clinician determined the course of care was complete, and that the participant was cleared to return to previous activities, based on symptom trajectory, physical examination findings, and cognitive functioning. Participants were excluded from enrollment if they were still recovering from a previous concussion (or within 30 days of clearance from a previous concussion) or if they sustained lower extremity injury preventing the assessment of gait. Trained research staff conducted clinical assessments in either the school athletic training room or the sports medicine office.

Clinical assessments

Demographics

Age, sex, race, ethnicity, and concussion history were self-reported for healthy participants and abstracted from the medical record for concussion cases.

VVE

The VVE is a battery of nine maneuvers (Table 1) that has been implemented and shown reliable across multiple specialties.16–18 Its elements include:

Table 1.

Visio-Vestibular Examination Elements

| Examination element | Description | Abnormalities | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Smooth pursuit | Examiner stands approximately 30 cm in front of patient. Patient follows examiner's finger in the horizontal plane, moving from side to side, for 5 repetitions (1 repetition back and forth side to side equals one complete cycle) | Symptom provocation (eye fatigue, eye pain, dizziness, headache, or nausea), jerky or jumpy eye movement, or inability to complete due to symptom provocation, or >3 beats of nystagmus |

| 2,3 | Fast saccades - horizontal and vertical | Examiner stands approximately 30 cm in front of patient. Patient looks back and forth as rapidly as he or she can, up to 30 total repetitions with head fixed, between two fixed objects (horizontal, fingers placed shoulder-width apart; vertical, fingers placed at mid-forehead and sternal notch), stopping if they have symptom provocation | Symptom provocation (eye fatigue, eye pain, dizziness, headache, or nausea), or inability to complete due to symptom provocation, at ≤20 repetitions |

| 4,5 | Gaze stability (angular vestibular oculomotor reflex) – horizontal and vertical | Examiner stands approximately 30 cm in front of patient. Patient nods head “yes” (vertical, approximately 30 degree above and below midline) or shakes head “no” (horizontal, approximately 45 degrees to the left and right of midline) while fixing eyes on examiner's finger for up to 30 total repetitions or when symptoms are provoked | Symptom provocation (eye fatigue, eye pain, dizziness, headache, or nausea), or inability to complete due to symptom provocation, at ≤20 repetitions |

| 6 | Near point of convergence (NPC) | A standard Astron accommodative rule (Gulden Ophthalmics, Elkins Park, PA) with a single column 20/30 card is used; patient reports distance where break (single column becomes double) occurs | Double vision (receded NPC) >6 cm from patient's forehead |

| 7,8 | Monocular accommodative amplitude – left and right | A standard Astron accommodative rule (Gulden Ophthalmics, Elkins Park, PA) with a single column 20/30 card is used; patient reports distance where letters blur | Age-based cutoff determined by Hofstetter formula |

| 9 | Complex tandem gait | Patient walks forward and backward, heel-to-toe, with eyes open then closed, for 5 steps each; examiner evaluates for steps off the line for each of the 5 steps, as well as sway, for each of the 4 conditions (sway defined as any widening of gait, raising of arms for stability, or any truncal movement off the vertical | >5 errors (steps off straight line) or sway across any complex tandem gait condition (each condition scaled 0-6 [1 point for each error out of 5, 1 point for sway], total score 0-5) |

| Total VVE Score | Overall assessment of previous 9 subtests | ≥2 abnormal subtests | |

Smooth pursuit, evaluating the subject's ability to track in a horizontal plane for five repetitions, with an abnormality defined as symptom provocation, jerky or jumpy eye movements, or nystagmus16;

Horizontal and vertical saccades, with the participant's eyes moving rapidly between two fixed objects with a deficit defined as symptom provocation with 20 or fewer repetitions16,32;

Horizontal and vertical gaze stability, or angular VOR, where the participant's eyes are fixed and his or her head moves in the horizontal or vertical plane, with a deficit defined as symptom provocation with 20 or fewer repetitions;16,32

NPC, assessing for break (double vision) using a standard Astron accommodative rule (Gulden Ophthalmics, Elkins Park, PA) with a single column 20/30 card, with receded NPC defined as break >6 cm33;

Right and left accommodation, assessing clear to blur distance with one eye open using a standard Astron accommodative rule, with an abnormal distance based on age using the Hofstetter formula34;

Complex tandem gait, where the participant is evaluated walking in tandem for five steps forward and backward, eyes open and closed; a point is assigned for each step off the line, as well as sway on each of the four conditions, with abnormal defined as a composite score of at least 5 (on a total scale of 0–24).6

An abnormal VVE score was defined as having deficits on two or more elements.35 While similar to the VOMS, there are key differences in the VVE, including the addition of complex tandem gait (a dynamic measure of balance with high diagnostic sensitivity)6 and monocular accommodation (providing unique prognostic implications and a post-injury rehabilitation target), extending the number of repetitions for saccades and VOR to 20 to increase diagnostic sensitivity,32 and evaluating objective physical signs of dysfunction in addition to subjective symptom reporting for smooth pursuit.

Post-Concussion Symptom Inventory (PCSI)

The adolescent PCSI assesses 21 concussion symptoms on a severity scale of 0–6,36 for a total symptom score (0–132).36 The PCSI Child, used for children age <13 years, includes 17 items with simplified wording, for a total symptom score of 0–102. All subjects completed the PCSI self-report form electronically.37

Modeling and statistical analyses

See Supplementary Appendix SA1 for a complete description of our modeling approach. Briefly, to model how the VVE changes with time after injury, we introduced two sets of binary variables for each observation to denote the presence of an abnormal VVE and concussed status. Given that some VVE examination abnormalities could worsen after injury before plateauing,15 we modeled the logit of probability of an abnormal VVE score at a specific assessment time point as a cubic polynomial of the number of days post-injury to allow for potential non-linear trends. We then defined a variable for the number of days after injury when the outcome probability plateaued and no longer improved.

To account for differential follow-up, we included all individuals in the modeling, even for times taking place after their final observation date, by carrying their last observed VVE score forward, operating under the assumption that the date of late observation corresponded to recovery or near recovery. Because fewer than 5% of the total patients were lost to follow-up before being determined as recovered, the assumption to carry the last observation forward is well justified. To fit this model, we performed likelihood maximization via grid search to obtain estimates for the outcome measure of an abnormal VVE.

Data were examined first for the overall study sample and then by the following stratifications: days from injury to last assessment (≤28 days vs. 29+ days, a proxy for differentiating recovery times, chosen based on the definition of persistent post-concussion symptoms (PPCS)38); age (<14 years vs. 14+ years, because this generally marks the division between middle and high school); sex (male vs. female); and concussion history (0 versus 1+).

Hypothesis tests were based on permutation of strata labels; large differences relative to the null distribution represent significant differences in VVE scores between strata. In addition, we compared demographics for concussed participants to uninjured participants using chi-square statistics for categorical variables (sex, race/ethnicity, age group, and concussion history) and F-tests for continuous age. In some instances, uninjured participants contributed more than one observation. To determine whether these repeated measurements biased our stratified comparisons, we applied an outputation procedure,39 where independent random subsamples of the data were used to calculate differences between strata, and we found no significant effect of repeated observations from the same individuals (p = 0.759). All analyses were conducted using R (RStudio, Inc).

Results

In total, 171 uninjured participants were included, assessed on average 2.4 times with a total number of 411 assessment points, and 255 concussed cases were included, observed an average of 2.6 time points (maximum 10) totaling 665 assessment points. Demographics are shown in Table 2. Fourteen participants completed the incorrect PCSI form for their age; two (both concussed) age 13+ years completed PCSI Child, and 12 ≤ 12 years (four concussed) completed PCSI adolescent. These assessments were excluded from the average PCSI data presented.

Table 2.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of the Study Cohort

| Characteristic | Subjects with concussion (n = 255) | Healthy participants (n = 171) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (mean [std. dev.]) (years)* <14 years (n [%]) >14 years (n [%]) |

15.5 (1.6) 51 (20) 204 (80) |

15.3 (1.7) 44 (25.8) 127 (74.2) |

| Sex (n [%]) Female Male |

137 (53.7) 118 (46.3) |

95 (55.6) 76 (44.4) |

| Race (n [%]) Black or African American White Other |

21 (8.2) 206 (80.8) 28 (11.0) |

22 (12.8) 132 (77.2) 17 (10) |

| Ethnicity (n [%]) Hispanic or Latino Non-Hispanic Other/Unknown |

7 (2.8) 243 (95.3) 5 (1.9) |

6 (3.6) 148 (86.5) 17 (9.9) |

| History of prior concussion (n [%]) No Yes Missing data |

136 (53.3) 118 (46.3) 1 (0.0) |

122 (71.3) 45 (26.3) 4 (2.3) |

| Days from injury to first visit (mean [std. dev.]) (days) | 12.2 (8.6) |

NA |

| Days from injury to last assessment in clinic (n [%]) ≤28 days >28 days |

114 (44.7) 141 (55.3) |

NA NA |

| PCSI at initial assessment (mean [std. dev.]) | 38.2 (26.2) | 6.5 (10.5) |

PCSI, Post-Concussion Symptom Inventory.

For uninjured participants who were assessed more than once and their age in one assessment was <14 years and in a subsequent assessment was 14+ years, for this table, they are included only in the <14 years count. For analysis and modeling, they are assigned the appropriate age that corresponds with their actual age at time of assessment.

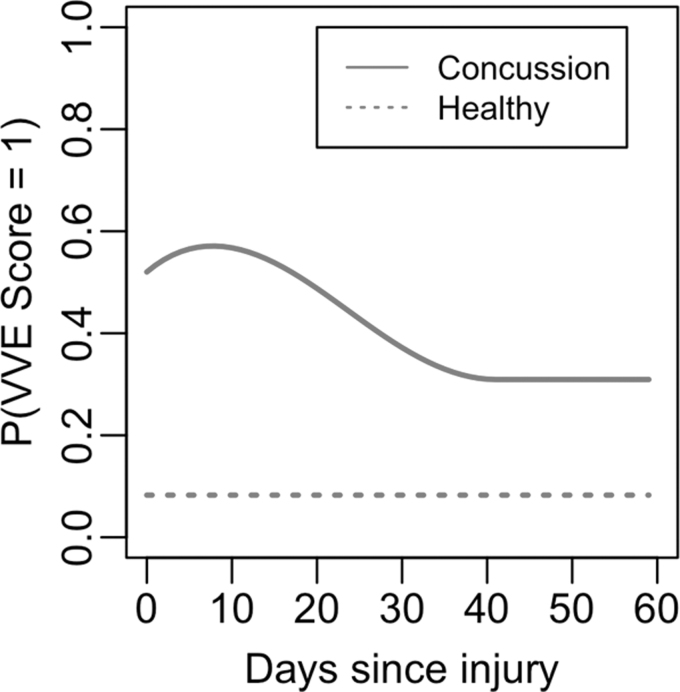

The probability of having an abnormal VVE is presented in Figure 1. The estimated value of the model parameters is presented in Supplementary Table A2 for the overall sample as well as for stratified analyses. The magnitude and time course of probability of abnormal VVE score is summarized in Table 3. In the overall sample, the probability of having an abnormal VVE score peaked in concussed cases at 0.57 at day 8 after injury, with the plateau occurring at 0.31 on day 41 after injury. The probability of abnormal VVE for uninjured participants was 0.083.

FIG. 1.

Probability of an abnormal visio-vestibular examination (VVE) score across 60 days after injury for overall sample. The horizontal dashed line represents abnormal VVE score probability for uninjured participants while the solid line indicates abnormal probability for concussion cases.

Table 3.

Stratified Measures of Abnormal Visio-Vestibular Examination Score Probabilities

| Stratification | Probability of abnormal VVE score in uninjured participants | Probability of abnormal VVE score on day of injury in cases | Peak probability of abnormal VVE score in cases | Days post-injury when abnormal VVE score peaks | Probability of abnormal VVE score at recovery plateau | Days to recovery plateau |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall sample | 0.083 | 0.520 | 0.571 | 8 | 0.309 | 41 |

| Last assessment ≤28 days post-injury |

0.083 |

0.711 |

0.711 |

0 |

0.137 |

24 |

| Last assessment >28 days post-injury |

0.083 |

0.870 |

0.870 |

0 |

0.294 |

55 |

| Age <14 years | 0.090 | 0.475 | 0.518 | 9 | 0.279 | 48 |

| Age ≥14 years | 0.081 | 0.525 | 0.576 | 8 | 0.313 | 41 |

| Female | 0.106 | 0.717 | 0.719 | 2 | 0.328 | 47 |

| Male | 0.053 | 0.493 | 0.493 | 0 | 0.283 | 41 |

| No concussion history |

0.085 |

0.490 |

0.618 |

11 |

0.299 |

44 |

| With concussion history |

0.069 |

0.737 |

0.737 |

0 |

0.351 |

20 |

β0 and α are transformed using inverse-logit functions to obtain the probability of abnormal VVE on day of injury for concussion cases and uninjured participants, respectively.

Number of days to recovery plateau is the transformed model parameter 30*exp(γ) where γ is listed in Table A2.

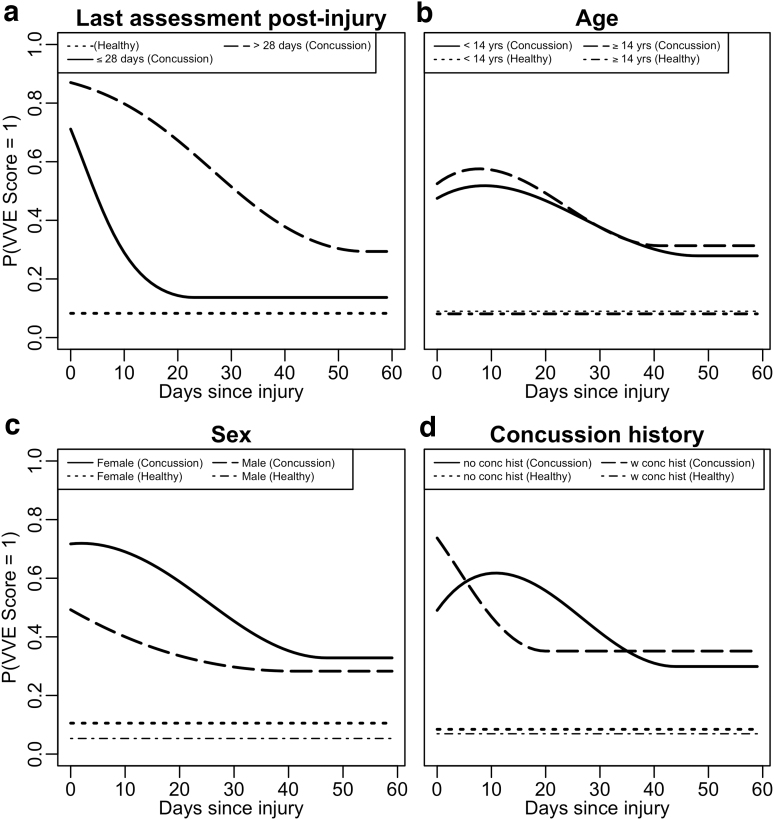

Each stratification (sex, days since injury, age, and concussion history) demonstrated significant differences in the probability of abnormal VVE scores among concussed cases (p < 0.001 in each comparison; Fig. 2, Table 3); there were no significant differences in uninjured participant probabilities across all strata. The distribution of demographics for each stratification is presented in Supplementary Table A3. Females with concussion had a peak probability of an abnormal VVE score of 0.72 at day 2 post-injury compared with 0.49 for males on the day of concussion. Females demonstrated slower resolution of VVE abnormalities (average of 47 days until plateau compared with 41 days in males), with a higher probability of abnormal VVE score (0.33) at the plateau (0.28 for males).

FIG. 2.

Probabilities of an abnormal visio-vestibular examination (VVE) score across 60 days post-injury stratified by (a) date of last assessment post-injury, (b) age, (c) sex, and (d) concussion history. The horizontal dotted lines represent abnormal VVE score probabilities for uninjured participants while the solid lines indicate abnormal VVE score probabilities for concussion cases.

Those whose last assessment was >28 days after injury had a peak probability of an abnormal VVE score of 0.87 on the day of concussion while those whose last assessment was ≤28 days after injury peaked on the day of concussion with a probability of 0.71. The >28 day group plateaued on day 55 (probability 0.29) while the ≤28 day group plateaued on day 24 (probability 0.14). The peak probability of an abnormal VVE score was slightly higher (0.58) for those 14 years and older compared with the younger cohort (0.52). The younger age group demonstrated a delayed time to plateau (<14 years: 48 days; ≥14 years: 41 days).

Last, those with a concussion history demonstrated a higher and more immediate peak probability of abnormal VVE score (0.74 on the day of injury) compared with those with no previous concussions (0.62 on day 11). The plateau probabilities were 0.35 and 0.30 on days 20 and 44 after injury, respectively, for the two groups.

Discussion

Visio-vestibular deficits are common in youth after concussion; in this sample, the prevalence of an abnormal VVE peaked at approximately 60%, confirming previous estimates in similar populations.1,2,40 Probability modeling allowed us to examine the time trajectory of these deficits, offering advantages over traditional cross-sectional studies. By leveraging the fact that across our sample, individual patients were seen at various days after injury as part of clinical care, we gain a more granular view of the time course of post-injury VVE abnormalities.

The peak prevalence of VVE deficits occurred just more than one week after injury, suggesting that the neurodysfunction manifested by the abnormal examination takes time to develop. Unlike a structural traumatic brain injury, where the abnormalities are often seen within hours, concussion is a physiological injury that triggers a neurometabolical cascade that occurs over days to weeks affecting multiple aspects of brain function.41

Efforts to relate the pathophysiology of concussion to clinical correlates and presenting symptoms have been under way for many years using pre-clinical models.41,42 Our findings suggest that concussion pathophysiology appears to affect the oculomotor, vestibular, and autonomic nervous systems gradually over the course of days, as manifested by VVE deficits. This may be because of ongoing impairments in functional connectivity and neural synchronization that accumulate as the metabolic cascade unfolds. Understanding the foundational biology of VVE deficits is an important area of future work that will aid in the identification of and timing for therapeutic agents.

Of note, about one-third of patients continued to demonstrate VVE deficits beyond one month post-injury. This proportion directly aligns with previous studies of the prevalence of PPCS in youth,38,43 highlighting the importance of longitudinal assessment of these deficits. Further, it emphasizes the need to develop and evaluate targeted interventions, such as vestibular and vision rehabilitation, to address these persistent deficits. Vestibular rehabilitation, in particular, has demonstrated efficacy in reducing persistent vestibular symptoms and accelerating recovery.44–47 Vision rehabilitation shows similar promise, albeit with more limited evidence.48,49 Knowledge of the time course of visio-vestibular deficits has implications for the timing of these targeted rehabilitation strategies.50

An additional advantage of our approach is that it allowed for the delineation of time course differences among key demographic stratifications. The peak probability of an abnormal VVE was slightly higher in those ≥14 years while the younger age group demonstrated a delayed time to plateau. Our previous description of the natural history of concussion in elementary school-aged children identified that the proportion of concussed patients ages 9–11 years with abnormal visio-vestibular assessment findings was greater than those ages 5–8 years,40 suggesting a positive correlation between age and VVE deficits across the pediatric age range.

The effect of age on concussion outcomes has been studied extensively, contributing to a general understanding that time to recovery is longer for adolescents compared with young adults or elementary-aged children.43 The outcomes for these studies, however, have mainly been symptom-based, and our data provide the first assessment of how VVE presentation and recovery may change across adolescence.

Similarly, this approach highlighted the unique trajectory of post-concussion neurodysfunction and recovery between males and females. Females had greater probability of VVE abnormalities that peaked slightly later than males and took longer to resolve. This aligns with the growing knowledge from clinical and pre-clinical studies that sex influences injury severity as measured by symptom burden and recovery time course.23–26,51,52 Further work directed toward disentangling biological intrinsic factors from environmental extrinsic factors that are modifiable is critical.

The results related to concussion history are intriguing. Those with a concussion history demonstrated a higher and more immediate peak probability of abnormal VVE score. This might suggest that the brain, primed from a previous injury, accelerates the neurometabolical cascade more quickly and visio-vestibular deficits are more common and appear sooner.53 Chronic dysfunction of the blood–brain barrier, upregulation of certain proteins, and continued disruption of metabolic homeostatis as a result of previous injury have all been implicated as mechanistic pathways by which subsequent injuries have enhanced presentation.42,54

Somewhat unexpectedly, however, those with a concussion history reached the recovery plateau 24 days sooner than those with no concussion history. It is possible that this observation is ecological rather than physiological, in that patients who have experienced concussion previously may embrace the recovery management provided by their clinician more readily and know what approach was successful for them in the past. The impact of multiple injuries on the developing brain is a complex interplay of factors that deserves more detailed study.

A critical gap in knowledge in concussion management is the ability to prognosticate which patients will have prolonged recovery. Armed with this knowledge, a clinician could direct those predicted to have a longer time course to targeted interventions designed to accelerate improvement. We found those with prolonged recovery had close to a 90% probability of abnormal VVE immediately after injury—the highest proportion of any of our substrata and, while they plateau later by definition (day 55 vs. day 24), they do so with a higher residual probability of VVE abnormalities (0.29 vs, 0.14). Those who recover quickly are similar to healthy participants in the proportion with residual VVE abnormalities. These findings support the use of the VVE examination early in clinical presentation and suggest that, if by three to four weeks those deficits have not resolved, a prolonged course may be in store.

There are several limitations. Our study enrolled children aged 11–18 years; because of potential developmental differences in the VVE, the results should not be extrapolated to either younger pediatric or older adult populations. Participants were predominantly white, limiting the generalizability of our results. Last, because concussion cases were enrolled from a specialty care program, the injured cohort may be biased toward those with prolonged recovery. Our choice to model the trajectory of post-injury abnormal VVE probability with a cubic polynomial, while providing some additional flexibility relative to a linear model may not be sufficient to capture more complicated trajectories and adds complexity for multi-variate models incorporating all predictors simultaneously beyond what is feasible without a much larger sample size.

Conclusions

VVE deficits are common in youth after concussion, and probability modeling allows us to examine their time trajectory. The probability of these deficits peaks at approximately 60% one week after injury, and one-third retain visio-vestibular dysfunction at 60 days post-injury. The demographic substrata of age, sex, and concussion history are all associated with unique time courses of VVE abnormalities, with females, those older than 14 years, and those with a concussion history having a higher probability of VVE abnormalities. Overall, nine of 10 of those with prolonged recovery present with these deficits, suggesting that targeted interventions directed toward improvement of the visio-vestibular system may be appropriate and warrant further investigation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Ronni S. Kessler, MEd, Olivia E. Podolak, MD, Alexis Brzuchalski, MPH, Daniele Fedonni, MPH, Melissa Pfieffer, MPH, Anne Mozel, MS, Ari Fish, BS, Julia Vanni, BS, Taylor Valerio, BA, and Shelly Sharma, BA, of Children's Hospital of Philadelphia for their contributions to this study. In addition, we thank the students and parents from the Shipley School and adolescent patients from the Minds Matter Concussion clinic for their participation. We appreciate the support from the Shipley School administration, faculty, and athletic department: Steve Piltch, MEd, EdD, Mark Duncan, MEd, Katelyn Taylor, BS, Dakota Carroll, MS, Kimberly Shaud, BS, Kayleigh Jenkins, BS, and Michael Turner, MEd, without whose support this research would not have been possible.

Authors' Contributions

KA was responsible for the design of the study, analyzed the results, wrote, reviewed, and edited the manuscript; she has full access to the data and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. RG performed the statistical analysis, wrote the manuscript, and reviewed and edited the manuscript. DC, CCM, and SM participated in the design of the study, analyzed the results, contributed to the discussion, and reviewed and edited the manuscript. FM collected the data, contributed to the discussion, and reviewed and edited the manuscript. IB and CLM were responsible for the design of the study, analyzed the results, contributed to the discussion, and reviewed and edited the manuscript.

Funding Information

This work was supported in part by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke of the National Institutes of Health (R01NS0975NIH to SSM, KBA and CLM) and the Pennsylvania Department of Health (SAP4100077078 to KBA).

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1. Master CL, Scheiman M, Gallaway M, et al. Vision diagnoses are common after concussion in adolescents. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 2016;55(3):260–267. doi: 10.1177/0009922815594367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Scheiman M, Grady MF, Jenewein E, et al. Frequency of oculomotor disorders in adolescents 11 to 17 years of age with concussion, 4 to 12 weeks post injury. Vision Res 2021;183:73–80. doi: 10.1016/j.visres.2020.09.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Wiecek EK, Roberts TL, Shah AS, et al. Vergence, accommodation, and visual tracking in children and adolescents evaluated in a multidisciplinary concussion clinic. Vision Res 2021;184:30–36. doi: 10.1016/j.visres.2021.03.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Valovich McLeod TC, Hale TD. Vestibular and balance issues following sport-related concussion. Brain Inj 2015;29(2):175–184. doi: 10.3109/02699052.2014.965206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Howell DR, Osternig LR, Chou L-S. Adolescents demonstrate greater gait balance control deficits after concussion than young adults. Am J Sports Med 2015;43(3):625–632. doi: 10.1177/0363546514560994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Corwin DJ, McDonald CC, Arbogast KB, et al. Clinical and device-based metrics of gait and balance in diagnosing youth concussion. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2020;52(3):542–548. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0000000000002163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ketcham CJ, Cochrane G, Brown L, et al. Neurocognitive performance, concussion history, and balance performance during a distraction dual-task in collegiate student-athletes. Athl Train Sport Heal Care 2019;11(2):90–96. doi: 10.3928/19425864-20180313-02 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Master CL, Master SR, Wiebe DJ, et al. Vision and vestibular system dysfunction predicts prolonged concussion recovery in children. Clin J Sport Med 2018;28(2):139–145. doi: 10.1097/JSM.0000000000000507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Anzalone AJ, Blueitt D, Case T, et al. A positive vestibular/ocular motor screening (VOMS) is associated with increased recovery time after sports-related concussion in youth and adolescent athletes. Am J Sports Med 2017;45(2):474–479. doi: 10.1177/0363546516668624 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Quintana CP, Valovich McLeod TC, Olson AD, et al. Vestibular and ocular/oculomotor assessment strategies and outcomes following sports-related concussion: a scoping review. Sports Med 2021;51(4):737–757. doi: 10.1007/s40279-020-01409-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Swanson MW, Weise KK, Dreer LE, et al. Academic difficulty and vision symptoms in children with concussion. Optom Vis Sci 2017;94(1):60–67. doi: 10.1097/opx.000000000000977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ventura RE, Balcer LJ, Galetta SL. The concussion toolbox: the role of vision in the assessment of concussion. Semin Neurol 2015;35(5):599–606. doi: 10.1055/s-0035-1563567 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kontos AP, Deitrick JM, Collins MW, et al. Review of vestibular and oculomotor screening and concussion rehabilitation. J Athl Train 2017;52(3):256–261. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-51.11.05 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Mucha A, Collins MW, Elbin RJ, et al. A Brief Vestibular/Ocular Motor Screening (VOMS) assessment to evaluate concussions: preliminary findings. Am J Sports Med 2014;42(10):2479–2486. doi: 10.1177/0363546514543775 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Corwin DJ, Arbogast KB, Haber RA, et al. Characteristics and outcomes for delayed diagnosis of concussion in pediatric patients presenting to the emergency department. J Emerg Med 2020;59(6):795–804. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2020.09.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Corwin DJ, Arbogast KB, Swann C, et al. Reliability of the visio-vestibular examination for concussion among providers in a pediatric emergency department. am j emerg med 2020;38(9):1847–1853. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2020.06.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Corwin DJ, Propert KJ, Zorc JJ, et al. Use of the vestibular and oculomotor examination for concussion in a pediatric emergency department. Am J Emerg Med 2019;37(7):1219–1223. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2018.09.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Arbogast KB, Curry AE, Metzger KB, et al. Improving primary care provider practices in youth concussion management. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 2017;56(9):854–865. doi: 10.1177/0009922817709555 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Sinnott AM, Elbin RJ, Collins MW, et al. Persistent vestibular-ocular impairment following concussion in adolescents. J Sci Med Sport 2019;22(12):1292–1297. doi: 10.1016/j.jsams.2019.08.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Corwin DJ, Wiebe DJ, Zonfrillo MR, et al. Vestibular deficits following youth concussion. J Pediatr 2015;166(5):1221–1225. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2015.01.039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Elbin RJ, Sufrinko A, Anderson MN, et al. Prospective changes in vestibular and ocular motor impairment after concussion. J Neurol Phys Ther 2018;42(3):142–148. doi: 10.1097/NPT.0000000000000230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Brooks BL, Silverberg N, Maxwell B, et al. Investigating effects of sex differences and prior concussions on symptom reporting and cognition among adolescent soccer players. Am J Sports Med 2018;46(4):961–968. doi: 10.1177/0363546517749588 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Covassin T, Savage JL, Bretzin AC, et al. Sex differences in sport-related concussion long-term outcomes. Int J Psychophysiol 2018;132(Pt A):9–13. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2017.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Desai N, Wiebe DJ, Corwin DJ, et al. Factors affecting recovery trajectories in pediatric female concussion. Clin J Sport Med 2019;29(5):361–367. doi: 10.1097/JSM.000000000000646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Gray M, Wilson JC, Potter M, et al. Female adolescents demonstrate greater oculomotor and vestibular dysfunction than male adolescents following concussion. Phys Ther Sport 2020;42:68–74. doi: 10.1016/j.ptsp.2020.01.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Sufrinko AM, Mucha A, Covassin T, et al. Sex differences in vestibular/ocular and neurocognitive outcomes after sport-related concussion. Clin J Sport Med 2017;27(2):133–138. doi: 10.1097/JSM.0000000000000324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Henry LC, Elbin RJ, Collins MW, et al. Examining recovery trajectories after sport-related concussion with a multimodal clinical assessment approach. Neurosurgery 2016;78(2):232–241. doi: 10.1227/NEU.0000000000001041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Pearce KL, Sufrinko A, Lau BC, et al. Near point of convergence after a sport-related concussion. Am J Sports Med 2015;43(12):3055–3061. doi: 10.1177/0363546515606430 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Roby P, Storey E, Master C, et al. Visio-vestibular function of pediatric patients presenting with first concussion vs. a recurrent concussion. Inj Prev 2021;27(Suppl 3:A11-A12. doi: 10.1136/injuryprev-2021-SAVIR.29 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Howell DR, Beasley M, Vopat L, et al. The effect of prior concussion history on dual-task gait following a concussion. J Neurotrauma 2017;34(4):838–844. doi: 10.1089/neu.2016.4609 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. McCrory P, Meeuwisse W, Dvořák J, et al. Consensus statement on concussion in sport–the 5th international conference on concussion in sport held in Berlin, October 2016. Br J Sports Med. 2017;51(11):838–847. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2017-097699 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Storey EP, Corwin DJ, McDonald CC, et al. Assessment of saccades and gaze stability in the diagnosis of pediatric concussion. Clin J Sport Med 2022;32(2):108–113. doi: 10.1097/JSM.0000000000000897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Scheiman M, Cotter S, Kulp MT, et al. Treatment of accommodative dysfunction in children: results from a randomized clinical trial. Optom Vis Sci 2011;88(11):1343–1352. doi: 10.1097/OPX.0b013e31822f4d7c [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Lavrich JB. Convergence insufficiency and its current treatment. Curr Opin Ophthalmol 2010;21(5):356–360. doi: 10.1097/ICU.0b013e32833cf03a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Corwin DJ, Zonfrillo MR, Wiebe DJ, et al. Vestibular and oculomotor findings in neurologically-normal, non-concussed children. Brain Inj 2018;32(6):794–799. doi: 10.1080/02699052.2018.1458150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Sady MD, Vaughan CG, Gioia GA. Psychometric characteristics of the postconcussion symptom inventory in children and adolescents. Arch Clin Neuropsychol 2014;29(4):348–363. doi: 10.1093/arclin/acu014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, et al. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform 2009;42(2):377–381. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Zemek R, Barrowman N, Freedman SB, et al. Clinical risk score for persistent postconcussion symptoms among children with acute concussion in the ED. JAMA 2016;315(10):1014–1025. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.1203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Follmann D, Proschan M, Leifer E.. Multiple outputation: inference for complex clustered data by averaging analyses from independent data. Biometrics 2003;59(2):420–429. doi: 10.1111/1541-0420.00049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Master CL, Curry AE, Pfeiffer MR, et al. Characteristics of concussion in elementary school-aged children: implications for clinical management. J Pediatr 2020;223:128–135. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2020.04.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Giza CC, Hovda DA. The new neurometabolic cascade of concussion. Neurosurgery 2014;75 Suppl 4(0 4):S24-S33. doi: 10.1227/NEU.0000000000000505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. MacFarlane MP, Glenn TC. Neurochemical cascade of concussion. Brain Inj 2015;29(2):139–153. doi: 10.3109/02699052.2014.965208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Davis GA, Anderson V, Babl FE, et al. What is the difference in concussion management in children as compared with adults? A systematic review. Br J Sports Med 2017;51(12):949–957. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2016-097415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Storey EP, Wiebe DJ, D'Alonzo BA, et al. Vestibular rehabilitation is associated with visuovestibular improvement in pediatric concussion. J Neurol Phys Ther 2018;42(3):134–141. doi: 10.1097/NPT.0000000000000228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Murray DA, Meldrum D, Lennon O.. Can vestibular rehabilitation exercises help patients with concussion? A systematic review of efficacy, prescription and progression patterns. Br J Sports Med 2017;51(5):442–451. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2016-096081 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Park K, Ksiazek T, Olson B.. Effectiveness of vestibular rehabilitation therapy for treatment of concussed adolescents with persistent symptoms of dizziness and imbalance. J Sport Rehabil 2018;27(5):485–490. doi: 10.1123/jsr.2016-0222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Kontos AP, Eagle SR, Mucha A, et al. A randomized controlled trial of precision vestibular rehabilitation in adolescents following concussion: preliminary findings. J Pediatr 2021;239:193–199. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2021.08.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Gallaway M, Scheiman M, Mitchell GL. Vision therapy for post-concussion vision disorders. Optom Vis Sci 2017;94(1):68–73. doi: 10.1097/OPX.0000000000000935 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Santo AL, Race ML, Teel EF. Near point of convergence deficits and treatment following concussion: a systematic review. J Sport Rehabil 2020;29(8):1179–1193. doi: 10.1123/jsr.2019-0428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Ahluwalia R, Miller S, Dawoud FM, et al. A pilot study evaluating the timing of vestibular therapy after sport-related concussion: is earlier better? Sports Health 2021;13(6):573–579. doi: 10.1177/1941738121998687 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Master CL, Katz BP, Arbogast KB, et al. Differences in sport-related concussion for female and male athletes in comparable collegiate sports: a study from the NCAA-DoD Concussion Assessment, Research and Education (CARE) Consortium. Br J Sports Med 2021l55(24):1387–1394. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2020-103316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Bretzin AC, Covassin T, Wiebe DJ, et al. Association of sex with adolescent soccer concussion incidence and characteristics. JAMA Netw Open 2021;4(4):e218191. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.8191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Ellis M, Krisko C, Selci E, et al. Effect of concussion history on symptom burden and recovery following pediatric sports-related concussion. J Neurosurg Pediatr 2018;21(4):401–408. doi: 10.3171/2017.9.PEDS17392 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Ware JB, Sandsmark DK, Diaz-Arrastia R.. Unravelling the mechanisms of blood-brain barrier dysfunction in repetitive mild head injury. Brain 2020;143(6):1625–1628. doi: 10.1093/brain/awaa166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.