Abstract

Trust attitude is a social personality trait linked with the estimation of others’ trustworthiness. Trusting others, however, can have substantial negative effects on mental health, such as the development of depression. Despite significant progress in understanding the neurobiology of trust, whether the neuroanatomy of trust is linked with depression vulnerability remains unknown. To investigate a link between the neuroanatomy of trust and depression vulnerability, we assessed trust and depressive symptoms and employed neuroimaging to acquire brain structure data of healthy participants. A high depressive symptom score was used as an indicator of depression vulnerability. The neuroanatomical results observed with the healthy sample were validated in a sample of clinically diagnosed depressive patients. We found significantly higher depressive symptoms among low trusters than among high trusters. Neuroanatomically, low trusters and depressive patients showed similar volume reduction in brain regions implicated in social cognition, including the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC), dorsomedial PFC, posterior cingulate, precuneus, and angular gyrus. Furthermore, the reduced volume of the DLPFC and precuneus mediated the relationship between trust and depressive symptoms. These findings contribute to understanding social- and neural-markers of depression vulnerability and may inform the development of social interventions to prevent pathological depression.

Subject terms: Social behaviour, Social neuroscience, Predictive markers, Psychiatric disorders

Introduction

Major depressive disorder (MDD) is a pervasive mental health condition that affects millions of people worldwide1–3. Social issues substantially contribute to the development of MDD, including diverse matters such as income inequality, gender, and racial discrimination, violence, harassment, parental separation, child abuse, social conflict, and social isolation4–13. Given the burden that aversive social interactions cause on mental health, several studies have attempted to identify whether and which social personality traits operate as premorbid risk factors for depression vulnerability. Individual differences in social personality traits, such as high neuroticism, agreeableness, and extraversion or low concern about others’ welfare and low trust in others have been shown to predict future depressive states and symptoms, including pathological depression14–31. At the biological level, despite the well-established functional and anatomical neurobiology of MDD32–38, only a few studies have investigated the neural substrates underlying the link between social personality traits and the development of depression31,39,40, but no study has addressed whether the neurobiology of trust plays a role in the expression of depressive symptoms.

Trust, a social personality trait linked with the cognitive ability to analyze social cues and estimate others’ trustworthiness, such as whether to expect reciprocal cooperation or observance of social norms, plays a fundamental role in the quality of interpersonal relations41,42. Estimating others’ trustworthiness and actual trust behavior are important not only for the initiation and maintenance of daily social relations but also impact large-scale issues such as political representation, military coalitions, international economic trade, and stability of democracies41–45. Trust influences not only the fabric of social relations, but the lack and breach of trust exert substantial negative effects on public welfare and mental health28,42,46,47. For instance, following an influential suggestion that lack of trust disrupts well-being28, multiple studies have consistently linked low levels of trust with MDD across different cultures29,30,48–52. At the biological level, several studies have investigated the genetic53–55, hormonal56–58, neuroanatomical59–61, and neurofunctional bases of trust62–64. There have also been attempts to identify abnormalities in the neural control of trust in patients clinically diagnosed with psychiatric disorders62,65,66, although it remains unknown whether similar abnormalities in the neurobiology of trust may also be present in healthy individuals with a non-clinical diagnosis of depression but exhibiting depressive symptoms.

Our previous studies have identified several social and psychological factors associated with trust42,67–76. Our studies on the neurobiology of trust have also shown an association between trust and volume of the amygdala with a polymorphism of the oxytocin hormone54,55. Despite the significant impact that trust exerts on mental health and social relations, often culminating in a significant personal and social cost, including health problems such as depression, work burnout, and break of social relationships29,46,47,77,78, it remains unclear whether the neurobiology of trust underlies its association with mental health. More specifically, it remains unknown whether low trust is associated with abnormally reduced gray matter volume of brain structures previously observed in MDD patients and linked with the degree of currently experienced depressive symptoms. To elucidate this issue and understand how the neuroanatomy of trust may be linked with the development of psychiatric disorders, the present study sought to investigate whether the neuroanatomy (e.g. regional gray matter volume) of trust was linked to individual differences in the severity of depressive symptoms in healthy human subjects with no formal clinical diagnosis of MDD. Determining not only the link between trust and mental health but also whether its underlying neurobiological substrates contribute to depression vulnerability may help advance early social and non-invasive neural interventions to combat and prevent the development of pathological depression.

One important psychological factor our research discovered is that high trusters are more accurate at recognizing and using social cues to evaluate the risk of engaging in interpersonal relations with potential aversive outcomes, whereas low trusters tend to overestimate the risk and negative outcomes of being deceived by others and avoid social interactions with uncertain outcomes42,69,72,73. These findings suggest that low trusters may exhibit increased anxiety due to the possibility of being taken advantage of by others when leaving oneself in a vulnerable situation that the decision to trust others presents. Furthermore, the constant use of a social avoidance strategy to protect oneself against others’ selfish behaviors suggests that low trusters may participate in a smaller social network, while high trusters may have an expanded social network. Previous studies have demonstrated a significant link between depression, high anxiety, and reduced social participation79–83. In light of our previous results and the latter findings, we also investigated the association of trust with social anxiety and social network size.

To identify the neuroanatomical basis of the relationship between trust and depression vulnerability, we used magnetic resonance imaging to acquire gray matter (GM) volume data from a large sample of healthy participants from a large-scale study (Tamagawa Sample) conducted at Tamagawa University (Tokyo, Japan). We used psychological questionnaires to assess individual differences in trust, social anxiety and social network size and a psychiatric questionnaire where participants self-reported about their current degree of experienced depressive symptoms. High self-reported depressive symptoms were used as an indicator of depression vulnerability. Furthermore, to reliably demonstrate that brain regions linked to trust and depressive symptoms are related to actual neuroanatomical abnormalities commonly observed in MDD, we also investigated GM volume abnormalities in patients clinically diagnosed with MDD from another large-scale study (Hiroshima Sample), conducted at Hiroshima University Hospital (Hiroshima, Japan).

Results

Results 1: low trust linked with depression vulnerability, social anxiety and social network size

To investigate the relationship between trust and depressive symptoms, trust was measured twice with the 5-item Yamagishi general trust attitude scale42 (see “Methods”). The first assessment of trust (TA1) was performed about 17 months before the assessment of depressive symptoms and the second (TA2) was performed about 6 months prior to it. Depressive symptoms were measured with the Beck Depression Inventory I (BDI-I) and BDI-II scales which are psychiatric scales commonly used to establish a prognosis of pathological depression84,85. The precedence of trust and neuroanatomical data acquisition was important to examine the predictive power of these measures for subsequent depressive symptoms of the same subjects. Unless otherwise specified, here we present all statistical analyses using the BDI-II scores as this scale was commonly used in the Tamagawa and Hiroshima samples and has been revised to address new criteria for clinical diagnosis of MDD.

Pearson correlation analyses (two-tailed, controlling for age, sex, education and income) revealed significant negative correlations between TA1 and BDI-II scores (r = –0.22, P = 0.000002, Fig. 1A) and between TA2 and BDI-II scores (r = –0.14, P = 0.0025). Social anxiety also showed significant negative correlation with TA1 (r = –0.16, P = 0.0006) and TA2 (r = –0.13, P = 0.0074). Positive correlations were found between social network size and TA1 (r = 0.11, P = 0.0197) and TA2 (r = 0.17, P = 0.0006). The two trust measurements (TA1 and TA2) were also significantly positively correlated (r = 0.64, P < 0.0000001), an association that also remained significant after controlling for age, sex, education, and income (r = 0.6, P < 0.0000001).

Figure 1.

Trust and depressive symptoms. (A) Significant negative correlation between trust (TA1) and depressive symptoms measured up to 17 months apart. (B) Significant higher depressive symptoms in low trusters relative to middle and high trusters. The three groups were created based on their trust scores (TA1). (C) The distribution of depressive symptoms among low trusters was significantly skewed toward higher values relative to middle and high trusters.

To demonstrate the robustness of the relationship between trust and depressive symptoms, participants were classified into three groups based on their TA1 scores (low trusters: bottom 33.33%, middle trusters: middle 33.33%, and high trusters: top 33.33%). An ANCOVA (controlling for age, sex, education and income) found a significant group effect on BDI-II scores (F[2,463] = 7.07, P = 0.0009, Table S1). A post-hoc analysis (Bonferroni corrected with a statistical threshold of PBonf < 0.05) revealed significantly higher BDI-II scores among low trusters relative to middle trusters (PBonf = 0.0482, Fig. 1B) and high trusters (PBonf = 0.0007, Fig. 1B), but not between middle trusters and high trusters (PBonf = 0.5020). Similar findings were observed when trust group classification was based on TA2 (Table S1). Significant differences in the distribution of BDI-II scores were observed between low trust and high trust groups (k = 0.2243, P = 0.0007, Fig. 1C), a marginally significant difference between low trust and middle trust groups (k = 0.1424, P = 0.0783), but not between middle trust and high trust groups (k = 0.09, P = 0.5084). Altogether, these findings demonstrate that low trust is significantly associated with high depressive symptoms, high social anxiety and smaller social network size.

Results 2: the neuroanatomy of trust

We next sought to investigate the neuroanatomical substrates of trust with a focus on the GM volume of brain regions previously implicated in social cognition and trust, namely the middle frontal gyrus (as a representative of the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, DLPFC), dorsomedial prefrontal cortex (DMPFC), ventromedial prefrontal cortex (VMPFC), temporal parietal junction (TPJ: supramarginal and angular gyri), precuneus, posterior cingulate cortex (PCC), and amygdala31,62,64,86–97.

Regional GM volumes of social brain regions were extracted using an automated neuroimaging parcellation method based on neuroanatomical landmarks provided by the Neuromorphometrics brain atlas (see “Methods”, Table S2). Pearson correlations (two-tailed, controlling for age, sex, and total intracranial volume—TIV) revealed an association between increased GM volume of social brain regions with higher trust scores. Significant positive correlations (following False Discovery Rate, FDR, correction) were found between trust (TA1) and GM volumes of the left DLPFC (r = 0.11, PFDR = 0.0394), right DLPFC (r = 0.12, PFDR = 0.0394), left DMPFC (r = 0.18, PFDR = 0.0020), right DMPFC (r = 0.13, PFDR = 0.0210), left PCC (r = 0.12, PFDR = 0.0340), left precuneus (r = 0.17, PFDR = 0.0020), and right precuneus (r = 0.16, PFDR = 0.0033). Similar findings were observed between the second assessment of trust (TA2) and GM volume of social brain regions (Table 1).

Table 1.

Social brain regions linked with trust and depressive symptoms.

| Area name | Hemisphere | Atlas name | General trust | General trust | Depressive symptoms | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GT1 | GT2 | BDI-II | |||||||||

| r-coeff | P-unc. | P-FDR | r-coeff | P-unc. | P-FDR | r-coeff | P-unc. | P-FDR | |||

| Amygdala nuclei | |||||||||||

| Amygdala | Left | lAmy | 0.08 | 0.0879 | 0.1256 | 0.03 | 0.4790 | 0.5322 | −0.08 | 0.0821 | 0.1263 |

| Amygdala | Right | rAmy | 0.06 | 0.1744 | 0.2180 | −0.01 | 0.8288 | 0.8724 | −0.07 | 0.1802 | 0.2253 |

| Dorsolateral prefrontal cortex | |||||||||||

| Middle frontal gyrus | Left | lMidFroGy | 0.11 | 0.0138 | 0.0394 | 0.13 | 0.0060 | 0.0200 | -0.15 | 0.0021 | 0.0210 |

| Middle frontal gyrus | Right | rMidFroGy | 0.12 | 0.0124 | 0.0394 | 0.18 | 0.0002 | 0.0040 | -0.14 | 0.0042 | 0.0210 |

| Dorsomedial prefrontal cortex | |||||||||||

| Superior medial frontal gyrus | Left | lSupMedFroGy | 0.18 | 0.0001 | 0.0020 | 0.14 | 0.0036 | 0.0144 | -0.11 | 0.0250 | 0.0455 |

| Superior medial frontal gyrus | Right | rSupMedFroGy | 0.13 | 0.0042 | 0.0210 | 0.11 | 0.0179 | 0.0511 | -0.07 | 0.1757 | 0.22525 |

| Ventromedial prefrontal cortex | |||||||||||

| Frontal pole | Left | lFroPo | 0.09 | 0.0545 | 0.0838 | 0.07 | 0.1285 | 0.2336 | -0.02 | 0.6980 | 0.7756 |

| Frontal pole | Right | rFroPo | 0.10 | 0.0283 | 0.0515 | 0.07 | 0.1720 | 0.2646 | -0.11 | 0.0203 | 0.0426 |

| Rectus gyrus | Left | lRecGy | 0.06 | 0.2080 | 0.2334 | 0.05 | 0.3073 | 0.4097 | -0.09 | 0.0539 | 0.0898 |

| Rectus gyrus | Right | rRecGy | 0.11 | 0.0171 | 0.0428 | 0.10 | 0.0404 | 0.0898 | -0.05 | 0.3034 | 0.3569 |

| Ventromedial frontal area | Left | lMedFroCbr | 0.02 | 0.7430 | 0.7430 | 0.01 | 0.8810 | 0.8810 | -0.01 | 0.7844 | 0.8109 |

| Ventromedial frontal area | Right | rMedFroCbr | 0.07 | 0.1557 | 0.2076 | 0.05 | 0.3342 | 0.4178 | -0.01 | 0.8109 | 0.8109 |

| Temporo-parietal junction | |||||||||||

| Angular gyrus | Left | lAngGy | 0.10 | 0.0390 | 0.0650 | 0.09 | 0.0640 | 0.1280 | -0.11 | 0.0213 | 0.0426 |

| Angular gyrus | Right | rAngGy | 0.10 | 0.0279 | 0.0515 | 0.14 | 0.0029 | 0.0144 | -0.11 | 0.0187 | 0.0426 |

| Supramarginal gyrus | Left | lSupMarGy | 0.05 | 0.3083 | 0.3245 | 0.07 | 0.1584 | 0.2640 | -0.12 | 0.0122 | 0.0407 |

| Supramarginal gyrus | Right | rSupMarGy | 0.06 | 0.2101 | 0.2334 | 0.04 | 0.4261 | 0.5013 | -0.07 | 0.1593 | 0.2253 |

| Posterior cingulate-precuneus | |||||||||||

| Posterior cingulate cortex | Left | lPosCinGy | 0.12 | 0.0085 | 0.0340 | 0.10 | 0.0402 | 0.0898 | -0.12 | 0.0105 | 0.0407 |

| Posterior cingulate cortex | Right | rPosCinGy | 0.10 | 0.0264 | 0.0515 | 0.06 | 0.2001 | 0.2859 | -0.14 | 0.0036 | 0.0210 |

| Precuneus | Left | lPCu | 0.17 | 0.0002 | 0.0020 | 0.17 | 0.0005 | 0.0050 | -0.14 | 0.0030 | 0.0210 |

| Precuneus | Right | rPCu | 0.16 | 0.0005 | 0.0033 | 0.16 | 0.0012 | 0.0080 | -0.11 | 0.0202 | 0.0426 |

Partial correlations showing the relationship between gray matter volume of social brain regions, trust and depressive symptoms. All analyses controlled for effects of age, sex, education, income and TIV. Brain regions with names highlighted in bold font are significantly associated with both trust and depressive symptoms. P-values in bold survived FDR correction.

Analysis of covariance with trust group as a factor (low trusters, middle trusters, high trusters), also demonstrated a significant relationship between trust level and GM volumes of social brain regions. Low trusters showed significant GM volume reduction, relative to high trusters, in the left angular gyrus (PBonf = 0.0072), right angular gyrus (PBonf = 0.0081), left DLPFC (PBonf = 0.0305), right frontal pole (PBonf = 0.0417), right rectus gyrus (PBonf = 0.0489), left DLPFC (PBonf = 0.0371), right DLPFC (PBonf = 0.0371), left DMPFC (PBonf = 0.0023), right DMPFC (PBonf = 0.0137), left PCC (PBonf = 0.0224), left Precuneus (PBonf = 0.0001) and right Precuneus (PBonf = 0.0005) (Fig. 2, Table S3).

Figure 2.

Reduced volume of social brain regions among low trusters. Social brain regions positively associated with trust (Table 1) also showed robust group differences when participants were classified as low trusters, middle trusters and high trusters. Population marginal means and error bars (standard error) were calculated with ANCOVA and all P-values are Bonferroni corrected for multiple comparisons. Gray matter volume is adjusted for age, sex, education, income and TIV.

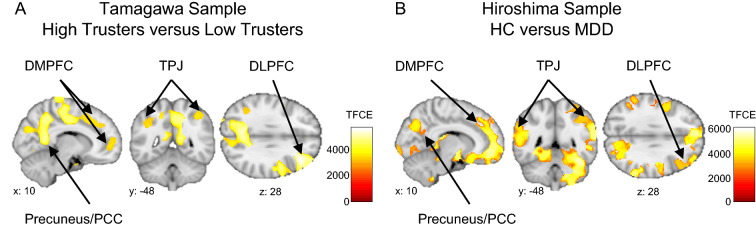

A whole-brain voxel-based morphometry (VBM) analysis (controlling for age, sex, education, income and TIV) using a permutation method also demonstrated significant enlargement of social brain regions among high trusters relative to low trusters, including the DLPFC, DMPFC, PCC, precuneus and amygdala (PFWE < 0.05, corrected for the whole-brain) (Fig. 3A, Table S4).

Figure 3.

Whole-brain VBM analyses of trust and depressive symptoms. (A) Social brain regions with increased gray matter volume in high trusters relative to low trusters. Highlighted brain regions include the MFG, DMPFC, precuneus, posterior cingulate and angular gyrus. (B) Enlargement of social brain regions in healthy controls relative to MDD patients in the Hiroshima sample. Both analyses were performed using a non-parametric permutation method and a statistical threshold of PFWE < 0.05, family-wise error corrected for the whole-brain.

Results 3: the neuroanatomy of trust linked with depressive vulnerability

High depressive symptoms (BDI-II scores) were significantly associated with reduced GM volumes of social brain regions associated with trust (Table 1). Trust brain regions with reduced GM volumes linked with high depressive symptoms included the left DLPFC (r = –0.15, PFDR = 0.0210), right DLPFC (r = –0.14, PFDR = 0.0210), left DMPFC (r = –0.11, PFDR = 0.0455), right VMPFC (frontal pole, r = –0.11, PFDR = 0.0426), left angular gyrus (r = –0.11, PFDR = 0.0426), right angular gyrus (r = –0.11, PFDR = 0.0426), left supramarginal (r = –0.12, PFDR = 0.0407), left PCC (r = –0.12, PFDR = 0.0407), right PCC (r = –0.14, PFDR = 0.0210), left precuneus (r = –0.14, PFDR = 0.0210) and right precuneus (r = –0.11, PFDR = 0.0426). These findings indicate that reduced GM volumes of social brain regions, especially of the bilateral DLPFC, left DMPFC, left PCC and bilateral precuneus, are linked with both low trust and high depressive symptoms.

Results 4: social brain structures linked with MDD in the Hiroshima sample

Despite an interval of about 17 months between acquisition of brain structure data to administration of the BDI-II scale in the Tamagawa Sample, the above neuroanatomical results are consistent with previous findings in which both depressive symptoms and brain structure data were acquired on the same day98–100. However, in order to reliably demonstrate that reduced GM volumes of social brain regions associated with both low trust and high depressive symptoms in the Tamagawa Sample may represent a feature of a depressed brain, we conducted a whole-brain VBM analysis to investigate GM volume differences between healthy controls (HC) and MDD patients in the Hiroshima Sample. This analysis revealed significant GM volume reduction among MDD patients, relative to HC, in social cognitive brain areas including the DLPFC, DMPFC, VMPFC, PCC, precuneus, TPJ, insula, amygdala (PFWE < 0.05, corrected for the whole-brain) (Fig. 3B, Table S5).

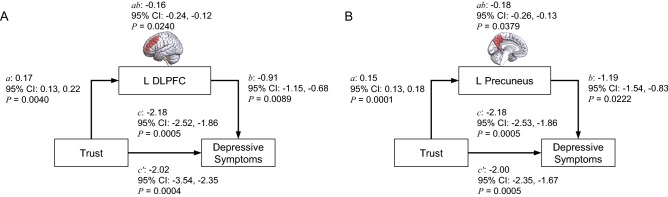

Results 5: DLPFC and precuneus volumes mediate the relationship between trust and depression vulnerability

Given that GM volumes of social brain regions showed a consistent relationship with both trust and depressive symptoms (Table 1), we performed mediation analyses to investigate whether volumes of social brain regions served a mediation function in the relationship between trust and depressive symptoms. In these analyses we treated trust (TA1) as the independent variable, BDI-II scores as the dependent variable and GM volumes of social brain structures as mediators of the relationship between trust and depressive symptoms (see “Methods”). These analyses revealed significant mediation effects of the volume of the left DLPFC (indirect path ab coeff: –0.16; confidence interval: –24, –12; P = 0.0240) and volume of the left precuneus (indirect path ab coeff: –0.18; confidence interval: –26, –13; P = 0.0379) on the relationship between trust and depressive symptoms (Fig. 4, Table S6).

Figure 4.

Mediation role of social brain regions on the link between trust and future depressive symptoms. Mediation analysis revealed significant indirect effects of GM volume of the left DLPFC (A) and left precuneus (B) on the relationship between trust and future depressive symptoms.

Discussion

The present study investigated the underlying neuroanatomy of trust and its association with depression vulnerability measured as the degree of self-reported depressive symptoms in a sample of healthy participants. We found a previously unknown association between GM volume of brain regions linked with both trust and depressive symptoms. Low trust was significantly associated with reduced GM volumes of brain regions implicated in social cognition, including the dorsolateral and dorsomedial PFC, TPJ, PCC and precuneus. Strikingly, reduced GM volumes of the same brain regions associated with low trust were also associated with high depressive symptoms in our healthy sample and were also observed in a sample of MDD patients when compared to health controls. Furthermore, our analyses also demonstrated that GM volumes of the left DLPFC and precuneus mediated the relationship between trust and depressive symptoms.

The present findings, demonstrating a significant association between low trust and high depressive symptoms in our Japanese sample, suggest that low trusters exhibit greater vulnerability to depression and are consonant with those of previous studies linking low trust with MDD in different cultures, such as the United States29, Korea48, China49, South Africa50, Sweden51 and Finland52. Our results also add to the vast literature demonstrating a link between multiple social personalities and vulnerability to development of depression5,31,101–104 and suggest that low trust toward others may be used as a reliable biosocial marker to predict depression vulnerability across different cultures.

The main finding of the present study was the demonstration of a previously unknown association that the GM volumes of social brain regions linked with low trust are also associated with high depressive symptoms. Our structural neuroimaging analyses revealed that both low trust and high depressive symptoms are linked with reduced GM volumes of the bilateral angular gyrus, bilateral DLPFC, bilateral DMPFC, bilateral precuneus, VMPFC (right frontal pole and right rectus gyrus) and left PCC. The whole-brain VBM analysis also revealed a negative relationship between trust and GM volume of the parahippocampus-amygdala region. The causes of volume reductions of social brain regions linked with both low trust and high depressive symptoms have yet to be identified. Since the present study did not longitudinally track the aversive social experiences contributing to reduced trust and a consequent increase in depressive symptoms, we cannot establish a causality between low trust and an increase in depression vulnerability. Also, since none of our participants in the Tamagawa sample have been formally diagnosed with MDD, we cannot confidently attribute the reduced GM volumes of social brain regions linked with low trust and high depressive symptoms to possible neurodegenerative processes reported in MDD105–111. Furthermore, to date only one longitudinal epidemiological study has attempted to establish a causal link between low trust and future diagnosis of MDD29. Thus, we will limit our following discussion on individual differences in brain structure linked with both low trust and high depression vulnerability to genetic or experience-driven neural plasticity processes.

Genetic processes may explain neuroanatomical differences linked to low trust and high depressive symptoms as demonstrated by studies showing heritability of GM volume in humans, including prefrontal and posterior cingulate cortices, and amygdala112–114. Family studies also suggest a genetic factor in heritability of brain structure and development of depression. For instance, neuroimaging studies have shown that family relatives at high risk of depression also exhibit abnormalities in the volumes of social brain structures similar to those observed in family members with MDD115–119. In support of this genetic interpretation, our work and others have shown that individual differences in trust and in amygdala volume, a region identified in the present study, have been associated with oxytocin receptor gene (OXTR) polymorphism53–55. However, future studies are needed to investigate whether and what genetic polymorphisms may underlie the link of reduced GM volumes of social brain regions with low trust and depression vulnerability.

Experience-dependent neuroanatomical plasticity driven by the use of distinct social strategies may also explain the reduced GM volumes of social brain regions associated with both low trust and high depressive symptoms. For instance, behavior studies link higher trust with types of experiences in childhood, levels of intelligence in early adolescence, and with higher accuracy in adulthood at recognizing social cues and evaluating the risk of engaging in social relations, quick learning of other’s past behaviors in order to respond appropriately, exploration of new relationships, and learning richer models of a partner’s behaviors42,120–129. In line with this social experience-dependent view of neuroanatomical plasticity, social brain regions with reduced GM volumes linked with low trust and high depressive symptoms in the current study have been implicated in several aspects of social cognition and experience, such as social deliberation in DLPFC87,89,93,95, moral reasoning and valuation in the VMPFC130–132, theory-of-mind and empathy in the DMPFC and TPJ133,134, switching and focusing attention to social context in the PCC135–137, self-perspective and in-group attitude in the precuneus138, as well as in realization of trust-based learning and decision-making57,59–61,63,64,139–141. Neuroanatomical plasticity and enlargement of social brain regions, such as the prefrontal and cingulate cortices and the amygdala, has been reported in monkeys ascending social group hierarchy91 and in humans undergoing social mental training142. Based on these findings, it is reasonable to speculate that higher use of the functions of social brain regions by high trusters may trigger volume enlargement of these regions and may support higher resilience to development of depressive symptoms. Further studies may help determine how social experiences, specifically those that rely on trust-based cognitive processes, lead to either enlargement or reduction in GM volumes of social brain regions and contribute to depression vulnerability.

How dysfunctions in trust-based cognitive processes contribute to vulnerability and development of depressive symptoms remains obscure. Here, we focus on the negative social bias that characterizes low trust, which is the constant expectation of aversive outcomes from uncertain social interactions42. We speculate that this constant negative bias to hypothetical future aversive events resembles rumination or repetitive thoughts about experienced distressful events that predict development of depression and that are frequently observed in MDD patients143–145. This negative bias may lead low trusters to exhibit higher social anxiety and avoidance of social interactions, which may contribute to development of depressive symptoms, such as reduced mood and motivation, sense of discouragement, unhappiness and loss of social interest (as measured by the BDI scale). In support of this view, studies with adolescents have shown an association of low trust and high rumination with depressive symptoms146,147. Our present findings also revealed a significant association of low trust with high social anxiety and reduced social network. Given the association between anxiety, social network and depression148,149, one could argue that the development of higher levels of depressive symptoms, such as observed among low trusters, may be facilitated by their high social anxiety, reduced social networks and consequent reduced access to social support.

Trust has been associated with other personality traits with distinct cognitive characteristics that have been linked with depression, such as neuroticism, extraversion and egocentrism150–153. Among these personalities, neuroticism is characterized by high suspicion about other’s intentions, which is similar to low trusters’ constant expectation of other’s untrustworthy behaviors. Thus, while trust-based cognitive processes may contribute to depression vulnerability, we cannot rule out cognitive processes shared between trust and other personality traits which may be present within the same individual. Future studies are needed to demonstrate how trust and other cognitive processes, such as rumination or neuroticism, contribute to social isolation and development of depressive symptoms.

Understanding how trust-related psychological processes, e.g., negative bias and estimation of trustworthiness, and brain structures interact to contribute to depression vulnerability is a work in progress. A candidate explanation comes from our mediation analyses showing that, among the 11 brain regions associated with both trust and depression vulnerability, the link between low trust and high depressive symptoms was significantly mediated by the reduced volume of only two social brain regions, the DLPFC and precuneus (Fig. 4). As described above, functions of the DLPFC and precuneus have been implicated in trust-based processes, model-based decision-making, social deliberation, and theory-of-mind93,95,133,138,154–157. The social functions of the DLPFC and precuneus can be interpreted under the more integrative approach of the active inference framework, which suggests that the brain uses generative models to make predictions of expected sensory data158–160. According to active inference models, failures in the generation of context-based predictions (e.g. results of own actions or the behavior of others) and in the estimation of confidence of those predictions or in updating of generative models (e.g. stored representations of other’s behavior patterns) at the different levels of the neural hierarchy may contribute to the vulnerability and development of depression161–163. Based on the active inference framework, we speculate that reduced volumes of the DLPFC and precuneus among low trusters may weaken their social predictive functions and impair the learning or updating of social models. Thus, the increased depression vulnerability of trusters may be associated with the generation of suboptimal social predictions, such as an exaggerated negative bias in the form of a constant expectation of aversive outcomes to yet to happen social interactions, and lower social exploration given their increased social anxiety and reduced social network. Consistent with this active inference interpretation of trust, poor cognitive processes, such as those observed among low trusters, have been implicated in the development and neuropathology of depression86,164–179. In addition, transcranial magnetic stimulation, neurofeedback, and functional neuroimaging studies suggest that strengthened activity and connectivity of the DLPFC and precuneus decrease the severity of depressive symptoms observed in MDD patients37,180–183. Overall, our findings suggest that continuous, poor use of social cognitive processes by low trusters, possibly due to weakening of social predictive functions, especially of the DLPFC and precuneus due to their reduced gray matter volume, may facilitate depression vulnerability.

In conclusion, the present study revealed that reduced GM volumes of social brain regions mediate the relationship between low trust and high depressive symptoms. Despite restricting our analyses to neuroanatomical brain data in healthy participants, the neuroanatomical abnormalities observed among low trusters resembled those of MDD patients in the present study and also the functional and connectivity dysfunctions in social brain regions reported in previous studies with MDD patients37,38,182–184. The present findings may inform social policies, behavioral and non-invasive neural interventional strategies that may be used to increase social trust, restore social predictive and cognitive processes, and reduce depression vulnerability. For instance, higher behavioral trust is observed following administration of oxytocin by nasal spray57, and the balance of oxytocin in the brain has been suggested as a potential treatment for anxiety and depression185. The use of cognitive behavioral therapy, previously shown to modulate the activity of social brain regions and improve self-reported quality-of-life in subthreshold depression patients184 may also be used as a social cognitive intervention to increase social trust and prevent depression. Finally, the successful demonstration that learning to control the neural activity of social brain regions by neurofeedback training can reduce the severity of depressive symptoms182,183,186 also suggests the potential use of neurofeedback methods to prevent depression vulnerability in low trusters. Our findings demonstrate that neuro-social markers comprised of social personality trait and neuroanatomical information may enable early identification of individuals at higher risk of depression and development of preventive therapeutical interventions.

Methods and materials

Tamagawa sample, data acquisition and analysis

Both behavioral and MRI studies were conducted at the Brain Science Institute of Tamagawa University. The study protocol was approved by the Tamagawa University Brain Science Institute Ethics Committees, and all experiments were conducted in accordance with the approved protocol, which met requirements of the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was provided by each participant prior to participation in the study.

The data and methods used to select participants and process structural neuroimaging data have been reported in details in our previous studies95,187. Six hundred non-student residents living in and around Machida, a suburb of Tokyo, were selected from a list of approximately 1670 applicants who responded to a brochure that had been distributed to roughly 180,000 households. Following invitation, only 564 (F = 290, M = 273) participated in the initial wave of the study in which demographic data and structural neuroimaging data were collected. One participant was excluded from the study for inconsistent responses to demographic items. Of the remaining 563 participants, we acquired valid brain imaging data of 470 participants. Participants visited the lab in several waves to answer questionnaires and participate in behavior experiments. See Table S7 for the timeline of data reported in the present study.

Trust was measured with the 5-item, 7-point Yamagishi scale42, which includes the items: (i) most people are basically honest; (ii) generally, I trust others; (iii) most people are basically good-natured and kind; (iv) most people trust others; (v) most people are trustworthy. Social anxiety was measured with the Social Interaction Anxiety Scale188. Social network size was measured with the Cohen’s social ties questionnaire189.

High-resolution T1-weighted neuroanatomical images were acquired using a 3 T Siemens Trio A Tim MRI scanner and rapid acquisition gradient echo (MPRAGE) sequence (TR = 2000 ms; TE = 1.98 ms; field of view = 256 × 256 mm; number of slices = 192; voxel size = 1 × 1 × 1 mm; average = 3 times).

Brain structural T1-weighted images were processed and analyzed using the Computational Anatomy Toolbox (CAT12, http://dbm.neuro.uni-jena.de/cat/) and Statistical Parametric Mapping software (SPM12, http://www.fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk/spm). Images were bias-corrected, tissue-classified (gray matter, GM; white matter, WM; and cerebral spinal fluid, CSF), and registered using linear (12-parameter affine) and non-linear transformations (warping) within the CAT12 default pre-processing pipeline. This initial step generated modulated normalized data that were then smoothed via the standard SPM12 smoothing pipeline with a full-width at half-maximum smoothing kernel of 8 × 8 × 8 mm. Overall GMV, WMV, CSF volume, and total intracranial volume (TIV) were then obtained using the CAT12 TIV estimation function. CAT12 uses the Neuromorphometrics brain atlas for volume estimation of cortical and subcortical brain areas in native space. Details of this neuroanatomical parcellation process can be found in the CAT12 software.

Estimated Neuromorphometrics ROI GM volumes were used to perform statistical. We used Matlab to perform partial correlations to investigate the relationship of ROI GM volumes with trust and depressive symptoms. Given the large dataset used in the present study, all behavior analyses controlled for the effect of age, sex, education and income, whereas relationships with ROI GM volumes included an additional control for TIV.

Analysis of Covariance (ANCOVA) with Matlab was used to investigate group differences (low trust, middle trust, high trust) in regional GM volumes. These analyses included as covariates age, sex, education, income and TIV. Group differences in depressive symptoms (altruistic × selfish; low trust, middle trust and high trust) were also investigated with ANCOVA and included as covariates age, sex, education and income.

A whole-brain VBM analysis was conducted to group differences (low trust × high trust) in GM volumes. This analysis controlled for effects of age, sex, education, income and TIV. Voxel clusters reached significance if they survived statistical cluster correction (PFWE < 0.05). Given the significant results found with parcellation data, we further used small-volume correction at the peak voxel of a ROI (as described in the “Introduction”) with a statistical threshold of PFWE < 0.05. The statistical SPM model generated in the above analysis was then used in a whole-brain VBM permutation test using the threshold-free cluster enhancement (TFCE) method implemented by the TFCE toolbox (http://www.neuro.uni-jena.de/tfce/). Results were considered significant if clusters exceeded a whole-brain correction threshold of PFWE < 0.05.

Mediation analyses were performed to identify whether social brain regions linked with both trust and depressive symptoms (Table 1) contributed to the link between trust and future depressive symptoms. In these analyses we used the Mediation Toolbox (https://canlab.github.io/repositories/) and implemented a bootstrap method with 10,000 iterations treating each volume of a social brain region as a mediator, the level of trust as the independent variable, and the degree of depressive symptoms as the dependent variable.

Hiroshima sample, acquisition and data analysis

Patients with MDD (n = 81) and healthy controls (HC, n = 104), all right-handed Japanese citizens, were included in the study (Supplementary Table ST1). Patients participating in this study were outpatients at Hiroshima University Hospital or other medical institutions located in Hiroshima, Japan. Newspaper advertisements were used to recruit HC participants with no previous history of psychiatric disorders. Diagnosis of MDD was performed by an expert clinician following criteria according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5). In order to increase diagnosis validity, the Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI) was also administered to patients and HC participants to confirm the absence of other psychiatric disorders. The Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II) was administered to all participants. The study followed the 1975 Helsinki Declaration of ethics principles for research involving humans and was approved by the Ethics Committee of Hiroshima University. Participants were required to sign a written informed consent form and received financial compensation for their participation. Structural MR images of Hiroshima Data were obtained using a 3 T Siemens Verio scanner with following parameters (MPRAGE, TR = 2300 ms; TE = 2.98 ms; field of view = 256 × 256 mm; number of slices = 176; voxel size = 1 × 1 × 1 mm).

Structural images were segmented into gray matter, white matter, cerebrospinal fluid, and normalized (1 × 1 × 1 voxel size) into a template space using standard parameters implemented in the Computational Neuroanatomy Toolbox (CAT12). Modulated normalized images were then smoothed with an 8 × 8 × 8 mm FWHM kernel using Statistical Parametric Mapping (SPM) software. Following CAT12 standard procedures, regional gray matter volume parcellation was performed in native space before normalization with the Neuromorphometrics Brain Atlas.

A whole-brain VBM analysis was conducted to investigate group differences (HC x MDD) in GM volume. This analysis controlled for effects of age, sex, and TIV. Voxel clusters reached significance if they survived statistical cluster correction (PFWE < 0.05). Given the significant results found with the parcellation data that revealed trust group differences in ROI GM volume, we further used small-volume correction at the peak voxel of an identified ROI (as described in the introduction) with a statistical threshold of PFWE < 0.05. The statistical SPM model generated in the above analysis was then used in a whole-brain VBM permutation test using the threshold-free cluster enhancement (TFCE) method implemented by the TFCE toolbox (http://www.neuro.uni-jena.de/tfce/). Results were considered significant if cluster survived a whole-brain correction threshold of PFWE < 0.05.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

The Tamagawa study was supported by Grants-in-aid #23223003 and #15H05730 from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science. The Hiroshima study was funded by a Grant-in-Aid for ‘Integrated Research on Depression, Dementia and Development Disorders (JP19dm0107093)’ carried out under the Strategic Research Program for Brain Sciences by the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (AMED), Brain/MINDS Beyond (JP19dm0307002) by AMED and a grant from JST Moonshot-9 JPMJMS2296. ASR Fermin was also supported by a grant from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (20K07723). This paper is in honor of the late Professor Toshio Yamagishi.

Author contributions

Tamagawa sample data: T.Y. organized the research project. Y.L. and Y.M. conducted the behavioral study. H.T., Y.L., and Y.M. conducted the MRI study. A.S.R.F. conducted the behavior and neuroimaging analyses with support from H.T., T.K. and Y.M. Hiroshima sample: Y.O. organized the research project. A.S.R.F., N.I., M.T. and S.Y. conducted the MRI study. A.S.R.F. conducted the behavior and neuroimaging analyses with support from N.I. and M.T. The manuscript was written by A.S.R.F. with input from all other authors.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-022-20443-w.

References

- 1.Ferrari AJ, et al. Global variation in the prevalence and incidence of major depressive disorder: A systematic review of the epidemiological literature. Psychol. Med. 2013;43:471. doi: 10.1017/S0033291712001511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Organization, W. H. Depression and Other Common Mental Disorders: Global Health Estimates. (2017).

- 3.James SL, et al. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 354 diseases and injuries for 195 countries and territories, 1990–2017: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet. 2018;392:1789–1858. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32279-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Charlson F, et al. New WHO prevalence estimates of mental disorders in conflict settings: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2019;394:240–248. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)30934-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Patel V, et al. Income inequality and depression: A systematic review and meta-analysis of the association and a scoping review of mechanisms. World Psychiatry. 2018;17:76–89. doi: 10.1002/wps.20492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stepanikova I, et al. Gender discrimination and depressive symptoms among child-bearing women: ELSPAC-CZ cohort study. EClinicalMedicine. 2020;20:100297. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Russell DW, Clavél FD, Cutrona CE, Abraham WT, Burzette RG. Neighborhood racial discrimination and the development of major depression. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2018;127:150. doi: 10.1037/abn0000336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.White ME, Satyen L. Cross-cultural differences in intimate partner violence and depression: A systematic review. Aggress. Violent Behav. 2015;24:120–130. doi: 10.1016/j.avb.2015.05.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wieclaw J, et al. Work related violence and threats and the risk of depression and stress disorders. J. Epidemiol. Commun. Health. 2006;60:771–775. doi: 10.1136/jech.2005.042986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Santavirta T, Santavirta N, Betancourt TS, Gilman SE. Long term mental health outcomes of Finnish children evacuated to Swedish families during the second world war and their non-evacuated siblings: Cohort study. BMJ. 2015;5:350. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g7753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Arata CM, Langhinrichsen-Rohling J, Bowers D, O’Farrill-Swails L. Single versus multi-type maltreatment: An examination of the long-term effects of child abuse. J. Aggress. Maltreatment Trauma. 2005;11:29–52. doi: 10.1300/J146v11n04_02. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brooks SK, et al. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: Rapid review of the evidence. Lancet. 2020;395:912–920. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30460-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wilkinson R, Pickett K. The Inner Level: How More Equal Societies Reduce Stress, Restore Sanity and Improve Everyone’s Well-Being. Penguin Books; 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weissman, M. M., Prusoff, B. A. & Klerman, G. L. Personality and the prediction of long-term outcome of depression. Am. J. Psychiatry (1978). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Beck, A. T., Epstein, N. & Harrison, R. Cognitions, attitudes and personality dimensions in depression. Br. J. Cogn. Psychother. (1983).

- 16.Hirschfeld RM, Klerman GL, Clayton PJ, Keller MB. Personality and depression: Empirical findings. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 1983;40:993–998. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1983.01790080075010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.von Zerssen D, Pössl J. The premorbid personality of patients with different subtypes of an affective illness: Statistical analysis of blind assignment of case history data to clinical diagnoses. J. Affect. Disord. 1990;18:39–50. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(90)90115-O. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Boyce P, Parker G, Barnett B, Cooney M, Smith F. Personality as a vulnerability factor to depression. Br. J. Psychiatry. 1991;159:106–114. doi: 10.1192/bjp.159.1.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kendler KS, Neale MC, Kessler RC, Heath AC, Eaves LJ. A longitudinal twin study of personality and major depression in women. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 1993;50:853–862. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1993.01820230023002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Depue RA. Neurobiological factors in personality and depression. Eur. J. Personal. 1995;9:413–439. doi: 10.1002/per.2410090509. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bienvenu OJ, et al. Normal personality traits and comorbidity among phobic, panic and major depressive disorders. Psychiatry Res. 2001;102:73–85. doi: 10.1016/S0165-1781(01)00228-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Clark LA, Vittengl J, Kraft D, Jarrett RB. Separate personality traits from states to predict depression. J. Pers. Disord. 2003;17:152–172. doi: 10.1521/pedi.17.2.152.23990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bienvenu OJ, et al. Anxiety and depressive disorders and the five-factor model of personality: A higher-and lower-order personality trait investigation in a community sample. Depress. Anxiety. 2004;20:92–97. doi: 10.1002/da.20026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Goodwin RD, Gotlib IH. Gender differences in depression: the role of personality factors. Psychiatry Res. 2004;126:135–142. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2003.12.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Klein DN, Kotov R, Bufferd SJ. Personality and depression: Explanatory models and review of the evidence. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2011;7:269–295. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032210-104540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tellenbach H. Melancholie: Problemgeschichte Endogenität Typologie Pathogenese Klinik. Springer; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Prince EJ, Siegel DJ, Carroll CP, Sher KJ, Bienvenu OJ. A longitudinal study of personality traits, anxiety, and depressive disorders in young adults. Anxiety Stress Coping. 2020;34:1–9. doi: 10.1080/10615806.2020.1845431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Helliwell JF, Putnam RD. The social context of well-being. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B. Biol. Sci. 2004;359:1435–1446. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2004.1522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fujiwara T, Kawachi I. A prospective study of individual-level social capital and major depression in the United States. J. Epidemiol. Commun. Health. 2008;62:627–633. doi: 10.1136/jech.2007.064261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Webber M, Huxley P, Harris T. Social capital and the course of depression: Six-month prospective cohort study. J. Affect. Disord. 2011;129:149–157. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2010.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tanaka T, Yamamoto T, Haruno M. Brain response patterns to economic inequity predict present and future depression indices. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2017;1:748–756. doi: 10.1038/s41562-017-0207-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Goldapple K, et al. Modulation of cortical-limbic pathways in major depression: Treatment-specific effects of cognitive behavior therapy. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 2004;61:34–41. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.1.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Drevets WC, et al. Subgenual prefrontal cortex abnormalities in mood disorders. Nature. 1997;386:824–827. doi: 10.1038/386824a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Price JL, Drevets WC. Neurocircuitry of mood disorders. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2010;35:192–216. doi: 10.1038/npp.2009.104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ho TC, et al. Subcortical shape alterations in major depressive disorder: Findings from the ENIGMA major depressive disorder working group. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2022;43:341–351. doi: 10.1002/hbm.24988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schmaal L, et al. Cortical abnormalities in adults and adolescents with major depression based on brain scans from 20 cohorts worldwide in the ENIGMA Major Depressive Disorder Working Group. Mol. Psychiatry. 2017;22:900–909. doi: 10.1038/mp.2016.60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ichikawa N, et al. Primary functional brain connections associated with melancholic major depressive disorder and modulation by antidepressants. Sci. Rep. 2020;10:1–12. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-60527-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tokuda T, et al. Identification of depression subtypes and relevant brain regions using a data-driven approach. Sci. Rep. 2018;8:1–13. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-32521-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Joseph C, Wang L, Wu R, Manning KJ, Steffens DC. Structural brain changes and neuroticism in late-life depression: A neural basis for depression subtypes. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2021;33:515–520. doi: 10.1017/S1041610221000284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bress JN, Foti D, Kotov R, Klein DN, Hajcak G. Blunted neural response to rewards prospectively predicts depression in adolescent girls. Psychophysiology. 2013;50:74–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.2012.01485.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cook K. Trust in Society. Russell Sage Foundation; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yamagishi T. Trust: The Evolutionary Game of Mind and Society. Springer; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hardin R, Offe C. Democracy and Trust. Cambridge University Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Olekalns M, Smith PL. Mutually dependent: Power, trust, affect and the use of deception in negotiation. J. Bus. Ethics. 2009;85:347–365. doi: 10.1007/s10551-008-9774-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Larson DW. Anatomy of Mistrust: US-Soviet Relations During the Cold War. Cornell University Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Linden M, Noack I. Suicidal and aggressive ideation associated with feelings of embitterment. Psychopathology. 2018;51:245–251. doi: 10.1159/000489176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.McQuaid RJ, McInnis OA, Stead JD, Matheson K, Anisman H. A paradoxical association of an oxytocin receptor gene polymorphism: Early-life adversity and vulnerability to depression. Front. Neurosci. 2013;7:128. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2013.00128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kim S-S, Chung Y, Perry MJ, Kawachi I, Subramanian SV. Association between interpersonal trust, reciprocity, and depression in South Korea: A prospective analysis. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e30602. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0030602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cao W, Li L, Zhou X, Zhou C. Social capital and depression: Evidence from urban elderly in China. Aging Ment. Health. 2015;19:418–429. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2014.948805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Myer L, Stein DJ, Grimsrud A, Seedat S, Williams DR. Social determinants of psychological distress in a nationally-representative sample of South African adults. Soc. Sci. Med. 2008;66:1828–1840. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.01.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lofors J, Sundquist K. Low-linking social capital as a predictor of mental disorders: A cohort study of 4.5 million Swedes. Soc. Sci. Med. 2007;64:21–34. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.08.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Forsman AK, Nyqvist F, Schierenbeck I, Gustafson Y, Wahlbeck K. Structural and cognitive social capital and depression among older adults in two Nordic regions. Aging Ment. Health. 2012;16:771–779. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2012.667784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Krueger F, et al. Oxytocin receptor genetic variation promotes human trust behavior. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2012;6:4. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2012.00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Nishina K, Takagishi H, Inoue-Murayama M, Takahashi H, Yamagishi T. Polymorphism of the oxytocin receptor gene modulates behavioral and attitudinal trust among men but not women. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0137089. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0137089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nishina K, et al. Association of the oxytocin receptor gene with attitudinal trust: Role of amygdala volume. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 2018;13:1091–1097. doi: 10.1093/scan/nsy075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kosfeld M, Heinrichs M, Zak PJ, Fischbacher U, Fehr E. Oxytocin increases trust in humans. Nature. 2005;435:673–676. doi: 10.1038/nature03701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Baumgartner T, Heinrichs M, Vonlanthen A, Fischbacher U, Fehr E. Oxytocin shapes the neural circuitry of trust and trust adaptation in humans. Neuron. 2008;58:639–650. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bos PA, Terburg D, Van Honk J. Testosterone decreases trust in socially naive humans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2010;107:9991–9995. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0911700107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Koscik TR, Tranel D. The human amygdala is necessary for developing and expressing normal interpersonal trust. Neuropsychologia. 2011;49:602–611. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2010.09.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Haas BW, Ishak A, Anderson IW, Filkowski MM. The tendency to trust is reflected in human brain structure. Neuroimage. 2015;107:175–181. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2014.11.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sadhu M, et al. Relationship between trust in neighbors and regional brain volumes in a population-based study. Psychiatry Res. Neuroimaging. 2019;286:11–17. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2019.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.King-Casas B, et al. Getting to know you: Reputation and trust in a two-person economic exchange. Science. 2005;308:78–83. doi: 10.1126/science.1108062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Baumgartner T, Fischbacher U, Feierabend A, Lutz K, Fehr E. The neural circuitry of a broken promise. Neuron. 2009;64:756–770. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Aimone JA, Houser D, Weber B. Neural signatures of betrayal aversion: An fMRI study of trust. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2014;281:20132127. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2013.2127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Keri S, Kiss I, Kelemen O. Sharing secrets: Oxytocin and trust in schizophrenia. Soc. Neurosci. 2009;4:287–293. doi: 10.1080/17470910802319710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hooker CI, et al. Can I trust you? Negative affective priming influences social judgments in schizophrenia. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2011;120:98. doi: 10.1037/a0020630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Yamagishi T, Yamagishi M. Trust and commitment in the United States and Japan. Motiv. Emot. 1994;18:129–166. doi: 10.1007/BF02249397. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Yamagishi T, Cook KS, Watabe M. Uncertainty, trust, and commitment formation in the United States and Japan. Am. J. Sociol. 1998;104:AJSv104p165–194. doi: 10.1086/210005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hayashi N, Ostrom E, Walker J, Yamagishi T. Reciprocity, trust, and the sense of control: A cross-societal study. Ration. Soc. 1999;11:27–46. doi: 10.1177/104346399011001002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Cook KS, et al. Trust building via risk taking: A cross-societal experiment. Soc. Psychol. Q. 2005;68:121–142. doi: 10.1177/019027250506800202. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Yamagishi T, Kanazawa S, Mashima R, Terai S. Separating trust from cooperation in a dynamic relationship: Prisoner’s dilemma with variable dependence. Ration. Soc. 2005;17:275–308. doi: 10.1177/1043463105055463. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kiyonari T, Yamagishi T, Cook KS, Cheshire C. Does trust beget trustworthiness? Trust and trustworthiness in two games and two cultures: A research note. Soc. Psychol. Q. 2006;69:270–283. doi: 10.1177/019027250606900304. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kuwabara K, et al. Culture, identity, and structure in social exchange: A web-based trust experiment in the United States and Japan. Soc. Psychol. Q. 2007;70:461–479. doi: 10.1177/019027250707000412. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Foddy M, Platow MJ, Yamagishi T. Group-based trust in strangers: The role of stereotypes and expectations. Psychol. Sci. 2009;20:419–422. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2009.02312.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Platow MJ, Foddy M, Yamagishi T, Lim LI, Chow A. Two experimental tests of trust in in-group strangers: The moderating role of common knowledge of group membership. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 2012;42:30–35. doi: 10.1002/ejsp.852. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Yamagishi T, et al. Two-component model of general trust: Predicting behavioral trust from attitudinal trust. Soc. Cogn. 2015;33:436–458. doi: 10.1521/soco.2015.33.5.436. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Skundberg-Kletthagen H, Wangensteen S, Hall-Lord ML, Hedelin B. Relatives of patients with depression: Experiences of everyday life. Scand. J. Caring Sci. 2014;28:564–571. doi: 10.1111/scs.12082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Chambel MJ, Oliveira-Cruz F. Breach of psychological contract and the development of burnout and engagement: A longitudinal study among soldiers on a peacekeeping mission. Mil. Psychol. 2010;22:110–127. doi: 10.1080/08995601003638934. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Rosenquist JN, Fowler JH, Christakis NA. Social network determinants of depression. Mol. Psychiatry. 2011;16:273–281. doi: 10.1038/mp.2010.13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Yoon S, Kleinman M, Mertz J, Brannick M. Is social network site usage related to depression? A meta-analysis of Facebook–depression relations. J. Affect. Disord. 2019;248:65–72. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2019.01.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Stavrakaki C, Vargo B. The relationship of anxiety and depression: A review of the literature. Br. J. Psychiatry J. Ment. Sci. 1986;149:7–16. doi: 10.1192/bjp.149.1.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Lovibond PF, Lovibond SH. The structure of negative emotional states: Comparison of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS) with the Beck Depression and Anxiety Inventories. Behav. Res. Ther. 1995;33:335–343. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(94)00075-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Beck AT, Epstein N, Brown G, Steer RA. An inventory for measuring clinical anxiety: Psychometric properties. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 1988;56:893–897. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.56.6.893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Beck AT, Steer RA, Ball R, Ranieri WF. Comparison of Beck Depression Inventories-IA and-II in psychiatric outpatients. J. Pers. Assess. 1996;67:588–597. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa6703_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Beck AT, Steer RA. Internal consistencies of the original and revised Beck Depression Inventory. J. Clin. Psychol. 1984;40:1365–1367. doi: 10.1002/1097-4679(198411)40:6<1365::AID-JCLP2270400615>3.0.CO;2-D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Gradin VB, et al. Abnormal brain responses to social fairness in depression: An fMRI study using the ultimatum game. Psychol. Med. 2015;45:1241–1251. doi: 10.1017/S0033291714002347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Sanfey AG, Rilling JK, Aronson JA, Nystrom LE, Cohen JD. The neural basis of economic decision-making in the ultimatum game. Science. 2003;300:1755–1758. doi: 10.1126/science.1082976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Rilling JK, et al. The neural correlates of the affective response to unreciprocated cooperation. Neuropsychologia. 2008;46:1256–1266. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2007.11.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Spitzer M, Fischbacher U, Herrnberger B, Grön G, Fehr E. The neural signature of social norm compliance. Neuron. 2007;56:185–196. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Mars RB, et al. On the relationship between the “default mode network” and the “social brain”. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2012;6:189. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2012.00189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Sallet J, et al. Social network size affects neural circuits in macaques. Science. 2011;334:697–700. doi: 10.1126/science.1210027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Noonan MP, Mars RB, Sallet J, Dunbar RIM, Fellows LK. The structural and functional brain networks that support human social networks. Behav. Brain Res. 2018;355:12–23. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2018.02.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Fermin AS, et al. Representation of economic preferences in the structure and function of the amygdala and prefrontal cortex. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:20982. doi: 10.1038/srep20982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Blakemore S-J. The social brain in adolescence. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2008;9:267–277. doi: 10.1038/nrn2353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Yamagishi T, et al. Cortical thickness of the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex predicts strategic choices in economic games. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2016;113:5582–5587. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1523940113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Morishima Y, Schunk D, Bruhin A, Ruff CC, Fehr E. Linking brain structure and activation in temporoparietal junction to explain the neurobiology of human altruism. Neuron. 2012;75:73–79. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Ruff CC, Ugazio G, Fehr E. Changing social norm compliance with noninvasive brain stimulation. Science. 2013;342:482–484. doi: 10.1126/science.1241399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Grieve SM, Korgaonkar MS, Koslow SH, Gordon E, Williams LM. Widespread reductions in gray matter volume in depression. NeuroImage Clin. 2013;3:332–339. doi: 10.1016/j.nicl.2013.08.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Frodl TS, et al. Depression-related variation in brain morphology over 3 years: effects of stress? Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 2008;65:1156–1165. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.65.10.1156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.van Tol M-J, et al. Regional brain volume in depression and anxiety disorders. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 2010;67:1002–1011. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Kupferberg A, et al. Testing the social competition hypothesis of depression using a simple economic game. BJPsych Open. 2016;2:163–169. doi: 10.1192/bjpo.bp.115.001362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Scheele D, Mihov Y, Schwederski O, Maier W, Hurlemann R. A negative emotional and economic judgment bias in major depression. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2013;263:675–683. doi: 10.1007/s00406-013-0392-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Radke S, Schäfer IC, Müller BW, de Bruijn ER. Do different fairness contexts and facial emotions motivate ‘irrational’social decision-making in major depression? An exploratory patient study. Psychiatry Res. 2013;210:438–443. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2013.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Ong DC, Zaki J, Gruber J. Increased cooperative behavior across remitted bipolar I disorder and major depression: Insights utilizing a behavioral economic trust game. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2017;126:1. doi: 10.1037/abn0000239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Savitz J, Drevets WC. Bipolar and major depressive disorder: Neuroimaging the developmental-degenerative divide. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2009;33:699–771. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2009.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Lee AL, Ogle WO, Sapolsky RM. Stress and depression: Possible links to neuron death in the hippocampus. Bipolar Disord. 2002;4:117–128. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-5618.2002.01144.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Esch T, Stefano GB, Fricchione GL, Benson H. The role of stress in neurodegenerative diseases and mental disorders. Neuroendocrinol. Lett. 2002;23:199–208. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Litvan I, Cummings JL, Mega M. Neuropsychiatric features of corticobasal degeneration. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 1998;65:717–721. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.65.5.717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Moylan S, Maes M, Wray NR, Berk M. The neuroprogressive nature of major depressive disorder: Pathways to disease evolution and resistance, and therapeutic implications. Mol. Psychiatry. 2013;18:595–606. doi: 10.1038/mp.2012.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Réus GZ, et al. Neurochemical correlation between major depressive disorder and neurodegenerative diseases. Life Sci. 2016;158:121–129. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2016.06.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Ruiz NAL, del Ángel DS, Olguín HJ, Silva ML. Neuroprogression: The hidden mechanism of depression. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2018;14:2837–2845. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S177973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Stein JL, et al. Identification of common variants associated with human hippocampal and intracranial volumes. Nat. Genet. 2012;44:552–561. doi: 10.1038/ng.2250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Pol HEH, et al. Genetic contributions to human brain morphology and intelligence. J. Neurosci. 2006;26:10235–10242. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1312-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Thompson PM, et al. Genetic influences on brain structure. Nat. Neurosci. 2001;4:1253–1258. doi: 10.1038/nn758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Carballedo A, et al. Early life adversity is associated with brain changes in subjects at family risk for depression. World J. Biol. Psychiatry. 2012;13:569–578. doi: 10.3109/15622975.2012.661079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Opel N, et al. Differing brain structural correlates of familial and environmental risk for major depressive disorder revealed by a combined VBM/pattern recognition approach. Psychol. Med. 2016;46:277–290. doi: 10.1017/S0033291715001683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Consortium B et al. Analysis of shared heritability in common disorders of the brain. Science. 2018;360:eaap8757. doi: 10.1126/science.aap8757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Howard DM, et al. Genome-wide meta-analysis of depression identifies 102 independent variants and highlights the importance of the prefrontal brain regions. Nat. Neurosci. 2019;22:343–352. doi: 10.1038/s41593-018-0326-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Swartz JR, Hariri AR, Williamson DE. An epigenetic mechanism links socioeconomic status to changes in depression-related brain function in high-risk adolescents. Mol. Psychiatry. 2017;22:209–214. doi: 10.1038/mp.2016.82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Sturgis P, Read S, Allum N. Does intelligence foster generalized trust? An empirical test using the UK birth cohort studies. Intelligence. 2010;38:45–54. doi: 10.1016/j.intell.2009.11.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Xiang T, Ray D, Lohrenz T, Dayan P, Montague PR. Computational phenotyping of two-person interactions reveals differential neural response to depth-of-thought. PLoS Comput Biol. 2012;8:e1002841. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1002841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Evans AM, Athenstaedt U, Krueger JI. The development of trust and altruism during childhood. J. Econ. Psychol. 2013;36:82–95. doi: 10.1016/j.joep.2013.02.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Boyle, R. & Bonacich, P. The development of trust and mistrust in mixed-motive games. Sociometry 123–139 (1970).

- 124.Buzzelli, C. A. The development of trust in children’s relations with peers. Child Study J. (1988).

- 125.Bernath MS, Feshbach ND. Children’s trust: Theory, assessment, development, and research directions. Appl. Prev. Psychol. 1995;4:1–19. doi: 10.1016/S0962-1849(05)80048-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Stolle D. ‘Getting to Trust’: An Analysis of the Importance of Institutions, Families, Personal Experiences and Group Membership. Routledge; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 127.Lemmers-Jansen IL, Krabbendam L, Veltman DJ, Fett A-KJ. Boys vs. girls: Gender differences in the neural development of trust and reciprocity depend on social context. Dev. Cogn. Neurosci. 2017;25:235–245. doi: 10.1016/j.dcn.2017.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Lewicki RJ, Tomlinson EC, Gillespie N. Models of interpersonal trust development: Theoretical approaches, empirical evidence, and future directions. J. Manag. 2006;32:991–1022. [Google Scholar]

- 129.Sutter, M. & Kocher, M. G. Age and the development of trust and reciprocity. SSRN 480184 (2003).

- 130.Cameron CD, Reber J, Spring VL, Tranel D. Damage to the ventromedial prefrontal cortex is associated with impairments in both spontaneous and deliberative moral judgments. Neuropsychologia. 2018;111:261–268. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2018.01.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Anderson SW, Bechara A, Damasio H, Tranel D, Damasio AR. Impairment of social and moral behavior related to early damage in human prefrontal cortex. Nat. Neurosci. 1999;2:1032–1037. doi: 10.1038/14833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Gläscher J, et al. Lesion mapping of cognitive control and value-based decision making in the prefrontal cortex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2012;109:14681–14686. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1206608109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Kanske P, Böckler A, Trautwein F-M, Singer T. Dissecting the social brain: Introducing the EmpaToM to reveal distinct neural networks and brain–behavior relations for empathy and theory of mind. Neuroimage. 2015;122:6–19. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2015.07.082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Soutschek A, Ruff CC, Strombach T, Kalenscher T, Tobler PN. Brain stimulation reveals crucial role of overcoming self-centeredness in self-control. Sci. Adv. 2016;2:e1600992. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.1600992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Pujol J, et al. Posterior cingulate activation during moral dilemma in adolescents. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2008;29:910–921. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Johnson MK, et al. Dissociating medial frontal and posterior cingulate activity during self-reflection. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 2006;1:56–64. doi: 10.1093/scan/nsl004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Pearson JM, Heilbronner SR, Barack DL, Hayden BY, Platt ML. Posterior cingulate cortex: adapting behavior to a changing world. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2011;15:143–151. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2011.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Bruneau EG, Saxe R. Attitudes towards the outgroup are predicted by activity in the precuneus in Arabs and Israelis. Neuroimage. 2010;52:1704–1711. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.05.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Winston JS, Strange BA, O’Doherty J, Dolan RJ. Automatic and intentional brain responses during evaluation of trustworthiness of faces. Nat. Neurosci. 2002;5:277–283. doi: 10.1038/nn816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Engelmann JB, Meyer F, Ruff CC, Fehr E. The neural circuitry of affect-induced distortions of trust. Sci. Adv. 2019;5:eaau3413. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aau3413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Chang LJ, Smith A, Dufwenberg M, Sanfey AG. Triangulating the neural, psychological, and economic bases of guilt aversion. Neuron. 2011;70:560–572. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.02.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Valk SL, et al. Structural plasticity of the social brain: Differential change after socio-affective and cognitive mental training. Sci. Adv. 2017;3:e1700489. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.1700489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Gotlib IH, Krasnoperova E, Yue DN, Joormann J. Attentional biases for negative interpersonal stimuli in clinical depression. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2004;113:127. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.113.1.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Nolen-Hoeksema S, Wisco BE, Lyubomirsky S. Rethinking rumination. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2008;3:400–424. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-6924.2008.00088.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Grimm S, et al. Imbalance between left and right dorsolateral prefrontal cortex in major depression is linked to negative emotional judgment: An fMRI study in severe major depressive disorder. Biol. Psychiatry. 2008;63:369–376. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.05.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Dam A, Roelofs J, Muris P. Correlates of co-rumination in non-clinical adolescents. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2014;23:521–526. doi: 10.1007/s10826-012-9711-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Ruijten T, Roelofs J, Rood L. The mediating role of rumination in the relation between quality of attachment relations and depressive symptoms in non-clinical adolescents. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2011;20:452–459. doi: 10.1007/s10826-010-9412-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Cacioppo JT, Cacioppo S. The growing problem of loneliness. Lancet. 2018;391:426. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30142-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Gardiner C, Geldenhuys G, Gott M. Interventions to reduce social isolation and loneliness among older people: an integrative review. Health Soc. Care Commun. 2018;26:147–157. doi: 10.1111/hsc.12367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Evans AM, Revelle W. Survey and behavioral measurements of interpersonal trust. J. Res. Personal. 2008;42:1585–1593. doi: 10.1016/j.jrp.2008.07.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]