Abstract

Introduction

The COVID‐19 pandemic has disrupted the lives of US students both at home and at school. Little is known regarding how adolescents perceive COVID‐19 has impacted (both positively and negatively) their academic and social lives and how protective factors, such as hope, may assist with resilience. Importantly, not all pandemic experiences are necessarily negative, and positive perceptions, as well as potential protective factors, are key to understanding the pandemic's role in students' lives.

Method

Utilizing quantitative and qualitative approaches, the present study descriptively examined 726 6th through 12th grade (51% female, 53% White) students' perceptions of how COVID‐19 related to educational and life disruptions, and positive aspects of their lives, within the United States. Analyses additionally explored the role of pre‐pandemic hope in improving feelings of school connectedness during the pandemic.

Results

Results showed that most students felt that switching to online learning had been difficult and their education had suffered at least moderately, with a sizeable proportion of students feeling less academic motivation compared with last year. When asked to share qualitative answers regarding perceived challenges and positive aspects of life, themes were consistent with quantitative perceptions. Students' pre‐pandemic hope positively predicted students' feelings of school connectedness.

Conclusions

Findings paint a complex picture of youth's COVID‐19 experiences and have implications for proactive ways to support students as COVID‐19 continues to affect daily life and educational structures and practices.

Keywords: adolescence, COVID‐19, hope, school connectedness

1. INTRODUCTION

Although researchers have noted a marked increase in adolescents' mental health issues, little is known regarding how adolescents feel their lives have been specifically impacted by COVID‐19, how protective factors such as hope may assist with resilience and if there are any positive experiences that may be a by‐product of the pandemic (Dvorsky et al., 2020; Jones et al., 2021). The COVID‐19 pandemic has altered the lives of US students both at home and school, particularly as students have had to attend school virtually, potentially disrupting feelings of school connectedness. Outside of school, students may face increased concern and stress regarding COVID‐19's potential impact on health, friendships and the future (Magson et al., 2021). Importantly, not all pandemic experiences may have been perceived as negative, and perceptions may have differed across school level given that students are at different stages of educational and personal development in middle versus high school. Therefore, the goal of the present study was to examine middle school (MS) and high school (HS) students' perceptions, both positive and negative, surrounding the impact of COVID‐19 on their academic and personal lives and to understand if hope was a potential protective factor in promoting students' school connectedness during this historic event.

Given that the existing literature on adolescents during the COVID‐19 pandemic has primarily focused on negative experience and situations, such as the social, academic and recreational repercussions of social isolation, increased stress and detrimental mental health implications (de Figueiredo et al., 2021; Ravens‐Sieberer et al., 2021; Samji et al., 2021), the present study extends this literature by highlighting the importance of positive experiences and skills both regarding life in general and school. Specifically, one such positive skill is hope, a cognitive, motivational construct, which may serve as a protective factor in supporting feelings of connection with school (Marques et al., 2017); this is important as less school connectedness may be tied to changes in the school format and negatively affect academic motivation, which would have implications for student outcomes.

2. COVID‐19 AND EDUCATIONAL AND LIFE DISRUPTIONS FOR ADOLESCENTS

Developmentally, adolescence is characterized by identity development, increased autonomy and educational preparation that help determine life course trajectories (Kroger, 2004). This period of developmental growth makes adolescents especially vulnerable to the stress of a global pandemic (Tottenham & Galván, 2016; Zhou, 2020). The repercussions of the pandemic have been pervasive, with disruptions occurring across contexts including homes and schools. Yet, little is known regarding how MS and HS adolescents describe and rate their pandemic experiences. Exploring individual perceptions is key to understanding how adolescents make meaning of their own experiences and perceptions (Grusec & Goodnow, 1994; Witherspoon & Hughes, 2014), particularly when those perceptions surround disruption in education and their personal life.

2.1. Educational disruptions

Nearly 93% of households with school‐age children reported some form of distance learning during the COVID‐19 pandemic (Mcelrath, 2020). School closures and online learning requirements necessitated significant changes for students, with face‐to‐face interaction with peers and teachers suddenly changing to online‐only interfacing. The sudden, pervasive disruptions may have yet‐to‐be‐known implications for students' outcomes (Golberstein et al., 2020). However, as recent studies have shown, it is likely that adolescents' motivation to participate and engage were impacted as schools were shuttered (Klootwijk et al., 2021; Maiya et al., 2021). Although researchers and educational leaders have posited negative educational impacts, and the circumstances certainly warrant conjecture, few studies have asked students how they feel their motivation has changed and whether their education has suffered, despite students' reports of decreased academic motivation and school connection (Klootwijk et al., 2021; Maiya et al., 2021).

2.2. Life disruptions

In addition to educational disruption, daily life also changed drastically for many students during the pandemic, with social gatherings, extracurricular activities, and daily happenings being severely limited. Additionally, there were likely drastic changes within the home environment, with students remaining at home for schooling, caregivers/parents working remotely and potentially increased time with the entire household unit being isolated at home, all of which may have been either a positive or negative experience for the adolescent depending on family dynamics. Persistent media coverage of the health risks of COVID‐19 may have also led to concern over personal and family health as well as society's future as a whole. Researchers have qualitatively explored adolescents' COVID‐19 experiences, and themes showed that challenges covered a wide spectrum, but adolescents overwhelmingly reported negative outcomes including loneliness, mental health problems and academic struggle (Scott et al., 2021). To build on this knowledge, the present study aims to descriptively explore how adolescents described concern over their social lives, personal and family health and society 1 year into the pandemic.

Further, although there has been emphasis on how the pandemic has negatively affected students, it is also important to understand if there were factors that supported students during this time (Dvorsky et al., 2020). For example, quantitative research conducted among adolescents in Hong Kong showed that even when faced with school closures and pandemic‐related concerns, a sizeable proportion of students reported stronger relationships with their peers and parents (Zhu et al., 2021). New hobbies may have also been taken on during the pandemic. These supportive aspects of adolescents' lives may have served as protective factors that encouraged them to remain positive during this difficult time. Indeed, adolescents who reported having strong support from friends and family during the pandemic showed less academic concern (Christ & Gray, 2022) and more academic motivation (Klootwijk et al., 2021) than those who reported low levels of support. The aforementioned studies only focused on survey measures that asked students to quantitatively rate positive aspects of their lives and social support, with an emphasis on relationships. To fully understand the implications of these positive experience during the pandemic, it is important to allow adolescents to share their own experiences qualitatively, which may provide more comprehensive information on different ways that adolescents viewed aspects of their lives as positive, beyond interactions with others. In addition to these pandemic‐induced experiences, there may have been protective factors in students' pre‐pandemic lives that helped to support them connect with school; one such protective factor may have been hope.

3. HOPE AS A PROTECTIVE FACTOR

Hope is a malleable, cognitive‐motivational construct that encompasses individuals' goal pursuit (Fraser et al., 2022). Hope theory posits that hopeful individuals are able to demonstrate behaviours and have beliefs that are directly related to and align with goal pursuit (Snyder, 2002). Specifically, high‐hope individuals are able to identify their future goals, determine how to reach those goals and reroute when necessary(i.e. pathways thinking) and feel confident in their pursuit of goals (i.e. agency thinking). Furthermore, hope is an additive and iterative process in that students set goals, work towards and reach those goals, which, in turn, helps them feel motivated to set and pursue new goals. Within an academic setting, students with high hope can identify academic goals, recognize the steps necessary to achieve those goals and/or tenable alternatives and feel confident in their approach to reaching those goals; successful completion of these steps not only bolsters students' hope but also their desire to confidently continue educational pursuits (Marques et al., 2017). In terms of academic outcomes, extant research has shown that hope positively predicts achievement (Marques et al., 2017), academic effort (Levi et al., 2014) and students' connection to academics (Snyder, 2002; Van Ryzin, 2011) and that a positive association exists between hope and school connectedness (Dixson & Scalcucci, 2021; Liu et al., 2020; You et al., 2008). Further, hope serves as a protective factor during tumultuous times. For example, researchers have shown that high hope reduced symptoms related to post‐traumatic stress disorder among hurricane survivors (Glass et al., 2009) and children who experienced rocket attacks (Kasler et al., 2008).

In terms of the COVID‐19 pandemic, hope has been shown to operate as a protective factor in numerous ways, particularly in improving coping approaches and mental health. Among American adults surveyed during the pandemic, high hope was associated with decreased stress surrounding COVID‐19 and positively associated with well‐being and emotional control, a potential mechanism for coping in stressful situations (Gallagher et al., 2021). Hope was also shown to support adults' abilities to demonstrate resilience when faced with difficult situations and was associated with better overall psychological health (Yıldırım & Arslan, 2020). The two aforementioned studies highlight how hope may operate as a protective factor for individuals' well‐being. Academically, among college students, hope positively predicted students' ability to overcome trauma/distress associated with the pandemic (Hu et al., 2021), which highlights how being able to think about future goals and pathways to success can serve as a protective factor against pandemic distress. Importantly, to our knowledge, researchers have yet to examine how adolescents' pre‐pandemic hope may have acted as a supportive factor for youth outcomes.

When considering the role of hope during the pandemic for adolescents, high‐hope students may be more able to identify ways to remain engaged in online settings or modified learning structures and feel efficacious in pursing their planned routes, thus supporting students' feelings of connection to school. Despite theoretical support, to our knowledge, researchers have not yet examined the role of hope for middle and high school students' outcomes during the pandemic. As society begins to navigate new and changing mitigation strategies and approaches, and schools return to in‐person learning, it is critical that we understand how strengths‐based skills such as hope may serve as protective factors.

4. THE PRESENT STUDY

In the midst of a global pandemic, more information is needed regarding students' own perceptions of how COVID‐19 impacted their lives. Furthermore, students' pre‐pandemic hope may be an important protective factor in supporting students' school connectedness. The present study addressed two main research questions. First, how did MS and HS students quantitatively rate their feelings about educational and life disruptions as related to COVID‐19, and what did students qualitatively report as the largest perceived challenges and positive aspects of their lives during Spring 2021? Although descriptive in nature, we hypothesized that students would report that COVID had a large impact on their academic experience and life more generally. Second, did 2020 hope (pre‐pandemic) serve as a protective factor for students' 2021 school connectedness? We hypothesized that 2020 hope would positively predict 2021 school connectedness.

5. METHODS

5.1. Participants and procedure

In 2021, all students (M age = 14.52 SD age = 1.94) in 6th through 12th grade were recruited from two schools (MS n = 394; HS n = 332; total N = 726; 59% response rate) that drew from rural and suburban areas in the Southwestern United States; 51% of students were female, 13% qualified for special education services, and 61% qualified for free/reduced lunch. In terms of race/ethnicity, 53% identified as White, 40% as Hispanic/Latinx, 4% as Black, and 3% as other. Within this district, during the 2020/2021 school year, the schools were closed (remote learning) from August 2020 through mid‐October 2020. Learning shifted to in‐person classes from mid‐October 2020 through December 2020. Then, schools were closed again (remote learning) from January 2021 through late February 2021. At the time of data collection (mid‐February 2021), the state in which the schools were located had a daily COVID‐19 infection rate of 246 new cases per 100 000, and a COVID‐19 death rate of 12.2 per 100 000 (White House COVID‐19 Team JCC, 2021).

District data collection targeted enrolled students, who completed the online survey during the school day. Surveys were conducted in February 2020 (prior to the COVID‐19 pandemic, students in‐person learning) and February 2021(during pandemic, remote learning). Teachers provided the survey link and oriented students to the survey, and students were informed they could skip questions or choose not to participate. All students in 5th to 12th grades were invited to complete the survey each year and entered an anonymous (to the researchers) identifier that allowed data to be matched from year to year. For the purpose of this study, we utilized data from MS and HS students who were in 6th through 12th grade during the 2021 data collection (5th through 11th in 2020). This approach allowed for the use of 2020 survey data as a predictor of 2021 survey data. A university institutional review board approved the study.

Participants were included in the present study if they had data in 2021. Educational disruption due to COVID‐19, life concerns due to COVID‐19, perceived challenges and positive aspects of life and school connectedness were collected in February 2021; hope was the only 2020 construct included in the study. Demographic data for 2021 were available for all students within the district in the focal grades (n = 1241). Students in the analytic sample differed from those who did not complete the survey in terms of gender (χ 2(1) = 13.19, P < .01) and special education designation (χ 2(1) = 12.41, P < .01), but not in terms of race/ethnicity (χ 2(3) = 2.64, P = .62) or free/reduced lunch qualification (χ 2(1) = 1.17, P = .28).

Of the analytic sample (n = 726), 347 (48%) participants were missing 2020 data. Of those 347 students, 130 (37%) were new to the district in 2021 (MS n = 75; HS n = 55), which would account for their missingness on 2020 data. When comparing all students missing 2020 data (n = 347) with those without missing data, there was no significant difference between missing data groups for MS students' 2021 school connectedness. For HS students, a significant difference emerged, with those who were missing 2020 hope data reporting lower 2021 school connectedness (M = 2.37, SD = 0.62) than those with 2020 hope data (M = 2.62, SD = 0.67), F(1, 329) = 11.47, P < .01. We ran additional analyses to examine those who had missing data but were enrolled at the district in 2020 (n = 217), compared with those who had 2020 data. Similar to the other missing data analyses, there were no significant differences between missing‐data groups for MS students. For HS students, the difference on school connectedness became less significant (marginal) when comparing students who had the opportunity to take the 2020 survey but did not (M = 2.43, SD = .61) with those who had completed the 2020 survey (M = 2.63, SD = 0.67), F(1, 274) = 3.92, P = .05. Lastly, we examined if the two groups without 2020 data (those who were new to the district and those who were not) differed on school connectedness. For both MS and HS students, there were no significant differences in mean‐level school connectedness between the two groups, F(1, 229) = 2.32, P = .13 and F(1, 113) = 1.40, P = .24, respectively.

5.2. MEASURES

5.2.1. Educational disruptions due to COVID‐19

Students completed three items about how COVID‐19 had caused disruption to their education (Magson et al., 2021). Two items focused on changes due to COVID‐19 (i.e. ‘How difficult has it been to switch to online learning?’ and ‘Do you think your education is suffering due to disruption from COVID‐19?’) and were rated on a 5‐point Likert‐type scale (1 = not at all to 5 = extremely). One item that focused on motivation (i.e. ‘Compared to how motivated you were last school year to do school work, how motivated do you feel NOW to do your school work?’) was answered on a 3‐point scale (1 = much less motivated, 2 = about the same, 3 = much more motivated). These items were chosen because they have been used in previous work among adolescents during COVID‐19 (Magson et al., 2021).

5.2.2. Life concerns due to COVID‐19

Students reported their level of COVID‐19 related stress (1 = not at all stressful to 5 = very stressful) on five questions that addressed concerns about not seeing friends, not attending social events, contracting COVID‐19 themselves, friends/family contracting COVID‐19 and thinking about the future of our society. Researchers have used this scale in previous work focusing on COVID‐19 and demonstrated high reliability (Cronbach's alpha = 0.91) (Magson et al., 2021). The present study utilized item‐level data, and we chose this approach and measure to allow for a more nuanced understanding of students' feelings across specific areas.

5.2.3. Perceived challenges and positive aspects of life

Utilizing open‐ended response questions, students were asked, ‘What is the biggest challenge in your life right now?’ and ‘What is the best thing in your life right now?’ These items were chosen to provide students with the opportunity to express their own feelings about perceived challenges and positive aspects of their lives.

5.2.4. Hope

Students reported their feelings of hope (6‐point Likert‐type scale, 1 = none of the time to 6 = all of the time) using the 6‐item Children's Hope Scale (Snyder et al., 1997). We chose this scale given its alignment with hope theory. Additionally, this scale has had good reliability in previous work (Valle et al., 2004) and the present study (Cronbach's alphas = 0.87 and 0.89, MS and HS, respectively). A higher mean composite indicated more hope.

5.2.5. School connectedness

Students reported their feelings of school connectedness (Mancini et al., 2003) on three items (e.g. ‘I feel like I matter in my school’) using a 4‐point Likert‐type scale (1 = strongly disagree to 4 = strongly agree). We chose this scale because it captures student perceptions of their belongingness and importance at school. This scale showed good reliability in the present study (Cronbach's alpha = 0.70 and 0.72, MS and HS, respectively) and previous work (Meléndez Guevara et al., 2021). A higher mean composite indicated more school connectedness.

5.2.6. Gender

Given that previous research has shown inconsistent results regarding gender differences on individuals' responses in the face of serious national/international events (i.e. natural disasters, other pandemics; Kronenberg et al., 2010; Sprang & Silman, 2013), we included gender as a covariate in study analyses. Student gender (0 = female, 1 = male) was obtained via school records and included as a covariate in study analyses.

5.3. Analytic plan

We first examined descriptive statistics and Pearson correlations for MS and HS students' feelings about educational and life disruptions as related to COVID‐19. We additionally examined school‐level differences on motivation using a chi‐square test, conducted analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) for the remaining two educational variables and ran a multivariate analysis of covariance (MANCOVA) for the five life questions, controlling for gender for the ANCOVAs and MANCOVA. We next coded each open‐ended response to find the common themes regarding students' perceived challenges and positive aspects of life; overall, most students provided one to two‐word responses for the open‐ended questions, allowing for the responses to be easily grouped by theme. The first author coded the themes, and any that were more complex were coded for multiple themes. All items that were coded for multiple themes were then reviewed by the second author. This approach allowed us to examine if students' open‐ended responses confirmed or expanded upon the responses for the survey measures.

Lastly, we conducted a structural equation model (SEM) to examine if 2020 hope predicted 2021 school connectedness. Model fit was examined; meeting at least three of the following criteria were used to determine acceptable model fit given: χ2 P‐value > .05, the comparative fit index (CFI) ≥ .95, the standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) ≤ .08 and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) ≤ .06 (Hu & Bentler, 1999). Descriptive statistics, correlations, ANCOVAs and MANCOVA were conducted in SPSS 25. The SEM models were conducted in Mplus 8.

6. RESULTS

Descriptive statistics are presented for all study variables by school level in Table 1, and correlations among study variables are presented in Table 2. Hope and school connectedness were positively, significantly correlated for both MS and HS students. As expected, across school level, all education concerns related to COVID‐19 were significantly positively correlated, as were all correlations among the life distress questions related to COVID‐19.

TABLE 1.

Descriptive statistics for all study variables

| Minimum | Maximum | Mean | SD | Group comparison statistics | Comparison statistics 95% CI for mean | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hope (2020) | 1.50/1.00 | 6.00/6.00 | 4.28/4.27 | 1.12/1.05 | ||

| Agency subscale | 1.33/1.00 | 6.00/6.00 | 4.28/4.35 | 1.26/1.16 | ||

| Pathways subscale | 1.33/1.00 | 6.00/6.00 | 4.28/4.18 | 1.18/1.10 | ||

| School Connectedness (2021) | 1.00/1.00 | 4.00/4.00 | 2.62/2.53 | 0.71/0.66 | ||

| Education concerns related to COVID‐19 (2021) | ANCOVA statistics | |||||

| Difficulty switching to online learning | 1.00/1.00 | 5.00/5.00 | 3.31/3.23 | 1.47/1.35 | F(1, 722) = .61, P = .43 | [3.17, 3.45]/[3.08, 3.38] |

| Education is suffering due to disruption | 1.00/1.00 | 5.00/5.00 | 3.31/3.31 | 1.53/1.50 | F(1, 722) = .01, P = .97 a | [3.16, 3.46]/[3.14, 3.47] |

| Current school motivation compared with last year | 1.00/1.00 | 3.00/3.00 | 1.79/1.74 | 0.72/0.76 | ‐ | |

| Life distress related to COVID‐19 (2021) | MANCOVA statistics F(5, 703) = 4.09, P < .01, Wilks' Λ = .97 | |||||

| Not seeing friends | 1.00/1.00 | 5.00/5.00 | 2.98/2.61 | 1.54/1.37 | F(1, 707) = 11.18, P < .01 a | [2.82, 3.11]/[2.44, 2.76] |

| Not attending social events | 1.00/1.00 | 5.00/5.00 | 2.54/2.40 | 1.53/1.34 | F (1, 707) = 1.91, P = .17 | [2.40, 2.69]/[2.23, 2.55] |

| Catching COVID‐19 | 1.00/1.00 | 5.00/5.00 | 2.82/2.44 | 1.65/1.48 | F(1, 707) = 10.01, P < .01 | [2.66, 2.98]/[2.27, 2.62] |

| Friends/family catching COVID‐19 | 1.00/1.00 | 5.00/5.00 | 3.48/3.12 | 1.52/1.47 | F (1, 707) = 10.29, P < .01 a | [3.33, 3.63]/[2.97, 3.29] |

| Thinking about future of society | 1.00/1.00 | 5.00/5.00 | 3.13/3.00 | 1.48/1.40 | F(1, 707) = 1.78, P = .18 a | [2.99, 3.28]/[2.83, 3.14] |

Note: Middle school presented first followed by high school in bold.

Abbreviation: CI, confidence interval.

Indicates a model where the gender covariate (0 = female) was statistically significant.

TABLE 2.

Pearson correlations among study variables

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Hope | ||||||||

| 2. School connectedness | .29 ** /.43 ** | |||||||

| 3. Difficulty switching to online learning | −.08/−.07 | −.02/ .03 | ||||||

| 4. Education is suffering due to disruption | −.14/−.12 | −.08/−.06 | .66 ** /.66 ** | |||||

| 5. Not seeing friends | −.07/−.10 | −.01/.01 | .32 ** /.26 ** | .23 ** /.26 ** | ||||

| 6. Not attending social events | −.05/−.03 | .10*/ .07 | .33 ** /.28 ** | .24 ** /.22 ** | .58 ** /.61 ** | |||

| 7. Catching COVID‐19 | .12/−.04 | .15 ** /.01 | .10 * /.13 * | .18 ** /.1 * | .21 ** /.19 ** | .26 ** /.24 ** | ||

| 8. Friends/family catching COVID‐19 | .12/.01 | .13 ** /.06 | .16 ** /.13 * | .15 ** /.08 | .30 ** /.26 ** | .33 ** /.28 ** | .68 ** /.68 ** | |

| 9. Thinking about future of society | .10/.06 | .07/.03 | .26 ** /.28 ** | .28 ** /.24 ** | .33 ** /.31 ** | .25 ** /.34 ** | .32 ** /.38 ** | .46 ** /.42 ** |

Notes: Middle school results are presented before high school results in bold. #3–4 are education concerns related to COVID‐19 (2021); #5–7 are life distress questions related to COVID‐19 (2021). The item asking about students' motivation compared with last year was not included given the ordinal nature of the responses. For the hope measure, the agency and pathways subscales were significantly correlated at .69 and .73 for middle and high school, respectively.

p < .05.

p < .01.

6.1. Perceptions of educational disruptions and life as related to COVID‐19

6.1.1. Educational disruptions related to COVID‐19

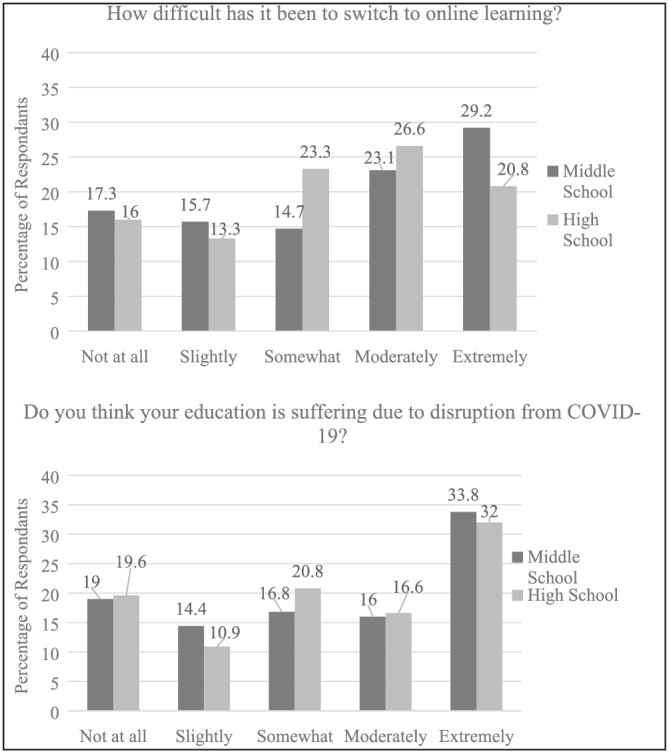

Approximately half of all students (in both MS and HS) felt that the switch to online learning had been moderately or extremely difficult and that their education had suffered moderately to extremely (Figure 1). There were no mean‐level differences by school level on either question (see Table 1 for statistics).

FIGURE 1.

Students' perceptions of educational disruptions due to COVID‐19

When asked how motivated students were to do work now compared with last school year, 39% of MS students reported being much less motivated, 43% had about the same motivation, and 18% were much more motivated. Among HS students, 45% reported being much less motivated, 36% had about the same motivation, and 19% were much more motivated. The chi‐square test of motivation level differences by school level was not significant, χ2(2) = 3.82, P = 0.15.

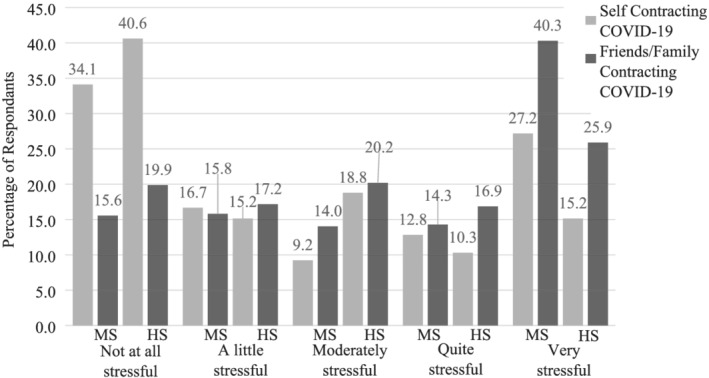

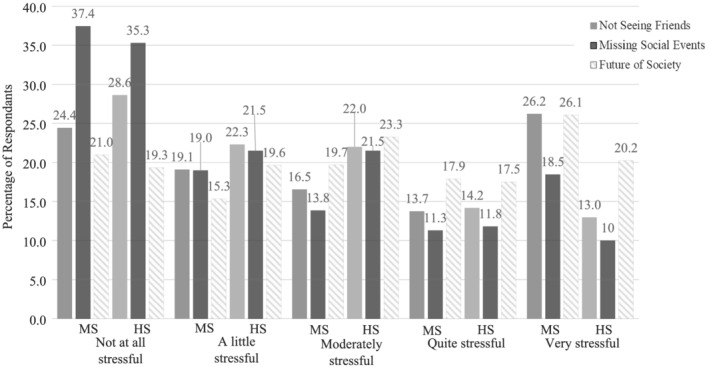

6.1.2. Life concerns related to COVID‐19

Of note, over 50% of MS students reported thinking about their friends/family members contracting COVD‐19 as either quite or very stressful. Around 44% of MS and 38% of HS students felt that thinking about the future of society was quite or very stressful. Figures 2 and 3 show frequencies of responses to each item by school level. A MANCOVA showed that there were school‐level differences in life concerns related to COVID‐19 (see Table 1 for statistics).

FIGURE 2.

Students' concern about contracting COVID‐19. HS, high school; MS, middle school

FIGURE 3.

Students' concern about life experiences as related to COVID‐19. HS, high school; MS, middle school

6.1.3. Students' perceived challenges and positive aspects of life during COVID‐19

Students' open‐ended responses to ‘the biggest challenge’ and ‘the best thing’ in their lives were categorized and counted. In both MS and HS, the top three challenges described were school (45%, 40%), COVID‐19 (7%, 4%) and the future (4%, 6%). Both MS and HS students also reported not having any challenges (4% for each school level). See Table 3 for exemplar quotes for each category.

TABLE 3.

Examples of qualitative responses to for top themes

| Challenges |

| School |

| ‘Online school and group projects because they make us work with people and no one talks so I have to do the whole thing alone’. MS student |

| ‘My biggest challenge is being in remote learning and really try to take in what is being taught to me for me to remember in the long run’. HS student |

| ‘My biggest challenge is trying to get all my school work done because the teachers leave a lot of work and it is very stressful’. HS student |

| ‘School is the biggest challenge I face I use to have A's and B's when we were in person now it is too much for me’. MS student |

| ‘Not being able to have the face to face one on one time with the teachers to help if I do not understand something’. HS student |

| ‘The biggest challenge in my life right now is staying motivated to do school because I honestly lost all motivation’. HS student |

| ‘Not being able to fully put my attention in the lesson because its not the same as in person’. HS student |

| COVID‐19 |

| ‘COVID and not being able to do certain things that I want’. HS student |

| ‘The biggest challenge in my life right now is thinking my family will catch covid’. MS student |

| ‘The biggest challenge in my life right now is trying to stay safe from Covid’. MS student |

| ‘My challenge in life is hoping me or any friends or family do not get the coronavirus’. MS student |

| ‘My biggest challenge in life right now is covid‐19 and how uncertain it makes me feel’. HS student |

| Future |

| ‘Thinking about and preparing for the future of our nation and society as a whole’. HS student |

| ‘Thinking about the future’. MS student |

| ‘Just figuring out what comes after high school’. HS student |

| Positive Aspects |

| Interpersonal Relationships/Interactions |

| ‘The best thing my life at the moment are having my family and friends to talk to when time get stressful’. MS student |

| ‘The best things in my life right now is the love and support I get from my family and friends’. MS student |

| ‘My friends even tho we cannot hang out everyday like we used to they always got my back and they are like sisters to me I do not know what to do without them’. MS student |

| ‘The best thing in my life is being able to stay home with my family the entire day instead o only a couple hours each day’. MS student |

| ‘The best thing in my life right now is my family. I am grateful that I am able to spend time with them and I am glad that they are still here with me. It's reassuring and calming. They helped me every step along the way and they guide me when they know that I am doing something wrong. They let me talk about little problems and understand me’. HS student |

| ‘The best thing in my life right now is spending more time with my parents because I hardly spent time with them’. HS student |

| School |

| ‘The best thing in my life right now is that I'm doing alright in school and that I'm understanding much better’. MS student |

| ‘Getting to have good grades more than last year’. MS student |

| ‘My drive to be successful in school’. HS student |

| ‘The best thing in my life is that I've been able to keep up good grades throughout the whole year so far, and I'm honestly so proud of myself for it’. HS student |

| ‘Still being able to do school’. HS student |

| Hobbies |

| ‘Playing the guitar’. MS student |

| ‘Going to the gym’. HS student |

| ‘The best thing in my life right now is getting back into sports’. HS student |

| ‘Skateboarding and dirt bike riding’. MS student |

| ‘Video games’. HS student |

Notes: MS = middle school; HS = high school. Responses were lightly edited for capitalization and punctuation.

In MS and HS, the Top 3 positive aspects of their lives were interpersonal relationship/interactions (44%, 41%), school (8%, 6%) and hobbies (5%, 8%). See Table 2 for exemplar quotes for each category. Interestingly, 30 students (3.5% of the entire sample) reported ‘nothing’ as being the best thing in their lives.

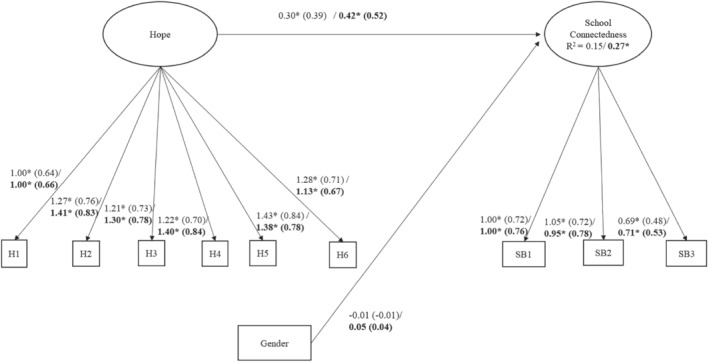

6.2. Pre‐pandemic hope predicting 2021 school connectedness

To examine if 2020 hope predicted students' 2021 school connectedness, we conducted SEM models, separate by school level, where 2020 hope and 2021 school connectedness were latent variables and gender was a covariate. The measurement models with the latent variables showed good fit (MS: χ 2 (26) = 37.17, P = .07; RMSEA = .03; RMSEA 90% confidence interval = 0.00, 0.06; CFI = .98; SRMR = .05; HS: χ 2 (26) = 46.47, P = .01; RMSEA = .05; RMSEA 90% confidence interval = 0.03, 0.07; CFI = .97; SRMR = .04). All items significantly loaded onto their respective constructs and the standardized loadings ranged from 0.48 to 0.84 for the MS model and from 0.53 to 0.84 for the HS model. In both models, only a single item (the same item in both models) fell below 0.64, which loaded onto the school connection variable. We retained that item for theoretical reasons and given the limited number of items to measure school connectedness.

When examining the structural model for MS students, the model fit was good, χ 2 (34) = 48.22, P = .05; RMSEA = .03; RMSEA 90% confidence interval = 0.00, 0.05; CFI = .97; SRMR = .06. Hope (2020) positively significantly predicted 2021 school connectedness (B = .30, P < .01; R 2 = 0.15). For HS students, the structural model fit was good, χ 2 (34) = 58.44, P = .01; RMSEA = .05; RMSEA 90% confidence interval = 0.03, 0.07; CFI = .97; SRMR = .04). Hope (2020) positively significantly predicted 2021 school connectedness (B = .42, P < .01; R 2 = 0.27). Gender, which was included as a covariate was not significant in either model. See Figure 4 for all parameter estimates.

FIGURE 4.

Structural equation model of latent hope predicting latent school connectedness. *P < .01. Middle school parameter estimates are presented first, followed by high school parameter estimates in bold. Unstandardized parameter estimates are followed by standardized parameter estimates in parentheses.

7. DISCUSSION

The present study examined students' perceptions about education and life 1 year into the COVID‐19 pandemic. Overall, results showed that most students felt that switching to online learning had been difficult and their education had suffered at least moderately, with a sizeable proportion of students feeling less motivated compared with last year. Even still, students' 2020 hope positively predicted students' feelings of school connectedness. Interestingly, in terms of life concerns related to COVID‐19, some of the patterns that emerged appeared to be different across school level, with MS students reporting higher levels of concern than HS students in a number of areas; yet, when asked to share qualitative answers regarding perceived challenges and positive aspects of life, the same themes emerged across school level. Findings highlight students' own perceptions with implications for support as societal restrictions are lifted.

7.1. Life concerns, disruptions and positive aspects

Our first research question attempted to understand middle and high school students' perceptions of the severity of the pandemic's influence on multiple aspects of life including school, health and social lives. Students' quantitative responses to life disruptions related to COVID‐19 were mostly consistent with the themes that emerged in their qualitative responses regarding their ‘biggest current challenge’. The Top 3 qualitative challenges reported were school, COVID‐19 and the future. Given the serious changes to schooling during the pandemic, it is not surprising that issues surrounding school were cited as a challenge for a large proportion of students. This finding aligns with research conducted in May 2020 where students were asked to qualitatively report on their biggest COVID‐19 challenges and 23.7% of adolescents reported challenges related to academics (Scott et al., 2021). It may be that more students in the present study (40%–45%) reported challenges related to school because they had been immersed in virtual schooling for an extended period, which highlights the felt pressure of online/remote schooling with time. Although the initial switch to online learning may have been an acute shock, it could be that persisting conditions have led to even more fatigue than the initial transition.

The next most often reported qualitative concern was COVID‐19 (generally); the quantitative data showed that over half of students felt that concerns about their family/friends contracting COVID‐19 was quite or very high, whereas their concern for themselves contracting COVID‐19 was relatively low or not stressful. This finding aligns with other research that showed 43% of HS students were very concerned about COVID‐19 in general and students expressed more concern that someone they know would become infected than themselves (Ellis et al., 2020). This finding could reflect adolescents' awareness that older and medically compromised individuals are more prone than teens to have severe complications when contracting COVID‐19.

The third most often reported qualitative theme regarded students' futures. The proportion of responses (4%–5%) citing concerns for the future in the present study aligned with extant work (Scott et al., 2021). It is interesting that there was consistency in percentage of students responding this way as compared with previous work, even though the data in the present study were collected much later in the pandemic. It could be that COVID‐19 vaccination efforts played a role in how students responded. At the time of data collection (February 2021), vaccine administration was increasing, with an emphasis on steps to ‘return to normal’. Further, there was some disconnect in terms of how stressful students quantitatively reported thinking about the future of society as related to COVID‐19, with a sizeable portion of students reporting it was quite or very stressful (44% MS, 37% HS) when responding to the quantitative questions. It could be that when asked to arrive at their own conclusions about challenges, thinking about the future was not necessarily at the forefront of their minds, especially given the consistent, every day focus on schooling. However, it is important to acknowledge that quantitative responses showed students reported thinking about the future as very stressful and high levels of stress can have negative implications for student's well‐being both psychologically and academically (Burkhart et al., 2017; Repetti et al., 1999; Sisk & Gee, 2022).

Importantly, school‐level differences emerged on three of the quantitative life concerns (i.e. not seeing friends, catching COVID‐19 and friends/family catching COVID‐19), with MS students expressing more concern than HS students. Previous research has shown that, in general, adolescents' stress tends to decrease with age (Seiffge‐Krenke et al., 2009). It may be that this pattern of gradual decrease is reflected in the MS students' reporting higher stress levels than the HS students. Additionally, as youth enter later adolescence, they begin to utilize more advanced coping skills, such as seeking others for support and employing more cognitively complex thought processes (e.g. imaging solutions and outcomes) surrounding problems (Seiffge‐Krenke et al., 2009). The aforementioned approaches may have helped the older adolescents manage their stress surrounding COVID‐19. The school‐level differences on stress items within the present study highlight the importance of potentially targeting MS students for intervention to help them cultivate coping skills as COVID‐19 continues to be present.

7.1.1. Positive aspects

It is critical to understand not only how students have struggled during the pandemic but also what helped them thrive, especially if those positive aspects of their lives could be further nurtured and/or used as sources of support. Students overwhelmingly mentioned their relationships and interactions with others as being the best aspects of their lives during the pandemic, followed by school and hobbies. This finding highlights the importance of social connections even during times of physical social distancing (Orben et al., 2020) and aligns with research showing the importance of peer interactions during adolescence. Research published focusing on COVID‐19 and adolescent outcomes has shown that strong social ties have been critical in supporting youth's psychological well‐being during the pandemic (Bernasco et al., 2021; Hutchinson et al., 2021; Parent et al., 2021), likely because these interactions help relieve stress surrounding many aforementioned areas of concern. Both school and hobbies may be positive aspects of students' lives as they help provide a sense of normalcy/routine. Indeed, with so much disruption overall, a daily academic and extracurricular schedule may help youth feel grounded and secure despite high levels of uncertainty in other areas. During times of high stress, such as a pandemic, adults can help support youth in identifying and engaging with the positive aspects of their lives to reduce stress and promote well‐being (Ronen et al., 2014). Our findings support consistent daily activities and social support as some such positive aspects, even if circumstances call for these activities to look different (e.g. observing social distancing, connecting online, etc.).

7.2. Hope and school connectedness

For both MS and HS students, pre‐pandemic hope positively predicted feelings of school connectedness during the pandemic. This finding aligns with extant research during non‐pandemic times (You et al., 2008), and the consistency seems of particular relevance, given the rapid shift to remote learning. It is possible that hope promotes school connection because students with high hope are able to identify their goals and recognize how school can support their goal attainment (Fraser et al., 2022). In turn, they may feel a stronger connection because of their ability to identify the relevance and importance of school for them. Practically, hope may be an important cognitive‐motivational skill to support students' re‐entry onto campuses after, potentially, more than a year of remote learning.

Indeed, previous research has shown that hope is a skill that can be taught and cultivated during adolescence, a developmental period in which youth set increasingly complex goals and make autonomous choices (McDermott & Hastings, 2000; Snyder et al., 2002). In light of the pandemic, adult socializers (e.g. teachers, school counsellors and parents) can help adolescents learn how to set meaningful goals and remind youth to use their past goal pursuit experience as a way to take appropriate steps, be it changing the approach or utilizing the same approach, to promote future goal pursuit (Snyder et al., 2002). In this way, adults can help the student learn that hope is iterative and that the student can draw upon their lived experience during the pandemic in a way that will support their future goals. Further, adults can be an important social support for students by reminding them that there are numerous paths to goal completion and that obstacles (such as those related to the pandemic) can be overcome, especially when students are feeling defeated or less sure of themselves. School interventions utilizing the aforementioned approaches have been successfully implemented during this developmental period (McDermott & Hastings, 2000). Taken together, in the context of the COVID‐19 pandemic, hope may help students reinvest in and reacclimate to in‐person learning by helping them identify new goals, plan routes to goal attainment and feel efficacious in that attainment. Parents and educators can actively assist in this process.

Not surprisingly, students shared feelings of decreased motivation, moderate to extreme concerns about difficulty switching to an online modality and that their education had suffered due to COVID‐19. Our findings are consistent with other research on youth concerns during the pandemic (Zaccoletti et al., 2020). These findings are particularly interesting juxtaposed with the finding that hope supported school connectedness. Indeed, hope may be an important protective factor moving forward to help students plan ways to overcome educational disruptions, pandemic‐related or otherwise, and to support and promote motivation, particularly as students begin to return to in‐person learning.

7.3. Limitations and future direction

The findings from the present study provide a much‐needed insight into students' perceptions and concerns surrounding the pandemic, and the potential for hope to help them in the transition back to school; however, it is not without limitation. We only included a single school district, which may decrease generalizability; specifically, our sample precluded us from examining patterns across different geographic locations, or differing remote‐schooling structures, that may have differentially been affected by the COVID‐19 pandemic. More research is necessary that investigates perceptions among students at various ages from multiple districts. Furthermore, although we conducted an analysis with estimators robust to missing data for the SEM model, and believe that the missing data were missing at random, we are unable to ascertain why there was a mean‐level difference in school connectedness between those with and without hope scores. Future studies should attempt to replicate these findings with less missing data. Students' responses to the open‐ended questions were grouped into broad categories, as the majority of students only included one‐ to two‐word answers; this limited our ability to pursue more in‐depth analyses. Future work should focus on asking questions that provoke more elaborate responses to better understand the intricacies of students' perceptions.

Additionally, the present study did not have access to information regarding family demographics (e.g. socio‐economic status, living situation, social mobility and neighbourhood data) or parent–child relationships. During the pandemic, it is possible that students' experiences were different across family‐level demographic data, particularly with regard to caregiver involvement at home for remote schooling, necessary work outside of the home and students having to take on additional responsibilities due to the pandemic and their caregivers' schedules. More research is necessary that incorporates these contextual factors. Lastly, as it was not within the scope of the study, future research is needed that examines how students' hope, school connectedness, life concerns and educational disruptions may have manifested different by varying demographic groups (e.g. urbanicity and race/ethnicity).

As students continue to return to classrooms, it is important that researchers, educators and caregivers understand how students' perceptions regarding their lives and educational disruptions have manifested during a year of online schooling and the pandemic and the potential role that hope can play as a protective factor. Fostering students' hope may help them connect with school and readjust to in‐person learning more quickly. Furthermore, because many students reported declines in their motivation during online school, supporting students' goals and hope skills may help increase their school motivation. In general, the knowledge gained regarding students' concerns and positive experiences from the present study present an early look at how the COVID‐19 pandemic has affected students and may serve as a starting point when examining long‐term effects of the pandemic on youth in the future.

Bryce, C. I. , & Fraser, A. M. (2022). Students' perceptions, educational challenges and hope during the COVID‐19 pandemic. Child: Care, Health and Development, 1–13. 10.1111/cch.13036

Funding information

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial or not‐for‐profit sectors.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, upon reasonable request.

REFERENCES

- Bernasco, E. L. , Nelemans, S. A. , van der Graaff, J. , & Branje, S. (2021). Friend support and internalizing symptoms in early adolescence during COVID‐19. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 31(3), 692–702. 10.1111/jora.12662 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burkhart, M. L. , Horn Mallers, M. , & Bono, K. E. (2017). Daily reports of stress, mood, and physical health in middle childhood. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 26(5), 1345–1355. 10.1007/s10826-017-0665-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Christ, C. C. , & Gray, J. M. (2022). Factors contributing to adolescents' COVID‐19‐related loneliness, distress, and worries. Current Psychology, 1–12. 10.1007/s12144-022-02752-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Figueiredo, C. S. , Sandre, P. C. , Portugal, L. C. L. , Mázala‐de‐Oliveira, T. , da Silva Chagas, L. , Raony, Í. , Ferreira, E. S. , Giestal‐de‐Arjuo, E. , Arujo dos Sanots, A. , & Bomfim, P. O. S. (2021). COVID‐19 pandemic impact on children and adolescents' mental health: Biological, environmental, and social factors. Progress in Neuro‐Psychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry, 106, 110171. 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2020.110171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixson, D. D. , & Scalcucci, S. G. (2021). Psychosocial perceptions and executive functioning: Hope and school belonging predict students' executive functioning. Psychology in the Schools, 58(5), 853–872. 10.1002/pits.22475 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dvorsky, M. R. , Breaux, R. , & Becker, S. P. (2020). Finding ordinary magic in extraordinary times: Child and adolescent resilience during the COVID‐19 pandemic. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 30(11), 1829–1831. 10.1007/s00787-020-01583-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis, W. E. , Dumas, T. M. , & Forbes, L. M. (2020). Physically isolated but socially connected: Psychological adjustment and stress among adolescents during the initial COVID‐19 crisis. Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science/Revue Canadienne des Sciences Du Comportement, 52(3), 177–187. 10.1037/cbs0000215 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fraser, A. M. , Alexander, B. L. , Abry, T. , Sechler, C. , & Fabes, R. A. (2022). Youth hope and educational contexts. In Fisher D. (Ed.), Routledge encyclopedia of education (online). Taylor & Francis. [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher, M. W. , Smith, L. J. , Richardson, A. L. , D'Souza, J. M. , & Long, L. J. (2021). Examining the longitudinal effects and potential mechanisms of hope on COVID‐19 stress, anxiety, and well‐being. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, 50(3), 234–245. 10.1080/16506073.2021.1877341 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glass, K. , Flory, K. , Hankin, B. L. , Kloos, B. , & Turecki, G. (2009). Are coping strategies, social support, and hope associated with psychological distress among hurricane Katrina survivors? Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 28(6), 779–795. 10.1521/jscp.2009.28.6.779 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Golberstein, E. , Wen, H. , & Miller, B. F. (2020). Coronavirus disease 2019 (covid‐19) and mental health for children and adolescents. JAMA Pediatrics, 174(9), 819–820. 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.1456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grusec, J. E. , & Goodnow, J. J. (1994). Impact of parental discipline methods on the child's internalization of values: A reconceptualization of current points of view. DevelopmentalPsychology, 30(1), 4–19. 10.1037/0012-1649.30.1.4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hu, L. T. , & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55. 10.1080/10705519909540118 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Y. , Ye, B. , & Im, H. (2021). Hope and post‐stress growth during COVID‐19 pandemic: The mediating role of perceived stress and the moderating role of empathy. Personality and Individual Differences, 178, 110831. 10.1016/j.paid.2021.110831 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutchinson, E. A. , Sequeira, S. L. , Silk, J. S. , Jones, N. P. , Oppenheimer, C. , Scott, L. , & Ladouceur, C. D. (2021). Peer connectedness and pre‐existing social reward processing predicts US adolescent Girls' suicidal ideation during COVID‐19. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 31(3), 703–716. 10.1111/jora.12652 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones, E. A. , Mitra, A. K. , & Bhuiyan, A. R. (2021). Impact of covid‐19 on mental health in adolescents: A systematic review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(5), 2470. 10.3390/ijerph18052470 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasler, J. , Dahan, J. , & Elias, M. J. (2008). The relationship between sense of hope, family support and post‐traumatic stress disorder among children: The case of young victims of rocket attacks in Israel. Vulnerable Children and Youth Studies, 3(3), 182–191. 10.1080/17450120802282876 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Klootwijk, C. L. , Koele, I. J. , Van Hoorn, J. , Güroğlu, B. , & van Duijvenvoorde, A. C. (2021). Parental support and positive mood buffer Adolescents' academic motivation during the COVID‐19 pandemic. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 31, 780–795. 10.1111/jora.12660 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroger, J. (2004). Identity in adolescence: The balance between self and other. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Kronenberg, M. E. , Hansel, T. E. , Brennan, A. M. , Osofsky, H. J. , Osofsky, J. D. , & Lawrason, B. (2010). Children of Katrina: Lessons learned about post disaster symptoms and recovery patterns. Child Development, 81(4), 1241–1259. 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01465.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levi, U. , Einav, M. , Ziv, O. , Raskind, I. , & Margalit, M. (2014). Academic expectations and actual achievements: The roles of hope and effort. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 29(3), 367–386. 10.1007/s10212-013-0203-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y. , Carney, J. V. , Kim, H. , Hazler, R. J. , & Guo, X. (2020). Victimization and students' psychological well‐being: The mediating roles of hope and school connectedness. Children and Youth Services Review, 108, 104674. 10.1016/j.childyouth.2019.104674 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Magson, N. R. , Freeman, J. Y. , Rapee, R. M. , Richardson, C. E. , Oar, E. L. , & Fardouly, J. (2021). Risk and protective factors for prospective changes in adolescent mental health during the COVID‐19 pandemic. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 50(1), 44–57. 10.1007/s10964-020-01332-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maiya, S. , Dotterer, A. , & Whiteman, S. (2021). Longitudinal changes in adolescents' school bonding during the COVID‐19 pandemic: Individual, parenting, and family correlates. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 31(3), 809–819. 10.1111/jora.12653 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mancini, J. A. , Bowen, G. L. , Martin, J. A. , & Ware, W. B. (2003). The community connections index: Measurement of community engagement and sense of community. In Hawaii International Conference on the Social Sciences, Honolulu.

- Marques, S. C. , Gallagher, M. W. , & Lopez, S. J. (2017). Hope‐ and academic‐related outcomes: A meta‐analysis. School Mental Health, 9(3), 250–262. 10.1007/s12310-017-9212-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McDermott, D. , & Hastings, S. (2000). Children: Raising future hopes. In Snyder C. R. (Ed.), Handbook of hope (pp. 185–199). Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mcelrath, K. (2020). Schooling during the COVID‐19 pandemic. United States Census Bureau. www.census.gov/library/stories/2020/08/schooling-during-the-covid-19-pandemic.html. Accessed May 01, 2021.

- Meléndez Guevara, A. M. , Gaias, L. M. , Fraser, A. M. , & Lindstrom Johnson, S. (2021). Violence exposure, aggressive cognitions & externalizing behaviors among Colombian youth: The moderating role of community belongingness. Youth Society, 0044118X2110154. 10.1177/0044118x211015446 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Orben, A. , Tomova, L. , & Blakemore, S.‐J. (2020). The effects of social deprivation on adolescent development and mental health. The Lancet Child & Adolescent Health, 4(8), 634–640. 10.1016/s2352-4642(20)30186-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parent, N. , Dadgar, K. , Xiao, B. , Hesse, C. , & Shapka, J. (2021). Social disconnection during COVID‐19: The role of attachment, fear of missing out, and smartphone use. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 31(3), 748–763. 10.1111/jora.12658 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravens‐Sieberer, U. , Kaman, A. , Erhart, M. , Devine, J. , Schlack, R. , & Otto, C. (2021). Impact of the COVID‐19 pandemic on quality of life and mental health in children and adolescents in Germany. European Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Advance online publication, 31, 879–889. 10.1007/s00787-021-01726-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Repetti, R. L. , McGrath, E. P. , & Ishikawa, S. S. (1999). Daily stress and coping in childhood and adolescence. In Goreczny A. J. & Hersen M. (Eds.), Handbook of pediatric and adolescent Health Psychology (pp. 343–360). Allyn & Bacon. [Google Scholar]

- Ronen, T. , Hamama, L. , Rosenbaum, M. , & Mishely‐Yarlap, A. (2014). Subjective well‐being in adolescence: The role of self‐control, social support, age, gender, and familial crisis. Journal of Happiness Studies, 17(1), 81–104. 10.1007/s10902-014-9585-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Samji, H. , Wu, J. , Ladak, A. , Vossen, C. , Stewart, E. , Dove, N. , Long, D. , & Snell, G. (2021). Mental health impacts of the COVID‐19 pandemic on children and youth–a systematic review. Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 27, 173–189. 10.1111/camh.12501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott, S. R. , Rivera, K. M. , Rushing, E. , Manczak, E. M. , Rozek, C. S. , & Doom, J. R. (2021). “I hate this”: A qualitative analysis of adolescents' self‐reported challenges during the COVID‐19 pandemic. Journal of Adolescent Health, 68(2), 262–269. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.11.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seiffge‐Krenke, I. , Aunola, K. , & Nurmi, J.‐E. (2009). Changes in stress perception and coping during adolescence: The role of situational and personal factors. Child Development, 80(1), 259–279. 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2008.01258.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sisk, L. M. , & Gee, D. G. (2022). Stress and adolescence: Vulnerability and opportunity during a sensitive window of development. Current Opinion in Psychology, 44, 286–292. 10.1016/j.copsyc.2021.10.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder, C. R. (2002). Target article: Hope theory: Rainbows in the mind. Psychological Inquiry, 13(4), 249–275. 10.1207/s15327965pli1304_01 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder, C. R. , Feldman, D. B. , Shorey, H. S. , & Rand, K. L. (2002). Hopeful choices: A school counselor's guide to hope theory. Professional School Counseling, 5(5), 298. [Google Scholar]

- Snyder, C. R. , Hoza, B. , Pelham, W. E. , Rapoff, M. , Ware, L. , Danovsky, M. , Highberger, L. , Ribinstein, H. , & Stahl, K. J. (1997). The development and validation of the Children's hope scale. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 22(3), 399–421. 10.1093/jpepsy/22.3.399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sprang, G. , & Silman, M. (2013). Posttraumatic stress disorder in parents and youth after health‐related disasters. Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness, 7(1), 105–110. 10.1017/dmp.2013.22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tottenham, N. , & Galván, A. (2016). Stress and the adolescent brain. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 70, 217–227. 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2016.07.030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valle, M. F. , Huebner, E. S. , & Suldo, S. M. (2004). Further evaluation of the Children's hope scale. Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment, 22(4), 320–337. 10.1177/073428290402200403 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Van Ryzin, M. J. (2011). Protective factors at school: Reciprocal effects among adolescents' perceptions of the school environment, engagement in learning, and hope. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 40, 1568–1580. 10.1007/s10964-011-9637-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White House COVID‐19 Team JCC . (2021, January 22). Covid‐19 state profile report ‐ Arizona. HealthData.gov. https://healthdata.gov/Community/COVID-19-State-Profile-Report-Arizona/iuqv-5x8z. Accessed October 20, 2021.

- Witherspoon, D. P. , & Hughes, D. L. (2014). Early adolescent perceptions of neighborhood. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 34(7), 866–895. 10.1177/0272431613510404 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yıldırım, M. , & Arslan, G. (2020). Exploring the associations between resilience, dispositional hope, preventive behaviours, subjective well‐being, and psychological health among adults during early stage of COVID‐19. Current Psychology, 1–11. 10.1007/s12144-020-01177-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- You, S. , Furlong, M. J. , Felix, E. , Sharkey, J. D. , Tanigawa, D. , & Green, J. G. (2008). Relations among school connectedness, hope, life satisfaction, and bully victimization. Psychology in the Schools, 45(5), 446–460. 10.1002/pits.20308 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zaccoletti, S. , Camacho, A. , Correia, N. , Aguiar, C. , Mason, L. , Alves, R. A. , & Daniel, J. R. (2020). Parents' perceptions of student academic motivation during the COVID‐19 lockdown: A cross‐country comparison. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 529670. 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.592670 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, X. (2020). Managing psychological distress in children and adolescents following the covid‐19 epidemic: A cooperative approach. Psychological Trauma Theory Research Practice and Policy, 12(S1), S76–S78. 10.1037/tra0000754 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, S. , Zhuang, Y. , & Ip, P. (2021). Impacts on children and adolescents' lifestyle, social support and their association with negative impacts of the COVID‐19 pandemic. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(9), 4780. 10.3390/ijerph18094780 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, upon reasonable request.