Abstract

Aims

Blood uric acid (UA) levels are frequently elevated in patients with heart failure and reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF), may lead to gout and are associated with worse outcomes. Reduction in UA is desirable in HFrEF and sodium–glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors may have this effect. We aimed to examine the association between UA and outcomes, the effect of dapagliflozin according to baseline UA level, and the effect of dapagliflozin on UA in patients with HFrEF in the DAPA‐HF trial.

Methods and results

The association between UA and the primary composite outcome of cardiovascular death or worsening heart failure, its components, and all‐cause mortality was examined using Cox regression analyses among 3119 patients using tertiles of UA, after adjustment for other prognostic variables. Change in UA from baseline over 12 months was also evaluated. Patients in tertile 3 (UA ≥6.8 mg/dl) versus tertile 1 (<5.4 mg/dl) were younger (66.3 ± 10.8 vs. 68 ± 10.2 years), more often male (83.1% vs. 71.5%), had lower estimated glomerular filtration rate (58.2 ± 17.4 vs. 70.6 ± 18.7 ml/min/1.73 m2), and more often treated with diuretics. Higher UA was associated with a greater risk of the primary outcome (adjusted hazard ratio tertile 3 vs. tertile 1: 1.32, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.06–1.66; p = 0.01). The risk of heart failure hospitalization and cardiovascular death increased by 7% and 6%, respectively per 1 mg/dl unit increase of UA (p = 0.04 and p = 0.07). Spline analysis revealed a linear increase in risk above a cut‐off UA value of 7.09 mg/dl. Compared with placebo, dapagliflozin reduced UA by 0.84 mg/dl (95% CI −0.93 to −0.74) over 12 months (p < 0.001). Dapagliflozin improved outcomes, irrespective of baseline UA concentration.

Conclusion

Uric acid remains an independent predictor of worse outcomes in a well‐treated contemporary HFrEF population. Compared with placebo, dapagliflozin reduced UA and improved outcomes irrespective of UA concentration.

Keywords: Heart failure, Uric acid, Mortality, Sodium–glucose cotransporter 2, Diabetes

Importance of uric acid in patients with heart failure and reduced ejection fraction (EF) and effect of dapagliflozin. NYHA, New York Heart Association.

Introduction

Uric acid (UA) is the final product of purine metabolism and blood levels reflect dietary intake of purines, synthesis of UA by xanthine oxidase and excretion of UA, mainly by the kidneys. Consequently, UA may be elevated in heart failure because elimination is reduced due to impaired kidney function and because diuretics impair uric acid excretion. 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 UA may also be increased because of increased production due to greater xanthine oxidase activity in patients with heart failure. 6 , 7 As a result, hyperuricaemia is common in heart failure and higher UA is associated with worse clinical outcomes. 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 The association between higher UA and worse outcomes persists after adjustment for renal function, diuretic use and dose, and natriuretic peptide levels. 9 , 10 , 11 Whether this is due to unmeasured confounding, or a directly injurious effect of UA is unknown. 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 However, UA increases cytokine and chemokine production, promotes inflammation, impairs endothelial function and activates the renin–angiotensin system. 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 In addition, UA may be a marker of oxidative stress as xanthine oxidase generates superoxide along with UA. 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 Hyperuricaemia can also lead to gout which is common in patients with heart failure, is difficult to manage and may lead to and prolong hospitalization. 12 , 13 Therefore, drugs are frequently used, prophylactically, to reduce UA in patients with heart failure, with approximately 15%–20% of patients treated in this way. 9

For these reasons, the effect of therapies for heart failure on UA is of interest and agents that lower UA have even been investigated as a potential treatment for heart failure. 14 , 15 The angiotensin receptor blocker losartan inhibition has been shown to reduce UA in patients without heart failure and neprilysin inhibition also reduces UA in patients with both heart failure with reduced (HFrEF) and preserved ejection fraction. 5 , 11 , 16 Recently, sodium–glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors have been shown to reduce hospitalization and death in patients with HFrEF. 17 , 18 , 19 These drugs also reduce UA in patients with diabetes, although the exact mechanism of this effect is not understood and whether SGLT2 inhibitors also reduce UA in patients without diabetes is unknown. 20 , 21 , 22 , 23

Therefore, we assessed the effect of dapagliflozin on UA in patients with HFrEF, with and without type 2 diabetes, enrolled in the Dapagliflozin and Prevention of Adverse‐outcomes in Heart Failure trial (DAPA‐HF). 17 We also examined whether UA remains an independent predictor of adverse outcomes in patients receiving optimum contemporary treatment for HFrEF.

Methods

DAPA‐HF was a randomized double‐blind, placebo‐controlled, event‐driven trial in patients with HFrEF, with or without type 2 diabetes. The design, baseline characteristics, and primary results are published. 17 , 24 , 25 Ethics Committees for the 410 participating institutions in 20 countries approved the protocol and all patients gave written informed consent.

Study patients and treatment

Patients in New York Heart Association (NYHA) functional class II–IV, with a left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) ≤40%, and an elevated N‐terminal pro‐B‐type natriuretic peptide (NT‐proBNP) concentration, were eligible if receiving standard pharmacological and device therapy. The key exclusion criteria were: type 1 diabetes mellitus, symptomatic hypotension/systolic blood pressure <95 mmHg, and an estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) <30 ml/min/1.73 m2. Dapagliflozin10 mg was compared to a matching placebo, taken once daily in addition to standard treatment.

Measurement of uric acid

Blood samples were taken at randomization and 52 weeks. UA was measured using stored EDTA plasma in a central laboratory using an automated platform and the manufacturer's calibration and quality control materials (c311, Roche Diagnostics, Burgess Hill, UK). The coefficient of variation was 2.0% for a low control and 2.8% for a high control.

Outcomes

The primary trial outcome was the composite of worsening heart failure event (heart failure hospitalization or urgent visit for heart failure requiring intravenous therapy) or cardiovascular death, whichever occurred first. In this study, we investigated the association between baseline UA and the risk of the primary outcome, its composites, and all‐cause mortality. We also examined the effect of dapagliflozin according to baseline UA analysed as a categorical and continuous variable (see below).

In addition, we examined the effect of dapagliflozin on UA level after randomization (difference between baseline and 12‐month measurement) and initiation of new UA‐lowering therapy.

Statistical analysis

Serum UA levels at baseline were categorized into tertiles. Baseline characteristics according to serum UA tertile are presented as frequencies and percentages for categorical variables and means with standard deviation or medians with interquartile range (IQR) for continuous variables. A non‐parametric test for trend across groups, an extension of the Wilcoxon rank sum test, was used to examine for variation in baseline characteristics across UA tertiles. Use of oral loop diuretics at baseline was grouped in categories of furosemide equivalents: 40 mg furosemide = 20 mg torsemide = 1 mg bumetanide. Non‐loop diuretics were categorized as thiazides or as ‘other’.

Incidence rates for each outcome of interest are presented per 100 person‐years of follow‐up. Event rates in each UA tertile were estimated by the Kaplan–Meier method and compared using the log‐rank test. Cox proportional hazards regression models stratified by diabetes status and adjusted for heart failure hospitalization (except for all‐cause mortality) and randomized treatment group were used to compare hazard ratios (HR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) for outcomes according to UA tertiles. In multivariable models, the HR was further adjusted for the following baseline characteristics: age, sex, pulse, systolic blood pressure, body mass index, atrial fibrillation, diabetes status, aetiology of heart failure, LVEF, NYHA functional classification, NT‐proBNP (log), eGFR, non‐loop diuretic use, loop diuretic use dose and use of an angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitor, angiotensin receptor blocker or angiotensin receptor–neprilysin inhibitor.

The association between UA and each outcome was also assessed using a restricted cubic spline with five knots, using UA of 7.0 mg/dl as a reference in the same multivariable‐adjusted model. The proportional hazards assumption was evaluated using plots of Schoenfeld residuals versus log time and found valid, as was the assumption of linearity of continuous variables.

The effect of dapagliflozin compared to placebo on each outcome across UA tertile was examined using Cox regression stratified by diabetes status and adjusted for previous heart failure hospitalization (except for all‐cause death). Likelihood ratio tests are reported to examine for any interaction between UA category and treatment effect.

The treatment effect of dapagliflozin on UA was assessed using a linear regression model adjusted for baseline value and diabetes status. This was repeated for subgroups of interest. The efficacy of dapagliflozin compared with placebo on the primary endpoint over serum UA as a continuous variable was modelled as a fractional polynomial.

All analyses were conducted using Stata version 16.1 (College Station, TX, USA). A p‐value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Of the 4744 randomized patients, 3119 (65.7%) had UA measured at baseline (not all countries participated in the biomarker sub‐study). The mean UA concentration was 6.1 ± 1.7 (median 5.9, IQR 4.9–7.1) mg/dl. Mean UA was 6.2 ± 1.7 mg/dl in men and 5.7 ± 1.6 mg/dl in women (p < 0.001). Overall, 686 participants (14.5%) were prescribed a UA‐lowering agent at baseline and, of these, 531 had UA measured; the mean UA level in these patients was 5.8 ± 1.6 (median 5.7, IQR 4.7–6.7) versus 6.2 ± 1.7 (median 6.0, IQR 5.0–7.1) mg/dl in those not receiving UA‐lowering therapy (p < 0.001). The prevalence of hyperuricaemia (UA >7.0 mg/dl for men and >6.0 mg/dl for women) was 31.6% (29.4% men and 39.2% women). The prevalence of hyperuricaemia was lower in those taking UA‐lowering therapies: 23.9% (32.4% in women and 22.7% in men) vs 33.1% (40.0% in women and 31.0% in men), respectively. Overall, 188 patients (6.0%) had a UA ≥9 mg/dl and 488 participants (10.3%) had a history of gout.

Baseline characteristics according to uric acid

Patient characteristics according to tertile of UA are shown in Table 1 . Patients with higher UA were younger (66.3 ± 10.8 years vs. 68.0 ± 10.2 years) and more often male. There was a higher proportion of Asian and Black participants among those with higher, compared to lower, UA. In general, patients with higher UA had an overall profile suggesting more advanced HFrEF: Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire total symptom score (KCCQ‐TSS) was lower (worse); a history of prior heart failure hospitalization was more common; NT‐proBNP and heart rate were higher; and LVEF, eGFR and systolic blood pressure were lower. Patients with higher UA more commonly suffered from atrial fibrillation and type 2 diabetes mellitus and had a higher body mass index. Loop diuretic treatment was more frequent in patients with higher UA (91.2% vs. 71.5%) (Table 1 ). Patients with a higher UA were also treated with a mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist (MRA) and digoxin more often than those with a lower UA.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics according to uric acid tertile and overall

|

Uric acid |

p‐value |

All patients (n = 3119) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Tertile 1 (n = 1086) |

Tertile 2 (n = 1052) |

Tertile 3 (n = 981) |

|||

| Uric acid, mg/dl | 4.4 ± 0.7 | 6.0 ± 0.4 | 8.1 ± 1.2 | <0.001 | 6.1 ± 1.7 |

| Age, years | 68.0 ± 10.2 | 67.5 ± 10.3 | 66.3 ± 10.8 | <0.001 | 67.3 ± 10.4 |

| Sex, n (%) | <0.001 | ||||

| Female | 310 (28.5) | 217 (20.6) | 166 (16.9) | 693 (22.2) | |

| Male | 776 (71.5) | 835 (79.4) | 815 (83.1) | 2426 (77.8) | |

| Race, n (%) | 0.033 | ||||

| Asian | 187 (17.2) | 205 (19.5) | 184 (18.8) | 576 (18.5) | |

| Black | 20 (1.8) | 26 (2.5) | 41 (4.2) | 87 (2.8) | |

| Other | 5 (0.5) | 3 (0.3) | 4 (0.4) | 12 (0.4) | |

| White | 874 (80.5) | 818 (77.8) | 752 (76.7) | 2444 (78.4) | |

| Region, n (%) | 0.34 | ||||

| Asia/Pacific | 180 (16.6) | 198 (18.8) | 183 (18.7) | 561 (18.0) | |

| Europe | 619 (57.0) | 595 (56.6) | 558 (56.9) | 1772 (56.8) | |

| North America | 181 (16.7) | 172 (16.3) | 171 (17.4) | 524 (16.8) | |

| South America | 106 (9.8) | 87 (8.3) | 69 (7.0) | 262 (8.4) | |

| NYHA functional class, n (%) | 0.16 | ||||

| II | 775 (71.4) | 731 (69.5) | 652 (66.5) | 2158 (69.2) | |

| III | 309 (28.5) | 317 (30.1) | 325 (33.1) | 951 (30.5) | |

| IV | 2 (0.2) | 4 (0.4) | 4 (0.4) | 10 (0.3) | |

| Heart rate, bpm | 69.9 ± 10.8 | 71.1 ± 11.3 | 71.6 ± 11.5 | <0.001 | 70.8 ± 11.2 |

| Systolic blood pressure, mmHg | 123.6 ± 15.4 | 122.4 ± 16.0 | 121.2 ± 15.9 | <0.001 | 122.4 ± 15.8 |

| Left ventricular ejection fraction, % | 31.9 ± 6.2 | 31.2 ± 6.7 | 30.4 ± 7.3 | <0.001 | 31.2 ± 6.8 |

| NT‐proBNP, pg/ml, median (IQR) | 1283.9 (781.2–2252.2) | 1369.6 (839.6–2479.8) | 1747.5 (987.0–3073.9) | <0.001 | 1421.3 (852.0–2564.5) |

| KCCQ‐TSS, median (IQR) | 79.2 (60.4–93.8) | 79.2 (61.5–93.8) | 76.0 (58.3–89.6) | <0.001 | 78.1 (60.4–91.7) |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 27.6 ± 5.6 | 28.7 ± 5.9 | 29.4 ± 6.1 | <0.001 | 28.5 ± 5.9 |

| Ischaemic aetiology of HF, n (%) | 652 (60.0) | 627 (59.6) | 571 (58.2) | 0.008 | 1850 (59.3) |

| Prior HF hospitalization, n (%) | 468 (43.1) | 470 (44.7) | 483 (49.2) | 0.015 | 1421 (45.6) |

| Atrial fibrillation, n (%) | 388 (35.7) | 452 (43.0) | 438 (44.6) | <0.001 | 1278 (41.0) |

| Type 2 diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 411 (37.8) | 436 (41.4) | 455 (46.4) | <0.001 | 1302 (41.7) |

| eGFR, ml/min/1.73 m2 | 70.6 ± 18.7 | 65.6 ± 18.0 | 58.2 ± 17.4 | <0.001 | 65.0 ± 18.8 |

| eGFR, mL/min/1.73 m2, n (%) | <0.001 | ||||

| <60 | 301 (27.8) | 412 (39.2) | 558 (56.9) | 1271 (40.8) | |

| ≥60 | 783 (72.2) | 640 (60.8) | 423 (43.1) | 1846 (59.2) | |

| Implantable cardioverter defibrillator, n (%) | 342 (31.5) | 340 (32.3) | 299 (30.5) | 0.13 | 981 (31.5) |

| Cardiac resynchronization therapy, n (%) | 103 (9.5) | 78 (7.4) | 81 (8.3) | 0.0002 | 262 (8.4) |

| Medical therapy, n (%) | |||||

| Loop diuretic | 776 (71.5) | 873(83.0) | 895(91.2) | <0.001 | 2544 (81.6) |

| Thiazide diuretic | 90(8.3) | 88(8.4) | 105(10.5) | <0.001 | 283(9.1) |

| Other diuretic (non‐MRA) | 12(1.1) | 16(1.5) | 9(0.9) | 0.06 | 37(1.2) |

| ACE inhibitor | 608 (56.0) | 613 (58.3) | 550 (56.1) | 0.03 | 1771 (56.8) |

| ARB | 295 (27.2) | 261 (24.8) | 239 (24.4) | <0.001 | 795 (25.5) |

| Sacubitril/valsartan | 132 (12.2) | 134 (12.7) | 117 (11.9) | 0.02 | 383 (12.3) |

| Beta‐blocker | 1038 (95.6) | 1008 (95.8) | 942 (96.0) | 0.36 | 2988 (95.8) |

| MRA | 746 (68.7) | 744 (70.7) | 731 (74.5) | <0.001 | 2221 (71.2) |

| Digoxin | 127 (11.7) | 149 (14.2) | 204 (20.8) | <0.001 | 480 (15.4) |

Data are means ± standard deviation, unless otherwise indicated. Percentages may not total 100 due to rounding. To convert NT‐proBNP from pg/ml to ng/L multiply by 1.

ACE, angiotensin‐converting enzyme; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; HF heart failure; IQR interquartile range; KCCQ‐TSS, Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire total symptom score; MRA, mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist; NT‐proBNP, N‐terminal pro‐B‐type natriuretic peptide; NYHA, New York Heart Association.

Clinical outcomes according to uric acid

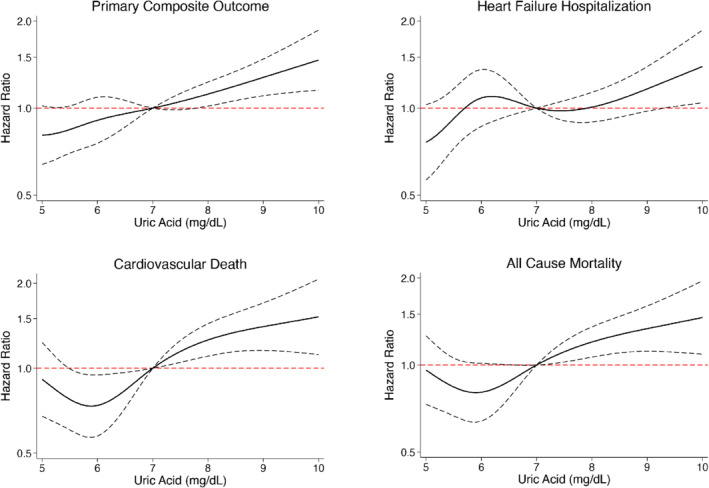

The rates of the pre‐specified clinical outcomes according to baseline UA tertile are shown in Table 2 and online supplementary Figure S1 and according to UA displayed as a continuous variable in Figure 1 . The primary composite outcome occurred more frequently in patients with higher UA although, after adjustment for other prognostic variables (including NT‐proBNP, diuretic dose and eGFR), the greater risk was only apparent in those in the highest tertile (6.8–13.7 mg/dl), using tertile 1 as reference. Spline analysis suggested a linear increase in risk above a serum concentration of around 7.09 mg/dl. The unadjusted HR per unit increase in UA above 7 mg/dl was 1.35 to 1.39 for the endpoints of interest and the adjusted HRs ranged from 1.13 to 1.18 (Figure 1 and online supplementary Table S1 ). eGFR slopes according to baseline UA tertile are shown in online supplementary Figure S2 ; eGFR slope did not vary by UA tertile.

Table 2.

Risk of various endpoints according to uric acid levels at randomization

| No. events | Crude rate per 100 py | Unadjusted HR (95% CI) | p‐value | Adjusted HR (95% CI) a | p‐value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cardiovascular death or worsening HF event b | ||||||

| Uric acid tertile | ||||||

| T1: <5.4 mg/dl | 150 | 9.7 (8.2–11.4) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | ||

| T2: 5.4–6.7 mg/dl | 172 | 11.4 (9.7–13.2) | 1.15 (0.93–1.44) | 0.2 | 1.03 (0.82–1.29) | 0.83 |

| T3: 6.8–13.7 mg/dl | 250 | 18.9 (16.7–21.4) | 1.87 (1.52–2.29) | <0.0001 | 1.32 (1.06–1.66) | 0.01 |

| UA per 1 mg/dl unit increase | 1.19 (1.14–1.25) | <0.001 | 1.08 (1.03–1.14) | 0.0017 | ||

| Cardiovascular death | ||||||

| Uric acid tertile | ||||||

| T1: <5.4 mg/dl | 95 | 5.9 (4.8–7.2) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | ||

| T2: 5.4–6.7 mg/dl | 83 | 5.2 (4.2–6.4) | 0.86 (0.64–1.16) | 0.33 | 0.77 (0.57–1.05) | 0.10 |

| T3: 6.8–13.7 mg/dl | 146 | 10.3 (8.7–12.1) | 1.69 (1.30–2.19) | <0.001 | 1.18 (0.89–1.58) | 0.25 |

| UA per 1 mg/dl unit increase | 1.18 (1.12–1.26) | <0.001 | 1.06 (0.99–1.14) | 0.07 | ||

| HF hospitalization | ||||||

| Uric acid tertile | ||||||

| T1: <5.4 mg/dl | 89 | 5.8 (4.7–7.1) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | ||

| T2: 5.4–6.7 mg/dl | 119 | 7.9 (6.6–9.4) | 1.34 (1.02–1.77) | 0.04 | 1.17 (0.88–1.55) | 0.29 |

| T3: 6.8–13.7 mg/dl | 158 | 12.0 (10.2–14.0) | 1.96 (1.51–2.54) | <0.001 | 1.29 (0.97–1.72) | 0.08 |

| UA per 1 mg/dl unit increase | 1.20 (1.14–1.27) | <0.001 | 1.07 (1.00–1.14) | 0.04 | ||

| All‐cause mortality | ||||||

| Uric acid tertile | ||||||

| T1: <5.4 mg/dl | 122 | 7.6 (6.3–9.1) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | ||

| T2: 5.4–6.7 mg/dl | 102 | 6.4 (5.3–7.7) | 0.83 (0.64–1.08) | 0.26 | 0.76 (0.58–0.99) | 0.05 |

| T3: 6.8–13.7 mg/dl | 166 | 11.7 (10.0–13.6) | 1.5(1.19–1.89) | 0.0007 | 1.09 (0.84–1.42) | 0.51 |

| UA per 1 mg/dl unit increase | 1.14 (1.08–1.21) | <0.001 | 1.03 (0.97–1.1) | 0.28 | ||

CI, confidence interval; HF, heart failure; HR, hazard ratio; py, person‐years; T, tertile.

Stratified by diabetes status and adjusted for the following baseline variables: history of HF hospitalization, treatment group assignment, age, sex, pulse, systolic blood pressure, body mass index, atrial fibrillation, diabetes, aetiology of HF, left ventricular ejection fraction, New York Heart Association functional classification, N‐terminal pro‐B‐type natriuretic peptide (log), estimated glomerular filtration rate, non‐loop diuretic use, loop diuretic use dose, and use of angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitor, angiotensin receptor blocker or angiotensin receptor–neprilysin inhibitor.

Worsening HF event includes unplanned HF hospitalization or urgent visit for worsening HF requiring intravenous diuretic therapy.

Figure 1.

Association between baseline uric acid and the risk of the primary composite outcome (worsening heart failure event or cardiovascular death), cardiovascular death, heart failure hospitalization and all‐cause mortality (restricted cubic spline analysis). Model adjusted for randomized treatment (dapagliflozin), age, sex, pulse, systolic blood pressure, body mass index, history of heart failure hospitalization, atrial fibrillation, diabetes status, aetiology of heart failure, left ventricular ejection fraction, New York Heart Association functional classification, N‐terminal pro‐B‐type natriuretic peptide (log), estimated glomerular filtration rate, non‐loop diuretic use, loop diuretic use dose, and use of an angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitor, angiotensin receptor blocker or angiotensin receptor–neprilysin inhibitor.

Effect of dapagliflozin on outcomes according to uric acid

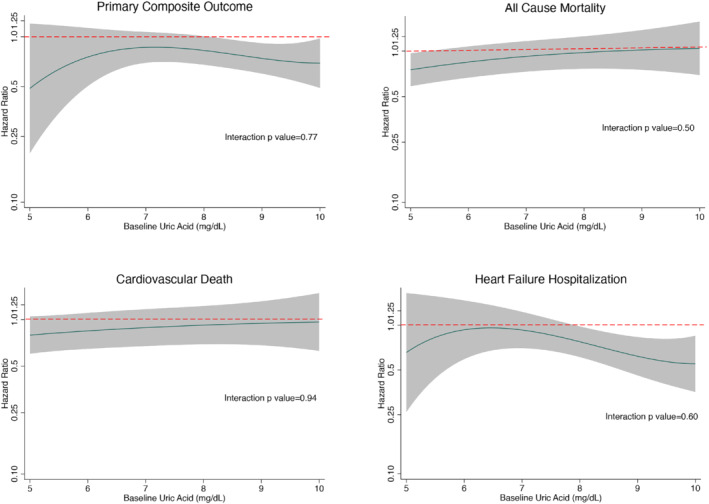

The benefit of dapagliflozin compared with placebo was consistent for all pre‐specified outcomes across the range of UA, whether UA was examined as a categorical (tertile) or continuous variable (Table 3 and Figure 2 ).

Table 3.

Effect of randomized treatment on outcomes according to uric acid tertile

| Tertile 1 (n = 1086) | Tertile 2 (n = 1052) | Tertile 3 (n = 981) | p for interaction | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dapagliflozin (n = 546) | Placebo (n = 540) | Dapagliflozin (n = 545) | Placebo (n = 507) | Dapagliflozin (n = 491) | Placebo (n = 490) | ||

| Cardiovascular death or worsening HF event | |||||||

| n (%) | 65 (11.9) | 85 (15.7) | 90 (16.5) | 82 (16.1) | 105 (21.4) | 145 (29.6) | |

| Rate (95% CI) | 8.2 (6.4–10.5) | 11.3 (9.1–13.9) | 11.3 (9.2–13.9) | 11.5 (9.2–14.2) | 15.7 (13.0–19.0) | 22.3 (18.9–26.2) | |

| Hazard ratio a (95% CI) | 0.71(0.52–0.99) | 1.00 (0.74–1.35) | 0.70 (0.55–0.90) | 0.16 | |||

| Cardiovascular death | |||||||

| No (%) | 39 (7.14) | 56 (10.37) | 41 (7.52) | 42 (8.28) | 71 (14.46) | 75 (15.31) | |

| Rate (95% CI) | 4.8 (3.5–6.5) | 7.1 (5.5–9.2) | 4.9 (3.6–6.7) | 5.5 (4.1–7.5) | 10.1 (8.0–12.8) | 10.4 (8.3,13.1) | |

| Hazard ratio a (95% CI) | 0.65 (0.43–0.98) | 0.90 (0.58–1.38) | 0.96 (0.69–1.33) | 0.32 | |||

| HF hospitalization | |||||||

| No (%) | 42 (7.7) | 47 (8.7) | 60 (11.0) | 59 (11.6) | 60 (12.2) | 98 (20.0) | |

| Rate (95% CI) | 5.3 (3.9–7.2) | 6.2 (4.7–8.3) | 7.5 (5.8–9.7) | 8.2 (6.4–10.6) | 9.0 (6.9–11.6) | 15.0 (12.3–18.3) | |

| Hazard ratio a (95% CI) | 0.84 (0.56–1.28) | 0.92 (0.64–1.32) | 0.59 (0.43–0.82) | 0.16 | |||

| All‐cause mortality | |||||||

| No (%) | 49 (9.0) | 73 (13.5) | 51 (9.4) | 51 (10.1) | 82 (16.7) | 84 (17.1) | |

| Rate (95% CI) | 6.0 (4.5–7.9) | 9.3 (7.4–11.6) | 6.1 (4.6–8.0) | 6.7 (5.1–8.8) | 11.7 (9.4–14.5) | 11.7 (9.4–14.5) | |

| Hazard ratio a (95% CI) | 0.63 (0.44–0.90) | 0.91 (0.62–1.35) | 1.00 (0.73–1.35) | 0.14 | |||

CI, confidence interval; HF, heart failure.

Hazard ratio for treatment adjusted for history of HF hospitalization (apart from all‐cause death) and stratified by diabetes status.

Figure 2.

Effect of dapagliflozin compared with placebo on the primary composite outcome, cardiovascular death, heart failure hospitalization and all‐cause mortality according to baseline uric acid level (fractional polynomial analysis), displayed as a hazard ratio in the solid black line with the shaded area representing 95% confidence intervals. The interrupted red line represents the line of null effect (i.e. hazard ratio of 1.00), below which the estimates favour dapagliflozin. Treatment effect for each outcome (except all‐cause mortality) adjusted for history of heart failure hospitalization and stratified by diabetes status.

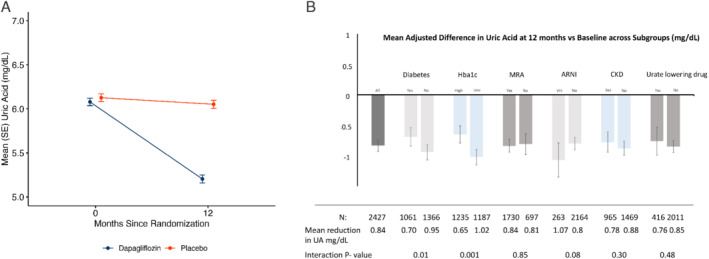

Effect of dapagliflozin on uric acid level

At 52 weeks after randomization, the placebo‐corrected reduction in UA from baseline was 0.84 mg/dl (95% CI −0.93 to −0.74; p < 0.001) (Figure 3A ). The reduction according to baseline UA tertile was: T1 (UA <5.4 mg/dl) −0.75 (−0.89 to −0.61) mg/dl; T2 (UA 5.4–6.7 mg/dl); −0.83 (−0.98 to −0.67) mg/dl; T3 (UA >5.8 mg/dl) −0.94 (−1.14 to −0.74) mg/dl (all changes p < 0.001; no interaction between effect of dapagliflozin and UA tertile). A ‘waterfall plot’ of change in UA is shown in online supplementary Figure S3 .

Figure 3.

(A) Mean (and standard error of the mean, SE) uric acid (UA) by randomized treatment at 0 and 52 weeks. (B) Effect of treatment (dapagliflozin vs. placebo) on UA across subgroups of interest (figure panel shows change in UA from baseline). ARNI, angiotensin receptor–neprilysin inhibitor; CKD, chronic kidney disease; Hba1c, glycated haemoglobin; MRA, mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist. High/low Hba1c defined as levels above/below median value of 6.1%. Dispersion lines represent 95% confidence intervals.

The reduction in UA was consistent in most subgroups of interest, including patients treated with an angiotensin receptor blocker or sacubitril/valsartan at baseline and patients treated with other uricosuric drugs and drugs inhibiting UA production (Figure 3B ). However, there was evidence of a greater reduction in UA in patients without diabetes and lower glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c).

A total of 2500 patients had UA levels checked at 12‐month follow‐up. The proportion of those achieving a level of <6.0 mg/dl at 12 months was 72.7% (n = 930/1278) in the dapagliflozin group and 51.2% in the placebo group (n = 626/1222) (p < 0.001).

Use of uric acid‐lowering agents before and after randomization

At baseline, 664 patients (14.0%) were taking a treatment inhibiting UA production (allopurinol, febuxostat, or topiroxostat) and 24 participants (0.5%) were treated with a drug increasing UA excretion (benzbromarone, probenecid, or sulfinpyrazone). A UA‐lowering agent was initiated in 104 (4.4%) patients after randomization in the placebo group, as compared to 51 (2.1%) among those assigned to dapagliflozin (between‐group p <0.001). The number of patients who had a serious adverse event related to gout during follow‐up was 4/2368 (0.17%) in the placebo group versus 2/2368 (0.08%) among those receiving dapagliflozin (non‐serious adverse events related to gout were not collected).

Use of other drugs after randomization

No patient in either group was started on colchicine after randomization. During follow‐up, patients in the dapagliflozin group were less likely to have an increase in diuretic dose (odds ratio 0.74, 95% CI 0.57–0.96) and more likely to have a reduction in diuretic dose (odds ratio 1.6, 95% CI 1.21–2.11).

Discussion

Many patients in DAPA‐HF had an elevated UA and higher UA was associated with a greater risk of the primary outcome of worsening heart failure or cardiovascular death in this contemporary HFrEF cohort receiving excellent conventional therapy. Spline analysis indicated a linear risk above a UA concentration of approximately 7.09 mg/dl and the risk of the primary endpoint increased by 9% for each 1 mg/dl increase in UA (cardiovascular death increased by 6% for each 1 mg/dl). The elevation of risk related to UA remained even after adjustment for other prognostic variables including natriuretic peptides. The benefits of dapagliflozin on the trial primary and secondary outcomes were consistent across the range of UA concentrations at baseline. Dapagliflozin lowered UA and conventional UA‐lowering agents were initiated significantly less frequently in patients assigned to dapagliflozin compared with placebo (Graphical Abstract).

The finding that dapagliflozin lowered UA in patients with chronic HFrEF treated with contemporary medications is important because hyperuricaemia is common in this population. Using recommended sex‐specific cut‐offs of 6.0 mg/dl (∼360 µmol/L) in females and 7.0 mg/dl (∼420 µmol/L) in males, 26 we found that 29.4% of men and 39.2% of women had hyperuricaemia, considerably higher than the 5%–20% prevalence reported in the general population 27 but consistent with other studies in heart failure. 10 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 31

The independent prognostic importance of UA continues to be debated. For example, while the GISSI‐HF investigators reported an association between death from cardiovascular causes, death from any cause and hospitalization for heart failure, their multivariate analysis did not include natriuretic peptides. 9 More recently, UA was found to remain predictive of outcomes in PARADIGM‐HF, even after adjustment for NT‐proBNP level 11 and our data support this observation.

Although higher UA is related to worse outcomes, the explanation for this association is not clear and a cause‐and‐effect relationship has not been established. Specifically, several randomized controlled trials have failed to demonstrate a benefit of the non‐selective xanthine oxidase inhibitor, allopurinol and its metabolite oxypurinol, in patients with heart failure, although none of these was a large mortality/morbidity trial. 14 , 15 , 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 There are no completed trials with the novel xanthine oxidase inhibitors, febuxostat and topiroxostat, in patients with heart failure. 36 , 37

While not shown to improve heart failure outcomes, lowering UA is still needed in some patients, primarily to reduce the risk of gout or recurrence of gout. Overall, 10.3% of our patients had a history of gout, 14.5% were prescribed a UA‐lowering treatment at baseline, and 6.0% had a UA ≥9 mg/dl, the suggested threshold for initiating prophylactic UA‐lowering therapy. 26 Intolerance of conventional UA‐lowering treatments is common, particularly in some Asian ethnic groups, and serious adverse effects may occur, including hypersensitivity reactions (e.g. Stevens–Johnson syndrome with allopurinol). 38 Drug interactions are also common (including with furosemide and angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitors). 39 , 40 Consequently, avoidance of the use of these drugs is preferable. Therefore the finding that dapagliflozin reduced UA concentration is potentially clinically relevant. Of interest, the reduction in UA at 52 weeks in DAPA‐HF was 0.84 mg/dl (95% CI −0.93 to −0.74), which was more than twice the mean placebo‐corrected reduction in serum UA of 0.37 (95% CI 0.42−0.31) mg/dl with empagliflozin at 52 weeks in EMPA‐REG OUTCOME. 41 Although it is difficult to compare across trials and in different medical conditions, a recent systematic review and network meta‐analysis has suggested there may be differences in the size of UA reduction with different SGLT2 inhibitors, at least in people with type 2 diabetes. 42 Although the average reduction in UA was still modest in DAPA‐HF, it did result in more patients achieving an ideal UA level at 12 months (<6.0 mg/dl) compared with placebo (72.7% vs. 51.2%) and the rate of initiation of a new UA‐lowering agent was halved over the median follow‐up of 18.2 months (2.1% vs. 4.4%; p <0.001). 26 We did not have data on gouty flares, although a reduction in these was demonstrated in the CANVAS trials (from 2.6 patients with an event per 1000 person‐years in the placebo group to 2.0 per 1000 person‐years in the canagliflozin group; HR 0.64, 95% CI 0.41–0.99; p = 0.046). 43

Although the UA‐lowering action of dapagliflozin was both statistically and clinically significant, the size of the reduction was modest and around a half to a third of that observed with xanthine oxidase inhibitors, albeit in patients with higher baseline UA concentrations. 44 Importantly, however, the UA‐lowering action of dapagliflozin was similar in patients treated and not treated with a conventional UA‐lowering agent that is, appears to be mechanistically distinct.

Sodium–glucose cotransporter inhibitors are thought to reduce UA by increasing the rate of urinary UA excretion. Non‐reabsorbed glucose is thought to compete for the facilitated glucose transporter member 9 isoform 2 in the proximal renal tubule, a major regulator of urate homeostasis. 22 This may explain why there was an interaction between baseline diabetes status (and HbA1c level) and the UA‐lowering efficacy of dapagliflozin, whereby the reduction in UA was greater in patients without type 2 diabetes (and in those with a lower HbA1c).

This ancillary UA‐lowering property of SGLT2 inhibitors has also been shown for some other treatments for heart failure, notably losartan and sacubitril/valsartan. 11 , 45 Recently, vericiguat, a stimulator of soluble guanylate cyclase, was also demonstrated to reduce UA with a placebo corrected reduction of 10.0% (95% CI 3%–16%) with a dose of 10 mg compared to the 13.6% (95% CI 12.1%–15.2%) reduction demonstrated in DAPA‐HF. 46

The benefits of dapagliflozin on clinical outcomes were not modified by baseline UA, with consistent reductions in the primary endpoint, its components, heart failure hospitalization and all‐cause death across the range of UA measured at baseline. The results were consistent whether the outcomes were analysed by UA tertile or using UA as a continuous variable.

The mechanism of the UA‐lowering effect of SGLT2 inhibitors in heart failure is unknown. Broadly, this action could reflect increased excretion or reduced production of UA. We did not measure urinary UA levels and, clearly, that would be of interest. We know of no evidence that SGLT2 inhibitors reduce xanthine oxidase activity and we found that dapagliflozin reduced UA levels as much in patients taking conventional UA‐lowering therapy as in those not. However, it would be of interest to examine the effect of SGLT2 inhibitors on plasma xanthine oxidase activity. There has also been speculation that SGLT2 inhibitors might act directly or indirectly on urate transporters in the kidney tubules, and this could be probed by studies combining an SGLT2 inhibitor with other drugs such as verinurad, which is a specific inhibitor of urate transporter 1 (URAT1).

Our study has several limitations. This analysis was not pre‐specified and retrospective analyses of this type may be subject to residual/unmeasured confounding. Patients were enrolled in a clinical trial with specific entry criteria, including the exclusion of individuals with an eGFR <30 ml/min/1.73 m2. We had only a single repeat measurement of UA at 12 months.

Conclusions

Uric acid was an independent predictor of worse outcomes in DAPA‐HF even after multivariable adjustment including natriuretic peptides. Compared with placebo, dapagliflozin reduced UA and improved outcomes irrespective of UA concentration in patients with HFrEF.

Supporting information

Figure S1. Cumulative incidence of the primary composite endpoint, cardiovascular death, heart failure hospitalization and all‐cause mortality according to baseline uric acid tertile.

Figure S2. Change in estimated glomerular filtration rate from baseline with slope analysis over days 14–720, by treatment group.

Figure S3. ‘Waterfall plot’ of change in uric acid between baseline and 52 weeks in each treatment group.

Table S1. Risk of various endpoints according to uric acid levels at randomization, per 1 mg/dl unit increase above 7 mg/dl.

Acknowledgments

DAPA‐HF was funded by AstraZeneca. JJVM is supported by a British Heart Foundation Centre of Research Excellence Grant RE/18/6/34217.

Conflict of interest: P.W. reports grant income from Roche Diagnostics, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, and Novartis outside the submitted work. K.F.D.'s employer, the University of Glasgow, has been remunerated by AstraZeneca for working on the DAPA‐HF trial; K.F.D reports personal fees from AstraZeneca and Eli Lilly outside the submitted work. D.A.M. reports grants to the TIMI Study Group from Abbott Laboratories, Amgen, Anthos Therapeutics, AstraZeneca, BRAHMS, Eisai, GlaxoSmithKline, Medicines Co., Merck, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche Diagnostics, Quark, Siemens, and Takeda, and consultant fees from InCardia, Merck & Co, Novartis, and Roche Diagnostics. P.S.J.'s employer, the University of Glasgow, has been remunerated by AstraZeneca for working on the DAPA‐HF trial and the DELIVER trial; P.S.J. reports speakers and advisory board fees from AstraZeneca, speakers and advisory board fees from Novartis, and advisory board fees and grants from Boehringer Ingelheim. R.A.d.B. has received research grants and/or fees to his institution (UMCG) from AstraZeneca, Abbott, Boehringer Ingelheim, Cardior Pharmaceuticals Gmbh, Ionis Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Novo Nordisk, and Roche outside the submitted work, and speaker fees from Abbott, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Novartis, and Roche, outside the submitted work. E.O'M. reports serving as a consultant and speaker for AstraZeneca, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim and Novartis; steering committee and national lead investigator contracts between her institution (Montreal Heart Institute Research Center) and American Regent, AstraZeneca, Cytokinetics, Merck and Novartis; clinical trial participation with Amgen, Abbott, American Regent, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Cytokinetics, Eidos, Novartis, Merck, Pfizer, and Sanofi. S.E.I. reports membership on scientific/research advisory boards for Boehringer Ingelheim, AstraZeneca, Intarcia, Lexicon, Janssen, Sanofi, Merck & Co. and Novo Nordisk, has received research supplies to Yale University from Takeda, and has participated in medical educational projects, for which unrestricted funding from Boehringer Ingelheim, Eli Lilly, and Merck & Co. was received by Yale University. L.K. has received speakers honoraria from Novartis, AstraZeneca, Novo, and Boehringer Ingelheim. M.N.K. has received grant and research support from AstraZeneca, grant and honoraria from Boehringer Ingelheim, and honoraria from Sanofi, Amgen, Novo Nordisk, Merck (Diabetes), Janssen, Bayer, Novartis, Eli Lilly, and Vifor Pharma. N.S. has consulted for Amgen, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Eli Lilly, Merck Sharp and Dohme, Novo Nordisk, Novartis, Sanofi, and Pfizer; and has received grant support from Boehringer Ingelheim. M.S.S. reports research grant support through Brigham and Women's Hospital from Amgen, Anthos Therapeutics, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Daiichi Sankyo, Eisai, Intarcia, Medicines Company, MedImmune, Merck, Novartis, Pfizer, Quark Pharmaceuticals, and Takeda, and consulting for Althera, Amgen, Anthos Therapeutics, AstraZeneca, Bristol‐Myers Squibb, CVS Caremark, DalCor, Dr. Reddy's Laboratories, Dyrnamix, Esperion, IFM Therapeutics, Intarcia, Janssen Research and Development, Medicines Company, MedImmune, Merck, and Novartis. M.S.S. and D.A.M. are members of the TIMI Study Group, which has received institutional research grant support through Brigham and Women's Hospital from Abbott, Amgen, Anthos Therapeutics, ARCA Biopharma, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Daiichi‐Sankyo, Eisai, Intarcia, Ionis Pharmaceuticals, MedImmune, Merck, Novartis, Pfizer, Quark Pharmaceuticals, Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Roche, Siemens Healthcare Diagnostics, The Medicines Company, and Zora Biosciences. J.J.V.McM. is supported by a British Heart Foundation Centre of Research Excellence Grant RE/18/6/34217; his employer, Glasgow University, has received payment for his work on clinical trials, consulting, and other activities from Alnylam, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Bristol Myers Squibb, Cardurion, Cytokinetics, GlaxoSmithKline, Novartis, Pfizer, Theracos; and he has received personal lecture fees from the Corpus, Abbott, Hickma, Sun Pharmaceuticals, and Medscape. A.H., A.M.L., D.L., and M. Sjöstrand are employees of AstraZeneca. K.McD. has nothing to disclose. F.A.M. reports personal fees from AstraZeneca. P.P. reports personal fees for consultancy and speakers bureau from AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Vifor Pharma, Servier, Bayer, Bristol Myers Squibb, Respocardia, Berlin‐Chemie, Cibiem, Novartis and RenalGuard; other support for participation in clinical trials from Boehringer Ingelheim, Amgen, Vifor Pharma, Bayer, Bristol Myers Squibb, Cibiem, Novartis and RenalGuard; and research grants to his institution from Vifor Pharma. S.D.S. received payment to his institution for participation in DAPA‐HF; received grants to his institution from Actelion, Alnylam, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bellerophon, Bayer, Bristol Myers Squibb, Celladon, Cytokinetics, Eidos, Gilead, GlaxoSmithKline, IONIS, Lilly, Mesoblast, MyoKardia, National Institutes of Health National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, Neurotronik, Novartis, NovoNordisk, Respicardia, Sanofi Pasteur, Theracos, and US2.AI; received fees for consultancy from Abbott, Action, Akros, Alnylam, Amgen, Arena, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Boeringer‐Ingelheim, Bristol Myers Squibb, Cardior, Cardurion, Corvia, Cytokinetics, Daiichi‐Sankyo, GlaxoSmithKline, Lilly, Merck, Myokardia, Novartis, Roche, Theracos, Quantum Genomics, Cardurion, Janssen, Cardiac Dimensions, Tenaya, Sanofi Pasteur, Dinaqor, Tremeau, CellProThera, Moderna, American Regent, and Sarepta; and received honoraria for lectures from Novartis and AstraZeneca.

References

- 1. Borghi C, Tykarski A, Widecka K, Filipiak KJ, Domienik‐Karłowicz J, Kostka‐Jeziorny K, et al. Expert consensus for the diagnosis and treatment of patient with hyperuricemia and high cardiovascular risk. Cardiol J. 2018;25:545–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Saito Y, Tanaka A, Node K, Kobayashi Y. Uric acid and cardiovascular disease: a clinical review. J Cardiol. 2021;78:51–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Yu W, Cheng JD. Uric acid and cardiovascular disease: an update from molecular mechanism to clinical perspective. Front Pharmacol. 2020;11:582680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Borghi C, Palazzuoli A, Landolfo M, Cosentino E. Hyperuricemia: a novel old disorder – relationship and potential mechanisms in heart failure. Heart Fail Rev. 2020;25:43–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Reyes AJ. Cardiovascular drugs and serum uric acid. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther. 2003;17:397–414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Landmesser U, Spiekermann S, Dikalov S, Tatge H, Wilke R, Kohler C, et al. Vascular oxidative stress and endothelial dysfunction in patients with chronic heart failure: role of xanthine‐oxidase and extracellular superoxide dismutase. Circulation. 2002;106:3073–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Otaki Y, Watanabe T, Kinoshita D, Yokoyama M, Takahashi T, Toshima T, et al. Association of plasma xanthine oxidoreductase activity with severity and clinical outcome in patients with chronic heart failure. Int J Cardiol. 2017;228:151–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ambrosio G, Leiro MGC, Lund LH, Coiro S, Cardona A, Filippatos G, et al. Serum uric acid and outcomes in patients with chronic heart failure through the whole spectrum of ejection fraction phenotypes: analysis of the ESC‐EORP Heart Failure Long‐Term (HF LT) Registry. Eur J Intern Med. 2021;89:65–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Mantovani A, Targher G, Temporelli PL, Lucci D, Gonzini L, Nicolosi GL, et al.; GISSI‐HF Investigators . Prognostic impact of elevated serum uric acid levels on long‐term outcomes in patients with chronic heart failure: a post‐hoc analysis of the GISSI‐HF (Gruppo Italiano per lo Studio della Sopravvivenza nella Insufficienza Cardiaca‐Heart Failure) trial. Metabolism. 2018;83:205–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Vaduganathan M, Greene SJ, Ambrosy AP, Mentz RJ, Subacius HP, Chioncel O, et al.; EVEREST Trial Investigators . Relation of serum uric acid levels and outcomes among patients hospitalized for worsening heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (from the Efficacy of Vasopressin Antagonism in Heart Failure Outcome Study with Tolvaptan trial). Am J Cardiol. 2014;114:1713–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Mogensen UM, Køber L, Jhund PS, Desai AS, Senni M, Kristensen SL, et al.; PARADIGM‐HF Investigators and Committees . Sacubitril/valsartan reduces serum uric acid concentration, an independent predictor of adverse outcomes in PARADIGM‐HF. Eur J Heart Fail. 2018;20:514–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Mouradjian MT, Plazak ME, Gale SE, Noel ZR, Watson K, Devabhakthuni S. Pharmacologic management of gout in patients with cardiovascular disease and heart failure. Am J Cardiovasc Drugs. 2020;20:431–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Spieker LE, Ruschitzka FT, Lüscher TF, Noll G. The management of hyperuricemia and gout in patients with heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail. 2002;4:403–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hare JM, Mangal B, Brown J, Fisher C, Freudenberger R, Colucci WS, et al.; OPT‐CHF Investigators . Impact of oxypurinol in patients with symptomatic heart failure. Results of the OPT‐CHF study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;51:2301–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Givertz MM, Anstrom KJ, Redfield MM, Deswal A, Haddad H, Butler J, et al.; NHLBI Heart Failure Clinical Research Network . Effects of xanthine oxidase inhibition in hyperuricemic heart failure patients: the Xanthine Oxidase Inhibition for Hyperuricemic Heart Failure Patients (EXACT‐HF) study. Circulation. 2015;131:1763–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Selvaraj S, Claggett BL, Pfeffer MA, Desai AS, Mc Causland FR, McGrath MM, et al. Serum uric acid, influence of sacubitril‐valsartan, and cardiovascular outcomes in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: paragon‐hf . Eur J Heart Fail. 2020;22:2093–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. McMurray JJV, Solomon SD, Inzucchi SE, Køber L, Kosiborod MN, Martinez FA, et al.; DAPA‐HF Trial Committees and Investigators . Dapagliflozin in patients with heart failure and reduced ejection fraction. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:1995–2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Packer M, Anker SD, Butler J, Filippatos G, Pocock SJ, Carson P, et al.; EMPEROR‐Reduced Trial Investigators . Cardiovascular and renal outcomes with Empagliflozin in heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:1413–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bhatt DL, Szarek M, Steg PG, Cannon CP, Leiter LA, McGuire DK, et al.; SOLOIST‐WHF Trial Investigators . Sotagliflozin in patients with diabetes and recent worsening heart failure. N Engl J Med 2021;384:117–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Zhao Y, Xu L, Tian D, Xia P, Zheng H, Wang L, et al. Effects of sodium‐glucose co‐transporter 2 (sglt2 ) inhibitors on serum uric acid level: a meta‐analysis of randomized controlled trials. Diabetes Obes Metab 2018;20:458–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Novikov A, Fu Y, Huang W, Freeman B, Patel R, van Ginkel C, et al. SGLT2 inhibition and renal urate excretion: role of luminal glucose, GLUT9, and URAT1. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 2019;316:F173–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Chino Y, Samukawa Y, Sakai S, Nakai Y, Yamaguchi J, Nakanishi T, et al. SGLT2 inhibitor lowers serum uric acid through alteration of uric acid transport activity in renal tubule by increased glycosuria. Biopharm Drug Dispos. 2014;35:391–404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Bailey CJ. Uric acid and the cardio‐renal effects of SGLT2 inhibitors. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2019;21:1291–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. McMurray JJV, DeMets DL, Inzucchi SE, Køber L, Kosiborod MN, Langkilde AM, et al.; DAPA‐HF Committees and Investigators . A trial to evaluate the effect of the sodium–glucose co‐transporter 2 inhibitor dapagliflozin on morbidity and mortality in patients with heart failure and reduced left ventricular ejection fraction (DAPA‐HF). Eur J Heart Fail 2019;21:665–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. McMurray JJV, DeMets DL, Inzucchi SE, Køber L, Kosiborod MN, Langkilde AM, et al.; DAPA‐HF Committees and Investigators . The Dapagliflozin and Prevention of Adverse‐outcomes in Heart Failure (DAPA‐HF) trial: baseline characteristics. Eur J Heart Fail. 2019;21:1402–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Li Q, Li X, Wang J, Liu H, Kwong JSW, Chen H, et al. Diagnosis and treatment for hyperuricemia and gout: a systematic review of clinical practice guidelines and consensus statements. BMJ Open. 2019;9:e026677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Zhu Y, Pandya BJ, Choi HK. Prevalence of gout and hyperuricemia in the US general population: the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2007‐2008: prevalence of gout and hyperuricemia in the US. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63:3136–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hamaguchi S, Furumoto T, Tsuchihashi‐Makaya M, Goto K, Goto D, Yokota T, et al. Hyperuricemia predicts adverse outcomes in patients with heart failure. Int J Cardiol. 2011;151:143–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Baldasseroni S, Urso R, Maggioni AP, Orso F, Fabbri G, Marchionni N, et al.; IN‐CHF Investigators . Prognostic significance of serum uric acid in outpatients with chronic heart failure is complex and related to body mass index: data from the IN‐CHF Registry. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2012;22:442–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Gotsman I, Keren A, Lotan C, Zwas DR. Changes in uric acid levels and allopurinol use in chronic heart failure: association with improved survival. J Card Fail. 2012;18:694–701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Manzano L, Babalis D, Roughton M, Shibata M, Anker SD, Ghio S, et al.; SENIORS Investigators . Predictors of clinical outcomes in elderly patients with heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail. 2011;13:528–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Greig D, Alcaino H, Castro PF, Garcia L, Verdejo HE, Navarro M, et al. Xanthine‐oxidase inhibitors and statins in chronic heart failure: effects on vascular and functional parameters. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2011;30:408–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Cingolani HE, Plastino JA, Escudero EM, Mangal B, Brown J, Pérez NG. The effect of xanthine oxidase inhibition upon ejection fraction in heart failure patients: La Plata study. J Card Fail. 2006;12:491–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Gavin AD. Allopurinol reduces B‐type natriuretic peptide concentrations and haemoglobin but does not alter exercise capacity in chronic heart failure. Heart. 2005;91:749–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Maurice C, Nasr G. Allopurinol and global left myocardial function in heart failure patients. J Cardiovasc Dis Res. 2010;1:191–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Yokota T, Fukushima A, Kinugawa S, Okumura T, Murohara T, Tsutsui H. Randomized trial of effect of urate‐lowering agent febuxostat in chronic heart failure patients with hyperuricemia (LEAF‐CHF): study design. Int Heart J. 2018;59:976–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Sakuma M, Toyoda S, Arikawa T, Koyabu Y, Kato T, Adachi T, et al.; Excited UA study Investigators . The effects of xanthine oxidase inhibitor in patients with chronic heart failure complicated with hyperuricemia: a prospective randomized controlled clinical trial of topiroxostat vs allopurinol – study protocol. Clin Exp Nephrol. 2018;22:1379–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Yu KH, Lai JH, Hsu PN, Chen DY, Chen CJ, Lin HY. Safety and efficacy of oral febuxostat for treatment of HLA‐B*5801‐negative gout: a randomized, open‐label, multicentre, allopurinol‐controlled study. Scand J Rheumatol. 2016;45:304–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Stamp LK, Barclay ML, O'Donnell JL, Zhang M, Drake J, Frampton C, et al. Furosemide increases plasma oxypurinol without lowering serum urate – a complex drug interaction: implications for clinical practice. Rheumatology. 2012;51:1670–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Knake C, Stamp L, Bahn A. Molecular mechanism of an adverse drug–drug interaction of allopurinol and furosemide in gout treatment. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2014;452:157–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Ferreira JP, Inzucchi SE, Mattheus M, Meinicke T, Steubl D, Wanner C, et al. Empagliflozin and uric acid metabolism in diabetes: a post hoc analysis of the EMPA‐REG OUTCOME trial. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2021;24:135–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Hu X, Yang Y, Hu X, Jia X, Liu H, Wei M, et al. Effects of sodium‐glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors on serum uric acid in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a systematic review and network meta‐analysis. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2021;24:228–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Li J, Badve SV, Zhou Z, Rodgers A, Day R, Oh R, et al. The effects of canagliflozin on gout in type 2 diabetes: a post‐hoc analysis of the CANVAS program. Lancet Rheumatol. 2019;1:E220–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Suzuki S, Yoshihisa A, Yokokawa T, Kobayashi A, Yamaki T, Kunii H, et al.; Multicenter Randomized Trial Investigators . Comparison between febuxostat and allopurinol uric acid‐lowering therapy in patients with chronic heart failure and hyperuricemia: a multicenter randomized controlled trial. J Int Med Res. 2021;49:030006052110627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Wolff ML, Cruz JL, Vanderman AJ, Brown JN. The effect of angiotensin II receptor blockers on hyperuricemia. Therap Adv Chron Dis. 2015;6:339–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Kramer F, Voss S, Roessig L, Igl B, Butler J, Lam CSP, et al. Evaluation of high‐sensitivity C‐reactive protein and uric acid in vericiguat‐treated patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction. Eur J Heart Fail 2020;22:1675–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1. Cumulative incidence of the primary composite endpoint, cardiovascular death, heart failure hospitalization and all‐cause mortality according to baseline uric acid tertile.

Figure S2. Change in estimated glomerular filtration rate from baseline with slope analysis over days 14–720, by treatment group.

Figure S3. ‘Waterfall plot’ of change in uric acid between baseline and 52 weeks in each treatment group.

Table S1. Risk of various endpoints according to uric acid levels at randomization, per 1 mg/dl unit increase above 7 mg/dl.