Abstract

The SsuDAT1I restriction-modification (R-M) system, which contains two methyltransferases and two restriction endonucleases with recognition sequence 5′-GATC-3′, was first found in a field isolate of Streptococcus suis serotype 2. Isoschizomers of the R-M system were found in the same locus between purH and purD in a field isolate of serotype 1/2 and the reference strains of serotypes 3, 7, 23, and 26 among 29 strains of different serotypes examined in this study. The R-M gene sequences in serotypes 1/2, 3, 7, and 23 were very similar to those of SsuDAT1I, whereas those in serotype 26 were less similar. These results indicate intraspecies recombination among them and genetic divergence through their evolution.

Restriction-modification (R-M) systems are distributed in a variety of microorganisms (29). The simplest systems are type II R-M systems, which usually consist of two separate enzymes, a restriction endonuclease and a methyltransferase (4, 40). Genes for R-M systems have sometimes been found to be located on transferable elements, such as plasmids and bacteriophages, and in some cases, genes encoding proteins involved in DNA mobility, such as transposases, integrases, and invertases, are found in the vicinity of the genes for R-M systems (3, 5, 18, 21, 30, 35, 38–40). These genetic structures may facilitate the transfer of R-M systems and may contribute to the wide distribution of the R-M systems (17). The above findings, together with recent studies of the complete sequences of bacterial genomes, have led to a proposal that R-M systems are likely to be mobile genetic elements (2, 8, 17, 19, 25, 26, 36). However, a few examples in which genes for R-M systems are not colocalized with a gene for DNA transfer are known, indicating that other mechanisms are involved in the spread of R-M systems (9, 32, 41).

Streptococcus suis is a gram-positive, indifferent anaerobic coccus that has been implicated as the cause of a wide range of clinical diseases in swine and other domestic animals (10). Recently, we showed that some S. suis strains of serotypes 1 and 2 possessed a type II R-M system, whereas the type strain, NCTC10234, as well as some other strains, lacked a type II R-M system (32). This R-M system is an isoschizomer of Moraxella bovis MboI (12), which recognizes 5′-GATC-3′, and the one found in the strain DAT1 was designated SsuDAT1I. SsuDAT1I is unique among all type II R-M systems described to date in that it contains two methyltransferase genes and two isoschizomeric restriction endonuclease genes. Nucleotide sequence analysis revealed that the R-M gene region comprising 3,503 bp has moved from distant sources and inserted in the intergenic sequence between purH and purD. Since the genetic organization was conserved among the strains tested, we suggested that the R-M genes have been horizontally transferred among S. suis strains. However, because the strains studied comprised a limited number of serotypes, we could not rule out the possibility that the strains having the R-M system were clonal. S. suis strains are presently classified into 35 capsular serotypes (13, 14, 16, 28), and the genetic heterogeneity and the phylogenetic diversity of the serotype reference strains have been described previously (7, 15, 27). In this communication, using the reference strains of serotypes 1 through 28 and a field isolate of serotype 1/2, we present further evidence that the R-M system was horizontally transferred among S. suis strains of different serotypes.

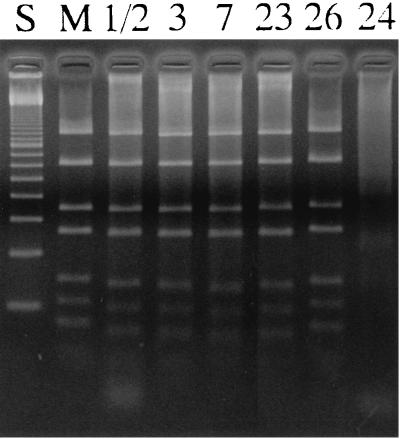

The bacterial strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. These strains, except DAT1 and NIAH11318, are the reference strains of each serotype. Strain NIAH11318 was isolated from a pig with meningitis in Japan. Strains NCTC10234 and NCTC10237 were purchased from the National Collection of Type Cultures, Central Public Health Laboratory, London, England. Strains of serotypes 3 through 8 and 9 through 28 were supplied by J. Henrichsen and M. Gottschalk, respectively, via Y. Kataoka. The strains described hereafter, except DAT1 and NCTC10234, are referred to by their serotypes. Bacteria were grown in Todd-Hewitt broth or agar medium (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, Mich.) at 37°C with 5% CO2 for 18 h. Genomic DNA was isolated from the S. suis strains as described previously (32). Methylation of the adenine residue in the 5′-GATC-3′ sequence was determined by testing the susceptibility of the DNA to restriction endonucleases DpnI and MboI, which are specific for methylated and unmethylated DNA, respectively. Restriction digests were analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis using standard procedures (31). The genomic DNAs isolated from serotypes 1/2, 3, 7, 23, 24, and 26 could be digested to small fragments by DpnI but not by MboI, as was seen in strain DAT1 (32), while the converse was seen in the other serotypes (data not shown). This indicated that the genomic DNAs of the six serotypes above were methylated, whereas those of the others were unmethylated. Crude cellular extracts of the six serotypes were then prepared, and their DNA cleavage activities were examined using unmethylated pUC19 DNA substrate as described previously (32, 42). As shown in Fig. 1, the crude extracts prepared from serotypes 1/2, 3, 7, 23, and 26 showed restriction endonuclease activity indistinguishable from that of MboI. Thus, these five strains possessed an R-M system isoschizomeric to SsuDAT1I. The DNA cleavage activity of the extract from serotype 24 was weak, and nonspecific degradation of the substrate DNA occurred (Fig. 1); therefore, we could not determine the specificity of the enzyme.

TABLE 1.

S. suis strains used in this study

| Strain | Serotype | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| DAT1 | 2 | 37 |

| NIAH11318 | 1/2 | This study |

| NCTC10237 | 1 | 28 |

| NCTC10234 | 2 | 28 |

| 4961 | 3 | 28 |

| 6407 | 4 | 28 |

| 11538 | 5 | 28 |

| 2524 | 6 | 28 |

| 8074 | 7 | 28 |

| 14636 | 8 | 28 |

| 22083 | 9 | 14 |

| 4417 | 10 | 14 |

| 12814 | 11 | 14 |

| 8830 | 12 | 14 |

| 10581 | 13 | 14 |

| 13730 | 14 | 14 |

| NCTC10446 | 15 | 14 |

| 2726 | 16 | 14 |

| 93A | 17 | 14 |

| NT77 | 18 | 14 |

| 42A | 19 | 14 |

| 86-5192 | 20 | 14 |

| 14A | 21 | 14 |

| 88-1861 | 22 | 14 |

| 89-2479 | 23 | 13 |

| 88-5299A | 24 | 13 |

| 89-3576-3 | 25 | 13 |

| 89-4109-1 | 26 | 13 |

| 89-5259 | 27 | 13 |

| 89-590 | 28 | 13 |

FIG. 1.

Restriction cleavage activities of the crude extracts using unmethylated pUC19 as the substrate. Lane numbers represent the serotypes of the strains from which the crude extracts were prepared. M, pUC19 digested with MboI; S, 100-bp ladder size standards (GIBCO/BRL).

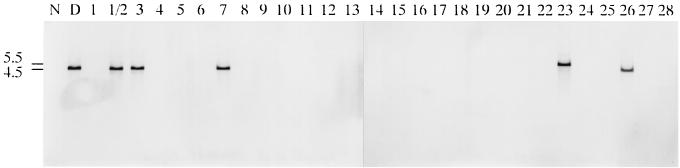

To examine the presence of genes homologous to SsuDAT1I genes, we performed genomic Southern hybridization using the same procedures as described previously (32). The 3,503-bp fragment of the SsuDAT1I region was amplified by PCR from the genomic DNA of strain DAT1 using primers 5′-AAGTATAGCACCCCAGCTGGAGAAG-3′ and 5′-CTTGATTATCTAAACAAATCATGC-3′, which were complementary to the 5′ and 3′ ends, respectively, of the 3,503-bp SsuDAT1I region. The conditions of the PCR were essentially the same as described previously (32). The amplified product was labeled with digoxigenin to probe S. suis genomic DNAs that had been digested with PvuII, for which no cutting site is present in the 3,503-bp SsuDAT1I region. A DNA fragment that strongly hybridized with the probe was seen in the digested DNAs of serotypes 1/2, 3, 7, 23, and 26 (Fig. 2). The sizes of the fragments in serotypes 1/2, 3, 7, and 26 were the same (4.5 kb) as that which appeared in the strain DAT1, while that which appeared in serotype 23 was larger (5.5 kb) than the others. These results indicated that the five strains possessed R-M genes which were highly homologous to the SsuDAT1I genes. However, no hybridizing fragment appeared in the digested DNAs of other serotypes, including serotype 24, which showed a methylated phenotype and a low level of restriction cleavage activity. This indicated that the strains which showed an unmethylated phenotype do not possess R-M genes homologous to the SsuDAT1I genes and that the R-M enzymes in serotype 24 may be encoded by nonhomologous genes which do not hybridize the SsuDAT1I probe under the experimental conditions.

FIG. 2.

Genomic Southern hybridization of S. suis strains probed with 3,503-bp fragment of the SsuDAT1I gene region. DNA was digested with PvuII and separated by agarose gel electrophoresis. Lane numbers represent the serotypes of the strains used. N, NCTC10234; D, DAT1. Molecular sizes of the signals that appeared are indicated on the left in kilobases.

The location and genetic organization of the R-M system described above were analyzed by PCR using primers 5′-GCGCTAGCTATTTTGACCAATA-3′ and 5′-GCAAAGTCTTTTGACCACTCTA-3′, which were designed to correspond to purH and purD sequences, respectively (32). The genomic DNAs of serotypes 1/2, 3, 7, 23, 24, and 26 were used as templates for test samples, and those of DAT1 and NCTC10234 were used for controls. A 4.3-kb fragment was amplified from serotypes 1/2, 3, 7, 23, and 26 as well as strain DAT1 (data not shown). Thus, these five strains were considered to possess the same genetic organization in the corresponding DNA region. On the other hand, when the genomic DNA of serotype 24 was used, a 1.0-kb fragment was amplified, as was also seen in strain NCTC10234 (data not shown), and the R-M genes were thus completely missing in this region. Therefore, the R-M genes, if they exist in serotype 24, may be present in a separate location.

The nucleotide sequences of the R-M genes in serotypes 1/2, 3, 7, 23, and 26 were directly determined using the 4.3-kb fragments described above. The R-M gene regions of all these serotypes consisted of 3,503 bp. The sequence alignment of the junction regions where the R-M genes were inserted showed that several features previously found in the junction regions (32) were also observed in these serotypes, i.e., (i) the insertion target site, 5′-GA(-/G)(T/A) ↓ TTTG-3′, as indicated by the arrow, (ii) a direct repeat of 3 bp, AAG, at both ends of the R-M region, and (iii) a lack of transposable element and long repeated sequences. Therefore, the unique structure of the SsuDAT1I genes, two methyltransferase genes and two restriction endonuclease genes without long repeated sequences or mobility genes, was substantially conserved among the six serotypes, indicating that these R-M systems shared the same origin.

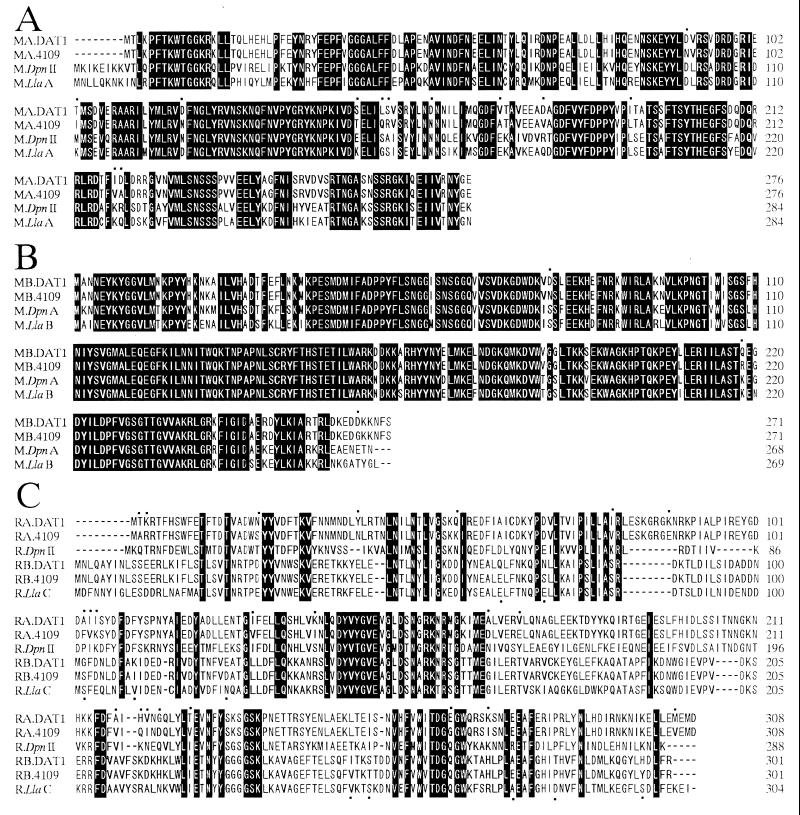

Comparison of the 3,503-bp R-M gene sequences among serotypes 1/2, 3, 7, and 23 and DAT1 showed striking similarity (99.86 to 99.97% identity). However, relatively low similarity between serotype 26 and the other serotypes (94.38 to 94.43% identity) was noted. The deduced amino acid sequences of the R-M enzymes in serotypes 1/2, 3, 7 and 23 were completely identical to those of SsuDAT1I. On the other hand, some amino acid differences were found between the R-M enzymes of serotype 26 and those of SsuDAT1I. Therefore, the R-M system found in serotype 26 (strain 89-4109-1) was designated Ssu4109I. The amino acid sequences of four enzymes in Ssu4109I, designated M.Ssu4109IA, M.Ssu4109IB, R.Ssu4109IA, and R.Ssu4109IB, were aligned with those of SsuDAT1I and other closely related enzymes, DpnII and LlaDCHI (20, 23, 32) (Fig. 3). Among the amino acids that differed between Ssu4109I and SsuDAT1I, several amino acids, Asn120, Asn160, and Leu192 (in M.Ssu4109IA), Lys105 and Val218 (in R.Ssu4109IA), and Glu67, Ser102, and Val250 (in R.Ssu4109IB), are the same as the corresponding amino acids in DpnII and/or LlaDCHI.

FIG. 3.

Sequence alignment of M.SsuDAT1IA (MA.DAT1), M.Ssu4109IA (MA.4109), M.DpnII, and M.LlaA (A); M.SsuDAT1IB (MB.DAT1), M.Ssu4109IB (MB.4109), M.DpnA, and M.LlaB (B); and R.SsuDAT1IA (RA.DAT1), R.Ssu4109IA (RA.4109), R.DpnII, R.SsuDAT1IB (RB.DAT1), R.Ssu4109IB (RB.4109), and R.LlaDCHI (R.LlaC) (C). Black background, amino acids identical among all the sequences aligned; dashes, gaps in the aligned sequences; dots, positions where the amino acids of SsuDAT1I are different from those of Ssu4109I. DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank accession numbers of the sequences of the SsuDAT1I, DpnII, and LlaDCHI systems are AB045609 (32), M14339 (20), and U16027 (23), respectively.

Highly virulent strains of S. suis, especially strains of serotype 2, which caused meningitis and/or septicemia, have been shown to be genetically homogenous, whereas other strains isolated from pigs with pneumonia or healthy pigs were diverse (1, 6, 33, 34). Since the S. suis field isolates examined in our previous study were mostly isolated from diseased pigs with meningitis (32), it was possible that the strains we had used were clonal or closely related. In contrast, the S. suis strains used in this study had different origins in terms of species, health status, tissue origin, and geographical location (13, 14, 28). Phylogenetic analysis using 16S rRNA gene sequences showed that the S. suis reference strains were closely related and that the strains of serotypes 1/2 and 1 through 31 constituted a major group. However, they could be divided into three clusters (7). According to the cluster analysis (7), the reference strains of serotypes 1, 2, 3, and 23 were classified into cluster I, whereas those of serotype 7 and 26 were classified into clusters II and III, respectively. Furthermore, restriction fragment polymorphism analysis of rRNA genes showed that most of the serotype reference strains, especially serotypes 1/2, 3, 7, 23, and 26, were not closely related (15, 27). Therefore, the reference strains which were found to possess the R-M system appeared to belong to different clonal lineages.

The R-M system isoschizomeric to SsuDAT1I was found in five of the 29 strains of different serotype that were examined, and in each case the genes for the system were inserted in the same place in the genome, between purH and purD. No long repeated DNA sequences or transposable elements were found in the vicinity of the R-M systems. These findings support the hypothesis that the SsuDAT1I system was originally inserted in S. suis from a foreign source by illegitimate recombination and was subsequently transferred among S. suis strains by homologous recombination via conserved flanking housekeeping genes rather than by insertion of mobile genetic elements. The R-M gene sequences in serotypes 1/2, 3, 7, and 23 were very similar to those of SsuDAT1I. This may be due to the fact that the S. suis serotype 2 is predominant among isolates from pigs. Since many healthy pigs harbor S. suis as an early colonizer (11, 22, 24), the bacteria may encounter each other in vivo, and frequent colonization by these bacteria in pigs may facilitate an exchange of DNA. On the other hand, there was some deviation in sequences between the genes for Ssu4109I and the others, indicating their evolutionary divergence. This finding suggests an early original insertion in S. suis with transmission along two lines and recent lateral transfers from one line into the other strains, all of which were apparently mediated by homologous recombination.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The nucleotide sequences for the R-M region in serotypes 1/2, 3, 7, 23, and 26 determined in this study have been deposited in the DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank database under accession no. AB058941, AB058942, AB058943, AB058944, and AB058945, respectively.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Y. Kataoka for providing us with the S. suis strains. We thank T. Fujisawa for preparing photographs and M. Takahashi for technical assistance.

A part of this work was supported by a Grant-in-Aid for the Pioneer Research Project to T.S. from the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry, and Fisheries, Tokyo, Japan.

REFERENCES

- 1.Allgaier A, Goethe R, Wisselink H J, Smith H E, Valentin-Weigand P. Relatedness of Streptococcus suis isolates of various serotypes and clinical backgrounds as evaluated by macrorestriction analysis and expression of potential virulence traits. J Clin Microbiol. 2001;39:445–453. doi: 10.1128/JCM.39.2.445-453.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alm R A, Ling L-S L, Moir D T, King B L, Brown E D, Doig P C, Smith D R, Noonan B, Guild B C, deJonge B L, Carmel G, Tummino P J, Caruso A, Uria-Nickelsen M, Mills D M, Ives C, Gibson R, Merberg D, Mills S D, Jiang Q, Taylor D E, Vovis G F, Trust T J. Genomic-sequence comparison of two unrelated isolates of the human gastric pathogen Helicobacter pylori. Nature. 1999;397:176–180. doi: 10.1038/16495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anton B P, Heiter D F, Benner J S, Hess E J, Greenough L, Moran L S, Slatko B E, Brooks J E. Cloning and characterization of the BglII restriction-modification system reveals a possible evolutionary footprint. Gene. 1997;187:19–27. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(96)00638-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bickle T A, Kruger D H. Biology of DNA restriction. Microbiol Rev. 1993;57:434–450. doi: 10.1128/mr.57.2.434-450.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brassard S, Paquet H, Roy P H. A transposon-like sequence adjacent to the AccI restriction-modification operon. Gene. 1995;157:69–72. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(94)00734-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chatellier S, Gottschalk M, Higgins R, Brousseau R, Harel J. Relatedness of Streptococcus suis serotype 2 isolates from different geographic origins as evaluated by molecular fingerprinting and phenotyping. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:362–366. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.2.362-366.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chatellier S, Harel J, Zhang Y, Gottschalk M, Higgins R, Devriese L A, Brousseau R. Phylogenetic diversity of Streptococcus suis strains of various serotypes as revealed by 16S rRNA gene sequence comparison. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1998;48:581–589. doi: 10.1099/00207713-48-2-581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chinen A, Uchiyama I, Kobayashi I. Comparison between Pyrococcus horikoshii and Pyrococcus abyssi genome sequences reveals linkage of restriction-modification genes with large genome polymorphisms. Gene. 2000;259:109–121. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(00)00459-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Claus H, Friedrich A, Frosch M, Vogel U. Differential distribution of novel restriction-modification systems in clonal lineages of Neisseria meningitidis. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:1296–1303. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.5.1296-1303.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clifton-Hadley F A. Streptococcus suis type 2 infections. Br Vet J. 1983;139:1–5. doi: 10.1016/s0007-1935(17)30581-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Clifton-Hadley F A, Alexander T J L. The carrier site and carrier rate of Streptococcus suis type II in pigs. Vet Rec. 1980;107:40–41. doi: 10.1136/vr.107.2.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gelinas R E, Myers P A, Roberts R J. Two sequence-specific endonucleases from Moraxella bovis. J Mol Biol. 1977;114:169–179. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(77)90290-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gottschalk M, Higgins R, Jacques M, Beaudoin M, Henrichsen J. Characterization of six new capsular types (23 through 28) of Streptococcus suis. J Clin Microbiol. 1991;29:2590–2594. doi: 10.1128/jcm.29.11.2590-2594.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gottschalk M, Higgins R, Jacques M, Mittal K R, Henrichsen J. Description of 14 new capsular types of Streptococcus suis. J Clin Microbiol. 1989;27:2633–2636. doi: 10.1128/jcm.27.12.2633-2636.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Harel J, Higgins R, Gottschalk M, Bigras-Poulin M. Genomic relatedness among reference strains of different Streptococcus suis serotypes. Can J Vet Res. 1994;58:259–262. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Higgins R, Gottschalk M, Boudreau M, Lebrun A, Henrichsen J. Description of six new capsular types (29-34) of Streptococcus suis. J Vet Diagn Investig. 1995;7:405–406. doi: 10.1177/104063879500700322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jeltsch A, Pingoud A. Horizontal gene transfer contributes to the wide distribution and evolution of type II restriction-modification systems. J Mol Evol. 1996;42:91–96. doi: 10.1007/BF02198833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kita K, Tsuda J, Kato T, Okamoto K, Yanase H, Tanaka M. Evidence of horizontal transfer of the EcoO109I restriction-modification gene to Escherichia coli chromosomal DNA. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:6822–6827. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.21.6822-6827.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kobayashi I, Nobusato A, Kobayashi-Takahashi N, Uchiyama I. Shaping the genome–restriction-modification systems as mobile genetic elements. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 1999;9:649–656. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(99)00026-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lacks S A, Mannarelli B M, Springhorn S S, Greenberg B. Genetic basis of the complementary DpnI and DpnII restriction systems of S. pneumoniae: an intercellular cassette mechanism. Cell. 1986;46:993–1000. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90698-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee K F, Shaw P C, Picone S J, Wilson G G, Lunnen K D. Sequence comparison of the EcoHK31I and EaeI restriction-modification systems suggests an intergenic transfer of genetic material. Biol Chem. 1998;379:437–441. doi: 10.1515/bchm.1998.379.4-5.437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Macinnes J I, Desrosiers R. Agents of the “suis-ide diseases” of swine: Actinobacillus suis, Haemophilus suis, and Streptococcus suis. Can J Vet Res. 1999;63:83–89. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moineau S, Walker S A, Vedamuthu E R, Vandenbergh P A. Cloning and sequencing of LlaII restriction/modification genes from Lactococcus lactis and relatedness of this system to the Streptococcus pneumoniae DpnII system. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61:2193–2202. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.6.2193-2202.1995. . (Author's Correction, 61:3514.) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mwaniki C G, Robertson I D, Trott D J, Atyeo R F, Lee B J, Hampson D J. Clonal analysis and virulence of Australian isolates of Streptococcus suis type 2. Epidemiol Infect. 1994;113:321–334. doi: 10.1017/s095026880005175x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nobusato A, Uchiyama I, Kobayashi I. Diversity of restriction-modification gene homologues in Helicobacter pylori. Gene. 2000;259:89–98. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(00)00455-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nobusato A, Uchiyama I, Ohashi S, Kobayashi I. Insertion with long target duplication: a mechanism for gene mobility suggested from comparison of two related bacterial genomes. Gene. 2000;259:99–108. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(00)00456-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Okwumabua O, Staats J, Chengappa M M. Detection of genomic heterogeneity in Streptococcus suis isolates by DNA restriction fragment length polymorphisms of rRNA genes (ribotyping) J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:968–972. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.4.968-972.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Perch B, Pedersen K B, Henrichsen J. Serology of capsulated streptococci pathogenic for pigs: six new serotypes of Streptococcus suis. J Clin Microbiol. 1983;17:993–996. doi: 10.1128/jcm.17.6.993-996.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Roberts R J, Macelis D. REBASE-restriction enzymes and methylases. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:268–269. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.1.268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rochepeau P, Selinger L B, Hynes M F. Transposon-like structure of a new plasmid-encoded restriction-modification system in Rhizobium leguminosarum VF39SM. Mol Gen Genet. 1997;256:387–396. doi: 10.1007/s004380050582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sekizaki T, Otani Y, Osaki M, Takamatsu D, Shimoji Y. Evidence for horizontal transfer of SsuDAT1I restriction-modification genes to the Streptococcus suis genome. J Bacteriol. 2001;183:500–511. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.2.500-511.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Smith H E, Rijnsburger M, Stockhofe-Zurwieden N, Wisselink H J, Vecht U, Smits M A. Virulent strains of Streptococcus suis serotype 2 and highly virulent strains of Streptococcus suis serotype 1 can be recognized by a unique ribotype profile. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:1049–1053. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.5.1049-1053.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Staats J J, Plattner B L, Nietfeld J, Dritz S, Chengappa M M. Use of ribotyping and hemolysin activity to identify highly virulent Streptococcus suis type 2 isolates. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:15–19. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.1.15-19.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stankevicius K, Povilionis P, Lubys A, Menkevicius S, Janulaitis A. Cloning and characterization of the unusual restriction-modification system comprising two restriction endonucleases and one methyltransferase. Gene. 1995;157:49–53. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(94)00796-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stein D C, Gunn J S, Piekarowicz A. Sequence similarities between the genes encoding the S.NgoI and HaeII restriction/modification systems. Biol Chem. 1998;379:575–578. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Takamatsu D, Osaki M, Sekizaki T. Sequence analysis of a small cryptic plasmid isolated from Streptococcus suis serotype 2. Curr Microbiol. 2000;40:61–66. doi: 10.1007/s002849910012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Twomey D P, McKay L L, O'Sullivan D J. Molecular characterization of the Lactococcus lactis LlaKR2I restriction-modification system and effect of an IS982 element positioned between the restriction and modification genes. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:5844–5854. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.22.5844-5854.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vaisvila R, Vilkaitis G, Janulaitis A. Identification of a gene encoding a DNA invertase-like enzyme adjacent to the PaeR7I restriction-modification system. Gene. 1995;157:81–84. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(94)00793-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wilson G G, Murray N E. Restriction and modification systems. Annu Rev Genet. 1991;25:585–627. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ge.25.120191.003101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Xu Q, Stickel S, Roberts R J, Blaser M J, Morgan R D. Purification of the novel endonuclease, Hpy188I, and cloning of its restriction-modification genes reveal evidence of its horizontal transfer to the Helicobacter pylori genome. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:17086–17093. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M910303199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yanisch-Perron C, Vieira J, Messing J. Improved M13 phage cloning vectors and host strains: nucleotide sequences of the M13mp18 and pUC19 vectors. Gene. 1985;33:103–119. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(85)90120-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]