Abstract

The initiator protein Cdc6 (Cdc18 in fission yeast) plays an essential role in the initiation of eukaryotic DNA replication. In yeast the protein is expressed before initiation of DNA replication and is thought to be essential for loading of the helicase onto origin DNA. The biochemical properties of the protein, however, are largely unknown. Using three archaeal homologues of Cdc6, it was found that the proteins are autophosphorylated on Ser residues. The winged-helix domain at the C terminus of Cdc6 interacts with DNA, which apparently regulates the autophosphorylation reaction. Yeast Cdc18 was also found to autophosphorylate, suggesting that this function of Cdc6 may play a widely conserved and essential role in replication initiation.

Both protein phosphorylation and ATP binding and hydrolysis have important regulatory functions in DNA replication and cell cycle progression, playing both positive and negative roles. Some proteins utilize one mechanism or the other for their activity, while others, like the initiator protein Cdc6 (Cdc18 in fission yeast), utilize both processes (14, 26, 36). The Cdc6 protein (Cdc6p) is necessary for the formation of the prereplicative complex, which is a prerequisite for the initiation of DNA replication in eukaryotes (9, 15). Genetic analysis in yeast demonstrated that Cdc6p interacts with the origin recognition complex (ORC) and plays an important role in loading the minichromosome maintenance (MCM) family of proteins onto chromatin during G1 (6, 31, 36). Cdc6p also shows significant similarity to a group of enzymes that function as ATP-dependent clamp loaders for DNA polymerase processivity factors around duplex DNA (26).

The similarities between Cdc6p and the clamp loaders of DNA polymerase, together with the genetic data, suggest that Cdc6p acts as an assembly factor for the MCM helicase at the origin prior to DNA synthesis (33). At the initiation of S phase, Cdc6p is phosphorylated by cyclin-dependent kinases (CDKs) and rapidly degraded in an ubiquitin-dependent manner (2, 7, 10, 14). In addition, the protein belongs to the AAA+ superfamily of ATPases (25). Members of this family contain a purine nucleoside triphosphate binding site containing the signature Walker-A [GXXGXGKT(T/S)] and -B [D(D/E)XX] motifs (35). The Walker-A motif is thought to be important for ATP binding, while the Walker-B motif is thought to be involved in ATP hydrolysis (29, 30). Mutational analyses of these motifs in the budding and fission yeasts demonstrated the essential role of ATP binding and hydrolysis for Cdc6p function in vivo (summarized in references 15 and 20). However, the biochemical properties of Cdc6p and the roles played by ATP in its functions are largely unknown. It was suggested that ATP binding changes the conformation of the protein as a prerequisite for functional interactions with the helicase, whereas ATP hydrolysis may be involved in the release of MCM after assembly around DNA (20, 24).

The archaea, which constitute the third domain of life, are prokaryotes with information processes (replication, transcription, and translation) thought to be more similar to those in eukarya than in bacteria (reference 16 and references therein). These processes, however, appear to be simpler, as fewer proteins and complexes are needed. The thermophilic archaeon Methanobacterium thermoautotrophicum ΔH has two Cdc6 homologues, MTH1412 and MTH1599 (28; H. Myllykallio and P. Forterre, Trends Microbiol. 8:537–539, 2000) (herein referred to as mthCdc6-1 and mthCdc6-2, respectively). Although both proteins belong to the AAA+ family of ATPases, no appreciable ATP hydrolysis could be detected (data not shown). Similarly, in vitro studies with Saccharomyces cerevisiae Cdc6p (scCdc6p) and Schizosaccharomyces pombe Cdc18p (spCdc18p) failed to detect ATPase activity (36), and, to date, only a recombinant human glutathione S-transferase–Cdc6p fusion has been shown to bind and hydrolyze ATP in vitro (12).

M. thermoautotrophicum Cdc6 homologues are autophosphorylated.

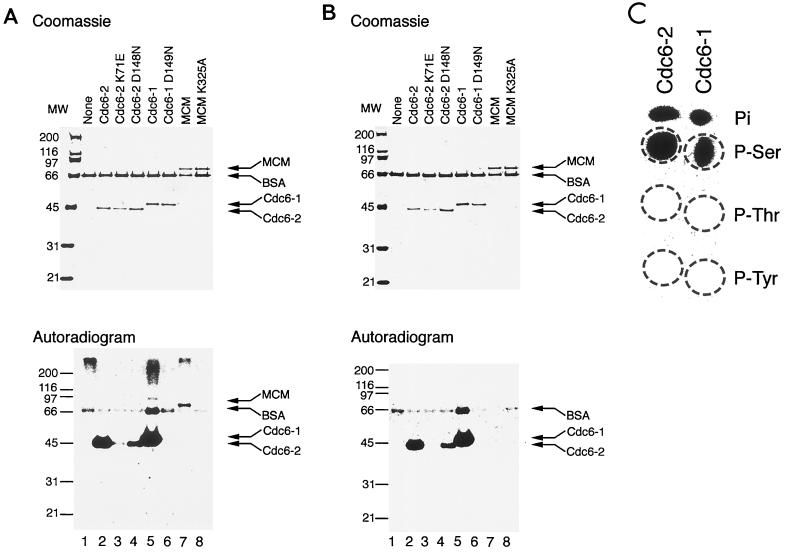

In an attempt to resolve the discrepancy between predicted ATPase function for Cdc6p, derived from its primary amino acid sequence, and the observed absence of this activity, the ability of mthCdc6-1 and -2 to bind [γ-32P]ATP was determined using UV-cross-linking experiments (Fig. 1A). The MCM protein, which has previously been shown to bind and hydrolyze ATP (3, 17, 27), was used as a positive control. Although ATP cross-linking experiments are known to have low efficiency, all three wild-type proteins were labeled (Fig. 1A, lanes 2, 5, and 7). No appreciable labeling could be detected when proteins with mutations in the Walker-A motif, mthCdc6-2 (K71E) and MCM (K325A), were used (Fig. 1A, lanes 3 and 8). mthCdc6-2 (D148N), with a mutation in the Walker-B motif, retained some ability to be labeled (Fig. 1A, lane 4); however, mthCdc6-1 with a similar mutation (D149N) was not labeled under similar conditions (lane 6). The difference may lie in the sequences of the two Walker-B motifs: whereas the motif in mthCdc6-1 is DEXX, the sequence in mthCdc6-2 is DDXX. The structure of the Cdc6 homologue from the archaeon Pyrobaculum aerophilum, which has the DDXX motif, revealed that both Asp residues interact with Mg2+ (21). Thus, it is possible that replacement of the single Asp in mthCdc6-1 is more severe for ATP binding than replacement of one Asp in mthCdc6-2, which has an additional Asp that may still have residual interactions with Mg2+ and thus stabilize weak ATP binding. However, other residues outside the Walker-B motif also participate in nucleotide binding and thus may help stabilize the binding site of some of the Walker-B mutants.

FIG. 1.

M. thermoautotrophicum Cdc6 homologues are autophosphorylated on Ser residues. (A) UV cross-linking of mthCdc6-1 and -2 and mthMCM to ATP. Each protein (250 ng) was incubated for 10 min at 65°C in a reaction mixture containing 3.3 pmol of [γ-32P]ATP, 20 mM HEPES-NaOH (pH 7.5), 5 mM MgCl2, 2 mM dithiothreitol, and 250 ng of bovine serum albumin (BSA). Following incubation, the samples were exposed to 2.5 J of UV irradiation per cm2 in a model 2400 Stratalinker (Stratagene). The proteins were separated on SDS–10% PAGE and visualized by Coomassie blue staining and autoradiography. Higher-molecular-weight bands in the lower panel are probably due to cross-linked aggregates. MW, molecular weight (numbers are in thousands). (B) Autophosphorylation of mthCdc6-1 and -2. The experiment was performed as for panel A except that the UV cross-linking step was omitted. (C) mthCdc6-1 and -2 are phosphorylated on Ser residues. The proteins were autophosphorylated as for panel A using 6.6 pmol of [γ-32P]ATP without BSA followed by phosphoamino acid analyses using one-dimensional thin-layer chromatography as previously described (23). P-Ser, phosphoserine; P-Thr, phosphothreonine; P-Tyr, phosphotyrosine.

As a control for the cross-linking experiments, identical reactions were performed without UV irradiation (Fig. 1B). No labeling of the MCM protein could be detected without UV (Fig. 1B, lane 7). However, the mthCdc6 proteins that were labeled with UV were also labeled without UV (Fig. 1B, lanes 2, 4 and 5). When [α-32P]ATP was used instead of [γ-32P]ATP, only the wild-type MCM protein was labeled in the presence of UV and no labeled protein could be detected without UV (data not shown). No radiolabeled proteins could be observed in the absence of Mg2+, when 32Pi was used, or after denaturation at 95°C (data not shown). A competition experiment determined that only ATP and dATP could serve as phosphate donors (data not shown). Taken together, these results suggest that the M. thermoautotrophicum Cdc6 homologues undergo a phosphorylation reaction that requires a γ-phosphate of ATP or dATP and an intact Walker-A motif. A phosphoamino acid analysis with acid hydrolysis and one-dimensional electrophoresis revealed that both proteins are phosphorylated on Ser residues (Fig. 1C). Using the structure of P. aerophilum Cdc6p (paCdc6p) as a model, several exposed Ser residues on the surface of the M. thermoautotrophicum proteins were identified as possible candidates, although the exact site of phosphorylation is yet to be determined and is currently under investigation.

The requirement for ATP binding suggests that the phosphorylation reaction is autocatalytic. Although one Walker-B mutant (Fig. 1B, lane 4) could still autophosphorylate, the Walker-A mutant (lane 3) could not. Thus, mutations in the Walker-A motif, thought to be important for ATP binding, may impair function more severely, whereas subsets of Walker-B motif mutants may still be able to hydrolyze ATP and to autophosphorylate. In support of this notion, a Walker-B mutation in scCdc6p produced a normal growth phenotype (36), suggesting the ability to hydrolyze ATP. It is not likely that the phosphorylation reaction is due to a contaminating Escherichia coli kinase. M. thermoautotrophicum is a thermophilic microorganism with an optimal growth temperature of 65 to 70°C (37), and as with other M. thermoautotrophicum replication enzymes (e.g., see reference 18), optimal activity for Cdc6 autophosphorylation was observed at these temperatures. No phosphorylation could be detected when the reaction was performed at 30°C, and only partial labeling could be detected at 50°C (data not shown). Moreover, labeling of gel filtration fractions of mthCdc6-2 revealed that the peak of phosphorylation eluted at a position coincidental with the protein (data not shown). However, the level of the autophosphorylation is rather low (<1%). Although longer incubation times and higher ATP concentrations result in a higher level of phosphorylation, the reaction is not linear. It is likely that the autophosphorylation activity is regulated by cellular events and by other proteins and factors (e.g., during different stages of the cell cycle, discussed below). In addition, the proteins may be phosphorylated in E. coli during their expression, and thus, only a small fraction is available for labeling in vitro. It was shown that paCdc6p expressed in E. coli is purified with Mg · ADP bound to the active site (21), which may be true of the M. thermoautotrophicum protein as well and may therefore prevent additional ATP binding (discussed below).

DNA regulates the autophosphorylation of Cdc6p.

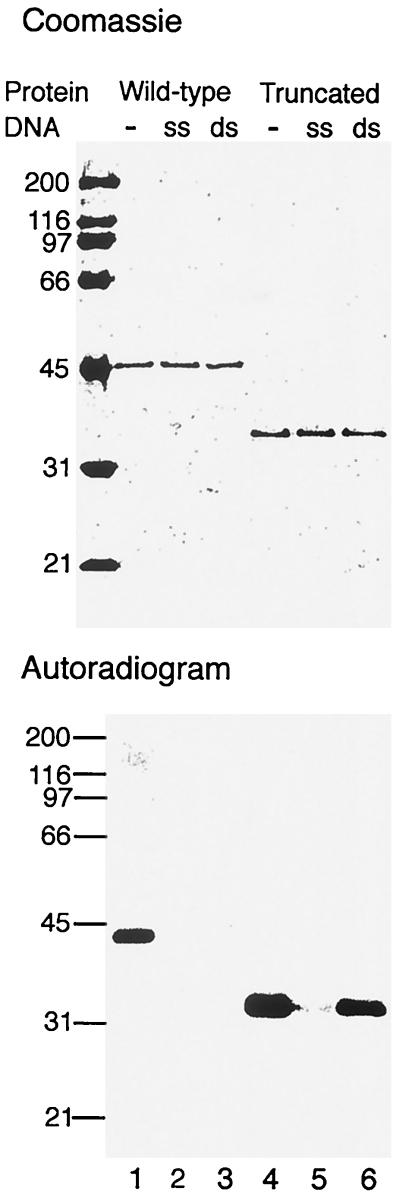

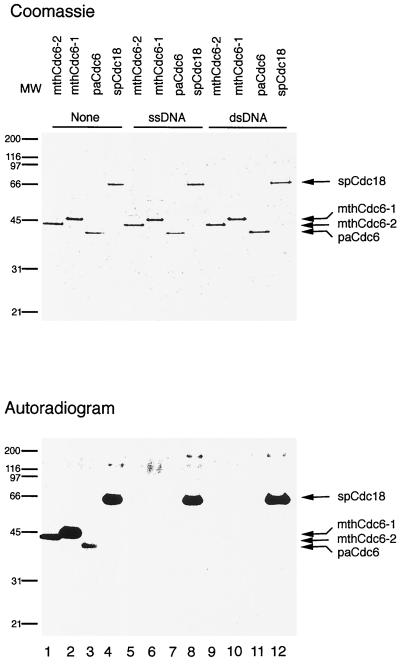

There is evidence that Cdc6p interacts with DNA either by itself or in conjunction with ORC (11, 24). Therefore, the effect of DNA on the phosphorylation reaction was examined. Both single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) and double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) inhibit the phosphorylation reactions of mthCdc6-1 and -2 (Fig. 2, compare lanes 2 and 3 to lane 1; Fig. 3, compare lanes 5 and 9 to lane 1 and compare lanes 6 and 10 to lane 2). Longer exposure of the gel shown in Fig. 3 revealed a weak phosphorylation band of mthCdc6-1 in the presence of DNA, demonstrating that the inhibitory effect of DNA on mthCdc6-1 is not as severe as that on mthCdc6-2. Nevertheless, these results suggest that the Cdc6p can interact with both ssDNA and dsDNA and that this interaction regulates the autophosphorylation activity of the protein.

FIG. 2.

DNA inhibits mthCdc6-2 autophosphorylation. mthCdc6-2 or its truncated form (250 ng each) was incubated for 10 min at 65°C in a reaction mixture containing 3.3 pmol of [γ-32P]ATP, 25 mM HEPES–NaOH (pH 7.5), 5 mM MgCl2, and 1 mM dithiothreitol in the absence (−) or presence of 1 μg of single- or double-stranded φX174 DNA. Following incubation, the proteins were separated on SDS–10% PAGE and visualized by Coomassie blue staining and autoradiography. Numbers on the left are molecular weights, in thousands.

FIG. 3.

Cdc6p autophosphorylation is conserved between archaea and eukaryotes. Each protein (250 ng) was incubated for 10 min at 65°C (mthCdc6-1, -2 and paCdc6p) or 30°C (spCdc18p) in a reaction mixture containing 3.3 pmol of [γ-32P]ATP, 25 mM HEPES-NaOH (pH 7.5), 5 mM MgCl2, and 1 mM dithiothreitol in the absence (“None”) or presence of 1 μg of single- or double-stranded φX174 DNA (New England Biolabs). Following incubation, the proteins were separated on SDS–10% PAGE and visualized by Coomassie blue staining and autoradiography. MW, molecular weight (numbers are in thousands).

The structure of paCdc6p revealed a winged-helix (WH) fold at the C-terminal domain of the protein and was identified, based on sequence similarities, at the C-terminal region of Cdc6p in all organisms studied (21). Since the paCdc6p shares 47 and 38% similarity with mthCdc6-1 and -2, respectively, it was suggested that all three proteins would have similar structures, including the presence of the WH fold (21). A WH fold is found in known dsDNA-binding proteins, including histones and transcription factors (21). However, the WH fold of Cdc6p in any organism has not yet been shown to interact with DNA.

A partial trypsin digest of the M. thermoautotrophicum proteins suggested that the phosphorylated amino acid is not located within the C-terminal region (data not shown). Therefore, the WH domain of mthCdc6-2 was deleted to determine whether this domain participates in dsDNA binding and whether it is needed for the DNA effect on mthCdc6-2 autophosphorylation. Although the truncated protein can undergo autophosphorylation (Fig. 2, lane 4), the inhibition by dsDNA is substantially reduced (compare lane 6 to lane 3). No major effect on the inhibition by ssDNA can be seen (Fig. 2, compare lane 5 to lane 2). These results suggest that, as predicted by the three-dimensional structure, the C-terminal WH domain of Cdc6p participates in the interactions with dsDNA. Autophosphorylation of both the full-length and truncated proteins was inhibited by ssDNA (Fig. 2, lanes 2 and 5), indicating that the region responsible for ssDNA interaction may be located in another region of the protein. The results suggest that DNA binding causes conformational changes that either sequester the phosphorylation site from the kinase domain or prevent phosphorylation by preventing nucleotide binding in the active site. One possible model for the interaction of Cdc6p with DNA may be inferred from the crystal structure of the PcrA protein, a monomeric DNA helicase from the thermophile Bacillus stearothermophilus, in which ADP is bound in a cleft between two N-terminal domains that bind ssDNA while two C-terminal domains bind dsDNA (34).

The autophosphorylation of Cdc6p is conserved in evolution.

How general a phenomenon is the autophosphorylation of Cdc6p? The ability to autophosphorylate was tested with a Cdc6 homologue from a different archaeal kingdom (Crenarchaeota). A recombinant Cdc6 homologue from P. aerophilum was expressed and purified from E. coli. Similar to the M. thermoautotrophicum proteins, the paCdc6 homologues undergo autophosphorylation (Fig. 3, lane 3). Apparently, Mg · ADP binds very tightly in the paCdc6p active site (21), and only denaturation with 6 M guanidinium, followed by refolding, could release the nucleotide. In fact, before treatment with guanidinium, the paCdc6p could not be phosphorylated when incubated with [γ-32P]ATP (data not shown). The tight binding of Mg · ADP may also account for the low level of autophosphorylation in mthCdc6 proteins. When mthCdc6-2 was denatured in 6 M guanidinium and refolded, the level of autophosphorylation increased about 10-fold (data not shown). These experiments demonstrate that Cdc6p autophosphorylation occurs at least in the two largest archaeal kingdoms.

Cdc6 phosphorylation also appears to be conserved among the eukaryotic proteins. When recombinant spCdc18p expressed and purified from baculovirus-infected insect cells is incubated with [γ-32P]ATP, the protein undergoes autophosphorylation (Fig. 3, lane 4). Since spCdc18p was expressed and purified from insect cells, contamination by a CDK might account for some of the spCdc18p phosphorylation observed. However, when chicken histone H1 was included in the phosphorylation reaction, only the spCdc18p was labeled (data not shown). Moreover, when the reaction was performed on proteins that were separated on sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE), transferred to nitrocellulose membranes, and renatured, only one band, corresponding to spCdc18p, was labeled (data not shown).

The experiments presented here demonstrate that both archaeal and eukaryal Cdc6 proteins are able to undergo autophosphorylation and suggest the generality of the autophosphorylation reaction as a regulatory or catalytic mechanism in Cdc6p functions. Given the functional similarity in mechanisms of DNA replication among the three domains (bacteria, archaea, and eukarya) (16, 20), it is also possible that the bacterial initiator protein, DnaA, or the helicase loader, DnaC, is autophosphorylated. There is an important difference, however, between the archaeal and eukaryal enzymes. While all three archaeal proteins were phosphorylated on Ser residues, spCdc18p was phosphorylated on both Ser and Thr residues (Fig. 1C and data not shown). spCdc18p phosphorylation by CDKs has been shown to occur on Thr residues (14, 22), and in vivo labeling studies determined that spCdc18p is also phosphorylated on Ser (14). It may be that the Ser phosphorylation and a portion of the Thr phosphorylation of spCdc18p are due to autophosphorylation, suggesting a function for the Ser phosphorylation that may be different from the regulatory function of the CDKs.

There is also a difference between the archaeal and eukaryal proteins in the effect of DNA on the phosphorylation reaction. Whereas the autophosphorylation of all three archaeal Cdc6 homologues was inhibited by both ssDNA and dsDNA (Fig. 3, compare lane 1 to lanes 5 and 9, lane 2 to lanes 6 and 10, and lane 3 to lanes 7 and 11), spCdc18p was not inhibited (compare lane 4 to lanes 8 and 12). These results suggest that the manner in which these proteins interact with DNA may have changed in the course of evolution from the archaeal to the eukaryotic versions. This is not surprising, since although they share the same evolutionary lineage, archaea are prokaryotes with a different cell cycle (1). Indeed, the eukaryotic Cdc6p proteins have an N-terminal extension thought to be important for DNA binding (11), whereas the archaeal homologues lack this region. Nevertheless, sequence (25, 26) and structural (21) similarities between the archaeal and eukaryotic proteins argue for similar functions, and the fact that the autophosphorylation reaction may be present in the eukaryotic proteins suggests that this activity may be essential.

Cdc6 autophosphorylation may play either a negative or a positive role in the initiation of archaeal DNA replication or may serve as an intermediate for a downstream phosphorylation reaction. In a model in which autophosphorylation plays a negative role, an equilibrium exists between an active ATP-bound form and an inactive ADP-bound form. A yet-unknown exchange factor may shift the equilibrium toward the ATP form, which then binds to the origin and recruits the helicase. On helicase loading, Cdc6p is autophosphorylated, dissociates from the complex, and is prevented from rebinding the origin. In the model in which autophosphorylation plays a positive role, only the phosphorylated ADP-bound form is active and binds to the origin. Following helicase recruitment, a nucleotide exchange mechanism converts this active form to an inactive form, preventing origin rebinding.

In light of the data presented here and the degree of homology between Cdc6p and Orc1p (32), it is conceivable that the eukaryotic Orc1p is capable of undergoing autophosphorylation as well. This activity may affect its DNA binding properties, accounting, in part, for the different DNA footprints observed during different phases of the cell cycle (5). To date, however, there are no experimental data to distinguish the archaeal Cdc6 proteins as functional homologues of either Orc1p or Cdc6p. mthCdc6-1 and mthCdc6-2 differ in the amount of autophosphorylation, with mthCdc6-1 autophosphorylated to an extent comparable to that of spCdc18p, suggesting that it may have a Cdc6p function. However, mthCdc6-1 is located adjacent to the putative M. thermoautotrophicum origin (P. Lopez, H. Philippe, H. Myllykallio, and P. Forterre, Letter, Mol. Microbiol. 32:883–886, 1999), similar to E. coli DnaA (19), suggesting a possible ORC-like function. Alternatively, it was suggested that the homologues may share functions of both Orc1p and Cdc6p (1), and both mthCdc6-1 and mthCdc6-2 do appear to inhibit mthMCM helicase activity (17) analogous to the bacterial helicase loader DnaC (19).

The studies presented here demonstrate that Cdc6p is autophosphorylated in both archaea and eukarya. A number of proteins involved in DNA replication are regulated by phosphorylation, including subunits of ORC, MCM2, Cdc6p, Polα, replication protein A, replication factor C, and the simian virus 40 large T antigen. Autophosphorylation also plays a role in various cellular processes, including signal transduction and replication. Hsp70 chaperone proteins known to autophosphorylate (13) include the E. coli DnaK protein (38), needed for bacteriophage P1 and λ replication (19). Intriguingly, Cdc6p has been suggested to function as a molecular chaperone in the assembly of the MCM helicase around DNA (4, 20). Autophosphorylation of Cdc6p may represent an additional layer of regulation of DNA replication. For example, it was shown that scCdc6p is degraded during G1 in a mechanism that is independent of the CDK phosphorylation sites (8). It is possible that a cellular signal during G1 stimulates the autophosphorylation of Cdc6p and leads to degradation of the protein. Autophosphorylation may have different regulatory functions in the archaeal and eukaryal cell cycles or the same function may be conserved in the more complex eukaryotic system, albeit supplemented and, perhaps, obscured by CDK regulation. Further studies with the archaeal and eukaryal enzymes will help determine the cellular roles played by the autophosphorylation of Cdc6p.

Acknowledgments

We thank J. Berger for the paCdc6 expression vector, J. Hurwitz and J.-K. Lee for the purified spCdc18, R. Kamakaka for the chicken histone H1, and J. Reeve for M. thermoautotrophicum DNA. We also thank J. Hurwitz, J.-K. Lee, H. Smith, and J. Berger for their helpful suggestions in the course of this work and J. Hurwitz, L. Kelman, J.-K. Lee, and K. Ridge for their comments on the manuscript.

Z.K. is an Invitrogen Professor.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bernander R. Chromosome replication, nucleoid segregation and cell division in archaea. Trends Microbiol. 2000;8:278–283. doi: 10.1016/s0966-842x(00)01760-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Calzada A, Sanchez M, Sanchez E, Bueno A. The stability of the Cdc6 protein is regulated by cyclin-dependent kinase/cyclin B complexes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:9734–9741. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.13.9734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chong J P, Hayashi M K, Simon M N, Xu R M, Stillman B. A double-hexamer archaeal minichromosome maintenance protein is an ATP-dependent DNA helicase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:1530–1535. doi: 10.1073/pnas.030539597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Davey M J, O'Donnell M. Mechanisms of DNA replication. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2000;4:581–586. doi: 10.1016/s1367-5931(00)00134-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Diffley J F, Cocker J H, Dowell S J, Rowley A. Two steps in the assembly of complexes at yeast replication origins in vivo. Cell. 1994;78:303–316. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90299-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Donovan S, Harwood J, Drury L S, Diffley J F. Cdc6p-dependent loading of Mcm proteins onto pre-replicative chromatin in budding yeast. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:5611–5616. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.11.5611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Drury L S, Perkins G, Diffley J F. The Cdc4/34/53 pathway targets Cdc6p for proteolysis in budding yeast. EMBO J. 1997;16:5966–5976. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.19.5966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Drury L S, Perkins G, Diffley J F. The cyclin-dependent kinase Cdc28p regulates distinct modes of Cdc6p proteolysis during the budding yeast cell cycle. Curr Biol. 2000;10:231–240. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00355-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dutta A, Bell S P. Initiation of DNA replication in eukaryotic cells. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 1997;13:293–332. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.13.1.293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Elsasser S, Chi Y, Yang P, Campbell J L. Phosphorylation controls timing of Cdc6p destruction: a biochemical analysis. Mol Biol Cell. 1999;10:3263–3277. doi: 10.1091/mbc.10.10.3263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Feng L, Wang B, Driscoll B, Jong A. Identification and characterization of Saccharomyces cerevisiae Cdc6 DNA-binding properties. Mol Biol Cell. 2000;11:1673–1685. doi: 10.1091/mbc.11.5.1673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Herbig U, Marlar C A, Fanning E. The Cdc6 nucleotide-binding site regulates its activity in DNA replication in human cells. Mol Biol Cell. 1999;10:2631–2645. doi: 10.1091/mbc.10.8.2631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hiromura M, Yano M, Mori H, Inoue M, Kido H. Intrinsic ADP-ATP exchange activity is a novel function of the molecular chaperone, Hsp70. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:5435–5438. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.10.5435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jallepalli P V, Brown G W, Muzi-Falconi M, Tien D, Kelly T J. Regulation of the replication initiator protein p65cdc18 by CDK phosphorylation. Genes Dev. 1997;11:2767–2779. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.21.2767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kelly T J, Brown G W. Regulation of chromosome replication. Annu Rev Biochem. 2000;69:829–880. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.69.1.829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kelman Z. DNA replication in the third domain (of life) Curr Protein Pept Sci. 2000;1:139–154. doi: 10.2174/1389203003381414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kelman Z, Lee J K, Hurwitz J. The single minichromosome maintenance protein of Methanobacterium thermoautotrophicum ΔH contains DNA helicase activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:14783–14788. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.26.14783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kelman Z, Pietrokovski S, Hurwitz J. Isolation and characterization of a split B-type DNA polymerase from the archaeon Methanobacterium thermoautotrophicum ΔH. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:28751–28761. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.40.28751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kornberg A, Baker T A. DNA replication. 2nd ed. New York, N.Y: W. H. Freeman; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee D G, Bell S P. ATPase switches controlling DNA replication initiation. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2000;12:280–285. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(00)00089-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu J, Smith C L, DeRyckere D, DeAngelis K, Martin G S, Berger J M. Structure and function of Cdc6/Cdc18: implications for origin recognition and checkpoint control. Mol Cell. 2000;6:637–648. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)00062-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lopez-Girona A, Mondesert O, Leatherwood J, Russell P. Negative regulation of Cdc18 DNA replication protein by Cdc2. Mol Biol Cell. 1998;9:63–73. doi: 10.1091/mbc.9.1.63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mahoney C W, Nakanishi N, Ohashi M. Phosphoamino acid analysis by semidry electrophoresis on cellulose thin-layer plates using the Pharmacia/LKB Multiphor or Atto flatbed apparatus. Anal Biochem. 1996;238:96–98. doi: 10.1006/abio.1996.0258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mizushima T, Takahashi N, Stillman B. Cdc6p modulates the structure and DNA binding activity of the origin recognition complex in vitro. Genes Dev. 2000;14:1631–1641. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Neuwald A F, Aravind L, Spouge J L, Koonin E V. AAA+: a class of chaperone-like ATPases associated with the assembly, operation, and disassembly of protein complexes. Genome Res. 1999;9:27–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Perkins G, Diffley J F. Nucleotide-dependent prereplicative complex assembly by Cdc6p, a homolog of eukaryotic and prokaryotic clamp-loaders. Mol Cell. 1998;2:23–32. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80110-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shechter D F, Ying C Y, Gautier J. The intrinsic DNA helicase activity of Methanobacterium thermoautotrophicum ΔH minichromosome maintenance protein. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:15049–15059. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M000398200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Smith D R, Doucette-Stamm L A, Deloughery C, Lee H, Dubois J, Aldredge T, Bashirzadeh R, Blakely D, Cook R, Gilbert K, Harrison D, Hoang L, Keagle P, Lumm W, Pothier B, Qiu D, Spadafora R, Vicaire R, Wang Y, Wierzbowski J, Gibson R, Jiwani N, Caruso A, Bush D, Reeve J N, et al. Complete genome sequence of Methanobacterium thermoautotrophicum ΔH: functional analysis and comparative genomics. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:7135–7155. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.22.7135-7155.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Story R M, Steitz T A. Structure of the recA protein-ADP complex. Nature. 1992;355:374–376. doi: 10.1038/355374a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Subramanya H S, Bird L E, Brannigan J A, Wigley D B. Crystal structure of a DExx box DNA helicase. Nature. 1996;384:379–383. doi: 10.1038/384379a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tanaka T, Knapp D, Nasmyth K. Loading of an Mcm protein onto DNA replication origins is regulated by Cdc6p and CDKs. Cell. 1997;90:649–660. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80526-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tugal T, Zou-Yang X H, Gavin K, Pappin D, Canas B, Kobayashi R, Hunt T, Stillman B. The Orc4p and Orc5p subunits of the Xenopus and human origin recognition complex are related to Orc1p and Cdc6p. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:32421–32429. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.49.32421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tye B K. MCM proteins in DNA replication. Annu Rev Biochem. 1999;68:649–686. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.68.1.649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Velankar S S, Soultanas P, Dillingham M S, Subramanya H S, Wigley D B. Crystal structures of complexes of PcrA DNA helicase with a DNA substrate indicate an inchworm mechanism. Cell. 1999;97:75–84. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80716-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Walker J E, Saraste M, Runswick M J, Gay N J. Distantly related sequences in the alpha- and beta-subunits of ATP synthase, myosin, kinases and other ATP-requiring enzymes and a common nucleotide binding fold. EMBO J. 1982;1:945–951. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1982.tb01276.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Weinreich M, Liang C, Stillman B. The Cdc6p nucleotide-binding motif is required for loading mcm proteins onto chromatin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:441–446. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.2.441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zeikus J G, Wolfe R S. Methanobacterium thermoautotrophicus sp. n., an anaerobic, autotrophic, extreme thermophile. J Bacteriol. 1972;109:707–715. doi: 10.1128/jb.109.2.707-713.1972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zylicz M, LeBowitz J H, McMacken R, Georgopoulos C. The dnaK protein of Escherichia coli possesses an ATPase and autophosphorylating activity and is essential in an in vitro DNA replication system. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1983;80:6431–6435. doi: 10.1073/pnas.80.21.6431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]