Abstract

Background

Evidence‐based assessments for people with aphasia (PWA) in Greek are predominantly impairment based. Functional communication (FC) is usually underreported and neglected by clinicians. This study explores the adaptation and psychometric testing of the Greek (GR) version of The Scenario Test. The test assesses the everyday FC of PWA in an interactive multimodal communication setting.

Aims

To determine the reliability and validity of The Scenario Test‐GR and discuss its clinical value.

Methods & Procedures

The Scenario Test‐GR was administered to 54 people with chronic stroke (6+ months post‐stroke): 32 PWA and 22 stroke survivors without aphasia. Participants were recruited from Greece and Cyprus. All measures were administered in an interview format. Standard psychometric criteria were applied to evaluate reliability (internal consistency, test–retest, and interrater reliability) and validity (construct and known‐groups validity) of The Scenario Test‐GR.

Outcomes & Results

The Scenario Test‐GR shows high levels of reliability and validity. High scores of internal consistency (Cronbach's α = 0.95), test–retest reliability (intra‐class coefficients (ICC) = 0.99), and interrater reliability (ICC = 0.99) were found. Interrater agreement in scores on individual items ranged from good to excellent levels of agreement. Correlations with a tool measuring language function in aphasia, a measure of FC, two instruments examining the psychosocial impact of aphasia and a tool measuring non‐verbal cognitive skills revealed good convergent validity (all ps < 0.05). Results showed good known‐groups validity (Mann–Whitney U = 96.5, p < 0.001), with significantly higher scores for participants without aphasia compared with those with aphasia.

Conclusions & Implications

The psychometric qualities of The Scenario Test‐GR support the reliability and validity of the tool for the assessment of FC in Greek‐speaking PWA. The test can be used to assess multimodal FC, promote aphasia rehabilitation goal‐setting at the activity and participation levels, and be used as an outcome measure of everyday communication abilities.

Keywords: functional communication assessment, people with aphasia (PWA), The Scenario Test‐GR, tool validation

WHAT THIS PAPER ADDS

What is already known on the subject

FC assessments aim to investigate whether PWA are effective communicators despite language impairments. The Scenario Test examines the ability of a person with aphasia to convey a message in an interactive multimodal communication setting using daily life situations.

What this paper adds to existing knowledge

This paper describes the adaption of the UK version of The Scenario Test into Greek (GR) for use with Greek‐speaking PWA and provides evidence of the reliability and validity of the tool.

What are the potential or actual clinical implications of this work?

The psychometric properties of The Scenario Test‐GR are consistent with the psychometric qualities of the Dutch Scenario Test and The Scenario Test UK. The Scenario Test‐GR is a very useful clinical tool for examining FC abilities, to guide patient‐centred therapy and goal‐setting, and to measure the efficiency of multimodality and interactivity.

INTRODUCTION

Functional communication (FC) is the basic act of human communication in everyday situations (Elman & Bernstein‐Ellis, 1999). The theoretical definition of FC defines communication as situated language use. Situated language use was initially described by Clark (1996), who outlined the three core characteristics of FC as being interactive, multimodal and based on context (common ground). Recently, Doedens and Meteyard (2019) extended Clark's (1996) definition by elaborating further on the characteristics of FC, as follows: FC is a joint activity between two people (interactive) in which multiple interdependent channels of communication are integrated into a single combined message (multimodal), and that it is reliant on shared knowledge between speakers, the physical environment and the communicative environment (contextual). More recent studies (Charalambous & Kambanaros, 2021; Doedens & Meteyard, 2019; Pierce et al., 2019) reveal that for people with aphasia (PWA) to be successful communicators in everyday situations, they need a supportive environment and a partner who is willing to prompt and support communication. For this study, the word ‘functional’ implies communication which is spontaneous and independent in a supportive communicative environment.

For PWA conversational breakdown is the key impairment that characterizes the aphasic disorder (Doedens et al., 2021). The ability to communicate ‘functionally’ after stroke is crucial for the person with aphasia and the people around them (Schumacher et al., 2020). PWA experience difficulties in spontaneously and independently communicating their needs and engaging in shared interactions (Doedens et al., 2021). They may appear to be communicating, however interactions with others are not always meaningful, effective and satisfying (Koleck et al., 2017). Experiencing consistent challenges in activities of daily living (Manning et al., 2019), due to persisting communication difficulties, may result in social isolation and poor quality of life (QOL) (Hoover et al., 2020). Restrictions in FC reduce access to health and social services, and participation in social and cultural events, and family activities (Azios et al., 2021; Doedens et al., 2021). Being able to engage in FC allows PWA to have a better sense of self, and minimizes mental health issues and isolation (Berg et al., 2020).

Aphasia assessments within the ICF framework

Evidence‐based aphasia assessment when described within the framework of the International Classification on Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF; WHO, 2001) is categorized into three domains: impairment, activity and participation (Table 1). Impairment‐based aphasia assessment aims to evaluate verbal output, auditory comprehension, reading and writing abilities (Mitchell et al., 2020). The activity and participation examination focuses on the assessment of the degree to which aphasia influences the involvement in activities and participation of life events of PWA (Schumacher et al., 2020). Contextual factor assessments include determining the barriers in participating in family, community, and social events due to personal and environmental factors (psychosocial) that are mainly examined using patient‐reported outcome (PROM) questionnaires (Perin et al., 2020).

TABLE 1.

Evidence‐based aphasia assessments and the ICF domains

| ICF domain aphasia related tools | |

|---|---|

| Impairment (language‐based assessments) |

Boston Diagnostic Aphasia Examination (BDAE; Goodglass & Kaplan, 1972) Comprehensive Aphasia Test (CAT; Swinburn et al., 2004); Western Aphasia Battery—Revised Aphasia Quotient (WAB‐R AQ; Kertesz, 2006) |

| Activity and participation (functional communication assessments) |

Amsterdam Nijmegen Everyday Language Test (ANELT; Blomert et al., 1994) Communicative Effectiveness Index (CETI; Lomas et al., 1989) Functional Communication Profile (FCP; Sarno, 1969) Communicative Abilities of Daily Living Test (CADL; Holland, 1980) American Speech and Hearing Association Functional Assessment of Communication Skills for Adults (ASHA‐FACS; Frattali et al., 1995) The Scenario Test (van der Meulen et al., 2010) |

| Contextual factors (quality of life and psychosocial assessments) |

Stroke and Aphasia Quality of Life (SAQOL‐39; Hilari et al., 2003) Assessment of Living with Aphasia (ALA; Simmons‐Mackie et al., 2014) Aphasia Impact Questionnaire (AIQ‐21; Swinburn et al., 2018) |

FC assessment

FC assessment is a more recently used primary outcome measure in large‐scale randomized control trials (Schumacher et al., 2020). The aim of FC assessment is to investigate if PWA are effective communicators and whether they can participate in real‐life situations, despite language impairments (Brady et al., 2016; Dipper et al., 2020). FC assessments should integrate an in‐depth analysis of the individual's communication opportunities, environment and contextual support (Doedens et al., 2021). Speech and language therapists (SLTs) largely assess the linguistic deficits of PWA with formal testing at the impairment level of the ICF without exploring their overall communication efficiency and success (Doedens & Meteyard, 2019). When assessing FC, examiners need to consider two important factors: first, the multimodality of communication used during the assessment; and second, the methods for prompting the response by the examiners (van der Meulen et al., 2010). In a recent study, Schumacher et al. (2020) argued that examiners should also look beyond the linguistic profile of the person with aphasia when assessing FC, by investigating the non‐verbal cognitive abilities of the individual. Non‐verbal cognition is particularly crucial in FC assessment of individuals with limited verbal output due to aphasia because it can play a significant role on the person's ability to communicate effectively (Schumacher et al., 2020).

The ROMA‐COS guidelines by Wallace et al. (2019) are highly related to our study since guidelines propose the use of The Scenario Test and the Communication Effectiveness Index (CETI) for the assessment of FC in PWA. According to the ROMA‐COS consortium, based on consensus, the tools met the stipulated feasibility criteria as follows: (1) the tools are available in different languages; (2) the cost of the tools; (3) the ease of administration and the completion time of the outcome measure; and (4) the straightforwardness in calculating total score.

As Worrall et al. (2002) have identified, it is unrealistic to expect a single assessment to be fitting to assess all PWA, all cultures, all impairments and in all settings. Nevertheless, FC assessment tools attempt to bridge the domains of the ICF by assessing the communication skills of the person with aphasia in a multimodal way. Given the importance of communication for active involvement, life satisfaction and higher QOL, there is a gap in the current literature for the FC assessment of Greek‐speaking PWA. To quantify and assess communication performance in real‐life settings, a valid tool of FC for Greek‐speaking PWA is needed.

The Scenario Test

The Scenario Test is a standardized tool that assesses FC in PWA initially developed in the Netherlands by van der Meulen et al. (2010). It was designed for PWA whose communication ability is severely impaired or entirely disrupted (van der Meulen et al., 2010). It examines the ability to convey a message whether it is verbal or non‐verbal in an interactive communication setting using daily life situations. ‘Interactive setting refers to the active role of the examiner, who provides communicative support’ (Van der Meulen et al., 2010: 426). The Scenario Test is available in Dutch (van der Meulen et al., 2010), English (Hilari et al., 2018) and German (Nobis‐Bosch et al., 2020). The test was adapted from the Amsterdam Nijmegen Everyday Language Test (ANELT; Blomert et al., 1994) because it measures FC in daily‐life situations in PWA with different degrees of severity. What makes The Scenario Test unique is the introduction of two new aspects in FC assessment: (1) it measures multimodal communication; and (2) provides an interactive setting with the examiner being an active communication partner prompting responses.

The Scenario Test was culturally adapted by Hilari et al. (2018) into English. The Scenario Test UK (Hilari & Dipper, 2020), like the original test, consists of 18 items/scenarios that represent daily life situations using black‐and‐white drawings to support comprehension. Hilari et al. (2018) designed a new set of black‐and‐white images, which were reviewed and approved by the Dutch developers, that included six real‐life scenarios representing: (1) shop, (2) taxi, (3) general practitioner (GP), (4) visit, (5) housekeeper and (6) restaurant. Scores for each item range from 0 to 3, with 0 being a poor answer despite help and support, and 3 for giving an independent correct answer without help (see Table 2 for scoring). Explicit information on scoring items with one or more concepts are given in the test's manual (Hilari & Dipper, 2020).

TABLE 2.

Scoring of the items

| Score | Response |

|---|---|

| 3 | Correct answer without help |

| 2 | Response with prompt 1; stimulation of the use of a different mode of communication |

| 1 | Response with prompt 2; yes/no questions answered correctly |

| 0 | Not all yes/no questions answered correctly |

The scores of the test range from 0 to 54, with higher scores indicating better FC performance. The examiner presents each scenario verbally, is willing to provide support (e.g., prompts to draw or sign), and encourages individuals to switch to different communication modes to respond using total communication techniques (gestures to speech, pointing, writing, drawing).

The Scenario Test provides additional qualitative information about: (1) the type (verbal, gestures, pointing, writing, drawing) and frequency (sometimes, often, only) of the communication mode; (2) the effectiveness of non‐verbal communication (not, sometimes, only); (3) the flexibility in switching communication mode (never, some after help, some spontaneous, often after help, often spontaneous); (4) the comprehension of the scenarios (poor, reasonable, good); and (5) the amount (none, sometimes, often) and type of help (open ended questions, closed questions) needed from the examiner.

Aims

We acknowledge the lack of a standardized tool in the Greek language for measuring FC in patients with aphasia in the chronic stage. The English version of The Scenario Test was adapted for use in Greece and Cyprus (The Scenario Test‐GR) and this study aimed to evaluate the reliability (internal consistency, test–retest and interrater reliability) and construct validity (convergent and known‐groups validity) of The Scenario Test‐GR against standard psychometric criteria and report on its significant clinical value.

METHOD AND MATERIALS

The Scenario Test‐GR

This study examines the adaptation and validation of The Scenario Test‐GR based on The Scenario Test UK version (Hilari & Dipper, 2020). At the outset, the authors received written permission from Professor Katerina Hilari and Dr Lucy Dipper and the UK publisher (J&R Press Ltd, Guildford, UK) to translate, adapt and validate The Scenario Test (validated in the UK in 2020) into Greek. The reason for choosing the UK version compared with the original Dutch version (van der Meulen et al., 2010) was the ease of translating and back‐translating from English into Greek by the research team as two authors (MC and MK) are Greek–English bilinguals. Adapting and validating The Scenario Test‐GR involved translating and adapting the test manual (administration instructions on how to score and interpret responses) and the scoring sheets of The Scenario Test UK (Hilari et al., 2018) into Standard Modern Greek. Standard Modern Greek is one of the two official languages of the Republic of Cyprus (the other being Turkish) (Fotiou & Grohmann, 2022). Specifically, ‘the Greek‐speaking community in Cyprus is diglossic: Standard Modern Greek is the High variety, while Cypriot Greek—the mother tongue of Greek Cypriots—is the Low variety’ (Fotiou & Grohmann, 2022: 1). Standard Modern Greek is the socio‐linguistically High variety in Cyprus which is acquired at school, and it is the variety people use in formal written and oral communication. Cypriot Greek, which is the mother tongue of Greek Cypriots, is the Low variety and is used in informal interactions (Fotiou & Grohmann, 2022). For this reason, the test manual and scoring sheets were translated into Standard Modern Greek by an academic linguist from the Linguistics Department of the University of Cyprus and then back‐translated into English by the two main authors (MC and MK), with excellent correspondence to the original source. Finally, the Greek documents were compared and revised again by the two main authors (MC and MK) until a consensus was met for the final version. For example, in the initial translation the word πελάτης /pe′latis/ for ‘client’ was replaced with ασθενή /asθe′ni/ and the word παθολόγος /paθo′loɣos/ for ‘GP’ was replaced with γιατρό /ja′tro/, which are more culturally appropriate in Greece and Cyprus and easier terms for PWA to comprehend.

Pilot study

A pilot study was conducted to check the acceptability of the Greek version of the questions based on time of administration, completion rates and score distributions. The pilot sample consisted of 10 people with chronic stroke (6+ months post‐stroke), five with aphasia and five without, recruited from the Cyprus Stroke Association (CSA) Registry. The Scenario Test‐GR was administered to all participants in one session with an average administration time of 20 min. No problems were reported during administration. Participants’ mean (SD) score on the measure was 46.0 (8.23), with a range of 28–54, where 0 was the lowest score and 54 was the maximum. The pilot study resulted in a wide range of scores for both groups as expected, and therefore the researchers proceeded with the psychometric testing of the tool.

Design

A cross‐sectional study was carried out to evaluate objectively the psychometric properties of The Scenario Test‐GR.

Participation criteria

Participants were eligible to participate in the study if they met the pre‐established inclusion criteria: (1) to be native Greek speakers, (2) age ≥ 18 years, (3) to have suffered a stroke at least 6 months prior to the study (chronic phase), and (4) to present with aphasia due to stroke as diagnosed by SLT services during rehabilitation. Participants were excluded if they presented with (1) an additional diagnosis of dementia or any other degenerative disease, (2) profound hearing impairment and/or visual difficulties that would interfere with their performance in the study or (3) unilateral spatial neglect (USN) as detected with the Albert's Test (Fullerton et al., 1986), and (4) a medical diagnosis of clinical depression or any other mental condition. The above‐mentioned criteria were established to ensure that any language or FC deficits were due to stroke or aphasia rather than cognitive or sensory impairments. Hearing, vision and medical history were determined by observation, self‐report and/or reports from the carer during the case history interview.

Recruitment

Participants were recruited from both Greece and Cyprus. Recruitment sources were the CSA Registry, The Aphasia Communication Team (TACT) run by the CSA and by the Rehabilitation Clinic of the Cyprus University of Technology (CUT), Melathro Agoniston EOKA (MAE) Neurorehabilitation Center in Limassol, Limassol General Hospital Stroke Registry, private rehabilitation and neurology clinics in Nicosia and Athens, and private speech–language therapy clinics/offices in Cyprus and Greece. A total of 83 participants were referred to this study between September 2020 and May 2021, with 29 (35%) later dropping out of the study (see Table 3 for reasons).

TABLE 3.

Reasons for dropping out of the study (n = 29)

| Reasons for drop out | Numbers dropping out |

|---|---|

| Unknown | 7 |

| Could not make contact | 8 |

| Refused to complete the study protocol | 3 |

| Refused home visits due to the COVID‐19 pandemic | 7 |

| Did not give consent | 2 |

| Illness | 2 |

Participants

A total of 32 people with stroke‐induced aphasia and 22 stroke survivors without aphasia took part in the study (n = 54 participants in total). This sample size is considered to be sufficient for the scope of the research compared with previous sample sizes for validation of The Scenario Test based on population and prevalence of strokes (Table 4).

TABLE 4.

Sample size of The Scenario Test‐GR based on former versions and data from the Burden of Stroke report in Europe (Wafa et al., 2020)

| Country | Population | Incidence estimate | The Scenario Test, sample size (n) |

|---|---|---|---|

| The Netherlands | 17,100,300 | 33,000 strokes/year |

n = 147 122 PWA + 25 stroke survivors without aphasia |

| UK | 65,542,579 | 106,000 strokes/year |

n = 94 74 PWA + 20 stroke survivors without aphasia |

| Greece plus Cyprus | 11,606,813 + 803,147 | 28,000 + 1000 strokes/year |

n = 54 32 PWA + 22 stroke survivors without aphasia |

Out of the 54 participants, 23 (42.6%) were female and 31 (57.4%) were male. Participants’ age ranged between 20 and 86 years (mean = 54.3, SD = 17.3). The average time post‐onset since diagnosis was 50.7 months (SD = 55.6), ranging between 6 and 264 months, indicating that all participants were in the chronic phase post‐stroke. All participants were Greek native speakers with no visual or hearing problems that could interfere with the study's protocol. Details regarding the participants’ demographic data are presented in Table 5.

TABLE 5.

Demographic data for participants with and without aphasia after stroke

| Characteristic | People with aphasia (n = 32) | Stroke survivors without aphasia (n = 22) |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 20 (62.5%) | 11 (50%) |

| Female | 12 (37.5%) | 11 (50%) |

| Age | ||

| Mean (SD) | 54.3 (17.3) | 59.7 (16.8) |

| Range | 20–83 | 22–86 |

| Stroke type | ||

| Ischemic | 16 (50%) | 10 (45.5%) |

| Haemorrhagic | 16 (50%) | 12 (54.5%) |

| Lesion location | ||

| Left | 26 (81.5%) | 5 (23%) |

| Right | 5 (15.5%) | 13 (59%) |

| Unknown | 1 (3%) | 4 (18%) |

| Hemiparesis | ||

| Left | 5 (25%) | 11 (50%) |

| Right | 19 (60%) | 2 (10%) |

| None | 8 (15%) | 9 (40%) |

| Months post‐stroke diagnosis | ||

| Mean (SD) | 50.7 (55.6) | 54 (71.2) |

| Range | 6–264 | 12–252 |

| Completed education | ||

| Primary | 2 (6%) | 2 (9%) |

| Secondary | 20 (63%) | 12 (54.5%) |

| College | 0 (0%) | 2 (9%) |

| Bachelor's | 9 (28%) | 5 (23%) |

| Master's | 1 (3%) | 0 (0%) |

| Doctoral | 0 (0%) | 1 (4.5%) |

| Marital status | ||

| Married | 19 (60%) | 14 (64%) |

| Single | 10 (31%) | 4 (18%) |

| Divorced | 3 (9%) | 2 (9%) |

| Widowed | 0 (0%) | 2 (0%) |

| Socio‐economic status based on former occupation | ||

| Higher managerial | 13 (40.5%) | 5 (23%) |

| Intermediate occupation | 5 (15.5%) | 7 (32%) |

| Manual occupation | 6 (19%) | 6 (27%) |

| Unemployed | 8 (25%) | 4 (18%) |

Procedures and measures

For the validation of The Scenario Test‐GR ethical approval was obtained from the Cyprus National Bioethics Committee (EEBK/ΕΠ/2017/37). Administration of the test, and all other assessments, took place either at the participant's home or in private clinics/offices. Testing was carried out by qualified and certified Greek‐speaking SLTs experienced in aphasia rehabilitation. The study employed four SLTs who all received training by the first author (MC) on the administration of The Scenario Test in Greek prior to study commencement. Informed consent was obtained from each participant at the start of the study. Specifically, for PWA simplified information about the project was given in an aphasia‐friendly format with an additional aphasia‐friendly consent form for video and audio recording. Assessments were completed in two sessions of approximately 1–1.5 h each. Test–retest reliability of The Scenario Test‐GR was evaluated with an additional session of about 20 min after a 7–14‐day interval from the first administration. For video filming, a spatially stable setting was chosen where the camera as a fixed observer was registering the course of the interaction between the examiner/examinee (Ramey et al, 2016).

While taking into consideration the limited options in the availability of validated tools in Greek, a selection of measures related to the validation of The Scenario Test‐GR included language, communication, aphasia impact and psychosocial assessments (e.g., QOL) and non‐verbal cognition. All these parameters interact strongly with FC, as discussed in the introduction. Therefore, the following measures were administered:

The Aphasia Severity Rating Scale (ASRS), of the Greek adaptation of the Boston Diagnostic Aphasia Examination Short Form (BDAE‐SF; Messinis et al., 2013). The ASRS was used to rate the severity of the observed language difficulties. Spontaneous speech samples were elicited during a 15‐min semi‐structured interview that comprised four topics: illness, previous/current occupation, family and housing, and hobbies (El Hachioui et al., 2013). Aphasia severity was assessed by the interviewer using the ASRS to allow a classification based on fluency and intelligibility. Scores on the ASRS range from 0 to 5, with 5 indicating very mild aphasic symptoms (‘minimal discernible speech handicap’) and 0 revealing very severe non‐fluent aphasia (‘no usable speech or auditory comprehension’).

The Greek adaptation of the Communicative Effectiveness Index (CETI; Constanti, 2020). CETI measures changes in communicative behaviours in everyday life situations of a person with aphasia. It is an indirect communication measure comprising 16 communication situations for which a significant other (relative/carer) of the person with aphasia is asked to rate the individual's performance using a 6‐point rating scale. Ratings range from 0 to 5, where 0 is ‘total inability to perform’ the task and 5 being ‘able to perform as before’. Scores range from 0 to 64, with higher scores indicating better FC in everyday situations.

The Greek adaptation of the Aphasia Impact Questionnaire (AIQ‐21; Anthimou et al., 2020). The AIQ‐21 is a subjective outcome measure that addresses how a PWA experiences life with aphasia. It consists of 21 items about communication, participation and well‐being/emotional state. A PWA answers each item using a 5‐point scale (0–4). Total scores range from 0 to 84, with higher scores indicating higher impact of aphasia.

The Greek version of the Stroke and Aphasia Quality of Life (SAQOL‐39; Efstratiadou et al., 2012). The SAQOL‐39‐GR is a questionnaire that measures the QOL of PWA. It consists of 39 items that cover three domains: physical, communication and psychosocial. Each item has a 5‐point scale (1–5), and mean scores range from 1 to 5, with higher scores indicating better QOL. The purpose of comparing The Scenario Test results with the SAQOL‐39 was to examine the correlation between overall QOL and FC. Comparisons were made on the overall scores of the SAQOL and not on domain specific scores of SAQOL (e.g., the communication domain).

The Ravens Color Progressive Matrices (RCPM; Raven, 2000). The RCPM is a non‐verbal intelligence cognitive assessment that includes a series of 36 pattern schemas that require participants to complete a visual pattern or sequence by selecting one of six possible choices. Scores range from 0 to 36, with higher scores indicating higher non‐verbal cognitive skills. The RCPM relies on visual recognition, spatial perception and categorization abilities (Baldo et al., 2005), all essential for FC abilities (Schumacher at al., 2020).

Psychometric testing and data analysis

Reliability and validity of a test are two properties that indicate its quality and usefulness. Reliability refers to how dependably or consistently a test measures a characteristic and the extent to which a test is free from random error (Hilari et al., 2018). In terms of reliability of The Scenario Test‐GR, we tested internal consistency, test–retest reliability and interrater reliability. Internal consistency indicates the extent to which items of a test measure the same construct (homogeneity). Test–retest reliability is the repeatability of test scores at a different point in time; interrater reliability measures the degree of agreement of the test being scored by different raters/clinicians (McHugh, 2012).

Validity states how accurately a tool measures what it claims to measure (Taherdoost, 2016). Construct validity ensures that the instrument matches and represents the characteristic/construct undergoing measurement. The following aspects of construct validity were tested: convergent validity and known groups validity. Convergent validity refers to how closely an instrument relates to other measures of the same construct (Taherdoost, 2016). Lastly, known‐groups validity determines that an instrument can demonstrate dissimilar scores among different groups. We did not proceed with a discriminant validity test (Hilari et al., 2018) since there is lack of suitable validated tools for the Greek‐speaking population to test gesture recognition or similar skills.

Testing of reliability

Specifically, 39 (72%) participants (27 with aphasia, 12 without aphasia) were engaged in the test–retest reliability by completing The Scenario Test‐GR for a second time in a 7–14‐day interval after the first administration. During the interrater reliability phase, three of the four administrators were involved as second raters, who watched and rescored the results from 14 out of the 54 videos (26%) of participants in both groups (seven PWA and seven without aphasia).

Testing of validity

In terms of convergent validity four hypotheses were formulated. (1) Scores of The Scenario Test‐GR will significantly correlate with measures of language, that is, ASRS in BDAE‐SF. Previous studies have shown a close association between language impairments after stroke and FC (Blom‐Smick et al., 2017; Hilari et al., 2018; Irwin et al., 2006). (2) Moderate to high correlation is expected for the CETI as it assesses FC, even though it is rated by a relative of the PWA and not by the participant (van der Meulen et al., 2010). (3) The Scenario Test will correlate moderately with RPCM non‐verbal cognitive measure (Olsson et al., 2019). According to Schumacher et al. (2020) there is strong evidence on the importance of assessing non‐verbal cognition when language production is impaired in PWA during FC assessments. (4) Scores of The Scenario Test‐GR will significantly correlate with measures of the psychosocial domain (SAQOL‐39 and AIQ‐21) as there is evidence for links between low FC with poor QOL (Doedens & Meteyard, 2019; Doedens et al, 2021). For known groups validity we hypothesized that stroke survivors without aphasia would have higher scores on The Scenario Test‐GR than PWA.

Criteria for psychometric testing

The following criteria were used to test the reliability and validity of The Scenario Test‐GR. Cronbach’ α > 0.70 indicates good internal consistency (Nunnally & Bernstein, 1994). Similar to previous studies measuring the psychometric properties of The Scenario Test, a rounded Cronbach's α ≥ 0.8 was considered excellent (Hilari et al., 2018). Intra‐class correlations coefficients (ICC) ≥ 0.80 indicate good interrater reliability of the overall measure (Streiner et al., 2014); ICCs should be ≥ 0.75 for good test–retest reliability (Streiner et al., 2014). Correlational analysis (Spearman's rho) was undertaken to test the convergent validity of the measure. Commonly in psychometric testing (Akoglu, 2018), correlations between 0 < ρ < 0.3 or –0.3 < ρ < 0 are considered weak, between 0.4 < ρ < 0.6 or –0.6 < ρ < –0.4 moderate, and ρ > 0.6 or ρ < –0.6 strong. Lastly, the non‐parametric Mann–Whitney U‐test was used to compare The Scenario Test‐GR scores of those with aphasia versus those without, for known‐groups validity.

RESULTS

Measure scores

The descriptive data of the scores for each measure for PWA and stroke survivors without aphasia are presented in Table 6. Notably, the mean score of PWA on The Scenario Test‐GR was 37.6 (SD = 13.4), while the mean score of stroke survivors without aphasia was 51.7 (SD = 2.51).

TABLE 6.

Scores on The Scenario Test and other measures for stroke survivors with and without aphasia

| Measure | People with aphasia (n = 32) | People without aphasia (n = 22) |

|---|---|---|

| The Scenario Test‐GR | ||

| Mean (SD) | 37.6 (13.4) | 51.7 (2.51) |

| Medial (IQR) | 40.5 (24.8–49.3) | 53 (50–54) |

| Minimum–maximum | 12–54 | 47–54 |

| ASRS BDAE‐SF | ||

| Mean (SD) | 2.72 (1.42) | n.a. |

| Median (IQR) | 3 (1–4) | |

| Minimum–maximum | 1–5 | |

| RCPM | ||

| Mean (SD) | 22.2 (8.48) | 25 (7.66) |

| Median (IQR) | 23.5 (18.3–28) | 26 (21–24) |

| Minimum–maximum | 1–36 | 12–36 |

| CETI | ||

| Mean (SD) | 36.3 (15.2) | n.a. |

| Median (IQR) | 37 (28.3–47.3) | |

| Minimum–maximum | 8–64 | |

| AIQ | ||

| Mean (SD) | 35.4 (16.2) | n.a. |

| Median (IQR) | 37 (23.8–43.5) | |

| Minimum–maximum | 5–69 | |

| SAQOL | ||

| Mean (SD) | 3.48 (0.54) | n.a. |

| Median (IQR) | 3.54 (3.11–3.88) | |

| Minimum–maximum | 2.3–4.44 | |

ASRS BDAE‐SF = Aphasia Severity Rating Scale Boston Diagnostic Aphasia Examination—Short Form; CETI = Communication Effectiveness Index; PCRM = Ravens Color Progressive Matrices; AIQ‐21 = Aphasia Impact Questionnaire; SAQOL‐39 = Stroke and Aphasia Quality of Life.

Reliability analyses

Internal consistency

Internal consistency for The Scenario Test‐GR was calculated using Cronbach's α coefficient for all items amongst the 54 participants. High internal consistency was found (α = 0.95), indicating that The Scenario Test‐GR has excellent internal consistency. Item‐rest correlations ranged between 0.46 and 0.86 (mean = 0.70, SD = 0.12) with four items falling below 0.6 (items 1a, 1b, 2b and 4a).

Test–retest reliability

To examine test–retest reliability, a second session was repeated 7–14 days after the initial scoring for 39 (72%) participants (27 with aphasia, 12 without aphasia). The ICC was found to be high (ICC = 0.99), providing an indication of excellent test–retest reliability. To account for possible ceiling effects from participants without aphasia, we repeated the analysis only for the 27 participants (50%) with aphasia, and similarly found excellent test–retest reliability (ICC = 0.98).

Interrater reliability

Lastly, interrater reliability was tested for 14 participants with aphasia (25%), across three raters. Interrater reliability for the total scores was also found to be high (ICC = 0.99), while the reliability of each item fell within a good to excellent level of agreement (Kappa range = 0.43–1) (Table 7).

TABLE 7.

Interrater level of agreement for each item across three raters

| Item | Kappa | Significance | Agreement level |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1a | 0.708 | < 0.001 | Good |

| 1b | 0.649 | < 0.001 | Good |

| 1c | 0.716 | < 0.001 | Good |

| 2a | 0.770 | < 0.001 | Excellent |

| 2b | 0.918 | < 0.001 | Excellent |

| 2c | 1 | < 0.001 | Excellent |

| 3a | 0.877 | < 0.001 | Excellent |

| 3b | 0.749 | < 0.001 | Excellent |

| 3c | 0.552 | < 0.001 | Good |

| 4a | 0.676 | < 0.001 | Good |

| 4b | 0.458 | < 0.001 | Good |

| 4c | 0.795 | < 0.001 | Excellent |

| 5a | 1 | < 0.001 | Excellent |

| 5b | 0.515 | < 0.001 | Good |

| 5c | 0.425 | < 0.001 | Good |

| 6a | 0.780 | < 0.001 | Excellent |

| 6b | 0.838 | < 0.001 | Excellent |

| 6c | 1 | < 0.001 | Excellent |

Validity analyses

Construct validity

To explore the validity of The Scenario Test‐GR, we tested correlations between measures of language, communication and psychosocial factors. The non‐parametric Spearman's ρ was used to calculate the correlation coefficient. As shown in Table 6, correlations with other measures were moderate to high (Spearman's ρ range = 0.36–0.71). Notably, The Scenario Test‐GR correlated strongly (p < 0.001) with other measures of language such as the ASRS BDAE‐SF and FC, that is, the CETI (Table 8).

TABLE 8.

Convergent validity of The Scenario Test‐GR for participants with aphasia

| The Scenario Test | ASRS BDAE‐SF | CETI | RCPM | AIQ‐21 | SAQOL‐39 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ρ | 0.59** | 0.71** | 0.36* | –0.56** | 0.43* |

| n | 32 | 32 | 53 | 32 | 32 |

Notes: ** p ≤ 0.01;

* p ≤ 0.05.

ASRS BDAE‐SF = Aphasia Severity Rating Scale Boston Diagnostic Aphasia Examination‐ Short Form; CETI = Communication Effectiveness Index; PCRM = Ravens Color Progressive Matrices; AIQ‐21 = Aphasia Impact Questionnaire; SAQOL‐39 = Stroke and Aphasia Quality of Life.

Known‐groups validity

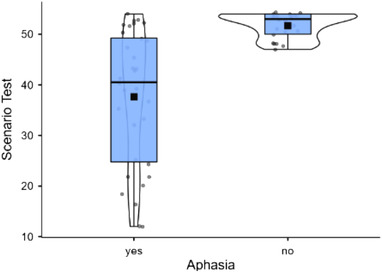

Further, the non‐parametric Mann–Whitney U‐test was used to investigate known‐groups validity. The use of non‐parametric testing was necessary since data normality was violated, as tested with the Shapiro–Wilk normality test (W = 0.93, p = 0.003). The scores of participants without aphasia (median [interquartile range—IQR] = 53 [50–54]) were significantly higher compared with the scores of participants with aphasia (40.5 [24.8–49.3]; Mann–Whitney U = 96.5, p < 0.001), indicating good known‐groups validity for The Scenario Test‐GR. In Figure 1, the black line indicates the median, while the black square shows the mean for PWA (left) or without aphasia (right). The grey dots indicate individual scores for each participant.

FIGURE 1.

Violin plot of The Scenario Test‐ GR scores for people with and without aphasia [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

DISCUSSION

In the current study we adapted The Scenario Test‐GR, a tool developed to evaluate FC of Greek‐speaking PWA, using daily life situations within an interactive communication setting. Respondents were encouraged to use total communication, while an experienced examiner actively provided support.

The quantitative results of this study fully support the reliability and validity of The Scenario Test‐GR's adaptation. In terms of reliability, the test demonstrated significantly high internal consistency, test–retest reliability and interrater reliability. The high evidence of reliability of the Greek adaptation of the test is consistent with the findings for the Dutch and English versions of the test (Table 9).

TABLE 9.

Reliability scores for the Dutch, UK and Greek versions

| The Scenario Test version | Internal consistency (Cronbach's α) | Test–retest reliability ICC | Interrater reliability ICC |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dutch | 0.96 | 0.98 | 0.90 |

| UK | 0.92 | 0.96 | 0.95 |

| Greek | 0.95 | 0.99 | 0.99 |

Note: ICC = interclass correlation coefficient.

Between raters' item agreement was analysed in detail. Items 2a, 2b, 2c (complete “‘Taxi scenario’”), 3a and 3b (subparts of the “‘GP’” scenario), 4c (subpart of the ‘Visit’ scenario), 5a (subpart of the ‘Housekeeper’ scenario), and 6a–6c (complete ‘Restaurant’ scenario) had excellent levels of agreement. All the remaining items, including the first scenario ‘Shop’, showed good level of agreement. None of the items showed poor levels of agreement between raters for The Scenario Test‐GR. Data from all three studies (Dutch: van der Meulen et al., 2010; UK: Hilari et al., 2018; Greek: current study) indicate that (1) all test's items measure the same construct, (2) raters who have received training prior to administration do achieve high levels of score agreement and (3) The Scenario Test is a constant measure of FC over a 7–14‐day interval.

In terms of validity, The Scenario Test‐GR correlated moderately to high with measures of oral productive language, communication, non‐verbal cognition and psychosocial domains. The UK adaptation of The Scenario Test study used the Frenchay Aphasia Screening Test (FAST; Enderby et al., 1987) to measure aphasia and the American Speech and Hearing Association Functional Assessment of Communication Skills for Adults (ASHA‐FACS; Frattali et al., 1995) to measure FC. The original Dutch study of The Scenario Test used the Amsterdam Nijmegen Everyday Language Test (ANELT; Blomert et al., 1994) and the Aachen Aphasia Test (AAT; Graetz et al., 1991) to assess language and the CETI for FC. In this study the ASRS of the BDAE‐SF was used to measure aphasia severity and the CETI was used to measure FC.

The Scenario Test‐GR demonstrated high correlation with the ASRS in BDAE‐SF (ρ = 0.59, p < 0.001), which assesses the severity of aphasia on an impairment level of the ICF (language skills) for PWA. It is important to mention that 20/32 of the participants with aphasia (62.5%) had a lower score than 3 on the BDAE‐SF: 10/32 scored 1 (31.25%), 4/23 scored 2 (12.5%) and 6/23 scored 3 (18.75%). Scores below 3 on the ASRS BDAE‐SF suggest moderate to severe language impairments or absence of speech, indicating limited abilities to effectively convey a message (Goodglass & Kaplan, 1972). While our sample had low ASRS scores on the BDAE‐SF, participants performed higher on The Scenario Test‐GR. This is evident because PWA were provided with additional verbal support such as open‐ended and/or close questions, prompts to use gestures, write, and draw, and constant encouragement to switch communication modes and respond using total communication techniques by a very animated examiner.

The Scenario Test‐GR also demonstrated high correlation with the CETI, which also measures FC for PWA (Lomas et al., 1989) based on the activity and participation level of the ICF. For this study it was hypothesized that correlation for the CETI will be moderate to high since it is based on the carer's view of communication abilities of the person with aphasia and not the views of the affected person. However, the CETI is an indirect measure, reflecting rates based on a familiar person/carer. Though, the views of PWA about their communication abilities often mismatch those of their careers or family members (Worrall et al., 2011). Nevertheless, measures of the CETI in both studies, Dutch (ρ = 0.50, p < 0.01) and Greek (ρ = 0.71, p < 0.001), were positively correlated with The Scenario Test (van der Meulen et al., 2010).

The Scenario Test‐GR had higher correlation with the CETI than with the ASRS in BDAE‐SF. This is in line with our expectations, since the CETI questionnaire measures FC, compared with the ASRS BDAE‐SF which measures language output at the impairment level of the ICF. Worrall et al. (2011) examined choices in therapy goals for PWA and found that the majority highlighted the importance of participation and social interaction, which are substantially based on FC skills. Hence, tools that assess FC are more efficient and can identify and meet the individual needs of PWA.

The Scenario Test‐GR correlated moderately with a measure of non‐verbal cognitive skills (RCPM) as hypothesized. This correlation shows that FC abilities in PWA does not only depend on their language production difficulties but also on additional non‐verbal cognitive impairments (Schumacher at al., 2020). RCPM relies on many cognitive modules (visual recognition, spatial perception, categorization abilities) (Baldo et al., 2005). Previous studies have supported those non‐verbal cognitive skills are considered very important when language output in PWA is severely affected by their stroke (Baldo et al., 2005; Schumacher at al., 2020). Schumacher et al. (2020) stress the necessity of using more than one measure to capture the full range and multifaceted nature of FC skills in PWA and a therapeutic focus on non‐verbal cognition can have positive effects on this important aspect of activity and participation (WHO, 2001; Kranou‐Economidou & Kambanaros, 2020).

Our fourth hypothesis was that The Scenario Test‐GR would correlate moderately with two measures from the psychosocial domain of the ICF, the AIQ‐21 and the SAQOL‐39. As expected, The Scenario Test‐GR correlated moderately with the AIQ‐21, a subjective questionnaire that addresses how PWA experience their everyday life with aphasia. Several studies have reported the importance of social interaction, event participation and friendships which are negatively affected for people with severe aphasia due to their limited communication abilities (Azios et al., 2021). The hypothesis for the SAQOL‐39 result indicate that QOL is affected by poor communication access (Doedens & Meteyard, 2019). FC skills are fundamental to maintaining a positive QOL for individuals with aphasia (Tarrant et al., 2021). Previous studies (Olsson et al., 2019) have also reported close association between QOL and FC, and how the psychosocial domain is related to FC abilities. Lastly, participants without aphasia scored significantly higher compared with participants with aphasia, suggesting strong evidence for known‐groups validity.

Findings from all three versions of The Scenario Test (Dutch: van der Meulen et al., 2010; UK: Hilari et al., 2018; Greek: current study) support the fact that The Scenario Test is a valid and reliable measure of FC.

Multimodal communication

The communication needs of PWA vary and make the realization of a meaningful and functional assessment challenging (Archer et al., 2020). The Scenario Test‐GR can measure communication skills using any modality, verbal and/or non‐verbal (e.g., gestures, pointing to objects, mimicking, writing down keywords or drawing a picture; van der Meulen et al., 2010). PWA are often dependent on their communication partner to get the message across (Charalambous & Kambanaros, 2021). Communication partners assist PWA to reveal the competence of their skills in using multimodal communication, be it verbal, gestural, written, drawings or use of a communication aid (Pierce et al., 2019). A prompt from a communication partner can help the person with aphasia to switch to a different communication mode and non‐verbal strategies (van der Meulen et al., 2010). Although people with more severe aphasia rely on non–verbal strategies, they often avoid these in daily communication (Lanyon et al., 2018). They also rank themselves lower when assessing their communicative abilities and their performance on The Scenario Test (Schumacher et al., 2020). This might be evident because some PWA tend to underestimate their communication abilities if they are using non‐verbal modes of communication (Schumacher et al., 2020). Therefore, the interactive setting of The Scenario Test‐GR with the active role of the examiner (mimicking a communication partner) is a representative and efficient way to assess the communication skills of people with different severities of aphasia.

Clinical implications

PWA in the chronic stage often acquire several communication strategies, using total communication to build up or compensate on their poor verbal skills (Luck & Rose, 2007; Pierce et al., 2019). Besides the use of verbal output while responding to The Scenario Test‐GR, provides information about the type and frequency of alternative communication modes, the effectiveness and flexibility in switching communication mode and the amount and type of support needed from the examiner. The person with aphasia is allowed to utilize non‐verbal strategies such as hand gestures, point to objects, write down or draw a message, facial expressions or even Augmentative and Alternative Communication (AAC) devices or means (van der Meulen et al., 2010). The prospect and convenience to use AAC while responding to The Scenario Test questions (van der Meulen et al., 2010) gives the tool a major advantage of measuring FC skills for people with severe aphasia, who have limited verbal output or complete absence of speech. This important information can be used to build a functional person‐centred intervention program, measure the effectiveness of an intervention, and provide carer/family counselling in developing communication strategies to support daily communication with the person with aphasia at home and in society.

The Scenario Test‐GR is a unique measure that evaluates FC and allows the exploration of multimodal communication behaviours within a shared communication setting. This tool allows PWA to communicate across real everyday life scenarios, with an interactive examiner who freely role plays with the person with aphasia and provides different levels of feedback and prompts to promote responses while administrating the test.

Limitations of the study

A limitation of this study is that PWA were not involved in the adaptation phase of the test. Their involvement in the co‐production phase (translation of the scenarios and the adaptation of the material in Standard Greek language) would enhance meaningful knowledge and have given a voice to PWA who are often excluded from research as partners, especially on topics such as the creation of functional assessment tools (Charalambous et al., 2020). The involvement of PWA as PPI partners will also optimize the validity and applicability of the research itself and the effectiveness of the resulting tool (Shippee et al., 2013).

In The Scenario Test‐GR PWA are asked to pretend to be in a real‐life situation, while all the scenarios are presented by the examiner on paper. This might be challenging for people with more severe comprehension difficulties, as it requires preserved cognitive abilities and world knowledge (Meier et al., 2017). However, the test includes picture prompts (black‐and‐white illustrations) which support comprehension as well as role play which can ease cognitive demands (Hilari et al., 2018). Another limitation is that The Scenario Test‐GR can show ceiling effects for people with mild to moderate aphasia (Schumacher et al., 2020). The German version of The Scenario Test (Nobis‐Bosch et al., 2020), for example, contains an extension of the scoring scheme to better account for PWA with higher performance in language production.

Hilari et al. (2018) argued that while the examiner is administrating and describing a scenario, he/she provides additional linguistic content regarding the desirable, ‘target’ response. This additional information was spontaneously repeated by the person being assessed. In this study, this behaviour was occasionally observed, especially during the ‘example scenario’ given prior to formal administration. Although sporadically the expected response was included in the description provided by the examiner, this type of ‘answer’ occurred mostly at the beginning of each description. Therefore, since the ‘answer’ was not the last information the client received in the description of the command, it is assumed that this did not affect performance. Nevertheless, in most scenarios, the desirable answer was not mentioned in the description by the examiner. For example, in the fourth scenario ‘Visit’ for the first item, the test asks ‘You are visiting a friend. Your friend asks you: what would you like to drink?’. The expected answer is ‘any drink’. This task requires word retrieval ability and not an ability to repeat words.

Throughout this study it was observed that in the second scenario ‘Taxi’, the second item, 2b, was not culturally equivalent, with respect to all the other items of the test. For this item, the description says ‘Your taxi has arrived. You can sit back. But you prefer to seat at the front seat. What would you do?’. The accepted answer is ‘Front seat’. More than 50% of the participants from both groups answered that they would prefer to sit at the back, a common cultural behaviour practiced in Greece and Cyprus when riding in a taxi.

Finally, although 62.5% of the participants with aphasia presented with moderate to severe aphasia had scored 3 and lower on the ASRS of BDAE‐SF, none of them presented with a 0 score (very severe non‐fluent aphasia). For that reason, the participants of this study used their limited verbal output (often in combination with total communication strategies) to respond to the test. This is also the reason why none of the participants of this study used any form of AAC. Still, it is important to notice that a high score on The Scenario Test does not necessarily mean that the communicative abilities of PWA are equal to stroke survivors without aphasia or to their pre‐morbid abilities (Schumacher et al., 2020).

Future directions

The Scenario Test can discriminate between PWA who are able to convey a message independently from PWA who depend on a communication partner or a combination of verbal and non–verbal modalities of communication. Future work will involve the design and implementation of a post‐hoc patient reported outcome (PROM) questionnaire, in collaboration with PWA that participated in this study, to test content validity (relevance/appropriateness/comprehensibility/ importance) of the ST items following the COSMIN guidelines (Terwee et al., 2018). We also suggest a qualitative analysis of the recorded videos to facilitate an in‐depth investigation of the communication modes used by people with fluent aphasia versus those with non‐fluent aphasia. Additionally, we propose the development of more complex and abstract scenarios to quantify a wider range of aphasia severities, as the test might not be very demanding for participants with mild language production difficulties (Schumacher et al., 2020). This can also be captured by adapting the scoring protocol, measuring each modality separately (Nobis‐Bosch et al., 2020).

The original Scenario Test (van der Meulen et al., 2010) was found to be sensitive to changes in performance measured at 6 months post‐stroke, a parameter that was not measured in the present study. The Scenario Test‐GR is useful to examine the effectiveness of functional intervention and help clinicians select the most suitable approach during their intervention program (van der Meulen et al., 2010). It is necessary for communication intervention to determine whether alternative communication modes are also necessary, and the frequency and type of help needed from the communication partner (Russo et al., 2017). Further testing to measure sensitivity to change is suggested for the Greek version too. We recommend the creation of FC assessment tools that are co‐produced in active collaboration with PWA.

CONCLUSIONS

The Scenario Test‐GR is a reliable and valid tool that assesses FC in PWA with the use of real‐life scenarios that foster multimodal communication. The psychometric properties of the test are consistent with the psychometric qualities of the Dutch Scenario Test (van der Meulen et al., 2010) and The Scenario Test UK (Hilari et al., 2018). Total scores are now norm‐based, while the type (which modalities of communication) and frequency of how a person with aphasia responds are recorded. The findings of The Scenario Test‐GR provide strong evidence of the effects and difficulties PWA face when communicating in their everyday life. The Scenario Test‐GR is a very useful clinical tool for examining FC abilities, to guide patient‐centred therapy and goal‐setting, and to measure the efficiency of multimodality and interactivity.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTION

Marina Charalambous was the primary investigator involved in the design, methodology, patient recruitment, data collection and writing of the paper. Phivos Phylactou contributed to the study's statistical analysis and data interpretation. Thekla Elriz and Loukia Psychogios were involved in patient recruitment and data collection in Cyprus and Greece. Professor Jean‐Marie Annoni MD advised on the study's methodology and was the main reviewer of the manuscript. Professor Maria Kambanaros conceived the idea, advised on the theoretical constructs and research method, and oversaw the revising of the manuscript drafts.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declared no potential conflict of interest with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

FUNDING

This work was financially supported by the A.G. Leventis Foundation Doctoral Full Scholarship Grant, Geneva, Switzerland.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank all those with stroke and aphasia for their excellent collaboration.

Open access funding provided by Universite de Fribourg.

Charalambous M., et al. (2022) Adaptation of The Scenario Test for Greek‐speaking people with aphasia: A reliability and validity study. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders, 57, 865–880. 10.1111/1460-6984.12727

Marina Charalambous: https://orcid.org/0000‐0002‐5310‐3017

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data generated during or analysed in the current study are not publicly available due to ethical restrictions. All data queries and requests should be submitted to the corresponding author, Marina Charalambous PhD Researcher, for consideration.

REFERENCES

- Akoglu, H. (2018) User's guide to correlation coefficients. Turkish Journal of Emergency Medicine, 18(3), 91–93. 10.1016/j.tjem.2018.08.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anthimou, I. , Charalambous, M. & Kambanaros, M. (2020) The impact of aphasia on the quality of life of people with aphasia. Master's degree thesis in cognitive rehabilitation, Department of Rehabilitation Sciences, Cyprus University of Technology; (unpublished manuscript). [Google Scholar]

- Archer, B. , Azios, J.H. , Gulick, N. & Tetnowski, J. (2020) Facilitating participation in conversation groups for aphasia. Aphasiology, 35(6), 764–782. [Google Scholar]

- Azios, J. H. , Strong, K. A. , Archer, B. , Douglas, N. F. , Simmons‐Mackie, N. , et al. (2021) Friendship matters: a research agenda for aphasia. Aphasiology, 10.1080/02687038.2021.1873908 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baldo, J.V. , Dronkers, N.F. , Wilkins, D. , Ludy, C. , Raskin, P. & Kim, J. (2005) Is problem solving dependent on language? Brain and Language, 92(3), 240–250. 10.1016/j.bandl.2004.06.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg, K. , Isaksen, J. , Wallace, S. , Cruice, M. , Simmons‐Mackie, N. & Worrall, L. (2020) Establishing consensus on a definition of aphasia: an e‐Delphi study of international aphasia researchers. Aphasiology, 10.1080/02687038.2020.1852003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Blomert, L. , Kean, M. , Koster, C. & Schokker, J. (1994) Amsterdam—Nijmegen everyday language test: construction, reliability and validity. Aphasiology, 8(4), 381–407. 10.1080/02687039408248666 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Blom‐Smink, M. , van de Sandt‐Koenderman, M. , Kruitwagen, C. , El Hachioui, H. , Visch‐Brink, E.G. & Ribbers, G.M. (2017) Prediction of everyday verbal communicative ability of aphasic stroke patients after inpatient rehabilitation. Aphasiology, 31, 1379–91. [Google Scholar]

- Brady, M. , Kelly, H. , Godwin, J. , Enderby, P. & Campbell, P. (2016) Speech and language therapy for aphasia following stroke. Cochrane Database Of Systematic Reviews, 10.1002/14651858.cd000425.pub4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charalambous, M. & Kambanaros, M. (2021) The Importance of Aphasia Communication Groups [Online First]. IntechOpen, 10.5772/intechopen.101059. Retrieved: December 22nd 2021. Available at: https://www.intechopen.com/online‐first/79482 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Charalambous, M. , Kambanaros, M. & Annoni, J.M. (2020) Are people with aphasia (PWA) involved in the creation of quality of life and aphasia impact‐related questionnaires? A scoping review. Brain Sciences, 10(10), 688. 10.3390/brainsci10100688 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark, H.H. (1996) Using language. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press Consequences. [Google Scholar]

- Constanti, N. (2020) Administration of The Communicative Effectiveness Index in stroke survivors. Bachelor's thesis in Speech and Language Therapy, Rehabilitation Sciences Department, Cyprus University in Technology, https://ktisis.cut.ac.cy/handle/10488/19110 [Google Scholar]

- Dipper, L. , Marshall, J. , Boyle, M. , Botting, N. , Hersh, D. , Pritchard, M. , et al. (2020) Treatment for improving discourse in aphasia: a systematic review and synthesis of the evidence base. Aphasiology, 10.1080/02687038.2020.1765 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Doedens, W. , Bose, A. , Lambert, L. & Meteyard, L. (2021) Face‐to‐face communication in aphasia: the influence of conversation partner familiarity on a collaborative communication task. Frontiers in Communication, 6, 90. https://www.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fcomm.2021.574051 [Google Scholar]

- Doedens, W. & Meteyard, L. (2019) Measures of functional, real‐world communication for aphasia: a critical review. Aphasiology, 34(4), 492–514. 10.1080/02687038.2019.1702848 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Efstratiadou, E.A. , Chelas, E.N. , Ignatiou, M. , Christaki, V. , Papathanasiou, I. & Hilari, K. (2012) Quality of life after stroke: evaluation of the Greek SAQOL‐39g. Folia Phoniatrica Et Logopaedica, 64, 179–186. 10.1159/000340014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El Hachioui, H. , Lingsma, H.F. , Van de Sandt‐Koenderman, M.W. , Dippel, D.W. , Koudstaal, P.J. & Visch‐Brink, E.G. (2013) Long‐term prognosis of aphasia after stroke. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry, 84(3), 310–5. 10.1136/jnnp-2012-302596, PMID 23117494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elman, R.J. & Bernstein‐Ellis, E. (1999) The efficacy of group communication treatment in adults with chronic aphasia. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 42, 411–419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enderby, P. , Wood, V. , Wade, D. & Hewer, R. (1987) The Frenchay Aphasia Screening Test: a short, simple test for aphasia appropriate for non‐specialists. International Rehabilitation Medicine, 8(4), 166–170. 10.3109/03790798709166209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fotiou, C. & Grohmann, K.K. (2022) A small island with big differences? Folk perceptions in the context of dialect levelling and koineization. Frontiers in Communication, 6, 770088. 10.3389/fcomm.2021.770088 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Frattali, C. , Thompson, C.K. , Holland, A.L. , Wohl, C.B. & Ferketic, M. (1995) Functional assessment of communication skills for adult. New York: American Speech–Language–Hearing Association; [Google Scholar]

- Fullerton, K.J. , McSherry, D. & Stout, R.W. (1986) Albert's test: a neglected test of perceptual neglect. Lancet (London, England), 1(8478), 430–432. 10.1016/s0140-6736(86)92381-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodglass, H. & Kaplan, E. (1972) The assessment of aphasia and related disorders. Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger. [Google Scholar]

- Graetz, P. , De Bleser, R. & Willmes, K. (1991) De Akense Afasie Test. Aachen Aphasia Test. Logopedie en Foniatrie, 63, 58–68 [Google Scholar]

- Hilari, K. , Byng, S. , Lamping, D.L. & Smith, S.C. (2003) Stroke and Aphasia Quality of Life Scale‐39 (SAQOL‐39): evaluation of acceptability, reliability, and validity. Stroke; A Journal of Cerebral Circulation, 34(8), 1944–1950. 10.1161/01.STR.0000081987.46660.ED [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilari, K. & Dipper, L. (2020) The Scenario Test (validated in the UK). Guildford: J&R Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hilari, K. , Galante, L. , Huck, A. , Pritchard, M. , Allen, L. & Dipper, L. (2018) Cultural adaptation and psychometric testing of The Scenario Test UK for people with aphasia. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders, 53(4), 748–760. 10.1111/1460-6984.12379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holland, A. (1980) Communicative Abilities of Daily Living Test (CADL). Baltimore: University Park Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hoover, E. , McFee, A. & DeDe, G. (2020) Efficacy of group conversation intervention in individuals with severe profiles of aphasia. Seminars in speech and language, 41(1), 71–82. 10.1055/s-0039-3400991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irwin, W.H. , Wertz, R.T. & Avent, J.R. (2006) Relationships among language impairment, functional communication, and pragmatic performance in aphasia. Aphasiology, 16, 823–35. [Google Scholar]

- Kertesz, A. (2006) The Western Aphasia Battery‐R. Bloomington, MN: Pearson. [Google Scholar]

- Koleck, M. , Gana, K. , Lucot, C. , Darrigrand, B. , Mazaux, J. & Glize, B. (2017) Quality of life in aphasic patients 1 year after a first stroke. Quality Of Life Research, 26(1), 45–54. 10.1007/s11136-016-1361-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kranou‐Economidou, D. & Kambanaros, M. (2020) Combining intermittent theta burst stimulation (iTBS) with computerized working memory training to improve language abilities in chronic aphasia: a pilot case study. Aphasiology, 36(5), 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Lanyon, L. , Worrall, L. & Rose, M. (2018) What really matters to people with aphasia when it comes to group work? A qualitative investigation of factors impacting participation and integration. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders, 53(3), 526–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lomas, J. , Pickard, L. , Bester, S. , Elbard, H. , Finlayson, A. & Zoghaib, C. (1989) The Communicative Effectiveness Index. Journal Of Speech And Hearing Disorders, 54(1), 113–124. 10.1044/jshd.5401.113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luck, A. & Rose, M. (2007) Interviewing people with aphasia: insights into method adjustments from a pilot study. Aphasiology, 21(2), 208–224. 10.1080/02687030601065470 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Manning, M. , MacFarlane, A. , Hickey, A. & Franklin, S. (2019) Perspectives of people with aphasia post‐stroke towards personal recovery and living successfully: a systematic review and thematic synthesis. PLoS One, 14(3), e0214200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McHugh, M.L. (2012) Interrater reliability: the kappa statistic. Biochemia medica, 22(3), 276–282. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meier, E.L. , Johnson, J.P. , Villard, S. & Kiran, S. (2017) Does naming therapy make ordering in a restaurant easier? Dynamics of co‐occurring change in cognitive–linguistic and functional communication skills in aphasia. American Journal of Speech–Language Pathology, 26, 266–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messinis, L. , Panagea, E. , Papathasopoulos, P. & Kastellakis, A. (2013) Boston Diagnostic Aphasia Examination‐short form in Greek language. Patras: Gotsis. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, C. , Gittins, M. , Tyson, S. , Vail, A. , Conroy, P. , Paley, L. , et al. (2020) Prevalence of aphasia and dysarthria among inpatient stroke survivors: describing the population, therapy provision and outcomes on discharge. Aphasiology, 10.1080/02687038.2020.1759772 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nobis‐Bosch, R. , Bruehl, S. , Krzok, F. , Jakob, H. , van de Sandt‐Koendermann, M. & van der Meulen, I. (2020) Szenario‐Test. Testung verbaler und nonverbaler Aspekte aphasischer Kommunikation. Kooln: ProLog. [Google Scholar]

- Nunnally, J. & Bernstein, I. , (1994) Psychometric Theory. New York: McGraw‐Hill. [Google Scholar]

- Olsson, C. , Arvidsson, P. & Blom Johansson, M. (2019) Relations between executive function, language, and functional communication in severe aphasia. Aphasiology, 33. 10.1080/02687038.2019.1602813. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Perin, C. , Bolis, M. , Limonta, M. , Meroni, R. , Ostasiewicz, K. , Cornaggia, C.M. , et al. (2020) Differences in rehabilitation needs after stroke: a similarity analysis on the ICF core set for stroke. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(12), 4291. 10.3390/ijerph17124291 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierce, J. , O'Halloran, R. , Togher, L. & Rose, M. (2019) What Is meant by “Multimodal Therapy” for aphasia? American Journal of Speech–Language Pathology, 28(2), 706–716. 10.1044/2018_ajslp-18-0157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramey, K.E. , Champion, D.N. , Dyer, E.B. , Keifert, D.T. , Krist, C. , Meyerhoff, P. , et al. (2016) Qualitative analysis of video data: standards and heuristics In Looi, C.K., Polman , J. L., Cress, U. & Reimann, P. (Eds.). Transforming Learning, Empowering Learners: The International Conference of Learning Sciences (ICLS), 2, 1033–1040. Singapore: International Society of the Learning Sciences. [Google Scholar]

- Raven, J. (2000) The Raven's progressive matrices: change and stability over culture and time. Cognitive Psychology, 41(1), 1–48. 10.1006/cogp.1999.0735 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russo, M.J.P. , Meda, N.N. , Carcavallo, L. , Muracioli, A. , Sabe, L. , Bonamico, L. , et al. (2017) High‐technology augmentative communication for adults with post‐stroke aphasia: a systematic review. Expert Review of Medical Devices, 14(5), 355–370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarno, M.T. and & University N.Y.. (1969) The functional communication profile: Manual of directions. New York: Institute of Rehabilitation Medicine, New York Univ. Medical Center. [Google Scholar]

- Schumacher, R. , Bruehl, S. , Halai, A. D. & Ralph L. M. A. (2020) The verbal, non‐verbal and structural bases of functional communication abilities in aphasia. Brain Communications, 2(2). 10.1093/braincomms/fcaa118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shippee, N.D. , Garces, J.P.D. , Lopez, G.J.P. , Wang, Z. , Elraiyah, T.A. , Nabhan, M. , et al. (2013) Patient and service user engagement in research: a systematic review and synthesized framework. Health Expectations, 18, 1151–1166. 10.1111/hex.12090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simmons‐Mackie, N. , Kagan, A. , Victor, J.C. , Carling‐Rowland, A. , Mok, A. , Hoch, J.S. , et al. (2014) The assessment for living with aphasia: reliability and construct validity. International Journal of Speech–Language Pathology, 16, 82–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Streiner, D. , Norman, G. & Cairney, J. (2014) Health Measurement Scales: a practical guide to their development and use. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Swinburn, K. , Best, W. , Beeke, S. , Cruice, M. , Smith, L. , & Pearce Willis, E. et al. (2018) A concise patient reported outcome measure for people with aphasia: the aphasia impact questionnaire 21. Aphasiology, 33(9), 1035–1060. 10.1080/02687038.2018.1517406 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Swinburn, K. , Porter, G. & Howard, D. (2004) The Comprehensive Aphasia Test. London: Whurr. [Google Scholar]

- Taherdoost, H. (2016) Validity and reliability of the research instrument: how to test the validation of a questionnaire/survey in a research. International Journal of Academic Research in Management (IJARM), 5. [Google Scholar]

- Tarrant, M. , Carter, M. & Dean, S.G. (2021) Singing for people with aphasia (SPA): results of a pilot feasibility randomised controlled trial of a group singing intervention investigating acceptability and feasibility. BMJ Open, 11. 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-040544 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terwee, C.B. , Prinsen, C. , Chiarotto, A. , Westerman, M.J. , Patrick, D.L. , Alonso, J. , et al. (2018) COSMIN methodology for evaluating the content validity of patient‐reported outcome measures: a Delphi study. Quality of Life Research : An International Journal of Quality of Life Aspects of Treatment, Care and Rehabilitation, 27(5), 1159–1170. 10.1007/s11136-018-1829-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Meulen, I. , van de Sandt‐Koenderman, W. , Duivenvoorden, H. & Ribbers, G. (2010) Measuring verbal and non‐verbal communication in aphasia: reliability, validity, and sensitivity to change of The Scenario Test. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders, 45(4), 424–435. 10.3109/13682820903111952 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wafa, H.A. , Wolfe, C.D.A. , Emmett, E. , Roth, G.A. , Johnson, C.O. & Wang, Y. (2020) Burden of Stroke in Europe. Stroke: A Journal of Cerebral Circulation, 10.1161/strokeaha.120.0296 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace, S.J. , Worrall, L. , Rose, T. , Le Dorze, G. , Breitenstein, C. , Hilari, K. , et al. (2019) A core outcome set for aphasia treatment research: the ROMA consensus statement. International Journal of Stroke, 14(2), 180–185. 10.1177/1747493018806200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (WHO) . (2001) International classification of functioning, disability and health: ICF. Geneva: World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- Worrall, L. , McCooey, R. , Davidson, B. , Larkins, B. & Hickson, L. (2002) The validity of functional assessments of communication and the Activity/Participation components of the ICIDH‐2: do they reflect what really happens in real‐life? Journal of Communication Disorders, 35, 107–137. 10.1016/S0021-9924(02)00060-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Worrall, L. , Sherratt, S. , Rogers, P. , Howe, T. , Hersh, D. , Ferguson, A. , et al. (2011) What people with aphasia want: their goals according to the ICF. Aphasiology, 25(3), 309–322. 10.1080/02687038.2010.508530 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data generated during or analysed in the current study are not publicly available due to ethical restrictions. All data queries and requests should be submitted to the corresponding author, Marina Charalambous PhD Researcher, for consideration.