Abstract

Objective

Despite a number of qualitative studies published from the perspective of eating disorder (ED) service users, there has been no attempt to exclusively synthesize their views to gain a fuller understanding of their ED service experiences. It is important to understand this perspective, since previous research highlights the difficulties ED healthcare professionals report when working with this client group.

Method

A systematic search of the literature was conducted to identify qualitative studies focusing on experiences of ED services from the perspective of service users. Twenty‐two studies met the inclusion criteria and underwent a quality appraisal check using the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) tool for qualitative research. These were then synthesized using a meta‐synthesis approach.

Results

Four overarching themes were generated: “Treatment: Focus on physical vs. psychological symptoms”; “Service Environment: The role of control within services”; “Staff: Experiences with staff and the value of rapport”; and “Peer Influence: Camaraderie vs. comparison.” Service users expressed a desire for more psychological input to tackle underlying difficulties relating to their ED. A complex relationship with feelings of control was described, with some feeling over‐controlled by service providers, while others retrospectively recognized the need for control to be taken away. Staff values, knowledge and trust played a significant role in treatment and recovery. Peers with an ED were described to be a valuable source of understanding and empathy, but some found peer influence to perpetuate comparison and competitiveness.

Discussion

The results portray some of the conflicts and complexities that service users encounter in ED services. A running thread throughout is the perceived importance of adopting an individualized approach within these services.

Keywords: eating disorders, lived experience, mental health, mental health services, meta‐synthesis, qualitative research

Key Practitioner Message.

The synthesis of service users' eating disorder service experiences can help us to understand which aspects of services are of particular importance to service users and the impact of these on their prognosis and recovery.

Service users perceived an overfocus on weight within their treatment, with a lack of regard for the psychological underpinnings of their eating disorder. They also described a complex and often conflicting narrative around control.

Relationships with eating disorder healthcare professionals and peers played a significant role in their treatment, both positively and negatively.

This review stresses the impact and significance of adopting an individualized approach in eating disorder services for a population that reports often feeling negatively stereotyped by healthcare professionals.

This review highlights that the experiences of marginalized groups (e.g., ethnic minority and sexual/gender minority groups) remain under‐researched in the eating disorder literature.

1. INTRODUCTION

Eating disorders (EDs) are debilitating mental health conditions with one of the highest mortality rates across all psychiatric disorders (Chesney et al., 2014). The course and outcome of an ED is hugely variable (Goss & Fox, 2012), but it has been estimated in longitudinal studies that up to 55% of people with bulimia nervosa and 53% with anorexia nervosa will not be fully recovered at 9 years after onset, with a significant proportion developing a severe and enduring presentation of the disorder (Steinhausen, 2002; Steinhausen & Weber, 2009), with illness duration often predicting recovery rates (Keel & Brown, 2010; Nagl et al., 2016). There can also be serious medical complications as a result of an ED, including, but not limited to, osteoporosis (Mehler et al., 2011), refeeding syndrome (Crook et al., 2001), gastrointestinal complications (Hetterich et al., 2019) and cardiac abnormalities (Sachs et al., 2016). Psychological and medical consequences mean that many individuals with an ED require healthcare service input. In the United Kingdom, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE; National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, 2017) sets out standardized guidelines for the treatment of EDs.

There are consistent challenges reported by those working in ED services, and these include treating psychiatric and medical symptoms alongside each other (Fox & Goss, 2012), maintaining a therapeutic relationship when faced with denial and treatment resistance from service users (Snell et al., 2010), and being aware of the influence of one's own personal attributes (e.g., appearance and eating behaviours) on service users (Warren et al., 2008). Given the challenges reported by healthcare professionals working with ED client groups, it is important to understand the experiences of those working in these services and the existing literature has achieved this to a reasonable degree. However, it is also crucial that we strive to also understand the experiences of those using ED services to begin to provide solutions to some of these challenges.

A recent meta‐ethnography synthesized qualitative research focusing on healthcare professionals' experiences of working with people with an ED (Graham et al., 2020). They generated a model to understand ED healthcare professionals' experiences, providing clinical recommendations for improving support for staff. Taking a broader approach by including perspectives of individuals with an ED, their families and health professionals, a recent systematic review employed a narrative synthesis methodology to explore experiences of primary and secondary care for EDs (Johns et al., 2019). This synthesis explored both qualitative and quantitative research and identified barriers across ED healthcare interfaces, such as a lack of ED knowledge in primary care, a need for better communication across services, and a lack of partnership between ED services, patients and families.

While these reviews provide us with valuable insights into the perspectives of ED service users and providers, there is still a need for a review of ED services exclusively from the service users' perspectives. Johns et al. (2019)'s synthesis including service user, parent and healthcare professionals' views has an element of comparison across these three groups' views, which limits a nuanced investigation of the exclusive views of service users. Moreover, while there are existing reviews that have synthesized the views of specific groups of ED service users, for example, the treatment experiences of males with an ED (Thapliyal & Hay, 2014), these are not generalizable to the wider population of ED service users. Taking a more holistic approach and synthesizing qualitative accounts from all ED service users can provide healthcare services with in‐depth, personal experiences and perspectives across different characteristics and populations. Consequently, these accounts can be utilized to inform care provision, treatment and service policies, ensuring a person‐centred approach is endorsed (Holloway & Galvin, 2016). This warrants the synthesis of qualitative studies from service users' perspective to understand their experiences more holistically, or conversely seek out any differences across populations.

For the current review, a meta‐synthesis approach was chosen (Walsh & Downe, 2005). A meta‐synthesis aims to “produce a new and integrative interpretation of findings that is more substantive than those resulting from individual investigations” (Finfgeld, 2003, p. 894). The meta‐synthesis approach described by Walsh and Downe (2005) follows the steps for synthesis of qualitative studies outlined by Noblit and Hare (1988).

The aim of this meta‐synthesis is to explore the experiences of ED services from the service user perspective.

2. METHOD

2.1. Meta‐synthesis

We used the guidance described in the seminal meta‐ethnographic paper by Noblit and Hare (1988) and utilized the further refinement relating to meta‐synthesis approaches outlined by Walsh and Downe (2005). The seven phases outlined by Noblit and Hare (1988) for synthesizing qualitative studies were followed: (i) getting started; (ii) deciding what is relevant to the initial interest; (iii) reading the studies; (iv) determining how the studies are related; (v) translating the studies into one another; (vi) synthesizing translations; and (vii) expressing the synthesis.

2.2. Systematic literature search

Studies were identified using four blocks of terms relating to the disorder under investigation (EDs), the population (service users), the type of research (qualitative) and the phenomenon of interest (ED services). Blocks were combined using the Boolean operator “AND,” and terms within each block combined using “OR.” Search terms are outlined in Table 1. A comprehensive systematic search was carried out in November 2020 using the following databases: Medline, PsycINFO, Web of Science and CINAHL. Additional studies were identified through a process of chaining and manual journal searches.

TABLE 1.

Search terms and Boolean operators used to identify studies for the meta‐synthesis

| Block 1 – Disorder | Block 2 – Population | Block 3 – Type of research | Block 4 – Phenomenon of interest |

|---|---|---|---|

|

“Eating disorder*” OR anore* OR bulimi* OR EDNOS OR OSFED OR ED |

Patient* OR individual* OR adolescent* OR adult* OR “service user*” OR client* |

Perspective* OR view* OR experience* OR “point of view” OR reflect* OR qual* OR interview* |

“Eating disorder service*” OR “eating disorder unit*” OR inpatient OR outpatient OR “day patient” OR “eating disorder treatment” OR treatment OR therapy |

Note: Blocks were combined in the Boolean operator “AND.”

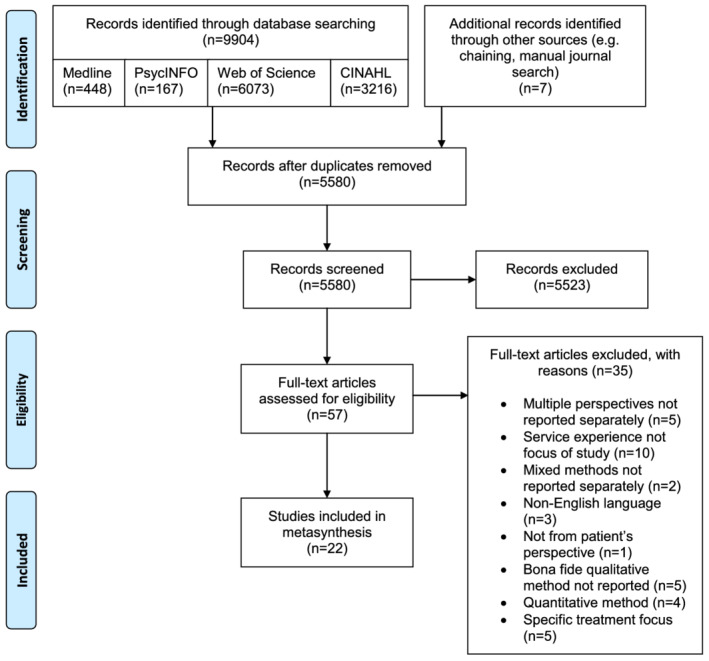

Screening processes and reasons for exclusions are presented in Figure 1 (Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff, Altman, & PRISMA Group, 2009). An independent researcher reviewed a random selection (~30%) of the 57 full‐text articles that were assessed for eligibility against the inclusion criteria to aid the selection process. There was unanimous agreement on the suitability of the included and excluded papers for the meta‐synthesis.

FIGURE 1.

PRISMA flow diagram of search process, study selection, and exclusion (Moher et al., 2009)

2.3. Inclusion criteria

Studies that met the following criteria were included: (i) Study adopts a qualitative methodology (or mixed methods, if qualitative results are reported separately) and uses a named, bona fide analytic approach for qualitative data, for example, grounded theory, thematic analysis and interpretative phenomenological analysis; (ii) participants had a current or past ED (e.g., anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, other specified feeding or eating disorder (OSFED)/eating disorder not otherwise specified (EDNOS)) from any age group (e.g., adolescent or adult); (iii) participants' ED led them to be current or past service users; (iv) the discussion was relevant to the ED service as a whole (any studies that focused on specific parts of a service, such as a novel treatment intervention, were not included as this would not allow us to develop an understanding of the whole service experience); (v) study was based in any country (providing the paper was written in English). No date limits were imposed when selecting papers.

In our inclusion criteria, we decided to include EDs as a homogenous group, rather than focusing on a specific ED, in order to be as inclusive as possible and to capture a range of experiences. The transdiagnostic view of EDs highlights that the core features of an ED are often present across all ED subcategories (Fairburn et al., 2003) and this is supported by the recognition of high levels of diagnostic fluidity (i.e., migration between different ED diagnostic categories) across the illness duration (Castellini et al., 2011).

2.4. Quality appraisal

Included papers underwent a quality appraisal check before analysis. The Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) tool for qualitative research (Critical Appraisal Skills Programme, 2018) was chosen due to its accessibility and widespread use in meta‐syntheses, notably in healthcare research (e.g., Kelly et al., 2018; Strandås & Bondas, 2018). A grading system adapted from Fox et al. (2017) was used, taking into account the updated CASP scoring (Critical Appraisal Skills Programme, 2018) since its publication. Scores of 8+ received an A, implicating low likelihood of methodological flaws, scores of 4.5–7.5 received a B, denoting moderate likelihood of methodological flaws, and scores of 4 and below received a C, suggesting high likelihood of methodological flaws. CASP scores and grades are presented in Table 2. All papers were rated by the first author. To increase the objectivity and rigour of quality appraisals, a random selection of approximately 20% (5/22) of papers were also rated by an independent researcher. There was unanimous agreement on 82% of scores, and remaining discrepancies were resolved via discussion between the first author and the independent researcher. Given that all selected papers were rated to be of a relatively high‐quality standard (scoring A or B), no papers were excluded on methodological grounds.

TABLE 2.

Quality ratings using the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) tool for qualitative research

| Study | Items | Overall score | Grade | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Was there a clear statement of the aims of the research? | 2. Is a qualitative methodology appropriate? |

3. Was the research design appropriate to address the aims of the research? |

4. Was the recruitment strategy appropriate to the aims of the research? | 5. Was the data collected in a way that addressed the research issue? |

6. Has the relationship between researcher and participants been adequately considered? |

7. Have ethical issues been taken into consideration? | 8. Was the data analysis sufficiently rigorous? | 9. Is there a clear statement of findings? | |||

| 1. | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 8 | A |

| 2. | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8 | A |

| 3. | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 7 | B |

| 4. | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0.5 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0.5 | 5 | B |

| 5. | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 7.5 | B |

| 6. | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 8.5 | A |

| 7. | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 8.5 | A |

| 8. | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 8.5 | A |

| 9. | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 0 | 0 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 5.5 | B |

| 10. | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 1 | 0.5 | 7.5 | B |

| 11. | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8 | A |

| 12. | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 7.5 | B |

| 13. | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 9 | A |

| 14. | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 6.5 | B |

| 15. | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8.5 | A |

| 16. | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 6 | B |

| 17. | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 8 | A |

| 18. | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 9 | A |

| 19. | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7.5 | B |

| 20. | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 7.5 | B |

| 21. | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 | B |

| 22. | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8.5 | A |

Note: Response options: 1 = Yes; 0.5 = Cannot Tell; 0 = No.

2.5. Thematic synthesis

The full papers were entered into the software programme QSR NVivo 12 (QSR International Pty Ltd., 2018) for analysis and initial codes were developed from relevant areas of the papers (e.g., Results sections) where service users described their experiences. Data were extracted from first‐order (participant quotes) and second‐order (author interpretation of participant quotes) constructs. Following guidance from Noblit and Hare (1988), studies were compared and translated into one another to identify third‐order concepts (i.e., our interpretations of the original authors' interpretations). This was done by identifying overlapping (reciprocal translations) and contrasting (refutational translations) codes across studies. Finally, codes were synthesized and refined to create overarching themes and subthemes that represent concepts across the studies.

3. RESULTS

In total, 22 studies were included (see Table 3). The total number of participants across all studies was 712, of which 23 were male. Where data were reported, ages ranged from 11 to 64 years, although five studies did not report exact age ranges (e.g., only reported mean age). Participants reported to have anorexia nervosa (n = 296), bulimia nervosa (n = 15), eating disorder not otherwise specified or other specified feeding or eating disorder (n = 13) or orthorexia (n = 1). Two studies reported that participants had “anorexia nervosa and/or bulimia nervosa” (n = 59; Malson et al., 2004; Reid et al., 2008). Some studies were less specific with reporting diagnoses, with 12 participants reported having “anorexia nervosa or eating disorder not otherwise specified” (Eli, 2014), 294 participants identifying as a “person with an eating disorder” (Escobar‐Koch et al., 2010), eight participants with a severe and enduring ED (Joyce et al., 2019), and six participants unspecified (Rother & Buckroyd, 2004). Ten studies focused primarily on inpatient experiences, two on outpatient experiences and six included a combination of both inpatient and outpatient experiences. The remaining three studies did not specify service type. Samples came from eight countries, but the majority were UK samples (either exclusively from the United Kingdom or mixed; n = 13). Other countries included Australia (n = 5), the United States (n = 3), Israel (n = 1), Chile (n = 1), Sweden (n = 1), Republic of Ireland (n = 1) and China (n = 1). Only three studies reported on ethnicity—of these, all were White/Caucasian, with the exception of one participant identifying as Afro‐Caribbean.

TABLE 3.

Summary of included papers

| Study |

Authors (Year) Country |

Aim | Sample characteristics | Type of eating disorder | Type of service | Data collection | Analytic approach |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. |

Colton and Pistrang (2004) UK |

To provide a detailed description of how adolescents on inpatient, specialist eating disorder units view their treatment. |

N = 19 (19 female) Aged 12–17 years (mean = 15.4 years) White British n = 17; White Irish n = 1; Afro‐Caribbean n = 1 |

All had primary diagnosis of anorexia nervosa | Adolescent inpatient eating disorder service | Semi‐structured interviews | Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis (Smith & Osborn, 2003) |

| 2. |

Eli (2014) Israel |

To identify the ways in which inpatient ambivalence might be embedded in the special social institutional setting that an eating disorder ward presents, beyond patient‐specific motivation for recovery. |

N = 13 (12 female; 1 male) Aged 18–38 years |

“Anorexia nervosa or eating disorder not otherwise specified” (N = 12); bulimia nervosa (N = 1) | Inpatient eating disorder ward for adults | Semi‐structured interviews | Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis (Smith et al., 1999; Smith & Osborn, 2003) |

| 3. |

Escobar‐Koch et al. (2010) USA and UK |

To obtain an in‐depth view of a large number of US and UK eating disorder patients' perspectives on treatment and service provision, to perform a comparison between these countries. |

N = 294 UK: N = 150 (145 female; 5 male) Mean age = 26.6 years USA: N = 144 (140 female; 4 male) Mean age = 30.1 years |

Not specified; inclusion criteria = “a person with an eating disorder” | Not specified | Online questionnaire (open‐ended questions) | Conventional content analysis (Hsieh & Shannon, 2005) |

| 4. |

Escobar‐Koch et al. (2012) Chile |

To identify the views of Chilean patients who have received treatment for an eating disorder about these treatments, including aspects they value, and feel have helped them in their recovery as well as aspects they feel have hindered their recovery or been missing from their treatments. |

N = 10 (10 female) Aged 16–47 years (mean = 30.7 years) |

Bulimia nervosa (N = 6); anorexia nervosa (N = 3); eating disorder not otherwise specified (N = 1) | Treated for eating disorder at general hospital | Semi‐structured interviews | Grounded Theory (Glaser & Strauss, 1967) |

| 5. |

Fogarty and Ramjan (2016) UK and Australia |

To better understand the care experience during treatment for anorexia nervosa in individuals with self‐reported anorexia nervosa or recovery from anorexia nervosa. |

N = 161 (75 female) Mean age = 25.11 years (Note: only 46.6% of participants completed age/gender questions) |

Self‐reported anorexia nervosa | Inpatient, outpatient, or combination of both (reported by 97% of respondents) | Online questionnaire (open‐ended questions) | Conventional content analysis (Hsieh & Shannon, 2005) |

| 6. |

Fox and Diab (2015) UK |

To explore sufferer's perceived experiences of living with and being treated within an eating disorders unit for their chronic anorexia nervosa |

N = 6 (6 female) Aged 19–50 years (mean = 27 years) |

Chronic anorexia nervosa | Inpatient | Semi‐structured interviews | Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis (Smith, 2004) |

| 7. |

Joyce et al. (2019) UK |

To explore the following questions: 1. What are people's experiences of receiving input from services for long‐term eating disorders? 2. What are the social, political, and cultural narratives which impact on those experiences? |

N = 8 (7 female; 1 male) Aged 20–64 years (mean = 44 years) |

Severe and enduring eating disorder (specific type of eating disorder not reported) | “Self‐reported experience of specialist eating disorder services”; multiple inpatient admission (N = 5); singular inpatient admission (N = 1); no inpatient admission (N = 2) | Interviews with a focus on narrative inquiry | Narrative Analysis (e.g., Crossley, 2000, 2007; Howitt, 2010; Riessman, 1993, 2008; Weatherhead, 2011) |

| 8. |

Lindstedt et al. (2015) Sweden |

To investigate how young people with experience from adolescent outpatient treatment for eating disorders, involving family‐based and individual based interventions, perceive their time in treatment. |

N = 15 (14 female; 1 male) Aged 13–18 years |

Anorexia nervosa (N = 6); eating disorder not otherwise specified (“with a restrictive symptomology”) (N = 9) | Outpatient and/or inpatient (inpatient N = 4) | Semi‐structured interviews | Hermeneutic phenomenological approach (van Manen, 1997) |

| 9. |

Maine (1985) USA |

To examine the efficacy of treatment of anorexia from the recovered patient's point of view, with the underlying assumption that she best knows the interactions of phenomena stimulating or threatening her recovery. |

N = 25 (25 female) Aged 13–23 years (mean = 16.8 years) |

Anorexia nervosa | Combination of inpatient and outpatient | Semi‐structured interviews | Thematic content analysis (Holsti, 1968) |

| 10. |

Malson et al. (2004) Australia and UK |

To explore participants' accounts of their treatment experiences and, in particular, to elucidate the ways in which “the eating disordered patient” is constituted both in terms of participants' self‐constructions and of constructions of “the patient” that are attributed to healthcare workers. |

N = 39 (38 female; 1 male) Aged 14–45 years |

Anorexia nervosa and/or bulimia nervosa | Inpatient | Semi‐structured interviews | Discourse analysis (Burman & Parker, 1993; Potter, 2003; Potter & Wetherell, 1987) |

| 11. |

Offord et al. (2006) UK |

To explore young adults' views regarding: The inpatient treatment they received for anorexia nervosa during their adolescences; their experiences of discharge; and the impact their admission had on issues of control and low self‐esteem. |

N = 7 (7 female) Aged 16–23 years White British N = 7 |

Anorexia nervosa | Inpatient (general adolescent inpatient setting) | Semi‐structured interviews | Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis (Smith & Osborn, 2003) |

| 12. |

Patterson et al. (2017) Australia |

To assess the perceived helpfulness of various components of treatment, and clinician behaviours and attitudes valued by patients. |

N = 12 (12 female) Aged 18–50 years |

Anorexia nervosa‐binge‐purge subtype (N = 1); anorexia nervosa‐restrictive subtype (N = 11) | Inpatient | Semi‐structured interviews | Framework approach (Gale, Heath, Cameron, Rashid & Redwood, 2013) |

| 13. |

Rance et al. (2017) UK |

To begin the process of eliciting clients' views by giving anorexia nervosa sufferers the opportunity to talk about their experiences of being treated for their eating disorder. |

N = 12 (12 female) Aged 18–50 years (mean = 31.5 years) |

Anorexia nervosa (self‐diagnosis N = 1) | Combination on inpatient and outpatient | Semi‐structured interviews | Thematic Analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2006; 2013) |

| 14. |

Reid et al. (2008) UK |

To describe sufferers' perspectives of their eating disorders and their experiences of an outpatient service and provide related practical recommendations for treatment. |

N = 20 (19 female; 1 male) Aged 17–41 years |

Anorexia nervosa and/or bulimia nervosa | Outpatient | Semi‐structured interviews | Thematic Analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2006) |

| 15. |

Ross and Green (2011) UK |

To consider the question of whether inpatient admission was a therapeutic experience for two women with chronic anorexia nervosa. |

N = 2 (2 female) Aged 18+ |

Anorexia nervosa | Inpatient | Semi‐structured interviews | Narrative thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2006) |

| 16. |

Rother and Buckroyd (2004) UK |

To identify the service provision used, if any, by adolescent sufferers of eating disorders and what, in their opinion, would have been desirable at that time. |

N = 6 (6 female) Aged ~18–28 years (Note: Recruitment targeted 18‐ to 28‐year‐olds; actual ages of final sample unknown) |

Not specified | “Past adult users of a voluntary sector agency”; does not specify service type | Semi‐structured interviews | Thematic qualitative analysis (Huberman & Miles, 1988) |

| 17. |

Sheridan and McArdle (2016) Republic of Ireland |

To explore the treatment experiences of both current and discharged eating disorder patients to gain insight into those factors that influenced their motivational treatment trajectory |

N = 14 (14 female) Aged 18–31 years (mean = 23.2 years) |

Anorexia nervosa (N = 6); bulimia nervosa (N = 2); other specified feeding or eating disorder (N = 3) | Inpatient and outpatient (N = 9) or outpatient only (N = 5) | Semi‐structured interviews | Thematic Analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2006) |

| 18. |

Smith et al. (2016) UK |

To explore women's experiences of specialist inpatient treatment for anorexia nervosa during their treatment admission. |

N = 21 (21 female) Aged 18–41 years (mean = 25.2 years) |

Anorexia nervosa | Inpatient | Semi‐structured interviews | Thematic Analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2006) |

| 19. |

(Thapliyal et al., 2020) Australasia and North America |

To investigate the treatment experiences of a group of men who had sought help, were diagnosed with an eating disorder, and received eating disorder specific treatment. |

N = 8 (8 male) Aged 20–33 years (mean = 26 years) |

Anorexia nervosa (N = 4); bulimia nervosa (N = 3); orthorexia (N = 1) | Combination of inpatient and outpatient | Semi‐structured interviews | Thematic Analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2006; Pope, Ziebland & Mays, 2000) |

| 20. |

Tierney (2008) UK |

To explore the views of young people about being treated for anorexia nervosa. |

N = 10 (9 female; 1 male) Aged 11–18 years (mean = 17 years) Caucasian N = 10 |

Anorexia nervosa‐restrictive subtype (N = 5); anorexia nervosa‐binge‐purge subtype (N = 5) | Combination of inpatient and outpatient service input | Semi‐structured interviews | Thematic analysis (Smith, Harre & Van Langenhare, 1995) |

| 21. |

Walker and Lloyd (2011) Australia |

To explore the service user's perspectives of treatment experiences. |

N = 6 (6 female) Aged 18+ years |

Anorexia nervosa‐restrictive subtype (N = 2); anorexia nervosa‐binge‐purge subtype (N = 1); bulimia nervosa (N = 3) | Not specified; recruited from caseloads of an eating disorder service so all participants had some service input at time of study; criteria states: “not currently receiving inpatient treatment” | Focus group | Consensual Qualitative Research (CQR; Hill et al., 1997) |

| 22. |

Wu and Harrison (2019) China |

To understand the experiences of four adolescents receiving inpatient treatment for eating disorders in mainland China. |

N = 4 (4 female) Aged 16–19 years |

Anorexia nervosa‐binge‐purge subtype | Inpatient | Semi‐structured interviews | Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis (Smith, Flowers & Osborn, 1997; Smith, Flowers & Larkin, 2009) |

Four overall themes were established, relating to Treatment, Service Environment, Staff and Peer Influence (see Table 4 for overview).

TABLE 4.

Overview of themes and subthemes

| Theme | Subtheme |

|---|---|

| Treatment: Focus on physical vs. psychological symptoms | Access to treatment |

| During treatment | |

| Discharge from services | |

| Service environment: The role of control within services | Shifts in control during treatment |

| Control as punishment | |

| Staff: Experiences with staff and the value of rapport | “Another anorexic” |

| Staff consistency | |

| Hopelessness vs. hopefulness | |

| Being seen as an individual | |

| Peer influence: Camaraderie vs. comparison | Support from peers |

| Distress caused by peers |

3.1. Treatment: Focus on physical vs. psychological symptoms

Many participants perceived ED services to overfocus on weight and food intake, subsequently dismissing or minimizing the psychological underpinnings of their ED. This perceived overfocus was encountered throughout participants' experience of services—from accessing treatment through to discharge.

3.2. Subtheme: Access to treatment

Participants described being refused treatment because their weight was not low enough:

“Treatment was often, inaccessible … with participants experiencing “being sent home until critical and in need of life saving (45)” and trouble “getting the GP to refer me to specialists as I was told my weight was not low enough (142)” (Fogarty & Ramjan, 2016, p. 6).

This led participants to incentivize further weight loss, as it was the only way to be “[taken] seriously” (participant; Tierney, 2008, p. 370) and receive help. One participant likened it to playing a “game”:

I feel that I'm forced to be manipulative sometimes to get the help that I need … when it's kind of focused on “Well if you lose another kilo then we'll, then we'll escalate you up the waiting list” … you [are] kind of almost forced to play that game (participant; Rance et al., 2017, p. 587).

3.3. Subtheme: During treatment

Participants also noted that treatment itself focused on weight restoration with little regard for the psychological strain of weight gain:

Patient 5 was also concerned that practitioners concentrated on “getting your weight up, and then they expect everything else to level off in your head, but it doesn't” (participant; Tierney, 2008, p. 370).

Some participants expressed a need for “psychological support to ‘soothe’ the distress related to re‐feeding” (Wu & Harrison, 2019, p. 5). ED services that recognized the “emotional impact of weight gain and addressed psychological and physical issues in parallel were viewed as most helpful” (Offord et al., 2006, p. 382). Notably, services described as consisting of a well‐coordinated and “connected” multi‐disciplinary team seemed best equipped to address both psychological and physical needs, emphasizing the importance of strong communication links across professions within the service (Escobar‐Koch et al., 2012, p. 256).

Many participants demonstrated awareness of the importance of weight restoration and food intake within their treatment plan, with inpatient care in particular described as “saving [their] lives” (Wu & Harrison, 2019, p. 9). However, the overwhelming message was that this should be accompanied by other types of support, such as psychological, practical, and emotional support. A more “holistic” and individualized approach to care was desirable, in which participants felt supported “to uncover and address the underlying issues” (Offord et al., 2006, p. 381):

The turning point came when they … found a supportive space within services to help them make sense of this as a whole (Joyce et al., 2019, p. 2077).

Some participants reported having unique or complex struggles relating to their ED and its treatment. For these samples, a tailored, individualized treatment approach addressing these issues was particularly important. For example, in a sample of men, many found that services were “unable to acknowledge or provide space for them to talk about their unique struggles” because “programs were not tailored to their needs and preferences as men” (Thapliyal et al., 2020, p. 540).

3.4. Subtheme: Discharge from services

Finally, participants described being discharged from services when they reached their “target weight,” despite not feeling ready psychologically:

The focus was on physical restoration so when I was discharged at the “target weight,” I was still the same emotionally as when I was admitted (participant; Fogarty & Ramjan, 2016, p. 8).

You feel very alone, you put weight on and then you're told you can go when you're struggling the most with your weight (participant; Ross & Green, 2011, p. 114).

The description of “[feeling] very alone” stresses the lack of support felt by some participants. Some expressed how this inclination to discharge at a certain weight meant they felt at high risk of relapsing after discharge:

They did make me eat, they stopped me from dying. As for solving the problem, considering that 18 months later I was back where I started almost, that wasn't tackled at all (participant; Rother & Buckroyd, 2004, p. 157).

While this participant acknowledged that the service helped them, the solution was temporary and not enough to avoid relapse. Many participants suggested that because underlying psychological issues were not addressed in treatment, this ultimately led them to believe that “relapse … was inevitable” (Tierney, 2008, p. 370).

To summarize, participants perceived an overfocus on the physical symptoms of their ED at the cost of tackling the psychological difficulties driving their ED. Importantly, this was experienced throughout their involvement with ED services, from accessing support through to being discharged from services. There was an emphasis on the need for an individualized treatment approach when accessing services, particularly for those with unique struggles relating to their ED (e.g., male service users).

3.5. Service environment: The role of control within services

Many of the participants' narratives related to the role of control within services, and these experiences were often confusing, and at times conflicting. Although this was described in both inpatient and outpatient service experiences, the majority centred around inpatient experiences. The subthemes illustrate the shifts in control reported by participants and how control within services sometimes felt punitive.

3.6. Subtheme: Shifts in control during treatment

Some participants, including those reflecting on both inpatient and outpatient experiences, expressed that initially, letting go of and handing over control to the service provider was a difficult process:

It was very scary thinking if I come into treatment, I have to hand over all control the ED gave me. That made me feel very unsafe (participant; Smith et al., 2016, p. 20).

However, many reflected in hindsight that handing over control was something that “needed” to happen and overall, it was reported as a positive process:

Somebody took over and said this can't carry on you have to do this and I think at that time I needed it (participant; Ross & Green, 2011, p. 116).

Participants described this feeling of handing over control as a “relief” (Joyce et al., 2019, p. 2073) that served to “[lessen] the guilt” (participant; Offord et al., 2006, p. 382) they felt. Moreover, as treatment and recovery progressed, some participants described a care plan that allowed them to gradually regain control, which tended to be positively received:

Right at the beginning, when I was so seriously ill, I couldn't actually decide for myself … but later on, when I started getting well, I wanted to control things myself a little bit more (participant; Lindstedt et al., 2015, p. 5).

For many participants, this seemed to help with transitioning towards discharge from treatment, as it began to mirror “normal life.” There was an emphasis on the importance of gradually phasing back into the “real world,” as some described “difficulty transitioning from a medical/hospital environment back to day‐to‐day life outside of this setting” (Sheridan & McArdle, 2016, p. 1991). Getting the pace right in this shift in control was key for many participants. When a gradual transition did not occur, participants described difficulties adjusting back to having full control and freedom:

I'd been given all this freedom suddenly, I was like “well ok!” so I did try to experiment, and I just experimented a bit too much and… lost weight again (participant; Offord et al., 2006, p. 383).

Moreover, those who experienced ED services during adolescence reported that inpatient care had stunted their social development, setting them back in their transition to “normal life” and having full control:

I knew that I couldn't cope as an adult. Cos I'd been like hidden away from society so was still only a 14‐year‐old really, in my head (participant; Offord et al., 2006, p. 380).

Overall, participants suggested they needed balance across the shifts in control they experienced, and this required services to adopt an adaptive, individualized and collaborative approach to their treatment:

Complete control over treatment … was undesirable and … a combination of autonomy and direction was the balance that constituted a successful approach (Reid et al., 2008, p. 958).

(My treatment provider) allowed me to set the pace, meaning I felt a great sense of self‐satisfaction as I took charge of my own recovery (participant; Fogarty & Ramjan, 2016, p. 5).

Adopting a collaborative approach between service user and provider that acknowledged individual needs and preference in pace of treatment provided a sense of empowerment in recovery, and participants described they subsequently “more often wanted to comply” (Colton & Pistrang, 2004, p. 313). This emphasizes the need for a truly individualized approach, as seen previously in the “Treatment” theme, which subsequently facilitated engagement.

3.7. Subtheme: Control as punishment

Alongside reflection on how control changed during treatment, an overriding narrative for many participants was feeling punished by service providers when the services providers took control. This was particularly evident within the descriptions of some inpatient environments:

set treatment programs for patients with AN … were often perceived as inflexible and punishing (Offord et al., 2006, p. 381).

I felt punished if I didn't eat in a certain amount of time (participant; Walker & Lloyd, 2011, p. 546).

In multiple accounts, participants used language relating to feeling imprisoned and punished. Some described their experience of an inpatient environment as “prison‐like” (participant; Joyce et al., 2019, p. 2075), and participants referred to feeling “locked up” (participant; Escobar‐Koch et al., 2012, p. 261). Some participants reported “control being taken away in many non‐eating related areas of their life” (Offord et al., 2006, p. 382), and these restrictions were described as “disempowering” (Eli, 2014, p. 7). Such restrictive practices within some inpatient settings reinforced core ED beliefs that participants held:

I felt a very bad person like I was very unworthy of things, and like I should, I needed, I deserved to be punished. So the way I was treated when I was there was, to me, proof that I was being punished and, you know. So that was right really (participant; Offord et al., 2006, p. 382).

There probably is an atavistic sense of self punishment and lack of worth associated with ED, that the structure and nature of inpatient treatment exacerbates (participant; Joyce et al., 2019, p. 2075).

In summary, the current theme presents some conflicting yet significant experiences. In particular, the second subtheme of control being perceived as punishment seems to contradict the previous subtheme that reflects a more balanced letting go and gradual regaining of control. Offord et al. (2006) observed that, while some service users perceive services as over‐controlling at the time, retrospectively they acknowledged the restrictions imposed on them as “a necessary aspect of treatment” (Offord et al., 2006, p. 385). Interestingly, while this gaining of insight may be true for some individuals, the narrative of feeling punished was reported by participants describing both current and retrospective experiences, suggesting this insight may not be universally held, and may reflect quite different experiences.

3.8. Staff: Experiences with staff and the value of rapport

Participants described a wide spectrum of experiences with healthcare professionals involved in their treatment. Both negative and positive encounters were described, but importantly, these encounters played a significant role in treatment and recovery, over and above many other aspects of the service experience.

3.9. Subtheme: “Another anorexic”

The most prevalent negative experience of healthcare professionals was of those who treated them as an illness rather than a person, and being seen only as, “another anorexic coming through the unit on the ‘conveyor belt’ of anorexics” (Colton & Pistrang, 2004, p. 312). Participants described being talked about in a dehumanizing manner:

They see it as an eating problem, while that's the symptom … the person gets forgotten and we sit there and talk collectively about ED or [Severe and Enduring Eating Disorder] as opposed to the person who struggles for so many years with this illness (participant; Joyce et al., 2019, p. 2078).

Participants reported being viewed collectively as an illness, rather than as individuals, which related to a lack of individualized care, as “staff did not listen to them and tried only to fit them into theories” (Maine, 1985, p. 51). Again, this idea of individualized treatment is paramount to participants' narratives, mirroring the “Treatment” and “Service Environment” themes. Many noted that stereotyping tended to come from staff who did not specialize in EDs:

Untrained staff describe you as an ED … they have no trust in us really … hold grudges and go about bringing things up in front of other patients (participant; Patterson et al., 2017, p. 4).

There was agreement across accounts that services required more ED‐specialist training for all staff:

It was important that staff had the right levels of expertise, not because experts were expected to have the solution or cure, but because they knew enough to be sensitive about the concerns of ED patients (Reid et al., 2008, p. 959).

3.10. Subtheme: Staff consistency

One reason for encounters with “untrained” staff was due to the high turnover participants observed within services. Staff consistency played a significant role in participants' narratives:

The high turnover rate of inpatient staff … acted as a barrier to consistency and compassionate understanding, as staff were not provided with necessary training (Joyce et al., 2019, p. 2078).

Issues with staff consistency were closely linked to participants' feelings of trust which sometimes left them feeling vulnerable:

Since [current psychologist has] finished his training, I'm going to end up with another psychologist … it's like starting over, because it's really difficult for me to maintain trust with a psychologist (participant; Escobar‐Koch et al., 2012, p. 258).

3.11. Subtheme: Hopelessness versus hopefulness

Participants also reflected on a sense of staff feeling hopeless about their ED, which impacted on their perceptions of recovery:

I very much got the message from the ED service that an ED was something I managed for the rest of my life … and I didn't even know like you could ever get fully better (participant; Rance et al., 2017, p. 589).

This hopelessness narrative was particularly pertinent for samples of participants with chronic anorexia nervosa:

Experiences of being passed around different services, especially non‐eating‐disorders services (e.g. medical wards), engendered feelings of hopelessness and a sense of being abandoned by professionals (Fox & Diab, 2015, p. 33).

Conversely, when staff instilled hope, it was perceived to motivate participants in recovery:

We all want to know that we can beat this and that there is a life that doesn't involve [Anorexia Nervosa] (participant; Fogarty & Ramjan, 2016, p. 4).

Instilling hope may be perceived as particularly important to participants with more complex needs, such as chronic anorexia nervosa. When hopefulness was not present, this could hinder recovery and “reinforced their wish to ‘stay with the anorexia’” (Fox & Diab, 2015, p. 33). This links back to concepts observed in the “Service Environment” theme, whereby ED beliefs were reinforced by their service experiences, highlighting a complex relationship between the ED and the provisions of an ED service.

3.12. Subtheme: Being seen as an individual

For many participants, feeling understood and validated by staff was, unsurprisingly, positively received. Participants appreciated when staff could separate the individual from their ED:

They are quite good at seeing you as an individual and they do like to get to know you without your ED (participant; Smith et al., 2016, p. 22).

She helped me to see how the anorexic side of me was being really harsh on the normal side of me (participant; Fox & Diab, 2015, p. 32).

This emphasizes the running narrative of positive service experiences being facilitated by an individualized approach. Staff who showed compassion, understanding and empathy were felt to have a positive impact on participants' lives. It is important to stress the significance of these traits as they were often key in motivating participants to comply with treatment and feel empowered to recover:

When treated by specialists they felt more empathy and understanding and were more motivated to continue with treatment (Walker & Lloyd, 2011, p. 545).

When they're more encouraging and supportive it makes me want to try harder (participant; Colton & Pistrang, 2004, p. 313).

The specific therapeutic interventions received by the service users, such as cognitive behavioural therapy (Rance et al., 2017), were described by very few participants. The dominant narratives were around the therapeutic alliances built and rapports developed with healthcare professionals, suggesting that this may be as important as—if not more than—the treatment approach itself:

Participants agreed that being able to communicate and feeling a connection with your therapist, having a rapport, and not feeling judged were all important determinants as to whether they would stay in treatment, regardless of the treatment modality (Walker & Lloyd, 2011, p. 544).

In summary, negative experiences of healthcare professionals included being viewed as a stereotypical “anorexic”—typically by those without specialist ED training—rather than being seen as an individual. Participants also implicated that high rates of staff turnover jeopardized trust in healthcare professionals, hindering recovery. Healthcare professionals perceived as expressing hopelessness for recovery were felt to be detrimental to prognosis. Conversely, positive staff traits included taking an empathetic, individualized approach to care, being able to separate the ED from the individual and instilling hope in service users.

3.13. Peer influence: Camaraderie versus comparison

Due to the high number of inpatient experiences reported, a significant influence on participants' service experiences included being in close proximity with peers with an ED. Participants reported conflicting experiences, with some suggesting it was helpful, and others feeling it was detrimental to their recovery.

3.14. Subtheme: Support from peers

Some participants spoke of the power of peer support, through a shared understanding of what others were going through. For some, this support was reported as more helpful than support from family or healthcare professionals:

Nobody is looking at you or judging you … they know exactly what you are going through … it is just almost understood (participant; Smith et al., 2016, p. 22).

You can see in their eyes that they are feeling exactly the same (participant; Joyce et al., 2019, p. 2076).

This shared understanding extended to a sense of belonging for many participants; something that some spoke of striving for throughout their lives:

She felt mutual understanding and belonging for the first time in her adolescent and adult life (Eli, 2014, p. 5).

A sense of belonging with peers was particularly significant due to feelings of isolation and loneliness that the ED perpetuated; a feeling that was also highlighted in the “Treatment” theme. Participants described how the ED made them feel “so alone, because [they] felt that no one understood what [they were] feeling” (participant; Eli, 2014, p. 5), so finding a “sense of camaraderie between patients experiencing a similar transformation” (participant; Patterson et al., 2017, p. 4) was a powerful and cathartic experience for some.

However, it is important to note that this was not the case for all participants. In a sample of male participants, they described often being the only male in their treatment setting, which “contributed further to a sense of loneliness and isolation” (Thapliyal et al., 2020, p. 540). This suggests that in some cases where individuals do not relate to their peers, feelings of isolation can be exacerbated by being around others, further emphasizing the running idea of needing tailored, individualized support.

3.15. Subtheme: Distress caused by peers

Despite the reported benefits of peers, many participants also spoke about its disadvantages. Participants described the tendency to compare themselves to others, creating a competitive environment:

I feel I was living in a space full of comparison, everything would be compared between us. They (peers) compared things like whose was larger or smaller, who ate more or less, who gained weight faster or slower (participant; Wu & Harrison, 2019, p. 5).

Spending time with others also led to learning new ED behaviours for some participants:

I didn't really know … about pacing to stop your weight going up, you know, walking around, exercise. I soon cottoned on (participant; Colton & Pistrang, 2004, p. 311).

Discovering new ED behaviours and constantly comparing oneself to others subsequently worsened some participants' illness. Participants described fearing “being seen as ‘greedy’ or overweight … [resulting] in a desire for further weight loss” (Smith et al., 2016, p. 23). One participant described this experience as feeling like she was “being dragged back more than going forward” (participant; Eli, 2014, p. 6). This conflicting experience of peer influence tended to be the case across multiple accounts, regardless of other factors, such as age.

In summary, being in an inpatient setting was described as a “unique social environment” (Eli, 2014, p. 5), evident through narratives of both negative and positive peer influence. For some, the presence of others in a similar situation “functioned as a core element of treatment” (Eli, 2014, p. 5). For others, it was depicted as “[intensifying their] illness” (Eli, 2014, p. 5). Again, there are individual differences impacting peer influence, highlighting the importance of adopting individualized approaches.

4. DISCUSSION

The aim of this meta‐synthesis was to gain an understanding of ED service experiences by exploring the perspectives of service users. This is the first meta‐synthesis to focus exclusively on the service experiences of ED service users. Twenty‐two qualitative studies were selected with a total of 712 participants who were identified as past or present ED service users. Four overarching themes were identified: “Treatment: Focus on physical vs. psychological symptoms”; “Service Environment: The role of control within services”; “Staff: Experiences with staff and the value of rapport”; and “Peer Influence: Camaraderie vs. comparison.” The findings of this meta‐synthesis emphasize servicer users' need for individualized care within ED treatment settings, with a desire for more psychological support from specialist ED healthcare professionals. It is also apparent that the role of peers and perceived shifts in control throughout treatment play an important part in recovery.

Our findings support some of the findings of the systematic review by Johns et al. (2019) relating to the overfocus on physical symptoms within services, the value of collaboration in treatment, and the importance of rapport and understanding from staff. Furthermore, our broad selection criteria has allowed us to build on Johns et al. (2019)'s work, addressing their limitations and producing a more detailed, explicit understanding of the ED service user experience as a whole.

Our findings demonstrate that service users experienced professionals as seeming to lack specialist ED training and/or using eating disorder stereotypes. These findings complement those found by Graham et al. (2020) in their meta‐ethnography of ED healthcare professionals' experiences in which healthcare professionals experienced their work as emotionally draining, leading to burnout. It has been suggested that to cope with these pressures, ED staff may turn to “depersonalizing” service users, that is, seeing them as a collective to relieve the strain of meeting individual needs (Fox et al., 2012). This may explain why service users described a lack of individualized care and reported being seen as “another anorexic.” Fox et al. (2012) highlight that there is an irony in the lack of specialist ED training for those spending the most time with service users (e.g., nurses and healthcare assistants). They may consequently rely on stereotypical portrayals of EDs to understand service users. The findings of the current meta‐synthesis emphasize the need for more ED training across all disciplines, but particularly for frontline workers within these services.

Moreover, the importance of staff consistency was a common theme across studies, and participants reported that a high turnover of staff diminished their trust within services. While there are many reasons why someone might leave a role in any setting, it is important to acknowledge that this may have additional consequences within a clinical setting. Relational continuity—an ongoing relationship between the service user and one healthcare professional—has been reported in the literature to be particularly salient within mental health services and can promote safety and trust in the service's ability to provide adequate treatment and care (Biringer et al., 2017; Green et al., 2008). This study highlights the importance of ensuring a smooth and comprehensive transition, should a service user's care need to be handed over to another professional, to promote continuity of care and sustain trust within the ED service.

Our meta‐synthesis highlighted a perceived overfocus on physical symptoms of an ED (e.g., weight, food intake) at the cost of understanding and tackling the psychological underpinnings of disordered eating. This was experienced throughout the service experience: from accessing services, through treatment and at discharge. This perceived minimization of the psychological impact of the ED was described to increase risk of relapse or engrain the ED further. Graham et al. (2020) propose that ED healthcare professionals may develop a dependence on using safe and certain measures such as weight restoration via the safe‐certainty model proposed by Mason (1993). ED healthcare professionals may seek a position of safe‐certainty (Fox et al., 2012)—that is, the intervention used will be the safest option (e.g., prevent death) and has a relatively certain outcome (i.e., re‐feeding will lead to weight restoration). Indeed, in some cases, this is absolutely necessary. However, Mason (1993) calls for a position of safe‐uncertainty to be adopted within therapeutic settings. The safe‐certain approach tends to be fixed and constrained, subsequently limiting healthcare professionals' expertise due to seeking certainty and not being open to novel ideas. In contrast, the safe‐uncertain position allows healthcare professionals to take a more flexible, collaborative approach to treatment that follows an evolving narrative with the service user and promotes individualized care through a more investigational process. For example, it is well documented that early intervention in ED treatment is paramount for a more successful prognosis (Nazar et al., 2017; Treasure et al., 2015; Treasure & Russell, 2011), yet the current findings suggest there are still significant gaps in access to treatment. This was reported to be partly due to the rigid, weight‐dependent protocol dictating access to and discharge from services. Taking a safe‐uncertain position across services may allow for a more individualized, holistic approach, rather than relying on body‐mass index targets. This safe‐uncertain approach also mirrors aspects of care, such as collaboration and individualization, that service users held in high regard in our findings. In practice, it may be that adopting a more flexible approach, such as the one described above, is currently unachievable due to the lack of available funding and resources reported by those working within ED services (Koskina et al., 2012), leading to a reliance on safe‐certain approaches to safely manage risk. This support is described as being essential in order for services to improve their practice and implement this kind of approach effectively (Koskina et al., 2012).

The role of control in ED services was a dominant theme within our results. Perception of control is a significant but complex phenomenon that both drives and maintains an ED (Fairburn et al., 1999; Froreich et al., 2016; Schmidt & Treasure, 2006; Slade, 1982), and this can extend into treatment settings and negatively affect prognosis (Jarman et al., 1997). Our findings build a complex and conflicting picture of the relief of letting go of and the importance of gradually regaining control, together with professionals largely taking control. It appeared that some service users retrospectively gained insight into their experiences and recognized the necessity of taking away control at the time of treatment. However, this gaining of insight was not the case for all participants, as some still reported perceiving the control imposed on them as punitive regardless of whether their experiences were current or retrospective.

These findings reinforce the importance of individualized care within ED services, as we can theorize that some individuals are more affected by perceived shifts in control during their treatment and less able to cope with these changes. While the data did not explicitly tell us where these individual differences lie, we can hypothesize where some of these might be from existing literature. For example, vulnerability to obsessive–compulsive disorder, which is highly prevalent in ED populations (Kaye et al., 2004), has been linked to perceived control, exhibiting similar patterns to those with disordered eating behaviours (Froreich et al., 2016). Furthermore, qualitative accounts from autistic women with anorexia nervosa suggest that a need for control was a significant maintaining factor for their ED and affected their ability to engage with treatment (Babb et al., 2021; Brede et al., 2020). For these individuals, handing over control could be particularly distressing and perceived more negatively, and this should be considered in service provision.

There are important clinical implications relating to the role of control within treatment settings. Research suggests that the sense of control an ED provides can be a strong maintaining factor, leading individuals to value their ED (Schmidt & Treasure, 2006) and become resistant to change in treatment settings (Abbate‐Daga et al., 2013). Motivational Interviewing techniques (Rollnick & Allison, 2004) have been utilized in ED services to challenge treatment resistance (Macdonald et al., 2012). Crucially, the technique of “rolling with” resistance, rather than opposing it, may be particularly helpful where the service user is feeling ambivalent about change and the perceived loss of control. Opposing resistance could be counter‐therapeutic as it is likely to reinforce resistance and decrease likelihood of behaviour change (Miller & Moyers, 2006). We hypothesize that using these techniques may be particularly applicable for individuals demonstrating ambivalence relating to control recognized in our results.

Motivational Interviewing endorses a collaborative approach between service user and clinician (Miller & Rollnick, 2012). Collaboration was described as empowering in service users' treatment experiences, yielding further endorsement for using these techniques. Our findings suggest that perceptions of control vary across individuals and some may be more susceptible to treatment resistance due to perceived loss of control than others. For those exhibiting resistance to treatment, Motivational Interviewing could facilitate the process of change. Some studies have suggested that motivational‐based interventions are not effective at enhancing motivation or ED treatment outcomes (Waller, 2012). However, other studies have reported value and benefit in the delivery of brief motivational sessions, when compared with clearly non‐motivational approaches such as psychoeducation (Denison‐Day et al., 2018). Moreover, evidence‐based therapeutic approaches for EDs such as enhanced Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT‐E) and the Maudsley Model for Treatment of Adults with Anorexia Nervosa (MANTRA) incorporate a clear, motivational component, implicating its importance as an element of the full treatment model for EDs (Denison‐Day et al., 2018). MANTRA also emphasizes the importance of readiness to change and setting the pace of intervention (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, 2017), which reflects the collaborative approach valued by service users.

The influence of peers with an ED was a salient theme within service users' narratives, and these experiences were often conflicting. “Peer contagion” is a term used to describe the adverse social learning processes of imitation, identification and competition observed in ED inpatient services. There has previously been a particular focus on adolescent service users (Vandereycken, 2011). Our meta‐synthesis found similar narratives were expressed by adults. Contrary to the peer contagion concept, recent developments stress the potential effectiveness of peer mentoring within ED treatment settings, whereby recovered individuals become mentors for individuals receiving ED treatment (Hanly et al., 2020; Ramjan et al., 2017). Our results support the notion that peer influence can have a positive impact on recovery, and it could be that providing an aspect of peer support within a service is key to a more successful prognosis.

Within our results, many participants reported similar ED service experiences. However, there seemed to be an additional layer of difficulty or complexity for certain participant samples. For example, male samples reported a lack of understanding about the male experience of EDs, describing the isolation felt by often being the only male in the service. This is supported by a recent synthesis which reported a lack of understanding about subtle gender differences in ED presentations (e.g., a drive for muscularity rather than thinness), which may require different treatment approaches (Murray et al., 2017). Moreover, participants with a chronic anorexia nervosa presentation seemed to have a particular emphasis on their perceptions of staff feeling hopeless about their ED. Research indicates that by instilling hope, clinicians can enhance therapeutic alliance and treatment outcomes in individuals with severe and enduring presentations of anorexia nervosa (Stiles‐Shields et al., 2016). Finally, we observed that some adolescent service users highlighted a perceived interruption in their development when transitioning back into the community after an inpatient admission. These additional reported difficulties for certain groups of service users emphasize the running theme of a need for an individualized approach. Research suggests that some populations have unique treatment needs relating to their ED, for example, autistic individuals (Babb et al., 2021; Brede et al., 2020), those with diabetes (Macdonald et al., 2018) and ethnic minorities (Kronenfeld et al., 2010). Adopting an individualized approach could help to overcome and meet these treatment needs.

4.1. Limitations

There were some biases in demographics across selected papers for the meta‐synthesis. For example, a large proportion focused solely on inpatient experiences (45% of papers, compared to 9% of papers focusing solely on outpatient experiences), included service users with a primary diagnosis of anorexia nervosa (at least 41% of participants; possibly higher as some papers did not report exact figures), and were female (97% of participants). Subsequently, the experiences reported by these participants may not represent the general ED population. There was also a lack of reporting some demographics, such as ethnic background and sexuality in the papers. While our understanding of EDs within ethnic and sexual/gender minorities is expanding, this is still under‐researched (Calzo et al., 2017; McClain & Peebles, 2016; Perez et al., 2019; Rodgers et al., 2018) and reporting these demographics in ED research can help us to understand these populations further.

A limitation of the review is that the majority of data screening and analysis was completed by one researcher. This was somewhat addressed by utilizing independent researchers to undertake quality checks during the screening process and quality appraisals. There was also involvement from the wider research team later in the analysis process. However, due to the subjective nature of the review, the meta‐synthesis could have been improved by involving more than one researcher throughout the analysis process to avoid reliance on a single analyst driving the development of the themes.

It is also important to note that not all papers stated the diagnostic manual used to define the EDs received by participants, and in some cases, the type of ED was not defined at all (e.g., Escobar‐Koch et al., 2010). For consistency and validity, it may have been appropriate to exclude papers that did not include this information. However, for this review we decided to take a more inclusive stance to represent a range of different ED diagnoses and presentations.

5. CONCLUSION

This is the first meta‐synthesis to focus solely on service user experiences of ED services. We identified 22 papers spanning eight countries and involving 712 ED service users. We developed four overarching themes depicting service user experiences of ED services. The results portray the conflicts and complexities that service users encounter in ED services. We also highlight some important clinical implications for ED services to consider. For example, a running theme throughout the results emphasizes the importance of adopting an individualized, collaborative approach within these services to ensure that individuals are receiving appropriate and tailored care.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflict to declare.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank Kate Anning and Janina Brede for their assistance with article screening and quality appraisal ratings. The PhD studentship was funded by Autistica (7252). The funder had no involvement in the study design and analysis, writing of the manuscript, and in the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Babb, C. , Jones, C. R. G. , & Fox, J. R. E. (2022). Investigating service users' perspectives of eating disorder services: A meta‐synthesis. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 29(4), 1276–1296. 10.1002/cpp.2723

REFERENCES

- Abbate‐Daga, G. , Amianto, F. , Delsedime, N. , De‐Bacco, C. , & Fassino, S. (2013). Resistance to treatment and change in anorexia nervosa: A clinical overview. BMC Psychiatry, 13(1), 294. 10.1186/1471-244X-13-294 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babb, C. , Brede, J. , Jones, C. R. , Elliott, M. , Zanker, C. , Tchanturia, K. , Serpell, L. , Mandy, W. , & Fox, J. R. (2021). ‘It's not that they don't want to access the support… it's the impact of the autism’: The experience of eating disorder services from the perspective of autistic women, parents and healthcare professionals. Autism, 25(5), 1409–1421. 10.1177/1362361321991257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biringer, E. , Hartveit, M. , Sundfør, B. , Ruud, T. , & Borg, M. (2017). Continuity of care as experienced by mental health service users—A qualitative study. BMC Health Services Research, 17(1), 1–15. 10.1186/s12913-017-2719-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V. , & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V. , & Clarke, V. (2013). Successful qualitative research: A practical guide for beginners. Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Brede, J. , Babb, C. , Jones, C. , Elliott, M. , Zanker, C. , Tchanturia, K. , Serpell, L. , Fox, J. , & Mandy, W. (2020). “For me, the anorexia is just a symptom, and the cause is the autism”: Investigating restrictive eating disorders in autistic women. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 50(12), 4280–4296. 10.1007/s10803-020-04479-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burman, E. , & Parker, I. (1993). Discourse analytic research: Repertoires and readings of texts in action. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Calzo, J. P. , Blashill, A. J. , Brown, T. A. , & Argenal, R. L. (2017). Eating disorders and disordered weight and shape control behaviors in sexual minority populations. Current Psychiatry Reports, 19(8), 49. 10.1007/s11920-017-0801-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castellini, G. , Lo Sauro, C. , Mannucci, E. , Ravaldi, C. , Rotella, C. M. , Faravelli, C. , & Ricca, V. (2011). Diagnostic crossover and outcome predictors in eating disorders according to DSM‐IV and DSM‐V proposed criteria: A 6‐year follow‐up study. Psychosomatic Medicine, 73(3), 270–279. 10.1097/PSY.0b013e31820a1838 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chesney, E. , Goodwin, G. M. , & Fazel, S. (2014). Risks of all‐cause and suicide mortality in mental disorders: A meta‐review. World Psychiatry, 13(2), 153–160. 10.1002/wps.20128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colton, A. , & Pistrang, N. (2004). Adolescents' experiences of inpatient treatment for anorexia nervosa. European Eating Disorders Review: The Professional Journal of the Eating Disorders Association, 12(5), 307–316. 10.1002/erv.587 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Critical Appraisal Skills Programme . (2018). CASP Qualitative Checklist. https://casp-uk.net/casp-tools-checklists/

- Crook, M. , Hally, V. , & Panteli, J. (2001). The importance of the refeeding syndrome. Nutrition, 17(7–8), 632–637. 10.1016/S0899-9007(01)00542-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crossley, M. (2000). Introducing narrative psychology. McGraw‐Hill Education (UK). [Google Scholar]

- Crossley, M. (2007). Narrative analysis. Analysing Qualitative Data in Psychology, 131–144. [Google Scholar]

- Denison‐Day, J. , Appleton, K. M. , Newell, C. , & Muir, S. (2018). Improving motivation to change amongst individuals with eating disorders: A systematic review. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 51(9), 1033–1050. 10.1002/eat.22945 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eli, K. (2014). Between difference and belonging: Configuring self and others in inpatient treatment for eating disorders. PLoS ONE, 9(9), e105452. 10.1371/journal.pone.0105452 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Escobar‐Koch, T. , Banker, J. D. , Crow, S. , Cullis, J. , Ringwood, S. , Smith, G. , van Furth, E. , Westin, K. , & Schmidt, U. (2010). Service users' views of eating disorder services: An international comparison. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 43(6), 549–559. 10.1002/eat.20741 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Escobar‐Koch, T. , Mandich, C. C. , & Urzúa, R. F. (2012). Treatments for eating disorders: The patients' views. Relevant Topics in Eating Disorders, 12(1). 10.5772/32699 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fairburn, C. G. , Cooper, Z. , & Shafran, R. (2003). Cognitive behaviour therapy for eating disorders: A “transdiagnostic” theory and treatment. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 41(5), 509–528. 10.1016/S0005-7967(02)00088-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairburn, C. G. , Shafran, R. , & Cooper, Z. (1999). A cognitive behavioural theory of anorexia nervosa. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 37(1), 1–13. 10.1016/S0005-7967(98)00102-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finfgeld, D. L. (2003). Metasynthesis: The state of the art—So far. Qualitative Health Research, 13(7), 893–904. 10.1177/1049732303253462 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fogarty, S. , & Ramjan, L. M. (2016). Factors impacting treatment and recovery in anorexia nervosa: Qualitative findings from an online questionnaire. Journal of Eating Disorders, 4(18), 18. 10.1186/s40337-016-0107-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox, J. R. , Dean, M. , & Whittlesea, A. (2017). The experience of caring for or living with an individual with an eating disorder: A meta‐synthesis of qualitative studies. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 24(1), 103–125. 10.1002/cpp.1984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox, J. R. , & Diab, P. (2015). An exploration of the perceptions and experiences of living with chronic anorexia nervosa while an inpatient on an eating disorders unit: An interpretative phenomenological analysis (IPA) study. Journal of Health Psychology, 20(1), 27–36. 10.1177/1359105313497526 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox, J. R. , & Goss, K. (2012). Working with special populations and service‐related issues. In Eating and its disorders (pp. 341–343). Wiley‐Blackwell. 10.1002/9781118328910.ch22 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fox, J. R. , Woodrow, C. , & Leonard, K. (2012). Working with anorexia nervosa on an eating disorders inpatient unit: Consideration of the issues. In Eating and its disorders (pp. 344–359). Wiley‐Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Froreich, F. V. , Vartanian, L. R. , Grisham, J. R. , & Touyz, S. W. (2016). Dimensions of control and their relation to disordered eating behaviours and obsessive‐compulsive symptoms. Journal of Eating Disorders, 4(1), 14. 10.1186/s40337-016-0104-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gale, N. K. , Heath, G. , Cameron, E. , Rashid, S. , & Redwood, S. (2013). Using the framework method for the analysis of qualitative data in multi‐disciplinary health research. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 13(1), 1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glaser, B. G. , & Strauss, A. L. (1967). The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. Aldine. [Google Scholar]

- Goss, K. , & Fox, J. R. (2012). Introduction to clinical assessment for eating disorders. In Eating and its disorders (pp. 1–10). Wiley‐Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Graham, M. R. , Tierney, S. , Chisholm, A. , & Fox, J. R. (2020). The lived experience of working with people with eating disorders: A meta‐ethnography. International Journal of Eating Disorders., 53(3), 422–441. 10.1002/eat.23215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green, C. A. , Polen, M. R. , Janoff, S. L. , Castleton, D. K. , Wisdom, J. P. , Vuckovic, N. , Perrin, N. A. , Paulson, R. I. , & Oken, S. L. (2008). Understanding how clinician‐patient relationships and relational continuity of care affect recovery from serious mental illness: STARS study results. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 32(1), 9–22. 10.2975/32.1.2008.9.22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanly, F. , Torrens‐Witherow, B. , Warren, N. , Castle, D. , Phillipou, A. , Beveridge, J. , Jenkins, Z. , Newton, R. , & Brennan, L. (2020). Peer mentoring for individuals with an eating disorder: A qualitative evaluation of a pilot program. Journal of Eating Disorders, 8(1), 29. 10.1186/s40337-020-00301-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hetterich, L. , Mack, I. , Giel, K. E. , Zipfel, S. , & Stengel, A. (2019). An update on gastrointestinal disturbances in eating disorders. Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology, 497, 110318. 10.1016/j.mce.2018.10.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill, C. E. , Thompson, B. J. , & Williams, E. N. (1997). A guide to conducting consensual qualitative research. The Counseling Psychologist, 25(4), 517–572. [Google Scholar]

- Holloway, I. , & Galvin, K. (2016). Qualitative research in nursing and healthcare. John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Holsti, O. R. (1968). Content analysis. The Handbook of Social Psychology, 2, 596–692. [Google Scholar]