Abstract

Background

Among Chinese college students, the burden of depression is considerably high, affecting up to 30 % of the population. Despite this burden, few Chinese students seek mental health treatment. In addition, depression is highly comorbid with other mental health disorders, such as anxiety. Scalable, transdiagnostic, evidence-based interventions are needed for this population.

Objective

The study will evaluate the effectiveness of a World Health Organization transdiagnostic digital mental health intervention, Step-by-Step, to reduce depressive and anxiety symptoms and improve well-being compared with enhanced care as usual and its implementation in a Chinese university community.

Methods

A type 1 effectiveness-implementation two-arm, parallel, randomized controlled trial will be conducted. The two conditions are 1) the 5-session Step-by-Step program with minimal guidance by trained peer-helpers and 2) psychoeducational information on depression and anxiety and referrals to local community services. A total of 334 Chinese university students will be randomized with a 1:1 ratio to either of the two groups. Depression, anxiety, wellbeing, and client defined problems will be assessed at pre-intervention, post-intervention, and 3-month follow-up. Endline qualitative interviews and focus group discussions will be conducted to explore SbS implementation among service users, university staff, and stakeholders. Data will be analysed based on the intent-to-treat principle.

Discussion

Step-by-Step is an innovative approach to address common mental health problems in populations with sufficient digital literacy. It is a promising intervention that can be embedded to scale mental health services within a university setting. It is anticipated that after successful evaluation of the program and its implementation in the type 1 hybrid design RCT study, Step-by-Step can be scaled and maintained as a low-intensity treatment in universities, and potentially extended to other populations within the Chinese community.

Trial registration

ChiCTR2100050214.

Abbreviations: AE, adverse event; CONSORT, Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials; CSQ, Client Satisfaction Questionnaire; DASS-21, Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scale – 21 items; ECAU, enhanced care as usual; GAD-7, Generalized Anxiety Disorder; ITT, intention-to-treat; PCL, PTSD Checklist for DSM-5; PCC, Psychological Counselling Center; PHQ, Patient Health Questionnaire; PSYCHLOPS, Psychological Outcomes Profile Instrument; RCT, randomized controlled trial; RE-AIM, Reach, Effectiveness, Adoption, Implementation, and Maintenance; SAE, serious adverse event; SbS, Step-by-Step; SPIRIT, Standard Protocol Items: Recommendations for Interventional Trials; WHO, World Health Organization

Keywords: Depression, Behavioral activation, Digital intervention, College students, Implementation, Randomized controlled trial

Highlights

-

•

A protocol for a hybrid type 1 digital mental health intervention trial is reported.

-

•

The study population will be Chinese young adults enrolled in university.

-

•

The trial will compare psychoeducation to Step-by-Step a WHO digital intervention.

-

•

Stakeholders evaluation will focus on long-term scalability within universities.

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

Depression is among the most common mental health problems worldwide (World Health Organization, 2017). According to The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM–5; American Psychiatric Association, 2013), major depressive disorder (MDD) is a stress-related mental disorder mainly characterized by loss of interest and depressed mood. Young adults are vulnerable to stress, and a recent meta-analysis of 113 studies with 185,787 university students revealed that the prevalence of depression among Chinese college students is approximately 28.4 % (Gao et al., 2020). According to a recent report, the prevalence of depression in Macao university students was even higher than in mainland China (35.2 % vs. 16.8 %; Li et al., 2020). In addition, depression is highly comorbid with anxiety (Gorman, 1996), which is comparatively prevalent with depression among young adults (Gao et al., 2021; Mao et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2020). If not treated, MDD can lead to adverse outcomes such as substance abuse (Hunt et al., 2020), suicidal ideation, attempt, or completion (Conejero et al., 2018), lower quality of life (Kolovos et al., 2016) and even physical health related comorbidities (Sartorius, 2018).

According to the World Health Organization (World Health Organization, 2016), digital health refers to “the use of digital, mobile, and wireless technologies to support the achievement of health objectives.” Internet, computer, and mobile phones are the main technologies utilized for digital mental health interventions (Lattie et al., 2019). Several reviews identified existing digital mental health interventions and evaluated these programs (Lattie et al., 2019; Liem et al., 2020b; Weisel et al., 2019) and the majority of the interventions were at least partially effective in improving symptoms or well-being among college students (Lattie et al., 2019). App-supported smartphone-based interventions significantly reduced depressive and anxiety symptoms, stress, and improved quality of life (Harrer et al., 2018; Linardon et al., 2019). Smartphone app-based interventions for depression demonstrated a small-to-medium effect size (g = 0.28, 95 % CI = 0.21–0.36). Behavioral activation is an effective approach to motivate people to become active in daily routine by scheduling activities that improve their mood, and interventions based on this approach were not inferior to other types of in-person treatment, such as cognitive therapy (g = 0.14, 95 % CI = −0.02 - 0.30) (Cuijpers et al., 2017; Linardon et al., 2019). Moreover, smartphone behavioral activation was more effective in reducing depressive symptoms in populations with clinical depression than app-supported mindfulness treatment (Ly et al., 2014). Ly et al. (2014) also found that these treatment effects were maintained at the 6-month follow-up. Due to the limited number of mental health professionals and high prevalence of common mental health disorders among students, a solution that is scalable, transdiagnostic, and evidence-based is essential.

Step-by-Step (SbS), a WHO digital mental health intervention, was designed to primarily address depression, and also expected to be transdiagnostic, such that it addresses other common mental health disorders. The core therapeutic component of Step-by-Step is behavioral activation (Carswell et al., 2018; Dawson et al., 2015). It has undergone technical adaptation for Syrian refugees in Germany, Sweden, and Egypt (Burchert et al., 2019), culturally adapted for Overseas Filipino workers (OFWs) (Garabiles et al., 2019), Syrian refugees, Lebanese, and Palestinians in Lebanon (Abi Ramia et al., 2018), and Chinese young adults (Sit et al., 2020) and showed promising preliminary results in these populations (Harper Shehadeh et al., 2019; Heim et al., 2021; Sit et al., 2022).

Effectiveness of treatment is commonly evaluated quantitatively utilizing randomized controlled trials (Chowdhary et al., 2014; Harper Shehadeh et al., 2016; Lattie et al., 2019). However, these trials often neglect to include scale-up and maintenance of these interventions as a part of the trial planning. Therefore, interventions which are effective may not fully reach their potential and reduce mental health challenges. Implementation science approaches center implementation as a part of the key evaluation component of interventions, with the aim to change practice settings to include the innovation long term (Bauer and Kirchner, 2020). A type 1 hybrid effectiveness-implementation randomized controlled trial study examines the effectiveness of a clinical intervention while investigating its delivery during the trial or/and implementation in the real world with an emphasis on effectiveness of the trial (Curran et al., 2012; Landes et al., 2019).

The RE-AIM model, a framework for implementation evaluation, consists of five dimensions: reach, effectiveness, adoption, implementation, and maintenance, and allows researchers to thoroughly evaluate the program at an individual level and institutional level (Glasgow et al., 2019; Glasgow et al., 1999). The model was developed to access the potential of an intervention being used long-term in real-life settings and has been widely used as a planning and evaluation model today (Holtrop et al., 2018). A recent study protocol adopted the RE-AIM model to evaluate Step-by-Step among Filipino migrant workers (Liem et al., 2020a).

1.2. Aims and hypotheses

The current study will adopt a type 1 hybrid design to examine the effectiveness of Step-by-Step on affective symptoms and evaluate its implementation in the university setting. The primary outcome of the trial is depressive symptom severity, and secondary outcomes include anxiety symptom severity, self-defined difficulties, and subjective well-being.

The primary hypotheses is: 1) the change of PHQ-9 scores between pre- and post- treatment will be greater than zero in SbS and this change will be greater than the change in scores within the enhanced care as usual (ECAU).

The secondary hypotheses are: 1) the effect of SbS on depressive symptoms will be maintained at 3-month follow-up; 2) SbS is more effective in alleviating anxiety symptoms, self-defined difficulties, and improving subjective well-being by post-test, compared with the ECAU group; 3) SbS group showed greater service satisfaction, compared with the ECAU; 4) the effect of SbS on anxiety symptoms, subjective well-being, and self-defined difficulties will be maintained at 3-month follow-up 5) the implementation of SbS is successful, reflected by participants' and stakeholders' feedback.

1.3. Study design

A type 1 effectiveness-implementation two-arm, parallel, randomized controlled trial will be conducted to examine the effectiveness and implementation of Step-by-Step for Chinese young adults with elevated depressive symptoms in Macau (SAR), China. Eligible participants will be recruited for the standard intervention (SbS) and ECAU. Assessment will occur at pre-intervention (week 0), during the intervention (week 1–7; PHQ-9 only), post-intervention (week 8), and three-month follow-up (week 20), administered via questionnaires embedded in the intervention app. Questions from qualitative interviews/focus group discussions will be designed based on RE-AIM framework and qualitative interviews/focus group discussion will be conducted to understand the effectiveness and long-term implementation of the intervention from participants and stakeholders. The current protocol is prepared based on the recommendation of SPIRIT guideline (Chan et al., 2013).

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

2.1.1. Eligible criteria

Participants who meet the following criteria will be included: 1) at least 18 years old; 2) registered student in a university in Macao 3) Chinese citizen or Macao resident; 4) native proficiency in Cantonese or Mandarin; 5) have a digital device (e.g., smartphone); 6) have internet access; and 7) PHQ-9 score ≥ 5 on PHQ-9, indicating mild but clinically significant depressive symptoms.

Participants who meet the following criteria will be excluded: 1) aged below 18 or above 30 years old; 2) currently or in the past 3 months received psychological treatment; 3) had had serious thoughts or a plan to end their life in the past month.

2.1.2. Setting and recruitment

Potential participants will be recruited through multiple channels within the university setting, which includes 1) referral from the Psychological Counselling Center (PCC) of the university based on a stepped care model according to students' annual mental health screening. Students who met the all of three criteria 1) the 21-item Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scale (DASS-21)-depression score < 21, 2) PTSD checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5) score < 51, and 3) PCL re-experiencing subscale score ≥ 15, PCL avoidance subscale score ≥ 21, PCL hyperarousal subscale score ≥ 15, DASS-anxiety subscale score ≥ 15, or DASS-stress subscale ≥ 26 at the time of the annual screening will be referred to this program, while those screened for higher levels of symptoms will receive face-to-face treatment offered by the PCC 2) online and offline advertisement, promotional events, and seminars within residential colleges at the university.

Participants will be provided with information about the study and a QR code that they can scan to access the mobile application. When they logon, they will receive a complete description of the study. They will receive electronic informed consent before being screened for inclusion criteria and randomized to either the SbS group or psychoeducation control group. As part of the consent process during the screening stage, participants will be informed that this is an intervention study where they will be assigned to different treatment groups.

2.2. Interventions

2.2.1. Overview

The mobile app will randomly assign eligible participants to two conditions, which are a 5-session Step-by-Step program with minimal guidance and psychoeducational information on common mental disorders and referral to local community services.

2.2.2. Intervention group

2.2.2.1. Step-by-Step

Step-by-Step was developed by the World Health Organization, the Ministry of Health in Lebanon, the University of Zurich, and Freie Universität Berlin (Burchert et al., 2019; Carswell et al., 2018). The Chinese version of Step-by-Step was culturally adapted and pilot tested in Macao with support from the WHO (Sit et al., 2020, Sit et al., 2022). The intervention is brief (5-sessions), delivered via mobile app, designed to address depression, but is also expected to be transdiagnostic (i.e., also addresses anxiety, PTSD, other stress reactions and client-defined psychosocial problems), and covers general wellbeing. It is delivered through digital devices (e.g., smartphone) with illustrated narratives, and is based on behavioral activation with psychoeducation, stress management skills (e.g., breathing technique), identifying personal strengths, positive self-talk, enhancing social support, and relapse prevention (Carswell et al., 2018). Each session contains 2–3 parts, between which participants can decide whether they continue to the next part immediately or do it later. Before allocation, participants will start the program with an onboarding session, which welcomes the participants, explains the purpose of the study, obtains informed consent, and screens for eligibility.

Eligible participants randomized to Step-by-Step will enter an introductory session to learn about the intervention, including format, pace, purpose, main techniques to be taught, and the function of the application. After completion of each session, the next session will be available in 4 days, which allows the participants to practice the technique they have learned from the program between the sessions. Participants are recommended to practice the intervention in a quiet environment and finish one session per week.

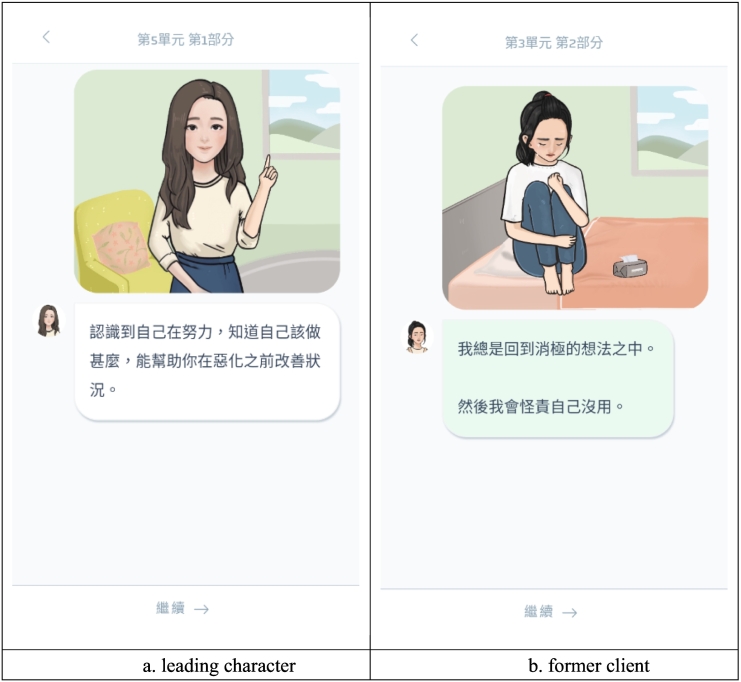

Step-by-Step contains fictional narratives that a senior leading character (Fig. 1a) introduces their former client (Fig. 1b) who sought help and completed the intervention with them. The senior leading character in the original Step-by-Step was designed to be a professional healthcare provider to teach the techniques throughout the intervention, and the former client is a character who represents the target participant's identify and problems (Carswell et al., 2018). The ‘former client’ shared their stories about their problems and how they applied the techniques to deal with the stressors. In the Chinese version of SbS, we replaced the senior leading character with a female senior student and a cartoon figure for the female version and male version, respectively, based on a consultative cultural adaptation process (Sit et al., 2020). The scenarios they shared have also been culturally adapted for the target population in the Chinese context, which was reported elsewhere (Sit et al., 2020). The scenarios will be displayed with text and illustrations. Each session lasts about 30 min.

Fig. 1.

Screenshots of adapted leading character, former character, and the display of illustrated narrative.

2.2.2.2. E-helpers

Each participant in the SbS group will be assigned to an e-helper, who is trained to provide minimal support to the participants on a weekly basis. Each helper will be responsible for 4–5 participants. The e-helper will receive training on the context and function of Step-by-Step, clinical training (e.g., Mental Health First Aid), as well as app and support training to gain competence to deal with questions raised by the participants and handle crisis should they arise, through asynchronous text messaging support provided within the application. All e-helpers will participate in written and a role-play assessment before they deliver the support. Minimal guidance will be provided through an initial 10–15 minute onboarding phone call and text messages. E-helpers will also receive weekly supervision to ensure the service quality and fidelity, and receive reflection sessions during the intervention to enhance their competence in providing support to participants.

2.2.3. Enhanced care as usual group

The control group will receive enhanced care as usual delivered by the SbS mobile application, which includes text-only psychoeducation and referrals to mental health services through the application. Psychoeducation provides information about how negative experiences can affect mood while referrals will provide a list of primary health care centers and psychological service providers where the participants can seek professional help. Psychoeducation lasts approximately 10 min. Brief psychoeducation has also been effective at reducing symptoms of depression among young adults, so while ECAU is not expected to yield a large effect size, modest symptom improvement within this group would be expected (Arjadi et al., 2018).

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. Overview

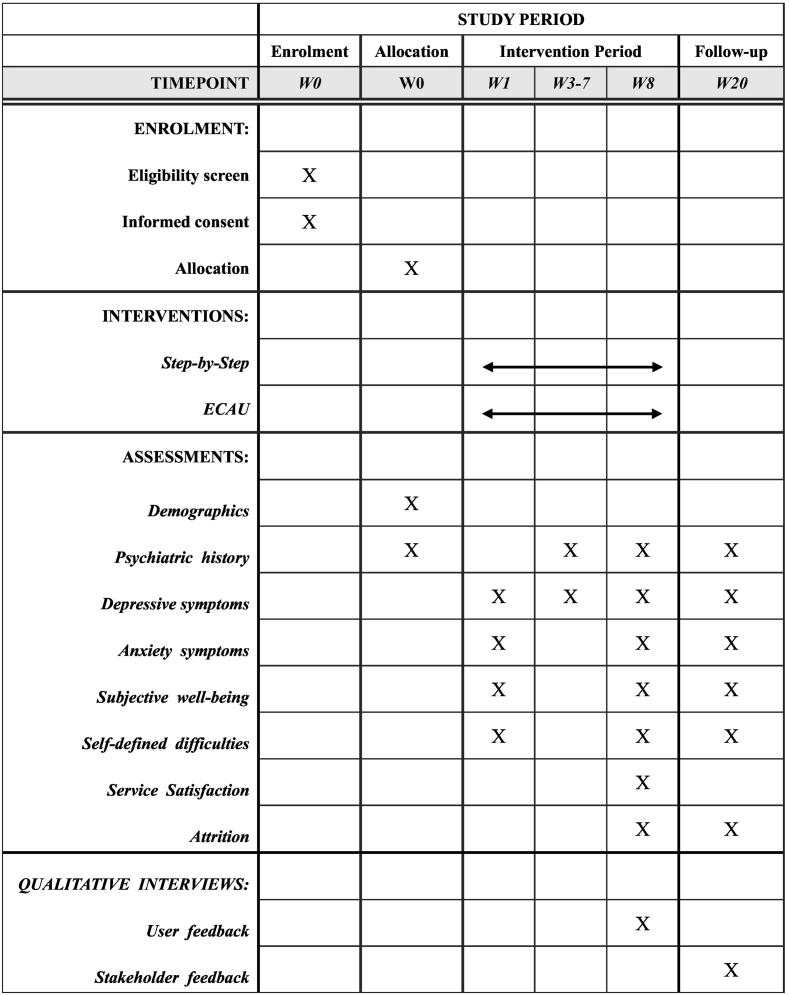

Overview of the study timeline is presented in Fig. 2. Sociodemographic information of the participants will be collected including sex, age, marital status, educational level, and number of years living in Macao. Medical history (e.g., mental health service utilization, psychiatric diagnosis, psychiatric medication, psychosocial treatment) in the past three months will be collected at pre-treatment and in the past eight weeks at post-treatment. The Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9), the Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7), the WHO-5 Wellbeing Index (WHO-5), the Psychological Outcome Profile instrument (PSYCHOLOPS) will be conducted at pre-intervention (week 0), post-intervention (week 8), and again at three-month follow-up (week 20). PHQ-9 will be additionally assessed weekly throughout the intervention (i.e., 8 weeks) to monitor depressive symptoms and suicidal ideation. The Client Satisfaction Questionnaire adapted for internet-based interventions (CSQ-I) will only be asked at post-intervention. The qualitative data will also be collected by individual semi-structured interview/focus group discussion at post-intervention.

Fig. 2.

Overview of study.

2.3.2. Primary outcomes

2.3.2.1. Depressive symptoms

The PHQ-9 is a nine-item self-report scale used to assess symptoms of depression in the past two weeks, which is based on the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorder-5 criteria for major depression (Kroenke et al., 2001). The Chinese version will be used in our study. Severity of symptoms will be assessed with a four-point scale, ranging from 0 to 3 (0 = not at all, 1 = on several days, 2 = on more than half of the days, 3 = nearly every day), with higher scores indicating higher depressive symptoms (0–27). A cut-off score to detect the clinical presence of depression is inconsistent across different populations (Kroenke et al., 2001; Wang et al., 2014; Yeung et al., 2008). We adopt a score of 10 or above to indicate depression in the sample, which is consistent with previous population-based studies among the Chinese population (Hall et al., 2017; Lau et al., 2016). The PHQ-9 demonstrated excellent reliability (α > 0.80) (Hall et al., 2017; Lau et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2014) and validity (Wang et al., 2014) in the Chinese population.

2.3.3. Second measures

2.3.3.1. Anxiety symptoms

The GAD-7 is a seven-item self-reported scale that used to assess symptoms of generalized anxiety disorder in the past two weeks (Spitzer et al., 2006). Severity will be assessed through a four-point scale, ranging from 0 to 3 (0 = not at all, 1 = on several days, 2 = on more than half of the days, 3 = nearly every day), with higher scores indicating higher anxiety symptoms (0–21). We adopt a score of 10 or above to indicate generalize anxiety in the sample, which is consistent with previous studies with Chinese population (He et al., 2010; Tong et al., 2016). Previous study within Chinese population showed excellent reliability (α > 0.80) (He et al., 2010; Tong et al., 2016) and validity (He et al., 2010).

2.3.3.2. Subjective well-being

The WHO-5 is a five-item self-report instruction that is used to assess with subjective well-being in the last two weeks (Bech et al., 2003). Each item is rated on a 6-point scale ranging from 0 to 5 (0 = at no time, 1 = some of the time, 2 = less than half of the time, 3 = more than half of the time, 4 = most of the time, 5 = all the time). Higher scores on WHO-5 indicate a higher level of subjective well-being (0–25). A Chinese version of the WHO-5 will be used in the current study. Previous study in Chinese population showed excellent reliability (α = 0.89) and validity (Volinn et al., 2010).

2.3.3.3. Self-defined psychosocial goals

The PSYCHLOPS (Ashworth et al., 2004) contains four questions which cover three domains: problem (two questions), function (one question), and well-being (1 question). Participants are required to provide a response to open-ended questions in problem and function domain. Responses will be assessed on a 6-point scale with a total score ranging from 0 to 20. The pre-therapy version and post-therapy version of PSYCHLOPS consists of the same 4 questions and the later one adds two questions about problems occurs during therapy (0 = not at all affected, 5 = severely affected) and overall evaluation of the participant (0 = much better, 5 = much worse). The Chinese version of PSYCHLOPS was translated from the original English version by a Chinese-English bilingual research assistant, and a backward translation was done by another Chinese-English research assistant to ensure the items are cultural and conceptual equivalent.

2.3.3.4. Treatment satisfaction

The CSQ-I (Boß et al., 2016), adapted from original CSQ (Larsen et al., 1979), is an 8-item self-administered scale used to assess client satisfaction with internet-based health interventions. Each item will be assessed with a different four-point scale corresponding with the item on 1 indicating least satisfaction/agreement while 4 indicating most satisfaction/agreement, with a total score ranging from 8 to 32. Higher scores indicate greater satisfaction with the intervention they received. A Chinese version of CSQ-I was translated from the English version by a Chinese-English bilingual research assistant, and a backward translation was done by another Chinese-English research assistant to ensure cultural and conceptual equivalence.

2.3.3.5. Dropout and adherence

A record of dropout, reason of dropout, and number of completed sessions and activities will be kept throughout the study. Reasons of dropout will be obtained from the weekly basis contact with the participant by an e-helper.

2.3.4. Qualitative data

The RE-AIM framework will be used to design questions for the evaluation of the following dimensions of intervention implementation by individual semi-structured interview/focus group discussion: Reach (e.g., how did you hear about this program? [participants]), Effectiveness (e.g., what are some of the ways Step-by-Step has had a positive impact in your life? [participants]), Adoption (e.g., describe how well you felt equipped to deliver the support based on the training you received? [e-helper]), Implementation (e.g., what costs need to be considered in the future? [PCC]), and Maintenance (e.g., what difficulties did you encounter when using SbS? [participants]).

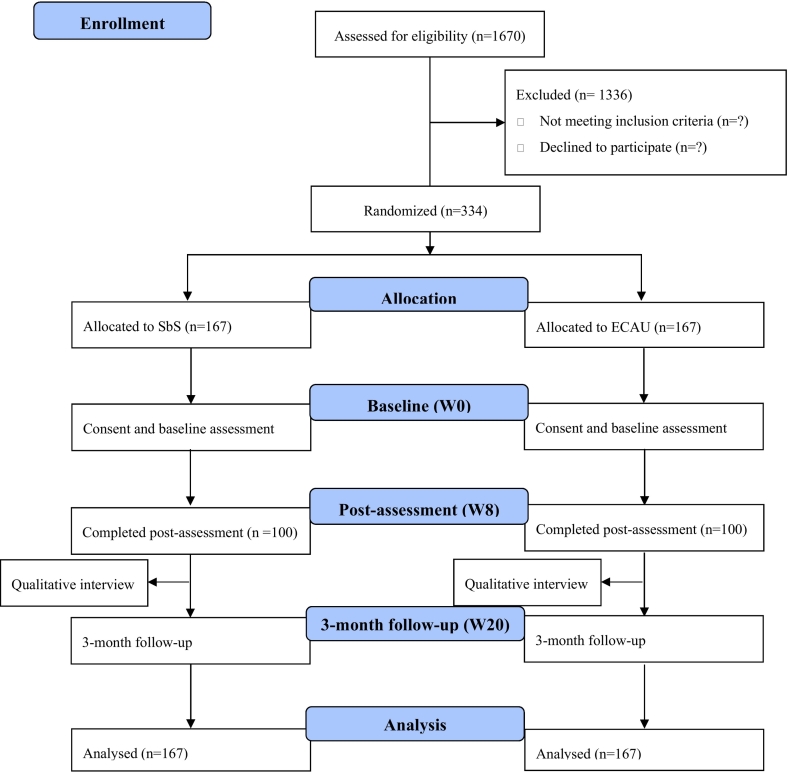

2.4. Sample size

Sample size is estimated based on the estimation of the primary outcome, depression symptoms measured with the PHQ-9 using G*Power 3.1 to detect a between-group change with an effect size Cohen's d = 0.4. A total sample size of 167 for each group will be required to achieve a power of 80 % at 5 % level of significance, with an attrition rate of 40 %. Thus, we expect a total eligible sample size of 334, with 167 allocated to each group. A CONSORT flowchart on enrollment, allocation and assessment of the participants was presented in Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Plan for recruitment, randomization, assessment based on CONSORT.

2.5. Randomization and blinding

Randomization will be carried out by a block randomization algorithm with random block lengths of 4, 6, or 8, and a 1:1 ratio within blocks within the app. Eligible participants will be randomly assigned with a 1:1 ratio to either Step-by-Step (SbS) or enhanced care as usual (ECAU). Due to the study design, blinding is not feasible.

2.6. Analysis

2.6.1. Statistical analysis

All main analyses will use an intention-to-treat (ITT) principle and units of the analysis are individuals. Chi-square analysis and t-test will be performed to compare baseline characteristics (e.g., sex, age, and educational level). We will evaluate the effectiveness of the intervention using the generalized linear mixed models (GLMMs). Based on the primary outcome, we will build a GLMM which includes intervention status (SbS vs. ECAU) and time (baseline, post-intervention) as fixed effects, and participant as random effects. Confounders will also be included as fixed effects in the model including gender, history of past treatment, and history of mental illness. The estimated intervention effect will be reported as the mean outcome difference and 95 % confidence interval (95%CI) between intervention and control arms. Subgroup analyses will be performed by establishing GLMMs based on participant's gender and depression symptom severity (mild, moderate, high). Sensitivity analyses will be conducted to assess the robustness of the missing data assumption and the impact of participants' compliance of intervention.

In addition, the GLMM will be used to evaluate the maintenance of intervention effect (baseline vs. 3-month follow-up). The GLMMs will also be used to assess intervention effects on secondary outcomes, where the mean outcome difference for continuous outcomes and odds ratios (ORs) for categorical outcomes between intervention and control arms will be reported.

Cohen's d for each intervention status and each outcome will be calculated between baseline and post-intervention/3-month follow-up to estimate the effect size.

2.6.2. Qualitative analysis

Content analysis will be applied to synthesize the findings from the RE-AIM framework. All interviews will be transcribed verbatim. A codebook will be developed by two coders working collaboratively on the same transcript, and each subsequent transcript will be independently coded. Transcripts will be compared and consensus reached through discussion of each transcript, and a third coder will be invited to resolve disagreements.

2.7. Monitoring

2.7.1. Data monitoring

The principal investigator (PI) of the study has access to anonymized primary data, which will be collected through the application. The data will be stored in an off-shore data server located in Germany and then exported as an analytic data file for the data analysis program. The data file for analysis will have cases without a personal identifier (e.g., name). Results will be reported and submitted to a peer-reviewed journal. A data monitor committee (DMC) will be set up for oversight of the trial procedure and reviews serious adverse events. The DMC will consist of clinical psychologists, supervisors of university counselling center and researchers, and will be responsible for adequate action for continuing trial conduct.

2.7.2. Harm

Harm is defined as a sustained deterioration of well-being directly caused by the intervention (Duggan et al., 2014). To our knowledge, this intervention poses minimal risk of harm to participants. Participants can stop the study at any time during the study. PHQ-9 will be used to monitor the participants' mood approximately weekly before each session starts, which will inform e-helpers about minimal support that can be offered. In addition, if any adverse event (AE), such as self-harm or symptom deterioration occurs, or a serious adverse event (SAE; e.g., acute suicidal attempt), the e-helper will report to the supervisor of the e-helper management team. A treatment referral will be made for participants who reported any SAE or life-threatening event (i.e., self-harm, suicidal attempt), and the participant will discontinue the study. Participants who report high depressive symptoms during the intervention (PHQ-9 scores > 20) will be provided referral resources including mental health hotlines, in-person consultation at PCC of the university, along with referrals to other local clinics and hospitals.

2.8. Ethics and dissemination

2.8.1. Research ethics approval

The study protocol will be reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Macau. The study will be registered with the Chinese Clinical Trial Registry (ChiCTR2100050214).

2.8.2. Confidentiality and consent

Data will be collected through the digital program and stored on a secure cloud server in the European Union. All data will be stored for 5 years. Details of privacy policy with contact for inquiries was included in the app where participants can read and reach out to the team via email contact if any concerns are raised. Informed consent will be obtained through the app. Participants will be informed that all data input in the app will be confidential. Participants will be reminded that they are free to refuse or withdraw anytime and that will not cause any consequences to them and their families. The proposed study will adherence the study protocol and ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

2.8.3. Post-trial care

After completion of the study, all participants will be reminded of the list of healthcare or psychological services providers inside the digital program and referrals will be made if necessary.

3. Results

The study received external funding from Bank of China (Macau Branch) as Title Sponsor and Rotary Club of Amizade Macau, Rotary of Macau, the Rotary Club of Penha Macao, and the World Health Organization, Western Pacific Regional Office. The enrolment will be rolling basis starting from September 2021. First results are expected to be submitted for publication in 2023.

4. Discussion

Step-by-Step is an innovative intervention to address common mental health problems in populations with sufficient digital literacy and is a promising program that can be embedded within a university system as a part of a stepped care model. Based on previous work done by Step-by-Step working teams in different regions/countries for different populations (Abi Ramia et al., 2018; Burchert et al., 2019; Garabiles et al., 2019; Harper Shehadeh et al., 2019; Heim et al., 2021; Liem et al., 2020a; Sit et al., 2020, Sit et al., 2022), Step-by-Step is a promising intervention that can reduce depressive and anxiety symptoms, improve functioning and well-being, while incorporating culture, among vulnerable populations who have barriers to mental health services (Shi et al., 2020). It is anticipated that after successful evaluation of the program and its implementation in the type 1 hybrid design RCT study, Step-by-Step can be widely adopted and sustainable in universities in Macao, and potentially extended to other parts of the Chinese community.

Declaration of competing interest

HFS declared no conflict of interest (and other authors).

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgement

We would like to thank Jan Gerwin, Tobias Wenz, and other members from Hybrid Heroes for the app development. We would like to thank staff from the Center for Macau Studies of the University of Macau who supported the project. We would like to thank staff from the Psychological Counselling Center of the University of Macau for giving the e-helper training. We would like to thank staff from Moon Chun Memorial College and Shiu Pong College of the University of Macau for recruiting e-helpers and research participants.

Funding sources

This work was supported by Bank of China (Macau Branch) as Title Sponsor, Rotary Club of Amizade Macau, Rotary of Macau, Rotary Club of Penha Macao, The Li Ka Shing Foundation, and the World Health Organization, Western Pacific Regional Office.

References

- Abi Ramia J., Harper Shehadeh M., Kheir W., Zoghbi E., Watts S., Heim E., El Chammay R. Community cognitive interviewing to inform local adaptations of an e-mental health intervention in Lebanon. Glob. Ment. Health. 2018;5 doi: 10.1017/gmh.2018.29. e39-e39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association . American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc; Arlington, VA, US: 2013. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. [Google Scholar]

- Arjadi R., Nauta M.H., Scholte W.F., Hollon S.D., Chowdhary N., Suryani A.O., Bockting C.L.H. Internet-based behavioural activation with lay counsellor support versus online minimal psychoeducation without support for treatment of depression: a randomised controlled trial in Indonesia. Lancet Psychiatry. 2018;5(9):707–716. doi: 10.1016/s2215-0366(18)30223-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashworth M., Shepherd M., Christey J., Matthews V., Wright K., Parmentier H., Godfrey E. A client-generated psychometric instrument: the development of ‘PSYCHLOPS’. Couns. Psychother. Res. 2004;4(2):27–31. doi: 10.1080/14733140412331383913. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer M.S., Kirchner J. Implementation science: what is it and why should I care? Psychiatry Res. 2020;283 doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2019.04.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bech P., Olsen L.R., Kjoller M., Rasmussen N.K. Measuring well-being rather than the absence of distress symptoms: a comparison of the SF-36 mental health subscale and the WHO-five well-being scale. Int. J. Methods Psychiatr. Res. 2003;12(2):85–91. doi: 10.1002/mpr.145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boß L., Lehr D., Reis D., Vis C., Riper H., Berking M., Ebert D.D. Reliability and validity of assessing user satisfaction with web-based health interventions. J. Med. Internet Res. 2016;18(8) doi: 10.2196/jmir.5952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burchert S., Alkneme M.S., Bird M., Carswell K., Cuijpers P., Hansen P., Knaevelsrud C. User-centered app adaptation of a low-intensity E-mental health intervention for Syrian refugees. Front Psychiatry. 2019;9 doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00663. 663-663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carswell K., Harper-Shehadeh M., Watts S., Van't Hof E., Abi Ramia J., Heim E., van Ommeren M. step-by-step: a new WHO digital mental health intervention for depression. Mhealth. 2018;4:34. doi: 10.21037/mhealth.2018.08.01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan A.-W., Tetzlaff J.M., Altman D.G., Laupacis A., Gøtzsche P.C., Krleža-Jerić K., Moher D. SPIRIT 2013 statement: defining standard protocol items for clinical trials. Ann. Intern. Med. 2013;158(3):200–207. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-158-3-201302050-00583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chowdhary N., Jotheeswaran A.T., Nadkarni A., Hollon S.D., King M., Jordans M.J., Patel V. The methods and outcomes of cultural adaptations of psychological treatments for depressive disorders: a systematic review. Psychol. Med. 2014;44(6):1131–1146. doi: 10.1017/s0033291713001785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conejero I., Olié E., Calati R., Ducasse D., Courtet P. Psychological pain, depression, and suicide: recent evidences and future directions. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2018;20(5):33. doi: 10.1007/s11920-018-0893-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuijpers P., Kleiboer A., Karyotaki E., Riper H. Internet and mobile interventions for depression: opportunities and challenges. Depress. Anxiety. 2017;34(7):596–602. doi: 10.1002/da.22641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curran G.M., Bauer M., Mittman B., Pyne J.M., Stetler C. Effectiveness-implementation hybrid designs: combining elements of clinical effectiveness and implementation research to enhance public health impact. Med. Care. 2012;50(3):217–226. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3182408812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson K.S., Bryant R.A., Harper M., Kuowei Tay A., Rahman A., Schafer A., van Ommeren M. Problem management plus (PM+): a WHO transdiagnostic psychological intervention for common mental health problems. World Psychiatry. 2015;14(3):354–357. doi: 10.1002/wps.20255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duggan C., Parry G., McMurran M., Davidson K., Dennis J. The recording of adverse events from psychological treatments in clinical trials: evidence from a review of NIHR-funded trials. Trials. 2014;15 doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-15-335. 335-335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao C., Sun Y., Zhang F., Zhou F., Dong C., Ke Z., Sun H. Prevalence and correlates of lifestyle behavior, anxiety and depression in Chinese college freshman: a cross-sectional survey. Int. J. Nurs. Sci. 2021;8(3):347–353. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnss.2021.05.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao L., Xie Y., Jia C., Wang W. Prevalence of depression among chinese university students: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci. Rep. 2020;10(1):15897. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-72998-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garabiles M.R., Harper Shehadeh M., Hall B.J. Cultural adaptation of a scalable World Health Organization E-mental health program for overseas Filipino workers. JMIR Form Res. 2019;3(1) doi: 10.2196/11600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glasgow R.E., Harden S.M., Gaglio B., Rabin B., Smith M., Porter G.C., Estabrooks P.A. RE-AIM planning and evaluation framework: adapting to new science and practice with a 20-year review. Front. Public Health. 2019;7 doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2019.00064. 64-64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glasgow R.E., Vogt T.M., Boles S.M. Evaluating the public health impact of health promotion interventions: the RE-AIM framework. Am. J. Public Health. 1999;89(9):1322–1327. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.89.9.1322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorman J.M. Comorbid depression and anxiety spectrum disorders. Depress. Anxiety. 1996;4(4):160–168. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1520-6394(1996)4:4<160::AID-DA2>3.0.CO;2-J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall B.J., Lam A.I.F., Wu T.L., Hou W.K., Latkin C., Galea S. The epidemiology of current depression in Macau, China: towards a plan for mental health action. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2017;52(10):1227–1235. doi: 10.1007/s00127-017-1415-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harper Shehadeh M., Heim E., Chowdhary N., Maercker A., Albanese E. Cultural adaptation of minimally guided interventions for common mental disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JMIR Ment. Health. 2016;3(3) doi: 10.2196/mental.5776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harper Shehadeh M.J., Abi Ramia J., Cuijpers P., El Chammay R., Heim E., Kheir W., Carswell K. step-by-step, an E-mental health intervention for depression: a mixed methods pilot study from Lebanon. Front Psychiatry. 2019;10:986. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrer M., Adam S.H., Fleischmann R.J., Baumeister H., Auerbach R., Bruffaerts R., Ebert D.D. Effectiveness of an internet- and app-based intervention for college students with elevated stress: randomized controlled trial. J. Med. Internet Res. 2018;20(4) doi: 10.2196/jmir.9293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He X., Li C., Qian J., Cui H., Wu W. Reliability and validity of a generalized anxiety disorder scale in general hospital outpatients. Shanghai Arch. Psychiatry. 2010;22(4):200–203. [Google Scholar]

- Heim E., Ramia J.A., Hana R.A., Burchert S., Carswell K., Cornelisz I., Van't Hof E. Step-by-step: feasibility randomised controlled trial of a mobile-based intervention for depression among populations affected by adversity in Lebanon. Internet Interv. 2021;24 doi: 10.1016/j.invent.2021.100380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holtrop J.S., Rabin B.A., Glasgow R.E. Qualitative approaches to use of the RE-AIM framework: rationale and methods. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2018;18(1):177. doi: 10.1186/s12913-018-2938-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunt G.E., Malhi G.S., Lai H.M.X., Cleary M. Prevalence of comorbid substance use in major depressive disorder in community and clinical settings, 1990–2019: systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 2020;266:288–304. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.01.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolovos S., Kleiboer A., Cuijpers P. Effect of psychotherapy for depression on quality of life: meta-analysis. Br. J. Psychiatry. 2016;209(6):460–468. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.115.175059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke K., Spitzer R.L., Williams J.B. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2001;16(9):606–613. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landes S.J., McBain S.A., Curran G.M. An introduction to effectiveness-implementation hybrid designs. Psychiatry Res. 2019;280 doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2019.112513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsen D.L., Attkisson C.C., Hargreaves W.A., Nguyen T.D. Assessment of client/patient satisfaction: development of a general scale. Eval. Program Plann. 1979;2(3):197–207. doi: 10.1016/0149-7189(79)90094-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lattie E.G., Adkins E.C., Winquist N., Stiles-Shields C., Wafford Q.E., Graham A.K. Digital mental health interventions for depression, anxiety, and enhancement of psychological well-being among college students: systematic review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2019;21(7) doi: 10.2196/12869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau K.M., Hou W.K., Hall B.J., Canetti D., Ng S.M., Lam A.I.F., Hobfoll S.E. Social media and mental health in democracy movement in Hong Kong: a population-based study. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016;64:656–662. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2016.07.028. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li L., Lok G.K.I., Mei S.L., Cui X.L., An F.R., Li L., Xiang Y.T. Prevalence of depression and its relationship with quality of life among university students in Macau, Hong Kong and mainland China. Sci. Rep. 2020;10(1):15798. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-72458-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liem A., Garabiles M.R., Pakingan K.A., Chen W., Lam A.I.F., Burchert S., Hall B.J. A digital mental health intervention to reduce depressive symptoms among overseas Filipino workers: protocol for a pilot hybrid type 1 effectiveness-implementation randomized controlled trial. Implement Sci. Commun. 2020;1:96. doi: 10.1186/s43058-020-00072-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liem A., Natari R.B., Jimmy, Hall B.J. Digital health applications in mental health care for immigrants and refugees: a rapid review. Telemed. J. e-Health. 2020 doi: 10.1089/tmj.2020.0012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linardon J., Cuijpers P., Carlbring P., Messer M., Fuller-Tyszkiewicz M. The efficacy of app-supported smartphone interventions for mental health problems: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. World Psychiatry. 2019;18(3):325–336. doi: 10.1002/wps.20673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ly K.H., Truschel A., Jarl L., Magnusson S., Windahl T., Johansson R., Andersson G. Behavioural activation versus mindfulness-based guided self-help treatment administered through a smartphone application: a randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open. 2014;4(1) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-003440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mao Y., Zhang N., Liu J., Zhu B., He R., Wang X. A systematic review of depression and anxiety in medical students in China. BMC Med. Educ. 2019;19(1):327. doi: 10.1186/s12909-019-1744-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sartorius N. Depression and diabetes. Dialogues Clin. Neurosci. 2018;20(1):47–52. doi: 10.31887/DCNS.2018.20.1/nsartorius. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi W., Shen Z.Z., Wang S.Y., Hall B.J. Barriers to professional mental health help-seeking among Chinese adults: A systematic review. Frontiers in Psychiatry. 2020;11:442 doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sit H.F., Hong I.W., Burchert S., Sou E.K.L., Wong M., Chen W., Lam A.I.F., Hall B.J. A feasibility study of the WHO digital mental health intervention Step-by-Step to address depression among Chinese young adults. Frontiers in psychiatry. 2022;12:812667. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.812667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sit H.F., Ling R., Lam A.I.F., Chen W., Latkin C.A., Hall B.J. The cultural adaptation of step-by-step: an intervention to address depression among Chinese young adults. Front Psychiatry. 2020;11:650. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer R.L., Kroenke K., Williams J.B., Lowe B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch. Intern. Med. 2006;166(10):1092–1097. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong X., An D., McGonigal A., Park S.P., Zhou D. Validation of the generalized anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7) among chinese people with epilepsy. Epilepsy Res. 2016;120:31–36. doi: 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2015.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volinn E., Yang B., He J., Sheng X., Ying J., Volinn W., Zuo Y. West China hospital set of measures in chinese to evaluate back pain treatment. Pain Med. 2010;11(5):637–647. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2010.00846.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W., Bian Q., Zhao Y., Li X., Wang W., Du J., Zhao M. Reliability and validity of the chinese version of the patient health questionnaire (PHQ-9) in the general population. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry. 2014;36(5):539–544. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2014.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z.-H., Yang H.-L., Yang Y.-Q., Liu D., Li Z.-H., Zhang X.-R., Mao C. Prevalence of anxiety and depression symptom, and the demands for psychological knowledge and interventions in college students during COVID-19 epidemic: a large cross-sectional study. J. Affect. Disord. 2020;275:188–193. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.06.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisel K.K., Fuhrmann L.M., Berking M., Baumeister H., Cuijpers P., Ebert D.D. Standalone smartphone apps for mental health-a systematic review and meta-analysis. NPJ Digit. Med. 2019;2:118. doi: 10.1038/s41746-019-0188-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization . World Health Organization; Geneva: 2016. Monitoring and Evaluating Digital Health Interventions: A PracticalGuide to Conducting Research and Assessment. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization . 2017. Depression and Other Common Mental Disorders: Global Health Estimates. Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Yeung A., Fung F., Yu S.C., Vorono S., Ly M., Wu S., Fava M. Validation of the patient health Questionnaire-9 for depression screening among chinese americans. Compr. Psychiatry. 2008;49(2):211–217. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2006.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]