Abstract

Deciphering the functional interactions of cells in tissues remains a major challenge. We describe DIALOGUE, a method to systematically uncover multicellular programs (MCPs) — combinations of coordinated cellular programs in different cell types that form higher-order functional units at the tissue level — from either spatial data or single-cell data obtained without spatial information. Tested on spatial datasets from the mouse hypothalamus, cerebellum, visual cortex, and neocortex, DIALOGUE identified MCPs associated with animal behavior and recovered spatial properties when tested on unseen data, while outperforming other methods and metrics. In spatial data from human lung cancer, DIALOGUE identified MCPs marking immune activation and tissue remodeling. Applied to scRNA-seq data across individuals or regions, DIALOGUE uncovered MCPs in Alzheimer’s disease, ulcerative colitis, and treatment with cancer immunotherapy. These programs were predictive of disease outcome and predisposition in independent cohorts and included risk genes from genome-wide association studies (GWAS). DIALOGUE enables the analysis of multicellular regulation in health and disease.

Ed sum

Coordinated gene programs spanning multiple different cell types are identified in healthy and diseased tissues.

INTRODUCTION

The interplay between different cells in a tissue is crucial for maintaining homeostasis. While many diseases have been traditionally perceived as the result of the malfunction of a particular cell or cell type, mounting evidence1–5 and new therapeutic strategies3,6,7 have demonstrated the pivotal role of multicellular action in health and diseases, opening new opportunities for intervention, diagnosis, disease monitoring and prevention. In parallel, advances in single cell RNA-seq (scRNA-seq)8,9 and spatial transcriptomics10–12 now allow us to systematically explore molecular profiles at single cell resolution across cell types13, tissues14,15, and disease states16–18, in both isolated cells and intact tissues10–12. However, despite these advances, deciphering multicellular regulation remains a challenge, limiting our ability to move from a cell- to a tissue-centric perspective.

While many computational methods have been developed to analyze single cell data, the vast majority map and explore single cell states13,19–24, by recovering gene-gene co-variation structures within a cell (e.g., PAGDOA21, NMF implementations25 and extensions, including cNMF13, LIGER19,26). Methods developed to study cell-cell interactions are mostly focused on reconstructing the tissue’s spatial organization27–30, inferring putative physical cell-cell interactions based on known receptor-ligand pairs or known signaling pathways31–33, or highlighting recurring cell type compositions of cellular neighborhoods using spatial data34–36. While these methods revealed important properties of cell biology and tissue structure, we still lack methods to uncover coordinated multicellular processes.

Here, we approach this problem in a new way, by introducing the concept of multicellular programs (MCPs) and developing the first method to systematically uncover MCPs from single-cell or spatial genomics data. We define MCPs as the combinations of different expression programs in different cell types that are coordinated together in the tissue, thus forming a higher-order functional unit at the tissue-level, rather than only at the cell-level. To recover them, we develop DIALOGUE, a computational method for decoupling cell states through multicellular configuration identification, by using cross-cell-type associations across niches in one tissue or across samples from multiple individuals. We apply DIALOGUE to either spatial transcriptomic or scRNA-Seq data, where it uses, respectively, spatial or cross-sample variation to identify MCPs. Applied to MERFISH10, Slide-Seq11, and seqFISH37 (sequential fluorescence in situ hybridization), and spatially annotated scRNA-Seq data38 from the mouse hypothalamus, cerebellum, visual cortex, and neocortex, DIALOGUE successfully recovered spatial properties on unseen test data, outperformed other methods and metrices, and identified MCPs that mark animal behavior. Applied to a spatial dataset from human lung cancer39, DIALOGUE identified MCPs marking immune activation and tissue remodeling in the tumor boarders. Finally, applied to scRNA-seq data from patients DIALOGUE identified (1) an ulcerative colitis (UC) MCP that predicts clinical responses to therapy and includes GWAS UC risk genes; (2) an Alzheimer’s disease (AD) MCP that marks brain aging, and (3) an immunotherapy resistance MCP in melanoma. Taken together, our approach and method open a new way to study cellular crosstalk and link cellular and tissue biology.

RESULTS

DIALOGUE: Decoupling cell states through multicellular configuration identification

Cells within the same microenvironment are exposed to similar cues, which may activate coordinated responses in different cell types at two (non-mutually exclusive) levels (Fig. 1a). First, different cell types may simultaneously activate the same, cell-type-independent program40 (Fig. 1a). Second, different cell types may each activate a different, cell-type-specific program, but in a concerted fashion, either because they directly impact each other, or because they each respond distinctly to the same shared cue (Fig. 1a). Both cases should give rise to corresponding expression programs across different cell types – where the expression of one set of genes in a certain cell is associated with the expression of the same or another set of genes in nearby cells or cells from the same sample. DIALOGUE is designed to find such patterns from either spatial or single cell genomics data to uncover multicellular configurations and their associated cellular programs.

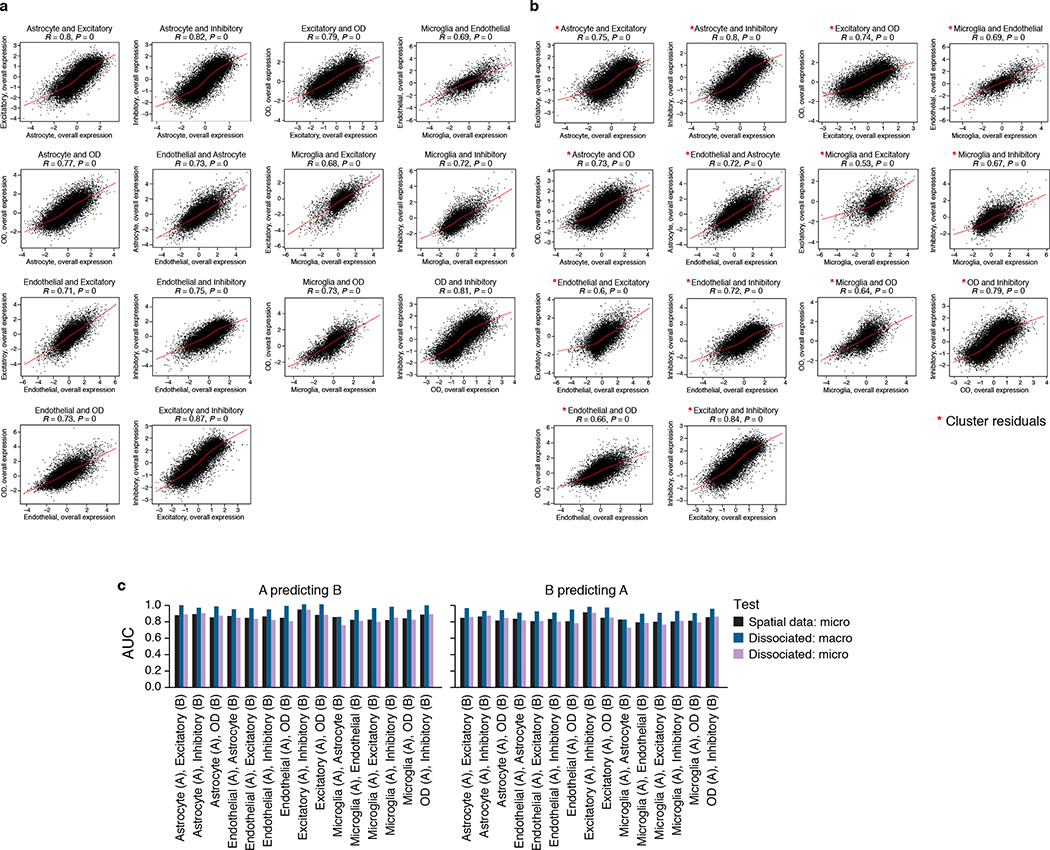

Figure 1. DIALOGUE: a method for MCP identification.

(a) Multicellular programs (MCPs). Upper panel: MCPs can arise due to either shared cues (upper row) or direct cell-cell interactions (bottom row) and comprise both cell type specific (left column) or shared (right column) programs. Lower panel: MCPs can be observed also in dissociated tissues based on co-variation across samples. (b) DIALOGUE method. In Step I (left), DIALOGUE takes as input (left) mean gene/feature expression (columns) matrices for each cell type, across samples or physical niches (rows) and infers “sparse latent variates” across those samples/niches (middle matrices) and their activity (right matrices) for each cell type, such that the programs of each cell type are highly correlated with the corresponding programs of all the other cell types (in this case shown only for two). In Step II (right), it identifies a gene signature for each sparse canonical variate, by interrogating single-cell distributions, while accounting for confounding factors at different levels. This results in MCPs, each with a set of up- and down-regulated genes in each of its cell type compartments (right). Ligand-receptor interactions can then be used to identify potential mediators. (c-d) Spatial distribution of MCPs. Expression (color code) of MCP2 and MCP4 components in single cells (dots) identified for excitatory and inhibitory neurons (c) and astrocytes and inhibitory neurons (d); “high”: expression above the 80th percentile; “moderate/low” otherwise. (e) Pearson correlation coefficient between genes, PCs, NMF, or DIALOGUE MCPs from either the training or the test set (x axis) across different pairs of cell types in spatial niches in the mouse hypothalamus (see Extended Data Fig. 1a for all other pairwise combinations). Middle line: median; box edges: 25th and 75th percentiles, whiskers: most extreme points that do not exceed ±IQR*1.5; further outliers are marked individually. (f) Receiver-Operator Curves (ROCs) for predictions of the expression of each MCP in unseen cells based on the expression profiles of their neighbors in the “micro-“ (radius of 37 μm, ~15 cells) or “macro-“ (radius of 220 μm, ~500 cells) environment, using spatial coordinates in the training data (black and purple) or only single-cell RNA profiles grouped to samples (red/blue, green/orange).

Given single-cell profiles from different spatial locations (in spatial profiling) or from different samples (e.g., in scRNA-Seq), DIALOGUE treats different types of cells from the same micro/macroenvironment or sample as different representations of the same entity (Fig. 1b). It first applies penalized matrix decomposition (PMD)41 to identify sparse canonical variates that transform the original feature space (e.g., genes, PCs, etc.) to a new feature space, where the different, cell-type-specific, representations are correlated across the different samples/environments. It then identifies the specific genes that comprise these latent features by fitting multilevel (hierarchical) models; this step models the single-cell distributions and controls for potential confounders, such as gender, age, variation in sample preparation, or technical variability (Fig. 1b, Online Methods). As output, DIALOGUE provides MCPs, each composed of two or more co-regulated, cell-type-associated programs (Fig. 1b, Online Methods).

DIALOGUE can identify multiple MCPs (input parameter k < rank of the original feature space). In practice, the different MCPs are not correlated with one another (Online Methods), and the cross-cell-type correlations observed within an MCP decreases with k, such that the first few MCPs depict most of the multicellular co-variation. DIALOGUE identified which cell types participate in each MCP in an unsupervised, data-driven manner. Given a set of cell types as input it will attempt to identify MCPs that include all cell types or a subset of them, retaining only the most statistically significant programs (empirical P-value < 0.05; Online Methods). To avoid overfitting, especially when applied to single cell data or when the number of samples is often relatively small, DIALOGUE applies permutation tests, cross validation procedures and, whenever available, testing on external (independent) datasets (Online Methods).

When applied to spatial genomics data, DIALOGUE supports different spatial scales, from focusing on direct neighbors to cells in a macroenvironment of a given (user-defined) length scale. DIALOGUE uses receptor-ligand interactions post hoc to propose cell-cell interactions that may mediate the identified MCPs by constructing a receptor-ligand network (RLN) that includes all the receptor-ligand pairs, where at least one of the genes appears in the MCP and is connected to a specific cell type. Because receptor-ligand pairs may not necessarily be spatially correlated at the RNA level, we do not require both the receptor and the ligand to be a member of the MCP, nor do we use receptor-ligand pairs to determine an MCP. Lastly, DIALOGUE can be initialized with a specific desired gene set, such as differentially expressed genes or genetic risk factors from relevant GWAS hits.

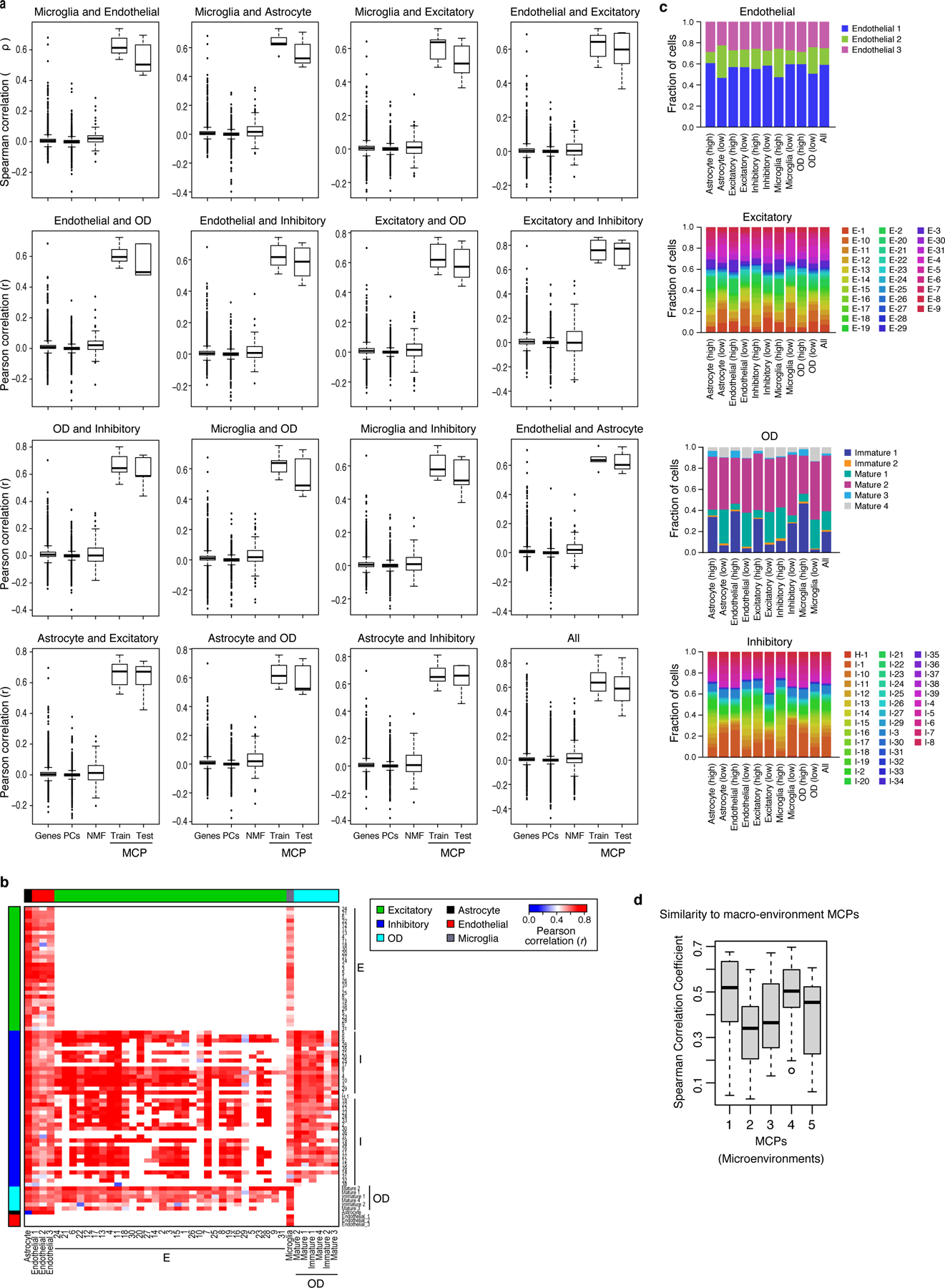

DIALOGUE captures spatial patterning in the mouse brain

We first applied DIALOGUE to MERFISH data, where the in situ expression of 155 genes was measured at the single-cell level in ~1.1 million cells from the mouse hypothalamic preoptic region10. We considered six broad cell types sufficiently represented in the data – microglia, endothelial cells, astrocytes, oligodendrocytes, excitatory and inhibitory neurons – and analyzed all pairwise combinations (Supplementary Table 1A).

DIALOGUE identified corresponding programs that were spatially correlated across different cell types (Fig. 1c–d; Extended Data Fig. 1). In contrast, single genes show only a moderate spatial correlation across different cell types (Fig. 1e, Extended Data Fig. 1a), and standard dimensionality reduction approaches, including principal component analysis (PCA) and Non-negative Matrix Factorization (NMF) did not reveal spatial patterns (Fig. 1e, Extended Data Fig. 1a).

The MCPs are distinct from programs identified using standard dimensionality reduction and clustering procedures10, and highlight spatial co-variation in specific cellular components as opposed to gross changes in tissue cell (sub)type composition (Extended Data Fig. 1b,c, 2a,b). The MCPs generalized, such that MCPs identified from a training set of MERFISH data collected from 9 animals, predict spatial patterns in an unseen test set of 9 other animals (Pearson’s r > 0.69, P < 1*10−30; AUROC: 0.79 – 0.9, 0.82 median, Fig. 1f, Extended Data Fig. 2c). For example, it successfully used the expression of excitatory neurons to predict the state of their neighboring astrocytes in the unseen data (Fig. 1f)

Next, we challenged DIALOGUE to recover such information without direct spatial coordinates, providing as input only samples that consisted of all the cells within a “patch” of a fixed radius (“macro-environments” with a radius of 220μm each, yielding on average 500 “in silico dissociated” cells per macroenvironment, Online Methods). We applied it to the MERFISH dataset as before to learn programs for all pairs of cell types. Despite no direct cell-cell spatial adjacencies for training, DIALOGUE was able to use a cell’s expression to predict the expression of the relevant MCP components in its unseen neighbors when tested on unseen data from 9 other animals (Fig. 1f). DIALOGUE performed well in this task both when predicting microenvironment features (direct neighbors in a radius of 37 μm, ~15 cells on average; AUROC: 0.73 – 0.91, median 0.82; P < 1*10−30, Mann-Whitney test) and macroenvironment features (radius of 220 μm, ~500 cells on average; AUROC: 0.83 – 0.98, median 0.94; P < 1*10−30, Mann-Whitney test, Fig. 1f, Extended Data Fig. 1d, 2c).

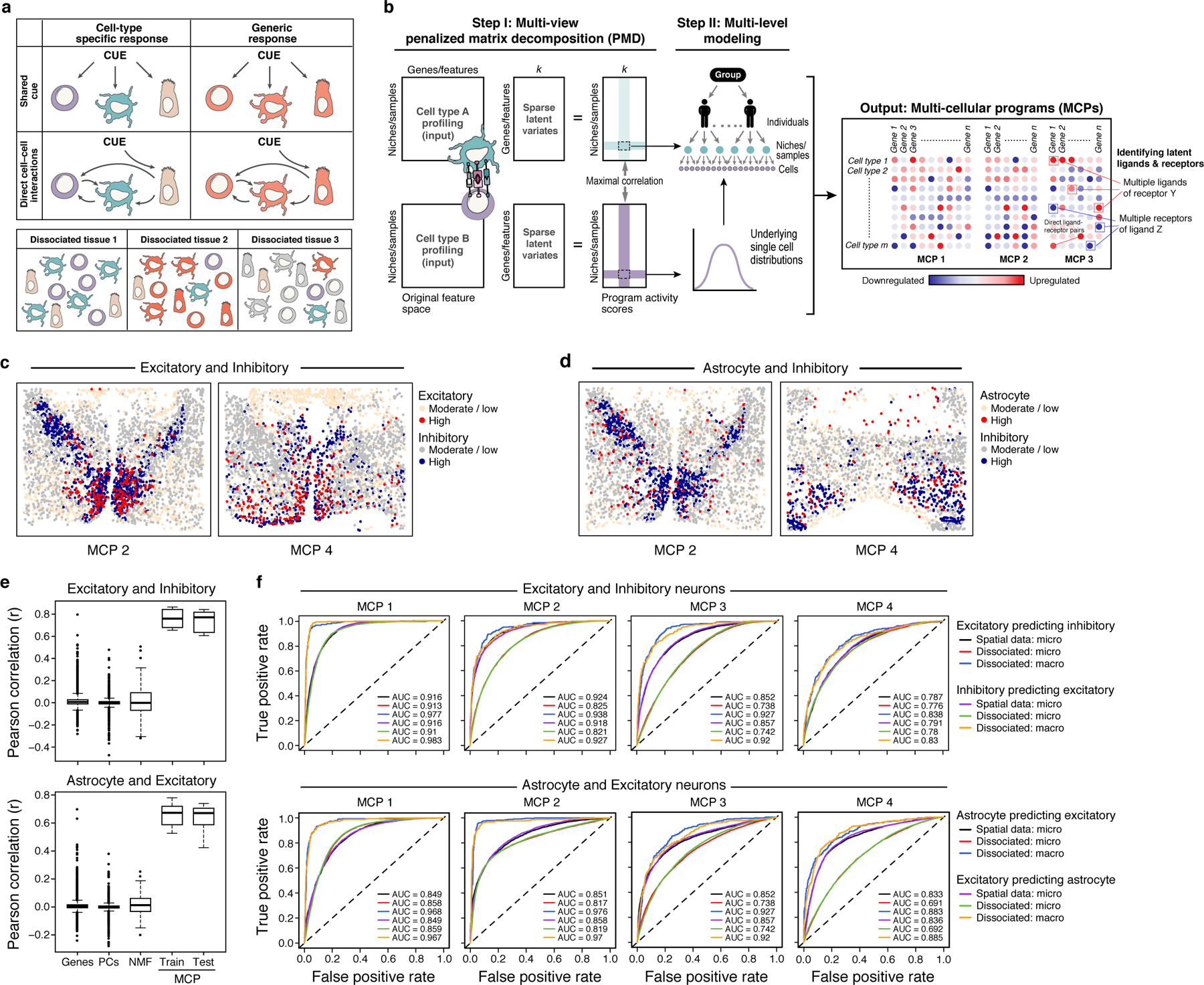

DIALOGUE outperforms existing methods

We next applied DIALOGUE to Slide-Seq11, seqFISH37, and spatially annotated scRNA-Seq data38, and compared its performance in recovering spatial properties on unseen test data, to that of other methods, including hidden-Markov random field (HMRF37; for extraction of spatial signatures), NMF, PCA, LIGER19,26, and differential gene expression analysis.

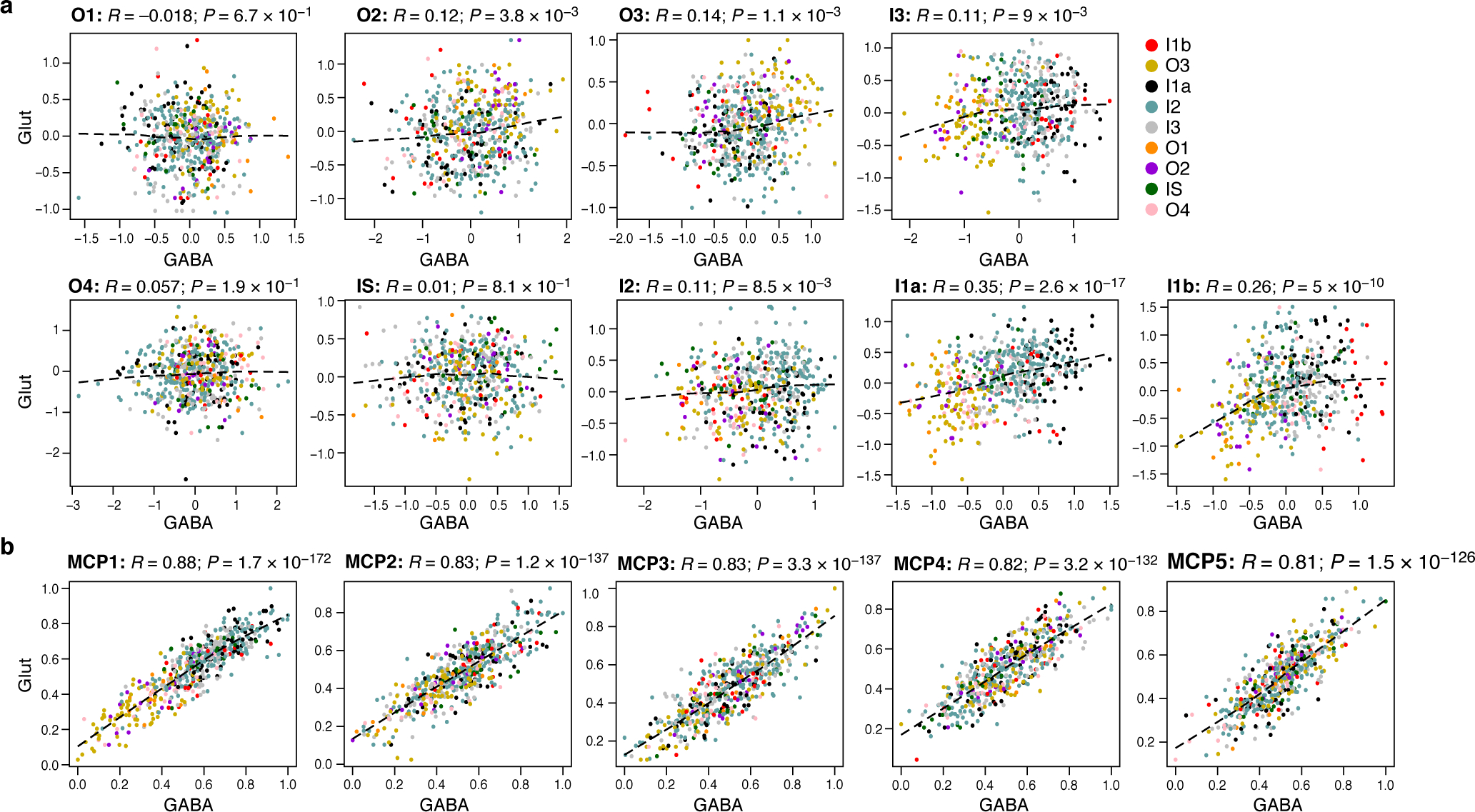

First, DIALOGUE outperformed HMRF37 in its ability to extract spatial signatures as demonstrated using the seq-FISH data37 from the mouse visual cortex, where HMRF was previously shown to identify spatial domains in the tissue along with cell-type specific signatures in each domain37. While HMRF signatures mark cells in specific domains, spatial signatures for different cell types did not co-vary across the tissue. For example, the GABAergic and glutamatergic programs in spatial domain O3 showed only modest correlation across the tissue when examining neighboring GABAergic and glutamatergic neurons (rs = 0.14, P = 1.13*10−3, Spearman correlation; Fig. 2a,b). We observed similar results in other cases, with low correlation between HMRF signatures (rs =−0.018 – 0.35, median 0.11; P < 0.05 in 6 out of 9 programs; Extended Data Fig. 3a), but strong spatial correlation across the different cell types in an MCP (R > 0.8, P < 1*10−100, Fig. 2a, Extended Data Fig. 3b), which captured different spatial patterns (Fig. 2b, Extended Data Fig. 4a) and did not overlap with the HMRF programs (P > 0.05 hypergeometric test).

Figure 2. DIALOGUE MCPs recover spatial information from different mouse brain regions and spatial genomics data types.

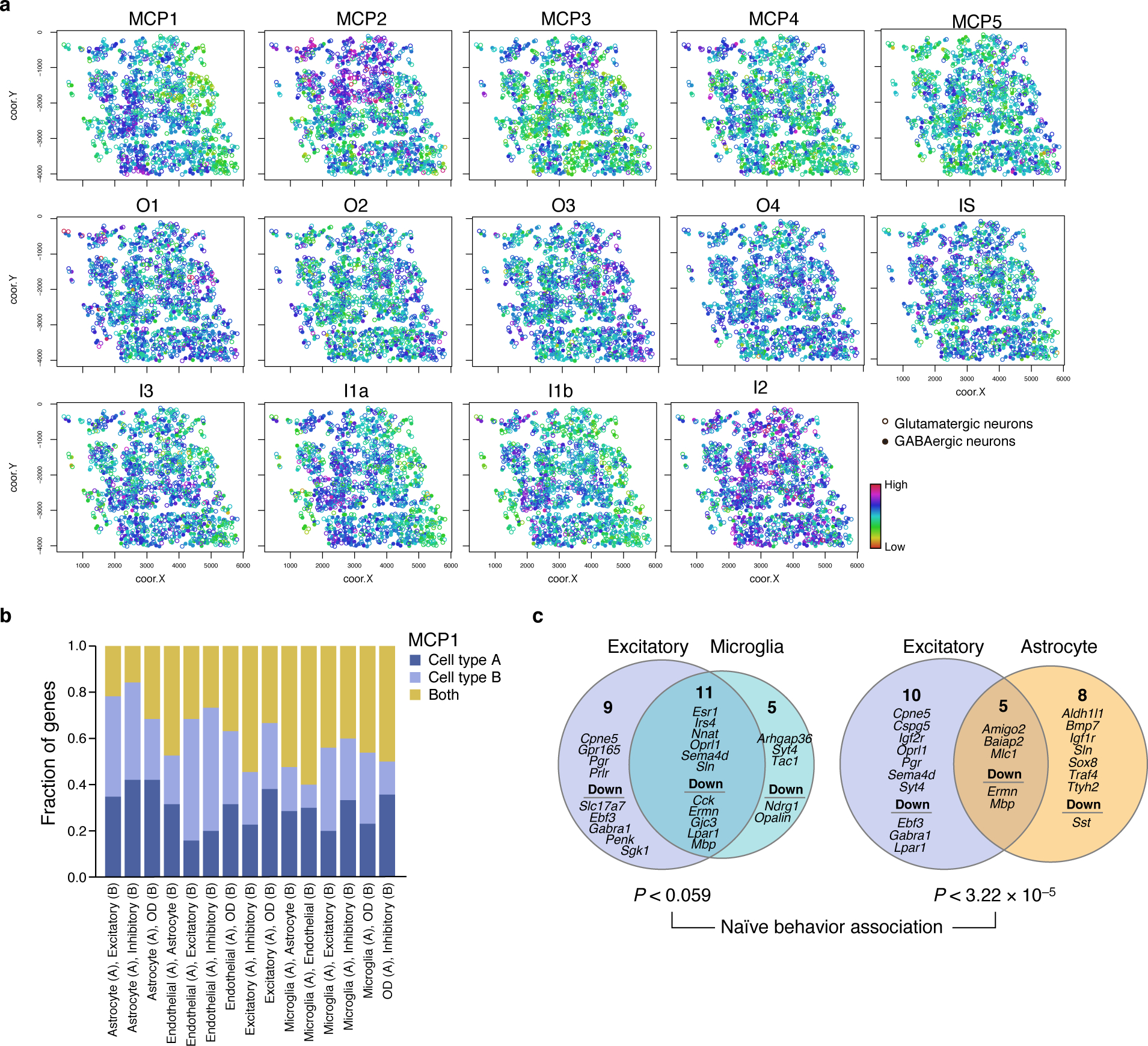

(a-b) DIALOGUE outperformed HMRF37 in extracting spatial signatures from Seq-FISH data37 from the mouse visual cortex. (a) Overall Expression of the HMRF37 O3 domain programs (left) and corresponding MCP1 components (right) in neighboring pairs of glutamatergic (y axis) and GABAergic (x axis) neurons from different regions (colors). Spearman correlation coefficient (R) and two-sided p-values (P) are shown. (b) HMRF-domain assignments (left) and Overall Expression of (middle) MCP1, and MCP2 (right) in glutamatergic (circles) and GABAergic (dots) neurons in their spatial context. (c-e) MCPs predict adjacent cells’s states on unseen test data. (c) Predictive accuracy (Area Under the Receiver Operator Curve, AUROC, y axis) for neighboring cells for different pairs of cell types (x axis), when using the Euclidean distance based on MCPs learned on training data (red), Principal Components from PCA (blue), or the original gene expression data (green). (d,e) True positive (y axis) and false positive (x axis) rates for predicting neighboring cells based on MCPs (red), PCs (blue) or gene expression (green) in mouse cerebellum Slide-Seq data11 (d) or scRNA-seq from spatially distinct regions in the mouse neocortex38 (e). AUROC values are shown in parentheses. (f) MCPs in the cerebellum distinguish coordinated expression between neurons and astrocytes in the inner and outer layers. Overall Expression (two left panels) in neurons and astrocytes and discretized expression (two right panels; (“high”: expression above the 80th percentile; “moderate/low” otherwise)) of MCPs identified in the mouse cerebellum based on Slide-Seq data. (g) Overall Expression (y axis, Online Methods) of the excitatory-inhibitory MCP in male (left) or female (right) mice exhibiting different behaviors (legend). Middle line: median; box edges: 25th and 75th percentiles, whiskers: most extreme points that do not exceed ±IQR*1.5; further outliers are marked individually. (h) The two cell programs in each of two MCP1s and their specific and shared (intersection) genes. P-values denote association with naïve animal behavior (multilevel mixed-effects models, two-sided test).

DIALOGUE also outperformed a recent method42, where spatial expression properties are used to train a neural network (NN) predictor of cell location from single cell expression. We used DIALOGUE and the single-cell data38 to identify MCPs on a training set, trained a multiclass support vector machines (SVM) to predict cell location based on the compact MCP representation (with 5 MCP features per cell), and tested the predictions on an unseen test set. DIALOGUE outperformed the NN-predictor, successfully classifying 89% of the glutamatergic neurons onto the correct region (i.e., VISp vs. ALM) and 60% to the correct region and layer, compared to 65% and 37% for the NN model, respectively. While the NN predictor could not accurately map GABAergic neurons at all, as previously reported42, DIALOGUE-SVM classification success rates in this case were 68% for region and 37% for layer.

We also compared DIALOGUE’s ability to recover spatial information with respect to the spatial “smoothness” of gene expression27. Using MERFISH data10 from mouse hypothalamus and Slide-Seq data of mouse cerebellum11, we found that the Euclidean distance at the MCP-space predicts which pairs of cells are adjacent to each other and which are not, when testing on unseen data, outperforming predictors using distance in the original expression space or based on the first PCs (MERFISH: mean AUROC = 0.70, 0.56, and 0.61; Fig. 2c; and Slide-Seq: AUROC = 0.68, 0.57, 0.52; Fig. 2d, for MCPs, PCs, and full expression data). Similarly, the MCP Euclidean distance also predicted whether they are from the same niche in scRNA-Seq data38 (AUROC of 0.76 and 0.62 for glutamatergic and GABAergic neurons, respectively; vs. AUROC of 0.58 and 0.53, respectively, for full expression data; Fig. 2e). In Slide-Seq data, DIALOGUE identified MCPs that depict spatial organization in the cerebellum (Fig. 2f), revealing coordinated expression of neuronal programs with either the outer (MCP1) or inner (MCP2) layer of adjacent astrocytes (Supplementary Table 1).

Lastly, we examined if consensus NMF (cNMF), where cell type identity programs and cellular activity programs are jointly identified, could identify MCPs when applied to scRNA-seq data from dozens of brain organoids43. No pair of cNMF programs showed significant correlation across samples when examining all possible pairwise combinations of cells and program (BH FDR > 0.05, Spearman correlation). In contrast, DIALOGUE identified strong MCPs on the same data43 (P < 1*10−7, Spearman rs > 0.89; P < 0.05, empirical test).

MCPs in the mouse hypothalamus mark animal behavior

Many of the programs DIALOGUE identified for pairs of cell types in the mouse hypothalamus were strongly associated with particular animal behaviors. This was observed mostly for the leading MCP (MCP1; P < 0.05 for 12 out of 15 first MCPs, mixed-effects, BH FDR44, Online Methods; Fig. 2g), which we focused on here (Fig. 2g,h; Extended Data Fig. 4b,c). Subsequent MCPs (MCP2-5) showed higher intra-animal variation, resulting from spatial co-variation within the tissue (Fig. 1c,d).

The MCPs (MCP1) that oligodendrocytes, excitatory and inhibitory neurons formed with other cell types were strongly repressed after parenting, aggression, or mating (BH FDR < 0.05, mixed-effects44, Fig. 2g, Extended Data Fig. 4c). All of these programs include Oprl1, encoding the nociceptin receptor, aligned with the key role of nociceptin in learning and emotional behaviors45, and show the involvement of hormonal signals (e.g., prolactin, estrogen, and progesterone receptors Prlr, Esr1, Pgr, respectively; Fig. 2h). These “hormonal” programs were equally active in female and male mice (P > 0.1, mixed-effects) and their neuronal and microglia components were strongly co-regulated even when considering only male or only female animals (r > 0.63, P < 1*10−30, Pearson correlation).

In contrast to the MCPs DIALOGUE identified, “MCP-independent” components did not show any significant association with animal behavior. Specifically, we regressed out the first five MCPs DIALOGUE identified from the gene expression profiles and computed the PCs of the residuals (Online Methods). None of these residual components were associated with animal behavior, indicating that a large fraction of the biologically meaningful cell-cell variation in this system is captured by the MCPs identified by DIALOGUE.

Inflammatory MCPs in lung cancer

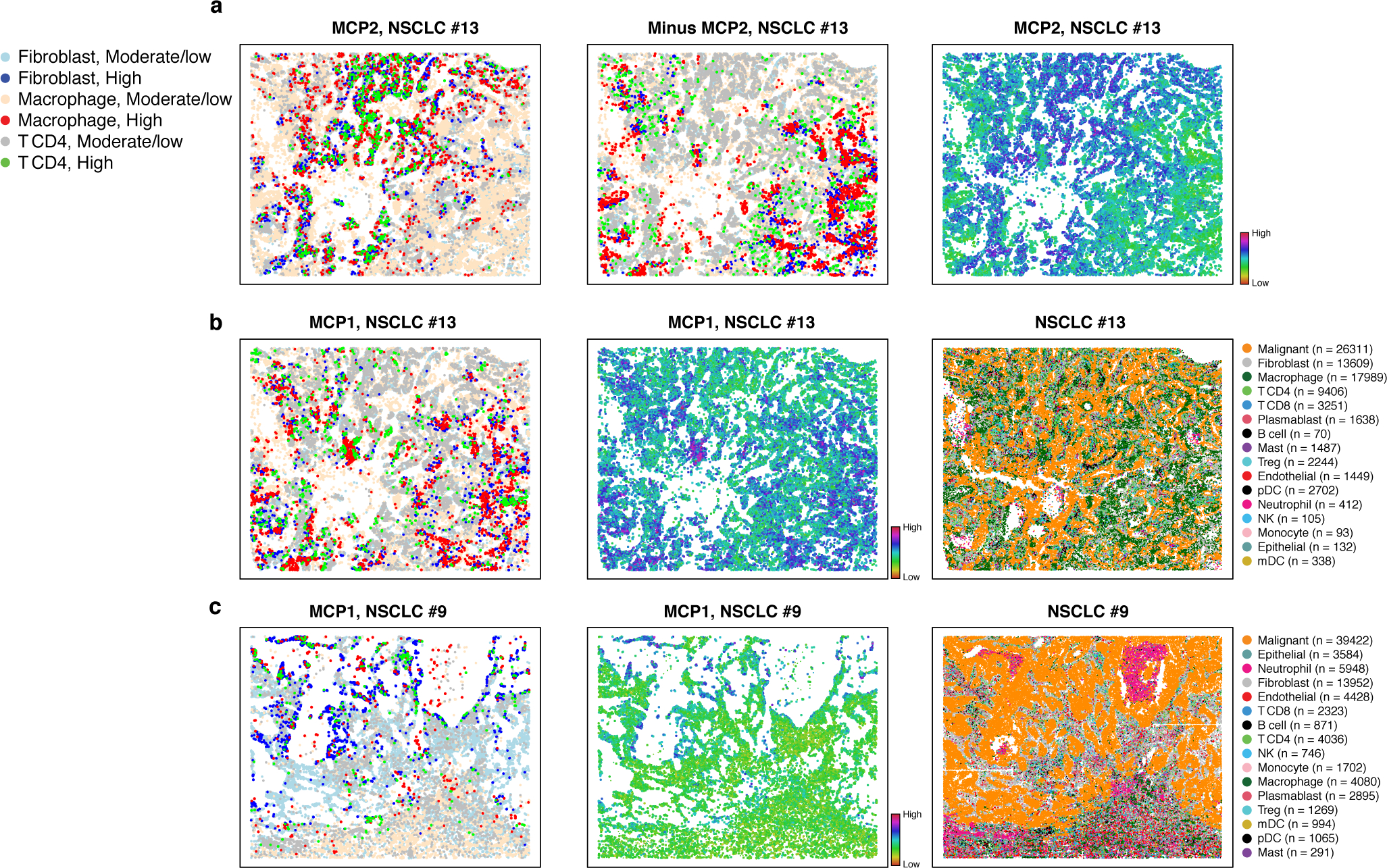

Examining DIALOGUE in non-canonical tissues, we applied it to Spatial Molecular Imager (SMI) data from 8 non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) human tumors, where 980 genes were profiled in situ across 800,000 single cells39. Focusing on CD4+ T cells, macrophages, and fibroblasts, DIALOGUE identified 3 MCPs in all 8 samples (Fig. 3, Supplementary Table 1).

Figure 3. MCPs in NSCLC identify coordinated interferon responses in immune and stroma cells at the tumor edge.

Cell type assignments and MCPs in representative NSCLC tumors profiled by SMI data. (a) MCP2 in NSCLC tumor #13. Discretized expression (left, “High” > 80th percentile; “moderate/low” otherwise), its inverse (middle, highlighting cells with low MCP expression), and Overall Expression (right) of MCP2 of cells (dots) in the tumor spatial context. (b) MCP1 in NSCLC tumor #13. Discretized expression (left) and Overall Expression (middle) of MCP1, and cell type annotations (right) of cells (dots) in the tumor spatial context. (c) MCP1 in in NSCLC tumor #9. Discretized (left) and Overall Expression (middle) of MCP1 and cell type annotations (right) of cells (dots) in the tumor spatial context.

MCP1 identified a cross T cell, macrophage and fibroblasts interferon response and antigen cross presentation program located at the interface with the tumor malignant boundary (Fig. 3). Among its top genes, IDO1 is up regulated in T cells. IDO1 is a suppressor of immunity and promoter of tolerance that catabolizes the amino acid tryptophan and other indole compounds46. The IDO1 locus contains IFN response elements and is induced by type I (IFN-I) and type II (IFN-II) interferons produced at sites of inflammation or by activated immune cells46. Consistently, IFN-I and II response genes are induced in MCP1 in all three cell types (e.g., CCL2, CXCL10, IFITM3, present in all three cell types, STAT1 in fibroblasts, IFIH1 in CD4 T cells, etc.), and antigen presentation genes are inducued in fibroblasts, whereas the immune checkpoint CTLA4 and complement and antigen cross-presentation genes are repressed in CD4 T cells and macrophages, respectively. VEGFA up-regulation in fibroblasts may indicate that MCP1 is also linked to stimulation of endothelial cell invasion and vessel formation. IL1 signaling may play a role in coordinating this multicellular program, given the coordinated induction of IL1B in macrophages, its receptor IL1R1 in fibroblasts and its agonist IL1RN in macrophages. Spatially, MCP1 marks certain boundaries of the tumor, where T cells, fibroblasts, and macrophages have direct contact with malignant cells (Fig. 3), suggesting that it might be activated by malignant-driven stimulation or tissue remodeling.

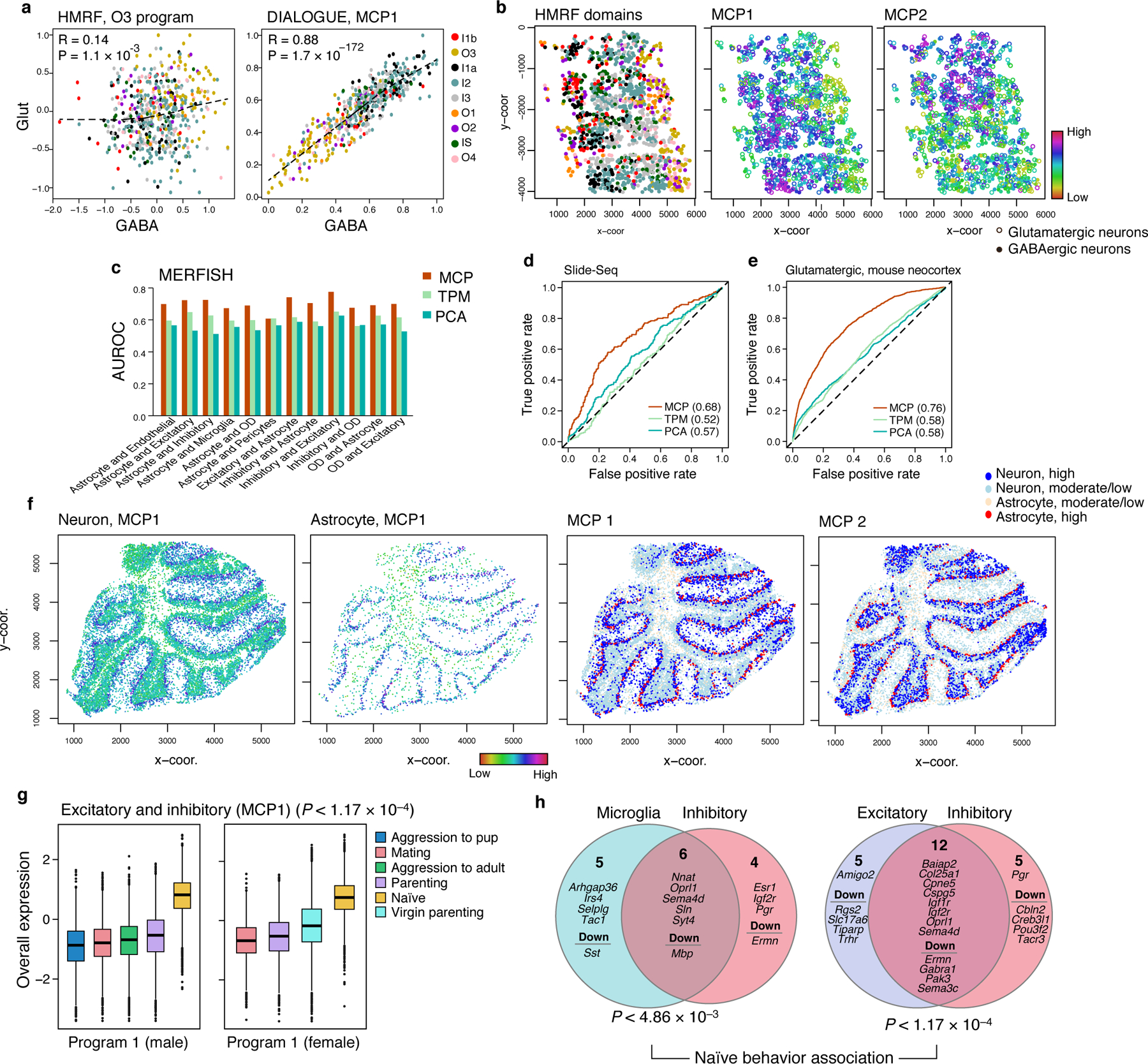

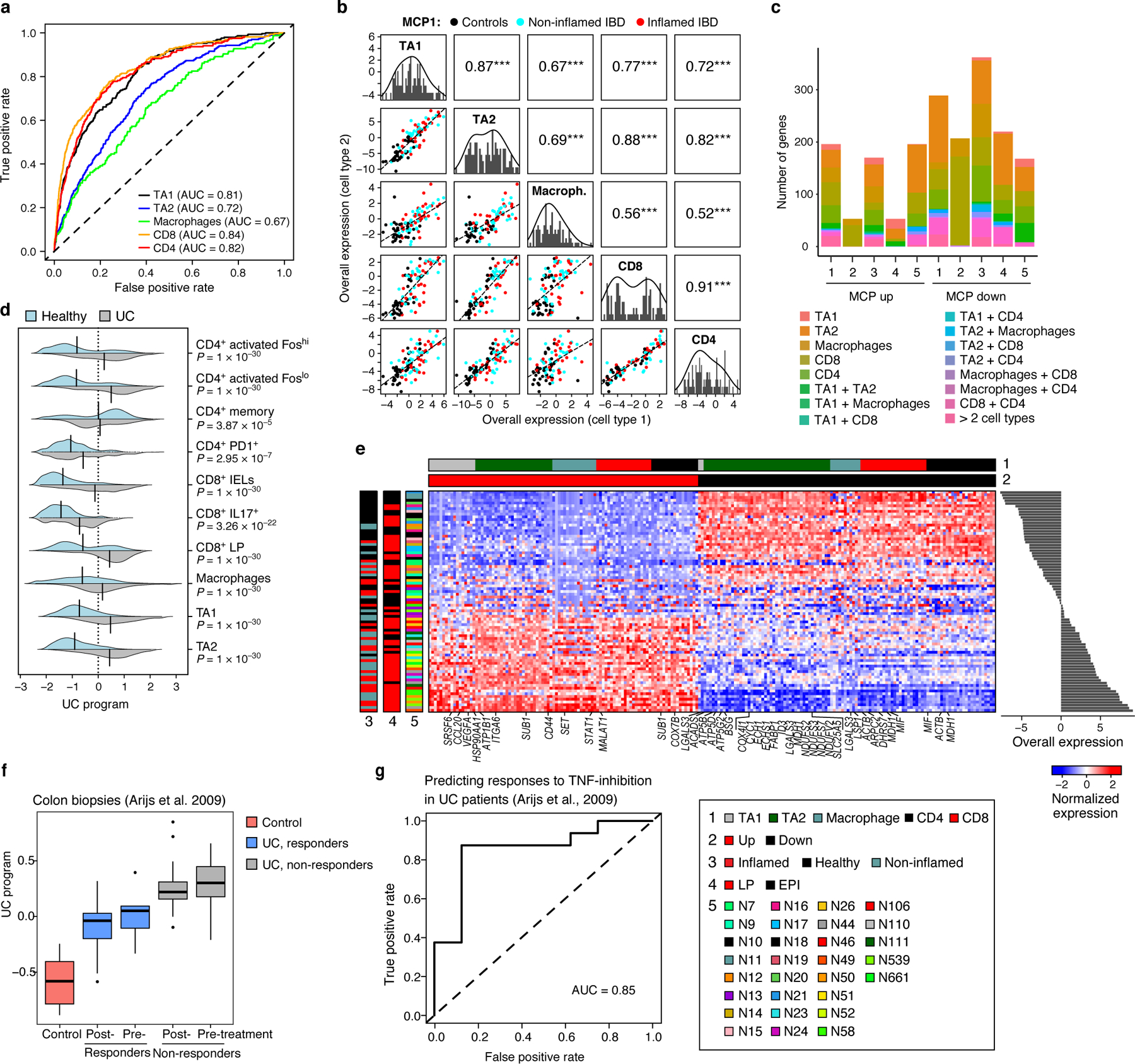

Ulcerative colitis MCPs recovered from patients scRNA-seq

Next, we applied DIALOGUE to scRNA-Seq data from dissociated tissue specimens, without cell-level spatial coordinates, treating each sample as one “niche”. The dataset16 consisted of 366,650 scRNA-Seq profiles from 68 colonoscopic biopsies (each ~2.4 mm2) from 12 healthy individuals and 18 UC patients. At least two biopsies were obtained from each individual, such that in UC patients, one samples is from inflamed or ulcerated tissue (“inflamed”) and one is from adjacent histologically non-inflamed tissue (“non-inflamed”). In addition, each sample was further separated to the epithelial (EPI) and lamina propria (LP) tissue fractions prior to cell dissociation and profiling, resulting in 115 spatially distinct samples across 30 individuals. We provided as input five well-represented cell subsets – macrophages, transit amplifying (TA) intestinal epithelial cells (TA1 and TA2), CD8+ T cells and CD4+ T cells. DIALOGUE identified five-way MCPs that span all five cell types (Supplementary Table 2, Online Methods).

We first tested if DIALOGUE identifies “intentionally mis-localized cells” based on the assumption that such cells will not fit the state predicted by their macroenvironment, as reflected by the MCPs. We trained DIALOGUE with an “in silico contaminated” dataset, where we added to each sample ~50 cells (10 per cell type; 0.02–0.06% of the cell type population) from an “adjacent sample” from the same individual. While these contaminating cells were always from the same patient, they were obtained from the same or different layer (LP/EPI) and from a sample that had the same or a different clinical status (both healthy, or inflamed and uninflamed). Based on the MCPs in the “contaminated training set”, DIALOGUE then computed an environment-score, which denotes for each cell to what extent its real state agrees with the one predicted by its neighbors (some of which may be contaminating; Online Methods).

DIALOGUE identified the mis-localized cells with high accuracy (Fig. 4a), as their environment-scores were significantly lower than those of the other cells (P < 1*10−10, t-test). We further evaluated this when considering different types of contamination and found that DIALOGUE was most accurate in spotting contamination from a different and distinct spatial location (i.e., LP vs. EPI) and most successful for CD8 and CD4 T cells, and least so for macrophages (Extended Data Fig. 5a). These findings demonstrate that DIALOGUE captures niche information, is robust to data contamination and could be potentially used to identify “infiltrators” to an established environment.

Figure 4. MCPs associated with ulcerative colitis and predictive of clinical outcomes.

(a) Deviation from multicellular patterns identifies mis-localized cells. ROC curves show the true positive (y axis) and false positive (x axis) rate when predicting mis-localized cells of each cell subset (color legend). (b) MCP1 in the human colon. Off diagonal panels: Comparison of Overall Expression scores (y and x axes) for each cell component of MCP1 (rows and columns, labels on diagonal) across the samples (dots, black: control, blue: non-inflamed IBD, red: inflamed IBD); the lines correspond to the linear fit. Pearson correlation (r) and significance (***P < 1*10−3, one-sided) are shown in the panels above the diagonal. Diagonal panels: Distribution of Overall Expression scores for each cell type component, along with the kernel density estimates. (c) Most genes in five colon MCPs are specific to one cell component. Number of genes (y axis) in the up (left bars) and down (right bars) of each of five colon MCPs (x axis) that appear only in one cell type component or in multiple ones (color legend). (d) MCP1 is induced in UC samples. Distribution of Overall Expression scores (x axis) of MCP1 (“UC program”) across the different cell subtypes (y axis) for cells from UC patients (grey) and healthy individuals (light blue); black line denotes the mean of the distribution. P: One-sided p-values, mixed-effects models. (e) UC multicellular program genes. Average expression (Z score, red/blue color bar) of top genes (columns) from the UC multicellular program, sorted by their pertaining cell type (top color bar), across samples (rows), sorted by Overall Expression (right, Online Methods), and labeled by clinical status, location and patient ID (left color bar). (f,g) UC multicellular program predicts response to anti-TNF therapy. (f) Overall Expression (y axis) of the UC-program in bulk RNA-seq of colon biopsies from 24 UC patients pre- and post-infliximab infusion, stratified to responders (blue) and non-responders (grey) and in normal mucosa from 6 control patients51 (red). Middle line: median; box edges: 25th and 75th percentiles, whiskers: most extreme points that do not exceed ±IQR*1.5; further outliers are marked individually. P-value: linear regression model (Online Methods). (g) ROC curve obtained when using the UC multicellular program score in pre-treatment samples51 to predict the subsequent clinical responses to infliximab infusion in UC patients.

Applying to the real (non-contaminated) data, DIALOGUE identified five MCPs, each with five cell type components. The different cell-type components of each MCP were strongly co-expressed across the samples (Fig. 4b; P < 1*10−3, mixed-effect model that accounts for gender, spatial compartment (EPI/LP), and cell subtypes, Online Methods), even when considering only samples from UC patients or from healthy individuals (P < 1*10−3, mixed-effects). Most MCP genes were assigned only to one cell type (55–74%), although some were shared between the components of two or more cell types (Fig. 4c, Supplementary Table 2), potentially representing the context-dependent and -independent impact that the environment has on different cells, respectively.

Ulcerative colitis MCP marks genetic risk loci and prognosis

MCP1 identified in the colonoscopic biopsies was substantially higher in UC samples compared to samples from healthy individuals (P < 1*10−7, mixed-effects; Fig. 4d,e). This was observed also when considering only the inflamed or non-inflamed UC samples (P < 1*10−10, mixed-effects), only specific cell types, as well as finer T cell subsets (Fig. 4d,e; Extended Data Fig. 5b). MCP1, which we termed the UC program, was enriched for genes located in genetic risk loci for IBD and UC16 (P = 4.15*10−4; Online Methods), particularly in its up-regulated set, including CCL2047 (TA1 and TA2), PRKCB (CD8 and macrophages), and IRF148 (macrophages and CD4). Most of the UC program genes, including 19 from risk loci (Supplementary Table 2), are cell-type specific in the program, although they are expressed in various cell types. Such information can be important when pursuing therapeutic hypotheses or combinatorial therapies.

The up-regulated components of the UC program showed hallmarks of a pro-inflammatory tissue microenvironment (Fig. 4e). The macrophage compartment was enriched for up-regulation of genes involved in positive regulation of immune response, leukocytes and lymphocytes activation in macrophages (P < 1*10−6, hypergeometric test); the CD4 and CD8 T cell compartments were enriched with up-regulation of chromatin organization and effector T cell genes, respectively (P < 1*10−7, hypergeometric test); and the TA1 and TA2 compartments were enriched for leukocyte migration (P = 5.76*10−6, e.g., CCL20, CD44) and VEGFR1 pathway genes (P = 4.66*10−6; e.g., CTNNB1 and VEGFA). The down-regulated components of the program were enriched for oxidative phosphorylation and fatty acid metabolism in TA1 and TA2 cells (P < 1*10−6, hypergeometric test), and exhaustion and T regulatory (Treg) marker genes in CD8 and CD4 T cells, respectively (P < 1*10−8, hypergeometric test).

Based on ligand-receptor binding, gene encoding 61 receptors have ligands expressed in the UC program, but are not members of the program itself, including ITGA4, a top UC risk gene49,50. As receptor activation cannot be gauged at the mRNA level, this analysis provides a new way to highlight candidate receptors that may mediate the expression cell states in the MCP.

The UC program was associated with UC status also in an independent bulk RNA-Seq dataset of colon tissue samples obtained from 24 UC patients before and 4–6 weeks after their first treatment with a TNF-inhibitor (infliximab infusion) and of 6 control patients51. The program was substantially higher in the UC patients compared to controls (P < 1*10−4, linear regression; AUROC = 0.95; Fig. 4f), lower in responders compared to non-responders (P < 1*10−5, linear regression) and predictive of responses (AUROC = 0.85, when considering only the pre-treatment samples, Fig. 4g). Thus, DIALOGUE can identify MCPs that characterize pathological cellular ecosystems and are predictive of subsequent clinical responses to interventions.

Although the UC-program marks the disease state, it is distinct from genes identified as differentially expressed between healthy and UC cells using differential gene expression analysis16 (Jaccard index: 0 – 0.14, median of 0.01) or using LIGER19 (Jaccard index: 0.05 – 0.26, median 0.12). Moreover, 72% of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) and 70% of the LIGER-DEGs are not significant associated across cell types when testing for multicellular co-regulation (mixed-effects test, BH FDR < 0.1; Online Methods).

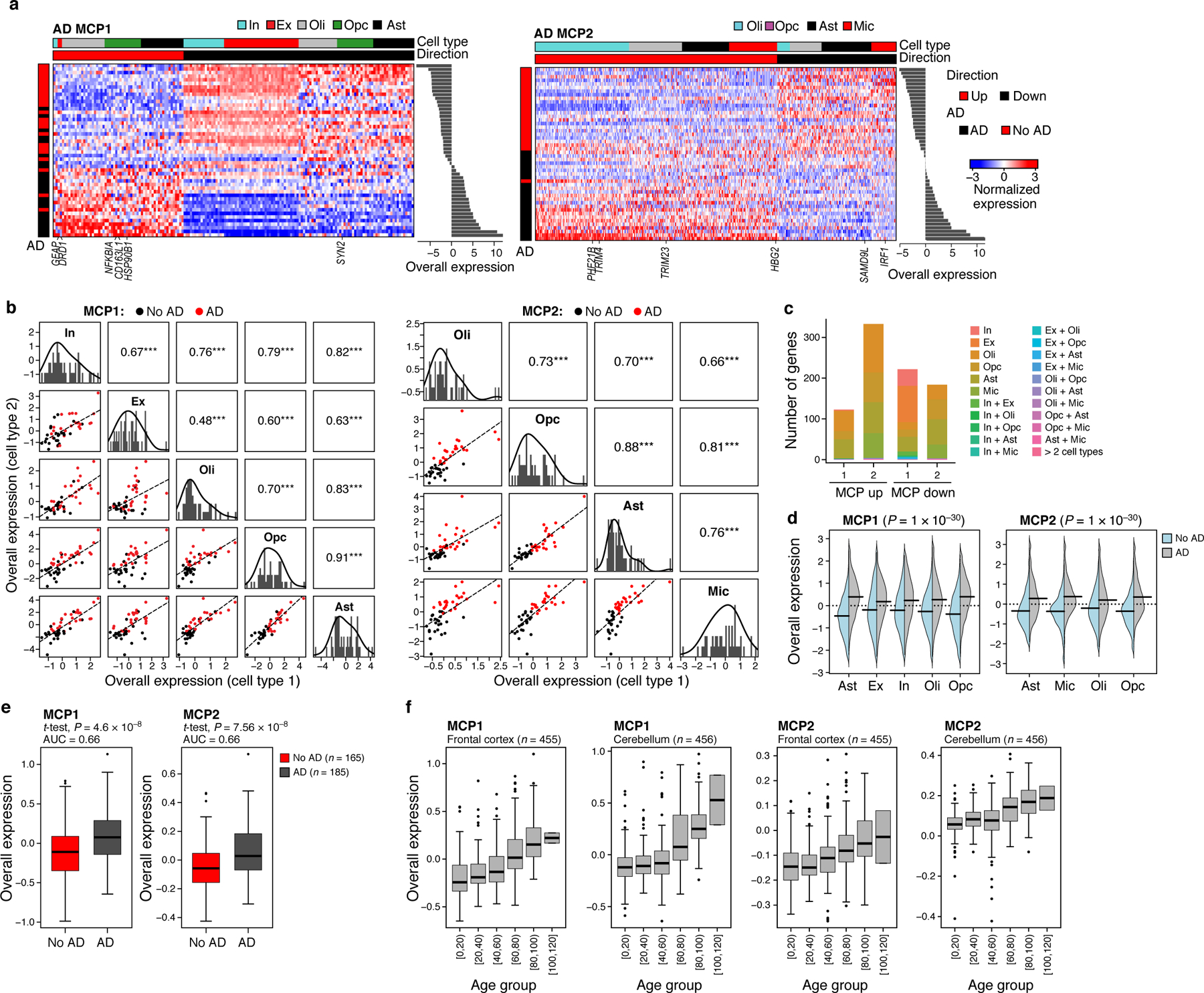

MCPs of Alzheimer’s disease mark the aging brain

Applied to 80,660 single-nucleus RNA-seq (snRNA-seq) profiles from the prefrontal cortex of 48 individuals with varying degrees of Alzheimer’s disease (AD)17 (Online Methods), DIALOGUE identified two MCPs that were substantially higher in AD patients (P < 1*10−3, mixed-effects, controlling for patient age and gender, Fig. 5a–d, Supplementary Table 3). MCP1 spans inhibitory and excitatory neurons, oligodendrocytes, oligodendrocyte-precursor-cell (OPCs), and astrocytes, while MCP2 spans oligodendrocytes, OPCs, astrocytes, and microglia. In both MCPs, the different cell type compartments are largely distinct (Fig. 5c; > 93% of the MCP genes are in a single cell type component). Further supporting MCP1 and MCP2 connection’s to AD, their different components were induced in AD also in a bulk RNA-Seq profiles from 350 brain autopsies52,53 (AUROC = 0.66, P < 1*10−6, regression model, accounting for individual age and gender, Fig. 5e, Online Methods).

Figure 5. MCP in the prefrontal cortex associated with AD pathology and aging.

(a) AD MCPs. Average expression (Z score, red/blue color bar) of top genes (columns) from the AD multicellular program, sorted by their pertaining cell type (top color bar), across samples (rows), sorted by Overall Expression (right, Online Methods), and labeled by clinical status (left color bar). (b) AD programs components across cell types. Off diagonal panels: Comparison of Overall Expression scores (y and x axes) for each cell component of MCP1 (rows and columns, labels on diagonal) across the samples (dots, black: control; red: AD); the lines correspond to the linear fit. Pearson correlation coefficient (r) and significance (***P < 1*10−3, one-sided) are shown in the upper triangle. Diagonal panels: Distribution of Overall Expression scores for each cell type component, along with the kernel density estimates. In: inhibitory neurons; Ex: excitatory neurons, Oli: oligodendrocytes, Opc: oligodendrocyte-precursor cells, Ast: astrocytes, Mic: microglia. (c) Most genes in the AD MCPs are specific to one cell component. Number of genes (y axis) in the up-regulated (left bar) and down-regulated (right bar) compartment of the AD MCPs (x axis) that belong to one cell type component or multiple ones (color legend). (d) AD MCPs components are induced across cell types in AD. Distribution of Overall Expression scores (y axis) of AD multicellular program component across the different cell subtypes (y axis) for cells from AD patients (grey) and neurologically normal subjects (light blue); black line denotes the mean of the distribution. P: One-sided p-values, mixed-effects models. (e) The overall expression of AD MCPs in brain autopsies of AD (red) and non-AD (grey) individuals. (f) AD MCPs increase with age in the frontal cortex and cerebellum of neurologically normal subjects. Overall Expression (y axis) of the AD MCPs in bulk RNA-seq of the frontal cortex (left) and cerebellum (right) of neurologically normal subjects54 stratified by age (x axis). Middle line: median; box edges: 25th and 75th percentiles, whiskers: most extreme points that do not exceed ±IQR*1.5; further outliers are marked individually. (e-f) P: linear regression, one-sided p-value.

MCP1 includes repression of synaptic signaling genes in excitatory and inhibitory neurons (P < 1*10−7, hypergeometric test), up-regulation of long-term synaptic potentiation (LTP) in excitatory neurons, and up-regulation of genes involved in cellular response to stress in oligodendrocytes and astrocytes (e.g., ATF4, HSP90B1, and MSH4, P < 9.44*10−3, hypergeometric test). MCP2 is enriched in metal and zinc ion binding genes (e.g., ZDHHC4, ZFHX3, ZMYM2, ZMYM5, ZMYND11, ZNF207, ZNF331, ZNF420) in its up-regulated (AD-associated; Fig. 5a) compartment (spanning multiple cell types; P < 1*10−5), and in interferon response genes, particularly in the microglia down-regulated compartment. The AD MCPs are distinct from genes identified using differential gene expression analysis (Jaccard index ranging from 0 to 0.12, median of 0.075), 80% of which do not pass the statistical significance cutoff when examining cross-cell-type associations (mixed-effects test, BH FDR < 0.1).

As one of the greatest risk factors for AD is increasing age, we explored the possibility that the AD-program might become more prominent with age. Indeed, the up- and down-regulated parts of the program were also respectively enriched with genes that have been previously found to be over- or under-expressed in the aging cortex (P < 6.08*10−4, hypergeometric test). Moreover, the AD-programs were strongly associated with age in bulk gene expression data from both the frontal cortex (n = 455) and cerebellum (n = 456) of neurologically normal subjects across different ages54 (P < 1*10−10, regression model; Fig. 5f).

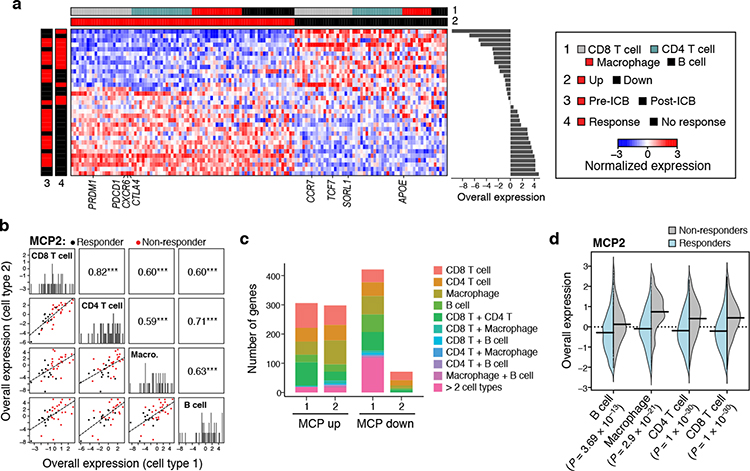

APOE repression and T cell dysfunction in a melanoma MCP

To further examine whether DIALOGUE can identify MCPs predictive of clinical response to treatment, we applied it to scRNA-Seq data from melanoma tumors55 collected before and after treatment with immune checkpoint blockade (ICB), analyzing macrophages, B cells, CD8 and CD4 T cell profiles, as those cell types were adequately represented in the majority of samples, with a total of 12,373 cells across 48 samples from 32 patients. DIALOGUE identified 3 MCPs (Fig. 6, Extended Data Fig. 5c), and they generalized to an independent scRNA-seq melanoma study18 (Pearson r = 0.89, 0.77, and 0.70, P < 1*10−4, when considering MCPs 1, 2, and 3, respectively, in CD4 and CD8 T cells; Online Methods).

Figure 6. An immunotherapy resistance MCP in melanoma tumors, linking T cell dysfunction to APOE repression in macrophages.

(a) Melanoma multicellular ICB resistance program (MCP2). Average expression (Z score, red/blue color bar) of top genes (columns) from the ICB resistance program, sorted by their pertaining cell type (top color bar), across samples (rows), with samples sorted by Overall Expression (right, Online Methods), and labeled by treatment status and ICB response (left color bar). (b) ICB program components across cell types. Off diagonal panels: Comparison of Overall Expression scores (y and x axes) for each cell component of MCP2 (rows and columns, labels on diagonal) across the samples (dots, black: responding samples, red: non-responding samples); the lines correspond to the linear fit. Pearson correlation coefficient (r) and significance (***P < 1*10−3, one-sided) are shown in the upper triangle. Diagonal panels: Distribution of Overall Expression scores for each cell type component, along with the kernel density estimates. (c) Most genes in the ICB program are specific to one cell component. Number of genes (y axis) in the up (left bar) and down (right bar) compartment of the ICB program (x axis) that belong to one cell type component or multiple ones (color legend). (d) ICB multicellular program components are induced across cell types in ICB-resistant lesions. Distribution of Overall Expression scores (y axis) of ICB program components across the different cell types (y axis) for cells from non-responding (grey) and responding (light blue) lesions. P: One-sided p-values, mixed-effects models.

MCP2 (Fig. 6) was significantly higher in ICB-resistant lesions both pre- and post-treatment (P < 1*10−10, mixed-effects,; Fig. 6a,b,d) and included APOE repression in macrophage, and induction of M2 polarization and T cell dysfunction genes (Fig. 6a; Supplementary Table 4). Indeed, ApoE is known to selectively deplete MDSCs, which in turn promotes T cell effector functions56, LXR/ApoE agonists promote anti-tumor immunity in pre-clinical models, and germline variation in APOE has been linked to ICB response in melanoma patients57. Interestingly, the program also includes one of the ApoE receptors, SORL1, as repressed in CD8 T cells, suggesting that ApoE may impact CD8 T cells directly as well.

MCP2 further includes up-regulation of CXCR6 in CD8 T cells (Fig. 6a; Supplementary Table 4), consistent with our recent findings that CXCR6 is a pan-cancer marker of dysfunctional CD8 T cells58,59, which facilitates critical interactions with myeloid cells in the tumor microenvironment58–60. Interestingly, TCF7 is repressed in the CD8 MCP2 compartment. TCF7 encodes for TCF1, a key regulators of T cell differentiation, which can bind to the CXCR6 locus based on ChIP-seq data58,61 in a chromatin region that is open in naïve T cells based on ATAC-seq data58,62. As the ligand of CXCR6 (CXCL16) is not part of MCP2, these findings supporting the notion that CXCR6 is intrinsically regulated by TCF7 in chronically activated CD8 T cells to promote their chemotaxis to CXCL16 rich niches.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we define the concept of MCPs and introduce it as a framework for studying tissue biology. We develop, benchmark, and deploy DIALOGUE, a method to recover MCPs and apply it to either spatial or single cell expression profiles. Using MCPs, DIALOGUE can accurately identify mis-localized cells and predict the cell’s environment solely based on its expression state. It can decouple cell states to their niche/sample-dependent and independent programs, reveal MCPs associated with specific phenotypes, and further decompose the niche/sample-dependent programs into generic (shared) and cell-type-specific components (Fig. 1a,b).

DIALOGUE does not rely on strong underlying assumptions and is distinct from previous supervised and unsupervised methods. It is distinct from differential gene expression analyses as it is more regularized (requiring cross-cell-type associations across samples/niches), without enforcing a particular structure (e.g., pre-defining which samples represent a disease state), retaining flexibility to identify different MCPs underlying seemingly identical phenotypes. DIALOGUE is also distinct from previous unsupervised single cell analysis and dimensionality reduction tools, as it uses gene-gene correlations both within and across cells.

DIALOGUE is also different from methods that extract spatial signatures from spatial transcriptomes. First, it does not impose a notion of discrete regions in a tissue, and instead uncovers continuous cross-cell-type patterns from spatial data. Second, DIALOGUE can uncover spatial patterns from dissociated tissues with no available spatial genomics data. Third, DIALOGUE identifies MCPs that are not necessarily associated with spatial distributions, but with variation across individuals, conditions, timepoints, etc., leveraging inter-sample variation. Such MCPs can depict biologically meaningful co-variation across individuals or conditions resulting from other shared molecular mechanisms operating on different cell types in concert (e.g., due to aging, treatment, stimulus, or genetics).

The MCPs that DIALOGUE identifies may arise due to shared (latent) factors in the cells’ micro- or macro-environment, due to shared (latent) (epi)genetic features, which impact different cell types in different ways, or due to a combination of genetic and environmental factors. The interpretation of the MCPs and their underlying causes remains a challenge, particularly because mRNA levels do not directly represent protein activation and binding, and expression responses to stimuli are context dependent.

In the future, DIALOGUE can be extended to integrate MCPs with transcriptional regulation models63 or intercellular signaling31 to further explore their molecular basis. Integrating DIALOGUE with Perturb-Seq64 data, especially when applied in vivo65 (and measured in situ66,67), or with human genetic data in larger cohorts, could provide a powerful approach to uncover the impact of perturbations on the cell and its neighbors and set the stage for causal inference of gene function in a tissue context, going from genetic causes, to single cells to tissue and phenotypes68.

While we focus here on expression profiles, DIALOGUE can be applied to any type of single cell data, from dissociated cells or in situ, including other molecular profiles or cell morphological features. Given multimodal data, it can identify both intracellular associations across different cellular modalities along with MCPs and help decouple the intracellular and multicellular processes that dictate different cellular properties (e.g., cell shape, transcriptome, proteome, etc.).

One of DIALOGUE’s current limitations is that it depends not only on the number of cells profiled, but also on the number of samples or spatial locations. As the number, size, and diversity of single-cell studies grows rapidly, and spatial transcriptomic technologies become more widely adopted, DIALOGUE should help analyze future single cell and spatial datasets, potentially in conjunction. More generally, the concepts, methodology, and problems formulated here should also prompt additional method development and provide a basis to comprehensively map the vocabulary of MCPs underlying tissue function in health and disease.

ONLINE METHODS

DIALOGUE. Overview.

Given spatial or multi-sample single-cell data, DIALOGUE identifies latent multicellular programs (MCPs), each composed of co-regulated gene sets that span multiple cell types, in two steps. In the first step, it uses PMD41 to identify sparse canonical variates that transform the original feature space (e.g., genes, PC, etc.) to a new feature space, where the different cell-type-specific representations are correlated across the different samples/environments. In the second step, given the new representation, DIALOGUE uses multilevel hierarchical modeling to identify the genes that comprise the latent features, while accounting for single-cell distributions and controlling for potential confounders.

DIALOGUE. Input.

DIALOGUE takes as input single-cell profiles with either known spatial coordinates or with sample membership. While we show applications for RNA profiles, other measurement type (e.g., protein levels, cell shape image-based features, etc.) can be used instead or in addition. In non-spatial data, it is recommended to provide a compact representation of the data using the first 20–30 Principal Components (PCs), or similar meta-features derived using other dimensionality reduction methods on each cell type separately. DIALOGUE prunes the input to includes only features that show greater variation across samples than within a sample based on ANOVA tests (BH FDR < 0.05).

DIALOGUE. PMD step.

If the data is from dissociated tissue samples or biofluids, DIALOGUE first constructs for each cell type z a matrix Xz, where (Xz)ij denotes the average value of feature j (e.g., the expression of gene j or the value of PC j) in cell type z in sample i, following centering and scaling. This is defined as

where Si denotes all the cells in sample i, Cz denotes all the cells of type z, and Ec,j denotes the value of feature j in cell c.

If the data includes a cell’s spatial coordinates, a spatial niche is defined as a patch of a given number of cells, such that (Xz)ij, denotes the average value of feature j in cells of type z in the spatial niche i. If the spatial data includes multiple samples, each column in Xz will denote a specific location in a specific sample. Data hierarchy will be accounted for in the multilevel models.

The number of features in each Xz can vary and does not have to be the same across the different cell types.

Given matrices X1,...,XN representing N cell types, DIALOGUE applies PMD41 to find sparse canonical variates w1,...,wN by solving the following optimization problem

where represent the LASSO penalties, and the tuning parameters control the degree of sparsity. For each pair of cell types i and j, , and therefore the resulting canonical variates identify a latent space where the new feature of cell type i (i.e., Xiwi) are highly correlated with the new features of all the other cell types. The additional constrains ensure regularization and sparsity.

To select the tuning parameters, we defined as the optimal value of the optimization function described above, when using a particular set of tuning parameters c1,...,cN. We defined as the optimal value of the same optimization function and tuning parameters when using instead of the original dataset, where is the original data matrix after permutation. For each set of candidate tuning parameters, the data is permuted multiple times and an empirical p-value is computed based on the number of times that . The tuning parameters that obtain the smallest p-value are selected.

In an iterative process termed multi-factor PMD41, DIALOGUE identifies K latent features for each cell type, . In practice, the new features of each cell type are orthogonal, minimizing redundancies, such that the greatest cross-cell-type correlations are observed at k = 1, gradually decreasing with increased k.

The new feature space is then defined at the single-cell level

where ) is the original feature space of cell type z (e.g., normalized gene expression), and Wz(pz x K) is the matrix of the sparse canonical variates identified for cell type z. While the user can use different K values as input, DIALOGUE will always output the same kth program for any K ≥ k.

DIALOGUE. Data-driven identification of the cell types participating in each MCP.

Following the PMD step, DIALOGUE uses the correlation coefficients and permutation tests to determine which cell types take part in each MCP and applies the multilevel test only on those cell types. Second, given a set of cell types, DIALOGUE performs the first PMD step both in a multi-way manner and in a pairwise manner. If it identifies programs that are unique to the pairwise version it includes them in the multilevel modeling step and final output.

DIALOGUE’s ability to identify the relevant cell types participating in each MCP was assessed using the melanoma scRNA-seq data55 of macrophages, B cells, CD4 and CD8 T cells. Each time, the expression matrix of one of the cell types was randomly shuffled and provided to DIALOGUE together with the real (unshuffled) matrices of the other three cell types. All the MCPs identified involved only the real cell types and were identical to those identified when providing only the unshuffled data of the three cell types.

DIALOGUE. Multilevel modeling step.

After DIALOGUE defined a new feature space, it identifies a gene signature for each sparse canonical variate, by interrogating the single-cell distributions, while accounting for potential confounding factors at different levels (e.g., patient age, gender, sample type, cell sequencing quality, etc.).

For each of the K latent feature sets, DIALOGUE defines a set of N signatures (one per cell type), denoted as .

A gene g is in sr,k if its expression in cell type r is correlated with the pertaining latent feature of cell type r, and with the pertaining latent features of the other cell types. The former is evaluated using partial Spearman correlation (BH FDR < 0.05; with at most 250 up or down regulated genes per cell type), when controlling for cell quality, using the log-transformed number of reads detected in each cell. The latter is tested using the following multilevel model

where is the value of the latent feature in cell i in sample j, xij,f is a cell-level covariate that controls for potential confounding factors (e.g., log-transformed number of reads), and αj is the sample j intercept, defined as

where are sample-level covariates of sample j (e.g., patient age, gender), and (Xz)jg is the average expression of gene g in cell type z in sample j.

The multilevel modeling p-values are used to rank the genes in each program. The model parameters and the pertaining p-values are computed using the lme469 (https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/lme4/index.html) and lmerTest R packages70.

Assessing DIALOGUE’s ability to recover MCPs involving rare cell states.

scRNA-Seq data from melanoma was down-sampled to such that less than 2% of B cells were classified as plasma cells and less than 4% of the CD8 T cells were classified as cycling CD8 T cells. To simulate the co-occurrence of rare populations, rare cell states were retained only in 6 out of 32 samples. Applying DIALOGUE to this dataset, one of the MCPs depicts the co-expression of cell cycle genes in CD8 T cells and the plasma cell program in B cells (P = 1*10−10, hypergeometric test; P < 1*10−16, ranksum test), despite their low frequency in the dataset.

Generalizability and mitigating overfitting.

For further regularization, DIALOGUE: (1) computes empirical p-values for each MCP, by comparing to a null model derived from shuffling the data, re-running the MCP detection procedures above, and quantifying the statistical significance of the MCPs identified with the real data; and (2) splits the original data to train and test sets or, if provided as input, uses unseen external datasets to examine the MCPs generalizability. If MCPs fail to show sufficient statistical significance or fail to generalize, it is recommended to use a smaller number of features as input or tune the regularization parameter to have more sparsity in the PMD solution.

Considerations in application of DIALOGUE to spatial data.

When applied to spatial data, the data is partitioned into spatial niches of a predefined size dmax (e.g., dmax = 100 μm) or, in the pairwise setting, to direct neighbors (i.e., the closest neighboring cell with a distance <= dmax). Not all niches will include all cell types. In the applications to spatial data presented here, DIALOGUE accounted only for niches where all the cell types of interest were present. To support applications for MCPs with a larger number of cell types, DIALOGUE also include a user defined parameter Nmin, allowing the user to choose to account for all the niches that include at least Nmin of the cell types of interest. Nmin can be as small as 2. If Nmin is less than the full number of cell types of interest, in the PMD step, where (Xz)ij denotes the average value of feature j in cells of type z in the spatial niche i, DIALOGUE will now also include niches where cell type z is not present and fill those in as zeros (i.e., the entire row i in Xz will be zeros). This will not impact the part of the optimization that involves cell type z, as the PMD step solves the following optimization problem

where matrices X1,...,XN represent N cell types, and w1,...,wN denote sparse canonical variates.

The multilevel step is based on pairwise analyses of cell types and thus can account for different niches when analyzing each pair without the need for the “missing” zero value addition described above.

Testing DIALOGUE as a cell location predictor.

To test if DIALOGUE can predict cell location based on the MCPs it identifies, each spatial genomics data was split randomly to training and test sets, using half of the samples for training and the other half for testing. The expression of the MCPs identified in the training set was then computed for the cells in the test set. For each pair of cell types the Euclidean distance between them in this k dimensional space was computed. ROC curved were then obtained to examine if this distance measure distinguishes between the adjacent and non-adjacent pair from the same sample, with a smaller distance increasing the likelihood that the two cells will be adjacent. The same procedure was performed when considering the Euclidean distance based on the original gene expression data and based on the first 20 PCs obtained when processing all the cells together.

DIALOGUE-SVM.

scRNA-Seq data from spatially defined regions of the mouse neocortex38 were provided to DIALOGUE as a training set to identify MCPs. Next, for each cell type, a multiclass Support vector machine (SVM) was trained on a subset of training data with the different spatial regions provided as target labels and the MCPs provided as features. The SVM model was then tested on the unseen test set. SVM was applied using the e1071 R package with default parameters.

Comparing MCPs to annotated gene sets.

MCPs were compared to annotated gene sets using hypergeometric enrichment tests. Multilevel mixed-effects models were used to test whether the Overall Expression (OE) of MCPs and pre-defined gene set were correlated across cells of a specific cell type. In this setting, the OE of one program is a dependent variable and that of the other is provided as a covariate. The other covariates used are the log-transformed number of reads detected per cell (scaled to a range of 0–1), sample identity, and donor/patient/animal sex.

DIALOGUE. Environment-score metric.

The environment-score (Es) is defined based on the difference between the expected and observed cell state, given the identified MCPs.

where is the value of feature k (e.g., program k) in cell i of cell type z in sample j, and is the number of cells of cell type z’ in sample j.

To test if this measure can identify mis-localized cells, we used the colon/IBD data16. We performed an in silico contamination of the data by adding to each sample ~50 cells (10 per cell type) from an “adjacent” sample obtained from the same individual. These “adjacent samples” could be from the same or different layer (LP/EPI) and have the same or a different clinical status (both healthy, or inflamed and uninflamed). Applied to this “contaminated” data, DIALOGUE identified MCPs spanning TA1, TA2, macrophages, CD8 and CD4 T cells, and computed the environment-scores as described above.

The predictions were tested per cell type (Fig. 4a, Extended Data Fig. 5a), when considering all cells, only control patients, only IBD patients, or only specific types of mis-localization, namely, erroneous tissue compartment (LP vs. EPI), same tissue type but different clinical status (considering only IBD samples, where inflamed and non-inflamed samples were collected for the same patient), and adjacent sample of the same tissue type (considering only control samples where similar samples were obtained from the same individual).

DIALOGUE application to spatial transcriptomic data from the mouse hypothalamus.

MERFISH data10 was retrieved from DRYAD (https://datadryad.org/stash/dataset/doi:10.5061/dryad.8t8s248), where expression values for the 135 genes measured in the combinatorial smFISH run were determined as the total counts per cell divided by the cell volume and scaled by 1,000. Expression values for the 21 genes measured in non-combinatorial, sequential FISH rounds were arbitrary fluorescence units per μm3, such that the same scale was used for all cells. The expression values were then centered and scaled for all genes. The gene Fos was not included in the analyses, as it was not measured in all cells, resulting in 155 genes. “Cell class” annotations and the “neuron cluster_ID” were used to assign cells to cell types and subtype.

The scaled and centered gene expression matrix was used as the “original features space” (Fig. 1b, “input”). Niches were defined based on the two-dimensional coordinates of the cells’ centroid positions as patches of fixed diameter of 75 μm or 440 μm, such that they respectively include, on average, 15 or 500 adjacent cells, denoted as micro- and macro-environments. In the pairwise version, each cell is paired with its closest neighbor, and cells that do not have a close enough neighbor (< 50μm apart) are not considered.

DIALOGUE application to colon scRNA-Seq data.

Processed scRNA-seq of 68 colonoscopic biopsies (each ~2.4 mm2) from 12 healthy individuals and 18 UC patients16. was downloaded from the single cell portal (https://singlecell.broadinstitute.org/single_cell/study/SCP259/intra-and-inter-cellular-rewiring-of-the-human-colon-during-ulcerative-colitis#study-download). Genes that were identified in the original study16 as having been contaminants from putative ambient RNA were removed. The “original feature space” was the top 30 PCs, where PCs were computed based on the gene expression of the top 2,000 most variable genes, defined using the Seurat package FindVariableFeatures function. In this procedure, local polynomial regression (LOWESS) is used to estimate the expected variance given the average gene expression values across the cells, on a log-log scale. Deviation from the expected value is then used to identify overdispersed genes.

DIALOGUE application to AD snRNA-seq.

DIALOGUE was applied to snRNA-seq data from the prefrontal cortex of 48 individuals with varying degrees of AD pathology17. The data was previously generated as a part of the Religious Orders Study (ROS) or the Rush Memory and Aging Project (MAP) study (ROS/MAP). Data was downloaded from the AMP-AD Knowledge Portal (Synapse IDs: syn18686381, syn18686382, syn18686372) through controlled access, subject to the use conditions set by human privacy regulations.

To capture disease-related variation, which in this case was subtler and potentially masked by other sources of cell-cell variations, PCs were first computed based on genes that showed at least moderate association with the disease state (t-test p-value < 0.1, without correction for multiple hypotheses). The top 30 PCs were used as the original feature space (Fig. 1b, “input”).

Bulk RNA-Seq data from the ROS/MAP study was used to examine the AD program in a larger cohort of 638 cortex autopsies52,53. Data was downloaded from AMP-AD Knowledge Portal (Synapse IDs: syn3505720) through controlled access, subject to the use conditions set by human privacy regulations. For each sample the OE of the AD program was computed, using a scheme that filters technical variation and highlights biologically meaningful patterns, as described previously18,71. Samples from patients with non-definitive diagnosis (CERAD score of 2 or 3) were discarded, and the association of the AD program OE with disease status (AD or non-AD, defined as CERAD scores of 1 and 4, respectively) was examined using a linear regression model that accounts for the individuals’ age and gender.

DIALOGUE multilevel model in specific applications.

The multilevel models used in the applications to UC colon, prefrontal cortex in AD and melanoma data was formulated as follows

Where, xij denotes the number of genes detected in cell i in sample j; (Xz)jg denotes the expression of MCP g in cell type z of sample j; u1j denotes the sequencing depth of sample j (the average number of genes detected per cell on average, when considering the cells of cell type z), u2j and u3j are binary covariates that denote the sex and the disease status of the donor/patient, respectively. The disease covariate was used only in the colon and cortex datasets, as those also included data from healthy donors. All covariates were scaled to be within a similar range for statistical purposes. The statistical multilevel model was constructed with sample-specific intercepts to account for the inter-dependencies within each sample.

Examining differentially expressed genes as MCPs.

Differentially expressed gene sets were retrieved from the IBD16 and AD17 studies. The same analysis preformed in the multilevel DIALOGUE step was performed on these sets, only that instead of providing the MCPs identified in the PMD step, the DEGs (identified for the different cell types) were provided. The fraction of genes that show a cross-cell-type association (BH FDR < 0.1, mixed-effects test) was computed. DEGs were also defined here via LIGER19, splitting each dataset based on the disease status to identify shared and context-specific programs, with the recommended default parameters, using the code provided at: https://github.com/welch-lab/liger. The same process described above was implemented to examine the resulting LIGER-DEGs as MCPs.

Putative cell-cell interactions mediated by ligand-receptor binding.

DIALOGUE starts from a graph of cognate ligand-receptor pairs72. Given an MCP, each cell type is added to this ligand-receptor graph as another node, which is connected with edges to all of the genes in its compartment. “Protein nodes” (i.e., representing ligands and receptors) are retained only if they are connected to a cell type directly or through another protein node, and are removed otherwise. The number of unique paths from a given protein node to all cell nodes can be used to identify potential mediators of the MCPs latent when considering only RNA levels.

Code availability.

DIALOGUE is implemented as an R package and can be installed using the devtools::install(“DIALOGUE”) command. Further documentation and tutorials are provided in the package help pages (e.g., ?DIALOGUE). We also provide DIALOGUE via GitHub (https://github.com/livnatje/DIALOGUE) and KCO repository10, along with additional guidelines and specifications.

Extended Data

Extended Data Figure 1. DIALOGUE identified MCPs in the mouse hypothalamus that are not recovered with other dimensionality reduction and clustering approaches.

(a)* Pearson correlation coefficient between genes, PCs, NMF, and DIALOGUE MCPs from either the training or the test set (x axis) across different pairs of cell types (panels) in spatial niches in the mouse hypothalamus. (b) Pearson correlation coefficient (red/blue, color bar) between the Overall Expression of the relevant MCP component when considering only defined subsets of the pertaining cell types (rows, columns), as previously identified by clustering10. White: missing values (cell subtypes that cannot be compared). (c) MCPs are not merely driven by cell subtype composition in a niche. Fraction of cells from different clusters (as previously defined10, y axis) among cells of a given type (label on top) that over- or under-express the relevant component of each pair-wise MCP1 (top or bottom 25%, respectively, x axis) involving that cell type. (d)* Similarity (y axis, Spearman’s r) between the gene loadings of MCPs identified in the microenvironment setting (x axis) and the gene loadings of matching MCPs identified in the micro-environment setting, when computed for different pairs of cell types using MERFISH data. *In both (a) and (d) middle line: median; box edges: 25th and 75th percentiles, whiskers: most extreme points that do not exceed ±IQR*1.5; further outliers are marked individually.

Extended Data Figure 2. DIALOGUE captures spatial patterns.

(a) Average Overall Expression in a niche (dot, 15 cells on average) of the first MCP (MCP1) in the first (x axis) and second (y axis) cell type in that MCP. In red is the locally weighted polynomial (LOWESS) regression line. (b) As in (a), but depicting the Overall Expression residuals after regressing out impact of cell clusters, as previously defined10. (a-b) Spearman correlation coefficient (R) and significance (P, one-sided). (c) Performance (AUROC, y axis) when predicting the expression of the corresponding DIALOGUE component in the neighboring cells located in the same macro-environment (dark blue, ~500 cells) or micro-environment (purple, and light blue, ~15 cells), when testing on unseen test set; the training data includes either spatial coordinates and single-cell profiles (light blue, “spatial data”) or only single cell profiles from ~500 cell aggregates, without spatial information (“dissociated”, Online Methods).

Extended Data Figure 3. MCPs mark spatial patterns and phenotypes.

(a) Overall Expression of HMRF37 domain-specific programs in neighboring pairs of glutamatergic (y axis) and GABAergic (x axis) neurons from different regions (colors). (b) Overall Expression of the relevant components of MCPs 1–5 in glutamatergic (y axis) and their adjacent GABAergic (x axis) neurons from different regions (colors). (a-b) Spearman correlation coefficient (R) and significance (P, one-sided).

Extended Data Figure 4. MCPs mark spatial patterns and phenotypes.

(a) Spatial distribution of MCPs and HNRF programs. Overall Expression of MCPs identified by DIALOGUE and the HMRF37 domain programs in glutamatergic (circles) and GABAergic (dots) neurons in the mouse visual cortex. As shown, while many of the patterns follow either a more layered or salt and pepper pattern, MCP2 distinguished a more discrete region. While such boundaries sometimes reflect measurement artifacts, we did not find an association with number of genes/reads (typical quality measures) nor with simple alignment with Fields of View (FOV). (b,c) Shared and cell type specific components in DIALOGUE MCP1s in the mouse hypothalamus. (b) Fraction of genes (y axis) that are shared (yellow) or specific to one (A, dark blue) or another (B, light blue) of the cell types in each of the hypothalamus MCPs (x axis). (c) The two cell programs in each of the MCPs in (b) and their specific and shared (intersection) genes. P-values denote association with naïve animal behavior (multilevel mixed-effects models, two-sided test).

Extended Data Figure 5. DIALOGUE identifies mis-localized cells and disease MCPs in single-cell data.

(a) ROC curves showing the true positive (y axis) and false positive (x axis) rate when predicting mis-localized cells of each major subset (panels) with different types of “contamination” with cells that are either from the same layer (LP/EPI) within control (black, from replicate biopsy) or UC (blue; from adjacent biopsy with a different clinical status: inflamed or non-inflamed); or from a different layer but same clinical status, when considering either all samples (green) or only samples from control (yellow) or UC patients (red). (b) UC multicellular program genes. Average expression (Z score residuals after regressing out the associations with the LP/EPI location, red/blue color bar) of top genes (columns) from the UC multicellular program, sorted by their pertaining cell type (top color bar), across samples (rows), sorted by Overall Expression (right, Online Methods), and labeled by clinical status, location and patient ID (left color bar). (c) Melanoma MCP1. Average expression (Z score, red/blue color bar) of top genes (columns) from MCP1 identified in four different cell types (top color bar), across melanoma tumor samples (rows), sorted by Overall Expression of MCP1 (right, Online Methods), and labeled by treatment status and ICB response (left color bar).

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Table 1. MCPs identified in the (A) mouse hypothalamus, (B) mouse cerebellum, and (C) human NSCLC, based on MERFISH10, Slide-Seq, and SMI data, respectively.

Supplementary Table 2. IBD MCP identified in human colon based on scRNA-Seq data16.

Supplementary Table 3. AD MCPs identified based on single-nucleus data from brain autopsies17.

Supplementary Table 4. Melanoma MCPs identified based on scRNA-Seq data55.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Leslie Gaffney and Anna Hupalowska for help with figure preparation. L.J.A. is a Chan Zuckerberg Biohub Investigator and holds a Career Award at the Scientific Interface from Burroughs Wellcome Fund (BWF). L.J.A. was a CRI Irvington Fellow supported by the CRI, and a fellow of the Eric and Wendy Schmidt Postdoctoral program. A.R. was an HHMI Investigator. Work was supported by the Klarman Cell Observatory, NIDDK RC2 DK114784, the Food Allergy Science Initiative, the Manton Foundation, and HHMI. The AD dataset was provided by the Rush Alzheimer’s Disease Center, Rush University Medical Center, Chicago. Data collection was supported through funding by NIA grants P30AG10161, R01AG15819, R01AG17917, R01AG30146, R01AG36836, U01AG32984, U01AG46152, U01AG61356, the Illinois Department of Public Health, and the Translational Genomics Research Institute.

Footnotes

COMPETING INTERESTS STATEMENT

A.R. is a co-founder and equity holder of Celsius Therapeutics, an equity holder in Immunitas Therapeutics, and until July 31, 2020 was a scientific advisory board member of ThermoFisher Scientific, Syros Pharmaceuticals, Asimov, and Neogene Therapeutics. From August 1, 2020, AR is an employee of Genentech, a member of the Roche group, and has equity in Roche. The remaining authors declare no competing interests.

DATA AVAILABILITY

The datasets analyzed in this study include: seqFISH data37 and HMRF37 annotations obtained from https://bitbucket.org/qzhu/smfish-hmrf/src/master/hmrf-usage/; scRNA-Seq from the mouse neocortex obtained via the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO), accession GSE11574638; Slide-Seq data11 obtained via the Single Cell Portal https://singlecell.broadinstitute.org/single_cell/study/SCP354/slide-seq-study#study-summary; MERFISH data10 obtained from the DRYAD repository https://datadryad.org/stash/dataset/doi:10.5061/dryad.8t8s248; SMI data from human NSCLC samples39, including cell type annotations, were retrieved from https://www.nanostring.com/products/cosmx-spatial-molecular-imager/ffpe-dataset/. scRNA-Seq data of colon biopsies16 obtained from the Single Cell Portal https://singlecell.broadinstitute.org/single_cell/study/SCP259/intra-and-inter-cellular-rewiring-of-the-human-colon-during-ulcerative-colitis#study-download; single-nucleus RNA-Seq (snRNA-seq) data from human prefrontal cortex17 obtained via AMP-AD Knowledge Portal https://adknowledgeportal.synapse.org/ (Synapse IDs: syn18686381, syn18686382, syn18686372, and syn3505720; available through controlled access, subject to the use conditions set by human privacy regulations); melanoma and brain organoid single cell data obtained via GEO, accession numbers GSE12057555, GSE11597818, and GSE8615343.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hong S & Stevens B Microglia: Phagocytosing to Clear, Sculpt, and Eliminate. Dev Cell 38, 126–128 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ribeiro M et al. Meningeal γδ T cell–derived IL-17 controls synaptic plasticity and short-term memory. Sci. Immunol 4, eaay5199 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schwartz M Can immunotherapy treat neurodegeneration? Science 357, 254 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baruch K et al. PD-1 immune checkpoint blockade reduces pathology and improves memory in mouse models of Alzheimer’s disease. Nature Medicine 22, 135 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Joyce JA & Fearon DT T cell exclusion, immune privilege, and the tumor microenvironment. Science 348, 74–80 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Corrigan-Curay J et al. T-cell immunotherapy: looking forward. Mol. Ther. 22, 1564–1574 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hauser SL et al. B-cell depletion with rituximab in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med 358, 676–688 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Macosko EZ et al. Highly Parallel Genome-wide Expression Profiling of Individual Cells Using Nanoliter Droplets. Cell 161, 1202–1214 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McDavid A et al. Data exploration, quality control and testing in single-cell qPCR-based gene expression experiments. Bioinformatics 29, 461–467 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moffitt JR et al. Molecular, spatial, and functional single-cell profiling of the hypothalamic preoptic region. Science 362, eaau5324 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rodriques SG et al. Slide-seq: A scalable technology for measuring genome-wide expression at high spatial resolution. Science 363, 1463 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Burgess DJ Spatial transcriptomics coming of age. Nature Reviews Genetics 20, 317–317 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kotliar D et al. Identifying gene expression programs of cell-type identity and cellular activity with single-cell RNA-Seq. eLife 8, e43803 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zheng C et al. Landscape of Infiltrating T Cells in Liver Cancer Revealed by Single-Cell Sequencing. Cell 169, 1342–1356.e16 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Azizi E et al. Single-Cell Map of Diverse Immune Phenotypes in the Breast Tumor Microenvironment. Cell 174, 1293–1308.e36 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Smillie CS et al. Intra- and Inter-cellular Rewiring of the Human Colon during Ulcerative Colitis. Cell 178, 714–730.e22 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mathys H et al. Single-cell transcriptomic analysis of Alzheimer’s disease. Nature 570, 332–337 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jerby-Arnon L et al. A Cancer Cell Program Promotes T Cell Exclusion and Resistance to Checkpoint Blockade. Cell 175, 984–997.e24 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Welch JD et al. Single-Cell Multi-omic Integration Compares and Contrasts Features of Brain Cell Identity. Cell 177, 1873–1887.e17 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]