Abstract

Integrons are genetic elements capable of integrating genes by a site-specific recombination system catalyzed by an integrase. Integron integrases are members of the tyrosine recombinase family and possess the four invariant residues (RHRY) and conserved motifs (boxes I and II and patches I, II, and III). An alignment of integron integrases compared to other tyrosine recombinases shows an additional group of residues around the patch III motif. We have analyzed the DNA binding and recombination properties of class I integron integrase (IntI1) variants carrying mutations at residues that are well conserved among all tyrosine recombinases and at some residues from the additional motif that are conserved among the integron integrases. The well-conserved residues studied were H277 from the conserved tetrad RHRY (about 90% conserved), E121 found in the patch I motif (about 80% conserved in prokaryotic recombinases), K171 from the patch II motif (near 100% conserved), W229 and F233 from the patch III motif, and G302 of box II (about 80% conserved in prokaryotic recombinases). Additional IntI1 mutated residues were K219 and a deletion of the sequence ALER215. We observed that E121, K171, and G302 play a role in the recombination activity but can be mutated without disturbing binding to DNA. W229, F233, and the conserved histidine (H277) may be implicated in protein folding or DNA binding. Some of the extra residues of IntI1 seem to play a role in DNA binding (K219) while others are implicated in the recombination activity (ALER215 deletion).

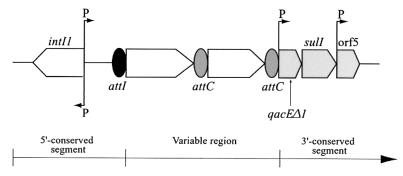

Integrons are DNA elements that can mediate the dissemination of antibiotic resistance genes by a site-specific recombination system (37). They possess two conserved segments separated by a variable region which includes integrated antibiotic resistance genes or cassettes of unknown function (Fig. 1). The essential components of the integron are found within the 5′ conserved segment and include an integrase gene intI (28) and an adjacent recombination site attI (13, 34).

FIG. 1.

General structure of class 1 integrons. Cassettes are inserted in the variable region by the integrase using a site-specific recombination mechanism. The attI and attC sites are shown, respectively, by black and grey ovals and promoters are denoted by “P.” intI1, integrase gene; qacEΔ1, antiseptic resistance gene; sulI, sulfonamide resistance gene; orf5, gene of unknown function.

Four classes of integron have been described (25, 32), each of which codes for a distinct but related integrase enzyme. Class 1 integrons (Fig. 1) are the most widespread, with a 5′ conserved segment that contains a promoter region from which integrated cassettes are expressed (7, 23). The 3′ conserved segment contains a qacEΔ1 gene encoding resistance to quaternary ammonium compounds and most also contain a sulI gene encoding resistance to sulfonamides, an open reading frame (ORF5) of unknown function, and other sequences that differ from one integron to another (1, 3, 30, 31). The gene cassettes, which may be found within the variable region of integrons, are mobile, nonreplicating elements which comprise an open reading frame (usually lacking a promoter region) associated with an integrase-specific recombination site, attC, also known as the 59-base element (17, 20, 32, 38).

IntI1 is a member of the tyrosine recombinase family (8, 27) and catalyzes the excision and integration of antibiotic resistance genes in class 1 integrons by a site-specific recombination system. These reactions are carried out by the integrase interacting with the two different recombination sites, the attI site in the 5′ conserved segment of the integron and the attC sites of the gene cassettes. The attC site lengths and sequences vary considerably (from 57 to 141 bp) and their similarities are restricted to their boundaries, which correspond to the inverse core site (RYYYAAC) and the core site (GTTRRRY) (38). There is no inverse core site in the attI site so it cannot form a palindromic structure like attC sites. Cassettes are excised in a circular form and are integrated at core sites defined as GTTRRRY (6), with the crossover located between the G and the first T (20, 34). It is not yet clear if the cleavage occurs at the same place on both DNA strands or if it is a staggered cleavage. Some suppose that only one strand is cleaved by the integrase and the resulting Holliday junction is resolved by a cellular enzyme like RuvC (38). IntI1 can also act at secondary sites containing a degenerate core site (9, 33).

Site-specific recombination requires short and specific DNA sequences with only limited homology and involves the formation of a Holliday junction intermediate (10, 40). It is a conservative process in which all DNA strands that are broken are rejoined without ATP utilization or DNA synthesis. Site-specific recombinases are divided into two families, the resolvase family and the integrase family. The latter includes about 200 highly diversified members such as λ integrase, Cre, Flp, and XerC-XerD (8, 27). The integrase nucleophile is a tyrosine located at the C-terminal end of the protein. This tyrosine is responsible for the cleavage and forms a covalent intermediate by esterification of a DNA 3′-phosphoryl group. The joining reaction is mediated by nucleophilic attack of the 5′-hydroxyl group from the same strand or another cleaved strand (12).

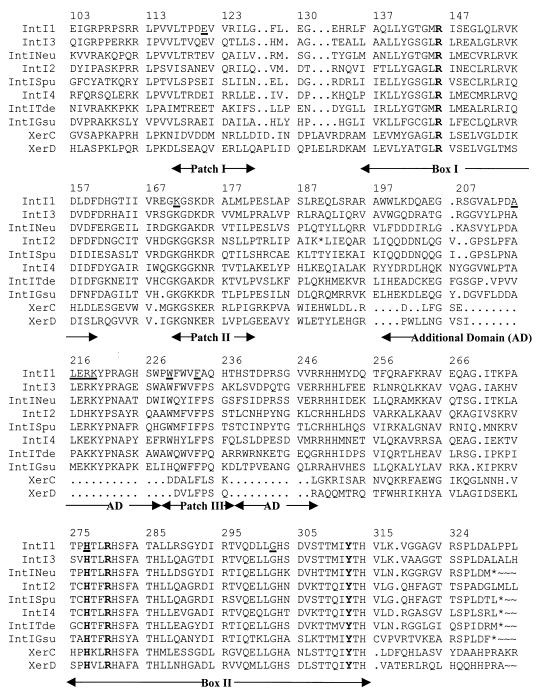

The integrase family definition is based on identification of conserved residues (RHRY) found in two boxes (I and II) located in the carboxyl half of the protein. Only the histidine is not invariant but is present in nearly 95% of the members (8). A recent analysis has identified three patches (I, II, and III) of residues which seem to play a role in the secondary structure of these enzymes (27), and a potentially essential fifth catalytic residue (lysine) has been identified (4). The following five tyrosine recombinases have been partially or totally crystallized: the λ Int and HP1 Int catalytic domains, the XerD protein, and the Cre and Flp recombinases-DNA complexes (5, 11, 15, 16, 21, 22, 39, 40). Alignment of integron integrases with other tyrosine recombinases shows that they possess an additional group (about 35 residues) of amino acids near the patch III motif (14, 26, 27) containing several residues which are conserved among the integron integrases (Fig. 2). This special feature has led to the identification of several new integron integrases (26, 35) and some have been tested for the ability to excise class 1 integron cassettes (F. Drouin and P. H. Roy, Abstr. 101st Gen. Meet. Am. Soc. Microbiol., abstr. H-19, 2001).

FIG. 2.

Alignment of C-terminal integron integrase sequences with those of other tyrosine recombinases. IntI1, class 1 integron integrase from plasmid pVS1; IntI2, class 2 integron integrase from Tn7; IntI3, class 3 integron integrase from a Serratia marcescens plasmid; IntI4, class 4 integron integrase from the Vibrio cholerae super-integron; IntISpu, integron integrase from Shewanella putrefaciens; IntINeu, integron integrase from Nitrosomonas europaea; IntITde, integron integrase from Treponema denticola; IntIGsu, integron integrase from Geobacter sulfurreducens; XerC, recombinase from E. coli; XerD, recombinase from E. coli. There are two potential IntI's in N. europaea; the one shown is the most likely to be translated. Numbering is based on the IntI1 sequence and residues mutated in this study are underlined. The additional domain and the different boxes and motifs are indicated under the alignment. Residues from the conserved tetrad (RHRY) are shown in bold.

IntI1 possesses the four conserved residues (RHRY) of the family and other well-conserved residues and motifs (boxes I and II and patches I, II, and III) (8, 27). A study of IntI1 variants for the conserved RRY residues has shown that mutations of the conserved arginines by nonpositively charged residues abolish substrate recognition, while mutant proteins of the conserved tyrosine bind the attI1 site but are unable to catalyze recombination (14). In this study, we analyzed the properties of several mutants of conserved residues, potentially located in the active site of tyrosine recombinases (K171, H277, and G302) or within conserved, noncatalytic regions (E121, W229, and F233), and of additional residues conserved among integron integrases (ΔALER215 and K219) fused with the maltose binding protein (MBP) protein in in vivo recombination and in vitro substrate binding. We also show that the cellular enzyme RuvC is not responsible for the second DNA strand cleavage in the integron site-specific recombination reaction.

Construction of plasmids overexpressing mutant MBP-IntI1 fusion proteins.

The plasmids encoding various mutants of MBP-IntI1 were constructed by PCR using the QuickChange site-directed mutagenesis kit of Stratagene with pLQ369 (50 ng) as a template (14). Two complementary primer pairs, designed with the OLIGO software package (version 4.1; National Biosciences, Plymouth, Minn.), were used to construct each mutant (Table 1). PCR conditions were 10 min at 95°C; 30 cycles consisting of 1 min at 95°C, 1 min at the appropriate annealing temperature (Table 1), and 15 min at 72°C; and a final elongation step of 20 min at 72°C. Since the PCR amplified the complete vector because of the complementary primers, the nonmutated methylated parental DNA was digested with the restriction enzyme DpnI. The uncut mutated DNA was then introduced into Escherichia coli XL1-Blue {recA1 endA1 gyrA96 thi-1 hsdR17 supE44 relA1 lac [F′ proAB lacIqZΔM15 Tn10(Tetr)]} from Stratagene and grown at 37°C on Luria-Bertani ampicillin plates. Mutant plasmids were purified and sequenced to determine the mutations (Table 2).

TABLE 1.

Primers used in this study

| Primer pair | Sequence | Annealing temp used (°C) |

|---|---|---|

| E121DintI1UP | GACCCCGGATGATGTGGTTCGCATCCTCGG | 52 |

| E121DintI1LO | CGGAGGATGCGAACCACATCATCCGGGGTC | 52 |

| E121KintI1UP | GACCCCGGATAAAGTGGTTCGCATCCTCGG | 50 |

| E121KintI1LO | CGGAGGATGCGAACCACTTTATCCGGGGTC | 50 |

| K171QintI1UP | GTGCGGGAGGGCCAGGGCTCCAAGG | 52 |

| K171QintI1LO | CCTTGGAGCCCTGGCCCTCCCGCAC | 52 |

| K171EintI1UP | GTGCGGGAGGGCGAGGGCTCCAAGG | 52 |

| K171EintI1LO | CCTTGGAGCCCTCGCCCTCCCGCAC | 52 |

| K171IintI1UP | GTGCGGGAGGGCATAGGCTCCAAGG | 48 |

| K171IintI1LO | CCTTGGAGCCTATGCCCTCCCGCAC | 48 |

| K171VintI1UP | GTGCGGGAGGGCGTGGGCTCCAAGG | 52 |

| K171VintI1LO | CCTTGGAGCCCACGCCCTCCCGCAC | 52 |

| K171RintI1UP | GTGCGGGAGGGCAGGGGCTCCAAGG | 52 |

| K171RintI1LO | CCTTGGAGCCCCTGCCCTCCCGCAC | 52 |

| ALER215intI1UP | GTTGCGCTTCCCGACAAGTATCCGCGCG | 51 |

| ALER215intI1LO | CGCGCGGATACTTGTCGGGAAGCGCAAC | 51 |

| K219EintI1UP | CCTTGAGCGGGAGTATCCGCGCGCC | 50 |

| K219EintI1LO | GGCGCGCGGATACTCCCGCTCAAGG | 50 |

| K219IintI1UP | CCTTGAGCGGATATATCCGCGCGCC | 47 |

| K219IintI1LO | GGCGCGCGGATATATCCGCTCAAGG | 47 |

| K219WintI1UP | CCTTGAGCGGATGGATCCGCGCGCC | 50 |

| K219WintI1LO | GGCGCGCGGATCCATCCGCTCAAGG | 50 |

| W229RintI1UP | CATTCCTGGCCGCGGTTCTGGGTTTTTG | 48 |

| W229RintI1LO | CAAAAACCCAGAACCGCGGCCAGGAATG | 48 |

| W229GintI1UP | CATTCCTGGCCGGGGTTCTGGGTTTTTG | 48 |

| W229GintI1LO | CAAAAACCCAGAACCCCGGCCAGGAATG | 48 |

| F233LintI1UP | GTTCTGGGTTTTGGCGCAGCACACGC | 47 |

| F233LintI1LO | GCGTGTGCTGCGCCAAAACCCAGAAC | 47 |

| F233RintI1UP | GTTCTGGGTTCGTGCGCAGCACACGC | 49 |

| F233RintI1LO | GCGTGTGCTGCGCAGCAACCCAGAAC | 49 |

| F233YintI1UP | GTTCTGGGTTTATGCGCAGCACACGC | 45 |

| F233YintI1LO | GCGTGTGCTGCGCATAAACCCAGAAC | 45 |

| H277DintI1UP | CACGAAGCCGGCCACACCGGACACCCTCCGCCAC | 59 |

| H277DintI1LO | GTGGCGGAGGGTGTCCGGTGTGGCCGGCTTCGTG | 59 |

| H277LintI1UP | CACGAAGCCGGCCACACCGCTCACCCTCCGCCAC | 59 |

| H277LintI1LO | GTGGCGGAGGGTGAGCGGTGTGGCCGGCTTCGTG | 59 |

| H277RintI1UP | CACGAAGCCGGCCACACCGCGCACCCTCCGCCAC | 61 |

| H277RintI1LO | GTGGCGGAGGGTGCGCGGTGTGGCCGGCTTCGTG | 61 |

| H277YintI1UP | CACGAAGCCGGCCACACCGGACACCCTCCGCCAC | 58 |

| H277YintI1LO | GTGGCGGAGGGTGTACGGTGTGGCCGGCTTCGTG | 58 |

| G302AintI1UP | TCTGCTCGCCCATTCCGACGTCTCTACGACG | 52 |

| G302AintI1LO | TCGTAGAGACGTCGGAATGGGCGAGCAGAGC | 52 |

| G302RintI1UP | TCTGCTCCGCCATTCCGACGTCTCTACGACG | 52 |

| G302RintI1LO | TCGTAGAGACGTCGGAATGGCGGAGCAGAGC | 52 |

| pACYC184-5′ | TGTAGCACCTGAAGTCAGCC | 60 |

| pACYC184-3′ | ATACCCACGCCGAAACAAG | 60 |

TABLE 2.

Plasmids used in this study

| Plasmid | Characteristicsa | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| pLQ369 | 1,019-bp intI1 PCR fragment cloned in pMAL-c2 (Apr) | 13, 14 |

| pLQ428 | 2,133-bp Tn2424 fragment cloned in pACYC184 (Akr Cmr) | 14 |

| pLQ1101 | PLQ369 MBP-intI1(E121D) (Apr) | This study |

| pLQ1102 | PLQ369 MBP-intI1(E121K) (Apr) | This study |

| pLQ1103 | PLQ369 MBP-intI1(K171E) (Apr) | This study |

| pLQ1104 | PLQ369 MBP-intI1(K171I) (Apr) | This study |

| pLQ1105 | PLQ369 MBP-intI1(K171Q) (Apr) | This study |

| pLQ1106 | PLQ369 MBP-intI1(K171R) (Apr) | This study |

| pLQ1107 | PLQ369 MBP-intI1(K171V) (Apr) | This study |

| pLQ1108 | PLQ369 MBP-intI1(ΔALER215) (Apr) | This study |

| pLQ1109 | PLQ369 MBP-intI1(K219E) (Apr) | This study |

| pLQ1110 | PLQ369 MBP-intI1(K219I) (Apr) | This study |

| pLQ1111 | PLQ369 MBP-intI1(K219W) (Apr) | This study |

| pLQ1112 | PLQ369 MBP-intI1(W229G) (Apr) | This study |

| pLQ1113 | PLQ369 MBP-intI1(W229R) (Apr) | This study |

| pLQ1114 | PLQ369 MBP-intI1(F233L) (Apr) | This study |

| pLQ1115 | PLQ369 MBP-intI1(F233R) (Apr) | This study |

| pLQ1116 | PLQ369 MBP-intI1(F233Y) (Apr) | This study |

| pLQ1117 | PLQ369 MBP-intI1(H277D) (Apr) | This study |

| pLQ1118 | PLQ369 MBP-intI1(H277L) (Apr) | This study |

| pLQ1119 | PLQ369 MBP-intI1(H277R) (Apr) | This study |

| pLQ1120 | PLQ369 MBP-intI1(H277Y) (Apr) | This study |

| pLQ1121 | PLQ369 MBP-intI1(G302A) (Apr) | This study |

| pLQ1122 | PLQ369 MBP-intI1(G302R) (Apr) | This study |

Akr, Apr, and Cmr, resistance to amikacin, ampicillin, and chloramphenicol, respectively.

In vivo recombination.

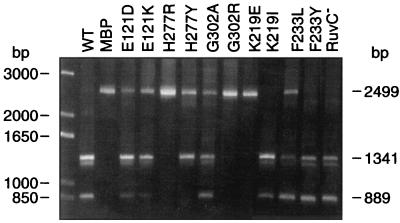

Mutant MBP-IntI1 clones (Table 2) were introduced by transformation into E. coli TB1 {F′ araΔ (lac-proAB) rpsL(Strr) [φ80dlacΔ(lacZ)M15] hsdR(rK− mK−)} containing pLQ428, a pACYC184-based plasmid which possesses two excisable cassettes (aacA1-ORFG and ORFH) (14). We also introduced by transformation the clones pLQ369 and pLQ428 into the RuvC mutant E. coli CS85 [thr-1 araC14 leuB6 Δ(gpt-proA)62 lacY1 tsx-33 qsr1− glnV44(AS) galK2(Oc) λ− Rac-O eda-51::Tn10 ruvC53 hisG4(Oc) frbD1 mgl-51 rpoS396(Am) rpsL31(Strr) kdgK51 xylA5 mtl-1 argE3(Oc) thi-1] from the E. coli Genetic Stock Center. Cells were grown at 37°C in Luria-Bertani medium and excision of the cassettes from pLQ428 was induced by using isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) as previously described (14). Plasmid DNA was then prepared and the capacity of mutant MBP-IntI proteins to excise the cassettes was determined by PCR. We used the pACYC184-5′ and pACYC184-3′ primers (Table 1) to detect the reduction in length of pLQ428 (14). Figure 3 shows examples of different kinds of results obtained with PCR on some plasmids expressing mutants of the MBP-IntI1 fusion protein in the in vivo recombination assay with the pLQ428 vector. There is a major 2,499-bp PCR fragment in several lanes containing DNA preparations from mutant clones. This band represents the pLQ428 clone without any cassette excision and is also observed in the negative control, which is the pMAL-c2 vector without any gene fused to malE. In the reaction containing the wild-type MBP-IntI1-expressing clone pLQ369 in E. coli TB1 and in the E. coli ruvC mutant strain CS85, this 2,499-bp product was not obtained, indicating that the wild-type fusion protein is very efficient in site-specific recombination in these strains and that RuvC is not required to complete the reaction. In these PCRs, we observed two major bands, of 1,341 and 889 bp (Fig. 3). The 1,341-bp product represents a pLQ428 clone which has lost the aacA1-ORFG cassette and the 889-bp product represents a pLQ428 clone which has lost both the aacA1-ORFG and ORFH cassettes (14). One or both of the 1,341- and 889-bp PCR products are also observed, with variable intensity, in the reaction containing the mutant clones pLQ1101(E121D), pLQ1102(E121K), pLQ1103 (K171E), pLQ1104(K171I), pLQ1105(K171Q), pLQ1106 (K171R), pLQ1107(K171V), pLQ1110(K219I), pLQ1114 (F233L), pLQ1115(F233R), pLQ1116(F233Y), pLQ1120 (H277Y), and pLQ1121(G302A). These mutant proteins are equally efficient as or less efficient than the wild-type protein for the recombination activity, as seen by the presence and intensity of the PCR products. Some are able to excise only the first cassette (aacA1-ORFG), since the 1,341-bp product can be seen on the agarose gel and the 889-bp product is absent; others are able to excise both cassettes since the 889-bp product, but not the 1,341-bp product, is seen. Mutants pLQ1108 (ΔALER215), pLQ1109(K219E), pLQ1111(K219W), pLQ1112(W229G), pLQ1113(W229R), pLQ1117(H277D), pLQ1118(H277L), pLQ1119(H277R), and pLQ1122(G302R) did not show any recombinational activity and only the 2,499-bp PCR product is seen on the gel. As previously described (14), we were not able to detect a PCR product of 2,047 bp, corresponding to the rare event of excision of the ORFH cassette alone. We can see another apparent PCR product of 1,200 bp in the reactions containing active proteins. This PCR product has been sequenced and corresponds to an annealing of a DNA strand from the 1,341-bp product with a DNA strand from the 889-bp product.

FIG. 3.

Electrophoresis of PCR products obtained with the pACYC184 primers and 100 ng of DNA preparation from overexpressed cultures on a 1% agarose gel. Lane 1, 1-kb-plus DNA ladder (Life Technologies); lane 2, DNA preparation of pLQ428-pLQ369 (wild type); lane 3, pLQ428-pMAL-c2 (MBP); lane 4, pLQ428-pLQ1101(E121D); lane 5, pLQ428-pLQ1102 (E121K); lane 6, pLQ428-pLQ1119 (H277R); lane 7, pLQ428-pLQ1120 (H277Y); lane 8, pLQ428-pLQ1121 (G302A); lane 9, pLQ428-pLQ1122 (G302R); lane 10, pLQ428-pLQ1109 (K219E); lane 11, pLQ428-pLQ1110 (K219I); lane 12, pLQ428-pLQ1114 (F233L); lane 13, pLQ428-pLQ1116 (F233Y); lane 14, pLQ428-pLQ369 (wild type) in a RuvC− strain.

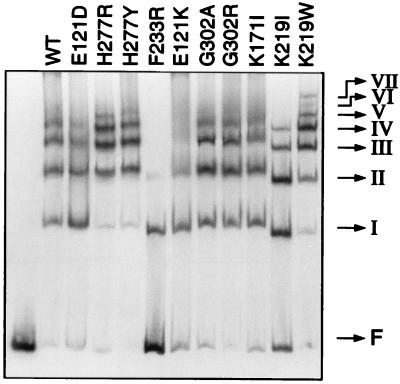

In vitro substrate binding.

We used the purified fusion proteins and a gel retardation assay with the complete attI1 site of the integron to determine the binding properties of each mutant at the recombination site. MBP-IntI fusion proteins were overproduced and purified on amylose resin (New England BioLabs) as previously described (14). Binding reactions were done with a labeled attI1 site DNA fragment incubated with different concentrations of MBP-IntI1 as previously described (14). The wild-type fusion protein and native IntI1 were shown to lead to the same four distinct complexes with this DNA substrate (13). These complexes represent the binding of four IntI1 molecules to four different sites in the attI1 site. The binding specificity of the IntI1 molecules has been previously described (13). Figure 4 shows examples of different kinds of results obtained with some mutants of the MBP-IntI1 fusion protein in the gel retardation experiment with the attI1 site. We observed that mutants W229G and H277D have completely lost the ability to bind to the attI1 site, as no complexes are seen in the gel retardation assay. Mutants E121D, K171E, K171I, K171R, K171V, ΔALER215, K219I, F233Y, H277L, G302A, and G302R are fully active in binding activity and give a pattern of complexes similar to that of the wild-type fusion protein. Mutants E121K, K171Q, W229R, F233L, and F233R show a lower affinity for the attI1 site, with only some complexes seen in the gel retardation experiment. Mutants K219E, K219W, H277R, and H277Y seem to have more affinity than wild-type IntI1 for the recombination site, with as many as seven complexes formed with the attI1 site.

FIG. 4.

Gel retardation experiment with mutant MBP-IntI fusion proteins purified from E. coli TB1, on the complete attI1 site of the In2 integron (from nucleotide −96 to +71, relative to the G residue of the core site at position 0). A purified labeled fragment was incubated with a 200 nM concentration of mutant fusion proteins. Free DNA (F) and protein-DNA complexes (I to VII) were separated on 4% polyacrylamide gels and are indicated by arrows. Lane 1, free DNA; lane 2, wild-type MBP-IntI1 protein; lane 3, MBP-IntI1 (E121D) mutant; lane 4, MBP-IntI1 (H277R) mutant; lane 5, MBP-IntI1 (H277Y) mutant; lane 6, MBP-IntI1 (F233R) mutant; lane 7, MBP-IntI1 (E121K) mutant; lane 8, MBP-IntI1 (G302A) mutant; lane 9, MBP-IntI1 (G302R) mutant; lane 10, MBP-IntI1 (K171I) mutant; lane 11, MBP-IntI1 (K219I) mutant; lane 12, MBP-IntI1 (K219W) mutant.

Relationships with other tyrosine recombinases.

The conserved lysine residue K171 has been proven to be a fifth essential catalytic residue of tyrosine recombinases and eukaryotic type IB topoisomerases (4). In crystal structures of λ Int c170, HP1 Int, XerD, and Cre, this conserved lysine delineates one edge of the catalytic pocket (27). A mutation of the XerD recombinase at this position (K172A) conferred a severe defect in recombination at the dif site (4). This lysine seems to be in close contact with the substrates and may influence the reactivity of the phosphotyrosine intermediates formed during recombination reactions. Mutants K171E, K171R, K171I, and K171V were found to bind the recombination site similarly to the wild-type protein but showed an altered recombinational activity, excising both cassettes and not the first cassette alone as the wild-type protein does. Mutant K171Q was only able to form two complexes with the attI1 site and showed a weak recombination activity. These effects are probably due to the properties of the substitute residues. Glutamine contains a carboxyl group and might change the conformation of the protein and inhibit its binding capacity. The fact that only two cassettes are excised by those mutants might indicate that this residue is implicated in the recognition of the different attC sites and the mutant proteins were unable to recognize the aacA1-ORFG attC site, thus abolishing the excision of the first cassette alone. The wild-type protein recognizes this site efficiently.

The H277 residue is one of the conserved tetrad (RHRY) of residues and is located in the box II motif. Some possible roles of this residue, along with the two conserved arginines, are orientation of the DNA in the appropriate conformation for nucleophilic attack, stabilizing a pentacoordinate transition state at the scissile phosphate, or participating in shuttling protons (21). Mutant H277D showed no affinity and mutant H277L showed an affinity similar to that of the wild-type fusion protein for the attI1 site. These mutants showed no recombination activity. Conversely, mutants H277R and H277Y showed a stronger affinity for the recombination site than the wild-type protein as seen by the stronger intensity of complexes 3 and 4, the presence of a fifth complex, and the near absence of complex 1, meaning that few attI1 sites had only one monomer bound. Only mutant H277Y showed a recombination activity, and it was able to excise only the aacA1-ORFG cassette. The substituted tyrosine residue has a different charge but unlike other substitutions made, it possesses an aromatic ring that could give similar steric properties to the imidazole ring of the histidine.

The conserved glycine (G302) is located in the box II motif in the consensus sequence LLGH and is present in more than 80% of prokaryotic tyrosine recombinases. The neighboring histidine (H303) is also highly conserved in prokaryotic enzymes. In HP1 integrase, this histidine is directed towards the active site and makes a hydrogen bond with a sulfate ion which is believed to represent the location of a DNA phosphate (8). In the Cre recombinase-DNA complex, the equivalent tryptophan (W315) is part of the catalytic pocket with a hydrogen bond to the second nonbridging oxygen atom of the scissile phosphate (27). A G332R mutant of λ Int and a G328R mutant of Flp both retain core binding activity but cannot carry out recombination (19, 29, 42). Binding activity of IntI1 G302A and G302R mutants is not affected, but only G302A is active for recombination and can excise the first cassette or both cassettes of the pLQ428 clone, but with a lower activity than the wild-type fusion protein. The recombination activity of the G302A mutant can be explained by the similarity between these residues. Therefore, this conserved glycine may be implicated in the recombination activity of IntI1 but it is more likely that the G302R mutant disturbs the correct placement of the conserved H303 that is itself implicated in the recombination mechanism.

The conserved glutamate residue (E121) is located in the patch I motif in the consensus sequence LT-EEV-LL (27). In the crystal structure of λ Int c170, this conserved residue (E184) protrudes from the surface of the protein away from the active site (22) and a mutation of the equivalent glutamate of the phage P2 Int (E169K) renders it defective for recombination (27). However, for IntI1, this residue seems to play a role in DNA binding rather than in recombination. We found that IntI1 recombinase in which this conserved glutamate has been changed to aspartate (D) can bind to the attI1 site and excise cassettes with almost the same efficiency as the wild-type fusion protein. However, when this conserved residue is changed to a lysine (K), the fusion protein has less affinity for the attI1site, with only two complexes seen in the gel retardation experiment. This mutant showed a reduced recombinational activity compared to the wild-type protein, with the binding of only two monomers to the recombination site. E121D is a conservative mutation and does not affect the protein activity, while the E121K mutation causes a change in the charge (from negative to positive) and in the side chain size of the residue. Those changes affect the affinity of the protein for the attI1 site, which in turn affects the recombination.

The patch III motif is a hydrophobic core region, preceded by acidic residues and followed by polar residues, deeply buried and likely important for the correct folding of the protein and described as the consensus sequence (DE)-(F,Y,W,V,L,I,A)3–6(ST) (27). Residue W229 is located in the patch III motif but the W is mainly conserved among integron integrases, while other tyrosine recombinases generally possess an acidic residue at this position. Fusion protein mutants W229G and W229R were not able to excise the cassettes and only W229R showed any affinity for the attI1 site, forming one complex with it. This hydrophobic residue may play a role in the recognition of the recombination site or in stabilizing the native folds of the protein. The weak binding activity observed with W229R can be explained by the smaller conformational change caused by the substituted arginine that is larger than the glycine residue. The positive charge of the substituted arginine may help in the binding of the DNA, whereas the uncharged glycine does not. The F233 residue is also located in the patch III motif and is present in all integron integrases but not in other tyrosine recombinases, in which it is generally replaced by various other hydrophobic residues (27). The fusion protein mutants F233L and F233R showed weak activity in binding (two and one complexes formed, respectively) and recombination, while mutant F233Y showed a wild-type phenotype for those activities. This phenylalanine may be implicated in substrate recognition but also in stabilizing the native folds of the protein since only one or two complexes are formed with the mutants F233L and F233R; this lower affinity can explain the weak recombination activity of these mutants. The wild-type phenotype of the F233Y mutant can be explained by the similarity between these two residues that differ only by a hydroxyl group.

Mutations in the IntI1 extra domain.

ALER is a highly conserved sequence located in the additional domain, particular to integron integrases, near the patch III motif. We made a complete deletion of this sequence and the resulting fusion protein MBP-ΔALER215 showed a wild-type DNA binding activity but was deficient in recombination. This sequence does not seem to be implicated in the recognition of the recombination site attI1 but may play a role in positioning and stabilizing the active site or in recognition and binding to the diverse attC sites. K219 is located just after the ALER sequence and is conserved among all identified integron integrases. Fusion protein mutants K219E and K219W showed a stronger affinity to the attI1 site, forming up to seven complexes in the gel retardation assay, but these mutants failed to show any recombination activity. The K219I mutant was effective in binding to the attI1site and excising either the first cassette or both cassettes from the pLQ428 clone. This residue may play a role in the recognition of the recombination site, since it is positively charged and mutants K219E and K219W showed a greater affinity for it. The lack of recombination for these mutants may be due to the presence of too many monomers, resulting in interference and preventing the cleavage of the DNA. Alternatively, the substituted residues may cause a major change in the protein conformation and disturb the active site when the basic lysine is replaced by an acidic glutamate or an aromatic tryptophan. It is surprising that mutant K219I is still able to bind to the recombination site and to excise the cassettes since the amino acid substitution involves a change from a basic residue to a hydrophobic residue.

Recombination assay in a RuvC mutant strain.

The crossover point of the integron site-specific recombination is located between the G and the first T in the core site GTTRRRY, but it is not yet clear whether the cleavage occurs at the same place on both DNA strands or whether there is a staggered cleavage. Because of the sequence differences between attI and the various attC sites, there appears to be a blunt crossing over at this site. Some authors hypothesized that only one strand (the bottom strand) is cleaved by the integrase and the resulting Holliday junction is resolved by a cellular enzyme like RuvC (38). We introduced the pLQ369 clone, coding for the MBP-IntI1 fusion protein, and the pLQ428 clone, containing two excisable cassettes (aacA1-ORFG and ORFH) into the E. coli ruvC mutant strain. The results showed that there is a high level of recombination in this strain (Fig. 3), so the cellular enzyme RuvC is not responsible for the cleavage of the second DNA strand in the recombination reaction. We believe that the cleavage is entirely mediated by the integrase and is staggered, with the bottom cleavage occurring between the C and the first A (corresponding to the G and the first T of the upper strand) and the upper cleavage occurring seven nucleotides upstream after two A's, giving the general binding motif TAAN7TTR on attI sites for all integron integrases. This cleavage model is similar to that observed for the XerC-XerD recombinases for which the binding motif is TAAN6–8TTR, with the cleavage occurring on either side of the central region immediately 3′ of an AA dinucleotide on each strand (2). Studies of IntI1 binding sites have shown that this enzyme uses a recognition pattern similar to that used by XerC-XerD (13) and the C-terminal part of XerD shares about 50% similarity with the C-terminal part of IntI1.

Table 3 summarizes the results obtained with the MBP-IntI1 mutants of this study in in vivo recombination and in vitro DNA binding and shows a comparison of the results obtained with the mutants of IntI1 conserved residues and equivalent mutants of other tyrosine recombinases. These results of mutational analysis show that many conserved residues like E121, K171, W229, F233, H277, and G302 are essential for IntI1 and other tyrosine recombinases in protein folding, DNA binding, or the recombination reaction. Even if they do not share extensive sequence similarity, these enzymes seem to possess a similar active site and catalyze recombination by the same mechanism (8, 10, 12, 14, 27). Some additional residues of IntI1 (ALER215, K219) were proven to be essential for its activity. Since these residues are present in almost all integron integrases, we believe that these enzymes have a specific additional domain that differs from other tyrosine recombinases. This unique structure may be essential for those enzymes that can recognize and act on diverse recombination sites (attI and multiple attCs), as well as serving as its own accessory protein.

TABLE 3.

Mutational analysis of IntI1 residues conserved among tyrosine recombinases, residues conserved among integron integrases, and corresponding residues of other tyrosine recombinases

| IntI1 mutation | DNA bindinga | Recombination | Comparable mutation | DNA binding | Recombination | Reference(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conserved catalytic residues | ||||||

| K171E | ++ | + | ||||

| K171I | ++ | + | ||||

| K171Q | + | + | ||||

| K171R | ++ | + | XerD K172W | NDb | − | 4 |

| K171V | ++ | + | XerD K172A | ++ | + | 4 |

| H277D | − | − | ||||

| H277L | ++ | − | λ Int H308L | + | − | 18, 24 |

| H277R | +++ | − | ||||

| H277Y | +++ | + | Cre H289Y | ++ | + | 41 |

| G302A | ++ | + | ||||

| G302R | ++ | − | λ Int G332R | ++ | − | 19, 36, 42 |

| Noncatalytic residues | ||||||

| E121D | ++ | ++ | ||||

| E121K | + | + | P2 Int E169K | NDb | − | 27 |

| W229G | − | − | ||||

| W229R | + | − | ||||

| F233L | + | + | ||||

| F233R | + | + | ||||

| F233Y | ++ | + | ||||

| Additional residues | ||||||

| ΔALER215 | ++ | − | ||||

| K219E | +++ | − | ||||

| K219I | ++ | ++ | ||||

| K219W | +++ | − |

−, negative; +, weaker than the wild-type protein; ++, wild-type efficiency; +++, stronger than the wild-type protein.

ND, not determined.

Acknowledgments

We thank Simone Nunes-Duby and Michael N. Gopaul for helpful discussions. We thank TIGR for partial genomic sequences of Geobacter sulfurreducens, Shewanella putrefaciens, and Treponema denticola and the Joint Genome Initiative (JGI) for the partial genome sequence of Nitrosomonas europaea.

This work was supported by grant MT-13564 from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) to P.H.R. N.M. held a fellowship from CIHR.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bissonnette L, Roy P H. Characterization of In0 of Pseudomonas aeruginosa plasmid pVS1, an ancestor of integrons of multiresistance plasmids and transposons of gram-negative bacteria. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:1248–1257. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.4.1248-1257.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blakely G W, Sherratt D J. Interactions of the site-specific recombinases XerC and XerD with the recombination site dif. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:5613–5620. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.25.5613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brown H J, Stokes H W, Hall R M. The integrons In0, In2, and In5 are defective transposon derivatives. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:4429–4437. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.15.4429-4437.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cao Y, Hayes F. A newly identified, essential catalytic residue in a critical secondary structure element in the integrase family of site-specific recombinases is conserved in a similar element in eucaryotic type IB topoisomerases. J Mol Biol. 1999;289:517–527. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.2793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen Y, Narendra U, Iype L E, Cox M M, Rice P A. Crystal structure of a Flp recombinase-Holliday junction complex: assembly of an active oligomer by helix swapping. Mol Cell. 2000;6:885–897. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Collis C M, Grammaticopoulos G, Briton J, Stokes H W, Hall R M. Site-specific insertion of gene cassettes into integrons. Mol Microbiol. 1993;9:41–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01667.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Collis C M, Hall R M. Expression of antibiotic resistance genes in the integrated cassettes of integrons. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1995;39:155–162. doi: 10.1128/aac.39.1.155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Esposito D, Scocca J J. The integrase family of tyrosine recombinases: evolution of a conserved active site domain. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:3605–3614. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.18.3605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Francia M V, de la Cruz F, Garcia Lobo J M. Secondary-sites for integration mediated by the Tn21 integrase. Mol Microbiol. 1993;10:823–828. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb00952.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gopaul D N, Van Duyne G D. Structure and mechanism in site-specific recombination. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 1999;9:14–20. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(99)80003-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gopaul D N, Guo F, Van Duyne G D. Structure of the Holliday junction intermediate in Cre-loxP site-specific recombination. EMBO J. 1998;17:4175–4187. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.14.4175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grainge I, Jayaram M. The integrase family of recombinase: organization and function of the active site. Mol Microbiol. 1999;33:449–456. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01493.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gravel A, Fournier B, Roy P H. DNA complexes obtained with the integron integrase IntI1 at the attI1 site. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998;26:4347–4355. doi: 10.1093/nar/26.19.4347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gravel A, Messier N, Roy P H. Point mutations in the integron integrase IntI1 that affect recombination and/or substrate recognition. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:5437–5442. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.20.5437-5442.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guo F, Gopaul D N, Van Duyne G D. Asymmetric DNA bending in the Cre-loxP site-specific recombination synapse. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:7143–7148. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.13.7143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guo F, Gopaul D N, van Duyne G D. Structure of Cre recombinase complexed with DNA in a site-specific recombination synapse. Nature. 1997;389:40–46. doi: 10.1038/37925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hall R M, Brookes D E, Stokes H W. Site-specific insertion of genes into integrons: role of the 59-base element and determination of the recombination cross-over point. Mol Microbiol. 1991;5:1941–1959. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1991.tb00817.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Han Y W, Gumport R I, Gardner J F. Complementation of bacteriophage lambda integrase mutants: evidence for an intersubunit active site. EMBO J. 1993;12:4577–4584. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb06146.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Han Y W, Gumport R I, Gardner J F. Mapping the functional domains of bacteriophage lambda integrase protein. J Mol Biol. 1994;235:908–925. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1994.1048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hansson K, Sköld O, Sundström L. Non-palindromic attl sites of integrons are capable of site-specific recombination with one another and with secondary targets. Mol Microbiol. 1997;26:441–453. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.5401964.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hickman A B, Waninger S, Scocca J J, Dyda F. Molecular organization in site-specific recombination: the catalytic domain of bacteriophage HP1 integrase at 2.7 Å resolution. Cell. 1997;89:227–237. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80202-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kwon H J, Tirumalai R, Landy A, Ellenberger T. Flexibility in DNA recombination: structure of the lambda integrase catalytic core. Science. 1997;276:126–131. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5309.126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Levesque C, Brassard S, Lapointe J, Roy P H. Diversity and relative strength of tandem promoters for the antibiotic-resistance genes of several integrons. Gene. 1994;142:49–54. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(94)90353-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.MacWilliams M P, Gumport R I, Gardner J F. Genetic analysis of the bacteriophage lambda attL nucleoprotein complex. Genetics. 1996;143:1069–1079. doi: 10.1093/genetics/143.3.1069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mazel D, Dychinco B, Webb V A, Davies J. A distinctive class of integron in the Vibrio cholerae genome. Science. 1998;280:605–608. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5363.605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nield B S, Holmes A J, Gillings M R, Recchia G D, Mabbutt B C, Nevalainen K M, Stokes H W. Recovery of new integron classes from environmental DNA. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2001;195:59–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2001.tb10498.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nunes-Düby S E, Kwon H J, Tirumalai R S, Ellenberger T, Landy A. Similarities and differences among 105 members of the Int family of site-specific recombinases. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998;26:391–406. doi: 10.1093/nar/26.2.391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ouellette M, Roy P H. Homology of ORFs from Tn2603 and from R46 to site-specific recombinases. Nucleic Acids Res. 1987;15:10055. doi: 10.1093/nar/15.23.10055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pan G, Luetke K, Sadowski P D. Mechanism of cleavage and ligation by FLP recombinase: classification of mutations in FLP protein by in vitro complementation analysis. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:3167–3175. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.6.3167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Paulsen I T, Littlejohn T G, Radstrom P, Sundström L, Sköld O, Swedberg G, Skurray R A. The 3′ conserved segment of integrons contains a gene associated with multidrug resistance to antiseptics and disinfectants. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1993;37:761–768. doi: 10.1128/aac.37.4.761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Radström P, Swedberg G, Sköld O. Genetic analyses of sulfonamide resistance and its dissemination in gram-negative bacteria illustrate new aspects of R plasmid evolution. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1991;35:1840–1848. doi: 10.1128/aac.35.9.1840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Recchia G D, Hall R M. Gene cassettes: a new class of mobile element. Microbiology. 1995;141(Pt. 12):3015–3027. doi: 10.1099/13500872-141-12-3015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Recchia G D, Hall R M. Plasmid evolution by acquisition of mobile gene cassettes: plasmid pIE723 contains the aadB gene cassette precisely inserted at a secondary site in the IncQ plasmid RSF1010. Mol Microbiol. 1995;15:179–187. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.tb02232.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Recchia G D, Stokes H W, Hall R M. Characterisation of specific and secondary recombination sites recognised by the integron DNA integrase. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:2071–2078. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.11.2071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rowe-Magnus D A, Guerout A M, Ploncard P, Dychinco B, Davies J, Mazel D. The evolutionary history of chromosomal super-integrons provides an ancestry for multiresistant integrons. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:652–657. doi: 10.1073/pnas.98.2.652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Segall A M, Nash H A. Architectural flexibility in lambda site-specific recombination: three alternate conformations channel the attL site into three distinct pathways. Genes Cells. 1996;1:453–463. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2443.1996.d01-254.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stokes H W, Hall R M. A novel family of potentially mobile DNA elements encoding site-specific gene-integration functions: integrons. Mol Microbiol. 1989;3:1669–1683. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1989.tb00153.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stokes H W, O'Gorman D B, Recchia G D, Parsekhian M, Hall R M. Structure and function of 59-base element recombination sites associated with mobile gene cassettes. Mol Microbiol. 1997;26:731–745. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.6091980.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Subramanya H S, Arciszewska L K, Baker R A, Bird L E, Sherratt D J, Wigley D B. Crystal structure of the site-specific recombinase, XerD. EMBO J. 1997;16:5178–5187. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.17.5178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Van Duyne G D. A structural view of Cre-loxp site-specific recombination. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct. 2001;30:87–104. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.30.1.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wierzbicki A, Kendall M, Abremski K, Hoess R. A mutational analysis of the bacteriophage P1 recombinase Cre. J Mol Biol. 1987;195:785–794. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(87)90484-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wu Z, Gumport R I, Gardner J F. Genetic analysis of second-site revertants of bacteriophage lambda integrase mutants. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:4030–4038. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.12.4030-4038.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]