Abstract

Monosodium glutamate (MSG) is commonly used worldwide as a food flavour enhancer by the food industry. The current study investigated the in vivo toxic effects of MSG on the uterus in adult female Sprague Dawley rats and in vitro using MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 cells, computational toxicity and molecular docking. The average levels of progesterone and oestrogen in the MSG-treated animals significantly altered. Besides, the average uterine lumen area (μm2) was smaller than the control group. MSG showed high-affinity binding to acetylcholine receptors and disrupted the normal nerve signal with a predicted LD50 of 4500 mg/kg. MSG also demonstrated good binding affinity to human oestrogen receptors beta and some other proteins that have an oxidative stress role in the female reproductive organs. Therefore, a precaution should be taken when utilising this compound, especially for females under the risk factor of hormonal abnormality.

Keywords: Monosodium glutamate, Progesterone, Oestrogen, Toxicity, Molecular docking

Monosodium glutamate; Progesterone; Oestrogen; Toxicity; Molecular docking.

1. Introduction

Monosodium glutamate (MSG) is a controversial food additive that is widely used as a flavour enhancer in the food processing industry, restaurants, and institutional service. Chemically, MSG is a bright, and white powder similar to salt. It is manufactured by fermenting starch, sugar cane, or molasses followed by purifying and drying [1]. According to IHS Markit’s Chemical Economics Handbook, the global consumption of MSG in 2019 was nearly 3.9 million metric tons (MMT) and its market size was USD 5143.6 million in 2021. Furthermore, by 2026, the MSG market is expected to register a 6.2% compound annual growth rate (CAGR) in terms of revenue, reaching a global market size of USD 6177.7 million [2].

Several studies provided evidence of the toxic effects of MSG in humans [3, 4] and experimental animals [3, 5], which raised the increasing interest in MSG consumption [3]. The reported side effects of MSG included but were not limited to dizziness, headaches, numbness, weakness, flushing, and sweating [4]. Moreover, more serious side effects were reported, such as atopic dermatitis, asthma, urticaria, ventricular arrhythmia, and neuropathy [6]. In addition, there has been increasing interest in exploring the effect of MSG on the reproductive organs. Several studies have reported the toxic effects of MSG on male reproductive organs in animals by causing oligozoospermia, abnormal sperm morphology, and testicular haemorrhage [7, 8, 9, 10, 11].

Endocrine disruptors such as organic compounds, pesticides, phthalates, bisphenol A, and heavy metals may cause impaired reproductive systems, such as poor semen quality and quantity in males, and some gynaecological medical conditions in females, such as endometriosis, benign tumours and infections of reproductive organs [12, 13, 14, 15]. Uterine tissues of humans and rodents are similar in essential characteristics. Measurement of uterine toxicity could be done by assessing many parameters, including an alteration in uterine weight, hormonal levels and histological examination of lumen area, length of stroma and myometrium [16, 17, 18].

In the past decade, fear had increased due to the adverse effects and toxicity of MSG. In addition, there is limited literature about the hormonal and histological effects of MSG on the uterus. Therefore, this study was conducted to assess the in vivo toxic effects of MSG on the uterus in adult female Sprague Dawley rats and on oestrogen receptor-positive (MCF-7) and oestrogen receptor-negative (MDA-MB-231) breast cancer cells as well as to elucidate the possible mechanism of toxicity using computational toxicity and molecular docking.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. In vivo animal experiment

Twelve virgins sexually matured Sprague Dawley female rats (6 animals per group), 10–14 weeks old and weighing 237 ± 34 g were obtained from the Animal Research and Service Centre of Qassim University (QU), Qassim, Saudi Arabia. The animal experiment was done according to the National Research Council's Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and the protocol of the animal experiment was approved by the committee of research ethics at Qassim University with ethics reference number “20-02-01”. The animals were housed in a temperature-controlled room (25 ± 2 °C) with a 12 h light/dark cycle. Standard chow diet (1st Milling Company, KSA) and reverse osmosis (RO) water were provided ad libitum.

Only animals with a regular oestrous cycle (EC) were included in this study. Before the experiment started, two normal ECs were recorded according to the non-staining method described by the previous study [48]. Briefly, daily vaginal fluid obtained using a micropipette filled with 10 μl normal saline and viewed under a light microscope at ×10 magnification was performed to determine the phase of the oestrus cycle. The EC of rodents usually has four phases, namely proestrus, oestrus, metestrus and diestrus and lasts for 4–5 days [49]. Proestrus phase can be recognized by the predominance of epithelial cells, oestrus characterized by cornified cells, diestrus indicated by the predominance of leukocytes, and metestrus characterized by the presence of an equal number of epithelial, leukocytes, and cornified cells [50]. A total of 12 female SD rats were randomly and equally divided into two groups. The first group was assigned as a control group and administered 10 ml/kg of distilled water (DW), and the second group was administered daily with MSG (2 g/kg) via oral gavage for 14 days [42]. The selected dose of MSG (2 g/kg) was chosen based on the LD50 of MSG in the rat model as reported previously [44] and a pilot study of MSG effects on ECs regularity which caused a marked increase in the diestrus phase. Vaginal lavage was performed on the control and treated animals. At the end of the experiment, each animal was anaesthetised with 75 mg/kg ketamine and 10 mg/kg xylazine. The blood samples were collected via cardiac puncture at the oestrus phase for serum progesterone and oestrogen analysis. The animals were euthanized by cervical dislocation, and the uterine tissues were isolated in the oestrus phase [29]. After recording the relative weight of each wet uterine, it was fixed in 10% buffered formalin for histological evaluation.

2.2. Histological examination of the uterus

Each Fixed uterine tissue was subjected to dehydration processing and embedded in paraffin wax. The prepared paraffin blocks were sent to a Specialized Medical lab for sectioning and stained with hematoxylin and eosin. The images of uterine sections were taken using a light microscope attached to a digital camera (Leica DM750). Microscopically, three major features were assessed using Image J software, namely, the lumen area, which is the inside space of the tubular structure of the uterus, the stromal uterus, which is a deep layer of the endometrium, and the myometrium layer, which is the structural wall of the uterus and composed primarily of smooth muscle. Six uterine sections from each animal were evaluated, and the mean relative value to the respective control was calculated.

2.3. Female sex hormone levels measurement

At the end of the experiment, each animal with the oestrus phase was anaesthetised. The blood sample was collected in a non-heparinised test tube. The serum was separated by centrifuging (5000 rpm for 15 min) and kept at -80 °C until analysis. The serum oestrogen and progesterone levels were measured using the chemiluminescence immunoassay (Beckman coulter Access II, USA). The relative value of hormone was calculated according to the following formula:

The relative value of hormone = measured value for treated animal/average of control ∗100.

2.4. MTT cytotoxicity assay

To grow cells, media supplemented with 10 % fetal bovine serum (FBS) was used. MTT assay was conducted by seeding the oestrogen-positive MCF-7 and the oestrogen-negative MDA-MB-231 cells (5 × 103 cells/well) in 96 well plates. After overnight incubation in a CO2 incubator at 37 °C, cells were treated with a 2-fold serial range of concentrations of MSG (100–0.78 μg/ml) followed by incubation for 24, 48, and 72 h. After that, MTT (5 mg/ml) was added to each well and re-incubated for 4 h. Formazan crystals were dissolved in DMSO, and optical density was recorded using a microplate reader at 570 nm. The cell viability percentage was estimated in comparison to the control [51]. The assay was carried out in triplicates measurement and at least three independent experiments.

2.5. Exploring the computational toxicity of MSG

Computational chemistry was used to explore the pharmacokinetic properties of MSG. Then, to screen the toxic effects of the MSG computationally, acute toxicity was predicted using the ProTox-II tool based on many computational approaches, including molecular similarity, fragment propensities, and machine-learning [52]. Furthermore, the iSafeRat® tool was used to provide a reliable and accurate computational analysis to replace experimental OECD guideline studies [53]. Electrophilicity index (ω) was calculated (equation No. 1) using the molecular and quantum descriptors, which were calculated using PaDEL-Descriptor and Spartan (v.8), respectively [54, 55].

| (1) |

where (μ) is the chemical potential, (η) hardness, (Ι) ion energy, and (A) represents the electron affinity energies of the highest occupied orbital. HOMO and LUMO were calculated using the ωB97X-D model with a Basis set of 6–31G∗. The ADF package (SCM, V. 2021.102) was used to calculate the local phylicity (equation No. 2) at any atom (k) based on the Hirshfeld model of the Fukui function () [56].

| (2) |

where α represents local philic quantities describing nucleophilic (), and electrophilic () radical attacks. The value was calculated on the carbon atom with maximum and the were calculated on nitrogen atom with maximum .

Finally, the quantum dissimilarity (Eq. (3)) was calculated to check the effects of both the electron acceptor and donor on cellular toxicity [57].

| (3) |

2.6. Molecular docking

AutoDock Vina (v. 1.1.2) was used to blindly dock MSG with several selected targets [58]. Besides validating the findings was carried out using commercial inhibitors. The 3D structure of the ligands was downloaded from the PubChem database (https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) and the targeted proteins were downloaded from the Protein data bank (https://www.rcsb.org/). The proteins were cleaned and then optimized by removing the solvent, besides adding hydrogen atoms and charges. Since the ligand is flexible and proteins are rigid, then semi-flexible docking analysis was used (3000 steps).

2.7. Statistical analysis

The in vivo data was represented as the mean relative value to the respective control ±SEM (n = 6) and analysed using the Student’s t-test. The in vitro data were analysed using two-way ANOVA and the results were expressed as mean ± SD. GraphPad Prism 8.4 software was used to perform the analysis. P-values ≤ 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Effect of MSG on uterine tissue

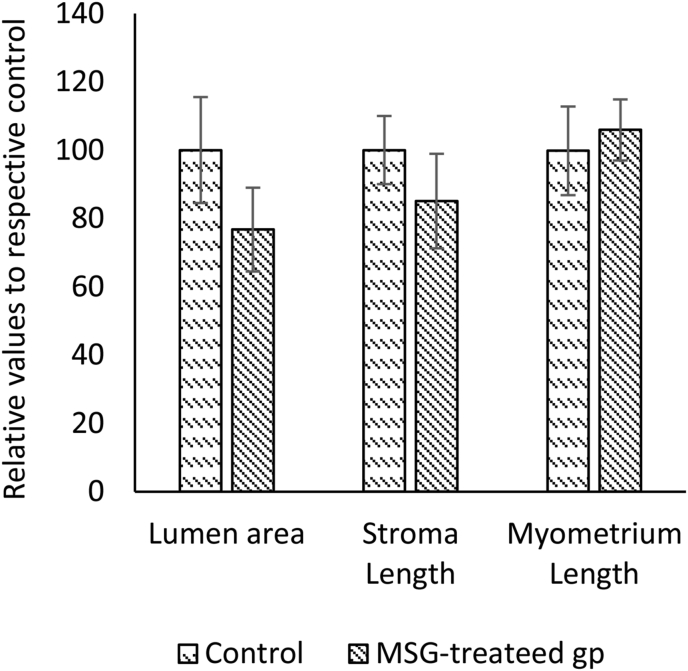

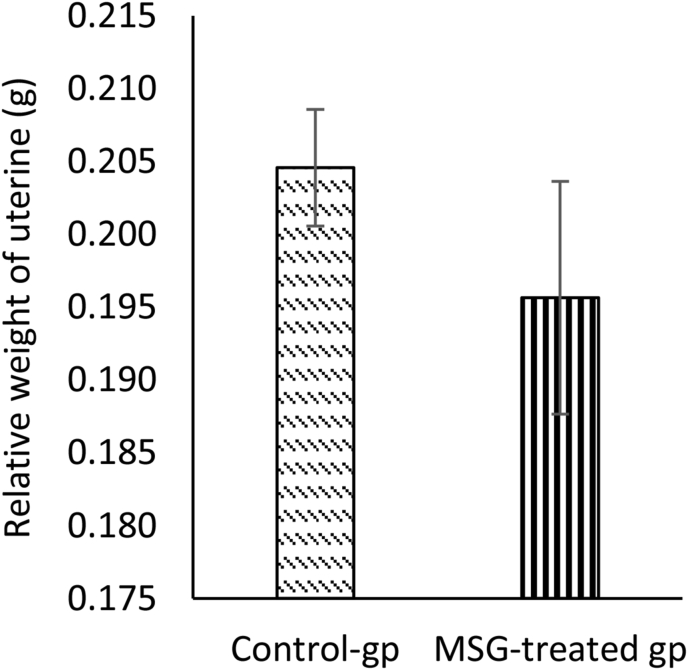

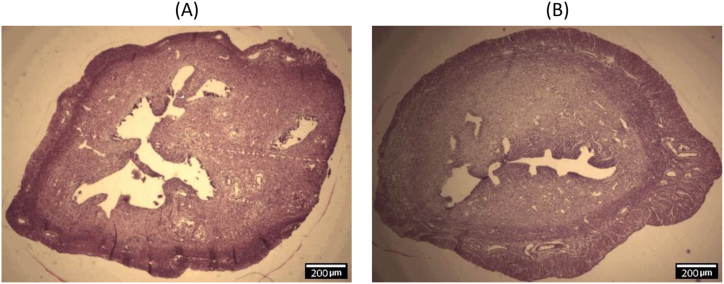

The effect of oral administration of MSG (2 g/kg) on the uterus was evaluated in rats. In the MSG-treated group, the means of the relative lumen area (77.2 ± 12.48 μm2) and length of stroma (85.5 ± 14.23 μm) were smaller than the control group (100.3 ± 16.01 μm2 and 100.2 ± 10.63 μm, respectively), while the mean of the relative length of the myometrium (106.3 ± 9.19 μm) was slightly higher than control (100.1 ± 13.32 μm) (Figure 1). The mean relative weight of the uterine weight in the MSG-treated group was less than the control group but the difference was not statistically significant (Figure 2). Histological findings of the uterus showed that The Lumen area and length of stroma were higher in the control group than in the treated group, while the length of myometrium was higher in the treated group. Figure 3 shows representative photomicrographs of rat uterine sections obtained from MSG-treated rats and control.

Figure 1.

Effect of monosodium glutamate (MSG) oral administration on the morphological parameters of uterus during oestrus phase in female rats. Comparing the mean of lumen area (μm2), stroma length (μm) and myometrium length (μm) in uterine tissues between control and treated groups. Image J software was used for measurement. Data were presented as mean ± SEM, (n= 6 rats per group) and student's t-test was used to compare the significant difference between groups.

Figure 2.

Effect of monosodium glutamate (MSG) oral administration on the relative weight of uterine in female rats. Comparing the mean of the relative weight of uterine tissues between control and treated groups. Data were presented as mean ± SEM, (n= 6 rats per group). At the end of the experiment, the weight of uterine tissues was recorded using an electronic balance. The student’s t-test was used to compare the significant difference between MSG-treated group and control.

Figure 3.

Photomicrographs of rat uterine sections. Lumen area (μm2), and length of stroma (μm) were higher in the control group (A) than monosodium glutamate-treated group (B), while the length of myometrium was higher in the monosodium glutamate-treated group (H & E stain, magnification 10x).

3.2. Effects of MSG on serum sex hormones (oestrogen and progesterone), body weight and food consumption

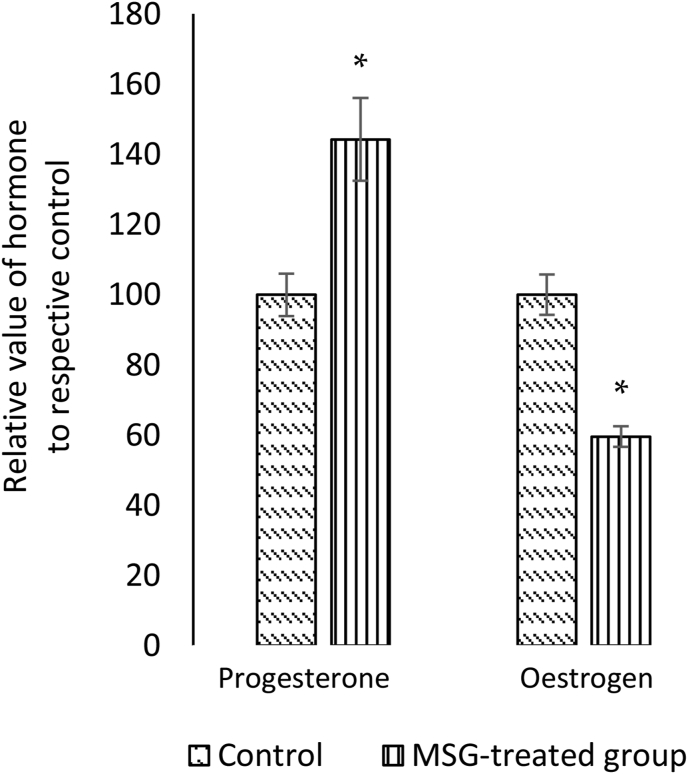

The mean relative level of progesterone in the MSG-treated female rats (144 ± 11.8 ng/ml) was significantly higher (p < 0.05) compared to the control group (100 ± 6.05 ng/ml). On the contrary, the mean relative level of oestrogen in the MSG-treated animal group (59.6 ± 2.9 pg/ml) was significantly lower (p < 0.05) compared to the control group (100 ± 2.9 pg/ml) (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Effect of monosodium glutamate (MSG) oral administration on relative levels of female sex hormones during oestrus phase in female rats. Comparing the mean relative levels of serum oestrogen (pg/ml) and progesterone (ng/ml) between control and MSG-treated group. The chemiluminescent immunoassay (Beckman coulter Access II, USA) was used. Data were presented as mean ± SEM, (n= 6 rats per group). Student’s t-test was used to compare between MSG-treated group and control, and differences were considered significant at ∗p < 0.05 compared to control group.

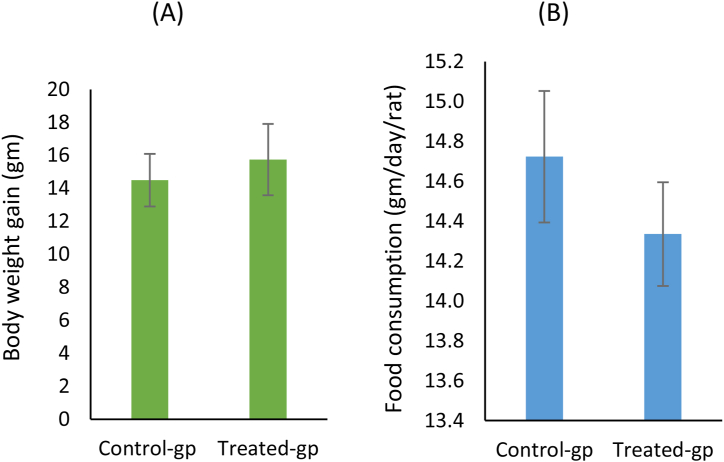

Oral feeding of female rats with MSG (2 g/kg) for 14 days showed a non-significantly increase in body weight of rats compared to the control group (Figure 5a). However, the mean food consumption (g/day/rat) showed no difference between the MSG-treated animal and the control group (Figure 5b).

Figure 5.

Effect of monosodium glutamate (MSG) oral administration on body weight and food consumption in female rats (A) Comparing the mean body weight gain (gm) and (B) food consumption (gm/day/rat) in the control and treated groups.

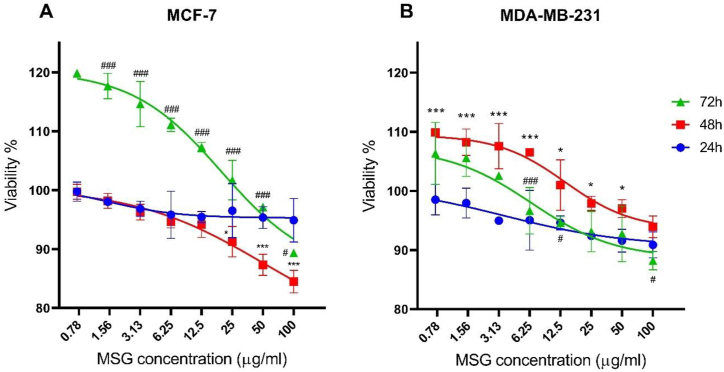

3.3. Cytotoxic effect of MSG on oestrogen-positive and negative cells

The cytotoxic effect of MSG on MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 cells was investigated using an MTT assay. MSG caused a mild cytotoxic effect (<20%) on both cell lines after 24, 48, and 72 h, particularly at concentrations between 25 and 100 μg/ml. MSG showed a higher cytotoxic effect on oestrogen-positive MCF-7 cells after 48 h compared to oestrogen negative MDA-MB-231 cells (Figure 6). However, the IC50 of MSG that causes 50% cell growth inhibition in both cell lines needs higher concentrations of MSG to be achieved.

Figure 6.

The cytotoxic effect of monosodium glutamate (MSG) on the cell viability of the oestrogen-positive MCF-7 (A) and the oestrogen-negative MDA-MB-231 (B) cells at 24, 48 and 72 h. The data were presented as mean ± SD, n = 3. ∗p ≤ 0.05; and ∗∗∗p ≤ 0.001 indicate a significant difference between 24 h and 48 h, while #p ≤ 0.05; and ###p ≤ 0.001 indicate a significant difference between 48 h and 72 h.

3.4. Computational toxicity of MSG and molecular docking

The computational prediction of toxicity results showed relatively a low systemic toxic effect of the MSG (PubChem ID 23672308). According to the ProTox-II tool, the predicted toxicity class of MSG is V and the predicted LD50 was 4500 mg/kg, which indicates a possibility to be harmful if swallowed (2000 < LD50 ≤ 5000). In addition, the iSafeRat® tool predicted the mechanism of MSG toxicity to be due to high binding affinity to acetylcholine (Ach) receptors (muscarinic or nicotinic), which may involve in disrupting the normal nerve signal transmissions (class 5.2) and release of protons in the cytosol of cells for all species (class 6.2).

Furthermore, the MSG descriptor was calculated (Table 1). The ω is considered as an indicator of reactivity that allows a quantitative classification of the global electrophilic nature of a molecule. Then Δω was assessed as the smaller the value indicates the stronger the electrophile-nucleophile interaction. Findings showed that MSG is weak as an electrophilic attacker on the biological macromolecules.

Table 1.

The quantum descriptor of monosodium glutamate (MSG).

| PubChem CID | 23672308 |

|---|---|

| Formula | C₅H₈NO₄Na |

| Enthalpy (au) | -551.3 |

| Entropy (J/mol·K) | 443 |

| Gibbs Energy (au) | -551.4 |

| Cv (J/mol·K) | 163.54 |

| LUMO (ev) | 2.13 |

| HOMO (ev) | -8.89 |

| ω (eV) | 0.52 |

| ω-max | 0.09 |

| ω+ max | 0.04 |

| Δω | 0.002 |

| LogP | 5.64 |

Additional details on the quantitative structure-activity relationship (QSAR) prediction for MSG are provided in Supplementary Table S1.

By searching the previous studies [19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24], we found 33 proteins that have a role in the oxidative stress and hormonal regulation of female reproduction (Supplementary Table S2). By comparing the binding affinity and the number of interacting residues (Table 2) of the protein-ligand between MSG and the commercial inhibitors, the analysis showed that MSG has very weak and nonspecific interaction with the majority of the targets. However, a good binding affinity was noticed with some critical proteins, including cytochrome C oxidase subunit 2, proline-rich AKT1 substrate 1, prostaglandin synthase, and transforming protein RhoA. Interestingly MSG showed a good binding affinity with low inhibition constant with human oestrogen receptors beta.

Table 2.

Molecular Docking results of monosodium glutamate (MSG) and the commercial inhibitors with the oxidative stress and hormonal-related proteins.

| Protein Name/Symbol | PDB IDa | MSG |

Commercial inhibitor |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2D diagram of interaction | No of interacting residues | Affinityb | Kic | Inhibitor Name | PubChem ID | 2D diagram of interaction | No of interacting residues | Affinityb | Kic | ||

| Apoptosis regulator BAX (BAX) | 6EB6 |  |

8 | -4.6 | 415.9 | BAI1 | 2729027 |  |

2 | -6.4 | 20.21 |

| Bcl-2-related protein A1 (BCL2A1) | 5WHI |  |

6 | -4.8 | 315.3 | S55746 | 71654876 |  |

5 | -8.6 | 0.51 |

| Caspase 3 (CASP3) | 1NME |  |

2 | -4.5 | 471.6 | Ac-DEVD-CHO | 644345 |  |

8 | -6.1 | 36.57 |

| Caspase 7 (CASP7) | 4FDL |  |

4 | -4.5 | 468.7 | Ac-DEVD-CHO | 644345 |  |

8 | -6.2 | 28.51 |

| Caspase-8 (CASP8) | 1QTN |  |

6 | -4.7 | 340.8 | Ac-DEVD-CHO | 644345 |  |

3 | -9.4 | 0.13 |

| Caspase-9 (CASP9) | 1NW9 |  |

13 | -4.8 | 312.9 | Ac-DEVD-CHO | 644345 |  |

13 | -8.6 | 0.52 |

| Cytochrome C oxidase subunit 2 (MT-CO2) | 5Z62 |  |

14 | -5.6 | 75.6 | Indomethacin | 3715 |  |

18 | -8.2 | 0.93 |

| Glutamate dehydrogenase 1 (GLUD1) | 1L1F |  |

3 | -4.8 | 311.1 | (-)-Epigallocatechin Gallate | 65064 |  |

9 | -9.6 | 0.09 |

| Glutaminase (GLS) | 3CZD |  |

12 | -4.8 | 324.9 | BPTES | 3372016 |  |

20 | -7.7 | 2.11 |

| Human estrogens receptors alpha (ESR1) | 1ERE |  |

2 | -4.8 | 323.1 | AZD9496 | 11201035 |  |

6 | -7.4 | 3.53 |

| Human oestrogen receptor beta (ESR2) | 1U3Q |  |

15 | -5.2 | 151.0 | PHTPP | 11201035 |  |

12 | -6.7 | 11.64 |

| Insulin like growth factor binding protein 1 (IGF1R) | 2DSQ |  |

6 | -4.1 | 1012.7 | NVP-AEW541 | 11476171 |  |

8 | -7.5 | 2.97 |

| Macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF) | 1CA7 |  |

12 | -5.0 | 200.7 | ISO-1 | 4633677 |  |

12 | -7.8 | 1.88 |

| Oxytocin receptor (OXTR) | 6TPK |  |

11 | -4.7 | 354.3 | L-371,257 | 6918320 |  |

25 | -9.9 | 0.05 |

| Phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate 3-kinase catalytic subunit alpha isoform (PIK3CA) | 2AR5 |  |

7 | -5.0 | 202.8 | BAY1082439 | 135905473 |  |

8 | -6.9 | 9.38 |

| Progesterone receptors (PRGR) | 1A28 |  |

12 | -4.7 | 384.2 | Mifepristone | 55245 |  |

15 | -6.7 | 13.02 |

| Proline-rich AKT1 substrate 1 (AKT1S1) | 6NPZ |  |

15 | -5.4 | 106.0 | 3CAI | 152961 |  |

13 | -6.3 | 25.34 |

| Prostaglandin E synthase (PTGES) | 3DWW |  |

12 | -5.6 | 82.3 | beta-Boswellic acid | 168928 |  |

6 | -6.8 | 10.95 |

| Prostaglandin F synthase (PTGFR) | 2F38 |  |

4 | -5.4 | 105.4 | N- (4-chlorobenzoyl)-melatonin | 86086004 |  |

5 | -9.3 | 0.16 |

| Prostaglandin G/H synthase 2 (PTGS2) | 5IKR |  |

6 | -5.4 | 116.8 | TG4-155 | 5886965 |  |

9 | -8.5 | 0.59 |

| Transforming protein RhoA (RhoA) | 1S1C |  |

7 | -5.9 | 46.2 | Rhosin hydrochloride | 4304262 |  |

9 | -9.1 | 0.21 |

| Type-1 angiotensin II receptor (AGTR1) | 4YAY |  |

3 | -4.8 | 325.8 | Valsartan | 60846 |  |

8 | -8.3 | 0.81 |

| Tyrosinase (TYR) | 5M8N |  |

5 | -5.1 | 172.4 | Isobutylamido thiazolyl resorcinol | 71543007 |  |

6 | -7.4 | 3.91 |

Proteins data bank (https://www.rcsb.org/).

Binding Affinity (kcal/mol).

Inhibitor constant (μmol).

4. Discussion

Oral administration of MSG (2 g/kg) for 14 days to SD female rats with regular ECs resulted in an alteration of serum progesterone and oestrogen levels without significant changes in uterine morphology. For the in vitro study, a slight cytotoxic effect was observed on MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 cells after treatment with serial concentrations of MSG over three-time points, however, the cytotoxic was more pronounced in oestrogen-positive MCF-7 cells after 48 h of treatment. Neuronal toxicity and oxidative stress were the predicted mechanisms of toxicity.

Treating the female rats with MSG for two weeks altered the serum levels of progesterone and oestrogen, which are comparable to the findings of previous studies that reported abnormality in the ovarian hormone with increased serum progesterone levels [25, 26]. However, the observed oestrogen levels in this study are inconsistent with a study that reported a significant 2-fold increase in serum oestrogen levels compared to control when Wistar rats were treated with 100 mg/kg MSG for 60 days [27]. The effects of MSG on oestradiol (oestrogen) levels could be due to the long exposure time, which could be attributed to the activation of aromatase, which catalyses the conversion of testosterone to β-oestradiol and the aromatization of ring A of β-oestradiol, resulting in increased oestradiol synthesis. In addition, treating rats with MSG showed some uterine morphological changes including the lumen area and lengths of stroma and myometrium compared to the control.

A previous histological assessment of the rats' ovaries administrated MSG showed cellular hypertrophy, degenerative and atrophic changes [28]. Moreover, a study by AL-Shemary (2017) showed that administrating MSG for one month significantly decreases the weight of ovaries, and some changes in the histology of ovaries were observed, including congested blood vessels of the medulla, and increased atretic follicles. Furthermore, examining the uterus showed necrosis in the perimetrium and the presence of lacunae in the wall structure [29]. In our study, neither the change of the body weight nor uterine weight was significantly different when compared to the control group. This observation was not in line with Koffuor’s finding [30], who reported a significant increase in uterine weight when compared to the control. Unlike the observation of Adamo & Ratner [31], who reported an insignificant changes in the relative uterine weight compared to the control.

The previous studies showed that prolonged intake of food containing MSG or glutamate salt in humans and animals results in altering the metabolism processes and oxidation balance in different organs such as the liver, pancreas, and kidney, or systems such as the nervous system and endocrine system [32, 33, 34]. The systemic alteration of the metabolism and oxidation processes by MSG may affect the function of males' and females’ reproductive systems. Previous research showed impairment of the male reproductive function after consuming MSG, including a reduction in sperm count and morphology, and testicular haemorrhage, which was connected to male infertility [8]. Histologically, higher doses of MSG in rats showed deleterious effects on the morphology of fallopian tubes, ovary and uterus, which also connected to infertility [26, 35, 36]. These harmful effects of MSG on the reproductive system could be attributed to the indirect alteration of the regulatory axis of the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonads [11]. Several interesting aspects need to be explored further by long-term study.

Physiologically, several changes to the uterine lining (endometrium) occur during the uterine cycle, it grows to a thick, blood vessel-rich tissue lining, representing an optimal environment for the implantation of a blastocyst upon its arrival in the uterus. The uterine cycle is controlled by a series of changes in hormone levels, primarily oestrogen and progesterone. Thus any changes in their levels directly affect the fertility function [37]. A previous study by Mondal et al. found that administrating MSG to rats impaired ovarian function and decreases the duration of proestrus, oestrus and metestrus phases in each EC, which could be due to the significant increase in the secretion of luteinizing hormone (LH) and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) from the pituitary gland and oestradiol from the proliferating ovarian follicles [38]. Moreover, it was suggested that MSG probably promotes the maturation of the ovarian follicles from the primary follicles due to the suppression of progesterone production during the dioestrus phase in EC as revealed by the regression of corpus luteum in comparison to control ovarian tissues sections [38]. In addition, MSG may impair the female reproductive organs through increased oxidative stress [39] and decreased antioxidant enzymes like glutathione reductase, and glutathione peroxidase in ovarian tissues [26].

Furthermore, MSG may cause some metabolic abnormality [40]. It has been reported that excessive intake of MSG is connected to an increase in the incidence of type two diabetes mellitus [33], and increase body weight and fat mass in rodents models [32, 41, 42].

The cytotoxic effect of MSG was tested on MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 cells. The two cell lines were selected to cover different phenotypic and genotypic variabilities of oestrogen receptors. Cell viability results showed that the MSG compound has a mild cytotoxic effect on both cell lines, especially at concentrations between 25 and 100 μg/ml. However, MCF-7 positive oestrogen receptor cells revealed slightly less cell proliferation after 48 h compared to MDA-MB-231 treated cells, which indicates that oestrogen-positive cells are more sensitive to the cytotoxic effects of MSG. Although the triple-negative MDA-MB-231 cell line is more resistant to treatment, another study reported that MDA-MB-231 showed more susceptibility to drug toxicity in comparison to MCF-7 [43]. Our result revealed that MDA-MB-231 cell proliferation dropped after 72 h treatment with MSG. Therefore, long-term MSG cytotoxicity could be further explored in future studies using higher concentrations. Moreover, according to the ProTox-II tool, the predicted lethal dose was determined as 4500 mg/kg. To apply this dose in an in vitro cytotoxicity model, investigations using a higher MSG concentration on both cell lines may result in a more cytotoxic effect.

The computational chemistry tools were used to explore the toxicity of MSG. Overall, MSG showed a possibility of being harmful if swallowed (OECD class 5), and neurological toxicity was predicted by affecting ACh receptors, which consist of the nature of glutamate as a neurotransmitter. Therefore, excessive intake of MSG in the long term may cause several neurological adverse effects. Further neurotoxicity associated with MSG has also been linked to the over-activation of glutamate receptors, which in turn are implicated in brain function and pathology [44]. We found that the predicted mechanism of toxicity of MSG could be through disrupting the normal nerve signal transmissions and the release of protons in the cytosol of cells. Intriguingly, it was reported that the glutamate receptors, including GluR 2/3, metabotropic glutamate receptor 2/3, kainate 2, and N-methyl D-aspartate receptor 1 (NMDAR 1) were localized in the different structures of the female reproductive system, including ovaries, uterine cervix, and endometrium [45], suggesting that the neuroexcitatory targets the female reproductive function.

Furthermore, we assessed the toxicity using the quantum descriptors, based on the principle that cytotoxicity could occur by an electrophilic and nucleophilic attack and forming covalent bonds with an electron-rich nucleophilic target, e.g., amino acids, enzymes, or DNA. Findings showed that MSG was able to make an electrophilic attack against nucleophilic cellular macromolecules. However, MSG safety could be attributed to the contribution of other physicochemical properties, e.g., lipophilicity and ionisation state, which could affect the electrophile nature. Besides, the antioxidant mechanisms include glutathione-electrophile conjugation [46]. However, the computational study is more focusing on the acute action, not on the chronic exposure to MSG, which limits our results.

Furthermore, to explore the interaction of MSG with the uterus function we performed molecular docking with many uterus-related proteins. In general, there was weak interaction of MSG compared to the commercial inhibitors. However, this does not exclude the indirect inhibition, thus in vitro validation is needed. Surprisingly, a good binding affinity of MSG with human oestrogen receptor beta was found. These findings matched with a previous study that explored the relationship of oestrogen receptors α and β with GluR in the female rodent brain, which results in modulating intracellular G-protein signalling cascades to stimulus neuronal physiology, and ultimately behaviour [47]. Furthermore, docking results indicate good binding with different isomers of prostaglandin, indicating involving of MSG with the inflammation pathway, which could be a lighting point to explore the cytotoxicity based on the long term.

5. Conclusions

The alteration in serum progesterone and oestrogen levels caused by oral administration of 2 g/kg MSG for 14 days may result in an abnormality in the functions of reproductive organs in young female rats. Neuronal toxicity can be one of the mechanisms of MSG influencing progesterone and oestrogen levels. Involving of MSG with the inflammatory pathway and binding human oestrogen beta receptors play roles in uterine functions. Therefore, a precaution should be taken when utilising MSG, especially for females associated with a high risk of hormonal disturbance. Further studies should be conducted to evaluate the long-term safety of MSG on corpus luteum function.

Declarations

Author contribution statement

Mahfoudh A. M. Abdulghani: Analyzed and interpreted the data; Conceived and designed the experiments; Wrote the paper.

Salah Abdulrazak Alshehade; Sareh Kamran: Analyzed and interpreted the data.

Mohammed Abdullah Alshawsh: Conceived and designed the experiments; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data; Wrote the paper.

Funding statement

This work was supported by a research grant from Universiti Malaya, project number [ST070-2021].

Data availability statement

Data included in article/supp. material/referenced in article.

Declaration of interest’s statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

No additional information is available for this paper.

Contributor Information

Mahfoudh A.M. Abdulghani, Email: m.abdulghani@ust.edu.

Mohammed Abdullah Alshawsh, Email: alshaweshmam@um.edu.my.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the supplementary data related to this article:

Quantitative structure-activity relationship (QSAR) prediction for monosodium glutamate (MSG)

Molecular docking of MSG with 33 proteins related to oxidative stress and hormonal regulation of female reproduction.

References

- 1.Bera T.K., Kar S.K., Yadav P.K., Mukherjee P., Yadav S. World Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences effects of monosodium glutamate on human health. World J. Pharm. Sci. 2017;5:139–144. http://www.wjpsonline.org/ [Google Scholar]

- 2.Markits I.H.S. 2018. Monosodium glutamate (MSG) chemical Economics Handbook; pp. 1–88.https://ihsmarkit.com/products/monosodium-glutamate-chemical-economics-handbook.html (Retrieved from Chem. Econ. Handb. https//Ihsmarkit.Com/Products/Monosodium-Glutamate-Chemical-Economics-Handbook.Html). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Husarova V., Ostatnikova D., Glutamate Toxic Effects Monosodium, Implications Their. For human intake: a review. JMED Res. 2013:1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Walker R., Lupien J.R. The safety evaluation of monosodium glutamate, J. Nutr. 2000;130:1049S–1052S. doi: 10.1093/jn/130.4.1049S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ganesan K., Sukalingam K., Balamurali K., Radziah S., Sheikh B., Ponnusamy K., Ariffin I.A., Gani S.B. A studies on monosodium L- glutamate toxicity in animal models- a review. Int. J. Pharmaceut. Chem. Biol. Sci. 2013;3:1257–1268. www.ijpcbs.com Available online at. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Geha R.S., Beiser A., Ren C., Patterson R., Greenberger P.A., Grammer L.C., Ditto A.M., Harris K.E., Shaughnessy M.A., Yarnold P.R., Corren J., Saxon A. Review of alleged reaction to monosodium glutamate and outcome of a multicenter double-blind placebo-controlled study. J. Nutr. 2000;130:1058S–1062S. doi: 10.1093/jn/130.4.1058S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Oforofuo I.A.O., Onakewhor J.U.E., Idaewor P.E. The effect of chronic administration of MSG on the histology of the adult Wistar rat testes, Bio Res Commun. 1997;9:30–56. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Onakewhor J.U.E., Oforofuo I.A.O., Singh S.P. Chronic administration of Monosodium glutamate Induces Oligozoospermia and glycogen accumulation in Wister rat testes. Afr. J. Reprod. Health. 1998;2:190–197. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kumar N., Damodara Gowda K., Na V., Sabarinath P., Ahemed B., Ramaswamy C., Bhat M. Role of ascorbic acid in monosodium glutamate mediated effect on testicular weight, sperm morphology and sperm count. Rat Testis, J. Chinese Clin. Med. 2008;3:1–5. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/285877616_Role_of_ascorbic_acid_in_monosodium_glutamate_mediated_effect_on_testicular_weight_sperm_morphology_and_sperm_count_in_rat_testis [Google Scholar]

- 10.Das R.S., Ghosh S.K. Long term effects of monosodium glutamate on spermatogenesis following neonatal exposure in albino mice–a histological study. Nepal Med. Coll. J. 2010;12:149–153. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Igwebuike U.M., Ochiogu I.S., Ihedinihu B.C., Ikokide J.E., Idika I.K. The effects of oral administration of monosodium glutamate (msg) on the testicular morphology and cauda epididymal sperm reserves of young and adult male rats. Vet. Arh. 2011;81:525–534. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhankina R., Baghban N., Askarov M., Saipiyeva D., Ibragimov A., Kadirova B., Khoradmehr A., Nabipour I., Shirazi R., Zhanbyrbekuly U., Tamadon A. Mesenchymal stromal/stem cells and their exosomes for restoration of spermatogenesis in non-obstructive azoospermia: a systemic review. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2021;12:229. doi: 10.1186/s13287-021-02295-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cordier S. Evidence for a role of paternal exposures in developmental toxicity. Basic Clin. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2008;102:176–181. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-7843.2007.00162.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chevrier C., Dananché B., Bahuau M., Nelva A., Herman C., Francannet C., Robert-Gnansia E., Cordier S. Occupational exposure to organic solvent mixtures during pregnancy and the risk of non-syndromic oral clefts. Occup. Environ. Med. 2006;63:617–623. doi: 10.1136/oem.2005.024067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wennborg H., Bonde J.P., Stenbeck M., Olsen J. Adverse reproduction outcomes among employees working in biomedical research laboratories. Scand. J. Work. Environ. Health. 2002;28:5–11. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Barlow S.M., Sullivan F.M. Reproductive hazards of industrial chemicals: an evaluation of animal and human data, Altern. Lab. Anim. 1983;11:36. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bulger W.H. Estrogenic activity of pesticides and other xenobiotics on the uterus and male reproductive tract, Endocr. Toxicol. 1985:1–33. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hughes C.L. Phytochemical mimicry of reproductive hormones and modulation of herbivore fertility by phytoestrogens. Environ. Health Perspect. 1988;78:171–175. doi: 10.1289/ehp.8878171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Al-Salahi R., Taie H.A.A., Bakheit A.H., Marzouk M., Almehizia A.A., Herqash R., Abuelizz H.A. Antioxidant activities and molecular docking of 2-thioxobenzo[g]quinazoline derivatives. Pharmacol. Rep. 2019;71:695–700. doi: 10.1016/j.pharep.2019.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Huang M., Li X., Guo P., Yu Z., Xu Y., Wei Z. The abnormal expression of oxytocin receptors in the uterine junctional zone in women with endometriosis, Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. 2017;15 doi: 10.1186/s12958-016-0220-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lu J., Wang Z., Cao J., Chen Y., Dong Y. A novel and compact review on the role of oxidative stress in female reproduction, Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. 2018;16 doi: 10.1186/s12958-018-0391-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vrachnis N., Malamas F.M., Sifakis S., Deligeoroglou E., Iliodromiti Z. The oxytocin-oxytocin receptor system and its antagonists as tocolytic agents, Int. J. Endocrinol. 2011;2011 doi: 10.1155/2011/350546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wangsa K., Sarma I., Saikia P., Ananthakrishnan D., Sarma H.N., Velmurugan D. Estrogenic effect of scoparia dulcis (Linn) extract in mice uterus and in silico molecular docking studies of certain compounds with human estrogen receptors. J. Reproduction Infertil. 2020;21:247–258. doi: 10.18502/jri.v21i4.4329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yuan L., Dietrich A.K., Nardulli A.M. 17β-Estradiol alters oxidative stress response protein expression and oxidative damage in the uterus. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2014;382:218–226. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2013.09.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Agbadua O.G., Idusogie L.E., Chukwuebuka A.S., Nnamdi C.S., Sylvester S. Evaluating the protective and ameliorative potential of unripe palm kernel seeds on monosodium glutamate-induced uterine fibroids. OALib. 2020;7:1–11. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mondal M., Sarkar K., Nath P.P., Khatun A., Pal S., Paul G. Monosodium glutamate impairs the contraction of uterine visceral smooth muscle ex vivo of rat through augmentation of acetylcholine and nitric oxide signaling pathways. Reprod. Biol. 2018;18:83–93. doi: 10.1016/j.repbio.2018.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Obochi G.O., Malu S.P., Obi-Abang M., Alozie Y., Iyam M.A. Effect of garlic extracts on Monosodium Glutamate (MSG) induced fibroid in wistar rats. Pakistan J. Nutr. 2009;8:970–976. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Eweka A., Om’iniabohs F. Histological studies of the effects of monosodium glutamate on the kidney of adult Wistar rats. Internet J. Health. 2012;6:37–43. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.AL-Shemary N.N.A. Histological changes after monosodium glutamate administration on reproductive system for each male and female adult albino mice. Iraqi J. Embryos Infertil. Res. 2017;7 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Koffuor G. Effect of ethanolic stem bark extract of Blighia unijugata (Sapindaceae) on monosodium glutamate-induced uterine leiomyoma in Sprague-Dawley rats. Br. J. Pharmaceut. Res. 2013;3:880–896. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Adamo N.J., Ratner A. Monosodium glutamate: lack of effects on brain and reproductive function in rats. Science (80-.) 1970;169:673–674. doi: 10.1126/science.169.3946.673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hernández-Bautista R.J., Alarcón-Aguilar F.J., Escobar-Villanueva M.D.C., Almanza-Pérez J.C., Merino-Aguilar H., Fainstein M.K., López-Diazguerrero N.E. Biochemical alterations during the obese-aging process in female and male monosodium glutamate (MSG)-treated mice. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2014;15:11473–11494. doi: 10.3390/ijms150711473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Boonnate P., Waraasawapati S., Hipkaeo W., Pethlert S., Sharma A., Selmi C., Prasongwattana V., Cha’on U. Monosodium glutamate dietary consumption decreases pancreatic β-cell mass in adult Wistar rats. PLoS One. 2015;10 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0131595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Api A.M. Evaluation of the dermal subchronic toxicity of phenoxyethyl isobutyrate in the rat. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2004;42:313–317. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2003.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Eweka A., Eweka A., Om’Iniabohs F. Histological studies of the effects of monosodium glutamate on the fallopian tubes of adult female wistar rats. Ann. Biomed. Sci. 2011;9:146. doi: 10.4297/najms.2010.3146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Oladipo I.C., Adebayo E.A., Kuye O.M., State O. Original research article effects of monosodium glutamate in ovaries of female sprague-Dawley rats. Int. J. Curr. Microbiol. Appl. Sci. 2015;4:737–745. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Darnel A.D. Cambridge University Press; 2021. Repro-6: anatomy & physiology of the female reproductive system II; pp. 28–55. (A Textb. Clin. Embryol.). [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mondal M., Sarkar K., Nath P.P., Paul G. Monosodium glutamate suppresses the female reproductive function by impairing the functions of ovary and uterus in rat. Environ. Toxicol. 2018;33:198–208. doi: 10.1002/tox.22508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Umukoro S., Oluwole G.O., Olamijowon H.E., Omogbiya A.I., Eduviere A.T. Effect of monosodium glutamate on behavioral phenotypes, biomarkers of oxidative stress in brain tissues and liver enzymes in mice. World J. Neurosci. 2015;5:339–349. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gaspar R.S., Benevides R.O.A., de Lima Fontelles J.L., Vale C.C., França L.M., Silva Barros P. De T., de Andrade Paes A.M. Reproductive alterations in hyperinsulinemic but normoandrogenic MSG obese female rats. J. Endocrinol. 2016;229:61–72. doi: 10.1530/JOE-15-0453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pelantová H., Bártová S., Anýž J., Holubová M., Železná B., Maletínská L., Novák D., Lacinová Z., Šulc M., Haluzík M., Kuzma M. Metabolomic profiling of urinary changes in mice with monosodium glutamate-induced obesity. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2016;408:567–578. doi: 10.1007/s00216-015-9133-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ugur Calis I., Turgut Cosan D., Saydam F., Kerem Kolac U., Soyocak A., Kurt H., Veysi Gunes H., Sahinturk V., Sahin Mutlu F., Ozdemir Koroglu Z., Degirmenci I. The effects of monosodium glutamate and tannic acid on adult rats, Iran. Red Crescent Med. J. 2016;18 doi: 10.5812/ircmj.37912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Theodossiou T.A., Ali M., Grigalavicius M., Grallert B., Dillard P., Schink K.O., Olsen C.E., Wälchli S., Inderberg E.M., Kubin A., Peng Q., Berg K. Simultaneous defeat of MCF7 and MDA-MB-231 resistances by a hypericin PDT–tamoxifen hybrid therapy. Npj Breast Cancer. 2019;5:1–10. doi: 10.1038/s41523-019-0108-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chakraborty S.P. Patho-physiological and toxicological aspects of monosodium glutamate. Toxicol. Mech. Methods. 2019;29:389–396. doi: 10.1080/15376516.2018.1528649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gill S., Barker M., Pulido O. Neuroexcitatory targets in the female reproductive system of the nonhuman primate (Macaca fascicularis) Toxicol. Pathol. 2008;36:478–484. doi: 10.1177/0192623308315663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.LoPachin R.M., Geohagen B.C., Nordstroem L.U. Mechanisms of soft and hard electrophile toxicities. Toxicology. 2019;418:62–69. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2019.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tonn Eisinger K.R., Gross K.S., Head B.P., Mermelstein P.G. Interactions between estrogen receptors and metabotropic glutamate receptors and their impact on drug addiction in females. Horm. Behav. 2018;104:130–137. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2018.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Abdulghani M., Hussin A.H., Sulaiman S.A., Chan K.L. The ameliorative effects of eurycoma longifolia jack on testosterone-induced reproductive disorders in female rats, Reprod. Biol. 2012;12:247–255. doi: 10.1016/s1642-431x(12)60089-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ajayi A.F., Akhigbe R.E. Staging of the estrous cycle and induction of estrus in experimental rodents: an update. Fertil. Res. Pract. 2020;6:5. doi: 10.1186/s40738-020-00074-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Marcondes F.K., Bianchi F.J., Tanno A.P. Determination of the estrous cycle phases of rats: some helpful considerations. Braz. J. Biol. 2002;62:609–614. doi: 10.1590/s1519-69842002000400008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yang T., Aimaiti M., Su D., Miao W., Zhou B., Maimaitiyiming D., Yusup A., Upur H., Aikemu A. Enhanced efficacy with reduced toxicity of chemotherapy drug 5-fluorouracil by synergistic treatment with Abnormal Savda Munziq from Uyghur medicine. BMC Compl. Altern. Med. 2017;17:1–10. doi: 10.1186/s12906-017-1685-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Banerjee P., Eckert A.O., Schrey A.K., Preissner R. ProTox-II: a webserver for the prediction of toxicity of chemicals, Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46:W257–W263. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bauer F.J., Thomas P.C., Fouchard S.Y., Neunlist S.J.M. A new classification algorithm based on mechanisms of action, Comput. Toxicol. 2018;5:8–15. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yap C.W. PaDEL-descriptor: an open source software to calculate molecular descriptors and fingerprints. J. Comput. Chem. 2011;32:1466–1474. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pandith A.H., Giri S., Chattaraj P.K. A comparative study of two quantum chemical descriptors in predicting toxicity of aliphatic compounds towards Tetrahymena pyriformis, Org. Chem. Insights. 2010;2010:1–17. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fonseca Guerra C., Handgraaf J.W., Baerends E.J., Bickelhaupt F.M. Voronoi Deformation Density (VDD) charges: assessment of the Mulliken, Bader, Hirshfeld, Weinhold, and VDD methods for charge analysis. J. Comput. Chem. 2004;25:189–210. doi: 10.1002/jcc.10351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Roy D.R., Sarkar U., Chattaraj P.K., Mitra A., Padmanabhan J., Parthasarathi R., Subramanian V., Van Damme S., Bultinck P. Analyzing toxicity through electrophilicity. Mol. Divers. 2006;10:119–131. doi: 10.1007/s11030-005-9009-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Trott O., Olson A.J. AutoDock Vina: improving the speed and accuracy of docking with a new scoring function, efficient optimization, and multithreading. J. Comput. Chem. 2010;31:455–461. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Quantitative structure-activity relationship (QSAR) prediction for monosodium glutamate (MSG)

Molecular docking of MSG with 33 proteins related to oxidative stress and hormonal regulation of female reproduction.

Data Availability Statement

Data included in article/supp. material/referenced in article.