Abstract

Background: Association between antibiotic use and antimicrobial resistance has been demonstrated in several studies; hence the importance of antibiotic stewardship programs (ASPs) to reduce the burden of this resistance.

Aim: To describe the antibiotic stewardship team (AST) interventions in a Tunisian university hospital.

Methods: a cross-sectional study was conducted in the infectious diseases department in Sousse-Tunisia between 2016 and 2020. Hospital and private practice doctors have been informed of the existence of an antibiotic stewardship team. Interventions consisted of some helps to antibiotic therapy (i.e.; prescription, change or discontinuation) and/or diagnosis (i.e.; further investigations).

Results: Two thousand five hundred and fourteen interventions were made including 2288 (91%) in hospitalized patients, 2152 (86%) in university hospitals and 1684 (67%) in medical wards. The most common intervention consisted of help to antibiotic therapy (80%). The main sites of infections were skin and soft tissues (28%) and urinary tract (14%). Infections were microbiologically documented in 36% of cases. The most frequently isolated microorganisms were Enterobactriaceae (41%). Antibiotic use restriction was made in 44% of cases including further investigations (16%), antibiotic de-escalation (11%), no antibiotic prescription (9%) and antibiotic discontinuation (8%). In cases where antibiotics have been changed (N=475), the intervention was associated with an overall decrease in the prescription of broad-spectrum antibiotics from 61% to 50% with a decrease in the prescription of third generation cephalosporins from 22% to 15%.

Conclusions: The majority of antibiotic stewardship team’s interventions were made in hospitalized patients, university hospitals and medical wards. These interventions resulted in an overall and broad-spectrum antibiotic use reduction.

Keywords: antimicrobial resistance, Enterobacteriaceae, antibiotic stewardship.

Résumé

Introduction: L’association entre l’usagedes antibiotiques et la résistance bactérienne a été démontrée dans plusieurs études d’où l’importance des programmes de bon usage des antibiotiques pour réduire la fréquence de cette résistance.

Objectif: Décrire les interventions de l’équipe mobile d’antibiothérapie dans un hôpital universitaire Tunisien.

Méthodes: Une étude transversale a été réalisée au service de Maladies Infectieuses de Sousse-Tunisie entre 2016 et 2020. Les médecins hospitaliers et de libre pratique ont été informés de l’existence d’une équipe mobile d’antibiothérapie. Les interventions consistaient en l’aide à l’antibiothérapie (prescription, changement ou arrêt) et/ou au l’aide au diagnostic (demande d’examens complémentaires).

Résultats: Deux milles cinq cents quatorze interventions ont été faites incluant 2288 (91%) chez des patients hospitalisés, 2152 (86%) dans des hôpitaux universitaires et 1684 (67%) dans des services médicaux. L’intervention la plus fréquente était l’aide à l’antibiothérapie (80%). Les principaux sites d’infection étaient la peau et les tissus mous (28%) et l’appareil urinaire (14%). Les infections étaient documentées microbiologiquement dans 36% des cas. Les microorganismes les plus fréquemment isolés étaient les entérobactéries (41%). Une réduction de la prescription des antibiotiques a été réalisée dans 44% des cas incluant la demande d’examens complémentaires (16%), la désescalade antibiotique (11%), la non prescription d’antibiotiques (9%) et l’arrêt de l’antibiothérapie (8%). Dans les cas où l’antibiothérapie a été changée (N=475), l’intervention était associée à une diminution dans la prescription d’antibiotiques à large spectre de 61% à 50% avec une diminution dans la prescription de céphalosporines de troisième génération de 22% à 15%.

Conclusions: La majorité des interventions de l’équipe mobile d’antibiothérapie ont été faites chez des patients hospitalisés, dans des hôpitaux universitaires et dans des services médicaux. Ces interventions ont abouti à une réduction de la prescription globale des antibiotiques et de la prescription des antibiotiques à large spectre.

Mots Clés: résistance bactérienne, Entérobactéries, bon usage des antibiotiques.

INTRODUCTION:

Emergence and diffusion of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) is a serious public health concern with a considerable human and economic cost worldwide (1 ). It is estimated that by 2050, continued rise in AMR would result in 10 million deaths in the world every year and would cost up to 100 trillion USD (1 ).

In Tunisia, which was the second largest consumer of antibiotics in the world in 2015 (2 ), the use of antibiotics has increased by 38% between 2005 and 2013 (3 ). During the last decade, the resistance rates of Escherichia coli have increased from 5% to 19% for the third-generation cephalosporins and from 14% to 25% for the fluoroquinolones; those of Klebsiella pneumoniae have increased from 27% to 43% for the third-generation cephalosporins and from 0% to 12% for imipenem, while the resistance rate of Enterococcus faecium to vancomycin has increased from 0% to 38% (4, 5, 6).

Association between antibiotic use and AMR has been demonstrated in several studies, hence the importance of ASPs to reduce the burden of AMR (7, 8). Antibiotic stewardship is defined as the systematic effort to increase appropriate use of antimicrobials (7 ). It has proven efficacy in improving patient outcomes, reducing both use and costs of care (7, 8, 9, 10 ).

Since 2012, the World Health Organization and the Infectious Diseases Society of America have recommended implementing antibiotic stewardship programs in healthcare system, and many experiences have been reported in high, middle and low-income countries (11, 12 ). In Tunisia, a national action plan against AMR, including antibiotic stewardship, has been developed since 2018 (13 ), but to the best of the authors’ knowledge, no study on antibiotic stewardship has been published in Tunisia.

The aim of this study was to describe the antibiotic stewardship team interventions in a Tunisian university hospital.

METHODS

Study site

This study was conducted by the infectious diseases specialists of the department of Infectious Diseases at Farhat HACHED university hospital, Sousse, Tunisia. Tunisia is a developing upper/middle income North-African country (10 ), and Sousse is a central-eastern Tunisian city which contains two university hospitals, Farhat HACHED and Sahloul, seven private clinics, and 645 medical offices. Farhat HACHED is a 698-bed hospital with 13 medical departments, 4 surgical departments and 2 intensive care units (ICUs). Sahloul is a 632-bed hospital located 5 km from Farhat HACHED with 7 surgical departments, 6 medical departments and 2 ICUs.

Study design

A cross-sectional study was carried out to describe AST interventions between January 2016 and January 2020, before the emergence of COVID-19 epidemic in March 2020.

In our department, advices on antibiotic use have been given to other departments of the hospital since 2011 but this activity was not organized in AST. In January 2016, an AST consisting of an infectious diseases specialist and a postgraduate medial trainee, either an intern or a resident, has been implemented. The mission of AST was to help doctors to antibiotic therapy (prescription, change or discontinuation) and to diagnosis (further investigations), by phone call, bedside consultation or notes in patients’ records.

Inclusion criteria

Interventions made in hospitals, private clinics and medical offices in Sousse were included in this study.

Non-inclusion criteria

Interventions made in the Emergency department and at the outpatient clinic were not included in this study because they were part of the department activities before implementation of AST.

Study protocol

Hospital and private practice doctors have been informed of the existence of AST. For each intervention, collected data were as follows: date of intervention, primary physician healthcare setting, ward, specialty and grade; communication of intervention (phone calls, bedside consultation or notes on patients’ records), site and microbiological confirmation of infection, type of intervention (help to antibiotic therapy, help to diagnosis, antibiotic prophylaxis/chemoprophylaxis, or vaccination) and antibiotics received before and after intervention. Antibiotic use reduction was defined by any of the following interventions: no antibiotics, discontinuation of antibiotics, de-escalation (change to antibiotics with narrower spectrum) or further investigations. The study protocol is described in Figure 1 .

Figure 1. Study protocol. *antibiotic prophylaxis/ chemoprophylaxis, vaccination.

Statistical study

Statistical analysis was performed with Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 10.0. All variables were categorical, therefore, they were expressed as percentages, and significance was tested by using the Chi-square test. A p value < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Ethical considerations : As the interventions of AST were expected to be either beneficial or not to change patients management, no study protocol has been submitted to the hospital Ethics Committee approval.

RESULTS:

During the period study, two thousand five hundred and fourteen interventions were made by the AST. Baseline characteristics of the study are summarized in Figure 2 . Two thousand two hundred and eighty eight interventions (91%) were made for hospitalized patients (inpatients). The mean number of interventions was 628 per year (620-654). Two thousand one hundred and fifty two interventions (86%) were made in university hospitals, including 1546 (61%) in Farhat HACHED hospital. Primary physicians’ wards were medical in 1684 cases (67%), surgical in 729 cases (29%) and ICUs in 101 cases (4%). Twenty four specialties were involved, mainly endocrinology (10%). Primary physician was an attending doctor in 1299 cases (52%). Interventions were made via phone calls in 1109 cases (44%) and after patient bedside consultation in 815 cases (33%). Interventions of the AST consisted of help to antibiotic therapy in 2012 cases (80%) (Table 1 ).

Figure 2. Baseline characteristics of the study.

Table 1. Primary physicians and interventions characteristics.

|

Characteristics |

n (%) |

|

Primary physician healthcare setting : |

|

|

Hospital (inpatients) |

|

|

Ambulatory (outpatients) |

226 (9) |

|

Primary physician healthcare setting : |

|

|

Tertiary (university hospital) |

2152 (86) |

|

Farhat HACHED hospital |

1546 (61) |

|

Sahloul hospital |

493 (20) |

|

Others |

113 (5) |

|

Private clinic / medical office |

276 (11) |

|

Secondary / primary |

86 (3) |

|

Primary physician specialty : |

|

|

Medical |

1684 (67) |

|

Surgical |

729 (29) |

|

Intensive care |

101 (4) |

|

Primary physician ward : |

|

|

Endocrinology |

240 (10) |

|

Otorhinolaryngology |

180 (7) |

|

Internal medicine |

177 (7) |

|

Carcinology |

171 (7) |

|

Dermatology |

154 (6) |

|

Rheumatology |

134 (5) |

|

Cardiology |

126 (5) |

|

Gynecology |

122 (5) |

|

Others |

1210 (48) |

|

Primary physician grade : |

|

|

Attending doctor |

1299 (52) |

|

Assistant professor |

522 (21) |

|

Associate professor / professor |

381 (15) |

|

General practitioner |

282 (11) |

|

Specialist |

114 (5) |

|

Postgraduate trainee |

1215 (48) |

|

Intern |

825 (33) |

|

Resident |

390 (15) |

|

Communication of the intervention : |

|

|

Phone calls |

1109 (44) |

|

Bedside consultation |

815 (33) |

|

Notes in patients’ records |

590 (23) |

|

Type of the intervention : |

|

|

Help to antibiotic therapy |

2012 (80) |

|

Help to diagnosis |

351 (14) |

|

Antibiotic prophylaxis / chemoprophylaxis |

77 (3) |

|

Vaccination |

74 (3) |

|

Total |

2514 (100) |

When the intervention consisted of help to antibiotic therapy (N=2012), the main sites of infections were skin and soft tissues in 555 cases (28%), urinary tract in 277 cases (14%) (Table 2 ), and 719 infections (36%) were microbiologically documented including 582 (82%) bacterial infections. Among bacterial documented infections, the most isolated microorganisms were Enterobactriaceae (41%) (Table 2 ).

Table 2. Sites of infections and isolated microorganisms.

|

Infections characteristics |

n (%) |

|

Sites of infection |

2012 (100) |

|

Skin and soft tissues |

555 (28) |

|

Urinary tract |

277 (14) |

|

Upper respiratory tract |

159 (8) |

|

Lower respiratory tract |

159 (8) |

|

Osteoarticular |

159 (8) |

|

Neuromeningeal |

141 (7) |

|

Gastrointestinal / hepatic |

91 (4) |

|

Brucellosis / tuberculosis |

83 (4) |

|

Others |

388 (19) |

|

Microbiologically confirmed infections |

719 (100) |

|

Bacterial |

586 (82) |

|

Enterobacteriaceae |

296 (41) |

|

Pseudomonas aeruginosa / Acinetobacter baumannii |

91 (12) |

|

Staphylococcus aureus |

90 (12) |

|

Streptococcus spp |

21 (3) |

|

Enterococcus spp |

20 (3) |

|

Others |

68 (9) |

|

Fungal |

74 (10) |

|

Viral |

43 (6) |

|

Parasitic |

16 (2) |

When AST intervention was help to antibiotic therapy or help to diagnosis (N=2363), it consisted of further investigations in 388 cases (16%), antibiotic de-escalation in 251 cases (11%), no antibiotic prescription in 212 cases (9%), and antibiotic discontinuation in 187 cases (8%). Thus, antibiotic use reduction was made in 1038 cases (44%) (Table 3 ).

Table 3. Interventions of the antibiotic stewardship team onantibiotic use.

|

Characteristics |

n (%) |

|

Antibiotic use reduction |

1038 (44) |

|

Further investigations |

388 (16) |

|

Antibiotic change / de-escalation |

251 (11) |

|

No antibiotic |

212 (9) |

|

Antibiotic discontinuation |

187 (8) |

|

No antibiotic use reduction |

1325 (56) |

|

Antibiotic prescription |

605 (26) |

|

Continuation of the same antibiotic |

364 (15) |

|

Antibiotic change / wider spectrum |

190 (8) |

|

Other anti infectious prescription |

132 (6) |

|

Antifungal |

74 (3) |

|

Antiviral |

43 (2) |

|

Antiparasitic |

16 (1) |

|

Antibiotic change / same spectrum |

34 (1) |

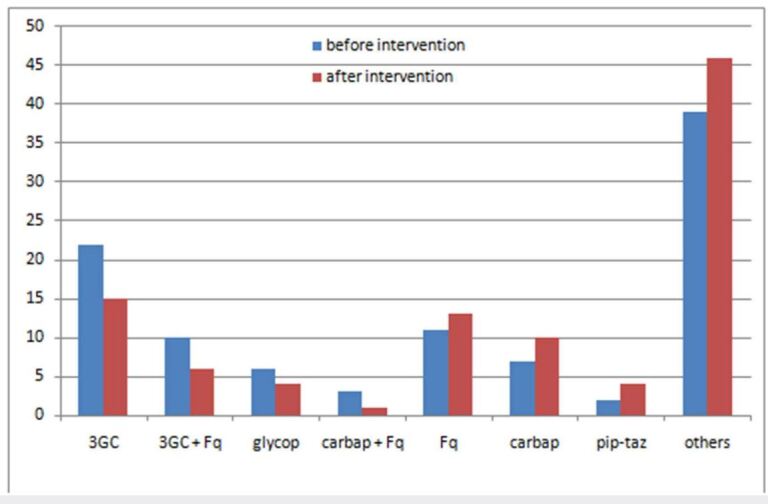

In cases where antibiotics have been changed (N=475), intervention of the AST was associated with an overall decrease in the prescription of broad-spectrum antibiotics from 61% to 50% (p=0,02), with a decrease in the prescription of third-generation cephalosporins from 22 to 15% (p=0,31) (Figure 3 ).

Figure 3. Changes in antibiotic prescriptions after the antibiotic stewarship team intenventions.

3GC: third generation cephalosporins, Fq: fluoro quinolones, glycop: ghycopeptides, carbap: carbapenems, pip-taz: piperacillin-tazobactam.

DISCUSSION:

During the study period, 2514 interventions were made by AST. The majority of interventions were made in hospitalized patients (91%), university hospitals (86%) and medical wards (67%), while outpatients (9%), private clinics (11%), secondary/primary care settings (3%), surgical wards (29%) and ICUs (4%) were less frequently involved. The frequency of interventions in university hospitals especially Farhat HACHED hospital could be explained by their geographical proximity with AST members, but additional efforts should be undertaken to make more interventions in outpatients, secondary/primary care settings and private clinics. In a French study, university hospitals accounted for only 10% of the AST interventions, while non-university public hospitals and private clinics accounted for 52% and 38% of the interventions, respectively (14 ). Outpatient prescriptions comprise up to 60% of antibiotic use and an American study showed that 40% of outpatient antibiotic prescriptions were not indicated (15 ). This could be explained by demand from patients or their parents, uncertainty of diagnosis, delays in getting laboratory results and lack of guidelines ( 14, 15, 16 ).

Low involvement of surgical wards and especially of ICUs in AST interventions has been observed in several studies (17, 18, 19, 20).

Surgeons, who are primary caregivers of operated patients, may believe their opinions should count more than infectious diseases specialists whose interventions could be perceived as only consultative (17, 18). This could explain that surgeon compliance to antibiotic guidelines is low. However, the “Global Alliance for Infections in Surgery” (19) including experts from 87 countries worldwide has been recently founded to promote the rationale use of antimicrobials in surgical infections and showed that a surgeon was a component of AST in surgical departments in 59% of cases (19 ). Thus, a collaborative relationship based on education, mutual respect and willingness to compromise should be built between surgeons and other members of ASTs ( 19, 20).

In ICUs, over 70% of patients receive antibiotics (21 ). However, intervention of ASTs is limited because patients are critically ill, and broad-spectrum antibiotics are often prescribed empirically since shorter times to initiation of appropriate antibiotic therapy are associated with better outcomes (21 ). The best interventions to improve adherence to infectious diseases advices in ICUs are enabling interventions, while restrictive interventions are less effective (22, 23).

In this study, most interventions were made with medical trainees (48%) and via phone calls (44%), while complex cases were discussed with attending doctors after patient bedside assessment and within multidisciplinary meeting.

Although the most common intervention of AST was help to antibiotic therapy (80%), help to diagnosis and preventive interventions (i.e. vaccination and chemoprophylaxis) were made in 20% of cases and could be developed more.

The most common sites of infections were skin and soft tissues (28%), urinary tract (14%), upper respiratory tract (URT) (8%), lower respiratory tract (LRT) (8%), osteoarticular (8%) and neuromeningeal (7%), while ocular, pelvic and intra abdominal infections accounted together for only less than 5% of interventions. Based on these findings, AST interventions should be either consolidated or reinforced depending on the implications of different settings.

Among microbiologically documented infections (36%), Enterobactriaceae (41%) were the most commonly isolated followed by Pseudomonas aeruginosa /Acinetobacter baumannii (12%) and Staphylococcus aureus (12%). Gram negative bacilli were mainly isolated in urinary tract infections and Staphylococcus aureus in skin and soft tissue infections. By providing susceptibility testing of the isolated microorganism, the Microbiology laboratory played a key role in decreasing time to appropriate antibiotic therapy and consequently improving patient outcome (24 ). Fungal infections were not rare since they accounted for 10% of documented infections, which was underestimated since invasive fungal infections which occured mainly in Hematology and ICUs were most often managed by primary physicians without AST intervention. Antifungal stewardship should be reinforced since it has proven efficacy in limiting safely antifungal consumption and prescription of advanced antifungal agents such as B echinocandins, then reducing costs of care ( 25, 26).

In this study, AST interventions resulted in antibiotic use reduction including antibiotic discontinuation or de-escalation in almost half of cases (44%). For wide spectrum antibiotics, an overall decrease from 61 to 50% has been noted. This decrease concerned mainly third-generation cephalosporins and third- generation cephalosporin - fluoroquinolone combination prescription while an increase in fluoroquinolones and carbapenems prescription has been noted. The prescription of wider spectrum antibiotics should improve the outcome in patients with severe infections or documented infections with multidrug resistant organisms.

Several studies have demonstrated that implementation of ASPs in care settings shortened length of stay, improved appropriate use of antibiotics and reduced overall antibiotic prescribing and prescription of broad spectrum antibiotics such as third-generation cephalosporins, fluoroquinolones and carbapenems (27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32).

This study is a pilot Tunisian study which provided data based on a high number of interventions during a long period of time. However, it has some limitations. It was a monocentric study, most interventions were limited to the two university hospitals of the region, the application of AST interventions by primary care physicians was not followed and the impact of interventions on antibiotic resistance, mortality or cost of care was not measured. More efforts including educational meetings and implementation of multidisciplinary practice guidelines should be made to improve the impact of AST interventions.

CONCLUSION:

The present study reported that the majority of AST interventions were made in hospitalized patients, university hospitals and medical wards. These interventions resulted in an overall and broad-spectrum antibiotic use reduction, but their impact on antibiotic resistance, mortality or cost of care was not measured. To contribute to the national ASP, more efforts should be made to reinforce AST interventions in secondary/primary care settings, outpatients, surgical wards and ICUs.

References

- O’Neill Jim, et al. Antimicrobial resistance: tackling a crisis for the health and wealth of nations. 4. Vol. 2014. Wellcome Trust & HM Government London; 2014. Review on antimicrobial resistance. [Google Scholar]

- Klein Eili Y, Van Boeckel Thomas P, Martinez Elena M, Pant Suraj, Gandra Sumanth, Levin Simon A, Goossens Herman, Laxminarayan Ramanan. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 15. Vol. 115. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences; 2018. Global increase and geographic convergence in antibiotic consumption between 2000 and 2015; pp. 3463–3470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mansour W. African Health Sciences. 4. Vol. 18. African Journals Online (AJOL); 2018. Tunisian antibiotic resistance problems: three contexts but one health; pp. 1202–1203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E.coli Antibiotic resistance in Tunisia. https://www.infectiologie.org.tn/pdf_ppt_docs/ resistance/1544218181.pdf on June 21st 2022. LART : Data from 2017. [Google Scholar]

- E.coli, pneumoniae Antibiotic resistance in Tunisia. https://www.infectiologie.org.tn/pdf_ ppt_docs/resistance/1544218300.pdf on June 21st 2022. LART: Data from 2017. 2017 [Google Scholar]

- E. faecium. Antibiotic resistance in Tunisia. https://www.infectiologie.org.tn/pdf_ppt_docs/ resistance/1544218337.pdf on June 21st 2022. LART: Data from 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Knight Joshua, Michal Jessica, Milliken Stephanie, Swindler Jenna. Pharmacy. 1. Vol. 8. MDPI AG; 2020. Effects of a Remote Antimicrobial Stewardship Program on Antimicrobial Use in a Regional Hospital System; pp. 41–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antimicrobial stewardship: promoting antimicrobial stewardship in human medicine. https://www.idsociety. org/policyadvocacy/antimicrobialresistance/antimicrobialstewardship/on July 10th 2020. https://www.idsociety. org/policyadvocacy/antimicrobialresistance/antimicrobialstewardship/on July 10th 2020.

- Yamada Koichi, Imoto Waki, Yamairi Kazushi, Shibata Wataru, Namikawa Hiroki, Yoshii Naoko, Fujimoto Hiroki, Nakaie Kiyotaka, Okada Yasuyo, Fujita Akiko, Kawaguchi Hiroshi, Shinoda Yoshikatsu, Nakamura Yasutaka, Kaneko Yukihiro, Yoshida Hisako, Kakeya Hiroshi. Journal of Infection and Chemotherapy. 12. Vol. 25. Elsevier BV; 2019. The intervention by an antimicrobial stewardship team can improve clinical and microbiological outcomes of resistant gram-negative bacteria; pp. 1001–1006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huebner C, Flessa S, Huebner NO. Journal of Hospital Infection. 4. Vol. 102. Elsevier; 2019. The economic impact of antimicrobial stewardship programmes in hospitals: a systematic literature review; pp. 369–376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fishman Neil, for Healthcare Epidemiology of America Society, of America Infectious Diseases Society. Infection Control & Hospital Epidemiology. 4. Vol. 33. Cambridge University Press; 2012. Policy statement on antimicrobial stewardship by the society for healthcare epidemiology of America (SHEA), the infectious diseases society of America (IDSA), and the pediatric infectious diseases society (PIDS) pp. 322–327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The evolving threat of antimicrobial resistance: options for action. Geneva: World Health Organization. 2012. https:// apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/44812 https:// apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/44812

- National action plan against antimicrobial resistance in Tunisia 2019-2023. http://www.santetunisie.rns.tn/images/ docs/anis/actualite/2019/dec/PAN-TUNISIE-2019-2023.pdf http://www.santetunisie.rns.tn/images/ docs/anis/actualite/2019/dec/PAN-TUNISIE-2019-2023.pdf

- F Binda, G Tebano, MC Kallen. Nationwide survey of hospital antibiotic stewardship programs in France. Med Mal Infect. 2019 doi: 10.1016/j.medmal.2019.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White Alexis T, Clark Collin M, Sellick John A, Mergenhagen Kari A. American Journal of Infection Control. 8. Vol. 47. Elsevier BV; 2019. Antibiotic stewardship targets in the outpatient setting; pp. 858–863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabba John Alimamy, Tadesse Nigatu, James Peter Bai, Kallon Herbart, Kitchen Chenai, Atif Naveel, Jiang Minghuan, Hayat Khezar, Zhao Mingyue, Yang Caijun, Chang Jie, Fang Yu. Transactions of The Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 6. Vol. 114. Oxford University Press (OUP); 2020. Knowledge, attitude and antibiotic prescribing patterns of medical doctors providing free healthcare in the outpatient departments of public hospitals in Sierra Leone: a national cross-sectional study; pp. 448–458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson Evan D, Volles David F, Kramme Katherine, Mathers Amy J, Sawyer Robert G. Infectious Disease Clinics of North America. 1. Vol. 34. Elsevier BV; 2020. Collaborative Antimicrobial Stewardship for Surgeons; pp. 97–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duane Therese M, Zuo Jessica X, Wolfe Luke G, Bearman Gonzalo, Edmond Michael B, Lee Kimberly, Cooksey Laurie, Stevens Michael P. The American Surgeon. 12. Vol. 79. SAGE Publications; 2013. Surgeons Do Not Listen: Evaluation of Compliance with Antimicrobial Stewardship Program Recommendations; pp. 1269–1272. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sartelli Massimo, Labricciosa Francesco M, Barbadoro Pamela, Pagani Leonardo, Ansaloni Luca, Brink Adrian J, Carlet Jean, Khanna Ashish, Chichom-Mefire Alain, Coccolini Federico, Di Saverio Salomone, May Addison K, Viale Pierluigi, Watkins Richard R, Scudeller Luigia, Abbo Lilian M, Abu-Zidan Fikri M, Adesunkanmi Abdulrashid K, Al-Dahir Sara, Al-Hasan Majdi N, Alis Halil, Alves Carlos, Araujo Da Silva André R, Augustin Goran, Bala Miklosh, Barie Philip S, Beltrán Marcelo A, Bhangu Aneel, Bouchra Belefquih, Brecher Stephen M, Caínzos Miguel A, Camacho-Ortiz Adrian, Catani Marco, Chandy Sujith J, Jusoh Asri Che, Cherry-Bukowiec Jill R, Chiara Osvaldo, Colak Elif, Cornely Oliver A, Cui Yunfeng, Demetrashvili Zaza, De Simone Belinda, De Waele Jan J, Dhingra Sameer, Di Marzo Francesco, Dogjani Agron, Dorj Gereltuya, Dortet Laurent, Duane Therese M, Elmangory Mutasim M, Enani Mushira A, Ferrada Paula, Esteban Foianini J, Gachabayov Mahir, Gandhi Chinmay, Ghnnam Wagih Mommtaz, Giamarellou Helen, Gkiokas Georgios, Gomi Harumi, Goranovic Tatjana, Griffiths Ewen A, Guerra Gronerth Rosio I, Haidamus Monteiro Julio C, Hardcastle Timothy C, Hecker Andreas, Hodonou Adrien M, Ioannidis Orestis, Isik Arda, Iskandar Katia A, Kafil Hossein S, Kanj Souha S, Kaplan Lewis J, Kapoor Garima, Karamarkovic Aleksandar R, Kenig Jakub, Kerschaever Ivan, Khamis Faryal, Khokha Vladimir, Kiguba Ronald, Kim Hong B, Ko Wen-Chien, Koike Kaoru, Kozlovska Iryna, Kumar Anand, Lagunes Leonel, Latifi Rifat, Lee Jae G, Lee Young R, Leppäniemi Ari, Li Yousheng, Liang Stephen Y, Lowman Warren, Machain Gustavo M, Maegele Marc, Major Piotr, Malama Sydney, Manzano-Nunez Ramiro, Marinis Athanasios, Martinez Casas Isidro, Marwah Sanjay, Maseda Emilio, Mcfarlane Michael E, Memish Ziad, Mertz Dominik, Mesina Cristian, Mishra Shyam K, Moore Ernest E, Munyika Akutu, Mylonakis Eleftherios, Napolitano Lena, Negoi Ionut, Nestorovic Milica D, Nicolau David P, Omari Abdelkarim H, Ordonez Carlos A, Paiva José-Artur, Pant Narayan D, Parreira Jose G, Pędziwiatr Michal, Pereira Bruno M, Ponce-De-Leon Alfredo, Poulakou Garyphallia, Preller Jacobus, Pulcini Céline, Pupelis Guntars, Quiodettis Martha, Rawson Timothy M, Reis Tarcisio, Rems Miran, Rizoli Sandro, Roberts Jason, Pereira Nuno Rocha, Rodríguez-Baño Jesús, Sakakushev Boris, Sanders James, Santos Natalia, Sato Norio, Sawyer Robert G, Scarpelini Sandro, Scoccia Loredana, Shafiq Nusrat, Shelat Vishalkumar, Sifri Costi D, Siribumrungwong Boonying, Søreide Kjetil, Soto Rodolfo, De Souza Hamilton P, Talving Peep, Trung Ngo Tat, Tessier Jeffrey M, Tumbarello Mario, Ulrych Jan, Uranues Selman, Van Goor Harry, Vereczkei Andras, Wagenlehner Florian, Xiao Yonghong, Yuan Kuo-Ching, Wechsler-Fördös Agnes, Zahar Jean-Ralph, Zakrison Tanya L, Zuckerbraun Brian, Zuidema Wietse P, Catena Fausto. World Journal of Emergency Surgery. 1. Vol. 12. Springer Science and Business Media LLC; 2017. The Global Alliance for Infections in Surgery: defining a model for antimicrobial stewardship—results from an international cross-sectional survey; pp. 34–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charani E, Tarrant C, Moorthy K, Sevdalis N, Brennan L, Holmes A H. Clinical Microbiology and Infection. 10. Vol. 23. Elsevier BV; 2017. Understanding antibiotic decision making in surgery—a qualitative analysis; pp. 752–760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wunderink Richard G, Srinivasan Arjun, Barie Philip S, Chastre Jean, Dela Cruz Charles S, Douglas Ivor S, Ecklund Margaret, Evans Scott E, Evans Scott R, Gerlach Anthony T. Annals of the American Thoracic Society. 5. Vol. 17. American Thoracic Society; 2020. Antibiotic stewardship in the intensive care unit. An official American Thoracic Society Workshop Report in collaboration with the AACN, CHEST, CDC, and SCCM; pp. 531–540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abbara S, Domenech De Cellès M, Batista R, Mira J P, Poyart C, Poupet H, Casetta A, Kernéis S. Journal of Hospital Infection. 2. Vol. 104. Elsevier BV; 2020. Variable impact of an antimicrobial stewardship programme in three intensive care units: time-series analysis of 2012–2017 surveillance data; pp. 150–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rynkiewich K, Schwartz D, Won S, Stoner B. Journal of Hospital Infection. 2. Vol. 104. Elsevier BV; 2020. Antibiotic decision making in surgical intensive care: a qualitative analysis; pp. 158–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palavecino E L, Williamson J C, Ohl C A. Collaborative Antimicrobial Stewardship: Working with Microbiology. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2020;34(1):51–65. doi: 10.1016/j.idc.2019.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ioannidis Konstantinos, Papachristos Apostolos, Skarlatinis Ioannis, Kiospe Fevronia, Sotiriou Sotiria, Papadogeorgaki Eleni, Plakias George, Karalis Vangelis D, Markantonis Sophia L. European Journal of Hospital Pharmacy. 1. Vol. 27. BMJ; 2020. Do we need to adopt antifungal stewardship programmes? pp. 14–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martín-Gutiérrez G, Peñalva G, Ruiz-Pérez De Pipaón M. Efficacy and Safety of a Comprehensive Educational Antimicrobial Stewardship Program Focused on Antifungal Use. J Infect. 2020;80(3):342–351. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alshareef Hanan, Alfahad Wafa, Albaadani Abeer, Alyazid Huda, Talib Ruba Bin. Journal of Infection and Public Health. 7. Vol. 13. Elsevier BV; 2020. Impact of antibiotic de-escalation on hospitalized patients with urinary tract infections: A retrospective cohort single center study; pp. 985–990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kissler Stephen M, Klevens R Monina, Barnett Michael L, Grad Yonatan H. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 9. Vol. 72. Oxford University Press (OUP); 2021. Distinguishing the Roles of Antibiotic Stewardship and Reductions in Outpatient Visits in Generating a 5-Year Decline in Antibiotic Prescribing; pp. 1568–1576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lester Rebecca, Haigh Kate, Wood Alasdair, Macpherson Eleanor E, Maheswaran Hendramoorthy, Bogue Patrick, Hanger Sofia, Kalizang’oma Akuzike, Srirathan Vinothan, Kulapani David, Mallewa Jane, Nyirenda Mulinda, Jewell Christopher P, Heyderman Robert, Gordon Melita, Lalloo David G, Tolhurst Rachel, Feasey Nicholas A. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 9. Vol. 71. Oxford University Press (OUP); 2020. Sustained Reduction in Third-generation Cephalosporin Usage in Adult Inpatients Following Introduction of an Antimicrobial Stewardship Program in a Large, Urban Hospital in Malawi; pp. 478–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolla C, Di Pietrantonj C, Ferrando E, Pernecco A, Salerno A, D’orsi M, Chichino G. Médecine et Maladies Infectieuses. 4. Vol. 50. Elsevier BV; 2020. Example of antimicrobial stewardship program in a community hospital in Italy; pp. 342–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faraone Antonio, Poggi Alice, Cappugi Chiara, Tofani Lorenzo, Riccobono Eleonora, Giani Tommaso, Fortini Alberto. European Journal of Internal Medicine. 20. Vol. 78. Elsevier BV; 2020. Inappropriate use of carbapenems in an internal medicine ward: Impact of a carbapenem-focused antimicrobial stewardship program; pp. 50–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuruc P D, Mađarić V, Poje Janeš, Kifer V, Howard D, Marušić P, S. Antimicrobial stewardship effectiveness on rationalizing the use of last line of antibiotics in a short period with limited human resources: a single centre cohort study. BMC Res Notes. 2019;12(1):531–531. doi: 10.1186/s13104-019-4572-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]