Abstract

Stillbirth is a recognized complication of COVID-19 in pregnant women that has recently been demonstrated to be caused by SARS-CoV-2 infection of the placenta. Multiple global studies have found that the placental pathology present in cases of stillbirth consists of a combination of concurrent destructive findings that include increased fibrin deposition that typically reaches the level of massive perivillous fibrin deposition, chronic histiocytic intervillositis, and trophoblast necrosis. These 3 pathologic lesions, collectively termed SARS-CoV-2 placentitis, can cause severe and diffuse placental parenchymal destruction that can affect >75% of the placenta, effectively rendering it incapable of performing its function of oxygenating the fetus and leading to stillbirth and neonatal death via malperfusion and placental insufficiency. Placental infection and destruction can occur in the absence of demonstrable fetal infection. Development of SARS-CoV-2 placentitis is a complex process that may have both an infectious and immunologic basis. An important observation is that in all reported cases of SARS-CoV-2 placentitis causing stillbirth and neonatal death, the mothers were unvaccinated. SARS-CoV-2 placentitis is likely the result of an episode of SARS-CoV-2 viremia at some time during the pregnancy. This article discusses clinical and pathologic aspects of the relationship between maternal COVID-19 vaccination, SARS-CoV-2 placentitis, and perinatal death.

Key words: COVID-19 in pregnancy, COVID-19 vaccine, massive perivillous fibrin deposition, maternal-fetal tolerance, maternal vaccination, maternal viremia, perinatal death, placental insufficiency, placental malperfusion, placental pathology, SARS-CoV-2 placentitis, stillbirth, stillbirth prevention

Introduction

Since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic in early 2020, pregnancy has been associated with an emerging number of complications and adverse clinical outcomes for the mother, fetus, and neonate. An investigation of 869,079 pregnant women seen at 499 hospitals in the United States between March 1, 2020 and February 28, 2021 found that those with SARS-CoV-2 infection were more likely to have preterm delivery, require intensive care, intubation, and mechanical ventilation, and have a fatal hospital outcome compared with uninfected pregnant women.1 Although stillbirth was suspected of being a potential outcome of maternal infection with SARS-CoV-2, published data from the early phases of the pandemic were not definitive in demonstrating an etiologic relationship.2 Then in April 2021, a report from Ireland described a temporal cluster of 6 stillbirths and 1 miscarriage in County Cork from pregnant women with COVID-19.3 When the placentas from these stillborn fetuses were examined by Fitzgerald et al,4 they were found to be infected with SARS-CoV-2 and severely compromised because of fibrin deposition, intervillositis, and necrosis. A May 2021 study in England reported the analysis of a national database of 342,080 pregnant women, among whom 3527 had COVID-19, and higher rates of fetal death among those infected with SARS-CoV-2 than among uninfected mothers.5 On November 26, 2021, the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) confirmed the association of SARS-CoV-2 infection with stillbirth in a population-based study of 1,249,634 delivery hospitalizations. This investigation demonstrated that pregnant women with COVID-19 had an increased risk for stillbirth compared to uninfected women; the strength of this of association was greatest during the surge of the SARS-CoV-2 Delta (B.1.617.2) variant (pre-Delta adjusted relative risk [aRR], 1.47; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.27–1.71; Delta period aRR, 4.04; 95% CI, 3.28–4.97).6

Chronic histiocytic intervillositis and increased and massive perivillous fibrin deposition in the placenta before the pandemic

Even before the COVID-19 pandemic, both chronic histiocytic intervillositis (CHIV) and increased and massive perivillous fibrin deposition (MPFD) had been observed to occur in the placentas of newborns with perinatal complications and adverse clinical outcomes.7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13

CHIV is a microscopic abnormality that was rarely observed in placentas before the COVID-19 pandemic, present in <1% of pregnancies. Characterized by diffuse inflammatory infiltration of the intervillous space which consists predominantly of mononuclear inflammatory cells termed histiocytes, Labarre and Mullen were the first to identify it as a discrete abnormality in 1987 and termed it massive chronic intervillositis.14 Describing the intervillous infiltration of mononuclear cells in the placenta accompanied by fibrin deposits and trophoblast necrosis,14 they hypothesized that it could represent an extreme variant of villitis of unknown etiology (VUE). Since then, the lesion has been termed in the literature variously as “intervillitis,” “chronic histiocytic intervillositis of unknown etiology,” “chronic intervillositis,” “massive chronic intervillositis,” “chronic histiocytic intervillositis,” “chronic intervillositis of unknown etiology,” “massive perivillous histiocytosis,” and “massive histiocytic chronic intervillositis.”15 , 16 CHIV is frequently accompanied by increased fibrin deposition,7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13 , 17 which in some cases can be severe enough to constitute MPFD. CHIV can resemble processes observed in infections such as the chronic stage of placental malaria, where accumulations of histiocytes in the intervillous space can develop.18 Although malaria is endemic in some regions affected by COVID-19,19 placentas affected by malaria will also typically demonstrate Plasmodium–parasitized red blood cells and hemozoin pigment in the intervillous space, without prominent fibrin deposition or trophoblast necrosis. It was recognized long before COVID-19 that intervillositis is a potentially serious placental abnormality, not only causing intrauterine growth restriction, miscarriage, and stillbirth, but also having a substantial risk of recurrence.7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13 , 17 Cases of CHIV were also described occurring with chronic villitis, a microscopic abnormality in which the chorionic villi are infiltrated by lymphocytes, plasma cells, and/or histiocytes, and which can result from TORCH (toxoplasmosis, other, rubella, cytomegalovirus, herpes) infections.16 A recent hypothesis has suggested that CHIV could be linked with anti–human leukocyte antigen alloimmunization, as could be observed in graft rejection.20

Similar to intervillositis, MPFD was recognized long before the COVID-19 pandemic as a cause of perinatal morbidity and mortality owing to fetal hypoxic injury that results in spontaneous abortion, intrauterine growth restriction, preterm delivery, stillbirth, neonatal death, and neurologic disease in surviving infants, along with its substantial risk for recurrence.21, 22, 23 The characteristic features of MPFD include extensive and confluent deposition of fibrin/fibrinoid material within the intervillous space that obstructs maternal perfusion and gas–nutrient exchange, encases the chorionic villi, and causes villous ischemia and necrosis that eventually result in placental insufficiency.21, 22, 23 Even before the current COVID-19 pandemic, MPFD has been reported in autopsied infants whose cause of death was placental insufficiency. Although MPFD is technically not an inflammatory disorder, it has commonly occurred together with chronic inflammatory conditions including CHIV and villitis.

SARS-CoV-2 placentitis and the importance of pathology in understanding the mechanisms of stillbirth from COVID-19

The role of pathology in revealing substantial information on the effects of SARS-CoV-2 on the placenta and the mechanisms of fetal demise has reinforced the advantages of submitting for examination placentas from infected mothers with adverse perinatal outcomes. Multiple studies of placentas infected with SARS-CoV-2 have identified a grouping of unusual pathologic abnormalities that can be present in both live-born and stillborn infants.24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30 These findings include increased perivillous fibrin deposition that, in most cases, reaches the extent of MPFD (Figures 1 and 2 ); trophoblast necrosis (Figure 2); and CHIV (Figures 2 and 3 ). Both MPFD and CHIV were rarely observed in placentas before the COVID-19 pandemic. The simultaneous finding of these 3 abnormalities in infected placentas from mothers with COVID-19 has been termed “SARS-CoV-2 placentitis” by Watkins et al.29 Syncytiotrophoblast is the most common placental cell type to be infected with SARS-CoV-2 (Figure 4 ),2 although the virus has now been identified in all cells of the chorionic villi. To determine the cause of perinatal deaths occurring in pregnant women with COVID-19, Schwartz et al31 examined a cohort of placentas infected with SARS-CoV-2 from 64 stillborn fetuses and 4 early neonatal deaths from 12 countries. Findings from this investigation demonstrated that all 68 placentas had severe destructive pathology from the constituents of SARS-CoV-2 placentitis, and that there was coexistent CHIV, increased fibrin deposition, and trophoblast necrosis in 97% of placentas. A striking finding was that the average infected placenta had 77.7% tissue destruction resulting from widespread involvement with SARS-CoV-2 placentitis, with many placentas having >90% of the parenchyma destroyed. This extent of placental destruction substantially impedes delivery of adequate oxygen and nutrients to the fetus and is incompatible with fetal survival. Another important finding in this study was that although SARS-CoV-2 was identified in perinatal body specimens in 16 of 28 (57%) cases tested, and autopsies were performed on 29 stillborn fetuses and 1 neonate, there was no evidence that perinatal mortality was induced by direct viral infection of fetal organs. Instead, the tissue damage seemed to be confined to the placenta, where it was extensive and highly destructive in all 68 cases. The authors concluded that placental insufficiency from SARS-CoV-2 placentitis and consequent severe fetal hypoxia produced a hypoxic-ischemic fetal or neonatal demise. This mechanism of fetal death is not typical of intrauterine infections, which typically result in stillbirth from direct damage to the fetal somatic organs. Similar results to these by Schwartz et al31 were found in subsequent investigations of stillbirth. In Sweden, Zaigham et al32 reported 5 stillborn fetuses from mothers having COVID-19 in which all placentas were infected with SARS-CoV-2 and had concomitant SARS-CoV-2 placentitis. A report from Greece by Konstantinidou et al33 described 6 stillborn fetuses from mothers having SARS-CoV-2 infection during pregnancy, with placentas afflicted with SARS-CoV-2 placentitis. Two of the mothers were asymptomatic and 4 had only mild symptoms, with stillbirth occurring from 3 to 15 days after the initial maternal COVID-19 diagnosis. In all 6 placentas there was MPFD that involved between 75% and 90% of the parenchyma. None of the 6 fetuses were found to be infected with SARS-CoV-2, and all 3 of the autopsies performed showed evidence of asphyxia. A common factor among the reports of SARS-CoV-2 placentitis causing perinatal deaths, including those from Schwartz et al,31 Zaigham et al,32 Konstantinidou et al,33 and Fitzgerald et al,4 was that in all cases the mothers were unvaccinated against COVID-19.

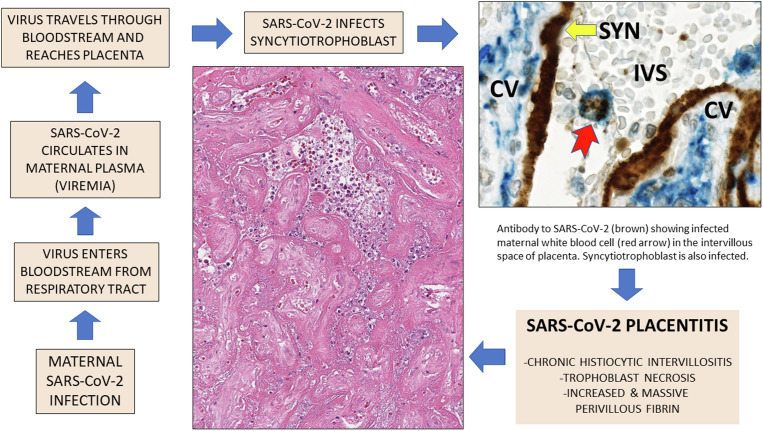

Figure 1.

Gross appearance of a sectioned placenta with SARS-CoV-2 placentitis

Massive perivillous fibrin deposition involves most of the placental parenchyma.

Schwartz. Placentitis, stillbirth, and maternal COVID-19 vaccination. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2023.

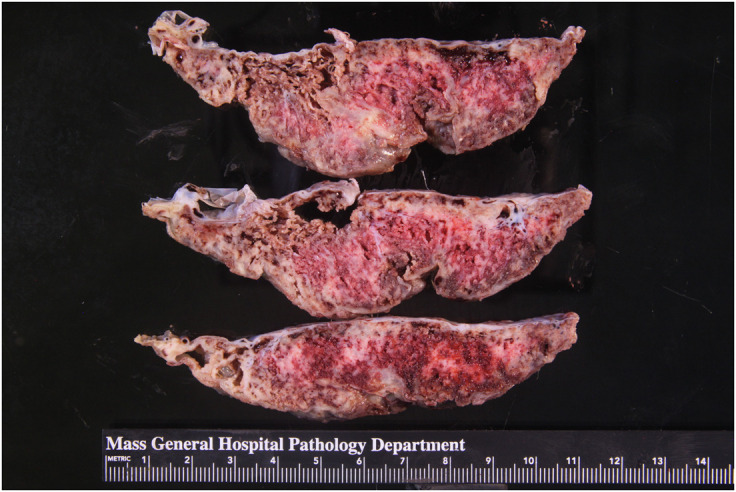

Figure 2.

Placenta with SARS-CoV-2 placentitis and MPFD from a stillborn fetus

Microscopic image. Fibrin has completely obstructed the intervillous space, and there is severe ischemic necrosis of the chorionic villi. Hematoxylin and eosin staining, ×10.

MPFD, massive perivillous fibrin deposition.

Schwartz. Placentitis, stillbirth, and maternal COVID-19 vaccination. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2023.

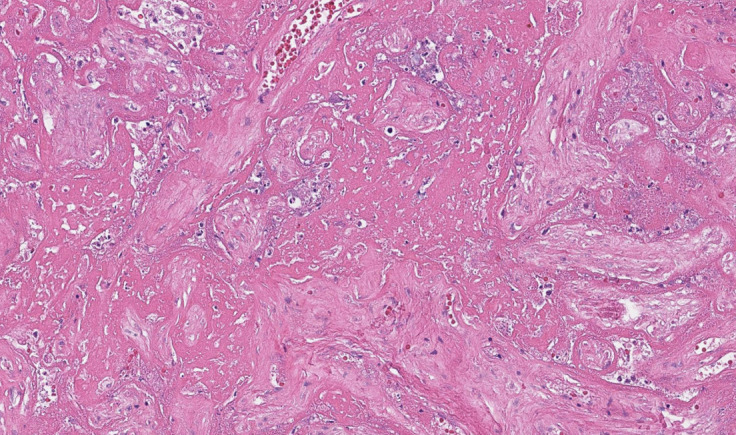

Figure 3.

A placenta exhibiting SARS-CoV-2 placentitis

Massive perivillous fibrin deposition is present, in which the intervillous space is completely obstructed with fibrin, remnants of histiocytes, and cellular and karyorrhectic debris, preventing maternal blood flow and oxygen delivery to the villi. The syncytiotrophoblast is necrotic, and there is chronic histiocytic intervillositis. Hematoxylin and eosin staining, ×10.

Photograph courtesy of Fabio Facchetti, MD, PhD, Pathology Unit, Department of Molecular and Translational Medicine, Università degli Studi di Brescia, Brescia, Italy.

Schwartz. Placentitis, stillbirth, and maternal COVID-19 vaccination. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2023.

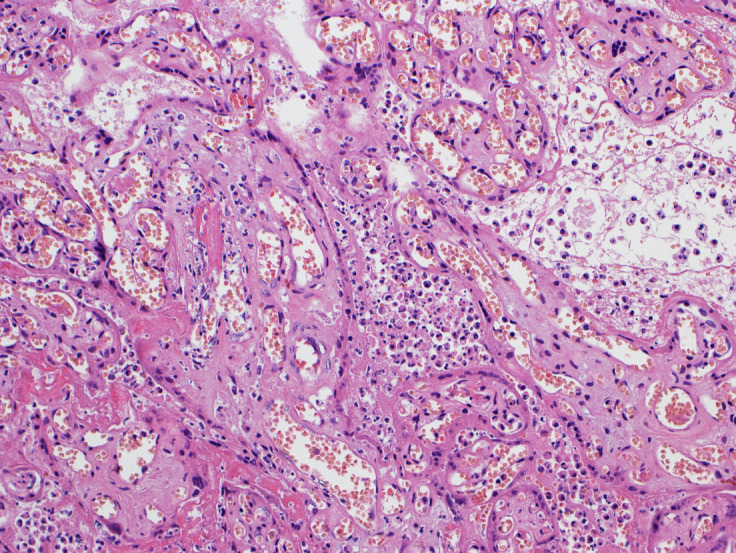

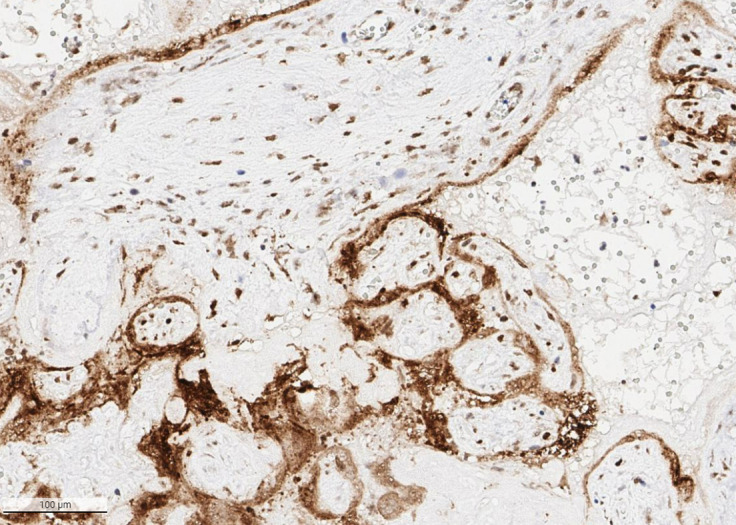

Figure 4.

Placenta from a stillborn preterm fetus with SARS-CoV-2 placentitis

Immunohistochemistry demonstrates intense positivity for SARS-CoV-2 spike antigen in the syncytiotrophoblast and villous stromal cells. Antibody to SARS-CoV-2 spike protein, ×20.

Schwartz. Placentitis, stillbirth, and maternal COVID-19 vaccination. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2023.

These studies and others indicate that one mechanism of fetal and neonatal mortality from maternal COVID-19 involves the development of placental infection causing SARS-CoV-2 placentitis and placental insufficiency.2 As SARS-CoV-2 infection of the placenta evolves, increasingly severe parenchymal ischemia occurs, in which fibrin deposition and/or MPFD, trophoblast necrosis, and CHIV obstruct maternal perfusion in the intervillous space, leading to progressive destruction of the tissue and malperfusion. SARS-CoV-2 placentitis is often accompanied by other placental abnormalities that contribute to malperfusion; these include thrombohematomas, villitis, and findings of maternal and fetal vascular malperfusion.30, 31, 32 , 34 The resulting placental insufficiency in severe cases causes hypoxemic ischemic injury to the vital organs of the fetus, resulting in intrauterine fetal death or neonatal demise.2 , 31 An interesting and as yet unexplained observation from these reported cases is that there seems to be little correlation between the severity of maternal disease, placental infection, and stillbirth. In fact, some cases of SARS-CoV-2 placentitis and stillbirth occur in asymptomatic women, a dichotomy which has yet to be understood.

SARS-CoV-2 placentitis and SARS-CoV-2 viremia

Placentas having SARS-CoV-2 placentitis generally demonstrate unusually intense and diffuse positivity for viral antigens and nucleic acids according to immunohistochemistry and nucleic acid hybridization methods when compared with other viral infections.4 , 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30 It has been assumed that SARS-CoV-2 reaches the placenta via the maternal bloodstream, a process termed “hematogenous transmission,” which is characteristic of not only viral but also many bacterial and parasitic agents that can cause intrauterine infection.35 , 36 As a result of maternal viremia, TORCH agents including viruses such as Ebola virus, Lassa virus, parvovirus B19, Zika virus, and others can reach the maternal-fetal interface to infect the placenta and, in many cases, the fetus.37 SARS-CoV-2 is the newest TORCH virus,38 and although there are currently no data to confirm this, it is highly probable that it reaches the placenta via the hematogenous route following an episode(s) of maternal viremia as occurs with other TORCH viruses (Figure 5 ).2 , 25 , 31

Figure 5.

Proposed mechanisms of development of placental infection and SARS-CoV-2 placentitis

Proposed mechanisms of placental infection with SARS-CoV-2 following maternal viremia and development of SARS-CoV-2 placentitis. The high magnification photograph of placenta in the upper right demonstrates a maternal white blood cell, probably a macrophage, staining for SARS-CoV-2 using immunohistochemistry and circulating in the intervillous space, adjacent to the infected syncytiotrophoblast.

CV, chorionic villus; IVS, intervillous space; SYN, syncytiotrophoblast.

Schwartz. Placentitis, stillbirth, and maternal COVID-19 vaccination. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2023.

The precise mechanisms involved in the development of SARS-CoV-2 placentitis are not well understood. However, it is generally believed that placental disease is initiated by SARS-CoV-2 infection of the syncytiotrophoblast and cytotrophoblast, triggering complement activation and subsequent cytokine up-regulation recruiting maternal monocytes to the area of infection. Syncytiotrophoblast necrosis occurs, which is not only the result of direct viral infection but also partially owing to complement activation and irreversible damage to the microvillous apical border of these cells, and which eventually involves the cytotrophoblast. Cytokines in the area of tissue damage result in a procoagulant microenvironment, eliciting fibrin deposition that typically reaches the level of MPFD, and SARS-CoV-2 placentitis.29 , 39 , 40 Necrosis of the infected trophoblast, the primary protective cell layer of the maternal-fetal interface, may in some cases permit viral entry into the villous stroma and chorionic vasculature. Supporting this is the pathology demonstration of SARS-CoV-2 in not only syncytiotrophoblast but also in cytotrophoblast, villous stromal and Hofbauer cells, and villous capillary endothelium.30 , 41 , 42

Similar to other respiratory viruses such as influenza viruses, SARS-CoV-1, adenoviruses, and respiratory syncytial virus, SARS-CoV-2 can be detected in the human bloodstream, which is a finding that has been termed both “viremia” and “RNAemia.”43, 44, 45 SARS-CoV-2 viremia and systemic dissemination, as demonstrated by levels of plasma RNAemia, are associated with increased severity of tissue damage, endothelial inflammation, elevation in levels of inflammatory biomarkers, a hyperinflammatory state, and coagulopathies, and can predict the risk of eventual disease severity and death.46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52 Further support for bloodstream dissemination of SARS-CoV-2 to extrapulmonary organs has been provided by autopsy studies that have identified the virus in multiple tissues including lymphatic, cardiovascular, gastrointestinal, endocrine, reproductive organ, liver, bone marrow, urinary tract, and of course placental tissue, where it can be associated with organ malfunction and pathology.1 , 43, 44, 45 SARS-CoV-2 viremia is associated with complement system activation and elevated proinflammatory cytokine levels, which may explain many of the destructive effects that occur in extrapulmonary organs including the placenta.29 , 43 , 45 , 47 , 53 Both the development and effects of SARS-CoV-2 viremia are likely dependent on multiple factors such as genetics, immunocompetence, comorbidities, history of COVID-19 infection, vaccination status, viral factors, and other covariables. In nonpregnant adults, the detection of SARS-CoV-2 viremia/RNAemia is associated with worse disease outcomes, including increased probability of progression to severe disease, higher levels of interleukin (IL)-6, IL-5, or C-X-C motif chemokine ligand (CXCL) 10, acute respiratory distress syndrome, intensive care unit (ICU) admission, critical disease, and death in hospitalized patients.43 , 54, 55, 56 A proteomic study by Li et al47 demonstrated that SARS-CoV-2 viremia was not only associated with severe disease and death, but also with up-regulation of SARS-CoV-2 cell entry factors, increased levels of markers of damage to the lungs, gastrointestinal tract, endothelium, and blood vessels, and alterations in coagulation pathways that were predictive of clinical outcomes.

The identification of SARS-CoV-2 plasma viremia can be affected by factors that include symptom duration, disease severity, and test sensitivity.43 The incidence of viremia among nonpregnant persons with COVID-19 varies between studies, with reported figures of 2% among infected outpatients, 6% among persons presenting to the emergency department, 47% among hospitalized patients, and up to 100% among patients in the ICU.53 , 57

Data on the incidence of SARS-CoV-2 viremia and RNAemia in pregnant women with COVID-19 are scant, and suggest that the occurrence of the virus in the bloodstream during pregnancy is an unusual or transient event that is difficult to capture in this population.58 Edlow et al59 found that among 65 pregnant women with SARS-CoV-2 infection, including 23 who were asymptomatic and 22 with mild, 7 with moderate, 10 with severe, and 3 with critical COVID-19 disease, there was no detectable viremia, placental infection, or vertical transmission. In contrast, in a cohort of 109 pregnant women with symptomatic COVID-19 requiring hospitalization, Maeda et al60 found that 16 (14.7%) had SARS-CoV-2 viremia. In this cohort, maternal viremia was associated with the presence of SARS-CoV-2 in the cerebrospinal fluid and/or umbilical cord blood. There have been several cases in which viremia was identified in pregnant women having COVID-19 who subsequently had placentas with SARS-CoV-2 placentitis, and which were associated with fetal distress and stillbirth.61 , 62 In one study, 6 pregnant women in Chicago had COVID-19 and SARS-CoV-2 placentitis; 1 mother was asymptomatic, 4 had mild symptoms, and 1 had moderate SARS-CoV-2 infection.62 Two of the 6 women had low-level SARS-CoV-2 viremia detected—one was asymptomatic but had a stillbirth, and the other had mild illness and delivered an asymptomatic infant. Although information regarding the frequency of viremia in pregnancy is incomplete, what is known thus far suggests that SARS-CoV-2 in maternal blood is an unusual occurrence. If true, this can help to explain the very low incidence of SARS-CoV-2 infection of the placenta, which in one study was estimated by meta-analysis to be 7% among pregnant women having COVID-19.63 , 64

Strengthening the association between SARS-CoV-2 viremia, placental infection, and SARS-CoV-2 placentitis is the pathology observation of maternal white blood cells staining positively for SARS-CoV-2 circulating in the intervillous space of infected placentas with SARS-CoV-2 placentitis (Figure 5). Facchetti et al25 observed multiple maternal CD14-positive macrophages/monocytes in the intervillous space that stained positive for SARS-CoV-2 RNA using an S-antisense probe and in situ hybridization in the placenta from a stillborn infant having SARS-CoV-2 placentitis. Among a cohort of 58 placentas with SARS-CoV-2 placentitis from stillbirths caused by COVID-19 and placental insufficiency, Schwartz et al31 identified 3 placentas (5%) having macrophages in the intervillous space that were positive for SARS-CoV-2.

Pathophysiology of SARS-CoV-2 placentitis

The development of SARS-CoV-2 placentitis may be more complex than simply viral infection of placental cells. The occurrence of SARS-CoV-2 placental infection with certain chronic inflammatory lesions provides a potential pathophysiological mechanism for the immunologic basis of this destructive process. Chronic placental inflammatory lesions are a diverse group of abnormalities that are characterized by lymphocytic, plasmacellular, or histiocytic infiltration in specific anatomic compartments of the placenta that have been associated with infectious agents and immunologic disorders. In addition to its role as a respiratory, excretory, endocrine, and nutritive organ, the placenta also has complex immune functions that include maintenance of maternal-fetal tolerance. Because both the placenta and fetus are semiallografts that express paternal-derived antigens, immunologic tolerance is a requirement for a successful reproductive outcome. There is accumulating evidence that failure of maternal–fetal tolerance results in rejection of fetal-derived tissues such as the placenta, analogous to the rejection syndromes observed in allogeneic solid-organ transplantation.65, 66, 67, 68 This pathologic process has been implicated in obstetrical conditions including fetal demise, preterm premature rupture of membranes, preterm labor, and recurrent pregnancy loss, and in chronic placental conditions such as MPFD and inflammatory lesions including chronic chorioamnionitis, VUE, and chronic deciduitis.65 , 69, 70, 71, 72 Chronic placental inflammation has been shown to be characterized by infiltration of fetal-derived tissues with maternal CD8+ T lymphocytes, overexpression of the T lymphocyte cytokines CXCL9, CXCL10, and CXCL11 in chorionic villous stromal, endothelial, and Hofbauer cells, and C4d deposition—processes similar to those occurring in solid-organ rejection.65 , 73 SARS-CoV-2 placental infection is characterized by the occurrence of multiple chronic lesions that have been proposed to result from maternal antifetal rejection. Under these circumstances, fetal demise owing to placentitis and placental insufficiency would represent an extreme form of rejection.65 , 69

Further supporting the immunologic basis underlying SARS-CoV-2 placentitis is the occurrence of pathology abnormalities frequently present in placentas infected with SARS-CoV-2—CHIV, VUE, and MPFD—in diseases associated with immune alterations including systemic lupus erythematosus, autoimmune thyroid disease, and Sjögren’s syndrome.74

Clinical evidence for maternal COVID-19 vaccination preventing stillbirth

The US Food and Drug Administration granted initial emergency use authorization for the Pfizer–BioNTech messenger RNA (mRNA) vaccine on December 11, 2020 and for the Moderna mRNA vaccine on December 18, 2020, after which mass vaccinations were initiated immediately throughout the United States and other high-income countries. However, as is often the case, pregnant women remained an under-vaccinated group. There were many reasons—pregnant women were excluded from the initial vaccine trials, there was limited experience with mRNA vaccines in this group, suboptimal communication and guidance were provided by official sources and professional agencies, and there was widespread antivaccine disinformation distributed via social media and news outlets, resulting in vaccine hesitancy.75, 76, 77 By May 2021, only 16% of pregnant women in the United States received at least 1 dose of a COVID-19 vaccine.78 The problem was compounded by the spread of the SARS-CoV-2 Delta variant in 2021, which caused an increase in disease severity among pregnant women, with almost 20% of the most critically ill hospitalized COVID-19 patients in England being unvaccinated pregnant women. The CDC responded by urgently recommending that pregnant women be vaccinated.79

Multiple studies have confirmed that mRNA vaccines for COVID-19 are both safe and effective when given during pregnancy,80, 81, 82 and are highly effective in reducing maternal morbidity and mortality from SARS-CoV-2 infection.1 , 58 , 83 The vaccines do not cause placental pathology abnormalities such as intervillositis, trophoblast necrosis, increased fibrin or MPFD, villitis and thrombohematomas that are present with SARS-CoV-2 placentitis and result in placental insufficiency84 Importantly, maternal vaccination protects the fetus and newborn. Maternal vaccination stimulates systemic and mucosal immunity to reduce viral cell entry and reduces the incidence of SARS-CoV-2 infection. The efficacy of vaccinating pregnant women to reduce the rate of infection and prevent maternal and neonatal complications has been previously shown for influenza, another epidemic infectious disease caused by respiratory RNA viruses.85

COVID-19 vaccination during pregnancy induces maternal antibodies that are not only detectable in maternal sera at delivery and in breast milk, but are also present in infant sera, indicating transfer of maternal antibodies before delivery.86 , 87 Administration of mRNA SARS-CoV-2 vaccines to pregnant women induces functional antispike immunoglobulin G antibodies in the maternal circulation, which pass through the placenta and can be identified in the umbilical cord blood after birth, providing protection against COVID-19 to infants.81 , 88 , 89 The CDC found that infants born to mothers who received 2 doses of either the Pfizer or Moderna vaccines while pregnant had a 61% lower risk of being hospitalized because of COVID-19 infection in their first 6 months of age.90

Recently published clinical studies have confirmed the benefit of maternal vaccination for fetal and infant outcomes, including reduction of stillbirth. An investigation from a national cohort in Scotland that tracked pregnancies during the COVID-19 pandemic compared the clinical outcomes of 2364 infants delivered to vaccinated and unvaccinated mothers during the period between December 1, 2020 and October 31, 2021.91 A total of 11 stillborn and 8 live-born infants who died in the neonatal period were reported in this study; all deaths occurred in offspring of women who had not received COVID-19 vaccination. By the end of this study in October 2021, the vaccination coverage remained substantially lower among pregnant women compared with the nonpregnant childbearing-age female population, with 32.3% of women giving birth in October 2021 having received 2 vaccine doses vs 77.4% of all women. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the effects of maternal COVID-19 vaccination on perinatal outcomes based on 23 studies was released on May 10, 2022.75 When 66,067 pregnant women who were vaccinated against SARS-CoV-2 while pregnant were compared with 424,624 unvaccinated pregnant women, it was found that COVID-19 vaccination was associated with a 15% reduction in stillbirths. Following this report, the results of maternal vaccination against SARS-CoV-2 from the multicenter Swiss COVI-PREG registry were reported on May 29, 2022.92 Among 1012 women in Switzerland who received at least 1 dose of mRNA vaccine between March 1 and December 27, 2021, there was no increase in adverse pregnancy or neonatal outcomes compared with historic data on background risks, and importantly, there were no stillbirths reported. On June 1, 2022, the results of the Norwegian nationwide registry-based cohort study examining the effect of maternal vaccination on infant infection status were released. The study demonstrated that infants whose mothers had received the mRNA vaccine while pregnant had a substantially lower risk of testing positive for SARS-CoV-2 during the first 4 months of life compared with infants of mothers unvaccinated during pregnancy.93 This reduction in the postnatal infection risk was noted during the period dominated by the Delta and Omicron variants, although the significance was greater during the Delta predominance.

An important multicenter cohort study by Hui et al94 has provided evidence that maternal vaccination against SARS-CoV-2 results in a decreased risk of stillbirth when compared with unvaccinated women. One of the goals of this retrospective investigation from 12 maternity hospitals in Melbourne, Australia was to determine the clinical perinatal outcomes of 17,365 women who received ≥1 doses of the mRNA COVID-19 vaccine before or during pregnancy compared with 15,171 unvaccinated pregnant women during the period from July 1, 2021 to March 31, 2022. The vaccinated women had a substantially lower rate of stillbirth compared with the unvaccinated cohort (0.2% vs 0.8%; adjusted odds ratio, 0.18; 95% CI, 0.09–0.37; P<.001). Following stratification for gestational age, this association was statistically substantial only for preterm stillbirths.

On the basis of currently available data, we postulate that there is a relationship between maternal vaccination for COVID-19, SARS-CoV-2 placentitis, and stillbirth. For a virus to reach the placenta, it generally travels through the maternal bloodstream; there is no evidence that COVID-19 is a typical ascending infection that arises from the lower genital tract. In explaining the etiology of SARS-CoV-2 placentitis among 3 stillborn fetuses, Shook et al61 suggested that maternal viremia could overcome placental immune defenses at the level of the syncytiotrophoblast. Vaccination against COVID-19 not only lowers viral load and limits viremia, but also decreases vascular and tissue damage, reduces viral dissemination from the lungs to other organs, decreases the incidence of severe disease and death, and suppresses transmission.98, 97, 96, 95 These effects of COVID-19 vaccination during pregnancy can help explain the epidemiologic, clinical, and pathologic studies that indicate reduction of stillbirths among vaccinated women. However, a definitive analysis of this issue has several challenges. Placental examination was not a component of the epidemiologic clinical investigations demonstrating that vaccination provides protection to the fetus and neonate from SARS-CoV-2 infection and stillbirth. In addition, there are confounding factors to be considered, including the specific type and prevalence of the SARS-CoV-2 variants involved and the possibility that some patients may have been infected by several variants. However, correlating the clinical and epidemiologic data with those from studies of placental pathology suggests that one potential and even likely mechanism of fetal protection could be from maternal vaccination impeding maternal viremia, development of placental infection, and SARS-CoV-2 placentitis.2 It seems beyond coincidence that in the multiple reports of SARS-CoV-2 placentitis associated with stillbirths and neonatal deaths, none of the mothers had received COVID-19 vaccinations. In addition, although not constituting proof, the authors are not aware either personally, via collegial networks, or in the published literature of any cases of SARS-CoV-2 placentitis causing stillbirths among pregnant women who received the COVID-19 vaccine. In contrast to many other TORCH agents, a major cause of perinatal deaths among fetuses and neonates having placentas compromised by SARS-CoV-2 is placental insufficiency and not direct viral infection of the fetal organs following transplacental transmission.2 , 31 Because the tissue pathology related to COVID-19 seems to be most prominent in the placenta, where it is highly destructive, it may be possible that effective vaccination of pregnant women can either decrease the severity or even inhibit the development of SARS-CoV-2 placentitis. Thus, maternal vaccination against COVID-19 may be life-saving for the fetus and the mother.

Footnotes

The authors report no conflict of interest.

Supplementary Data

Schwartz. Placentitis, stillbirth, and maternal COVID-19 vaccination. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2023.

References

- 1.Chinn J., Sedighim S., Kirby K.A., et al. Characteristics and outcomes of women with COVID-19 giving birth at US academic centers during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4 doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.20456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schwartz D.A. Stillbirth after COVID-19 in unvaccinated mothers can result from SARS-CoV-2 placentitis, placental insufficiency, and hypoxic ischemic fetal demise, not direct fetal infection: potential role of maternal vaccination in pregnancy. Viruses. 2022;14:458. doi: 10.3390/v14030458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.King A. Doctors investigate several stillbirths among moms with COVID-19. 2021. https://www.the-scientist.com/news-opinion/doctors-investigate-several-stillbirths-among-moms-with-covid-19-68703 Available at: Accessed May 20, 2022.

- 4.Fitzgerald B., O’Donoghue K., McEntagart N., et al. Fetal deaths in Ireland due to SARS-CoV-2 placentitis caused by SARS-CoV-2 alpha. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2022;146:529–537. doi: 10.5858/arpa.2021-0586-SA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gurol-Urganci I., Jardine J.E., Carroll F., et al. Maternal and perinatal outcomes of pregnant women with SARS-CoV-2 infection at the time of birth in England: national cohort study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2021;225 doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2021.05.016. 522.e1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.DeSisto C.L., Wallace B., Simeone R.M., et al. Risk for stillbirth among women with and without COVID-19 at delivery hospitalization - United States, March 2020-September 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70:1640–1645. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7047e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Redline R.W., Zaragoza M., Hassold T. Prevalence of developmental and inflammatory lesions in nonmolar first-trimester spontaneous abortions. Hum Pathol. 1999;30:93–100. doi: 10.1016/s0046-8177(99)90307-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abdulghani S., Moretti F., Gruslin A., Grynspan D. Recurrent massive perivillous fibrin deposition and chronic intervillositis treated with heparin and intravenous immunoglobulin: a case report. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2017;39:676–681. doi: 10.1016/j.jogc.2017.03.089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Abdulghani S., Moretti F., Nikkels P.G., Khung-Savatovsky S., Hurteau-Miller J., Grynspan D. Growth restriction, osteopenia, placental massive perivillous fibrin deposition with (or without) intervillous histiocytes and renal tubular dysgenesis-an emerging complex. Pediatr Dev Pathol. 2018;21:91–94. doi: 10.1177/1093526617697061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cornish E.F., McDonnell T., Williams D.J. Chronic inflammatory placental disorders associated with recurrent adverse pregnancy outcome. Front Immunol. 2022;13 doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.825075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sebire N.J., Backos M., Goldin R.D., Regan L. Placental massive perivillous fibrin deposition associated with antiphospholipid antibody syndrome. BJOG. 2002;109:570–573. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2002.00077.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Faye-Petersen O.M., Ernst L.M. Maternal floor infarction and massive perivillous fibrin deposition. Surg Pathol Clin. 2013;6:101–114. doi: 10.1016/j.path.2012.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Weber M.A., Nikkels P.G., Hamoen K., Duvekot J.J., de Krijger R.R. Co-occurrence of massive perivillous fibrin deposition and chronic intervillositis: case report. Pediatr Dev Pathol. 2006;9:234–238. doi: 10.2350/06-01-0019.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Labarrere C., Mullen E. Fibrinoid and trophoblastic necrosis with massive chronic intervillositis: an extreme variant of villitis of unknown etiology. Am J Reprod Immunol Microbiol. 1987;15:85–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.1987.tb00162.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Labarrere C.A., Bammerlin E., Hardin J.W., Dicarlo H.L. Intercellular adhesion molecule-1 expression in massive chronic intervillositis: implications for the invasion of maternal cells into fetal tissues. Placenta. 2014;35:311–317. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2014.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bos M., Nikkels P.G.J., Cohen D., et al. Towards standardized criteria for diagnosing chronic intervillositis of unknown etiology: a systematic review. Placenta. 2018;61:80–88. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2017.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marchaudon V., Devisme L., Petit S., Ansart-Franquet H., Vaast P., Subtil D. Chronic histiocytic intervillositis of unknown etiology: clinical features in a consecutive series of 69 cases. Placenta. 2011;32:140–145. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2010.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ismail M.R., Ordi J., Menendez C., et al. Placental pathology in malaria: a histological, immunohistochemical, and quantitative study. Hum Pathol. 2000;31:85–93. doi: 10.1016/s0046-8177(00)80203-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Di Gennaro F., Marotta C., Locantore P., Pizzol D., Putoto G. Malaria and COVID-19: common and different findings. Trop Med Infect Dis. 2020;5:141. doi: 10.3390/tropicalmed5030141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Benachi A., Rabant M., Martinovic J., et al. Chronic histiocytic intervillositis: manifestation of placental alloantibody-mediated rejection. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2021;225 doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2021.06.051. 662.e1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Katzman P.J., Genest D.R. Maternal floor infarction and massive perivillous fibrin deposition: histological definitions, association with intrauterine fetal growth restriction, and risk of recurrence. Pediatr Dev Pathol. 2002;5:159–164. doi: 10.1007/s10024001-0195-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.He M., Migliori A., Maari N.S., Mehta N.D. Follow-up and management of recurrent pregnancy losses due to massive perivillous fibrinoid deposition. Obstet Med. 2018;11:17–22. doi: 10.1177/1753495X17710129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bane A.L., Gillan J.E. Massive perivillous fibrinoid causing recurrent placental failure. BJOG. 2003;110:292–295. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Patanè L., Morotti D., Giunta M.R., et al. Vertical transmission of coronavirus disease 2019: severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 RNA on the fetal side of the placenta in pregnancies with coronavirus disease 2019-positive mothers and neonates at birth. Am J Obstet Gynecol MFM. 2020;2 doi: 10.1016/j.ajogmf.2020.100145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Facchetti F., Bugatti M., Drera E., et al. SARS-CoV2 vertical transmission with adverse effects on the newborn revealed through integrated immunohistochemical, electron microscopy and molecular analyses of placenta. EBioMedicine. 2020;59 doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2020.102951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schwartz D.A., Morotti D. Placental pathology of COVID-19 with and without fetal and neonatal infection: trophoblast necrosis and chronic histiocytic intervillositis as risk factors for transplacental transmission of SARS-CoV-2. Viruses. 2020;12:1308. doi: 10.3390/v12111308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vivanti A.J., Vauloup-Fellous C., Prevot S., et al. Transplacental transmission of SARS-CoV-2 infection. Nat Commun. 2020;11:3572. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-17436-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schwartz D.A., Baldewijns M., Benachi A., et al. Chronic histiocytic intervillositis with trophoblast necrosis is a risk factor associated with placental infection from coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) and intrauterine maternal-fetal severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) transmission in live-born and stillborn infants. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2021;145:517–528. doi: 10.5858/arpa.2020-0771-SA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Watkins J.C., Torous V.F., Roberts D.J. Defining severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) placentitis. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2021;145:1341–1349. doi: 10.5858/arpa.2021-0246-SA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schwartz D.A., Baldewijns M., Benachi A., et al. Hofbauer cells and COVID-19 in pregnancy. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2021;145:1328–1340. doi: 10.5858/arpa.2021-0296-SA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schwartz D.A., Avvad-Portari E., Babál P., et al. Placental tissue destruction and insufficiency from COVID-19 causes stillbirth and neonatal death from hypoxic-ischemic injury: A study of 68 cases with SARS-CoV-2 placentitis from 12 countries. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2022;146:660–676. doi: 10.5858/arpa.2022-0029-SA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zaigham M., Gisselsson D., Sand A., et al. Clinical-pathological features in placentas of pregnancies with SARS-CoV-2 infection and adverse outcome: case series with and without congenital transmission. BJOG. 2022;129:1361–1374. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.17132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Konstantinidou A.E., Angelidou S., Havaki S., et al. Stillbirth due to SARS-CoV-2 placentitis without evidence of intrauterine transmission to fetus: association with maternal risk factors. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2022;59:813–822. doi: 10.1002/uog.24906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Huynh A., Sehn J.K., Goldfarb I.T., et al. SARS-CoV-2 placentitis and intraparenchymal thrombohematomas among COVID-19 infections in pregnancy. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5 doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.5345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Delorme-Axford E., Sadovsky Y., Coyne C.B. The placenta as a barrier to viral infections. Annu Rev Virol. 2014;1:133–146. doi: 10.1146/annurev-virology-031413-085524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nahmias A.J., Panigel M., Schwartz D.A. The eight most frequent blood-borne infectious agents affecting the placenta and fetus. Placenta. 1994;15(Suppl1):193–213. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Megli C.J., Coyne C.B. Infections at the maternal-fetal interface: an overview of pathogenesis and defence. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2022;20:67–82. doi: 10.1038/s41579-021-00610-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schwartz D.A., Levitan D. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infecting pregnant women and the fetus, intrauterine transmission, and placental pathology during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic: it’s complicated. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2021;145:925–928. doi: 10.5858/arpa.2021-0164-ED. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lu-Culligan A., Chavan A.R., Vijayakumar P., et al. Maternal respiratory SARS-CoV-2 infection in pregnancy is associated with a robust inflammatory response at the maternal-fetal interface. Med (N Y) 2021;2:591–610.e10. doi: 10.1016/j.medj.2021.04.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Taglauer E., Benarroch Y., Rop K., et al. Consistent localization of SARS-CoV-2 spike glycoprotein and ACE2 over TMPRSS2 predominance in placental villi of 15 COVID-19 positive maternal-fetal dyads. Placenta. 2020;100:69–74. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2020.08.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schwartz D.A., Bugatti M., Santoro A., Facchetti F. Molecular pathology demonstration of SARS-CoV-2 in cytotrophoblast from placental tissue with chronic histiocytic intervillositis, trophoblast necrosis and COVID-19. J Dev Biol. 2021;9:33. doi: 10.3390/jdb9030033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schwartz D.A., Dhaliwal A. Coronavirus diseases in pregnant women, the placenta, fetus, and neonate. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2021;1318:223–241. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-63761-3_14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Li Y., Li J.Z. SARS-CoV-2 virology. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2022;36:251–265. doi: 10.1016/j.idc.2022.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Prebensen C., Myhre P.L., Jonassen C., et al. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 RNA in plasma is associated with intensive care unit admission and mortality in patients hospitalized with coronavirus disease 2019. Clin Infect Dis. 2021;73:e799–e802. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa1338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gutmann C., Takov K., Burnap S.A., et al. SARS-CoV-2 RNAemia and proteomic trajectories inform prognostication in COVID-19 patients admitted to intensive care. Nat Commun. 2021;12:3406. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-23494-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang C., Li Y., Kaplonek P., et al. The kinetics of SARS-CoV-2 antibody development is associated with clearance of RNAemia. mBio. 2022;13 doi: 10.1128/mbio.01577-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Li Y., Schneider A.M., Mehta A., et al. SARS-CoV-2 viremia is associated with distinct proteomic pathways and predicts COVID-19 outcomes. J Clin Invest. 2021;131 doi: 10.1172/JCI148635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tang K., Wu L., Luo Y., Gong B. Quantitative assessment of SARS-CoV-2 RNAemia and outcome in patients with coronavirus disease 2019. J Med Virol. 2021;93:3165–3175. doi: 10.1002/jmv.26876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chen X., Zhao B., Qu Y., et al. Detectable serum severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 viral load (RNAemia) is closely correlated with drastically elevated interleukin 6 level in critically ill patients with coronavirus disease 2019. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;71:1937–1942. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Roy-Vallejo E., Cardeñoso L., Triguero-Martínez A., et al. SARS-CoV-2 viremia precedes an IL6 response in severe COVID-19 patients: results of a longitudinal prospective cohort. Front Med (Lausanne) 2022;9 doi: 10.3389/fmed.2022.855639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fajnzylber J., Regan J., Coxen K., et al. SARS-CoV-2 viral load is associated with increased disease severity and mortality. Nat Commun. 2020;11:5493. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-19057-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cardeñoso Domingo L., Roy Vallejo E., Zurita Cruz N.D., et al. Relevant SARS-CoV-2 viremia is associated with COVID-19 severity: prospective cohort study and validation cohort. J Med Virol. 2022;94:5260–5270. doi: 10.1002/jmv.27989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bermejo-Martin J.F., González-Rivera M., Almansa R., et al. Viral RNA load in plasma is associated with critical illness and a dysregulated host response in COVID-19. Crit Care. 2020;24:691. doi: 10.1186/s13054-020-03398-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hagman K., Hedenstierna M., Rudling J., et al. Duration of SARS-CoV-2 viremia and its correlation to mortality and inflammatory parameters in patients hospitalized for COVID-19: a cohort study. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2022;102 doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2021.115595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rodríguez-Serrano D.A., Roy-Vallejo E., Zurita Cruz N.D., et al. Detection of SARS-CoV-2 RNA in serum is associated with increased mortality risk in hospitalized COVID-19 patients. Sci Rep. 2021;11 doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-92497-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kawasuji H., Morinaga Y., Tani H., et al. SARS-CoV-2 RNAemia with a higher nasopharyngeal viral load is strongly associated with disease severity and mortality in patients with COVID-19. J Med Virol. 2022;94:147–153. doi: 10.1002/jmv.27282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jacobs J.L., Bain W., Naqvi A., et al. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 viremia is associated with coronavirus disease 2019 severity and predicts clinical outcomes. Clin Infect Dis. 2022;74:1525–1533. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciab686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Jamieson D.J., Rasmussen S.A. An update on COVID-19 and pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2022;226:177–186. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2021.08.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Edlow A.G., Li J.Z., Collier A.Y., et al. Assessment of maternal and neonatal SARS-CoV-2 viral load, transplacental antibody transfer, and placental pathology in pregnancies during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3 doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.30455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Maeda M.F.Y., Brizot M.L., Gibelli M.A.B.C., et al. Vertical transmission of SARS-CoV2 during pregnancy: a high-risk cohort. Prenat Diagn. 2021;41:998–1008. doi: 10.1002/pd.5980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Shook L.L., Brigida S., Regan J., et al. SARS-CoV-2 placentitis associated with B.1.617.2 (Delta) variant and fetal distress or demise. J Infect Dis. 2022;225:754–758. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiac008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Mithal L.B., Otero S., Simons L.M., et al. Low-level SARS-CoV-2 viremia coincident with COVID placentitis and stillbirth. Placenta. 2022;121:79–81. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2022.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kotlyar A.M., Grechukhina O., Chen A., et al. Vertical transmission of coronavirus disease 2019: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2021;224:35–53.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2020.07.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Roberts D.J., Edlow A.G., Romero R.J., et al. A standardized definition of placental infection by SARS-CoV-2, a consensus statement from the National Institutes of Health/Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development SARS-CoV-2 placental infection workshop. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2021;225 doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2021.07.029. 593.e1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kim C.J., Romero R., Chaemsaithong P., Kim J.S. Chronic inflammation of the placenta: definition, classification, pathogenesis, and clinical significance. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;213:S53–S69. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2015.08.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Erlebacher A. Why isn’t the fetus rejected? Curr Opin Immunol. 2001;13:590–593. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(00)00264-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Maymon E., Romero R., Bhatti G., et al. Chronic inflammatory lesions of the placenta are associated with an up-regulation of amniotic fluid CXCR3: a marker of allograft rejection. J Perinat Med. 2018;46:123–137. doi: 10.1515/jpm-2017-0042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Goldstein J.A., Gallagher K., Beck C., Kumar R., Gernand A.D. Maternal-fetal inflammation in the placenta and the developmental origins of health and disease. Front Immunol. 2020;11 doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.531543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lannaman K., Romero R., Chaiworapongsa T., et al. Fetal death: an extreme manifestation of maternal anti-fetal rejection. J Perinat Med. 2017;45:851–868. doi: 10.1515/jpm-2017-0073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kim C.J., Romero R., Kusanovic J.P., et al. The frequency, clinical significance, and pathological features of chronic chorioamnionitis: a lesion associated with spontaneous preterm birth. Mod Pathol. 2010;23:1000–1011. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2010.73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kim M.J., Romero R., Kim C.J., et al. Villitis of unknown etiology is associated with a distinct pattern of chemokine up-regulation in the feto-maternal and placental compartments: implications for conjoint maternal allograft rejection and maternal anti-fetal graft-versus-host disease. J Immunol. 2009;182:3919–3927. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0803834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Romero R., Whitten A., Korzeniewski S.J., et al. Maternal floor infarction/massive perivillous fibrin deposition: a manifestation of maternal antifetal rejection? Am J Reprod Immunol. 2013;70:285–298. doi: 10.1111/aji.12143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Raman K., Wang H., Troncone M.J., Khan W.I., Pare G., Terry J. Overlap chronic placental inflammation Is associated with a unique gene expression pattern. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0133738. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0133738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.A Lee K., Kim Y.W., Shim J.Y., et al. Distinct patterns of C4d immunoreactivity in placentas with villitis of unknown etiology, cytomegaloviral placentitis, and infarct. Placenta. 2013;34:432–435. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2013.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Prasad S., Kalafat E., Blakeway H., et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the effectiveness and perinatal outcomes of COVID-19 vaccination in pregnancy. Nat Commun. 2022;13:2414. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-30052-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Shook L.L., Kishkovich T.P., Edlow A.G. Countering COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in pregnancy: the “4 Cs”. Am J Perinatol. 2022;39:1048–1054. doi: 10.1055/a-1673-5546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Iacobucci G. Covid-19 and pregnancy: vaccine hesitancy and how to overcome it. BMJ. 2021;375:n2862. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n2862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Razzaghi H., Meghani M., Pingali C., et al. COVID-19 vaccination coverage among pregnant women during pregnancy – eight integrated health care organizations, United States. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70:895–899. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7024e2. December 14, 2020-May 8, 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention New CDC Data: COVID-19 vaccination safe for pregnant People. 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2021/s0811-vaccine-safe-pregnant.html Available at: Accessed May 20, 2022.

- 80.Kharbanda E.O., Vazquez-Benitez G. COVID-19 mRNA vaccines during pregnancy: new evidence to help address vaccine hesitancy. JAMA. 2022;327:1451–1453. doi: 10.1001/jama.2022.2459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Pratama N.R., Wafa I.A., Budi D.S., Putra M., Wardhana M.P., Wungu C.D.K. mRNA COVID-19 vaccines in pregnancy: a systematic review. PLoS One. 2022;17 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0261350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Moro P.L., Olson C.K., Clark E., et al. Post-authorization surveillance of adverse events following COVID-19 vaccines in pregnant persons in the vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System (VAERS) Vaccine. 2022;40:3389–3394. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2022.04.031. December 2020-October 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Morgan J.A., Biggio J.R., Jr., Martin J.K., et al. Maternal outcomes after severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection in vaccinated compared with unvaccinated pregnant patients. Obstet Gynecol. 2022;139:107–109. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000004621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Shanes E.D., Otero S., Mithal L.B., Mupanomunda C.A., Miller E.S., Goldstein J.A. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) vaccination in pregnancy: measures of immunity and placental histopathology. Obstet Gynecol. 2021;138:281–283. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000004457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.National Advisory Committee on Immunization An Advisory Committee Statement (ACS) National Advisory Committee on Immunization: statement on seasonal influenza vaccine for 2014-2015. 2014. http://www.phac-aspc.gcca/naci-ccni/assets/pdf/flu-grippe-eng.pdf Available at: Accessed May 18, 2022.

- 86.Nir O., Schwartz A., Toussia-Cohen S., et al. Maternal-neonatal transfer of SARS-CoV-2 immunoglobulin G antibodies among parturient women treated with BNT162b2 messenger RNA vaccine during pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol MFM. 2022;4 doi: 10.1016/j.ajogmf.2021.100492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Trostle M.E., Aguero-Rosenfeld M.E., Roman A.S., Lighter J.L. High antibody levels in cord blood from pregnant women vaccinated against COVID-19. Am J Obstet Gynecol MFM. 2021;3 doi: 10.1016/j.ajogmf.2021.100481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Shook L.L., Atyeo C.G., Yonker L.M., et al. Durability of anti-spike antibodies in infants after maternal COVID-19 vaccination or natural infection. JAMA. 2022;327:1087–1089. doi: 10.1001/jama.2022.1206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Mithal L.B., Otero S., Shanes E.D., Goldstein J.A., Miller E.S. Cord blood antibodies following maternal coronavirus disease 2019 vaccination during pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2021;225:192–194. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2021.03.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Halasa N.B., Olson S.M., Staat M.A., et al. Effectiveness of maternal vaccination with mRNA COVID-19 vaccine during pregnancy against COVID-19-associated hospitalization in infants aged <6 months - 17 states, July 2021-January 2022. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2022;71:264–270. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7107e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Stock S.J., Carruthers J., Calvert C., et al. SARS-CoV-2 infection and COVID-19 vaccination rates in pregnant women in Scotland. Nat Med. 2022;28:504–512. doi: 10.1038/s41591-021-01666-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Favre G., Maisonneuve E., Pomar L., et al. COVID-19 mRNA vaccine in pregnancy: results of the Swiss COVI-PREG registry, an observational prospective cohort study. Lancet Reg Health Eur. 2022;18 doi: 10.1016/j.lanepe.2022.100410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Carlsen E.Ø., Magnus M.C., Oakley L., et al. Association of COVID-19 vaccination during pregnancy with incidence of SARS-CoV-2 infection in infants. JAMA Intern Med. 2022;182:825–831. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2022.2442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Hui L., Marzan M.B., Rolnik D.L., et al. Reductions in stillbirths and preterm birth in COVID-19 vaccinated women: a multi-center cohort study of vaccination uptake and perinatal outcome. 2022. https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2022.07.04.22277193v1 Available at: Accessed September 20, 2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 95.Levine-Tiefenbrun M., Yelin I., Katz R., et al. Initial report of decreased SARS-CoV-2 viral load after inoculation with the BNT162b2 vaccine. Nat Med. 2021;27:790–792. doi: 10.1038/s41591-021-01316-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Mohamed K., Rzymski P., Islam M.S., et al. COVID-19 vaccinations: the unknowns, challenges, and hopes. J Med Virol. 2022;94:1336–1349. doi: 10.1002/jmv.27487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Qin Z., Sun Y., Zhang J., Zhou L., Chen Y., Huang C. Lessons from SARS-CoV-2 and its variants (review) Mol Med Rep. 2022;26:263. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2022.12779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.University of Arizona News COVID-19 vaccine reduces severity, length, viral load for those who still get infected. 2021. https://news.arizona.edu/story/covid-19-vaccine-reduces-severity-length-viral-load-those-who-still-get-infected Available at: Accessed May 17, 2022.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Schwartz. Placentitis, stillbirth, and maternal COVID-19 vaccination. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2023.