Abstract

Over the last 20 years, we have learned much about the extent to which early-life deprivation affects the mental health of children and adolescents. This body of evidence comes predominantly from studies of children raised in institutional care. The Bucharest Early Intervention Project (BEIP) is the only randomized controlled trial designed to evaluate whether the transition to family-based foster care early in development can ameliorate the long-term impact of institutional deprivation on psychopathology during vulnerable developmental windows such as adolescence. In this review, we detail the extent to which early deprivation affects mental health during this period, the capacity of family-based care to facilitate recovery from early deprivation, and the mechanisms underpinning these effects spanning social–emotional, cognitive, stress, and neurobiological domains. We end by discussing the implications and directions for the BEIP and other studies of youth raised in institutions.

Keywords: early-life deprivation, foster care intervention, institutional raising

We know a great deal about how experience influences the course of brain and behavioral development. Not surprisingly, inadequate environmental input (e.g., deprivation) during sensitive periods of brain development can have severe and, in some cases, lasting effects on multiple domains of functioning (Nelson & Gabard-Durnam, 2020; Nelson III et al., 2019). In humans, our understanding of the impact of severe psychosocial deprivation on development comes primarily from studies of children raised in institutions; an estimated 3–9 million children worldwide live in institutions (Desmond et al., 2020). Psychosocial deprivation in institutional care is similar to experiences of severe neglect, the most common form of child maltreatment, which is estimated to affect nearly 500,000 children in the United States annually (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2019).

The Bucharest Early Intervention Project (BEIP), the only randomized controlled trial (RCT) of foster care as an alternative to institutional care for orphaned and abandoned children, is one of the most important studies on the impact of early deprivation on development (van IJzendoorn et al., 2020). In addition to being an RCT, the BEIP has studied children from infancy into young adulthood, permitting causal conclusions about whether and to what extent social enrichment in the form of family care can promote recovery from early deprivation over the first two decades of life.

In this article, we delineate what we have learned about the mechanisms of long-term risk for, and recovery from, psychopathology during the transition to adolescence following early deprivation. We focus on mid-childhood to adolescence, a period of significant social and neuro-biological change and increased vulnerability to mental health problems (Blakemore, 2019). We begin by briefly describing the history of the BEIP, then review studies documenting the level of mental health difficulties during follow-ups at ages 8, 12, and 16 years. We then describe the mechanisms underpinning risk and recovery from early deprivation in relation to common mental health problems (i.e., anxiety, depression, ADHD) during adolescence (for a discussion of attachment-specific problems, see Guyon-Harris et al., 2018, 2019; Humphreys et al., 2017; Rutter et al., 2007; Smyke et al., 2012).

THE HISTORICAL CONTEXT AND DESIGN OF THE BEIP

During Nicolae Ceaușescu’s leadership of Romania (1965–1989), several repressive policies were instituted to force population growth despite rampant nationwide poverty, which in turn gave rise to significant abandonment of children to state-r un orphanages. By 1989, more than 170,000 children were being raised in institutional care (Rosapepe, 2001). The institutions were generally overcrowded, understaffed, and insensitive to the individual needs of children―a pattern we describe as gross psychosocial neglect. The BEIP was initiated in the fall of 2000 with the encouragement of Romania’s new National Authority for Child Protection and with the cooperation of the Ministry of Health. The Secretary of State for Child Protection wanted data about alternatives to institutional care. Foster care had only recently become legal in Romania and was not widely available when the study began (see Zeanah et al., 2003).

By design, the BEIP compared continued institutional care to high-quality foster care, allowing us to examine the effects of early deprivation on brain and behavioral development, the remedial benefits of family care, and the possibility of sensitive periods (i.e., age-of-placement effects) in development. Participants included 136 children recruited from six institutions in Bucharest, all from 6 to 31 months old. These children had no discernible genetic or neurological syndromes, nor did they show overt signs of fetal alcohol exposure (see online Supplement for sample characteristics). After comprehensive assessments, the children were randomly assigned to foster care (foster care group, FCG) or to continued institutional care (care-as-usual group, CAUG). Researchers adopted a policy of noninterference during the trial, meaning that children in the CAUG could move into other placements as they became available, and children from both groups changed placements over time (see Figure S1 for CONSORT diagram showing flow of participants over time). Comparisons between the FCG and the CAUG reflect their original placement assignment (i.e., intent to treat), regardless of current placement (unless otherwise stated). Together, the FCG and CAUG are referred to as the ever-institutionalized group (EIG). For further comparison, a group of 72 children living in Bucharest who had never been institutionalized were recruited as community controls (never-institutionalized group, NIG; see Nelson et al., 2014, for details).

The foster care program was multidimensional. First, foster families were given monthly stipends equal to the average per capita income in the country at the time. Second, BEIP social workers closely monitored and supported foster parents, who had access to an on-call pediatrician. In addition, Romanian law at the time required one parent to stay at home with the child, ensuring consistent adult caregiving. In contrast, children assigned to the CAUG typically remained in the institutions outlined earlier, marking a clear distinction between the care trajectories of the FCG and the CAUG.

The trial assessed children at 30, 42, and 54 months, at which point it concluded and management of the BEIP foster care network transferred to local governmental authorities. Prior reviews from our group have covered this period of development (Bos et al., 2011). Follow-up assessments for all three groups of children occurred at ages 8, 12, and 16 years, which are the focus of this review. While children have been evaluated across multiple domains of functioning, in this article, we focus on mental health given the powerful link between early-life adversity and mental health and the dramatic changes in mental health that occur during adolescence.

ADOLESCENCE AS A POTENTIAL PERIOD OF RECOVERY

Next, we describe findings on the recovery-promoting effect of foster care relative to care-as-usual on mental health difficulties over the course of adolescence. Using a categorical approach that relied on the administration of psychiatric interviews, indications of recovery from deprivation were observed in the BEIP beginning at 12 years, with children in the FCG displaying fewer externalizing symptoms than those in the CAUG, and again at 16 years, with children in the FCG displaying fewer internalizing symptoms than those in the CAUG (Humphreys et al., 2015, 2020). However, a lack of assessments using this approach at 8 years means it is unclear from these studies whether the recovery-promoting effect of foster care had occurred earlier in development, or whether adolescence facilitated this recovery.

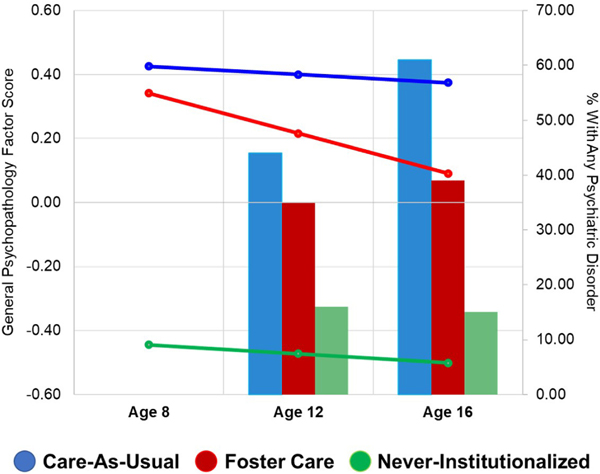

To this end, dimensional assessments of psychopathology were conducted at 8, 12, and 16 years. Children and youth in the CAUG had persistently elevated trajectories of general and externalizing-specific psychopathology from 8 to 16 years, while those in the FCG showed modestly declining trajectories of psychopathology over the same period (Wade et al., 2018). The benefit of foster care relative to prolonged institutional care was not observed at 8 years but began to appear at 12 years and, by 16 years, children in the FCG had significantly lower psychopathology than children in the CAUG (see Figure 1). These results suggest that adolescence may open a window for recovery in mental health among those who experienced social enrichment following early deprivation.

F IGU R E 1.

Summary of descriptive findings for mental health outcomes at ages 8, 12, and 16 years. Findings for outcomes in the three study groups: care-as-usual (blue), foster care (red), and never-institutionalized (green). Bars represent rates of any psychiatric disorder as a percentage of that group based on categorical assessment using psychiatric interviews (right axis), while lines represent model-estimated trajectories of general psychopathology based on dimensional assessment using teacher/caregiver ratings of behavior (left axis). There are no published data in the BEIP using psychiatric interviews at age 8. Details on the pattern of these findings are presented in the main text. Adapted with permission from Wade et al., 2018, and Humphreys et al., 2015, 2020.

MECHANISMS OF RECOVERY FOLLOWING FAMILY-BASED CARE

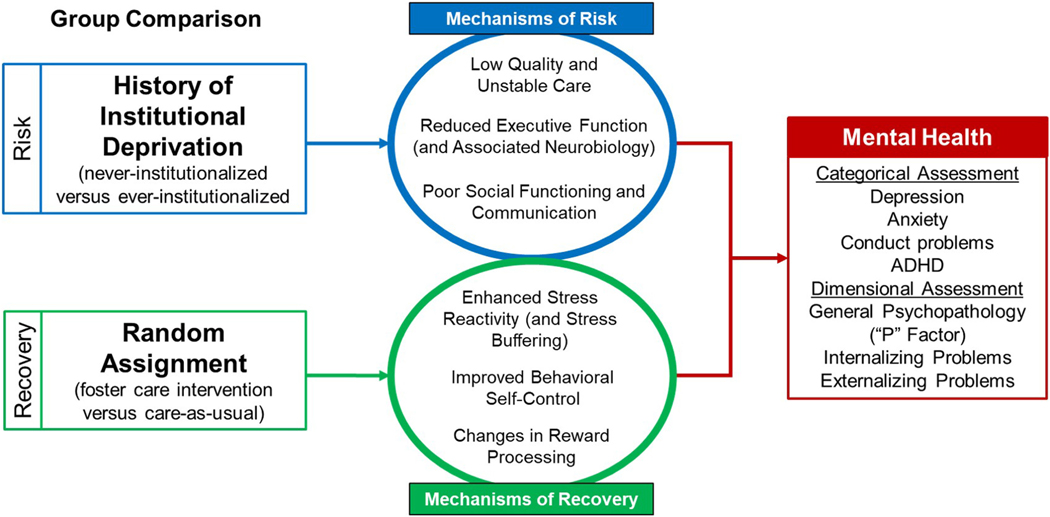

These findings demonstrate that placement into family care following deprivation may facilitate recovery in mental health during adolescence. Next, we describe what we know about the potential mechanisms that underlie this recovery effect. Figure 2 provides a visual overview of these mechanisms, as well as those related to long-term risk conferred by early deprivation, which we cover later.

F IGU R E 2.

Mechanisms of risk and recovery in mental health during adolescence within the BEIP. Summary of findings from the Bucharest Early Intervention Project on mechanisms of risk (circled in blue) and mechanisms of recovery (circled in green) following severe early-life deprivation with respect to psychopathology from age 8 to 16 years. Risk is defined as the effect of institutional rearing (ever vs. never), while recovery is defined as the effect of random assignment to the intervention (foster care vs. care-as-usual).

The first factor that appears to facilitate recovery from deprivation is stability in the postinstitutional caregiving environment. Indeed, at both 12 and 16 years, FCG children in stable foster placements (FCG-stable) had lower rates of psychiatric disorders than CAUG and FCG children in disrupted placements (FCG-disrupted). Although overall rates of psychiatric disorders increased from 12 to 16 years among the CAUG and FCG-disrupted children, they decreased slightly over this period for the FCG-stable children. By comparison, in the English and Romanian Adoptees (ERA) study, levels of emotional and conduct problems among individuals raised in institutions were relatively low and stable from 6 to 15 years, with a sharp increase during later adolescence (15 years to young adulthood), particularly among those with more than 6 months of early deprivation (Sonuga-Barke et al., 2017). Studying the BEIP participants in early adulthood will help determine whether stable caregiving continues to buffer against mental health difficulties as these youth navigate the transition to adulthood.

In addition to stability in family care, three other mechanisms appear to operate in the recovery of mental health as a function of foster care. The first is stress reactivity, where we have shown that children in the FCG demonstrated a level of neuroendocrine and sympathetic reactivity to social stress at 12 years that resembles children in the NIG, especially when foster placement occurred prior to age 24 months (McLaughlin et al., 2015). In contrast, children in the CAUG demonstrated persistently blunted reactivity to social stress (also see Wade, Sheridan, et al., 2020), strongly suggesting a sensitive period for recovering the adaptive stress response early in development. Moreover, this may have consequences for how these individuals respond to stressors during adolescence. For example, while the CAUG children showed more externalizing problems in response to stressful life events during adolescence, the FCG children were relatively buffered from these stressors (Wade, Zeanah, et al., 2019).

This resilience-enhancing effect of foster care was also observed for markers of low-grade inflammation (i.e., interleukin-6), suggesting that early foster care may protect against stress-based and inflammatory processes associated with a heightened risk of psychopathology (Tang et al., 2020). Thus, foster care following early deprivation appears to promote recovery in stress reactivity, which in turn enables effective coping with stressors during adolescence. Recent research by other groups has demonstrated that, when postinstitutionalized adolescents live in positive caregiving environments, early blunted cortisol reactivity recalibrates to levels comparable to noninstitutionalized youth (Gunnar et al., 2019), an effect that may be driven by hormonal changes during puberty (Howland et al., 2020). We are testing this hypothesis in the BEIP, where the RCT design will help determine whether early assignment to family care facilitates recalibration to a greater degree compared to prolonged early deprivation.

Another domain through which recovery is possible is self-control. We differentiate this from executive function (described later) as the ability to modulate behavior in social contexts (e.g., resisting peer influence). Using caregivers’ and teachers’ reports of behavior, we have shown that children in the FCG demonstrated more growth in self-control from 8 to 16 years than did children in the CAUG (Mukerji et al., 2021). Similar to dimensional psychopathology, children in the FCG and the CAUG did not differ on their level of self-control at 8 years, but by 16 years, the FCG children had markedly better self-control than the CAUG children and were, in fact, no different from the NIG children. This demonstrates the possibility of a sleeper effect, with the remedial benefits of family care on self-control not fully realized until the transition to adolescence. Moreover, increased growth in self-control mediated the effect of the intervention on general psychopathology at 16 years.

This finding contrasts with the general lack of recovery in objectively-assessed executive function observed in the BEIP from 8 to 16 years (e.g., Wade, Fox, et al., 2019). Thus, while executive function may be highly disrupted by profound deprivation and less amenable to foster care, children and youth may be able to learn effective strategies for controlling behavior and regulating emotions in social contexts. These behavioral results cohere with recent findings from the BEIP on brain activity, which show that the foster care intervention is associated with improvements in mediofrontal theta power during response inhibition, and these improvements are in turn associated with reduced general psychopathology at 16 years (Buzzell et al., 2020). Strikingly, the level of mediofrontal theta power among the FCG children in this study was comparable to that of the NIG children, suggesting full recovery. This is consistent with the idea that improvements in inhibitory control and self-monitoring following entry into positive caregiving environments may facilitate recovery in mental health among adolescents exposed to early deprivation.

Finally, children in the FCG demonstrated improvements in associative learning and reward responsiveness compared to children in the CAUG, and this, in turn, was associated with reduced symptoms of depression at 12 years (Sheridan et al., 2018). These improvements in associative learning may stem from increased contingent responsiveness that the FCG children received in high-quality caregiving environments. Indeed, at 12 and 16 years, higher-quality caregiving was associated with greater behavioral sensitivity to reward and lower internalizing and externalizing problems (Colich et al., 2021). Given the known associations between reward processing and mental health in adolescence (McCrory et al., 2017), these findings suggest that improvements in caregiving may be a common pathway to improved reward processing and recovery in psychopathology following early deprivation.

LONG-TERM RISK OF EARLY DEPRIVATION

While these findings provide compelling evidence that family care following institutionalization is associated with at least partial recovery in mental health during adolescence, this recovery is not absolute. Indeed, at ages 12 and 16 years, rates of psychiatric disorders were higher among both the CAUG and FCG children than among the NIG children, with this gap widening slightly over time (see Figure 1 and Humphreys et al., 2015, 2020). At both ages, the largest difference was for externalizing disorders and ADHD. Similar results were observed using the dimensional approach, where it can be seen in Figure 1 that, while the FCG children showed declining trajectories of general psychopathology from 8 to 16 years, both the FCG and the CAUG children had significantly higher levels of psychopathology than the NIG children at all time points.

Thus, exposure to early deprivation appears to confer a long-term residual risk of mental health difficulties. This contrasts with findings from the ERA, which demonstrated that children adopted before 6 months were usually comparable to noninstitutionalized children on psychopathology later in development. We have not observed strong age-of-placement effects for psychopathology in the BEIP. In part, this may reflect the relatively later age of placement into foster care (average of 22 months) in the BEIP, suggesting that a longer duration of institutional care may limit the extent of recovery possible. However, these cross-study comparisons are complicated by many other considerations (e.g., cohorts who grew up in different countries, different comparison groups, measurement differences) and should therefore be interpreted cautiously.

MECHANISMS OF LONG-TERM RISK

Next, we discuss factors that explain at least partially the association between early deprivation and continued risk of psychopathology from 8 to 16 years, operationalized as the difference between children in the EIG and children in the NIG. The EIG includes the CAUG and FCG since both were exposed to institutional deprivation despite differing care trajectories and RCT assignment. These mechanisms are summarized in Figure 2.

One contextual predictor of later psychopathology among those exposed to early deprivation is the quality of the later caregiving environment. Among the EIG children, while caregiving quality based on staff reports was often satisfactory (particularly for those in foster care), it was lower, on average, than that of the children in the NIG at 8, 12, and 16 years. In turn, lower caregiving quality was associated with higher levels of internalizing and externalizing problems during this period (Colich et al., 2021). This association persisted even though more than half of the CAUG children and more than three-quarters of the FCG children were in some sort of family placement at each time point. Thus, even after removal from institutional care, caregiving quality remained lower than that of the NIG. This may be due to the challenges associated with caring for youth exposed to such profound early deprivation and the difficulties they often continue to experience after they leave the institutions. These factors may give rise to more parent–child conflict, more parenting stress, or less optimal forms of parenting that contribute to increased risk for psychopathology (Yan et al., 2021). In addition to poor caregiving quality, placement instability is also hazardous. Specifically, FCG adolescents in disrupted placements had higher rates of psychiatric disorders at 12 and 16 years than adolescents in both the NIG and the FCG who were in stable placements (Humphreys et al., 2015, 2020). Thus, both poor quality of care and disrupted care elevated the risk of continued mental health difficulties for those exposed to early deprivation.

Altered cognitive functioning is another mechanism linking early deprivation to long-term risk of psychopathology during adolescence. One of the most reliable mediators of this risk is executive function. At 8 years, reduced performance on working memory and response inhibition tasks mediated the effect of institutional rearing on ADHD symptoms, but not on internalizing or externalizing problems (Tibu et al., 2016a). This effect was replicated for working memory at 12 years (Tibu et al., 2016b). More recently, we showed that reduced memory and executive function from 8 to 12 years mediated risk of transdiagnostic psychopathology at 16 years (Wade, Zeanah, et al., 2020a). These results are consistent with the idea that rapid development of executive function during adolescence may play an important role in shaping adaptive socioemotional and academic outcomes (Poon, 2018), and that executive processes may be significantly disrupted by early deprivation and more challenging to remediate.

Another pathway toward the continued risk of psychopathology during adolescence is difficulties with social communication, skills crucial for managing social interactions at this time. Reduced social communication skills at 8–10 years in the domains of reciprocal social interaction, communication, and repetitive and stereotyped behaviors partially mediated the association between early deprivation and general psychopathology at 16 years (Wade, Zeanah, et al., 2020b). This is consistent with findings from the ERA that problems with social communication are among the most persistently elevated from childhood to early adulthood (Sonuga-Barke et al., 2017) and forecast long-term emotional problems (Golm et al., 2020). Such difficulties may heighten the risk of psychopathology by limiting opportunities for interpersonal engagement and the scaffolding of self-regulatory abilities that facilitate adaptive coping in the face of stress. Encouragingly, social communication difficulties were partially remediated by family-based foster care (Wade, Zeanah, et al., 2020b), suggesting this is a mechanism of both long-term risk and recovery in mental health.

Finally, alterations in brain structure and function may underpin a heightened risk of psychopathology following early deprivation. Reduced cortical thickness in regions including the orbitofrontal cortex, insula, inferior parietal cortex, and superior temporal gyrus―regions generally involved in salience detection and cognitive control (Menon & D’Esposito, 2022)―mediated the association between institutional rearing and ADHD symptoms at 8–10 years (McLaughlin et al., 2014). At the same age, deprivation-r elated alterations in white matter integrity of the external capsule (frontostriatal circuitry) and corpus callosum (interhemispheric communication) partially mediated the effect of institutional deprivation on internalizing problems (Bick et al., 2017). With respect to brain function, persistent alterations in electroencephalogram power have been demonstrated among children in the CAUG through 16 years (Debnath et al., 2020), and in a recent study, institutional deprivation was associated with reduced mediofrontal theta power―a neural correlate of cognitive control―which in was turn associated with elevated general psychopathology at 16 years (Buzzell et al., 2020).

To summarize, these findings underscore three primary modes of long-term risk propagation following early deprivation―the first centered on poor-quality or disrupted caregiving as a result of deprivation, a second focused on social functioning and communication, and a third focused on executive function and its underlying neurobiology. Limited evidence that these domains mediate intervention benefits of foster care suggest that they may constitute mechanisms of long-term mental health risk in the aftermath of early deprivation.

IMPLICATIONS AND DIRECTIONS

The BEIP was launched more than 20 years ago, and an early adulthood assessment is currently under way. The study is positioned to answer many remaining questions in the years ahead. First, building on work on pubertal recalibration (Gunnar et al., 2019), we hope to answer the central question of what the consequences of recalibration are for mental health. Recent work suggests that, despite what appears to be an adaptative process during adolescence, recalibration may have negative effects on mental health (Perry et al., 2022). The BEIP is well-situated not only to replicate this work, but to determine the downstream impact of recalibration during early adulthood and use the RCT design to uncover whether early experience moderates these effects.

Second, recent work from the ERA has highlighted differences in brain structure during early adulthood between children raised institutions and those not raised in institutions (Mackes et al., 2020). Individuals with a history of deprivation have a thicker cortex in the inferior temporal gyrus than do noninstitutionalized individuals, and greater duration of deprivation is linked to greater volume and area of medial prefrontal regions. These findings raise the possibility that, among youth raised in institutions, there may be alterations in the typical pruning process that occurs from childhood to adolescence—however, this cross-sectional study was unable to test this possibility directly. In contrast, the BEIP has baseline structural data on participants at 8 years, processed data at 16 years, and planned MRI scans at 21–22 years. Therefore, we will be able to explicitly examine trajectories to test for altered processes of neurodevelopment from mid-childhood to early adulthood.

Third, we know little about the experience of other forms of violence and maltreatment among children and youth raised in large, impersonal institutions or during subsequent placements. We are completing comprehensive assessments of other forms of violence, victimization, and abuse during our early adult follow-up. This work is crucial to understand how early deprivation intersects with other forms of maltreatment in forecasting long-term mental health problems.

CONCLUSION

The results from the BEIP implicate the importance of early social relationships, and the centrality of stable and supportive family care during childhood and adolescence. If there is a single most important legacy to our work, it is to underscore the urgent need to end institutional rearing and promote high-quality and stable family placements, along with evidence-based interventions that target the key mechanisms of risk and recovery for neglected young children throughout the world.

This is especially important in light of the fact that the COVID-19 pandemic has produced more than 5 million new orphans globally over its first 20 months (Unwin et al., 2022). Whether the result of COVID-associated orphanhood, forced parent–child separation in the context of international immigration (Humphreys, 2019), or child abandonment due to sociopolitical factors such as those experienced by children in the BEIP, children who have lost their caregivers require stable, safe, stimulating, and sensitive care to develop along an optimal trajectory. Results from the BEIP provide a strong empirical foundation on which to respond to these local and global problems and safeguard the well-being of children and adolescents.

Supplementary Material

FUNDING INFORMATION

Preparation of the article was funded by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, the National Institutes of Health, the National Institute of Mental Health (R01MH091363), the Binder Family Foundation, and the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation.

Funding information

Binder Family Foundation, Grant/ Award Number: John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation and R01MH091363

Abbreviations:

- ADHD

Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder

- BEIP

Bucharest Early Intervention Project

- CAUG

Care-as-usual group

- EIG

Ever-institutionalized group

- ERA

English and Romanian Adoptees

- FCG

Foster care group

- MRI

Magnetic resonance imaging

- NIG

Never-institutionalized group

- RCT

Randomized controlled trial

Footnotes

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

Additional supporting information can be found online in the Supporting Information section at the end of this article.

REFERENCES

- Bick J, Fox N, Zeanah C, & Nelson CA (2017). Early deprivation, atypical brain development, and internalizing symptoms in late childhood. Neuroscience, 342, 140–153. 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2015.09.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blakemore S-J (2019). Adolescence and mental health. The Lancet, 393(10185), 2030–2031. 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)31013-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bos K, Zeanah CH, Fox NA, Drury SS, McLaughlin KA, & Nelson CA (2011). Psychiatric outcomes in young children with a history of institutionalization. Harvard Review of Psychiatry, 19(1), 15–24. 10.3109/10673229.2011.549773 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buzzell GA, Troller-Renfree SV, Wade M, Debnath R, Morales S, Bowers ME, Zeanah CH, Nelson CA, & Fox NA (2020). Adolescent cognitive control and mediofrontal theta oscillations are disrupted by neglect: Associations with transdiagnostic risk for psychopathology in a randomized controlled trial. Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience, 43, 100777. 10.1016/j.dcn.2020.100777 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colich NL, Sheridan MA, Humphreys KL, Wade M, Tibu F, Nelson CA, Zeanah CH, Fox NA, & McLaughlin KA (2021). Heightened sensitivity to the caregiving environment during adolescence: Implications for recovery following early-life adversity. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 62(8), 937–948. 10.1111/jcpp.13347 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Debnath R, Tang A, Zeanah CH, Nelson CA, & Fox NA (2020). The long-term effects of institutional rearing, foster care intervention and disruptions in care on brain electrical activity in adolescence. Developmental Science, 23(1), e12872. 10.1111/desc.12872 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desmond C, Watt K, Saha A, Huang J, & Lu C (2020). Prevalence and number of children living in institutional care: Global, regional, and country estimates. The Lancet Child & Adolescent Health, 4(5), 370–377. 10.1016/S2352-4642(20)30022-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golm D, Maughan B, Barker ED, Hill J, Kennedy M, Knights N, Kreppner J, Kumsta R, Schlotz W, Rutter M, & Sonuga-Barke EJS (2020). Why does early childhood deprivation increase the risk for depression and anxiety in adulthood? A developmental cascade model. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 61(9), 1043–1053. 10.1111/jcpp.13205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunnar MR, DePasquale CE, Reid BM, Donzella B, & Miller BS (2019). Pubertal stress recalibration reverses the effects of early life stress in postinstitutionalized children. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 116(48), 23984–23988. 10.1073/pnas.190969911 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guyon-Harris KL, Humphreys KL, Degnan K, Fox NA, Nelson CA, & Zeanah CH (2019). A prospective longitudinal study of reactive attachment disorder following early institutional care: Considering variable-and person-centered approaches. Attachment & Human Development, 21(2), 95–110. 10.1080/14616734.2018.1499208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guyon-Harris KL, Humphreys KL, Fox NA, Nelson CA, & Zeanah CH (2018). Course of disinhibited social engagement disorder from early childhood to early adolescence. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 57(5), 329–335. 10.1016/j.jaac.2018.02.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howland MA, Donzella B, Miller BS, & Gunnar MR (2020). Pubertal recalibration of cortisol-DHEA coupling in previously-institutionalized children. Hormones and Behavior, 125, 104816. 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2020.104816 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humphreys KL (2019). Future directions in the study and treatment of parent-child separation. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 48(1), 166–178. 10.1080/15374416.2018.1534209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humphreys KL, Gleason MM, Drury SS, Miron D, Nelson CA, Fox NA, & Zeanah CH (2015). Effects of institutional rearing and foster care on psychopathology at age 12 years in Romania: Follow-up of an open, randomised controlled trial. The Lancet Psychiatry, 2(7), 625–634. 10.1016/S2215-0366(15)00095-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humphreys KL, Guyon-Harris KL, Tibu F, Wade M, Nelson CA, Fox NA, & Zeanah CH (2020). Psychiatric outcomes following severe deprivation in early childhood: Follow-up of a randomized controlled trial at age 16. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 88(12), 1079–1090. 10.1037/ccp0000613 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humphreys KL, Nelson CA, Fox NA, & Zeanah CH (2017). Signs of reactive attachment disorder and disinhibited social engagement disorder at age 12 years: Effects of institutional care history and high-quality foster care. Development and Psychopathology, 29(2), 675–684. 10.1017/S0954579417000256 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackes NK, Golm D, Sarkar S, Kumsta R, Rutter M, Fairchild G, Mehta MA, Sonuga-Barke E, & ERA Young Adult Follow-U p Team. (2020). Early deprivation is associated with alterations in adult brain structure despite subsequent environmental enrichment. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 117(1), 641–649. 10.1073/pnas.1911264116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCrory EJ, Gerin MI, & Viding E (2017). Annual research review: Childhood maltreatment, latent vulnerability and the shift to preventative psychiatry–the contribution of functional brain imaging. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 58(4), 338–357. 10.1111/jcpp.12713 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin KA, Sheridan MA, Tibu F, Fox NA, Zeanah CH, & Nelson CA (2015). Causal effects of the early caregiving environment on development of stress response systems in children. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 112(18), 5637–5642. 10.1073/pnas.1423363112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin KA, Sheridan MA, Winter W, Fox NA, Zeanah CH, & Nelson CA (2014). Widespread reductions in cortical thickness following severe early-life deprivation: A neurodevelopmental pathway to attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Biological Psychiatry, 76(8), 629–638. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2013.08.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menon V, & D’Esposito M (2022). The role of PFC networks in cognitive control and executive function. Neuropsychopharmacology, 47(1), 90–103. 10.1038/s41386-021-01152-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukerji CE, Wade M, Fox NA, Zeanah CH, & Nelson CA (2021). Growth in self-regulation over the course of adolescence mediates the effects of foster care on psychopathology in previously institutionalized children: A randomized clinical trial. Clinical Psychological Science, 9(5), 810–822. 10.1177/2167702621993887 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson CA, Fox NA, & Zeanah CH (2014). Romania’s abandoned children: Deprivation, brain development and the struggle for recovery. Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson CA, & Gabard-Durnam LJ (2020). Early adversity and critical periods: Neurodevelopmental consequences of violating the expectable environment. Trends in Neurosciences, 43(3), 133–143. 10.1016/j.tins.2020.01.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson CA III, Zeanah CH, & Fox NA (2019). How early experience shapes human development: The case of psychosocial deprivation. Neural Plasticity, 2019, 1676285. 10.1155/2019/1676285 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry NB, Donzella B, & Gunnar MR (2022). Pubertal stress recalibration and later social and emotional adjustment among adolescents: The role of early life stress. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 135, 105578. 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2021.105578 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poon K (2018). Hot and cool executive functions in adolescence: Development and contributions to important developmental outcomes. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 2311. 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.02311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosapepe JC (2001). Half way home: Romania’s abandoned children ten years after the revolution. Report to Americans from the U.S. [Google Scholar]

- Rutter M, Colvert E, Kreppner J, Beckett C, Castle J, Groothues C, Hawkins A, O’Connor TG, Stevens SE, & Sonuga-Barke EJ (2007). Early adolescent outcomes for institutionally-deprived and non-deprived adoptees. I: Disinhibited attachment. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 48(1), 17–30. 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2006.01688.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheridan MA, McLaughlin KA, Winter W, Fox N, Zeanah C, & Nelson CA (2018). Early deprivation disruption of associative learning is a developmental pathway to depression and social problems. Nature Communications, 9(1), 2216. 10.1038/s41467-018-04381-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smyke AT, Zeanah CH, Gleason MM, Drury SS, Fox NA, Nelson CA, & Guthrie D (2012). A randomized controlled trial comparing foster care and institutional care for children with signs of reactive attachment disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry, 169(5), 508–514. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.11050748 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonuga-Barke EJS, Kennedy M, Kumsta R, Knights N, Golm D, Rutter M, Maughan B, Schlotz W, & Kreppner J (2017). Child-to-adult neurodevelopmental and mental health trajectories after early life deprivation: The young adult follow-up of the longitudinal English and Romanian Adoptees study. The Lancet, 389(10078), 1539–1548. 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30045-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang A, Wade M, Fox NA, Nelson CA, Zeanah CH, & Slopen N (2020). The prospective association between stressful life events and inflammation among adolescents with a history of early institutional rearing. Development and Psychopathology, 32(5), 1715–1724. 10.1017/S0954579420001479 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tibu F, Sheridan MA, McLaughlin KA, Nelson CA, Fox NA, & Zeanah CH (2016a). Disruptions of working memory and inhibition mediate the association between exposure to institutionalization and symptoms of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Psychological Medicine, 46(3), 529–541. 10.1017/S0033291715002020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tibu F, Sheridan MA, McLaughlin KA, Nelson CA, Fox NA, & Zeanah CH (2016b). Reduced working memory mediates the link between early institutional rearing and symptoms of ADHD at 12 years. Frontiers in Psychology, 7, 1850. 10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01850 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families, (2019). Child maltreatment 2019. https://www.acf.hhs.gov/cb/research-data-technology/statistics-research/child-maltreatment

- Unwin HJT, Hillis S, Cluver L, Flaxman S, Goldman PS, Butchart A, Bachman G, Rawlings L, Donnelly CA, Rattmann O, Green P, Nelson CA, Blenkinsop A, Bhatt S, Desmond C, Villaveces A, & Sherr L (2022). Global, regional, and national minimum estimates of children affected by COVID-19-associated orphanhood and caregiver death, by age and family circumstance up to Oct 31, 2021: An updated modelling study. The Lancet Child & Adolescent Health, 6(4), 249–259. 10.1016/S2352-4642(22)00005-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van IJzendoorn MH, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, Duschinsky R, Fox NA, Goldman PS, Gunnar MR, Johnson DE, Nelson CA, Reijman S, Skinner GCM, Zeanah CH, & Sonuga-Barke EJS (2020). Institutionalisation and deinstitutionalisation of children 1: A systematic and integrative review of evidence regarding effects on development. The Lancet Psychiatry, 7(8), 703–720. 10.1016/S2215-0366(19)30399-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wade M, Fox NA, Zeanah CH, & Nelson CA (2018). Effect of foster care intervention on trajectories of general and specific psychopathology among children with histories of institutional rearing. JAMA Psychiatry, 75(11), 1137–1145. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2018.2556 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wade M, Fox NA, Zeanah CH, & Nelson CA (2019). Long-term effects of institutional rearing, foster care, and brain activity on memory and executive functioning. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 116(5), 1808–1813. 10.1073/pnas.1809145116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wade M, Sheridan MA, Zeanah CH, Fox NA, Nelson CA, & McLaughlin KA (2020). Environmental determinants of physiological reactivity to stress: The interacting effects of early life deprivation, caregiving quality, and stressful life events. Development and Psychopathology, 32(5), 1732–1742. 10.1017/S0954579420001327 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wade M, Zeanah CH, Fox NA, & Nelson CA (2020a). Global deficits in executive functioning are transdiagnostic mediators between severe childhood neglect and psychopathology in adolescence. Psychological Medicine, 50(10), 1687–1694. 10.1017/S0033291719001764 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wade M, Zeanah CH, Fox NA, & Nelson CA (2020b). Social communication deficits following early-life deprivation and relation to psychopathology: A randomized clinical trial of foster care. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 61(12), 1360–1369. 10.1111/jcpp.13222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wade M, Zeanah CH, Fox NA, Tibu F, Ciolan LE, & Nelson CA (2019). Stress sensitization among severely neglected children and protection by social enrichment. Nature Communications, 10(1), 5771. 10.1038/s41467-019-13622-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan N, Ansari A, & Peng P (2021). Reconsidering the relation between parental functioning and child externalizing behaviors: A meta-analysis on child-driven effects. Journal of Family Psychology, 35(2), 225–235. 10.1037/fam0000805 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeanah CH, Nelson CA, Fox NA, Smyke AT, Marshall P, Parker SW, & Koga S (2003). Designing research to study the effects of institutionalization on brain and behavioral development: The Bucharest Early Intervention Project. Development and Psychopathology, 15(4), 885–907. 10.1017/s0954579403000452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.