Abstract

Although early therapeutic research on psychedelics dates back to the 1940s, this field of investigation was met with many cultural and legal challenges in the 1970s. Over the past two decades, clinical trials using psychedelics have resumed. Therefore, the goal of this study was to (1) better characterize the recent uptrend in psychedelics in clinical trials and (2) identify areas where potentially new clinical trials could be initiated to help in the treatment of widely prevalent medical disorders. A systematic search was conducted on the clinicaltrials.gov database for all registered clinical trials examining the use of psychedelic drugs and was both qualitatively and quantitatively assessed. Analysis of recent studies registered in clinicaltrials.gov was performed using Pearson’s correlation coefficient testing. Statistical analysis and visualization were performed using R software. In totality, 105 clinical trials met this study’s inclusion criteria. The recent uptrend in registered clinical trials studying psychedelics (p = 0.002) was similar to the uptrend in total registered clinical trials in the registry (p < 0.001). All trials took place from 2007 to 2020, with 77.1% of studies starting in 2017 or later. A majority of clinical trials were in phase 1 (53.3%) or phase 2 (25.7%). Common disorders treated include substance addiction, post-traumatic stress disorder, and major depressive disorder. Potential research gaps include studying psychedelics as a potential option for symptomatic treatment during opioid tapering. There appears to be a recent uptrend in registered clinical trials studying psychedelics, which is similar to the recent increase in overall trials registered. Potentially, more studies could be performed to evaluate the potential of psychedelics for symptomatic treatment during opioid tapering and depression refractory to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors.

Keywords: psilocybin, post traumatic stress disorder, mdma, major depressive disorder, clinical trials

Introduction and background

Although hallucinogens have been used as spiritual tools for millennia in non-Western cultures [1,2], they were not introduced into the Western scientific community until 1896 when Arthur Heffter, a German pharmacologist, isolated mescaline from peyote [3]. After this period in time, the study of psychedelics became much more robust throughout the mid-1900s with the work of Albert Hofmann who studied the psychoactive properties of LSD (lysergic acid diethylamide) and psilocybin [4,5]. Researchers began to study the potential therapeutic uses of psychedelics for depression, alcoholism, and palliative care. LSD became a model psychedelic for these therapeutic developments [6,7]. Ultimately, tens of thousands of patients were treated in the 1950s and 1960s, predominantly in the psychotherapy setting [8,9]. Despite minimal adverse events [10], most psychedelics were later criminalized and deemed schedule 1 drugs by the United Nations Convention on Psychotropic Substances in 1971 due to their hypothesized close association with cultural turmoil and anti-Vietnam war politics of this period. These stringent regulations stigmatized psychedelic research, leaving investigators discouraged in the wake of these rapid changes [11]. Additionally, some authors argue that the decline of research into psychedelics was more a result of the difficulty to establish efficacy of the psychedelics given their mechanism of action and its clash with controlled trial methodologies at the time [12].

In the last two decades, there has been a resurgence of psychedelics research that has broadly encompassed the fields of neuroimaging [13-21], psychopharmacology [18,22-24], and psychology [25-31]. Focused mostly on psilocybin and MDMA (methylenedioxymethamphetamine), researchers are now considering the potential of these drugs being used to treat a variety of different psychiatric and neurological conditions such as addiction, pain, depression, end-of-life anxiety, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). For example, one study published in 2016 by Roland Griffiths and his team at Johns Hopkins was a randomized, double-blind, crossover trial. This study gave cancer patients with poor prognoses and associated anxiety/depression either a high dose of psilocybin or a low dose, functioning as a placebo [32]. Results showed decreases in both clinician- and self-rated measures of depressed mood and anxiety among the participants in the high-dose group, along with a general increase in quality of life.

Cannabis, and specifically tetrahydracannibidinol (THC), also plays a major role in this field of research. A recent report published by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine provided a comprehensive review of over 20 years of cannabis research, considering more than 10,000 scientific abstracts [33]. In this report, a committee discussed the health impacts of cannabis and cannabis-derived products, ranging from therapeutic properties to increased risks for causing cancers, respiratory diseases, and psychological disorders.

Despite the promising results that these investigations have yielded, there are still many barriers to advancing psychedelics research. Stigma, legality, and cultural interest all influence the amount of research that can be conducted in any field, but is especially prominent in the area of psychedelics. Ultimately, the history of psychedelics all but requires promising results to be accepted with cautious optimism, leaving researchers, clinicians, and the general public alike urging for a greater body of research into the therapy and safety of these drugs. The purpose of this study is to review the current scope/character of current psychedelic drug clinical trials, identify current cultural/legal challenges hindering progress in this field, and discuss potential avenues for future investigation.

Review

Methods

This analysis of clinical trials studying psychedelic drugs was conducted using the ClinicalTrials.gov database, a database that is supported by the National Library of Medicine through the National Institutes of Health (Bethesda, Maryland, USA). This database contains more than 380,000 research studies conducted throughout the United States and in 220 countries. This database can be accessed at https://clinicaltrials.gov/. Information about trials is submitted by the sponsor or lead investigator for the purposes of research integrity by establishing prespecified primary outcomes. In addition, this registration of clinical trials also ensures publication of negative or null findings in addition to positive findings. This database is continually updated as the study progresses while updating the number of participants and preliminary results.

The authors queried the database using the input “psychedelic” in the “other terms” parameter. The search was made on May 1, 2021. Of the studies identified, those that had been suspended, terminated, withdrawn, or otherwise unknown statuses were excluded. For the studies that met the inclusion criteria, the following data were extracted: identifier number, title, recruitment status, condition or disease, study type, intervention, primary purpose, clinical phase, estimated number of participants, year of study initiation, country of origin, and sponsoring institution. Studies including cannabidiol (CBD) and kratom were excluded from the study.

Descriptive statistics were used for the initial summary of the retrieved data. Statistical analysis was performed with R software (R Core Team, Vienna, Austria) using the Pearson’s correlation test to discover if there were any uptrends in clinical trials with each successive year included in the study. This was performed for both the total number of clinical trials established on the clinicaltrials.gov website and to the clinical trials of psychedelics retrieved from the search. A p-value of 0.05 was used for establishing statistical significance, in addition to 95% confidence intervals. When analyzing for increasing trends in clinical trials, the year 2020 was omitted due to the reduced amount of medical research as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. Visualization was performed using R software.

Results

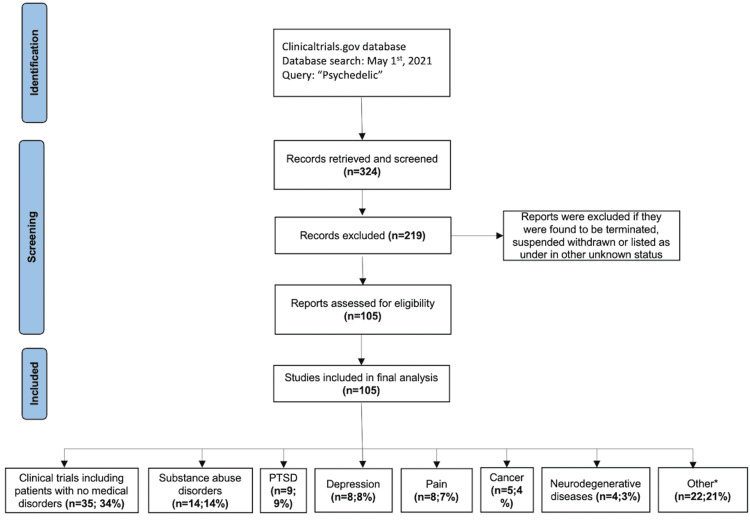

The search results included 105 studies that met this study’s inclusion criteria (Appendix A). A flowsheet of the inclusion/exclusion criteria is depicted in Figure 1. In total, 103 studies (98.1%) were interventional and two (1.9%) were observational, including one (1%) cross-sectional study and one (1%) prospective study. All trials took place from 2007 to 2020, with 81 (77.1%) studies starting in 2017 or later. Sixty-one trials had an enrollment between 0 and 50 participants (57%), 24 had a sample size between 51 and 100 participants (22.4%), 19 had a sample size between 101 and 500 participants (17.8%), and one had a sample size of >501 participants (0.9%). The mean number of study participants was 117 in all trials. No trials were completed. However, 19 (18.1%) were active, 63 (60%) were recruiting, one (1%) was enrolling through invitation, and 22 (21%) were not yet recruiting.

Figure 1. Results of the clinical trials search strategy. Flowchart depicts the search and screening process used to identify relevant clinical trials.

PTSD, post-traumatic stress disorder

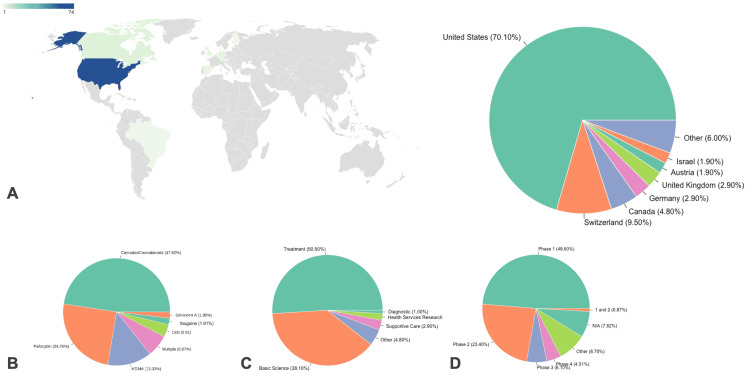

Country of Origin and Sponsoring Institutions

The United States of America has the most clinical trials, 74 (70.5%), with the rest originating in Switzerland (9.5%), Canada (4.8%), and several other countries (Table 1; Figure 2A). These studies were largely sponsored by Yale University (21.9%, n = 23), followed by Johns Hopkins University (10.5%, n = 11) and the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies (MAPS) (8.6%, n = 9).

Table 1. Characteristics of clinical trials included in this analysis.

| Characteristic | Number of trials | Percentage of all trials |

| Primary purpose | ||

| Treatment | 53 | 50.50% |

| Basic science | 40 | 38.10% |

| Other | 5 | 4.80% |

| Supportive care | 3 | 2.90% |

| Health services research | 2 | 1.90% |

| Diagnostic | 1 | 1.00% |

| Phase | ||

| 1 | 56 | 53.30% |

| 2 | 27 | 25.70% |

| 3 | 7 | 6.70% |

| 4 | 5 | 4.80% |

| Other | 10 | 9.50% |

| N/A | 9 | 8.60% |

| 1 and 2 | 1 | 1.00% |

| Country of origin | ||

| United States | 74 | 70.50% |

| Switzerland | 10 | 9.50% |

| Canada | 5 | 4.80% |

| Germany | 3 | 2.90% |

| United Kingdom | 3 | 2.90% |

| Austria | 2 | 1.90% |

| Israel | 2 | 1.90% |

| Brazil | 1 | 1.00% |

| Denmark | 1 | 1.00% |

| Finland | 1 | 1.00% |

| The Netherlands | 1 | 1.00% |

| Spain | 1 | 1.00% |

| West Indies | 1 | 1.00% |

Figure 2. Characteristics of included clinical trials. (A) Clinical trials by nationality. Other includes clinical trials in the countries of Brazil, Denmark, Finland, Netherlands, Spain, and the West Indies. (B) Psychedelic drugs under analysis in each clinical trial. (C) Type of clinical trial. (D) Stage of currently reported clinical trials underway.

1 and 2 refer to trials including patients in both phase 1 and phase 2, respectively. N/A refers to trials with no listed phase. Other refers to exploratory trials before phase 1.

Types of Psychedelics

The most commonly studies psychedelics were cannabinoids (47.62%, n = 50), and psilocybin (24.76%, n = 26). MDMA was also used (13.33%, n = 14). Other less common psychedelics were also studied including LSD, ibogaine hydrochloride, and salvinorin A (Figure 2B).

Purpose of Included Clinical Trials

The primary purposes of these trials were based on the following: treatment (50.5%, n = 53), basic science (38.1%, n = 40), other/unspecified (4.8%, n = 5), supportive care (2.9%, n = 3), health services research (1.9%, n = 2), and diagnostic (1.0%, n = 1) (Figure 2C).

Phases of Included Clinical Trials

The majority of the clinical trials are in phase 1 (53.3%, n = 56) or phase 2 (25.7%, n = 27). In addition, three studies are in phase 3 (2.9%) and five (4.8%) studies are in phase 4. An overview of study characteristics is depicted in Figure 2D.

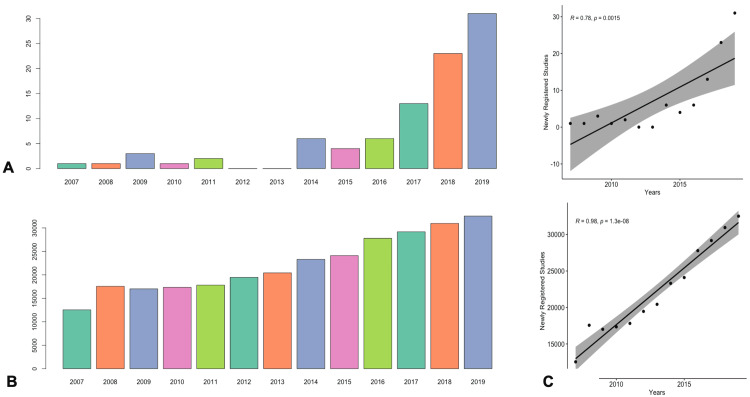

Statistical Analysis

Both the number of clinical trials specifically measuring psychedelics and the number of trials in the overall registry were found to be increasing over time (Figures 3A, 3B). Pearson’s correlation testing revealed an uptrend with an increasing number of psychedelic clinical trials occurring each year from 2007 to 2019 (r = 0.784 [95% CI: 0.411-0.932], p = 0.002). The resulting t-test statistic value was 4.192. In addition, there was also an increase in the total number of registered clinical trials each year as an entirety (r = 0.98 [95% CI: 0.919-0.993], p < 0.01). The resulting t-test statistic value was 14.832 (Figure 3C).

Figure 3. Amount of both psychedelic clinical trials and total clinical trials in the clinicaltrials.gov registry have increased over time. (A) Bar plot depicting the number of newly registered psychedelic-specific studies each year. (B) Bar plot depicting the number of newly registered studies in the clinicaltrials.gov database overall each year. (C) Pearson correlation analysis finding statistically significant association of increasing psychedelic studies per year in addition to overall registered trials in the clinicaltrials.gov registry.

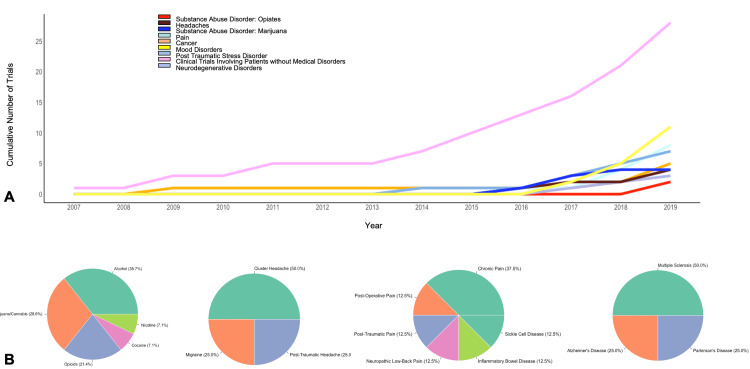

Condition or Disease

Healthy participants made up the largest group, who were studied in 35 (33.3%) trials, with 30 of them being phase 1 trials (Table 2). The most commonly studied disorders were substance use disorders, with 14 studies (13.3%). More specifically, there were five alcohol, four marijuana/cannabis, three opioids, one cocaine, and one nicotine clinical trial regarding substance use. PTSD and depression were the next most frequently studied disorders, having nine (8.6%) and eight (7.6%) clinical trials, respectively. Eight clinical trials were conducted regarding pain, with chronic pain as the most studied (2.9%, n = 3). Studies regarding cancer/cancer-related symptoms accounted for five of the results. Degenerative disorders, consisting of multiple sclerosis, Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, and mild cognitive impairment had a total of four (3.7%) clinical trials. Headache disorders had a total of four (3.7%) clinical trials included as well. Three (2.8%) studies were included about psychosis/schizophrenia. There were also four trials where multiple conditions or diseases were studied, most commonly with depression and related disorders (Figures 4A, 4B).

Table 2. Number of clinical trials by condition or disease.

PTSD, post-traumatic stress disorder; OCD, obsessive-compulsive disorder; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus

| Condition or disease | Number of trials | Percentage of all trials |

| Healthy | 35 | 33.3% |

| Substance use disorder | 14 | 13.3% |

| Alcohol | 5 | 4.8% |

| Marijuana/cannabis | 4 | 3.8% |

| Opioids | 3 | 2.9% |

| Cocaine | 1 | 1.0% |

| Nicotine | 1 | 1.0% |

| PTSD | 9 | 8.6% |

| Depression | 8 | 7.6% |

| Pain | 8 | 7.6% |

| Chronic pain | 3 | 2.9% |

| Post-operative pain | 1 | 1.0% |

| Post-traumatic pain | 1 | 1.0% |

| Neuropathic low back pain | 1 | 1.0% |

| Inflammatory bowel disease | 1 | 1.0% |

| Sickle cell disease | 1 | 1.0% |

| Cancer | 5 | 4.8% |

| Degenerative diseases | 4 | 3.8% |

| Multiple sclerosis | 2 | 1.9% |

| Alzheimer's disease | 1 | 1.0% |

| Parkinson's disease | 1 | 1.0% |

| Headache disorders | 4 | 3.8% |

| Cluster headache | 2 | 1.9% |

| Migraine | 1 | 1.0% |

| Post-traumatic headache | 1 | 1.0% |

| Multiple conditions or diseases | 4 | 3.8% |

| Depression, Anxiety, PTSD | 1 | 1.0% |

| Depression, depressive symptoms, Alzheimer's disease, mild cognitive impairment | 1 | 1.0% |

| Distress/grief, depression | 1 | 1.0% |

| Tourette syndrome, tic disorder | 1 | 1.0% |

| Psychosis/schizophrenia | 3 | 2.9% |

| OCD | 2 | 1.9% |

| Anorexia nervosa | 1 | 1.0% |

| Anxiety disorders | 1 | 1.0% |

| Autism spectrum disorder | 1 | 1.0% |

| Bipolar disorder | 1 | 1.0% |

| Hepatic impairment | 1 | 1.0% |

| HIV | 1 | 1.0% |

| Obstructive sleep apnea | 1 | 1.0% |

| Tourette syndrome | 1 | 1.0% |

| Trichotillomania | 1 | 1.0% |

Figure 4. Number of psychedelic clinical trials per treating condition. (A) Line plot depicting cumulative number of clinical trials over time stratified by medical disorders. (B) Pie charts depicting percentage of psychedelic studies in the treatment of substance abuse disorder, headaches, pain, and neurodegenerative disorders.

Study Interventions

Nearly half of all clinical trials were conducted with cannabis/cannabinoids as the study intervention (47.6%, n = 50) (Table 3). Dronabinol, a synthetic substance containing compounds from the cannabis plant, was used in 23 of those studies. The interventions consisted of psilocybin, MDMA, and LSD in 26 (24.8%), 14 (13.3%), and four (3.8%) studies, respectively. There were seven clinical trials that investigated all or a combination of psychedelic substances, and in these psilocybin was most commonly administered alongside other drugs (n = 3).

Table 3. Number of clinical trials by intervention.

THC, tetrahydracannibidinol; CBD, cannabidiol; THC, tetrahydracannibidinol; PEA, palmitoylethanolamide; MDMA, methylenedioxymethamphetamine; LSD, lysergic acid diethylamide; SSRI, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors

| Study intervention | Number of trials | Percentage of trials |

| Cannabis/cannabinoids | 50 | 47.6% |

| Dronabinol | 23 | 21.9% |

| THC | 12 | 11.4% |

| Dronabinol/CBD | 3 | 2.9% |

| THC/CBD | 3 | 2.9% |

| Nabilone | 2 | 1.9% |

| Nabiximols | 2 | 1.9% |

| THC/terpenes (alpha-pinene, limonene) | 2 | 1.9% |

| THX-110 (dronabinol + PEA) | 2 | 1.9% |

| Inje cocktail, THC cannabis extract, THC/CBD cannabis extract | 1 | 1.0% |

| Psilocybin | 26 | 24.8% |

| MDMA | 14 | 13.3% |

| Multiple interventions | 7 | 6.7% |

| All psychedelics | 1 | 1.0% |

| MDMA, methamphetamine | 1 | 1.0% |

| Psilocybin, ketamine | 1 | 1.0% |

| Psilocybin, LSD | 1 | 1.0% |

| Psilocybin, SSRI (escitalopram) | 1 | 1.0% |

| THC, ketamine | 1 | 1.0% |

| Dronabinol, ethanol | 1 | 1.0% |

| LSD | 4 | 3.8% |

| Ibogaine hydrochloride | 2 | 1.9% |

| Salvinorin A | 2 | 1.9% |

Discussion

The sheer number of recently established current clinical trials reveals that research is increasing in this area, especially since 2017 [34]. Statistical analysis of all trials registered into the database, however, suggests an increasing amount of studies in all fields. Thus, the increasing trend in psychedelic intervention studies could represent just improved registration of clinical trials overall by all medical researchers.

Furthermore, it is evident that many of these studies are still in their infancy. Many researchers are still facing the challenge of first establishing the safety of hallucinogenic drugs. Thus, the fact that more than 50% of the current trials are phase 1 is not surprising. This is especially imperative as the schedule 1 status of many psychedelic substances requires researchers to firmly establish the safety of the drugs on healthy subjects before moving on to their potential therapeutic impacts.

Conditions or Diseases

With the exceptionally heavy burden of addiction and overdose rates in the United States [34], and in the wake of the current opioid epidemic, it was fitting that substance use disorders overall were the most commonly studied conditions in current psychedelic clinical trials. However, only three trials focused specifically on opioid substance use disorder. Two of the studies are testing psychedelics as maintenance therapy along with buprenorphine/naloxone, while one clinical trial is testing psychedelics as an adjunct with methadone withdrawal. This is a large gap in this field of research as approximately 70,000 Americans suffered from overdoses causing fatalities in 2018, and two-thirds of those were from opioids [35,36]. Thus, successful treatments in this realm of psychedelic research could elicit a substantial impact on a psychiatric disorder with rapidly increasing prevalence and rates of mortality. Ibogaine, a naturally occurring alkaloid for which there are two clinical trials underway, has shown promise in reducing alcohol and opioid cravings and withdrawals; however, its application is limited by its hallucinogenic and arrhythmogenic adverse effects [37]. Cameron et al. recently formulated an analog, tabernanthalog (TBG), that addresses both issues, which sets it apart as a candidate for substance use disorder clinical trials [3].

The next most studied disorders are PTSD and major depressive disorder, as both have nine and eight studies currently underway, respectively. There is already early evidence that psychedelic treatment could be successful in treating these disorders [36-39]. It is important to consider that the term “post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)” was also not a term before its first appearance in 1980, when it was initially described in the third edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Therefore, this could potentially have affected our search, thus not identifying a significant number of trials before the term became incorporated into mainstream use and study. However, trauma-based research could potentially have still been studied and registered using different terminologies and descriptions. The present study's results on MDD trial prevalence align with Carhart-Harris and Goodwin, who, in a review outlining the therapeutic potential of psychedelics, accept that treatment-resistant depression is the most logical place to focus inquiry given the uncertainty in the treatment plan after SSRI failure [6]. The future should ideally focus on creating innovative therapies for patients with SSRI refractory disease. There are also non-psychiatric disorders that are currently being studied. Four studies used psychedelics to treat neurodegenerative disorders and eight studies evaluated treatment options for different forms of pain (chronic, post-operative, post-traumatic). Twelve studies were also found measuring psychedelic use for treating pain and headache disorders, while eight studies specifically evaluated psychedelic use for pain (chronic, postoperative, post-traumatic) and four studies evaluated treatment of headache disorders.

Interventions

The most common substances used in interventional studies were cannabis/cannabinoids. A large number of drugs (dronabinol, nabilone, nabiximols, THX-110) fell under this category as there are multiple synthetic cannabinoids currently under development or already brought to market. The fact that most studies use dronabinol is understandable seeing as it is already FDA-approved for appetite stimulation and as an antiemetic to combat chemo-induced nausea and vomiting, while nabilone is FDA-approved for nausea and vomiting refractory to conventional medical management [40-41]. With that in mind, current trials are studying broader uses of these drugs as treatments for chronic pain, Alzheimer’s, sleep apnea, and PTSD.

The next most researched drug is psilocybin, with 26 studies underway. This is the most popular drug of the “classical psychedelics” in clinical trials. This is due to the promising research that has already been performed with psilocybin and, historically, with a drug that has similar subjective effects, LSD (which is itself currently being researched in four different studies). Furthermore, there is an expert consensus that these two drugs cause less harm to society and individuals alike as compared to alcohol, tobacco, and other recreational drugs [42-45]. The success of previous studies is clear from the exciting FDA breakthrough therapy designation that it received in both 2018 and 2019, a promising pattern in the context of being a schedule I drug with "no currently accepted medical use" [46]. Current studies are focused on psychiatric issues such as depression, OCD, and alcohol-use disorder, but they are also studying potential uses in treating headaches and anorexia. The sheer number of studies is a promising sign that the preliminary success of prior studies is being taken seriously and being further advanced.

MDMA is the next most studied substance, with 14 studies ongoing. This reflects previous success in studies researching MDMA-assisted psychotherapy as a treatment for PTSD. The first controlled clinical trial of MDMA-assisted psychotherapy was published in 2011 [47] and produced promising results as 83% of the experimental group no longer met criteria for PTSD at 2- and 12-month follow-ups. There have subsequently been further promising studies in this area of research, and MDMA-assisted psychotherapy was even granted a breakthrough therapy designation from the FDA in 2017. It is important to continue to push for more robust clinical trials with high-quality randomized design and appropriate blinding. Additionally, researchers should aim for large enough sample sizes to ensure adequate power of detecting treatment effects that are not due to chance alone.

Primary Purpose and Phases

Although there has been a renewed and inspired interest in psychedelic therapies, the use of psychedelics overall is ultimately still in a nascent stage. This is reflected in the fact that only 53 out of 105 studies are studying the substances as treatments (rather than, for example, basic science research) and that 84/92 studies that are subject to classical study phases are in either phase 1 or phase 2 trials with only three trials in phase 3 and five in phase 4. Of the classical psychedelics (MDMA, LSD, psilocybin, ibogaine) there are only two current trials in phase 3 and they are both studying MDMA treatments for PTSD. This is also limited by financial constraints as both phase 3 and phase 4 clinical trials require more financial backing and are generally funded by industry. Potentially, when more studies progress, there will be an exponential increase in both the volume and speed of the research.

Geography

The United States of America has the most clinical trials out of any country, with 74 studies currently underway. This is despite strict government regulations regarding schedule 1 drugs and is a promising sign that regulations may loosen in the coming years.

The country with the most studies on a per-capital basis, however, is Switzerland, with 10. This may be reflective of the power of stigma and culture in facilitating research. Switzerland has a long history of being more accepting of psychedelic use, even legalizing LSD and MDMA therapies from 1988 to 1993 [48] and granting individual allowances for the therapeutic use of LSD and MDMA since 2014 [49]. It is no surprise that the country that celebrates “bicycle day” is also the country with the highest rate of research on the topic [50]. This holiday became commemorated after Albert Hofmann first synthesized and intentionally self-ingested LSD. Thus, he experienced the effects of the substance while also riding on a bicycle. This was one of the first well-known events where the hallucinogenic properties of LSD were identified, and thus Switzerland is now regarded largely as the birthplace of LSD.

It is also important to consider that several other clinical trial databases exist such as the European clinical trials registry at https://www.clinical trialsregister.eu. In addition, an Australian registry can be found at https://www.australianclinicaltrials.gov.au. This study only analyzed registered characteristics of each trial found on the clinicaltrials.gov website, which most likely created a bias toward being predominantly U.S. clinical trials compared to the other data from the other databases.

Types of Clinical Trials

When reviewing the clinical trial questions and their hypotheses over time, it appears that the questions asked by researchers have become more robust after each consecutive year. The few initial trials before 2010 mainly consisted of using psychedelics for the treatment of mood symptoms such as after cancer treatment (NCT00957359), during smoking cessation (NCT01943994), and for psychological therapy (NCT01404754). These studies had the primary goal of improving the mood of patients that underwent separate treatments for their medical diseases. Now recently, psychedelics are being used to actually treat many diseases as the sole drug of choice including many psychiatric diseases. Additionally, many studies have now also been added to achieve even basic scientific pursuits. Randomization with quadruple masking of the participant, care provider, investigator, and outcomes assessor appeared largely throughout all the years of clinical trials for psychedelics.

Current Challenges

While adverse psychotic reactions could theoretically be adverse events of psychedelic treatments, there has so far been an absence of any such reaction in recent studies [8,50,51]. Indeed, researchers now consider hallucinogens as one of the classes of drugs with the least amount of adverse side-effects [43,52-55]. Most countries have scheduled psychedelic drugs, increasing the standards of research design needed to approve and conduct research with them [40].However, there remain many factors that limit the potential application of psychedelics in a clinical setting. These barriers, compounded with a lack of acceptance from mainstream medicine and weariness from the general public, urge psychedelic researchers to adopt a measured approach if progress is to be achieved [56,57]. As a result, many current trials are small-scale, early phase studies to observe the safety and tolerability of this class of drugs [58]. Ultimately, if there is to be progress, it will likely be slow, which is not unwelcome by the psychedelic community. However, overcoming this image will not just depend upon sound research, as there are early data that suggest the therapeutic effects of psychedelics are correlated with the degree of the subjective opinion on the efficacy of the drugs. Thus, the progression of the field with research studies may potentially be hindered once again due to stigma. Ultimately, a proactive approach to performing rigorous research is needed for future innovation in the field. This could be potentially performed by obtaining a better basic science understanding of the drugs on a molecular level and educating the public. In addition, educating the public on the safety profile of these drugs is paramount.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. Only one United States sponsored database was searched. The opinions of the patients in these trials could also not be evaluated, and future studies should examine patient attitudes toward these particular drugs as treatment options for their medical disorders.

Conclusions

In the past two decades, there has been a recent uptrend in clinical trials of psychedelic drugs. Psychedelic therapies potentially hold much promise for the treatment of psychiatric disorders, but their current legal status and social stigmatization will likely continue to be a barrier to their progression to becoming a widely used treatment option for patients. However, the progress that has occurred over the years is encouraging and shows that the field is trending positively. More studies could be performed to evaluate the potential of psychedelics for symptomatic treatment during opioid tapering and depression refractory to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. Ultimately, a proactive approach to educating the scientific and general community alike is warranted.

Appendices

Table 4. Supplemental A. Total data of clinical trials in response to the query of clinicaltrials.gov.

CBD, cannabidiol; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; LSD, lysergic acid diethylamide; MDMA, methylenedioxymethamphetamine; OCD, obsessive compulsive disorder; PEA, palmitoylethanolamide; SSRI, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors; THC, tetrahydracannibidinol

| Clinical trials number | Title | Recruitment status | Condition or disease | Study type | Intervention | Primary purpose | Phase | Estimated enrollment | Study start date | Country | Sponsor |

| NCT03984214 | Efficacy and Safety of Dronabinol in the Improvement of Chemotherapy-induced and Tumor-related Symptoms in Advanced Pancreatic Cancer | Recruiting | Cancer | Interventional | Cannabis/cannabinoids – dronabinol | Treatment | 3 | 140 | 2019 | Austria | Austrian Group Medical Tumor Therapy |

| NCT04003948 | Preliminary Efficacy and Safety of Ibogaine in the Treatment of Methadone Detoxification | Not yet recruiting | Substance use disorder – opioids | Interventional | Ibogaine hydrochloride | Treatment | 2 | 20 | 2019 | Spain | Barcelona |

| NCT03756974 | BX-1 in Spasticity Due to Multiple Sclerosis | Recruiting | Degenerative diseases – multiple sclerosis | Interventional | Cannabis/cannabinoids – dronabinol | Treatment | 3 | 384 | 2019 | Germany | Bionorica SE |

| NCT03948074 | Cannabis For Cancer-Related Symptoms (CAFCARS) | Not yet recruiting | Cancer | Interventional | Cannabis/cannabinoids – THC, CBD | Treatment | 2 | 150 | 2019 | Canada | British Columbia Cancer Agency |

| NCT02983773 | Marijuana's Impact on Alcohol Motivation and Consumption | Recruiting | substance use disorder – alcohol | Interventional | Cannabis/cannabinoids – dronabinol | Basic science | 2 | 173 | 2017 | USA | Brown |

| NCT02492074 | Gene-Environment-Interaction: Influence of the COMT Genotype on the Effects of Different Cannabinoids - a PET Study | Not yet recruiting | Healthy | Interventional | Cannabis/cannabinoids – dronabinol, CBD | Basic science | 1 | 60 | 2020 | Germany | Central Institute of Mental Health, Mannheim |

| NCT03106363 | Combined Alcohol and Cannabis Effects on Skills of Young Drivers | Recruiting | Healthy | Interventional | Cannabis/cannabinoids – THC | Other | 1 | 70 | 2017 | Canada | Centre for Addiction and Mental Health |

| NCT03928015 | Evaluation of Dronabinol For Acute Pain Following Traumatic Injury | Not yet recruiting | Pain – post-traumatic pain | Interventional | Cannabis/cannabinoids – dronabinol | Supportive care | 2 | 216 | 2019 | USA | Centura Health |

| NCT04099355 | Investigating the Effect of Dronabinol on Post-surgical Pain | Recruiting | Pain – post-operative pain | Interventional | Cannabis/cannabinoids – dronabinol | Treatment | 1 | 80 | 2019 | USA | Columbia - New York Psychiatric Institute |

| NCT03775200 | The Safety and Efficacy of Psilocybin in Participants With Treatment Resistant Depression (P-TRD) | Recruiting | Depression | Interventional | Psilocybin | Treatment | 2 | 216 | 2019 | UK | COMPASS Pathways |

| NCT03766269 | Dronabinol Opioid Sparing Evaluation (DOSE) Trial | Recruiting | Pain – chronic pain | Interventional | Cannabis/cannabinoids – dronabinol | Treatment | 2 | 280 | 2018 | USA | Daisy Pharma Opioid Venture |

| NCT01964404 | Cannabis, Schizophrenia and Reward: Self-Medication and Agonist Treatment? | Recruiting | Psychosis/schizophrenia | Interventional | Cannabis/cannabinoids – dronabinol | Basic science | 1 | 240 | 2014 | USA | Dartmouth College |

| NCT04203498 | Safety and Effectiveness of Nabiximols Oromucosal Spray as Add-on Therapy in Participants With Spasticity Due to Multiple Sclerosis | Not yet recruiting | degenerative diseases – multiple sclerosis | Interventional | Cannabis/cannabinoids – nabiximols | Treatment | 3 | 446 | 2020 | USA | GW Pharmaceuticals, Inc. |

| NCT03087201 | CANNAbinoids in the Treatment of TICS (CANNA-TICS) (CANNA-TICS) | Recruiting | Multiple – Tourette syndrome, tic disorder | Interventional | Cannabis/cannabinoids – nabiximols | Treatment | 3 | 96 | 2018 | Germany | Hannover Medical School |

| NCT03380442 | Psilocybin and Depression (Psilo101) | Not yet recruiting | Depression | Interventional | Multiple – psilocybin, ketamine | Basic science | 2 | 60 | 2018 | Finland | Helsinki University |

| NCT03429075 | Psilocybin vs Escitalopram for Major Depressive Disorder: Comparative Mechanisms (Psilodep-RCT) | Recruiting | Depression | Interventional | Psilocybin | Treatment | 2 | 50 | 2019 | UK | Imperial College London |

| NCT04158778 | Bristol Imperial MDMA in Alcoholism Study (BIMA) | Active, not recruiting | Substance use disorder – alcohol | Interventional | MDMA | Treatment | 1 | 20 | 2018 | UK | Imperial College London |

| NCT02792257 | Trial of Dronabinol Adjunctive Treatment of Agitation in Alzheimer's Disease (AD) (THC-AD) | Recruiting | Degenerative diseases – Alzheimer's disease | Interventional | Cannabis/cannabinoids – dronabinol | Treatment | 2 | 160 | 2017 | USA | Johns Hopkins University |

| NCT02145091 | Effects of Psilocybin on Behavior, Psychology and Brain Function in Long-term Meditators | Active, not recruiting | Healthy | Interventional | Psilocybin | Basic science | 1 | 100 | 2014 | USA | Johns Hopkins University |

| NCT02243813 | Effects of Psilocybin-facilitated Experience on the Psychology and Effectiveness of Professional Leaders in Religion | Recruiting | Healthy | Interventional | Psilocybin | Basic science | 1 | 12 | 2015 | USA | Johns Hopkins University |

| NCT03609853 | Behavioral Pharmacology of THC and D-limonene | Recruiting | Healthy | Interventional | Cannabis/cannabinoids – THC, limonene (terpene) | Basic science | 1 | 20 | 2019 | USA | Johns Hopkins University |

| NCT03181529 | Effects of Psilocybin in Major Depressive Disorder | Active, not recruiting | Depression | Interventional | Psilocybin | Treatment | 2 | 24 | 2017 | USA | Johns Hopkins University |

| NCT04052568 | Effects of Psilocybin in Anorexia Nervosa | Recruiting | Anorexia nervosa | Interventional | Psilocybin | Treatment | 1 | 18 | 2019 | USA | Johns Hopkins University |

| NCT04123314 | Psilocybin for Depression in People With Mild Cognitive Impairment or Early Alzheimer's Disease | Recruiting | Multiple – depression, depressive symptoms, Alzheimers disease, mild cognitive impairment | Interventional | Psilocybin | Treatment | 1 | 20 | 2019 | USA | Johns Hopkins University |

| NCT04201197 | Interactions Between Cannabinoids and Cytochrome P450-Metabolized Drugs | Not yet recruiting | Healthy | Interventional | Cannabis/cannabinoids – inje cocktail, THC Cannabis extract, THC/CBD cannabis extract | Basic science | 1 | 25 | 2020 | USA | Johns Hopkins University |

| NCT04130633 | Behavioral Pharmacology of THC and Alpha-pinene | Not yet recruiting | Healthy | Interventional | Cannabis/cannabinoids – THC, alpha-pinene (terpene) | Basic science | 1 | 32 | 2020 | USA | Johns Hopkins University |

| NCT01943994 | Psilocybin-facilitated Smoking Cessation Treatment: A Pilot Study | Recruiting | Substance use disorder – nicotine | Interventional | Psilocybin | Treatment | NA | 95 | 2008 | USA | Johns Hopkins University |

| NCT03418714 | Effects of Salvinorin A on Brain Function | Active, not recruiting | Healthy | Interventional | Salvinorin A | Other | 1 and 2 | 20 | 2017 | USA | Johns Hopkins University |

| NCT03555968 | Effects of THC and Alcohol on Driving Performance | Not yet recruiting | Healthy | Interventional | Cannabis/cannabinoids – THC | Basic science | 4 | 135 | 2020 | Canada | Lakehead University |

| NCT03655717 | Using Imaging to Assess Effects of THC on Brain Activity (fNIRS) | Recruiting | Substance use disorder – marijuana/cannabis | Interventional | Multiple – dronabinol, ethanol | Diagnostic | 4 | 50 | 2018 | USA | Massachusetts General Hospital |

| NCT03550352 | Cannabinoids in PLWHIV on Effective ART | Not yet recruiting | HIV | Interventional | Cannabis/cannabinoids – THC, CBD | Treatment | 2 | 26 | 2018 | Canada | McGill University |

| NCT03773796 | Nabilone for Non-motor Symptoms in Parkinson's Disease (NMS-Nab2) | Recruiting | Degenerative diseases – Parkinson's disease | Interventional | Cannabis/cannabinoids – nabilone | Treatment | 3 | 48 | 2018 | Austria | Medical University of Innsbruck |

| NCT04155008 | Nutrition and Pharmacological Algorithm for Oncology Patients Study | Not yet recruiting | Cancer | Interventional | Cannabis/cannabinoids – dronabinol | Supportive care | 4 | 30 | 2019 | USA | Montefiore Medical Center |

| NCT03422861 | Nabilone Use For Acute Pain in Inflammatory Bowel Disease Patients | Not yet recruiting | Pain – inflammatory bowel disease | Interventional | Cannabis/cannabinoids – nabilone | Supportive care | NA | 80 | 2019 | USA | Mount Sinai Health System |

| NCT01404754 | Psychological Effects of Methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA) When Administered to Healthy Volunteers (MT-1) | Enrolling by invitation | Healthy | Interventional | MDMA | Basic science | 1 | 100 | 2011 | USA | Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies (MAPS) |

| NCT03181763 | Evaluation of MDMA on Startle Response | Recruiting | Healthy | Interventional | MDMA | Basic science | 1 | 30 | 2017 | USA | Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies (MAPS) |

| NCT04077437 | A Multi-Site Phase 3 Study of MDMA-Assisted Psychotherapy for PTSD II | Not yet recruiting | PTSD | Interventional | MDMA | Treatment | 3 | 100 | 2020 | USA | Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies (MAPS) |

| NCT03537014 | A Multi-Site Phase 3 Study of MDMA-Assisted Psychotherapy for PTSD (MAPP1) | Recruiting | PTSD | Interventional | MDMA | Treatment | 3 | 100 | 2018 | USA | Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies (MAPS) |

| NCT03485287 | Study of Safety and Effects of MDMA-assisted Psychotherapy for Treatment of PTSD | Active, not recruiting | PTSD | Interventional | MDMA | Treatment | 2 | 5 | 2018 | USA | Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies (MAPS) |

| NCT03282123 | Open Label Multi-Site Study of Safety and Effects of MDMA-assisted Psychotherapy for Treatment of PTSD | Active, not recruiting | PTSD | Interventional | MDMA | Treatment | 2 | 38 | 2017 | USA | Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies (MAPS) |

| NCT04073433 | Psychological Effects of Methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA) When Administered to Healthy Volunteers (MT-2) | Not yet recruiting | Healthy | Interventional | MDMA | Basic science | 1 | 150 | 2020 | USA | Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies (MAPS) |

| NCT03606538 | MDMA in Subjects With Moderate Hepatic Impairment and Subjects With Normal Hepatic Function | Not yet recruiting | Hepatic impairment | Interventional | MDMA | Basic science | 1 | 16 | 2020 | USA | Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies (MAPS) |

| NCT04030169 | Open Label Multi-Site Study of Safety and Effects of MDMA-assisted Psychotherapy for Treatment of PTSD With Optional fMRI Sub-Study | Not yet recruiting | PTSD | Interventional | MDMA | Treatment | 2 | 40 | 2019 | Netherlands | Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies (MAPS) - Europe |

| NCT00957359 | Psilocybin Cancer Anxiety Study | Active, not recruiting | Cancer | Interventional | Psilocybin | Treatment | 1 | 29 | 2009 | USA | New York University |

| NCT02421263 | The Effects of Psilocybin-Facilitated Experience on the Psychology and Effectiveness of Religious Professionals | Recruiting | Healthy | Interventional | Psilocybin | Health services research | 1 | 12 | 2015 | USA | New York University |

| NCT02061293 | A Double-Blind Trial of Psilocybin-Assisted Treatment of Alcohol Dependence | Recruiting | Substance use disorder – alcohol | Interventional | Psilocybin | Treatment | 2 | 180 | 2014 | USA | New York University |

| NCT03560934 | Tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) and Sleep | Recruiting | Healthy | Interventional | Cannabis/cannabinoids – dronabinol | Basic science | 1 | 14 | 2018 | USA | Oregon Health and Science University |

| NCT03289949 | The Neurobiological Effect of 5-HT2AR Modulation | Recruiting | Healthy | Interventional | Psilocybin | Basic science | 1 | 45 | 2019 | Denmark | Rigshospitalet |

| NCT03337503 | Safety and Efficacy of Medical Cannabis Oil in the Treatment of Patients With Chronic Pain | Recruiting | Pain – chronic pain | Interventional | Cannabis/cannabinoids – THC, CBD | Treatment | 4 | 160 | 2018 | Canada | Sante Cannabis |

| NCT04060108 | Stanford Reward Circuits of the Brain Study - MDMA (RBRAIN-MDMA) | Not yet recruiting | Healthy | Observational | MDMA | NA | NA | 40 | 2020 | USA | Stanford University |

| NCT03646552 | A Study to Examine the Efficacy of a Therapeutic THX-110 for Obstructive Sleep Apnea | Recruiting | Obstructive sleep apnea | Interventional | Cannabis/cannabinoids – THX-110 (dronabinol + PEA) | Treatment | 2 | 30 | 2018 | Israel | Therapix Biosciences Ltd. |

| NCT03651726 | A Study to Examine the Efficacy of a Therapeutic THX-110 for Tourette Syndrome | Not yet recruiting | Tourette syndrome | Interventional | Cannabis/Cannabinoids – THX-110 (Dronabinol + PEA) | Treatment | 2 | 60 | 2018 | Israel | Therapix Biosciences Ltd. |

| NCT02037126 | Psilocybin-facilitated Treatment for Cocaine Use | Recruiting | Substance use disorder – cocaine | Interventional | Psilocybin | Treatment | 2 | 40 | 2015 | USA | University of Alabama |

| NCT03153579 | LSD Treatment in Persons Suffering From Anxiety Symptoms in Severe Somatic Diseases or in Psychiatric Anxiety Disorders (LSD-assist) | Recruiting | Anxiety disorders | Interventional | LSD | Treatment | 2 | 40 | 2017 | Switzerland | University Hospital, Basel |

| NCT03866252 | LSD Therapy for Persons Suffering From Major Depression (LAD) | Recruiting | Depression | Interventional | LSD | Treatment | 2 | 60 | 2019 | Switzerland | University Hospital, Basel |

| NCT03781128 | Lysergic Acid Diethylamide (LSD) as Treatment for Cluster Headache (LCH) | Recruiting | Headache disorders – cluster headache | Interventional | LSD | Treatment | 2 | 30 | 2019 | Switzerland | University Hospital, Basel |

| NCT03527316 | Effect of Methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA) (Serotonin Release) on Fear Extinction (MFE) | Recruiting | Healthy | Interventional | MDMA | Basic science | 1 | 30 | 2019 | Switzerland | University Hospital, Basel |

| NCT03604744 | Direct Comparison of Altered States of Consciousness Induced by LSD and Psilocybin (LSD-psilo) | Recruiting | Healthy | Interventional | Multiple – psilocybin, LSD | Basic science | 1 | 30 | 2019 | Switzerland | University Hospital, Basel |

| NCT03912974 | Effects of SERT Inhibition on the Subjective Response to Psilocybin in Healthy Subjects | Recruiting | Healthy | Interventional | Multiple – SSRI (escitalopram), Psilocybin | Basic science | 1 | 24 | 2019 | Switzerland | University Hospital, Basel |

| NCT03661892 | Pilot, Syndros, Decreasing Use of Opioids in Breast Cancer Subjects With Bone Mets | Recruiting | Cancer | Interventional | Cannabis/cannabinoids – dronabinol | Treatment | 1 | 20 | 2018 | USA | University of Arizona |

| NCT03300947 | Psilocybin for Treatment of Obsessive Compulsive Disorder (PSILOCD) | Recruiting | OCD | Interventional | Psilocybin | Treatment | 1 | 15 | 2019 | USA | University of Arizona |

| NCT02460692 | Trial of Dronabinol and Vaporized Cannabis in Neuropathic Low Back Pain | Recruiting | Pain – neuropathic low-back pain | Interventional | Cannabis/cannabinoids – dronabinol, cannabis | Treatment | 2 | 120 | 2016 | USA | University of California, San Diego |

| NCT02950467 | Psilocybin-assisted Group Therapy for Demoralization in Long-term AIDS Survivors | Active, not recruiting | Multiple – distress/grief, depression | Interventional | Psilocybin | Treatment | 1 | 36 | 2018 | USA | University of California, San Francisco |

| NCT03790618 | Effect of Stimulant Drugs on Social Perception (ESP) | Recruiting | Healthy | Interventional | Multiple – MDMA, methamphetamine | Basic science | 1 | 40 | 2016 | USA | University of Chicago |

| NCT03530800 | Dronabinol in Trichotillomania and Other Body Focused Repetitive Behaviors | Recruiting | Trichotillomania | Interventional | Cannabis/cannabinoids – dronabinol | Treatment | 2 | 50 | 2018 | USA | University of Chicago |

| NCT03809546 | Individual Differences in Drug Response (IDT) | Recruiting | Healthy | Interventional | Cannabis/cannabinoids – dronabinol | Basic science | 1 | 60 | 2018 | USA | University of Chicago |

| NCT03790358 | Mood Effects of Serotonin Agonists | Recruiting | Healthy | Interventional | LSD | Basic science | 1 | 40 | 2018 | USA | University of Chicago |

| NCT04053036 | Effects of Drugs on Responses to Brain and Emotional Processes (MAT) | Recruiting | Autism spectrum disorder | Interventional | MDMA | Basic science | 1 | 45 | 2019 | USA | University of Chicago |

| NCT03944954 | Neural Mechanisms of Cannabinoid-impaired Decision-Making in Emerging Adults | Recruiting | Substance use disorder – marijuana/cannabis | Interventional | Cannabis/cannabinoids – dronabinol | Basic science | 1 | 40 | 2017 | USA | University of Kentucky |

| NCT03380728 | Ibogaine in the Treatment of Alcoholism: a Randomized, Double-blind, Placebo-controlled, Escalating-dose, Phase 2 Trial | Not yet recruiting | Substance use disorder – alcohol | Interventional | Ibogaine hydrochloride | Treatment | 2 | 12 | 2020 | Brazil | University of Sao Paulo |

| NCT03744091 | Evaluation of the Pharmacokinetics of Prana P1 Capsules | Active, not recruiting | Healthy | Interventional | Cannabis/cannabinoids – THC | Treatment | 1 | 13 | 2018 | West Indies | University of the West Indies |

| NCT03215940 | Treatment of Chronic Pain With Cannabidiol (CBD) and Delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) | Recruiting | Pain – chronic pain | Interventional | Cannabis/cannabinoids – dronabinol, CBD | Treatment | 1 | 75 | 2018 | USA | University of Utah |

| NCT04161066 | Adjunctive Effects of Psilocybin and Buprenorphine | Not yet recruiting | Substance use disorder – opioids | Interventional | Psilocybin | Health services research | 1 | 10 | 2020 | USA | University of Wisconsin |

| NCT03715127 | Clinical, Neurocognitive, and Emotional Effects of Psilocybin in Depressed Patients - Proof of Concept | Recruiting | Depression | Interventional | Psilocybin | Treatment | 2 | 60 | 2019 | Switzerland | University of Zurich |

| NCT03736980 | Beyond the Self and Back: Neuropharmacological Mechanisms Underlying the Dissolution of the Self | Active, not recruiting | Healthy | Interventional | Psilocybin | Basic science | NA | 140 | 2018 | Switzerland | University of Zurich |

| NCT03853577 | Characterization of Altered Waking States of Consciousness in Healthy Humans | Recruiting | Healthy | Interventional | Psilocybin | Basic science | NA | 25 | 2019 | Switzerland | University of Zurich |

| NCT04141501 | Clinical and Mechanistic Effects of Psilocybin in Alcohol Addicted Patients | Not yet recruiting | Substance use disorder – alcohol | Interventional | Psilocybin | Treatment | 2 | 60 | 2020 | Switzerland | University of Zurich |

| NCT03866174 | A Study of Psilocybin for Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) | Recruiting | Depression | Interventional | Psilocybin | Treatment | 2 | 80 | 2019 | USA | Usona Institute |

| NCT03008005 | Effects of Delta-9 Tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) on Retention of Memory for Fear Extinction Learning in PTSD: R61 Study | Recruiting | PTSD | Interventional | Cannabis/cannabinoids – dronabinol | Basic science | 4 | 104 | 2017 | USA | Wayne State University |

| NCT02069366 | Cannabinoid Control of Fear Extinction Neural Circuits in Post-traumatic Stress Disorder | Active, not recruiting | PTSD | Interventional | Cannabis/cannabinoids – dronabinol | Basic science | NA | 130 | 2014 | USA | Wayne State University |

| NCT04080427 | Effects of Delta9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) on Retention of Memory for Fear Extinction Learning in PTSD: R33 Study | Not yet recruiting | PTSD | Interventional | Cannabis/cannabinoids – dronabinol | Basic science | 1 | 100 | 2020 | USA | Wayne State University |

| NCT04040582 | Psychedelics and Wellness Study (PAWS) | Recruiting | Multiple – depression, anxiety, PTSD | Observational | Multiple – All psychedelics | Treatment | NA | 5000 | 2019 | USA | Wild 5 Wellness |

| NCT00678730 | Pharmacogenetics of Cannabinoid Response | Active, not recruiting | Healthy | Interventional | Cannabis/cannabinoids – THC | Basic science | 1 | 162 | 2007 | USA | Yale University |

| NCT00982982 | Effects of Delta-9-THC and Iomazenil in Healthy Humans | Active, not recruiting | Psychosis/schizophrenia | Interventional | Cannabis/cannabinoids – THC | Basic science | 1 | 60 | 2009 | USA | Yale University |

| NCT00700596 | Effects of Salvinorin A in Healthy Controls | Active, not recruiting | Healthy | Interventional | Salvinorin A | Basic science | 1 | 41 | 2009 | USA | Yale University |

| NCT01180374 | The Effects of Cannabidiol and ∆-9-THC in Humans | Active, not recruiting | Healthy | Interventional | Cannabis/cannabinoids – dronabinol, CBD | Basic science | 1 | 75 | 2010 | USA | Yale University |

| NCT01591629 | The Effects of ∆-9-THC and Naloxone in Humans | Active, not recruiting | Healthy | Interventional | Cannabis/cannabinoids – THC | Basic science | 1 | 56 | 2011 | USA | Yale University |

| NCT02335060 | N-acetylcysteine Effects on Tetrahydrocannabinol | Active, not recruiting | Healthy | Interventional | Cannabis/cannabinoids – THC | Basic science | 1 | 36 | 2014 | USA | Yale University |

| NCT02781519 | Gender Related Differences in the Acute Effects of Delta-9-Tetrahydrocannabinol in Healthy Humans (THC-Gender) | Recruiting | Healthy | Interventional | Cannabis/cannabinoids – THC | Basic science | 1 | 100 | 2015 | USA | Yale University |

| NCT02811939 | Testing the Interactive Effects of Delta-9-Tetrahydrocannabinol and Pregnenolone: Sub-Study I (THC-PREG-I) | Recruiting | Healthy | Interventional | Cannabis/cannabinoids – dronabinol | Basic science | 1 | 19 | 2016 | USA | Yale University |

| NCT02811510 | Gender Related Differences in the Acute Effects of Delta-9-Tetrahydrocannabinol in Healthy Humans: Sub-Study I (THC-Gender-I) | Recruiting | Healthy | Interventional | Cannabis/cannabinoids – dronabinol | Basic science | 1 | 40 | 2016 | USA | Yale University |

| NCT02981173 | Psilocybin for the Treatment of Cluster Headache | Recruiting | Headache disorders – cluster headache | Interventional | Psilocybin | Treatment | 1 | 24 | 2016 | USA | Yale University |

| NCT03206463 | Cognitive and Psychophysiological Effects of Delta-9-Tetrahydrocannabinol in Bipolar Disorder (THC-BD) | Active, not recruiting | Bipolar disorder | Interventional | Cannabis/cannabinoids – THC | Treatment | 1 | 40 | 2017 | USA | Yale University |

| NCT03191084 | Examine the Feasibility of a Standardized Field Test for Marijuana Impairment: Laboratory Evaluations | Recruiting | Substance use disorder – marijuana/cannabis | Interventional | Cannabis/cannabinoids – THC | Other | 1 | 28 | 2017 | USA | Yale University |

| NCT03341689 | Psilocybin for the Treatment of Migraine Headache | Recruiting | Headache disorders – migraine | Interventional | Psilocybin | Treatment | 1 | 24 | 2017 | USA | Yale University |

| NCT02102113 | Probing the Cannabinoid System in Individuals With a Family History of Psychosis | Active, not recruiting | Psychosis/schizophrenia | Interventional | Cannabis/cannabinoids – THC | Other | NA | 21 | 2014 | USA | Yale University |

| NCT02757313 | Neuroscience of Marijuana Impaired Driving (MJDriving) | Recruiting | Substance use disorder – marijuana/cannabis | Interventional | Cannabis/cannabinoids – THC | Other | NA | 96 | 2016 | USA | Yale University |

| NCT03554174 | Psilocybin - Induced Neuroplasticity in the Treatment of Major Depressive Disorder | Recruiting | Depression | Interventional | Psilocybin | Treatment | 1 | 18 | 2018 | USA | Yale University |

| NCT03356483 | Efficacy of Psilocybin in OCD: a Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Study | Recruiting | OCD | Interventional | Psilocybin | Treatment | 1 | 30 | 2018 | USA | Yale University |

| NCT03978156 | Dronabinol for Pain and Inflammation in Adults Living With Sickle Cell Disease | Recruiting | Pain – sickle cell disease | Interventional | Cannabis/cannabinoids – dronabinol | Treatment | 1 | 30 | 2019 | USA | Yale University |

| NCT04025359 | Effects of Dronabinol in Opioid Maintained Patients (THC) | Recruiting | Substance use disorder – opioids | Interventional | Cannabis/cannabinoids – dronabinol | Treatment | 1 | 20 | 2019 | USA | Yale University |

| NCT03752918 | The Effects of MDMA on Prefrontal and Amygdala Activation in PTSD | Recruiting | PTSD | Interventional | MDMA | Treatment | 1 | 20 | 2019 | USA | Yale University |

| NCT04199468 | THC and Ketamine Effects in Humans: Relation to Neural Oscillations and Psychosis | Recruiting | Healthy | Interventional | Multiple – THC, ketamine | Basic science | 1 | 21 | 2019 | USA | Yale University |

| NCT03806985 | Effects of Psilocybin in Post-Traumatic Headache | Recruiting | Headache disorders – post-traumatic headache | Interventional | Psilocybin | Treatment | 1 | 24 | 2019 | USA | Yale University |

| NCT02710331 | Ethanol and Cannabinoid Effects on Simulated Driving and Related Cognition: Substudy III (THC-ETOH-III) | Recruiting | Healthy | Interventional | Cannabis/cannabinoids – dronabinol | Basic science | 1 | 40 | 2020 | USA | Yale University |

The content published in Cureus is the result of clinical experience and/or research by independent individuals or organizations. Cureus is not responsible for the scientific accuracy or reliability of data or conclusions published herein. All content published within Cureus is intended only for educational, research and reference purposes. Additionally, articles published within Cureus should not be deemed a suitable substitute for the advice of a qualified health care professional. Do not disregard or avoid professional medical advice due to content published within Cureus.

Footnotes

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

References

- 1.Administration Administration, F. a. D. (2016. U.S. FDA. Cesamet™. [ Jul; 2022 ]. 2016. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2006/018677s011lbl.pdf https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2006/018677s011lbl.pdf

- 2.Buranyi Buranyi, S. (2015, November 26, 2015 2015. Switzerland Briefly Legalized LSD Therapy and Then Couldn't Let It Go. [ Jul; 2022 ]. 2015. https://www.vice.com/en/article/aekz8g/switzerland-briefly-legalized-lsd-therapy-and-then-couldnt-let-it-go https://www.vice.com/en/article/aekz8g/switzerland-briefly-legalized-lsd-therapy-and-then-couldnt-let-it-go

- 3.A non-hallucinogenic psychedelic analogue with therapeutic potential. Cameron LP, Tombari RJ, Lu J, et al. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-020-3008-z. Nature. 2021;589:474–479. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-3008-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Psilocybin with psychological support for treatment-resistant depression: an open-label feasibility study. Carhart-Harris RL, Bolstridge M, Rucker J, et al. Lancet Psychiatry. 2016;3:619–627. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(16)30065-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Neural correlates of the psychedelic state as determined by fMRI studies with psilocybin. Carhart-Harris RL, Erritzoe D, Williams T, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:2138–2143. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1119598109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.The therapeutic potential of psychedelic drugs: past, present, and future. Carhart-Harris RL, Goodwin GM. https://doi.org/10.1038/npp.2017.84. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2017;42:2105–2113. doi: 10.1038/npp.2017.84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.The paradoxical psychological effects of lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD) Carhart-Harris RL, Kaelen M, Bolstridge M, et al. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0033291715002901. Psychol Med. 2016;46:1379–1390. doi: 10.1017/S0033291715002901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.LSD enhances suggestibility in healthy volunteers. Carhart-Harris RL, Kaelen M, Whalley MG, Bolstridge M, Feilding A, Nutt DJ. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2015;232:785–794. doi: 10.1007/s00213-014-3714-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Neural correlates of the LSD experience revealed by multimodal neuroimaging. Carhart-Harris RL, Muthukumaraswamy S, Roseman L, et al. http://10.1073/pnas.1518377113. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016;113:4853–4858. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1518377113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Psilocybin links binocular rivalry switch rate to attention and subjective arousal levels in humans. Carter OL, Hasler F, Pettigrew JD, Wallis GM, Liu GB, Vollenweider FX. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2007;195:415–424. doi: 10.1007/s00213-007-0930-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.A review of emerging therapeutic potential of psychedelic drugs in the treatment of psychiatric illnesses. Chi T, Gold JA. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jns.2020.116715. J Neurol Sci. 2020;411:116715. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2020.116715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Neuronal correlates of visual and auditory alertness in the DMT and ketamine model of psychosis. Daumann J, Wagner D, Heekeren K, Neukirch A, Thiel CM, Gouzoulis-Mayfrank E. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269881109103227. J Psychopharmacol. 2010;24:1515–1524. doi: 10.1177/0269881109103227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ayahuasca, dimethyltryptamine, and psychosis: a systematic review of human studies. Dos Santos RG, Bouso JC, Hallak JE. https://doi.org/10.1177/2045125316689030. Ther Adv Psychopharmacol. 2017;7:141–157. doi: 10.1177/2045125316689030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Prehistoric peyote use: alkaloid analysis and radiocarbon dating of archaeological specimens of Lophophora from Texas. El-Seedi HR, De Smet PA, Beck O, Possnert G, Bruhn JG. J Ethnopharmacol. 2005;101:238–242. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2005.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Clinical applications of hallucinogens: a review. Garcia-Romeu A, Kersgaard B, Addy PH. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2016;24:229–268. doi: 10.1037/pha0000084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gasser Gasser, P. (2017. Research Update: Psychedelic Group Therapy in Switzerland. [ Jul; 2022 ]. 2017. https://maps.org/news/bulletin/research-update-psychedelic-group-therapy-in-switzerland/ https://maps.org/news/bulletin/research-update-psychedelic-group-therapy-in-switzerland/

- 17.Psychological effects of (S)-ketamine and N,N-dimethyltryptamine (DMT): a double-blind, cross-over study in healthy volunteers. Gouzoulis-Mayfrank E, Heekeren K, Neukirch A, Stoll M, Stock C, Obradovic M, Kovar KA. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2005;38:301–311. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-916185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Psilocybin produces substantial and sustained decreases in depression and anxiety in patients with life-threatening cancer: A randomized double-blind trial. Griffiths RR, Johnson MW, Carducci MA, et al. J Psychopharmacol. 2016;30:1181–1197. doi: 10.1177/0269881116675513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Psilocybin can occasion mystical-type experiences having substantial and sustained personal meaning and spiritual significance. Griffiths RR, Richards WA, McCann U, Jesse R. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2006;187:268–283. doi: 10.1007/s00213-006-0457-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grinspoon L, Bakalar JB. Psychedelic Drugs Reconsidered. Basic Books. New York: Basic Books; 1979. Psychedelic Drugs Reconsidered. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Grob C. Yearbook for Ethnomedicine and the Study of Consciousness. Berlin: Verlag fur Wissenschaft und Bildung; 1994. Psychiatric research with hallucinogens: What have we learned? . [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grof S. Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies; 2001. LSD Psychotherapy. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Basel in the spolight: the city that learned to love LSD. [ Jul; 2022 ];Hardach Hardach, S. S. https://www.theguardian.com/cities/2018/apr/19/basel-in-the-spotlight-the-city-that-learned-to-love-lsd-albert-hofmann Guardian. 2018 12 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Berichte der deutschen chemischen Gesellschaft. Heffter A. Ueber Cateenalkaloïde. 1896;29:216–227. [Google Scholar]

- 25.[Psilocybin, a psychotropic substance from the Mexican mushroom Psilicybe mexicana Heim] [Article in German] Hofmann A, Heim R, Brack A, Kobel H. Experientia. 1958;14:107–109. doi: 10.1007/BF02159243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.The anti-addiction drug ibogaine and the heart: a delicate relation. Koenig X, Hilber K. Molecules. 2015;20:2208–2228. doi: 10.3390/molecules20022208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Psilocybin biases facial recognition, goal-directed behavior, and mood state toward positive relative to negative emotions through different serotonergic subreceptors. Kometer M, Schmidt A, Bachmann R, Studerus E, Seifritz E, Vollenweider FX. Biol Psychiatry. 2012;72:898–906. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2012.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Back to the future: research renewed on the clinical utility of psychedelic drugs. Lieberman JA, Shalev D. J Psychopharmacol. 2016;30:1198–1200. doi: 10.1177/0269881116675755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ludwig AM. Hallucinogenic Drug Research: Impact on Science and Society. Beloit, WI: Stash Press; 1970. LSD treatment in alcoholism. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mystical experiences occasioned by the hallucinogen psilocybin lead to increases in the personality domain of openness. MacLean KA, Johnson MW, Griffiths RR. J Psychopharmacol. 2011;25:1453–1461. doi: 10.1177/0269881111420188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Acute adverse reactions to LSD in clinical and experimental use in the United Kingdom. Malleson N. Br J Psychiatry. 1971;118:229–230. doi: 10.1192/bjp.118.543.229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA)-assisted psychotherapy for post-traumatic stress disorder in military veterans, firefighters, and police officers: a randomised, double-blind, dose-response, phase 2 clinical trial. Mithoefer MC, Mithoefer AT, Feduccia AA, et al. Lancet Psychiatry. 2018;5:486–497. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(18)30135-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.The safety and efficacy of {+/-}3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine-assisted psychotherapy in subjects with chronic, treatment-resistant posttraumatic stress disorder: the first randomized controlled pilot study. Mithoefer MC, Wagner MT, Mithoefer AT, Jerome L, Doblin R. J Psychopharmacol. 2011;25:439–452. doi: 10.1177/0269881110378371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Broadband cortical desynchronization underlies the human psychedelic state. Muthukumaraswamy SD, Carhart-Harris RL, Moran RJ, et al. J Neurosci. 2013;33:15171–15183. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2063-13.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.National Academies of Sciences, Engineering Engineering, and Medicine. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2017. The Health Effects of Cannabis and Cannabinoids: The Current State of Evidence and Recommendations for Research. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Development of a rational scale to assess the harm of drugs of potential misuse. Nutt D, King LA, Saulsbury W, Blakemore C. Lancet. 2007;369:1047–1053. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60464-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Effects of Schedule I drug laws on neuroscience research and treatment innovation. Nutt DJ, King LA, Nichols DE. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2013;14:577–585. doi: 10.1038/nrn3530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Drug harms in the UK: a multicriteria decision analysis. Nutt DJ, King LA, Phillips LD. Lancet. 2010;376:1558–1565. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61462-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Efficacy and enlightenment: LSD psychotherapy and the Drug Amendments of 1962. Oram M. J Hist Med Allied Sci. 2014;69:221–250. doi: 10.1093/jhmas/jrs050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Overdose Death Rates. [ Jul; 2022 ]. 2021. https://www.drugabuse.gov/drug-topics/trends-statistics/overdose-death-rates https://www.drugabuse.gov/drug-topics/trends-statistics/overdose-death-rates

- 41.The psychedelic state induced by ayahuasca modulates the activity and connectivity of the default mode network. Palhano-Fontes F, Andrade KC, Tofoli LF, et al. PLoS One. 2015;10:0. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0118143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.The fabric of meaning and subjective effects in LSD-induced states depend on serotonin 2A receptor activation. Preller KH, Herdener M, Pokorny T, et al. Curr Biol. 2017;27:451–457. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2016.12.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Effects of the South American psychoactive beverage ayahuasca on regional brain electrical activity in humans: a functional neuroimaging study using low-resolution electromagnetic tomography. Riba J, Anderer P, Jané F, Saletu B, Barbanoj MJ. Neuropsychobiology. 2004;50:89–101. doi: 10.1159/000077946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Increased frontal and paralimbic activation following ayahuasca, the pan-Amazonian inebriant. Riba J, Romero S, Grasa E, Mena E, Carrió I, Barbanoj MJ. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2006;186:93–98. doi: 10.1007/s00213-006-0358-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Acute effects of lysergic acid diethylamide in healthy subjects. Schmid Y, Enzler F, Gasser P, et al. Biol Psychiatry. 2015;78:544–553. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2014.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schultes E, Hofmann A, Ratsch C. Healing Arts Press. Rochester, VT: Healing Arts Press; 1998. Plants of the Gods: Their Sacred, Healing, and Hallucinogenic Powers. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Improving the use of research evidence in guideline development: 1. Guidelines for guidelines. Schünemann HJ, Fretheim A, Oxman AD. Health Res Policy Syst. 2006;4:13. doi: 10.1186/1478-4505-4-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Can psychedelics have a role in psychiatry once again? Sessa B. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.186.6.457. Br J Psychiatry. 2005;186:457–458. doi: 10.1192/bjp.186.6.457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Are psychedelic drug treatments seeing a comeback in psychiatry? St John Sessa B. Prog Neurol Psychiatry. 2008;12:5–10. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Quantifying the RR of harm to self and others from substance misuse: results from a survey of clinical experts across Scotland. Taylor M, Mackay K, Murphy J, McIntosh A, McIntosh C, Anderson S, Welch K. BMJ Open. 2012;2:0. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2011-000774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Inhibition of alpha oscillations through serotonin-2A receptor activation underlies the visual effects of ayahuasca in humans. Valle M, Maqueda AE, Rabella M, et al. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2016;26:1161–1175. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2016.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.European rating of drug harms. van Amsterdam J, Nutt D, Phillips L, van den Brink W. J Psychopharmacol. 2015;29:655–660. doi: 10.1177/0269881115581980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ranking the harm of alcohol, tobacco and illicit drugs for the individual and the population. van Amsterdam J, Opperhuizen A, Koeter M, van den Brink W. Eur Addict Res. 2010;16:202–207. doi: 10.1159/000317249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Harm potential of magic mushroom use: a review. van Amsterdam J, Opperhuizen A, van den Brink W. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol. 2011;59:423–429. doi: 10.1016/j.yrtph.2011.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Physical harm due to chronic substance use. van Amsterdam J, Pennings E, Brunt T, van den Brink W. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol. 2013;66:83–87. doi: 10.1016/j.yrtph.2013.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Positron emission tomography and fluorodeoxyglucose studies of metabolic hyperfrontality and psychopathology in the psilocybin model of psychosis. Vollenweider FX, Leenders KL, Scharfetter C, Maguire P, Stadelmann O, Angst J. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1997;16:357–372. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(96)00246-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Psilocybin induces schizophrenia-like psychosis in humans via a serotonin-2 agonist action. Vollenweider FX, Vollenweider-Scherpenhuyzen MF, Bäbler A, Vogel H, Hell D. Neuroreport. 1998;9:3897–3902. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199812010-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Drug and opioid-involved overdose deaths - United States, 2017-2018. Wilson N, Kariisa M, Seth P, Smith H 4th, Davis NL. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:290–297. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6911a4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]