Abstract

Terpenes possess a wide range of medicinal properties and are potential therapeutics for a variety of pathological conditions. This study investigated the acute effects of two cannabis terpenes, β-caryophyllene and α-pinene, on zebrafish locomotion, anxiety-like, and boldness behaviour using the open field exploration and novel object approach tests. β-caryophyllene was administered in 0.02%, 0.2%, 2.0%, and 4% doses. α-pinene was administered in 0.01%, 0.02%, and 0.1% doses. As α-pinene is a racemic compound, we also tested its (+) and (−) enantiomers to observe any differential effects. β-caryophyllene had only a sedative effect at the highest dose tested. α-pinene had differing dose-dependent effects on anxiety-like and motor variables. Specifically, (+)-α-pinene and (−)-α-pinene had significant effects on anxiety measures, time spent in the thigmotaxis (outer) or center zone, in the open field test, as well as locomotor variables, swimming velocity and immobility. (+ /−)-α-pinene showed only a small effect on the open field test on immobility at the 0.1% dose. This study demonstrates that α-pinene can have a sedative or anxiolytic effect in zebrafish and may have different medicinal properties when isolated into its (+) or (−) enantiomers.

Subject terms: Drug discovery, Neuroscience, Psychology

Introduction

Cannabis terpenes found in the Cannabis sativa plant have emerged as candidate therapeutic compounds1 following the potential health benefits of the phytocannabinoids ∆9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) and cannabidiol (CBD)2. Terpenes, a major class of phytochemicals, form the essential oils of plants and flowers and are responsible for their varying aromas, flavours, and colours1,3–6. In the cannabis plant, terpenes are found in the glandular trichomes of the inflorescence of the female plant, the same glands that secrete the common phytocannabinoids, THC and CBD3,5, and vary within and across the many different strains4,5,7,8. There are over fifty cannabis terpenes most commonly found in North American cannabis strains, eight of which predominate to form a “Terpene Super Class”: myrcene, terpinolene, ocimene, limonene, ⍺-pinene, humulene, linalool, and β-caryophyllene9.

Terpenes are hydrocarbon compounds that consist of varying numbers of isoprene molecules and are classified according to the number of pairs of isoprenes they are made up of10. The most prevalent types of terpenes in cannabis consist of either 2 isoprene molecules (monoterpenes) or 3 isoprene molecules (sesquiterpenes), and less commonly, 4 isoprene molecules (diterpenes)10. Monoterpenes are highly volatile and contribute more to the aroma of the cannabis plant, while sesquiterpenes are more stable and less likely to break down during plant processing. Each cannabis strain has a unique terpene profile which contributes to the different psychoactive and medicinal properties of each strain11. Recent research has found terpene compounds to have a myriad of potential medicinal properties including, but not limited to, anti-inflammatory, anxiety-reducting (anxiolytic) and antidepressant effects in humans and mice1,6,12,13. Two candidate terpenes from the super class with potential therapeutic effects are β-caryophyllene and ⍺-pinene.

β-caryophyllene (βCP), is one of the major sesquiterpenes found in cannabis3,8,14 and is also present in clove, rosemary, black pepper, and lavender. To date, studies have shown this compound to have anticancer properties as well as anti-inflammatory properties12,15,16. Additionally, Galdino and colleagues17 found that mice dosed with βCP displayed anxiolytic behaviour in the elevated plus maze and light dark test. They also found βCP to decrease latency to sleep and increased duration of sleep time. A similar study by Bahi and colleagues13 found that mice dosed with βCP also showed reduced anxiety-like behaviour in the elevated plus maze, open field test, and marble-burying test. Mice also demonstrated anti-depressive behaviour in behavioural assays validated for measuring depression, such as the novelty suppressed feeding and tail suspension tests. Machado and colleagues14 also demonstrated the anxiolytic effects of βCP on mice in the light/dark test. Rabbani and colleagues18 found that a hydroalcoholic extract of βCP (at 150 and 200 mg kg−1) showed anxiolytic effects similar to diazepine (at 0.5 mg kg−1) on mice in the elevated plus maze. βCP shows promise as an anxiolytic compound, however, there are no studies to date on its effects in zebrafish models.

In addition to the number of pairs of isoprene molecules, terpenes also differ in regard to whether they are monocyclic or bicyclic19. Bicyclic terpenes are a set of optical isomers (enantiomers) that are non-superimposable mirror images of each other19. Pinene is a bicyclic compound and one of the most prominent cannabis monoterpenes found in nature3, most commonly, in lavender, rosemary, and conifers11,12. Pinene has two constitutional isomers, α-pinene (αPN) and β-pinene (βPN), each are racemic compounds that are separable into S(+) or R(−) enantiomers19. Previous research has shown αPN to have an anxiolytic effect on mice after inhalation of αPN derived from cypress of the genus, Chamaecyparis obtuse20, and from pine of the genus, Pinus21. Satou and colleagues20 found mice dosed with αPN demonstrated decreased anxiety behaviour in the elevated plus maze, and its effects to be maintained after repeated exposure. Yang and colleagues21 also found αPN to enhance sleep duration, quality, and brain wave density by direct binding to GABAA receptors. αPN has also shown to have strong anti-inflammatory and antibiotic properties3. Additionally, enantiomers from each pinene compound have different effects19: The positive enantiomers, (+)-αPN and (+)-βPN, exhibited significantly higher antimicrobial effects when compared to the negative enantiomers. Some enantiomers can produce opposite behavioural effects, like the ketamine analog, methoxetamine22. The extent to which αPN enantiomers may vary in their ability to alter behaviour is unknown.

Zebrafish (Danio rerio) are a well-established model for testing neurobiology and drug action. Recently, Murr7 demonstrated the anticonvulsant effects of two terpenes commonly found in cannabis, myrcene and limonene, on zebrafish induced with epileptic-like seizures. In an acute dosing experiment, limonene and myrcene were shown to decrease zebrafish anxiety-like behaviour in the open field exploration test while linalool demonstrated a sedative effect on zebrafish locomotion23. There are many empirically validated behavioural assays for testing zebrafish anxiety-like behaviour and boldness, which include the open field-exploration test and novel object approach test. The open field exploration test is a commonly used paradigm, adapted from rodent models, that has been validated to measure zebrafish anxiety-like behaviour24–26. In this test, anxiety-like behaviour is measured by the amount of time the zebrafish spends in specific zones of the arena. Within the arena are 3 significant zones: the outer zone, known as the thigmotaxis zone, in which a fish may demonstrate anxiety-like (escape or centrophobic) behaviour by hugging the walls of the arena, the transition zone which leads to the center of the arena, and the inner zone or center zone. The duration of time spent in the inner zone can be indicative of exploratory behaviour into the ‘less protected' center of the arena, which is associated with a decrease in anxiety-like behaviour24. Along with cumulative duration in arena zones, alterations in locomotion such as swimming velocity and immobility may also be indicative of anxiety-like behaviour. The novel object approach test is another common paradigm among zebrafish models, where an unfamiliar object is placed into the open field testing arena and is used to quantify anxiety-like behaviour by avoidance or boldness27. Avoidance is calculated by time spent in the thigmotaxis zone away from the object and is indicative of heightened anxiety due to an unfamiliar object in the arena. Boldness is assessed by calculating the increased time spent in the center zone near the novel object24. In a study by Hamilton and colleagues28, the administration of ethanol (a common and reliable anxiolytic drug used in animal research) in zebrafish significantly increased the number of approaches to a novel object and cumulative time spent close to the object. As previously mentioned, alterations in locomotor behaviour relative to the introduction of the novel object may also indicate levels of anxiety in this test.

Of the eight super class terpenes, the present study tested the anxiolytic effects of commonly found and currently understudied cannabis terpenes, βCP and αPN along with (+) and (−)-αPN enantiomers of αPN, on zebrafish behaviour in two common behavioural paradigms, the open field exploration test and novel object approach test.

Method and materials

Animals and housing

Adult zebrafish (Danio rerio) of mixed gender (~ 50:50, male:female) were obtained from MacEwan University’s in-house breeding facility in December of 2020 and February of 2021. Broodstock zebrafish were obtained from the University of Ottawa (Ottawa, ON, Canada). All zebrafish were from a wild-type strain. Zebrafish were housed in 3 L and 10 L polyurethane tanks within an Aquatic Habitats (AHAB, Aquatic Ecosystems, Inc. Apopka, FL, USA) three-tier bench top system. Housing facility water consisted of reverse osmosis water buffered with non-iodized salt, sodium bicarbonate, acetic acid and maintained to a pH of 6.5 to 8.0. Housing facility water was continuously re-circulated and filtered through 50 µm of mechanical and activated carbon, UV irradiated, and maintained at 26 to 30 °C. Zebrafish were on a 12-h light/dark cycle from 8:00 AM to 8:00 PM and were fed once daily with Gemma Micro 300 fish flakes (Gemma Micro, Maine, USA). Fish were not fed on testing days until after experiments were conducted.

Drug administration

Terpene solutions were made fresh daily by adding each treatment dose to 400 mL of housing facility water. Due to low solubility, terpene solutions were stirred vigorously and left to dissolve for up to 25 min until there were no visible residual oils in the dosing beaker. Solution pH was monitored before and after the addition of terpene compounds and stayed within a pH of 6.8–7.5. The treatment vessel (i.e. dosing beaker) was surrounded by white corrugated plastic to reduce any behavioural alterations due to visual conspecific cues29. Individual zebrafish randomly assigned to either a control group or to one of the terpene conditions remained in the solution for 10 min.

β-caryophyllene

β-caryophyllene (≥ 80% sum of isomers; sourced from SIGMA, Ontario, Canada), was mixed into a 600 mL dosing beaker containing 400 mL of housing facility water in 0.02 (0.98 μmol; n = 27), 0.2 (9.8 μmol; n = 18), and 2.0% (98.0 μmol; n = 17) doses. The control solution consisted of 400 mL of housing facility water (n = 21). Our starting dose was determined by pilot testing and doses used in a previous terpene study with zebrafish23. An additional experimental group was added with 4% (195.7 μmol; n = 19). β-caryophyllene dissolved in 0.1% ethanol (EtOH) in 400 mL of housing facility water to test solubility effects and increase the terpene dose. The control solution for this group was made with 400 mL of housing facility water mixed with 0.1% EtOH (n = 24).

(+ /−)-α-pinene

(+ /−)-α-pinene (98%; sourced from Sigma-Aldrich, Ontario, Canada), was mixed into a 600 mL dosing beaker containing 400 mL of housing facility water with 0.01 (0.73 μmol; n = 23), 0.02 (1.5 μmol; n = 24), and 0.1% (7.3 μmol; n = 20) doses. The control solution consisted of 400 mL of housing facility water (n = 32). All pinene doses were based on careful pilot testing and previous murine studies where an oral administration of 10 μL/L (0.01%) of α-pinene was shown to be an effective dose for mice30.

S(+)-α-pinene

S(+)-α-pinene (≥ 99%; sourced from Sigma-Aldrich) was mixed into a 600 mL dosing beaker containing 400 mL of housing facility water with 0.01 (0.73 μmol; n = 13), 0.02 (1.5 μmol; n = 13), and 0.1% (7.3 μmol; n = 13) doses. The control solution consisted of 400 mL of housing facility water (n = 13).

R(−)-α-pinene

R(−)-α-pinene (99%; sourced from Sigma-Aldrich) was mixed into a 600 mL dosing beaker containing 400 mL of housing facility water with 0.01 (0.73 μmol; n = 15), 0.02 (1.5 μmol; n = 16) and 0.1% (7.3 μmol; n = 13) doses. The control solution consisted of 400 mL of housing facility water (n = 19).

Behavioural testing

Open field exploration test

All behavioural testing protocols used in this study were based on a previous study conducted by Szaszkiewicz and colleagues23. Experimentally naïve fish were acclimated in the housing facility for a minimum of one week prior to testing. On testing days, zebrafish were transferred by netting into a 3 L polyurethane habituation tank from the housing facility in the testing room. Prior to experimentation, zebrafish were habituated in the testing room for approximately 25 min. Habituation tanks were fully surrounded by white corrugated plastic to reduce exposure to extraneous visual stimuli. After habituation, individual zebrafish were netted into a 600 mL dosing beaker containing either the terpene or control solutions as described above. Control fish were chosen by random selection and interspersed throughout testing days to control for any time-of-day effects. After dosing, individual zebrafish randomly assigned to either a control group or to one of the terpene conditions were immediately netted and placed into the open field testing arena. After 10 min in an open field testing arena, a novel object was then introduced and fish behaviour recorded for an additional 10 min (Fig. 1C).

Figure 1.

Testing Apparatus. (A) The open field testing arena consisted of a white plastic cylinder (26.0 cm in diameter) filled to a water depth of 5.0 cm. (B) For the novel object approach test, a multicoloured Lego figurine with a height of 4.25 cm was affixed to the center of the open field arena using a ′1 × 2′ Lego brick. The test arena was partitioned into three zones in EthoVision XT motion tracking software (inner, transition, and outer zones). (C) Diagram of experimental procedure: Individual fish were netted from the housing facility into a dosing beaker for 10-min of terpene exposure, then transferred to the open field arena. After a 10-min trial in the open field test, a Lego figurine was placed into the center of the arena for the 10-min novel object approach test trial.

The open field testing apparatus was a 26 cm circular plastic arena with a height of 11.5 cm and water level filled to 5 cm (Fig. 1A). The testing arena was enclosed by three walls comprised of white corrugated plastic to minimize exposure to extraneous visual stimuli. Fish were individually netted and placed into the testing arena halfway between the center and thigmotaxis zones. Recording of the fish then began and trials lasted 10 min. Proxies used to measure anxiety-like behaviour for the main variables of interest were the cumulative duration of time spent in the thigmotaxis (outer) zone and time spent in the inner zone. Locomotor variables, velocity and immobility, were also assessed. Zones were created within Noldus EthoVision XT software (v. 11.0, Noldus, Wageningen, NL) and included annular zones consisting of a center zone of 8.6 cm, a transition zone of 4.3 cm, and a thigmotaxic zone of 4.3 cm (Fig. 1B).

Novel object approach test

After a duration of 10 min in the open field exploration test, a novel object was added to the middle of the testing arena and swimming behaviour was recorded for another 10 min. The novel object was a multicoloured Lego figurine (2 cm × 4.25 cm; Fig. 1B) affixed to the bottom of the center of the tank by a small 1 × 2 Lego brick. Behaviour was quantified by time spent in arena zones relative to the novel object, in this case the thigmotaxis and center zone, as well as locomotor variables, velocity and immobility. After every fifth or sixth trial the H2O in the testing arena would be refreshed to prevent build-up of waste and excess terpene compound, and to maintain water temperature31. Once each trial ended, zebrafish were sexed and placed back into a housing tank and fed. The water temperature in the housing tank of experimental zebrafish, drug solution, and testing arenas was kept between 26 and 28 °C with seedling heat mats (Hydrofarm Horticultural Products, Petaluma CA). Luminance in all testing arenas was measured at ~ 32 8 cd/m3 (cal SPOT photometer; Cooke Corp. CA, USA). A Basler GenICam acA1300-60gc Area Scan video camera (Basler Inc., USA) was suspended approximately 1 m above testing arenas to record zebrafish behaviour. Zebrafish movement was tracked and recorded using EthoVision XT tracking software. Researchers were not blinded to treatment, however, all fish were tested in an identical manner and analyzed using a motion-tracking software system. Immobility was determined at a 5% threshold, whereby, a fish would be considered immobile if tracking software detected less than a 5% change in the pixels of the body of the fish23.

Statistical analysis

All data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism Software (Version 9.1.2; GraphPad, San Diego, CA, USA). Data were assessed for normality using the D’Agostino-Pearson omnibus normality test and Bartlett’s test for equality of variances. Parametric data was analyzed using an ordinary one-way ANOVA followed by post-hoc Dunnett’s multiple comparison test. Non-parametric data was analyzed using a Kruskal–Wallis with post-hoc Dunn’s multiple comparison test. The Brown-Forsythe ANOVA was used for data with unequal variance. An alpha level of p < 0.05 and a 95% confidence interval was used to indicate statistical significance. All values are presented as mean ± standard error in measurement (S.E.M.). Data were omitted for fish in treatment groups that reacted with heightened sensitivity and displayed extreme sedation and locomotor impairment during testing. Data were also excluded from analyses if the full data was not acquired by tracking software for the total time each fish spent in the arena. This resulted in the following number of fish removed per condition: 0% (+ /−)-αPN group (n = 2), 0.01% (+ /−)-αPN group (n = 1), 0.02% (+ /−)-αPN group (n = 1), 0% (−)-αPN group (n = 6), 0.01% (−)-αPN group (n = 7), 0.02% (−)-αPN group (n = 4), 0.1% (−)-αPN group (n = 4), 0% (+)-αPN group (n = 7), 0.01% (+)-αPN (n = 10), 0.1% (+)-αPN group (n = 2), 0% βCP group (n = 4), 0.02% βCP group (n = 3), 2.0% βCP group (n = 4), 4.0% βCP group (n = 4). These fish were not included in the sample sizes noted in 2.2. In the βCP experiment, data from the control group and 0.1% EtOH (used as a vehicle control for 4.0%), were compared and no significant differences in fish behaviour were found so control groups were combined.

Ethics statement

All experiments were approved by the MacEwan University Animal Ethics Board (AREB) under protocol number 101853 in compliance with the Canadian Council for Animal Care (CCAC) experimental guidelines. All authors complied with ARRIVE guidelines.

Results

Effects of (+ /−)-α-pinene in the open field exploration test

Time in Zones. (+ /−)-αPN did not have a significant effect on duration of time spent in the inner zone between groups (F(3, 59.97) = 2.061, p = 0.115; Fig. 2A). (+ /−)-αPN did not have a significant effect on duration of time spent in the thigmotaxis zone between groups (F(3, 56.39) = 2.679, p = 0.056; Fig. 2B).

Figure 2.

The effects of (+ /−)-alpha-pinene administration in the open field test. Average duration of time fish spent in the (A) inner and (B) outer, ‘thigmotaxis’ zone during the open field test. Fish locomotion was quantified in the open field test by measuring (C) swimming velocity and (D) time spent immobile. All data are presented as mean ± S.E.M. Significant differences between controls and (+ /−)-alpha-pinene treated groups are indicated by **(p < 0.05).

Locomotion. (+ /−)-αPN did not have a significant effect on velocity between groups (F(3, 95) = 0.4171, p = 0.741; Fig. 2C). (+ /−)-αPN did have a significant effect on duration of time spent immobile between groups (F(3, 64.29) = 2.780, p = 0.048). A post-hoc analysis using Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test found a significant decrease in time spent immobile in the 0.1% group (5.6 ± 1.9 s, n = 20, p = 0.008) when compared to the control group (38.1 ± 9.8 s, n = 32; Fig. 2D).

Effects of (+ /−)-α-pinene in the novel object approach test

Time in Zones. (+ /−)-αPN did not have a significant effect on duration of time spent in the inner zone between groups (F(3, 73.26) = 1.196, p = 0.317; Fig. 3A). (+ /−)-αPN did not have a significant effect on duration of time spent in the thigmotaxis zone between groups (H(4) = 0.4499, p = 0.93; Fig. 3B).

Figure 3.

The effects of (+ /−)-alpha-pinene administration in the novel object approach test. Average duration of time fish spent in the (A) inner and (B) outer ‘thigmotaxis’ zone during the novel object approach test. Fish locomotion was quantified in the novel object approach test by measuring (C) swimming velocity and (D) time spent immobile. All data are presented as mean ± S.E.M. Significant differences between controls and (+ /−)-alpha-pinene treated groups are indicated by **(p < 0.05).

Locomotion. (+ /−)-αPN did not have a significant effect on velocity between groups (F(3, 95) = 1.005, p = 0.394; Fig. 3C). (+ /−)-αPN did have a significant effect on duration of time spent immobile between groups (F(3, 75.03) = 3.693, p = 0.016). A post-hoc analysis using Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test found a significant decrease in time spent immobile in the 0.1% group (0.88 ± 0.3 s, n = 20, p = 0.03) when compared to the control group (71.8 ± 19.5 s, n = 32; Fig. 3D).

Effects of (−)-α-pinene in the open field exploration test

Time in Zones. (−)-αPN had a significant effect on duration of time spent in the inner zone between groups (F(3, 23.28) = 13.36, p < 0.001). A post-hoc analysis using Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test found a significant increase in time spent in the inner zone in the 0.1% group (108.6 ± 20.9 s, n = 13, p = 0.003) when compared to the control group (19.6 ± 6.3 s, n = 19; Fig. 4A). (−)-αPN had a significant effect on duration of time spent in the thigmotaxis zone between groups (F(3, 26.37) = 25.01, p < 0.001). A post-hoc analysis using Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test found a significant decrease in time spent in the thigmotaxis zone in the 0.1% group (275.2 ± 38.76 s, n = 13, p < 0.001) when compared to the control group (510.2 ± 11.9 s, n = 19; Fig. 4B).

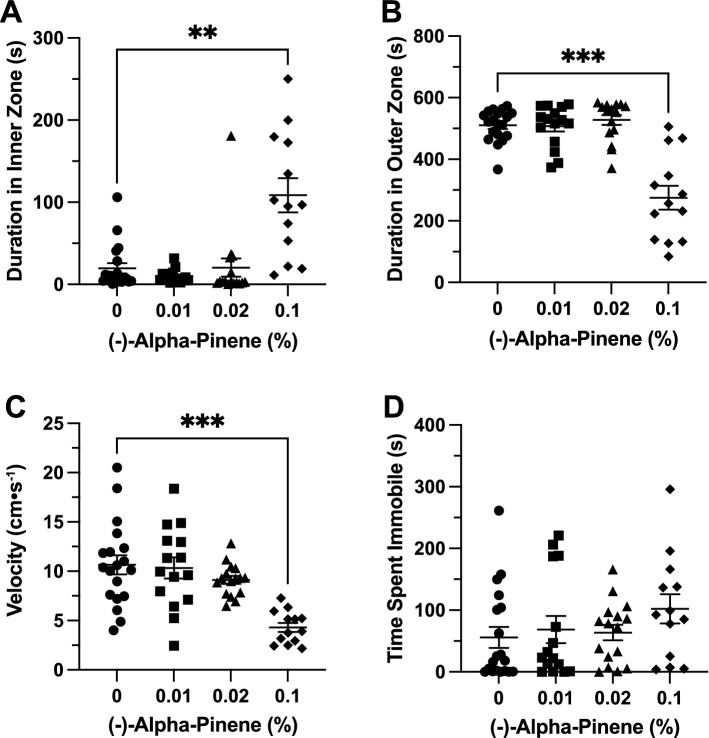

Figure 4.

The effects of (−)-alpha-pinene administration in the open field test. Average duration of time fish spent in the (A) inner and (B) outer ‘thigmotaxis’ zone during the open field test. Fish locomotion was quantified in the open field test by measuring (C) swimming velocity and (D) time spent immobile. All data are presented as mean ± S.E.M. Significant differences between controls and (−)-alpha-pinene treated groups are indicated by **(p < 0.01) and ***(p < 0.001).

Locomotion. (−)-αPN had a significant effect on velocity between groups (F(3, 59) = 11.18, p < 0.001). A post-hoc analysis using Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test indicated significant decreases in velocity between the 0.1% (4.3 ± 0.5 cm s−1, n = 13, p < 0.001) group when compared to the control group (10.7 ± 0.97 cm s−1, n = 19; Fig. 4C). (−)-αPN did not have a significant effect on duration of time spent immobile between groups (H(4) = 4.16, p = 0.25; Fig. 4D).

Effects of (−)-α-pinene in the novel object approach test

Time in Zones. (−)-αPN did not have a significant effect on duration of time spent in the inner zone between groups (F(3, 32.06) = 0.9235, p = 0.441; Fig. 5A). (−)-αPN did not have a significant effect on duration of time spent in the thigmotaxis zone between groups (H(4) = 9.25, p = 0.026; Fig. 5B).

Figure 5.

The effects of (−)-alpha-pinene administration in the novel object approach test. Average duration of time fish spent in the (A) inner and (B) outer ‘thigmotaxis’ zone during the novel object approach test. Fish locomotion was quantified in the novel object approach test by measuring (C) swimming velocity and (D) time spent immobile. All data are presented as mean ± S.E.M. Significant differences between controls and (−)-alpha-pinene treated groups are indicated by ***(p < 0.001).

Locomotion. (−)-αPN did have a significant effect on velocity between groups (F(3, 48.26) = 8.240, p < 0.001). A post-hoc analysis using Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test indicated significant decreases in velocity between the 0.1% (5.7 ± 0.5 cm s−1, n = 13, p < 0.001) group when compared to the control group (11.1 ± 1.0 cm s−1, n = 19; Fig. 5C). (−)-αPN did not have a significant effect on duration of time spent immobile between groups (H(4) = 4.294, p = 0.231; Fig. 5D).

Effects of (+)-α-pinene in the open field exploration test

Time in Zones. (+)-αPN had a significant effect on duration of time spent in the inner zone between groups (F(3, 19.45) = 8.657, p < 0.001). A post-hoc analysis using Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test found a significant increase in time spent in the inner zone in the 0.02% group (140.9 ± 37.2 s, n = 13, p = 0.011) when compared to the control group (6.6 ± 1.8 s, n = 13; Fig. 6A). (+)-αPN had a significant effect on duration of time spent in the thigmotaxis zone between groups (F(3, 30.83) = 27.5, p < 0.0001). A post-hoc analysis using Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test found a significant decrease in time spent in the thigmotaxis zone in the 0.01% (425.1 ± 38.1 s, n = 13, p = 0.018) and 0.02% (219.6 ± 38.0 s, n = 13, p < 0.0001) groups when compared to the control group (552.4 ± 7.7 s, n = 13; Fig. 6B).

Figure 6.

The effects of (+)-alpha-pinene administration in the open field test. Average duration of time fish spent in the (A) inner and (B) outer ‘thigmotaxis’ zone during the open field test. Fish locomotion was quantified in the open field test by measuring (C) swimming velocity and (D) time spent immobile. All data are presented as mean ± S.E.M. Significant differences between controls and (+)-alpha-pinene treated groups are indicated by *(p < 0.01), **(p < 0.001), and ****(p < 0.0001).

Locomotion. (+)-αPN had a significant effect on velocity between groups (F(3, 37.48) = 16.05, p < 0.0001). A post-hoc analysis using Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test indicated significant decreases in velocity between the 0.01% (6.3 ± 1.2 cm s−1, n = 13, p = 0.001) and 0.02% (2.5 ± 0.4 cm s−1, n = 13, p < 0.0001) groups when compared to the control group (11.8 ± 1.1 cm s−1, n = 13; Fig. 6C). (+)-αPN had a significant effect on duration of time spent immobile between groups (F(3, 32.63) = 15.15, p < 0.0001). A post-hoc analysis using Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test indicated significant increases in immobility between the 0.01% (112.6 ± 29.9 s, n = 13, p = 0.015), 0.02% (208.0 ± 21.5 s, n = 13, p < 0.0001), and 0.1% (73.02 ± 21.2 s, n = 13, p = 0.034) groups when compared to the control group (10.3 ± 3.5 s, n = 13; Fig. 6D).

Effects of (+)-α-pinene in the novel object approach test

Time in Zones. (+)-αPN had no significant effect on duration of time spent in inner zone between groups (F(3, 25.6) = 0.6124, p = 0.613; Fig. 7A). (+)-αPN had a significant effect on duration of time spent in the thigmotaxis zone between groups (F(3, 28.96) = 5.379, p = 0.005). A post-hoc analysis using Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test found a significant decrease in time spent in the thigmotaxis zone in the 0.02% group (457.1 ± 33.4 s, n = 13, p = 0.017) when compared to the control group (570.0 ± 11.5 s, n = 13; Fig. 7B).

Figure 7.

The effects of (+)-alpha-pinene administration in the novel object approach test. Average duration of time fish spent in the (A) inner and (B) outer ‘thigmotaxis’ zone during the novel object approach test. Fish locomotion was quantified in the novel object approach test by measuring (C) swimming velocity and (D) time spent immobile. All data are presented as mean ± S.E.M. Significant differences between controls and (+)-alpha-pinene treated groups are indicated by *(p < 0.05) and **(p < 0.01).

Locomotion. (+)-αPN had a significant effect on velocity between groups (F(3, 48) = 5.855, p = 0.002). A post-hoc analysis using Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test indicated significant decreases in velocity between the 0.01% (6.4 ± 1.3 cm s−1, n = 13, p = 0.028) and 0.02% (4.8 ± 1.1 cm s−1, n = 13, p = 0.002) groups when compared to the control group (10.9 ± 1.2 cm s−1, n = 13; Fig. 7C). (+)-αPN had a significant effect on duration of time spent immobile between groups (F(3, 30.77) = 4.568, p = 0.009). A post-hoc analysis using Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test found a significant increase in immobility in the 0.02% group (144.7 ± 36.4 s, n = 13, p < 0.01) when compared to the control group (13.2 ± 6.2 s, n = 13; Fig. 7D).

Effects of β-caryophyllene in the open field exploration test

Time in Zones. βCP had no significant effect on duration of time spent in inner zone between groups (F(4, 53.64) = 1.337, p = 0.268; Fig. 8A). βCP had no significant effect on duration of time spent in thigmotaxis zone between groups (H(5) = 2.412, p = 0.66; Fig. 8B).

Figure 8.

The effects of beta-caryophyllene administration in the open field test. Average duration of time fish spent in the (A) inner and (B) outer ‘thigmotaxis’ zone during the open field test. Fish locomotion was quantified in the open field test by measuring (C) swimming velocity and (D) time spent immobile. All data are presented as mean ± S.E.M.

Locomotion. βCP had no significant effect on velocity between groups (H(5) = 5.083, p = 0.279; Fig. 8C). βCP also had no significant effect on duration of time spent immobile between groups (F(4, 75.85) = 2.150, p = 0.083; Fig. 8D).

Effects of β-caryophyllene in the novel object approach test

Time in Zones. βCP had no significant effect on duration of time spent in inner zone between groups (F(4, 48.69) = 0.5634, p = 0.69; Fig. 9A). βCP had no significant effect on duration of time spent in thigmotaxis zone between groups (F(4, 110.9) = 0.2597, p = 0.903; Fig. 9B).

Figure 9.

The effects of beta-caryophyllene administration in the novel object approach test. Average duration of time fish spent in the (A) inner and (B) outer ‘thigmotaxis’ zone during the novel object approach test. Fish locomotion was quantified in the novel object approach test by measuring (C) swimming velocity and (D) time spent immobile. All data are presented as mean ± S.E.M. Significant differences between controls and beta-caryophyllene treated groups are indicated by *(p < 0.05).

Locomotion. βCP had no significant effect on velocity between groups (H(5) = 2.331, p = 0.675; Fig. 9C). βCP did have a significant effect on duration of time spent immobile between groups (F(4, 97.77) = 3.033, p = 0.021). A post-hoc analysis using Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test found a significant decrease in immobility in the 4.0% group (17.9 ± 8.4 s, n = 19, p < 0.05) when compared to the control group (60.7 ± 14.3 s, n = 45; Fig. 9D).

Discussion

This study investigated the anxiolytic and locomotor effects of two commonly found cannabis terpenes in North American cannabis strains, α-pinene and its optical (+) and (−) enantiomers, and β-caryophyllene, using the open field exploration test and the novel object approach test. While (+ /−)-αPN showed no effects on either anxiety variables measured in both tests, both (+) and (−) αPN enantiomers decreased anxiety-like behaviour in the open field test by significantly increasing time spent in the inner zone and decreasing time spent in the thigmotaxis zone. In both (+) and (−) groups, however, significant effects on behaviour were decreased or eliminated with the introduction of a novel object. Interestingly, (−)-αPN demonstrated strong anxiolytic effects at our highest (0.1%) treatment group. While (+)-αPN demonstrated anxiolytic effects only at the low (0.01%) and moderate (0.02%) treatment groups. (+ /−)-αPN had no effect on velocity while significantly decreasing immobility in both open field and novel object approach tests. Significant decreases in velocity and increases in immobility were found in both the low and moderate (+)-αPN doses, however, in both open field and novel object approach, (−)-αPN significantly decreased velocity at our highest dose but had no effect on immobility. βCP had no effect on either anxiety measure or velocity across both behavioural tests. Interestingly, however, βCP did significantly decrease immobility in the novel object approach test.

Increased swimming velocity and immobility have been suggested to indicate heightened levels of anxiety in previous studies with zebrafish24,32–41. However, measures of velocity and immobility have not consistently corresponded to main effect measures of anxiety-like behaviour across most zebrafish behavioural paradigms42. This suggests locomotor responses vary depending on the test used. For example, increased swimming velocity may correspond to avoidance behaviour and heightened anxiety, or more risky behaviour (increased exploration) and decreased anxiety. Similarly, increased immobility may suggest a freezing response associated with anxiety, or lack of movement associated with sedation and a relaxed state. Furthermore, decreased velocity may also suggest a sedative response rather than an anxiolytic response. Therefore, it is necessary to validate the reliability of these measures in relation to zebrafish anxiety-like behaviour and the behavioural test being used25.

Fish in both (+) and (−) αPN enantiomer groups in the open field and novel object approach tests demonstrated a significant reduction in swimming velocity. However, fish in the (+) enantiomer group had a significant difference in immobility, whereas the (−) enantiomer group had no change in immobility. Therefore, the decreased velocity and increased immobility induced by (+)-αPN suggests a strong sedative effect, while (−)-αPN has only minor sedative action. Further testing with a higher (−)-αPN dose is required to determine whether (−)-αPN will show a similar non-linear, sedative effect at higher doses. Interestingly, counter to the effect on immobility observed in the (+)-αPN group, (+ /−)-αPN decreased immobility in both open field and novel object approach tests. This finding demonstrates (+ /−)-⍺-pinene and each of its (+) and (−) isomeric compounds have differential anxiety-like and locomotor behavioural effects at different doses.

βCP had no effect across all variables of interest in the open field test or novel object approach test in any of the treatment groups when compared to the control, aside from a modest decrease in immobility in the novel object approach test in the highest dose used (4.0%). Several studies using mice have reported βCP to display an anxiolytic effect at higher doses13,14,17,18. Due to the novel nature of this study, no dose parameters for βCP have been validated to reliably produce a behavioural alteration in zebrafish models, therefore, further pilot testing is needed. Our results show a potential dose-dependent downward trend in anxiety levels, which suggests that a higher dose may be effective. However, due to the low aqueous solubility of the compound it was not possible to increase the dose level beyond what was employed here. In addition to poor water solubility, previous pharmacokinetic studies have noted βCP to be highly volatile and sensitive to light, oxygen, humidity, and high temperatures43, which may inhibit bioavailability of the terpene. Therefore, the observed weak or non-effect of this compound could be attributed to a low absorption rate, as well as metabolism and excretion rate. Further behavioural testing is required to assess whether a higher dose or different delivery method will elicit a significant response.

Phytocannabinoids found in cannabis are exogenous ligands that act on the cannabinoid receptors found in most species of the animalia kingdom44. For example, both phytocannabinoids, ∆9-THC and CBD, bind to CB1 and CB2 receptors in the endocannabinoid system45,46. Thus, it is feasible that the terpene compounds found in cannabis plants may also act on cannabinoid receptors. While ∆9-THC and CBD are known to produce anxiolytic and other therapeutic effects, it is unknown whether this may be due to the modulatory effects of other cannabis constituents such as terpene compounds47. Russo1 demonstrated the ‘entourage effect’ showing how terpenes may actually alter the effects of phytocannabinoids. However, recent studies exploring the entourage effect did not detect CB receptor-mediated modulations of terpenes on the effects of THC or CBD48–50. With recent studies demonstrating terpene compounds to have similar effects as THC and CBD on endocannabinoid receptors, it is important to test their mechanisms of action and medicinal properties in isolation from other properties of the cannabis plant47,50.

The endocannabinoid system, specifically cannabinoid CB1 and CB2 receptors, have been shown to regulate mood and anxiety disorders51–53. CB1 receptors are distributed across the central nervous system (CNS) and are known to decrease the release of dopamine, norepinephrine, glutamate, and serotonin, while CB2 is said to be associated with the immune system44,54,55. Interestingly, several studies have shown that the effects of βCP are mediated through the selective binding to CB2 receptors because a CB2 antagonist eliminated its effects13,16,56. However, other studies have shown that βCP may not act on endocannabinoid receptors48,49, thus its mechanism of action in the brain is unclear. If βCP acts on CB2 receptor sites this may contribute to its potential to have anxiolytic and antidepressant effects in animals5,13. Bahi and colleagues13 describe that previously, CB2 receptors were thought to be absent in the brain, but have now been identified in the CNS and play a role in anxiety and depressive-related disorders. Although βCP’s mechanism of action has not been clearly defined, it has shown potential to act on CB2 receptors13,16,56. Bahi and colleagues13 postulate that drug alternatives acting through CB2 receptors could become novel pharmacological therapies in the treatment of anxiety and mood disorders.

Molecular research demonstrates that both the endocannabinoid and GABAergic systems are associated with the pathophysiology of anxiety and related disorders57,58. While αPN has not been shown to have an affinity for CB1 or CB2 receptors12, it has been demonstrated to interact with the GABAA receptor complex to prolong GABAergic synaptic transmission21,59, which is likely to contribute to its potential sedative and anxiolytic effects11,20,30. ⍺-pinene has been shown to target certain GABA neurons resulting in a range of psychophysiological effects21. Specifically, ⍺-pinene acts on GABA neurons by generating a presynaptic response to signal neurons to inhibit GABA reuptake transporters which can alleviate symptoms of anxiety and insomnia46.

Studies have identified GABAA receptors in zebrafish and researchers have found they possess a conserved GABAergic system60–63. Zebrafish have also been shown to express all of the major endocannabinoid-related genes, such as, CB1 and CB264,65, and are a relatively efficient experimental model for the anxiolytic effects of cannabinoids and terpenes. Therefore, future studies exploring the mechanisms of action with terpene administration along with CB1 and CB2 antagonists, and selective binding of βCP and ⍺PN on zebrafish receptor sites could provide substantial evidence of the potential interaction of terpenes and cannabinoids.

Conclusion

(+ /−)-⍺-pinene and its (+) and (−) enantiomers each demonstrated varying effects on zebrafish anxiety-like and locomotor behaviours. (+ /−)-⍺PN had no effects on the anxiety measures, time spent in zones, but had a modest effect on time spent immobile in the highest dose (0.1%). The highest dose of (−)-⍺PN showed a modest effect on time spent in zones and zebrafish swimming velocity but not immobility, while (+)-⍺PN showed a strong effect across all variables, primarily in the low and moderate doses. In both groups, anxiolytic effects in the open field test were reduced or eliminated with the introduction of a novel object. These results demonstrate the differential dose-dependent effect of (+ /−)-⍺-pinene and each of its (+) and (−) isomeric compounds. β-caryophyllene had little to no effect across tests on any of the variables analyzed in this study, therefore, further testing is required to determine if a higher dose would yield significant results.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the husbandry student volunteers and animal care technician, Aleah McCorry, for their help with daily husbandry and aquarium maintenance.

Author contributions

A.J. carried out experiments, data analysis and drafted the manuscript. A.S. carried out data analysis and experiments. I.E. carried out data analysis and experiments. T.J.H. conceived of the study and participated in research coordination and manuscript editing. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This research received funding from Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC) Discovery Development grant to T.J.H. (05426), MacEwan Strategic Research grant to T.J.H., and the MacEwan Undergraduate Student Research Initiative (USRI) grant to A.J.

Data availability

Available upon request. Correspondence and requests for materials should be addressed to T.J.H. or A.J. [JohnsonA254@mymacewan.ca]. Analyzed data from Noldus EthoVision XT tracking software is available in the electronic supplementary material.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-022-21552-2.

References

- 1.Russo EB. Taming THC: Potential cannabis synergy and phytocannabinoid-terpenoid entourage effects. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2011;163(7):1344–1364. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2011.01238.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alves P, Amaral C, Teixeira N, Correia-da-Silva G. Cannabis sativa: Much more beyond Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol. Pharmacol. Res. 2020;157:104822. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2020.104822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Russo EB, Marcu J. Cannabis pharmacology: The usual suspects and a few promising leads. Cannabinoid Pharmacol. 2017;80:67–134. doi: 10.1016/bs.apha.2017.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Booth JK, Bohlmann J. Terpenes in cannabis sativa—From plant genome to humans. Plant Sci. 2019;284:67–72. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2019.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mudge EM, Brown PN, Murch SJ. The terroir of cannabis: Terpene metabolomics as a tool to understand Cannabis sativa selections. Planta Med. 2019;85:781–796. doi: 10.1055/a-0915-2550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sommano SR, Chittasupho C, Ruksiriwanich W, Jantrawut P. The cannabis terpenes. Molecules. 2020;25(24):5792. doi: 10.3390/molecules25245792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Murr, C. Use of a zebrafish model to identify anticonvulsant properties of cannabinoid and terpenoid extracts and mixtures. LSU Master's Theses (2021). https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses/5294

- 8.Booth JK, Page JE, Bohlmann J. Terpene synthases from Cannabis sativa. PLoS ONE. 2017 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0173911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lewis M, Russo E, Smith K. Pharmacological foundations of Cannabis chemovars. Planta Med. 2017;84(04):225–233. doi: 10.1055/s-0043-122240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ferber SG, Namdar D, Hen-Shoval D, Eger G, Koltai H, Shoval G, Shbiro L, Weller A. The “entourage effect”: Terpenes coupled with cannabinoids for the treatment of mood disorders and anxiety disorders. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2020;18(2):87–96. doi: 10.2174/1570159x17666190903103923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gonçalves EC, Baldasso GM, Bicca MA, Paes RS, Capasso R, Dutra RC. Terpenoids, cannabimimetic ligands, beyond the Cannabis plant. Molecules. 2020;25(7):1567. doi: 10.3390/molecules25071567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nuutinen T. Medicinal properties of terpenes found in Cannabis sativa and Humulus lupulus. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2018;157:198–228. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2018.07.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bahi A, Al Mansouri S, Al Memari E, Al Ameri M, Nurulain SM, Ojha S. Β-caryophyllene, a CB2 receptor agonist produces multiple behavioral changes relevant to anxiety and depression in mice. Physiol. Behav. 2014;135:119–124. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2014.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Machado KDC, Paz MFCJ, Oliveira Santos JVD, da Silva FCC, Tchekalarova JD, Salehi B, Cavalcante AADCM. Anxiety therapeutic interventions of β-caryophyllene: A laboratory-based study. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2020;15(10):3. doi: 10.1177/1934578x20962229. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fidyt K, Fiedorowicz A, Strządała L, Szumny A. β-caryophyllene and β-caryophyllene oxide-natural compounds of anticancer and analgesic properties. Cancer Med. 2016;5(10):3007–3017. doi: 10.1002/cam4.816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gertsch J. Anti-inflammatory cannabinoids in diet—Towards a better understanding of CB2 receptor action? Commun. Integr. Biol. 2008;1(1):26–28. doi: 10.4161/cib.1.1.6568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Galdino PM, Nascimento MV, Florentino IF, Lino RC, Fajemiroye JO, Chaibub BA, de Paula JR, de Lima TC, Costa EA. The anxiolytic-like effect of an essential oil derived from Spiranthera odoratissima A. St. Hil. leaves and its major component, β-caryophyllene, in male mice. Progress Neuro Psychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry. 2012;38(2):276–284. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2012.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rabbani M, Sajjadi SE, Vaezi A. Evaluation of anxiolytic and sedative effect of essential oil and hydroalcoholic extract of Ocimum basilicum L. and chemical composition of its essential oil. Res. Pharmaceut. Sci. 2015;10(6):535–543. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Silva ACR, Lopes PM, Azevedo MM, Costa DC, Alviano CS, Alviano DS. Biological activities of A-pinene and β-pinene enantiomers. Molecules. 2012;17(6):6305–6316. doi: 10.3390/molecules17066305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Satou T, Kasuya H, Maeda K, Koike K. Daily inhalation of α-pinene in mice: Effects on behavior and organ accumulation. Phytother. Res. 2013;28(9):1284–1287. doi: 10.1002/ptr.5105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yang H, Woo J, Pae AN, Um MY, Cho N-C, Park KD, Yoon M, Kim J, Lee CJ, Cho S. α-pinene, a major constituent of pine tree oils, enhances non-rapid eye movement sleep in mice through gabaa-benzodiazepine receptors. Mol. Pharmacol. 2016;90(5):530–539. doi: 10.1124/mol.116.105080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Botanas CJ, Perez Custodio RJ, Kim HJ, de la Pena JB, Sayson LV, Ortiz DM, Kim M, Lee HJ, Acharya S, Kim K-M, Lee CJ, Ryu JH, Lee YS, Cheong JH. R (−)-methoxetamine exerts rapid and sustained antidepressant effects and fewer behavioral side effects relative to s (+)-methoxetamine. Neuropharmacology. 2021;193:108619. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2021.108619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Szaszkiewicz J, Leigh S, Hamilton TJ. Robust behavioural effects in response to acute, but not repeated, terpene administration in zebrafish (Danio rerio) Sci. Rep. 2021 doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-98768-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maximino C, de Brito TM, Silva Batista AW, Herculano AM, Morato S, Gouveia A., Jr Measuring anxiety in fish: A critical review. Behav. Brain Res. 2010;214(2):157–171. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2010.05.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Blaser RE, Chadwick L, McGinnis GC. Behavioral measures of anxiety in zebrafish (Danio rerio) Behav. Brain Res. 2010;208(1):56–62. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2009.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stewart A, Gaikwad S, Kyzar E, Green J, Roth A, Kalueff AV. Modeling anxiety using adult zebrafish: A conceptual review. Neuropharmacology. 2012;62(1):135–143. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2011.07.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hamilton TJ, Krook J, Szaszkiewicz J, Burggren W. Shoaling, boldness, anxiety-like behavior and locomotion in zebrafish (Danio rerio) are altered by acute benzo[a]pyrene exposure. Sci. Total Environ. 2021;774:145702. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.145702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hamilton TJ, Morrill A, Lucas K, Gallup J, Harris M, Healey M, Pitman T, Schalomon M, Digweed S, Tresguerres M. Establishing zebrafish as a model to study the anxiolytic effects of scopolamine. Sci. Rep. 2017 doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-15374-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dean R, Hurst Radke N, Velupillai N, Franczak BC, Hamilton TJ. Vision of conspecifics decreases the effectiveness of ethanol on zebrafish behaviour. PeerJ. 2021 doi: 10.7717/peerj.10566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kasuya H, Iida S, Ono K, Satou T, Koike K. Intracerebral distribution of a-pinene and the anxiolytic-like effect in mice following inhaled administration of essential oil from chamaecyparis obtuse. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2015;10(8):1479–1482. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hamilton TJ, Radke NH, Bajwa J, Chaput S, Tresguerres M. The dose makes the poison: Non-linear behavioural response to CO2-induced aquatic acidification in zebrafish (danio rerio) Sci. Total Environ. 2021;778:146320. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.146320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gerlai R, Lahav M, Guo S, Rosenthal A. Drinks like a fish: Zebrafish (Danio rerio) as a behavior genetic model to study alcohol effects. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 2000;67(4):773–782. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(00)00422-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Speedie N, Gerlai R. Alarm substance induced behavioral responses in zebrafish (Danio rerio) Behav. Brain Res. 2008;188(1):168–177. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2007.10.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Egan RJ, Bergner CL, Hart PC, Cachat JM, Canavello PR, Elegante MF, Kalueff AV. Understanding behavioral and physiological phenotypes of stress and anxiety in zebrafish. Behav. Brain Res. 2009;205(1):38–44. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2009.06.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cachat J, Stewart A, Grossman L, Gaikwad S, Kadri F, Chung KM, Kalueff AV. Measuring behavioral and endocrine responses to novelty stress in adult zebrafish. Nat. Protoc. 2010;5(11):1786–1799. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2010.140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gebauer DL, Pagnussat N, Piato ÂL, Schaefer IC, Bonan CD, Lara DR. Effects of anxiolytics in zebrafish: Similarities and differences between benzodiazepines, buspirone and ethanol. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 2011;99(3):480–486. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2011.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Grossman L, Stewart A, Gaikwad S, Utterback E, Wu N, DiLeo J, Kalueff AV. Effects of piracetam on behavior and memory in adult zebrafish. Brain Res. Bull. 2011;85(1):58–63. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2011.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Maximino C, Silva AW, Araújo J, Lima MG, Miranda V, Puty B, Herculano AM. Fingerprinting of psychoactive drugs in zebrafish anxiety-like behaviors. PLoS ONE. 2014 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0103943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zahid H, Tsang B, Ahmed H, Lee RC, Tran S, Gerlai R. Diazepam fails to alter anxiety-like responses but affects motor function in a white-black test paradigm in larval zebrafish (Danio rerio) Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry. 2018;83:127–136. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2018.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Alia AO, Petrunich-Rutherford ML. Anxiety-like behavior and whole-body cortisol responses to components of energy drinks in zebrafish (Danio rerio) PeerJ. 2019 doi: 10.7717/peerj.7546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Abozaid A, Gerlai R. Behavioral effects of Buspirone in juvenile zebrafish of two different genetic backgrounds. Toxics. 2022;10(1):22. doi: 10.3390/toxics10010022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Johnson, A., Loh, E., Verbitsky, R., Slessor, J., Franczak, B. C., Schalomon, M., & Hamilton, T. J. Examining zebrafish test sensitivity and locomotor proxies of zebrafish anxiety-like behaviour. Manuscript submitted for publication (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 43.Liu H, Yang G, Tang Y, Cao D, Qi T, Qi Y, Fan G. Physicochemical characterization and pharmacokinetics evaluation of β-caryophyllene/β-cyclodextrin inclusion complex. Int. J. Pharm. 2013;450(1–2):304–310. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2013.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Silver RJ. The endocannabinoid system of animals. Animals. 2019;9(9):686. doi: 10.3390/ani9090686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jacobson MR, Watts JJ, Boileau I, Tong J, Mizrahi R. A systematic review of phytocannabinoid exposure on the endocannabinoid system: Implications for psychosis. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2019;29(3):330–348. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2018.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hunt DA, Keefe J, Whitehead T, Littlefield A. Understanding cannabis. J. Nurse Practition. 2020;16(9):645–649. doi: 10.1016/j.nurpra.2020.07.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kamal BS, Kamal F, Lantela DE. Cannabis and the anxiety of fragmentation—A systems approach for finding an anxiolytic cannabis chemotype. Front. Neurosci. 2018 doi: 10.3389/fnins.2018.00730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Santiago M, Sachdev S, Arnold JC, McGregor IS, Connor M. Absence of entourage: Terpenoids commonly found in Cannabis sativado not modulate the functional activity of Δ9-thc at human CB1and CB2 receptors. Cannabis Cannabinoid Res. 2019;4(3):165–176. doi: 10.1089/can.2019.0016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Finlay DB, Sircombe KJ, Nimick M, Jones C, Glass M. Terpenoids from cannabis do not mediate an entourage effect by acting at cannabinoid receptors. Front. Pharmacol. 2020 doi: 10.3389/fphar.2020.00359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Morash, M. G., Nixon, J., Shimoda, L. M., Turner, H., Stokes, A. J., Small-Howard, A.L., & Ellis, L. D. Identification of minimum essential therapeutic mixtures from Cannabis plant extracts by screening in cell and animal models of Parkinson’s disease. Manuscript submitted for publication (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 51.Hill M, Gorzalka B. The endocannabinoid system and the treatment of mood and anxiety disorders. CNS Neurological Disord. Drug Targets. 2009;8(6):451–458. doi: 10.2174/187152709789824624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Onaivi ES. Cannabinoid receptors in brain: Pharmacogenetics, neuropharmacology, neurotoxicology, and potential therapeutic applications. New Concepts Psychostimulant Induced Neurotoxicity. 2009;88:335–369. doi: 10.1016/s0074-7742(09)88012-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ashton CH, Moore PB. Endocannabinoid system dysfunction in mood and related disorders. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2011;124(4):250–261. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2011.01687.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Porter AC, Felder CC. The endocannabinoid nervous system. Pharmacol. Ther. 2001;90(1):45–60. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7258(01)00130-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kennedy EK, Perono GA, Nemez DB, Holloway AC, Thomas PJ, Letcher R, Marvin C, Stetefeld J, Stout J, Peters O, Palace V, Tomy G. Increasing cannabis use and importance as an environmental contaminant mixture and associated risks to exposed biota: A review. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2020;52(2):203–239. doi: 10.1080/10643389.2020.1819730. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Al Mansouri S, Ojha S, Al Maamari E, Al Ameri M, Nurulain SM, Bahi A. The cannabinoid receptor 2 agonist, β-caryophyllene, reduced voluntary alcohol intake and attenuated ethanol-induced place preference and sensitivity in mice. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 2014;124:260–268. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2014.06.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lydiard RB. The role of GABA in anxiety disorders. J. Clin. Psychiatry. 2003;3:21–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lisboa SF, Gomes FV, Terzian ALB, Aguiar DC, Moreira FA, Resstel LBM, Guimarães FS. The endocannabinoid system and anxiety. Anxiety. 2017 doi: 10.1016/bs.vh.2016.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Salehi B, Upadhyay S, Erdogan Orhan I, Kumar Jugran A, Jayaweera S, Dias D, Sharifi-Rad J. Therapeutic potential of α- and β-pinene: A miracle gift of nature. Biomolecules. 2019;9(11):738. doi: 10.3390/biom9110738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Anzelius M, Ekström P, Möhler H, Grayson Richards J. Immunocytochemical localization of GABAA receptor-subunits in the brain of Atlantic Salmon (Salmo salar L.) J. Chem. Neuroanat. 1995;8(3):207–221. doi: 10.1016/0891-0618(95)00046-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Anzelius M, Ekström P, Möhler H, Richards JG. Immunocytochemichal localization of the GABAA/benzodiazepine receptor β2/β3 subunits in the optic tectum of the salmon. J. Recept. Signal Transduction. 1995;15(1–4):413–425. doi: 10.3109/10799899509045230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Friedl W, Hebebrand J, Rabe S, Propping P. Phylogenetic conservation of the benzodiazepine binding sites: Pharmacological evidence. Neuropharmacology. 1988;27(2):163–170. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(88)90166-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sackerman J, Donegan JJ, Cunningham CS, Nguyen NN, Lawless K, Long A, Benno RH, Gould GG. Zebrafish behavior in novel environments: Effects of acute exposure to anxiolytic compounds and choice of Danio rerio line. Int. J. Comp. Psychol. 2010;23(1):43–61. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Oltrabella F, Melgoza A, Nguyen B, Guo S. Role of the endocannabinoid system in vertebrates: Emphasis on the zebrafish model. Dev. Growth Differ. 2017;59(4):194–210. doi: 10.1111/dgd.12351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Achenbach JC, Hill J, Hui JPM, Morash MG, Berrue F, Ellis LD. Analysis of the uptake, metabolism, and behavioral effects of cannabinoids on zebrafish larvae. Zebrafish. 2018;15(4):349–360. doi: 10.1089/zeb.2017.1541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Available upon request. Correspondence and requests for materials should be addressed to T.J.H. or A.J. [JohnsonA254@mymacewan.ca]. Analyzed data from Noldus EthoVision XT tracking software is available in the electronic supplementary material.