Abstract

Background

The therapeutic role of azathioprine (AZA) and 6‐mercaptopurine (6‐MP) remains controversial due to their relatively slow onset of action and potential for adverse events. An updated meta‐analysis was performed to evaluate the efficacy of these agents for the maintenance of remission in quiescent Crohn's disease.

Objectives

To assess the efficacy of AZA and 6‐MP for maintenance of remission in quiescent Crohn's disease.

Search methods

We searched MEDLINE, EMBASE, and the Cochrane Library from inception to June 30, 2015.

Selection criteria

Randomized controlled trials of oral azathioprine or 6‐mercaptopurine compared to placebo or active therapy involving adult patients (> 18 years) with quiescent Crohn's disease were considered for inclusion. Patients with surgically‐induced remission were excluded.

Data collection and analysis

At least two authors independently extracted data and assessed study quality using the Cochrane risk of bias tool. For dichotomous outcomes, we calculated the risk ratio (RR) and corresponding 95% confidence interval (CI). The primary outcome was maintenance of remission. Secondary outcomes included steroid sparing, adverse events, withdrawals due to adverse events and serious adverse events. All data were analyzed on an intention‐to‐treat basis. The overall quality of the evidence supporting the primary outcome and selected secondary outcomes was assessed using the GRADE criteria.

Main results

Eleven studies (881 participants) were included. Comparisons included AZA versus placebo (7 studies, 532 participants), AZA or 6‐MP versus mesalazine or sulfasalazine (2 studies, 166 participants), AZA versus budesonide (1 study, 77 participants), AZA and infliximab versus infliximab (1 study, 36 patients), 6‐MP versus methotrexate (1 study, 31 patients), and early AZA versus conventional management (1 study, 147 participants). Two studies were rated as low risk of bias. Four studies were rated as high risk of bias for being non‐blinded or single‐blind. Five studies were rated as unclear risk of bias. A pooled analysis of six studies (489 participants) showed that AZA (1.0 to 2.5 mg/kg/day) was significantly superior to placebo for maintenance of remission over a 6 to 18 month period. Seventy‐three per cent of patients in the AZA group maintained remission compared to 62% of placebo patients (RR 1.19, 95% CI 1.05 to 1.34). The number needed to treat for an additional beneficial outcome was nine. A GRADE analysis indicated that the overall quality of the evidence supporting this outcome was low due to sparse data (327 events) and unclear risk of bias. A pooled analysis of two studies (166 participants) showed no statistically significant difference in the proportion of patients who maintained remission between AZA (1.0 to 2.5 mg/kg/day) or 6‐MP (1.0 mg/day) and mesalazine (3 g/day) or sulphasalazine (0.5 g/15 kg/day) therapy. Sixty‐nine per cent of patients in the AZA/6‐MP group maintained remission compared to 67% of mesalazine/sulphasalazine patients (RR 1.09, 95% CI 0.88 to 1.34). A GRADE analysis indicated that the overall quality of the evidence supporting this outcome was low due to sparse data (113 events) and high or unclear risk of bias. One small study found AZA (2.0 to 2.5 mg/kg/day) to be superior to budesonide (6 to 9 mg/day) for maintenance of remission at one year. Seventy‐six per cent (29/38) of AZA patients maintained remission compared to 46% (18/39) of budesonide patients (RR 1.65, 95% CI 1.13 to 2.42). GRADE indicated that the overall quality of the evidence supporting this outcome was low due to sparse data (47 events) and high risk of bias. One small study found no difference in maintenance of remission rates at one year between combination therapy with AZA (2.5 mg/kg) and infliximab (5 mg/kg every 8 weeks) compared to infliximab monotherapy. Eighty‐one per cent (13/16) of patients in the combination therapy group maintained remission compared to 80% (16/20) of patients in the infliximab group (RR 1.02, 95% CI 0.74 to 1.40). GRADE indicated that the overall quality of the evidence supporting this outcome was very low due to very sparse data (29 events) and high risk of bias. One small study found no difference in maintenance of remission rates at one year between 6‐MP (1 mg/kg/day) and methotrexate (10 mg/week). Fifty per cent (8/16) of 6‐MP patients maintained remission at one year compared to 53% (8/15) of methotrexate patients (RR 0.94, 95% CI 0.47 to 1.85). GRADE indicated that the overall quality of the evidence supporting this outcome was very low due to very sparse data (16 events) and high risk of bias. One study (147 participants) failed to show any significant benefit for early azathioprine treatment over a conventional management strategy. In the early azathioprine treatment group 67% (11‐85%) of trimesters were spent in remission compared to 56% (29‐73%) in the conventional management group. AZA when compared to placebo had a significantly increased risk of adverse events (RR 1.29, 95% CI 1.02 to 1.64), withdrawal due to adverse events (3.12, 95% CI 1.59 to 6.09) and serious adverse events (RR 2.45, 95% CI 1.22 to 4.90). AZA/6‐MP also demonstrated a significantly higher risk of serious adverse events when compared to mesalazine or sulphasalazine (RR 9.37, 95% CI 1.84 to 47.7). Common adverse events included pancreatitis, leukopenia, nausea, allergic reaction and infection.

Authors' conclusions

Low quality evidence suggests that AZA is more effective than placebo for maintenance of remission in Crohn's disease. Although AZA may be effective for maintenance of remission its use is limited by adverse effects. Low quality evidence suggests that AZA may be superior to budesonide for maintenance of remission but because of small study size and high risk of bias, this result should be interpreted with caution. No conclusions can be drawn from the other active comparator studies because of low and very low quality evidence. Adequately powered trials are needed to determine the comparative efficacy and safety of AZA and 6‐MP compared to other active maintenance therapies. Further research is needed to assess the efficacy and safety of the use of AZA with infliximab and other biologics and to determine the optimal management strategy for patients with quiescent Crohn's disease.

Plain language summary

Azathioprine or 6‐mercaptopurine for maintenance of remission in Crohn's disease

What is Crohn's disease? Crohn's disease is a long‐term chronic inflammatory bowel disease that can affect any part of the gastrointestinal tract from mouth to anus. Symptoms include abdominal pain, diarrhea and weight loss. When people with Crohn's disease are experiencing symptoms of the disease it is said to be ‘active’. Periods when the symptoms stop are called ‘remission’.

What are azathioprine and 6‐mercaptopurine? Azathioprine and 6‐mercaptopurine are oral medications that reduce the body's immune responses and may reduce inflammation associated with Crohn's disease.

What did the researchers investigate? The researchers investigated whether azathioprine or 6‐mercaptopurine maintains remission in people with inactive Crohn's disease and whether these medications cause any harms (side effects). The researchers searched the medical literature up to June 30, 2015.

What did the researchers find? The researchers identified 11 studies that included a total of 881 participants. Seven studies including 532 participants compared azathioprine to a placebo (a fake medicine such as a sugar pill). Two studies including 166 participants compared azathioprine or 6‐mercaptopurine to aminosalicylates (the anti‐inflammatory medications mesalazine or sulfasalazine). One study including 77 participants compared azathioprine to budesonide (a steroid drug). One study including 31 participants compared 6‐mercaptopurine to methotrexate (an immunosuppressive drug). One study including 36 participants compared combination therapy with azathioprine and infliximab (a biologic drug) to infliximab alone. One study with 147 participants compared the early use of azathioprine in patients with recently diagnosed Crohn's disease to a conventional management strategy. Two studies were rated as high quality. Three studies were rated as low quality. Six studies were rated as unclear quality due to a lack of information.

A pooled analysis of six studies (489 participants) suggests that azathioprine (at daily doses of 1.0 to 2.5 mg/kg/day) is superior to placebo for maintenance of remission of Crohn's disease over a 6 to 18 month period. A pooled analysis of two studies (166 participants) showed no difference in the proportion of patients who maintained remission between azathioprine (1.0 to 2.5 mg/kg/day) or 6‐mercaptopurine (1.0 mg/day) and aminosalicylate therapy (mesalazine 3 g/day or sulfasalazine 0.5g/15 kg/day). One small study (77 participants) suggests that azathioprine (2.0 to 2.5 mg/kg/day) may be superior to budesonide (6 to 9 mg/day) for maintenance of remission over a one year period. One small study (36 participants) found no difference in maintenance of remission rates at one year between combination therapy with azathioprine (2.5 mg/kg/day) and infliximab (5 mg/kg every 8 weeks) compared to infliximab alone. One small study (31 participants) found no difference in maintenance of remission rates at one year between 6‐mercaptopurine (1 mg/day) and methotrexate (10 mg/week). One study (147 participants) failed to show any difference in time spent in remission between early azathioprine treatment and a conventional management strategy. An increased risk of side effects was seen in participants who received azathioprine. Some of these side effects such as leukopenia (a reduction in the number of white cells in the blood) were serious in nature. Common side effects included pancreatitis (inflammation of the pancreas), leukopenia, nausea, allergic reaction and infection. The choice to use azathioprine or 6‐mercaptopurine should be made after careful consideration of the risks and benefits of using these drugs. More research is needed to allow conclusions about the comparative effectiveness and side effects of azathioprine and 6‐mercaptopurine compared to other maintenance therapies such as methotrexate. Further research is needed to assess the effectiveness and side effects of the use of azathioprine with infliximab and other biologics and to determine the optimal management strategy for patients with inactive Crohn's disease.

Summary of findings

Background

The antimetabolite 6‐mercaptopurine and its prodrug, azathioprine, are purine analogues that inhibit cell growth by directly interfering with nucleic acid synthesis. Because of their ability to impede the rapid cell proliferation involved in inflammatory processes, these drugs have been shown to demonstrate immuno‐suppressive abilities (Sahasranaman 2008).

There have been many uncontrolled studies evaluating the efficacy of azathioprine for the therapy of Crohn's disease, and the first randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled trials were documented in the early 1970's (Rhodes 1970; Willoughby 1971). Although much experience has been gained with these drugs since then, the therapeutic role of azathioprine and 6‐mercaptopurine remains controversial, in part related to their slow acting therapeutic effect as well as their potential for adverse events, such as leukopenia, pancreatitis, nausea, hypersensitivity, and increased risk of malignancy (Gearry 2004).

Crohn's disease is characterized by its propensity to relapse. Therefore studies were designed to determine the efficacy of azathioprine or 6‐mercaptopurine for maintenance of remission. This systematic review is an update of a previously published Cochrane review (Prefontaine 2009).

Objectives

The primary objective was to assess the efficacy and safety of azathioprine or 6‐mercaptopurine maintenance therapy in patients with quiescent Crohn's disease.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomized controlled trials were considered for inclusion.

Types of participants

Patients greater than 18 years of age with quiescent Crohn's disease (as defined by the included studies) were considered for inclusion. Quiescent disease, or disease in remission was defined as mild or absent symptoms prior to entering the study or by a validated index (e.g. CDAI < 150), irrespective of the use of prophylactic medication. Patients with surgically‐induced remission were excluded.

Types of interventions

Studies comparing oral azathioprine or 6‐mercaptopurine to placebo or an active therapy for maintenance of remission in Crohn's disease were included.

Types of outcome measures

Most of the included studies used the Crohn's Disease Activity Index (CDAI) to define remission (Best 1976). Using the CDAI, remission is defined as a score of less than 150. The earlier studies utilized other scales such as the Disease Activity Score (DAS) (Dyer 1970), and other less well defined measures such as maintenance of well being. Despite this diversity in outcome measurement, we felt that these earlier studies provided a reasonable measurement of clinically active and inactive disease.

Primary outcomes

The primary outcome was maintenance of remission (as defined by the included studies, e.g. CDAI < 150) at study endpoint.

Secondary outcomes

Secondary outcomes included:

adverse events

withdrawal due to adverse events;

serious adverse events; and

steroid sparing.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched the following databases from inception to June 30, 2015:

MEDLINE (Ovid);

EMBASE (Ovid);

Cochrane Library.

Conference proceedings were also searched to identify additional studies.

The electronic search strategies are reported in Appendix 1.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Study titles and abstracts identified by the literature search were reviewed and potentially relevant studies were identified for full text evaluation. The studies selected for full text review were independently assessed by two authors (PHP and JKM or DJT or BST) and consensus for study inclusion and exclusion was reached through discussion.

Data extraction and management

Each study was reviewed and remission and safety data were independently extracted by at least two authors (PHP and JKM or DJT or BST). If data were missing or unclear, the study authors were contacted for clarification.

Other information extracted from the studies included:

a. Study characteristics and design; b. Characteristics of patients; c. Inclusion and exclusion criteria; d. Interventions; and e. Outcomes scoring methods.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

At least two authors (PHP or JKM or DST or BST) independently assessed study quality using the Cochrane risk of bias tool (Higgins 2011a). Items assessed included:

Random sequence generation;

Allocation concealment;

Blinding of participants, personnel and assessment of outcome;

Incomplete outcome data;

Selective reporting;

Other biases.

Each category was evaluated as low, high or unclear risk and judgment justification was provided in the Characteristics of included studies section of the review.

GRADE Analysis

The overall quality of the evidence supporting the primary outcome and selected secondary outcomes was evaluated using the GRADE approach (Guyatt 2008; Schünemann 2011). Using this approach outcome data were rated high, moderate, low or very low quality. Outcome data from randomized controlled trials begins as high quality but can be downgraded based on a number of criteria. These criteria include:

Risk of bias in the included studies;

Indirect evidence (by comparison, population, setting);

Inconsistency (i.e. unexplained heterogeneity);

Imprecise results (i.e. wide confidence intervals); and

Likelihood of publication bias.

Measures of treatment effect

For dichotomous outcomes, we calculated the risk ratio (RR) and corresponding 95% confidence interval.

Unit of analysis issues

For multi‐arm trials with a single placebo group and two treatment dose groups we split the placebo group in half to avoid a unit of analysis error (Higgins 2011b). To avoid potential carry‐over effects we only included the first part of the study (i.e. before the cross‐over) for any cross‐over studies (Higgins 2011b).

Dealing with missing data

Data were analysed on an intention‐to‐treat basis. Studies were evaluated for missing data and where explanations were not provided, the patient outcome was considered to be a failure and counted as a relapse.

Assessment of heterogeneity

Statistical heterogeneity was assessed using the Chi2 test and I2 statistic. For the Chi2 test a P value of less than 0.1 was considered to be statistically significant. The degree of statistical heterogeneity was quantified using the I2 statistic. We investigated heterogeneity by visually inspecting the forest plots to identify outliers. If outliers were identified, we conducted sensitivity analysis to explore potential explanations for the heterogeneity.

Assessment of reporting biases

If protocols were not available for the included studies, we assessed reporting bias by comparing the outcomes specified in the methods section of the manuscript to those reported in the results section. If there was more than 10 included studies in a pooled analysis, we planned to investigate publication bias by constructing funnel plots.

Data synthesis

Data from individual trials were combined for meta‐analysis when the interventions, patient groups and outcomes were sufficiently similar (determined by consensus). We calculated the pooled RR and 95% CI for dichotomous outcomes using a fixed‐effect model. If significant heterogeneity was identified a random‐effects model was used. We performed subgroup analyses by dose of azathioprine or 6‐mercaptopurine (i.e. 1.0, 2.0, and 2.5 mg/kg/day). It was deemed acceptable to pool studies of azathioprine with 6‐mercaptopurine studies, as azathioprine is metabolized to 6‐mercaptopurine.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

A literature search conducted on June 30, 2015 identified 1541 studies. After duplicates were removed a total of 1119 studies remained for review of titles and abstracts. Fifty‐seven studies of azathioprine or 6‐mercaptopurine therapy for maintenance of remission in Crohn's were selected for full text review (See Figure 1). Thirty‐five reports of 27 studies were excluded because they did not meet the inclusion criteria. The remaining 22 reports of 11 studies were evaluated for qualitative analysis and 11 studies underwent quantitative analysis.

1.

Study flow diagram.

Included studies

Eleven trials (881 participants) were included (Candy 1995; Cosnes 2013; Lémann 2005; Mantzaris 2004; Mantzaris 2009; Maté‐Jiménez 2000; O'Donoghue 1978; Panes 2013; Rosenberg 1975; Summers 1979; Willoughby 1971). Six of these trials were double‐blind and placebo‐controlled (Candy 1995; Lémann 2005; O'Donoghue 1978; Panes 2013; Rosenberg 1975; Willoughby 1971). Two of these trials were withdrawal studies, where patients who were being maintained in remission by azathioprine were randomized to continue therapy or replace their azathioprine with placebo (O'Donoghue 1978; Lémann 2005). Four trials included an induction phase on the study medication, then followed the patients that achieved remission for the maintenance phase (Candy 1995; Mantzaris 2004; Maté‐Jiménez 2000; Summers 1979). Only one trial studied 6‐mercaptopurine for maintenance of remission (Maté‐Jiménez 2000). Four studies compared azathioprine or 6‐mercaptopurine to an active therapy. Mantzaris 2004 compared combination therapy with azathioprine and infliximab to infliximab. Mantzaris 2009 compared azathioprine to budesonide. Maté‐Jiménez 2000 compared 6‐mercaptopurine to methotrexate and 5‐ASA. Summers 1979 compared azathioprine to sulphasalazine and prednisone. Summers 1979 was the only active comparator study that also included a placebo arm. The Summers 1979 study also known as the National Cooperative Crohn's Disease study contained two parts. Part I had two phases. In phase one, patients with active Crohn's disease were treated with the study drug to induce remission. In phase two, patients who had achieved remission in phase one were followed to see if they maintained remission on 2.5 mg/kg/day of azathioprine. Part II included patients who had quiescent disease and patients were randomized to receive study medication to maintain remission on 1.0 mg/kg/day of azathioprine. This review includes outcome data from part one, phase two and part two. Adverse event data were reported for the entire Summers 1979 study (not by phase). Cosnes 2013 and Panes 2013 evaluated the effect of early administration of azathioprine in patients newly diagnosed with Crohn's disease, and included patients with active disease. Panes 2013 compared azathioprine to placebo. Cosnes 2013 compared early use of azathioprine to conventional management, which could eventually include azathioprine. Both allowed patients to treat flares with steroids and still remain in the study, which was a measure of relapse in all other studies. Two studies included patients aged 15 years old or greater (Candy 1995; Maté‐Jiménez 2000). However the majority of patients in these studies were adults.

Candy 1995 conducted a randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled, trial to assess the efficacy of azathioprine in combination with prednisolone versus placebo in combination with prednisolone for induction and maintenance of remission in 63 patients with active Crohn's Disease (CDAI > 200). Remission was defined as a CDAI score of < 150. Patients (aged 15 to 65 years) were selected from a single site (Groot Schuur Hospital IBD Clinic). Patients were excluded from the study if they had previous surgery for Crohn's disease, symptoms suggestive of mechanical obstruction, recently received immunosuppressives, compromised hepatic function, or if they were pregnant or lactating. After one week of azathioprine 50 mg/day, the dose was held constant at 2.5 mg/kg/day for the remaining 11 weeks of phase 1, and for 12 months of phase 2 (or until the patient relapsed or withdrew from the study). In phase 1, patients (intervention group n = 33 and placebo group n = 30) received a tapering dose of prednisolone (initial dose 1 mg/kg/day tapered to 0 by week 12) in combination with azathioprine or placebo for induction of remission. Twenty out of 63 participants failed to achieve remission (7 in azathioprine group and 9 in placebo group) or withdrew from phase 1. During phase 2, patients (intervention group n = 24 and placebo group n = 19) continued to receive azathioprine or matched placebo for 12 months. The primary outcome was the proportion of patients in clinical remission. Secondary outcomes were median change in CDAI, ESR, serum CRP, serum orosomucoid concentration, and leucocyte count between the first and last visits. Differences in leucocyte count between baseline and final visit were evaluated for responders and non‐responders within the intervention group. Adverse events and compliance were also monitored.

Cosnes 2013 performed a three‐year trial to evaluate the efficacy of early azathioprine treatment within six months of diagnosis versus conventional management of Crohn's disease patients with a high risk of disabling disease. Remission was defined as a trimester spent free of: flare, treatment with steroids or anti‐TNF‐alpha antagonists, active perianal disease (pain or discharge with induration, skin tags, ulceration, fissure or fistula), Crohn's disease‐related hospitalization (including those caused by drug side effects); or surgery. The study was performed at 24 French centres and was a randomized, parallel group, open‐label trial. Patients were at least 18 years of age (N = 147; intervention n= 72); and were classified as high risk if they had been diagnosed when they were under 40 years of age, had received corticosteroids within three months of diagnosis or had active perianal lesions. Patients were excluded if they had previous treatment with immunomodulators or anti–TNF‐alpha therapy; immediate need for surgery or anti‐TNF‐alpha therapy; severe comorbidity; documented infection; renal or liver failure; contraindication to thiopurines according to labelling recommendations; malignancy; history of drug abuse; predictable poor compliance; or if they were pregnant. The primary outcome was the proportion of trimesters spent in remission. The secondary outcomes were the proportion of trimesters in the three year trial period that contain any of the above listed failures of remission; duration of significant corticosteroid exposure per trimester; total exposures (in milligrams) of prednisone and budesonide per trimester; time to first perianal surgery, first intestinal resection, and first anti‐TNF use; median CDAI scores and C‐reactive protein concentrations throughout follow‐up; quality of life (measured by the IBD Questionnaire) at months 12, 24, and 36; total number of days of hospitalization; and total number of days out of work per trimester. Safety data and adverse events were also collected.

Lémann 2005 conducted a randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled trial at 11 French sites and 1 Belgian site. The study evaluated the effectiveness of azathioprine for long term remission of Crohn's disease. Patients were monitored for relapse, (defined as CDAI > 250 or CDAI of 150‐250 on 3 consecutive weeks plus an increase of ≥ 75 points above baseline score, or the need for surgery (except limited perianal surgery)). Patients selected for the study (N = 83, azathioprine group, n = 40) were at least 18 years of age, and had continuous azathioprine treatment for a minimum of 42 months during which they did not experience a flare‐up, receive oral prednisone (>10 mg/day) budesonide or another immunosuppressive or biological agent; ingest artificial nutrition; undergo surgery (except limited perianal surgery). Patients were excluded if they had active disease (CDAI > 150 at entry), disease was limited to the perianal area, or if they had received azathioprine to prevent postoperative recurrence after curative surgical resection. Adverse events were also monitored.

Mantzaris 2004 conducted a randomized, phase II study that evaluated the effectiveness of azathioprine combined with infliximab compared to infliximab monotherapy. Patients (N = 47) were between ages 18 and 57 with active, steroid‐resistant Crohn's disease (CDAI > 150). Patients were ineligible if they had fistulizing or fibrostenotic disease, septic complications, or if they had not received previous treatment with immunomodulators. After a six week induction phase, patients in remission continued their assigned therapies. All patients received either infliximab (5 mg/kg every 8 weeks) or infliximab and azathioprine (2.5 mg/kg/day). The primary outcome was the proportion of patients with maintenance of remission. Adverse effects were also monitored. The study was published as an abstract.

Mantzaris 2009 compared the effectiveness of azathioprine (2 to 2.5 mg/kg/day) to budesonide (6 to 9 mg/day) for maintenance of remission in patients (aged 18‐67 years) with steroid‐dependant Crohn's disease (CDAI < 150) over a one year period, which was extended to 18 months for those maintaining remission at the one year cutoff. Steroid‐dependency was described as individuals having at least one flare in the previous six to twelve months which had been successfully treated with steroids, but returned during steroid tapering or after steroid withdrawal. Included patients had recently flared (within one month of study inclusion) and were receiving a tapered dose of oral prednisolone for at least one month prior to randomization. The primary outcomes were mucosal healing and histological remission. Secondary outcomes included annual relapse rate, time in remission, discontinuation of study medications, changes in CDAI or health‐related quality of life, and safety data. Compliance and the use of any other medications were also monitored.

Maté‐Jiménez 2000 conducted a 106 week, single‐centre, randomized three arm two phase trial with sub‐stratification for ulcerative colitis (n = 34) and Crohn's disease (n = 38). The induction phase was 30 weeks, and was followed by a maintenance phase for 76 weeks to evaluate the efficacy of adding either 6‐mercaptopurine, methotrexate or 5‐aminosalicylic acid to prednisone to induce remission (phase one) and then maintain remission without prednisone (phase two). Patients selected for inclusion (N = 72) were aged 15 to 70 years with steroid‐dependent, radiologically or endoscopically confirmed inflammatory bowel disease from Digestive DIseases Service, Hospital de la Princesa, who had been followed for at least one year and had never previously received either 6‐mercaptopurine or methotrexate. Steroid dependence was defined as patients who could not be weaned off less than 20 mg prednisone without induction of inflammatory activity, and a CDAI > 200. Exclusion criteria included: patients over the age of 70 years or under the age of 15 years; no signed consent; those with clinically significant cardiac, hepatic or renal disease; ongoing bacterial infection; pregnancy; lactating or not using reliable contraceptive techniques; patients using concomitant allopurinol, NSAIDs, tetracyclines or phenytoin in significant doses; those who have had extensive surgery for their Crohn's disease; or those who have symptoms that suggest a potential need for urgent surgery. The induction phase used the individualized dose of prednisone used prior to study inclusion as the starting dose (highest was 1 mg/kg/day prednisone) to be tapered by 8 mg/kg/day prednisone over the 30 weeks to 0 and the following therapies under study, 6‐mercaptopurine 1.5mg/kg/day (group A, n = 16 with Crohn's), methotrexate, 15 mg/week (group B, n = 15 with Crohn's) or 5‐aminosalicyclic acid, 3 g/day (group C, n = 7 with Crohn's). For the maintenance phase, only those who achieved remission after stopping prednisone during the induction phase were included in this portion of the study. In these patients the methotrexate dose was reduced to 10 mg/week and the 6‐mercaptopurine dose reduced to 1 mg/kg/day. The 5‐aminosalicylic acid dose used for maintenance therapy did not change (3g/day). No other medications, except antidiarrhoeals and supplements, were allowed. The primary outcome for phase one was induction of remission and cessation of steroids, while phase 2 was clinical remission. "Relapse was defined as CDAI > 150 and orosomucoid > 100 (N 88 mg/dl) with no response to 6 g daily of 5‐aminosalicylic acid and with need of prednisone therapy in Crohn's disease patients." Adverse events were a secondary outcome.

O'Donoghue 1978 performed a randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled, 52 week, withdrawal study, which initially sub‐stratified participants into those only on azathioprine and those also on other anti‐inflammatories and azathioprine. The study evaluated the efficacy of azathioprine for maintenance of remission, defined as preventing relapse ("significant deterioration in clinical state requiring a change in treatment as judged by two doctors unaware of the patient's treatment"), in patients (N = 51) with quiescent Crohn's disease taking azathioprine (2 mg/kg/day) for at least six months prior to study inclusion. Patients receiving azathioprine combined with sulphasalazine or low dose corticosteroids were included; this treatment remained unchanged throughout study period. Patients were also allowed medications for symptom control and supplements. Patients were monitored for primary outcomes using a modified DAS scoring system completed at each clinical assessment. Adverse events and serious adverse events were also monitored; one patient died during the study.

Panes 2013 conducted a randomized, multi‐centre, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled study over 76 weeks in 31 Spanish hospitals. The study evaluated the efficacy of early administration of azathioprine (2.5 mg/kg/day) in patients with newly diagnosed (< 8 weeks) Crohn's disease for maintenance of corticosteroid‐free clinical remission. Sustained corticosteroid‐free remission was defined as the presence of clinical remission (CDAI score < 150 at each visit) in patients who had not been treated with corticosteroids during the entire study or patients who were treated with corticosteroids at baseline after the scheduled weaning of this treatment. Patients (N= 131; azathioprine, n = 68) aged 18 to 70 years, diagnosed with established Crohn's disease criteria within 8 weeks of screening, "irrespective of disease activity and use of corticosteroids at the time of screening." Exclusion criteria included previous treatment with azathioprine, 6‐mercaptopurine, methotrexate, cyclosporin, tacrolimus, mycophenolate mofetil, infliximab or adalimumab; patients with an immediate need for surgery or patients who had surgery for Crohn's disease; penetrating disease, symptomatic stenosis, perianal fistulas; patients with severe co‐morbidities, documented infection, malignancy, history of drug use; or those who were pregnant. Corticosteroids were allowed to treat flares during the study, (prednisone doses ranged 1 mg/kg/day to a maximum of 60 mg/day; budesonide dosage 9 mg/day), but were tapered using a predetermined schedule. No other medications used to treat Crohn's disease were allowed, except antibiotics for suspected or demonstrated infection. Secondary outcomes included relapse‐free survival, mean CDAI and IBDQ scores, and CRP concentrations at each visit; requirement for corticosteroids; cumulative dose of corticosteroids; development of a fistula; hospitalization; and CD‐related surgery and cumulative prednisone dose. Safety data were also collected.

Rosenberg 1975 conducted a randomized, double‐blind, identically matched placebo‐controlled trial over 26 weeks that evaluated the effect of azathioprine (2.0 mg/kg/day) on reducing the need for steroids in patients > 16 years of age with Crohn's disease who required daily prednisone (minimum dose 10 mg) for symptom control for at least 12 weeks prior to study inclusion (N = 20). Patients were excluded if they had advanced hepatic or renal disease, wished to become pregnant within the study time frame, or were likely to require surgery. The primary outcome was a reduction of prednisone usage over the trial. Prednisone was tapered according to a predetermined schedule when the patient met all of the following criteria: "3 or fewer bowel movements a day, absent to mild pain and malaise, weight loss less than 2 kg, and fever (> 37.5ºC) less than one fourth of the time". Prednisone was increased by 10 mg/day if a patient had > 6 bowel movements per day, severe pain or malaise, > 3 kg weight loss or fever (> 37.5ºC) for greater than half the time over seven days. If the patients condition did not change, the prednisone dosage remained constant. Patients were allowed to continue any other medications prescribed prior to study inclusion. Safety data were also collected.

Summers 1979 conducted two independent trials at the same time to evaluate the efficacy of sulphasalazine, prednisone, and azathioprine against placebo for inducing and maintaining remission in patients with active Crohn's disease (CDAI > 150 with radiologic findings of disease, Part 1, phase 1 and 2) and at maintaining remission in patients already in remission (either medically‐ or surgically‐induced) (Part 2). The studies were randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled trials with patients from 14 centres. Part one was a two phase study, with the first phase (N = 295, placebo n = 77; sulphasalazine n = 74; prednisone n = 85; azathioprine n = 59) inducing remission over 17 weeks using the following identically matched medications and placebo: prednisone: 0.25 mg/kg/day if CDAI < 150; 0.5 mg/kg/day if CDAI = 150 to 300; 0.75 mg/kg/day if CDAI > 300; sulphasalazine: 1 g/15 kg/day; azathioprine: 2.5 mg/kg/day, or placebo. Patients who achieved remission in phase one entered phase two for one to two years of maintenance treatment. These 86 patients included 20 in the placebo group, 19 in the sulphasalazine group, 28 in the prednisone group and 19 in the azathioprine group. Part 2 evaluated maintenance of remission in 226 patients who achieved clinical remission in the previous 2 years or 48 who had undergone complete surgical resection of all diseased bowel within a year of entry. Part 2 included 274 patients: 101 received placebo, 58 received sulphasalazine, 61 received placebo and 54 received azathioprine. Both studies were also sub‐stratified by disease sites, prior steroid usage and disease activity. Safety data were collected throughout both phases.

Willoughby 1971 performed a 22 patient, randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled study to evaluate the effect that azathioprine has on maintaining remission of Crohn's disease once it has been induced by prednisolone alone or combined with azathioprine. This was completed using two groups of patients, randomizing each to azathioprine or placebo. Group 1 (n = 12, azathioprine n = 6) consisted of patients with first time attacks or relapses of moderate to severe severity not treated with steroids in the previous 3 months, while group 2 (n= 10, azathioprine n =5) studied outpatients maintained on long term prednisolone (7.5 to 15 mg/day) for 5 to 72 months. The first group received prednisolone (initial dose 60 mg/day) until remission was achieved; it was then tapered on a 3‐week schedule to 10 mg and discontinued after hospital discharge if remission was maintained. Azathioprine was prescribed at 4.0 mg/kg/day for the first 10 days and then at 2.0 mg/kg/day until the end of 24 weeks. The second group received 2.0 mg/kg/day azathioprine or placebo and maintained their pre‐study dose of prednisolone for "at least 4 weeks after prednisolone was reduced as for group 1." Participants were also prescribed prochlorperazine for nausea and codeine phosphate was continued if the patient received it prior to study entry. Disease activity was monitored using DAS and relapse was considered the return of previous symptoms.

Excluded studies

Twenty‐seven studies were excluded for various reasons. Nine studies were excluded because they evaluated post‐operative maintenance of remission (Abdelli 2007; Ardizzone 2004; Armuzzi 2013; D'Haens 2008b; Hanauer 2004a; Herfarth 2006; Nos 2000; Reinisch 2010; Savarino 2013). Six studies were excluded because they were not randomized controlled trials (Abdelli 2007; Chebli 2007; Korelitz 1998; Mantzaris 2007; Nos 2000; Treton 2009). Six studies were excluded because the patients had active disease (Colombel 2010; de Souza 2013; Klein 1974; Oren 1997; Present 1980; Reinisch 2008). Three studies were excluded because all of the patients received azathioprine (D'Haens 2008a; Lémann 2006; Manosa 2013). Rhodes 1971 was excluded as it was a cross‐over study that failed to provide analysis before the first cross‐over. Another study did not specify the type of immunosuppressant that was studied (van Assche 2008). Vilien 2004 was excluded because the control group did not receive any treatment. The Watson 1979 study was a randomized, double‐blind placebo‐controlled cross‐over study of azathioprine maintenance therapy which was never published as a full paper. Willoughby 1990 was a randomized trial comparing azathioprine with levamisole. This study did not report any of our pre‐specified outcome variables.

Excluded studies and justification for exclusion are reported in the Characteristics of excluded studies tables.

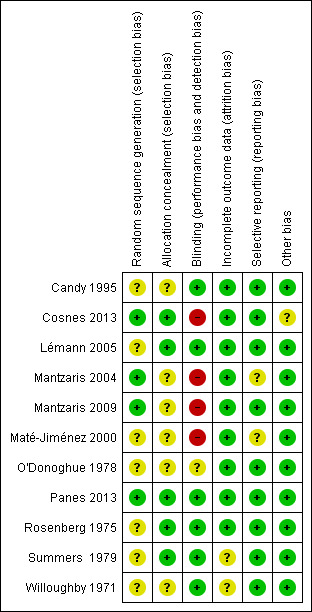

Risk of bias in included studies

The risk of bias for included studies in summarized Figure 2.

2.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

The method of randomization was described in four studies (Cosnes 2013; Mantzaris 2004; Mantzaris 2009; Panes 2013), which received a low risk of bias assessment. The remainder of the studies were judged to have an unclear risk of bias for this item. The methods used for allocation concealment were adequately described in six studies (Cosnes 2013; Lémann 2005; Mantzaris 2004; Panes 2013; Rosenberg 1975; Summers 1979). The other six studies were assessed as having an unclear risk of bias with regard to allocation concealment.

Blinding

Six studies described adequate methods for blinding, including who was blinded and how blinding was maintained and these studies were rated as low risk of bias for blinding (Candy 1995; Lémann 2005; Panes 2013; Rosenberg 1975; Summers 1979; Willoughby 1971). Three of the trials were open label (Cosnes 2013; Mantzaris 2009; Maté‐Jiménez 2000), and thus rated as high risk of bias for blinding. Mantzaris 2004 was single‐blind. All assessors were blind to treatment assignment. O'Donoghue 1978 did not describe blinding.

Incomplete outcome data

As a result of some missing data being only vaguely justified or not discussed two studies received an unclear risk of bias assessment for incomplete outcome data (Summers 1979; Willoughby 1971), while the remaining studies were determined to be a low risk for attrition bias.

Selective reporting

One study performed post hoc analyses that were not described in the methods section and this study was rated as unclear risk of bias for selective reporting (Maté‐Jiménez 2000). Panes 2013 reported on all pre‐specified primary and secondary outcomes and a post hoc analysis. However, the authors clearly indicated that they were reporting a post hoc analysis so we rated the study as low risk of bias for selective reporting. Mantzaris 2004 was given an unclear risk of bias assessment as it was an abstract and did not describe all outcomes in the methods section and no protocol could be located. All of the other studies received a low risk of bias assessment for selective reporting.

Other potential sources of bias

All studies were deemed to be at low risk of bias for other potential sources of bias, except Cosnes 2013, which received a unclear risk because this study included patients who had active disease and could change medications from the study medications to secondary study medications, but these changes were not described.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1; Table 2; Table 3; Table 4; Table 5

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Azathioprine or 6‐mercaptopurine versus placebo for maintenance of remission in Crohn's disease.

| Azathioprine or 6‐mercaptopurine versus placebo for maintenance of remission in Crohn's disease | ||||||

| Patient or population: maintenance of remission in Crohn's disease Setting: Outpatient Intervention: Azathioprine or 6‐mercaptopurine Comparison: Placebo | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with placebo | Risk with azathioprine or 6‐mercaptopurine | |||||

| Maintenance of remission (sensitivity analysis excluding Candy 1995) | 617 per 10001 | 734 per 1000 (648 to 827) | RR 1.19 (1.05 to 1.34) | 489 (6 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW2,3 | |

| Adverse events | 249 per 10001 | 321 per 1000 (254 to 408) | RR 1.29 (1.02 to 1.64) | 359 (6 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW3,4 | |

| Withdrawals due to adverse events | 25 per 10001 | 78 per 1000 (40 to 152) | RR 3.12 (1.59 to 6.09) | 661 (7 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW3,5 | |

| Serious adverse events | 29 per 10001 | 71 per 1000 (35 to 142) | RR 2.45 (1.22 to 4.90) | 556 (4 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ VERY LOW6,7 | |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate quality: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low quality: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low quality: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

1 Placebo group risk estimate come from the placebo arm of meta‐analysis, based on included trials 2 Downgraded one level due to sparse data (327 events). 3 Downgraded one level due to unclear risk of bias. Five of the studies in the pooled analysis were rated as unclear risk of bias for random sequence generation, allocation concealment or incomplete outcome data. 4 Downgraded one level due to sparse data (104 events). 5 Downgraded two levels due to very sparse data (37 events). 6 Downgraded one level due to unclear risk of bias. Two of the studies in the pooled analysis were rated as unclear risk of bias for random sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding or incomplete outcome data. 7 Downgraded two levels due to very sparse data (31 events).

Summary of findings 2. Azathioprine or 6‐mercaptopurine versus mesalazine or sulfasalazine for maintenance of remission in Crohn's disease.

| Azathioprine or 6‐mercaptopurine versus mesalazine or sulfasalazinefor maintenance of remission in Crohn's disease | ||||||

| Patient or population: maintenance of remission in Crohn's disease Setting: Outpatient Intervention: Azathioprine or 6‐mercaptopurine Comparison: Mesalazine or sulfasalazine | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with mesalazine or sulfasalazine | Risk with azathioprine or 6‐mercaptopurine | |||||

| Maintenance of remission | 667 per 10001 | 727 per 1000 (587 to 894) | RR 1.09 (0.88 to 1.34) | 166 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW2,3 | |

| Adverse events | 0 per 10001 | 0 per 1000 (0 to 0) | RR 8.77 (0.54 to 142.51) | 45 (1 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW4,5 | |

| Withdrawals due to adverse events | 68 per 10001 | 126 per 1000 (59 to 270) | RR 1.86 (0.87 to 3.97) | 290 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW2,6 | |

| Serious adverse events | 0 per 10001 | 0 per 1000 (0 to 0) | RR 9.37 (1.84 to 47.72) | 235 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW2,7 | |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate quality: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low quality: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low quality: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

1 Control group risk estimate come from the control arm of meta‐analysis, based on included trials 2 Downgraded one level due to unclear and high risk of bias. One study was rated as unclear risk of bias for random sequence generation and incomplete outcome data and the other study was rated as high risk of bias for no blinding. 3 Downgraded one level due to sparse data (113 events). 4 Downgraded one level due to high risk of bias. 5 Downgraded two levels due to very sparse data (8 events). 6 Downgraded two levels due to very sparse data (28 events). 7 Downgraded two levels due to very sparse data (16 events).

Summary of findings 3. Azathioprine versus budesonide for maintenance of remission in Crohn's disease.

| Azathioprine versus budesonide for maintenance of remission in Crohn's disease | ||||||

|

Patient or population: maintenance of remission in Crohn's disease Setting: Outpatient Intervention: Azathioprine Comparison: Budesonide | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with budesonide | Risk with azathioprine | |||||

| Maintenance of remission | 462 per 10001 | 762 per 1000 (522 to 1000) | RR 1.65 (1.13 to 2.42) | 77 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW2,3 | |

| Withdrawals due to adverse events | 0 per 10001 | 0 per 1000 (0 to 0) | RR 5.13 (0.25 to 103.43) | 77 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW2,4 | |

| Serious adverse events | 0 per 10001 | 0 per 1000 (0 to 0) | RR 5.13 (0.25 to 103.43) | 77 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW2,4 | |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate quality: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low quality: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low quality: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

1 Control group risk estimate come from the control arm of meta‐analysis, based on included trials 2 Downgraded one level due to high risk of bias (no blinding). 3 Downgraded one level due to sparse data (47 events). 4 Downgraded two levels due to very sparse data (2 events).

Summary of findings 4. Azathioprine and infliximab versus infliximab for maintenance of remission in Crohn's disease.

| Azathioprine and infliximab versus infliximab for maintenance of remission in Crohn's disease | ||||||

| Patient or population: maintenance of remission in Crohn's disease Setting: Outpatient Intervention: Azathioprine Comparison: Infliximab | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with infliximab |

Risk with azathioprine + infliximab |

|||||

| Maintenance of remission | 800 per 10001 | 816 per 1000 (592 to 1000) | RR 1.02 (0.74 to 1.40) | 36 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW2,3 | |

| Adverse events | 100 per 10001 | 160 per 1000 (33 to 786) | RR 1.60 (0.33 to 7.86) | 45 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW2,4 | |

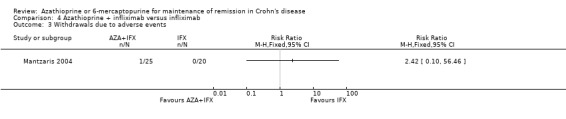

| Withdrawals due to adverse events | 0 per 10001 | 0 per 1000 (0 to 0) | RR 2.42 (0.10 to 56.46) | 45 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW2,5 | |

| Serious adverse events | 0 per 10001 | 0 per 1000 (0 to 0) | RR 2.42 (0.10 to 56.46) | 45 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW2,5 | |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; OR: Odds ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate quality: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low quality: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low quality: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

1 Control group risk estimate come from the control arm of meta‐analysis, based on included trials. 2 Downgraded one level due to high risk of bias (single‐blind). 3 Downgraded two levels due to very sparse data (29 events). 4 Downgraded two levels due to very sparse data (6 events). 5 Downgraded two levels due to very sparse data (1 event).

Summary of findings 5. 6‐Mercaptopurine versus methotrexate for maintenance of remission in Crohn's disease.

| 6‐Mercaptopurine versus methotrexate for maintenance of remission in Crohn's disease | ||||||

| Patient or population: maintenance of remission in Crohn's disease Setting: Outpatient Intervention: 6‐mercaptopurine Comparison: Methotrexate | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with methotrexate | Risk with 6‐mercaptopurine | |||||

| Maintenance of remission | 533 per 10001 | 501 per 1000 (251 to 987) | RR 0.94 (0.47 to 1.85) | 31 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW2,3 | |

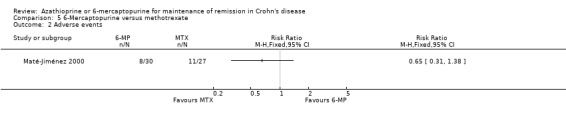

| Adverse events | 407 per 10001 | 265 per 1000 (126 to 562) | RR 0.65 (0.31 to 1.38) | 57 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW2,4 | |

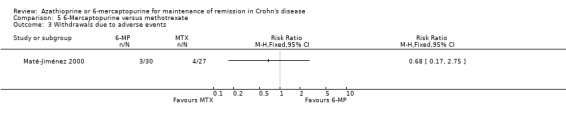

| Withdrawals due to adverse events | 148 per 10001 | 101 per 1000 (25 to 407) | RR 0.68 (0.17 to 2.75) | 57 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW2,5 | |

| Serious adverse events | 148 per 10001 | 101 per 1000 (25 to 407) | RR 0.68 (0.17 to 2.75) | 57 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW2,5 | |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; OR: Odds ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate quality: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low quality: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low quality: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

1 Control group risk estimate come from the control arm of meta‐analysis, based on included trials. 2 Downgraded one level due to high risk of bias (no blinding). 3 Downgraded two levels due to very sparse data (16 events). 4 Downgraded two levels due to very sparse data (19 events). 5 Downgraded two levels due to very sparse data (7 events).

Maintenance of remission

Azathioprine versus placebo

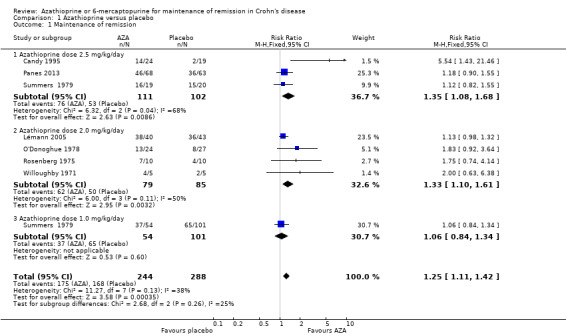

Azathioprine was compared to placebo in seven studies (Candy 1995; Lémann 2005; O'Donoghue 1978; Panes 2013; Rosenberg 1975; Summers 1979; Willoughby 1971). Two of the studies included an induction phase prior to the maintenance phase; as per protocol in the studies, only the patients entering remission in the induction phase were included in the maintenance phase (Candy 1995; Summers 1979 Part 1). The pooled analysis contains data from the maintenance phase of these two studies. The pooled analysis contains subgroups based on azathioprine doses used in the various studious; 2.5 mg/kg/day (Candy 1995; Panes 2013; Summers 1979 Part 1), 2.0 mg/kg/day (Lémann 2005; O'Donoghue 1978; Rosenberg 1975; Willoughby 1971) and 1.0 mg/kg/day (Summers 1979 Part 2). In total, 532 patients were included in the pooled analysis. There was a statistically significant difference in the proportion of patients who maintained remission over 6 to 18 months favouring azathioprine over placebo. Seventy‐two per cent (175/244) of azathioprine patients were in remission at study endpoint compared to 58% (168/288) of placebo patients (RR 1.25, 95% CI 1.11 to 1.42). These studies were moderately heterogeneous (I² = 38%). We visually inspected the forest plot and one study appeared to be an outlier (Candy 1995). Further evaluation of the study characteristics showed that Candy 1995 used a CDAI of less than 175 as criteria for remission, which was different from all the other studies using CDAI. A sensitivity analysis excluding Candy 1995 appears to explain the heterogeneity. The pooled analysis included six studies and 489 participants and there was a statistically significant difference in the proportion of patients who maintained remission over 6 to 18 months favouring azathioprine over placebo. Seventy‐three per cent (161/220) of azathioprine remained in remission at study endpoint compared to 62% (166/269) of placebo patients (RR 1.19, 95% CI 1.05 to 1.34; I2 = 0%). The number needed to treat for an additional beneficial outcome was 9. A GRADE analysis indicated that the overall quality of the evidence supporting this outcome was low due to sparse data (327 events) and an unclear risk of bias in 5 of the studies in the pooled analysis. The pooled analysis for the 2.0 mg/kg/day subgroup showed a statistically significant difference favouring azathioprine over placebo (RR 1.33, 95% CI 1.10 to 1.61). There were no statistically significant differences between azathioprine and placebo for the 2.5 mg/kg/day (RR 1.17, 95% CI 0.94 to 1.45) or 1.0 mg/kg/day (RR 1.06, 95% CI 0.84 to 1.34) subgroups.

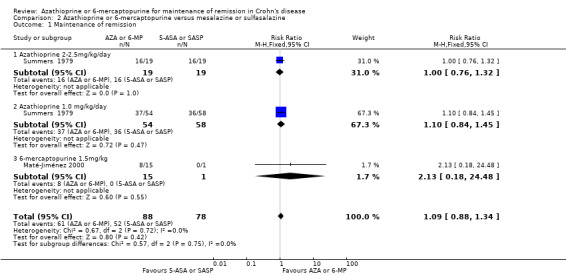

Azathioprine or 6‐mercaptopurine versus mesalazine or sulfasalazine

Maté‐Jiménez 2000 and Summers 1979 (Part 1, phase 2 and Part 2) compared azathioprine or 6‐mercaptopurine to mesalazine or sulfasalazine. A pooled analysis of these studies included 166 patients. Subgroups are reported for the various doses of azathioprine and 6‐mercaptopurine: azathioprine 2 to 2.5 mg/kg/day, azathioprine 1.0 mg/kg/day and 6‐mercaptopurine 50 mg/day. There was no statistically significant difference in the proportion of patients who maintained remission at 12 months. Sixty‐nine percent (61/88) of participants maintained remission on azathioprine or 6‐mercaptopurine compared to 67% (52/78) who maintained remission on mesalamine or sulfasalazine (RR 1.09, 95% CI 0.88 to 1.34). The studies were not found to be heterogeneous (P = 0.72; I² = 0%). A GRADE analysis indicated that the overall quality of the evidence supporting this outcome was low due to sparse data (113 events) and risk of bias. The risk of bias in the Maté‐Jiménez 2000 study was high and the risk of bias in the Summers 1979 study was unclear.

Azathioprine versus budesonide

Azathioprine was compared to budesonide in one small study (Mantzaris 2009). There was a statistically significant difference in the proportion of patients who maintained remission at 12 months favouring azathioprine over budesonide. Seventy‐six per cent (29/38) of patients in the azathioprine group maintained remission compared to 46% (18/39) of budesonide patients (RR 1.65, 95% CI 1.13 to 2.42). A GRADE analysis indicated that the overall quality of the evidence supporting this outcome was low due to sparse data (47 events) and high risk of bias.

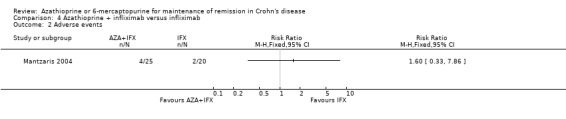

Azathioprine + infliximab versus infliximab

One small study compared combination therapy with infliximab and azathioprine to infliximab monotherapy. There was no statistically significant difference in the proportion of patients who maintained remission at 12 months. Eighty‐one per cent (13/16) of patients in the combination therapy group maintained remission compared to 80% (16/20) of patients in the infliximab monotherapy group (RR 1.02, 95% CI 0.74 to 1.40). A GRADE analysis indicated that the overall quality of the evidence supporting this outcome was very low due to very sparse data (29 events) and high risk of bias.

6‐Mercaptopurine versus methotrexate

Maté‐Jiménez 2000 compared 6‐mercaptopurine to methotrexate. There was no statistically significant difference in the proportion of patients who maintained remission at 76 weeks. Fifty per cent (8/16) of patients in the 6‐mercaptopurine group maintained remission at 76 weeks compared to 53% (8/15) of methotrexate patients (RR 0.94, 95% CI 0.47 to 1.85). A GRADE analysis indicated that the overall quality of the evidence supporting this outcome was very low due to very sparse data (16 events) and high risk of bias.

Early administration of azathioprine versus conventional management

One study (N = 147 participants) compared the early administration of azathioprine to a conventional management strategy (Cosnes 2013). The study failed to show any significant benefit for early azathioprine treatment over a conventional management strategy. In the early azathioprine treatment group 67% (11‐85%) of trimesters were spent in remission compared to 56% (29‐73%) in the conventional management group.

Adverse events

Azathioprine or 6‐mercaptopurine versus placebo

Safety data were reported in each of the seven studies that compared azathioprine to placebo. Three of the seven studies include data for adverse events, withdrawals due to adverse events and serious adverse events (Lémann 2005; O'Donoghue 1978; Panes 2013). Summers 1979 didn't report on the proportion of patients who experienced at least one adverse event. Three studies did not report on serious adverse events (Candy 1995; Rosenberg 1975; Willoughby 1971). The studies including an induction phase (Candy 1995; Summers 1979), did not describe safety data by trial phase and it is unknown whether the adverse events occurred during the induction or maintenance phase. Similarly, Willoughby 1971, did not separate the reported toxicity data by group, and instead reported it across all study participants. For these studies we report the safety data that were available.

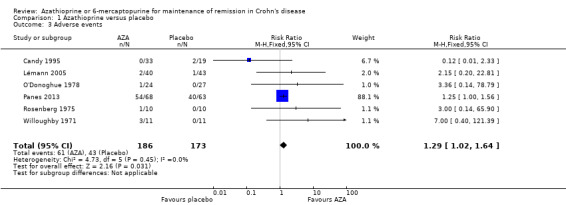

A pooled analysis of six studies (359 participants) showed that a significantly higher proportion of azathioprine patients experienced at least one adverse event compared to placebo (Candy 1995; Lémann 2005; O'Donoghue 1978; Panes 2013; Rosenberg 1975; Willoughby 1971). Thirty‐three per cent of azathioprine patients experienced at least one adverse event compared to 25% of placebo patients (RR 1.29, 95% CI 1.02 to 1.64). A GRADE analysis indicated that the overall quality of the evidence supporting this outcome was low due to sparse data (104 events) and unclear risk of bias. Five of the studies in the pooled analysis were rated as unclear risk of bias for random sequence generation, allocation concealment or incomplete outcome data.

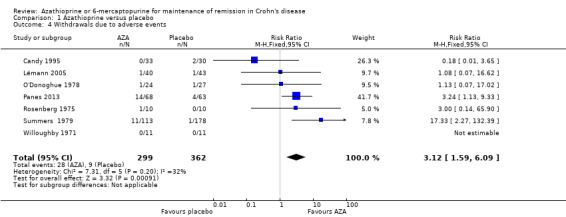

A pooled analysis of seven studies (661 participants) showed that a significantly higher proportion of azathioprine patients withdrew due to adverse events compared to placebo (Candy 1995; Lémann 2005; O'Donoghue 1978; Panes 2013; Rosenberg 1975; Summers 1979; Willoughby 1971). Nine per cent (28/299) of azathioprine patients withdrew due to adverse events compared to 2% (9/362) of placebo patients (RR 3.12, 95% CI 1.59 to 6.09). A GRADE analysis indicated that the overall quality of the evidence supporting this outcome was very low due to very sparse data (37 events) and unclear risk of bias. Five of the studies in the pooled analysis were rated as unclear risk of bias for random sequence generation, allocation concealment or incomplete outcome data. Common adverse events leading to withdrawal included pancreatitis, leukopenia, nausea, allergic reaction and infection. In a few patients, the adverse event causing withdrawal was not specified.

A pooled analysis of four studies (556 patients) showed that a significantly higher proportion of azathioprine patients experienced a serious adverse event compared to placebo (Lémann 2005; O'Donoghue 1978; Panes 2013; Summers 1979). Nine per cent (22/245) of azathioprine patients experienced a serious adverse event compared to 3% (9/311) of placebo patients (RR 2.45, 95% CI 1.22 to 4.90). A GRADE analysis indicated that the overall quality of the evidence supporting this outcome was very low due to very sparse data (31 events) and unclear risk of bias.Two of the studies in the pooled analysis were rated as unclear risk of bias for random sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding or incomplete outcome data. The most common serious adverse event was leukopenia.

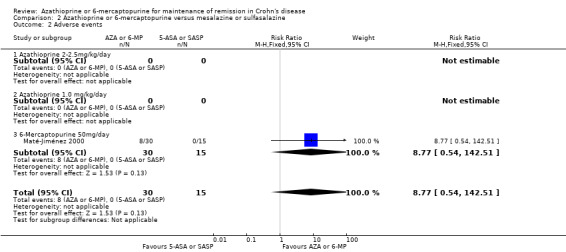

Azathioprine or 6‐mercaptopurine versus mesalazine or sulfasalazine

Maté‐Jiménez 2000 found no statistically significant difference in the proportion of patients who experienced at least one adverse event. Twenty‐seven per cent (8/30) of 6‐mercaptopurine patients experienced at least one adverse event compared to 0% (0/15) of mesalazine patients (RR 8.77, 95% CI 0.54 to 142.51). A GRADE analysis indicated that the overall quality of the evidence supporting this outcome was very low due to very sparse data (8 events) and high risk of bias. The most common adverse events experienced in the 6‐mercaptopurine group were leukopenia, nausea and diarrhoea, melanosis and mild alopecia, with leukopenia being a serious event.

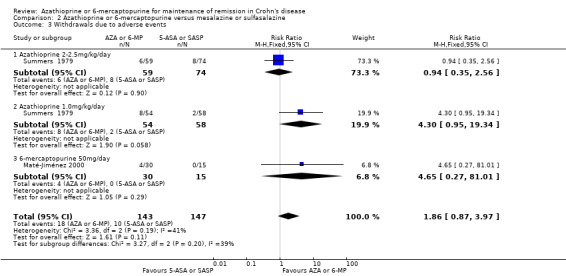

A pooled analysis of two studies (290 participants) showed no statistically significant difference in withdrawals due to adverse events (Maté‐Jiménez 2000; Summers 1979). Thirteen per cent (18/143) of patients in the azathioprine/6‐mercaptopurine group withdrew due to an adverse event compared to 7% (10/147) of patients in the mesalazine/sulfasalazine group (RR 1.86, 95% CI 0.87 to 3.97). A GRADE analysis indicated that the overall quality of the evidence supporting this outcome was very low due to very sparse data (28 events) and unclear or high risk of bias. One study was rated as unclear risk of bias for random sequence generation and incomplete outcome data and the other study was rated as high risk of bias for no blinding.

A pooled analysis of two studies (235 participants) showed a statistically significant difference in the proportion of patients who experienced a serious adverse event (Maté‐Jiménez 2000; Summers 1979). Thirteen per cent (16/125) of patients in the azathioprine/6‐mercaptopurine group had a serious adverse event compared to 0% (0/110) of patients in the mesalazine/sulfasalazine group (RR 9.37, 95% CI 1.84 to 47.72). A GRADE analysis indicated that the overall quality of the evidence supporting this outcome was very low due to very sparse data (16 events) and unclear or high risk of bias. One study was rated as unclear risk of bias for random sequence generation and incomplete outcome data and the other study was rated as high risk of bias for no blinding.

Azathioprine versus budesonide

Mantzaris 2009 reported that 112 adverse events occurred in the 38 patients receiving azathioprine compared to 83 adverse events among the 39 patients in the budesonide group. The proportion of patients in each group who experienced at least one adverse event was not reported. Adverse events included pancreatitis, severe leukopenia, infections, transient abdominal pain, and diarrhea. Adverse events thought to be drug‐related included transient paresthesias, hair loss, and elevated transaminases in the azathioprine group and mild acne, moon face, and transient hair loss in the budesonide group. There was no statistically significant difference in the proportion of patients who withdrew due to adverse events. Five per cent (2/38) of azathioprine patients withdrew due to adverse events compared to 0% (0/39) of budesonide patients (RR 5.13, 95% CI 0.25 to 103.43). A GRADE analysis indicated that the overall quality of the evidence supporting this outcome was very low due to very sparse data (2 events) and high risk of bias. The reported withdrawals were due to serious adverse events including pancreatitis and severe leukopenia. There was no statistically significant difference in the proportion of patients who experienced a serious adverse event (RR 5.13, 95% CI 0.25 to 103.43). A GRADE analysis indicated that the overall quality of the evidence supporting this outcome was very low due to very sparse data (2 events) and high risk of bias.

Azathioprine + infliximab versus infliximab

Mantzaris 2004 reported that there was no statistically significant difference in the proportion of patients who experienced at least one adverse event. Sixteen per cent (4/25) of patients in the combination therapy group experienced at least one adverse event compared to 10% (2/20) of patients in the infliximab monotherapy group (RR 1.60, 95% CI 0.33 to 7.86). A GRADE analysis indicated that the overall quality of the evidence supporting this outcome was very low due to very sparse data (6 events) and unclear risk of bias. In the combination therapy group four patients had leukopenia, which was serious in one patient. In the infliximab monotherapy group two patients had acute infusion reactions. The only withdrawal due to an adverse event occurred in the combination therapy group (severe leukopenia also classified as a serious adverse event). There was no statistically significant difference in the proportion of patients who withdrew due to an adverse event or who experienced a serious adverse event (RR 2.42, 95% CI 0.10 to 56.46). GRADE analyses indicated that the overall quality of the evidence supporting these outcomes was very low due to very sparse data (1 event for both comparisons) and unclear risk of bias.

6‐Mercaptopurine versus methotrexate

Maté‐Jiménez 2000 reported no statistically significant differences in the proportion of patients who experienced at least one adverse event. Twenty‐seven per cent (8/30) of 6‐mercaptopurine patients experienced at least one adverse event compared to 41% (11/27) of methotrexate patients (RR 0.65, 95% CI 0.31 to 1.38). A GRADE analysis indicated that the overall quality of the evidence supporting this outcome was very low due to very sparse data (19 events) and high risk of bias. Adverse events reported in the 6‐mercaptopurine group included leukopenia, nausea and diarrhoea, melanosis and mild alopecia, with leukopenia being a serious adverse event. Adverse events reported in the methotrexate group included nausea and vomiting, mild alopecia, increases in AST, development of perianal abscess, and serious adverse events including hypoalbuminemia, severe rash and atypical pneumonia. Withdrawals from the study were a result of serious adverse events in both arms of the trial. Ten per cent (3/30) of 6‐mercaptopurine patients (3/30) withdrew after a serious adverse event compared to 15% (4/27) of methotrexate patients. There was no statistically significant difference in the proportion of patients who withdrew due to an adverse event or who experienced a serious adverse event (RR 0.68, 95% CI 0.17 to 2.75). GRADE analyses indicated that the overall quality of the evidence supporting these outcomes was very low due to very sparse data (7 events for both comparisons) and high risk of bias.

Steroid sparing

In the two very small studies reporting steroid sparing data (Willoughby 1971; Rosenberg 1975), 87% (13/15) patients receiving maintenance therapy with azathioprine were able to reduce or discontinue steroids (steroid sparing) compared to 53% (8/15) patients receiving placebo (RR 1.59, 95% CI 0.97 to 2.61).

Discussion

This systematic review included 11 randomized controlled trials (881 participants) that evaluated the efficacy and safety of azathioprine or 6‐mercaptopurine for maintaining remission achieved by medical therapy in patients with quiescent Crohn's disease. Seven studies compared azathioprine to placebo (Candy 1995; Lémann 2005; O'Donoghue 1978; Panes 2013; Rosenberg 1975; Summers 1979; Willoughby 1971). Summers 1979 also compared azathioprine to sulfasalazine. Maté‐Jiménez 2000 compared 6‐mercaptopurine to mesalazine or methotrexate. One study compared azathioprine to budesonide (Mantzaris 2009); one study compared the combination of azathioprine and infliximab to infliximab monotherapy (Mantzaris 2004); and one study compared 6‐mercaptopurine to methotrexate (Maté‐Jiménez 2000). One study compared the early administration of azathioprine to a conventional management strategy (Cosnes 2013).

A pooled analysis of six studies (489 participants) suggests that azathioprine (1.0 to 2.5 mg/kg/day) is superior to placebo for maintenance of remission in quiescent Crohn's disease over a 6 to 18 month period. The number needed to treat for an additional beneficial outcome was nine. A GRADE analysis indicated that the overall quality of the evidence supporting this outcome was low due to sparse data (327 events) and unclear risk of bias. Five of the studies in the pooled analysis were rated as unclear risk of bias for random sequence generation, allocation concealment or incomplete outcome data. Although azathioprine may be effective for maintenance of remission it is associated with a significantly increased risk of adverse events, withdrawal due to adverse events and serious adverse events relative to placebo. Common adverse events reported in the placebo‐controlled trials include pancreatitis, leukopenia, nausea, allergic reaction and infection. The adverse effects of azathioprine are well recognized in clinical practice and limit its use. Azathioprine‐related serious adverse events lead to cessation of therapy in 9 to 25% of patients (Gearry 2004; Gearry 2005). Adverse events associated with azathioprine and 6‐mercaptopurine include nausea, allergic reaction, flu‐like illness, malaise, fevers, rash, abdominal pain, pancreatitis, hepatotoxicity, myelosuppression, and an increased risk of lymphoma (Dubinsky 2004; Kandiel 2005; Beaugerie 2008). Advances in the understanding of azathioprine and 6‐mercaptopurine drug metabolism have led to genetic and metabolite tests to help clinicians optimise the use of these drugs. Thiopurine methyltransferase (TPMT) enzyme activity can predict potentially life threatening myelosuppression in patients who are TPMT‐deficient (Dubinsky 2004; Gearry 2005). TPMT may also aid in determining optimal dosing (Dubinsky 2004; Gearry 2005). 6‐Thioguanine nucleotides and 6‐methylmercaptopurine concentrations are helpful in determining why a patient does not respond to a standard dose of azathioprine or 6‐mercaptopurine and may help avoid myelosuppression (Dubinsky 2004; Gearry 2005). The ratio of these metabolites can help differentiate between non‐compliance, under‐dosing, and drug resistance or refractory states (Dubinsky 2004; Gearry 2005). More research is required to determine the optimal use of these tests in patients with Crohn's disease. However, a randomized controlled trial looking at the role of metabolite monitoring proved not to be feasible and was terminated due to slow patient recruitment (NIDDK 2008).

The results of one small study (77 participants) suggest that azathioprine (2.0 to 2.5 mg/kg/day) may be superior to budesonide (6 to 9 mg/day) for maintenance of remission at one year (Mantzaris 2009). However this result should be interpreted with caution as a GRADE analysis indicated that the overall quality of the evidence supporting this outcome was low due to sparse data (47 events) and high risk of bias (no blinding). There were no differences in withdrawals due to adverse events or serious adverse events. However, GRADE analyses indicated the quality of the evidence supporting these outcomes was very low due to very sparse data (two events for both comparisons) and high risk of bias. Further research is needed to allow any firm conclusions regarding the comparative efficacy and safety of azathioprine and budesonide for maintenance treatment in quiescent Crohn's disease.

A pooled analysis of two studies (166 participants) found no difference between azathioprine (1.0 to 2.5 mg/kg/day) or 6‐mercaptopurine (1.0 mg/kg/day) and aminosalicylates (mezalazine 3 g/day or sulfasalazine 0.5 g/15 kg) in the proportion of patients who maintained remission at 12 months. A GRADE analysis indicated that the overall quality of the evidence supporting this outcome was low due to sparse data (113 events) and high or unclear risk of bias. Summers 1979 was rated as unclear risk of bias for random sequence generation and incomplete outcome data and Maté‐Jiménez 2000 was rated as high risk of bias for no blinding. A pooled analysis of two studies showed that antimetabolites (azathioprine or 6‐mercaptopurine) had a significantly increased risk of serious adverse events compared to aminosalicylates (mesalazine or sulphsalazine). However, a GRADE analysis indicated that the overall quality of the evidence supporting this outcome was very low due to sparse data (16 events) and high or unclear risk of bias. Further research with adequately powered trials is needed to allow any definitive conclusions regarding the comparative efficacy and safety of antimetabolites and aminosalicylates for maintenance therapy in Crohn's disease.

One small study (31 participants) found no difference between 6‐mercaptopurine (1 mg/kg/day) and methotrexate (10 mg/week) in the proportion of patients who maintained remission at 72 weeks. A GRADE analysis indicated that the overall quality of the evidence supporting this outcome was very low due to very sparse data (16 events) and high risk of bias. No differences were found with respect to adverse events, withdrawals due to adverse events, or serious adverse events. GRADE analyses indicated that the overall quality of the evidence supporting these outcomes was very low due to very sparse data (19, 5 and 5 events respectively) and high risk of bias. Moderate quality evidence from a single high quality trial indicates that intramuscular methotrexate at a dose of 15 mg/week is superior to placebo for maintenance of remission in Crohn's disease. The number needed to treat with methotrexate for an additional beneficial outcome was four (Patel 2014). Only two small studies compare 6‐mercaptopurine to methotrexate for maintenance of remission in Crohn's disease (Maté‐Jiménez 2000; Oren 1997), and no studies compare azathioprine to methotrexate. Further research with adequately powered trials is necessary to allow any conclusions regarding the comparative efficacy and safety of antimetabolites (azathioprine or 6‐mercaptopurine) and methotrexate for maintenance therapy in Crohn's disease.