Abstract

Background:

Prenatal smoking and drinking are associated with SIDS and neurodevelopmental disorders. Infants with these outcomes also have altered autonomic nervous system (ANS) regulation. We examined the effects of prenatal smoking and drinking on newborn ANS function.

Methods:

Pregnant women were enrolled in Northern Plains, USA (NP) and Cape Town (CT), South Africa. Daily drinking and weekly smoking data were collected prenatally. Physiological measures were obtained during sleep 12–96 hours post-delivery.

Results:

2,913 infants from NP and 4,072 from CT were included. In active sleep, newborns of mothers who smoked throughout pregnancy, compared to non-smokers, had higher breathing rates (2.2 breaths/min; 95% CI: 0.95, 3.49). Quit-early smoking was associated with reductions in beat-to-beat heart rate variability (HRV) in active (−0.08 sec) and quiet sleep (−0.11 sec) in CT. In girls, moderate-high continuous smoking was associated with increased systolic (3.0 mmHg, CI: 0.70, 5.24), and diastolic blood pressure (2.9 mmHg, CI: 0.72, 5.02). In quiet sleep, low-continuous drinking was associated with slower heart rate (−4.5 beat/min). In boys, low-continuous drinking was associated with reduced ratio of low-to-high frequency HRV (−0.11, CI: −0.21, −0.02).

Conclusions:

These findings highlight potential ANS pathways through which prenatal drinking and smoking may contribute to neurodevelopment outcomes.

Introduction

Although many women modify their drinking and smoking behavior following pregnancy recognition1,2, heightened risk of adverse outcomes associated with prenatal alcohol (PAE) and tobacco (PTE) exposures remains a public health concern, especially in low-resource settings and in populations with high prevalence of alcohol and tobacco use 3,4. There is well documented evidence of role of prenatal drinking and smoking on increased fetal loss, stillbirth, preterm birth, intrauterine growth restriction, sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS) and other neurodevelopmental disorders 5–7. Recent studies also linked PAE and PTE to dysregulation of the fetal and infant autonomic nervous system (ANS)8,9 and the newborn central nervous system10.

Alcohol and nicotine can directly affect the developing fetal brain leading to autonomic dysfunction and poor neurodevelopment11,12. Alcohol passed through the placenta is known to cause oxidative stress, mitochondrial damage, and alterations in the developing brain including malformations in the corpus callosum and cerebellum13–15. Nicotine alters fetal brain development by effects on cell proliferation and differentiation, specific neurotransmitters receptors, and disruption of neural activity in the brain16. Tobacco smoking and alcohol can also impact ANS development indirectly through shortening gestation and intrauterine growth restriction 17,18.

Impairment in the ANS regulation (cardiac, respiratory, and vascular) has been associated with SIDS, and adverse neurodevelopmental outcomes such as autism and ADHD5,19,20. Because of the increased incidence of SIDS among infants exposed to prenatal drinking and smoking 21, autonomic alterations associated with these exposures are important to understand. In addition to previous reports on alterations in SIDS victims’ brainstem regions involved in autonomic regulation22, members of the Prenatal and Alcohol in SIDS and Stillbirth (PASS) research team have reported on smoking and drinking associated alterations in the brainstem locations involved in cardiorespiratory functions and arousal in SIDS infants23. Other studies have shown that infants who subsequently die of SIDS have altered patterns of ANS activity during sleep including higher heart rate (HR), reduced HR variability (HRV), and abnormalities in the beat-to-beat dynamics24–30. Inadequate responses to hypotension while asleep may also play a role in the fatal SIDS event31,32.

Previous studies have o reported significant associations of prenatal drinking and smoking with reduced HRV in the fetus, and diminished HR responses to head-up tilting in newborns8,33,34. These studies have some methodological limitations including small sample sizes and limited exposure and covariate data. In the present study, we examined the role of prenatal drinking and smoking on parameters of ANS control in newborn infants in two large ethnically diverse cohorts of mother-infant dyads from the USA and South Africa. We hypothesized that prenatal drinking and smoking would affect newborn autonomic function and these effects will be contingent on timing, pattern and quantity of exposure. However, given the paucity of data with detailed measures of exposure as in the current study. we had no specific directional hypotheses.

Methods

Study population and data collection

Data for this study come from the Prenatal and Alcohol in SIDS and Stillbirth (PASS) Safe Passage Study. The Safe Passage Study was a prospective cohort study designed to evaluate the role of prenatal drinking and smoking on adverse pregnancy outcomes including stillbirth, SIDS, and fetal alcohol spectrum disorders (FASD). Participants were enrolled from antenatal clinics in Northern Plains, USA (South and North Dakota) and Cape Town, South Africa between August 2007 and January 2015. Pregnant women aged 16 years or older, at or after 6 weeks of gestation, carrying one or two fetuses were eligible to participate. Data on socioeconomic status, demographic, obstetric and medical history, periconceptional drinking and smoking were collected at the enrollment interview. Details on the study design and characteristics of the study population are published elsewhere35.

Exposures Assessment and characterization

Data on alcohol exposure were collected using a validated modification of the timeline follow back (TLFB) method36, where, at each study visit, participants reported detailed information on daily drinking ±15 days of their last menstrual period at enrollment visit and thirty days prior to their last known drinking day at each study visit. Participants also reported on the number of days they smoked per week and number of cigarettes smoked per day at enrollment and during the prenatal visits. Depending on the number and timing of the study visits for each participant, some data on daily drinking and smoking were missing. Missing data were imputed using a non-parametric algorithm called K nearest neighbor algorithm (k-NN)37. Using clustering methods, based on the amount and timing of drinking and smoking, the participants were divided into 4 smoking and 10 drinking groups38. Because several of the drinking groups had a small number of subjects they were collapsed into 4 groups for the current analyses. Women were categorized as moderate-to-high continuous smoking, low-continuous smoking, quit-early smoking, and non-smoking; and moderate-to-high continuous drinking, low-continuous drinking, quit-early drinking, and non-drinking groups (See supplementary methods on exposure imputation and exposure clustering).

ANS data measurement and data processing

Details on ANS measurement, processing and normative values in our study population have been published previously39. Newborns were tested 12–96 hours after delivery. Electrocardiograms (ECG) and respiration rates were collected using custom hardware and software, and blood pressure (BP) was collected using a clinical monitor. The standard protocol involved recording ECG, respiration rate, and BP signals during a 10-minute baseline period and in response to three rapid (~3–5 seconds) 45° head-up tilts while the infant was in the prone position. The resting state measures allowed the characterization of autonomic traits, whereas changes in autonomic state in response to tilt assessed the infant’s capacity to respond to an environmental challenge. As cardiorespiratory variables differ between sleep states, the records were subdivided into epochs coded as either active or quiet sleep states40,41.

Baseline parameters:

Baseline physiological variables were computed for 10 one-minute epochs prior to two baseline BP measurements. For each minute, the median the median R-wave to R-wave interval (RRi) was computed, and from the median RRi, heart rate (HR) was computed. The standard deviations of RRi (SD-RRi) and the square root of the mean of the squared successive differences in RRis (rMSSD) were computed as were low-frequency HRV (LF; HRV between 0.04 and 0.40 Hz) and high-frequency HRV (HF; HRV between 0.50 and 1.50 Hz) power from Fourier spectral analyses. The LF/HF ratio was also computed. For each minute, the median breath-to-breath interval, and breathing rate were computed. The long-term variability parameters (SD, LF power) evaluate a combination of sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems contributions to HRV. In contrast, measures of beat-to-beat variability (RMSSD, HF) are influenced largely by the parasympathetic nervous system, tied to rapid ANS reactivity. The LF/HF ratio has been interpreted as a measure of sympatho-vagal balance, with higher values indicating sympathetic predominance and lower values indicating parasympathetic predominance42.

Parameters in responses to head-up tilting

For HR, acute responses to tilts were computed as maximum HR-minimum HR during the first 15 seconds in the head-up position. The median maximum-minimum HR over the 3 tilts were analyzed. The pre-tilt values for systolic and diastolic BP were recorded 90 seconds before tilts and head-up BP values were recorded during the period just before returning to the horizontal position, 90 seconds after head-up tilting. Median changes in BP over the three tilts were analyzed.

Statistical analysis

Linear regression models were used to estimate associations of each prenatal drinking groups (reference: non-drinkers) and smoking groups (reference: non-smokers) with ANS parameters with separate models for each of the ANS outcomes. All models included infant sex, hours of life at assessment and gestational age (GA) at birth as covariates. Models included maternal education, household crowding index, prenatal depression scores measured with the Edinburgh scale, and study site as potential confounders. Missing indicators were included in the multivariate models when covariate data were missing. Outcome variables that were not normally distributed were log transformed (SD-RRi, RMSSD). Analyses combining participants across sites were performed first, and then, separately for each of the two sites. Additional sex stratified analyses were also performed. Because there were site differences in key characteristics of the participants, study site was included as a covariate in site combined models. Additional analyses stratified by site were also obtained. The overlap between exposure clusters (4 smoking groups and 4 drinking groups) was insufficient to examine the effects of interaction between drinking and smoking on ANS outcomes. Because we have related outcomes and covariates, adjustment for multiple comparisons (such as the Bonferroni method) was not appropriate43–45. We have reported all analyses and estimates (and confidence intervals) with equal emphasis and detail in the manuscript. All analyses were performed in SAS software version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary NC).

Ethics Statement:

Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. Ethical approval was obtained from Stellenbosch University, Avera Health, Sanford Health, the Indian Health Service and from participating Tribal Nations.

Results

The final analyses included 6,985 singletons born at term, of them 2,913 (42%) were from Northern Plains and 4,072 (58%) were from South Africa. We excluded infants with missing exposure data, preterm and post-term infants, and infants whose mothers used psychiatric medication during pregnancy (Supplemental Figure S1). South African women had poorer socioeconomic status, as reflected in lower educational attainment, higher unemployment rates, higher crowding index, and higher proportion living without a partner. Although mean gestational ages at birth were similar in both sites, South African newborns were about 400 g lighter on average (Table 1). ANS parameters were obtained later in South Africa (60. 3 hours, SD 51.3) compared to the Northern Plains site (29.9 hours, SD 47.3). This difference was due the hospital policy in South Africa of discharging infants within 24 hours of delivery, so they needed to be brought in for assessment later.

Table 1:

Characteristics of the study population (n=6915) by site

| Cape Town, South Africa N= 4072 | Northern Plains, USA N=2913 | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| N1 (%) or mean (SD) | N1 (%) or mean (SD) | ||

| Maternal characteristics | |||

| Maternal age, years | 24.7 (5.8) | 26.8 (5.3) | |

| Marital status | |||

| Married/cohabiting | 2195 (53.9) | 2290 (78.6) | |

| Unmarried | 1877 (46.1) | 623 (21.4) | |

| Education | |||

| Primary school education | 313 (7.7) | 46 (1.6) | |

| Some high school education | 2738 (67.2) | 480 (16.5) | |

| High school completed | 876 (21.5) | 531 (18.2) | |

| Higher than high school | 142 (3.5) | 1855 (63.7) | |

| Employment status | |||

| Employed | 1183 (29.1) | 1914 (65.1) | |

| Unemployed | 2889 (70.9) | 999 (34.3) | |

| BMI, kg/m2 | |||

| <18.5 | 287 (7.1) | 61 (2.1) | |

| 18.5–25 | 2010 (49.4) | 1045 (35.9) | |

| 25– 30 | 957 (23.5) | 877 (30.1) | |

| 30+ | 818 (20.1) | 930 (31.9) | |

| Parity | |||

| Nulliparous | 1597 (38.8) | 935 (32.1) | |

| Parity 1–2 | 1265 (31.1) | 937 (32.2) | |

| Parity >3 | 739 (18.2) | 546 (18.7) | |

| Mode of delivery | |||

| Normal and assisted delivery | 3650 (89.70) | 2234 (76.72) | |

| Cesarean section | 419 (10.30) | 678 (23.28) | |

| Crowding index | 1.6 (0.9) | 0.7 (0.6) | |

| Depression, Edinburgh Depression Score | 12.77 (5.92) | 5.46 (4.34) | |

| Infant characteristics | |||

| Birth weight, g | 3107.7 (447.3) | 3520. 9 (457.3) | |

| Gestational age, weeks | 39.4 (1.2) | 39.4 (1.1) | |

| Sex | |||

| Female | 1985 (48.8) | 1469 (50.4) | |

| Male | 2087 (51.2) | 1444 (49.6) | |

| Hours of life at measurement | 60.26 (51.27) | 29.93 (47.56) | |

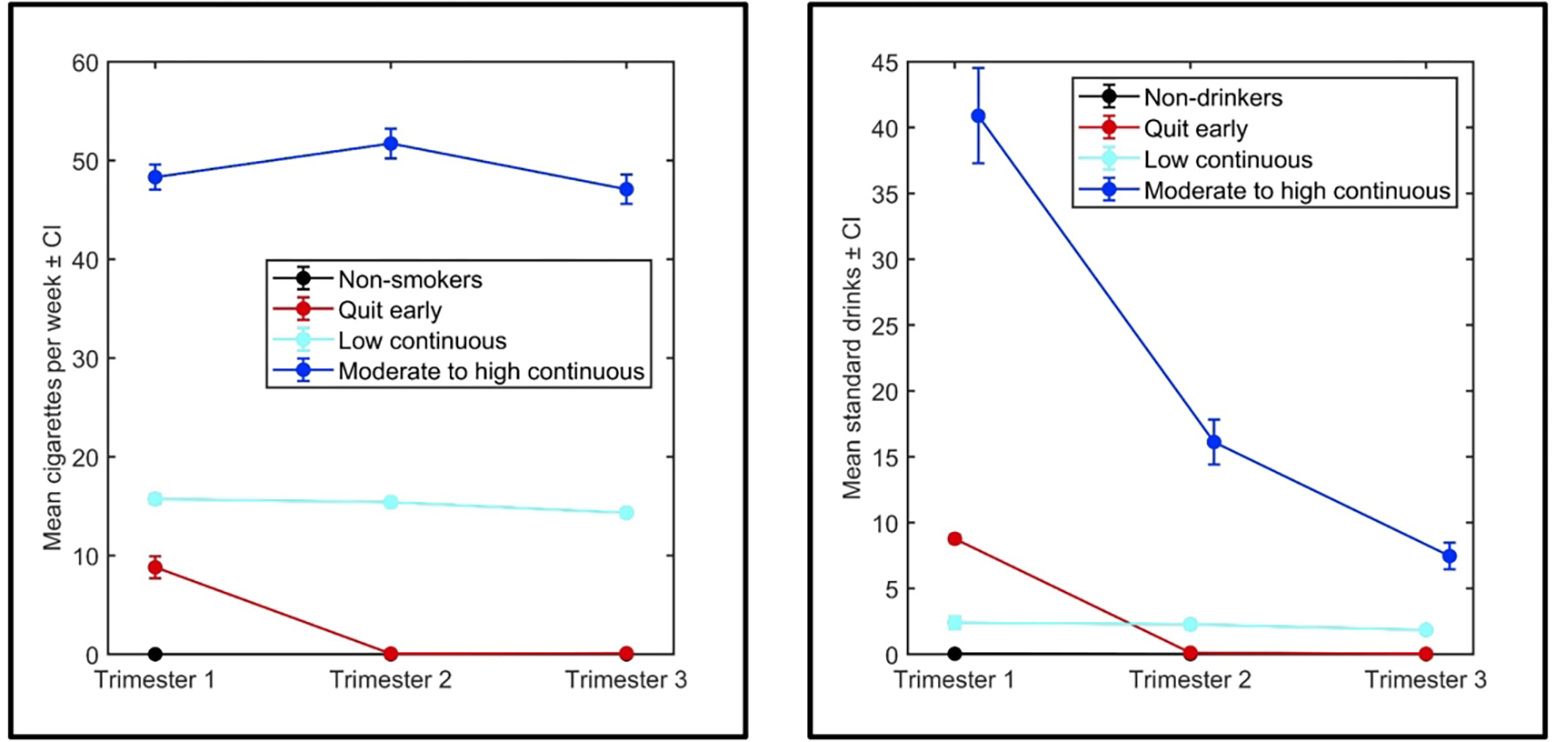

The prevalence of smoking was higher in South Africa (61%) than Northern Plains (24%). In South Africa, 23% pregnant women continued smoking in moderate to high amount and 35% continued with a low amount throughout the pregnancy while only 17% woman in Northern Plains continued. Women in the moderate-to-high continuous, mild continuous and quit early groups smoked 48.31 (SD 21.71), 15.72 (SD 10.28), and 8.81 (SD 9.92) cigarettes/ week, on average in first trimester, respectively (Figure 1 and Supplemental Table 1), with a declining number of cigarettes smoked in subsequent trimesters in all groups. Approximately half of the pregnant women in both sites reported drinking during pregnancy. The majority (43%) of NP participants quit drinking in the first trimester, only 8% drank throughout pregnancy, while 29% participants from SA continued to drink throughout (Supplemental Supplemental Table S3). Women in the high moderate-to-continuous, mild continuous and quit early groups drank 40. 9 (SD 60.1), 2.4 (SD 3.8), and 8.9 (SD 7.4) drinks in first trimester, respectively (Figure 1 and Supplemental Table 3). Women in the moderate-to-high continuous drinking group reported 2 (interquartile range, IQR 0–5), 1 (IQR 0–2), and 0 (IQR 0–1) binge episodes in trimester 1, 2 and 3 respectively. Women in low continuous and quit early group rarely binged.

Figure 1:

Magnitude of smoking and drinking in each trimester by clusters

Associations of smoking with baseline ANS parameters (Table 2, Supplemental Tables S5, S6)

Table 2:

Association of prenatal smoking with ANS measures at baseline in combined site analyses (Infants whose mothers did not smoke during pregnancy formed the reference group. Results with p-values <0.01, <0.05, <0.10 are bolded)

| Non-smoker Mean (95%CI) | Quit early Mean difference (95%CI) P value |

Low continuous Mean difference (95%CI) P value |

Moderate to high continuous Mean difference (95%CI) P value |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (bpm) | 126.13 (125.41, 126.84) | 1.07 (−0.72, 2.87) (0.24) |

0.096 (−0.88, 1.07) (0.84) |

−0.019 (−1.21, 1.16) (0.97) |

| log10SD-RRi (s) | −1.61 (−1.62, −1.59) | −0.005 (−0.04, 0.02) (0.72) |

0.002 (−0.014, 0.02) (0.20) |

0.02 (−0.001, 0.04)

(0.06) |

| log10RMSSD (s) | −1.95 (−1.96, −1.94) | −0.027 (−0.060, 0.0005) (0.10) |

−0.0002 (0.02, 0.01) (0.98) |

0.015 (−0.007, 0.04) (0.17) |

| Breaths/min | 56.05 (55.29, 56.82) | −1.09 (−3.03, 0.84) (0.26) |

0.79 (−0.25, 1.85) (0.13) |

2.22 (0.95, 3.49)

(0.0006) |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 83.12 (81.96, 84.28) | 0.88 (−2.15, 3.91) (0.56) |

0.44 (−1.11, 1.98) (0.57) |

1.24 (−0.65, 3.14) (0.19) |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 50.82 (49.86, 51.77) | 1.44 (−1.03, 3.92) (0.25) |

0.87 (−0.39, 2.14) (0.17) |

1.53 (−0.02, 3.09)

(0.053) |

| Low frequency power of HRV | −5.88 (−5.90, −5.86) | 0.0003 (−0.059, 0.059) (0.992) |

0.002 (−0.029, 0.034) (0.881) |

0.03 (−0.003, 0.07)

(0.075) |

| High frequency power of HRV | −6.83 (−6.85, −6.80) |

−0.077 (−0.14, −0.011)

(0.02) |

0.009 (−0.026, 0.045) (0.59) |

0.04 (−0.0013, 0.085)

(0.057) |

| Ratio of low and high frequency power of HRV | 0.94 (0.92, 0.97) |

0.05 (−0.007, 0.11)

(0.08) |

0.006 (−0.025, 0.038) (0.709) |

0.013 (−0.025, 0.051) (0.504) |

| Quiet sleep | ||||

| HR (bpm) | 120.53 (119.39, 121.67) | −0.49 (−3.15, 2.17) (0.71) |

0.58 (−1.04, 2.19) (0.48) |

1.03 (−1.04, 3.11) (0.32) |

| log10SD-RRi (s) | −1.74 (−1.76, −1.72) |

0.05 (−0.002, 0.10)

(0.06) |

−0.01 (−0.05, 0.02) (0.43) |

0.02 (−0.02, 0.06) (037) |

| log10RMSSD (s) | −1.93 (−1.95, −1.90) | 0.009 (−0.04, 0.07) (0.73) |

−0.017 (−0.05, 0.016) (0.31) |

0.007 (−0.036, 0.051) (0.74) |

| Breaths/min | 45.68 (44.65, 46.72) | −1.78 (−4.19, 0.63) (0.14) |

0.16 (−1.31, 1.63) (0.82) |

1.70 (−0.18, 3.58)

(0.07) |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 82.75 (81.13, 84.38) | −0.29 (−4.01, 3.41) (0.87) |

0.72 (−1.52, 2.97) (0.52) |

0.06 (−2.75, 2.87) (0.96) |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 50.17 (48.97, 51.37) | −0.70 (−3.45, 2.03) (0.61) |

−0.21 (−1.87, 1.45) (0.80) |

−1.32 (−3.40, 0.74) (0.21) |

| Low frequency power of HRV | −6.27 (−6.32, −6.21) | 0.12 (0.00074, 0.24) (0.04) |

−0.029 (−0.103, 0.043) (0.424) |

0.056 (−0.036, 0.15) (0.234) |

| High frequency power of HRV | −6.84 (−6.89, −6.80) | −0.04 (−0.149, 0.067) (0.45) |

−0.037 (−0.103, 0.028) (0.26) |

0.028 (−0.055, 0.113) (0.506) |

| Ratio of low and high frequency power of HRV | 0.58 (0.53, 0.63) |

0.117 (−0.003, 0.238)

(0.056) |

0.015 (−0.057, 0.087) (0.68) |

0.039 (−0.054, 0.134) (0.40) |

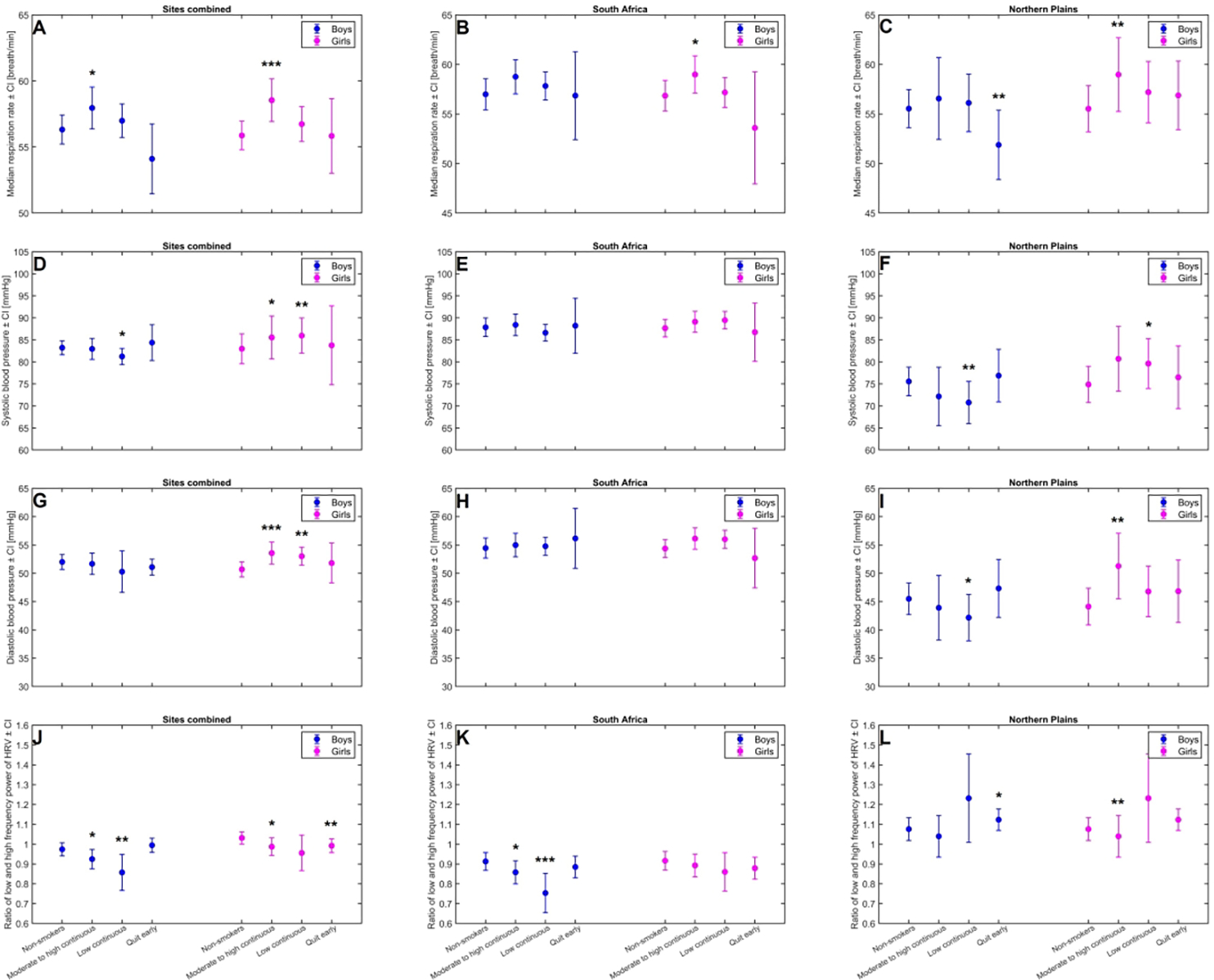

In the site combined data analyses, compared to non-smokers, moderate-to-high-continuous smoking was associated with an increase in breathing rate in both sleep states (p<0.001, and p =0.07 respectively, Table 2). Similar results were seen for active sleep at each site (SA: 2.00 breaths/min, 95% CI: 0.43, 3.56, NP: 2.38 95% CI: −0.15, 4.91, Tables S-5, S-6). However, this association was primarily driven by results for girls (Figure 2, panel A, B, C).

Figure 2: Marginal means in each exposure categories, stratified by study site and infant sex.

Panel A, B and C shows median respiration rate for smoking exposure groups for both sites, South Africa, and Northern Plains, respectively.

Panel D, E, F shows Systolic BP for smoking exposure groups for both sites, South Africa and Northern Plains, respectively.

Panel G, H, I show diastolic BP for smoking exposure groups for both sites, South Africa and Northern Plains, respectively.

Panel J, K, L shows ratio of low-to-high frequency heart rate variability for alcohol exposure groups for both sites, South Africa, and Northern Plains, respectively.

*p<0.1, **p <0.05, ***p <0.01 indicates significance of the difference in marginal mean in comparison to the reference group, non-smoker, or non-drinker

There were no significant associations of smoking with HR parameters in the analyses with sites combined. In SA, compared to infants of non-smoker mothers, SD-RRi in active sleep was 0.02 s (95% CI: 0.002, 0.04) greater in the moderate-to-high-continuous smoking group (Supplemental Table S5), while rMSSD in active sleep (−0.08 sec, 95% CI: −0.14, −0.03) and quiet sleep (−0.11, 95% CI: −0.22, −0.001) was decreased in the quit-early smoking group (Tables S-5, S-6 respectively). In NP, SD-RRi in quiet sleep was increased in the quit-early group (p=0.02, Supplemental Table S6).

There were no significant associations of smoking with diastolic BP in combined analyses. In sex stratified analyses, moderate-to-high continuous smoking was associated with higher systolic (2.97 mmHg, CI: 0.70, 5.24, p=0.01) and diastolic BP (2.87 mmHg, CI: 0.72, 5.02, p=0.009) among girls only (Figure 2, panel D, G.)

Associations of alcohol with Baseline ANS parameters (Table 3, Supplemental Tables S7, S8)

Table 3:

Association of prenatal alcohol with ANS measures at baseline in combined site analyses. (Infants whose mothers did not drink during pregnancy formed the reference group. Results with p-values <0.01, <0.05, <0.10 are bolded)

| NonMean (95%CI) | Quit early Mean difference (95%CI) P value |

Low continuous Mean difference (95%CI) P value |

Moderate to high continuous Mean difference (95%CI) P value |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Active sleep | ||||

| HR (bpm) | 126.36 (125.67, 127.05) | 0.46 (−0.37, 1.30) (0.27) |

−0.76 (−2.74, 1.22) (0.45) |

0.56 (−0.54, 1.67) (0.31) |

| log10SD-RRi (s) | −1.61 (−1.61, −1.59) | −0.005 (−0.02, 0.009) (0.51) |

0.004 (−0.03, 0.04) (0.80) |

−0.003 (−0.02, 0.015) (0.73) |

| log10RMSSD (s) | −1.96 (−1.97, −1.94) | −0.005 (−0.02, 0.01) (0.49) |

0.022 (−0.01, 0.58) (0.23) |

0.006 (−0.01, 0.03) (0.53) |

| Breaths/min | 56.05 (55.28, 56.82) | −0.14 (−1.03, 0.75) (0.76) |

−1.61 (−3.72, 0.50) (0.13) |

−0.45 (−1.64, 0.73) (0.45) |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 84.22 (83.09, 85.35) | −0.21 (−1.55, 1.13) (0.31) |

−1.19 (−4.43, 2.05) (0.47) |

−0.43 (−2.19, 1.31) (0.62) |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 52.04 (51.12, 52.97) | 0.22 (−0.87, 1.33) (0.68) |

−0.79 (−3.45, 1.87) (0.56) |

−0.48 (−1.92, 0.95) (0.50) |

| Low frequency power of HRV | −5.86 (−5.88, −5.84) | −0.015 (−0.043, 0.011) (0.26) |

−0.017 (−0.082, 0.048) (0.609) |

−0.013 (−0.05, 0.022) (0.45) |

| High frequency power of HRV | −6.86 (−6.89, −6.84) | −0.007 (−0.038, 0.022) (0.62) |

0.089 (0.017, 0.16)

(0.015) |

0.036 (−0.004, 0.077)

(0.079) |

| Ratio of low and high frequency power of HRV | 1.002 (0.98, 1.02) | −0.014 (−0.04, 0.01) (0.31) |

−0.08 (−0.15, −0.02)

(0.008) |

−0.04 (−0.07, −0.006)

(0.02) |

| Quiet sleep | ||||

| HR (bpm) | 122.28 (121.16, 123.41) | 0.07 (−1.28, 1.42) (0.10) |

−4.53 (−7.75, −1.32)

(0.006) |

−1.41 (−3.30, 0.46) (0.13) |

| log10SD-RRi (s) | −1.72 (−1.74, −1.69) | −0.001 (−0.03, 0.02) (0.92) |

−0.02 (−0.08, 0.05) (0.61) |

0.002 (−0.03, 0.04) (0.92) |

| log10RMSSD (s) | −1.94 (−1.96, −1.91) | −0.006 (−0.04, 0.02) (0.64) |

0.006 (−0.06, 0.08) (0.85) |

0.017 (−0.022, 0.06) (0.39) |

|

Breaths/min |

45.84 (44.82, 46.86) | −0.51 (−1.73, 0.71) (0.41) |

−0.54 (−3.45, 2.36) (0.71) |

0.48 (−1.22, 2.20) (0.57) |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 84.02 (82.48, 85.55) | −1.22 (−3.14, 0.70) (0.21) |

−3.46 (−7.92, 0.98) (0.12) |

0.13 (−2.38, 2.65) (0.10) |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 43.61 (40.65, 46.56) |

−1.36 (−2.78. 0.05)

(0.06) |

−3.29 (−6.59, 0.006)

(0.05) |

0.99 (−0.86. 2.84) (0.29) |

| Low frequency power of HRV | −6.23 (−6.28, −6.18) | 0.015 (−0.04, 0.07) (0.62) |

−0.02 (−0.17, 0.11) (0.72) |

0.003 (−0.08, 0.08) (0.93) |

| High frequency power of HRV | −6.86 (−6.90, −6.81) | −0.02 (−0.08, 0.02) (0.32) |

−0.014 (−0.14, 0.11) (0.82) |

0.04 (−0.03, 0.11) (0.28) |

| Ratio of low and high frequency power of HRV | 0.61 (0.56, 0.67) | 0.03 (−0.02, 0.09) (0.22) |

0.02 (−0.12, 0.16) (0.75) |

−0.02 (−0.11, 0.05) (0.53) |

In site combined analyses, compared to infants of non-drinker mothers, infants in the low-continuous drinking group had 4.53 beats/min lower HR in quiet sleep (95% CI: −7.75, −1.32, Table 3). Similar results were seen in SA for the low-continuous and moderate-to-high continuous drinking group (Supplemental Table S7). Compared to no drinking, low-continuous drinking was associated with a reduced ratio of LF/HF in active sleep in combined analyses (−0.08 95% CI −0.15, −0.02, Table 3), as well as in site stratified analyses (Tables S-7, S-8). Further stratification by sex revealed that this association was significant among boys only (Figure 2, Panel J, K, L).

In combined analyses, diastolic BP during quiet sleep was lower in low-continuous (−3.29 mmHg, 95% CI: −6.59, −0.006) and quit-early (−1.36 mmHg, 95% CI: 2.78, 0.05) drinking groups (Table 3) compared to non-drinkers. Low-continuous drinking was associated with reduced diastolic BP in the NP (p=0.04, Supplemental Table S8) but not in SA.

Associations of smoking on tilt responses (Table 4, Supplemental Tables S9, S10)

Table 4:

Association of prenatal smoking with mean changes in cardiorespiratory variables in response to 45° head-up tilts in site combined analyses. (Infants whose mothers did not smoke during pregnancy formed the reference group. Results with p-values <0.01, <0.05, <0.10 are bolded)

| Non-smoker Mean (95%CI) | Quit early Mean difference (95%CI) (P value) |

Low continuous Mean difference (95%CI) (P value) |

Moderate to high continuous Mean difference (95%CI) (P value) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Active sleep | ||||

| Δ sustained HR (bpm) | 2.52 (2.08, 2.96) | 0.56 (−1.64, 0.52) (0.31) |

−035 (−0.95, 0.24) (0.24) |

−0.29 (−1.03, 0.45) (0.44) |

| Δ acute HR (bpm) | 22. 98 (22.39, 23.57) | −0.69 (−2.13, 0.75) (0.34) |

1.03 (0.23, 1.83)

(0.01) |

1.22 (0.23, 2.21)

(0.02) |

| Δ rMSSD-RRi (s) | −0.57 (−0.80, −0.33) | 0.46 (−0.12, 1.04) (0.12) |

0.35 (0.03, 0.67)

(0.03) |

−0.09 (−0.49, 0.30) (0.64) |

| Δ change in breathing (breaths/min) | −3.73 (−4.27, −3.19) | 0.35 (−0.98, 1.68) (0.60) |

0.81 (0.07, 1.54)

(0.03) |

−0.005 (−0.91, 0.90) (0.99) |

| Δ systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | −6.04 (−6.76, −5.30) |

3.05 (1.22, 4.89)

(0.001) |

0.68 (−0.29, 1.65) (0.16) |

−0.22 (−1.42, 0.98) (0.72) |

| Δ diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | −6.49 (−7.31, −5.83) |

1.95 (0.31, 3.58)

(0.01) |

0.82 (−0.03, 1.69) (0.06) |

0.08 (−0.98, 1.14) (0.88) |

| Quiet sleep | ||||

| Δ sustained HR (bpm) | 3.39 (2.82, 3.98) | 0.89 (−0.60, 2.38) (0.24) |

−0.38 (1.19, 0.0.41) (0.34) |

0.34 (−0.65, 1.32) (0.50) |

| Δ acute HR (bpm) | 22.39 (21.54, 23.24) |

−1.89 (−4.11, 0.32)

(0.09) |

0.08 (−1.08, 1.24) (0.89) |

0.40 (−1.03, 1.83) (0.85) |

| Δ rMSSD-RRi (s) | −1.06 (−1.41, −0.71) |

−0.92 (−1.82, −0.015)

(0.05) |

0.12 (−0.36, 0.61) (0.61) |

0.27 (−0.32, 0.86) (0.36) |

| Δ change in breathing (breaths/min) | −3.73 (−4.27, −3.19) | 0.30 (−1.19, 1.79) (0.69) |

−0.36 (−1.17, 0.46) (0.39) |

−0.23 (−1.22, 0.77) (0.65) |

| Δ systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | −5.07 (−5.89, −4.25) | −0.19 (−2.38, 2.00) (0.86) |

−0.02 (−1.12, 1.07) (0.97) |

0.37 (−0.95, 1.69) (0.58) |

| Δ diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | −5.83 (−6.53, −5.12) | −0.24 (−2.08, 1.61) (0.80) |

0.34 (−0.57, 1.26) (0.46) |

0.32 (−0.78, 1.43) (0.57) |

The decrease in active sleep breathing rates following head-up tilt was less pronounced in low-continuous smoking group (0.81 breaths/min, 95% CI: 0.07, 1.54, Table 4) compared to non-smokers. In stratified analyses, this association was significant in SA (Supplemental Table S9) but not in the NP (Supplemental Table S10).

In site combined analyses, the acute HR responses to tilt were increased during active sleep in the low-continuous (1.03 beats/min, 95% CI: 0.23, 1.83) and the moderate-to-high-continuous (1.22 beats/min, 95% CI: 0.23, 2.21) smoking groups compared to non-smokers (Table 4). The increases in the acute HR response in the moderate-to-high-continuous smoking group was significant in SA only (p=0.02, Supplemental Table S9). The decrease in RMSSD following head up tilt seen in the non-smoking (reference group) during active sleep was not seen in the low-continuous smoking group (0.35 sec, 95% CI: 0.03, 0.67, Table 4). A less marked reduction of RMSSD values in quiet sleep during head-up tilt was found in quit-early smoking group (p=0.05, Table 4) in site combined analyses.

In combined sites analyses, there were smaller decreases in systolic (3.05 mmHg, 95% CI: 1.22, 4.89) and diastolic BP (1.95 mmHg, 95% CI: 0.31, 3.58) following head up tilts during active sleep in the quit-early smoking group compared to non-smoker group (Table 4). These differences remained significant in NP (Supplemental Table S10). Decreases in diastolic BP to tilt in active sleep were also diminished in the low-continuous smoking group compared to non-smoking group, in site combined analyses (0.82 mmHg, 95% CI: −0.03, 1.69, Table 4) and in NP (2.57, 95% CI: 0.51, 4.63, Supplemental Table S10).

Associations of alcohol on tilt responses (Table 5, Supplemental Tables S11, S12)

Table 5:

Association of prenatal drinking with mean changes in cardiorespiratory variables in response to 45° head-up tilts in both study sites. (Infants whose mothers did not drink during pregnancy formed the reference group. Results with p-values <0.01, <0.05, <0.10 are bolded)

| Non-drinker Mean (95%CI) | Quit early Mean difference (95%CI) (P value) |

Low continuous Mean difference (95%CI) (P value) |

Moderate to high continuous Mean difference (95%CI) (P value) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Active sleep | ||||

| Δ sustained HR (bpm) | 2.29 (1.86, 2.71) | −0.21 (−0.72, 0.28) (0.40) |

−0.22 (−1.45, 1.00) (0.72) |

0.17 (−0.51, 0.86) (0.62) |

| Δ acute HR (bpm) | 23.08 (22.51, 23.64) | −0.23 (−0.91, 0.44) (0.50) |

1.33 (−0.29, 2.95) (0.10) |

0.09 (−0.83, 1.01) (0.85) |

| Δ rMSSD-RRi (ms) | −0.34 (−0.57, −0.12) | −0.11 (−0.38, 0.16) (0.42) |

0.09 (−0.56, 0.75) (0.77) |

−0.15 (−0.52, 0.22) (0.42) |

| Δ change in breathing (breaths/min) | −3.95 (−4.46, −3.43) | 0.47 (−0.14, 1.09) (0.12) |

1.81 (0.32, 3.29) (0.02) |

−0.29 (−1.14, 0.55) (0.49) |

| Δ systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | −5.60 (−6.29, −4.90) | 0.15 (0.69, 1.01) (0.31) | 0.39 (−1.57, 2.37) (0.69) |

1.22 (0.11, 2.33)

(0.03) |

| Δ diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | −6.09 (−6.71, −5.47) | 0.32 (−0.43, 1.07) (0.40) |

0.39 (−1.35, 2.13) (0.66) |

0.55 (−0.43, 1.54) (0.26) |

| Quiet Sleep | ||||

| Δ sustained HR (bpm) | 3.81 (3.24, 4.38) | −0.37 (−1.04, 0.31) (0.28) |

−0.82 (−2.42, 0.78) (0.31) |

0.38 (−0.51, 1.28) (0.39) |

| Δ acute HR (bpm) | 22.17 (21.33, 23.01)) | −0.68 (−1.66, 0.31) (0.17) |

0.29 (−2.08, 2.66) (0.80) |

−0.12 (−1.43, 1.17) (0.84) |

| Δ rMSSD-RRi (ms) | −1.09 (−1.44, −0.75) |

0.44 (0.03, 0.84)

(0.04) |

−0.58 (−1.55 0.38) (0.23) |

−0.21 (−0.75, 0.32) (0.43) |

| Δ change in breathing (breaths/min) | −2.39 (−2.97, −1.81) | −0.08 (−0.76, 0.61) (0.83) |

−1.09 (−2.71, 0.52) (0.18) |

−0.34 (−1.24, 0.56) (0.46) |

| Δ systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | −4.85 (−5.65, −4.04) | −0.34 (−1.32, 0.64) (0.50) |

−0.35 (−2.53, 1.83) (0.75) |

−0.05 (−1.27, 1.17) (0.93) |

| Δ diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | −5.81 (−6.50, −5.13) | −0.03 (−0.85, 0.79) (0.94) |

0.11 (−1.72, 1.94) (0.90) |

0.27 (−0.75, 1.30) (0.59) |

The decrease in breathing rate in active sleep following head up tilting was less pronounced in the low-continuous drinking group (1.81 breaths/min, 95% CI: 0.32, 3.29, Table 5) compared to non-drinking group. In stratified analyses this association remained significant in NP but not in SA. In the NP, decreases in breathing in quiet sleep to head up tilt were diminished among low-continuous drinking (4.55 breaths/min, 95% CI: 0.19, 8.91, Supplemental Table S12),

Compared to non-drinking group, the decrease in RMSSD during quiet sleep was diminished in the quit-early drinking group (0.44 sec, 95% CI: 0.03, 0.84, Table 5) but not in site stratified analyses (Tables S-11 S-12).

Compared to non-drinking group, decreases in systolic BP in active sleep following head up tilts were less pronounced in the moderate-to-high-continuous drinking group in site combined analyses (1.22 mmHg, 95% CI: 0.11, 2.33, Table 5), which remained significant in SA (Supplemental Table S11), but not in the NP (Supplemental Table S12). In NP, decreases in diastolic BP in quiet sleep were diminished among moderate-to-high-continuous drinking group (4.36 mmHg, 95% CI: 1.41, 7.30, Supplemental Table S12).

Discussion

In this study, data from two large socio-culturally and ethnically diverse cohorts were used to evaluate the effects of prenatal drinking and smoking on ANS parameters extracted from physiological signals acquired from term newborns at birth. We found significant associations of prenatal smoking with newborn breathing and rMSSD during baseline, as well as greater acute changes in HR, and diminished changes in systolic and diastolic BP in response to head up tilts. There was a significant association between smoking and blood pressure among girls only. Prenatal drinking was associated with reductions in BP, reductions in the ratio of low to high frequency HRV, and diminished breathing rate and systolic BP responses to tilt. The associations of prenatal smoking and drinking were more pronounced in South African newborns, where women, on average, drank and smoked at higher levels, and were more likely to continue to drink and smoke throughout the pregnancy than women in the Northern Plains.

Moderate to high continuous smoking was associated with higher breathing rates. This extends the literature linking prenatal smoking to alterations in regulation of infant respiration, specifically regarding the literature reporting increases in the frequency and length of obstructive apneas46. Evidence from animal studies indicates maternal smoking leads to nicotine-induced cholinergic sensitivity of respiratory neurons of neonatal mice47, a mechanism that could predispose newborns to SIDS. Prenatal smoking has also been shown to adversely impact airway development, leading to abnormalities associated with an increased tendency to wheeze and higher susceptibility to respiratory infections in early childhood48.

Our results support the conclusion that prenatal smoking alters key aspects of cardiovascular regulation in newborn infants. The finding that prenatal smoking is associated with increases in baseline BP is consistent with a prior report by Beratis et al 49,50. With regard to the responses to tilt, in a prior study in the NP, smaller increases in HR following head up tilting were found in tobacco exposed infants8. Consistent with this, in our study, infants of non-smokers had significant increases in HR following tilt whereas infants exposed to smoking did not (see Table 4). However, in contrast Browne et al. found infants of smoking mothers had a larger decrease in blood pressure to tilt44, though the number of subjects assessed in the newborn period was small (26 non-smokers, 24 smokers).

Ours is the first study to report a significant reduction in the ratio of low-to-high frequency HRV among infants whose mothers drank throughout the pregnancy in moderate-to-high amounts. This ratio is interpreted as a measure of sympathovagal balance, although this remains controversial51 has been utilized as potential marker for social arousal and engagement52. The changes found suggest that prenatal drinking is associated with a greater relative parasympathetic control of HR. In contrast, an increase in the ratio of low-to-high frequency HRV associated with prenatal smoking was reported in other smaller studies53,54. Greater effects of smoking on the ratio of low-to-high HRV among boys is potentially related to their greater vulnerability, given that male infants who are more likely to die of SIDS55. Similar sex differences in autonomic regulation are also reported in animal studies56. Taken together, these results indicate that the effects of smoking and drinking are not mediated through a common neurophysiological or psychological mechanism.

We also found moderate-to-high continuous smoking was associated with increases in systolic and diastolic BP among newborn girls. Similar effects were reported in prior studies among adolescent girls 57,58. Unlike previous studies in newborns and fetuses8,9, we found no statistically significant associations of prenatal drinking on HR and HRV in active sleep. However, the average amount of alcohol consumed in our study populations was considerably lower than in previous studies. We also did not observe any significant associations of smoking on newborn baseline HR despite significant associations with fetal HR among the same cohort9.

The findings related to first trimester exposures followed by cessation in the quit early groups are potentially caused by the impact of withdrawal from smoking and drinking on maternal autonomic function and psychology, and, in turn, effects of these changes on fetal and infant physiology. Smoking cessation during pregnancy is known to elevate maternal blood pressure59,60. In addition, women quitting smoking and drinking may experience depressed mood, anxiety and stress symptoms61,62. Although we adjusted for maternal depression in the analyses, residual confounding is plausible. Another limitation of our study is measurement error in the exposure assessment. Since smoking and drinking were based on self-reports, it is likely that there was underreporting by some pregnant women exposed to anti-smoking and anti-drinking information63 and this could have contributed to less robust findings. In addition, data on medications related to smoking cessation or heart arrhythmias were not collected, therefore we could not account for these potential contributions in the analyses. Given the low proportion of women quitting smoking in both sites and low socioeconomic condition of the participants, it was unlikely that many would have access to such interventions.

Strengths of our study include extensive prospectively collected alcohol and smoking data with rigorous quality controls, which allowed us to evaluate the role of both quantity and timing of the exposure. To date, ours is the largest epidemiological study to examine the role of PAE and PTE on newborn ANS in a population-based study. We measured multiple aspects of autonomic activities including HRV, BP and breathing rates, which allowed evaluation of their coordinated activities. We also had detailed information on several potential confounders that were not accounted for in previous studies. While studies conducted in laboratory settings have precise measurements of smoking and alcohol exposures and increased confounder control, such findings are not directly generalizable to human population health. Our findings are generalizable to pregnant women and their infants of similar racial, ethnic and socioeconomic backgrounds.

Conclusion

We observed that prenatal smoking and drinking alters autonomic function in term newborns. Specifically, effects of smoking on breathing rate, beat-to-beat HRV and effects of drinking on low-to-high frequency HRV highlight the pathways through which prenatal drinking and smoking could be linked to risk of SIDS and neurodevelopmental disorders like ADHD24–26,64. While the changes in physiological measurement we presented might not meet thresholds for what may be termed clinical significance, they do indicate changes in ANS regulation profiles. Given that SIDS occurs when multiple factors intersect (vulnerable infant, critical period and exogenous trigger) even small shifts in physiology can move infants into high-risk categories. Similar shifts in physiology have been reported in other at risk populations such as preterm infants65. The current study provides new evidence to support the conclusion that prenatal exposure to smoking and alcohol can alter newborn autonomic function. Given the high prevalence of prenatal smoking and drinking and their known associations with postnatal outcomes such as SIDS, and poor neurodevelopment, early examination of ANS parameters can serve as a marker for identification of newborns at risk of adverse outcomes.

Supplementary Material

Impact:

In this prospective cohort study of 6,985 mother-infant dyads prenatal drinking and smoking were associated with multiple ANS parameters.

Smoking was associated with increased neonatal breathing rates among all infants, and heart rate variability (HRV) and blood pressure (BP) among girls.

Drinking was associated with reductions in HR and BP among all newborns, and reductions in the ratio of low to-high frequency HRV among boys.

These findings suggest that prenatal smoking and drinking alter newborn ANS which may presage future neurodevelopmental disorders.

Acknowledgements

The following individuals were compensated by the grants above and made significant contribution to the research and warrant recognition.

Data Coordinating & Analysis Center (DM-STAT, Inc.)

Kimberly A. Dukes, PhD, DM-STAT

Travis Baker, BS, DM-STAT

Rebecca A Young, MPH, DM-STAT

Idania Ramirez, MPH, Kaiser Permanente

Laura Spurchise, MPH, Quintiles, Inc

Derek Petersen, BS, Shire

Gregory Toland, MS, Consultant

Michael Carmen, MS, Consultant

Lisa M. Sullivan, PhD

Tara Tripp, PhD

Cheri Raffo, MPH, DM-STAT

Cindy Mai, BA, Atlantic Research Group

Jamie Collins, PhD, Brigham and Women’s Hospital

Julie Petersen, MPH, DM-STAT

Fay Robinson, MPH, DM-STAT

Patti Folan, DM-STAT

Developmental Biology & Pathology Center (Children’s Hospital Boston):

Ingrid A Holm, MD, Boston Children’s Hospital

David S Paterson, PhD; Biogen

Richard A Belliveau, BA; Broad Institute

Robin L. Haynes, PhD, Boston Children’s Hospital

Richard D Goldstein, MD; Boston Children’s Hospital

Hannah C. Kinney, MD; Simmons College

Kevin G Broadbelt, PhD; Simmons College

Kyriacos Markianos, PhD; Boston Children’s Hospital

Hanno Steen, PhD; Boston Children’s Hospital

Hoa Tran, FNP PhD; South Shore Health Care

Kristin Rivera, DO, MS; Northwell Health, Pine Manor College

Megan Minter, MS; Duke Medical School

Claire F. Maggiotto, BS; University of Buffalo, School of Medicine

Kathryn Schissler, DO; Nicklaus Children’s Hospital, FL

Theonia K. Boyd, MD; Boston Children’s Hospital

Jacob B. Cotton, BS; Boston Children’s Hospital

Rebecca D. Folkerth, MD; Boston Children’s Hospital

Perri K. Jacobs, BS; Boston Children’s Hospital

Drucilla J. Roberts, MD; Massachusetts General Hospital

Ingrid A. Holm, MD; Boston Children’s Hospital

Clinical Site Northern Plains (Sanford Research):

Whitney Adler, BA, New Horizon Farms

Elizabeth Berg, RN, University of North Dakota FAS Center & Mercy Hospital

Christa Friedrich, MS, Sanford Research

Jessica Gromer, RN, John T. Vucurevich Foundation

Margaret Jackson, BA (retired)

Luke Mack, MA, Avera Health

Bethany Norton, MA, Phoenix Children’s Hospital

Liz Swenson, RN, University of North Dakota FA Center & Mercy Hospital

Deborah Tobacco, MA, Sanford Research

Amy Willman, BS, RN, Sanford Research

Deana Around Him, Ph.D., National Congress of American Indians

Lisa Bear Robe

Mary Berdahl, RN, BA

Donna Black, AA, University of North Dakota FAS Center

Jocelyn Bratton, BS, RDMS, Sanford Health

Chaleen Brewer, BS

Melissa Berry, RD

Cathy Christophersen, MA (retired)

Sue Cote, LPN, University of North Dakota FAS Center

Kari Daron

Alexandra Draisey, BSN, RN, Regional Health

Sara Fiedler, MS

Kathy Harris, RN, BSN (retired)

Lyn Haug, RN, BSN, RNC-EFM, Rapid City Regional

Lynn Heath, BS, RDMS, Sanford Health

Ann Henkin, MS (retired)

Tara Herman, RDMS, Sanford Health

Jessica Holsworth, BS, Sanford Research

Kimberly Lucia, MS

Laura Medler, RN, Rapid City Regional

Libby Nail, MD, University of Minnesota

Amber Ogaard, BS

Debby Olson, JD (retired)

Mary Reiner, BA, CCRP (deceased)

Carol Robinson, RN, Sanford Research

Brooke Schmitt, BSN, RN, Sanford Research

Beth Shearer, MS

Monique Sioux Bob, RN, Sioux San Hospital

Lacey Stawarski, MD, Mille Lacs Band of Ojibwe

Sherri Ten Fingers, RN, Pine Ridge Indian Health Service

Rachel Thies, MD, Creighton University

Mary Thum, MS, Mayo - Rochester

Elizabeth Wheeler, MPH, Sanford Health

Lisa White Bull, MS

Steve White Hat, AAN

Amy Wilson, RN

Neva Zephier, MPH, Great Plains Tribal Chairman’s Health Board

Misti Zubke, BS, RDMS, Sanford Health

Heidi Bittner, MD, Altru Health System – Devil’s Lake & Mercy Hospital (not compensated)

Jeffrey Boyle, MD, Sanford Health (not compensated)

Donna Gaspar, RN, MA (deceased)

Cheryl Hefta, MS, RN, Spirit Lake Early Childhood Tracking

Michael McNamara, MD, Sanford Health (not compensated)

Larry Burd, PhD, University of South Dakota

Gary Hankins, MD, University of Texas Medical Branch, Galveston

Bradley B. Randall, MD, University of South Dakota School of Medicine

Mary A. Sens, MD, PhD, University of North Dakota

Peter Van Eerden, MD, University of South Dakota School of Medicine

Karna Colby, MzD, Sanford Health - Bismarck

Kent Donelan, MD, Mayo - Rochester

Don Habbe, MD, Clinical Laboratory of the Black Hills (not compensated)

Catherine Stoos, MD, Sanford Health

H Eugene Hoyme, MD, Sanford Health

Amy Mroch, MS, Sanford Health

Clinical Site South Africa (Stellenbosch University):

Erna Carstens, RN, Stellenbosch University

Lucy Brink, MSc, Stellenbosch University

Lut Geerts, MD, MRCOG, Stellenbosch University

Coen Groenewald, MD, Stellenbosch University

Colleen Wright, MD, Stellenbosch University

Greetje de Jong, MBChB, MMed, MD, Stellenbosch University

Pawel Schubert, FCPath (SA) MMed, Stellenbosch University

Shabbir Wadee, MMed, Stellenbosch University

Johan Dempers, FCFor Path (SA), Stellenbosch University

Elsie Burger, FCFor Path (SA), MMed Forens Path, Stellenbosch University

Janetta Harbron, PhD, Stellenbosch University

Physiology Assessment Center (Columbia University):

Carmen Condon, BA, Columbia University

Joseph Isler, PhD, Columbia University

Margaret C Shair, BA, Columbia University

Yvonne Sininger, PhD, University of California, Los Angeles

NIH:

Chuan-Ming Li, MD, PhD (NIDCD)

Caroline Signore, MD, MPH (NICHD)

Ken Warren, PhD (NIAAA)

Dale Hereld, PhD (NIAAA)

Marian Willinger, PhD (NICHD)

Howard J. Hoffman, MA (NIDCD)

NICHD Advisory and Safety Monitoring Board:

Elizabeth Thom, Ph.D. (chair), George Washington University

The Reverend Phillip Cato, Ph.D., Duke University

James W. Collins, Jr, MD, MPH, Northwestern University

Terry Dwyer, MD, MPH, University of Oxford

George Macones, MD, Washington University

Philip A May, Ph.D., University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Richard M. Pauli, MD, PhD, University of Wisconsin – Madison

Raymond W. Redline, MD, University Hospitals Case Medical Center

Michael Varner, MD, University of Utah Health Sciences Center

Statement of financial support

This research was supported by grants UH3OD023279, U01HD055154, U01HD045935, U01HD055155, and U01AA016501, issued by the Office of the Director, National Institutes of Health of the National Institutes of Health, National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, and the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders. Ayesha Sania is supported by UH3OD023279–05S1, re-entry supplement from Office of the Director, NIH, and Office of Research on Women Health (ORWH). The opinions expressed in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health, the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Development, the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, or the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Category of study: Population Study

Consent Statement: Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. Ethical approval was obtained from Stellenbosch University, Avera Health, Sanford Health, the Indian Health Service and from participating Tribal Nations.

References

- 1.Handmaker NS et al. Impact of Alcohol Exposure after Pregnancy Recognition on Ultrasonographic Fetal Growth Measures. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research 30, 892–898 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Scheffers-van Schayck T, Tuithof M, Otten R, Engels R & Kleinjan M Smoking Behavior of Women before, During, and after Pregnancy: Indicators of Smoking, Quitting, and Relapse. European Addiction Research 25, 132–144 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Popova S, Lange S, Probst C, Gmel G & Rehm J Estimation of National, Regional, and Global Prevalence of Alcohol Use During Pregnancy and Fetal Alcohol Syndrome: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Lancet Glob Health 5, e290–e299 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lange S, Probst C, Rehm J & Popova S National, Regional, and Global Prevalence of Smoking During Pregnancy in the General Population: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Lancet Glob Health 6, e769–e776 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Elliott AJ et al. Concurrent Prenatal Drinking and Smoking Increases Risk for Sids: Safe Passage Study Report. EClinicalMedicine 19, 100247 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hamulka J, Zielinska MA & Chadzynska K The Combined Effects of Alcohol and Tobacco Use During Pregnancy on Birth Outcomes. Rocz Panstw Zakl Hig 69, 45–54 (2018). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kesmodel U, Wisborg K, Olsen SF, Henriksen TB & Secher NJ Moderate Alcohol Intake During Pregnancy and the Risk of Stillbirth and Death in the First Year of Life. Am J Epidemiol 155, 305–312 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fifer WP, Fingers ST, Youngman M, Gomez-Gribben E & Myers MM Effects of Alcohol and Smoking During Pregnancy on Infant Autonomic Control. Dev Psychobiol 51, 234–242 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lucchini M et al. Effects of Prenatal Exposure to Alcohol and Smoking on Fetal Heart Rate and Movement Regulation, under Review Front. Physiol. - Autonomic Neuroscience. Front Physiol - Autonomic Neuroscience (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shuffrey LC et al. Association between Prenatal Exposure to Alcohol and Tobacco and Neonatal Brain Activity: Results from the Safe Passage Study. JAMA Netw Open 3, e204714 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Flak AL et al. The Association of Mild, Moderate, and Binge Prenatal Alcohol Exposure and Child Neuropsychological Outcomes: A Meta-Analysis. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 38, 214–226 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Julvez J et al. Maternal Smoking Habits and Cognitive Development of Children at Age 4 Years in a Population-Based Birth Cohort. Int J Epidemiol 36, 825–832 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Manzo-Avalos S & Saavedra-Molina A Cellular and Mitochondrial Effects of Alcohol Consumption. Int J Environ Res Public Health 7, 4281–4304 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brocardo PS, Gil-Mohapel J & Christie BR The Role of Oxidative Stress in Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders. Brain Research Reviews 67, 209–225 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jarmasz JS, Basalah DA, Chudley AE & Del Bigio MR Human Brain Abnormalities Associated with Prenatal Alcohol Exposure and Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 76, 813–833 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cohen G et al. Perinatal Exposure to Nicotine Causes Deficits Associated with a Loss of Nicotinic Receptor Function. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 102, 3817–3821 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Philips EM et al. Changes in Parental Smoking During Pregnancy and Risks of Adverse Birth Outcomes and Childhood Overweight in Europe and North America: An Individual Participant Data Meta-Analysis of 229,000 Singleton Births. PLoS Med 17, e1003182–e1003182 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mamluk L et al. Evidence of Detrimental Effects of Prenatal Alcohol Exposure on Offspring Birthweight and Neurodevelopment from a Systematic Review of Quasi-Experimental Studies. International Journal of Epidemiology 49, 1972–1995 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Musser ED et al. Emotion Regulation Via the Autonomic Nervous System in Children with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (Adhd). J Abnorm Child Psychol 39, 841–852 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grzadzinski R et al. Pre-Symptomatic Intervention for Autism Spectrum Disorder (Asd): Defining a Research Agenda. Journal of Neurodevelopmental Disorders 13, 49 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Duncan JR et al. The Effect of Maternal Smoking and Drinking During Pregnancy Upon (3)H-Nicotine Receptor Brainstem Binding in Infants Dying of the Sudden Infant Death Syndrome: Initial Observations in a High Risk Population. Brain pathology (Zurich, Switzerland) 18, 21–31 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kinney HC, Richerson GB, Dymecki SM, Darnall RA & Nattie EE The Brainstem and Serotonin in the Sudden Infant Death Syndrome. Annu Rev Pathol 4, 517–550 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vivekanandarajah A et al. Nicotinic Receptors in the Brainstem Ascending Arousal System in Sids with Analysis of Pre-Natal Exposures to Maternal Smoking and Alcohol in High-Risk Populations of the Safe Passage Study. Front Neurol 12, 636668–636668 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schechtman VL et al. Dynamic Analysis of Cardiac R-R Intervals in Normal Infants and in Infants Who Subsequently Succumbed to the Sudden Infant Death Syndrome. Pediatric research 31, 606–612 (1992). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schechtman VL et al. Heart Rate Variation in Normal Infants and Victims of the Sudden Infant Death Syndrome. Early Hum Dev 19, 167–181 (1989). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schechtman VL, Harper RM, Wilson AJ & Southall DP Sleep Apnea in Infants Who Succumb to the Sudden Infant Death Syndrome. Pediatrics 87, 841–846 (1991). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kluge KA et al. Spectral Analysis Assessment of Respiratory Sinus Arrhythmia in Normal Infants and Infants Who Subsequently Died of Sudden Infant Death Syndrome. Pediatric research 24, 677–682 (1988). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kahn A et al. Sleep and Cardiorespiratory Characteristics of Infant Victims of Sudden Death: A Prospective Case-Control Study. Sleep 15, 287–292 (1992). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kahn A et al. Sudden Infant Deaths: From Epidemiology to Physiology. Forensic science international 130 Suppl, S8–20 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sahni R, Fifer WP & Myers MM Identifying Infants at Risk for Sudden Infant Death Syndrome. Current opinion in pediatrics 19, 145–149 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Myers MM, Burtchen N, Retamar MO, Lucchini M & Fifer WP in Sids Sudden Infant and Early Childhood Death: The Past, the Present and the Future (Duncan JR & Byard RW eds.) (2018). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Horne RSC Cardiovascular Autonomic Dysfunction in Sudden Infant Death Syndrome. Clin Auton Res 28, 535–543 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zeskind PS & Gingras JL Maternal Cigarette-Smoking During Pregnancy Disrupts Rhythms in Fetal Heart Rate. Journal of Pediatric Psychology 31, 5–14 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pini N, Lucchini M, Fifer WP, Myers MM & Signorini MG in 2018 40th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society (EMBC). 5874–5877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dukes KA et al. The Safe Passage Study: Design, Methods, Recruitment, and Follow-up Approach. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol 28, 455–465 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dukes K et al. A Modified Timeline Followback Assessment to Capture Alcohol Exposure in Pregnant Women: Application in the Safe Passage Study. Alcohol 62, 17–27 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sania A et al. The K Nearest Neighbor Algorithm for Imputation of Missing Longitudinal Prenatal Alcohol Data. Research Square (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pini N et al. Cluster Analysis of Alcohol Consumption During Pregnancy in the Safe Passage Study. Annu Int Conf IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc 2019, 1338–1341 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Myers MM et al. Cardiorespiratory Physiology in the Safe Passage Study: Protocol, Methods and Normative Values in Unexposed Infants. Acta Paediatr 106, 1260–1272 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Isler JR, Thai T, Myers MM & Fifer WP An Automated Method for Coding Sleep States in Human Infants Based on Respiratory Rate Variability. Dev Psychobiol 58, 1108–1115 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Harper RM, Schechtman VL & Kluge KA Machine Classification of Infant Sleep State Using Cardiorespiratory Measures. Electroencephalography and clinical neurophysiology 67, 379–387 (1987). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Malik M, B. J. a. C. J. Heart Rate Variability: Standards of Measurement, Physiological Interpretation and Clinical Use. Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology and the North American Society of Pacing and Electrophysiology. Circulation 93, 1043–1065 (1996). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Blakesley RE et al. Comparisons of Methods for Multiple Hypothesis Testing in Neuropsychological Research. Neuropsychology 23, 255–264 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Greenland S Analysis Goals, Error-Cost Sensitivity, and Analysis Hacking: Essential Considerations in Hypothesis Testing and Multiple Comparisons. 35, 8–23 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rothman KJ No Adjustments Are Needed for Multiple Comparisons. Epidemiology (Cambridge, Mass) 1, 43–46 (1990). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kahn A et al. Prenatal Exposure to Cigarettes in Infants with Obstructive Sleep Apneas. Pediatrics 93, 778–783 (1994). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Coddou C, Bravo E & Eugenin J Alterations in Cholinergic Sensitivity of Respiratory Neurons Induced by Pre-Natal Nicotine: A Mechanism for Respiratory Dysfunction in Neonatal Mice. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 364, 2527–2535 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Milner AD, Rao H & Greenough A The Effects of Antenatal Smoking on Lung Function and Respiratory Symptoms in Infants and Children. Early Hum Dev 83, 707–711 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Beratis NG, Panagoulias D & Varvarigou A Increased Blood Pressure in Neonates and Infants Whose Mothers Smoked During Pregnancy. J Pediatr 128, 806–812 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Browne CA, Colditz PB & Dunster KR Infant Autonomic Function Is Altered by Maternal Smoking During Pregnancy. Early Hum Dev 59, 209–218 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Eckberg DL Sympathovagal Balance: A Critical Appraisal. Circulation 96, 3224–3232 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sheinkopf SJ et al. Developmental Trajectories of Autonomic Functioning in Autism from Birth to Early Childhood. Biological psychology 142, 13–18 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nordenstam F et al. Prenatal Exposure to Snus Alters Heart Rate Variability in the Infant. Nicotine & tobacco research : official journal of the Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco 19, 797–803 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Franco P, Chabanski S, Szliwowski H, Dramaix M & Kahn A Influence of Maternal Smoking on Autonomic Nervous System in Healthy Infants. Pediatric research 47, 215–220 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Moscovis SM, Hall ST, Burns CJ, Scott RJ & Blackwell CC The Male Excess in Sudden Infant Deaths. Innate immunity 20, 24–29 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Boychuk CR, Fuller DD & Hayward LF Sex Differences in Heart Rate Variability During Sleep Following Prenatal Nicotine Exposure in Rat Pups. Behavioural Brain Research 219, 82–91 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zhang Z et al. Parental Smoking and Blood Pressure in Children and Adolescents: A National Cross-Sectional Study in China. BMC Pediatrics 19, 116 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Geerts CC et al. Tobacco Smoke Exposure of Pregnant Mothers and Blood Pressure in Their Newborns. 50, 572–578 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bakker R, Steegers EA, Mackenbach JP, Hofman A & Jaddoe VW Maternal Smoking and Blood Pressure in Different Trimesters of Pregnancy: The Generation R Study. J Hypertens 28, 2210–2218 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lewandowska M & Więckowska B The Influence of Various Smoking Categories on the Risk of Gestational Hypertension and Pre-Eclampsia. J Clin Med 9, 1743 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Killen JD, Fortmann SP, Schatzberg A, Hayward C & Varady A Onset of Major Depression During Treatment for Nicotine Dependence. Addictive behaviors 28, 461–470 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Jesse S et al. Alcohol Withdrawal Syndrome: Mechanisms, Manifestations, and Management. Acta neurologica Scandinavica 135, 4–16 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Graham H & Owen L Are There Socioeconomic Differentials in under-Reporting of Smoking in Pregnancy? Tobacco Control 12, 434–434 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Rukmani MR, Seshadri SP, Thennarasu K, Raju TR & Sathyaprabha TN Heart Rate Variability in Children with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder: A Pilot Study. Annals of Neurosciences 23, 81–88 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lucchini M, Fifer WP, Sahni R & Signorini MG Novel Heart Rate Parameters for the Assessment of Autonomic Nervous System Function in Premature Infants. Physiological Measurement 37, 1436–1446 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.