Abstract

Using a daily diary design and actigraphy sleep data across 2 weeks among 256 ethnic/racial minority adolescents (Mage = 14.72; 40% Asian, 22% Black, 38% Latinx; 2,607 days), this study investigated how previous-night sleep (duration, quality) moderated the same-day associations between ethnic/racial discrimination and stress responses (rumination, problem solving, family/peer support seeking) to predict daily well-being (mood, somatic symptoms, life satisfaction). On days when adolescents experienced greater discrimination, if they slept longer and better the previous night, adolescents engaged in greater active coping (problem solving, peer support seeking), and subsequently had better well-being. Adolescents also ruminated less when they slept longer the previous night regardless of discrimination. Findings highlight the role of sleep in helping adolescents navigate discrimination by facilitating coping processes.

Sleep is critical for healthy development across physical, behavioral, cognitive and academic, and psychosocial domains (Owens, Adolescent Sleep Working Group, & Committee on Adolescence, 2014; Shochat, Cohen-Zion, & Tzischinsky, 2014). A burgeoning body of work has identified sleep as yet another critical factor for adolescents dealing with stress (Tu, Erath, & El-Sheikh, 2015), including stress related to ethnicity and race (El-Sheikh, Tu, Saini, Fuller-Rowell, & Buckhalt, 2016; Yip, 2015). Adolescence is a period when young people interact in more complex social environments, and ethnic/racial discrimination is a common challenge in adolescents’ daily lives (Benner et al., 2018; Umaña-Taylor, 2016). Although research has just started to unpack the role of sleep in attenuating the deleterious impact of discrimination on adolescent well-being, more work is needed to understand when and how sleep operates in this process. Informed by theories of racism-related stress (Harrell, 2000) and minority child development (Garcia Coll et al., 1996; Spencer, Dupree, & Hartmann, 1997), the current study focused on adolescents’ stress responses as an underlying mechanism, investigating the extent to which sleep promotes coping to offset the negative impact of discrimination on adolescent well-being.

To our knowledge, only two existing studies have examined the mitigating role of sleep in adolescent experiences of ethnic/racial discrimination. Both studies document attenuating associations between discrimination and adolescents’ socioemotional well-being for those who had better self-reported sleep quality (Yip, 2015) and longer actigraph-recorded sleep duration (El-Sheikh et al., 2016). However, these studied focused on between-person level associations, and the daily mechanisms and processes through which sleep may buffer the impact of discrimination on well-being are yet unexplored. Using a daily diary design to disentangle temporal associations and directionality, the present study investigated: (a) whether previous-night sleep moderated the same-day associations between ethnic/racial discrimination and stress responses, and (b) whether previous-night sleep moderated the same-day mediating pathways between discrimination, stress responses, and adolescent well-being (i.e., moderated mediation).

This study employed objective measures of sleep assessed by wrist actigraphy. Adolescent sleep was captured by duration and quality (i.e., inversely indicated by wake minutes after sleep onset; WASO), as both indicators have important implications for adjustment (Dewald, Meijer, Oort, Kerkhof, & Bögels, 2010; Sadeh, 2015). We used daily associations between ethnic/racial discrimination and stress responses to capture how adolescents respond to discrimination. We also controlled for daily general stress (i.e., not specific to ethnicity/race) to investigate the unique associations between discrimination and adolescent outcomes. Adolescents’ stress responses were captured by multiple dimensions, including rumination and active coping (i.e., problem solving, family support, peer support). Adolescent well-being included both negative (negative mood, somatic symptoms) and positive (positive mood, life satisfaction) outcomes.

The current study focused on adolescents in the ninth grade purposefully. National data show that over 60% of ninth-grade high school students are not sleeping the recommended 8 hr per evening, and this rate increases over the course of high school (Kann et al., 2018). Paralleling changes in sleep deprivation, starting in the ninth grade, adolescents often experience increased diversity in their social environment and challenges in social relationships during the transition to high school. At the same time, they also tend to exhibit declines in adjustment that may persist through high school (Benner, 2011). As such, understanding how sleep helps adolescents negotiate social challenges may consequently elucidate how promoting sleep may improve adolescent adjustment during high school and beyond.

The Moderating Role of Daily Sleep for the Association Between Ethnic/Racial Discrimination and Stress Responses

Stressful events such as ethnic/racial discrimination can activate various types of stress responses among adolescents. For example, rumination or thinking repetitively about the negative experiences (Borders & Liang, 2011; Miranda, Polanco-Roman, Tsypes, & Valderrama, 2013) has been linked to poor well-being (Nolen-Hoeksema, Wisco, & Lyubomirsky, 2008). Other stress responses that take on more active forms (i.e., coping; Compas et al., 2017; Lazarus & Folkman, 1984) have been highlighted as a critical tool for individuals to maintain psychological well-being in the face of ethnic/racial discrimination (Garcia Coll et al., 1996; Harrell, 2000; Spencer et al., 1997). These coping strategies include active problem solving and eliciting social support from families and peers (Alvarez & Juang, 2010; DeGarmo, Martinez, & Charles, 2006; Liang, Alvarez, Juang, & Liang, 2007). Although the different implications of rumination versus active coping are well established, much less is known regarding factors that promote adolescents’ engagement in active coping instead of ruminatory behaviors (Umaña-Taylor, Vargas-Chanes, Garcia, & Gonzales-Backen, 2008). This type of data could identify important intervening targets for ethnic/racial minority adolescents to better navigate racism and prejudice.

The current study addressed this critical gap by examining sleep as a factor that may promote coping instead of rumination on days when adolescents experience ethnic/racial discrimination. Adequate sleep, both in quantity and quality, ensures adolescents’ cognitive functioning (de Bruin, van Run, Staaks, & Meijer, 2017), alertness and energy (Dahl, 1996), and constructive thinking (Killgore et al., 2008), all of which can facilitate problem solving instead of rumination. The benefits of adequate sleep on sociocognitive skills are also important for interpersonal functioning and relationships (Killgore et al., 2008), which could promote adolescents’ support seeking from their parents and peers when experiencing discrimination. Research has indeed documented positive associations between adolescents’ sleep (duration, quality) and coping in times of stress (Sadeh, Keinan, & Daon, 2004; van Schalkwijk, Blessinga, Willemen, Van der Werf, & Schuengel, 2015).

However, existing research has primarily focused on the between-person level associations between sleep, stress, and stress responses, without investigating the temporal directionality of these associations at a daily level. The current study addressed this gap by using a daily diary design to examine within-person associations between sleep, ethnic/racial discrimination, and stress responses. A daily diary design can more accurately capture the transactional, within-person nature of stress and responses (e.g., coping in response to a stressor; Almeida, 2005; Lazarus & Folkman, 1984). It also allows for a more nuanced investigation of the temporal associations between predictors and consequences on a daily basis (Almeida, 2005), thus informing prevention and intervention programs with levers of change in everyday life (Snippe et al., 2016). This study examined how the previous night’s sleep moderates the same-day links between discrimination and stress responses, controlling for previous-day stress responses. Importantly, the within-person associations explore how daily experiences that are either above or below an adolescent’s typical levels are associated with each other on a daily basis. As a result, all estimates are interpreted as a deviation from the adolescent’s own average. We hypothesized that on days when adolescents experience higher than their typical levels of ethnic/racial discrimination, having had longer and better (i.e., longer duration and better quality) sleep than usual on the previous night will equip adolescents with the sociocognitive resources to engage in more problem solving and social support seeking and less rumination, relative to their typical levels of stress responses. In the spirit of sensitivity analyses, we also examined alternative relations among same-day discrimination, stress responses, and sleep, in order to explore whether adolescents may sleep longer and better when they engage in more coping instead of rumination on days when they experience higher levels of ethnic/racial discrimination.

Moderated Mediation of Daily Sleep, Ethnic/Racial Discrimination, Stress Responses, and Adolescent Well-Being

In addition to the moderating effects of previous-night sleep, the current study also investigated how these moderating effects impact adolescents’ daily well-being, seeking to identify whether previous-night sleep moderated the same-day associations among discrimination, stress responses, and adolescent well-being (i.e., moderated mediation). Perceptions of ethnic/racial discrimination have been consistently linked to compromised adolescent well-being, both at the person level (Benner et al., 2018; Umaña-Taylor, 2016) and at the daily level (Seaton & Douglass, 2014; Zeiders, 2017). Research has also disentangled daily temporal associations and documented same-day associations between general stress, coping, and adolescent well-being (Kiang & Buchanan, 2014; Santiago et al., 2016). Informed by theories of racism-related stress (Harrell, 2000) and minority child development (Garcia Coll et al., 1996; Spencer et al., 1997), we explored how experiences of discrimination activate stress responses to predict adolescent well-being. These stress responses include rumination which perpetuates negative feelings (Borders & Liang, 2011), and more active forms of stress responses such as problem solving and social support seeking which may offset the negative impact of discrimination (Alvarez & Juang, 2010; DeGarmo et al., 2006; Liang et al., 2007).

Building upon the moderating effects of previous-night sleep, we hypothesized that previous-night sleep may facilitate adolescents’ engagement in coping instead of rumination, ultimately mitigating the impact of ethnic/racial discrimination on adolescent well-being. Specifically, when adolescents have the benefit of longer and better sleep on the previous night, on days when they experience higher than their typical levels of discrimination, they may engage in more coping and less rumination, resulting in less compromised well-being.

The Current Study

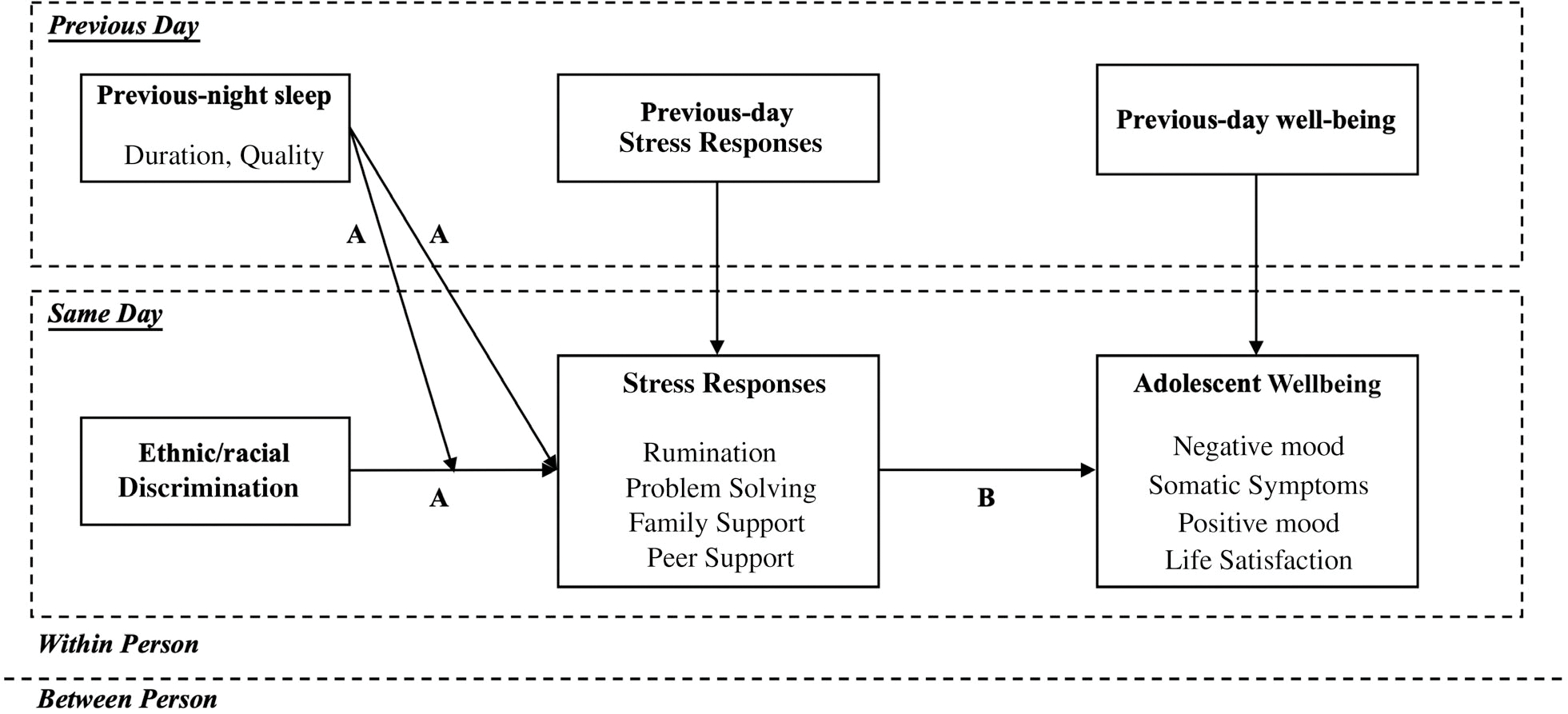

Using data from a 2-week daily diary and actigraphy project, this study examined the daily associations among adolescents’ sleep, ethnic/racial discrimination, stress responses, and well-being (see conceptual model in Figure 1). Adolescents’ sleep duration and quality were assessed by objective actigraphy data. This study had three aims. We first investigated the extent to which previous-night sleep moderated the same-day associations between ethnic/racial discrimination and stress responses (rumination, problem solving, family support, and peer support; Paths A in Figure 1). We hypothesized that on days when adolescents experience higher than their typical levels of ethnic/racial discrimination, sleeping longer and better the previous night would be associated with higher than typical levels of active stress responses (i.e., coping). We also explore alternative associations in which discrimination and stress responses interact to predict sleep that night. The second aim explored the moderating effects of previous-night sleep for the same-day mediation of discrimination, stress responses, and adolescent well-being (Paths A and B in Figure 1; sleep moderates the link between discrimination and stress responses). Building upon the hypotheses of the first aim, we expected that engaging in more coping and less rumination would be associated with better well-being. Finally, since adolescent sleep, discrimination, and well-being may differ by ethnic/racial groups (Benner et al., 2018; Yip, Wang, Mootoo, & Mipuri, in press), we investigated ethnic/racial variations in the above associations.

Figure 1.

Conceptual models testing relations among previous-night sleep, same-day ethnic/racial discrimination, stress responses, and adolescent well-being. Covariates included a standard set of daily- and person-level variables, as well as previous-day stress responses and well-being. Multilevel structural equation modeling was used to partition the variables into a within-person component and a between-person component. This study focused primarily on within-person associations. All between person variables are omitted from this figure but modeled in the analyses.

Method

Participants

Data were drawn from the first wave of a longitudinal study on daily stress and sleep. The larger project included 350 Asian, Black, and Latinx ninth graders, who provided 2-week long sleep actigraphy and daily diary data. Adolescents were recruited from five public high schools with varying levels of ethnic/racial diversity in a large urban area in the northeastern United States. The schools’ Simpson’s (1949) Diversity Index were 0.29, 0.36, 0.51, 0.55, 0.62, representing the probability that two randomly selected students were from different ethnic/racial groups (average high school diversity in the area was 0.52, SD = 0.16; New York City Department of Education, 2016). All Asian, Black, and Latinx ninth graders were invited to participate in the study. Students from other ethnic/racial groups (e.g., Non-Hispanic White) and who were diagnosed with a sleep disorder were not eligible to participate.

The current analytic sample includes 256 adolescents with valid actigraphy and diary data across 2,607 days (missing data analyses are presented in the following paragraphs). On average, participants were 14.72 years old (ranging from 13.75 to 17.40; SD = 0.54). The sample is 73% female and ethnic/racially diverse (40% Asian, 22% Black, 38% Latinx based on self-reports). The majority of the Asian adolescents reported being Chinese (77%); within the Latinx group, there were 28% Dominican, 23% Mexican, 15% Puerto Rican, and 19% South American. A majority (76%) of the sample were born in the United States (12% Asian, 67% Black, 80% Latinx; however, 83% Asian American adolescents did not report their nativity status). Among the foreignborn Black adolescents, 24% were African immigrants and 76% were Caribbean. Adolescents also reported their parents’ highest education (34% mothers and 35% fathers had a high school degree or less; 17% mothers and 9% fathers had some college education; 19% mothers and 14% fathers had a college degree or higher). The remaining adolescents reported not knowing their parents’ education (30% mothers and 42% fathers).

At the daily level, we matched previous-night sleep actigraphy data with today’s diary reports of discrimination, stress responses, and well-being to explore the study aims. Because previous-night sleep was not available on the first day of the study, the analytic data had a maximum possible total of 13 days. On average, adolescents had daily diary data for 9.32 days (SD = 3.55; 23% of the participants had all 13 days of diaries, 51% of the participants had 10 days or more, and 83% had 5 days or more). For sleep actigraphy data, adolescents had an average of 10.18 days of data (SD = 3.48; 36% of the participants had all 13 days, 70% had 10 days or more, and 90% had 5 days or more).

As with other research employing daily diary or sleep actigraphy approaches (Meltzer, Montgomery-Downs, Insana, & Walsh, 2012), missing data are common. The issue is not whether there are missing data, but whether the missing data patterns influence the results. To this end, we investigated missing data patterns with several approaches. First, 89 out of the 350 adolescents did not have valid data due to malfunctions of the actigraph units (Motionlogger micro watch by Ambulatory Monitoring, Inc., Ardsley, NY). We screened for missing not at random (MNAR) by examining whether such missingness was associated with self-reported sleep. No significant relation was identified. We then explored missing at random (MAR) by testing whether adolescent demographics were associated with missing due to actigraph malfunctions. One significant pattern emerged: girls were more likely than boys to experience actigraph malfunctions (r = .15, p < .01). This was addressed by controlling for gender in the analyses.

The remaining 261 adolescents had average 15.4% missingness (523 out of 3,393 days) in sleep actigraphy data due to less systematic reasons such as equipment loss and noncompliance. This type of missingness is common and comparable to existing actigraphy research (Meltzer et al., 2012). We screened for MNAR by examining: (a) whether previous-night sleep predicted the missingness of sleep data tonight, and (b) whether person-level average sleep was associated with the number of missing days in sleep. We also explored MAR by testing: (a) whether daily variables (i.e., days in the study, weekends vs. weekdays) predicted the missingness of sleep data today, and (b) whether demographics predicted the number of missing days in sleep. No significant associations emerged, indicating no systematic missingness in the actigraphy sleep data. As actigraphy sleep was the central focus of the study, we did not use statistical techniques to handle the missingness but included only days with valid actigraphy data in the analyses (261 adolescents across 2,870 days).

We further excluded 263 days when no daily diary data were available, resulting in an analytic sample of 256 adolescents across 2,607 days. Within the 2,607 days, there were 0%–9% missingness in primary study variables (discrimination, stress responses, well-being). We first screened for MNAR by examining: (a) whether a variable’s value on the previous day predicted its missingness today and (b) whether the person-level average of each variable was associated with the number of missing days. No significant associations emerged for any study variable, justifying the use of full information maximum likelihood (FIML) to handle missingness in the analyses. We then explored MAR by testing: (a) whether daily characteristics (i.e., day of the study, weekend vs. weekdays) predicted missingness in each variable, and (b) whether demographics were associated with the number of missing days in each variable. Two significant patterns emerged: missingness in discrimination, stress responses, and adolescent well-being was more likely as the study progressed (β = −.07 to −.09, p < .001) and Asian adolescents had more days of valid data than Black and Latinx adolescents (r = .21, p < .01). As such, day of the study and ethnicity/race were included as covariates in the analyses.

Procedures

Consent forms were mailed to students’ home addresses and also placed in students’ school mailboxes. The response rate ranged from 6% to 31%, necessitating data collection across four successive cohorts (n = 90, 102, 94, and 64, respectively). The four cohorts did not differ on gender, age, race, or mother’s and father’s education level. Within each cohort, adolescents first completed an online demographic survey. Next, they were given a wrist actigraph along with a data-enabled Android tablet to complete the online daily diary surveys hosted by Qualtrics. The research team instructed participants how to wear the actigraph (e.g., continuously on the nondominant hand) and respond to the daily surveys (e.g., when and how to access the surveys). For the next 14 days, participants wore the wrist actigraph for sleep assessment and completed a daily diary survey before going to bed every night. Diary compliance was monitored daily and participants received a daily message from the research team. Participants who failed to complete a daily survey were reminded to complete their daily surveys. Participants who completed the survey received a message of encouragement to continue their participation. On the last day of the 2-week session, participants completed a final demographic survey, met with the research team to return materials, and were compensated $20 for their time. Qualtrics includes a time stamp for each survey response and this was used to match daily surveys with actigraph data.

Measures

Descriptive statistics for all primary variables are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics of Primary Study Variables

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||||

| Correlations (within-person) | |||||||||||

| 1. Previous-night sleep duration | |||||||||||

| 2. Previous-night sleep WASO | .18*** | ||||||||||

| 3. Same-day discrimination | .02 | .03 | |||||||||

| 4. Same-day rumination | −.10*** | −.06* | .15*** | ||||||||

| 5. Same-day problem solving | −.06* | −.05 | .11** | .56*** | |||||||

| 6. Same-day family support | .01 | −.01 | .06 | −.05 | .03 | ||||||

| 7. Same-day peer support | −.07* | −.01 | .07* | .04 | .05 | .41*** | |||||

| 8. Same-day negative mood | −.11*** | −.03 | .06 | .48*** | .26*** | −.07* | .04 | ||||

| 9. Same-day somatic symptoms | −.14*** | .04 | .21*** | .18*** | .14*** | .04 | .06* | .19*** | |||

| 10. Same-day positive mood | .04 | .02 | −.07 | −.19*** | −.08** | .10** | .08** | −.22*** | −.10*** | ||

| 11. Same-day life satisfaction | .04 | .04 | −.06* | −.26*** | −.08* | .11** | .06* | −.29*** | −.06* | .36*** | |

| Descriptives (raw scores) | |||||||||||

| N (number of participants) | 256 | 256 | 254 | 254 | 254 | 254 | 254 | 254 | 254 | 254 | 254 |

| n (number of days) | 2,607 | 2,607 | 2,320 | 2,334 | 2,334 | 2,326 | 2,323 | 2,332 | 2,329 | 2,332 | 2,327 |

| M | 7.24 | 0.45 | 1.05 | 1.28 | 1.33 | 1.83 | 1.89 | 3.08 | 3.45 | 1.42 | 1.61 |

| SD | 1.57 | 0.41 | 0.21 | 0.50 | 0.51 | 0.79 | 0.77 | 1.11 | 0.95 | 0.56 | 0.78 |

| Minimum | 0.25 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Maximum | 16.93 | 3.65 | 2.00 | 3.00 | 3.00 | 3.00 | 3.00 | 5.00 | 4.00 | 5.00 | 5.00 |

| Skewness | 0.29 | 2.28 | 5.40 | 1.85 | 1.52 | 0.31 | 0.19 | 1.77 | 1.93 | −0.01 | 0.03 |

| Kurtosis | 2.08 | 7.88 | 32.07 | 2.73 | 1.54 | −1.36 | −1.35 | 3.16 | 3.96 | −0.71 | −0.73 |

Note. All estimates were obtained from Mplus, with missing data handled by full information maximum likelihood. Correlations among variables were obtained from within-person estimates. All descriptives (N, n, M, SD, minimum, maximum, skewness, and kurtosis) were based on raw data without distinguishing within- and between-person components. Sleep duration and wake minutes after sleep onset (WASO) were measured in hours.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Daily Sleep

Daily sleep was assessed by the Motionlogger micro watch (Ambulatory Monitoring, Inc.). Wrist actigraphy uses an accelerometer to assess sleep and wake states in 1-min epochs. Data were analyzed using Sadeh algorithm (Sadeh, 2011) and corroborated against self-reported daily sleep onset and offset times. The first 20 files were scored by three research assistants and discrepancies were discussed to obtain an initial interrater reliability of ICC = .85–.90. Thereafter, every 10th file was scored by two research assistants and the interrater reliability for these overlapping files remained good (MICC = .92, SD = 0.07). As recommended by previous research, this study used both duration and quality indices to capture the multifaceted nature of sleep (Sadeh, 2015). Sleep duration was assessed by the number of minutes adolescents actually slept between when they had fallen asleep to when they woke up. Sleep quality was assessed by WASO, the number of minutes adolescents were awake after they fall asleep. Higher WASO indicated poorer sleep quality. For ease of interpretation, duration and WASO were divided by 60 to convert minutes into hours.

Research has validated the use of actigraph to assess sleep at the person level (Sadeh, 2015), and daily actigraphy measures of sleep duration and WASO have been validated through linkages with same-day stress and mood (Doane & Thurston, 2014; Kouros & El-Sheikh, 2015). The 2-week long actigraphy data can reliably capture adolescents’ average sleep (previous research suggests 5 days or more; Acebo et al., 1999). Although data from self-reported sleep (Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index; Buysse, Reynolds, Monk, Berman, & Kupfer, 1989) are not reported in this study, they were used as a validity check. Self-reported sleep duration had a correlation of r = .28, p < .001 with the actigraphy sleep duration, similar to existing research (Short, Gradisar, Lack, & Wright, 2012). Self-reported sleep disturbance (e.g., trouble sleeping due to bad dreams) was also significantly associated with actigraphy WASO (r = .15, p < .05). The average sleep duration in our study (7.24 hr per night; 6.89 hr on school days, 8.08 hr on weekends) was similar to other samples with similar school start times (e.g., 6.72–7.02 hr on school days when school starts at 8:00 or later; Nahmod et al., 2019). School start times were 8:15, 8:20, 8:30, 8:46, and 8:00/9:15 mixed at the five participating schools, respectively.

We also screened for outliers, and 1% of sleep duration and 2% of WASO fell outside of the 3 SDs range. The sleep duration outliers followed a consistent pattern: short sleep duration (< 2 hr) all occurred on weekdays (all 7 days), and long sleep duration (> 12 hr) mostly occurred on weekends or when participants were not in school (15 of the 16 days).

Daily Ethnic/Racial Discrimination

A six-item measure was developed to assess daily experiences of ethnic/racial discrimination. Adolescents rated the extent to which each item was a problem each day (“I was treated unfairly because of my race/ethnicity,” “I felt stress because of my race/ethnicity,” “others treated me poorly because of my race/ethnicity,” “I was teased because of my race/ethnicity,” “I felt uncomfortable because of my race/ethnicity,” “I felt unsafe because of my race/ethnicity”) on a 3-point scale ranging from 0 (did not happen/was not a problem today) to 2 (very much a problem today). Although there is some disagreement about whether to report internal consistency statistics for discrimination measures (Lilienfeld, 2017), they are reported here given the newly developed nature of the measure. This measure had satisfactory internal consistency at both the within- (ω = .90) and between-person level (ω = .99; Geldhof, Preacher, & Zyphur, 2014). Furthermore, the intraclass correlation (ICC = .56) showed that there was considerable variation in ethnic/racial discrimination both at the within- and between-person levels. At the daily level, discrimination was correlated with negative mood, somatic symptoms, and life satisfaction (see Table 1), supporting criterion-related validity. Consistent with other research employing daily diary methods (Goosby, Cheadle, Strong-Bak, Roth, & Nelson, 2018; Seaton & Douglass, 2014; Zeiders, 2017), daily discrimination was relatively low frequency. On average, adolescents reported a total of 1.12 incidents (SD = 2.90) over the 2 weeks (of note, 71% of the sample did not report experiences of discrimination). The person-level mean of daily discrimination was 0.05 (SD = 0.21; 3% outliers outside 3 SDs).

Daily Stress Responses

There were four indicators for adolescents’ responses to stress: rumination, problem solving, family support, and peer support. Rumination and problem solving were assessed by items adapted from the Children’s Response Styles Questionnaire (Abela, Aydin, & Auerbach, 2007). The rumination scale included four items focused on negative feelings (“I thought ‘why can’t I handle things better’?,” “I thought about all of my failures, faults, and mistakes,” “I thought about how angry I was with myself,” and “I thought ‘I’m disappointing my friends, family, or teachers’”). The problem-solving scale included three items on strategies to overcome stresses (“I tried to find something good in the situation or something I had learned,” “I reminded myself that this feeling would go away,” and “I thought of a way to make my problem better”). Using a 3-point scale ranging from 0 (no) to 2 (a lot of the time), adolescents rated the extent to which they engaged in each item on a given day. Validating the subscales, greater rumination and less problem solving have been linked to adolescents’ development of depression over time (Hilt, McLaughlin, & Nolen-Hoeksema, 2010).

Family support and peer support were each assessed by two items adapted from the social support subscale of coping responses from Wills (1986). The two items were “I was able to talk about how I felt,” and “I got emotional support and understanding.” Using a 3-point scale ranging from 0 (not true at all) to 2 (very true), adolescents rated the two items when interacting with family members and friends/peers. Both family and peer support have been linked with better socioemotional outcomes among adolescents (Wills, Resko, Ainette, & Mendoza, 2004). The four stress response variables showed satisfactory internal consistency at the within-person level (ωs = .75–.92) and the between-person level (ωs = .96–.99). Intraclass correlations (ICCs = .57–.71) showed that there was considerable variation in adolescents’ stress responses both at the within- and between-person levels.

Daily Well-Being

Daily well-being was assessed by negative (negative mood, somatic symptoms) and positive outcomes (positive mood, life satisfaction). Adolescents rated their daily mood using a short form of the Profile of Mood States (McNair, Lorr, & Droppleman, 1971). The items included negative mood (i.e., sad, hopeless, discouraged, blue), anxious mood (i.e., anxious, nervous, unable to concentrate, on edge), and angry mood (i.e., angry, resentful, grouchy, annoyed). We also developed a corresponding measure of positive mood (i.e., happy, calm, joyful, excited) used in daily diary research (Yip, 2016). Adolescents rated each item on a 5-point scale ranging from 0 (not at all) to 4 (extremely). We created a negative mood indicator by averaging negative, anxious, and angry mood items, as well as a positive mood indicator. Somatic symptoms were assessed by six items from the Index of Somatic Symptoms (Walker, Garber, Smith, Van Slyke, & Claar, 2001). Adolescents rated their daily symptoms (headache, nausea, tiredness, sore muscles, stomachache, feeling weak) on a 4-point scale ranging from 1 (not at all) to 4 (a whole lot). Life satisfaction was assessed by three items (“I wished I had a different kind of life,” “I was happy with my life,” and “I felt my life was working out as well as I could hope”; Lippman et al., 2014). Adolescents rated each item on a 5-point scale ranging from 0 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree). All well-being indicators showed satisfactory internal consistency at the within- (ωs = .65–.81) and between-person levels (ωs = .84–.97). Intraclass correlations (ICCs = .60–.70) indicated that there was considerable variation in adolescents well-being both at the within- and between-person levels.

Covariates

At the daily level, we controlled for the day of the study (i.e., 1–14), the day of the week (0 = weekday, 1 = weekend), whether the target adolescent was absent from school (1 = yes, 0 = no), how much time they spent with their families and friends (0 = none to 5 = more than 4 hr), whether they took a nap (1 = yes, 0 = no), and the use of caffeinated beverages (coffee, tea, chocolate drinks, soda, and energy drinks) on the previous day (0 = none, 4 = 7 or more beverages). We also controlled for general (i.e., non-race-related) stress in family, school, and neighborhood settings (e.g., “I did not feel safe at school or in my community”; eight items; 0 = not a problem today, 2 = very much a problem today; ω = .79 at the within-person level and .98 at the between-person level). Prior day controls (i.e., prior day stress responses, prior day well-being) were also included. At the person level, we controlled for adolescent age, gender (0 = male, 1 = female), ethnicity/race (a dichotomous variable indicating 1 = Asian 0 = not Asian, and another indicating 1 = Black, 0 = not Black; Latinx was the reference group), and depressive symptoms (Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale; Radloff, 1977).

Analysis Plan

All analyses were conducted in the multilevel structural equation modeling framework in Mplus 8 (Muthen & Muthén, 1998–2018). MSEM estimates within- and between-person associations separately, thus reducing bias due to conflation of effects across levels by traditional multilevel modeling methods (Preacher, Zhang, & Zyphur, 2010). The current study focuses on within-person associations, in order to disentangle the timing of daily variables. All models used maximum likelihood estimation with robust standard errors (MLR), which provides estimations of standard errors that are robust to nonnormal data (Yuan & Bentler, 2000). Missing data (0%–9%) were handled by FIML, a preferred procedure with nonnormal data (Yuan, Yang-Wallentin, & Bentler, 2012).

Our first set of analyses examined the moderating effects of previous-night sleep for same-day associations between ethnic/racial discrimination and stress responses (Paths A in Figure 1). The two sleep indicators (duration, quality) and the four stress response variables (rumination, problem solving, family support, peer support) were tested simultaneously in the same model. We first examined the main effects of previous-night sleep (duration, quality) and same-day discrimination, and then introduced the interaction terms between sleep and discrimination. Both sleep and discrimination variables were centered by their person means, and the interaction terms were created using centered sleep and discrimination variables. All endogenous variables were decomposed into the within- and between-person components by default. Since preliminary analyses showed that there were no significant variances in the random slopes (variances = .000–.14, ps = .36–.96), only fixed effects were estimated for the slopes of stress responses on discrimination, sleep, and their interactions. For each stress response variable, we controlled for previous-day level and a standard set of daily covariates (day of the study, day of the week, school absence, time spent with family, time spent with friends, nap, previous day caffeine intake, and general stress) at the within-person level, as well as a standard set of person-level covariates (age, gender, ethnicity/race, depressive symptoms) at the between-person level. When a significant interaction emerged, we conducted simple slope analyses (Aiken & West, 1991) to examine the extent to which discrimination was associated with stress responses when adolescents had various levels of sleep on a previous night. We also explored the range of previous-night sleep within which the association between discrimination and stress responses was significant (i.e., regions of significance; Preacher & Curran, 2006). This was done using the LOOP function in Mplus. To explore alternative mechanisms, we also explored interaction effects between discrimination and stress responses for sleep that night.

Our second set of analyses examined moderated mediation among previous-night sleep, same-day discrimination, stress responses, and adolescent well-being (Paths A and B in Figure 1). Similar to the first set of analyses, the two sleep indicators (duration, quality) and the four stress response variables (rumination, problem solving, family support, peer support) were tested simultaneously in the same model. Negative well-being was estimated as a latent variable by negative mood and somatic symptoms. Positive well-being was estimated as a latent variable by positive mood and life satisfaction. In each model, we first examined direct paths among study variables and then estimated the indirect effects depending on the significance of the sleep–discrimination interaction. If the sleep–discrimination interaction was not significant, we removed the interaction term and estimated mediation (indirect effects) among discrimination, stress responses, and well-being. If the sleep–discrimination interaction was significant, we estimated the indirect effects at varying levels of previous-night sleep. Confidence intervals of the indirect effects were estimated based on Monte Carlo simulation of the indirect effects’ sampling distribution, using R software (codes available at http://www.quantpsyc.org; Preacher et al., 2010). In each model, we controlled for previous-day stress responses and well-being, as well as the standard set of daily- and person-level covariates.

The third set of analyses investigated ethnic/racial variations in the previous models (103 Asian, 57 Black, and 96 Latinx adolescents). Using multiple group analyses, we compared models that constrained all primary paths equal across ethnic/racial groups to baseline models that freely estimated all paths across groups. If the fully constrained model fits the data significantly worse than the freely estimated model, we then constrained the model paths one at a time to identify the exact group differences. Model comparisons used Satorra–Bentler scaled chi-square tests to adjust for the use of the MLR estimator (Satorra & Bentler, 2001).

Results

Moderating Effects of Previous-Night Sleep for Same-Day Associations Between Discrimination and Stress Responses

Results for this set of analyses (Paths A in Figure 1) are shown in Table 2. We first examined the main effects of previous-night sleep and same-day discrimination on stress responses (see the left column “Main Effects” in Table 2). Controlling for previous-day stress responses, on the days when adolescents reported greater discrimination, they also reported high levels of seeking peer support. Discrimination was not significantly associated with rumination, problem solving, or family support. We also observed a negative association between sleep duration and rumination such that when adolescents slept longer on the previous night, they reported lower levels of rumination.

Table 2.

Moderating Effects of Previous-Night Sleep on Same-Day Associations Between Ethnic/Racial Discrimination and Stress Responses (Paths A in Figure 1)

| Predicting stress responses |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Main effects |

Interaction effects |

|||||

| B | SE | β | B | SE | β | |

|

| ||||||

| Predicting rumination | ||||||

| Previous-day rumination | .12 | .03 | .17*** | .12 | .03 | .16*** |

| Previous-night sleep duration | −.01 | .01 | −.05* | −.01 | .01 | −.05* |

| Previous-night sleep WASO | −.03 | .02 | −.03 | −.04 | .02 | −.03 |

| Same-day discrimination | .07 | .04 | .03 | .08 | .05 | .03** |

| Discrimination × Sleep Duration | .04 | .03 | .03 | |||

| Discrimination × Sleep WASO | −.21 | .16 | −.03 | |||

| Predicting problem solving | ||||||

| Previous-day problem solving | .16 | .03 | .23*** | .16 | .03 | .23*** |

| Previous-night sleep duration | −.01 | .01 | −.02 | −.01 | .01 | −.02 |

| Previous-night sleep WASO | −.02 | .02 | −.02 | −.03 | .02 | −.03 |

| Same-day discrimination | .06 | .06 | .02 | .08 | .06 | .03 |

| Discrimination × Sleep Duration | .09 | .04 | .06* | |||

| Discrimination × Sleep WASO | −.47 | .13 | −.07*** | |||

| Predicting family support | ||||||

| Previous-day family support | .19 | .04 | .33*** | .19 | .04 | .32*** |

| Previous-night sleep duration | .00 | .01 | .00 | .00 | .01 | .00 |

| Previous-night sleep WASO | −.03 | .03 | −.02 | −.02 | .03 | −.01 |

| Same-day discrimination | .13 | .10 | .04 | .11 | .11 | .03 |

| Discrimination × Sleep Duration | −.04 | .05 | −.02 | |||

| Discrimination × Sleep WASO | .31 | .22 | .04 | |||

| Predicting peer support | ||||||

| Previous-day peer support | .17 | .03 | .26*** | .17 | .03 | .26*** |

| Previous-night sleep duration | −.00 | .01 | −.01 | −.00 | .01 | −.01 |

| Previous-night sleep WASO | .01 | .04 | .01 | .01 | .04 | .01 |

| Same-day discrimination | .19 | .07 | .05** | .21 | .07 | .06** |

| Discrimination × Sleep Duration | .07 | .05 | .04 | |||

| Discrimination × Sleep WASO | −.39 | .19 | −.04* | |||

Note. All stress response variables were tested simultaneously in the same model. Covariates included a standard set of daily- and person-level variables, as well as previous-day stress responses. The model testing for main effects showed a good model fit, χ2(18) = 27.07, p = .08; CFI = .998, RMSEA = .014, SRMR = .015 for within and .024 for between. The model testing for interaction effects also showed a good model fit, χ2(18) = 27.40, p = .07; CFI = .998, RMSEA = .014, SRMR = .014 for within and .025 for between. CFI = comparative fit index; RMSEA = root mean square error of approximation; SRMR = standardized root mean square residual; WASO = wake minutes after sleep onset.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

We then examined the moderating effects of previous-night sleep for the same-day associations between ethnic/racial discrimination and each of the four stress response variables, controlling for previous-day stress responses (see the right column “Interaction Effects” in Table 2). When rumination and family support were the target stress response variables, no significant interactions emerged between previous-night sleep (WASO, duration) and discrimination.

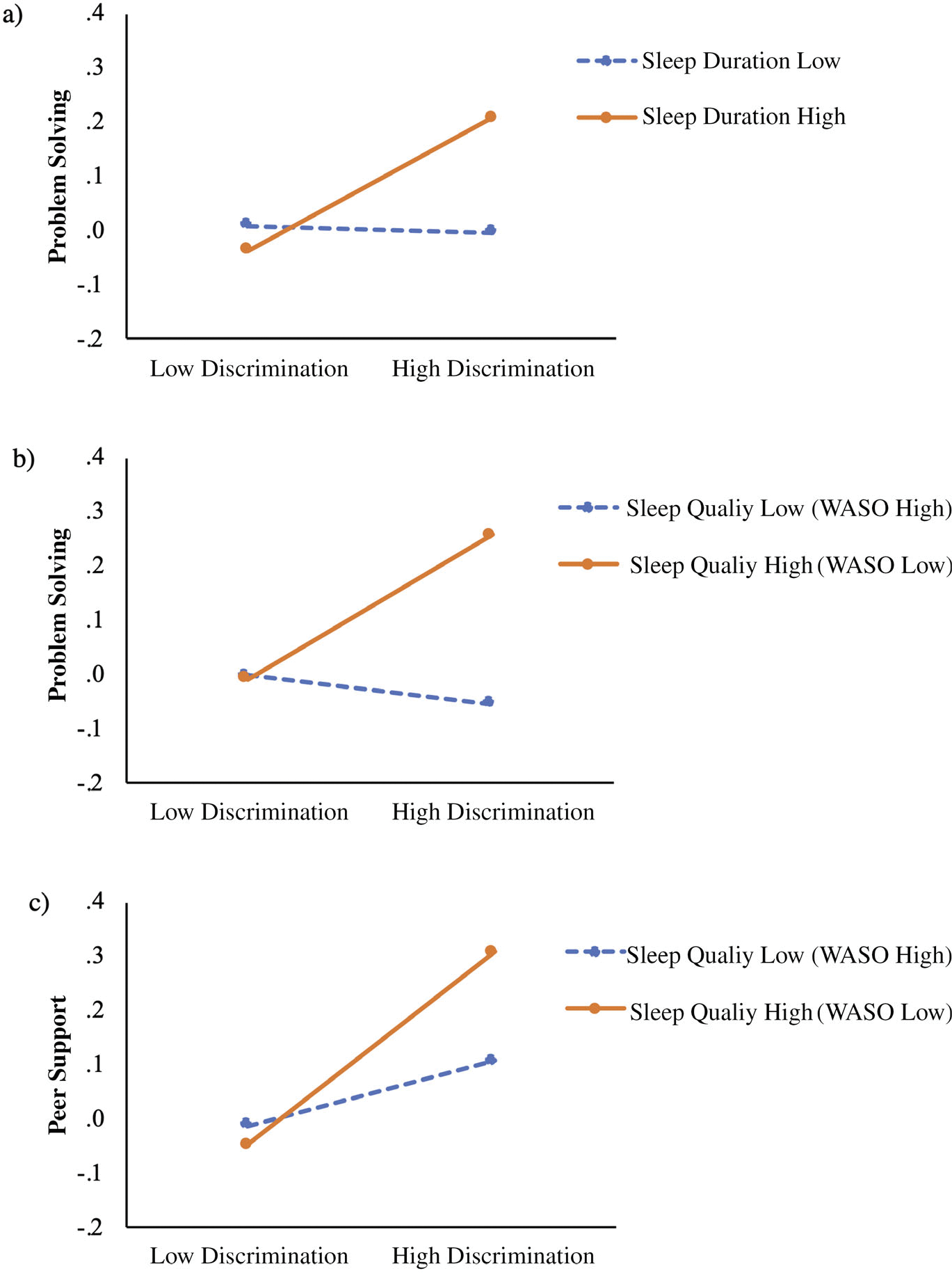

When problem solving was the target coping variable, we observed a significant interaction between previous-night sleep duration and discrimination, and a significant interaction between previous-night sleep quality (i.e., WASO) and discrimination. Simple slope analyses examined the extent to which same-day discrimination was associated with problem solving at varying levels of previous-night sleep. Regarding sleep duration (see Figure 2a), when adolescents had longer sleep duration the previous night (i.e., duration was one standard deviation above the person average), experiences of discrimination were associated with more problem solving (unstandardized coefficient B = .20, SE = .06, p < .001). In contrast, this association was not significant (B = −.05, SE = .10, p = .64) when adolescents had shorter sleep duration the previous night (i.e., duration was one standard deviation below the person average). Analyses for regions of significance (see online supplement Figure S1a) showed that when adolescents’ sleep duration on the previous night was at least 0.40 hr above their average (31% of all nights), the association between discrimination and problem solving was significant. In contrast, when adolescents’ sleep duration on the previous night was < 0.40 hr above their average, the association between discrimination and problem solving was not significant.

Figure 2.

Moderating effects of previous-night sleep on same-day associations between ethnic/racial discrimination and coping. High versus low sleep duration were one standard deviation above versus below the person average. High versus low sleep quality was one standard deviation below versus above the person average of wake minutes after sleep onset (WASO). Due to the relatively low frequency of discrimination and to avoid presenting theoretical values that were not present in the data, low discrimination was one standard deviation below the person average, whereas high discrimination was one unit above the person average. Solid lines indicate significant relations, whereas dash lines indicate nonsignificant relations.

For the interaction between previous-night sleep quality and discrimination on problem solving (see Figure 2b), when adolescents had better sleep the previous night (i.e., less time awake; WASO was one standard deviation below the person average), greater discrimination was associated with more problem solving (B = .22, SE = .07, p < .001). In contrast, this association was not significant (B =−.07, SE = .07, p = .35) when adolescents had poorer sleep the previous night (i.e., WASO was one standard deviation above the person average). Analyses for regions of significance (see online supplement Figure S1b) showed that when adolescents’ WASO the previous night was less than 0.10 hr below their average level (36% of all nights), the association between discrimination and problem solving was significant. In contrast, when adolescents’ WASO the previous night was more than 0.10 hr below their average level, the association between discrimination and problem solving was not significant.

When peer support was the target coping variable, we observed a significant interaction between previous-night sleep WASO and discrimination. Simple slope analyses (see Figure 2c) showed that when adolescents had better sleep the previous night, discrimination was associated with seeking more peer support (B = .32, SE = .10, p = .001). In contrast, when adolescents had poorer sleep the previous night, discrimination was not associated with peer support (B = .09, SE = .09, p = .32). Analyses for regions of significance (see online supplement Figure S1c) showed that when adolescents’ WASO the previous night was less than 0.10 hr above their average (75% of all nights), the association between discrimination and peer support was significant. In contrast, when adolescents’ WASO the previous night was more than 0.10 hr above their average, the association between discrimination and peer support was not significant.

We also explored alternative relations among adolescents’ experiences of discrimination, stress responses, and sleep that night. We tested separate interaction effects between discrimination and each of the four stress response variables. Adolescents’ sleep duration and quality on the previous night were included as covariates. No significant interactions between discrimination and stress responses were observed for either sleep duration or WASO (ps = .34–.93). Estimates from the sensitivity analyses are reported in online supplement Table S1. These findings provided further support for the moderating effects of previous-night sleep on the same-day associations between discrimination and stress responses.

Moderated Mediation Among Previous-Night Sleep, Same-Day Discrimination, Stress Responses, and Adolescent Well-Being

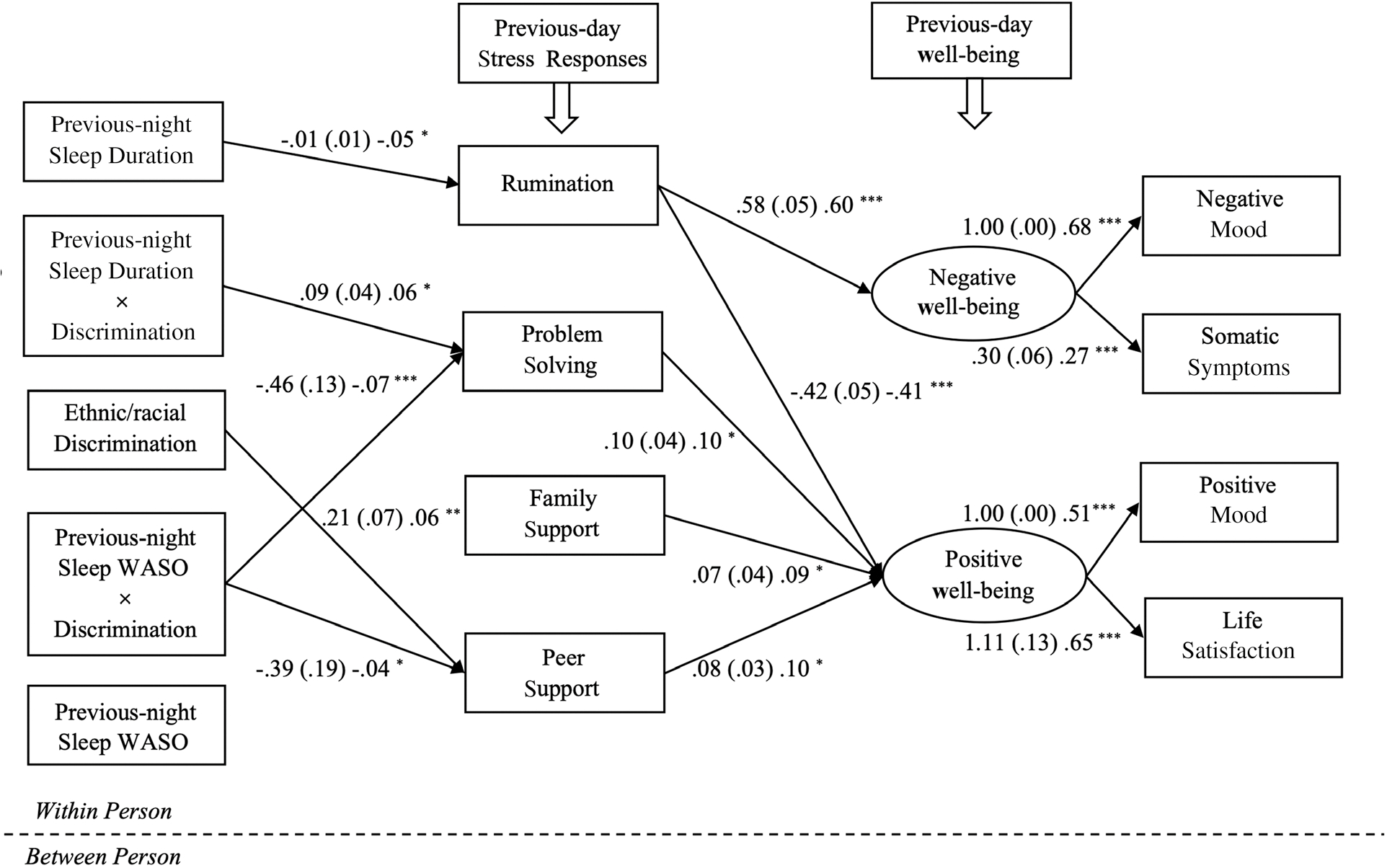

Our second set of analyses linked the moderating effects of previous-night sleep to adolescent well-being (Paths A and B in Figure 1). All significant direct effects among study variables are shown in Figure 3. A full report of direct effects is shown in online supplement Table S2. We then estimated indirect effects of same-day discrimination on adolescent well-being by varying levels of previous-night sleep (Table 3).

Figure 3.

Significant coefficient estimates for moderated mediating pathways among previous-night sleep, same-day ethnic/racial discrimination, stress responses, and adolescent well-being. Covariates included a standard set of daily- and person-level variables, as well as previous-day stress responses and well-being. Model fit was good, χ2(101) = 212.70, p < .001; comparative fit index = .986, root mean square error of approximation = .021, standardized root mean square residual = .023 for within and .035 for between. For each path, we report its unstandardized coefficient estimate, followed by its standard error in parentheses, standard coefficient estimate, and significance level. A full report of coefficient estimates is in online supplement Table S2. WASO = wake minutes after sleep onset.

*p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001.

Table 3.

Indirect Effects of Previous-Night Sleep and Same-Day Ethnic/Racial Discrimination on Adolescent Well-being (Paths A and B in Figure 1)

| Indirect effects |

||

|---|---|---|

| Paths | B | 95% CI |

|

| ||

| Rumination | ||

| Estimated without the moderating effects of sleep | ||

| Sleep duration → rumination → negative well-being | −.008 | [−.059, .042] |

| Sleep duration → rumination → positive well-being | .006 | [−.059, .041] |

| Problem solving | ||

| Sleep duration high | ||

| Discrimination → problem solving → negative well-being | −.002 | [−.017, .014] |

| Discrimination → problem solving → positive well-being | .020 | [.003, .040]* |

| Sleep duration low | ||

| Discrimination → problem solving → negative well-being | .000 | [−.006, .012] |

| Discrimination → problem solving → positive well-being | −.004 | [−.030, .016] |

| Sleep quality high (WASO low) | ||

| Discrimination → problem solving → negative well-being | −.002 | [−.017, .016] |

| Discrimination → problem solving → positive well-being | .022 | [.003, .045]* |

| Sleep quality low (WASO high) | ||

| Discrimination → problem solving → negative well-being | .001 | [−.005, .010] |

| Discrimination → problem solving → positive well-being | −.006 | [−.025, .008] |

| Family support | ||

| Estimated without the moderating effects of sleep | ||

| Discrimination → family support → negative well-being | −.005 | [−.018, .005] |

| Discrimination → family support → positive well-being | .009 | [−.005, .032] |

| Peer support | ||

| Sleep quality high (WASO low) | ||

| Discrimination → peer support → negative well-being | .008 | [−.007, .026] |

| Discrimination → peer support → positive well-being | .025 | [.004, .052]* |

| Sleep quality low (WASO high) | ||

| Discrimination → peer support → negative well-being | .002 | [−.003, .012] |

| Discrimination → peer support → positive well-being | .007 | [−.007, .024] |

Note. Estimates are reported at three decimal places to show significant numbers for standard errors. All stress response variables were tested simultaneously in the same model. Covariates included a standard set of daily- and person-level variables, as well as previous-day stress responses and well-being. High sleep duration was one standard deviation above the person average. Low sleep duration was one standard deviation below the person average. High sleep quality was one standard deviation below the person average of WASO. Low sleep quality was one standard deviation above the person average of WASO. WASO = wake minutes after sleep onset.

p < .05.

Focusing on rumination, no significant interaction effects emerged between previous-night sleep and discrimination. Yet, greater rumination was associated with higher levels of negative well-being and lower levels of positive well-being. As previous-night sleep duration was significantly associated with adolescents’ rumination in the first set of analyses (see Table 2), we estimated indirect effects of sleep duration on adolescent well-being via rumination without considering the sleep–discrimination interactions. However, the indirect effects were not significant (see “Rumination” rows in Table 3).

Focusing on problem solving as the coping variable, we observed significant interaction effects between previous-night sleep (duration, WASO) and discrimination. Moreover, greater problem solving was associated with higher levels of positive well-being (but not negative well-being). We then estimated indirect effects of discrimination on well-being that varied by adolescents’ previous-night sleep duration and quality (see “Problem Solving” rows in Table 3). Two significant indirect effects emerged for positive well-being (but not negative well-being). When adolescents slept longer (i.e., duration was one standard deviation above the person average) or better (i.e., WASO was one standard deviation below the person average) the previous night, greater discrimination was associated with greater problem solving, which in turn was associated with higher levels of positive well-being. These indirect effects were not significant when adolescents slept less or more poorly the previous night.

Focusing on family support as the coping variable, no significant interaction emerged between previous-night’s sleep (duration, WASO) and discrimination. Regarding the paths between family support and well-being, greater family support was linked to greater positive well-being (but not negative well-being). We then estimated indirect effects of discrimination on adolescent well-being via family support without considering the moderating effects of previous-night’s sleep (see “Family Support” rows in Table 3). No significant indirect effects emerged.

Finally, focusing on peer support as the coping variable, we observed a significant interaction effect between previous-night’s sleep WASO and discrimination. Moreover, greater peer support was associated with higher levels of positive well-being (but not negative well-being). We then estimated indirect effects of discrimination on adolescent well-being that varied by on previous-night’s sleep (see “Peer Support” rows in Table 3). When adolescents slept better the previous night (i.e., WASO was one standard deviation below the person average), greater discrimination was associated with seeking more peer support, which in turn, was associated with higher levels of positive well-being. These indirect effects were not significant when adolescents had poorer previous-night’s sleep or for negative well-being.

Variations by Ethnic/Racial Groups

The third set of analyses examined whether the previously examined associations varied by adolescents’ ethnicity/race. Multiple group analyses showed that no significant differences emerged between models that constrained paths to be equal across the three ethnic/racial groups versus models that freely estimated these paths, for the moderating effects of sleep (χ2(40) = 44.13, p = .30) or the moderated mediation pathways (χ 2(56) = 70.71, p = .09).

Sensitivity Analyses

We also conducted three sets of sensitivity analyses with different samples to examine the robustness of the study findings. The first set of analyses used data from all possible participants across all possible days (N = 350 participants across 4,900 days). The second set of analyses used the analytic sample but excluded outlying sleep data (3 SD above or below the mean; N = 250 across 2,541 days). The third set of analyses used the analytic sample but excluded participants who had < 5 days of valid data (N = 225 participants across 2,521 days). Estimates of path coefficients are shown in online supplement Table S3. We observed an identical pattern of significant findings, for the moderating effects of previous-night sleep and the moderated mediation, thus supporting the robustness of the study findings.

Discussion

Sleep is critical for adolescents’ healthy development across multiple domains (Owens et al., 2014; Shochat et al., 2014), and recent scholarship has documented the role of sleep in helping adolescents navigate race-related stress (El-Sheikh et al., 2016; Yip, 2015). Yet, more research is needed to understand when and how sleep helps buffer the negative impact of ethnic/racial discrimination on adolescent well-being, particularly in adolescents’ daily lives. Using a daily diary design and actigraphy sleep data, the current study investigated the extent to which previous-night sleep promoted different types of stress responses (rumination vs. active coping) when adolescents experience ethnic/racial discrimination, and the subsequent implications for adolescent well-being. Consistent with prior research (Goosby et al., 2018; Seaton & Douglass, 2014; Zeiders, 2017), the daily frequency of ethnic/racial discrimination was relatively low. Yet, discrimination was uniquely associated with adolescents’ daily well-being over and beyond the influence of general stress. Results showed that when adolescents slept longer and better (i.e., longer duration, better quality) the previous night, they engaged in more active coping (i.e., problem solving, peer support seeking) on days in which they experienced higher than their typical levels of discrimination. In turn, these coping strategies conferred more positive adolescent well-being. The observed relations were consistent across ethnic/racial groups.

Previous research has observed sleep (duration, quality) to mitigate the influence of discrimination on well-being at the person level (El-Sheikh et al., 2016; Yip, 2015). The current study contributes to this line of research by identifying one possible mechanism through which sleep (both duration and quality) buffers the negative impact of discrimination: by promoting adolescents’ engagement in active coping (problem solving, peer support seeking) that are then linked to better daily well-being. The promotive effect of sleep for coping is consistent with the broader literature highlighting the critical role of sleep for adolescents’ cognitive functioning (de Bruin et al., 2017), social competence, and peer relationships (Shochat et al., 2014). The current study suggests that longer and better (less time awake) sleep equips adolescents with cognitive and emotional resources that facilitate constructive thinking and problem solving the following day (Killgore et al., 2008). These cognitive and emotional resources also enabled adolescents to seek out peer support and talk to their friends when confronted with ethnic/racial discrimination.

Importantly, the current study contributes to the existing person-level literature by adding a focus on temporal and directional associations between daily variables. By focusing on previous-night’s sleep and controlling for adolescents’ previous-day stress responses and well-being, our analyses supported the temporal order in which sleep preceded the same-day associations between experiences of discrimination, stress responses, and adjustment. Although the association between sleep and coping may be reciprocal, alternative temporal patterns (e.g., discrimination and stress responses interacted to predict sleep that night) were not supported in our data. The daily diary approach enabled us to disentangle the predictors and consequences of daily fluctuations in adolescents’ social experiences (Almeida, 2005; Snippe et al., 2016), thus underscoring the importance of promoting both sleep duration and quality in helping adolescents better navigate daily challenges of discrimination.

An interesting contrast emerged when comparing family versus peer support in the current findings. Peer support (but not family support) emerged as an effective coping strategy that promoted well-being when adolescents experienced greater discrimination, particularly if they slept better the previous night. This contrast highlights the importance of peer contexts for ethnic/racial minority adolescent development. The existing literature has examined the role of families in helping adolescents navigate racism and prejudice (e.g., family ethnic/racial socialization), with less attention paid to other developmental contexts such as peer groups (Hughes, Watford, & Del Toro, 2016). Using daily diary data, the current study highlights friends and peers as immediate sources of support on days when adolescents experience greater discrimination. This finding is consistent with the broader literature highlighting the relative importance of friends and peers compared to parents for adolescent adjustment and decision-making (Albert, Chein, & Steinberg, 2013; Brown & Larson, 2009), which may be particularly salient during the transition to high school (Benner, 2011). The current finding also contributes to an emerging body of research on the ethnic/racial aspects of peer relationships (Benner & Wang, 2017; Nelson, Syed, Tran, Hu, & Lee, 2018).

The lack of significant associations between discrimination and family support in the current study, however, should not be interpreted to mean that family support is not important. In fact, we did observe a positive association between family support and adolescents’ positive well-being. Moreover, a large body of research has documented the role of parental ethnic/racial socialization in attenuating the deleterious impact of discrimination on adolescent well-being (Hughes et al., 2016). However, existing research has not employed daily diary approaches, leaving open the question how parental socialization is related to daily discrimination experiences. Because the current study employed a daily diary design, it is possible that parents are less likely to observe and share adolescents’ day-to-day experiences of discrimination; as such, instead of providing immediate, same-day support, parents may have a stronger “preventive” role as supported by research on ethnic/racial socialization. Future work is needed to further disentangle the person- and daily-level influences of family and peer support in the context of discrimination.

Finally, although previous-night sleep did not interact with discrimination to predict rumination, we observed a main effect in which sleeping more the previous night was linked to lower levels of rumination. This finding is consistent with prior research documenting the cross-sectional links between sleep problems and rumination using national data (Palmer, Oosterhoff, Bower, Kaplow, & Alfano, 2018). Yet, interestingly, it also contrasts with the existing literature that has more consistently documented an inverse effect of rumination on sleep, particularly on delayed sleep onset (Mazzer, Boersma, & Linton, 2019). Given that sleep is a multifaceted construct (Sadeh, 2015), different sleep indicators may be differentially associated with rumination. For example, sleep duration on the previous night may influence the extent to which adolescents ruminate, whereas bed-time rumination may lead to prolonged sleep latency. Future research is needed to further understand how other indicators of sleep (e.g., onset latency) relate to adolescents’ experiences of discrimination and well-being on a daily basis.

While the current study contributes to the current literature, it is not without limitations. This study investigated only one possible mechanism through which sleep buffers the negative impact of ethnic/racial discrimination (i.e., via promoting active coping). Other mechanisms are likely to operate as well. For example, as part of an important bioregulatory system, better and longer sleep on days after the occurrence of discrimination may help adolescents better process and regulate their physiological and psychological responses to discrimination (El-Sheikh et al., 2016), thus attenuating the negative impact of discrimination on individual well-being on the following days. Moreover, recent theoretical work has posed sleep as a biological response to race-related stress (Levy, Heissel, Richeson, & Adam, 2016). An increasing body of empirical research has indeed documented the deleterious impact of ethnic/racial discrimination on adolescent sleep (Goosby et al., 2018; Huynh & Gillen-O’Neel, 2013; Zeiders, 2017; Yip et al., in press). Sleep is also tied to daytime interactions with parents and peers (Tavernier, Heissel, Sladek, Grant, & Adam, 2017). How sleep, individuals’ social experiences including discrimination, and well-being relate to each other is a complex process, both at the daily level and cumulatively, over time. The moderated mediating pathway examined in the current study should be viewed as one operating mechanism within this complex system. Much more research is needed to understand the various pathways linking discrimination, sleep, and development.

Moreover, although the current study identified the timing of sleep effects (i.e., prior night), other primary variables were examined within the same day. For the present study, we purposefully focus on same-day associations to capture the concurrent, immediate associations between discrimination, stress responses and adolescents’ feelings. We also carefully controlled prior-day levels of stress responses and adolescent well-being, thus demonstrating how daily experiences of discrimination could potentially link to same-day changes in adolescents’ stress responses and well-being, adjusting for prior day carry over effects. However, future research using experience sampling data or time-lagged analyses would be able to disentangle the timing of these variables and provide a stronger support of the mediating pathways tested in this study.

Regarding the measurement of sleep, unfortunately, the current study had a considerable proportion (25%) of missing data due to actigraph malfunctions beyond our control. Future research should consider alternate actigraphy devices. Moreover, future studies should also include a more comprehensive set of covariates that may influence sleep (e.g., medication use). Regarding the measurement of discrimination, the current study investigated adolescents’ experiences of discrimination tied to ethnicity and race, a critical factor for adolescent development in the United States (Benner et al., 2018). Although the current findings may extend to other forms of discrimination such as those based on gender, sexual orientation, appearance, and religion (Russell, Sinclair, Poteat, & Koenig, 2012), future work is needed to further understand adolescents’ experiences using an intersectionality perspective. The current measure also does not distinguish discrimination by different perpetrators (e.g., peers, teachers, society), which may be differentially related to domains of adolescent well-being (Benner & Graham, 2013) and stress responses. For example, adolescents may be more likely to seek friends’ support when discrimination comes from other peers, but seek more family support when discrimination comes from educators or the larger society. These possibilities are ripe for future research.

Finally, regarding the current sample, this study focused on a relatively narrow developmental period, ninth grade. How children and adolescents respond to discrimination (e.g., seek support from friends vs. families) may look quite different across developmental stages. As such, whether the current findings hold for other age groups is an open question. Moreover, given the relatively small sizes of each ethnic/racial group in the sample (n = 103, 57, 96 for Asian, Black, and Latinx groups, respectively), the null findings regarding ethnic/racial differences should be interpreted with caution. The current findings should also be interpreted within the context of a relatively high proportion of female participants, and the differential missingness by adolescent gender and ethnicity/race.

Despite these caveats and limitations, the current study contributes to an emerging area of research focused on the role of sleep in ethnic/racial minority adolescent development. Building upon recent research that has documented the role of sleep in attenuating the negative impact of ethnic/racial discrimination at the person level (El-Sheikh et al., 2016; Yip, 2015), the current study highlights the daily mechanisms through which sleep promotes adolescents’ coping on days when they experience greater discrimination, using a daily diary design and actigraphy data. These findings are particularly informative for prevention and intervention practices, highlighting sleep as a critical element in helping adolescents navigate race-related challenges in everyday life.

Supplementary Material

Figure S1. (a–c) Regions of Significance for the Same-Day Associations Between Ethnic/Racial Discrimination and Coping by Previous-Night Sleep

Table S1. Sensitivity Analyses for Alternative Relationships Among Same-Day Ethnic/Racial Discrimination, Stress Responses, and Sleep (Same-Day Ethnic/Racial Discrimination and Stress Responses Interacted to Influence Sleep That Night)

Table S2. Coefficient Estimates for Moderated Mediation among Previous-Night Sleep, Same-Day Ethnic/Racial Discrimination, Stress Responses, and Adolescent Well-being (Paths A and B in Figure 1)

Table S3. Sensitivity Analyses of the Moderating Effects of Sleep and Moderated Mediation Models in Various Samples

Acknowledgments

The research supported in this publication was supported by Developmental Sciences Division of the National Science Foundation under award BCS—1354134 and the National Institute of Minority Health and Health Disparities of the National Institutes of Health under award R21MD011388. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Science Foundation or the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Supporting Information

Additional supporting information may be found in the online version of this article at the publisher’s website:

Contributor Information

Yijie Wang, Michigan State University.

Tiffany Yip, Fordham University.

References

- Abela JRZ, Aydin CM, & Auerbach RP (2007). Responses to depression in children: Reconceptualizing the relation among response styles. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 35, 913–927. 10.1007/s10802-007-9143-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Acebo C, Sadeh A, Seifer R, Tzischinsky O, Wolfson AR, Hafer A, & Carskadon MA (1999). Estimating sleep patterns with activity monitoring in children and adolescents: how many nights are necessary for reliable measures? Sleep, 22, 95–103. 10.1093/sleep/22.1.95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aiken LS, & West SG (1991). Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Albert D, Chein J, & Steinberg L (2013). Peer influences on adolescent decision making. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 22, 114–120. 10.1177/0963721412471347 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almeida DM (2005). Resilience and vulnerability to daily stressors assessed via diary methods. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 14, 64–68. 10.1111/j.0963-7214.2005.00336.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez AN, & Juang LP (2010). Filipino Americans and racism: A multiple mediation model of coping. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 57, 167–178. 10.1037/a0019091 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benner AD (2011). The transition to high school: Current knowledge, future directions. Educational Psychology Review, 23, 299–328. 10.1007/s10648-011-9152-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benner AD, & Graham S (2013). The antecedents and consequences of racial/ethnic discrimination during adolescence: Does the source of discrimination matter? Developmental Psychology, 49, 1602–1613. 10.1037/a0030557 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benner AD, & Wang Y (2017). Racial/ethnic discrimination and adolescents’ well-being: The role of cross-ethnic friendships and friends’ experiences of discrimination. Child Development, 88, 493–504. 10.1111/cdev.12606 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benner AD, Wang Y, Shen Y, Boyle AE, Polk R, & Cheng Y-P (2018). Racial/ethnic discrimination and well-being during adolescence: A meta-analytic review. American Psychologist, 73, 855–883. 10.1037/amp0000204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borders A, & Liang CTH (2011). Rumination partially mediates the associations between perceived ethnic discrimination, emotional distress, and aggression. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 17, 125–133. 10.1037/a0023357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown BB, & Larson J (2009). Peer relationships in adolescence. In Lerner RM & Steinberg L (Eds.), Handbook of adolescent psychology, Vol 2: Contextual influences on adolescent development (3rd ed., pp. 74–103). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF 3rd, Monk TH, Berman SR, & Kupfer DJ (1989). The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: A new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Research, 28, 193–213. 10.1016/0165-1781(89)90047-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compas BE, Jaser SS, Bettis AH, Watson KH, Gruhn MA, Dunbar JP, . . . Thigpen JC (2017). Coping, emotion regulation, and psychopathology in childhood and adolescence: A meta-analysis and narrative review. Psychological Bulletin, 143, 939–991. 10.1037/bul0000110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahl RE (1996). The regulation of sleep and arousal: Development and psychopathology. Development and Psychopathology, 8, 3–27. 10.1017/S0954579400006945 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- de Bruin EJ, van Run C, Staaks J, & Meijer AM (2017). Effects of sleep manipulation on cognitive functioning of adolescents: A systematic review. Sleep Medicine Reviews, 32, 45–57. 10.1016/j.smrv.2016.02.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeGarmo DS, Martinez J, & Charles R (2006). A culturally informed model of academic well-being for Latino youth: The importance of discriminatory experiences and social support. Family Relations, 55, 267–278. 10.1111/j.1741-3729.2006.00401.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dewald JF, Meijer AM, Oort FJ, Kerkhof GA, & Bögels SM (2010). The influence of sleep quality, sleep duration and sleepiness on school performance in children and adolescents: A meta-analytic review. Sleep Medicine Reviews, 14, 179–189. 10.1016/j.smrv.2009.10.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doane LD, & Thurston EC (2014). Associations among sleep, daily experiences, and lonliness in adolescence: Evidence of moderating and bidirectional pathways. Journal of Adolescence, 37, 145–154. 10.1016/j.adolescence.2013.11.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Sheikh M, Tu KM, Saini EK, Fuller-Rowell TE, & Buckhalt JA (2016). Percieved discrimination and youths’ adjustment: Sleep as a moderator. Journal of Sleep Research, 25, 70–77. 10.1111/jsr.12333 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia Coll C, Lamberty G, Jenkins R, McAdoo HP, Crnic K, Wasik BH, & García HV (1996). An integrative model for the study of developmental competencies in minority children. Child Development, 67, 1891–1914. 10.2307/1131600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geldhof GJ, Preacher KJ, & Zyphur MJ (2014). Reliability estimation in a multilevel confirmatory factor analysis framework. Psychological Methods, 19, 72–91. 10.1037/a0032138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goosby BJ, Cheadle JE, Strong-Bak W, Roth TC, & Nelson TD (2018). Perceived discrimination and adolescent sleep in a community sample. The Russell Sage Foundation Journal of the Social Sciences, 4, 43–61. 10.7758/rsf.2018.4.4.03 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrell SP (2000). A multidimensional conceptualization of racism-related stress: implications for the well-being of people of color. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 70, 42–57. 10.1037/h0087722 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilt LM, McLaughlin KA, & Nolen-Hoeksema S (2010). Examination of the response styles theory in a community sample of young adolescents. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 38, 545–556. 10.1007/s10802-009-9384-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes D, Watford JA, & Del Toro J (2016). A transactional/ecological perspective on ethnic-racial identity, socialization, and discrimination. Advances in Child Development and Behavior, 51, 1–41. 10.1016/bs.acdb.2016.05.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huynh VW, & Gillen-O’Neel C (2013). Discrimination and sleep: The protective role of school belonging. Youth & Society, 48, 649–672. 10.1177/0044118X13506720 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kann L, McManus T, Harris WA, Shanklin SL, Flint KH, Queen B, . . . Ethier KA (2018). Youth risk behavior surveillance—United States, 2017 (Vol. 67). Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiang L, & Buchanan CM (2014). Daily stress and emotional well-being among Asian American adolescents: Same-day, lagged, and chronic associations. Developmental Psychology, 50, 611–621. 10.1037/a0033645 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Killgore WDS, Kahn-Greene ET, Lipizzi EL, Newman RA, Kamimori GH, & Balkin TJ (2008). Sleep deprivation reduces perceived emotional intelligence and constructive thinking skills. Sleep Medicine, 9, 517–526. 10.1016/j.sleep.2007.07.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kouros CD, & El-Sheikh M (2015). Daily mood and sleep: Reciprocal relations and links with adjustment problems. Journal of Sleep Research, 24, 24–31. 10.1111/jsr.12226 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus RS, & Folkman S (1984). Stress, appraisal, and coping. New York, NY: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Levy DJ, Heissel JA, Richeson JA, & Adam EK (2016). Psychological and biological responses to race-based social stress as pathways to disparities in educational outcomes. American Psychologist, 71, 455–473. 10.1037/a0040322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang CTH, Alvarez AN, Juang LP, & Liang MX (2007). The role of coping in the relationship between perceived racism and racism-related stress for Asian Americans: Gender differences. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 54, 132–141. 10.1037/0022-0167.54.2.132 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lilienfeld SO (2017). Microaggressions: Strong claims, inadequate evidence. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 12, 138–169. 10.1177/1745691616659391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lippman LH, Anderson Moore K, Guzman L, Ryberg R, McIntosh H, Ramos MF, . . . Kuhfeld M (2014). Flourishing children: Defining and testing indicators of positive development. Springer briefs in well-being and quality of life research. New York, NY: Springer Science+Business Media. [Google Scholar]

- Mazzer K, Boersma K, & Linton SJ (2019). A longitudinal view of rumination, poor sleep and psychological distress in adolescents. Journal of Affective Disorders, 245, 686–696. 10.1016/j.jad.2018.11.053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]