Abstract

Speakers of all human languages regularly use intonational pitch to convey linguistic meaning, such as to emphasize a particular word. Listeners extract pitch movements from speech and evaluate the shape of intonation contours independent of each speaker’s pitch range. We used high-density electrocorticography to record neural population activity directly from the brain surface while participants listened to sentences that varied in intonational pitch contour, phonetic content, and speaker. Cortical activity at single electrodes over the human superior temporal gyrus selectively represented intonation contours. These electrodes were intermixed with, yet functionally distinct from, sites that encoded different information about phonetic features or speaker identity. Furthermore, the representation of intonation contours directly reflected the encoding of speaker-normalized relative pitch but not absolute pitch.

Humans precisely control the pitch of their voices to encode linguistic meaning (1, 2). All spoken languages use suprasegmental pitch modulations at the sentence level or speech intonation to convey meaning not explicit in word choice or syntax (3). Raising the pitch on a particular word can change the meaning of a sentence. Whereas “Anna likes oranges” communicates that it is Anna, not Lisa, who likes oranges, “Anna likes oranges” communicates that Anna likes oranges, not apples. Similarly, rising pitch at the end of an utterance can signal a question (“Anna likes oranges?”). Confounding the listener’s task, pitch also varieswith the length of a speaker’s vocal folds (4), such that the highest pitch values reached by some low voices are still lower than the lowest of a higher-pitched voice.

Lesion and neuroimaging studies have implicated bilateral frontal and temporal regions in the perception of speech intonation (5–16). Human neuroimaging and primate electrophysiology have also suggested the existence of a putative general pitch center in the lateral Heschl’s gyrus (HG) and the adjacent superior temporal gyrus (STG) (17–21). However, a more fundamental question than anatomical localization is what the neural activity in those regions encodes—that is, the precise mapping between specific stimulus features and neural responses. How is intonational pitch in speech encoded, and does its representation contain concurrent information about what is being said and by whom? Furthermore, because the same auditory feature of pitch is the primary cue to both intonation and speaker identity (22), how does the auditory cortex represent both kinds of information?

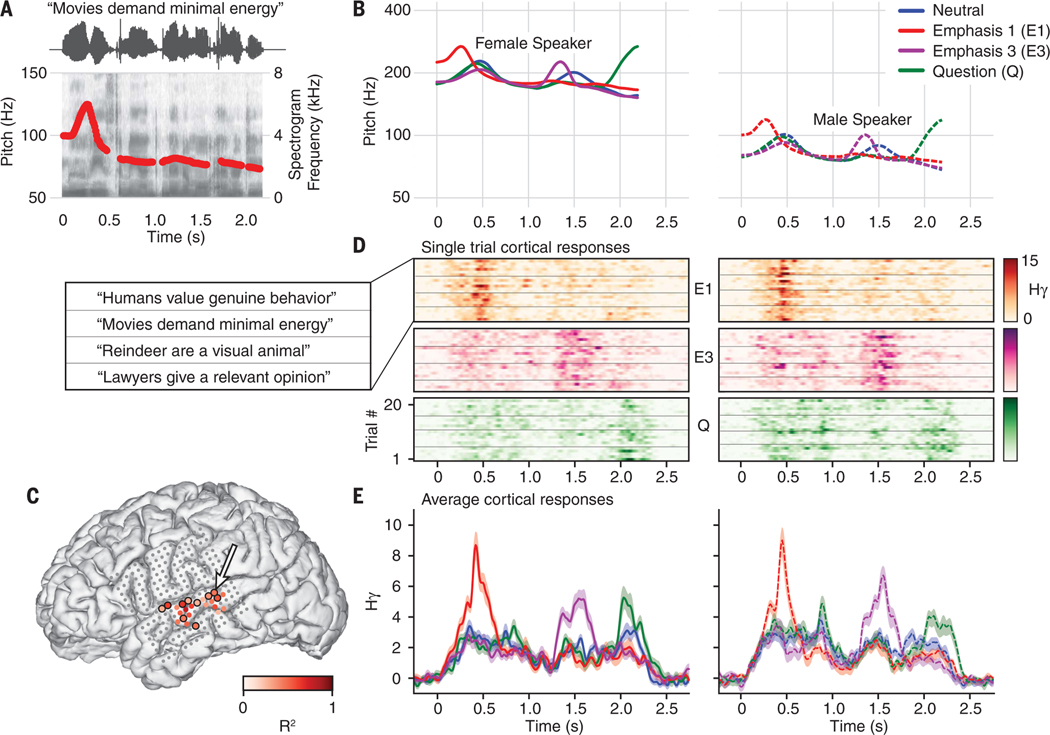

We designed and synthesized a controlled set of spoken sentences that independently varied intonation contour, phonetic content, and speaker identity (Fig. 1A). The four intonation conditions—neutral, emphasis 1, emphasis 3, and question—are linguistically distinct (2) (Fig. 1B). By systematically manipulating the pitch (fundamental frequency: f0) contour of each token, we ensured that only pitch, not intensity or duration of segments, differed between intonation conditions. The three speakers consisted of one synthesized male (f0: 83 ± 10 Hz) and two synthesized female speakers (f0: 187 ± 23 Hz). The two female speakers had the same f0 but differing formant frequencies, one of which matched the male speaker’s formant frequencies.

Fig. 1. Neural activity in the STG differentiates intonational pitch contours.

(A) Stimuli consisted of spoken sentences synthesized to have different intonation contours. This panel depicts an example token with the pitch accent on the first word (emphasis 1), with amplitude signal, spectrogram, and pitch (f0) contour shown. (B) Pitch contours for four intonation conditions, shown for a female speaker (left, solid lines) and a male speaker (right, dashed lines). (C) Electrode locations on a participant’s brain. Color represents the maximum variance in neural activity explained by intonation, sentence, and speaker on electrodes where the full model was significant at more than two time points (omnibus F test; P < 0.05, Bonferroni corrected). Nonsignificant electrodes are shown in gray. Electrodes with a black outline had a significant (F test, P < 0.05, Bonferroni corrected) main effect of intonation. Activity from the indicated electrode (arrow) is shown in (D) and (E). (D) Single-trial responses from the indicated electrode in (C), divided by intonation condition (top, middle, bottom) and speaker (left, right). Horizontal lines within each intonation and speaker pair further divide trials by sentence (legend at left). Hγ, high-γ analytic amplitude z-scored to a silent baseline. (E) Average neural activity within each intonation condition. Average responses (±1 SEM) to a female (left) and male speaker (right) with nonoverlapping absolute-pitch values (B).

Participants (N = 10) passively listened to these stimuli while we recorded cortical activity from subdurally implanted, high-density grids (placed for clinical localization of refractory seizures). We examined the analytic amplitude of the high-gamma band (70 to 150 Hz) of the local field potential, which correlates with local neuronal spiking (23–26).We aligned the high-gamma responses to sentence onset and used time-dependent general linear models to determine whether and how neural responses on each electrode systematically depended on stimulus conditions. The fully specified encoding model included categorical variables for intonation, sentence, and speaker condition, as well as terms for all pairwise interactions and the three-way interaction. Figure 1C shows the maximum variance explained in the neural activity for significant electrodes (defined as electrodes where the full model reached significance at more than two time points; omnibus F test, P < 0.05, Bonferroni corrected) in one subject. We next found the electrodes whose activity differentiated intonation contours (F test, P < 0.05, Bonferroni corrected) (circled electrodes in Fig. 1C). For one electrode on STG, single-trial activity increased after the pitch accents in the emphasis 1 and emphasis 3 conditions and after the pitch rise in the question condition (Fig. 1D). The same pattern of activity by intonation contour was seen for each sentence in the stimulus set (Fig. 1D) and for the two formant-matched speakers whose absolute vocal pitch values did not overlap (Fig. 1E).

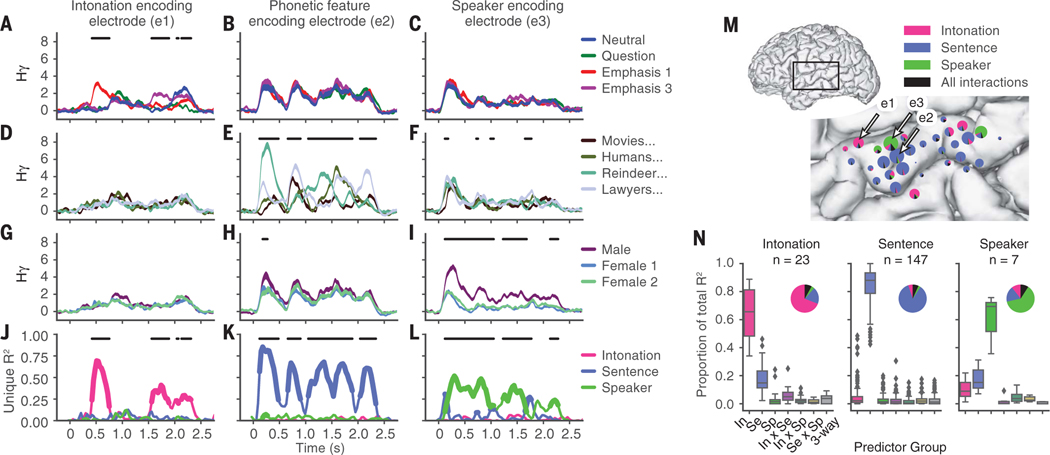

We next calculated the contribution of each main effect of stimulus dimension, as well as their interactions to variance explained in the neural activity at each significant electrode. Some electrodes showed differences between intonation conditions but not sentence or speaker conditions (Fig. 2, A, D, and G) (maximum R2 intonation = 0.69, P = 1 × 10−49; Fig. 2J). These electrodes would respond similarly to the sentences “Movies demand minimal energy” and “Humans value genuine behavior” if presented with the same intonation contour (e.g., emphasis on the first word), despite very different phonetic content. Other electrodes showed differences between sentence conditions but not intonation or speaker conditions (Fig. 2, B, E, and H) (maximum R2 sentence = 0.85, P = 1 × 10−73; Fig. 2K). In these electrodes, the response to a sentence was the same regardless of whether it was said neutrally, with emphasis, or as a question, but the responses strongly differed for a sentence with different phonetic content. Other electrodes differentiated between speaker conditions but not intonation or sentence conditions (Fig. 2, C, F, and I) (maximum R2 speaker = 0.67, P = 1 × 10−47; Fig. 2L). These electrodes mainly distinguished between the male speaker and the two female speakers (15 of 16 electrodes; 1 of 16 differentiated between high and low formants). The anatomical distribution of encoding effects is shown as pie charts on the cortical surface, indicating the proportion of variance explained (Fig. 2M and fig. S1). Some intonation-encoding sites were adjacent to the lateral HG on the STG, but others were found throughout the STG, interspersed with other electrodes that encoded phoneme- and speaker-related information.

Fig. 2. Independent neural encoding of intonation, sentence, and speaker information at single electrodes.

(A to C) Neural response averaged over intonation contour for three example electrodes (mean ± 1 SEM). Neural activity on electrode one (A) differentiates intonation contours, whereas activity on electrodes two (B) and three (C) does not. Black lines indicate time points when means were significantly different between intonation conditions (F test, P < 0.05, Bonferroni corrected). (D to F) Average neural response to each sentence condition for the same electrodes as in (A) to (C). Black lines indicate significant differences between sentence conditions. (G to I) Average neural response to each speaker for the same electrodes as in (A) to (C) and (D) to (F). Black lines indicate significant differences between speaker conditions. (J to L) Unique variance explained by main effects for each example electrode. Bold lines indicate time points of significance for each main effect. Black lines indicate time points when the full model was significant (omnibus F test; P < 0.05, Bonferroni corrected). (M) Map of intonation, sentence, and speaker encoding for one subject. Locations of electrodes one, two, and three are indicated. The area of the pie chart is proportional to the total variance explained. Wedges show the relative variance explained by each stimulus dimension (color) or for pairwise and three-way interactions (black) for each significant electrode. (N) Proportion of variance explained by main effects and interactions across time points when the full model was significant for all significant electrodes across all 10 participants with each electrode classified as either intonation (In), sentence (Se), or speaker (Sp) on the basis of which stimulus dimension was maximally encoded (Tukey box plot). Pie charts show the average proportions of the total variance explained. n, number of electrodes.

We assigned each electrode to one of three categories—intonation, sentence, or speaker— and then examined the proportion of variance explained by each group of predictors (Fig. 2N). The contributions of interactions were minimal (median total proportion of variance explained: 6.4%) (Fig. 2N), indicating orthogonal encoding of each stimulus dimension.

On the basis of previous work (27), we hypothesized that electrodes whose activity differentiated between sentence conditions responded to particular classes of phonetic features. We therefore calculated the average phoneme selectivity index (PSI) (27) for each significant electrode from its responses to a separate, phonetically transcribed speech corpus (TIMIT) (28) (fig. S2, A and B) and correlated it with the maximum unique variance explained by each main effect (fig. S2, C and D). Average PSI and R2sentence values were positively correlated (r = 0.64, P < 1 × 10−20; fig. S2C), whereas average PSI was negatively correlated with both R2 intonation and R2 speaker values (r = −0.18, P < 0.05; r = −0.15, P > 0.05, respectively; fig. S2D). Therefore, sentence electrode activity could be explained by the specific phonetic features in each stimulus token (fig. S2E).

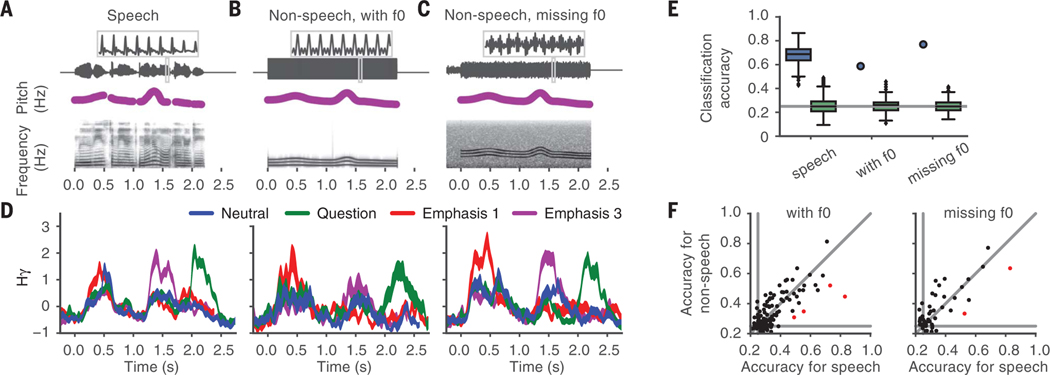

The phonetically invariant representation of intonation suggests that intonation is encoded as an isolated pitch contour, irrespective of any lexical information or phonetic content. We thus created a set of nonspeech stimuli that preserved intonational pitch contours but did not contain spectral information related to phonetic features (29) (Fig. 3, A and B). To test that responses are due to the psychoacoustic attribute of pitch rather than acoustic energy at the fundamental frequency, we also created a set of missing fundamental stimuli (30, 31) (Fig. 3C). Neural responses to intonation contours were similar between speech and nonspeech contexts, including themissing f0 context (Fig. 3D). To quantify this similarity, we used linear discriminant analysis to fit a model to predict intonation condition from neural responses to speech and then tested this model on responses to the two types of nonspeech stimuli (Fig. 3E). Model performance on the nonspeech responses was as good as model performance on speech responses in almost all cases (with f0: 97%, 117 of 121 electrodes; missing f0: 96%, 47 of 49 electrodes) (Fig. 3F).

Fig. 3. Similar neural responses to intonation in speech and nonspeech contexts.

(A) Acoustic signal, pitch contour, and spectrogram of an example speech token. A portion of the acoustic signal is expanded to show the quasiperiodic amplitude variation that is characteristic of speech. (B)Nonspeechtoken containing energy at the fundamental frequency (f0), with pitch contour matching that in (A).Three bands of spectral power can be seen at the fundamental, second harmonic, and third harmonic. (C) Nonspeech token, with same pitch contour as in (A) and (B), that does not contain f0. Pink noise was added from 0.25 s before the onset of the pitch contour to the pitch contour offset. (D)Average neural response by intonation contour to speech (left), nonspeech with f0 (middle), and nonspeech missing f0 (right) stimuli at an example electrode (mean ± 1 SEM). (E) Classification accuracy of a linear discriminant analysis model fit on neural responses to speech stimuli to predict intonation condition for the electrode represented in (D) (blue; shuffled: green).The accuracy of the speech-trained model on the nonspeech data, both with and without f0, was within the middle 95% of accuracies for speech stimuli. (F) Mean accuracy for speech stimuli versus accuracy for nonspeech stimuli (left: with f0; right: missing f0). Each marker represents a significant electrode from participants who listened to each type of nonspeech stimuli (with f0: N = 8 participants; missing f0: N = 3 participants). Red markers indicate electrodes whose model performance on nonspeech stimuli was below the middle 95% of accuracy values from speech stimuli. Gray lines indicate chance performance at 25% and the unity line.

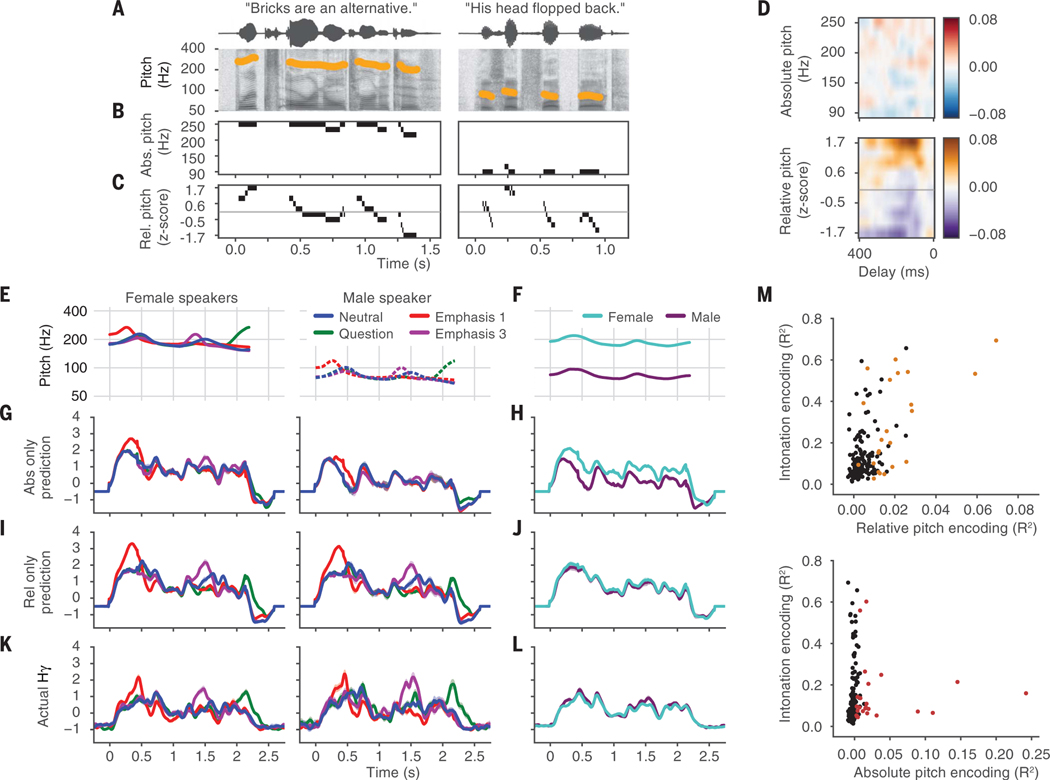

The pitch contour of an utterance can be described in either absolute or relative terms (Fig. 4, A to C). Although absolute pitch is the primary acoustic feature for speaker identification (22), behavioral evidence that listeners perceptually normalize pitch by speaker (32, 33) suggests the existence of a relative-pitch representation in the brain. For electrodes discriminating intonation contours, responses to a low-pitched male voice and a high-pitched female voice were statistically identical (Fig. 1E), so it is unlikely that the amount of neural activity was directly related to the absolute-pitch value.

Fig. 4. Cortical representation of intonation relies on relative-pitch encoding, not absolute-pitch encoding.

(A) Example tokens from the TIMIT speech corpus. (B) Absolute-pitch (ln Hz) feature representation. Bins represent different values of absolute pitch. (C) Relative-pitch (z score of ln Hz within speaker) feature representation. The gray line indicates a relative-pitch value of 0. (D) Pitch temporal receptive field from one example electrode that encoded relative but not absolute pitch (R2relative = 0.03, significant by permutation test; R2 absolute = 0.00, not significant). The receptive field shows which stimulus features drive an increase in the neural response—in this case, high values of relative pitch. Color indicates regression weight (arbitrary units) (E) Pitch contours of the original stimulus set. (F) Average pitch contours for male and female speakers in the original stimulus set across intonation conditions. (G) Prediction of the model fit with only absolute-pitch features. (H) Average predicted response across all male and female tokens from the absolute-pitch–only model. (I) Prediction of the model fit with only relative-pitch features. (J) Average predicted response across all male and female tokens from the relative-pitch–only model. (K) Actual neural responses to original stimulus set (mean ± 1 SEM). The actual response of this electrode was better predicted by the relative-pitch–only model (rrel_pred = 0.85; rabs_pred = 0.66). (L) Actual neural responses averaged over intonation conditions. (M) Scatterplot between relative- and absolute-pitch encoding with neural discriminability of intonation contours, showing that intonation contour discriminability is correlated with relative-pitch encoding but not absolute-pitch encoding (rrelative_intonation = 0.57, P < 1 × 10−16; rabsolute_intonation = 0.03, P > 0.05). Colored markers show electrodes with significant (permutation test; R2 > 95th percentile of null distribution) relative- and absolute-pitch encoding for the top and bottom panels, respectively.

To test the hypothesis that neural activity differentiating intonation contours can be explained by relative pitch but not absolute pitch, we presented participants with tokens from the TIMIT speech corpus containing sentences spoken by hundreds of male and female speakers (Fig. 4A and fig. S3, A to C) (28). We then compared encoding models (34) containing absolute pitch (Fig. 4B), relative pitch (Fig. 4C), or both to compute the unique variance (R2) explained by absolute- and relative-pitch features at each electrode. We also used these models to predict neural responses to the original set of synthesized intonation stimuli to compare the prediction performance between absolute- and relative-pitch models.

Figure 4D shows the absolute- and relative-pitch receptive fields for one example electrode that had a significant increase in R2 when relative-but not absolute-pitch features were included in the model (permutation test, see materials and methods). This electrodewas tuned to high relative pitch but did not respond differentially to different absolute-pitch levels. Other relative-pitch–encoding electrodes were tuned for low relative pitch (fig. S4, A to C) or for both high and low relative pitch at different delays (fig. S4, D and E), indicating an increased response to pitch movement. Across absolute-pitch–encoding electrodes, some were tuned to high absolute pitch, whereas others were tuned to low absolute pitch (fig. S5).

We next determined which pitch features (absolute or relative) better predicted the neural responses to the original stimulus set (Fig. 4, E and F). For the electrode whose receptive field is shown in Fig. 4D, the absolute-pitch–only model predicted that the pattern of responses to different intonation contours differed for the female and male speakers (Fig. 4G), with a greater response to the female speakers compared with the male speaker (Fig. 4H). Conversely, the relative-pitch–only model predicted similar responses for the female and male speakers (Fig. 4, I and J). The actual neural response to these stimuli is shown in Fig. 4K (Fig. 4L shows an additional view of the actual responses averaged over intonation conditions) and was more similar to the prediction from the relative-pitch–only model than the prediction from the absolute-pitch–only model (rrel_pred = 0.85; rabs_pred = 0.66). Responses of 84% of intonation electrodes (38 of 45 electrodes) were better predicted by relative pitch. In addition, relative-pitch encoding predicted neural discriminability of intonation contours (r = 0.57, P < 1 × 10−16), whereas absolute-pitch encoding did not (r = 0.03, P = 0.67) (Fig. 4M).

We demonstrated direct evidence for the concurrent extraction of multiple socially and linguistically relevant dimensions of speech information at the level of human nonprimary, high-order auditory cortex in the STG. Our results are consistent with the idea that the main types of voice information, including speech and speaker identity, are processed in dissociable pathways (35, 36).

The importance of relative pitch to linguistic prosody is well established because vocal pitch ranges differ across individual speakers (2, 37). Additionally, in music, melodies can be recognized even when the notes are transposed. The representation of relative auditory features may, in fact, be a general property of the auditory system because contours can be recognized in multiple auditory dimensions, such as loudness and timbre (38, 39). Functional magnetic resonance imaging blood oxygen level–dependent activity increases in nonprimary areas of the human lateral HG, planum polare, and anterolateral planum temporale for harmonic tone complexes that change in pitch height and pitch chroma (40), where activity depends on the variability of pitch-height changes (41, 42). However, in addition to relative-pitch encoding, we also found coexisting absolute-pitch encoding in the STG, consistent with reports that differences in cortical activation for different speakers are correlated with differences in fundamental frequency (43).

In animal-model studies, spectral and temporal features important for pitch are encoded at many levels of the auditory system, from the auditory nerve (44, 45) to the primary auditory cortex (46). Single neurons can encode information about pitch by systematically varying their firing rate to sounds with different pitch (47, 48), and some respond similarly to pure tone and missing fundamental tones with matched pitch (21). Multiunit activity containing information about whether a target sound was higher or lower in pitch than a previous sound may play a role in relative-pitch processing (49). However, a direct neural encoding of relative pitch or its dissociation from sites encoding absolute pitch has not been previously demonstrated.

Perceptual studies have demonstrated that speaker normalization for pitch occurs in the sentence context (32, 50) and can also occur as rapidly as within the first six glottal periods (~20 to 50 ms) (51). We have demonstrated how intonational pitch undergoes specialized extraction from the speech signal, separate from other important elements, such as the phonemes themselves. An outstanding future question is how such components are then integrated to support a unified, meaningful percept for language comprehension.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank S. Shattuck-Hufnagel, K. Johnson, C. Schreiner, M. Leonard, Y. Oganian, N. Fox, and B. Dichter for helpful comments on the manuscript. This work was supported by grants from the NIH (R01-DC012379 to E.F.C. and F32 DC014192–01 to L.S.H.). E.F.C. is a New York Stem Cell Foundation Robertson Investigator. This research was also supported by the New York Stem Cell Foundation, the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, the McKnight Foundation, The Shurl and Kay Curci Foundation, and The William K. Bowes Foundation. Raw data, analysis code, and supporting documentation for this project are accessible online at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.826950.

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.Cutler A, Dahan D, van Donselaar W, Lang. Speech 40, 141–201 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ladd DR, Intonational Phonology (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2008). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shattuck-Hufnagel S, Turk AE, J. Psycholinguist. Res. 25, 193–247 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Titze IR, J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 85, 1699–1707 (1989). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ross ED, Arch. Neurol. 38, 561–569 (1981). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Heilman KM, Bowers D, Speedie L, Coslett HB, Neurology 34, 917–921 (1984). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pell MD, Baum SR, Brain Lang. 57, 80–99 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Witteman J, van Ijzendoorn MH, van de Velde D, van Heuven VJJP, Schiller NO, Neuropsychologia 49, 3722–3738 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Plante E, Creusere M, Sabin C, Neuroimage 17, 401–410 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Meyer M, Alter K, Friederici AD, Lohmann G,von Cramon DY, Hum. Brain Mapp. 17, 73–88 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Meyer M, Steinhauer K, Alter K, Friederici AD,von Cramon DY, Brain Lang. 89, 277–289 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gandour J. et al. , Neuroimage 23, 344–357 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Doherty CP, West WC, Dilley LC, Shattuck-Hufnagel S, Caplan D, Hum. Brain Mapp. 23, 85–98 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Friederici AD, Alter K, Brain Lang. 89, 267–276 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tong Y. et al. , Neuroimage 28, 417–428 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kreitewolf J, Friederici AD, von Kriegstein K, Neuroimage 102, 332–344 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Griffiths TD, Büchel C, Frackowiak RS, Patterson RD, Nat. Neurosci. 1, 422–427 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Patterson RD, Uppenkamp S, Johnsrude IS, Griffiths TD, Neuron 36, 767–776 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Penagos H, Melcher JR, Oxenham AJ, J. Neurosci. 24, 6810–6815 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schönwiesner M, Zatorre RJ, Exp. Brain Res. 187, 97–105 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bendor D, Wang X, Nature 436, 1161–1165 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.van Dommelen WA, Lang. Speech 33, 259–272 (1990). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Steinschneider M, Fishman YI, Arezzo JC, Cereb. Cortex 18, 610–625 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ray S, Maunsell JHR, PLOS Biol. 9, e1000610 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Edwards E. et al. , J. Neurophysiol. 102, 377–386 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Crone NE, Boatman D, Gordon B, Hao L, Clin. Neurophysiol. 112, 565–582 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mesgarani N, Cheung C, Johnson K, Chang EF, Science 343, 1006–1010 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Garofalo JS, Lamel LF, Fisher WM, Fiscus JG,Pallett DS, Dahlgren NL, Zue V, “TIMIT acoustic-phonetic continuous speech corpus,” Linguistic Data Consortium (1993); https://catalog.ldc.upenn.edu/ldc93s1. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sonntag GP, Portele T, Comput. Speech Lang. 12, 437–451 (1998). [Google Scholar]

- 30.Licklider JCR, J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 26, 945 (1954). [Google Scholar]

- 31.Plack CJ, Oxenham AJ, Fay RR, Pitch: Neural Coding and Perception (Springer, 2006), vol. 24. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wong PCM, Diehl RL, Speech Lang J Hear. Res 46, 413–421 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gussenhoven C, Repp BH, Rietveld A, Rump HH, Terken J,J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 102, 3009–3022 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Theunissen FE et al. , Netw. Comput. Neural Syst 12, 289–316 (2001). [Google Scholar]

- 35.Belin P, Fecteau S, Bédard C, Trends Cogn. Sci. 8, 129–135 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Belin P, Bestelmeyer PEG, Latinus M, Watson R,Br. J. Psychol. 102, 711–725 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jakobson R, Fant G, Halle M, Preliminaries to Speech Analysis: The Distinctive Features and Their Correlates (MIT Press, 1951). [Google Scholar]

- 38.McDermott JH, Lehr AJ, Oxenham AJ, Psychol. Sci. 19, 1263–1271 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kluender KR, Coady JA, Kiefte M, Speech Commun. 41, 59–69 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Warren JD, Uppenkamp S, Patterson RD,Griffiths TD, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100, 10038–10042 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Allen EJ, Burton PC, Olman CA, Oxenham AJ,J. Neurosci. 37, 1284–1293 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zatorre RJ, Delhommeau K, Zarate JM, Front. Psychol. 3, 544 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Formisano E, De Martino F, Bonte M, Goebel R, Science 322, 970–973 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cariani PA, Delgutte B, J. Neurophysiol. 76, 1698–1716 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cariani PA, Delgutte B, J. Neurophysiol. 76, 1717–1734 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fishman YI, Micheyl C, Steinschneider M, J. Neurosci. 33, 10312–10323 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bizley JK, Walker KMM, Silverman BW,King AJ, Schnupp JWH, J. Neurosci. 29, 2064–2075 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bizley JK, Walker KMM, King AJ, Schnupp JWH,J. Neurosci. 30, 5078–5091 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bizley JK, Walker KMM, Nodal FR, King AJ,Schnupp JWH, Curr. Biol. 23, 620–625 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pierrehumbert J, J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 66, 363–369 (1979). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lee C-Y, J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 125, 1125–1137 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.