ABSTRACT

Mucosal associated invariant T (MAIT) cells are innate T cells that recognize bacterial metabolites and secrete cytokines and cytolytic enzymes to destroy infected target cells. This makes MAIT cells promising targets for immunotherapy to combat bacterial infections. Here, we analyzed the effects of an immunotherapeutic agent, the IL-15 superagonist N-803, on MAIT cell activation, trafficking, and cytolytic function in macaques. We found that N-803 could activate MAIT cells in vitro and increase their ability to produce IFN-γ in response to bacterial stimulation. To expand upon this, we examined the phenotypes and functions of MAIT cells present in samples collected from PBMC, airways (bronchoalveolar lavage [BAL] fluid), and lymph nodes (LN) from rhesus macaques that were treated in vivo with N-803. N-803 treatment led to a transient 6 to 7-fold decrease in the total number of MAIT cells in the peripheral blood, relative to pre N-803 time points. Concurrent with the decrease in cells in the peripheral blood, we observed a rapid decline in the frequency of CXCR3+CCR6+ MAITs. This corresponded with an increase in the frequency of CCR6+ MAITs in the BAL fluid, and higher frequencies of ki-67+ and granzyme B+ MAITs in the blood, LN, and BAL fluid. Finally, N-803 improved the ability of MAIT cells collected from PBMC and airways to produce IFN-γ in response to bacterial stimulation. Overall, N-803 shows the potential to transiently alter the phenotypes and functions of MAIT cells, which could be combined with other strategies to combat bacterial infections.

KEYWORDS: IL-15 superagonist, MAIT cells, N-803, SIV, immunology, macaque

INTRODUCTION

Mucosal associated invariant T cells (MAIT cells) are a specialized type of innate T cells whose T cell receptors (TCR) can detect bacterial metabolites presented by the MHC-class I related (MR1) molecules on antigen-presenting cells (1–3). Unlike conventional T cells, cross-linking of the TCR on MAIT cells immediately activates them to perform effector functions, such as the secretion of cytokines and cytolytic enzymes (reviewed in [4]).

Several studies have shown that MAIT cells can recognize bacterial metabolites that are synthesized as part of the bacterial riboflavin biosynthetic pathway (5, 6). Many bacteria that are associated with causing disease in humans produce these metabolites, including E. coli (7), M. tuberculosis (Mtb) (8), F. tularensis (9), S. typhimurium (10), K. pneumoniae (11), and C. albicans (12). MAIT cells have been championed as potentially attractive targets for immunotherapeutic interventions by which to combat many of these bacterial infections (13).

MAIT cells can also be activated in a TCR-independent manner (6, 14). Cytokines such as IL-7, IL-12, IL-18, and IL-15 can also activate MAIT cells (15–17), leading to increases in cytokine and cytolytic granule production (15–17).

The IL-15 superagonist N-803 has recently garnered attention as an immunotherapeutic agent for combating several cancers and, possibly, HIV (18–22). N-803 contains a constitutively active (N72D) IL-15 molecule and a human IgG Fc receptor that leads to improved function and a longer half-life in vivo (23–26). This agent expands CD8 T cells and NK cells (24, 27), increases their cytolytic functions, and improves their trafficking to sites of inflammation and infection (19, 28). N-803 has been safe in phase I trials in humans, and it is already in use in clinical trials in cancer patients (29, 30) as well as in phase II clinical trials in HIV+ patients in Thailand and in the United States (31) (https://immunitybio.com/immunitybio-announces-launch-of-phase-2-trial-of-il-15-superagonist-anktiva-with-antiretroviral-therapy-to-inhibit-hiv-reservoirs/; https://actgnetwork.org/studies/a5386-n-803-with-or-without-bnabs-for-hiv-1-control-in-participants-living-with-hiv-1-on-suppressive-art/).

IL-15 can activate MAIT cells in vitro (15); however, no studies have been performed to evaluate the effect of IL-15 or N-803 on MAIT cells in vivo. Furthermore, the impact of IL-15 treatment on the function of MAIT cells on bacteria other than E. coli is not known. We hypothesized that N-803 could activate MAIT cells in vitro as well as improve MAIT cell activation, function, and trafficking to mucosal sites in vivo.

Macaques provide an ideal model system in which to characterize the effects of N-803 on MAIT cell trafficking and cytolytic function, as macaque and human MAIT cells are phenotypically and functionally similar (32, 33). To test our hypothesis, we first examined the in vitro effect of N-803 on MAIT cells isolated from healthy and simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV)-positive macaques. Then, we examined MAIT cells from a previous study of SIV+, ART-naive rhesus macaques who were treated with N-803 (22). We examined the effects of N-803 on MAIT cell phenotype and function in the PBMC, lymph nodes, airways, and lung tissue, both in vitro and in vivo.

RESULTS

N-803 can activate MAIT cells from macaque PBMC.

We first wanted to determine if N-803 could activate MAIT cells in vitro at similar or greater levels than those observed using rhIL-15. RhIL-15 activates MAIT cells directly through the IL-15 receptor and indirectly through the production of IL-18 by monocytes which activate MAIT cells via the IL-18 receptor (15). Therefore, to assess both the direct and indirect impacts of N-803 on MAIT cell activation, we used the total PBMC from healthy cynomolgus macaques or isolated the TCRVα7.2+ cells (the MAIT cells in these macaques are primarily TCRVα7.2+ [34]). Then, the total PBMC or TCRVα7.2+ cells were treated for 24 h with increasing concentrations of recombinant rhIL-15 or N-803 (Fig. 1A). Across four separate isolations, we obtained 70.1% to 90.9% purity (average 78.1%) of the TCRVα7.2+ isolated cells. We then measured the frequency of MAIT cells expressing the activation markers CD69, CD25, and HLA-DR (Fig. 1B shows an example gating schematic).

FIG 1.

IL-15 superagonist N-803 activates MAIT cells in vitro. (A) Schematic of in vitro experiments performed. Frozen PBMC from healthy macaques were incubated overnight with the indicated concentrations of either recombinant IL-15 (rhIL-15) or N-803. Alternatively, the TCRVα7.2+ cells (MAIT cells, purple dots) were isolated from the PBMC and then incubated overnight with the indicated concentrations of either rhIL-15 or N-803. Flow cytometry was performed after incubation to assess activation. All experiments were performed a minimum of 3 times, and a representative experiment is shown. (B) Representative gating schematic used for the flow cytometry for the experiments described in (A) to detect MAIT cells present in PBMC (top panels) or TCRVα7.2-isolated cells (bottom panels) as well as the frequencies of CD69+, CD25+, and HLA-DR+ cells. (C) Graphical analysis of the experiments described in (A) for MAIT cells present in PBMC. The frequencies of MAIT cells expressing CD69 are shown for the indicated concentrations of rhIL-15 (blue circles) or N-803 (red squares). (D) Graphical analysis of the experiments described in (A) for TCRVα7.2-isolated MAIT cells. Graphs show the frequencies of MAIT cells expressing either CD69 (left) or CD25 (right) for the indicated concentrations of rhIL-15 (blue circles) or N-803 (red squares).

We found that the addition of N-803 to the PBMC led to a dose-dependent increase in the frequency of CD69+ MAIT cells (Fig. 1C, red line). This was similar to the performance observed with recombinant IL-15 (Fig. 1C, blue line). We did not observe any increases in the frequency of MAIT cells expressing CD25 or HLA-DR (data not shown). When using the isolated TCRVα7.2+ cells, we found dose-dependent increases in the frequency of CD69+ (Fig. 1D, left panel) and CD25+ (Fig. 1D, right panel) cells. These data suggest that, like rhIL-15, N-803 can activate MAIT cells in vitro.

N-803 improves the IFN- γ production of bacterial-stimulated MAIT cells derived from the PBMC of both SIV+ and SIV-naive cynomolgus macaques, which can be blocked by the addition of antibodies to MR1.

We wanted to determine if N-803 enhanced the production of IFN-γ, TNF-α, and CD107a by MAIT cells stimulated in vitro with E. coli or M. smegmatis. We included PBMC collected from five cynomolgus macaques before infection with various strains of SIV as well as PBMC collected from the same macaques at necropsy after SIV infection (Table 1). The PBMC were incubated overnight in media alone, N-803, or recombinant IL-7 as a control. Recombinant IL-7 has been shown to increase the frequency of cytolytic MAIT cells when coincubated with an antigen (17). The following day, 10 colony forming units (CFU) of either E. coli or M. smegmatis were then added for every one cell and incubated together for another 6 h. We measured the frequencies of IFN-γ, TNF-α, and CD107a+ MAIT cells by flow cytometry. An example of the gating schematic and the typical cytokine and cytolytic enzyme production during the bacterial stimulation can be found in Fig. S1.

TABLE 1.

Animals and samples utilized in this study

| Animal | SIV strain(s) of challenge | Reference to study in which previously described | Figure(s) in which samples were utilized |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cy0899 | SIVmac239 | 34 | Fig. 1 |

| Cy0900 | SIVmac239 | 34 | Fig. 1 and 2 |

| Cy0918 | SIVmac239 | 34 | Fig. 1 and 2 |

| Cy0919 | SIVmac239 | 34 | Fig. 1 and 2 |

| Cy0756 | SIVmac239Δnef-8×; SIVmac239 | 68 | Fig. 2 |

| Cy0757 | SIVmac239Δnef-8×; SIVmac239 | 68 | Fig. 2 |

| r15053 | SIVmac239M | 39 | Fig. 3, 8, and 10 |

| r15090 | SIVmac239M | 39 | Fig. 3, 8, and 10 |

| r03019 | SIVmac239M | 39 | Fig. 3, 8, and 10 |

| rh2498 | SIVmac239M | 39 | Fig. 3, 8, and 10 |

| rh2493 | SIVmac239M | 39 | Fig. 3, 8, and 10 |

| rh2903 | SIVmac239M | 39 | Fig. 4 and 10 |

| rh2906 | SIVmac239M | 39 | Fig. 4 and 10 |

| rh2907 | SIVmac239M | 39 | Fig. 4 and 10 |

| rh2909 | SIVmac239M | 39 | Fig. 4 and 10 |

| rh2911 | SIVmac239M | 39 | Fig. 4 and 10 |

| rh2920 | SIVmac239M | 39 | Fig. 4 and 10 |

| rh2921 | SIVmac239M | 39 | Fig. 4 and 10 |

| r05053 | SIVmac239M | 39 | Fig. 4 and 10 |

| r10063 | SIVmac239M | 39 | Fig. 4 and 10 |

For PBMC collected from both SIV-naive time points and time points after SIV infection, stimulation with both E. coli and M. smegmatis led to robust increases in IFN-γ, TNF-α, and CD107a+ MAIT cells, even in samples not treated with N-803 or IL-7 (Fig. 2A and B, blue). The observation that MAIT cells retained the majority of their functional capacity after SIV infection was not surprising, as we observed similar results in ex vivo functional assays prior to Mtb coinfection in a previous study (34).

FIG 2.

N-803 increases IFN-γ production from MAIT cells stimulated with either E. coli or M. smegmatis from both SIV-naive and SIVmac239+ macaques. (A) Frozen PBMC from healthy cynomolgus macaques (n = 5) were incubated overnight with 10 ng/mL N-803, 50 ng/mL IL-7, or media control. The following day, functional assays were performed using 10 CFU bacteria/cell of either E. coli or M. smegmatis as stimuli, as described in Materials and Methods. Cells were incubated for 6 h in the presence of bacteria, and then flow cytometry was performed to determine the frequencies of MAIT cells expressing IFN-γ (top), TNF-α (center), or CD107a (bottom). analysis of variance (ANOVA) tests with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons were performed to determine the statistical significance between each treatment group (no stim, N-803, or IL-7) for each stimulus (E. coli or M. smegmatis). P = ns, not significant; *, P ≤ 0.05; **, P ≤ 0.005. (B) Frozen PBMC from the same cynomolgus macaques (n = 5) as in (A) were taken from necropsy time points which occurred 6 months to 1 year after the SIVmac239 infection. PBMC were incubated with 10 ng/mL N-803, 50 ng/mL IL-7, or media control as in (A). Functional assays were performed as described in (A) to determine the frequencies of MAIT cells expressing IFN-γ (top), TNF-α (center), or CD107a (bottom). ANOVA tests with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons were performed to determine the statistical significance between each treatment group (no stim, N-803, or IL-7) for each stimulus (E. coli or M. smegmatis). P = ns, not significant; *, P ≤ 0.05; **, P ≤ 0.005.

In samples collected from SIV-naive time points, we found that incubation with N-803 enhanced the frequency of MAIT cells producing IFN-γ, TNF-α, and CD107a after stimulation with E. coli. Only the frequencies of MAIT cells producing IFN-γ+ and TNF-α+ were improved by N-803 treatment after stimulation with M. smegmatis (Fig. 2A). For samples collected from SIV+ time points, the N-803 treatment enhanced IFN-γ production from MAIT cells for both E. coli and M. smegmatis stimuli, but it did not significantly enhance TNF-α or CD107a production in a consistent manner (Fig. 2B).

We also assessed whether N-803 affected MAIT cell function against other mycobacterial stimuli. MAIT cells from four SIV-naive macaques were stimulated with BCG (Mycobacterium bovis) or whole-cell lysates from M. tuberculosis H37Rv. We observed no consistent increases in the production of IFN-γ, TNF-α, or CD107a with these stimuli in the absence of N-803, in contrast to stimulation with E. coli and M. smegmatis (Fig. S2). This was consistent with other studies of human MAIT cells (35). Treatment with N-803 enhanced IFN-γ, TNF-α, and CD107a+ production with all stimuli, although this was not always statistically significant. This is similar to the results seen by others in in vitro assays using recombinant IL-15 (36). Furthermore, MAIT cell cytokine production, even in the presence of N-803, could be blocked for all bacterial stimuli (E. coli, M. smegmatis, BCG, and Mtb lysates) when antibodies to MR1 were added to the media prior to the addition of the N-803 and bacterial stimuli (Fig. S2). Together, these data suggest that N-803 treatment improves the cytokine production of MAIT cells incubated with microbial stimuli and that MAIT cell activation could be blocked by the addition of antibodies to MR1.

N-803 improves IFN-γ production of bacterial-stimulated MAIT cells derived from the PBMC and lung tissue, but not the lymph nodes, of SIV+ rhesus macaques.

MAIT cells located in the lung tissue and lung-associated lymph nodes may not behave the same as those derived from the PBMC (37, 38). We isolated lymphocytes from blood (PBMC), lung tissue, and tracheobronchial lymph nodes collected at necropsy from 4 SIV-infected rhesus macaques (Fig. 3) (39). Assays with lung lymphocytes were performed using fresh samples, whereas cryopreserved PBMC and lymph node cells were used.

FIG 3.

In vitro treatment of MAIT cells present in PBMC and lung tissue but not in lymph nodes, with N-803 increases IFN-γ production with E. coli and M. smegmatis bacterial stimuli. SIVmac239+ rhesus macaques (n = 4) were necropsied after more than 8 months of infection, and lymphocytes were isolated from blood, tracheobronchial lymph nodes, and lung tissue. Frozen lymphocytes from PBMC (A), lymph nodes (B), and fresh lymphocytes from lung (C) were incubated overnight with 10 ng/mL N-803, 50 ng/mL IL-7, or media control. The following day, functional assays were performed using 10 CFU bacteria/cell of either E. coli or M. smegmatis as stimuli, as described in the methods. Flow cytometry was performed to determine the frequencies of MAIT cells expressing IFN-γ (top), TNF-α (center), or CD107a (bottom). ANOVA tests with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons were performed to determine the statistical significance between each treatment group (no stim, N-803, or IL-7) for each stimulus (E. coli or M. smegmatis). P = ns, not significant; *, P ≤ 0.05.

Similar to the results displayed in Fig. 2B, the incubation of PBMC, lymph node, and lung tissue from SIV+ rhesus macaques with E. coli and M. smegmatis led to robust increases in the frequencies of IFN-γ+, TNF-α+, and CD107a+ MAIT cells, even in the absence of N-803 or IL-7 (Fig. 3A–C, blue). In particular, high frequencies of MAIT cells from lymph nodes and lungs were TNF-α+ and CD107a+ following bacterial stimulation.

Incubation of PBMC from SIV+ rhesus macaques with N-803 led to statistically significant increases in the frequency of MAIT cells producing IFN-γ with both E. coli and M. smegmatis stimuli compared to media control (Fig. 3A). In the tissues, N-803 enhanced the frequency of IFN-γ-producing bacterial-stimulated MAIT cells from the lung but not from the thoracic lymph nodes (Fig. 3B and C). In contrast, the frequency of MAIT cells producing TNF-α or CD107a after microbial stimulation was high without N-803 or IL-7 treatment, such that these agents did not significantly improve cytokine production.

Administration of N-803 to SIV+ rhesus macaques transiently decreases the number of peripheral MAIT cells.

Other studies previously established that N-803 has superior half-life, tissue retention, and bioactivity compared to recombinant IL-15 in vivo (27). Therefore, we wanted to determine how the administration of N-803 to macaques affected the frequency, distribution, and function of MAIT cells in vivo. We administered N-803 subcutaneously to ART-naive, SIV+ rhesus macaques that were being utilized for a different, unrelated study (Fig. 4) (39). We assessed the phenotypes and frequencies of MAIT cells from the blood, bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid, and lymph nodes collected before and during the first 10 days after receiving the N-803 treatment (Fig. 4A). In previous studies, conventional CD8 T cells were most affected during this period after N-803 treatment (22). Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the pre N-803 time points were collected between 14 and 42 days prior to the N-803 treatment.

FIG 4.

(A) Study outline for N-803 treatment and sample collection. SIV+ rhesus macaques were given 0.1 mg/kg N-803 subcutaneously. For the present study, samples that were collected prior to and during the first 10 days after the first dose of N-803 were used for analysis. (B) Representative gating schematic for the CD3+MR1 tetramer+ cells that were CD8+. Graph on right shows the frequencies of CD3+ MR1 tetramer+ cells that were CD8+ for all 15 rhesus macaques shown in (A). The data were from PBMC collected prior to the N-803 treatment.

We previously established that the MAIT cells in macaques are predominantly CD8+CD4− (34). This was also the case for all 15 rhesus macaques present in the current study; of the CD3+ MR1 tetramer+ cells, the vast majority were CD8+CD4− (Fig. 4B). Therefore, we defined MAIT cells as CD8+ MR1 tetramer+ cells in gating schematics for the macaques in this study (Fig. 5A).

FIG 5.

In vivo treatment of SIV+ macaques with N-803 alters MAIT cell frequencies in peripheral blood. (A) PBMC collected from the indicated time points pre- and post-N-803 treatment were stained with the panel described in Table 3. Flow cytometry was performed as described in the Materials and Methods. Shown is a representative gating schematic for the CD3+CD8+MR1 tetramer+ (MAIT) cells. (B) Flow cytometry was performed as described in (A) at the indicated time points post-N-803 treatment to determine the frequency of the MAIT cells. (C) Complete white blood cell counts (CBC) were used to quantify the absolute number of MAIT cells per μL of blood. (D) The frequencies of MAIT cells from (B) were normalized to the pre N-803 averages for each animal, and the data are presented as fold changes in the frequencies of MAIT cells. (E) The absolute counts of MAIT cells from (C) were normalized relative to the absolute cell counts of the pre N-803 averages for each animal, and the data are presented as fold changes in cell counts. For all statistical analysis in panels A to E, repeated measures ANOVA nonparametric tests were performed with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons for individuals across multiple time points. For individuals for whom samples from time points were missing, mixed-effects ANOVA tests were performed using the Geisser-Greenhouse correction. *, P ≤ 0.05; **, P ≤ 0.005; ***, P ≤ 0.0005; ****, P ≤ 0.0001.

We found that the frequencies of MAIT cells significantly decreased 1 day after N-803 treatment but otherwise remained relatively stable relative to the average frequencies prior to N-803 treatment (Fig. 5B). The absolute number of MAIT cells in the blood was significantly lower on days one and three after the N-803 treatment, relative to the pre-N-803 treatment time points (Fig. 5C).

The absolute number and frequency of MAIT cells in the peripheral blood of macaques varies widely, so it was difficult to clearly determine whether the N-803 treatment affected their trafficking. Therefore, we normalized the data relative to the average values of the pre-N-803 time points on a per-animal basis to calculate the fold change in frequency and the absolute cell number (Fig. 5D and E). After normalization, we observed similar decreases on days one and three post-N-803 treatment (Fig. 5D and E). MAIT cells expanded in the blood on days 7 and 10 post-N-803 treatment, but this was not statistically significant (Fig. 5D and E). For the first 10 days after the N-803 treatment, the fluctuations in MAIT cells in the peripheral blood were transient and consistent with the patterns observed for conventional CD8 T cells in previous studies (19, 22, 40).

As a part of our related study describing the impact of N-803 on the conventional T cells of these same animals, we found that the CD8+ T cell and NK cell absolute counts in the peripheral blood transiently decreased 1 day after the N-803 treatment, followed by a 2 to 10-fold increase by day 7 after treatment with N-803 (39).

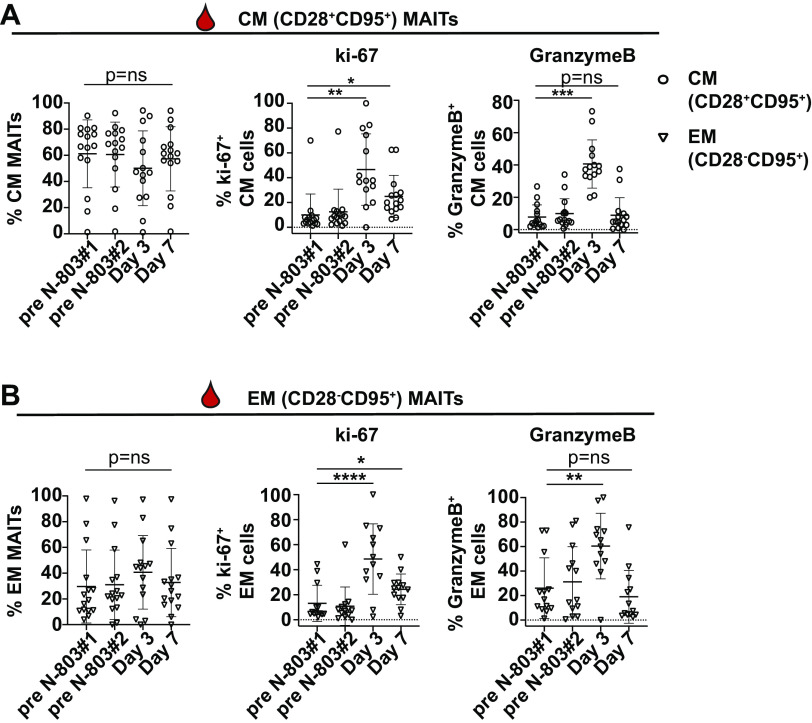

N-803 treatment increases the frequency of granzyme B and ki-67+ MAIT memory cells in the peripheral blood.

Similar to the effects of N-803 on CD8 T cells and NK cells (19, 22, 27, 28), we expected that the treatment of macaques with N-803 could potentially improve MAIT cell function. To begin to assess this, we measured the frequencies of MAIT cells expressing the degranulation marker granzyme B and the proliferation marker ki-67. We separately examined the frequencies of MAIT cells expressing markers consistent with central memory (CM; CD28+CD95+) and effector memory (EM; CD28−CD95+) because recombinant IL-15 can differentially affect these two memory populations (41–46).

Similar to our previous study with cynomolgus macaques (34), peripheral MAIT cells from these rhesus macaques had both central and effector memory phenotypes (Fig. 6A and B). The frequencies of CM and EM MAITs did not change during the N-803 treatment (Fig. 6A and B, left panel). Next, we assessed the frequencies of CM and EM MAIT cells that were ki-67+ and granzyme B+ over the course of the N-803 treatment. We found transient increases in the frequencies of ki-67+ (Fig. 6A and B, center panel) and granzyme B+ (Fig. 6A and B, right panel) CM and EM MAIT cells on day 3 post-N-803 treatment, relative to pre-N-803 treatment time points. Overall, we concluded that the N-803 treatment led to an increase in the frequency of MAIT cells capable of proliferating and degranulating.

FIG 6.

In vivo treatment of SIV+ macaques with N-803 increases the frequency of ki-67+ and granzyme B+ MAIT cells in the peripheral blood. (A and B) Frozen PBMC collected from the indicated time points before and after the N-803 treatment were thawed, and flow cytometry was performed with the panel described in Table 2. The frequency of MAIT cells (CD8+MR1 tetramer+ cells) that were (A) central memory (CM; CD28+CD95+, open circles, left panel) or (B) effector memory (EM; CD28−CD95+, open triangles, left panel) are shown. The frequencies of CM and EM cells expressing ki-67 (A and B, center panels) and granzyme B (A and B, right panels) cells were determined. Repeated measures ANOVA nonparametric tests were performed with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons for individuals across multiple time points. For individuals for whom samples from time points were missing, mixed-effects ANOVA tests were performed using the Geisser-Greenhouse correction. *, P ≤ 0.05; **, P ≤ 0.005.

In vivo N-803 treatment leads to a decline in the frequency of peripheral CXCR3+CCR6+ MAIT cells.

We hypothesized that the decline in MAIT cells in the peripheral blood (Fig. 5) could be a consequence of MAIT cells trafficking to lymph nodes. We measured the frequency of CXCR5+ MAIT cells, as CXCR5 expression is associated with homing to lymph node follicles, which is similar to the traffic pattern of the bulk CD3+CD8+ T cells that was observed in previous N-803 studies (19, 22, 27, 47, 48). We also measured the frequency of MAIT cells expressing CXCR3 and CCR6, which have been associated with homing to tissues such as the lung, gut, or other sites of immune activation (49–51). A representative gating schematic for the expression of these markers on MAIT cells prior to and 3 days after the N-803 treatment is shown (Fig. 7A).

FIG 7.

In vivo treatment of SIV+ macaques with N-803 decreases the frequency of CXCR3+CCR6+ MAIT cells in the peripheral blood. (A) Frozen PBMC collected from the time points before and after the N-803 treatment indicated on the axes in (B) were thawed and stained with the panel described in Table 3. Flow cytometry was performed to determine the frequencies of the CD8+MR1 tetramer+ (MAIT cells) expressing chemokine markers CXCR5, CXCR3, and CCR6. Shown is a representative gating schematic for CXCR5, CXCR3, and CCR6 expression on MAIT cells from a pre-N-803 treatment time point as well as MAIT cells from 3 days post-N-803 treatment. (B) Cells from the indicated time points were stained as described in (A), and the frequencies of MAIT cells that were CXCR3+CCR6+, CCR6+, and CXCR3+ were determined for each time point. Then, the frequencies of each subpopulation were normalized relative to the average of the pre N-803 time points and graphed as the fold changes in the frequencies of CXCR3+CCR6+ (left), CCR6+ (center) and CXCR3+ (right) MAIT cells. Repeated measures ANOVA nonparametric tests were performed with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons for individuals across multiple time points. For individuals for whom samples from time points were missing, mixed-effects ANOVA tests were performed using the Geisser-Greenhouse correction. P = ns, not significant; *, P ≤ 0.05; ***, P ≤ 0.0005.

We did not observe any significant differences in the frequencies of the CXCR5+ MAIT cells after the N-803 treatment compared to the pretreatment time points (data not shown). We examined the frequencies of the CXCR3+, CXCR3+CCR6+, and CCR6+ MAIT cells during the N-803 treatment. We normalized the data for each animal relative to the pre N-803 average because there was wide interanimal variability (Fig. 7B). On days 1 and 3 post-N-803 treatment, there was a statistically significant decline in the fold change of the CXCR3+CCR6+ MAITs (Fig. 7B, left). The decline in CCR6+ MAIT cells on the same days was not statistically significant (Fig. 7B, center). There was a corresponding increase in the fold change of the CXCR3+ cells on day 3 post-N-803 treatment (Fig. 7B, right). Overall, we concluded that N-803 transiently disturbed the population of MAIT cells expressing CXCR3 and CCR6 in the peripheral blood immediately after the N-803 treatment.

N-803 does not alter MAIT cell frequencies in the lymph nodes but does increase their ki-67 and granzyme B expression.

N-803 treatment caused a decline in MAIT cells in the peripheral blood (Fig. 5) as well as changes in the frequencies of MAIT cells expressing chemokine receptors associated with trafficking to sites of immune activation (Fig. 6). Therefore, we wanted to determine whether the MAIT cells were trafficking from the peripheral blood to the lymph nodes or tissue sites after the N-803 treatment. Lymph node samples were collected on days 1 and 7 post-N-803 treatment (Fig. 4). MAIT cells were present at lower frequencies in the lymph nodes compared to MAIT cells in the blood or BAL fluid (Fig. S3), and this result is in concordance with what has been observed in previous studies in SIV-naive macaques (32). We found that the N-803 treatment did not affect the MAIT frequencies (Fig. 8A, left). The MAIT cells in the lymph nodes had a predominant CM phenotype, and the N-803 treatment did not alter the frequencies of the CM (Fig. 8A, center) or EM MAIT cells (Fig. 8A, right).

FIG 8.

N-803 treatment in vivo increases the frequencies of ki-67 and granzyme B+ MAIT cells present in the lymph nodes 1 day after treatment. (A) Frozen cells isolated from lymph node samples that were collected at the indicated time points before and after the N-803 treatment were thawed, and flow cytometry was performed with the panel described in Table 2. The frequency of MAIT cells (CD8+MR1 tet+ cells, left panel), as well as the frequencies of MAIT cells that were central memory (CM; CD28+CD95+, open circles, center panel) or effector memory (EM; CD28−CD95+, open triangles, right panel) were determined for each time point. (B) Central memory (CM) MAIT cells in the lymph nodes from the indicated time points were stained as in (A), and the frequencies of ki-67+ (left panel) and granzyme B+ (right panel) cells were determined. Repeated measures ANOVA nonparametric tests were performed with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons for individuals across multiple time points. For individuals for whom samples from time points were missing, mixed-effects ANOVA tests were performed using the Geisser-Greenhouse correction. P = ns, not significant; *, P ≤ 0.05.

We also examined the frequency of CM MAIT cells in the lymph node and expressing the proliferation marker ki-67 and the degranulation marker granzyme B on days 1 and 7 after the N-803 treatment. There were too few EM MAIT cells for accurate characterization (data not shown). We observed significant increases in the frequencies of ki-67+ and granzyme B+ CM MAIT cells in the lymph nodes 1 day after the N-803 treatment (Fig. 8B). Similar to the peripheral blood, this effect was transient and returned to pretreatment levels by 7 days post treatment.

N-803 affects the phenotype of MAIT cells in the airways.

We also assessed the frequencies and phenotypes of the MAIT cells in the airways during N-803 treatment. We collected BAL fluid prior to and 3 days after the N-803 treatment (Fig. 4). We found that the N-803 treatment did not affect the frequencies of the MAIT cells (Fig. 9B). N-803 also did not alter the frequencies of the total CD3+ cells or the conventional CD3+CD8+ T cells (CD3+CD8+MR1 tetramer-cells) in the BAL fluid for the time points we examined (Fig. S4).

FIG 9.

N-803 treatment in vivo increases the frequency of ki-67+ and CCR6+ MAIT cells present in the airways. (A) Cells isolated from freshly obtained bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid from the indicated time points before and after the N-803 treatment were stained with the antibodies indicated in Table 4 for the flow cytometric analysis. Shown is a representative flow plot of MAIT cells from one individual as well as the ki-67 and CCR6 expression on those cells, from pre- and day 3 post-N-803 time points. (B) The frequencies of MAIT cells (CD8+ MR1 tet+ cells) was determined for the indicated time points before and after the N-803 treatment, as described in (A). (C) The frequency of MAITs expressing ki-67 (left panel) and CCR6 (right panel) were determined as described in (A). Wilcoxon matched pairs rank-signed tests were performed. P = ns, not significant; *, P ≤ 0.05.

We characterized the frequency of MAIT cells expressing the activation markers CD69, HLA-DR, and CD154, the proliferation marker ki-67, and the trafficking marker CCR6 in the BAL fluid. An example of a typical staining for MAIT cells, as well as those for ki-67 and CCR6, is shown for BAL cells collected both before and after the N-803 treatment in Fig. 9A. There were no changes in the frequencies of the CD69, HLA-DR, or CD154+ cells before or after the N-803 treatment (data not shown).

There were significant increases in the frequencies of the ki-67+ and CCR6+ MAIT cells on day 3 post-N-803 treatment, relative to the average of the pre-N-803 treatment time points (Fig. 9C). The increased frequency of CCR6+ MAIT cells in the BAL fluid was coincident with the decrease in CXCR3+CCR6+ and CCR6+ cells in the peripheral blood on day 3 post-N-803 treatment (Fig. 6B).

MAIT cells from the blood and airways of N-803 treated macaques have increased IFN- γ production when stimulated with E. coli and M. smegmatis.

In previous studies, N-803 has been shown to increase the ability of NK and CD8 T cells to produce cytokines and cytolytic enzymes, both in vitro and ex vivo (28, 52). Given that we observed an increase in IFN-γ production from MAIT cells preincubated with N-803 during antigen stimulation in our in vitro functional assays (Fig. 2 and 3), we hypothesized that MAIT cells taken directly from N-803 treated macaques could also have improved function ex vivo. We performed functional assays with total cells collected from PBMC and BAL fluid both before and after the N-803 treatment. Too few MAIT cells were present in the LN to perform similar assays (data not shown).

Unlike the in vitro functional assays, in which cells were preincubated with N-803, the cells from animals prior to and 3 days after the N-803 treatment were defrosted for ex vivo experiments, rested for 4 h, and then incubated with 10 CFU of either E. coli or M. smegmatis. The frequencies of IFN-γ, TNF-α, and CD107a+ MAITs were then determined (Fig. 10). We found that the frequency of MAIT cells from the PBMC and BAL producing IFN-γ after stimulation with E. coli or M. smegmatis was higher when using cells collected from animals 3 days after receiving N-803, relative to the pre-N-803 treatment time points (Fig. 10A and B, top panels). While the frequencies of MAIT cells producing TNF-α and CD107a trended higher on day 3 post-N-803 treatment, relative to the pre N-803 treatment time points, results were inconsistent across tissue type and bacterial stimulus (Fig. 10A and B, center and lower panels). Overall, we concluded that an in vivo N-803 treatment could improve MAIT cell ex vivo function in assays with bacteria, including mycobacteria.

FIG 10.

N-803 treatment in vivo increases the frequency of IFN-γ production from MAIT cells stimulated ex vivo with E. coli or M. smegmatis. (A and B) Cells from either PBMC (A) or bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (B) from pre- and day 3 post-N-803 time points were stimulated either overnight (PBMC, A) or for 6 h (BAL, B) with 10 CFU/cell of either E. coli or M. smegmatis. The frequencies of MAIT cells expressing IFN-γ (top), TNF-α (center), or CD107a (bottom) were determined for each time point. The data for each stimulus (E. coli, left panel; M. smegmatis, right panel) are shown as the frequency of IFN-γ+, TNF-α+, or CD107a+ after background subtraction. Wilcoxon matched pairs rank-signed tests were performed. P = ns, not significant; *, P ≤ 0.05.

DISCUSSION

Here, we show for the first time that an IL-15 superagonist, N-803, can affect MAIT cell phenotypes and functions in vivo in SIV-infected macaques. We found that N-803 could increase the frequencies of ki-67 and granzyme B+ MAIT cells in several compartments, including the lymph nodes and airways (Fig. 6, 8, and 9). Finally, MAIT cells present in the PBMC and the airways from N-803 treated macaques had improved function ex vivo against both E. coli and M. smegmatis stimuli (Fig. 10). Overall, our results establish that N-803 can modestly improve MAIT cell activity and function in vivo.

Like recombinant IL-15, N-803 was able to increase the ability of MAIT cells to produce IFN-γ in response to bacterial stimulus in vitro (Fig. 2) and ex vivo (Fig. 10). These data strengthen the findings from other in vitro studies that suggest that MAIT cells can become activated and exhibit improved antimicrobial functions, both directly and indirectly, by IL-15 (15, 53). Importantly, we found this to be true for both E. coli and M. smegmatis (Fig. 2, 3, and 10), suggesting that N-803 could improve MAIT cell function both in vitro and in vivo across a broad spectrum of bacteria. MAIT cells have been implicated in the antimicrobial response to F. tularensis (9), S. typhimurium (10), K. pneumoniae (11), and C. albicans (12), for example. Therefore, it is possible that N-803 could be utilized in the future to expand and activate MAIT cells in vivo to improve their functions against these bacteria.

More specifically, our findings could have implications for the use of N-803 in mycobacterial-directed immunotherapies. While we did not observe increases in the frequencies of MAIT cells in the lymph nodes (Fig. 8) or lungs (Fig. 9), we did find that N-803 could alter the phenotypes of the MAIT cells present at these locations. Interestingly, the N-803 treatment resulted in an increase in the frequency of CCR6+ MAIT cells in the airways (Fig. 9B). Increased numbers of CXCR3+CCR6+ cells in the airways have been shown to correlate with a protection from and the control of Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb) infection in animal models (54, 55). CXCR3+CCR6+ cells are associated with Mtb-specific Th1/Th17 cytokine production (56, 57), and they have been shown to be the predominant phenotype of cells present in the tissues in subclinical and latent tuberculosis infections (55, 58). N-803 also improved both the in vitro (Fig. 2 and 3) and ex vivo (Fig. 10) ability of the MAIT cells to produce IFN-γ in response to mycobacterial stimuli. Our findings that N-803 alters the CXCR3/CCR6 phenotypes and the IFN-γ production on MAIT cells are similar to the findings of others for CD8 T cells and NK cells (59). In a previous study, mice treated with a heterodimeric IL-15 superagonist exhibited decreased tumor growth, and this correlated with an increase in the frequency of IFN-γ-producing CXCR3+ CD8 T cells and NK cells (59). Overall, the potential for N-803 to increase the frequency of CXCR3+CCR6+ MAIT cells and other immune cells in the airways and in tissue sites of immune activation is intriguing, and future studies could explore this further.

Of great interest for future studies will be to test the effects of N-803 treatment on MAIT cells in Mtb-infected macaques. The transient nature of the in vivo effects of N-803 on MAIT cells (Fig. 5 and 10) likely rules out the possibility that it could be used by itself in Mtb-directed immunotherapy. However, future studies could investigate whether N-803 boosted MAIT cells could have a positive impact on the outcome of an Mtb challenge, most likely as an adjuvant in combination with other MAIT-directed vaccines. For example, Sakai and colleagues have shown that 5-OPRU expanded MAIT cells were able to reduce the bacterial burden if expanded during a chronic Mtb infection (60). Therefore, one possibility would be to use N-803 as an adjuvant during 5-OPRU mediated MAIT cell expansion to see if this could further reduce the bacterial burden. Another possibility would be to use N-803 in combination with BCG vaccination, which is already used to prevent TB disease globally. BCG vaccination can activate MAIT cells in vivo (32); therefore, BCG+N-803 treatment could further improve MAIT function against mycobacteria.

One caveat of our study here is that the samples utilized for the in vivo and ex vivo analyses were collected from animals who were infected with SIV as a part of a separate study (39). Because of this, the macaques were SIV+ and ART-naive at the time of the N-803 treatment, and most of the animals had high viral loads (>104 gag copies/mL plasma viral loads in 12 out of 15 animals) (39). While we did observe improved MAIT cell function during N-803 treatment in these SIV+ macaques (Fig. 6, 8 and 10), it remains a possibility that the SIV infections could have adversely impaired MAIT cell trafficking or function during N-803 treatment, relative to what might have been observed in SIV-naive macaques. We found that in our in vitro studies, MAIT cells from both SIV-naive and SIV+ animals exhibited an N-803 mediated enhancement of IFN-γ production. However, only the MAIT cells from healthy animals exhibited improved TNF-α production when treated with N-803 (Fig. 2). Whether this reflects differences between healthy and SIV+ animals or is a consequence of the small group sizes is unknown. It would not be surprising if the MAIT cells present in healthy versus SIV+ macaques respond differently to N-803. We previously observed a functional impairment of MAIT cells after Mtb and SIV coinfection (34). In a recent study of longitudinal HIV+ samples, the MAIT cells exhibited a more innate-like phenotype over time (61). Similar longitudinal SIV studies in pigtailed macaques found that MAIT cells lost their expression of T-bet, which can affect IFN-γ production (33, 62). SIV+ macaques represent an important cohort of individuals with regard to exploring the roles of immunotherapeutic agents by which to combat Mtb infection, as the immune cells of HIV/SIV+ individuals often have impaired functions, resulting in worse TB disease outcomes than those of healthy individuals (63, 64). Therefore, future studies could focus on treating SIV-naive animals with N-803 to determine whether their MAIT cells behave similarly with regard to trafficking and function.

Our study here focused on the role of N-803 treatment on MAIT cell function, but IL-15 agonists have effects on many other immune cell types in vivo. Recombinant IL-15 has previously been used in vivo in mouse models of Mtb infection, where it was shown that IL-15 treatment protected against an Mtb challenge (65). N-803 has already been shown to expand virus-specific cells in both in vitro and in vivo models of HIV/SIV infection (19); therefore, it is probable that N-803 could improve the conventional T cell response to an Mtb infection as well. IL-15 has also been shown in vitro to expand dendritic cells and improve their ability to suppress the growth of Mtb in infected macrophages (66). Overall, the use of N-803 as an adjuvant to Mtb-directed immunotherapies could improve the function of several cell types and could lead to improved TB disease outcomes.

Overall, our findings here advance the knowledge of how the in vivo treatment of macaques with N-803 affects MAIT cell function. N-803 improved MAIT cell function against mycobacterial stimuli, and also trafficked cells away from the peripheral blood during in vivo treatment. We also present preliminary data that MAIT cells have altered phenotypes and improved functions in the airways. There is a growing body of evidence that IL-15 agonists could improve the outcomes associated with Mtb infection. Our findings could have important implications for the use of N-803 in anti-Mtb immunotherapy.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals and reagents.

(i) Animals. The samples collected from SIV+, ART-naive rhesus macaques treated in vivo with N-803 are described in detail in (39). All of the animals involved in this study were cared for and housed at the Wisconsin National Primate Resource Center (WNPRC), following practices that were approved by the University of Wisconsin Graduate School Institutional Animals Care and Use Committee (IACUC; protocol number G005507). All procedures, such as bronchoalveolar lavages, biopsies, blood draw collections, and N-803 administrations were performed as written in the IACUC protocol and under anesthesia to minimize suffering.

(ii) Frozen samples. Frozen PBMC from other SIV-naive and SIV+ cynomolgus macaques were collected as parts of previous studies (34, 67, 68) and utilized for the in vitro assays described here.

Table 1 shows the animals from which samples were utilized for this study, the SIV strain(s) with which they were challenged, and the figures for which the samples from that animal were used.

(iii) N-803 reagent and administration. N-803 was provided by ImmunityBio (Culver City, CA) and produced using previously described methods (23, 26, 27). Briefly, all macaques treated with N-803 received three doses of 0.1 mg/kg that were delivered subcutaneously and were separated by 14 days. For the present study, the effects of N-803 on MAIT cell immunology are only described for the first dose and the 14 days following. This N-803 dose and route of administration were previously found to be safe and efficacious in macaques (22, 27).

Sample collection for use in ex vivo MAIT cell characterization following N-803 administration.

(i) PBMC and lymph node (LN). Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) from macaques from the in vivo study were isolated from whole blood by Ficoll density gradient centrifugation as previously described (22, 34, 68). For all of the assays described in the manuscript, PBMC were frozen in CryoStor CS5 Freeze Media (BioLife Solutions, Inc.; Bothell, WA) and stained for the phenotypic and functional characterization of the MAIT cells. Lymph node biopsy specimens were processed by cutting them into small pieces and manually passing them through a 70 μm filter. Then, the cells were separated from the tissue via Ficoll density gradient centrifugation, as above. The cells were frozen and stained for the phenotypic characterization of the MAIT cells in bulk assays (described below).

(ii) Bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL). BAL fluid was collected by the primate center staff as previously described (69). Briefly, 30 mL of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) solution was flushed into the airways of macaques and aspirated fully. The BAL fluid was then passed through a 70 μm filter. Cells were resuspended in RPMI media supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) for use in ex vivo assays (described below).

(iii) Lung. Lung tissues were collected at the time of necropsy by primate center staff. Tissue samples were homogenized and then digested for 2 h at 37°C in a solution consisting of RPMI supplemented with 10% FBS and 0.1 mg/mL collagenase II (Sigma-Aldrich; St. Louis, MO). After digestion, homogenates were passed through a 70 μm filter and resuspended in fresh media containing 35% isotonic percoll. Cells were then layered over 60% isotonic percoll and were isolated by percoll gradient centrifugation (1,860 RCF for 30 min). Lymphocytes were collected from the interphase between the 35% and 60% layers, resuspended in RPMI media supplemented with 10% FBS, and used in the in vitro assays described below.

Flow cytometric analysis.

(i) MR1-5-OP-RU tetramer reagents. The rhesus macaque MR1-5OPRU monomer was provided by the NIH tetramer core facility. The MR1 tetramer technology was developed jointly by James McCluskey, Jamie Rossjohn, and David Fairlie, and the material was produced by the NIH Tetramer Core Facility and permitted to be distributed by the University of Melbourne. The MR1-5-OP-RU monomer was then tetramerized with streptavidin-BV421 (0.1 mg/mL; BD biosciences) or streptavidin-APC (0.74 mg/mL; Agilent technologies) at an 8:1 molar ratio of monomer:streptavidin. Briefly, 1/10 volumes of streptavidin-BV421 or streptavidin-APC were added to the monomer every 10 min and incubated in the dark at 4°C until the 8:1 molar ratio was achieved.

(ii) Staining methods. For all flow cytometry panels (antibodies described in Tables 2–7), the order of staining was as follows: surface staining with the MR1-5-OP-RU tetramer was performed prior to other surface and intracellular staining. The MR1 tetramer stains were performed at room temperature in the dark for 45 min in RPMI media supplemented with 10% FBS and 50 nM dasatinib (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA). After 45 min, the cells were washed in a solution of FACS buffer (2% FBS in a 1× PBS solution) containing 50 nM dasatinib, and the surface stains were performed using the antibodies indicated in Tables 2–7 for 20 min at room temperature in the dark. The cells were fixed in a 2% paraformaldehyde solution. Following a 20 min incubation, the samples were either run on a BD Symphony A3 or permeabilized and stained for 20 min at room temperature in medium B (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) for intracellular markers. The flow cytometric analysis was performed on a BD Symphony A3 (Becton, Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ), and the data were analyzed using the FlowJo software package for Macintosh (version 10.7.1).

TABLE 2.

Cytolytic granule/proliferation flow cytometry panel used for PBMCa

| Antibody | Clone | Tetramer/surface/intracellular |

|---|---|---|

| Gag181-189CM9-PE | — | Tetramerb |

| Tat28-35SL8-BV605 | — | Tetramerb |

| MR1 5-OP-RU-BV421 | — | Tetramer |

| CD3-AF700 | SP34-2 | Surface |

| CD4-BUV737 | SK3 | Surface |

| CD8-BUV395 | RPA-T8 | Surface |

| CD28-BV510 | CD28.2 | Surface |

| CD95-PE Cy7 | DX2 | Surface |

| CCR7-BV711 | G043H7 | Surface |

| LIVE/DEAD Near IR ARD | — | — |

| ki-67-AF488 | B56 | Intracellular |

| GranzymeB-PE CF594 | GB11 | Intracellular |

| Perforin-AF647 | PF344 | Intracellular |

—, not applicable.

The Gag181-189CM9-PE and Tat28-35SL8-BV605 tetramers were used to characterize SIV-specific conventional T cells, which are described elsewhere (39).

TABLE 3.

Chemokine/trafficking flow cytometry panel used for PBMCa

| Antibody | Clone | Tetramer/surface |

|---|---|---|

| Gag181-189CM9-PE | — | Tetramerb |

| Tat28-35SL8-BV605 | — | Tetramerb |

| MR1 5-OP-RU-APC | — | Tetramer |

| CD3-AF700 | SP34-2 | Surface |

| CD4-BUV737 | SK3 | Surface |

| CD8-BUV395 | RPA-T8 | Surface |

| CXCR3-BV650 | G025H7 | Surface |

| CCR6-PE Cy7 | 11A9 | Surface |

| CXCR5-PerCP Efluor710 | MU5UBEE | Surface |

| CD122-BV421 | Mik-β3 | Surface |

| CD132-BB515 | AG184 | Surface |

| LIVE/DEAD Near IR ARD | — | — |

—, not applicable.

The Gag181-189CM9-PE and Tat28-35SL8-BV605 tetramers were used to characterize SIV-specific conventional T cells, which are described elsewhere (39).

TABLE 4.

MAIT BAL phenotype flow cytometry panela

| Antibody | Clone | Tetramer/surface/intracellular |

|---|---|---|

| MR1 5-OP-RU-BV421 | — | Tetramer |

| TCRVα7.2-BV605 | 3C10 | Surface |

| CD3-AF700 | SP34-2 | Surface |

| CD4-BV510 | L200 | Surface |

| CD8-BV786 | RPA-T8 | Surface |

| ki-67-AF647 | B56 | Intracellular |

| CD154-PE | 24-31 | Surface |

| CD69-PE Texas Red | TP1.55.3 | Surface |

| CCR6-PE Cy7 | 11A9 | Surface |

| CCR7-FITC | 150503 | Surface |

| HLA-DR-BV650 | G46-6 | Surface |

| LIVE/DEAD Near IR ARD | — | — |

—, not applicable.

TABLE 5.

Antibodies used for in vitro MAIT activation assaya

| Antibody | Clone | Tetramer/surface |

|---|---|---|

| MR1 5-OP-RU-BV421 | — | Tetramer |

| CD8-BUV563 | RPA-T8 | Surface |

| CD4-BUV737 | SK3 | Surface |

| CD3-BUV395 | SP34-2 | Surface |

| CD69-PE Texas Red | TP1.55.3 | Surface |

| HLA-DR BV650 | G46-6 | Surface |

| CD25-APC | BC96 | Surface |

| LIVE/DEAD Near IR ARD | — | — |

—, not applicable.

TABLE 6.

MAIT in vitro and ex vivo functional assaysa

| Antibody | Clone | Tetramer/surface/intracellular |

|---|---|---|

| MR1 5-OP-RU-BV421 | — | Tetramer |

| CD3-BUV396 | SP34-2 | Surface |

| CD4-BUV737 | SK3 | Surface |

| CD8-BUV563 | RPA-T8 | Surface |

| CD107a-BV605 | H4A3 | Surface |

| IFN-γ-FITC | 4S.B3 | Intracellular |

| TNF-α-AF700 | Mab11 | Intracellular |

| LIVE/DEAD Near IR ARD | — | — |

—, not applicable.

TABLE 7.

MAIT BAL functional assaya

| Antibody | Clone | Tetramer/surface/intracellular |

|---|---|---|

| MR1 5-OP-RU-BV421 | — | Tetramer |

| TCRVα7.2-BV605 | 3C10 | Surface |

| CD107a-APC | H4A3 | Surface |

| CD3-AF700 | SP34-2 | Surface |

| CD4-BV510 | L200 | Surface |

| CD8-BV786 | RPA-T8 | Surface |

| CCR6-PE Cy7 | 11A9 | Surface |

| IFN-γ-FITC | 4S.B3 | Intracellular |

| TNF-α-PerCP Cy5.5 | Mab11 | Intracellular |

| LIVE/DEAD Near IR ARD | — | — |

—, not applicable.

In vitro MAIT cell activation assays with N-803.

(i) MAIT cell isolation. The MAIT cells were isolated from the cryopreserved PBMC of SIV-naive macaques by adding 10 μL of TCRVα7.2-PE (clone 3C10, Biolegend; San Diego, CA) for every 5e6 cells and incubating for 20 min at 4°C. Then, the PE-labeled cells were isolated using a MACS Miltenyi PE microbeads kit, according to the manufacturer’s protocol (130-097-054; MACS Miltenyi, Auburn CA). Following isolation, cells were used for in vitro N-803 activation assays (described below).

(ii) N-803 administration and staining for activation markers on MAIT cells. Bulk cryopreserved PBMC from SIV-naive macaques or MAIT cells isolated using TCRVα7.2-PE (described above) from the frozen PBMC were suspended in RPMI supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 100 units/mL of penicillin/streptomycin (Thermo Fisher Scientific; Waltham, MA); and 2 mM l-glutamine (Thermo Fisher Scientific; Waltham, MA). The indicated concentrations of N-803 or recombinant human IL-15 (rhIL-15, Peprotech; Cranbury, NJ) were added to the media and then incubated overnight at 37°C. The following day, the cells were collected and stained with the antibodies indicated in the panel below (Table 5). The flow cytometry was performed as described above.

In vitro and ex vivo MAIT cell functional assays.

(i) In vitro MAIT cell functional assays. Functional assays were performed using cryopreserved PBMC and LN from SIV-naive and SIV+ macaques as well as freshly isolated lymphocytes from the lungs of SIV+ macaques. The cells were incubated overnight at 37°C in 96-well plates in RPMI supplemented with 15% FBS along with the indicated concentrations of N-803, recombinant IL-7 (rhIL-7; Biolegend; San Diego, CA), or media control. The following day, the PBMC that were incubated overnight in various cytokines or media control were counted, and functional assays were performed. Briefly, fixed E. coli, M. smegmatis, and M. bovis (Bacillus Calmette-Guerin; BCG) stimuli were prepared, as described in (7, 34), by fixing bacteria in 2% paraformaldehyde for 2 to 3 min, followed by three washes with 1× phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and resuspension in RPMI media supplemented with 15% FBS. 10 colony forming units (CFU) of fixed E. coli, M. smegmatis, or BCG were added for every one cell present per well. The cells were incubated with the bacteria for 90 min at 37°C, and then brefeldin A and monensin were added along with 5 μL of CD107a-BV605. The cells were incubated for another 6 h, and then staining was performed as indicated above, using the antibodies listed in Table 6. For the functional assays performed with the whole-cell lysates from Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb) strain H37Rv, 100 μg/mL of Mtb lysates were added to the cells and incubated for 2 h at 37°C. Then, brefeldin A and monensin were added along with 5 μL of CD107a-BV605. The cells were incubated for another 16 h, and then staining was performed as indicated in Table 6. For the functional assays performed with the MR1 blocking antibody, the cells were preincubated for 1 h with 50 μg/mL of MR1 antibody (clone 26.5). Then, cytokines and bacteria were added as described above. The flow cytometry was performed as described above.

(ii) Ex vivo MAIT cell functional assays performed with cryopreserved PBMC collected from N-803 treated macaques. Cryopreserved PBMC originally collected from macaques treated with N-803 were thawed from the indicated time points pre- and post-N-803 treatment. The thawed cells were rested for 4 h. Then, 10 CFU of fixed E. coli or M. smegmatis were added for every one cell present in the tube. The cells and bacteria were incubated together for 90 min at 37°C, and then brefeldin A, monensin, and CD107a-BV605 were added. The cells were incubated overnight at 37°C. The following day, the cells were stained as indicated in Table 6, and the flow cytometric analysis was performed as described above.

(iii) Ex vivo MAIT cell functional assays performed with freshly isolated BAL fluid collected from N-803 treated macaques. BAL fluid was collected and processed as indicated above. Then, for every one cell present, 10 CFU of either fixed E. coli or M. smegmatis were added to the appropriate tubes, as described above. The cells and bacteria were incubated for 90 min at 37°C, and then brefeldin A, monensin, and CD107a-APC were added. The cells were incubated for 6 h at 37°C and then stained as indicated in Table 7. The flow cytometry was performed as described above.

Statistical analysis.

For the statistical analyses performed with the same individuals across multiple time points, repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) nonparametric tests were performed with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons (Prism GraphPad). For individuals with missing time points, mixed-effects ANOVA tests were performed using the Geisser-Greenhouse correction.

For the statistical analyses in which two time points were being compared to each other for the same individuals, Wilcoxon matched pairs signed-rank tests were performed.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the staff at the Wisconsin National Primate Resource Center (WNPRC) for their excellent veterinary care of the animals involved in this study.

This study was supported by funding supplied through the National Institutes of Health (NIH R01 grant number AI108415).

This research was conducted at a facility constructed with support from Research Facilities Improvement Program grant numbers RR15459-01 and RR020141-01. The Wisconsin National Primate Research Center is also supported by grants P51RR000167 and P51OD011106.

Jeffrey T. Safrit is an employee of ImmunityBio, which supplied the N-803 for this study.

Footnotes

Supplemental material is available online only.

Contributor Information

Shelby L. O’Connor, Email: slfeinberg@wisc.edu.

Sabine Ehrt, Weill Cornell Medical College.

REFERENCES

- 1.Porcelli S, Yockey CE, Brenner MB, Balk SP. 1993. Analysis of T cell antigen receptor (TCR) expression by human peripheral blood CD4-8- alpha/beta T cells demonstrates preferential use of several V beta genes and an invariant TCR alpha chain. J Exp Med 178:1–16. 10.1084/jem.178.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tilloy F, Treiner E, Park SH, Garcia C, Lemonnier F, de la Salle H, Bendelac A, Bonneville M, Lantz O. 1999. An invariant T cell receptor alpha chain defines a novel TAP-independent major histocompatibility complex class Ib-restricted alpha/beta T cell subpopulation in mammals. J Exp Med 189:1907–1921. 10.1084/jem.189.12.1907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Treiner E, Duban L, Bahram S, Radosavljevic M, Wanner V, Tilloy F, Affaticati P, Gilfillan S, Lantz O. 2003. Selection of evolutionarily conserved mucosal-associated invariant T cells by MR1. Nature 422:164–169. 10.1038/nature01433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Godfrey DI, Koay HF, McCluskey J, Gherardin NA. 2019. The biology and functional importance of MAIT cells. Nat Immunol 20:1110–1128. 10.1038/s41590-019-0444-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kjer-Nielsen L, Patel O, Corbett AJ, Le Nours J, Meehan B, Liu L, Bhati M, Chen Z, Kostenko L, Reantragoon R, Williamson NA, Purcell AW, Dudek NL, McConville MJ, O'Hair RAJ, Khairallah GN, Godfrey DI, Fairlie DP, Rossjohn J, McCluskey J. 2012. MR1 presents microbial vitamin B metabolites to MAIT cells. Nature 491:717–723. 10.1038/nature11605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Corbett AJ, Eckle SB, Birkinshaw RW, Liu L, Patel O, Mahony J, Chen Z, Reantragoon R, Meehan B, Cao H, Williamson NA, Strugnell RA, Van Sinderen D, Mak JY, Fairlie DP, Kjer-Nielsen L, Rossjohn J, McCluskey J. 2014. T-cell activation by transitory neo-antigens derived from distinct microbial pathways. Nature 509:361–365. 10.1038/nature13160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dias J, Sobkowiak MJ, Sandberg JK, Leeansyah E. 2016. Human MAIT-cell responses to Escherichia coli: activation, cytokine production, proliferation, and cytotoxicity. J Leukoc Biol 100:233–240. 10.1189/jlb.4TA0815-391RR. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gold MC, Cerri S, Smyk-Pearson S, Cansler ME, Vogt TM, Delepine J, Winata E, Swarbrick GM, Chua WJ, Yu YY, Lantz O, Cook MS, Null MD, Jacoby DB, Harriff MJ, Lewinsohn DA, Hansen TH, Lewinsohn DM. 2010. Human mucosal associated invariant T cells detect bacterially infected cells. PLoS Biol 8:e1000407. 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Meierovics A, Yankelevich WJ, Cowley SC. 2013. MAIT cells are critical for optimal mucosal immune responses during in vivo pulmonary bacterial infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 110:E3119–E3128. 10.1073/pnas.1302799110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen Z, Wang H, D'Souza C, Sun S, Kostenko L, Eckle SBG, Meehan BS, Jackson DC, Strugnell RA, Cao H, Wang N, Fairlie DP, Liu L, Godfrey DI, Rossjohn J, McCluskey J, Corbett AJ. 2017. Mucosal-associated invariant T-cell activation and accumulation after in vivo infection depends on microbial riboflavin synthesis and co-stimulatory signals. Mucosal Immunol 10:58–68. 10.1038/mi.2016.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Georgel P, Radosavljevic M, Macquin C, Bahram S. 2011. The non-conventional MHC class I MR1 molecule controls infection by Klebsiella pneumoniae in mice. Mol Immunol 48:769–775. 10.1016/j.molimm.2010.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dias J, Leeansyah E, Sandberg JK. 2017. Multiple layers of heterogeneity and subset diversity in human MAIT cell responses to distinct microorganisms and to innate cytokines. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 114:E5434–E5443. 10.1073/pnas.1705759114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Leeansyah E, Boulouis C, Kwa ALH, Sandberg JK. 2021. Emerging role for MAIT cells in control of antimicrobial resistance. Trends Microbiol 29:504–516. 10.1016/j.tim.2020.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Birkinshaw RW, Kjer-Nielsen L, Eckle SB, McCluskey J, Rossjohn J. 2014. MAITs, MR1 and vitamin B metabolites. Curr Opin Immunol 26:7–13. 10.1016/j.coi.2013.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sattler A, Dang-Heine C, Reinke P, Babel N. 2015. IL-15 dependent induction of IL-18 secretion as a feedback mechanism controlling human MAIT-cell effector functions. Eur J Immunol 45:2286–2298. 10.1002/eji.201445313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ussher JE, Bilton M, Attwod E, Shadwell J, Richardson R, de Lara C, Mettke E, Kurioka A, Hansen TH, Klenerman P, Willberg CB. 2014. CD161++ CD8+ T cells, including the MAIT cell subset, are specifically activated by IL-12+IL-18 in a TCR-independent manner. Eur J Immunol 44:195–203. 10.1002/eji.201343509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Leeansyah E, Svärd J, Dias J, Buggert M, Nyström J, Quigley MF, Moll M, Sönnerborg A, Nowak P, Sandberg JK. 2015. Arming of MAIT cell cytolytic antimicrobial activity is induced by IL-7 and defective in HIV-1 infection. PLoS Pathog 11:e1005072. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jones RB, Mueller S, O'Connor R, Rimpel K, Sloan DD, Karel D, Wong HC, Jeng EK, Thomas AS, Whitney JB, Lim S-Y, Kovacs C, Benko E, Karandish S, Huang S-H, Buzon MJ, Lichterfeld M, Irrinki A, Murry JP, Tsai A, Yu H, Geleziunas R, Trocha A, Ostrowski MA, Irvine DJ, Walker BD. 2016. A subset of latency-reversing agents expose HIV-infected resting CD4+ T-cells to recognition by cytotoxic T-lymphocytes. PLoS Pathog 12:e1005545. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Webb GM, Li S, Mwakalundwa G, Folkvord JM, Greene JM, Reed JS, Stanton JJ, Legasse AW, Hobbs T, Martin LD, Park BS, Whitney JB, Jeng EK, Wong HC, Nixon DF, Jones RB, Connick E, Skinner PJ, Sacha JB. 2018. The human IL-15 superagonist ALT-803 directs SIV-specific CD8+ T cells into B-cell follicles. Blood Adv 2:76–84. 10.1182/bloodadvances.2017012971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McBrien JB, Mavigner M, Franchitti L, Smith SA, White E, Tharp GK, Walum H, Busman-Sahay K, Aguilera-Sandoval CR, Thayer WO, Spagnuolo RA, Kovarova M, Wahl A, Cervasi B, Margolis DM, Vanderford TH, Carnathan DG, Paiardini M, Lifson JD, Lee JH, Safrit JT, Bosinger SE, Estes JD, Derdeyn CA, Garcia JV, Kulpa DA, Chahroudi A, Silvestri G. 2020. Robust and persistent reactivation of SIV and HIV by N-803 and depletion of CD8+ cells. Nature 578:154–159. 10.1038/s41586-020-1946-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McBrien JB, Wong AKH, White E, Carnathan DG, Lee JH, Safrit JT, Vanderford TH, Paiardini M, Chahroudi A, Silvestri G. 2020. Combination of CD8β depletion and interleukin-15 superagonist N-803 induces virus reactivation in simian-human immunodeficiency virus-infected, long-term ART-treated rhesus macaques. J Virol 94. 10.1128/JVI.00755-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ellis-Connell AL, Balgeman AJ, Zarbock KR, Barry G, Weiler A, Egan JO, Jeng EK, Friedrich T, Miller JS, Haase AT, Schacker TW, Wong HC, Rakasz E, O'Connor SL. 2018. ALT-803 transiently reduces simian immunodeficiency virus replication in the absence of antiretroviral treatment. J Virol 92. 10.1128/JVI.01748-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Han KP, Zhu X, Liu B, Jeng E, Kong L, Yovandich JL, Vyas VV, Marcus WD, Chavaillaz PA, Romero CA, Rhode PR, Wong HC. 2011. IL-15:IL-15 receptor alpha superagonist complex: high-level co-expression in recombinant mammalian cells, purification and characterization. Cytokine 56:804–810. 10.1016/j.cyto.2011.09.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wong HC, Jeng EK, Rhode PR. 2013. The IL-15-based superagonist ALT-803 promotes the antigen-independent conversion of memory CD8+ T cells into innate-like effector cells with antitumor activity. Oncoimmunology 2:e26442. 10.4161/onci.26442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhu X, Marcus WD, Xu W, Lee HI, Han K, Egan JO, Yovandich JL, Rhode PR, Wong HC. 2009. Novel human interleukin-15 agonists. J Immunol 183:3598–3607. 10.4049/jimmunol.0901244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xu W, Jones M, Liu B, Zhu X, Johnson CB, Edwards AC, Kong L, Jeng EK, Han K, Marcus WD, Rubinstein MP, Rhode PR, Wong HC. 2013. Efficacy and mechanism-of-action of a novel superagonist interleukin-15: interleukin-15 receptor αSu/Fc fusion complex in syngeneic murine models of multiple myeloma. Cancer Res 73:3075–3086. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-2357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rhode PR, Egan JO, Xu W, Hong H, Webb GM, Chen X, Liu B, Zhu X, Wen J, You L, Kong L, Edwards AC, Han K, Shi S, Alter S, Sacha JB, Jeng EK, Cai W, Wong HC. 2016. Comparison of the superagonist complex, ALT-803, to IL15 as cancer immunotherapeutics in animal models. Cancer Immunol Res 4:49–60. 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-15-0093-T. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rosario M, Liu B, Kong L, Collins LI, Schneider SE, Chen X, Han K, Jeng EK, Rhode PR, Leong JW, Schappe T, Jewell BA, Keppel CR, Shah K, Hess B, Romee R, Piwnica-Worms DR, Cashen AF, Bartlett NL, Wong HC, Fehniger TA. 2016. The IL-15-based ALT-803 complex enhances FcγRIIIa-triggered NK cell responses and in vivo clearance of B cell lymphomas. Clin Cancer Res 22:596–608. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-1419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Margolin K, Morishima C, Velcheti V, Miller JS, Lee SM, Silk AW, Holtan SG, Lacroix AM, Fling SP, Kaiser JC, Egan JO, Jones M, Rhode PR, Rock AD, Cheever MA, Wong HC, Ernstoff MS. 2018. Phase I trial of ALT-803, a novel recombinant IL15 complex, in patients with advanced solid tumors. Clin Cancer Res 24:5552–5561. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-18-0945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wrangle JM, Velcheti V, Patel MR, Garrett-Mayer E, Hill EG, Ravenel JG, Miller JS, Farhad M, Anderton K, Lindsey K, Taffaro-Neskey M, Sherman C, Suriano S, Swiderska-Syn M, Sion A, Harris J, Edwards AR, Rytlewski JA, Sanders CM, Yusko EC, Robinson MD, Krieg C, Redmond WL, Egan JO, Rhode PR, Jeng EK, Rock AD, Wong HC, Rubinstein MP. 2018. ALT-803, an IL-15 superagonist, in combination with nivolumab in patients with metastatic non-small cell lung cancer: a non-randomised, open-label, phase 1b trial. Lancet Oncol 19:694–704. 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30148-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Miller JS, Davis ZB, Helgeson E, Reilly C, Thorkelson A, Anderson J, Lima NS, Jorstad S, Hart GT, Lee JH, Safrit JT, Wong H, Cooley S, Gharu L, Chung H, Soon-Shiong P, Dobrowolski C, Fletcher CV, Karn J, Douek DC, Schacker TW. 2022. Safety and virologic impact of the IL-15 superagonist N-803 in people living with HIV: a phase 1 trial. Nat Med 28:392–400. 10.1038/s41591-021-01651-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Greene JM, Dash P, Roy S, McMurtrey C, Awad W, Reed JS, Hammond KB, Abdulhaqq S, Wu HL, Burwitz BJ, Roth BF, Morrow DW, Ford JC, Xu G, Bae JY, Crank H, Legasse AW, Dang TH, Greenaway HY, Kurniawan M, Gold MC, Harriff MJ, Lewinsohn DA, Park BS, Axthelm MK, Stanton JJ, Hansen SG, Picker LJ, Venturi V, Hildebrand W, Thomas PG, Lewinsohn DM, Adams EJ, Sacha JB. 2017. MR1-restricted mucosal-associated invariant T (MAIT) cells respond to mycobacterial vaccination and infection in nonhuman primates. Mucosal Immunol 10:802–813. 10.1038/mi.2016.91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Juno JA, Wragg KM, Amarasena T, Meehan BS, Mak JYW, Liu L, Fairlie DP, McCluskey J, Eckle SBG, Kent SJ. 2019. MAIT cells upregulate α4β7 in response to acute simian immunodeficiency virus/simian HIV infection but are resistant to peripheral depletion in pigtail macaques. J Immunol 202:2105–2120. 10.4049/jimmunol.1801405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ellis AL, Balgeman AJ, Larson EC, Rodgers MA, Ameel C, Baranowski T, Kannal N, Maiello P, Juno JA, Scanga CA, O'Connor SL. 2020. MAIT cells are functionally impaired in a Mauritian cynomolgus macaque model of SIV and Mtb co-infection. PLoS Pathog 16:e1008585. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1008585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jiang J, Wang X, An H, Yang B, Cao Z, Liu Y, Su J, Zhai F, Wang R, Zhang G, Cheng X. 2014. Mucosal-associated invariant T-cell function is modulated by programmed death-1 signaling in patients with active tuberculosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 190:329–339. 10.1164/rccm.201401-0106OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jiang J, Yang B, An H, Wang X, Liu Y, Cao Z, Zhai F, Wang R, Cao Y, Cheng X. 2016. Mucosal-associated invariant T cells from patients with tuberculosis exhibit impaired immune response. J Infect 72:338–352. 10.1016/j.jinf.2015.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Khuzwayo S, Mthembu M, Meermeier EW, Prakadan SM, Kazer SW, Bassett T, Nyamande K, Khan DF, Maharaj P, Mitha M, Suleman M, Mhlane Z, Ramjit D, Karim F, Shalek AK, Lewinsohn DM, Ndung'u T, Wong EB. 2021. MR1-restricted MAIT cells from the human lung mucosal surface have distinct phenotypic, functional, and transcriptomic features that are preserved in HIV infection. Front Immunol 12:631410. 10.3389/fimmu.2021.631410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Voillet V, Buggert M, Slichter CK, Berkson JD, Mair F, Addison MM, Dori Y, Nadolski G, Itkin MG, Gottardo R, Betts MR, Prlic M. 2018. Human MAIT cells exit peripheral tissues and recirculate via lymph in steady state conditions. JCI Insight 3. 10.1172/jci.insight.98487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ellis-Connell AL, Balgeman AJ, Harwood OE, Moriarty RV, Safrit JT, Weiler AM, Friedrich TC, O’Connor SL. 2022. Control of SIV infection in prophylactically vaccinated, ART-naïve macaques is required for the most efficacious CD8 T cell response during treatment with the IL-15 superagonist N-803. bioRxiv. 2022.06.02.494515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 40.Webb GM, Molden J, Busman-Sahay K, Abdulhaqq S, Wu HL, Weber WC, Bateman KB, Reed JS, Northrup M, Maier N, Tanaka S, Gao L, Davey B, Carpenter BL, Axthelm MK, Stanton JJ, Smedley J, Greene JM, Safrit JT, Estes JD, Skinner PJ, Sacha JB. 2020. The human IL-15 superagonist N-803 promotes migration of virus-specific CD8+ T and NK cells to B cell follicles but does not reverse latency in ART-suppressed, SHIV-infected macaques. PLoS Pathog 16:e1008339. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1008339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Daudt L, Maccario R, Locatelli F, Turin I, Silla L, Montini E, Percivalle E, Giugliani R, Avanzini MA, Moretta A, Montagna D. 2008. Interleukin-15 favors the expansion of central memory CD8+ T cells in ex vivo generated, antileukemia human cytotoxic T lymphocyte lines. J Immunother 31:385–393. 10.1097/CJI.0b013e31816b1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Picker LJ, Reed-Inderbitzin EF, Hagen SI, Edgar JB, Hansen SG, Legasse A, Planer S, Piatak M, Lifson JD, Maino VC, Axthelm MK, Villinger F. 2006. IL-15 induces CD4 effector memory T cell production and tissue emigration in nonhuman primates. J Clin Invest 116:1514–1524. 10.1172/JCI27564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lugli E, Goldman CK, Perera LP, Smedley J, Pung R, Yovandich JL, Creekmore SP, Waldmann TA, Roederer M. 2010. Transient and persistent effects of IL-15 on lymphocyte homeostasis in nonhuman primates. Blood 116:3238–3248. 10.1182/blood-2010-03-275438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mueller YM, Petrovas C, Bojczuk PM, Dimitriou ID, Beer B, Silvera P, Villinger F, Cairns JS, Gracely EJ, Lewis MG, Katsikis PD. 2005. Interleukin-15 increases effector memory CD8+ t cells and NK Cells in simian immunodeficiency virus-infected macaques. J Virol 79:4877–4885. 10.1128/JVI.79.8.4877-4885.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sneller MC, Kopp WC, Engelke KJ, Yovandich JL, Creekmore SP, Waldmann TA, Lane HC. 2011. IL-15 administered by continuous infusion to rhesus macaques induces massive expansion of CD8+ T effector memory population in peripheral blood. Blood 118:6845–6848. 10.1182/blood-2011-09-377804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mahnke YD, Brodie TM, Sallusto F, Roederer M, Lugli E. 2013. The who’s who of T-cell differentiation: human memory T-cell subsets. Eur J Immunol 43:2797–2809. 10.1002/eji.201343751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Leong YA, Chen Y, Ong HS, Wu D, Man K, Deleage C, Minnich M, Meckiff BJ, Wei Y, Hou Z, Zotos D, Fenix KA, Atnerkar A, Preston S, Chipman JG, Beilman GJ, Allison CC, Sun L, Wang P, Xu J, Toe JG, Lu HK, Tao Y, Palendira U, Dent AL, Landay AL, Pellegrini M, Comerford I, McColl SR, Schacker TW, Long HM, Estes JD, Busslinger M, Belz GT, Lewin SR, Kallies A, Yu D. 2016. CXCR5(+) follicular cytotoxic T cells control viral infection in B cell follicles. Nat Immunol 17:1187–1196. 10.1038/ni.3543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ferrando-Martinez S, Moysi E, Pegu A, Andrews S, Nganou Makamdop K, Ambrozak D, McDermott AB, Palesch D, Paiardini M, Pavlakis GN, Brenchley JM, Douek D, Mascola JR, Petrovas C, Koup RA. 2018. Accumulation of follicular CD8+ T cells in pathogenic SIV infection. J Clin Invest 128:2089–2103. 10.1172/JCI96207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jeyanathan M, Afkhami S, Khera A, Mandur T, Damjanovic D, Yao Y, Lai R, Haddadi S, Dvorkin-Gheva A, Jordana M, Kunkel SL, Xing Z. 2017. CXCR3 signaling is required for restricted homing of parenteral tuberculosis vaccine-induced T cells to both the lung parenchyma and airway. J Immunol 199:2555–2569. 10.4049/jimmunol.1700382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Slütter B, Pewe LL, Kaech SM, Harty JT. 2013. Lung airway-surveilling CXCR3(hi) memory CD8(+) T cells are critical for protection against influenza A virus. Immunity 39:939–948. 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.09.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ito T, Carson WF, Cavassani KA, Connett JM, Kunkel SL. 2011. CCR6 as a mediator of immunity in the lung and gut. Exp Cell Res 317:613–619. 10.1016/j.yexcr.2010.12.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Felices M, Chu S, Kodal B, Bendzick L, Ryan C, Lenvik AJ, Boylan KLM, Wong HC, Skubitz APN, Miller JS, Geller MA. 2017. IL-15 super-agonist (ALT-803) enhances natural killer (NK) cell function against ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol 145:453–461. 10.1016/j.ygyno.2017.02.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tao H, Pan Y, Chu S, Li L, Xie J, Wang P, Zhang S, Reddy S, Sleasman JW, Zhong XP. 2021. Differential controls of MAIT cell effector polarization by mTORC1/mTORC2 via integrating cytokine and costimulatory signals. Nat Commun 12:2029. 10.1038/s41467-021-22162-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Khader SA, Bell GK, Pearl JE, Fountain JJ, Rangel-Moreno J, Cilley GE, Shen F, Eaton SM, Gaffen SL, Swain SL, Locksley RM, Haynes L, Randall TD, Cooper AM. 2007. IL-23 and IL-17 in the establishment of protective pulmonary CD4+ T cell responses after vaccination and during Mycobacterium tuberculosis challenge. Nat Immunol 8:369–377. 10.1038/ni1449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Shanmugasundaram U, Bucsan AN, Ganatra SR, Ibegbu C, Quezada M, Blair RV, Alvarez X, Velu V, Kaushal D, Rengarajan J. 2020. Pulmonary Mycobacterium tuberculosis control associates with CXCR3- and CCR6-expressing antigen-specific Th1 and Th17 cell recruitment. JCI Insight 5 10.1172/jci.insight.137858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Acosta-Rodriguez EV, Rivino L, Geginat J, Jarrossay D, Gattorno M, Lanzavecchia A, Sallusto F, Napolitani G. 2007. Surface phenotype and antigenic specificity of human interleukin 17-producing T helper memory cells. Nat Immunol 8:639–646. 10.1038/ni1467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Liu H, Rohowsky-Kochan C. 2008. Regulation of IL-17 in human CCR6+ effector memory T cells. J Immunol 180:7948–7957. 10.4049/jimmunol.180.12.7948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Shen H, Chen ZW. 2018. The crucial roles of Th17-related cytokines/signal pathways in M. tuberculosis infection. Cell Mol Immunol 15:216–225. 10.1038/cmi.2017.128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]