Abstract

Background

Multimorbidity (≥ 2 chronic diseases) is associated with greater disability and higher treatment burden, as well as difficulty coordinating self-management tasks for adults with complex multimorbidity patterns. Comparatively little work has focused on assessing multimorbidity patterns among patients seeking care in community health centers (CHCs).

Objective

To identify and characterize prevalent multimorbidity patterns in a multi-state network of CHCs over a 5-year period.

Design

A cohort study of the 2014–2019 ADVANCE multi-state CHC clinical data network. We identified the most prevalent multimorbidity combination patterns and assessed the frequency of patterns throughout a 5-year period as well as the demographic characteristics of patient panels by prevalent patterns.

Participants

The study included data from 838,642 patients aged ≥ 45 years who were seen in 337 CHCs across 22 states between 2014 and 2019.

Main measures

Prevalent multimorbidity patterns of somatic, mental health, and mental-somatic combinations of 22 chronic diseases based on the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Multiple Chronic Conditions framework: anxiety, arthritis, asthma, autism, cancer, cardiac arrhythmia, chronic kidney disease (CKD), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), congestive heart failure, coronary artery disease, dementia, depression, diabetes, hepatitis, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), hyperlipidemia, hypertension, osteoporosis, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), schizophrenia, substance use disorder, and stroke.

Key results

Multimorbidity is common among middle-aged and older patients seen in CHCs: 40% have somatic, 6% have mental health, and 24% have mental-somatic multimorbidity patterns. The most frequently occurring pattern across all years is hyperlipidemia-hypertension. The three most frequent patterns are various iterations of hyperlipidemia, hypertension, and diabetes and are consistent in rank of occurrence across all years. CKD-hyperlipidemia-hypertension and anxiety-depression are both more frequent in later study years.

Conclusions

CHCs are increasingly seeing more complex multimorbidity patterns over time; these most often involve mental health morbidity and advanced cardiometabolic-renal morbidity.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s11606-021-07198-2.

KEY WORDS: multimorbidity, multiple chronic conditions, community health centers, safety-net clinics, vulnerable populations

Background

There is growing recognition that multimorbidity (≥ 2 chronic diseases) is a significant public health problem with substantial associated penalties for patients—greater disability, lower quality of life, and earlier mortality1–3—as well as posing considerable challenges to health-care systems and public programs.4,5 While the prevalence of multimorbidity varies greatly by age, gender, race, and socioeconomic level, approximately one-half of middle-aged adults (50–65 years of age) have multimorbidity and over 80% of those 75 years of age and older have multimorbidity.3 The association between escalating chronic disease burden and poor health-related outcomes has been extensively documented, although earlier work has been limited to examining single diseases in isolation, specifying only dyads or triads of co-existing disease, or evaluating morbidity patterns at a static point in time.6,7

Comparatively little work has been done to understand multimorbidity combination patterns and the complexity of these patterns among vulnerable, low-income populations, particularly those who seek care in the US health-care safety net—a broad set of public health clinics and community health centers (CHCs). CHCs serve 30 million patients nationwide8 and provide health care to medically underserved populations, regardless of health insurance coverage, documentation status, or ability to pay. While CHCs provide excellent quality of care for their patients, these patients experience higher rates of unmet need and poorer health outcomes compared with patients who seek care outside of the safety net.9,10 Yet, little is known about the prevalence and multimorbidity combination patterns in these patients, especially in the presence of mental health disorders.11 Given the emphasis on “whole person care” and examining the totality of chronic diseases patients experience and manage, the inclusion of mental health conditions is critical to the study of multimorbidity. In order for CHCs to be responsive to the needs of the populations they serve, greater understanding is needed on the prevalence, complexity, and shifts in disease patterns over time.9,10.

CHC patients have a higher prevalence of individual somatic chronic conditions, such as hypertension, asthma, and diabetes,12,13 and greater levels of risk factors for these diseases, such as smoking and obesity. Additionally, among low-income populations, mental health conditions—including substance use disorders—are prevalent and often co-occur with somatic conditions.12,14 Studies in the UK indicate that patients in low-income areas (similar to CHC populations in the USA) develop multimorbidity 10–15 years earlier than those from wealthier areas, and the difference is even more significant for patients with mental disorders.15 The majority of these multimorbidity studies focus on older adult populations; it is unknown whether CHC patients in the USA develop multimorbidity earlier in the life course or whether they have different patterns of multimorbidity.

Overall, individuals with multimorbidity require ongoing chronic care disease support and are more likely to experience adverse health outcomes leading to premature disability and death. Specific chronic disease combination patterns may require individually tailored support and intervention (which may differ from support and intervention in response to individual disease burden), and may result in high volumes of complex patients that require strategies tailored to large patient panels16 in order to improve outcomes and prevent staff burnout. The purpose of our study is to identify the prevalence and patterns of multimorbidity combinations for middle-aged and older patients in a large, multi-state network of safety-net clinics. Given the high prevalence of chronic conditions and growing health-care needs within the safety-net population, understanding the distribution of specific multimorbidity combinations is of particular importance for informing strategies to optimize care delivery, reduce disparities, and address unmet health-care needs.

Methods

Data source

Electronic health record (EHR) data were obtained from the Accelerating Data Value Across a National Community Health Center Network (ADVANCE) multi-state clinical research network (CRN) of PCORNnet.17 ADVANCE represents a unique “community laboratory” of clinical data for research with underrepresented and vulnerable populations receiving care in CHCs (http://advancecollaborative.org). It is the largest collection of EHR data from individuals who receive care in US safety-net settings, and the ADVANCE patient population has been found to be representative of the overall CHC population in the USA.8,18,19.

Study cohort

We assessed data from 838,642 patients in 337 clinics active throughout the study period of 2014–2019, operated by 63 health systems in 22 states. Patient data were included if patients were ≥ 45 years of age by study end and if they had ≥ 1 office visit at an included primary care clinic during the study period. The study included data from patients up to their year of death (Appendix Fig. 4).

Dependent variable

We assessed multimorbidity combinations of 22 chronic diseases recommended by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Multiple Chronic Conditions framework for operationalizing multimorbidity20,21: anxiety, arthritis, asthma, autism, cancer, cardiac arrhythmia, chronic kidney disease (CKD), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), congestive heart failure, coronary artery disease, dementia, depression, diabetes, hepatitis, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), hyperlipidemia, hypertension, osteoporosis, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), schizophrenia, substance use disorder, and stroke. Chronic diseases were ascertained from EHR problem lists.22 We present the most prevalent combinations—those that met a threshold of having ≥ 1% of study patients in the combination—and rank order the prevalence throughout the study period. We also present socioeconomic and demographic characteristics of the most frequent multimorbidity combinations. We categorized combinations as (1) somatic multimorbidity (≥ 2 physical chronic diseases), (2) mental multimorbidity (≥ 2 mental health conditions), and (3) mental-somatic multimorbidity (at least one somatic and one mental health condition).

Independent variables

We assessed patient-level demographic and socioeconomic factors from EHR data. Patient death is reported as having occurred during the study period with a documented date from the EHR. The number of chronic diseases (chronic disease burden) and the average number of yearly visits were summarized by the mean and standard deviation (SD) as well as the median and interquartile range (IQR). Patient age is reported as first observed age in the clinical record and categorized as 38–44, 45–54, 55–64, and 65 + years (although multimorbidity or patient characteristics were not summarized until patients reached the age of 45). Race, ethnicity, and preferred language were used to create the mutually exclusive categories non-Hispanic White (White), non-Hispanic Black (Black), non-Hispanic Asian (Asian), non-Hispanic other (other), and Hispanic (Hispanic or of unknown ethnicity with Spanish language speaking preference). Categorical variables of visit-based characteristics, including patient household federal poverty level (FPL) (continuously < 138%, continuously ≥ 138%, or intermittently over/under 138%) and patient insurance coverage were assessed over the study period (continuously insured, continuously uninsured, intermittently insured).

Statistical analysis

We summarized patient characteristics overall, and by multimorbidity combination, with counts and percentages and used t tests and chi-square statistics to assess differences between groups. Next, we estimated the percentage of patients in each multimorbidity combination by the end of each study year and ranked ordered multimorbidity combinations by each study year. We visualized these rankings with heatmaps, overall and by sex, race/ethnicity, age category, and FPL. All time-varying patient characteristics are presented as the last observed value in the reported year. Type 1 error was set to 0.05. Analyses were performed using R version 4.0.1. The study protocol was approved by our university’s Institutional Review Board (IRB ID# STUDY00020124).

Results

Table 1 presents descriptive information for our patient sample across the study period. Over half of the patient sample had or developed multimorbidity by the end of the study period (n = 436,554; 52.1%). Among patients with multimorbidity, nearly half had somatic multimorbidity combinations (49.1%) and mental-somatic multimorbidity combinations (47.2%). Fewer patients had solely mental health multimorbidity combinations (3.8%). The mean age was lower for mental multimorbidity combinations (47.9 years) compared with somatic (56.4 years) and mental-somatic (53.5 years) combinations. The average number of yearly visits was highest in mental and mental-somatic multimorbidity combinations (4.8 and 5.0) than somatic multimorbidity combinations (3.9) although the former two combinations had standard deviations higher than their respective mean. Patients with mental-somatic multimorbidity combinations had higher average chronic disease burden (4.1), followed by patients with somatic multimorbidity combinations (3.0) and patients with mental multimorbidity combinations (2.3). Female (62.8%), White (62.2%), English-speaking (88.5%), and Medicaid-insured (74.7%) patients were overrepresented in mental multimorbidity combinations compared with their counterparts. White patients had greater proportions of mental multimorbidity combinations (62.2%) and mental-somatic multimorbidity combinations (54%). Black, Hispanic, and Asian groups were each more represented in somatic multimorbidity combinations than mental or mental-somatic multimorbidity combinations.

Table 1.

Study Sample Characteristics Overall and by Multimorbidity Categories, ADVANCE data 2014–2019

| Overall | Somatic multimorbidity | Mental multimorbidity | Mental-somatic multimorbidity | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | 838,642 | 214,178 (25.5) | 16,404 (2.0) | 205,972 (24.6) | |

| Death, n (%) | < 0.001 | ||||

| Yes | 17,989 (2.1) | 6,346 (3.0) | 218 (1.3) | 8,137 (4.0) | |

| No | 820,653 (97.9) | 207,832 (97.0) | 16.186 (98.7) | 197,835 (96.0) | |

| Chronic disease burden, n (%) | |||||

| 0 or 1 disease | 402,088 (47.9) | ||||

| ≥ 2 diseases (multimorbidity) | 436,554 (52.1) | 214,178 (49.1) | 16,404 (3.8) | 205,972 (47.2) | |

| Chronic disease burden, mean (SD) | 2.0 (1.9) | 3.0 (1.1) | 2.3 (0.6) | 4.1 (1.7) | < 0.001 |

| Chronic disease burden, median (IQR) | 2.0 (0.0–3.0) | 3.0 (2.0–4.0) | 2.0 (2.0–3.0) | 4.0 (3.0–5.0) | < 0.001 |

| Average number of yearly visits, mean (SD) | 3.5 (4.0) | 3.9 (2.7) | 4.8 (6.7) | 5.0 (6.2) | < 0.001 |

| Average number of yearly visits, median (IQR) | 2.7 (1.5–4.2) | 3.3 (2.0–4.8) | 3.0 (2.0–5.3) | 4.0 (2.5–6.0) | < 0.001 |

| First observed age, mean (SD) | 53.0 (9.9) | 56.4 (10.3) | 47.9 (7.3) | 53.5 (9.7) | < 0.001 |

| Sex, n (%) | |||||

| Female | 467,844 (55.8) | 112,894 (52.7) | 10,302 (62.8) | 122,763 (59.6) | < 0.001 |

| Male | 370,798 (44.2) | 101,284 (47.3) | 6102 (37.2) | 83,209 (40.4) | |

| Race/ethnicity, n (%) | |||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 358,230 (42.7) | 78,406 (36.6) | 10,210 (62.2) | 111,214 (54.0) | < 0.001 |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 150,085 (17.9) | 49,390 (23.1) | 1649 (10.1) | 31,401 (15.2) | |

| Hispanic | 242,151 (28.9) | 63,996 (29.9) | 2842 (17.3) | 45,448 (22.1) | |

| Non-Hispanic Asian | 21,699 (2.6) | 7018 (3.3) | 184 (1.1) | 2891 (1.4) | |

| Non-Hispanic other | 10,295 (1.2) | 2590 (1.2) | 310 (1.9) | 3039 (1.5) | |

| Unknown | 56,182 (6.7) | 12,778 (6.0) | 1209 (7.4) | 11,979 (5.8) | |

| Language, n (%) | |||||

| English | 642,434 (76.6) | 158,727 (74.1) | 14,514 (88.5) | 172,051 (83.5) | < 0.001 |

| Spanish | 160,755 (19.2) | 44,945 (21.0) | 1450 (8.8) | 28,221 (13.7) | |

| Other | 35,453 (4.2) | 10,506 (4.9) | 440 (2.7) | 5700 (2.8) | |

| Insurance status, n (%) | |||||

| Continuously uninsured | 185,105 (22.1) | 35,496 (16.6) | 2288 (13.9) | 20,914 (10.2) | < 0.001 |

| Continuously insured | 431,420 (51.4) | 108,372 (50.6) | 8631 (52.6) | 107,215 (52.1) | |

| Intermittently insured | 222,117 (26.5) | 70,310 (32.8) | 5485 (33.4) | 77,843 (37.8) | |

| Visit-based characteristics at the patient level | |||||

| FPL, n (%) | |||||

| Continuously < 138% | 538,140 (73.0) | 135,252 (70.7) | 11,008 (74.9) | 137,283 (73.2) | < 0.001 |

| Continuously ≥ 138% | 105,926 (14.4) | 25,671 (13.4) | 1621 (11.0) | 18,248 (9.7) | |

| Intermittently over/under | 93,480 (12.7) | 30,297 (15.8) | 2075 (14.1) | 32,029 (17.1) | |

| Insurance type (age < 65) | |||||

| Disability | 83,140 (24.9) | 21,492 (26.6) | 2598 (24.6) | 38,884 (31.8) | |

| Medicaid | 236,877 (71.0) | 52,778 (65.2) | 7903 (74.7) | 79,338 (65.0) | |

| Other | 13,703 (4.1) | 6671 (8.2) | 73 (0.7) | 3901 (3.2) | |

| Insurance type (age ≥ 65) | |||||

| Dual eligible | 13,859 (9.2) | 6044 (9.6) | 117 (11.9) | 5846 (12.7) | |

| Medicaid 65 + | 14,955 (9.9) | 5964 (9.5) | 111 (11.3) | 3518 (7.6) | |

| Medicare | 120,798 (80.1) | 50,276 (80.1) | 737 (74.7) | 36,459 (78.9) | |

| Other | 1140 (0.8) | 466 (0.7) | 21 (2.1) | 360 (0.8) | |

Somatic multimorbidity comprises 15 chronic diseases (arthritis, asthma, cancer, cardiac arrhythmia, chronic kidney disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, congestive heart failure, coronary artery disease, diabetes, hepatitis, human immunodeficiency virus, hyperlipidemia, hypertension, osteoporosis, stroke). Mental multimorbidity comprises 7 chronic conditions (anxiety, autism, dementia, depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, schizophrenia, substance use disorder). Mental-somatic multimorbidity comprises any combination of ≥ 1 somatic and ≥ 1 mental chronic condition. For insurance types prior to age 65 and 65 + , “other” is defined as private insurance, other public insurance, or uninsured. Visit-based characteristics were summarized at the patient level; therefore, if patients did not have a visit, or an encounter, they were not included in the summarized variable and may not necessarily add to the total number of patients of 838,642 or any of the stratified multimorbidity categories

SD standard deviation, IQR inter-quartile range, FPL federal poverty level

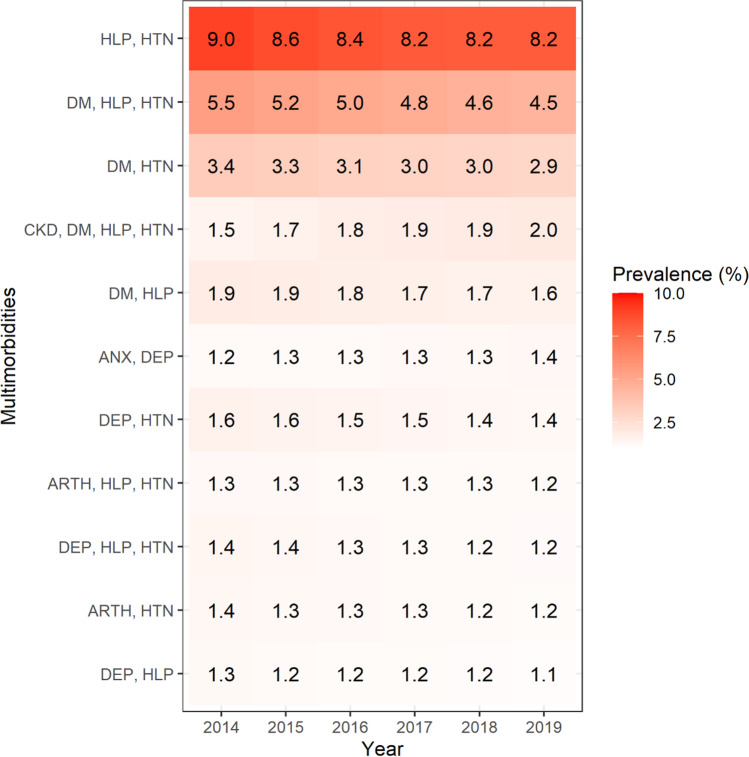

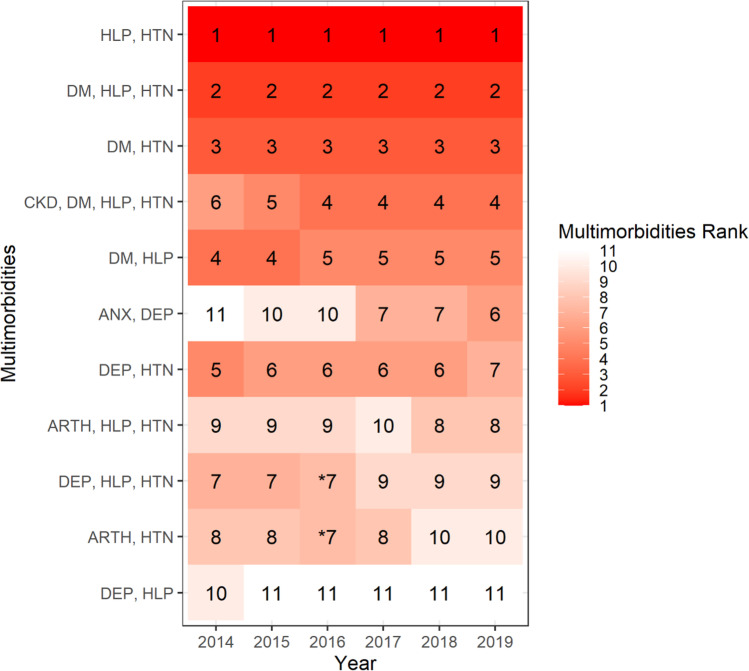

There were 24,169 unique multimorbidity combinations that characterized this clinical patient sample. Only 11 multimorbidity combinations met the 1% prevalence threshold and represent the most frequently occurring chronic disease patterns seen in this sample. Figures 1 and 2 present the percentages and the rank order of these multimorbidity combinations during each year. The top three prevalent multimorbidity combinations across all years were somatic multimorbidity combinations: hyperlipidemia-hypertension (ranging from 9% in 2014 to 8.2% in 2019), followed by diabetes-hyperlipidemia-hypertension (5.5% in 2014 to 4.5% in 2019) and diabetes-hypertension (3.4% in 2014 to 2.9% in 2019). Only two multimorbidity combination patterns demonstrated an increasing prevalence trend across the study years: CKD-diabetes-hyperlipidemia-hypertension (1.5% in 2014 to 2% by 2019) and anxiety-depression (1.2% in 2014 to 1.4% by 2019). Notably, the largest increase in rank order occurred for anxiety-depression, which started ranked 11th and ended as the 6th most prevalent multimorbidity combination (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

Heatmap of percentage of patients comprising the most prevalent multimorbidity combinations, ADVANCE data 2014–2019. Abbreviations: HLP = hyperlipidemia; HTN = hypertension; DM = diabetes; CKD = chronic kidney disease; DEP = depression; ANX = anxiety; ARTH = arthritis. Notes: The most prevalent combinations were those that met a threshold of having ≥ 1% of patients in the combination. Each number represents the percentage where the numerator is the number of patients with a multimorbidity combination in the respective year and the denominator is the total number of patients with multimorbidity in the respective year. Greater shading intensity corresponds to larger percentages for the group

Fig. 2.

Heatmap of rank order of the most prevalent multimorbidity combinations, ADVANCE data 2014–2019. Abbreviations: HLP = hyperlipidemia; HTN = hypertension; DM = diabetes; CKD = chronic kidney disease; DEP = depression; ANX = anxiety; ARTH = arthritis. Notes: The most prevalent combinations were those that met a threshold of having ≥ 1% of patients in the combination. “*” Represents tied rank. The number represents the rank order of the most prevalent multimorbidity combinations where the numerator is the number of patients with the multimorbidity combination in the respective year and the denominator is the total number of patients with multimorbidity in the respective year. Greater shading intensity corresponds to higher rank of the group

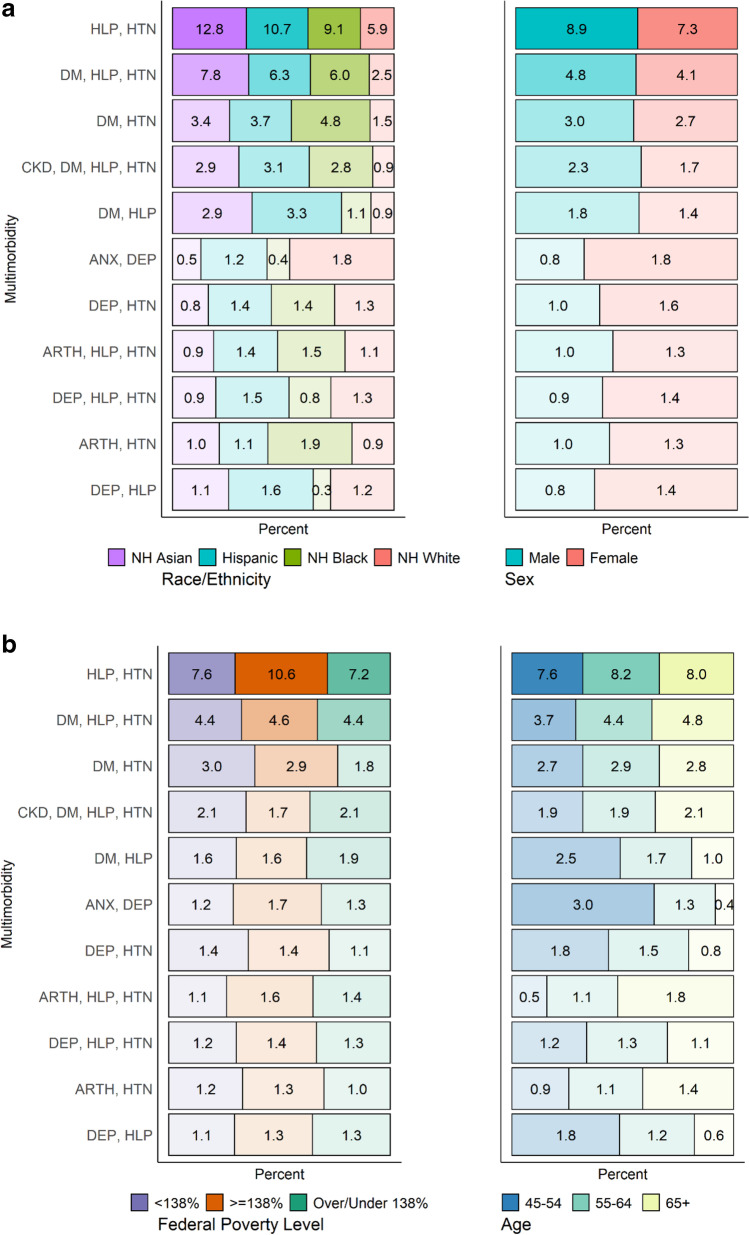

Figure 3a and b display sociodemographic patient characteristics for the 11 most frequently occurring multimorbidity combinations in the last year of the study period (2019). Differences by race/ethnicity are stark across groups within specific multimorbidity combinations. White patients comprised a smaller proportion of nearly every multimorbidity combination group with the exception of anxiety-depression (ranked 6th). Asian patients were the highest racial/ethnic group represented in the hyperlipidemia-hypertension and diabetes-hyperlipidemia-hypertension combinations (ranked 1st and 2nd), Black patients represented the largest proportion of the diabetes-hypertension combination (ranked 3rd), and Hispanic patients comprised the largest proportion of the diabetes-hyperlipidemia combination (ranked 5th). Males were more represented in the first five ranked combinations (all somatic multimorbidity combinations), and females were more represented in the last six ordered combinations (a mix of somatic, mental, and mental-somatic multimorbidity). Multimorbidity combinations were largely similar across FPL groups. Lastly, age strata were evenly distributed for most of the multimorbidity combinations with the exception of diabetes-hyperlipidemia, anxiety-depression, depression-hypertension, and depression-hyperlipidemia, all of which were most prevalent among the youngest age category of 45–54 years. Arthritis-hyperlipidemia-hypertension and arthritis-hypertension were more common among those aged ≥ 65 years.

Fig. 3.

a Heatmap of prevalent multimorbidity combinations by patient demographic characteristics, ADVANCE data 2019. Abbreviations: HLP = hyperlipidemia; HTN = hypertension; DM = diabetes; CKD = chronic kidney disease; DEP = depression; ANX = anxiety; ARTH = arthritis. Notes: The most prevalent combinations were those that met a threshold of having ≥ 1% of patients in the combination. Each number represents the percentage where the numerator is the number of patients with the multimorbidity combination by the end of the study period, and the denominator is the total number of patients with multimorbidity by the end of the study period. The color corresponds to the demographic group. Greater shading intensity corresponds to larger percentages for demographic groups. b Heatmap of prevalent multimorbidity combinations by patient demographic characteristics, ADVANCE data 2019. Abbreviations: HLP = hyperlipidemia; HTN = hypertension; DM = diabetes; CKD = chronic kidney disease; DEP = depression; ANX = anxiety; ARTH = arthritis. Notes: The most prevalent combinations were those that met a threshold of having ≥ 1% of patients in the combination. Each number represents the percentage where the numerator is the number of patients with the multimorbidity combination by the end of the study period, and the denominator is the total number of patients with multimorbidity by the end of the study period. The color corresponds to the demographic group. Greater shading intensity corresponds to larger column percentages for demographic groups

Discussion

This study adds to our understanding of the challenges facing CHCs with large proportions of their patient panels contending with multimorbidity, including patterns characterized by somatic, mental health conditions, and increasingly complex patterns of multimorbidity with greater numbers of morbidities. We found that the most prevalent combinations across study years were, in order, hypertension-hyperlipidemia, followed by hypertension-hyperlipidemia-diabetes and hypertension-diabetes. Notably, the multimorbidity pattern of CKD-diabetes-hyperlipidemia-hypertension increased in rank from 6 to 4th for the last 4 years of observation. Also, four of the 11 most prevalent multimorbidity combination patterns included a mental health condition, suggesting high mental health morbidity in this safety-net clinical population. The changing prevalent multimorbidity combination patterns seen across the study years suggest rising prominence of mental health morbidity and advanced cardiometabolic disease among vulnerable CHC patients. This may be due to both the aging of existing CHC patient panels and changes to the composition of CHC patients over the study years.

Our findings are largely aligned with the limited number of studies focusing on multimorbidity in safety-net health-care settings. One such study assessed how common multimorbidity is in CHC settings and assessed the prevalence of individual chronic diseases using national data on ambulatory care settings at one point in time23. The study found CHCs provide a high volume of care for patients with multimorbidity and treat high rates of chronic diseases that disproportionately affect low-income communities, such as diabetes and hypertension23. Our findings add to this literature by highlighting several points. Older adults had a higher prevalence of somatic multimorbidity combinations, and middle-aged patients had similar proportions of somatic multimorbidity combinations and greater proportions of mental multimorbidity combinations, suggesting that CHC patients experience a high burden of disease earlier in adulthood. Specific disease combinations with increasing prominence among CHC patient panels (CKD-diabetes-hyperlipidemia-hypertension and anxiety-depression) suggest a need to improve screening and treatment for mental health disorders, as well as strengthening secondary prevention efforts to avert progression of metabolic morbidity to renal involvement. Providing adequate resources for community health centers to target secondary complications of cardiometabolic conditions might be indicated: nutritionists, podiatry and footwear resources, ophthalmologists, more readily available nephrology consultation, pharmacists, and home services to improve blood sugar and pressure monitoring.

Understanding patterns of multimorbidity in vulnerable populations—such as those reported in this study—provides valuable insights into formulating clinically responsive care plans matched to the needs of these patient panels. For instance, practices are increasingly seeing patients with complex multimorbidity and should adopt continuity of care policies to ease high treatment burdens involved in self-managing multiple conditions, attending various medical appointments, and managing complex drug regimens.24 In addition, safety-net institutions may need to move toward providing greater levels of geriatric care—even while serving patient panels with aggregate average ages that may be considered “pregeriatric”—as this care aligns with the broad chronic disease needs of their patients. Conducting assessments and identification of geriatric syndromes and integrating effective geriatric care models into safety-net systems may be necessary next steps in providing responsive care in light of the multimorbidity burden observed in these clinical settings.25.

This study draws from a number of strengths. First, the ADVANCE community health center network provides a comprehensive, ongoing, and robust multi-state clinical dataset across various geographic regions in the USA, representing a large safety-net clinical population. Second, this study contributes to the emerging literature on multimorbidity by assessing the most prevalent patterns among vulnerable adults in the USA over a 6-year period—including housing insecure, agricultural workers, low-income, uninsured, and underinsured groups. Our study contributes to this evolving literature by identifying prevalent multimorbidity patterns for an understudied safety-net clinical population and assessing changes to prevalent patterns over time.

This study also has several limitations. First, we note that there is no consensus on how to measure and operationalize multimorbidity and these choices greatly affect prevalence estimates.26 We opted to apply the framework endorsed by the US Department of Health and Human Services Multimorbidity Framework that centers around chronic diseases relevant to aging populations,20,21 but future studies should examine how consideration of additional chronic conditions and sensory impairments affects multimorbidity prevalence estimates for safety-net populations.26 Second, this analysis is contingent on access to clinical services and does not assess the CHC patient population who did not have any clinical visits during this study time period. Our results may underestimate the prevalence of multimorbidity as some chronic conditions may be undiagnosed,27 especially among CHC patients who experience long interruptions and obstacles to their health-care access,14 although recent studies have shown good continuity of care and engagement in similar CHC patient samples.28,29 Third, we relied on problem lists for chronic disease ascertainment in electronic health record data. While problem list completeness is quite heterogeneous across clinical practices and health-care systems, we found problem lists were adequately complete, and problem list–ascertained diagnoses were highly concordant with encounter-ascertained diagnoses in our CHC data (analyses available upon request). Finally, patients may seek care outside CHCs and thus may not be captured in our analyses; however, evidence suggests that most established CHC patients, especially those diagnosed with chronic diseases, continue to seek and receive care from CHCs.29.

Demographic cohorts over the next decade are entering into older age with greater multimorbidity burdens than prior birth cohorts30 and will put further strains on the health-care systems, particularly those in the safety net. This study addresses gaps in our understanding of the multiple clinical needs of the safety-net population and needs to mobilize primary and secondary preventive care to avert cascading increases in clinical complexity and health-care expenditures. Whether it triggers referrals to social services and supports within and external to clinics,31 a better understanding of the specific chronic disease needs of patient panels—such as the complex cardiometabolic, renal, and mental health chronic disease needs observed in this study—will guide safety-net health systems in organizing and delivering care that is attentive to the psychosocial and physical health burden.7,32,33 Identification of multimorbidity patterns that frequently occur in CHC settings provides insight into the clinical complexity patients and clinicians face and will inform programs that treat current problems, increase uptake of preventive services to avert new diagnoses, and promote behavioral health support that may avoid complications and exacerbations of existing illness.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Author contribution

ARQ contributed to the literature search, study design, data interpretation, and drafting of the manuscript. SHV contributed to the data management, data analysis, data interpretation, and writing and editing of the manuscript. NH and JH contributed to the data interpretation and writing and editing of the manuscript. MU, MM, JL, JO, TS, RV, KP, and NW contributed to the data interpretation and editing of the manuscript. All of the authors approved the final version of the manuscript. ARQ and SHV had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Funding

This work was conducted with the Accelerating Data Value Across a National Community Health Center Network (ADVANCE) Clinical Research Network (CRN). OCHIN leads the ADVANCE network in partnership with Health Choice Network, Fenway Health, and Oregon Health & Science University. ADVANCE is funded through the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI), contract number RI-CRN-2020–001. This study was supported by the National Institute on Aging of the National Institutes of Health award (R01AG061386 to ARQ). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Declarations

Conflict of Interest

All authors declare they have no conflicts of interest to report.

Footnotes

Prior presentations

A preliminary version of these analyses was presented at the North American Primary Care Research Group Annual Meeting held virtually in November 2020.

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Marengoni A, Angleman S, Melis R, et al. Aging with multimorbidity: a systematic review of the literature. Ageing Res Rev. 2011;10(4):430–439. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2011.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jacob ME, Ni P, Driver J, et al. Burden and Patterns of Multimorbidity: Impact on Disablement in Older Adults. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2020;99(5):359–365. doi: 10.1097/PHM.0000000000001388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Salive ME. Multimorbidity in older adults. Epidemiol Rev. 2013;35:75–83. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxs009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lochner KA, Cox CS. Prevalence of Multiple Chronic Conditions Among Medicare Beneficiaries, United States, 2010. Prev Chronic Dis. 2013;10. 10.5888/pcd10.120137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.McPhail SM. Multimorbidity in chronic disease: impact on health care resources and costs. Risk Manag Healthc Policy. 2016;9:143–156. doi: 10.2147/RMHP.S97248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ward BW, Schiller JS. Prevalence of multiple chronic conditions among US adults: estimates from the National Health Interview Survey, 2010. Prev Chronic Dis. 2013;10(120203). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Boyd CM, Fortin M. Future of Multimorbidity Research: How Should Understanding of Multimorbidity Inform Health System Design? Public Health Rev. 2010;32(2):451. doi: 10.1007/BF03391611. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.National Association of Community Health Centers. Chartbook-Final-2021.Pdf.; 2021. Accessed June 16, 2021. https://www.nachc.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/Chartbook-Final-2021.pdf

- 9.Shin P, Alvarez C, Sharac J, et al. A Profile of Community Health Center Patients: Implications for Policy. Geiger GibsonRCHN Community Health Found Res Collab. Published online December 1, 2013. https://hsrc.himmelfarb.gwu.edu/sphhs_policy_ggrchn/43

- 10.Hicks LS, O’Malley AJ, Lieu TA, et al. The Quality Of Chronic Disease Care In U.S. Community Health Centers. Health Aff (Millwood). 2006;25(6):1712–1723. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.25.6.1712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shadmi E. Disparities in multiple chronic conditions within populations. J Comorbidity. Published online 2013:45–50. 10.15256/joc.2013.3.24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Keogh C, O’Brien KK, Hoban A, O’Carroll A, Fahey T. Health and use of health services of people who are homeless and at risk of homelessness who receive free primary health care in Dublin. BMC Health Serv Res. 2015;15:58. doi: 10.1186/s12913-015-0716-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nguyen OK, Makam AN, Halm EA. National Use of Safety-Net Clinics for Primary Care among Adults with Non-Medicaid Insurance in the United States. PLOS ONE. 2016;11(3):e0151610. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0151610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huguet N, Angier H, Hoopes MJ, et al. Prevalence of Pre-existing Conditions Among Community Health Center Patients Before and After the Affordable Care Act. J Am Board Fam Med JABFM. 2019;32(6):883–889. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2019.06.190087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barnett K, Mercer SW, Norbury M, Watt G, Wyke S, Guthrie B. Epidemiology of multimorbidity and implications for health care, research, and medical education: a cross-sectional study. The Lancet. 2012;380(9836):37–43. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60240-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vogeli C, Shields AE, Lee TA, et al. Multiple chronic conditions: prevalence, health consequences, and implications for quality, care management, and costs. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(Suppl 3):391–395. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0322-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.DeVoe JE, Gold R, Cottrell E, et al. The ADVANCE network: accelerating data value across a national community health center network. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2014;21(4):591–595. doi: 10.1136/amiajnl-2014-002744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hoopes M, Schmidt T, Huguet N, et al. Identifying and characterizing cancer survivors in the US primary care safety net. Cancer. 2019;125(19):3448–3456. doi: 10.1002/cncr.32295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Darney BG, Jacob RL, Hoopes M, et al. Evaluation of Medicaid Expansion Under the Affordable Care Act and Contraceptive Care in US Community Health Centers. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(6):e206874–e206874. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.6874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goodman RA, Posner S, Huang ES, Parekh AK, Koh HK. Defining and measuring chronic conditions: imperatives for research, policy, program, and practice. Prev Chronic Dis. 2013;10:E66. doi: 10.5888/pcd10.120239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.US Department of Health and Human Services. Multiple Chronic Conditions: A Strategic Framework Optimum Health and Quality of Life for Individuals with Multiple Chronic Conditions. Published online December 2010. 10.1037/e507192011-001

- 22.Wright A, McCoy AB, Hickman TT-T, et al. Problem list completeness in electronic health records: A multi-site study and assessment of success factors. Int J Med Inf. 2015;84(10):784–790. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2015.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Corallo B, Proser M, Nocon R. Comparing Rates of Multiple Chronic Conditions at Primary Care and Mental Health Visits to Community Health Centers Versus Private Practice Providers. J Ambulatory Care Manage. 2020;43(2):136–147. doi: 10.1097/JAC.0000000000000324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wallace E, Salisbury C, Guthrie B, Lewis C, Fahey T, Smith SM. Managing patients with multimorbidity in primary care. BMJ. 2015;350:h176. doi: 10.1136/bmj.h176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chodos AH, Cassel CK, Ritchie CS. Can the Safety Net be Age-Friendly? How to Address Its Important Role in Caring for Older Adults with Geriatric Conditions. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35(11):3338–3341. doi: 10.1007/s11606-020-06010-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Griffith LE, Gilsing A, Mangin D, et al. Multimorbidity Frameworks Impact Prevalence and Relationships with Patient-Important Outcomes. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2019;67(8):1632–1640. doi: 10.1111/jgs.15921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Huguet N, Larson A, Angier H, et al. Rates of undiagnosed hypertension and diagnosed hypertension without anti-hypertensive medication following the Affordable Care Act. Am J Hypertens. Published online April 30, 2021:hpab069. 10.1093/ajh/hpab069 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28.Huguet N, Valenzuela S, Marino M, et al. Following Uninsured Patients Through Medicaid Expansion: Ambulatory Care Use and Diagnosed Conditions. Ann Fam Med. 2019;17(4):336–344. doi: 10.1370/afm.2385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Huguet N, Kaufmann J, O’Malley J, et al. Using Electronic Health Records in Longitudinal Studies: Estimating Patient Attrition. Med Care. 2020;58:S46. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000001298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Canizares M, Hogg-Johnson S, Gignac MAM, Glazier RH, Badley EM. Increasing Trajectories of Multimorbidity Over Time: Birth Cohort Differences and the Role of Changes in Obesity and Income. J Gerontol Ser B. 10.1093/geronb/gbx004 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31.DeVoe JE, Bazemore AW, Cottrell EK, et al. Perspectives in Primary Care: A Conceptual Framework and Path for Integrating Social Determinants of Health Into Primary Care Practice. Ann Fam Med. 2016;14(2):104–108. doi: 10.1370/afm.1903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Garg A, Jack B, Zuckerman B. Addressing the Social Determinants of Health Within the Patient-Centered Medical Home: Lessons From Pediatrics. JAMA. 2013;309(19):2001–2002. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.1471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Klein MD, Alcamo AM, Beck AF, et al. Can a video curriculum on the social determinants of health affect residents’ practice and families’ perceptions of care? Acad Pediatr. 2014;14(2):159–166. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2013.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.