Abstract

Objective

This systematic review explored the effectiveness of internet-delivered interventions in improving psychological outcomes of informal caregivers for neurodegenerative-disorder (ND) patients.

Methods

We searched seven databases for English-language papers published from 1999 to May 2021. Study-eligibility required that interventions used a minimum 50% internet-facilitation, targeting unpaid, adult informal caregivers of community-based ND-patients. We included randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and pre-post evaluative studies reporting outcomes for at least one-time point post-intervention. Independent quality checks on abstract and full-text screening were completed. Data extraction encompassed interventions’ features, approaches, theoretical bases and delivery-modes. The Integrated quality Criteria for the Review Of Multiple Study designs (ICROMS) framework assessed risk of bias. Alongside narrative synthesis, we calculated meta-analyses on post-intervention using outcome measures from at least two RCTs to assess effectiveness.

Results

Searches yielded 51 eligible studies with 3180 participants. In 48 studies, caregivers supported a dementia-diagnosed individual. Intervention-durations encompassed four weeks to 12 months, with usage-frequency either prescribed or participant-determined. The most frequently-used approach was education, followed by social support. We calculated meta-analyses using data from 16 RCTs. Internet-delivered interventions were superior in improving mastery (g = 1.17 [95% CI; 0.1 to 2.24], p = 0.03) and reducing anxiety (g = -1.29 [95% CI; −1.56 to −1.01], p < 0.01), compared to all controls. Findings were equivocal for caregivers’ quality of life, burden and other outcomes. High heterogeneity reflected the multifarious combinations of approaches and delivery-modes, precluding assessment of the most efficacious intervention features. Analyses using burden and self-efficacy outcomes’ follow-up data were also non-significant compared to all comparator-types. Although 32 studies met the ICROMS threshold scores, we rated most studies’ evidence quality as ‘very-low’.

Conclusions

This review demonstrated some evidence for the efficacy of internet-delivered interventions targeting informal ND-caregivers. However, more rigorous studies, with longer follow-ups across outcomes and involving NDs other than dementia, are imperative to enhance the knowledge-base.

Keywords: digital, general, internet, general, informal caregivers, neurodegenerative disorders, dementia, disease, Alzheimer disease, online, general, web-based, systematic review, carer

Introduction

Neurodegenerative disorders (ND) present an increasing health exigency worldwide1 being the foremost cause of increases in disability and second highest cause of death.2 Furthermore, the prevalence rate of the more common NDs such as Alzheimer's disease (AD) and Parkinson's disease (PD) is predicted to double in the next 20 years.1 Rarer NDs such as Huntington disease's (HD),3 amyotrophic lateral sclerosis,4 or multiple sclerosis (MS)5 have a devastating impact on patient and carer health and quality of life.

These NDs are relentlessly progressive with no known cure. Patients typically experience a complex, variable and unpredictable course of disease6 over years and often decades. Changes in behavioural, cognitive and motor skills7 affect instrumental (e.g. managing money, transportation, etc.) and basic activities of daily living (e.g. feeding, dressing and washing)8–10 escalating caregiver burden.11,12 ND care-provision is distinctly demanding13 and is associated with sleep impairment,14 anxiety,15,16 stress,17 depression,18,19 cognitive decline20 increased heart-disease risk21 and exacerbation of pre-existing conditions.22

Caregivers risk experiencing burnout. Where care-provision becomes both nonviable and deleterious23 the decision to institutionalise care-recipients is inexorable.24 To address this, different caregiver interventions such as psychoeducation,25 counselling,26 cognitive behavioral therapy27 and support groups28 are promising, but their effects vary. These studies are affected by low engagement and high attrition rates29 often due to the complexity, time demands and intensity of care-provision.30

Internet-facilitated interventions have improved access through being flexible and cost-effective.31 This is further enhanced by the recent proliferation in smartphone ownership, concomitant with availability of mobile applications.32–34 Traditionally face-to-face interventions successfully transferred online include videoconferencing-based clinical visits35 particularly during the recent Covid-19 pandemic-enforced lockdowns,36 web-based support groups37 and psychosocial interventions for caregiving dyads.38 Caregivers are also able to access support networks through social media platforms39,40 whilst connecting with caregiver-peers.37

Most reviews of caregiver interventions focus on dementia patients.41 These reviews highlight the plurality of intervention characteristics and features,42–43 psychological constructs targeted44 and delivery modalities employed. Although there is some agreement that multicomponent interventions (e.g. psychoeducation with CBT) are more effective in improving caregiver outcomes,42,45 consensus around efficacious components46 or underlying mechanisms47 remains elusive. Additionally, there appears to be an absence of literature on internet-based interventions in less common NDs, such as PD,22 amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) and rare NDs, for example, HD.48

This review investigated the efficacy of internet-facilitated interventions are at improving well-being and other health outcomes for informal caregivers of community-based, ND-diagnosed individuals. Four specific questions were addressed: (1) What therapeutic approaches and theoretical bases are most frequently used in interventions? (2) Which features are common within internet-facilitated interventions’ content and design? (3) How effective are interventions in promoting informal caregivers’ psychological health when compared to standard care alone or other active comparators (e.g. face-to-face)? (4) Which intervention approach and design feature (e.g. group vs. individual) is most efficacious?

Methods

This study was prospectively registered on Prospero before searches started49 and was conducted in accordance with the latest PRISMA guidelines.50 A completed checklist can be found in Appendix 1.

Search strategy and data sources

We searched the following databases, from 1999 until May 2021, for published studies written in English: MEDLINE and MEDLINE in-process (via Ovid); PsycINFO (via Ovid), NIH Clinical Trials; Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL); Web of Science and PubMed. Following establishment of a provisional list of studies, their citation indexes were checked for any similar studies not captured by the initial search,51 alongside hand-searching the reference lists of other reviews covering analogous intervention-types (e.g. internet-facilitated interventions for unpaid caregivers of patients with similar conditions).

A search strategy using key search terms compiled through a combination of the study authors’ (AH, JS) expertise and consultation of the extant literature was formulated. Terms were devised using the Population (e.g. caregiv*/neurodegener*/informal); Intervention (iPhone/digital/technology); Comparison intervention and Outcome measures (PICO) framework,52 concentrating on population and intervention terms, to ensure a highly sensitive search. Searches were executed using a mixture of entered keywords and existing Medical Subject Heading terms (MeSH), which were ‘exploded’ to encompass related terms. Truncation conventions, common abbreviations and Boolean operators were utilised where appropriate in order to optimise the search's sensitivity. For each database, the search strategy was customised. A complete list of search terms for each database are detailed in Appendix 2.

Study eligibility criteria and selection

Studies included adult individuals (18 years-old + ) who provide unpaid care to another community-based person with a neurodegenerative disease (ND) diagnosis. These included AD and related Dementias (e.g. frontotemporal dementia; dementia with Lewy bodies), MS, PD, motor neuron disease (e.g. amyotrophic lateral sclerosis) and HD for the latter this encompassed care-recipients with either a family history of or a positive genetic test for HD. In caregiver-recipient dyad studies, the reporting of outcome-measures exclusively derived from caregivers were required. We excluded studies involving formal, professional or paid caregivers, alongside institutionalised care-provision. Eligible caregiver-targeted interventions involved at least 50% delivery via an internet-facilitated device (e.g. smartphone, desktop computer). Any interventions that employed non-internet facilitated storage-media (e.g. CD-ROM, DVD's) only alongside those that were solely focused on practical skills training (e.g. lifting, bathing) were excluded. Where studies utilised a comparator, it was categorised as either: 1) Inactive: Wait-list/usual care/no treatment/non-active technological comparison (e.g. read-only information delivered via storage media); or 2) Active: non-technological active comparison (e.g. face-to-face delivered therapy or carer support group).

After downloading search results from all databases into an EndNote Online library, duplicates were removed using both the ‘deduplication’ function and manual identification. NB implemented initial screening of all titles and abstracts. For studies deemed either apposite or requiring further information, NB administered full-text screening. These stages were carried out independently by HBM, who screened at least 20% of the titles and abstracts, and full-text studies, in parallel. Disagreements between screenings were resolved through team discussion.

For inclusion in this review, studies needed to be quantitative studies reporting data from validated outcome measures capturing changes in psychological health variables (e.g. burden, perceived quality of life (PQoL) or health-related quality of life (HRQoL)). We included both controlled and non-controlled before-after studies (e.g. a single intervention group to test feasibility) in addition to randomized controlled trials. Correspondingly, this excluded protocol or other descriptive studies that did not provide outcome data. For estimating effect measures, only data reported by RCT's were considered in evaluating intervention effectiveness.

Data extraction

Relevant information from eligible full-text papers was recorded on data extraction forms, designed through adaptation of the Cochrane Handbook of Systematic Reviews52 guidelines to the specific objectives of this study (blank example in Appendix 4). Data extracted included; study setting, sample size in each arm, study participants’ characteristics and patient's ND diagnosis. We recorded intervention features such as; intervention's duration, delivery intensity (e.g. weekly) and features (e.g. videoconferencing), group versus individual participation and features of comparator conditions. Alongside the outcome measures used, post-intervention group means and standard deviations were extracted, with post-intervention and any follow-up data recorded separately.

In order to address review questions regarding the most frequently employed approaches, Chi & Demiris’54 classification system to categorise interventions was incorporated as follows:

Education (e.g. educational websites or videos); 2) Consultation; 3) Social support (e.g. peer group meetings); 4) Psychosocial/cognitive behavioural therapy (remotely delivered therapy, coaching); 5) Data collection and monitoring systems (e.g. experience sampling method (ESM)); and 6) Clinical care delivery (e.g. therapy delivered to caregiver & patient over videoconferencing).

To investigate the theoretical bases used in intervention design and implementation, we administered elements of Michie & Prestwich's55 theory coding scheme (TCS), applying the eleven items that identify how theory and predictors or constructs are assimilated into interventions’ framework. Items 1–6 are applicable where interventions studies either mention theories or predictors, base selection of participants on them, or use them to select, develop or tailor techniques. Items 7–11 concern the linking of intervention-techniques to theory, constructs or predictors. Items 12–19 were not utilised, as these were focused on construct measurement, mediation effects and whether outcomes led to theory alteration. Because our analysis was for classification purposes only, we opted not to employ their scoring system.

To investigate the modes of delivery used in intervention design and implementation, Webb et al.'s56 coding convention was applied in which one or more of the following categories could be assigned:

Automated functions. i) providing an enriched environment (e.g. access to content and other links); ii) providing tailored feedback based on monitoring (reinforcement messaging); iii) follow-up messaging (e.g. reminders, encouragement)

Communicative functions. i) scheduled contact with an advisor (e.g. emails); ii) access to an advisor to receive advice (e.g. ‘chat sessions, “ask the Expert” facility); iii) peer-to-peer (e.g. peer-to-peer discussions, live-chat). Furthermore, the details recorded about the advisor were study-specific descriptions of their role (e.g. moderator), alongside any prerequisite qualifications or training given.

Supplementary modes. such as i) email; ii) phone; iii) SMS; or iv) videoconferencing.

Data analysis

To resolve questions 1 & 2, relevant data on intervention features was grouped together and synthesised using a narrative approach. For question 3, quantitative synthesis using group means and standard deviations were extracted. If this data were not available, study authors were contacted. If required data could not be obtained, that measurement was excluded from the calculations. For studies reporting post-intervention means at multiple time-points, the first post-intervention time-point (e.g. at the conclusion of intervention exposure) was used in calculations. Any studies that reported follow-up data were pooled for separate meta-analysis per outcomes. To address question 4, we contemplated meta-regression using potential modifiers where at least ten studies reported the same outcome. Intervention approach, mode of delivery and participation type (individual vs. group participation) were identified as viable modifiers.

Meta-analysis using post-intervention measurements were conducted when outcome data were reported by at least two RCTs. We calculated the inverse variance method of Hedges g standardised mean differences (SMD) with 95% confidence intervals, using RevMan version 5.4 for effect-size pooling. The fixed effect model was reported If there were less than five studies (k < 5) in the meta-analysis, or the random-effects model for those with five studies or more (k≥5), in line with recommendations.57 Heterogeneity was assessed using the I² statistic,58 with an I² calculation of ≤25% considered low: ≤50% considered ‘moderate’; and >50% considered high.132

Risk of bias in individual studies

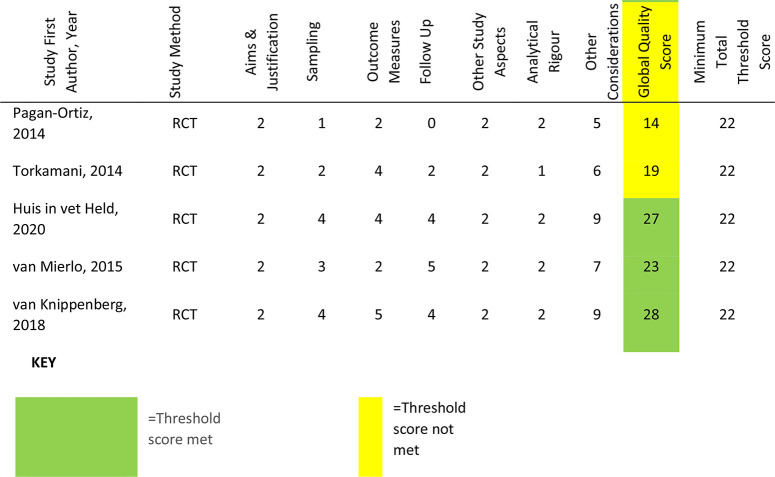

On account of the variation of study-designs, we assessed the quality of included studies using the Integrated quality Criteria for the Review of Multiple Study designs (ICROMS).59 Individual assessment items are stipulated within seven dimensions, in which items are either specified for particular study designs (e.g. 2A: allocation adequately controlled for RCT's only) or applicable to all types (e.g. 3E: outcome measures assessed blindly). Relevant items are scored (2 = criterion met; 1 = unclear; 0 = criterion not met), which are then summed to provide a ‘global quality score’ for each paper. These totals were assessed against the specified threshold scores (60% of the total available) for each study design, detailed in a ‘decision matrix’, which also stated individual ‘mandatory criteria’ items for study-types. Threshold scores are 18 out of a possible 30 for CBA's and 22 out of 36 for RCT's or NCBA's.

NB conducted an initial quality assessment. HMB conducted an independent assessment on a 20% random sample of all included studies. Both NB and HMB compared their assessments for this random sample. Any unresolved discrepancies or disagreements were settled by the review team.

Evidence quality

For studies incorporated into meta-analyses, the Grading of Recommendations, assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) framework was applied to assess the evidence quality.53 This approach uses five domains: risk of bias, inconsistency, indirectness, imprecision and publication bias to appraise evidence quality. This is reflected in one of four levels: ‘high’; ‘moderate’; ‘low’ or ‘very low’.

Results

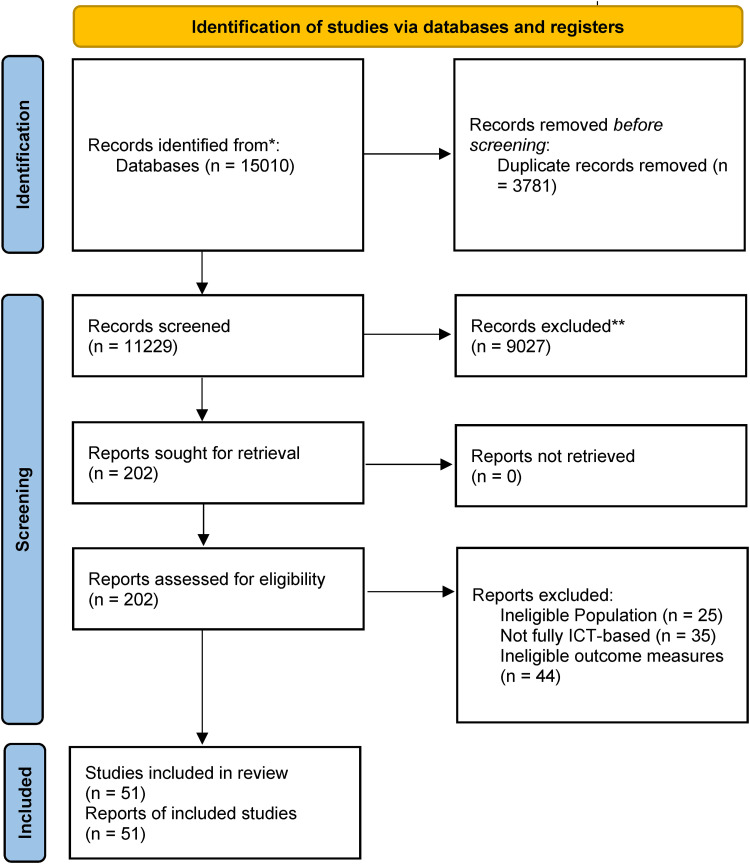

The initial search generated 15,010 results. Following deduplication and screening via abstract and title, 202 references were progressed for full-text screening by the first author (NB). Following calibration with another author's (HMB) independent screening, 51 studies (all unique study datasets) were assessed as fully meeting eligibility criteria. The full screening process is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Prisma flowchrt for the identification of studies.

Of the 151 excluded full-text studies, the 40 studies classed as ‘near-misses’ are detailed in Appendix 3, with reasons for their exclusion. The most frequent reasons for exclusion were: >50% of intervention not internet-facilitated (k = 8), non-caregiver focused intervention or measures (k = 5) and outcome criteria not met (k = 8).

Description of studies

Within the 51 eligible studies, 48 different interventions are reported; three interventions were reported in more than one study, albeit involving different study populations; ‘Tele-STAR’,83,95 ‘Caring for Others’94,95 and DEM-DISC’.97,99 The final list consisted of 26 RCTs, seven controlled before–after (CBA) studies and 18 non-controlled before after (NCBA) studies. Study-duration varied, as did whether authors reported weeks, months or years. The briefest studies lasted less than one month76,94,101; the longest was two years in length.8 Geographically, almost half the studies (k = 25) were conducted in North America and another 19 in Europe. Of the remaining studies, three were carried out in South-Asia, one in South America, one in Australia, one in India and one in Iran.

Most studies limited outcome data collection to pre- and post-intervention (k = 35), with few studies reporting outcomes mid-intervention (k = 8) or follow-up (k = 10) ranging from two weeks83 to 42 weeks.66 We identified 38 individual outcome domains quantified using 92 different outcome-measures. Depression was the most frequently measured (k = 32) using eight different scales, followed by burden (k = 26) using six different scales and mastery (k = 13) using six different scales.

An overview of study characteristics, listed by study lead author, is presented in Table 1

Table 1.

Summary of Included Studies.

| Lead Author Name (Study Ref), Country | ND | Study Duration & Design | Intervention Intensity, Frequency & Length | Individual/ Group/ Dyadic Participation | Delivery Features | Control Arm Type | Outcome measure Time-points |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Austrom (60), United States | Alzheimer's Disease (AD) | 6 month NCBA3 | Weekly support group over 6 months | Group | Web-based video support group accessed using desktop computer equipment | None | Pre & Post (intervention)

|

| Blom (61), Netherlands | Dementia | 6 month RCT1 | Eight lessons with homework followed by booster session one month after, over 6 months | Individual | Multimedia internet course & secure application used for returning caregiver-completed worksheets. All accessed via an Internet-connected computer | Information E-bulletins | Baseline, after fourth lesson, post- intervention:

|

| Boots (62), Netherlands | Dementia | 2 year RCT |

|

Individual | Multimedia tailored online thematic modules, email- delivered feedback. Peer access through online forum. No device specified. | Usual care: non-frequent counselling sessions during 8 weeks | Pre & Post- intervention: Main:

|

| Chiu (63), Canada | Dementia | 6 month NCBA | Participant determined frequency of use over 6 months | Individual | Website provides access to information handbook using internet- connected computer. Email messaging with professional | None | Pre & Post intervention:

|

| Cristancho-Lacroix (64), France | Alzheimer's Disease (AD) | 6 month RCT | Twelve thematic sessions: sequentially and weekly unblocked once the previous session entirely viewed over 3 months | Individual (psychoeducation) group (social forum) | Multimedia website provides information modules and anonymised peer access via an online forum. Accessed via Internet- connected computer | Usual care; 1xvisit to geriatrician & wait-list receive access at end of intervention | Pre & post intervention, 6-month follow-up:

|

| Czaja (65), United States | Alzheimer's Disease (AD) | 5 month RCT | Six one-hour monthly sessions; video seminars released monthly over 5 months | Individual (video seminars) Group (peer support sessions) | Video seminars & live videophone support sessions, both accessed via a CISCO IP 7900 videophone | Information: Mailed package of printed Alzheimer's caregiving content | Pre & Post;

|

| Dam (66), Netherlands | Alzheimer's Disease & Related Disorders (ADRD) | 2 year NCBA | Participant determined frequency of use over 16 weeks | Individual | Online social support platform; social networking function, caregiver- completed information with facility for peer response; multimedia information | None | Baseline, 8 weeks, 16 weeks & 42 weeks follow up:

|

| Dang (67), United States | Dementia | 12 month NCBA | Minimum of monthly contact between care co-ordinator and dyad; otherwise participant determined frequency of use; over 12 months | Dyadic | Computer- Telephone Integration System (CTIS) providing access to caregiving information, automated surveys by which caregivers were monitored, alongside facility to make & receive calls | None | Pre & Post:

|

| Duggleby (68), Canada | ADRD | 6 month RCT | Participant determined frequency of use over 3 months | Individual | Platform provides access to information & areas to enter individual information. Access via computer, tablet or mobile. | Usual care & information: Alzheimer's printed educational booklet | Pre & post, 6 month follow-up:

|

| Finkel (69), United States | ADRD | Six- month RCT |

|

Individual (psychoeducation) group (social forum) | Computer- Telephone Integration System (CTIS) providing access to caregiving information, facility to make & receive calls, send & retrieve messages, conference with several people simultaneously | Basic printed educational materials'; two check in phone-calls three & five months post-randomization | Pre & post, 6 month follow-up:

|

| Fowler (70), United States | ADRD | 12 month RCT | Weekly posting online of educational information, with a blog monitored daily by the research team over 4 months | Individual | Multimedia website providing access to caregiving information, facility to upload data from sleep actigraphy band & peer- professional support via a blog | Upload data from sleep actigraphy band only | Pre & post:

|

| Fowler-Davis (71), United kingdom | Dementia | 4 month NCBA | Participant determined frequency of use over 4 months | Individual | Digital plug installed with a 'routinely used' electrical device (e.g. kettle), monitored via mobile application | None | Pre & post:

|

| Griffiths (72), United States | Dementia | 8 week NCBA | Daily internet- delivered video modules (six per week); weekly group videoconferences over 6 weeks | Individual (psychoeducation) group (social forum) | Online video training modules delivered on iPads | None | Pre & post:

|

| Gustafson (73), United States | Dementia | 6 month RCT | Participant determined frequency of use, although researchers encouraged minimum once per week over 6 months | Individual (psychoeducation) group (social forum) | Website provides access to: online forum; professional messaging service; access to multimedia information & areas to enter individual information, accessed via computer | Information: A printed book for family caregivers of dementia patients | Pre & post:

|

| Hattink (74), Pan-European | Dementia | 10 month RCT |

|

Individual (psychoeducation) group (social forum) | Platform for interactive e learning and Facebook & LinkedIn-enabled peer-peer/professional communication. No device specified | Waitlist; receive access to intervention following post-test measurements | Pre & post

|

| Hicken (75), United States | Dementia | 4–6 month CBA2 | Intervention content accessed 3 days per week for approximately 10-15 minutes over 4–6 months | Individual | Internet-provided multimedia information modules; caregiver health & wellbeing assessments, remotely monitored. Accessed via computer | Telephone calls | Pre & post:

|

| Kajiyama (76), United States | ADRD | RCT | Participant determined frequency of use; no time limit specified for module completion | Individual | Multimedia e-training program with an emphasis on skills training. Accessed on 'any type of computer'. | Information: Multimedia dementia-information website, without training component | Pre & post:

|

| Kajiyama (77), United States | Alzheimer's Disease (AD) | 4 week NCBA | Recommended one episode per week: but not monitored; self-paced over 4 weeks | Individual | Online Spanish-language telenovela | None | Pre & post:

|

| Kales (78), United States | Dementia | 2 month RCT | Participant determined frequency of use over 1 month | Individual | Website provides an algorithm-generated 'prescription' using information entered, caregiving information & a daily messaging feature. Accessed via iPad | Waitlist; receive intervention access one month from baseline assessment | Pre & post:

|

| Khazaeili (79), Iran | Multiple Sclerosis (MS) | 6 month RCT | 8 weekly two-hour sessions over 8 weeks | Group | Webinar; educational & audio content delivered via the Telegram application | No exposure | Pre & post, one month follow up:

|

| Kwok (80), Hong Kong | Dementia | 9 week NCBA | 8 weekly sessions with completion of online worksheets, alongside direct messaging to the counsellor

|

Individual | A website with multimedia information; counselling component delivered using online messaging | None | Pre & Post Chinese versions of:

|

| Lai (81), Hong Kong | Dementia | 7 week RCT | Seven weekly training workshops over 7 weeks ' | Group | Website provides access to online group forum | Face-to-face delivery | Pre & post:

|

| Laver (82), Australia | Dementia | 4 month RCT | 8 consultations lasting approximately 60 minutes over 16 weeks | Dyadic | Videoconferencing software accessed via laptop, tablet or smartphone | Face-to-face delivery | Pre & post:

|

| Lindauer (83), United States | Alzheimer's Disease (AD) | 4 month NCBA | 8 weekly sessions over 8 weeks | Individual | Online video- conferencing, via computer, laptop or smartphone. Caregiver's also write notes in a workbook to be shown to the screen | None | Pre, halfway, post & 2 month follow up:

|

| Marziali (84), Canada | Dementia | 6 month RCT | A 1-hour group therapist- facilitated video-conferencing weekly for 10 weeks. Subsequently, 12 weekly video-conferencing sessions facilitated by group member over 22 weeks | Group | A password-protected Web site with links to (a) disease-specific information, (b) private e-mail, (c) a question-and-answer forum, and (d) a videoconferencing link | No exposure | Pre & post:

|

| Marziali (85), Canada | Dementia | 6 month CBA | Weekly log on for 1 hour over 20 weeks | Group | Password-protected Web site with link to video-conferencing and online dementia handbook | Online text-based chat group and educational dementia care videos | Pre & post:

|

| McKechnie (86), United Kingdom | Dementia | 12 week CBA | Participant determined frequency of use over 12 weeks | Individual | Online forum | None | Pre & post:

|

| Meichsner (87), Germany | Dementia | 2 year RCT | One therapist message and one participant reply weekly. Follow-up messages for non-response after two days over 8 weeks/ | Individual | Online messaging using a secure internet platform | Waitlist; receive intervention post follow-up assessment | Pre & post, follow-up (5 months post-baseline):

|

| Metcalfe (88), Pan-European | Young-onset Alzheimer's Disease (AD) or Frontotemporal degeneration (FTD) | 12- week RCT | Programme available online 24 hours a day. Usage determined by participant over 6 weeks | Individual | Web-based multimedia information | Waitlist; access given after 6 weeks | Pre & post:

|

| Nunez-Naveira (89), Pan-European | Dementia | 3 month RCT | Participant determined frequency of use over 3 months | Individual | Online application providing multimedia information, questionnaires for caregivers to complete for personalization and a social network. Accessed via computer, smartphone or tablet | No exposure | Pre & post:

|

| O’Connor (90), United States | Dementia | 8 week NCBA | Each group convened weekly for one hour over 8 weeks | Group | Platform providing virtual reality and avatar section. Communication text-only. Accessed via computer | None | Pre & post:

|

| Pagan-Ortiz (91), United States | Dementia | 1 month RCT | 4 sessions of approximately 1–1.5 hours over 1 month | Individual | Website providing access to multimedia information, comment section for professional & peer-interaction | Printed educational materials on Alzheimer's caregiving | Pre & post:

|

| Park (92), South Korea | Dementia | 3 month CBA | Frequency of use encouraged minimum once per week, although participant determined over 4 weeks | Individual | Information content delivered via mobile application | Information: Printed handbook version of the application's contents | Pre & post, 2 week follow up:

|

| Schaller (93), Germany | Dementia | 18 week NCBA | Minimum once-a-week usage over 12 weeks | Individual | Application provides access to information modules; self-completion unmonitored information tools; professional access via messaging tool | None | Pre & post:

|

| Sikder (94), United States | ADRD | 4 week NCBA | Participant determined frequency of use, although recommended to listen to audio sessions twice a day for the first week and daily thereafter over 4 weeks | Individual | Mobile application providing access to audio sessions and written content | None | Pre & post, including weekly in-app measures:

|

| Thomas (95), United States | Dementia | 12–18mth NCBA | E-AD: Caregiver completed weekly online surveys over 12–18mths: T-STAR; eight sessions, timeframe not reported | Individual | E-AD: the ORCTECH home-based computing system with data collection from installed sensors wirelessly connected to a monitor less PC T-Star: videoconferencing link | None | Pre & post; E-AD

|

| Torkamani (96), Pan-European | Dementia | Six- month RCT | Participant determined frequency of use over 6 months | Individual (psychoeducation) group (social forum) | Platform provides access: multimedia information, peer access via online forum, participant- entered information monitored by clinicians; direct messaging to professionals. Access via laptop | No exposure | Pre, 3 month, post:

|

| van der Roest (97), Netherlands | Dementia | 6 month CBA | Participant determined frequency of use over 2 months | Individual | Web-based interactive search-engine based social chart providing general, local & tailored information. Accessed via computer | No exposure | Pre & post.:

|

| van Knippenberg (98), Netherlands | ADRD | 4 month RCT | ESM self-monitoring at random times for 3 days per week & received standardized ESM-derived feedback on personalized patterns of positive affect every 2 weeks during a face-to-face session with a coach. over 6 weeks | Individual | ESM: Participants responded to palmtop-generated alerts to complete questionnaires, also completed on the palmtop. Face-to-face feedback following two weeks of monitoring | Pseudo intervention: ESM monitoring without feedback Control: usual care of low-frequent counselling sessions | Pre & Post:

|

| van Mierlo (99), Netherlands | Dementia | 12 month RCT | Participant determined frequency of use over 12 month s | Individual | Web-based interactive search-engine based social chart providing information based on information entered, links to relevant organizations,; content posted by participants monitored by professionals | No exposure; received advice from case managers who also did not have access | Pre & post:

|

| huis in het Veld (100), Netherlands | Dementia | 12 week RCT | Family caregivers received 3 personal email contacts with a specialist dementia nurse. Were also sent links to six online videos and six e-bulletins, over 12 weeks | Individual | Professional contact, video links and e-bulletins all sent via email | Medium intervention: online videos & e-bulletins Control: information e-bulletins only | Baseline/6 weeks/12 weeks:

|

| Wijma (101), Netherlands | Dementia | 4 week NCBA | 13 minute VR simulation experienced at a local healthcare organisation, then 3×20 min e-courses completed at home within three weeks; total of four weeks | Individual | Virtual reality (VR) movie accessed through a VR-device and e-course for which no device stipulated | None | Baseline/6 weeks/12 weeks

|

| Wilkerson (102), United States | Alzheimer's Disease (AD) | 3 month CBA | Participant determined frequency of use, weekly participation encouraged over 6 weeks | Group | Web-based application to join a Facebook social network. Separate email reminders | Online interaction with researchers only | Pre & post:

|

| Zimmerman (103), United States | ADRD | 6 month CBA | Participant determined frequency of use over 6 months | Individual | Website providing multimedia information, separate reminders sent by email | A printed book with the same, but more concise, content | Pre, 3 months, post

|

| Moskowitz (104), United States | Dementia | 12 month RCT | Weekly sessions over 6 weeks | Individual | Live online webinar accessed via tablet | Waitlist; completed assessments during waiting time. Access after 6 weeks | Pre, three months, post:

|

| Baruah (105), India | Dementia | 3 month RCT | Participant determined frequency of use, although encouraged to complete at least five lessons, over 3 months | Individual | Multimedia e-learning, where caregivers complete exercises, for which they received instant feedback | Information: Education only e-book based on an Alzheimer's Disease International/WHO brochure | Pre & post:

|

| De Wit (106), Netherlands | Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis | 6 month RCT | 6×1.5hrs modules could be completed within 1–2 weeks, over 3 months | Individual | Fixed sequence of online modules where caregivers complete exercises, for which they received feedback. Peer contact through private messaging and a forum | Usual Care | Pre, post, 6 months

|

| Brunisma (107), Netherlands | Young-onset Alzheimer's Disease (AD) | NCBA | Caregivers follow each module whilst choosing 4 thematic modules, over 8–10 weeks (this is flexible) | Individual | Multimedia tailored online thematic modules, email- delivered feedback. Peer access through online forum. No device specified. | None | Pre, post

|

| Halstead (108), USA | Multiple Sclerosis | 3 month NCBA | 6×45 minute weekly sessions, over six weeks | First & last modules: dyadic, Remaining four: individual | Secure, web-based portal MS Hub, through which caregivers accessed related program software e.g. videoconferencing | None | Pre, post, 3 months

|

| Han (109), USA | Dementia | 3 month NCBA | Weekly one-hour sessions over 3 months | Individual | Sessions delivered via Zoom video-conferencing using a computer or smartphone | None | Pre, post,

|

| Romero-Mas (110), Spain | Alzheimer's Disease (AD) | 10 month NCBA | Participant determined frequency of use over 10 months | Group | All content and activities accessed using a mobile application | None | Pre, post

|

Randomised Controlled Trial (RCT)1; Controlled Before-After (CBA)2; Non controlled-Before-After (NCBA)3; Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9)4; General Anxiety Disorder (GAD-7)5; Short Form-36 (SF-36)6; Caregiver Burden Scale (CBS)7; Revised Caregiver Self-Efficacy Scale (RCSES)8; Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression scale (CES-D)9; Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS-A)10; Revised Memory and Behavior Problems Checklist (RMPBC)11; Short Sense of Competence Questionnaire (SSCQ)12; Caregiver Self-Efficacy Scale (CSES)13; Pearlin Mastery Scale(PMS)14; Investigation Choice Experiments for the Preferences of Older People (ICECAP-O)15; Burden Scale for Family Caregivers (BSFC)16; Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS)17; Positive Aspects of Caregiver (PAC)18; Caregiver Competence Scale (CCS)19; Perceived Stress Scale (PSS-14)20; Zarit Burden Interview (ZBI)21; Beck Depression Inventory (BDI)22; Nottingham Health Profile (NHP)23; Social Support List (SSL)24; Loneliness Scale (LS)25; Brief Cope (COPE)26; Short Form-12 item [version 2] health survey27; General Self-Efficacy Scale (GSES)28; Herth Hope Index (HHI)29; Health & Social Services Utilization (HSSUI)30; Received Social Support scale (RSS)31; State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STA-I)32; (UCLA LS)33; Approaches to Dementia Questionnaire (ADQ)34; Alzheimer's Disease Knowledge scale (ADKS)35; Interpersonal Reactivity Scale (IRS)36; Marwit-Meuser Caregiver Grief Inventory-Short Form (MARWIT)37; Desire to Institutionalize Scale (DIS)38; Perceived Quality of Life Scale (PQOL)39; Neuropsychiatric Inventory (NPI-Q)40; Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI-II)41; Caregiver Burden Inventory (CBI)42; Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire (FFMQ)43; General Health Questionnaire 30 (GHQ-30)44; Caregiver Mastery Index (CMI)45; Perceived change Scale (PCS)46; Quality of Life in Alzheimer's Disease (QOL-AD)47; Eysenck Personality Questionnaire Revised (EPQ-R)48;Health status questionnaire (HSQ-12)49; Functional Autonomy Measurement System (SMAF)50; Scale for the Quality of the Current Relationship in Caregiving (SQCRC)51; Caregiver Grief Scale (CGS)52; EuroQoL (EQ-5D-5L)53; Revised Caregiving Satisfaction Scale (RCSS)54; Geriatric Depression scale (GDS)55; Lubben Social Network Scale (LSNS)56; Quick inventory of Depressive Symptoms (QIDS)57; Positive & Negative Affect scale (PNAS)58; Functional Activities Questionnaire (FAQ)59; Quality of Life Scale (QOLS)60; Dyadic Relationship Scale (DRS)61; Utrecht Coping List (UCL)62; Trust in our Own Abilities (TOA)63; Medical Outcomes Survey (MOS)64; Caregiver Confidence in Symptom Management (CCSM)65; Global Health Scale (GHS)66; The Quality of Life in Neurological Disorders (NeuroQOL)67; Care- Related Quality of Life (CarerQoL)68; Modified Social Support Survey (MSSS)69; Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale (DASS)70; Engagement in Meaningful Activities Survey (EMAS)71; Experiential Avoidance in Caregiving Questionnaire (EACQ)72; Acceptance & Action Questionnaire II (ACQ-II)73; Cognitive Fusion Questionnaire (CFQ-7)74; (WHOQoL-BREF)75

Population characteristics

A total of 3180 informal caregivers were enrolled across all studies. For RCTs, or CBAs that incorporated comparative groups, the mean number of participants was 43 (SD = 36.72) in intervention and 41 (SD = 27.05) in control arms. In NCBAs, the mean sample size was 28 (SD = 16.99). All but five studies63,79,81,83,91 provided information on gender of participants; female caregiver participants constituted 32%108 to 100%60,90 of the sample size.

Reporting of other demographic variables such as age, ethnicity or caregiver-patient relationship varied substantially across studies. Where studies reported mean ages, this ranged from 52.9 years (SD = 11.4) to 72.1 years (SD = 8.4). For the studies that reported age ranges, the lowest reported was 20, the highest 87. Five studies completely omitted this information. In terms of caregiver's relationship to care recipient, most studies involved spouses or adult-children.

In respect of other socio-demographics (e.g. educational-attainment, monthly income), our ability to synthesize was constrained by the extent of inconsistent reporting. This was also true for other variables of interest, including pre-intervention ownership, familiarity or confidence with internet-facilitated technology. Where the latter was captured, this was principally via qualitative methods, with little quantitative assessment.

Apart from two studies79,106 detailing Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (AMS) and one study108 detailing MS, all other studies (k = 48) concerned patients whose diagnosis was either described as

Dementia, AD or Alzheimer's Disease and Related Disorders (ADRD). There were no studies involving HD or PD.

Interventions: key features and classifications

Intervention duration varied, from interventions lasting four weeks,77,92,94,101 to the longest at 12 months67,99 in length. The mode intervention duration was six months, although more than half the interventions lasted for three months or less. With reference to delivery-intensity, sessions were most frequently delivered weekly (k = 19). A further 10 stipulated or recommended minimum usage; either a number of uses or modules to be completed, whilst 15 observed spontaneous usage of the intervention as a measure.

There were 33 interventions in which caregivers’ participated as individuals; eight interventions involved group-participation, whilst four were targeted at caregiving dyads. There were six studies in which some parts were undertaken individually with others undertaken in a group. Where studies employed a comparator group (k = 33), the majority received some form of information only (k = 13), whilst being assigned to the waitlist group (k = 6) or simply receiving no intervention (k = 6) were the other most frequent forms of comparison.

Approach

Our full categorisation of approach using Chi & Demiris’54 classification system is presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Categorization of approaches and modes of delivery.

| Study No. | Study Design | APPROACH (Chi & Demiris, 2015) | MODE OF DELIVERY (Webb et al., 2010) | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Approach: Education | Approach: Consultation | Approach: Social | Approach: CBT | Approach: Data Collection | Approach: Clinical Care Delivery | Automated: Enrich | Automated: Tailor | Automated: Follow-Up | Communicative: Scheduled | Communicative: Advisor | Communicative: Peer | Advisor Role | Advisor pre-intervention experience/ qualifications | Supplementary: E mail | Supplementary: Phone | Supplementary: SMS | Supplementary: Videoconferencing | ||

| 3 | RCT | x | x | x | x | x | x | Coach | Principal Investigator | x | |||||||||

| 4 | RCT | x | x | x | x | x | Facilitator | Psychologist | x | ||||||||||

| 6 | RCT | x | x | x | x | x | |||||||||||||

| 7 | RCT | x | x | x | x | x | Educator | Certified interventionist | |||||||||||

| 10 | RCT | x | x | ||||||||||||||||

| 11 | RCT | x | x | x | x | x | Facilitator | Social Worker | |||||||||||

| 12 | RCT | x | x | x | x | x | Moderator | Miscellaneous clinical professionals | |||||||||||

| 15 | RCT | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | Expert | Alzheimer's Information Specialist | |||||||||

| 16 | RCT | x | x | x | x | x | x | Expert | Dementia Care Professionals | ||||||||||

| 18 | RCT | x | x | ||||||||||||||||

| 20 | RCT | x | x | x | x | Counsellor | Psychologist | x | |||||||||||

| 21 | RCT | x | x | Therapist | No information | ||||||||||||||

| 23 | RCT | x | x | Facilitator | No information | ||||||||||||||

| 24 | RCT | x | x | x | Therapist | Occupational Therapist | x | ||||||||||||

| 26 | RCT | x | x | x | x | Facilitator | Social Worker; Nurse | x | |||||||||||

| 29 | RCT | x | x | x | Therapist | Clinical Psychologist | x | x | |||||||||||

| 30 | RCT | x | x | x | |||||||||||||||

| 31 | RCT | x | x | x | x | ||||||||||||||

| 33 | RCT | x | x | x | x | x | Expert | No information | x | ||||||||||

| 38 | RCT | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | Expert | Clinical Team | |||||||||

| 40 | RCT | x | x | x | x | x | Coach | No information | |||||||||||

| 41 | RCT | x | x | x | x | Moderator | Clinical Case Manager | ||||||||||||

| 42 | RCT | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | Expert | Nurse | x | ||||||||

| 46 | RCT | x | x | x | x | Therapist | Certified interventionist | x | |||||||||||

| 47 | RCT | x | x | x | x | ||||||||||||||

| 48 | RCT | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | Coach | Psychologist | x | ||||||||

| 2 | NCBA | x | x | x | x | Facilitator | Principal Investigator | x | |||||||||||

| 5 | NCBA | x | x | x | x | Therapist | Clinician | x | |||||||||||

| 8 | NCBA | x | x | x | x | x | |||||||||||||

| 9 | NCBA | x | x | x | x | x | Expert | Nurse | |||||||||||

| 13 | NCBA | x | x | ||||||||||||||||

| 14 | NCBA | x | x | x | x | x | Facilitator | No information | x | ||||||||||

| 19 | NCBA | x | x | Expert | Miscellaneous clinical professionals | ||||||||||||||

| 22 | NCBA | x | x | x | x | x | Therapist | Miscellaneous clinical professionals | |||||||||||

| 25 | NCBA | x | x | x | x | x | x | Educator | Dementia Nurse | x | |||||||||

| 32 | NCBA | Facilitator | Psychologist | ||||||||||||||||

| 35 | NCBA | x | x | x | x | Expert | Miscellaneous clinical professionals | x | x | ||||||||||

| 36 | NCBA | x | x | ||||||||||||||||

| 37 | NCBA | x | x | x | x | Educator | Nurse | ||||||||||||

| 43 | NCBA | x | x | Educator | Dementia Nurse | x | |||||||||||||

| 49 | NCBA | x | x | x | x | Coach | Psychologist; Clinical Case Manager | ||||||||||||

| 50 | NCBA | x | x | x | Coach | Social Worker | |||||||||||||

| 51 | NCBA | x | x | x | x | Coach | Licensed Counsellor | x | |||||||||||

| 52 | NCBA | x | x | x | Moderator | Miscellaneous clinical professionals; experienced caregiver | x | ||||||||||||

| 17 | CBA | x | x | x | x | x | Care Manager | Miscellaneous clinical professionals | |||||||||||

| 27 | CBA | x | x | x | x | Facilitator | Social Worker; Nurse | ||||||||||||

| 28 | CBA | x | x | x | |||||||||||||||

| 34 | CBA | x | x | x | Moderator | Principal Investigator | x | ||||||||||||

| 39 | CBA | x | x | x | |||||||||||||||

| 44 | CBA | x | x | Moderator | Research Team | x | |||||||||||||

| 45 | CBA | x | x | x | x | ||||||||||||||

We observed that just under half used only one type of approach (k = 27), with 21 studies using two and two studies83,96 employing three approaches and one95 using four. Education was the most frequently adopted approach both overall (k = 38) and in single-approach studies (50%) within which a wide variety of implementation methods was observed. Almost half of the studies made information available without expectation as to what participants consumed or accessed (k = 17).

Other strategies include modules with homework to be evaluated (k = 6), the release of newer material following successful completion of modules (k = 2) or presenting users with more personalized information dependent on data-entered or questions posed (k = 5). Where studies detailed a combination of approaches the most frequently observed was social (i.e. peer-to-peer) and education (k = 12).

Modes of delivery

Our full summary of application of Webb et al.'s56 mode of delivery framework is presented in Table 2. Thirty-seven interventions were classified as using a combination of at least one automated and one communication function, whereas 14 only used one of either. The most frequently observed automated function used was the ‘automated enriched’ environment (k = 38).

In terms of communicative functions, 22 interventions afforded scheduled access to an advisor, who performed a variety of roles such as delivering counselling or therapy (k = 9), or facilitating timetabled group videoconferencing sessions (k = 6). Another 17 involved communication with an advisor, albeit the amount or regularity of correspondence was not always stipulated. These roles included providing expert guidance (k = 8), facilitating content (k = 8), or delivering therapy or counselling (k = 7). Where an advisor's prior experience or qualifications were described, the most common were psychologists (k = 11), nurses (k = 8) and therapists (k = 5).

Eighteen interventions incorporated web-based forums to facilitate access to peers (‘peer-peer’ mode). Regarding how interventions were supported by supplementary modes of communication; email (k = 11), videoconferencing (k = 5) and telephone (k = 9) were used.

No single combination of automative & communicative functions predominated, with the most frequent unique classification pairing (k = 14) being an ‘enriched’ environment accompanied by ‘scheduled’ contact with an advisor. A few interventions also enabled peer access (k = 4). Within interventions that combined enriched environment with peer access (k = 15), five also involved ‘scheduled’ contact with an advisor; another five included unscheduled contact.

Use of theory

We observed a lack of reference to the theoretical-base in underpinning intervention design and implementation, identifying just 14 interventions that specified at least one theory or construct. These are narratively summarised here using the TCS’ classifications. All of the 14 were classified as either referencing theory, such as social learning62 and social cognition theory,70,72 or using it as a basis for specific aspects (items 1–6). A theory or model of behaviour (e.g. cognitive behaviour theory, 80) was mentioned in four interventions62,70,80,105 whilst seven used a theory or predictor (e.g. Meleis’ theory of transition) to select or develop intervention technique.64,68,72,74,78,92,104 A theory or predictor (e.g. stress-coping and adaptation paradigms) was used to tailor techniques to recipients in two interventions.84,85 From items linking theories or constructs to interventions,7–11 at least one theory-relevant construct was linked to the technique in four interventions64,68,74,78 and at least one technique was linked to a theory in five interventions.70,72,80,84,85 Examples of the theories or predictors extracted include Meleis’ theory of transition,68 the DICE (Describe, Investigate, Create, Evaluate) approach78; communities of practice model110 and Kales’111 theoretical framework for reasons and management of BPSD93; alongside stress, coping and adaptation paradigms62,64,72,74,84,85,106; Social Learning Theory62 and Social Cognition Theory.70,72

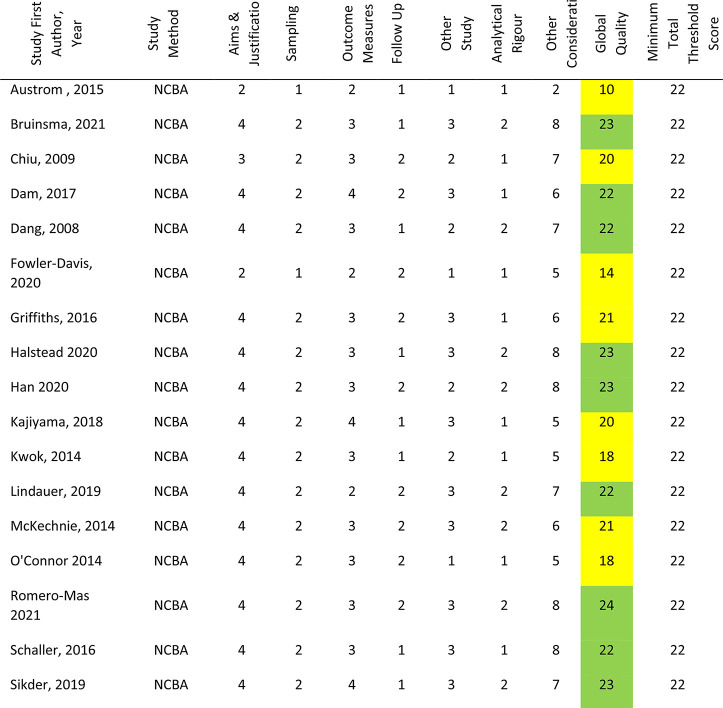

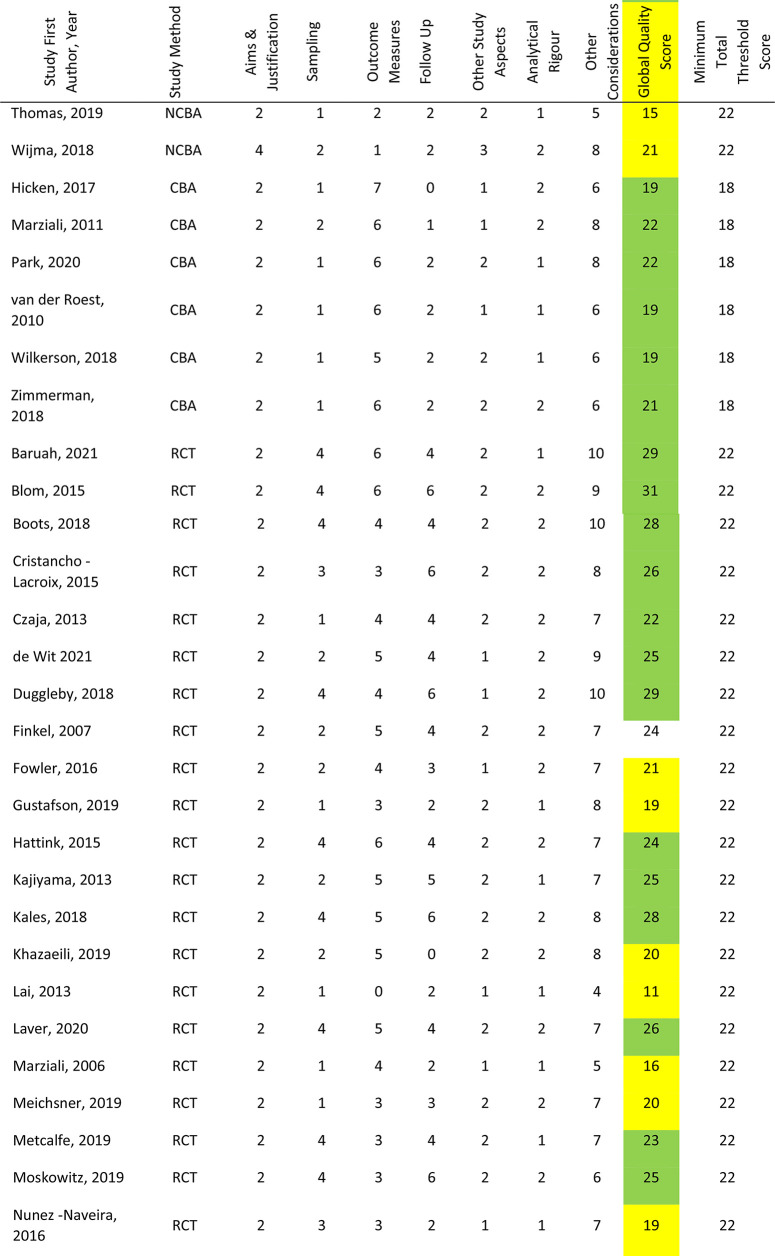

Risk of bias analysis

As illustrated in Table 3, 32 studies (63%) were scored as meeting the ICROMS criteria, whereas 19 studies (37%) did not score sufficiently. Of the 26 RCT studies, scores ranged from 11 to 31 (mean 23.15, median 24); nine (38%) did not meet the minimum score threshold of 22. Within the six CBA studies scores ranged from 19 to 22 (mean 20.33, median 20), all of which met the minimum score threshold of 18. Furthermore, there were 19 NCBA studies, whose scores ranged from 10 to 23 (mean 20.12, median 21); 11 studies (58%) met the minimum score threshold of 22. Specific sections that consistently received low or no scores were sampling and outcomes. Within these, the criteria not met were lack of allocation concealment, blinding and blinded-assessment of outcome measures. Other criteria lacking evidence were results free of other bias, follow-up of patients and incomplete outcome data addressed. The latter was reflected in the fact that only 26 studies reported attrition rates; ranging from just one participant not completing outcome measures60,83 to 67% with incomplete or missing data.105 Reasons for dropout and comparative statistics for completers and non-completers were seldom provided.

Table 3.

Risk of Bias Assessments.

|

|

|

Correspondingly, power calculations to determine minimum number of participants were detailed in just 15 studies; all but one reported achieving their original participant target.

Effectiveness of internet-facilitated interventions on caregivers’ outcomes

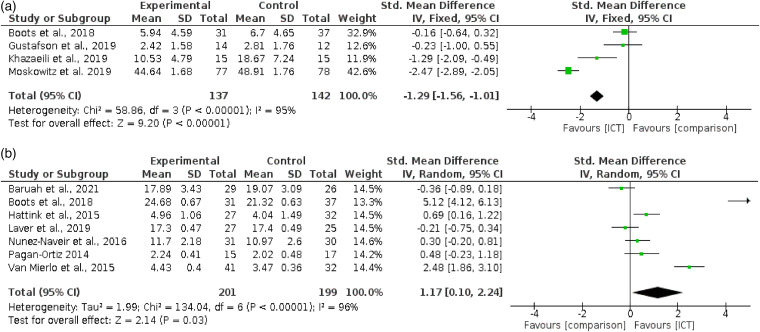

Anxiety

As depicted in figure 2 a), 4 studies62,73,79,104 reported anxiety outcomes. Comparator groups were either no exposure/information only62,73,79 or waitlist.104 The fixed-effect meta-analysis demonstrated a significant effect of interventions, compared with controls, on reducing anxiety; (4 RCTs; n = 279; SMD −1.29, 95% CI; −1.56 to −1.01; P < 0.01; I2 = 95%; GRADE quality of evidence very low).

Figure 2.

Meta-analysis on caregivers’ psychological outcomes (a) Comparing efficacy of internet-facilitated interventions with comparators on improving caregivers’ anxiety outcomes. (b) Comparing efficacy of Internet-facilitated interventions with comparators on improving caregivers’ sense of mastery outcomes.

The substantial heterogeneity rate reflects the diverse intervention features within these studies. Intervention length in the American studies was either six weeks,104 or 3 months.73 In both the European62 and Iranian79 studies, intervention duration was eight weeks. Two were CBT/psychotherapy-based,79,104 whereas one combined psychoeducation with social support73 with the other combining psychoeducation with peer support and access to an advisor.62 Participants completed two at their own pace73 whereas one gave guidance62 and one involved weekly scheduled contact with an advisor.79,104 In addition, three of the four studies were identified as theory-based62,73,104 and the other was an online-adaptation of a face-to-face technique.79 We could not fully compare populations due to one study79 only providing an age range for the overall sample and no gender-split information.

Sense of mastery

Seven RCTs62,74,82,89,91,99,105 reported sense of mastery outcome data. Comparator groups were either no exposure/information only,62,89,91,99,105 waitlist74 or face-to-face delivery.82 The random-effects meta-analysis demonstrated a significant effect of internet-facilitated interventions compared to controls, on increasing sense of mastery (7 RCTs; n = 400; SMD 1.17, 95% CI; 0.1 to 2.24; P = 0.03; I2 = 96%; GRADE quality of evidence very low). This is depicted in Figure 2 b).

Two outliers were identified62,105 whose CI's did not overlap with the model's overall CI. Without these studies, heterogeneity remained moderate (I2 = 61%) reflecting the diverse features across interventions. Of the four European studies,62,74,89,99 one collected data to provide personalised information,99 two combined psychoeducation with peer support,74,89 whilst the remaining combined psychoeducation with peer support and access to an advisor.

These latter delivery modes were also used in the American study.91 In the study conducted in India,105 caregivers completed interactive educational exercises, whereas the study conducted in Australia82 provided consultation to the caregiving-dyad through scheduled bi-weekly appointments. Participants completed four interventions at their own pace89,91,99,105 whereas two gave guidance or recommended minimum usage.62,74 All were of differing length, from one month91 to 12 months.99 Whilst all care-recipients were dementia-diagnosed, we were unable to compare populations further due to lack of data on age89 and gender split.91

Other outcomes

Seven studies reported burden outcomes. The random-effects meta-analysis demonstrated that there was no significant effect of interventions, compared with controls, on reduction of burden (7 RCTs; n = 617; SMD −0.47, 95% CI −1.13 to 0.18 P = 0.16; I2 = 93%; GRADE quality of evidence very low). Two outlier studies79,104 were identified whose CI's did not overlap with the model's overall CI. Without these heterogeneity reduced to low (I2 = 9%), although the model remained non-significant (5 RCTs; n = 432; SMD −0.04, 95% CI −0.16 to 0.25; P = 0.66).

Ten studies reported depression outcomes. The random-effects meta-analysis demonstrated that there was no significant difference between groups at post-intervention measurement (10 RCTs, n = 656; SMD −0.28, 95% CI −0.81 to 0.26; P = 0.12; I2 = 90%; GRADE quality of evidence very low). We identified one outlier study104 whose CI's did not overlap with the model's overall CI. Without these heterogeneity reduced to low (I2 = 9%), although the model remained non-significant (9 RCTs; n = 501; SMD −0.05; 95% CI −0.23 to 0.13; P = 0.59).

Five studies reported stress outcomes. The random-effects meta-analysis demonstrated no significant effect of interventions, compared with controls, on reducing stress measurements (5 RCTs; n = 302; SMD −1.42, 95% CI −2.95 to 0.1; P = 0.07; I2 = 97%; GRADE quality of evidence very low). Two outlier studies62,104 were identified whose CI's did not overlap with the model's overall CI. Without these heterogeneity reduced to low (I2 = 0%), although the model remained non-significant (3 RCTs; n = 179; SMD 0.06, 95% CI −0.23 to 0.35; P = 0.69).

Six studies reported strain outcomes. The random-effects meta-analysis demonstrated no significant effect of interventions, compared with controls, on strain measurements (6 RCT's; n = 563; SMD −0.07, 95% CI −0.49 to 0.31; P = 0.7; I2 = 87%; GRADE quality of evidence very low). We did not identify any outlier studies.

Four studies reported HRQoL outcomes using three different measurement instruments. The fixed-effect meta-analysis demonstrated no significant effect of interventions, compared with controls, on increasing HRQoL measurements (4 RCTs; n = 497; SMD 0.07, 95%CI −0.10 to 0.25; P = 0.4; I2 = 0%; GRADE quality of evidence very low).

Four studies reported PQoL measures using four different measurement instruments. The fixed-effect meta-analysis demonstrated that there was no significant effect of interventions on increasing PQoL measures (4 RCT's; n = 472; SMD 0.01, 95%CI −0.19 to 0.17; P = 0.91; I2 = 0%; GRADE quality of evidence very low).

Five studies reported self-efficacy outcomes. The random-effect meta-analysis demonstrated that there was no significant effect of interventions on increasing self-efficacy compared with controls (5 RCTs; n = 444; SMD 0.92, 95% CI; −0.06 to 1.9; P = 0.06; I2 = 95%; GRADE quality of evidence very low). We identified one outlier study62 whose CI's did not overlap with the model's overall CI. Without this, heterogeneity reduced to low (I2 = 0%), although the model remained non-significant (4 RCTs; n = 376; SMD 0.13, 95% CI −0.07 to 0.33; P = 0.22).

Follow-up measures

Usable follow-up data was only reported in three RCTs64,67,106 with measurements at six months from baseline. The fixed-effect meta-analyses demonstrated no significant effect of interventions, compared with controls, on either decreasing burden measures (2 RCT's; n = 155; SMD 0.09, 95%CI −0.23 to 0.41; P = 0.59; I2 = 26%; GRADE quality of evidence very low) or increasing self-efficacy measures (3 RCT's; n = 321; SMD 0.05, 95%CI −0.17 to 0.27; P = 0.67; I2 = 0%; GRADE quality of evidence very low).

Most efficacious intervention approach and design feature

Despite adequate numbers of studies available for depression outcomes (k = 10), intended exploratory meta-regression to explore effects of different intervention features were precluded by a lack of appropriately populated groups. Neither intervention approach (e.g. education used k = 7, not used k = 3), mode of delivery (e.g. communication with an advisor used k = 2, not used k = 8), nor participation type (individual participation k = 8; group participation k = 2) yielded the group distributions necessary.

Discussion

Principal findings

To our knowledge, this is the first review to include diagnoses of rarer NDs (e.g. HD, MS, ALS) when examining the common features and effectiveness of internet-facilitated interventions aimed at informal caregivers. Yet even though our highly sensitive search retrieved 51 quantitative studies, all but three79,106,108 involved ADRD; two involved MS, another ALS. This reflects the lack of research into non-ADRD caregivers, despite the growth of diagnoses for disorders such as PD. Apart from the consistency of reporting the patient's diagnosis, details of other demographic variables were too divergent across studies to be able to derive salient information about those caregivers participating.

Most interventions took place in either North America or Europe (84%). Yet geographical location was an isolated commonality, for the narrative review highlighted an array of approaches, modes of delivery and theoretical bases. Although the majority used an educational approach (75%), an enriched environment (75%) and either scheduled or unscheduled contact with an advisor (76%), between-study differences were apparent in the multifarious ways in which individual features were combined. This incongruity was most visible when quantitatively synthesizing the 20 RCT's that provided usable data. High heterogeneity for both anxiety and mastery outcome meta-analyses reflected disparities such as interventions’ lengths, dosages and approaches. Yet despite similar reviews (e.g.42,43,44 also observing these differences, they did not consistently report problematic heterogeneity for these outcomes. One explanation for this contrast is that our review's recency naturally meant that we included additional studies. Some of these studies (e.g.79,104 were subsequently identified as outliers, with clear differences observed in the levels of heterogeneity in meta-analyses of for depression (0% vs. 90%), burden (9% vs. 93%) and stress (0% vs. 97%) outcomes’ heterogeneity levels.

Another unifying feature across these and another outlier study62 is that they were the only ones to involve scheduled contact with an advisor. Previous reviews have reported improvements to interventions’ effects on outcomes when involving a professional.44,113 ND-caregivers value asynchronous electronic communication (e.g. email) with professionals for affording both more accurate documentation of symptom changes113 and management of challenging situations (e.g. behavioral disturbances) outside of usual clinical hours.114 However, advisors can undertake a variety of roles (e.g. delivering content, moderating web-based forums) and the mechanisms underlying any enhanced efficacy require exploration. The interventionist's confidence in delivering material or support,115 or ability to adapt their communication style to web-based formats,116 could also be influential.

Intervention features’ heterogeneity also precluded assessment of which were the most efficacious. No approach or mode of delivery afforded within-outcome groups of comparable sizes. Interventions were either based on a select few features (e.g. education k = 38), or disparate combinations of approaches and modes of delivery, leading to too few cases. The lack of interventions reporting a theoretical basis (27%) similarly impeded quantitative analysis. This lacuna remains a persistent observation across similar reviews (e.g..41,43,114,129).

Follow-up data was only reported in five studies, with none reporting measures later than six months from baseline. In fact, only six of the 20 RCT's providing suitable data for analyses reported measures later than three months post baseline, with just one beyond six months (100; at 12 months). It is feasible that certain outcomes, such as quality of life require a longer time-period for significant reductions to manifest.113 Furthermore, these outcomes may be intensified by the onset of factors external to the intervention's scope; such as deterioration in patient-symptomology117 or increased caregiving-hours.118 Conversely, caregivers may not exhibit sufficiently severe symptoms at baseline for an intervention to demonstrate a meaningful effect. Study authors would therefore need to apply any instrument threshold scores that delineate moderate/high levels of an outcome, enabling them to target participants with significant levels of baseline symptoms.

Attrition data was provided in 31 studies, specifically in 17 out of 20 RCTs with usable data. Rates did not appear to be related to use of a supplementary mode (e.g. telephone, email), or any other intervention features. Metrics and measures about actual intervention usage varied across studies, homologous to other reviews (e.g.45,119). Low usage and high attrition rates are well documented in internet-facilitated intervention studies.29,120 Here, inconsistently reported reasons for drop out inhibited the exploration of possible causes. One possible antecedent; caregivers’ lack of capability with internet-facilitated technology, was mostly unassessed either pre- or post-intervention. Expectations that already-burdened caregivers, whether possessing high or low proficiency in information and communication technology (ICT), master a new platform may be impractical121; for it is often incommensurate with patient-monitoring responsibilities.122 In absence of any thorough investigation, high attrition is a persistent issue in internet-facilitated technology intervention studies.

Strengths and limitations

Among this review's strengths is the robust number of RCT's (k = 26) and studies overall (k = 51) retrieved through employing a highly sensitive search. Substantial data on the different approaches was accumulated, theoretical bases and design features employed, which were categorized using established classification systems. We were also able to extract sufficient statistical data to conduct meta-analyses for nine separate outcomes. Yet our findings should also be cautiously interpreted on account of the GRADE evidence-quality assessments, which were all very low.

Circumspection is also required when attempting to generalize our findings. By restricting the search to English language studies, relevant studies in other languages may have been missed. Similarly, 45 of the 51 studies were conducted in the USA, Europe or Australia, indicating a paucity of important perspectives from non-Western cultures and low to middle-income countries (LMIC's). For example, Magaña, Martinez &, Loyola's123 meta-analysis of caregiving in LMIC's calculated adverse health outcomes for informal caregivers of both South American and Asian, but not African, countries. A more diverse geographical spread in research is clearly needed before attempting to apply extant knowledge or techniques to populations considered previously underrepresented in the literature.

Future directions

Our meta-analytic calculations for subjective sense of mastery outcomes incorporated solely self-report measures. Future meta-analyses could extend our results by exploring whether interventions achieve commensurate improvements in objective mastery measures. Comparisons of both types have hitherto been examined in narrative,127 scoping129,131 and systematic reviews.25,128,130 Results range from improvements in subjective127 or objective only130 to both.25,128,131 Yet these reviews also exhibit the between-intervention heterogeneity that our review has highlighted. Differences in population features, such as some interventions including formal caregivers, or methodological features, such as comparing both established and intervention-specific outcomes-measures, possibly account for some of these disparate findings.

Other comparisons across studies remain problematic, due to the proliferation of different study designs, quality and outcome measures used. Reportage of population characteristics is similarly heterogeneous, limiting any direct comparisons. Certain sociodemographic variables may be indicative of other factors that influence intervention-usage and efficacy, such as baseline ICT skills, confidence or attitudes toward ICT-usage. Researchers need to not only use established scales to detect these constructs, but also build them into their intervention-implementation, (e.g. through appropriate and consistent technical support).

Level of engagement with the intervention is also salient, although it is often only measured post-intervention using non-validated questionnaires.124 Preferably, engagement needs to be clearly defined and continuously assessed throughout testing, using measures which go beyond simple usage-frequency metrics (e.g. dwell-time, components-viewed and completed). By identifying propitious or inhibitory usage components in-situ, rather than waiting for retrospective feedback, it is possible to elucidate the seemingly inevitable tool-usage decline observed at trials’ latter stages.45

Since internet-facilitated intervention studies were first published, smartphone ownership has greatly increased, providing access to applications housing multiple functions.33 As ICT access for traditionally underserved cohorts continues to expand, the opportunity to better support informal caregivers needs to be explored Intervention design needs to adapt to recent shifts in how individuals favour different devices for different purposes.125 Traditionally desktop computer-based activities, such as reading lengthy information studies, or completing multi-item measurement questionnaires, need to be adapted for different size-screens.

Conclusion

Our comprehensive review demonstrated some support for the efficacy of internet-facilitated interventions in improving sense of mastery and anxiety outcomes for informal caregivers of ND-diagnosed, community-based patients. However, these changes were principally detected after short-term intervention-exposure, with most lasting three months or less. Not only are longer intervention testing-periods required; there remains a paucity of internet-facilitated interventions for caregivers in rare ND-Diagnoses. The growing prevalence of other NDs, such as PD, will undoubtedly engender a concomitant growth in the numbers of informal caregivers. Therefore, practical interventions to safeguard their psychological health is an evident research priority.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-dhj-10.1177_20552076221129069 for Internet-facilitated interventions for informal caregivers of patients with neurodegenerative disorders: Systematic review and meta-analysis by Neil Boyt, Aileen K Ho, Hannah Morris-Bankole and Jacqueline Sin in Digital Health

Supplemental material, sj-docx-2-dhj-10.1177_20552076221129069 for Internet-facilitated interventions for informal caregivers of patients with neurodegenerative disorders: Systematic review and meta-analysis by Neil Boyt, Aileen K Ho, Hannah Morris-Bankole and Jacqueline Sin in Digital Health

Acknowledgements

There were no other contributors to this article.

Footnotes

Guarantor: NB.

Contributorship: All named authors approve this version of the manuscript and give consent to the submission of this paper for consideration. All authors have contributed to the design, conduct and writing of the systematic review, and approved the manuscript before its submission.

Author contributions: All authors have contributed to the design, conduct and writing of this systematic review.

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD: Neil Boyt https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8769-1403

Supplemental material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1.Adams JL, Myers TL, Waddell EMet al. et al. Telemedicine: A valuable tool in neurodegenerative diseases. Curr Geriatr Rep 2020; 9: 72–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Feigin VL, Nichols E, Alam Tet al. et al. Global, regional, and national burden of neurological disorders, 1990–2016: A systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2016. The Lancet Neurology 2019; 18: 459–480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aubeeluck A, Stupple EJN, Schofield MBet al. et al. An international validation of a clinical tool to assess Carers’ quality of life in huntington’s disease. Front Psychol 2019; 10: 1658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.de Wit J, Bakker LA, van Groenestijn AC, et al. Psychological distress and coping styles of caregivers of patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: A longitudinal study. Amyotroph Lateral Scler Frontotemporal Degener . 2019; 20: 235–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Milner L, Soundy A. Motivation and experiences of role transition in spousal caregivers of people with multiple sclerosis. Int J Ther Rehabil 2018; 25: 405–413. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bressan V, Visintini C, Palese A. What do family caregivers of people with dementia need? A mixed-method systematic review. Health Soc Care Community 2020; 28: 1942–1960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clare L, Teale JC, Toms Get al. Cognitive rehabilitation, self-management, psychotherapeutic and caregiver support interventions in progressive neurodegenerative conditions: A scoping review. Neurorehabilitation 2018; 43: 443–471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maresova P, Hruska J, Klimova Bet al. et al. Activities of daily living and associated costs in the most widespread neurodegenerative diseases: A systematic review. Clin Interv Aging 2020; 15: 1841–1862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mollica MA, Smith AW, Kent EE. Caregiving tasks and unmet supportive care needs of family caregivers: A U.S. Population-based study. Patient Education and Counseling 2020; 103: 626–634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Plöthner M, Schmidt K, de Jong Let al. et al. Needs and preferences of informal caregivers regarding outpatient care for the elderly: A systematic literature review. BMC Geriatr . 2019; 19: 82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lindt N, van Berkel J, Mulder BC. Determinants of overburdening among informal carers: A systematic review. BMC Geriatr 2020; 20: 304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Page TE, Farina N, Brown Aet al. Instruments measuring the disease-specific quality of life of family carers of people with neurodegenerative diseases: A systematic review. BMJ Open 2017; 7: e013611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Roland K P, Chappell NL. Caregiver experiences across three neurodegenerative diseases: Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, and Parkinson’s with dementia. J Aging Health 2019; 31: 256–279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Smith T, Saunders A, Heard J. Trajectory of psychosocial measures amongst informal caregivers: Case-controlled study of 1375 informal caregivers from the English longitudinal study of ageing. Geriatrics 2020; 5: 26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kishita N, Hammond L, Dietrich CMet al. et al. Which interventions work for dementia family carers?: An updated systematic review of randomized controlled trials of carer interventions . Int Psychogeriatr . 2018; 30: 1679–1696 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mosley PE, Moodie R, Dissanayaka N. Caregiver burden in Parkinson disease: A critical review of recent literature. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol . 2017; 30: 235–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kumar H, Ansari S, Kumar Vet al. et al. Severity of caregiver stress in relation to severity of disease in persons with Parkinson's. Cureus . 2019; 11: e4358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Alves LCS, Monteiro DQ, Bento SRet al. et al. Burnout syndrome in informal caregivers of older adults with dementia: A systematic review. Dement Neuropsychol . 2019; 13: 415–421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Collins RN, Kishita N. Prevalence of depression and burden among informal caregivers of people with dementia: A meta-analysis. Ageing Soc 2020; 40: 2355–2392. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Romero-Martínez Á, Hidalgo-Moreno G, Moya-Albiol L. Neuropsychological consequences of chronic stress: The case of informal caregivers. Aging Ment Health . 2020; 24: 259–271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hansen DM, Sheehan D, Stephenson P. The caregiver’s experience with an illness blog. Journal of Hospice & Palliative Nursing 2016; 18: 464–469. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Young HM, Bell JF, Whitney RLet al. et al. Social determinants of health: Underreported heterogeneity in systematic reviews of caregiver interventions. Gerontologist 2020; 60: S14–S28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chan CY, Cheung G, Martinez-Ruiz A, et al. Caregiving burnout of community-dwelling people with dementia in Hong Kong and New Zealand: A cross-sectional study. BMC Geriatr 2021; 21: 261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cole L, Samsi K, Manthorpe J. Is there an “optimal time” to move to a care home for a person with dementia? A systematic review of the literature. Int Psychogeriatr 2018; 30: 1649–1670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Frias CE, Garcia-Pascual M, Montoro Met al. et al. Effectiveness of a psychoeducational intervention for caregivers of people with dementia with regard to burden, anxiety and depression: A systematic review. J Adv Nurs . 2020; 76: 787–802 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Teles S, Ferreira A, Paúl C. Access and retention of informal dementia caregivers in psychosocial interventions: A cross-sectional study. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 2021; 93: 104289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Verreault P, Turcotte V, Ouellet M-Cet al. et al. Efficacy of cognitive-behavioural therapy interventions on reducing burden for caregivers of older adults with a neurocognitive disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Cogn Behav Ther 2021; 50: 19–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hill P, Broady TR. Understanding the social and emotional needs of carers. Social Policy Research Centre, UNSW Sydney 2019.