Abstract

Background/purpose

Previous studies have shown that some of the patients with oral mucosal dysesthesia but without objective oral mucosal manifestations (so-called oral dysesthesia patients in this study) may have good responses to oral nystatin treatment. This study evaluated the efficacy of oral nystatin treatment for oral dysesthesia patients and the necessity of Candida culture test before oral nystatin treatment.

Materials and methods

The 147 oral dysesthesia patients were divided into 3 groups: Candida culture (+) group (n = 29), Candida culture (−) group (n = 34), and without Candida culture test group (n = 84), and treated with oral nystatin. The pain improvement was evaluated by the reduction of numeric pain rating scale (NRS) and global perceived effects (GPE). We defined the GPE score ≥4 points as a great improvement.

Results

We found that 44.8% of 29 patients in the Candida culture (+) group, 47.1% of 34 patients in the Candida culture (−) group, and 47.6% of 84 patients in the without Candida culture test group showed a significant reduction in the NRS score and achieved a great improvement after oral nystatin treatment for 1–4 weeks. Moreover, 72.4% of our 29 patients with Candida culture test achieved a great improvement within one week, and all the 29 patients achieved a great improvement within 4 weeks of oral nystatin treatment.

Conclusion

A portion of our oral dysesthesia patients are infected by Candida and it is beneficial to our patients to use oral nystatin treatment before the Candida culture test.

Keywords: Nystatin treatment, Oral mucosal dysesthesia, Candida culture, Oral candidiasis, Burning mouth syndrome

Introduction

In the oral medicine clinic, many patients with oral mucosal dysesthesia but without objective oral mucosal manifestations (so-called oral dysesthesia patients in this study) are encountered. The three most common symptoms for oral dysesthesia patients are burning, numbness, and tingling sensation on the tongue or hard palate mucosa. However, these oral dysesthesia patients are usually without visible or palpable oral mucosal manifestations or pain but are often diagnosed as having burning mouth syndrome (BMS).

The BMS is typically characterized by the burning and painful sensations on the oral mucosa which is normal in appearance.1,2 BMS is more commonly found in women than in men,3,4 particularly in women during or after menopause.5, 6, 7 The etiology of BMS is multifactorial, and BMS can be classified as primary and secondary BMS, traditionally.1, 2, 3 First, primary BMS is diagnosed by exclusion and the etiology of primary BMS is unknown. There are no organic local or systemic causes identified in patients with primary BMS. Some researchers consider the primary BMS to be a neuropathic disorder1,8, 9, 10, 11, 12 or caused by psychological factors.11, 12, 13, 14 Thus, these patients with primary BMS are often treated with anticonvulsants or antidepressants.1,13,15, 16, 17 Next, patients with secondary BMS are caused by local or systemic factors, such as oral candidiasis, hormonal imbalance, and/or nutrient deficiency.3,11,18, 19, 20

Oral candidiasis, an opportunistic infection, caused by Candida overgrowth, is a common cause of oral mucosal pain.21 Clinically, oral candidiasis can be divided into pseudomembranous, erythematous, and hyperplastic types according to the different clinical manifestations.22, 23, 24 In the past, the presence of Candida infection was preliminarily determined by whether obvious lesions were visible to the naked eyes. Recently, some research groups proposed the existence of a new type of oral candidiasis, that is, oral candidiasis with symptoms, usually oral mucosal pain, but without objective oral mucosal manifestations,20,25, 26, 27 and Cho et al. named this type of oral candidiasis “morphologically normal symptomatic candidiasis”.28

Various antifungal agents are used for the treatment of oral candidiasis, including topical and systemic agents.22,29 Among them, topical antifungal agents are the main recommended treatment for uncomplicated oral candidiasis. Nystatin is one of the most commonly used topical antifungal drugs with high efficacy, low cost, and fewer side effects, due to no absorption from the gastrointestinal tract.29, 30, 31, 32 There are various available forms of nystatin, such as oral suspension, topical cream, and oral pastille.24,31,33, 34, 35, 36, 37 Empirically, the treatment duration of nystatin can vary from 1 or 2–4 weeks.24,31,32,37,38

Clinically, the symptoms of morphologically normal symptomatic candidiasis are similar to the symptoms of BMS, and if the patients have no visible oral mucosal lesions, they are easy to be diagnosed as primary BMS and treated with antidepressants or anticonvulsants, such as clonazepam.12,15,16 However, for part of these patients, the effect of antidepressant or anticonvulsant treatment is limited. Hence, some patients with morphologically normal symptomatic candidiasis are suffered from pain that lasted for a long time, and they usually consult a variety of departments for treatment.4 Nevertheless, owing to the normal oral mucosal morphology, few physicians link this kind of oral mucosal pain to oral candidiasis. Based on our past clinical experience, we tried to treat oral dysesthesia patients with oral nystatin, and some of them improved greatly in a relatively short period of time. Therefore, this study tried to evaluate the efficacy of oral nystatin treatment for oral dysesthesia patients and the necessity of Candida culture test before oral nystatin treatment.

Materials and methods

Ethical approval

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board and Medical Ethics Committee of Chang Gung Memorial Hospital (No. 202200307B0). This study was reported according to the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines.

Study design

This study examined 252 patients who visited the oral mucosal disease clinic of Taipei Chang Gung Memorial Hospital (CGMH) between 2016 and 2021 with a chief complaint of oral mucosal pain or oral dysesthesia. The scheme of present study is shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Flow chart for analysis of patients with oral mucosal dysesthesia but without objective oral mucosal manifestations. OLP: oral lichen planus.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria for the patients in this study were described as follows: (1) those between 19 and 89 years old; (2) those with oral mucosal pain or oral mucosal dysesthesia; (3) those with other subjective symptoms, such as dry mouth, abnormal oral sensation, and taste dysfunctions; and (4) those without obvious oral mucosal lesions.

The exclusion criteria for the patients were described as follows: (1) those with obviously abnormal oral mucosa; (2) those with neurological disorders; (3) those with jawbone lesions; (4) those with dental problems; (5) those who received other treatments; (6) those who refused medication; and (7) those lost to the follow-up.

Diagnostic procedures and treatment

The clinical information including the age, gender, personal habit, systemic disease, all medications being taken, characteristics of oral mucosal dysesthesia, and nystatin treatment duration was collected from every oral dysesthesia patient. A single oral pathologist (M.L.C.) examined the oral cavities, prescribed the nystatin, and evaluated the oral nystatin treatment responses of all oral dysesthesia patients.

Laboratory blood tests, including complete blood counts, serum iron, ferritin, zinc, folic acid, vitamin B12, fasting blood glucose (FBG), and glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) were routinely examined at their first visit and collected within 2 months from the hospital records. The purpose of the blood tests was to clarify the general condition of patients and investigate the potential causes to exclude all possible diseases and hematinic deficiencies. All the above blood tests were performed in the Department of Laboratory Medicine, CGMH.

The method of the Candida culture test was described as follows. The oral mucosal surface where experienced pain or dysesthesia was firmly swabbed 4–5 times with a COPAN eSwab (Copan Italia SpA, Brescia, Italy) or a simple cotton swab. The sample was then cultured on inhibitory mold agar (IMA), IMA plate with chloramphenicol and gentamicin (ICG), and brain heart infusion (BHIA) agar, with the streaking method. After 5 days, the colonies were counted and sent into a matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization-time of flight mass spectrometer (MALDI-TOF-MS) to execute bacteria or fungi identification. The Candida culture tests were performed in the Department of Laboratory Microbiology, CGMH.

All oral dysesthesia patients were treated with an antifungal drug, nystatin oral suspension (MYCOSTATIN™ Oral Suspension, Genovate, Biotechnology Co., Ltd., Hsinchu, Taiwan; 100,000 U/mL; 4–6 mL; four times a day). Patients were instructed to gargle the nystatin oral suspension and maintain the solution contacting all the oral mucosa, especially the symptomatic oral mucosa for at least 10 min, and then spat it out. All oral dysesthesia patients were instructed and reviewed their nystatin usage methods at the next week recall.

Assessment of the effectiveness of oral nystatin treatment

After oral nystatin treatment, improvement of oral mucosal pain or dysesthesia was evaluated with the reduction of numeric pain rating scale (NRS) and global perceived effects (GPE). NRS is one of the most commonly used pain scales in medicine, with the pain scale ranging from 0 to 10 (no pain to the most severe pain, respectively).39, 40, 41 GPE is an effectiveness assessment tool that measures a change in the patient's chief complaint. In this study, GPE was adapted from Cavalcanti et al.,42, 43, 44 and it was scored by the patient (self-reported description) on a 5-point scale, ranging from: 1 = deterioration; 2 = no difference; 3 = mild improvement; 4 = much improvement; 5 = entirely improvement. We defined the GPE score ≥4 points as a great improvement of symptoms after oral nystatin treatment.

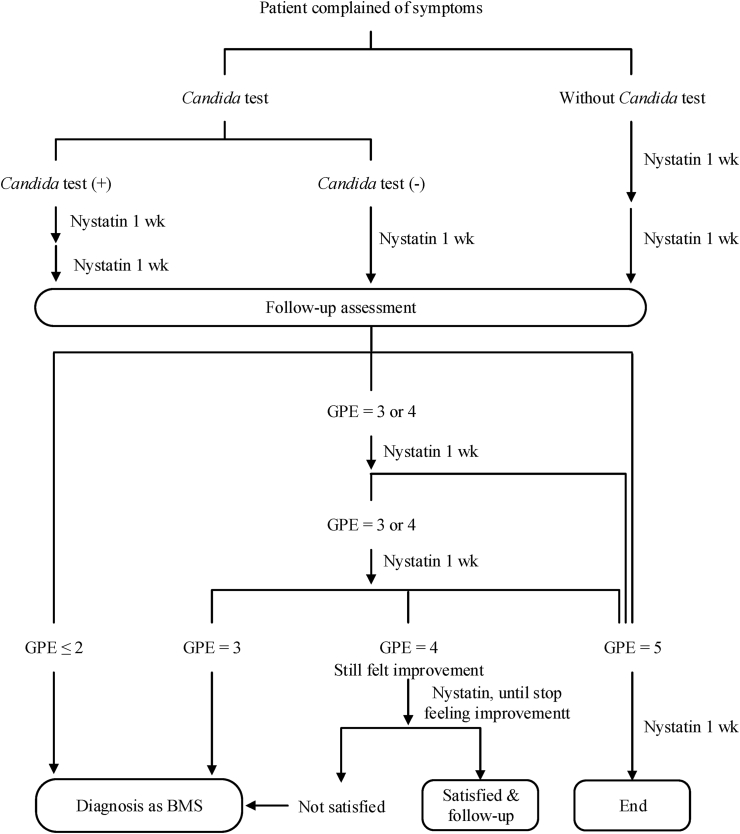

The scheme of the follow-up assessment and treatment protocol is shown in Fig. 2. Patients reporting the GPE score ≤2 points were regarded as insusceptibility to nystatin, resulting in diagnosis of BMS and termination of oral nystatin treatment after 1 week. Patients reporting the GPE score = 5 points were continually treated with oral nystatin for one more week and then discontinued. Patients reporting the GPE score = 3 or 4 points were constantly treated with oral nystatin and regularly followed up on the efficacy until they felt entirely improvement (the GPE score = 5 points) or stopped feeling improvement (after reporting several times of the GPE score = 4 points) but were satisfied with the treatment. On the other hand, patients repeatedly reporting the GPE score = 3 points or unsatisfied with solely oral nystatin treatment, even with the GPE score = 4 points, were diagnosed as having BMS, perhaps with oral candidiasis simultaneously, and arranged for additional treatments.

Fig. 2.

Flow chart of oral nystatin treatment and assessment of efficacy of oral nystatin treatment.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed with SPSS software (SPSS version 28.0.1; IBM, Chicago, IL, USA). The differences in age, NRS, and blood test results among groups were analyzed by two-tail t-test or analysis of variance (ANOVA), where appropriate. The differences between the initial NRS and final NRS in each group were analyzed by paired samples and two-tail t-test. The differences in gender, personal history, systemic disease, insomnia, taking hypnotics, dry mouth symptom, taste disturbance, types of oral mucosal dysesthesia, and the proportion of the GPE score ≥4 points were analyzed by chi-square test. In ANOVA test, the homogeneity of variance was analyzed by Levene's test at first. If the variance was homogeneous, LSD test would be conducted as the post hoc test of ANOVA. Otherwise, Games–Howell test would be conducted as the post hoc test of ANOVA in which the variance was heterogeneous. The result was considered to be significant if the P-value was less than 0.05.

Results

Of the 252 patients reviewed, 70 were excluded from the study because they did not meet the diagnostic criteria, one had the neurologic disease, two had dental problems, 16 were dropped, 7 were opposed to taking oral nystatin, and 9 received other treatments. Therefore, 147 (25 men and 122 women, age range 19–89 years, mean age 58.0 ± 14.1 years) oral dysesthesia patients were further analyzed in this study. Among the 147 oral dysesthesia patients, 63 were examined with Candida culture test; of them, 29 were positive and 34 were negative. The other 84 patients did not receive Candida culture test. Therefore, these 147 oral dysesthesia patients were divided into three groups: the Candida culture-positive [Candida culture (+)] group (n = 29), the Candida culture-negative [Candida culture (−)] group (n = 34), and the without Candida culture test group (n = 84) (Fig. 1).

Clinical characteristics and laboratory data

The demographic and clinical characteristics of the 147 oral dysesthesia patients are shown in Table 1. The age distribution, gender distribution, and medical history showed no significant differences among the three groups. The medical history here included patients with systemic disease, insomnia, or taking hypnotics. Less than 10% of patients had alcohol, betel nut, and cigarette consumption. Moreover, 78.2% of patients complained of dry mouth and 37.4% complained of taste disturbances (Table 1). Most of the taste disturbance patients had hypergeusia and/or phantogeusia, only a few patients felt hypogeusia. Hypergeusia patients felt very sensitive to spicy or salty food, and phantogeusia patients could feel salty, sweet, or bitter sensations even without eating any food.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of patients with oral mucosal dysesthesia but without objective oral mucosal manifestations.

| Demographic and clinical characteristics |

Candida culture (+) |

Candida culture (−) |

Without Candida culture test |

Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 29) | (n = 34) | (n = 84) | (n = 147) | |

| Age (y) | ||||

| Mean ± SD | 60.1 ± 13.7 | 54.4 ± 16.8 | 58.7 ± 12.9 | 58.0 ± 14.1 |

| Range | 33–85 | 20–88 | 19–89 | 19–89 |

| Gender | ||||

| Female | 22 (75.9) | 25 (75.8) | 75 (89.3) | 122 (83.0) |

| Male | 7 (24.1) | 8 (24.2) | 9 (10.7) | 25 (17.0) |

| Personal history | ||||

| Alcohol drinking | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (3.6) | 3 (2.0) |

| Betel nut chewing | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Cigarette smoking | 4 (13.8) | 0 (0.0) | 5 (6.0) | 9 (6.1) |

| Systemic disease | 23 (79.3) | 21 (61.8) | 62 (73.8) | 106 (72.1) |

| ≥ 2 diseases | 20 (69.0) | 14 (41.2) | 38 (45.2) | 72 (49.0) |

| Insomnia | 21 (72.4) | 22 (64.7) | 54 (64.3) | 97 (66.0) |

| Taking hypnotics | 16 (55.2) | 19 (55.9) | 34 (40.5) | 68 (46.3) |

| Dry mouth | 26 (89.7) | 25 (73.5) | 64 (76.2) | 115 (78.2) |

| Taste disturbance | 11 (37.9) | 15 (44.1) | 29 (34.5) | 55 (37.4) |

Abbreviations: “+”, presence of Candida; “−”, absence of Candida.

The data are presented as the patient number (%).

Because men tended to have higher blood hemoglobin, serum iron, and ferritin levels than women, these three mean levels were calculated separately for men and women (Table 2). There were no significant differences in laboratory blood data among the three groups, except that the ferritin level of female patients in the Candida culture (+) group was nearly twice as high as that in the Candida culture (−) group. The HbA1C values in all three groups were slightly above the normal upper limit (5.6%) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Laboratory data of patients with oral mucosal dysesthesia but without objective oral mucosal manifestations.

| Parameters |

Candida culture (+) |

Candida culture (−) |

Without Candida culture test |

P-value | Normal range |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 29) | (n = 34) | (n = 84) | |||

| FBG (mg/dL) | 99.6 ± 30.2 | 97.4 ± 18.6 | 101.9 ± 27.5 | 0.749 | 70–100 |

| HbA1c (%) | 5.9 ± 0.9 | 5.9 ± 0.4 | 6.1 ± 1.7 | 0.834 | 4.6–5.6 |

| Hb (g/dL) | 13.3 ± 1.3 | 13.7 ± 1.4 | 13.1 ± 1.3 | 0.112 | 12–17.5 |

| Female | 13.0 ± 0.7 | 13.1 ± 1.0 | 12.9 ± 1.3 | 0.722 | 12–16 |

| Male | 14.1 ± 2.2 | 15.2 ± 0.9 | 14.7 ± 0.5 | 0.297 | 13.5–17.5 |

| Iron (μg/dL) | 93.3 ± 31.0 | 107.9 ± 51.9 | 97.0 ± 37.1 | 0.331 | 40–160 |

| Female | 87.7 ± 24.9 | 102.1 ± 44.8 | 95.9 ± 37.8 | 0.448 | 40–150 |

| Male | 113.0 ± 43.6 | 123.8 ± 69.0 | 106.5 ± 30.4 | 0.794 | 50–160 |

| Ferritin (ng/mL) | 236.9 ± 189.3 | 150.1 ±186.0 | 143.5 ± 123.7 | 0.027a | 10–322 |

| Female | 217.0 ± 166.4a | 98.7 ± 89.1a | 131.1 ± 113.7 | 0.005a | 10–291 |

| Male | 303.3 ± 258.8 | 291.5 ± 233.7 | 247.5 ± 161.1 | 0.900 | 22–322 |

| Vitamin B12(pg/mL) | 978.6 ± 474.9 | 1002.6 ± 786.3 | 894.7 ± 432.1 | 0.585 | 197–771 |

| Folic acid (ng/mL) | 13.8 ± 5.7 | 14.0 ± 6.9 | 13.9 ± 8.5 | 0.996 | 4.6–18.7 |

| Homocysteine (μM) | 8.9 ± 2.0 | 10.1 ± 4.3 | 9.8 ± 2.6 | 0.282 | <12 |

| Zinc (μg/dL) | 81.7 ± 11.7 | 85.8 ± 11.4 | 81.3 ± 10.6 | 0.150 | 70–120 |

ANOVA, significant difference between the groups, P < 0.05.

Games–Howell post hoc test among groups. Abbreviations: “+”, presence of Candida; “−”, absence of Candida; FBG, fasting blood glucose; HbA1c, glycated hemoglobin; Hb, hemoglobin.

The Candida species in the 29 patients in the Candida culture (+) group are shown in Table 3. Of the 29 patients with the Candida culture (+), 22 (75.9%) were infected with Candida albicans and the other 7 (24.1%) were infected with other Candida species (Table 3).

Table 3.

Candida species in the 29 patients in the Candida culture (+) group.

| Candida species | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Candida albicans | 22 | 75.9 |

| Candida guilliermondii | 1 | 3.4 |

| Candida parapsilosis | 4 | 13.8 |

| Candida parapsilosis complex | 1 | 3.4 |

| Candida (unrecognized) | 1 | 3.4 |

| Total | 29 | 100.0 |

Outcome of oral nystatin treatment

After oral nystatin treatment, 69 (46.9%) of the 147 patients felt much improvement or entirely improvement (defined as the GPE score ≥4 points). Of the 69 patients with the GPE score ≥4 points, 13 (44.8% of 29 patients) were in the Candida culture (+) group, 16 (47.1% of 34 patients) were in the Candida culture (−) group, and 40 (47.6% of 84 patients) were in the without Candida culture test group (Fig. 1). There was no significant difference in the level of symptom improvement among the three different groups (P > 0.05).

A comparison of the changes of NRS score in the three groups with the GPE score ≥4 points before and after oral nystatin treatment is shown in Table 4. All three groups showed a significant pain reduction (all three P-value ≤0.003) after oral nystatin treatment. However, there were no statistically significant differences in the initial or final NRS scores among the three groups (both P-values > 0.05) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Changes of the numeric pain rating scale (NRS) score in patients with the global perceived effects (GPE) score ≥4 points before and after oral nystatin treatment in the three different groups of oral dysesthesia patients.

| NRS score |

Candida culture (+) |

Candida culture (−) |

Without Candida culture test |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 13) | (n = 16) | (n = 40) | ||

| Initial NRS score | 4.0 ± 2.5 | 5.9 ± 2.9 | 4.4 ± 2.1 | P = 0.058b |

| Final NRS score | 1.8 ± 1.3 | 2.1 ± 1.5 | 1.5 ± 1.5 | P = 0.300b |

| P = 0.003a | P < 0.001a | P < 0.001a |

Paired samples and two-tailed Student t-test between the initial and final NRS scores in each group.

Analysis of variance (ANOVA) among the three different groups.

We also found that of the 29 patients with Candida culture test and the GPE score ≥4 points, 10 Candida culture (+) and 11 Candida culture (−) patients achieved a GPE score ≥4 points after the first week of oral nystatin treatment. Moreover, all 29 patients with Candida culture test achieved a GPE score ≥4 points within 4 weeks of oral nystatin treatment (Table 5). Of the 13 Candida culture (+) patients with the GPE score ≥4 points, 2 achieved a GPE score = 5 points after 3 or 4 weeks of oral nystatin treatment. Of the 16 Candida culture (−) patients with the GPE score ≥4 points, 2 achieved a GPE score = 5 points after 1 week of oral nystatin treatment (Table 5).

Table 5.

The oral nystatin treatment period required for the patient to feel much improvement or entirely improvement (defined as the global perceived effects (GPE) score ≥4 points).

| Treatment periods (weeks) |

Candida culture (+) (n = 13) |

Candida culture (−) (n = 16) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GPE = 4 | GPE = 5 | GPE = 4 | GPE = 5 | |

| 1 | 10 | 0 | 9 | 2 |

| 2 | 11 | 0 | 12 | 2 |

| 3 | 11 | 1 | 14 | 2 |

| 4 | 12 | 1 | ||

Abbreviations: “+”, presence of Candida; “−”, absence of Candida.

Characteristics and types of oral mucosal dysesthesia

Oral dysesthesia patients complained of more than 10 different types of oral mucosal dysesthesia. One or more types of oral mucosal dysesthesia might present in the same patient. The different types of oral mucosal dysesthesia in 69 patients with the GPE score ≥4 points in the three different groups of patients are summarized in Table 6. Burning (87.0%), numbness (53.6%), and tingling pain (46.4%) were the three most frequently complained types of oral mucosal dysesthesia. Of the 69 patients with the GPE score ≥4 points, 63 (91.3%) had more than one type of oral mucosal dysesthesia simultaneously and 8 (11.6%) had up to 5 types of oral mucosal dysesthesia (Table 6).

Table 6.

The different types of oral mucosal dysesthesia in patients with the global perceived effects (GPE) score ≥4 points in the three different groups.

| Types of oral mucosal dysesthesia |

Candida culture (+) (n = 13) |

Candida culture (−) (n = 16) |

Without Candida culture test (n = 40) |

Total (n = 69) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Burning | 11 (84.6) | 15 (93.8) | 34 (85.0) | 60 (87.0) |

| Numbness | 8 (61.5) | 13 (81.3) | 16 (40.0) | 37 (53.6) |

| Tingling pain | 7 (53.8) | 8 (50.0) | 17 (42.5) | 32 (46.4) |

| Fullness pain | 3 (23.1) | 5 (31.3) | 10 (25.0) | 18 (26.1) |

| Sharp pain | 5 (38.5) | 1 (6.3) | 6 (15.0) | 12 (17.4) |

| Others | 2 (15.4) | 3 (18.8) | 2 (5.0) | 7 (10.1) |

| Itching | 0 (0.0) | 3 (18.8) | 4 (10.0) | 7 (10.1) |

| Dull pain | 0 (0.0) | 2 (12.5) | 3 (7.5) | 5 (7.2) |

| Cutting pain | 1 (7.7) | 1 (6.3) | 2 (5.0) | 4 (5.8) |

| Sore pain | 0 (0.0) | 1 (6.3) | 2 (5.0) | 3 (4.3) |

| Throbbing pain | 1 (7.7) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.4) |

| Compression pain | 1 (7.7) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.4) |

| Simultaneous presence of types of oral mucosal dysesthesia in patients | ||||

| 1 type | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 6 (15.0) | 6 (8.7) |

| 2 types | 7 (53.8) | 6 (37.5) | 12 (30.0) | 25 (36.2) |

| 3 types | 2 (15.4) | 5 (31.3) | 13 (32.5) | 20 (29.0) |

| 4 types | 1 (7.7) | 1 (6.3) | 8 (20.0) | 10 (14.5) |

| 5 types | 3 (23.1) | 4 (25.0) | 1 (2.5) | 8 (11.6) |

| ≥ 1 type | 13 (100.0) | 16 (100.0) | 34 (85.0) | 63 (91.3) |

“Others” represented the discomfort or pain that differed from the types of pain listed above, including but not limited to roughness and foreign body sensation.

Abbreviations: “+”, presence of Candida; “−”, absence of Candida.

The data are presented as the patient number (%).

Analysis of 29 oral dysesthesia patients with Candida culture test and the GPE score ≥4 points, there was no statistically significant difference in the proportion of all the various oral mucosal dysesthesia between the 13 patients in the Candida culture (+) group and the 16 patients in the Candida culture (−) group. However, patients in the Candida culture (+) group reported a higher frequency of intense oral pain, such as sharp pain, while the patients in the Candida culture (−) group reported a higher frequency of mild oral pain, such as dull or itching pain (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Heat map of pain type distribution in 29 patients with the Candida culture test and the global perceived effects (GPE) score ≥4 points.

Discussion

In this study, we evaluated the efficacy of oral nystatin treatment for oral dysesthesia patients and the necessity of Candida culture before oral nystatin treatment. The 147 oral dysesthesia patients were divided into 3 groups: 29 in the Candida culture (+) group, 34 in the Candida culture (−) group, and 84 in the without Candida culture test group. All of the 147 oral dysesthesia patients were given the oral nystatin treatment. Of 29 patients in the Candida culture (+) group, 44.8% of them reported a significant improvement in their symptoms after oral nystatin treatment. Additionally, 47.1% of the 34 patients in the Candida culture (−) group demonstrated a significant improvement in oral mucosal pain after oral nystatin treatment, and the improvement rate was even slightly higher than that of patients in the Candida culture (+) group, although the difference was not statistically significant. Besides, the patients in the Candida culture (−) group got the best NRS reduction and took less time to achieve a GPE score ≥4 points. This surprising result was beyond our original inference that the oral nystatin treatment might have little effect on patients in the Candida culture (−) group. Consequently, from this evidence, we suggest that the oral mucosal pain in some oral dysesthesia patients in the Candida culture (−) group may result from oral candidiasis but the Candida infection is so mild that results in the inability to cultivate sufficient quantities of Candida for obtaining a positive culture result in the microbiology laboratory. Moreover, 47.6% of 84 patients in the without culture test group achieved a great improvement in oral mucosal pain after oral nystatin treatment, despite that we could not ensure whether they were infected by Candida or not at the beginning of oral nystatin treatment. This particular finding indicates that oral nystatin treatment may be the first-line treatment of choice for oral dysesthesia patients before we start other kinds of specific therapy for oral dysesthesia patients. There is no need to do the Candida culture test before the oral nystatin treatment.

At the early stage in our oral mucosal disease clinic, we used simple cotton swabs to get the samples for Candida culture test. Although the Candida culture results were nearly all negative, approximately half of the oral dysesthesia patients reported excellent responses to oral nystatin treatment. This particular phenomenon made us ponder the possibility of sampling variation using simple cotton swabs for sampling and the necessity of sampling for Candida culture test before the start of oral nystatin treatment. Hence, some oral dysesthesia patients were directly treated with oral nystatin without doing the Candida culture tests. The strategy has changed to arrange a regular Candida culture test after the hospital replaced simple cotton swabs with the eSwabs, which were reported to have better sampling performance for Candida culture tests.45

Although these patients’ oral mucosae were morphologically normal clinically, positive cultures for Candida were observed in 46.03% (29/63) of the patients in our study, which was similar to 45.16% (14/31) of Candida culture positive rate for Brazilian BMS patients,46 although the sampling methods were different. Many previous studies assessed the relationship between Candida and oral mucosal dysesthesia/BMS,47 and all of them tried to clarify the association of the proposed causative/precipitating factors for oral mucosal dysesthesia/BMS. However, the conclusion shows no significant association of oral mucosal dysesthesia with the presence or the load of oral Candida.46, 47, 48, 49 Based on the above results and the concept that oral Candida is a common oral flora, most scientists still think that oral candidiasis is just a coincidence in BMS patients.46,49

Approximately 45%–48% of the oral dysesthesia patients in our study showed pain relief after oral nystatin treatment, irrespective of their culture results. Moreover, for the evaluation of NRS reduction after oral nystatin treatment, oral dysesthesia patients in the three different groups all presented a significant reduction in the oral pain level after oral nystatin treatment. Therefore, we aroused an idea that if antifungal treatment eliminates the burning or various kinds of abnormal oral sensations in patients with normal-looking oral mucosa, it may be explained that our oral dysesthesia patients still had some kind of mild but invisible oral candidiasis. This kind of oral candidiasis is not classified but was once mentioned by Cho et al. as morphologically normal symptomatic candidiasis.28 However, we may need further researches, especially the molecular biological and genetic studies, to prove that some oral dysesthesia patients do still have candidiasis even if the Candida culture is negative.

Indeed, there were still half of the oral dysesthesia patients in all three different groups who did not achieve a GPE score ≥4 points after oral nystatin treatment, and part of the patients were not satisfied with the improvement, even though they had achieved a GPE score ≥4 points. These oral dysesthesia patients might have primary BMS or they might be infected by other pathogens, resulting in poor efficacy of oral nystatin treatment. Nonetheless, in this group of patients insusceptible to oral nystatin, the physicians could search for other possible causes for BMS such as iron, vitamin B12, and folic acid deficiencies to test whether the iron, vitamin B12, and folic acid supplement therapy can achieve the symptom or pain relief in BMS patients.19,50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56, 57, 58, 59, 60, 61, 62, 63

Nystatin is a widely-used and long-established antifungal drug. Its various advantages, such as fewer adverse effects, inexpensive price, and effectiveness on oral candidiasis in a short period of time make it a first-line drug of choice for the treatment of oral candidiasis.29, 30, 31, 32 In this study, when assessing the patients who achieved a GPE score ≥4 points in both the Candida culture (+) and Candida culture (−) groups, 72.4% (21/29) of patients showed good responses to oral nystatin treatment within one week, and 100% of these 29 patients demonstrated either much improvement or entirely improvement within 4 weeks (Table 5). Additionally, it usually took at least a week or up to 4 weeks to obtain the result of the Candida culture test. Therefore, it would exist a gap for weeks before the patients received oral nystatin treatment. If the nystatin treatment should begin following the positive Candida culture results, it might render the treatment less effective due to the late intervention.

In the present study, burning pain, numbness, and tingling pain were the three predominant types of oral mucosal dysesthesia in our patients, which highly overlapped with the typical pain types in primary BMS, resulting in difficulty in the differential diagnosis between oral mucosal dysesthesia and primary BMS clinically. Besides, we noticed a slightly higher tendency to have the intense pain in patients in the Candida culture (+) group, whereas the mean NRS score was slightly lower in patients in the Candida culture (+) group (4.0 ± 2.5) than in patients in the Candida culture (−) group (5.9 ± 2.9) (Table 4). Moreover, the Vitkov's study pointed out the association of pre-DM or DM with oral candidiasis.64 In this study, we found a slightly higher frequency of pre-DM or DM in patients with the GPE score ≥4 points than in patients with the GPE score <4 points, although there was no statistically significant difference. In this regard, further follow-up studies with large sample size of oral dysesthesia patients are needed to confirm the relationship between the pain performance and the relatively higher blood glucose level in oral dysesthesia patients as well as between the oral candidiasis and the relatively higher blood glucose level in oral dysesthesia patients.

Finally, we propose that oral dysesthesia patients may have the morphologically normal symptomatic candidiasis, thus the oral nystatin treatment can be immediately given to the patients for up to 4 weeks, even before obtaining the fungal culture test result. Furthermore, the early use of nystatin treatment can help physicians to differentiate between primary BMS and oral candidiasis and reduce the chance of misdiagnosis, because the patients with primary BMS are often treated with the antidepressants or anticonvulsants that are expected to produce more adverse effects than the oral nystatin treatment.

Undeniably, our study exists some limitations. First, it was not a randomized controlled clinical trial. In addition, the precision of oral mucosal sampling might be affected by the inconsistent use of the swabs, which were changed from simple cotton swabs to the COPAN eSwabs after 2020. Last, we didn't have sufficient information on comorbidities and duration of symptoms to analyze their effect on the severity of disease and the assessment of clinical outcome of oral nystatin treatment. Thus, in the future, it is necessary to design a randomized controlled study to test the influence of comorbidities and duration of symptoms on the clinical outcomes of oral nystatin treatment for oral dysesthesia patients and the use of polymerase chain reaction (PCR) to precisely confirm whether the oral dysesthesia patients have the Candida infection or not.

In this study, 147 oral dysesthesia patients were treated with oral nystatin (4–6 cc, four times a day) for 1–4 weeks. We found that 44.8% of the 29 patients in the Candida culture (+) group, 47.1% of the 34 patients in the Candida culture (−) group, and 47.6% of the 84 patients in the without Candida culture test group showed a significant reduction in the NRS score and achieved a great improvement after oral nystatin treatment for 1–4 weeks. Moreover, 72.4% of our 29 oral dysesthesia patients with the Candida culture test achieved a great improvement within one week, and all the 29 oral dysesthesia patients achieved a great improvement within 4 weeks of oral nystatin treatment. This finding indicates that approximately 45%–48% of our oral dysesthesia patients can be effectively treated with oral nystatin and obtain a significant improvement of oral symptoms, regardless of whether the patients receive the Candida culture test before the start of oral nystatin treatment or not. Among the patients in three different groups, they had the nearly identical NRS score reduction and the similar proportions of patients with the GPE score ≥4 points after oral nystatin treatment. Therefore, we conclude that part of our oral dysesthesia patients are infected by Candida and it is beneficial to our oral dysesthesia patients to use oral nystatin treatment before the Candida culture test.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest relevant to this article.

Acknowledgements

This work was financially supported by Ministry of Science and Technology, Taiwan (grant number MOST108-2320-B-182A-011-MY3) and Chang Gung Memorial Hospital, Taiwan (grant number CMRPG1G0041). We would like to thank Shu-Ching Chen for data collection and Department of Laboratory Medicine, Chang Gung Memorial Hospital at Linkou for technical assistance with the Candida culture and blood tests.

Contributor Information

Chun-Pin Chiang, Email: cpchiang@ntu.edu.tw.

Meng-Ling Chiang, Email: mlingchiang@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Tan H., Renton T. Burning mouth syndrome: an update. Cephalalgia Rep. 2020;3:1–18. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kamala K.A., Sankethguddad S., Sujith S.G., Tantradi P. Burning mouth syndrome. Indian J Palliat Care. 2016;22:74–79. doi: 10.4103/0973-1075.173942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Scala A., Checchi L., Montevecchi M., Marini I., Giamberardino M.A. Update on burning mouth syndrome: overview and patient management. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med. 2003;14:275–291. doi: 10.1177/154411130301400405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Freilich J.E., Kuten-Shorrer M., Treister N.S., Woo S.B., Villa A. Burning mouth syndrome: a diagnostic challenge. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2020;129:120–124. doi: 10.1016/j.oooo.2019.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dahiya P., Kamal R., Kumar M., Niti Gupta R., Chaudhary K. Burning mouth syndrome and menopause. Int J Prev Med. 2013;4:15–20. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kohorst J.J., Bruce A.J., Torgerson R.R., Schenck L.A., Davis M.D.P. The prevalence of burning mouth syndrome: a population-based study. Br J Dermatol. 2015;172:1654–1656. doi: 10.1111/bjd.13613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bergdahl M., Bergdahl J. Burning mouth syndrome: prevalence and associated factors. J Oral Pathol Med. 1999;28:350–354. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.1999.tb02052.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jääskeläinen S.K. Is burning mouth syndrome a neuropathic pain condition? Pain. 2018;159:610–613. doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000001090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Puhakka A., Forssell H., Soinila S., et al. Peripheral nervous system involvement in primary burning mouth syndrome--results of a pilot study. Oral Dis. 2016;22:338–344. doi: 10.1111/odi.12454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reyes-Sevilla M. Is burning mouth syndrome based on a physiological mechanism which resembles that of neuropathic pain? Odovtos Int J Dent Sc. 2020;22:14–17. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Minguez-Sanz M.P., Salort-Llorca C., Silvestre-Donat F.J. Etiology of burning mouth syndrome: a review and update. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2011;16:e144–e148. doi: 10.4317/medoral.16.e144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grushka M., Epstein J.B., Gorsky M. Burning mouth syndrome. Am Fam Physician. 2002;65:615–620. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Taiminen T., Kuusalo L., Lehtinen L., et al. Psychiatric (axis I) and personality (axis II) disorders in patients with burning mouth syndrome or atypical facial pain. Scand J Pain. 2011;2:155–160. doi: 10.1016/j.sjpain.2011.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schiavone V., Adamo D., Ventrella G., et al. Anxiety, depression, and pain in burning mouth syndrome: first chicken or egg? Headache. 2012;52:1019–1025. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2012.02171.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hens M.J., Alonso-Ferreira V., Villaverde-Hueso A., Abaitua I., Posada de la Paz M. Cost-effectiveness analysis of burning mouth syndrome therapy. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2012;40:185–192. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.2011.00645.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kuten-Shorrer M., Treister N.S., Stock S., et al. Safety and tolerability of topical clonazepam solution for management of oral dysesthesia. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2017;124:146–151. doi: 10.1016/j.oooo.2017.05.470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yamazaki Y., Hata H., Kitamori S., Onodera M., Kitagawa Y. An open-label, noncomparative, dose escalation pilot study of the effect of paroxetine in treatment of burning mouth syndrome. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2009;107:e6–e11. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2008.08.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Forabosco A., Criscuolo M., Coukos G., et al. Efficacy of hormone replacement therapy in postmenopausal women with oral discomfort. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1992;73:570–574. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(92)90100-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sun A., Lin H.P., Wang Y.P., Chen H.M., Cheng S.J., Chiang C.P. Significant reduction of serum homocysteine level and oral symptoms after different vitamin-supplement treatments in patients with burning mouth syndrome. J Oral Pathol Med. 2013;42:474–479. doi: 10.1111/jop.12043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gorsky M., Silverman S., Chinn H. Clinical characteristics and management outcome in the burning mouth syndrome: an open study of 130 patients. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1991;72:192–195. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(91)90162-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Akpan A., Morgan R. Oral candidiasis. Postgrad Med. 2002;78:455. doi: 10.1136/pmj.78.922.455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Millsop J.W., Fazel N. Oral candidiasis. Clin Dermatol. 2016;34:487–494. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2016.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Aguirre Urizar J.M. [Oral candidiasis] Rev Iberoam Micol. 2002;19:17–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Williams D.W., Kuriyama T., Silva S., Malic S., Lewis M.A. Candida biofilms and oral candidosis: treatment and prevention. Periodontology. 2000 2011;55:250–265. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.2009.00338.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Osaki T., Yoneda K., Yamamoto T., Ueta E., Kimura T. Candidiasis may induce glossodynia without objective manifestation. Am J Med Sci. 2000;319:100–105. doi: 10.1097/00000441-200002000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Terai H., Shimahara M. Glossodynia from Candida-associated lesions, burning mouth syndrome, or mixed causes. Pain Med. 2010;11:856–860. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2010.00861.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Terai H., Shimahara M. Tongue pain: burning mouth syndrome vs Candida-associated lesion. Oral Dis. 2007;13:440–442. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-0825.2006.01325.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cho E., Park Y., Kim K.Y., et al. Clinical characteristics and relevance of oral Candida biofilm in tongue smears. J Fungi (Basel) 2021;7:77. doi: 10.3390/jof7020077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Epstein J.B., Polsky B. Oropharyngeal candidiasis: a review of its clinical spectrum and current therapies. Clin Therapeut. 1998;20:40–57. doi: 10.1016/s0149-2918(98)80033-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Samaranayake L.P., Keung Leung W., Jin L. Oral mucosal fungal infections. Periodontology. 2009;49:39–59. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.2008.00291.x. 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lyu X., Zhao C., Yan Z.M., Hua H. Efficacy of nystatin for the treatment of oral candidiasis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Drug Des Dev Ther. 2016;10:1161–1171. doi: 10.2147/DDDT.S100795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Quindós G., Gil-Alonso S., Marcos-Arias C., et al. Therapeutic tools for oral candidiasis: current and new antifungal drugs. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2019;24:e172–e180. doi: 10.4317/medoral.22978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kaur I.P., Kakkar S. Topical delivery of antifungal agents. Expet Opin Drug Delivery. 2010;7:1303–1327. doi: 10.1517/17425247.2010.525230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Epstein J.B. Antifungal therapy in oropharyngeal mycotic infections. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1990;69:32–41. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(90)90265-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Greenspan D. Treatment of oropharyngeal candidiasis in HIV-positive patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;31:S51–S55. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(08)81268-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wong S.S.W., Samaranayake L.P., Seneviratne C.J. In pursuit of the ideal antifungal agent for Candida infections: high-throughput screening of small molecules. Drug Discov. 2014;19:1721–1730. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2014.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Niimi M., Firth N.A., Cannon R.D. Antifungal drug resistance of oral fungi. Odontology. 2010;98:15–25. doi: 10.1007/s10266-009-0118-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rautemaa R., Ramage G. Oral candidosis--clinical challenges of a biofilm disease. Crit Rev Microbiol. 2011;37:328–336. doi: 10.3109/1040841X.2011.585606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Iohom G. In: Postoperative pain management. Shorten G., Carr D.B., Harmon D., Puig M.M., Browne J., editors. W.B. Saunders; Philadelphia: 2006. Chapter 11 – clinical assessment of postoperative pain; pp. 102–108. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Edwards R.R. In: Essentials of pain medicine and regional anesthesia. 2nd ed. Benzon H.T., Raja S.N., Molloy R.E., Liu S.S., Fishman S.M., editors. Churchill Livingstone; Philadelphia: 2005. Chapter 5 – pain assessment; pp. 29–34. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Forssell H., Teerijoki-Oksa T., Kotiranta U., et al. Pain and pain behavior in burning mouth syndrome: a pain diary study. J Orofac Pain. 2012;26:117–125. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cavalcanti D.R., da Silveira F.R. Alpha lipoic acid in burning mouth syndrome--a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial. J Oral Pathol Med. 2009;38:254–261. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.2008.00735.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kamper S.J., Ostelo R.W.J.G., Knol D.L., Maher C.G., de Vet H.C.W., Hancock M.J. Global Perceived Effect scales provided reliable assessments of health transition in people with musculoskeletal disorders, but ratings are strongly influenced by current status. J Clin Epidemiol. 2010;63:760–766.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Meisingset I., Stensdotter A.K., Woodhouse A., Vasseljen O. Predictors for global perceived effect after physiotherapy in patients with neck pain: an observational study. Physiotherapy. 2018;104:400–407. doi: 10.1016/j.physio.2017.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wise N.M., Wagner S.J., Worst T.J., Sprague J.E., Oechsle C.M. Comparison of swab types for collection and analysis of microorganisms. Microbiologyopen. 2021;10:e1244. doi: 10.1002/mbo3.1244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cavalcanti D.R., Birman E.G., Migliari D.A., da Silveira F.R. Burning mouth syndrome: clinical profile of Brazilian patients and oral carriage of Candida species. Braz Dent J. 2007;18:341–345. doi: 10.1590/s0103-64402007000400013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Farah C.S., Amos K., Leeson R., Porter S. Candida species in patients with oral dysesthesia: a comparison of carriage among oral disease states. J Oral Pathol Med. 2018;47:281–285. doi: 10.1111/jop.12675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shimizu C., Kuriyama T., Williams D.W., et al. Association of oral yeast carriage with specific host factors and altered mouth sensation. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2008;105:445–451. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2007.11.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sardella A., Lodi G., Demarosi F., Uglietti D., Carrassi A. Causative or precipitating aspects of burning mouth syndrome: a case-control study. J Oral Pathol Med. 2006;35:466–471. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.2006.00438.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chiang C.P., Wu Y.H., Wu Y.C., Chang J.Y.F., Wang Y.P., Sun A. Anemia, hematinic deficiencies, hyperhomocysteinemia, and serum gastric parietal cell antibody positivity in 884 patients with burning mouth syndrome. J Formos Med Assoc. 2020;119:813–820. doi: 10.1016/j.jfma.2019.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chiang C.P., Wu Y.C., Wu Y.H., Chang J.Y.F., Wang Y.P., Sun A. Gastric parietal cell and thyroid autoantibody in patients with burning mouth syndrome. J Formos Med Assoc. 2020;119:1758–1763. doi: 10.1016/j.jfma.2020.08.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chiang M.L., Wu Y.H., Chang J.Y.F., Wang Y.P., Wu Y.C., Sun A. Anemia, hematinic deficiencies, and hyperhomocysteinemia in gastric parietal cell antibody-positive and -negative burning mouth syndrome patients. J Formos Med Assoc. 2021;120:819–826. doi: 10.1016/j.jfma.2020.08.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chiang M.L., Jin Y.T., Chiang C.P., Wu Y.H., Chang J.Y.F., Sun A. Anemia, hematinic deficiencies, hyperhomocysteinemia, and gastric parietal cell antibody positivity in burning mouth syndrome patients with vitamin B12 deficiency. J Dent Sci. 2020;15:34–41. doi: 10.1016/j.jds.2019.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chiang M.L., Chiang C.P., Sun A. Anemia, hematinic deficiencies, and gastric parietal cell antibody positivity in burning mouth syndrome patients with or without hyperhomocysteinemia. J Dent Sci. 2020;15:214–221. doi: 10.1016/j.jds.2020.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Jin Y.T., Chiang M.L., Wu Y.H., Chang J.Y.F., Wang Y.P., Sun A. Anemia, hematinic deficiencies, hyperhomocysteinemia, and gastric parietal cell antibody positivity in burning mouth syndrome patients with iron deficiency. J Dent Sci. 2020;15:42–49. doi: 10.1016/j.jds.2019.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Jin Y.T., Wu Y.C., Wu Y.H., Chang J.Y.F., Chiang C.P., Sun A. Anemia, hematinic deficiencies, hyperhomocysteinemia, and gastric parietal cell antibody positivity in burning mouth syndrome patients with or without microcytosis. J Dent Sci. 2021;16:608–613. doi: 10.1016/j.jds.2020.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jin Y.T., Wu Y.H., Wu Y.C., Chang J.Y.F., Chiang C.P., Sun A. Anemia, hematinic deficiencies, and hyperhomocysteinemia in serum gastric parietal cell antibody-positive burning mouth syndrome patients without serum thyroid autoantibodies. J Dent Sci. 2021;16:1110–1116. doi: 10.1016/j.jds.2021.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Jin Y.T., Wu Y.H., Wu Y.C., Chang J.Y.F., Chiang C.P., Sun A. Anemia, hematinic deficiencies, hyperhomocysteinemia, and gastric parietal cell antibody positivity in burning mouth syndrome patients with macrocytosis. J Dent Sci. 2021;16:1133–1139. doi: 10.1016/j.jds.2021.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wu Y.H., Jin Y.T., Wu Y.C., Chang J.Y.F., Chiang C.P., Sun A. Anemia, hematinic deficiencies, hyperhomocysteinemia, and gastric parietal cell antibody positivity in burning mouth syndrome patients with normocytosis. J Dent Sci. 2022;17:35–41. doi: 10.1016/j.jds.2021.09.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Jin Y.T., Wu Y.H., Wu Y.C., Chang J.Y.F., Chiang C.P., Sun A. Higher gastric parietal cell antibody titer significantly increases the frequencies of macrocytosis, serum vitamin B12 deficiency, and hyperhomocysteinemia in patients with burning mouth syndrome. J Dent Sci. 2022;17:57–62. doi: 10.1016/j.jds.2021.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Jin Y.T., Wu Y.C., Wu Y.H., Chang J.Y.F., Chiang C.P., Sun A. Anemia, hematinic deficiencies, and hyperhomocysteinemia in burning mouth syndrome patients with thyroglobulin antibody/thyroid microsomal antibody positivity but without gastric parietal cell antibody positivity. J Dent Sci. 2022;17:106–112. doi: 10.1016/j.jds.2021.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wu Y.H., Jin Y.T., Wu Y.C., Chang J.Y.F., Chiang C.P., Sun A. Anemia, hematinic deficiencies, and hyperhomocysteinemia in male and female burning mouth syndrome patients. J Dent Sci. 2022;17:935–941. doi: 10.1016/j.jds.2021.11.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wu Y.H., Wu Y.C., Chang J.Y.F., Lang M.J., Chiang C.P., Sun A. Anemia, hematinic deficiencies, and hyperhomocysteinemia in younger and older burning mouth syndrome patients. J Dent Sci. 2022;17:1144–1150. doi: 10.1016/j.jds.2022.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Vitkov L., Weitgasser R., Hannig M., Fuchs K., Krautgartner W.D. Candida-induced stomatopyrosis and its relation to diabetes mellitus. J Oral Pathol Med. 2003;32:46–50. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0714.2003.00020.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]